Abstract

Background

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease with an estimated 150 000 patients in Germany alone.

Methods

This review is based on publications about current diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for ulcerative colitis that were retrieved by a selective search in PubMed, and on current guidelines.

Results

The primary goal of treatment is endoscopically confirmed healing of the mucosa. Mesalamine, in various forms of administration, remains the standard treatment for uncomplicated ulcerative colitis. Its superiority over placebo has been confirmed in meta-analyses of randomized, controlled trials. Glucocorticoids are highly effective in the acute treatment of ulcerative colitis, but they should only be used over the short term, because of their marked side effects. Further drugs are available to treat patients with a more complicated disease course of ulcerative colitis, including azathioprine, biological agents, JAK inhibitors (among them TNF antibodies, biosimilars, ustekinumab, vedolizumab, and tofacitinib), and calcineurin inhibitors. Proctocolectomy should be considered in refractory cases, or in the presence of high-grade epithelial dysplasia. Ulcerative colitis beginning in childhood or adolescence is often characterized by rapid progression and frequent comorbidities that make its treatment a special challenge.

Conclusion

A wide variety of drugs are now available for the treatment of ulcerative colitis, enabling the individualized choice of the best treatment for each patient. Regular surveillance colonoscopies to rule out colon carcinoma should be scheduled at intervals that depend on risk stratification.

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease of multifactorial origin whose etiology and pathogenesis are not yet fully understood. Its incidence has risen around the world in recent decades. In Germany, at least 150 000 people currently suffer from ulcerative colitis. A brief overview of the etiology, pathogenesis, and epidemiology of the disease, and of references for further information, can be found in the eMethods section of this review.

Method

Definition.

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease of multifactorial origin whose etiology and pathogenesis are not yet fully understood.

This CME review is based on relevant publications in either English or German that appeared up to and including March 2020 and were retrieved by a comprehensive search in PubMed, as well as on the recently published German guideline for ulcerative colitis (1), the ECCO guideline (2), and the NICE guideline (3).

Learning goals

Prevalence.

In Germany, at least 150 000 people currently suffer from ulcerative colitis.

Reading this article should enable the reader to:

Know the diagnostic principles of the acute treatment and monitoring of ulcerative colitis,

be acquainted with the guiding principles of treatment, and

be aware of the special features of the treatment of ulcerative colitis in childhood and adolescence.

Diagnostic evaluation

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis cannot be established definitively by any single diagnostic study. Rather, it is made on the basis of an overall interpretation of the clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, and endoscopic, histological, and radiological findings (1). An infectious cause must be ruled out at the time of initial diagnosis, and later on whenever an acute episode arises. The classic microbial pathogens should be considered, and in particular Clostridioides difficile (antigen and toxin titers should be measured, and, whenever possible, the organism should be demonstrated by culture or PCR). In treatment-resistant cases, a reactivated cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection should be demonstrated or ruled out, as recommended in a current guideline (1). Laboratory testing should include the measurement of inflammatory parameters in the blood (leukocyte count and differential, platelet count, CRP) and stool (calprotectin or lactoferrin concentration). The main differential diagnosis is Crohn’s disease, followed by rarer types of colitis, e.g., colitis induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and ischemic, lymphogenic, collagenous, or eosinophilic colitis. Rarely, in cases of treatment-resistant proctitis, a sexually transmitted disease, radiation-induced proctitis, or malignant infiltration of the colorectum must be considered. Proctological diseases should be considered in cases of purely proctitic symptoms or isolated hematochezia (1).

History and physical examination

The most prominent manifestation is bloody diarrhea (>90%), often combined with cramping pain (tenesmus, >70%) in the left lower quadrant, or along the entire length of the colon in patients with pancolitis. Fecal urgency is also common (>70%) (e1). Depending on the severity and extent of disease, the physical examination may be unremarkable. In patients with severe colitis, abdominal tenderness—along with fever and peritoneal signs—is an alarm signal for a poorer prognosis, with the potential development of fulminant colitis, up to and including a toxic megacolon.

Laboratory tests

Diagnostic evaluation.

In acute steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis, a Clostridioides difficile superinfection or a cytomegalovirus reactivation should be considered in the differential diagnosis and ruled out by appropriate testing.

The classic parameters of inflammation (leukocyte count and CRP) are generally not elevated, unless the inflammatory activity of ulcerative colitis is very intense. It follows that elevated inflammatory parameters imply a severe disease course. In mild colitis or isolated proctitis, the fecal inflammatory parameters, such as calprotectin, are much more sensitive. These are, therefore, suitable for the follow-up evaluation of all patterns of involvement of the disease. A fecal calprotectin value below 150–200 µg per gram of stool is considered a reliable marker of remission (1). Iron-deficiency anemia is the most common extraintestinal manifestation of chronic inflammatory bowel disease; thus, screening for iron deficiency (complete blood count, ferritin, transferrin saturation) should be carried out approximately once per year, even in patients who are clinically in remission (1, 4). Because an accompanying primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), if present, would have major implications for the treatment and prognosis of ulcerative colitis, the bilirubin concentration and cholestasis parameters should be checked approximately once per year as well (5).

Endoscopy

Ulcerative colitis is visualized endoscopically as an inflammatory process that spreads continuously from the rectum in the oral direction. It can be classified according to the pattern of involvement, as follows:

proctitis, i.e., inflammation confined to the rectum (e1),

left-sided colitis (e2), and

colitis that has spread past the splenic flexure (e3).

The spectrum of endoscopic findings ranges from low activity, with a rough, granular mucosa, reduced vascular markings, and no more than mild erythema, all the way to severe activity with (sometimes confluent) ulcers and spontaneous, mainly petechial hemorrhages (e2, 6). The degree of inflammatory activity can be classified by its endoscopic appearance, e.g., with the Mayo score or the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) score (1, 6). The transition from normal to inflamed mucosa is typically sharply delineated, and the inflammation typically becomes more severe proceeding distally. The rectum may be spared in patients who have both sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis, as well as in children and adolescents with ulcerative colitis. A lesser degree of inflammation may also be seen distally as the result of local treatment with suppositories, enemas, or foam. In left-sided colitis, there may be an isolated focus of inflammatory activity in the cecum, a so-called cecal patch.

Iron-deficiency anemia.

Iron-deficiency anemia is the most common extraintestinal manifestation of chronic inflammatory bowel disease; thus, screening for iron deficiency should be carried out approximately once per year, even in patients who are clinically in remission.

Whenever any treatment is initiated or switched to another type of treatment, and particularly when treatment with any biological agent is begun, the response should be checked by endoscopy in three to six months (5). The goal of treatment is endoscopically documented healing of the mucosa, even if this cannot be achieved in all patients. If endoscopy is unavailable, the treatment response should be judged with the aid of objective surrogate parameters, such as the lowering or normalization of fecal calprotectin, or the normalization of the ultrasonographically measured thickness of the bowel wall (5, 7). Patients whose disease has spread beyond the rectum should undergo endoscopy regularly, starting six to eight years after their diagnosis, at intervals that depend on risk stratification (box). Colon carcinoma can arise as a sequela of longstanding ulcerative colitis: according to recent studies, some 7% of patients with ulcerative colitis have colon carcinoma by 30 years after the onset of the disease (8, e3). The risk of colon cancer has gone down in recent years because of meticulous surveillance programs and better control of inflammation (e4). Surveillance colonoscopy should be performed either as chromoendoscopy, or else as high-resolution white-light endoscopy, with targeted biopsies in either case (1). Whenever possible, it should be carried out in remission or in a phase of lesser inflammatory activity, because more marked inflammation can also reflect the inflammatory process that accompanies low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (5). Patients who simultaneously have primary sclerosing cholangitis are at a markedly higher risk of hepatobiliary carcinoma, and their risk of early-onset colon carcinoma is elevated fivefold. They must, therefore, undergo intensive surveillance, with annual colonoscopy starting from the time of diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis (1).

BOX. Follow-up intervals for surveillance colonoscopy from the 8th year of illness onward, based on risk stratification in patients with ulcerative colitis*.

-

yearly (high risk)

extensive colitis with high-grade inflammation

first-degree relatives under age 50 with colorectal carcinoma

intraepithelial neoplasia in the past five years

primary sclerosing cholangitis (yearly from the time of diagnosis) (chromoendoscopy + random biopsies)

stenosis

-

every 2–3 years (intermediate risk)

mildly to moderately active colitis

first-degree relatives over age 50 with colorectal carcinoma

many pseudopolyps

-

every 4 years (low risk)

in the absence of all of the above criteria

* If multiple criteria are met, the highest corresponding risk category is assigned.

Imaging techniques

In ulcerative colitis with a low degree of activity, ultrasonography of the colon generally yields unremarkable findings; the rectum can only be visualized to a limited extent. In an acute episode of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, moderate wall thickening (>3 mm) is found, along with submucosal edema, maintenance of the laminar structure of the bowel wall, and hyperperfusion. Intestinal ultrasonography is increasingly used for follow-up after an acute episode, as successful treatment will be reflected by the diminution or normalization of wall thickness within two weeks (7). Supplementary tomographic methods such as magnetic resonance imaging are sometimes used as a differential diagnostic aid to distinguish ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s disease (e5).

Treatment

The conventional treatment of uncomplicated ulcerative colitis

Surveillance colonoscopy.

Surveillance colonoscopy should be performed regularly, starting six to eight years after the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis, at intervals that depend on risk stratification

The standard treatment of uncomplicated, mild to moderate colitis.

Mesalamine is the standard drug for the treatment of uncomplicated, mild to moderate ulcerative colitis.

The choice of treatment for ulcerative colitis is generally based on the pattern of involvement of the disease and the degree of its clinical activity (figure 1). Mesalamine, also known as 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), is a pillar of pharmacotherapy for ulcerative colitis. It can be given either per os or per rectum in the form of a suppository, foam, or enema. Meta-analyses of randomized, controlled trials have shown its superiority over both placebo and rectal steroids in the treatment of ulcerative colitis, not only for inducing remission, but also as maintenance therapy (9, 10). The rectal administration of mesalamine yields a concentration of the active substance that is up to 100 times higher at the site of inflammation and is thus preferred over oral administration for inducing remission. In all patterns of disease involvement, combined rectal and oral administration is more effective than oral administration alone, both for remission induction and for maintenance therapy. For the treatment of proctitis, topical mesalamine is more effective than topical steroids, and is thus the agent of choice (e6). If mesalamine alone fails to induce a remission of proctitis, it should be combined with either topically or systemically administered steroids. The first-line treatment of mild to moderate left-sided ulcerative colitis should consist of combined oral and rectal mesalamine (11). Left-sided ulcerative colitis with mild to moderate inflammatory activity that does not respond to mesalamine can be treated with oral budesonide-MMX (e7, e8).

Figure 1.

The outpatient treatment of uncomplicated ulcerative colitis.

BW, body weight; p.o., per os; p.r., per rectum

Patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis and extensive involvement should be treated initially with an oral mesalamine-releasing preparation at a dose of at least 3 g/day, combined with mesalamine enemas or foam (12).

Systemic glucocorticoids.

Systemic glucocorticoids are used if a remission cannot otherwise be induced, as well as for the primary treatment of patients with acute, severe ulcerative colitis.

Remission-sustaining therapy.

Remission-sustaining treatment should be continued for at least two years. Treatment with E. coli Nissle is an alternative for patients who cannot tolerate mesalamine.

Systemic glucocorticoids are used if a remission cannot be induced by the above means; they are also used for the primary treatment of patients with acute, severe ulcerative colitis. In the latter situation, glucocorticoids are more effective when given intravenously, rather than orally. In view of their well-known, numerous adverse effects, steroids should only be given over the short term (a few weeks at most), and not as maintenance therapy.

Mesalamine is the standard option for maintenance therapy for the purpose of sustaining a remission in uncomplicated ulcerative colitis (1, 3). Aside from its remission-sustaining effect, it also has a preventive effect against carcinoma, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.51 (95% confidence interval [0.37; 0.69]) (e9). To sustain a remission, mesalamine can be given either topically for distal colitis, or orally for extensive colitis (9). Remission-sustaining treatment should be continued for at least two years (1). Treatment with E. coli Nissle is an alternative for patients who cannot tolerate mesalamine. The non-inferiority of E. coli Nissle compared to mesalamine has been shown in a meta-analysis of three controlled trials (13); nonetheless, because far more data are available for mesalamine than for E. coli Nissle, mesalamine should be used preferentially. More than half of all patients suffer a recurrence after mesalamine is discontinued (14, 15).

Most patients with ulcerative colitis can be brought into remission by conventional treatment with mesalamine and/or glucocorticoids, and then kept in remission by maintenance treatment with mesalamine.

Treatment options in complicated courses of disease

Complicated course.

A complicated course of ulcerative colitis is one in which the disease does not respond to conventional treatment.

Steroid-dependent course.

A steroid-dependent course is one in which glucocorticoids given to induce remission cannot be lowered to less than 10 mg/day within three months without a recurrence, or else an early recurrence arises within a short time.

A complicated course of ulcerative colitis is one in which the disease does not respond to conventional treatment. Approximately half of all patients with ulcerative colitis have a chronic-persistent or chronic-recurrent course (16). Current guidelines generally draw a therapeutically relevant distinction between steroid-dependent and steroid-resistant courses (1, 2).

Steroid-dependent course

A steroid-dependent course is one in which glucocorticoids given to induce remission cannot be lowered to less than 10 mg/day within three months without a recurrence, or else an early recurrence arises within a short time (17). Thiopurines can be used to treat steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Treatment with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine generally does not yield a clinical effect until three months after treatment is begun, so bridging with glucocorticoids may be necessary. Drugs other than thiopurines that can be used in a steroid-dependent course include the TNF antibodies infliximab, adalimumab (and the respective biosimilars), and golimumab, the anti-integrin antibody vedolizumab, and the recently introduced agents tofacitinib (18) and ustekinumab (19). Biosimilars of infliximab and adalimumab are now available and are increasingly being used primarily. Multiple switching among various biosimilars of a single substance should be avoided as much as possible, as there is currently no evidence to support this practice.

In the absence of direct comparative trials, no clear recommendation can be given about the order of priority of the various biological agents now available (figure 2). The data given in the Table regarding remission rates and number needed to treat (NNT) imply differences in efficacy. Different types of TNF antibody have never been tested against each other in direct comparative trials, but, in two network meta-analyses, infliximab was found to be the most effective one, at least in patients with biological-agent-naive ulcerative colitis, followed by golimumab and adalimumab (20, 21). These differences should be borne in mind in the choice of treatment.

Figure 2.

The treatment of steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis

In a recent randomized comparative trial of two biological agents, which was the first of its kind to be performed, 31.3% of the patients with ulcerative colitis achieved a remission with vedolizumab, compared to 22.5% with adalimumab (p = 0.0061) (primary endpoint in Week 52) (22). The advantage of vedolizumab over adalimumab with respect to treatment response was already evident 6–14 weeks after the start of treatment.

Ustekinumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against the P40 subunit of interleukin-12 and interleukin-23. Its efficacy in inducing and sustaining remissions of ulcerative colitis has been demonstrated in randomized trials (19). The advantage of ustekinumab may lie not only in its rapid induction of remission, but also in its relatively well-preserved efficacy over time (as far as is currently known) and its favorable side-effect profile.

Tofacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that has been used for a number of years to treat rheumatoid arthritis. Its efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis has now been documented in three randomized, placebo-controlled trials (18, 23). The side effects of this drug, especially thromboembolic complications, limit its use in patients with certain risk profiles (table).

Table. The pharmacotherapy of ulcerative colitis.

| Drug | NNT to induce remission | NNT to sustainremission | Remission rateat Week 8 | Remission rateat 12 months | Side effects (selected) | Approved for: | Reference |

| Disease activity: mild to moderate | |||||||

| Aminosalicylates p.o. | 9 | 6 | 29% / P*1 17% | 59% / P*1 42% | interstitial nephritis, pancreatitis | children + adults | (9, 10) |

| Aminosalicylates p.r. | 4 | 75% / P*1 24% | 62% / P*1 30% | interstitial nephritis, pancreatitis | children + adults | (e37, 14) | |

| Budesonide p.r. | 6 | - | 41.2% / P*1 24% | - | adults | (e37) | |

| Budesonide MMX | 9 | - | 17.7% / P*1 6.2% | - | adults | (35) | |

| Disease activity: moderate to severe | |||||||

| Azathioprine | - | 5 | – | 56% / P*1 35% | leukopenia, hepatopathy, pancreatitis, tendency to infection, mildly elevated rate of malignancy* 2 (skin cancer other than melanoma, lymphoma, cancer of the urogenital tract) | children + adults | (e38) |

| Infliximab (and biosimilars) | 5 | 6 | 38.8% / P*1 14.9% | 34.7% / P*1 16.5% | tendency to infection, TB reactivation, rash, joint pain, mildly elevated risk of melanoma* 2 | children + adults | (36) |

| Adalimumab (and biosimilars) | 14 | 12 | 16.5% / P*1 9.3% | 17.3% / P*1 8.5% | tendency to infection, TB reactivation, rash, joint pain, mildly elevated risk of melanoma* 2 | adults | (37) |

| Golimumab | 9 | 9 (100 mg), 14 (50 mg) | 17.8% / P*1 6.4% | 23.2% (50 mg);27.8% (100 mg) / P* 1 15.6% | tendency to infection, TB reactivation, skin changes, joint pain, mildly elevated risk of melanoma* 2 | adults | (38, 39) |

| Vedolizumab | 9 | 4 (8-weekly) und 4 (4-weekly) | 16.9% / P*1 5.4% | 41.8% (8-weekly), 44.8% (4-weekly) / P* 1 15.9% | respiratory infections | adults | (40) |

| Ustekinumab | 10 | 7 (12-weekly), 6 (8-weekly) | 15.6 % / P*1 5.3% | 38.4% (12-weekly), 43.8% (8-weekly) / P* 1 24% (week 44) | adults | (19) | |

| Tofacitinib | 9 | 5 (5 mg maintenance dose) 4 (10 mg maintenance dose) | OCTAVE trials1+2: 17.6% / P*1 5.9% | 34,3 %(5 mg), 40.6% (10 mg) / P*1 11.1% | tendency to infection, at 10 mg dose VZV, risk of thrombosis and embolism, caution: for patients over age 65 only if there is no other therapeutic option | adults | (18) |

| Cyclosporine | 2 | – | 82% / P*1 0% (response) | - | leukopenia, liver and kidney dysfunction, hirsutism, headache | adults | (e39) |

*1 Placebo

*2 The indicated increase in the malignancy rate is for the drug in question when given to treat chronic inflammatory bowel disease.

Treatment-resistant proctitis can be treated with either beclomethasone or tacrolimus suppositories (e10, e11).

The relevant side effects of the various immune suppressants, biological agents, and JAK inhibitors are listed in the Table. The reader is referred to the pertinent guidelines for further information on the important topics of ulcerative colitis and pregnancy (24), the risk of malignancy associated with various drugs (25), and the vaccinations that are recommended for immune-suppressed patients (26, e12).

Steroid-refractory / fulminant course

The treatment of fulminant ulcerative colitis.

Fulminant ulcerative colitis should be treated on an inpatient basis by a multidisciplinary team.

Treatment-refractory course in adults.

Proctocolectomy should be considered early as an important treatment option for adults with ulcerative colitis who have a treatment-resistant course or a high risk of malignancy.

There is no standard definition of steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. In everyday clinical practice, the term generally refers to a disease course in which no remission can be achieved with a standard dose of prednisolone (1 mg/kg body weight) within a clinically acceptable time frame. Various drugs that are used to treat steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis can also be used in cases that are steroid-refractory (figure 2). As the goal is to induce a remission rapidly, drugs whose effect sets in only after a delay, such as azathioprine, cannot be used. No clear recommendation can be given about the order of priority of the different biological agents in view of the lack of relevant comparative trials. As in steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis, the determinative factors for personalized decision-making include the rapidity of onset of the therapeutic effect, the personal experience of the treating physician, the age of the patient, and the potential side effects in the individual clinical context. In a situation of high disease activity, a rapidly effective substance such as TNF antibodies, ustekinumab, or tofacitinib is generally preferred. As a rule, whenever there is a switch of treatment involving a biological agent, it is time for a thorough discussion with the patient about the further therapeutic option of proctocolectomy.

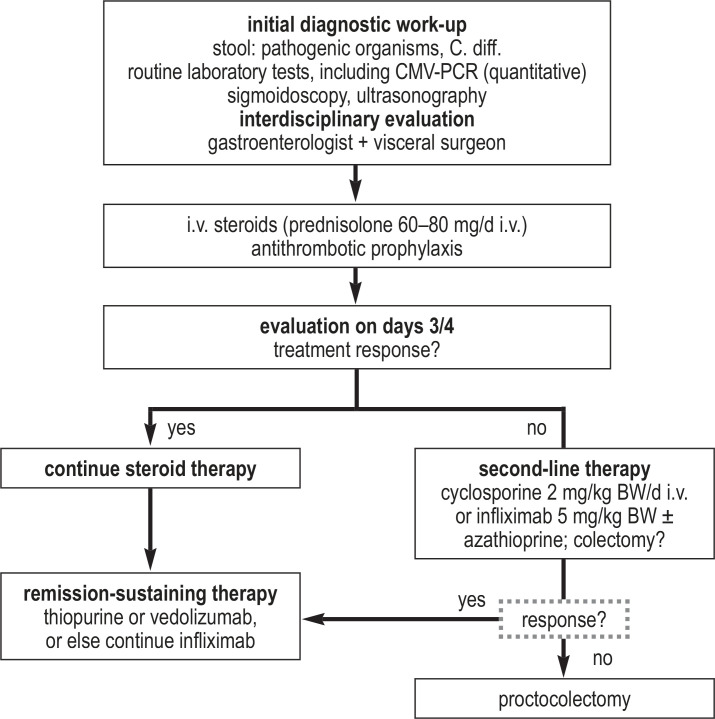

Fulminant colitis is a special clinical situation: as defined by Truelove und Witts (e13, e14), it is characterized by bloody diarrhea accompanied by tachy-cardia and severe anemia. Patients with these manifestations must be hospitalized. If there is no clear clinical improvement after three to four days of high-dose intravenous steroid treatment, the remaining treatment alternatives are either an emergency proctocolectomy, or else pharmacotherapy with cyclosporine (or tacrolimus) or infliximab (possibly in combination with azathioprine) (figure 3). Two randomized, controlled trials revealed no difference between these two types of treatment with respect to either short-term response or long-term therapeutic success (27, 28, e15). If a remission is induced under treatment with infliximab and azathioprine, remission-sustaining treatment can be carried out either with this combination, or else with one of these two drugs alone (depending on what the patient was taking before). If a remission is induced by cyclosporine, azathioprine can be used for remission-sustaining treatment, or, alternatively, TNF antibodies, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, or tofacitinib.

Figure 3.

Treatment algorithm for fulminant ulcerative colitis

BW, body weight; C. diff., Clostridioides difficile; CMV, cytomegalovirus; d, day; i.v., intravenous; PCR, polymerase chain reaction

If a remission cannot be induced with calcineurin inhibitors or TNF antibodies, a switch to yet another type of pharmacotherapy is generally not recommended, and proctocolectomy is advisable as the next treatment.

Surgery

Colectomy is the most common surgical treatment for ulcerative colitis. The reported colectomy rates in various studies range from 8% to 24% in ten years; the operation is usually performed on patients with pancolitis (e16). Medically refractory ulcerative colitis and colitis-associated neoplasia are the main indications for colectomy. The decision to operate should be taken by gastroenterologists and visceral surgeons in close interdisciplinary collaboration. The patient must be told preoperatively about the risk of “pouchitis,” i.e., acute or chronic inflammation of the small-bowel reservoir used as a rectum substitute, as well as the elevated risk of infertility (e17) and sexual dysfunction in both men and women (e18). The reported cumulative prevalence of pouchitis after one year, five years, and ten years is 15.5%, 36%, and 45.5%, respectively (e19).

Adenocarcinoma is an absolute indication for colectomy, as is epithelial dysplasia in a lesion that cannot be resected endoscopically (1). It was concluded in a recent meta-analysis that, even in low-grade epithelial dysplasia, the risk of carcinoma is 14 per 1000 patient-years [5.0; 34], corresponding to a ninefold risk elevation. Thus, proctocolectomy should be considered in this situation as well, with frequently scheduled surveillance colonoscopies as a non-surgical alternative. Colonic stenosis in a patient with ulcerative colitis is also a relative surgical indication, as there is otherwise no safe diagnostic technique with which to rule out malignancy; carcinoma or high-grade dysplasia is already present in approximately 7% of such stenoses (29). Limited (partial) colectomy should be performed only in rare special cases, which should be thoroughly discussed beforehand by an experienced visceral medical and surgical team. In patients who are at elevated surgical risk, or who have been treated with immune suppressants or biological agents right up to the time of surgery, proctocolectomy should be performed in a stepwise fashion, in three sequentially planned operations (30).

Special aspects of treatment in childhood and adolescence

Surgical treatment.

Colectomy is the most common surgical treatment for ulcerative colitis. The reported colectomy rates in various studies range from 8% to 24% in ten years; the operation is usually performed on patients with pancolitis

Multidisciplinary pediatric teams.

Children and adolescents with ulcerative colitis often have a rapidly progressive, complicated course and should be cared for by a multidisciplinary pediatric team for chronic inflammatory bowel diseases.

2000 to 2 600 children and adolescents newly develop a chronic inflammatory bowel disease in Germany every year, and more than a third of them have ulcerative colitis (31). Children of any age can be affected (e22). The younger the child at the time of diagnosis, the more likely it is that the inflammatory process is confined to the colon. Often, the disease cannot be unequivocally classified as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis even after a full diagnostic work-up, and it is then designated as an unclassified chronic inflammatory bowel disease (32). Other entities in the differential diagnosis, such as allergic enterocolitis or a monogenetic immune deficiency, should be ruled out. The initial diagnostic work-up always includes ileocoloscopy and upper endoscopy; in doubtful cases, the small intestine is also imaged (e23). In infants and toddlers with chronic inflammatory bowel disease, the initial work-up should be supplemented by immunological testing and, whenever a monogenetic disease is suspected from the family history or clinical presentation, by genetic testing as well, potentially up to whole-exome sequencing (WES) (33, e24).

Ulcerative colitis beginning in childhood or adolescence is characterized by a protracted course, high disease activity, and progression. Two-thirds of the affected pediatric patients have extensive colitis at the time of diagnosis (e22), in contrast to only 20–30% of adults (e23). A further special aspect of ulcerative colitis in children, aside from the rectal sparing mentioned above, is concomitant involvement of the upper gastrointestinal tract with an active, sometimes erosive or granulomatous gastritis (e23). In routine clinical practice, the degree of disease activity should be characterized with the PUCAI index. A higher percentage of children than adults must be hospitalized for the treatment of acute, severe colitis (e25, e26, 34). The rate of colectomy 10 years after diagnosis is higher in patients with childhood-onset disease than in those with adult-onset disease (e23, e27).

The aggressive course of ulcerative colitis in children and adolescents contrasts with the relative scarcity of therapeutic options and the different side-effect profile in this age group (34). Biological agents have been approved for the treatment of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases in children at an average of seven years’ delay after their approval for adults (e28). Only infliximab has been approved to date for the treatment of patients under 18 years of age with ulcerative colitis. Other biological agents can be used off label, but only after a prior guarantee of reimbursement from the patient’s insurance carrier (e29). Because of the different pharmacokinetics in childhood, these patients generally need higher drug doses (per kilogram of body weight) as well as follow-up at briefer intervals. The mortality of persons with ulcerative colitis with onset in childhood or adolescence is four times that of a reference population (e30, e31). The earlier the disease is diagnosed, the higher the risk of malignancy. Causes of death include complications of the disease itself (postoperative complications, emboli, infections, colon carcinoma from 10 years after the diagnosis onward) and of certain drugs used to treat it (e.g., cancer or HLH with thiopurine use, infections with the use of anti-TNF and corticosteroids). The tumor risk is already elevated in childhood (e32, e33).

When decisions about treatment are made, it must be borne in mind that children are still growing, and that they build up their bone mass over the course of the first two decades of life. Ulcerative colitis adversely affects these patients’ muscle mass as well as the growth, geometry, and quality of their bones, by both direct mechanisms (inflammation, enteric loss of protein and micronutrients) and indirect ones (lessened anabolic effect of sex hormones due to delayed puberty, nutritional deficiency due to lack of appetite or abdominal pain, decreased physical exercise due to active inflammation) (e34). Systemic corticosteroids, which patients with ulcerative colitis must often be given repeatedly, have unfavorable effects specifically when given during the years of pubertal growth spurt (e35).

Chronic inflammatory bowel disease in young patients threatens not only their physical health, but also their psychosocial and occupational development. In a study conducted in Germany by questionnaire and through diagnostic interviews with the patients and their parents, half of the children and adolescents with ulcerative colitis who were studied met the DSM-IV criteria for one or more mental illnesses—most commonly adaptive disorders, depression, and anxiety disorders (e36). Their quality of life (as measured by HRQoL IMPACT III and QoL EQ-5D) was markedly impaired and this correlated to the disease activity. Only a small fraction of the patients had been offered, or had received, treatment by a psychotherapist or child and adolescent psychiatrist. The psychosocial consequences and comorbidities have a markedly negative effect on the drug compliance of adolescent patients and on their transition to adult care. In summary, ulcerative colitis in children and adolescents poses a special challenge because of the severity of the disease and its adverse effects on physical and psychosocial development. These patients should, therefore, be treated at a center for chronic inflammatory bowel diseases in collaboration with a pediatric clinic. They should be cared for by an interdisciplinary team (pediatric gastroenterology, endocrinology, dietary counseling, psychology, social work, etc.), and appropriate provisions should be made for their transition to adult care.

The normal development of adolescent patients is at risk.

Chronic inflammatory bowel disease in young patients, with its chronic, recurring course, threatens not only their physical health, but also their psychosocial and occupational development.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Etiology and pathogenesis

A multifactorial origin of ulcerative colitis is currently postulated in which various extrinsic and intrinsic factors interact, including a genetic predisposition (the genome), environmental influences (the exposome), altered composition of the intestinal microbial flora (the microbiome), and the reactivity of the intestinal immune system (the immunome) (e40).

Findings from twin studies suggest that genetic factors play a lesser role in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease (the monozygotic and dizygotic concordance rates are 15% vs. 5% for ulcerative colitis and 20–50% vs. 10% for Crohn’s disease) (e41). Over 200 genes for chronic inflammatory bowel diseases have been identified in genome-wide association studies (e42). Many of the gene products are involved in inflammatory reactions or in the recognition of bacteria and the intestinal barrier. Some of the identified genetic loci are also associated with a variety of immune-mediated diseases; this accords with the elevated comorbidity of ulcerative colitis with autoimmune diseases affecting the joints, thyroid gland, liver, and biliary pathways, as well as with psoriasis (e43). Alongside the polygenetic predisposition to chronic inflammatory bowel diseases due to common genetic variants, there are also very rare monogenetic immune deficiency diseases that manifest themselves as chronic inflammatory bowel diseases in early childhood.

The term “exposome” refers to all non-genetic endogenous or exogenous environmental influences to which an individual is exposed. The importance of the exposome in the pathogenesis of the disease is implied by studies on migrants and by the fact that its incidence is rising all over the world. Epidemiologic studies have revealed a number of factors that lessen the risk of developing ulcerative colitis (e.g., breastfeeding, Mediterranean diet, smoking) and others that increase it (e.g., gastrointestinal infections, air pollution, oral contraceptive drugs).

The totality of the intestinal microbial flora is called the microbiome. In patients with ulcerative colitis, the microbiome is quantitatively and qualitatively altered, with a reduction of bacterial diversity and an increase in enterobacteriacea and certain other types of micro-organism. Initial studies have shown that fecal microbiome transfer may have a beneficial effect on ulcerative colitis, but there is as yet no definitive demonstration of a long-term therapeutic effect, nor has the method yet been standardized (e44).

The intestinal immune system is responsible for the immune surveillance of approximately circa 200 m² of luminal surface area. In the normal situation, there is immunological tolerance for harmless food antigens and the normal intestinal flora. In contrast, pathogens and their antigens must be recognized, regulated, and warded off with appropriate inflammatory defense strategies. Disturbances in the complex interplay of the congenital and acquired immune response and the intestinal barrier play a role in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis (e40).

Epidemiology

The reported incidence of ulcerative colitis in Germany is approximately 4 per 100 000 persons per year, and a prevalence of at least 90 per 100 000 persons has been estimated. These figures may well be underestimates, however, because there is no registry for the disease and the available epidemiologic data are poor. In particular, mildly affected patients are often treated solely by their family physicians, and the disease is occasionally misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome or hemorrhoids. A current realistic assumption is that there are approximately 150 000 or more patients with ulcerative colitis in Germany (e45, e46). The peak age-specific incidence is between the ages of 25 and 35 (circa 4.5/100 000), with a less pronounced increase from age 55 onward. There has been little change in the incidence of ulcerative colitis in Europe and North America in recent years, but it has risen in all age groups in the newly industrializing countries of South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia (e47). Within Europe, there is a marked east-west gradient, with a marked recent increase in incidence in eastern European countries (e48).

Further information on CME.

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 16 August 2021. Submissions by letter, e-mail or fax cannot be considered.

All new CME units will be accessible for 12 months. The results can be downloaded starting four weeks after the beginning of each CME unit. Please be aware of the submission deadlines, which can be found at cme.aerzteblatt.de.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN), which is found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX). The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (“Mein DÄ”) or else entered in “Meine Daten,” and the participant must agree to communication of the results.

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 16 August 2021.

Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Which of the following is considered a reliable marker of remission in ulcerative colitis?

fecal calprotectin <150–200 µg/g

moderate wall thickening (>3 mm) with submucosal edema

normalization of serum CRP

reduction of stool frequency

weight gain and stool continence

Question 2

The primary pharmacotherapy of mild to moderate ulcerative proctitis consists of which of the following?

prednisolone

budesonide

budesonide foam

mesalamine

betamethasone 5 mg enemas

Question 3

The primary pharmacotherapy of mildly to moderately extensive ulcerative colitis consists of which of the following?

prednisolone 1 mg/kg BW /d p.o.

mesalamine ≥ 3 g/d + mesalamine p.r.

prednisolone 1 mg/kg BW p.o. + mesalamine 3 g/d p.o.

azathioprine 2.5 mg/kg BW/d p.o.

mesalamine enemas 4 g/d

Question 4

How should steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis be treated?

with TNF antibodies + JAK inhibitors

with azathioprine + vedolizumab

with long-term low-dose steroids

with high-dose mesalamine

with an immune suppressant, biological drug, or JAK inhibitor, depending on individual risk assessment

Question 5

In a patient with severe ulcerative colitis, which of the following is a worrisome prognostic sign with respect to the development of fulminant colitis?

recurrent diarrhea and fatigue

elevated serum CRP and insomnia

elevated stool calprotectin and fatigue

worsening iron-deficiency anemia in a pubescent patient

abdominal tenderness, fever, and peritoneal signs

Question 6

Which of the following is a reasonable second-line treatment option for fulminant ulcerative colitis?

budesonide p.r.

aminosalicylates

cyclosporine/tacrolimus or infliximab

azathioprine p.o.

increasing the dose of mesalamine

Question 7

What is the most important differential diagnosis of ulcerative colitis?

Crohn’s disease

underlying malignancy

appendicitis

Clostridioides difficile infection

rotavirus infection

Question 8

According to current guidelines, what should be ruled out in patients with treatment-resistant ulcerative colitis?

CMV reactivation

staphylococcal infection

dietary intolerance

hematochezia

nutritional deficiency

Question 9

Which of the following particularly applies to ulcerative colitis in children?

Fewer than one-third of patients have pancolitis at the time of their diagnosis.

a mildly progressive course.

common additional involvement of the upper GI tract

frequent spontaneous remission

low disease activity

Question 10

According to a German study, what is among the more common psychiatric comorbidities in children and adolescents with ulcerative colitis?

fatigue

bipolar disorder

adaptive disorder

autism

motor tics

► Participation is possible only via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Kucharzik has served as a paid consultant for Abbvie, Amgen, Biogen, Mundipharma, Hospira, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, MSD Sharp & Dome GmbH, and Novartis. He has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees and of travel and accommodation expenses from Abbvie, Janssen, MSD, and Takeda. He has received honoraria for preparing continuing medical education events from Abbvie, Falk, Janssen, MSD, Takeda, and Ferring Arzneimittel GmbH.

Prof. Koletzko has served as a paid consultant for Abbvie, Celgene, Takeda, Janssen, Vifor und Pharmacosmos. She he has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees and of travel and accommodation expenses from MSD, Pfizer, Takeda, and Abbvie, and lecture honoraria from Pfizer, Takeda, Abbvie, and Janssen.

Dr. Kannengiesserhas received reimbursement of meeting participation fees and of travel and accommodation expenses from Abbvie and MSD Sharp & Dome GmbH, and lecture honoraria from Abbvie, Janssen, and Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH.

Prof. Dignass has served as a paid consultant for Abbvie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Falk, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Hexal, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda, Tillotts, Vifor, and Pharmacosmos. He has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees and of travel and accommodation expenses from Falk, Ferring, Janssen, Takeda, and Tillotts. He has received honoraria for lectures and for preparing continuing medical education events from Abbvie, Falk, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Takeda, and Tillotts.

References

- 1.Kucharzik T, Dignass AU, Atreya R, et al. [August 2019 - AWMF-Registriernummer: 021-009] Z Gastroenterol. 2019;57:1321–1405. doi: 10.1055/a-1015-7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, et al. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis Part 2: Current Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:769–784. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdulrazeg O, Li B, Epstein J. Guideline: Management of ulcerative colitis: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2019;367 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5897. l5897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dignass AU, Gasche C, Bettenworth D, et al. European consensus on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anaemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:211–222. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jju009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:144–164. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sturm A, Maaser C, Calabrese E, et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 2: IBD scores and general principles and technical aspects. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:273–284. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maaser C, Petersen F, Helwig U, et al. Intestinal ultrasound for monitoring therapeutic response in patients with ulcerative colitis: results from the TRUST&UC study. Gut. 2019 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319451. gutjnl-2019-319451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi CH, Rutter MD, Askari A, et al. Forty-year analysis of colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: an updated overview. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1022–1034. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Parker CE, Bhanji T, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000543.pub4. CD000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000544.pub4. CD000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford AC, Khan KJ, Achkar JP, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of oral vs topical, or combined oral and topical 5-aminosalicylates, in Ulcerative Colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:167–176. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.410. author reply 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marteau P, Probert CS, Lindgren S, et al. Combined oral and enema treatment with Pentasa (mesalamine) is superior to oral therapy alone in patients with extensive mild/moderate active ulcerative colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Gut. 2005;54:960–965. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.060103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Losurdo G, Iannone A, Contaldo A, Ierardi E, Di Leo A, Principi M. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in ulcerative colitis treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24:499–505. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.244.ecn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall JK, Thabane M, Steinhart AH, Newman JR, Anand A, Irvine EJ. Rectal 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004118.pub2. CD004118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feagan BG, Macdonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000544.pub3. CD000544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, et al. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:431–440. doi: 10.1080/00365520802600961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomollon F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of crohn‘s disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3–25. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723–1736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonovas S, Lytras T, Nikolopoulos G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: comparative assessment of tofacitinib and biological therapies for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:454–465. doi: 10.1111/apt.14449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh S, Fumery M, Sandborn WJ, Murad MH. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: first- and second-line pharmacotherapy for moderate-severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:162–175. doi: 10.1111/apt.14422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr., et al. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215–1226. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandborn WJ, Su C, Panes J. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:496–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1707500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Woude CJ, Ardizzone S, Bengtson MB, et al. The second European evidenced-based consensus on reproduction and pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:107–124. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jju006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annese V, Beaugerie L, Egan L, et al. European evidence-based consensus: inflammatory bowel disease and malignancies. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:945–965. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:443–468. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with steroid-refractory acute severe UC treated with ciclosporin or infliximab. Gut. 2018;67:237–243. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams JG, Alam MF, Alrubaiy L, et al. Infliximab versus ciclosporin for steroid-resistant acute severe ulcerative colitis (CONSTRUCT): a mixed methods, open-label, pragmatic randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:15–24. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fumery M, Pineton de Chambrun G, Stefanescu C, et al. Detection of dysplasia or cancer in 3.5% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and colonic strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1770–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oresland T, Bemelman WA, Sampietro GM, et al. European evidence based consensus on surgery for ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:4–25. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wittig R, Albers L, Koletzko S, Saam J, Kries RV. Pediatric chronic inflammatory bowel disease in a German statutory health INSURANCE - incidence rates from 2009 - 2012. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68:244–250. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, et al. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:795–806. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uhlig HH, Schwerd T, Koletzko S, et al. The diagnostic approach to monogenic very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:990–1007e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner D, Ruemmele FM, Orlanski-Meyer E, et al. Management of paediatric ulcerative colitis, part 1: Ambulatory care-an evidence-based guideline from European Crohn‘s and Colitis Organization and European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67:257–291. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandborn WJ, Danese S, D‘Haens G, et al. Induction of clinical and colonoscopic remission of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with budesonide MMX 9 mg: pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:409–418. doi: 10.1111/apt.13076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and mainte-nance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:257–265e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, et al. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:85–95; quiz e14-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, et al. Subcutaneous golimumab maintains clinical response in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:96–109e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Park SH, Kim YM, Yang SK, et al. Clinical features and natural history of ulcerative colitis in Korea. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:278–283. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Annese V, Daperno M, Rutter MD, et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:982–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Selinger CP, Andrews JM, Titman A, et al. Long-term follow-up reveals low incidence of colorectal cancer, but frequent need for resection, among Australian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:644–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Olen O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:123–131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Panes J, Bouhnik Y, Reinisch W, et al. Imaging techniques for assessment of inflammatory bowel disease: joint ECCO and ESGAR evidence-based consensus guidelines. Journal of Crohn‘s & colitis. 2013;7:556–585. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Marshall JK, Irvine EJ. Rectal corticosteroids versus alternative treatments in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 1997;40:775–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.6.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Travis SP, Danese S, Kupcinskas L, et al. Once-daily budesonide MMX in active, mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: results from the randomised CORE II study. Gut. 2014;63:433–441. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Sandborn WJ, Travis S, Moro L, et al. Once-daily budesonide MMX(R) extended-release tablets induce remission in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis: results from the CORE I study. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1218–1226e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Velayos FS, Terdiman JP, Walsh JM. Effect of 5-aminosalicylate use on colorectal cancer and dysplasia risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1345–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Lawrance IC, Baird A, Lightower D, Radford-Smith G, Andrews JM, Connor S. Efficacy of rectal tacrolimus for induction therapy in patients with resistant ulcerative proctitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1248–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Lie M, Kreijne JE, Dijkstra G, et al. No superiority of tacrolimus suppositories vs beclomethasone suppositories in a randomized trial of patients with refractory ulcerative proctitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1777–1784e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Wagner N, Assmus F, Arendt G, et al. Impfen bei Immundefizienz: Anwendungshinweise Zu den von der Ständigen Impfkommission Empfohlenen Impfungen (IV) Impfen bei Autoimmunkrankheiten, bei anderen chronisch-entzündlichen Erkrankungen und unter immunmodulatorischer Therapie. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2019;62:494–515. doi: 10.1007/s00103-019-02905-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Edwards FC, Truelove SC. The course and prognosis of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1963;4:299–315. doi: 10.1136/gut.4.4.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2:1041–1048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4947.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1909–1915. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Cottone M, Scimeca D, Mocciaro F, Civitavecchia G, Perricone G, Orlando A. Clinical course of ulcerative colitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40(2):S247–S252. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(08)60533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Hahnloser D, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. Pregnancy and delivery before and after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for inflammatory bowel disease: immediate and long-term consequences and out-comes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1127–1135. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0569-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Kjaer MD, Laursen SB, Qvist N, Kjeldsen J, Poornoroozy PH. Sexual function and body image are similar after laparoscopy-assisted and open ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. World J Surg. 2014;38:2460–2465. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2557-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Penna C, Dozois R, Tremaine W, et al. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis occurs with increased frequency in patients with associated primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 1996;38:234–239. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Thomas T, Abrams KR, De Caestecker JS, Robinson RJ. Meta analysis: cancer risk in Barrett‘s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1465–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Thomas T, Abrams KA, Robinson RJ, Mayberry JF. Meta-analysis: cancer risk of low-grade dysplasia in chronic ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:657–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Buderus S, Scholz D, Behrens R, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric patients—characteristics of newly diagnosed patients from the CEDATA-GPGE registry. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:121–127. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Drummond HE, et al. Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1114–1122. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Ouahed J, Spencer E, Kotlarz D, et al. Very early onset inflammatory bowel disease: a clinical approach with a focus on the role of genetics and underlying immune deficiencies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:820–842. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Turner D, Walsh CM, Benchimol EI, et al. Severe paediatric ulcerative colitis: incidence, outcomes and optimal timing for second-line therapy. Gut. 2008;57:331–338. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.136481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Dinesen LC, Walsh AJ, Protic MN, et al. The pattern and outcome of acute severe colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Gower-Rousseau C, Dauchet L, Vernier-Massouille G, et al. The natural history of pediatric ulcerative colitis: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2080–2088. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Turner D, Griffiths AM, Wilson D, et al. Designing clinical trials in paediatric inflammatory bowel diseases: a PIBDnet commentary. Gut. 2020;69:32–41. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Däbritz J, Gerner P, Enninger A, Claßen M, Radke M. Inflammatory bowel disease in childhood and adolescence—diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:331–338. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Malham M, Jakobsen C, Paerregaard A, et al. The incidence of cancer and mortality in paediatric onset inflammatory bowel disease in Denmark and Finland during a 23-year period: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:33–39. doi: 10.1111/apt.15258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Jess T, Frisch M, Simonsen J. Trends in overall and cause-specific mortality among patients with inflammatory bowel disease from 1982 to 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Hyams JS, Dubinsky MC, Baldassano RN, et al. Infliximab is not associated with increased risk of malignancy or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1901–1914e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Joosse ME, Aardoom MA, Kemos P, et al. Malignancy and mortality in paediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a 3-year prospective, multinational study from the paediatric IBD Porto group of ESPGHAN. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:523–537. doi: 10.1111/apt.14893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Timmer A, Behrens R, Buderus S, et al. Childhood onset inflammatory bowel disease: predictors of delayed diagnosis from the CEDATA German-language pediatric inflammatory bowel disease registry. J Pediatr. 2011;158:467–473e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Tsampalieros A, Lam CK, Spencer JC, et al. Long-term inflammation and glucocorticoid therapy impair skeletal modeling during growth in childhood Crohn disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3438–3445. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Engelmann G, Erhard D, Petersen M, et al. Health-related quality of life in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease depends on disease activity and psychiatric comorbidity. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2015;46:300–307. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Christophi GP, Rengarajan A, Ciorba MA. Rectal budesonide and mesalamine formulations in active ulcerative proctosigmoiditis: efficacy, tolerance, and treatment approach. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:125–130. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S80237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Timmer A, Patton PH, Chande N, et al. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000478.pub4. CD000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1713–1725. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1102942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E41.Halfvarson J, Jess T, Magnuson A, et al. Environmental factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a co-twin control study of a Swedish-Danish twin population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:925–933. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000228998.29466.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Furey TS, Sethupathy P, Sheikh SZ. Redefining the IBDs using genome-scale molecular phenotyping. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:296–311. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0118-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Alinaghi F, Tekin HG, Burisch J, Wu JJ, Thyssen JP, Egeberg A. Global prevalence and bidirectional association between psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease-a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:351–360. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Imdad A, Nicholson MR, Tanner-Smith EE, et al. Fecal transplantation for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Data-base Syst Rev. 2018;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012774.pub2. CD012774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.Baumgart DC. The diagnosis and treatment of Crohn‘s disease and ulcerative colitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:123–133. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E46.Timmer A, Goebell H. Incidence of ulcerative colitis, 1980-1995—a prospective study in an urban population in Germany. Z Gastroenterol. 1999;37:1079–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2018;390:2769–2778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E48.Burisch J, Pedersen N, Cukovic-Cavka S, et al. East-west gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63:588–597. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Etiology and pathogenesis

A multifactorial origin of ulcerative colitis is currently postulated in which various extrinsic and intrinsic factors interact, including a genetic predisposition (the genome), environmental influences (the exposome), altered composition of the intestinal microbial flora (the microbiome), and the reactivity of the intestinal immune system (the immunome) (e40).

Findings from twin studies suggest that genetic factors play a lesser role in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease (the monozygotic and dizygotic concordance rates are 15% vs. 5% for ulcerative colitis and 20–50% vs. 10% for Crohn’s disease) (e41). Over 200 genes for chronic inflammatory bowel diseases have been identified in genome-wide association studies (e42). Many of the gene products are involved in inflammatory reactions or in the recognition of bacteria and the intestinal barrier. Some of the identified genetic loci are also associated with a variety of immune-mediated diseases; this accords with the elevated comorbidity of ulcerative colitis with autoimmune diseases affecting the joints, thyroid gland, liver, and biliary pathways, as well as with psoriasis (e43). Alongside the polygenetic predisposition to chronic inflammatory bowel diseases due to common genetic variants, there are also very rare monogenetic immune deficiency diseases that manifest themselves as chronic inflammatory bowel diseases in early childhood.

The term “exposome” refers to all non-genetic endogenous or exogenous environmental influences to which an individual is exposed. The importance of the exposome in the pathogenesis of the disease is implied by studies on migrants and by the fact that its incidence is rising all over the world. Epidemiologic studies have revealed a number of factors that lessen the risk of developing ulcerative colitis (e.g., breastfeeding, Mediterranean diet, smoking) and others that increase it (e.g., gastrointestinal infections, air pollution, oral contraceptive drugs).

The totality of the intestinal microbial flora is called the microbiome. In patients with ulcerative colitis, the microbiome is quantitatively and qualitatively altered, with a reduction of bacterial diversity and an increase in enterobacteriacea and certain other types of micro-organism. Initial studies have shown that fecal microbiome transfer may have a beneficial effect on ulcerative colitis, but there is as yet no definitive demonstration of a long-term therapeutic effect, nor has the method yet been standardized (e44).

The intestinal immune system is responsible for the immune surveillance of approximately circa 200 m² of luminal surface area. In the normal situation, there is immunological tolerance for harmless food antigens and the normal intestinal flora. In contrast, pathogens and their antigens must be recognized, regulated, and warded off with appropriate inflammatory defense strategies. Disturbances in the complex interplay of the congenital and acquired immune response and the intestinal barrier play a role in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis (e40).

Epidemiology

The reported incidence of ulcerative colitis in Germany is approximately 4 per 100 000 persons per year, and a prevalence of at least 90 per 100 000 persons has been estimated. These figures may well be underestimates, however, because there is no registry for the disease and the available epidemiologic data are poor. In particular, mildly affected patients are often treated solely by their family physicians, and the disease is occasionally misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome or hemorrhoids. A current realistic assumption is that there are approximately 150 000 or more patients with ulcerative colitis in Germany (e45, e46). The peak age-specific incidence is between the ages of 25 and 35 (circa 4.5/100 000), with a less pronounced increase from age 55 onward. There has been little change in the incidence of ulcerative colitis in Europe and North America in recent years, but it has risen in all age groups in the newly industrializing countries of South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia (e47). Within Europe, there is a marked east-west gradient, with a marked recent increase in incidence in eastern European countries (e48).