Summary

Background

Lifestyle interventions can delay the onset of type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance, but whether this leads subsequently to fewer complications or to increased longevity is uncertain. We aimed to assess the long-term effects of lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance on the incidence of diabetes, its complications, and mortality.

Methods

The original study was a cluster randomised trial, started in 1986, in which 33 clinics in Da Qing, China, were randomly assigned to either be a control clinic or provide one of three interventions (diet, exercise, or diet plus exercise) for 6 years for 577 adults with impaired glucose tolerance who usually receive their medical care from the clinics. Subsequently, participants were followed for up to 30 years to assess the effects of intervention on the incidence of diabetes, cardiovascular disease events, composite microvascular complications, cardiovascular disease death, all-cause mortality, and life expectancy.

Findings

Of the 577 participants, 438 were assigned to an intervention group and 138 to the control group (one refused baseline examination). After 30 years of follow-up, 540 (94%) of 576 participants were assessed for outcomes (135 in the control group, 405 in the intervention group). During the 30-year follow-up, compared with control, the combined intervention group had a median delay in diabetes onset of 3.96 years (95% CI 1.25 to 6.67; p=0.0042), fewer cardiovascular disease events (hazard ratio 0.74, 95% CI 0.59–0.92; p=0.0060), a lower incidence of microvascular complications (0.65, 0.45–0.95; p=0.025), fewer cardiovascular disease deaths (0.67, 0.48–0.94; p=0.022), fewer all-cause deaths (0.74, 0.61–0.89; p=0.0015), and an average increase in life expectancy of 1.44 years (95% CI 0.20–2.68; p=0.023).

Interpretation

Lifestyle intervention in people with impaired glucose tolerance delayed the onset of type 2 diabetes and reduced the incidence of cardiovascular events, microvascular complications, and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and increased life expectancy. These findings provide strong justification to continue to implement and expand the use of such interventions to curb the global epidemic of type 2 diabetes and its consequences.

Introduction

A major epidemic of diabetes has occurred during the past 20 years, with the worldwide prevalence of the condition rising from 150 million cases in 2000 to an estimated 425 million in 2017, projected to increase to 629 million by 2045.1 This epidemic is currently estimated to result in about 4 million excess deaths each year. The excess mortality is mainly due to high rates of cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and infection that develop over time in patients with type 2 diabetes.2 By the mid-1980s, obesity and physical inactivity had been established as major modifiable risk factors for type 2 diabetes, and people with impaired glucose tolerance were shown to be at high risk of developing the disease.3,4 Randomised trials were then initiated to assess if lifestyle interventions could delay onset or prevent diabetes in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance.

The Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study,5 which began in 1986, was the first such trial, and showed an overall 51% reduction in diabetes incidence in participants after a 6-year intervention with diet, exercise, or both. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study6 followed in 1993, and the US Diabetes Prevention Program7 in 1999, both showing a 58% reduction in type 2 diabetes incidence after about 3 years of lifestyle intervention. Reports from India8 and Japan9,10 also documented a reduced incidence of type 2 diabetes from lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study,11 which followed up participants from the original Da Qing Diabetes Prevention study, and the follow-up studies of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study12 and the Diabetes Prevention Program13 showed that the reduction in diabetes incidence remained for several years after the period of active intervention.

Complications that cause most of the excess morbidity and mortality in diabetes occur mainly in people who have had diabetes for 20–30 years. As a result, only long-term follow-up studies can answer the crucial question of whether lifestyle or other interventions that delay diabetes onset can subsequently reduce serious complications and attributable mortality. Despite clear evidence that lifestyle interventions can reduce diabetes incidence, the findings of the 13-year follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study14 and the 15-year follow-up of the Diabetes Prevention Program15 cast doubt on the ability of lifestyle interventions to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular and microvascular complications. We have previously reported results from the 20-year11,16 and 23-year17 follow-up analyses of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcomes Study, which showed reductions in the incidence of retinopathy and in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality among participants who had received lifestyle interventions. Here, we report the findings from the 30-year follow-up of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcomes Study, which was designed to document the longer-term effects of lifestyle intervention in people with impaired glucose tolerance on diabetes incidence, cardiovascular events, microvascular complications, and life expectancy.

Methods

Study design and participants

The design and methods used in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study and subsequent 20-year and 23-year follow-up studies have been reported previously.5,11,17 The Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study was a cluster-randomised clinical trial to test if lifestyle modification could delay or prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes among Chinese adults with impaired glucose tolerance. In 1986, 33 primary care clinics in Da Qing, China, screened 110 660 adults and, by use of 75 g oral glucose tolerance tests, identified 577 people aged 25–74 years with impaired glucose tolerance.5 The clinics were then randomly assigned to clusters to provide one of three interventions (diet, exercise, or diet plus exercise) or to serve as a control. Each clinic provided the assigned intervention to enrolled participants who received health care at that clinic. The dietary intervention aimed to increase vegetable intake and reduce alcohol and sugar intake and the exercise intervention aimed to increase leisure-time physical activity. Participants in each of the intervention groups who were overweight or obese were encouraged to reduce calorie intake to lose bodyweight. The control clinics provided standard care to participants. Active intervention took place for 6 years, after which participants were informed of the trial results and subsequently received routine medical care from their usual providers.

Here we report the 30-year results of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcomes Study, an observational study of Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study participants who were followed up for up to 30 years after randomisation, to compare long-term outcomes related to diabetes between participants exposed to lifestyle interventions and those in the control group. Because no significant differences were found in diabetes incidence among the three intervention groups during the trial,5 these groups were combined for the follow-up study to increase the power to detect differences in outcomes between lifestyle intervention and control.

Outcome events were ascertained in 2006, 2009, and 2016. Investigators who assessed the outcomes were masked to study group allocation. Participants and other investigators were not masked to group allocation.

Institutional review boards at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and Fuwai Hospital approved the study. All study participants, or proxies who served as informants for the deceased, provided written informed consent.

Procedures

For the 30-year follow-up analysis, we determined the vital status of participants on Dec 31, 2016. For the deceased, proxy informants such as a living spouse, sibling, or child, were interviewed with use of standardised questionnaires, and the data were then verified by review of medical records, death certificates, or both. For living participants, data were collected by interview, clinical examination, and medical record review by trained staff and physicians in Da Qing First Hospital (Da Qing, China). In 2016, among the 279 living participants, 24 (8.6%) were unable to go to the hospital because of ill-health and were examined at home, and 31 (11.1%) living outside Da Qing were interviewed by telephone and examined in local hospitals.

Outcomes

The four primary outcomes of interest, as predefined in the study protocol for the 30-year follow-up analysis (appendix), were cardiovascular disease events, a composite of microvascular complications, cardiovascular deaths, and life expectancy. Secondary outcomes were stroke, coronary heart disease, hospital admission for heart failure, updated information on the incidence of diabetes, and the individual microvascular complications of retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. Additional secondary outcomes, including quality of life, cognitive function, osteoporosis, and other physical disabilities, will be reported elsewhere. Diabetes was defined by 1985 WHO criteria18 from results of 75 g oral glucose tolerance tests done every 2 years during the trial (1986–92) and in 2006 or 2016 at the follow-up examinations, or from self-reported physician-diagnosed diabetes, and evidence of increased blood or plasma glucose concentrations or use of glucose-lowering medication in medical records. Participants who were not already known to have diabetes underwent an oral glucose tolerance test, also interpreted by use of 1985 WHO criteria. Primary cardiovascular disease outcome events were defined as non-fatal or fatal myocardial infraction or sudden death, hospital admission for heart failure, or non-fatal or fatal stroke. Cardiovascular deaths were defined as deaths due to myocardial infarction, sudden death, heart failure, or stroke. Secondary cardiovascular disease outcome events were coronary heart disease, defined as non-fatal or fatal myocardial infarction or sudden death; hospital admission for heart failure; and non-fatal or fatal stroke. The primary outcome of composite microvascular disease was an aggregate outcome of retinopathy, defined as a history of photocoagulation, blindness from retinal disease, or proliferative retinopathy; nephropathy, defined as a history of end-stage renal disease, renal dialysis, renal transplantation, or death from chronic kidney disease; and neuropathy, defined as a history of leg, ankle, or foot ulceration, gangrene, or amputation. The secondary microvascular outcomes were retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy, each individually defined in the same way as in the primary composite outcome. Definitions for the microvascular outcomes used in this analysis were modified from those used in previous reports from the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcomes Study11,16,17 to minimise bias due to competing mortality (appendix). Causes of death were determined from review of medical records and death certificates. For each outcome, onset was defined as the earliest date of recognition of the outcome from medical records, interview, or the 20-year and 30-year follow-up examinations. Two physicians (QG and JW), unaware of participants’ trial assignments, independently adjudicated outcomes, with disagreements resolved by a third senior physician (HL).

Statistical analysis

Although this follow-up analysis is an observational study, the primary and secondary outcomes were analysed in accordance with intention-to-treat principles. The analyses were based on the original 1986 group assignment of each participant, regardless of whether or not they completed the original trial. We calculated incidence as number of events divided by person-years of exposure censored at date of recognition of the event, loss to follow-up, death, or Dec 31, 2016, whichever came first. Time-to-first-event survival curves for each outcome were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared between groups with log-rank tests. Cox proportional-hazards analyses, accounting for clinic assignment, were used to calculate hazard ratios to quantify between-group differences.

We calculated differences between the intervention and control groups in average number of event-free years and life expectancy from areas under the survival curves as a summation of yearly discrete survival function, and we calculated life-years gained as the group difference in mean life expectancy. We fitted a parametric model with Weibull distribution to extrapolate the median survival time. Median delay in onset of events and numbers needed to treat to prevent an event during follow-up were estimated from survival functions. We then used a Cox proportional-hazards analysis to determine if group differences in primary outcomes could be attributed to delay in the onset of diabetes. We also explored changes in BMI and differences related to smoking and sex as potential explanatory variables associated with differences in primary outcomes between intervention and control groups.

Differences were considered significant if p was less than 0.05 in two-sided tests.

We used SAS/STAT (version 14.3) for all statistical analyses.

Role of the funding source

Investigators from the organisations that funded the study were involved in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

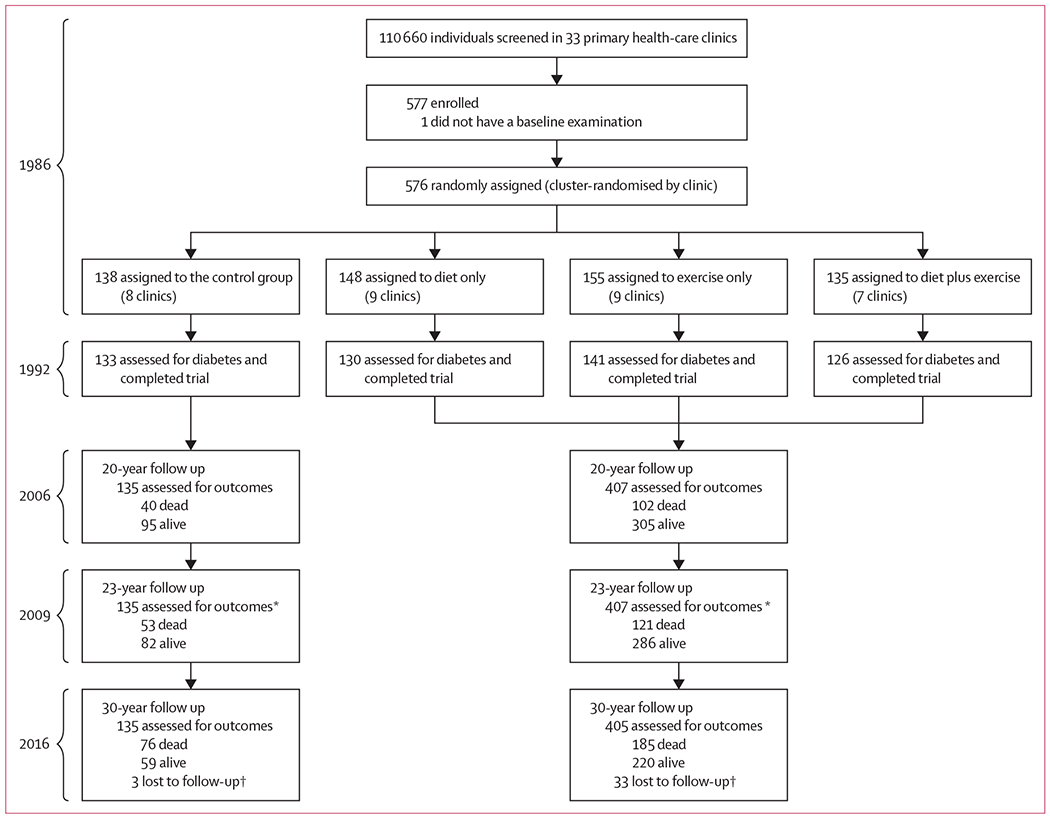

Of the original 577 study participants in 1986, one declined the baseline examination, 138 were assigned to the control group and 438 to one of three intervention groups. In 2016, 36 participants had been lost to follow-up (three in the control group and 33 in the combined intervention group) and 540 (94%) were assessed for outcomes (figure 1). The characteristics of participants at baseline and 30-year follow-up are shown in table 1.

Figure 1: Study profile.

After the original trial ended, all participants subsequently received routine medical care from their usual clinics and providers. *In 2009, review of death certificates and medical records only; no examinations were done. †Most loss to follow-up (31 of 36) occurred between 1986 and 1992, during the trial, when some participants were relocated to a newly discovered oil field and could no longer receive intervention or follow-up at their assigned clinics in Da Qing; in 2016, data were obtained for some participants who earlier had been reported as lost to follow-up.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the control and combined intervention groups at baseline (1986) and at 30-year follow-up (2016)

| Control group (n=138) |

Intervention group (n=438) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (1986) | ||

| Age (years) | 46.6 (9.3) | 44.7 (9.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 79 (57%) | 233 (53%) |

| Women | 59 (43%) | 205 (47%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.2 (3.8) | 25.6 (4.0) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 133.4 (26.0) | 131.9 (24.3) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 87.8 (15.4) | 87.0 (14.1) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.2 (1.1) | 5.0 (1.4) |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 5.5 (0.8) | 5.6 (0.8) |

| 2-h plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 9.0 (0.9) | 9.0 (0.9) |

| Current smoker | 69 (50%) | 169 (39%) |

| 30-year follow-up (2016) | ||

| Participants lost to follow-up | 3 (2%) | 33 (8%) |

| Participants dead | 76 (55%) | 185 (42%) |

| Participants alive | 59 (43%) | 220 (50%) |

| Age (years) | 71.8 (6.9) | 70.5 (6.6) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 25 (42%) | 86 (39%) |

| Female | 34 (58%) | 134 (61%) |

| Participants examined | 48 (81%) | 183 (83%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.7 (3.9) | 24.5 (3.3) |

| Change in BMI from 1986 to 2016 (kg/m2) | −1.1 (3.4) | 1.2 (3.3) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 143.9 (19.3) | 148.1 (21.2) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 74.2 (7.4) | 77.6 (10.4) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.9 (0.9) | 5.0 (1.4) |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 7.8 (2.8) | 7.4 (2.9) |

| 2-h plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 11.8 (3.5) | 10.1 (3.5) |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 61.6 (17.6) | 60.9 (18.3) |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.8 (1.6) | 7.7 (1.7) |

| Data are n (%) or mean (SD). | ||

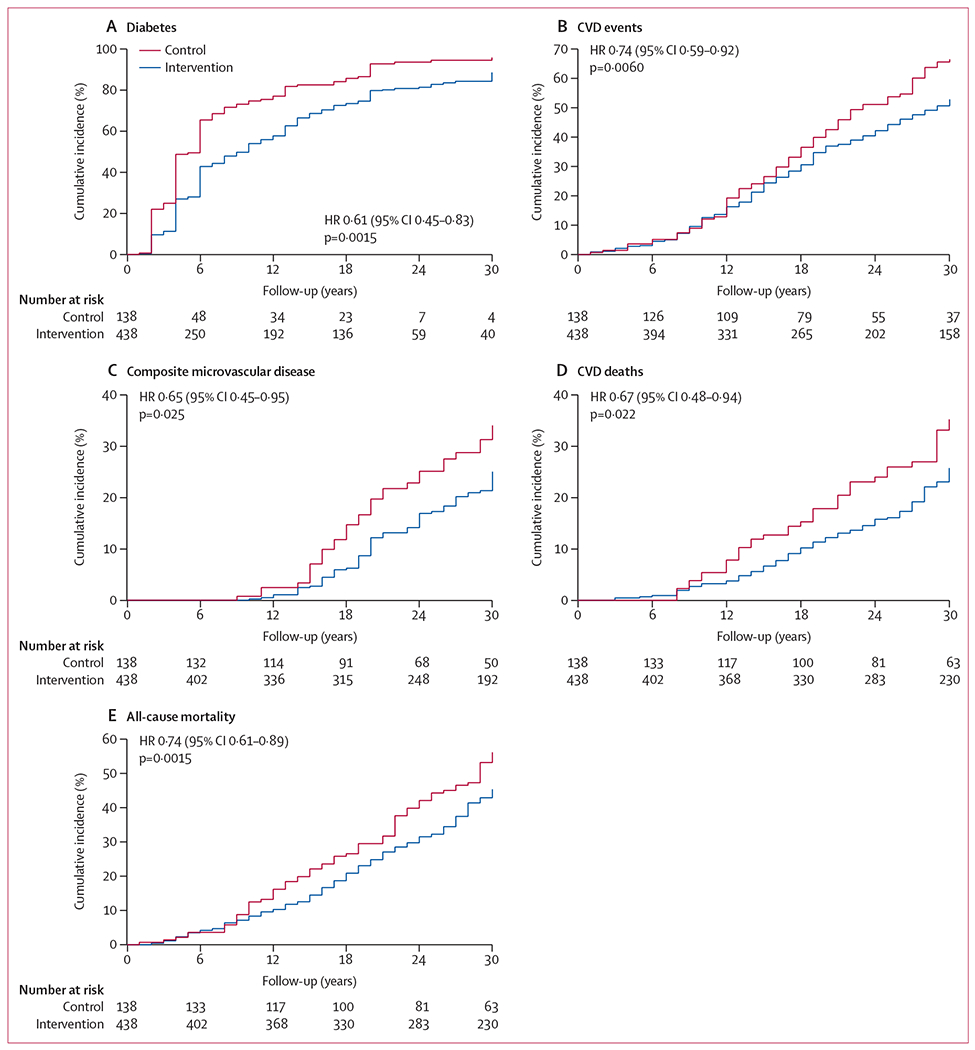

A median delay in diabetes onset of 3.96 years (95% CI 1.25–6.67; p=0.0042) was seen in the intervention group and a lower cumulative incidence of diabetes compared with that of the control group persisted during follow-up (figure 2A). Findings were similar for men and women (appendix).

Figure 2: Kaplan–Meier plots of cumulative incidence of diabetes (A), cardiovascular disease events (B), composite microvascular disease (C), cardiovascular disease deaths (D), and all-cause mortality (E) during the 30-year follow-up.

Diabetes was defined by use of an oral glucose tolerance test done every 2 years during the trial (1986–92) and in 2006 or 2016 at the follow-up examinations, or from self-reported physician-diagnosed diabetes, or evidence of increased plasma glucose concentrations in the medical record or of the participant receiving glucose-lowering medications. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) events were defined as non-fatal or fatal myocardial infarction or sudden death, hospital admission for heart failure, or non-fatal or fatal stroke. Composite microvascular disease was defined as an aggregate outcome of retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. CVD deaths were defined as death due to myocardial infarction, sudden death, heart failure, or stroke. HR=hazard ratio (intervention vs control); p values derived from Cox proportional-hazards models, controlled for clinic randomisation.

Cardiovascular disease events were recorded in 195 (48%) of 405 participants in the intervention group, with a cumulative incidence of 52.9% (95% CI 47.5–57.9), and in 80 (59%) of 135 in the control group, with a cumulative incidence of 66.5% (57.0–74.4; appendix), resulting in 26% (8–41, p=0.0060) fewer events in the intervention group than in the control group (figure 2B). Regarding secondary cardiovascular disease outcomes, the incidence of stroke was 25% lower (95% CI 4–41, p=0.024) in the intervention group than in the control group; incidences of coronary heart disease and hospital admission due to heart failure were also numerically lower, but not significantly so (incidence was 27% lower for coronary heart disease [95% CI −4 to 49; p=0.079], and 29% lower for heart failure [−4 to 52, p=0.081]; appendix).

Although cardiovascular disease events were more frequent in men, the rate reduction associated with intervention was lower in men (20%, 95% CI −6 to 40) than in women (31%, 8 to 49; appendix). A median delay of 4.64 years (95% CI 1.05-8.22, p=0.011) in cardiovascular disease onset was seen in the intervention group, and the number needed to treat to prevent one cardiovascular disease event during the 30-year interval was nine (95% CI five to 36; table 2).

Table 2:

Effect of intervention on delaying the onset of primary outcomes, event-free years gained, and numbers needed to treat during the 30-year follow-up

| Median delay, years (95% CI) | Mean number of event-free years (95% CI) | Number needed to treat (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 3.96 (1.25 to 6.67; p=0.0042) | 4.07 (1.46 to 6.68; p=0.0022) | 10 (7 to 23) |

| CVD events | 4.64 (1.05 to 8.22; p=0.011) | 1.77 (0.18 to 3.36; p=0.029) | 9 (5 to 36) |

| Composite microvascular disease outcome | 5.17 (−056 to 10.90; p=0.077) | 0.96 (−0.12 to 2.03; p=0.080) | 10 (5 to 193) |

| CVD deaths | 7.25 (−0.18 to 14.67; p=0.056) | 1.06 (0.10 to 2.23; p=0.074) | 10 (5 to 72) |

| All-cause mortality | 4.82 (1.48 to 8.15; p=0.0047) | 1.44 (0.20 to 2.68; p=0.023)* | 10 (6 to 25) |

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) events were defined as non-fatal or fatal myocardial infarction or sudden death, hospital admission due to heart failure, or non-fatal or fatal stroke. Composite microvascular disease was defined as an aggregate of retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. CVD deaths were defined as death due to myocardial infarction, sudden death, heart failure, or stroke.

Mean increase in life-expectancy.

The incidence of composite microvascular disease was 35% lower (95% CI 5–55, p=0.025) in the invention group than in the control group (figure 2C), with a cumulative incidence of 25.1% (20.2–30.1) in the intervention group and 34.0% (24.5–43.8) in the control group (appendix). The incidence of retinopathy was 40% lower (95% CI 5–62, p=0.032) in the intervention group than in the control group; incidences of nephropathy and neuropathy were also numerically lower, but not significantly so (appendix).

Vital status data were ascertained in 540 (93.8%) of 576 original participants. The date and cause of death were determined in 185 (45.7%) of 405 particpants in the intervention group and 76 (56.3%) of 135 in the control group (appendix). Half of all deaths were attributed to cardiovascular disease; half of these cardiovascular deaths were due to stroke. The cumulative incidence of cardiovascular death was 25.6% (95% CI 21.1–30.4) in the intervention group and 35.2% (26.4–44.2) in the control group (reduction of 33%, 95% CI 6–52, p=0.022); the intervention group also had lower death rates from stroke (24% lower [−34 to 56, p=0.35]), coronary heart disease (40% [−15 to 69, p=0.12]), and heart failure (40% [−37 to 74, p=0.23]; appendix). Although cardiovascular deaths were more frequent in men, the rate reductions were greater in women than in men (appendix). For non-cardiovascular deaths, we identified no significant differences between the intervention and control groups (appendix).

All-cause deaths were 26% lower (95% CI 11–39, p=0.0015) in the intervention group than in the control group (figure 2E, appendix), with significant reductions in women (41%, 95% CI 9 to 62; p=0.018), but not in men (15%, 95% CI −9 to 34; p=0.19; appendix). The intervention was associated with an increase in median survival, and mean overall survival was longer in the intervention group than in the control group (table 2). The number needed to treat with lifestyle interventions to prevent one death during the 30-year interval was ten (95% CI six to 25, p=0.0015).

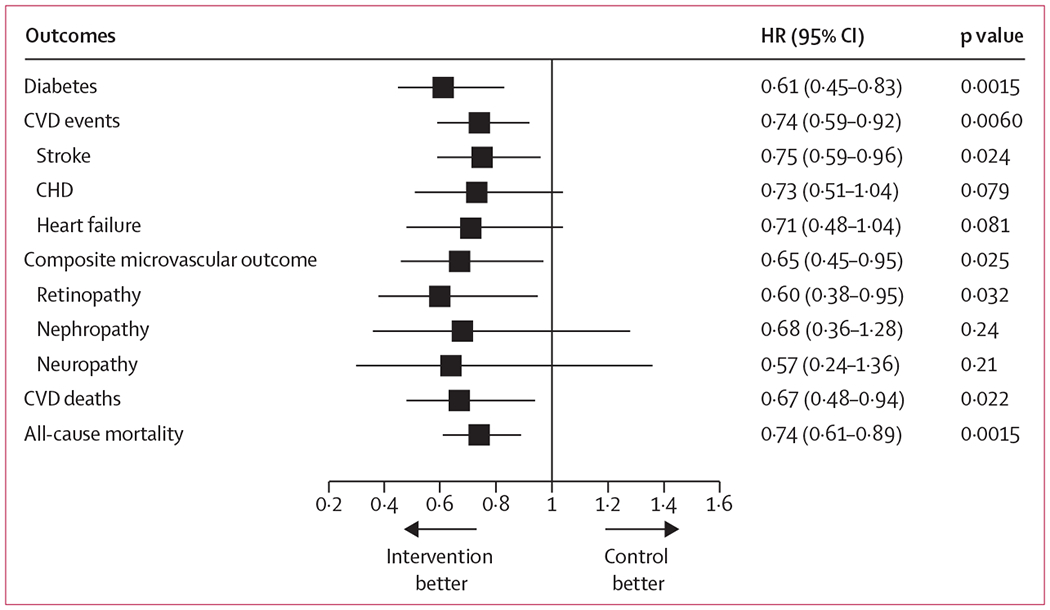

We identified significant reductions in the incidence of all primary outcome events in the intervention group (figure 3). A secondary analysis in multivariable models showed that correcting for time of onset of diabetes nullified the significance of the intervention effect for each of the primary outcomes (appendix), suggesting that much of their reduced incidence can be accounted for by the delay in diabetes onset in the intervention group. Further exploratory analyses showed that the effect of the intervention in reducing diabetes incidence in men and women were similar, but the reductions in subsequent mortality and vascular complications were less in men than in women. The higher rates of smoking in men might account for some of the sex difference in response to the intervention, although the intervention-related reductions in all of the primary outcomes among all participants remained significant after adjustment for smoking (appendix). The three original trial intervention subgroups each showed similar reductions in the primary outcome events but, individually, these reductions were not all significant (appendix).

Figure 3: Forest plot of primary and secondary outcome events at 30-year follow-up.

The reference category is the control group. Hazard ratios (HRs) are derived from proportional-hazards models, controlled for clinic randomisation. CVD=cardiovascular disease. CHD=coronary heart disease.

Discussion

On the basis of data gathered from the 20-year and 23-year follow-up analyses of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcomes Study,11,16,17 we have previously reported reduced diabetes incidence and significant reductions in the incidence of retinopathy, cardiovascular disease deaths, and all-cause mortality in the combined lifestyle intervention group compared with control. The results of the 30-year follow-up analysis, which is based on many more outcome events, extends and strengthens these earlier findings. We now report significant reductions of 26% in cardiovascular events, 35% in microvascular complications, 33% in cardiovascular deaths, and 26% in all-cause mortality, leading to an increase of 4.82 years in median survival and a mean increase of 1.44 years in life expectancy in the intervention group compared with control. These new findings further strengthen the evidence that lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance can reduce the incidence of serious diabetes complications and diabetes-related mortality.

Evidence from observational cohort studies has linked changes in dietary intake, increased physical activity, and weight loss to reduced risk of macrovascular complications in people with diabetes and those with impaired glucose tolerance,19 but equivalent evidence from clinical trials is scarce. Trial findings have shown improvements in cardiovascular disease risk factors,20 but neither the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study nor the Diabetes Prevention Program outcome studies showed reductions in cardiovascular disease events or mortality in participants receiving lifestyle interventions, although the Diabetes Prevention Program, after 15 years of follow-up, did show a modest reduction in microvascular disease in women.15 The Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcomes Study findings are unique because the benefits of intervention were observed across several outcomes, including cardiovascular events, microvascular complications, cardiovascular deaths, and all-cause mortality. Most of these outcome events occurred between 15 and 30 years after randomisation. The differences between this study and the outcome studies of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study and the Diabetes Prevention Program seem likely to be the result of a much longer follow-up that allowed enough time for sufficient numbers of events to develop and permit differences in outcomes to be detected.

By contrast with those used in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study, the lifestyle interventions in the Diabetes Prevention Program and the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study were designed to produce weight loss and were done in people with impaired glucose tolerance with an average BMI greater than 30 kg/m2. The investigators of both studies6,7,13 concluded that weight loss was an important factor in reducing diabetes incidence. In the Da Qing study, the baseline mean BMI of participants was only 25.7 kg/m2, and weight loss was encouraged only in those participants with a BMI higher than 25 kg/m2. The interventions resulted in only small changes in BMI, suggesting that the reduced diabetes incidence in the intervention group was mainly attributable to factors such as changes in dietary composition and increased physical activity rather than weight loss.5 Similar findings and conclusions were reported from the Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme,21 where the average BMI was 25.9 kg/m2.

In this study, we found greater reductions in mortality and cardiovascular disease in women than in men, despite similar reductions in the incidence of diabetes. Because the baseline prevalence of smoking was much higher in men than in women (62% vs 17%), we assessed its effect on mortality. For all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease events, the intervention was less effective in smokers, both men and women (appendix); however, in the total population, correction for smoking resulted only in minor changes in the apparent efficacy of the intervention (appendix). A lower adherence to lifestyle interventions by men compared with women beyond the 6-year trial, or sex differences in unmeasured confounders, might also have contributed to the more favourable intervention outcomes in women.

The effects of the interventions in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study might be primarily the result of the delay in diabetes onset, which postponed development of complications for a similar time interval. The lower rates of complications in the intervention group, occurring mainly 15 years or longer after randomisation, might be considered a legacy effect of the delay in diabetes onset. Another possibility is that the participants themselves or the clinics that delivered the interventions continued to practice the same strategies after the trial ended, but both intervention and control groups received similar levels of treatment with blood pressure-lowering and lipid-lowering drugs (appendix). The most straightforward explanation, for which we have presented supporting evidence, is that the delay in onset of diabetes itself can account for most of the postponed development of complications in the intervention group (appendix).

Although lifestyle interventions can reduce type 2 diabetes incidence in people with impaired glucose tolerance, questions remain about how to best translate this evidence into effective public health measures.22 The long-term benefits seen in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcomes Study might be more difficult to detect in regions where high-quality multifactorial care has led to diminishing rates of complications and mortality.2,23 Nevertheless, lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance should still remain a priority for populations in these regions, because such interventions could delay diabetes onset and postpone costly care. There might also be select groups with impaired glucose tolerance for whom drugs such as metformin or weight-reducing drugs are indicated to postpone the onset of diabetes.24,25 Although the evidence that lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance can reduce diabetes incidence is now unquestionable, whether such interventions reduce diabetes incidence in people with isolated impaired fasting glucose, or with increased HbA1c without impaired glucose tolerance, who constitute the majority of individuals with prediabetes as currently defined, is uncertain.10,21 However, in most parts of the world, especially in low-income and middle-income countries where the projected increases in diabetes prevalence are greatest1 and resources for diabetes care are restricted, lifestyle interventions might be the most practical and cost-effective way to address the ongoing epidemic.26

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size is small because the original trial was designed to study diabetes incidence and not complications. Second, we did not do systematic examinations at regular intervals on participants throughout the follow-up and, after 30 years, the proportions of surviving participants differed in the two groups, so that the reported outcomes were limited to those that could be identified and reliably assessed from medical history and other records. This approach required the use of slightly different criteria for microvascular outcomes than those used in our earlier reports.11,16 Third, we did not have information about adherence to lifestyle recommendations beyond the end of the trial interventions. Finally, these findings apply to prevention of type 2 diabetes and its complications only in people with impaired glucose tolerance and might not be generalisable to other categories of prediabetes.

Our study also has several strengths. First, participants were identified by population-based screening with use of 75 g oral glucose tolerance tests and constituted a representative sample of the people with impaired glucose tolerance living in Da Qing in 1986. Second, participants were randomly assigned according to the primary care clinic to which they had been pre-assigned to receive medical care, thereby reducing the potential influence of unmeasured confounders, facilitating delivery of group-based interventions, and reducing the likelihood of contamination between participants in the intervention and control groups. Third, little migration away from the city occurred since the start of the original trial, thereby keeping loss to follow-up to a minimum and enabling high completion rates many years after the initial trial. Fourth, when the trial was initiated, there was only a single referral hospital in the city, which continues to provide secondary and tertiary care for many participants, thereby facilitating access to their medical records. Fifth, the interventions were not associated with any serious side-effects or adverse reactions. Lastly, although this was an observational study, the data were analysed in accordance with intention-to-treat principles.

Our findings further strengthen the case for scaling up lifestyle interventions to combat the worldwide epidemic of type 2 diabetes. The benefits identified are probably applicable to all individuals at high risk of type 2 diabetes, especially in low-income and middle-income countries. Results from modelling studies have also shown that implementing such interventions can not only improve health and prolong life, but also save health-care resources in the long term in both high-income and lower-income countries.26,27 The goal of reducing the number of people with diabetes worldwide is likely to be best achieved through population-wide policy measures that change the environment and behaviours combined with specific lifestyle intervention programmes for high-risk individuals. Scaling up lifestyle interventions requires addressing and overcoming several challenges, including identification of the appropriate populations in which to intervene and reducing the costs of interventions.28 Lowering the cost of delivering the interventions might be achievable with the use of mobile devices and trained lay community health workers, which would further improve their cost-effectiveness.29

In summary, this study provides strong evidence of the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance in reducing the development of type 2 diabetes and of serious complications such as cardiovascular events, microvascular complications, and excess mortality due to type 2 diabetes, as well as extending life expectancy. Our findings support and strengthen evidence for the benefits of lifestyle intervention and suggest that, if widely applied, lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance would help to curb the global diabetes epidemic and its consequences.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

People with impaired glucose tolerance have a high risk of developing type 2 diabetes and are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. We searched PubMed for systematic reviews published in English between Jan 1, 2014, and Dec 31, 2018, using the search terms “lifestyle intervention”, “diabetes prevention”, “systematic review”, and “meta-analysis.” Findings from several reviews suggested that dietary and physical activity lifestyle interventions can delay the onset of diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance, an effect that extends up to 23 years beyond the period of active intervention. Lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance can also lead to improvement in cardiovascular risk factors. The more debilitating complications of diabetes—such as end-stage renal disease, lower extremity ulceration, gangrene and amputation, blindness, and cardiovascular disease—occur mainly in people who have had diabetes for 20–30 years. Whether or not lifestyle interventions that delay the onset of diabetes can ultimately lead to reductions in the incidence of such complications or increased life expectancy was unknown and can only be assessed by long-term follow-up studies.

Added value of this study

Our study, with a longer follow-up than previously reported by the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcomes Study and other studies, investigated the long-term consequences of a 6-year trial of lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance from Da Qing, China, on the development of cardiovascular events, microvascular complications, and life expectancy. 30 years after initiation of the trial, significant reductions in the incidence of each of these complications were identified in the intervention group, along with continuing reduction in mortality, leading to a significant increase in life expectancy. These data provide compelling evidence of the long-term benefits of lifestyle intervention in people with impaired glucose tolerance.

Implications of all the available evidence

The effects of lifestyle intervention in delaying the onset of type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance have been seen across several studies, suggesting that the long-term benefits identified in our study might be generalisable to many populations. In most parts of the world, especially in low-income and middle-income countries, where projected increases in diabetes prevalence are greatest and health-care resources are restricted, lifestyle interventions might offer the most practical and cost-effective way to address the ongoing diabetes epidemic. However, the long-term benefits reported in this study might be less likely to be observed in populations where high-quality diabetes care has led to diminishing rates of complications and mortality. Nevertheless, even in such populations, lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance should remain a priority, because they can postpone the onset of diabetes for some years and reduce the need for more expensive care. Our study provides strong justification to continue to implement and expand the use of such interventions to curb the global diabetes epidemic and its consequences.

Acknowledgments

The Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study and the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcomes Study were supported from 1986 to 1992 by the World Bank, the Ministry of Public Health of the People’s Republic of China, and Da Qing First Hospital; from 2004 to 2009 by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)–WHO Cooperative Agreement (U58/CCU424123–01–02), China–Japan Friendship Hospital, and Da Qing First Hospital; and from 2015 to 2018 by the US CDC–Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement (5U19GH000636–05), National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases & Fuwai Hospital, China–Japan Friendship Hospital, and Da Qing First Hospital. PHB is scientist emeritus at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and received NIH support for his work on this study. We thank all the study participants and their relatives who provided information that made this study possible. We also thank Yang Wang (National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases & Fuwai Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing, China), Xinran Tang (National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases & Fuwai Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences), and Shuqian Liu (Department of Global Health Management and Policy, School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, USA) for their statistical assistance; and Shuang Yan (Harbin Fourth Hospital, Harbin, China), Yanjun Liu (306 PLA Hospital, Beijing, China), and Yuqing Zhu (China–Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, China) for their help with data collection. Our special thanks go to the late Professor Pan Xiao Ren (China–Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, China)—this study would not have been possible without his leadership in the conception, design, and execution of the original study. The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the US CDC or the NIH.

Funding

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WHO, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, World Bank, Ministry of Public Health of the People’s Republic of China, Da Qing First Hospital, China–Japan Friendship Hospital, and National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases & Fuwai Hospital.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Data sharing

Data collected for this study can be shared and made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author and subject to an approved proposal and data access agreement.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas, 8th edn. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Srinivasan M, et al. Trends in cause-specific mortality among adults with and without diagnosed diabetes in the USA: an epidemiological analysis of linked national survey and vital statistics data. Lancet 2018; 391: 2430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett PH, Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Carraher MJ, Vasquez B. Longitudinal studies of the development of diabetes in the Pima Indians. In: Eschwege E, ed. Advances in diabetes epidemiology. Amsterdam: Elsevier Biomedical Press, 1982: 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edelstein SL, Knowler WC, Bain RP, et al. Predictors of progression from impaired glucose tolerance to NIDDM: an analysis of six prospective studies. Diabetes 1997; 46: 701–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance: the Da Qing IGT and Diabetes study. Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 537–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, et al. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1). Diabetologia 2006; 49: 289–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosaka K, Noda M, Kuzuya T. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: a Japanese trial in IGT males. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005; 67: 152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saito T, Watanabe M, Nishida J, et al. Lifestyle modification and prevention of type 2 diabetes in overweight Japanese with impaired fasting glucose levels: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171: 1352–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet 2008; 371: 1783–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindstrom J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet 2006; 368: 1673–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009; 374: 1677–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uusitupa M, Peltonen M, Lindstrom J, et al. Ten-year mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study—secondary analysis of the randomized trial. PLoS One 2009; 4: e5656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3: 866–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong Q, Gregg EW, Wang J, et al. Long-term effects of a randomised trial of a 6-year lifestyle intervention in impaired glucose tolerance on diabetes-related microvascular complications: the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome study. Diabetologia 2011; 54: 300–07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. Cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and diabetes incidence after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 23-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2: 474–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. Diabetes mellitus: report of a WHO study group—technical report no 727 Geneva: World Health Organization, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lillioja S, Mott DM, Spraul M, et al. Insulin resistance and insulin secretory dysfunction as precursors of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: prospective studies of Pima Indians. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1988–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Long-term effects of the Diabetes Prevention Program interventions on cardiovascular risk factors: a report from the DPP Outcomes study. Diabet Med 2013; 30: 46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanditha A, Snehalatha C, Ram J, et al. Impact of lifestyle intervention in primary prevention of type 2 diabetes did not differ by baseline age and BMI among Asian-Indian people with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabet Med 2016; 33: 1700–04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wareham NJ. Mind the gap: efficacy versus effectiveness of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3: 160–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carstensen B, Kristensen JK, Ottosen P, Borch-Johnsen K, on behalf of the steering group of the National Diabetes Register. The Danish National Diabetes Register: trends in incidence, prevalence and mortality. Diabetologia 2008; 51: 2187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratner RE, Christophi CA, Metzger BE, et al. Prevention of diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes: effects of metformin and lifestyle interventions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 4774–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.le Roux CW, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. 3 years of liraglutide versus placebo for type 2 diabetes risk reduction and weight management in individuals with prediabetes: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 1399–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Li C, Gong H, et al. An economic evaluation for prevention of diabetes mellitus in a developing country: a modelling study. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhuo X, Zhang P, Gregg EW, et al. A nationwide community-based lifestyle program could delay or prevent type 2 diabetes cases and save $5.7 billion in 25 years. Health Aff 2012; 31: 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cefalu WT, Buse JB, Tuomilehto J, et al. Update and next steps for real-world translation of interventions for type 2 diabetes prevention: reflections from a Diabetes Care editors’ expert forum. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 1186–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Priscilla S, Nanditha A, Simon M, et al. A pragmatic and scalable strategy using mobile technology to promote sustained lifestyle changes to prevent type 2 diabetes in India—outcome of screening. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015; 110: 335—40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.