Abstract

Since the lockdown because of the pandemic, family members have been prohibited from visiting their loved ones in hospital. While it is clearly complicated to implement protocols for the admission of family members, we believe precise strategic goals are essential and operational guidance is needed on how to achieve them. Even during the pandemic, we consider it a priority to share strategies adapted to every local setting to allow family members to enter intensive care units and all the other hospital wards.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13054-021-03608-3.

Keywords: Professional/family relations, Social isolation, Health communication, Information dissemination, Family health, Intensive care units, Communicable diseases, Pandemics

Background

The pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), abruptly interrupted a decades-long path of "humanization" [1, 2] and "opening" of intensive care units (ICUs) [3, 4]. This is a precise need and clearly a right of patients and their families [5], establishing understanding and collaboration between families and the care team.

At the beginning of the pandemic, regulations were issued prohibiting family members from being physically close to their loved ones in hospital, mainly because of the scarcity of personal protective equipment (PPE) and limited knowledge about the disease and its transmission. These rules, which are still in force or are only slightly less restrictive a year later, are often perceived as unjust by people who have an understandable desire to be close to their loved ones, especially during the end-of-life stages [6, 7].

Many current regional provisions strictly restrict family visits. However, entry into hospitals is allowed in situations of “particular frailty and vulnerability of hospitalized patients” [8] or in any case “of special need” [9, 10], with strict limits on the time and number of visitors. The same conditions apply to pediatric wards and pediatric ICUs. It is left to the ward head to decide in which cases exceptions are appropriate.

The situation in corona virus disease (CoViD) wards remains extremely challenging. While we are aware of the complexity involved in implementing protocols for the admission of family members, we believe it is absolutely essential to set some precise strategic goals [11] and provide operational guidance on how to achieve them. Even during the pandemic, knowing that we cannot guarantee immediate results, we nevertheless consider it a priority to find shared strategies adaptable to every local setting to allow family members to enter CoViD wards [12].

The aim of the present paper is to share our viewpoint and experience about the benefits of permitting visits in ICUs during a pandemic period, to identify barriers to the relatives’ presence, and to discuss possible strategies to overcome them. The reasons leading our beliefs are presented in the Electronic Supplementary Material, together with a presentation of the Authors characteristics [Additional file 1].

Benefits for patients, relatives, and healthcare team

The therapeutic choices that guide the care of each patient, to be effective, respectful and proportionate, call for sharing between the patient, family members and health professionals [13], even in times of pandemic [14]. First and foremost, this implies appropriate communication by telephone or video calls [15], which are also possible towards the end of life [16]. These communication modalities, even if feasible, are not sufficient [17] and pose some objective difficulties, including respect for privacy and confidentiality [18]. The physical presence of family members makes it simpler to share care pathways: It permits more effective information [19], greater transparency and better understanding of decision-making processes, and makes sharing care choices more feasible.

Clinically speaking, the presence of family members offers relational benefits particularly at the end of the deep sedation phase and during prolonged non-invasive mechanical ventilation: it can significantly help reduce the prevalence of delirium [20], which is higher in CoViD patients than in other critically ill patients [21].

The presence of family members strongly motivates the patient to continue necessary but burdensome care. Even if limited in time and conditioned by the necessary PPE, it responds to a patient’s need, boosts the family members’ trust and appreciation of the care team [22], limits the understandable difficulty for family members to accept bad news, without actually having been able to verify directly what it implies in organizational and care terms to treat and care for critical patients.

The physical presence of family members helps protect them against “complicated grief.” Rarely in recent history conditions have arisen where it is impossible to be close to loved ones at their death. This custom is extremely ingrained worldwide [7]. The possibility of being physically close to one’s loved one even at the moment of death [23], if requested by family members, helps reduce the risk of psychological issues developing [24], which can persist for a long time.

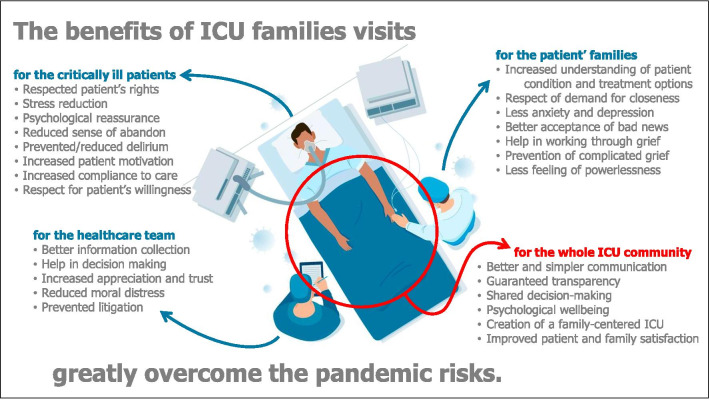

All the benefits linked to the families’ presence into the ICUs greatly outweigh the pandemic risks (Fig. 1), which can be controlled by specific protocols.

Fig. 1.

The physical presence of families into the ICU brings significant advantages for critically ill patients, for their families, and for the healthcare team

Tips for ICU opening

Family members should be allowed in even if only for short periods.

As has been stressed by European experts [6, 25], we must find new ways to keep up active and effective connections between the patient, the family, and the care team. These new strategies must preserve the quantity and quality of the relationship offered to patients and their family, responding to their needs for information and support. Compared to no visit, even short admissions are often of substantial significance to relatives and patients.

Visits to CoViD or non-CoViD ICUs, if properly conducted, do not pose any additional safety risk to patients or visitors [26]; once the visiting protocol has been established, the care team is responsible for its correct application, and for creating conditions "tailored" to the setting, to allow the safest visits.

-

(2)

Different rules should be set for CoViD and non-CoViD ICUs.

In general, simple protocols are needed, shared with the hospital management, to handle family members visiting patients. Relatives should be given clear, well-defined and unambiguous instructions, and their implementation should be carefully supervised.

In CoViD ICUs, family members must be protected with donning-and-doffing protocols, just like healthcare workers. In non-CoViD ICUs, additional health surveillance, appropriate physical protection, and rapid nasopharyngeal swabbing should be considered to protect inpatients from further SARS-CoV-2 illness.

-

(3)

If the total number of family visits must be limited, it is wise to encourage visits for those who can benefit most

There are phases of the disease in which it is more useful, from a clinical point of view, to have a loved one close by, for example during prolonged non-invasive ventilation or during respiratory weaning and the consequent easing of pharmacological sedation [21], and other phases where it is not so important for the patient—though not for the relatives—such as during prolonged deep sedation.

There are moments of hospital stay that are more important from the point of view of his or her biography, when the nearness of loved ones is of greater importance, such as the ICU admission, the communication to limit care, or the moments immediately preceding death [27]. Under these inevitably high-stress conditions, physical presence may be more effective in protecting families against psychological trauma.

If it should be necessary to limit the number of admissions for organizational reasons or because of a PPE shortage, it is wise to favor visits that, in the circumstances, can offer the greatest possible benefits to the largest number of both patients and visitors.

-

(4)

It is advisable to set up a special working group in the ICU and to re-evaluate at least monthly the structural and organizational conditions that justify limiting family visits.

The course of the pandemic gives rise to variable levels of hospital overload, with different workloads for operators, different availability of PPE, and different transmission rates at the entire population level. Some decisions to limit visits, which are necessary at certain times, may be inappropriate at others, either by excess or by default. Therefore, it may be useful to prepare different protocols from the outset, with different rules for visits, adapting them automatically, for instance by linking them to national/regional/local regulations.

-

(5)

Relatives and other visitors must be informed about the risks related to accessing CoViD areas.

Personal risk from contact with persons with CoViD can be minimized but will never be zero. All those requesting access to CoViD areas should be aware of the need to balance the possible risks of personal harm with the increased benefits expected from being present beside the patient. Family members and visitors must be fully informed about the risks involved in accessing areas intended for the care of patients with a contagious infectious disease. In this sense, hospital management might be consulted about whether to have visitors entering the CoViD area sign written informed consent.

-

(6)

The re-opening process should be shared with the whole team.

The conditions of "coming out from the pandemic"—hopefully in the next few months—calls for extra attention from an organizational perspective. All staff have experienced work and emotional overload [28] and have inevitably been affected by the changes in internal rules necessitated by isolation. Therefore, it is important that reopening the wards is a procedure shared as far as possible among staff members, since any significant change in the work environment risks increasing stress for healthcare workers [22, 29].

-

(7)

The physical presence of family members should not be limited to ICUs.

The decision to "open" should concern the ICUs together with all the other hospital wards, whose work always precedes or follows that of treating the most critical and complex phase of the disease. This good clinical practice may be harder to manage in settings with fewer doctors and nurses than the ICUs. However, it is advisable to make comprehensive hospital rules to govern the presence of visitors, aiming to restart the process of patient—and family-centered care, even—and especially—during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [30].

How to proceed to opening

The indispensable conditions for visitors to enter the hospital are:

The family member and the patient want it.

The family member is not in fiduciary home isolation or quarantine, unless ad hoc protocols are in place for these cases, which should in any case be reserved for exceptional times.

The family member is asymptomatic and has no risk factors for contagious diseases. Enough PPE is available for the family members.

The presence of trained persons (healthcare workers or hospital volunteers) is guaranteed, with the task of indicating internal routes, explaining clearly and in an easily understandable way to non-healthcare professionals how to use the PPE properly, and supervising their correct use.

Given these conditions, we believe the following rules must be applied:

Use rigorous, agreed procedures to differentiate entry and exit routes, to ensure adequate scheduling, interpersonal distancing, hand washing, and the obligation to wear PPE. When properly implemented, these measures ensure more than adequate safety for patients about the risk of infection due to family visits [31] and protect family members from infection [32].

Arrange for clinical monitoring: body temperature when the visitor enters the hospital, checking for the absence of flu-like symptoms and other risk factors by completing targeted questionnaires. Optional infectious surveillance with rapid antigenic tests could give an answer within minutes and are not too expensive.

Schedule visits so that people do not linger in waiting rooms and avoid too many relatives together at the same time. Limit the number of relatives/visitors for each patient and—if it is not feasible to organize a daily visit—consider the possibility of guaranteeing visits by family members at least once or twice a week. This should make it possible to escape from the image of the "closed" hospital, even for non-CoViD patients, which nowadays appears frankly unacceptable [14].

Permit exceptions in circumstances where it is particularly important to allow family members to visit the patient, such as during prolonged hospitalization, in cases of inauspicious short-term prognosis [33], and in all cases of particular patient frailty.

From the organizational point of view, each health facility can organize the pathways to opening as it deems most appropriate and sustainable, modifying internal rules based on continuous monitoring of their effectiveness, with the aim of the earliest possible restoration of good clinical practices of family-centered medicine [13, 14]. Table 1 lists the clinical, cultural, and logistic barriers, with strategies to overcome them.

Table 1.

The barriers likely to hinder the family presence in the ICU can be overcome by specific strategies

| Barriers to ICU visits | Strategies for implementation | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Risk of the relatives’ infection when entering CoViD-19 ICUs | Adequate donning and doffing protocols |

| Risk of patients’ infection in COVID-free critically ill patients | Screening of family members and visitors before visit | |

| Inadequate or incomplete PPE employment | Clear instructions and supervision | |

| Physical discomfort of the visiting family member | Preventive instructions and staff availability | |

| Cultural | Family visits are not a priority for the staff | ICU staff debriefing on family needs and requests |

| Lack of motivation and fatigue of staff members | Adequate staff knowledge regarding opening benefits | |

| Fear of other opportunistic infections brought by families | Literature evidence demonstrating this is not an issue | |

| Concern of legal consequences in case of visitors’ infection | Informed consent gaining prior to visit | |

| Logistical | Shortage of PPE | If persisting, visits are NOT permitted |

| Limited staff availability, time constraints | Extra staff, skilled volunteers | |

| Lack of protocols/rules | Drafting of hospital/regional shared protocols | |

| Suboptimal/inadequate space due to surge of ICU admission | Temporary restriction on opening hours and number of visitors |

Generalizability of the present approach

Even if the present paper is based on an Italian setting, the contents are intended to be generalizable. First, the human need for closeness and sharing has been described as scientifically not different among countries [34, 35]. Moreover, the experiences and scenarios used here are from the cultural Italian milieu [4], where the concept of open ICU is much less common than in Northern Europe or North America.

All the contents here presented will be reassessed through a Delphi process as soon as possible, led by the Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Reanimation, and Intensive Care Medicine (SIAARTI) and involving a multi-professional taskforce from several Italian scientific societies.

Conclusions

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has unfortunately made it necessary to restrict or prohibit access to hospitals for patients’ relatives. There is ample awareness in the healthcare world of how much suffering these decisions, while necessary, have caused in all those involved: patients and family in the first place, but also doctors and nurses.

Current knowledge and the guaranteed availability of PPE allow us to favor a careful, progressive resumption of opening to family visits, always in full respect of the patient’s wishes. We believe there are no substantial reasons why family members should not be allowed in the CoViD wards: It may be not only useful, but even necessary. In the specific setting of each hospital, all possibilities should be explored to promptly restore good "humanizing" practices in both intensive and non-intensive care units.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Presentation of the social, relational, and organizational challenges due to the pandemic, together with a description of the Authors’ group.

Acknowledgements

All the authors are very grateful to the physicians, nurses, and health care personnel who are working with passion and competence in the CoViD-19 hospitals. This paper endorses the H.E.R.O.I.C. bundle (www.heroicbundle.org). Figure 1 is designed using resources from www.freepik.com. The authors acknowledge the APC found of University of Milan and the Società Italiana di Anestesia, Analgesia, Rianimazione e Terapia Intensiva (SIAARTI) for the Open Access support. The authors are grateful to J.D. Baggott for language editing.

Authors’ contributions

GM, GGrist, EC, and MV conceived and designed the present viewpoint. GM, AGiann, GGrist, PM, DM, MV, LR, and FP thoroughly discussed the structure and selected the contents of the paper. GM wrote the first draft. PM, DM, GGrass, and MC provided regional regulations and examples on how to apply them. GM, AGiann, GGrist, AGalaz, IG, MV, LR, FP wrote the first version of the figure, table and “tips.” LR, GGrass, SS, FP presented the manuscript to the steering committees of the scientific societies. AGiann, EC, AGalaz, IG, VZ, GGrass, MC, and FP revised the draft for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final version and submission of the manuscript to Critical Care.

Funding

This viewpoint did not receive any grant and was done with departmental funding only.

Availability of supporting data

Not applicable.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Giovanni Mistraletti, Email: giovanni.mistraletti@unimi.it.

Alberto Giannini, Email: alberto.giannini@asst-spedalicivili.it.

Giuseppe Gristina, Email: geigris@fastwebnet.it.

Paolo Malacarne, Email: pmalacarne@hotmail.com.

Davide Mazzon, Email: dvmazzon@gmail.com.

Elisabetta Cerutti, Email: elisabetta.cerutti@ospedaliriuniti.marche.it.

Alessandro Galazzi, Email: alessandro.galazzi@policlinico.mi.it.

Ilaria Giubbilo, Email: giubbilo.ilaria@gmail.com.

Marco Vergano, Email: marco.vergano@aslcittaditorino.it.

Vladimiro Zagrebelsky, Email: v.zagrebelsky@gmail.com.

Luigi Riccioni, Email: luigiriccioni@yahoo.it.

Giacomo Grasselli, Email: giacomo.grasselli@unimi.it.

Silvia Scelsi, Email: silvia.scelsi12@gmail.com.

Maurizio Cecconi, Email: maurizio.cecconi@hunimed.eu.

Flavia Petrini, Email: flavia.petrini@siaarti.it.

References

- 1.Mistraletti G, Giannini A, Antonelli M. Un progetto SIAARTI per migliorare la comunicazione con i familiari in Terapia Intensiva. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013;79(Suppl. 1 al No. 10):49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mistraletti G, Mezzetti A, Anania S, Ionescu Maddalena A, Del Negro S, Giusti GD, Gili A, Iacobone E, Pulitano SM, Conti G, et al. Improving communication toward ICU families to facilitate understanding and reduce stress. Protocol for a multicenter randomized and controlled Italian study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;86:105847. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.105847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannini A. Open intensive care units: the case in favour. Minerva Anestesiol. 2007;73(5):299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giannini A, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Latour JM. What’s new in ICU visiting policies: can we continue to keep the doors closed? Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(5):730–733. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3267-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comitato Nazionale per la Bioetica - Terapia intensiva "aperta" alle visite dei familiari. http://bioetica.governo.it/it/pareri/pareri-e-risposte/terapiaintensiva-aperta-alle-visite-dei-familiari/. Accessed 25 May 2021.

- 6.Azoulay E, Kentish-Barnes N. A 5-point strategy for improved connection with relatives of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):e52. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30223-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakam GK, Montgomery JR, Biesterveld BE, Brown CS. Not dying alone—modern compassionate care in the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):e88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2007781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osservatorio-Nazionale-Autismo: Indicazioni ad interim per un appropriato sostegno delle persone nello spettro autistico e/o con disabilità intellettiva nell’attuale scenario emergenziale SARS-CoV-2. Roma: Istituto Superiore di Sanità; 2020.

- 9.Presidente della Giunta Regionale della Toscana - Ordinanza n. 96 del 26-10-2020 (par. 9).

- 10.Giunta Regionale del Veneto - Circolare N.466241 del 02-11-2020

- 11.Comitato Nazionale per la Bioetica - La solitudine dei malati nelle strutture sanitarie in tempo di pandemia. http://bioetica.governo.it/it/pareri/mozioni/la-solitudine-dei-malati-nelle-strutture-sanitarie-in-tempi-di-pandemia/. Accessed 25 May 2021.

- 12.Kentish-Barnes N, Degos P, Viau C, Pochard F, Azoulay E. It was a nightmare until I saw my wife": the importance of family presence for patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):103–128. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart JL, Turnbull AE, Oppenheim IM, Courtright KR. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 era. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e93–e97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mistraletti G, Gristina G, Mascarin S, Iacobone E, Giubbilo I, Bonfanti S, Fiocca F, Fullin G, Fuselli E, Bocci MG, et al. How to communicate with families living in complete isolation. BMJ Support Palliative Care. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galazzi A, Brioni M, Mistraletti G, Roselli P, Abbruzzese C. End of life in the time of COVID-19: the last farewell by video call. Minerva Anestesiol. 2020;86(11):1254–1255. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.20.14906-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galazzi A, Binda F, Gambazza S, Lusignani M, Grasselli G, Laquintana D. Video calls at end of life are feasible but not enough: a 1-year intensive care unit experience during the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic. Nurs Critical Care. 2021 doi: 10.1111/nicc.12647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nittari G, Khuman R, Baldoni S, Pallotta G, Battineni G, Sirignano A, Amenta F, Ricci G. Telemedicine practice: review of the current ethical and legal challenges. Telemed J e-health: Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2020;26(12):1427–1437. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuevas E. No visitors allowed. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(4):381–382. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, Thompson JL, Aldrich JM, Barr J, Byrum D, Carson SS, Devlin JW, Engel HJ, et al. Caring for critically Ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle: results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in over 15,000 adults. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):3–14. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotfis K, Williams Roberson S, Wilson JE, Dabrowski W, Pun BT, Ely EW. COVID-19: ICU delirium management during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02882-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giannini A, Miccinesi G, Prandi E, Buzzoni C, Borreani C, Group OS. Partial liberalization of visiting policies and ICU staff: a before-and-after study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(12):2180–2187. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris SE, Moment A, Thomas JD. Caring for bereaved family members during the COVID-19 pandemic: before and after the death of a patient. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e70–e74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downar J, Kekewich M. Improving family access to dying patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azoulay E, Curtis JR, Kentish-Barnes N. Ten reasons for focusing on the care we provide for family members of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2020;47:230–233. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06319-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu M, Cheng SZ, Xu KW, Yang Y, Zhu QT, Zhang H, Yang DY, Cheng SY, Xiao H, Wang JW, et al. Use of personal protective equipment against coronavirus disease 2019 by healthcare professionals in Wuhan, China: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2195. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fusi-Schmidhauser T, Preston NJ, Keller N, Gamondi C. Conservative management of COVID-19 patients-emergency palliative care in action. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e27–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benfante A, Di Tella M, Romeo A, Castelli L. Traumatic stress in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the immediate impact. Front Psychol. 2020;11:569935. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.569935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavoie-Tremblay M, Bonin JP, Lesage AD, Bonneville-Roussy A, Lavigne GL, Laroche D. Contribution of the psychosocial work environment to psychological distress among health care professionals before and during a major organizational change. Health Prog. 2010;29(4):293–304. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0b013e3181fa022e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munshi L, Evans G, Razak F. The case for relaxing no-visitor policies in hospitals during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. CMAJ. 2020;193:E135–E137. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schunemann HJ. authors C-SURGEs: physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruppo di Lavoro ISS - Prevenzione e controllo delle Infezioni: Indicazioni ad interim per la prevenzione e il controllo dell’infezione da SARS-CoV-2 in strutture residenziali sociosanitarie e socioassistenziali. In: Vol. 4/2020 Rev.2. Roma: Istituto Superiore di Sanità; 2020.

- 33.Ramos HCHN, Henry L. No one should die alone on our watch. Int J Care Caring. 2020;4(4):595–598. doi: 10.1332/239788220X15989008009811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biancofiore G, Bindi ML, Romanelli AM, Urbani L, Mosca F, Filipponi F. Stress-inducing factors in ICUs: what liver transplant recipients experience and what caregivers perceive. Liver Transpl. 2005;11(8):967–972. doi: 10.1002/lt.20515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson JE, Meier DE, Oei EJ, Nierman DM, Senzel RS, Manfredi PL, Davis SM, Morrison RS. Self-reported symptom experience of critically ill cancer patients receiving intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2):277–282. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Presentation of the social, relational, and organizational challenges due to the pandemic, together with a description of the Authors’ group.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.