Abstract

目的

探讨寰枢前脱位枕颈融合术患者 O-EA 角与下颈椎曲度的关系及其对下颈椎曲度的影响。

方法

回顾分析 2010 年 4 月—2018 年 7 月收治且符合选择标准的 61 例合并寰枢前脱位行枕颈融合术患者临床资料。男 32 例,女 29 例;年龄 14~76 岁,平均 50.7 岁。固定节段:C0~C2 19 例,C0~C3 27 例,C0~C4 14 例,C0~C5 1 例。术前及末次随访时测量 O-EA 角、C2~7 Cobb 角和 T1 倾斜角;根据末次随访时所测 O-EA 角,将患者分为<95° 组(A 组)、95°~105° 组(B 组)、>105° 组(C 组),比较各组患者性别、年龄、固定节段(在 C3 及以上为短节段,C3 以远为长节段)和 C2~7 Cobb 角。对术前、末次随访时 O-EA 角和 C2~7 Cobb 角之间,以及二者手术前后的变化值进行相关性分析。

结果

61 例患者术后均获随访,随访时间 12~24 个月,平均 22.4 个月。患者术前及末次随访时 O-EA 角、C2~7 Cobb 角和 T1 倾斜角比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。根据末次随访时 O-EA 角分组,A 组 14 例、B 组 29 例、C 组 18 例。3 组患者年龄、性别构成、固定节段构成比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05);3 组间 C2~7 Cobb 角比较差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05),A、B、C 组呈逐渐增加趋势。术前、末次随访时 O-EA 角与 C2~7 Cobb 角均成正相关(r=0.572,P=0.000;r=0.618,P=0.000);末次随访时 O-EA 角变化与 C2~7 Cobb 角变化亦成正相关(r=0.446,P=0.000)。

结论

合并寰枢前脱位患者的 O-EA 角与 C2~7 Cobb 角成正相关,行枕颈固定术中应避免 O-EA 角过大,否则可能加速下颈椎退变。

Keywords: 枕颈融合术, O-EA 角, 下颈椎曲度, 寰枢前脱位

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between O-EA angle and lower cervical curvature in patients with anterior atlantoaxial dislocation undergoing occipitocervical fusion, and to analyze the effect of O-EA angle on lower cervical curvature.

Methods

The clinical data of 61 patients with anterior atlantoaxial dislocation undergoing occipitocervical fusion who were admitted between April 2010 and July 2018 and met the selection criteria were retrospectively analyzed. There were 32 males and 29 females, with an age of 14-76 years (mean, 50.7 years). The fixed segment included 19 cases of C0-C2, 27 cases of C0-C3, 14 cases of C0-C4, and 1 case of C0-C5. The O-EA angle, C2-7 Cobb angle, and T1 tilt angle were measured before operation and at last follow-up. According to the O-EA angle measured at last follow-up, the patients were divided into <95° group (group A), 95°-105° group (group B), and >105° group (group C), and compared the differences of gender, age, fixed segment (short segment was at C 3 and above, long segment was beyond C3), and C2-7 Cobb angle. Correlation analysis between the O-EA angle and C2-7 Cobb angle before operation and at last follow-up, as well as the changes of O-EA angle and C2-7 Cobb angle between before operation and at last follow-up were analyzed.

Results

All 61 patients were followed up 12-24 months, with an average of 22.4 months. There was no significant difference in O-EA angle, C2-7 Cobb angle, and T1 tilt angle before operation and at last follow-up (P>0.05). According to the last follow-up O-EA angle grouping, there were 14 cases in group A, 29 cases in group B, and 18 cases in group C. There was no significant difference in age, gender composition, and fixed segment composition among the three groups (P>0.05); the differences in C2-7 Cobb angles among the three groups were significant (P<0.05), groups A, B, and C showed a gradually increasing trend. The O-EA angle was positively correlated with C2-7 Cobb angle before operation and at last follow-up (r=0.572, P=0.000; r=0.618, P=0.000); O-EA angle change at last follow-up was also positively correlated with C2-7 Cobb change (r=0.446, P=0.000).

Conclusion

The O-EA angle of patients with anterior atlantoaxial dislocation is positively correlated with C2-7 Cobb angle. Too large O-EA angle should be avoided during occipitocervical fixation, otherwise it may accelerate the degeneration of the lower cervical spine.

Keywords: Occipitocervical fusion, O-EA angle, lower cervical curvature, anterior atlantoaxial dislocation

枕颈融合术常用于治疗由外伤、肿瘤、类风湿关节炎、先天性畸形、退变导致的颅颈交界不稳或脱位患者,具有良好稳定性和较高融合率[1]。然而枕颈角固定不当会引起下颈椎曲度超出正常范围,轻者可能加速下颈椎退变[2],严重者出现下颈椎半脱位并发症[3-5]。枕颈角的测量方式包括由 McGregor 线、Chamberlain 线、McRae 线分别和 C2 椎体下终板平行线构成的夹角,其中由 McGregor 线和 C2 椎体下终板平行线构成的夹角(O-C2 角),由于具有可重复性和可靠性而被广泛应用[6];之后有文献报道了后枕颈角[O-C3 角(occiput-C3 angle)和 POC 角(posterior occipitocervical angle)][7]。但上述枕颈角在合并寰枢前脱位患者中不能体现寰椎复位时口咽部气道最短径的变化。O-EA 角(两侧外耳道连线中点和 C2 椎体下终板中点形成的直线与 McGregor 线的夹角)则能弥补上述枕颈角的局限性[8-9]。目前尚无相关文献报道枕颈融合术后 O-EA 角与下颈椎曲度变化的关系,因此我们通过回顾性研究对此进行分析,探讨合并寰枢前脱位患者枕颈融合术后 O-EA 角的最佳角度。报告如下。

1. 临床资料

1.1. 患者选择标准

纳入标准:① 实施枕颈融合术治疗的合并寰枢前脱位[10]患者;② 随访时间超过 1 年;③ 随访资料完整。排除标准:既往有枕颈部手术史者。2010 年 4 月—2018 年 7 月共 61 例患者符合选择标准纳入研究。

1.2. 一般资料

本组男 32 例,女 29 例;年龄 14~76 岁,平均 50.7 岁。颅底凹陷症伴寰枢前脱位 37 例,陈旧性齿状突骨折不愈合或齿状突不连合并难复性寰枢前脱位 20 例,类风湿性关节炎合并寰枢前脱位同时关节面破坏及骨质疏松 4 例。固定节段:C0~C2 19 例,C0~C3 27 例,C0~C4 14 例,C0~C5 1 例。

1.3. 手术方法

患者于气管插管全麻下取俯卧位,神经电生理监测脊髓功能。术前行颅骨牵引者(28 例)继续颅骨牵引;未行颅骨牵引者(33 例)将 Mayfield 头架与头部固定后安置于手术床上并锁定牢靠。常规消毒、铺巾,根据手术拟固定范围显露枕外隆突至 C3 棘突、双侧椎板及关节突或以远,于 C2 棘突剥离头下斜肌、头后大直肌,标记肌肉起点,便于肌肉起点重建。显露完毕后,采用 Mayfield 头架固定头部者调整头架,使头部固定于中立位。C2 常采用椎弓根螺钉技术植钉,本组 5 例椎动脉高跨影响椎弓根螺钉植入,则植入椎板钉代替;其余固定节段采用侧块螺钉技术植入侧块螺钉。植钉完毕后截取适当长度钛棒,将模板按照枕骨弧度、枕颈交界区角度预弯,然后将钛棒对照模板预弯;于钛棒头端安置 3 枚螺钉连接器,将钛棒固定于颈椎螺钉 U 形槽内,安装螺帽暂不锁紧,经双侧钛棒连接器在枕骨鳞部相应位置植入 2~3 对枕骨螺钉,长度 1.0~1.2 cm,并锁紧枕骨螺钉,予以两步撑开复位后固定[11];然后用骨刀或高速磨钻于枕骨后正中双侧钛棒间小心去皮质,打磨寰椎后弓及相应固定节段的棘突基底部、双侧椎板制备植骨床,大量生理盐水冲洗术区,将自体髂骨制成颗粒状松质骨铺于已准备的植骨床表面,适当压紧。如果远端固定至 C2,则在枕骨与 C2 棘突间植入合适长度的自体髂骨块,并用螺钉牢靠固定于枕骨。行 C2 棘突起止点肌肉重建,双极电凝彻底止血,安放 1~2 根负压引流管,逐层缝合切口,无菌敷料覆盖并固定。

1.4. 观测指标

术前及末次随访时摄颈椎侧位 X 线片,在图像存储与传输系统(PACS)图像工作站中测量 O-EA 角、C2~7 Cobb 角(C2 椎体下终板线垂线与 C7 椎体下终板线垂线的夹角)和 T1 倾斜角(T1 椎体上终板线与水平线形成的夹角)。由 2 名医生相隔 1 周测量 2 次,取平均值。

根据末次随访时所测 O-EA 角,将患者分为<95° 组(A 组)、95°~105° 组(B 组)、>105° 组(C 组),比较 3 组患者性别、年龄、固定节段(在 C3 及以上为短节段,C3 以远为长节段)和 C2~7 Cobb 角。对术前、末次随访时 O-EA 角和 C2~7 Cobb 角之间,以及末次随访时二者与术前的变化值进行相关性分析。

1.5. 统计学方法

采用 SPSS19.0 统计软件进行分析。计量资料以均数±标准差表示,手术前后比较采用配对 t 检验;不同 O-EA 角组间比较采用单因素方差分析,两两比较采用 LSD 或 Dunnett t 检验。计数资料以率表示,组间比较采用 χ2 检验。相关性分析采用 Pearson 相关。检验水准 α=0.05。

2. 结果

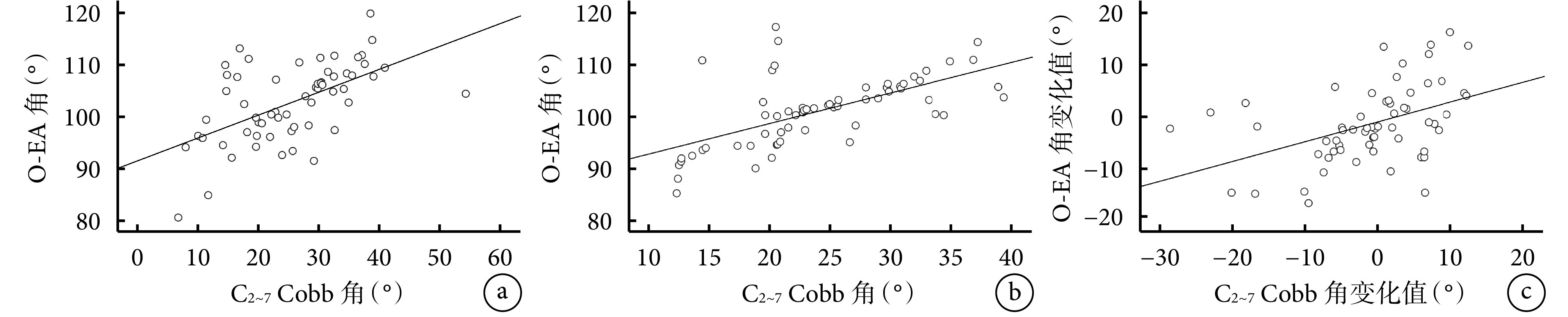

61 例患者术后均获随访,随访时间 12~24 个月,平均 22.4 个月。患者术前及末次随访时 O-EA 角、C2~7 Cobb 角和 T1 倾斜角比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 1。根据末次随访时 O-EA 角分组,A 组 14 例、B 组 29 例、C 组 18 例。3 组患者年龄、性别构成、固定节段构成比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05);3 组间 C2~7 Cobb 角比较差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05)。见表 2,图 1。术前、末次随访时 O-EA 角与 C2~7 Cobb 角均成正相关(r=0.572,P=0.000;r=0.618,P=0.000);末次随访时 O-EA 角变化与 C2~7 Cobb 角变化亦成正相关(r=0.446,P=0.000)。见图 2。

表 1.

Comparison of imaging angles of patients before ope ration and at last follow-up (n=61,

, °)

, °)

术前及末次随访时患者各影像学角度比较(n=61,

,°)

,°)

| 时间

Time |

O-EA 角

O-EA angle |

C2~7 Cobb 角

C2-7 Cobb angle |

T1 倾斜角

T1 tilt angle |

| 术前

Preoperative |

102.52±7.43 | 25.34±9.73 | 21.25±4.05 |

| 末次随访

Last follow-up |

101.03±6.80 | 24.09±7.16 | 20.67±3.72 |

| 统计值

Statistic |

t=1.571

P=0.121 |

t=1.049

P=0.298 |

t=0.954

P=0.344 |

表 2.

Comparison of clinical data in different O-EA angle groups

不同 O-EA 角组各临床资料比较

| 组别

Group |

例数

n |

年龄(岁)

Age (years) |

性别(男/女)

Gender (male/female) |

固定节段(短/长)

Fixed segment (short/long) |

C2~7 Cobb 角(°)

C2-7 Cobb angle (°) |

|

*与 A 组比较 P<0.05,#与 B 组比较 P<0.05

*Compared with group A, P<0.05;#compared with group B, P<0.05 | |||||

| A | 14 | 51.43±16.24 | 9/5 | 11/3 | 15.74±3.35# |

| B | 29 | 50.41±14.44 | 15/14 | 20/9 | 25.15±4.97* |

| C | 18 | 50.44±13.60 | 8/10 | 15/3 | 28.89±6.93*# |

| 统计值

Statistic |

F=0.025

P=0.975 |

χ2=1.255

P=0.536 |

χ2=1.358

P=0.554 |

F=25.011

P=0.000 |

|

图 1.

Lateral X-ray films of a 47-year-old female patient presented with basilar invagination and anterior atlantoaxial dislocation (fixed segment C0-C2)

患者,女,47 岁,颅底凹陷症合并寰枢前脱位(固定节段 C0~C2)侧位 X 线片

a. 术前;b. 术后 24 个月

a. Before operation; b. At 24 months after operation

图 2.

Correlation analysis between O-EA angle and C2-7 Cobb angle

O-EA 角与 C2~7 Cobb 角相关性分析

a. 术前;b. 末次随访;c. 变化值

a. Before operation; b. At last follow-up; c. Change value

3. 讨论

3.1. 上颈椎序列与下颈椎序列的相关性

颈椎序列包括上颈椎序列(即枕颈角)和下颈椎序列(即 C2~7 Cobb 角),有研究发现颈椎序列异常可加速颈椎退变。Okada 等[12]对 113 例无症状健康志愿者随访 10 年发现,40 岁以上者颈椎序列异常(颈椎变直、颈椎反屈)组椎间盘后凸进展更为频繁,随着年龄增长,颈椎序列异常会加速颈椎退变发生,但不一定会出现相应临床症状。Miyazaki 等[13]通过动态颈椎 MRI(前屈、中立、后伸位)研究发现,异常颈椎序列可导致颈椎节段应力增大,加速颈椎退变。Passias 等[10]研究了 58 例寰枢前脱位患者术前及术后影像学资料,发现上颈椎序列 O-C2 角与下颈椎序列 C2~7 Cobb 角成负相关,并且下颈椎退变疾病发生与术后 O-C2 角成正相关,而与 C2~7 Cobb 角成负相关。Inada 等[14]研究了 17 例由各种原因所致的寰枢关节脱位患者,发现枕颈融合术后 O-C2 角与 C2~7 Cobb 角成负相关,O-C2 角增加时,下颈椎曲度则减小,来代偿 O-C2 角的变化,作者提出在行枕颈融合术过程中应避免 O-C2 角过大,以免下颈椎曲度减小甚至后凸。王圣林等[5]纳入 148 例寰枢前脱位或不稳患者进行研究,发现上颈椎序列 O-C2 角、C1、2 角与下颈椎序列 C2~7 Cobb 角之间存在显著负相关,寰枢前脱位导致下颈椎过度前凸(C2~7 Cobb 角增大),这一现象可能会加速下颈椎退变。

3.2. O-EA 角与 C2~7 Cobb 角的相关性

本研究中寰枢前脱位患者 O-EA 角与 C2~7 Cobb 角之间成正相关,提示随着寰枢前脱位被纠正,O-EA 角减小,C2~7 Cobb 角也随之减小,其原因为寰枢前脱位患者头部重心发生前移,为了保持重心平衡和平视,下颈椎代偿性后伸,使得下颈椎曲度变大[5],此时经手术复位寰枢关节后,头部重心向后不同程度移动,受重心平衡机制的影响,下颈椎曲度减小。O-EA 角能反映头部重心移动过程,重心前移时 O-EA 角增加,后移时 O-EA 角减小。本研究结果显示 O-EA 角>105° 时 C2~7 Cobb 角明显增大,可能会加速下颈椎退变。

3.3. 影响下颈椎曲度变化的其他因素

下颈椎曲度的影响因素除了枕颈角外,脊柱其他部位(胸椎、腰椎或骶椎)发生矢状位失衡时,下颈椎曲度也会发生代偿性变化[15-16]。Hey 等[17]认为颈椎具有不同的正常形态,决定颈椎正常矢状位序列的因素包括 T1 倾斜角和矢状垂直轴。有研究表明,T1 倾斜角在评估全脊柱矢状位平衡中有一定作用,T1 倾斜角<13° 或>25° 时需要摄全脊柱 X 线片了解整个脊柱的矢状位平衡情况[18]。Matsubayashi 等[19]纳入 27 例因枕颈畸形接受枕颈融合术患者,研究 T1 倾斜角、O-C2 角、CO-C7 角以及 C2-C7 角之间的关系,发现 T1 倾斜角与 CO-C7 角之间手术前后均存在明显相关性,T1 倾斜角与 C2-C7 角之间也存在相关性,但相关程度较前者稍弱。有研究报道在行颈椎后路椎板成形术的患者中,术前 T1 倾斜角越大,术后发生颈椎曲度减小甚至后凸的概率越高[20-21];也有文献报道 T1 倾斜角与术后颈椎曲度减小和后凸无显著关系[22]。本研究中患者术前及末次随访时 T1 倾斜角均在正常范围内[23],排除 T1 倾斜角变化对下颈椎曲度的影响。

此外,性别和年龄对下颈椎曲度也有一定影响。Been 等[24]研究 197 例健康志愿者的颈椎侧位 X 线片,比较性别、年龄对颈椎曲度的影响,结果发现女性下颈椎曲度小于男性,未成年人下颈椎曲度大于成年人。Iorio 等[25]研究 118 例无症状成年志愿者不同年龄阶段颈椎曲度情况,发现年龄较大组的颈椎曲度大于年龄较小组。本研究将患者根据末次随访时 O-EA 角进行分组,结果显示各组年龄和性别构成比较差异均无统计学意义,可排除性别及年龄对下颈椎曲度的影响。对于枕颈固定节段对下颈椎曲度是否有影响,目前未见相关文献报道。对于不合并下颈椎不稳或脱位的患者,Pan 等[26]比较枕颈固定至 C2 和 C3 的效果发现,固定至 C2 能取得良好效果。本研究中部分患者 C2、3 融合畸形,因此将固定节段的长短以 C3 椎体为界,结果显示各组固定节段长度差异均无统计学意义,可排除固定节段对下颈椎曲度的影响。

另外,文献报道为预防合并寰枢前脱位患者枕颈融合术后出现吞咽困难并发症,O-EA 角最好固定在 100° 左右[8]。因此,本研究将 O-EA 角 95° 和 105° 作为界点,作为分组依据。

综上述,合并寰枢前脱位患者的 O-EA 角与 C2~7 Cobb 角成正相关,此类患者行枕颈融合术中 O-EA 角应避免过大,否则可能加速下颈椎退变。本研究不足在于测量 O-EA 角时部分患者外耳道显示不清,测量 T1 倾斜角时部分患者 T1 椎体上终板因肩部遮挡显示不清,只能调整图像对比度进行测量,可能存在一定误差。

作者贡献:陈太勇负责文献查阅、整理随访资料、数据收集及文章撰写;修鹏负责数据收集、文章逻辑梳理;杨曦负责研究结果总结和新问题的思考;宋跃明负责研究设计和文章修改。

利益冲突:所有作者声明,在课题研究和文章撰写过程中不存在利益冲突。

机构伦理问题:研究方案经四川大学华西医院生物医学伦理委员会批准[2019 年审(762)号]。

References

- 1.Garrido BJ, Sasso RC Occipitocervical fusion. Orthop Clin North Am. 2012;43(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.王鑫鑫, 王利民, 王卫东, 等 枕颈融合角度与颅颈交界区畸形患者下颈椎退变的关系. 中国组织工程研究. 2014;18(4):613–618. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2014-04-021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.孟阳, 刘浩, 戎鑫, 等 颅底凹陷症合并寰枢椎脱位患者枕颈角与下颈椎曲度的关系. 中国脊柱脊髓杂志. 2017;27(1):25–30. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-406X.2017.01.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsunaga S, Onishi T, Sakou T Significance of occipitoaxial angle in subaxial lesion after occipitocervical fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26(2):161–165. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.王圣林, 王超, Kirkham B. Wood, 等. 寰枢关节不稳或脱位患者上颈椎曲度改变对下颈椎的影响. 中国脊柱脊髓杂志. 2009;19(7):502–505. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-406X.2009.07.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shoda N, Takeshita K, Seichi A, et al Measurement of occipitocervical angle. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29(10):E204–208. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunakornsawat S, Pluemvitayaporn T, Pruttikul P, et al A new method for measurement of occipitocervical angle by occiput-C3 angle . Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2017;27(8):1051–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00590-016-1881-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen T, Yang X, Kong W, et al Impact of the occiput and external acoustic meatus to axis angle on dysphagia in patients suffering from anterior atlantoaxial subluxation after occipitocervical fusion. Spine J. 2019;19(8):1362–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morizane K, Takemoto M, Neo M, et al Occipital and external acoustic meatus to axis angle as a predictor of the oropharyngeal space in healthy volunteers: a novel parameter for craniocervical junction alignment. Spine J. 2018;18(5):811–817. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passias PG, Wang S, Kozanek M, et al Relationship between the alignment of the occipitoaxial and subaxial cervical spine in patients with congenital atlantoxial dislocations. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2013;26(1):15–21. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31823097f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng Y, Chen H, Lou J, et al Posterior distraction reduction and occipitocervical fixation for the treatment of basilar invagination and atlantoaxial dislocation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;140:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okada E, Matsumoto M, Ichihara D, et al Does the sagittal alignment of the cervical spine have an impact on disk degeneration? Minimum 10-year follow-up of asymptomatic volunteers. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(11):1644–1651. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1095-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazaki M, Hymanson HJ, Morishita Y, et al Kinematic analysis of the relationship between sagittal alignment and disc degeneration in the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(23):E870–876. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181839733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inada T, Furuya T, Kamiya K, et al Postoperative increase in occiput-C2 angle negatively impacts subaxial lordosis after occipito-upper cervical posterior fusion surgery. Asian Spine J. 2016;10(4):744–747. doi: 10.4184/asj.2016.10.4.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ames CP, Blondel B, Scheer JK, et al Cervical radiographical alignment: comprehensive assessment techniques and potential importance in cervical myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38(22 Suppl 1):S149–160. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a7f449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin S, Zhou F, Sun Y, et al The severity of operative invasion to the posterior muscular-ligament complex influences cervical sagittal balance after open-door laminoplasty. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(1):127–135. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3605-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hey HWD, Lau ET, Wong GC, et al Cervical alignment variations in different postures and predictors of normal cervical kyphosis: A new understanding. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42(21):1614–1621. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knott PT, Mardjetko SM, Techy F The use of the T1 sagittal angle in predicting overall sagittal balance of the spine . Spine J. 2010;10(11):994–998. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsubayashi Y, Shimizu T, Chikuda H, et al Correlations of cervical sagittal alignment before and after occipitocervical fusion. Global Spine J. 2016;6(4):362–369. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim B, Yoon DH, Ha Y, et al Relationship between T1 slope and loss of lordosis after laminoplasty in patients with cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament . Spine J. 2016;16(2):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim TH, Lee SY, Kim YC, et al T1 slope as a predictor of kyphotic alignment change after laminoplasty in patients with cervical myelopathy . Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38(16):E992–997. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182972e1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho JH, Ha JK, Kim DG, et al Does preoperative T1 slope affect radiological and functional outcomes after cervical laminoplasty? . Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39(26):E1575–1581. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jun HS, Chang IB, Song JH, et al Is it possible to evaluate the parameters of cervical sagittal alignment on cervical computed tomographic scans? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39(10):E630–636. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Been E, Shefi S, Soudack M Cervical lordosis: the effect of age and gender. Spine J. 2017;17(6):880–888. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iorio J, Lafage V, Lafage R, et al The effect of aging on cervical parameters in a normative north american population. Global Spine J. 2018;8(7):709–715. doi: 10.1177/2192568218765400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan J, Huang D, Hao D, et al Occipitocervical fusion: fix to C2 or C3? Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;127:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]