Abstract

Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography (iOCT) has advanced in recent years to provide real-time high resolution volumetric imaging for ophthalmic surgery. It enables real-time 3D feedback during precise surgical maneuvers. Intraoperative 4D OCT generally exhibits lower signal-to-noise ratio compared to diagnostic OCT and visualization is complicated by instrument shadows occluding retinal tissue. Additional constraints of processing data rates upwards of 6GB/s create unique challenges for advanced visualization of 4D OCT. Prior approaches for real-time 4D iOCT rendering have been limited to applying simple denoising filters and colorization to improve visualization.

We present a novel real-time rendering pipeline that provides enhanced intraoperative visualization and is specifically designed for the high data rates of 4D iOCT. We decompose the volume into a static part consisting of the retinal tissue and a dynamic part including the instrument. Aligning the static parts over time allows temporal compounding of these structures for improved image quality. We employ a translational motion model and use axial projection images to reduce the dimensionality of the alignment. A model-based instrument segmentation on the projections discriminates static from dynamic parts and is used to exclude instruments from the compounding. Our real-time rendering method combines the compounded static information with the latest iOCT data to provide a visualization which compensates instrument shadows and improves instrument visibility.

We evaluate the individual parts of our pipeline on pre-recorded OCT volumes and demonstrate the effectiveness of our method on a recorded volume sequence with a moving retinal forceps.

Keywords: Advanced Intraoperative Visualization, Optical Coherence Tomography, Real-Time Volumetric Processing

1. Introduction

Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography (iOCT) in ophthalmology has seen dramatic technical advances in imaging speed and quality in recent years. Technological advances such as the application of swept-source lasers [8], spectral splitting [7] and linear velocity spiral scanning [3] have made continuous 4D intraoperative OCT imaging feasible at high resolution and volume rates. State of the art systems are able to sample with volume rates of up to 24.2Hz at a resolution of 330×330×595 voxels [9]. Ehlers et al. [4] have shown the effectiveness of 2D iOCT in clinical practice in a large scale study, however clinical studies on 4D OCT do not yet exist. Still, 4D OCT is expected to improve spatial visualization during complex and precise maneuvers. Potential applications include robotics [18] or even retinal surgery under exclusive OCT guidance [9] which can greatly reduce adverse effects associated with the endoilluminators required for traditional fundus view surgery. With data rates surpassing 6GB/s, 4D iOCT is a uniquely challenging modality for advanced processing in an intraoperative setting. OCT-only surgery is currently challenged also by higher noise level compared to diagnostic OCT, instrument shadows hiding relevant anatomical structures and a limited field of view.

In this work, we propose a real-time processing and rendering pipeline to improve instrument visibility by combining volumes temporally. A semantic segmentation step allows to discern static retinal tissue, which is then used to register subsequent volumes and selectively mitigate instrument shadows. We propose an adaptive visualization that makes the involved processing steps apparent to the viewer.

To improve quality in diagnostic OCT, repeated scanning of B-scans is employed to reduce noise by averaging[15,1]. Because this approach would reduce volume rates to impractical speeds, a similar solution is to average subsequent volumes, however this requires some form of motion compensation. Previous works on OCT motion compensation are focused on motion during acquisition of a single volume [10] or on registering diagnostic OCT volumes acquired at different visits for progression analysis. 3D SIFT features [12] have been used for full 3D registration but many approaches use 2D projections generated from volumes to perform separate alignment across dimensions using ICP [13], SIFT [6] or SURF [14]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no published research on solving the problem with the additional constraints of real-time processing and a potentially moving surgical instrument.

Metallic instruments pose an additional challenge to iOCT visualization, causing total loss of signal below the instrument due to the metal blocking the light. This shadows relevant retinal tissue below the instrument, causing ”holes” in the 3D rendering. Special OCT-compatible instruments have been proposed [5], but are not yet translated to clinical practice. Effective visualization of iOCT volumes is not trivial due to the aforementioned problems, which is why straightforward methods like direct volume rendering (DVR) with intensity-based transfer functions perform badly (c.f. Fig. 1, left). Viehland et al. [16] introduced a DVR method for OCT that was extended by Draelos et al. [2] to add colorization along the axial direction. Both however rely on spatial filtering with Gaussian and median filters to reduce noise prior to rendering. Recently, Weiss et al. [17] introduced a layer-aware volume rendering in which a layer segmentation was used to anchor a color map to improve perception (c.f. Fig. 1, middle). In this work, our aim is to show the feasibility of advanced real-time processing and visualization for 4D iOCT. Our novel real-time processing and rendering method combines temporal information and mitigates instrument opacity (c.f. Fig. 1, right).

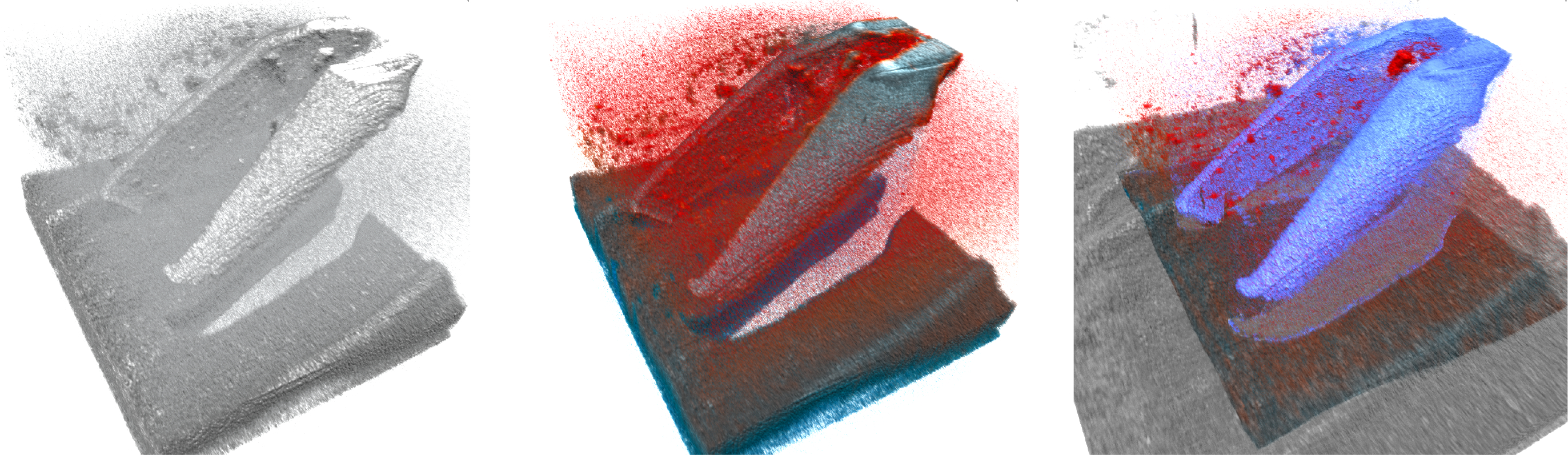

Fig. 1.

Challenges and our solution to 4D iOCT rendering: Straightforward DVR (left) is not sufficient for good visualization and advanced color schemes[17] (middle) do not cope well with noise and artifacts. Our novel method (right) reduces noise and artifacts and extends the field of view. All images were rendered with the same opacity transfer function. See supplementary material for a high-resolution version.

Our contributions are the following: We introduce a fast registration and compositing method that temporally combines the static parts within the OCT view. This is supported by a learning-based instrument segmentation in 2D projection images. We then propose a processing-aware rendering method that optimizes tissue visibility by inpainting shadowed areas, ensuring interpretability of the view through sensible color mapping.

2. Methods

Our visualization was built around the two goals of reducing imaging noise over time and using data from previous frames to fill in the gaps produced by instrument shadowing. The approach is based on the notion that with 4D iOCT, retinal tissue is imaged many times while remaining relatively unchanged. Therefore, we discriminate the retinal tissue to align it over time and use the aggregated information to improve our visualization. Due to the high data rates and time constraints we rely on processing 2D projection images instead of 3D volumes.

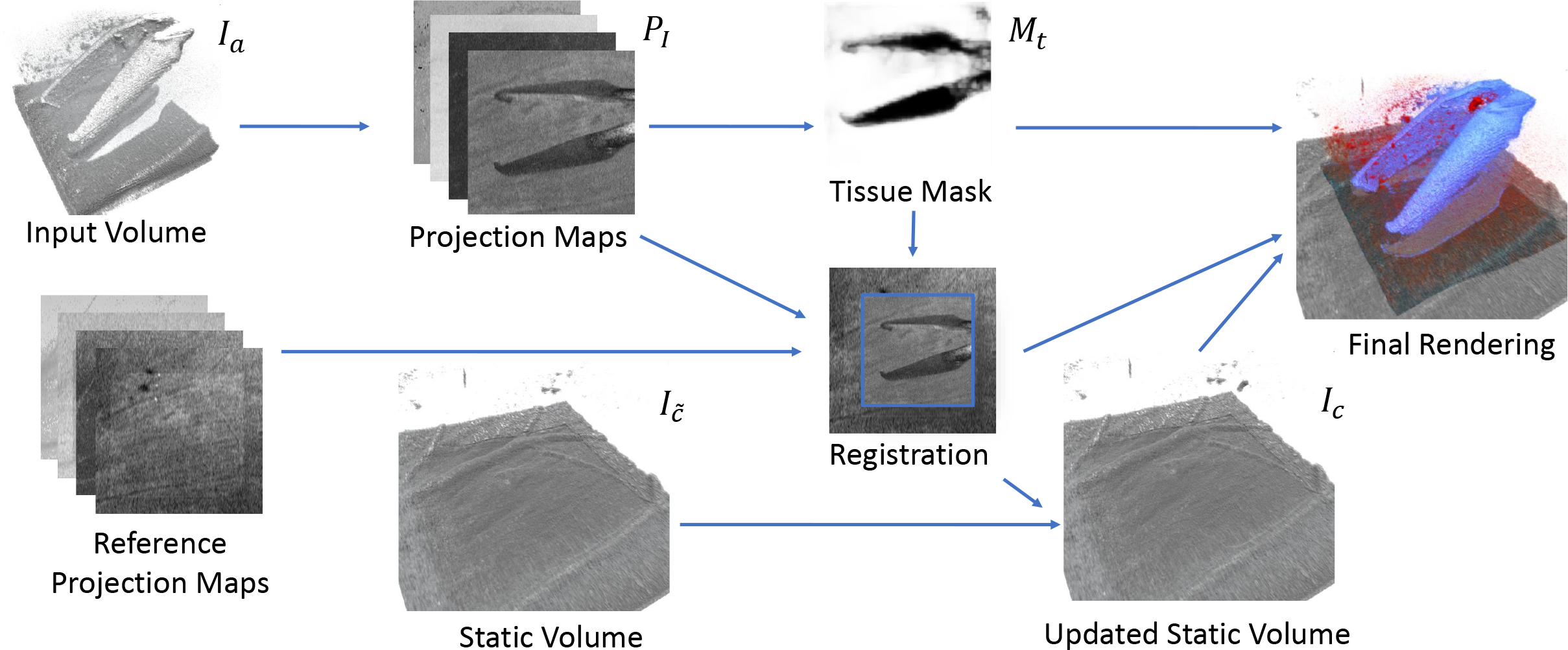

Our novel method consists of several steps (see Fig. 2): To initialize our algorithm, a larger reference volume is acquired to prime our compounding volume Ic and establish a reference. For each newly acquired volume Ia and once for the reference volume, we generate a set of 2D projection images and use a learning-based approach to find a tissue mask Mt by segmenting instruments in 2D. The masked projection images are then used to register the Ia to Ic. The registration together with Mt allows us to maintain an updated representation of the static retinal tissue while excluding the instrument and shadows. Finally, our enhanced rendering selectively combines the two volumes to provide an responsive visualization. We leverage the instrument mask and projection images to combine Ic and Ia on the fly during rendering and adapt the rendering parameters, encoding the reliability of the information through color.

Fig. 2.

Our processing pipeline for a single new acquired volume. Reference projection maps are generated from an overview scan at acquisition start.

2.1. Axial Projection Images

Axial projection images are a class of 2D images that we generate from projecting every A-scan in the volume to a single corresponding value. Averaging projections have been used extensively in the past [13,14,6] as so-called Enface images. We generalize them to new functions which create 2D feature maps P(x, y) with different characteristics that we use for alignment and instrument segmentation:

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

| (1c) |

| (1d) |

where N is the number of samples in one A-scan.

Note that while Average and Maximum encode intensity features, Argmax and Centroid provide positional information while they can still be computed simultaneously in a single iteration over the A-Scan voxels.

2.2. Learning-based instrument segmentation

A tissue mask Mt is obtained from the 2D projections by training a simple and lightweight segmentation model. We use the pytorch-based fast.ai library to train a UNet variant5 that uses a ResNet18-based encoder that was pretrained on ImageNet connected to a decoder with skip connections to perform subsequent upsampling. All four available projection images are provided as input features to the network to maximize accuracy.

2.3. Registration

To combine the sequence of volumes, it is required to know for every voxel the corresponding location in the compounded volume. During a surgery, the imaged region can change over time due to systematic changes of the galvo offsets, but also due to relative movement of the patient’s eye.

Motion Model.

With the eye anaesthetized and fixed in the eye socket, rotations generally only occur during brief, intentional adjustments of the view by the surgeon. During precise manipulation in which our OCT image guidance is used, the surgeon actively stabilizes the eye and thus we adjust one d.o.f. less than [14]. Due to our exponential averaging, only the most recent few volumes influence the displayed result. Analyzing DS3 (see Sec.3) using offline volumetric registration confirms that axial rotation is negligible in our data set as rotation between consecutive volumes is below 0.5°. We approximate the motion as a pure translational change in the OCT coordinate system. Two corresponding positions in reference and acquired volume pr, pa are related by pr = pa + ta. We further decompose the translation ta can be decomposed into the transverse translation (tx, ty) (mainly caused by rotational movement of the eye around its center) and the axial translation tz (typically caused by inadvertent pressure on the trocars pushing the eye into or out of the eye socket).

Transverse Alignment.

Because the transverse alignment (tx, ty) is aligned with the layout of the generated projection images Pr, Pa, we can find the best alignment using template matching with normalized cross correlation (NCC) as a metric. To find the transverse alignment, we compute the location of maximum NCC between Pr and Pa using Mt to mask instrument pixels in the template.

Axial Alignment.

To find the axial alignment tz, we use the Pargmax images in the region where the two images overlap based on (tx, ty). We compute the average distance across the overlap region O while taking into account the tissue mask Mt of the current image:

| (2) |

2.4. Compounding

With a known transformation we can integrate the new volume Ia in our compounded representation Ic of the static scene:

| (3) |

for every voxel position p in Ic where ω = ω0Mt(p) and ω0 is a integration weighting parameter used to control the amount of exponential averaging over time. The update conditionally integrates new data for A-Scans where Mt is not set while retaining data from the previous compounded volume Ic˜ otherwise. Using the Mt in the integration weighting masks out A-scans containing the instrument while averaging the retinal tissue.

2.5. Rendering

To provide a well interpretable rendering that makes the user apparent of the reliability of the shown data, we use an adaptive colorization that extends the color map by Weiss [17]. Our goal is to emphasize which parts of the volume are from the last acquired volume and visually set apart data that has been inpainted from previous data. Thus, we differentiate three semantic regions within our volumes: (a) data that has been recently updated or is sampled directly from Ia, (b) data that has been inpainted from the Ic with no correspondence in Ia and (c) areas around the instrument. When determining the sample intensity Is for a raymarch step position ps, we combine Ic and Ia using an instrument predicate κi and a recency predicate κr defined as:

| (4a) |

| (4b) |

In A-scans that contain an instrument, we combine the intensities of both volumes with a max operation. The max operation ensures visibility of both instrument and inpainted tissue in areas of signal loss:

| (5) |

The recency predicate therefore marks sampled locations in which Is was influenced by the most recently acquired volume, either because it was incorporated into the compounding (Eq. 3) or used directly (Eq. 5). In tissue regions, we apply the same layer colorization CLAB(I, δ∗(p)) as [17]. We compensate for the lack of a layer segmentation by instead using Pargmax to align the axial color mapping to the retinal structure. Furthermore, the colorization is only applied for pixels that have not been inpainted from the compounded volume, using a grayscale colormap for this data instead. For instrument areas, we use a fixed color Ci to further enhance instrument visibility and contrast to the surrounding tissue.

| (6) |

3. Results

As state of the art 4D iOCT systems are not readily available, the three data sets used in this work were instead recorded with a RESCAN 700 (Carl Zeiss Meditec) iOCT system (27kHz A-Scan rate) which acquires volumes of 512×128×1024 resolution at non-interactive rates. DS1 consists of projection images from 605 retinal OCT scans containing a range of different instruments and situations in human or porcine eyes. We generated projection images as described in Sec. 2.1, resample them to 128×128px and manually labeled the instruments. DS2 consists of 3×3×2.9mm3 OCT volumes from 6 enucleated porcine eyes with removed anterior segment. On a fixated eye, a 6×6×2.9mm3 reference volume and grids of 5×5 volumes were acquired with 0.25mm offset in x/y dimensions by changing the OCT acquisition offset. In three eyes, a 23G vitreoretinal forceps was used, in the remaining three a 27G injection needle. DS3 is a sequence of 67 volumes from an enucleated porcine eye with intact anterior segment. The first volume is acquired at 6×6×2.9mm3 while the following are recorded with 3×3×2.9mm3 field of view. A surgical instrument (23G retinal forceps) was moved between acquisitions to create a simulated 4D OCT sequence that shows instrument and retina motion as described in Sec. 2.3.

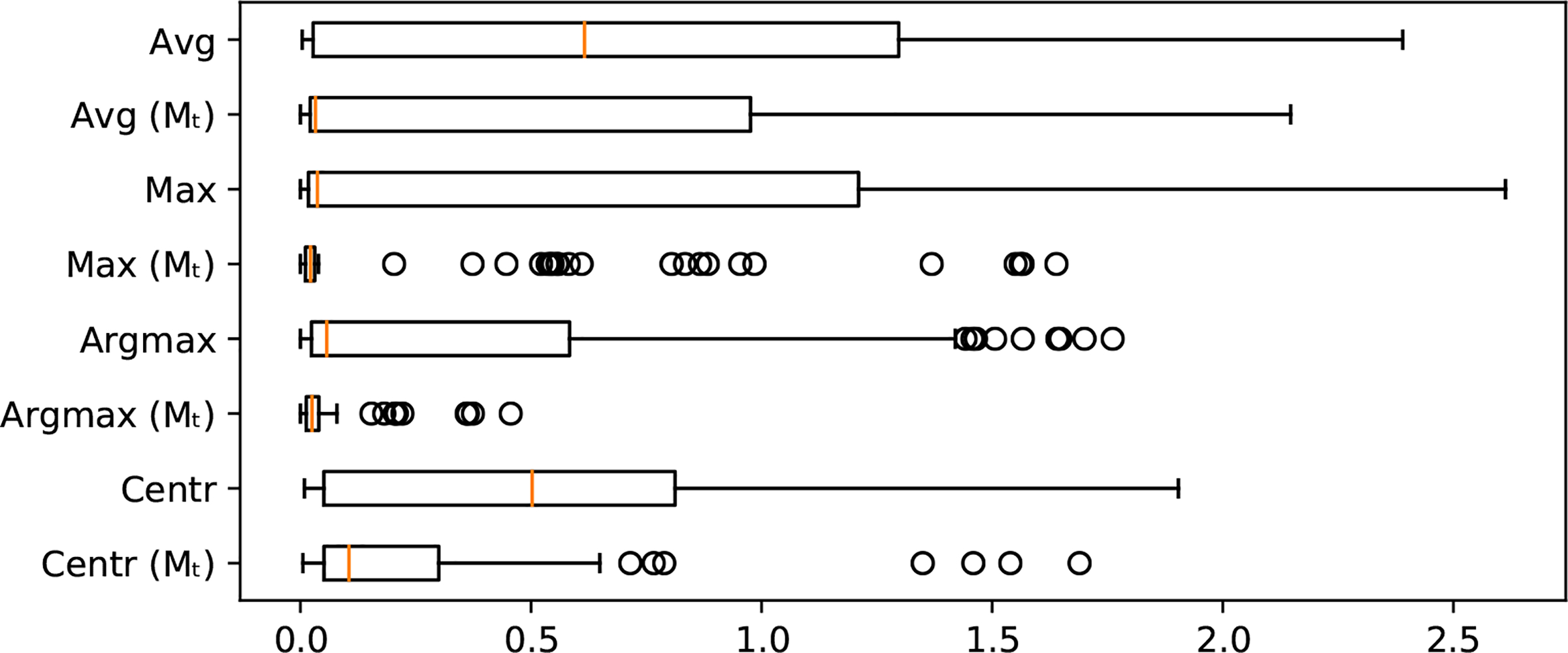

Registration.

To evaluate our registration approach, we use the known relative offsets between volumes in DS2. We use the reference volume of each eye and register each of the 25 grid volumes to it using our approach. Figure 3 shows the registration error of the offsets dx, dy after registration for different projection images. The results show that using Mt dramatically improves the registration. Overall the argmax image performed best with an average offset error of 0.0426mm, RMSE of 0.0583mm and median error of 0.025mm.

Fig. 3.

Registration error (in mm) without using a tool mask compared to the registration error using Mt.

Instrument Segmentation.

We train our segmentation model on DS1 with a batch size of 64 and random data split of 80% training and 20% validation set. To overcome the problems related to limited size of our data set and to enhance the generalization of our segmentation model we augment with vertical and horizontal flipping, random rotation up to 10 degrees and random cropping to zoom up to a maximum scaling factor of 1.5. We use cross-entropy as our loss function and train with a learning rate of 0.01 and the AdamW [11] optimizer (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.99). Our model converged after 95 epochs and has a validation accuracy of 99.34% and 85.33% for retina and instrument classes, respectively.

Real-time processing.

Our real-time visualization system was implemented in C++. We use the OpenCL-accelerated template matching implementation of OpenCV and TensorRT6 to optimize and execute our trained model on the GPU. Projection image generation, volume compounding and rendering leverage the GPU using OpenGL. We evaluated computational performance by looping DS3 (see Supp. Video) with data preloaded to the GPU to simulate GPU reconstruction as in [9]. To compare our implementation to the data rates of a state of the art SS-OCT device, we resample our input data to a matching resolution of 330×330×595. Table 2 shows the average results on the original and resampled data sets on our evaluation system (Intel Core i7–8700K @3.7GHz, NVidia Titan Xp). The total processing time dictates both maximum frame rate rate of our setup and minimum latency from acquisition to display. Our achieved 21.32 frames per second is close to 24.2Hz volume rate rate reported by [9].

Table 2.

Average processing time in ms for volumes at source and resampled resolution.

| Project | Segment | Register | Compound | Render | Total | FPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 512×128×1024 | 1.92 | 7.41 | 11.91 | 7.61 | 19.00 | 47.85 | 20.90 |

| 330×330×595 | 1.81 | 6.68 | 20.80 | 8.49 | 9.13 | 46.91 | 21.32 |

4. Discussion and Conclusions

We presented the first end-to-end real-time pipeline to process and visualize 4D OCT data while mitigating instrument shadowing. Our adaptive visualization makes this processing and enhancement visible to the viewer and aids interpretation of the shown data. We demonstrated the feasibility of such a pipeline, achieving real-time processing speeds close to the state of the art imaging systems. Our evaluation reveals potential for future improvements for the registration approach. The implementation is based on off-the-shelf solutions for template matching and 2D image segmentation. Our matching errors are in the order of several px which leads to potentially oversmoothed results. Because the focus of this work was to introduce the general concept and benefits of temporal alignment in 4D OCT, we consider the evaluation and development of more robust registration solutions as future work. A further interesting challenge is how to mitigate deformations that are caused for example by tool-tissue interactions. With the current approach, these deformations are smoothed over time as the compounded volume Ic gets updated. A higher value for ω0 can improve responsiveness in these cases at the cost of lower denoising, thus more fine-grained adaptations of ω(p) could be developed in future extensions.

4D iOCT is not yet widely available but has already attracted much interest within its community. In this work, we developed a novel visualization and tested it on simulated 4D iOCT on porcine eyes. The described approach is currently being integrated into a state-of-the-art 4D iOCT imaging system. Once the integrated system has received ethical approval, it will be able to supply data with moving instruments within human eyes and thus enable further investigations into the clinical benefits of our advanced processing and visualization.

Data Set and Code Availability

The data sets and code used in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Comparison of projection images in terms of their registration performance using Mt (errors in mm).

| Projection | Avg Error | RMSE | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 0.5379 | 0.6743 | 0.6516 |

| Maximum | 0.1394 | 0.2034 | 0.3329 |

| Argmax | 0.0426 | 0.0583 | 0.0675 |

| Centroid | 0.2128 | 0.2985 | 0.2817 |

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health under grant number 1R01EB025883–01A1 as well as the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany (BMBF) in the framework of Software Campus 2.0 (FKZ 01IS17049). The authors acknowledge NVidia Corporation for donating the GPU used in the experiments.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Baumann B, Merkle CW, Leitgeb RA, Augustin M, Wartak A, Pircher M, Hitzenberger CK: Signal averaging improves signal-to-noise in OCT images: But which approach works best, and when? Biomedical Optics Express 10(11), 5755 (November 2019). 10.1364/boe.10.005755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleicher ID, Jackson-Atogi M, Viehland C, Gabr H, Izatt JA, Toth CA: Depth-Based, Motion-Stabilized Colorization of Microscope-Integrated Optical Coherence Tomography Volumes for Microscope-Independent Microsurgery. Translational Vision Science & Technology 7(6), 1 (November 2018). 10.1167/tvst.7.6.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrasco-Zevallos OM, Viehland C, Keller B, McNabb RP, Kuo AN, Izatt JA: Constant linear velocity spiral scanning for near video rate 4D OCT ophthalmic and surgical imaging with isotropic transverse sampling. Biomedical Optics Express 9(10), 5052 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.005052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehlers JP, Modi YS, Pecen PE, Goshe J, Dupps WJ, Rachitskaya A, Sharma S, Yuan A, Singh R, Kaiser PK, Reese JL, Calabrise C, Watts A, Srivastava SK: The DISCOVER Study 3-Year Results. Ophthalmology 125(7), 1014–1027 (July 2018). 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehlers JP, Uchida A, Srivastava SK: Intraoperative optical coherence tomography-compatible surgical instruments for real-time image-guided ophthalmic surgery. British Journal of Ophthalmology 101(10), 1306–1308 (2017). 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gan Y, Yao W, Myers KM, Hendon CP: An automated 3d registration method for optical coherence tomography volumes. In: 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. pp. 3873–3876 (August 2014). 10.1109/EMBC.2014.6944469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginner L, Blatter C, Fechtig D, Schmoll T, Gröschl M, Leitgeb R: Wide-Field OCT Angiography at 400 KHz Utilizing Spectral Splitting. Photonics 1(4), 369–379 (2014). 10.3390/photonics1040369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grulkowski I, Liu JJ, Potsaid B, Jayaraman V, Lu CD, Jiang J, Cable AE, Duker JS, Fujimoto JG: Retinal, anterior segment and full eye imaging using ultrahigh speed swept source OCT with vertical-cavity surface emitting lasers. Biomedical Optics Express 3(11), 2733 (November 2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolb JP, Draxinger W, Klee J, Pfeiffer T, Eibl M, Klein T, Wieser W, Huber R: Live video rate volumetric OCT imaging of the retina with multi-MHz A-scan rates. PLOS ONE 14(3), e0213144 (2019). 10.1371/journal.pone.0213144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraus MF, Potsaid B, Mayer MA, Bock R, Baumann B, Liu JJ, Hornegger J, Fujimoto JG: Motion correction in optical coherence tomography volumes on a per A-scan basis using orthogonal scan patterns. Biomedical optics express 3(6), 1182–99 (June 2012). 10.1364/BOE.3.001182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loshchilov I, Hutter F: Decoupled weight decay regularization. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2019) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niemeijer M, Garvin M, Lee K, Ginneken B, Abramoff M, Sonka M: Registration of 3d spectral oct volumes using 3d sift feature point matching. Proceedings of SPIE - The International Society for Optical Engineering (February 2009). 10.1117/12.811906 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niemeijer M, Lee K, Garvin MK, Abràmoff MD, Sonka M: Registration of 3D spectral OCT volumes combining ICP with a graph-based approach. In: Haynor DR, Ourselin S (eds.) Medical Imaging 2012: Image Processing. vol. 8314, pp. 378–386. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE; (2012). 10.1117/12.911104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan L, Guan L, Chen X: Segmentation guided registration for 3d spectral-domain optical coherence tomography images. IEEE Access 7, 138833–138845 (2019). 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2943172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szkulmowski M, Wojtkowski M: Averaging techniques for OCT imaging. Optics Express 21(8), 9757 (April 2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viehland C, Keller B, Carrasco-Zevallos OM, Nankivil D, Shen L, Mangalesh S, Viet du T, Kuo AN, Toth CA, Izatt JA: Enhanced volumetric visualization for real time 4D intraoperative ophthalmic swept-source OCT. Biomed Opt Express 7(5), 1815–1829 (2016). 10.1364/BOE.7.001815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss J, Eck U, Nasseri MA, Maier M, Eslami A, Navab N: Layer-Aware iOCT Volume Rendering for Retinal Surgery. In: Kozlíková B, Linsen L, Vázquez PP, Lawonn K, Raidou RG (eds.) Eurographics Workshop on Visual Computing for Biology and Medicine. The Eurographics Association; (2019). 10.2312/vcbm.20191239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou M, Yu Q, Mahov S, Huang K, Eslami A, Maier M, Lohmann CP, Navab N, Zapp D, Knoll A, Nasseri MA: Towards Robotic-assisted Subretinal Injection: A Hybrid Parallel-Serial Robot System Design and Preliminary Evaluation. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 0046(c), 1–1 (2019). 10.1109/tie.2019.2937041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.