Abstract

Rationale:

Intimate partners and other informal caregivers provide unpaid tangible, emotional, and decision-making support for patients with cancer, but relatively little research has investigated the cancer experiences of sexual minority women (SMW) with cancer and their partners/caregivers.

Objective:

This review centered on 4 questions: 1) What social support do SMW with cancer receive from partners/caregivers? 2) What effect does cancer have on intimate partnerships or caregiving relationships of SMW with cancer? 3) What effects does cancer have on partners/caregivers of SMW with cancer? 4) What interventions exist to support partners/caregivers of SMW or to strengthen the patient-caregiver relationship?

Method:

This systematic review, conducted in 2018 and updated in 2020, was based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Two independent coders screened abstracts and articles.

Results:

550 unique records were screened; 42 articles were assessed for eligibility, and 18 were included in a qualitative synthesis. Most studies were U.S.-based, involved breast cancer, included intimate partners, had primarily white/Caucasian samples, and were cross-sectional. Sexual minority female participants reported that partners/caregivers often provide important social support, including emotional support, decision-making support, and tangible support. Effects of cancer on relationships with partners/caregivers were mixed, with some studies finding relationships remained stable and others finding cancer either increased closeness or disrupted relationships. Participants reported partners/caregivers often experience distress and may experience discrimination, discomfort disclosing sexual orientation, and a lack of sexual minority-friendly services. No studies involved an intervention targeting partners/caregivers or the dyadic relationship.

Conclusion:

More work is needed to understand SMW with cancers other than breast cancer, and future work should include more racially, ethnically, and economically diverse samples. Longitudinal research will allow examination of patterns of mutual influence and change in relationships. These steps will enable development of interventions to support SMW with cancer and people close to them.

Keywords: Sexual minority women, cancer, cancer survivorship, caregiving, dyadic research, systematic review

The Social Context of Cancer for Sexual Minority Women: A Systematic Review

Researchers and clinicians have conceptualized cancer as a “family affair” that affects both patients and people close to them (Institute of Medicine, 2005, Kent et al., 2016, Porter and Dionne-Odom, 2017). Intimate partners, other family members, and friends often serve as informal caregivers for patients with cancer by providing unpaid tangible, emotional, and decision-making support (Arora et al., 2007, Kayser and Scott, 2008, Kent et al., 2016). As the number of cancer survivors and caregivers continues to grow, it is increasingly important to understand and support patients and patient-caregiver dyads who are diverse along a variety of dimensions, including sexual orientation (Kent et al., 2016). A report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommended explicitly and consistently addressing the needs of diverse families when developing supports and policies for caregivers (National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, 2016).

Intimate partnerships (typically indicated by marriage status or “marriage-like” partnerships) often provide important support to women with cancer, although most observational and interventional dyadic research in the context of cancer has involved samples in which heterosexuality is assumed or sexual orientation is not addressed (Dorros et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2008, Litzelman and Yabroff, 2015). Being married has been linked to earlier breast cancer diagnosis and a lower rate of breast cancer-related mortality (Hinyard et al., 2017, Osborne et al., 2005). Findings from married, heterosexual couples and other patient-caregiver pairs in which one member has cancer or another chronic disease have shown that patients’ and caregivers’ health and wellbeing are interconnected (Dorros et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2008, Litzelman and Yabroff, 2015, Litzelman et al., 2016, Valle et al., 2013). Experiencing cancer as a couple may lead patients and partners to report increased feelings of closeness (Dorval et al., 2005, Drabe et al., 2013), but partners and other informal caregivers may also face distress and physical burdens due to cancer caregiving (Kim et al., 2015a, Kim et al., 2015b, Kim and Given, 2008). Such findings have led to the development of psychosocial dyadic interventions for cancer patients and their partners or other informal caregivers (Northouse et al., 2010, Regan et al., 2012, Rush et al., 2015).

It is unclear whether findings in heterosexual women can be generalized to sexual minority women (SMW), especially given research showing the effects of gender roles on health in heterosexual partnerships. A meta-analysis of distress in (presumed heterosexual) couples in which one member had cancer found that women exhibited greater distress than their male partners, regardless of role (patient vs. partner); the authors note that it would be inappropriate to assume findings from their review would hold true in same-gender partnerships (Hagedoorn et al., 2008). Prior research comparing the “health behavior work” (i.e., activities to promote a partner’s positive health behaviors) in heterosexual, lesbian, and gay couples found that lesbian and gay couples were more likely to engage in “cooperative health behavior work” (both partners taking care of each other’s health) rather than relying on gendered assumptions about women’s role as caretakers (Reczek and Umberson, 2012). SMW often build their own social and community ties, and they may be more likely to enjoy intimate partnerships free of predefined roles such as the patriarchal power structures and gender roles often assumed in heterosexual relationships (Riggle et al., 2008). At the same time, the social worlds of SMW are often shaped by social stigma (Meyer, 2007), family and social rejection (Meyer, 2007, Ryan et al., 2009), and, for bisexual women, difficulties in maintaining intimate partnerships (Klesse, 2011, Li et al., 2013). General social support may be particularly difficult to obtain for bisexual women who experience stigma in both gay/lesbian and heterosexual communities (Balsam and Mohr, 2007, Mitchell et al., 2015).

Minority stress theory is often used to explain health impacts of this social context uniquely faced by minority populations (Meyer, 1995, Meyer, 2003, Meyer, 2007). This theory postulates that social support from accepting family, friends, and community is a buffer to discrimination experienced externally (e.g., violence, rejection) and internally (i.e., internalized homophobia) (Meyer, 2003). Most SMW seek and create their own communities of acceptance and support through partners and with the larger sexual and gender minority community (Dewaele et al., 2011, Gabrielson, 2011). Studies on the social worlds of SMW demonstrate the significance of social relationships, particularly family of origin (Heiden-Rootes et al., 2019) and intimate partnerships (Otis et al., 2006) for predicting positive mental health for SMW. Further, the relationship between mental health and intimate partnerships seems to be bidirectional, with more minority stress, as measured by stigma and internalized homophobia, predicting increased conflict, violence (Balsam and Szymanski, 2005), and decreased relationship satisfaction (Frost and Meyer, 2009). This seems to be a recursive process whereby minority stress impacts social relationships and social relationships impact degree of felt stress. It is unclear, however, how this process unfolds for SMW who face cancer.

Limited research has examined the experiences of SMW along the cancer prevention and control continuum. Some research exists on cancer screening (e.g., Brown and Tracy, 2008, McElroy et al., 2015) and on cancer risk, prevalence, or incidence (Blosnich et al., 2016, Cochran et al., 2001, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Hoy-Ellis, & Brown, 2015, Meads and Moore, 2013, Trinh et al., 2017, Valanis et al., 2000), although the lack of any cancer registry systematically collecting information on sexual minority status limits the generalizability of the current findings. In terms of mental health outcomes, a recent review found few differences among SMW with cancer compared to heterosexual women with cancer, but the authors advised interpreting these findings with caution due to the small number of included studies (Gordon et al., 2019). Even less is known about the supportive relationships of SMW in the context of cancer survivorship, despite the fact that social support from diagnosis to post-treatment appears to be significantly associated with cancer progression and outcome, particularly for female patients with breast cancer (Nausheen et al., 2009). Although prior reviews examining the cancer care experiences of sexual minority women have touched on social support conceived broadly (Hill and Holborn, 2015, Kent et al., 2019, Lisy et al., 2018) none has focused on partners/caregivers in particular or the dyadic relationship between patients and partners/caregivers.

This systematic review was designed to examine the research about the support SMW receive from their partners or other informal caregivers, as well as the impact of cancer on partners/caregivers and the dyadic relationship. The review was focused on four research questions:

What social support do SMW with cancer receive from intimate partners or informal caregivers?

What effect does cancer have on the intimate partnerships or informal caregiving relationships of SMW with cancer?

What effects does cancer have on the mental health, physical health, and/or quality of life of intimate partners or informal caregivers of SMW with cancer?

What interventions have been developed to support intimate partners or informal caregivers of SMW or to strengthen the patient-caregiver dyad?

Method

The authors adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines in the search process and in the reporting of results (Moher et al., 2009). The search strategy was developed and conducted in stages. First, initial meetings were held by three authors (TT, KHR, and MJ), one of whom (MJ) is a research librarian, to review preliminary research questions and draft literature search parameters. Next, preliminary searches were conducted in a range of databases (CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Medline, PsycINFO, Social Work Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts) to identify research articles about the experiences of SMW with cancer, including the effects of cancer on intimate partners/informal caregivers of SMW; the effects of cancer on relationships in SMW with cancer; and the effectiveness of interventions developed to support intimate partners/informal caregivers of SMW with cancer. The initial research topics included Research Questions 2-4 above; because a preliminary review of the search results suggested that limited empirical research addressed those questions, the review was broadened to include Research Question 1 as well.

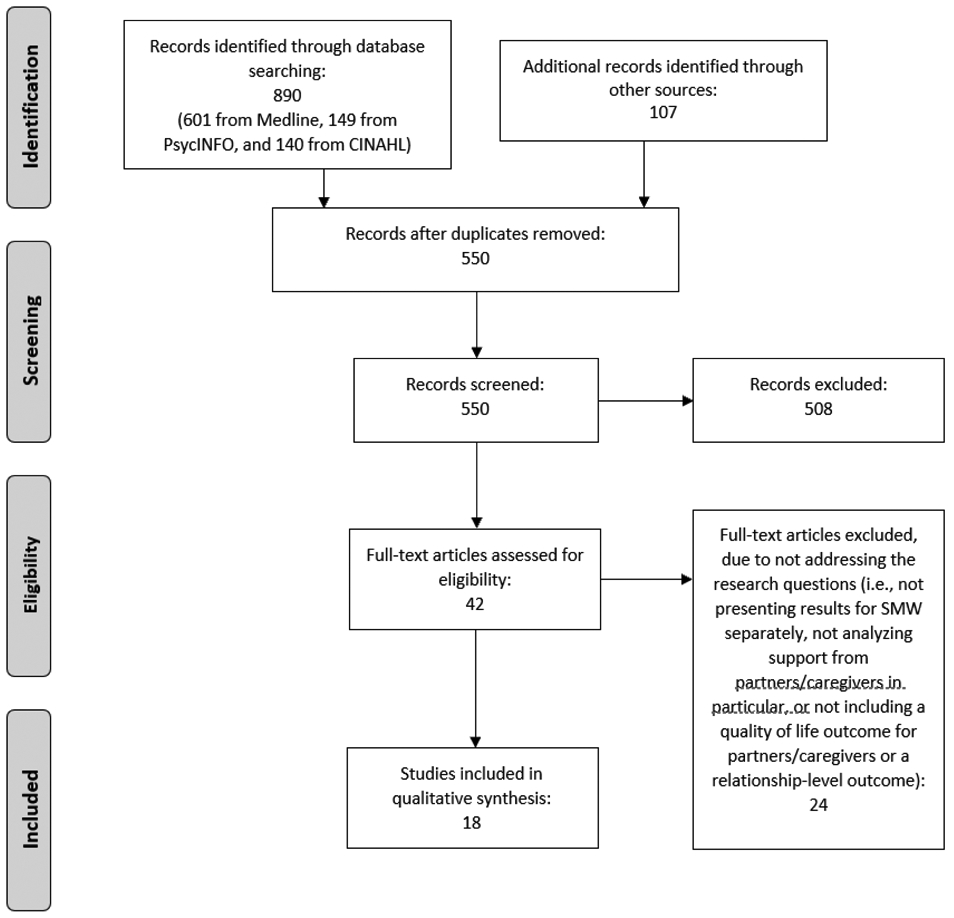

The results of the preliminary searches showed Medline and PsycINFO to be the dominant databases for this review, with other databases yielding primarily duplicates. Potential search terms for each database were evaluated to ensure topical coverage. Official database subject terms were applied when available in databases having internal vocabulary structures; otherwise, keyword searches were conducted. Terms were used to search for the five most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancers among women in the U.S. – breast, lungs/bronchus, colon/rectum, uterine corpus, and thyroid (Siegel et al., 2019). Final searches were conducted with Medline and PsycINFO between August 5 – October 5, 2018 by the research librarian. Additional references (Figure 1, “Additional records identified through other sources”) were identified by the first three authors by searching reference lists. Reference lists of articles from the initial search results that seemed especially relevant to the research questions were examined by hand, and a dissertation database (Dissertations & Theses Global, 1996 – 2018) was searched to identify topical dissertations whose bibliographies were examined for additional related publications.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of studies included in qualitative synthesis

An updated search was conducted by the research librarian on March 8, 2020. Based on comments from anonymous reviewers, the updated search included broader search terms (i.e., neoplasm and cancer in addition to site-specific cancers) as well an additional database (CINAHL). See the Online Supplement for full search details of all 2018 and 2020 searches.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles that met the following criteria were included: (1) published in peer-reviewed journals (including online advance publication) in English by March 2020, (2) described empirical quantitative or qualitative research; (3) addressed one of the review questions: the social support SMW with cancer receive from intimate partners or informal caregivers; the effect of cancer on the intimate partnerships or informal caregiving relationships of SMW with cancer; the effect of cancer on intimate partners or informal caregivers of SMW with cancer; and the interventions that have been developed to support intimate partners/informal caregivers of SMW or to strengthen the patient-caregiver dyad. If study samples included both men and women with cancer, or both sexual minority and non-SMW, the articles were required to analyze SMW separately to be included.

The following types of studies were excluded: Studies about cancer prevention or screening; studies in which the majority of the sample had HIV-related cancers; studies of the effectiveness of cancer treatments; case studies, review articles, or commentaries; and studies that did not include at least one of the following: an assessment or exploration of partner- or caregiver-specific social support for patients, quality of life (mental or physical health) for caregivers/partners, or relationship outcomes.

Data Analysis

After duplicate citations were removed, each abstract was reviewed independently by two authors (TT, KHR, LJ, LAG, EA, CP, MB, JM) to determine which articles should be included in the full text review. In the event of disagreement between reviewers, the first and second authors made the final decision. Pairs of authors (TT, KHR, LJ, LAG) then independently reviewed all full texts selected and determined whether they should be included in the final analysis, with discrepancies again resolved through discussion by the first and second authors. During the data extraction process, the first and second author determined that one article that had been excluded at the abstract review stage should have been included (Arena et al., 2007), and that one article that had been selected for data extraction did not sufficiently address the research questions (Bazzi et al., 2018); these changes were made and documented.

The first and second author developed a data extraction form, tested it independently on two articles, made further modifications, and then used it to extract data from all articles. Information on the form included sample size, inclusion/exclusion criteria, sample characteristics, type(s) of cancer, any theory informing the research questions addressed by the study (that is, a theory or framework described in either Introduction or Methods as informing the research questions or study design), measures (for quantitative studies), interview domains (for qualitative studies), the definition of “sexual minority” used by the authors, the definition of partner/informal caregiver, study design and analytic methods, findings, and limitations (both those noted by study authors and those noted by the research team). Information about sample characteristics included age, race/ethnicity, and income; when income was not available, another measure of socioeconomic status (SES; e.g., education, having private health insurance) was included if available. Measures listed in Tables 1 and 2 include only those used in the extracted findings; many studies included other measures that were not used in answering our research questions. The first and second authors extracted data from all articles independently and then discussed their findings to reach consensus.

Table 1.

Quantitative studies included in review (n = 10)

| Citation | Type of cancer |

Sample size | Sample characteristics |

Sexual minority definition |

Partner/ caregiver definition |

Study design/ analysis |

Quality of life/social support measures |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arena et al., 2007. Psychosocial responses to treatment for breast cancer among lesbian and heterosexual women. Women and Health 44, 81-102. | Breast Up to and including Stage 2 |

39 lesbian women, 39 heterosexual women (HSW) | Lesbian participants: mean age 48, mean 17 years education; 92% non-Hispanic white | Self-identification as a lesbian | Married/partnered | Cross-sectional mail survey Not dyadic Bivariate statistics and regression |

Profile of Concerns about Breast Cancer (Spencer et al., 1999) Measure of Body Apperception (Carver et al., 1998) Quality of Marriage Index (Norton, 1983) Psychosexual adjustment (Carver et al., 1998) Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale, Sexual Relations subscale (Derogatis, 1975) |

On Profile of Concerns about Breast Cancer Sexual Concerns subscale, HSW scored significantly higher than lesbian women. On the Measure of Body Apperception subscale, physical appearance concerns were significantly higher among HSW. HSW reported significantly higher sexual disruption; they also reported more frequent partner-initiated sex pre-surgery. There were no significant differences between lesbian and HSW in relationship satisfaction, partner bother due to scar, partner expressing affection, fighting/friction, and partner reaction to threat to life. |

| Boehmer, Glickman, Winter, & Clark, 2013a. Breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations: Which factors explain survivors’ quality of life and adjustment? Annals of Oncology, 24, 1622-1630. | Breast Stage 0-3, not metastatic or recurrent |

257 heterosexual women, 183 sexual minority women (SMW) | SMW: Mean age 55; 68% individual income < $70,000; 99.5% college degree or higher; 90% White | Women who reported being lesbian or bisexual, or partnering with women | Spouse/partner | Cross-sectional telephone survey Not dyadic Bivariate statistics and regression |

Medical Outcomes Study SF-12 (Ware et al., 1996) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983) |

Sexual orientation affected physical quality of life via interactions with partner status. Association between having a partner and better SF-12 physical health was stronger for SMW than HSW women. Not being married was associated with more HADS depressive symptoms for both SMW and HSW. Living with a partner was associated with higher HADS anxiety, which was stronger for SMW. |

| Boehmer, Glickman, Winter, & Clark, 2013b. Lesbian and bisexual women’s adjustment after a breast cancer diagnosis. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 19, 280-292. | Breast Stage 0-3, not metastatic or recurrent |

180 lesbian and bisexual women | Lesbian participants: Mean age 55; 68% individual income < $70,000; 99 % college degree or higher; 89% white Bisexual participants: Mean age 56; 74% individual income < $70,000; 100% college degree or higher; 95% white |

Sexual identity and preference for sex of partner | Spouse/partner | Cross-sectional telephone survey Not dyadic Bivariate statistics and regression |

Medical Outcomes Study SF-12 (Ware et al., 1996) HADS (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983) |

Lesbian and bisexual women had different marriage/living arrangements; lesbian women more likely to have a partner and report living with partners. Being separated, divorced, widowed, never married associated with lower HADS anxiety. Better SF-12 physical health associated with having a partner. Being partnered with a man associated with worse SF-12 mental health compared to having no partner. Relationship status/cohabitation not related to HADS depression. |

| Boehmer, Freund, & Linde, 2005. Support providers of sexual minority women with breast cancer: Who they are and how they impact the breast cancer experience. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 59, 307-314. | Breast Not metastatic or recurrent |

30 sexual minority women and 24 support providers | Women without support providers: Mean age 53, 86% white, 86% college education or higher Women with support providers: Mean age 51, 91% white, 100% college education or higher Support providers: Mean age 50, 92% white, 96% college education or higher |

Women who reported being lesbian or bisexual or partnering with women | A “trusted other” (“their most important support person with respect to their cancer care…other than their treating physician,” p. 308) | Cross-sectional self-administered survey Dyadic Bivariate statistics and regression |

Profile of Mood States (11-item POMS) (McNair et al., 1971) Medical Outcomes Social Support Study (5 items) (Sherbourne and Stewart, 1991) Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer (Watson et al., 1994) (Subscales: Fighting Spirit, Helplessness-hopelessness, Anxious Preoccupation, Fatalism, and Cognitive Avoidance) |

80% of patients identified a support person; 79% were partners. Women who enrolled support people reported significantly more social support. Women and support providers had good agreement on assessment of patients' fatalism, cognitive avoidance, and anxious preoccupation, but less agreement with helplessness/hopelessness and fighting spirit. Level of sexual orientation disclosure ("outness") was related to POMS distress for both patients and support providers; discordance in disclosure was related to higher distress among patients. |

| Boehmer, Stokes, Bazzi, Winter, & Clark, 2018. Dyadic stress of breast cancer survivors and their caregivers: Are there differences by sexual orientation? Psycho-Oncology, 27, 2389-2397. | Breast Not metastatic or recurrent |

167 dyads of cancer survivors (124 of whom were SMW) and their caregivers | SMW cancer survivors: Mean age 56, 92% white, 60% individual income <$70,000. Caregivers to SMW: Average age 56, 90% white, 61% individual income < $70,000 |

Self-identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or preferring a same-sex partner | If partnered, spouse was considered their caregiver; if not partnered, identified “the most important support person to them” (p. 803) | Cross-sectional telephone survey Dyadic Bivariate analyses; simultaneous equation models |

Perceived Stress Scale (10-item version) (Cohen and Williamson, 1988), given to both patients and caregivers; Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976)(2 subscales: Dyadic Cohesion, Dyadic Satisfaction) | Survivor and caregiver stress scores did not differ among heterosexual or sexual minority couples. Survivor and caregiver stress was significantly correlated overall; in stratified analyses, there was a significant positive correlation in stress between SMW and their caregivers but not between HSW and their caregivers. In dyads with SMW, caregiver stress was significantly associated with patient stress, a pattern not present in dyads with HSW patients. Note: Bivariate and descriptive results in this paper are the same as those in Boehmer, Tripodis et al. (2016) below. |

| Boehmer, Timm, Ozonoff, & Potter, 2012. Explanatory factors of sexual function in sexual minority women breast cancer survivors. Annals of Oncology 23, 2873-2878. | Breast Stage 0-3, not metastatic |

170 sexual minority women, 85 with a history of cancer and 85 controls with no cancer history | Cancer survivors: Mean age 52, 92% white, 77% individual income <$70,000 Controls: Mean age 51, 85% white, 72% individual income <$70,000 |

Self-identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or preferring a same-sex partner | Partner | Cross-sectional mailed survey Not dyadic Bivariate analyses; regression |

Female Sexual Index Function (Rosen et al., 2000); Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976) (2 subscales: Dyadic Cohesion and Dyadic Satisfaction) | Dyadic cohesion and dyadic satisfaction were not significantly different between breast cancer survivors and noncancer controls in bivariate analyses. Noncancer controls were more likely than survivors to report their partner had a sexual problem. In multivariate models, dyadic cohesion was a predictor of female sexual function in models with both cases and controls (adjusting for case/control status). |

| Boehmer, Tripodis, Bazzi, Winter, & Clark, 2016. Fear of cancer recurrence in survivor and caregiver dyads: differences by sexual orientation and how dyad members influence each other. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 10, 802-813. | Breast Not metastatic or recurrent |

167 dyads of cancer survivors (124 of whom were SMW) and their caregivers | Sexual minority cancer survivors: Mean age 56, 92% white, 60% individual income <$70,000. Caregivers to SMW: Average age 56, 90% white, 58% individual income < $70,000 |

Self-identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or preferring a same-sex partner | If partnered, spouse was considered their caregiver; if not partnered, identified their most important support person | Cross-sectional telephone survey Dyadic Bivariate analyses; simultaneous equation models |

Fear of Recurrence scale (Northouse, 1981) Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (Zimet et al., 2000) (3 subscales: Family, Friends, Significant Other) Dyadic Cohesion subscale from Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976) Discrimination experience (7 yes/no items) Effect of cancer on relationship (1 item adapted from Dorval et al., 2005) |

Caregivers for HSW had lower significant other support than did caregivers for SMW. SMW reported higher friend support than HSW, as did caregivers for SMW compared to caregivers for HSW. SMW reported more discrimination than HSW, and their caregivers reported more discrimination than did caregivers for HSW. There were no significant differences in dyadic cohesion between HSW and SMW with cancer, or between their caregivers in dyadic cohesion, fear of recurrence, or effect of cancer on the relationship. The majority of HSW, SMW, and their caregivers reported that cancer brought them closer. |

| Fobair, O'Hanlan, Koopman, Classen, Dimiceli, Drooker, Warner, Davids, Loulan, & Wallstenm, 2001. Comparison of lesbian and heterosexual women’s response to newly diagnosed breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 10, 40-51. | Breast Stage 1-3A, not metastatic (other than adjacent lymph nodes), not recurrent |

29 lesbian women and 246 heterosexual women | Demographic characteristics not described.* | Self-identification as a lesbian | Partner | Cross-sectional survey Not dyadic Bivariate analyses |

Social Network and Support Assessment (Berkman and Syme, 1979) | Compared to HSW, lesbians reported higher support from their partners, including feeling loved and cared for, feeling listened to, and being able to depend on partners for help with day-to-day tasks. Lesbians were less likely than HSW to report their partners were too demanding. |

| Fobair, Koopman, Dimiceli, O'Hanlan, Butler, Classen, Drooker, Davids, Loulan, & Wallsten, 2002. Psychosocial intervention for lesbians with primary breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 11, 427-438. | Breast Stage 1-3A, not metastatic (other than adjacent lymph nodes), not recurrent |

20 lesbian women | Mean age 47, predominantly European American, 70% earned $60,000 or less | Self-identification as a lesbian | Partner | Longitudinal cohort study assessed by surveys Not dyadic Descriptive statistics; within-subjects slopes analysis |

1 item assessing partnership status | 67% of women in the sample were partnered and remained partnered in the year following treatment. |

| Kamen, Smith-Stoner, Heckler, Flannery, & Margolies, 2015. Social support, self-rated health, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity disclosure to cancer care providers. Oncology Nursing Forum, 42, 44-51. | All types of cancer | 291 people with cancer | Entire sample: 88% non-Hispanic Caucasian, 42% female | Self-identification as lesbian, bisexual gay, or transgender | Partner | Cross-sectional online survey Not dyadic Descriptive and bivariate statistics; regression; tree analysis |

2 items developed by the study team | In bivariate analyses, compared to gay and bisexual men, lesbian and bisexual women more often had an intimate partner in the room when they received a cancer diagnosis. Compared to gay and bisexual men, more lesbian and bisexual women reported having a partner as part of their emotional support team. |

The text of this article refers to demographic information included in Table 1, but tables seem to have been inadvertently omitted from the text when published. Attempts to obtain the tables from the first author and the publisher were unsuccessful. Fobair et al. (2002) involves a subsample of Fobair et al. (2001) participants, so it is reasonable to assume the demographic characteristics are similar.

Table 2.

Qualitative and mixed methods studies included in review (n = 8)

| Citation | Type of cancer |

Sample size | Sample characteristics |

Definition of sexual minority |

Definition of caregiver/ partner |

Study design/analysis |

Study domains | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boehmer, Linde, & Freund, 2007. Breast reconstruction following mastectomy for breast cancer: The decisions of sexual minority women. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, 119, 464-472. | Breast Not metastatic or recurrent; underwent mastectomy |

15 sexual minority women who were patients; 12 support people | Patients who did not undergo reconstruction: Mean age 51, 100% white, mean income for one person $57,857 Patients who underwent reconstruction: Mean age 47, 88% white, mean income for one person $52,000, mean income for more than one person $41,667 Caregivers for women without reconstruction: Mean age 49, 75% white, mean income for one person $73,333, mean income for more than one person $55,000 Caregivers for women with reconstruction: Mean age 50, 88% white, mean income for one person $44,167, mean income for more than one person $100,000 |

Women who reported being lesbian or bisexual or partnering with women | “Trusted other”: “most important support person with respect to their cancer care… other than their treating physician” (p. 465). | Qualitative interview Dyadic Descriptive statistics and grounded theory |

Body image, support and satisfaction with reconstruction decision, partner's feeling about decision, impact on relationship | Support people provided decision-making support about whether to undergo reconstruction. Partners were more involved in the process than other support people; they found out more details and expressed more preferences about reconstruction. There was more concordance in decision making among couples in which the patient chose not to have reconstruction. |

| Bristowe, Hodson, Wee, Almack, Johnson, Daveson, Koffman, McEnhill, & Harding, 2018. Recommendations to reduce inequalities for LGBT people facing advanced illness: ACCESSCare national qualitative interview study. Palliative Medicine 32, 23-35. | Any “advanced disease,” including cancer | 40 lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender people (20 patients, 6 current caregivers, 14 bereaved caregivers); 21 had experience with cancer | Entire sample: 95% white (34 white British, 4 white other); 68% were in their 50s or 60s | Self-identification as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender | Unpaid caregiver | Qualitative interview Not dyadic Inductive thematic analysis |

Illness narrative; disclosing identity to health care professionals; partner involvement; support; barriers to care | Participants reported relying on a partner for support during cancer, as well as the isolation that could occur after the death of a partner from cancer. Some patients or partners reported that health care providers did not acknowledge their relationship, and they stated that overt acknowledgement from providers was helpful. Some partners of cancer patients were reluctant to attend support groups unless they were known to be LGBT-friendly, but others said other dimensions of their identity (i.e., age, religion) were more salient. |

| Brown & McElroy, 2018. Unmet support needs of sexual and gender minority breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26, 1189-1196. | Breast | 67 sexual minority breast cancer survivors | Full sample: 75% 45 or older; 91% white | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer | Partner | Cross-sectional internet survey Not dyadic Mixed methods: bivariate analysis of quantitative data and thematic analysis of open-ended responses |

Impact of breast cancer on life and relationships | 58% were in an intimate partnership at the time of survey administration. 40% of respondents reported their sexual or gender identity mattered as far as getting support for them and their partner. In open-ended responses, many said they thought disclosing their status/relationship to care providers was helpful; it increased trust and reduced stress. Participants reported that treatment had an effect on sexuality and intimate partnerships, with treatment reducing sex drive. |

| Fish, Williamson, & Brown, 2019. Disclosure in lesbian, gay and bisexual cancer care: Towards a salutogenic healthcare environment. BMC Cancer, 19, 678. | Any cancer Diagnosed within the past 5 years |

30 lesbian, gay, or bisexual participants (including 12 SMW, 9 of whom had breast cancer) | Age range: 24-65+; none were from Black or Minority Ethnic communities | Lesbian or bisexual | Partner | Qualitative interview Not dyadic Thematic analysis |

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual people's experiences of disclosure and nondisclosure in health care settings, interactions with health professionals, perceptions of cancer care | Partners of cancer patients are a salutogenic resource that medical staff can leverage as long as they are comfortable with the relationship. Sometimes fear of being outed can prevent patients from drawing on partner support in medical settings. |

| Matthews, Peterman, Delaney, Menard, & Brandenburg, 2002. A qualitative exploration of the experiences of lesbian and heterosexual patients with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 29, 1455-62. | Breast | 13 lesbian women and 28 heterosexual women (HSW) with breast cancer | Lesbian women: Mean age 51, 85% white, 61% with household income over $50,000 | Self-identification as a lesbian | Partner; also “someone to assist me with coping with my illness” and “someone to accompany me to my medical appointments” (p. 1457) | Focus groups plus a self-report survey Not dyadic Descriptive statistics, thematic analysis and representative case study methods |

Attitudes about medical decision making, cancer supportive services, satisfaction with health care, use of alternative/complementary therapies, | All lesbians reported having someone to assist them in coping (as did 96% of HSW), and 69% reported having someone available to attend medical appointments with them (compared to 46% of HSW). Of the 5 lesbian women in long-term relationships, 4 were satisfied with the emotional support their partner received from medical providers, and all were satisfied with the inclusion of their partner in medical decisions. In focus groups of both lesbians and HSW, partners were most frequently mentioned as a source of support. Lesbian women reported medical staff treated partners respectfully. |

| Paul, Pitagora, Brown, Tworecke, & Rubin, 2014. Support needs and resources of sexual minority women with breast cancer. Psycho-Onology, 23, 578-584. | Breast Underwent mastectomy |

13 sexual minority women with breast cancer | Mean age 44, 92% white, median family income $70,000-89,999 | Self-identification as lesbian, bisexual, gay, or queer | Partner | Qualitative interview Not dyadic Thematic analysis |

Decision making after breast reconstruction; support needs and concerns | 54% were in long-term relationships at the time of the study. Partnered women noted difficulty finding support groups for female partners; general support groups might not feel safe or appropriate. Seven people noted relationships were disrupted or dissolved by cancer. Young single women were more likely to rely on parents as their main support. Single, middle-aged women had less support overall. Some sought support from former partners. Some partners were very supportive and helped patients adjust to post-treatment bodies and acted as advocates in medical contexts. |

| Sinding, Grassau, & Barnoff, 2007. Community support, community values: The experiences of lesbians diagnosed with cancer. Women and Health, 44, 59-79. | Breast or gynecologic | 23 lesbian women (22 breast cancer, 3 gynecologic cancer, 1 both) | Entire sample: Mean age 50, majority white/European descent, 65% household income < $70,000 Canadian | Self-identification as a lesbian (women whose “primary emotional and sexual relationships are with women,” p. 62) | Partner | Qualitative interview Not dyadic Participatory action research; grounded theory techniques |

Cancer experiences; support of partners, friends, and broader lesbian community | Women reported receiving support from partners; some believed lesbians had more support than HSW. Some reported that because their partners were women, they were empathic and understanding. A smaller number reported not receiving adequate emotional support or communication from partners. The fact that participants and partners were the same gender was seen as helpful in some ways (“My partner has ovaries. My partner has a uterus. My partner could be in my position” [p. 67]) but unhelpful in others (i.e., having similar bodies may make partners acutely aware of the changes patients go through). Although some women believed mastectomy was not as problematic for lesbians because their partners did not value breasts as much as male partners did, at least one woman reported she did not find that to be true in sexual encounters after her surgery. |

| White, & Boehmer, 2012. Long-term breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of support from female partners: an exploratory study. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, 210-217. | Breast Not metastatic |

15 sexual minority women | Mean age 52, 87% white | Self-identification as lesbian or bisexual, or preference for a female partner | Partner | Qualitative interview Not dyadic Thematic analysis |

Effects of cancer on women’s lives; cancer-related coping; sources and types of social support | Main themes: 1) Female partners were the primary source of social support; 2) Partners helped survivors manage health and distress; 3) Partners were often perceived as being distressed themselves; 4) Partners contributed in tangible ways (cooking, child care, other housework); 5) Partners were perceived as experiencing burdens of caregiving; 6) Partners provided support by helping survivors have lives that are “pleasurable, forward-looking, and otherwise not centered on breast cancer” (p. 214) |

In order to assess analytic rigor and potential for bias in studies that were primarily observational and extremely heterogeneous in terms of methods, the authors modified four items from the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist (Von Elm et al., 2007) and the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklist (O’Brien et al., 2014). These items were assessed during data extraction and discussed by the first and second author. The items were as follows: 1) The authors describe the eligibility criteria and the sources, methods, and rationale of participant selection; 2) The authors describe the characteristics of study participants (coded “yes” if the authors provided information about age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status); 3) The authors describe and provide a rationale for their quantitative or qualitative analytic methods; and 4) The authors discuss the limitations of the study, including sources of potential bias or imprecision. The source of funding was also noted for all studies. The potential for bias across studies was assessed by the first and second author after examining data extraction results.

Results

A total of 890 records were identified through database searching, and 107 additional records were identified through manual searching of several articles identified by the authors as key references (see Figure 1 and Online Supplement). Once duplicates were removed from the 997 records, 550 abstracts were screened, with 42 full-text articles assessed for eligibility. A total of 18 articles are included in this qualitative synthesis. See Tables 1 and 2 for included studies.

Samples from several of the included studies overlapped, either completely or in part. The cohort recruited by Boehmer and colleagues (described in (Boehmer et al., 2010, Boehmer et al., 2011)) includes a sample of lesbian and bisexual women analyzed in Boehmer, Glickman, et al. (2013b), a subsample of whom were interviewed for a later qualitative study (White and Boehmer, 2012). Some of the 167 patient-caregiver pairs included in Boehmer, Tripodis et al. (2016) and Boehmer, Stokes, Bazzi et al., (2018) were recruited by re-contacting participants from this cohort. In addition, Fobair et al. (2002) included a subsample of participants from Fobair et al. (2001). Each article was analyzed as an individual study because different variables and outcomes were examined in each analysis.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Most studies (12) were conducted in the United States; two were conducted in the United Kingdom, and one was conducted in Canada. Three articles did not explicitly state the study settings, but all three were conducted by United States-based research teams. The majority of participants across studies were fairly high SES and employed. The samples were dominated by participants (both patients and partners/caregivers) who self-identified as white or Caucasian, despite efforts described by researchers in four studies to recruit more racially/ethnically diverse participants (Boehmer et al., 2016, Bristowe et al., 2018, Matthews et al., 2002, Sinding et al., 2007). When sexual orientation was identified in 11 of the studies, lesbian was the most common identity reported, followed by bisexual. Seven studies did not specify sexual orientation and instead grouped participants under the umbrella term “sexual minority women,” defining it broadly to include lesbian, bisexual, and women partnered with women.

Fourteen of the 18 articles included SMW who had breast cancer; of those, 11 restricted participation to exclude later stage or metastatic patients. The four articles that included people with cancers other than breast cancer included two open to participants who had been diagnosed with any type of cancer (Fish et al., 2019, Kamen et al., 2015), one that included patients with “any advanced disease” (including 16 participants with cancer) (Bristowe et al., 2018), and one with patients who had breast or gynecologic cancer (Sinding et al., 2007).

Intimate partners were the most common type of support person described. Most studies (12) examined data from or about partners; one analyzed “unpaid caregivers” (Bristowe et al., 2018), two analyzed “trusted others” (e.g., “their most important support person with respect to their cancer care… other than their treating physician,” (p. 308) (Boehmer et al., 2005, Boehmer et al., 2007), and three used multiple definitions that included both intimate partners and caregivers (Boehmer et al., 2016, Boehmer et al., 2018, Matthews et al., 2002). Thirteen articles included data from patients with cancer only, and no articles included data from partners/informal caregivers only. Five articles included data collected from both patients and partners/informal caregivers, and four of those studies included dyadic analyses.

The majority of articles (12) did not make explicit mention of a theory or conceptual framework underlying the research questions. In one study (Matthews et al., 2002), the authors stated that they were deliberately using qualitative methods to generate hypotheses without a theoretical or conceptual model. Of the six studies that included a theory or conceptual framework informing the research questions, two (Boehmer et al., 2013b, Boehmer et al., 2018) cited minority stress theory (Meyer, 1995), one (Boehmer et al., 2018) cited the stress and coping framework (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), one (Boehmer et al., 2012) cited the conceptual framework for sexual functioning of breast cancer survivors (Ganz et al., 1999), one (Bristowe et al., 2018) cited theories of palliative care (World Health Organization, 2019), and one (Fish et al., 2019) cited the salutogenic model (Antonovsky, 1996).

Table 1 presents findings from quantitative studies, and Table 2 presents findings from qualitative and mixed methods studies. Findings for our individual research questions are discussed below.

Support Sexual Minority Women Receive from Partners/Caregivers

Many of the included studies indicated that partners and other informal caregivers provide important social support for SMW with cancer (Bristowe et al., 2018, Matthews et al., 2002, Paul et al., 2014, Sinding et al., 2007). SMW with cancer reported having an intimate partner in the room when they received a cancer diagnosis more often than did gay and bisexual men, and more SMW reported having a partner as part of their emotional support team (Kamen et al., 2015). Several studies make clear that SMW’s female partners, in particular, are a key source of emotional and instrumental support during the cancer journey (Bristowe et al., 2018, Matthews et al., 2002, Paul et al., 2014), with partners helping survivors manage their health, psychological distress, tangible needs (e.g., cooking, child care), and constructing lives that are “pleasurable, forward-looking, and otherwise not centered on breast cancer” (White and Boehmer, 2012) (p. 214).

There was evidence that the degree and type of support SMW experienced was affected by factors such as relationship status (being partnered or not), nature of the relationship (e.g., partner or friend/family member), and degree of sexual orientation disclosure (“outness”). Compared to other types of support people (e.g., friends, sisters, parents), partners were more likely to find out details about treatment, share in decision making, express more preferences about reconstruction, support adjustment to post-treatment bodies, and act as advocates in medical contexts (Boehmer et al., 2007). Sexual orientation disclosure (“outness”) seemed to affect the level of support that patients received from informal caregivers. In a study of 30 sexual minority women with breast cancer and 24 support persons (the majority of whom were partners), discordance in outness between patients and their support person was related to higher mood disturbance among patients (Boehmer et al., 2005). Similarly, a qualitative study that included nine partnered women with cancer (primarily breast cancer) found fear of being outed could prevent patients from drawing on partner support in medical settings (Fish et al., 2019). In addition to support from current partners, Paul et al. (2014) also found some SMW participants sought emotional and tangible support from former same-sex partners.

Several studies suggested partnerships may provide unique or enhanced benefits to SMW. In interviews, many SMW participants said they believed SMW in same-gender partnerships had more support than heterosexual women, in part because respondents believed female partners are more empathic and understanding than male partners, and female partners shared physical similarities that could promote empathy; a smaller number, however, reported not receiving adequate emotional support or communication from female partners (Sinding et al., 2007). For bisexual and lesbian women, having a partner was associated with better physical quality of life for both groups (Boehmer et al., 2013b); in contrast, being separated, divorced, widowed, or never married was associated with lower anxiety (Boehmer et al., 2013b). In that study, relationship status was not related to depressive symptoms overall, but being partnered with a man was associated with worse mental health quality of life compared to having no partner (Boehmer et al., 2013b).

Findings indicate that the effects of partnerships for SMW may vary depending on the particular quality of life outcomes being studied. In a sample of breast cancer survivors, lesbian women were more likely than heterosexual women to being able to depend on partners for help with day-to-day tasks and less likely to report their partners were too demanding (Fobair et al., 2001). Boehmer and colleagues (Boehmer et al., 2013a) found sexual orientation affected physical quality of life through interactions with partner status such that the association between having a partner and better physical quality of life was stronger for SMW than heterosexual women. In that sample, living with a partner was associated with higher levels of anxiety, an association which was stronger for SMW than for heterosexual women, but not being married was associated with more depressive symptoms for both SMW and heterosexual women (Boehmer et al., 2013a).

Effect of Cancer on Relationships with Partners or Informal Caregivers

Many studies explored the effect of cancer on the relationship between SMW participants and their partners or informal caregivers. Research questions included the quality and stability of partnerships (Arena et al., 2007, Fobair et al., 2002, Paul et al., 2014), decision making (Boehmer et al., 2007, Sinding et al., 2007), and sexual concerns (Arena et al., 2007, Brown and McElroy, 2018). The relationship was often assessed based on the dyadic influence of the partner or informal caregiver on the SMW with cancer, or in qualitative interviews that posed retrospective questions about the nature of the relationship and the effect of cancer.

Findings on stability and quality of relationships during and after cancer treatment for SMW were inconsistent. The one longitudinal study (Fobair et al., 2002) described stability in partner relationships over a one-year period for the two-thirds of women who were partnered at the beginning of the study. In contrast, Paul et al. (2014) found seven out of thirteen SMW described intimate partnerships being disrupted or dissolved during treatment for breast cancer.

For breast cancer patients in particular, decisions about surgery and reconstruction may affect relationships. In a sample of SMW who underwent mastectomy, Boehmer, Linde, and Freund (2007) found there was more concordance in decision making among patients and intimate partners in couples in which the patient chose not to have reconstruction. Sinding et al. (2007) reported some lesbian women believed not pursuing breast reconstruction was less problematic for lesbians than for heterosexual women because they thought female partners did not value breasts as much as male partners did; however, at least one SMW participant reported she did not find that to be true in sexual encounters after her surgery.

Results suggest that breast cancer can have an effect on sexual aspect of relationships. In a survey of SMW and transgender breast cancer survivors (Brown and McElroy, 2018), participants reported in open-ended responses that treatment reduced interest in sex and sexual frequency. Another study found that SMW breast cancer survivors reported significantly lower levels of sexual concerns, physical appearance concerns, and sexual disruption than did heterosexual female survivors; there were no significant differences between the groups in patient reports of partners being bothered by the surgical scar associated with cancer treatment (Arena et al., 2007).

Other studies examined relationship-level outcomes—including relationship satisfaction, dyadic cohesion, and dyadic correlation in stress—and compared SMW to other groups. Findings were mixed, although in many cases they indicated that relationship-level outcomes were similar for SMW with cancer compared to heterosexual women with cancer. Arena et al. (2007) found no significant differences between lesbian and heterosexual women with cancer in relationship satisfaction, conflict, partner expressions of affection, and partner reactions to threat to life. Boehmer et al. (2016) compared SMW and heterosexual women with cancer and found no significant differences in self-reported dyadic cohesion and effect of cancer on the patient-caregiver relationship. Comparisons between caregivers also revealed no significant differences between the two caregiver groups in dyadic cohesion or effect of cancer on the relationship; the majority of patients and caregivers reported that cancer brought them closer (Boehmer et al., 2016). Bivariate analyses in a study of SMW with breast cancer and SMW without breast cancer (Boehmer et al., 2012) demonstrated no significant differences in self-reported dyadic cohesion or dyadic satisfaction, and, in multivariate models, dyadic cohesion was a predictor of female sexual functioning. In further analyses using the same dataset (Boehmer et al., 2018), survivor and caregiver stress was significantly correlated overall; in stratified analyses, a significant positive correlation in stress was observed between SMW and their caregivers but not between heterosexual women and their caregivers. In dyads with SMW, caregiver stress was significantly associated with patient stress, a pattern not present in dyads with heterosexual women patients.

Effect of Cancer on Partners and Informal Caregivers

The included studies showed a range of effects of cancer on partners/caregivers including feelings of distress, burden of caregiving (White and Boehmer, 2012), and isolation (Bristowe et al., 2018). Sinding et al. noted that the physical similarity among female partners and the cancer patients was seen as potentially distressing because it could make partners acutely aware of the physical changes that patients undergo during treatment (Sinding et al., 2007). Boehmer et al. (2005) found that support people (79% partners, but also friends and other family) for SMW with breast cancer had significantly lower perceived support than the patients themselves. A comparison of caregivers for SMW and heterosexual women found that caregiver stress did not differ between the two groups (Boehmer et al., 2018). However, caregivers for SMW reported higher significant-other and friend support than did caregivers for heterosexual women (Boehmer et al., 2016).

Several studies reported that partners/caregivers for SMW with cancer may be affected by discrimination and lack of sexual minority-friendly services. Patients reported concern about finding SMW-friendly support groups for partners (Bristowe et al., 2018, Paul et al., 2014). Brown and McElroy (2018) found a sizable proportion of respondents (40%) reported that their sexual or gender identity mattered in terms of obtaining support for them and their partner. At the same time, the majority of lesbian women in partnered relationships interviewed by Matthews et al. (2002) were satisfied with the emotional support their partner received from medical providers, and all were satisfied with the inclusion of their partner in medical decisions and the respect their partners received from medical staff. The degree to which SMW with cancer are “out” may also affect their partners/caregivers. Boehmer et al. (Boehmer et al., 2005) found that when SMW with breast cancer demonstrated lower levels of disclosure about their sexual orientation, their support people partner/caregiver reported more distress (Boehmer et al., 2005).

Interventions

Only one article (Fobair et al., 2002) involved an intervention, a 12-week intervention delivering supportive/expressive group therapy to lesbian women with breast cancer. The intervention was designed in part to address social relationships, but it did not target partners/caregivers, and relationship-level outcomes were not reported.

Rigor and Potential for Bias

The included articles all described eligibility criteria adequately and discussed at least some study limitations (Table 3). Most articles included information about study participants; the most commonly omitted information was some characteristic related to SES (such as income or educational attainment), which was not included in six of the studies. All articles provided at least minimal description of analytic methods, but four quantitative studies provided no rationale for the analytic methods that were chosen. Source of funding, which was disclosed for all but one study, came primarily from government agencies and private foundations.

Table 3.

Rigor, potential for bias, and funding sources for included studies (N = 18)

| Citation | Describes eligibility criteria, sources, methods, rationale of participant selection |

Describes characteristics of study participants |

Describes and provides a rationale for quantitative or qualitative analytic methods |

Discusses study limitations, including sources of potential bias or imprecision |

Funding Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Arena et al. (2007) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | National Cancer Institute |

| 2. Boehmer et al. (2005) | ✓ | ✓ | Described, but no rationale | ✓ | American Cancer Society; Massachusetts Department of Public Health Cancer Research Program |

| 3. Boehmer et al. (2013a) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | American Cancer Society |

| 4. Boehmer et al. (2013b) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | American Cancer Society |

| 5. Boehmer et al. (2007) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Massachusetts Department of Public Health Cancer Research Program; American Cancer Society; Department of Veterans Affairs |

| 6. Boehmer et al. (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | American Cancer Society |

| 7. Boehmer et al. (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | Described, but no rationale | ✓ | Susan G. Komen for the Cure Foundation |

| 8. Boehmer et al. (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | American Cancer Society |

| 9. Bristowe et al. (2018) | ✓ | No measure of socioeconomic status | ✓ | ✓ | Marie Curie Research Grants Scheme |

| 10. Brown and McElroy (2018) | ✓ | No measure of socioeconomic status | ✓ | ✓ | Aging Studies Institute and Falk College Research Center at Syracuse University |

| 11. Fish et al. (2019) | ✓ | No measure of socioeconomic status | ✓ | ✓ | Macmillan Cancer Support, School of Nursing at De Montfort University |

| 12. Fobair et al. (2001) | ✓ | Sample characteristics not described* | Described, but no rationale | ✓ | National Cancer Institute |

| 13. Fobair et al. (2002) | ✓ | ✓ | Described, but no rationale | ✓ | National Institute of Mental Health |

| 14. Kamen et al. (2015) | ✓ | No information about age or measure of socioeconomic status | ✓ | ✓ | DAISY Foundation J. Patrick Barnes Grants for Nursing; National Cancer Institute |

| 15. Matthews et al. (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation |

| 16. Paul et al. (2014) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | None noted |

| 17. Sinding et al. (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation, Ontario Chapter |

| 18. White and Boehmer (2012) | ✓ | No measure of socioeconomic status | ✓ | ✓ | American Cancer Society |

The text of this article refers to demographic information included in Table 1, but tables seem to have been inadvertently omitted from the text. Attempts to obtain the tables from the first author and the publisher were unsuccessful.

Several factors led to concerns about the risk of bias across studies regarding our outcomes of interest, particularly related to generalizability of findings. First, all included studies used convenience samples. Second, as noted above, those studies reporting socioeconomic characteristics generally included participants with relatively high SES, and most participants were white/Caucasian. Third, nearly all studies took place in the United States. Taken together, these characteristics call into question whether results would hold in the general population of SMW, either in the United States or elsewhere.

The analytic methods used may also have led to bias. It is possible, for example, that the face-to-face interviews and focus groups in many of the qualitative studies could have led to social desirability bias. The small sample sizes in many of the quantitative studies, as well as the use of multiple statistical tests and lack of preregistration of hypotheses, may have affected precision of findings and biased studies toward positive results (Nosek et al., 2018, Simmons et al., 2011). On the other hand, the authors deemed it unlikely that the sources of funding (primarily government agencies and private foundations) exerted undue influence over study findings or otherwise introduced systematic bias across studies.

Discussion

The studies we reviewed provide a first step toward understanding the social contexts of SMW with cancer and the role played by intimate partners and informal caregivers. The included studies show that partners and informal caregivers often provide crucial social support for SMW with cancer. Partners and other caregivers often help patients manage health and distress, provide tangible and decision-making support, and help survivors look to the future. Some studies suggested that SMW may be advantaged in terms of receiving support from female partners, but others showed comparable relationship-level outcomes between SMW and heterosexual women. Partners/caregivers may face stressors themselves, including isolation, discrimination, and a lack of inclusive services. Our results also point to a lack of interventions that target partners/caregivers of SMW with cancer or the patient-caregiver dyad.

Overall, these findings offer a strengths-based perspective on SMW’s experiences in the context of cancer. Many SMW women felt supported by their partners, which is consistent with the literature showing intimate partnerships provide important support for SMW in the general population (Riggle et al., 2008). Results are also consistent with findings among heterosexual couples that a diagnosis of cancer may lead to increased closeness among many women and their partners (Dorval et al., 2005, Drabe et al., 2013). At the same time, there are suggestions that patients’ and partners’ status as SMW may affect services or support available to them and that degree of “outness” (and discrepancies in outness) could affect quality of life outcomes and relationships between patients and their partners/caregivers.

Although all the included studies answered at least some aspects of our research questions, the heterogeneity of outcome variables (in quantitative studies) and research questions (in qualitative studies) makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions across studies. In quantitative studies, a range of measures were used to assess relationship quality and quality of life outcomes for both cancer patients and partners/caregivers, which makes comparison across studies challenging. In qualitative studies, interviews covered a wide range of domains. Although comparing SMW with cancer to other groups (e.g. heterosexual women with cancer or SMW without cancer) was not the focus of our research questions, several included studies were designed to test such comparisons; in addition, some participants in qualitative studies drew explicit comparisons between their own experiences and the perceived experiences of people in other groups. In other cases, however, studies were primarily descriptive and did not include a comparison group. As research about SMW with cancer advances, it will be important for researchers to converge on a key set of research questions and appropriate measures, especially measures that have been shown to be reliable and valid in populations of SMW.

It is important to note that many of the samples from these articles overlapped. Eight of the 18 study teams included one researcher who has conducted groundbreaking work in the area of SMW and cancer. Although it is certainly practical to re-contact respondents from hard-to-reach populations who have shown a willingness to participate in research, the overlap in these studies limits the conclusions that can be drawn about SMW in general. In future work, it will be important to recruit new samples and expand the number of research teams addressing these questions.

Although there was heterogeneity in terms of study domains and measures, many of the included studies also shared certain characteristics. The majority of studies included patients with non-metastatic breast cancer and were conducted in U.S. settings. Most studies also involved samples that were predominantly white/Caucasian and well-educated. It is unknown whether these findings would transfer to different contexts and populations. More work is needed to recruit and assess patients with cancers other than breast cancer and patients with metastatic disease; patients who are racially, ethnically, and economically diverse; and patients outside of the U.S.

The included studies demonstrated methodological issues that may be cause for concern. Relatively few studies described clear a priori hypotheses or research questions that were explicitly grounded in theory, which means the work should be considered primarily exploratory (Nosek et al., 2018). Several quantitative studies involved small samples, did not adjust for multiple statistical tests (Veazie, 2006), or used the same population to examine several outcomes of interest. All but one of the studies were cross-sectional, which limits the inferences that can be drawn. Qualitative studies included participants’ interpretations of the effect of cancer on their lives, but determining the effects of cancer versus other life factors would necessitate different study designs. Future research should assess additional elements of distress including finances, employment, cancer-related physical symptoms, childcare, and other co-morbidities for both patient and caregiver in order to provide a more nuanced understanding of the social context of cancer care. Longitudinal research will be necessary to examine the evolution of relationships, support, elements of distress, and patterns of mutual influence over time in response to cancer. Such research could examine, for example, whether relationship history and dynamics prior to cancer diagnosis predicts type and degree of support after diagnosis, or whether factors such as degree of “outness” present prior to diagnosis might influence the treatment process (i.e., having to “come out” to the medical team and employers so the partner can be present for treatment decisions and procedures).

Moving forward, it will also be important to ground future work in theory and conduct dyadic analyses. Only four of the included studies involved dyadic analyses, but in future research it will be important to analyze outcomes for both members of a dyad. Elements from Minority Stress Theory (e.g., analyzing distal and proximal stressors experienced due to sexual orientation [Meyer, 2003]) could be integrated into existing dyadic theories of couples and chronic disease, such as the Relationship Intimacy Model of Couple Adaptation to Cancer (Manne and Badr, 2008) or the Developmental-Contextual Model of Couples Coping with Chronic Illness (Berg and Upchurch, 2007). Doing so would leverage the strengths of a dyadic perspective while also incorporating the particular stressors faced by SMW.

Our systematic review has several strengths. The review team had broad, multidisciplinary expertise and included a research librarian with extensive experience searching databases, and we conducted independent/duplicate coding and data extraction. Our search was expanded and updated in March 2020.

There are also limitations. Although we designed and conducted our search carefully, it is possible that we may have missed research that addressed our study questions due to reporting or publication bias; the decision to limit our search to articles published in English may have led us to miss international work published in other languages. Many included studies provided only partial information about our research questions. If studies included both men and women with cancer, or both sexual minority and non-sexual-minority women, our inclusion criteria called for data from SMW to be analyzed separately. In some cases, that led us to rely on descriptive or bivariate analyses rather than multivariable models. Although our research questions were framed as investigating the “effects” of cancer, the cross-sectional nature of most included studies rendered definitive determinations of causality impossible. In addition, the rigor of our review would have been enhanced by preregistering our search protocol (e.g. on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews). Finally, the study team created our own measures of bias adapted from prior work (Table 3), but two of these items showed little variability and were thus not useful in differentiating studies from one another. The item assessing methods was rated as “met” if the authors described their methods and provided a rationale, but it did not include our study team’s evaluation of the appropriateness of those methods. If used in future work, these items should be modified to ensure they are useful for assessing a heterogeneous group of studies.

Despite these limitations, this systematic review provides an overview of the current state of the science about the support SMW with cancer receive from partners/caregivers, the effect of cancer on partners/caregivers, and the effect of cancer on the relationships of SMW and partners/caregivers. It is clear that partners/caregivers provide important support to SMW with cancer and also that the influence of cancer on the relationships of SMW is mixed. SMW participants noted their partners/caregivers were at risk for distress, discrimination, discomfort about disclosing sexual orientation, and lack of accessible services. The directions for future research identified here will help chart an evolving research agenda that can inform interventions and clinical practice and ensure that the needs of SMW with cancer and their partners/caregivers are met.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Tess Thompson, Washington University in St. Louis.

Katie Heiden-Rootes, Saint Louis University.

Miriam Joseph, Saint Louis University.

L. Anne Gilmore, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

LaShaune Johnson, Creigton University.

Christine M. Proulx, University of Missouri.

Emily L. Albright, University of Missouri.

Maria Brown, Syracuse University.

Jane A. McElroy, University of Missouri.

References

*Article included in the qualitative synthesis.

- Antonovsky A 1996. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promotion International, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- *.Arena PL, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weiss S, Ironson G & Durán RE 2007. Psychosocial responses to treatment for breast cancer among lesbian and heterosexual women. Women and Health 44, 81–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora NK, Finney Rutten LJ, Gustafson DH, Moser R & Hawkins RP 2007. Perceived helpfulness and impact of social support provided by family, friends, and health care providers to women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 16, 474–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF & Mohr JJ 2007. Adaptation to sexual orientation stigma: A comparison of bisexual and lesbian/gay adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 306. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF & Szymanski DM 2005. Relationship quality and domestic violence in women’s same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 258–269. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi AR, Clark MA, Winter MR, Ozonoff A & Boehmer U 2018. Resilience Among Breast Cancer Survivors of Different Sexual Orientations. LGBT Health, 5, 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA & Upchurch R 2007. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 920–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF & Syme SL 1979. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 109, 186–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich JR, Hanmer J, Yu L, Matthews DD & Kavalieratos D 2016. Health care use, health behaviors, and medical conditions among individuals in same-sex and opposite-sex partnerships: A cross-sectional observational analysis of the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS), 2003–2011. Medical Care 54, 547–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer U, Clark M, Glickman M, Timm A, Sullivan M, Bradford J & Bowen DJ 2010. Using cancer registry data for recruitment of sexual minority women: Successes and limitations. Journal of Women’s Health 19, 1289–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer U, Clark MA, Timm A, Glickman M & Sullivan M 2011. Comparing sexual minority cancer survivors recruited through a cancer registry to convenience methods of recruitment. Women’s Health Issues, 21, 345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boehmer U, Freund KM & Linde R 2005. Support providers of sexual minority women with breast cancer: Who they are and how they impact the breast cancer experience. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 59, 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M & Clark MA 2013a. Breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations: Which factors explain survivors’ quality of life and adjustment? Annals of Oncology, 24, 1622–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M & Clark MA 2013b. Lesbian and bisexual women’s adjustment after a breast cancer diagnosis. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 19, 280–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boehmer U, Linde R & Freund KM 2007. Breast reconstruction following mastectomy for breast cancer: The decisions of sexual minority women. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, 119, 464–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boehmer U, Stokes JE, Bazzi AR, Winter M & Clark MA 2018. Dyadic stress of breast cancer survivors and their caregivers: Are there differences by sexual orientation? Psycho-Oncology, 27, 2389–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boehmer U, Timm A, Ozonoff A & Potter J 2012. Explanatory factors of sexual function in sexual minority women breast cancer survivors. Annals of Oncology 23, 2873–2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boehmer U, Tripodis Y, Bazzi AR, Winter M & Clark MA 2016. Fear of cancer recurrence in survivor and caregiver dyads: differences by sexual orientation and how dyad members influence each other. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 10, 802–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bristowe K, Hodson M, Wee B, Almack K, Johnson K, Daveson BA, Koffman J, McEnhill L & Harding R 2018. Recommendations to reduce inequalities for LGBT people facing advanced illness: ACCESSCare national qualitative interview study. Palliative Medicine 32, 23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown JP & Tracy JK 2008. Lesbians and cancer: An overlooked health disparity. Cancer Causes & Control, 19, 1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MT & McElroy JA 2018. Unmet support needs of sexual and gender minority breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26, 1189–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Pozo-Kaderman C, Price AA, Noriega V, Harris SD, Derhagopian RP, Robinson DS & Moffatt FL 1998. Concern about aspects of body image and adjustment to early stage breast cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine, 60, 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM, Bowen D, Gage S, Bybee D, Roberts SJ, Goldstein RS, Robison A, Rankow EJ & White J 2001. Cancer-related risk indicators and preventive screening behaviors among lesbians and bisexual women. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 591–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S & Williamson G 1988. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S & Oskamp S (eds.) The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR 1975. The Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual, Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele A, Cox N, Van den Berghe W & Vincke J 2011. Families of choice? Exploring the supportive networks of lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41, 312–331. [Google Scholar]

- Dorros SM, Card NA, Segrin C & Badger TA 2010. Interdependence in women with breast cancer and their partners: An interindividual model of distress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 121–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorval M, Guay S, Mondor M, Masse B, Falardeau M, Robidoux A, Deschênes L & Maunsell E 2005. Couples who get closer after breast cancer: frequency and predictors in a prospective investigation. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 3588–3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabe N, Wittmann L, Zwahlen D, Büchi S & Jenewein J 2013. Changes in close relationships between cancer patients and their partners. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 1344–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Fish J, Williamson I & Brown J 2019. Disclosure in lesbian, gay and bisexual cancer care: Towards a salutogenic healthcare environment. BMC Cancer, 19, 678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]