Abstract

Coronary in-stent restenosis and late stent thrombosis are the two major inadequacies of vascular stents that limit its long-term efficacy. Although restenosis has been successfully inhibited through the use of the current clinical drug-eluting stent which releases antiproliferative drugs, problems of late-stent thrombosis remain a concern due to polymer hypersensitivity and delayed re-endothelialization. Thus, the field of coronary stenting demands devices having enhanced compatibility and effectiveness to endothelial cells. Nanotechnology allows for efficient modulation of surface roughness, chemistry, feature size, and drug/biologics loading, to attain the desired biological response. Hence, surface topographical modification at the nanoscale is a plausible strategy to improve stent performance by utilizing novel design schemes that incorporate nanofeatures via the use of nanostructures, particles, or fibers, with or without the use of drugs/biologics. The main intent of this review is to deliberate on the impact of nanotechnology approaches for stent design and development and the recent advancements in this field on vascular stent performance.

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory condition, occurs due to the build-up of fatty deposits within coronary arteries, which causes arterial narrowing, thereby hampering blood flow.1,2 The advent of percutaneous coronary intervention procedures that commenced with balloon angioplasty and presently intravascular stenting has relieved millions suffering from this coronary artery disease.3–5 Bare-metal stents (BMS) and drug-eluting stents (DES) are the two successful intravascular stent candidates that have revolutionized the field of interventional cardiology. Although BMS could restore occluded arteries and promote re-endothelialization of the denuded artery, it suffers from in-stent restenosis in nearly 30% of the cases.6,7 Early restenosis occurred due to the migration and hyperproliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) into the intimal space in response to vascular injury, which is caused by stent deployment.8–11 DES, the current clinical gold standard, evolved from BMS, which elutes an antiproliferative drug that reduced SMC hyperplasia within the stent, thereby reducing restenosis rates.12 DES could significantly reduce the complications of in-stent restenosis, but long-term trial revealed another challenge, which is late and very late stent thrombosis.13–15 The antiproliferative effect of DES slows the process of re-endothelialization, thus triggering platelet activation and late stent thrombosis.16,17 Even though the incidence of stent thrombosis is low, it occurs suddenly with acute life-threatening symptoms and high mortality.15,18 Additionally, the polymeric coatings utilized for drug incorporation induce inflammatory reactions and other instability issues, augmenting its complications.19,20 The development of DES progressed through various generations. First-generation DES had a stainless steel stent coated with drugs, either sirolimus or paclitaxel. Paclitaxel (PTX) inhibits microtubule disassembly and interferes with the cell cycle, leading to cell cycle arrest in G0–G1 and G2-M phases.21 Sirolimus binds to FKBP12 and subsequently inhibits the mTOR and PI3 pathway, arresting cell cycle in the G1 phase.22,23 First-generation DES used synthetic polymers such as poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate), poly(n-butyl methacrylate) or tri-block copolymer poly(styrene-b-isobutylene-b-styrene). Observations of late stent thrombosis and inflammatory cells surrounding the stent struts pointed to polymer hypersensitivity as the major issue.24 Second-generation DES utilized cobalt–chromium stents with more biocompatible polymer coatings such as phosphorylcholine and co-polymer poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) that reduced inflammation. These stents possess decreased strut thickness, improved flexibility, deliverability, enhanced biocompatibility, and superior re-endothelialization and are now the predominant clinical stents.25–27 To further reduce inflammatory response, third-generation DES utilize completely bioabsorbable polymers such as poly-lactic acid (PLA), poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), and polycaprolactone (PCL).28

Researchers are now keen to advance the stent technology and devise a novel stent material/surface that can promote re-endothelialization and concurrently inhibit restenosis, without altering the hemocompatibility or stent characteristics.29,30 In this direction, various novel schemes have been proposed and tested at lab scale or preclinically in small/large animal models, with a few taken forward to clinical trials. Among these innovations, stent surface engineering strategies that provide novel alterations in topography, chemistry, roughness, and wettability and also offer a platform for drug/biologics loading are thrust areas in coronary stent development.31,32 Additionally, the clinical needs of long-term safety and bio/hemocompatibility demand high standards for the choice of the stent material, design, or surface.33,34 Stent surface engineering is the process of modifying the surface of a stent material to enhance its overall performance characteristics. Engineering a surface for a desired outcome can be done either by chemically modifying the existing surface or by depositing a thin film with the desired properties onto the existing surface.35–37 This would obviate corrosion and ion leaching, improve biocompatibility and durability, and also enhance cell–material interactions. Nanosurface engineering encompasses engineering materials and/or technologies at the nanoscale, wherein one or more features are less than 100 nm in at least one dimension. This may refer to the size of individual crystals, grains, pores, particles, fiber diameter, etc.37 Specifically, by exploiting the high surface area to volume ratio, surface energy, roughness, reactivity, and wettability offered by nanostructures, nanosurface engineering of stents can be a way forward to design stents with improved biological performance.38,39 It is also necessary that the mechanical characteristics (stent deliverability, crimping and expansion profile, and coating durability) of the stents are retained without significant variations, after nanotexturing. Progress in nanotechnology now makes it possible to precisely design and modulate the surface properties of materials at the nanoscale via alterations in the method of processing, choice of the stent material, incorporation of drugs/biologics, etc.40–42 From the materials engineering perspective, physico-chemical properties of a biomaterial surface (namely, topographical features and roughness, surface chemistry, and hydrophilicity) can profoundly affect cellular mechanisms. Likewise, shape and size of the structures can regulate cellular functions by modifying the cytoskeleton organization. Nanoscale topographies can also critically control the signaling pathways at the molecular and subcellular levels.43,44 Thus, nanosurfaces can uniquely direct the overall biological response and hemocompatibility of the implanted stent material, mainly, its protein adsorption, vascular cell [smooth muscle cell and endothelial (EC) cell] adhesion and proliferation, etc.

Recent advances encompass a paradigm shift toward nanoengineered stent coatings to improve stent efficacy, which include polymer-less techniques of stent modification, coatings for controlled drug delivery, drug-free nanotopographical approaches, and nanoparticle (NP)-eluting/nanofiber-coated stents. Nanofiber coatings on stents developed by electrospinning are classified as nanotechnology, as the electrospun fiber diameters are at the nanoscale,45 although it does not represent “surface engineering.” A wealth of literature exists that delves on various nanotechnology-based techniques that help to generate nanoscale surface features and coatings on existing stent materials. Such nanoengineered stents alleviate the problems of restenosis, lack of re-endothelialization, local inflammatory response, and thrombus formation,41,46 which are common to BMS or DES. The future generation of cardiovascular stents will be nanotechnology-centric, due to the multifarious benefits it promises. Despite these advantages, a relevant clinical translation of stents utilizing this technology in the biomedical device industry is still awaited.47,48 This review throws light into the diverse nanosurface modification strategies (Fig. 1) that are widely adopted for developing novel stents and their associated cellular response in vitro and in vivo. To translate the research findings from bench to bedside entails the development of a viable stent prototype and its further preclinical evaluation in animal models, followed by regulatory approval and clinical testing. The journey of those few stents that surpassed these standards to the clinical trial stage is also presented.

FIG. 1.

Various nanoscale surface engineering strategies (nanostructured surface and thin films, nanoparticulate, and nanofibrous) adopted as coatings on coronary bare-metal stents to prevent in-stent restenosis and promote re-endothelialization.

Nanostructured surfaces and nano-thin-film coatings

Nanoscale architectures on stent

Texturing the stent surface at nanoscale may be beneficial, given the fact that nanosurface topography mimics the natural extracellular matrix and can regulate vascular cell adherence and proliferation.49 Cells when in contact with nanostructured surfaces not only respond to the type of material, but also to the surface topology.50 Surface properties such as topography and chemistry, roughness and wettability, are known to influence protein and cell adhesion.41,51 Moreover, creation of reservoirs and pores at nanoscale provides a platform to load drugs efficiently.52 Development of polymer-free stents can eliminate the problems such as polymer delamination and the long-term risk of inflammatory response, and thereby help to better endothelial regeneration.53 This section elaborates the diverse nanostructured surfaces on vascular stents and their biological response. Among the medically relevant metals such as titanium (Ti), magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), and the alloys, viz., stainless steel (SS), cobalt–chromium (CC), nitinol (NiTi), etc., metallic stents are mainly based on the alloys of SS, CC, NiTi, Mg, and Fe.54 Significant efforts are under way to obtain nanostructured surfaces on these alloyed metals, which include the widely studied electrochemical anodization process, physical/chemical vapor deposition (CVD), thermochemical processing, lithography, etc.55

Nanotubular structures

Titanium dioxide nanotubes (titania nanotubes or TNT) can be fabricated using diverse methods including sol-gel,56,57 hydrothermal processes,58–60 template-assisted synthesis,61,62 seeded growth,63 and electrochemical anodization.64–67 Among all these methods, electrochemical anodization is widely used, because it provides a relatively simple and effective way of generating nanotubular structures. Moreover, it is a cost-effective process which offers the feasibility to tune the size and shape of nanotubular arrays to the desired dimensions. Furthermore, the tubes prepared via this method are highly ordered, well-defined with high aspect ratios, and are vertically oriented to the substrate, with good adherent strength.68–70 Most importantly, the dimensions of nanotubes such as diameter, length, wall thickness, etc., can be controlled precisely and modified easily by modulating the anodization parameters.71,72 However, such nanotubes have mostly been developed on metallic Ti or NiTi surfaces by anodization in acidic or alkaline conditions at different applied voltages for varied time intervals.73,74 By changing the anodization parameters (applied voltage and anodization time), TiO2 nanotubes having different diameters from 15 to 300 nm, and different lengths (nm to mm) can be obtained.75 The excellent potential of titanium nanotubes is mainly due to its high effective surface and the possibility to vary their geometry (diameter and length), which could be specifically designed for a desired biological response.74

Titanium, due to its low tensile strength and ductility, failed to make an impact as a sole stent material, because of its higher probability of tensile failure upon expansion when developed as stents.76,77 Despite these limitations, immense information has been garnered on the impact of nanoscale dimensions in modulating vascular cell behavior in vitro by utilizing anodized Ti surfaces. An optimal surface engineered stent should inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation to prevent in-stent restenosis, but simultaneously enhance endothelial cell adhesion and proliferation for restoration of a healthy endothelium.78 Several studies report TNTs as a promising platform for cardiovascular stent applications owing to their selective regulation of vascular cell response, specifically endothelial (EC) and smooth muscle cells (SMC), but the reason for this selective cell proliferation is still unknown and not clearly elucidated by researchers. The cell viability and activity on a nanostructured surface depends on various parameters such as the surface topography and roughness, surface wettability, and surface chemistry, which collectively dictate the cell response.39 Recently, a study was conducted to investigate the combined influence of nanotopography and surface chemistry on the in vitro biological response of TiO2 nanotubes. It was observed that nanotopography, surface chemistry, and wettability as well as morphology, cooperatively contributed to the reduced platelet adhesion and preferential vascular cell response.79 Several other studies report that TiO2 nanotubes of varied nanotube diameters (30–90 nm) promoted EC growth and proliferation, with concurrent inhibition of smooth muscle cells.80,81 The highlights of such in vitro studies include faster migration of ECs on nanotubular surface82 and lower inflammatory response, resulting in reduced TNFα-induced SMC proliferation,83 good hemo- and cytocompatibility with lessened platelet adhesion, and enhanced endothelial cell adhesion and proliferation for smaller diameter (30 nm) nanotubes.84 Rapid re-endothelialization, a key to the success of a cardiovascular implant device, has been achieved through several synergistic approaches on TiO2 nanotubular surfaces. Fibronectin (Fn), an extracellular matrix protein, when immobilized onto TNTs via an intermediate polydopamine (PDA) layer, has offered increased nitric oxide and prostaglandin (PGI2) secretion, indicating an increased functionality of ECs on these surfaces.85 Likewise, TNTs functionalized with polydopamine (PDA/NTs) showed a remarkable enhancement in the mobility of ECs with longer migration distances than that of bare Ti and TNTs, respectively.86 PDA/NTs incorporating a thrombin inhibitor, bivalirudin (BVLD), demonstrated high BVLD elution beyond 70 days. This synergism brought about a significant inhibitory effect on thrombin bioactivity, with concomitant less adhesion, activation, and aggregation of platelets, and selectivity for EC over SMC in a competitive growth environment.87 Recently, utilizing copper as a catalyst for effecting the release of nitric oxide from endogenous nitric oxide donors, Cu-loaded PDA nanoparticles were stacked onto TNTs. This surface yielded a controlled and steady release of Cu, sufficient to enable the release of NO within the physiological range. The in vivo effect induced by this synergy aided in preventing intimal hyperplasia and coagulation, with simultaneous rapid re-endothelialization after implantation in the abdominal aorta of rats.88

Another study utilized a nanotubular oxide layer as a drug reservoir on anodized Ti-8Mn alloy as a nickel and polymer-free matrix for drug-eluting stents. The highly ordered Ti-8Mn oxide NTs promoted cell (neonatal mice skin cells) proliferation in comparison with flat substrates. It was noted that alloying titanium with 8% manganese hindered charge transfer from fibrinogen to the material, thus preventing blood clots and thrombus formation. They demonstrated that the drug loading efficiency was higher on this alloyed nanotube surface, thus establishing Ti-8Mn oxide NTs to be a superior platform for drug loading than TNTs.89 Self-grown nanotubes of two nanotube morphologies, viz., homo, and hetero-NT, which are highly ordered and vertically aligned, with variations in tube diameter (80–190 nm), were developed on Ti–17Nb–6Ta substrate. Both NT morphologies showed significantly better results for endothelial cell proliferation, with homo-NTs displaying superior biological activity and drug loading capacity than hetero-NTs.90

Despite the abundant literature on TNT-based systems for cardiovascular stenting, no studies have yet proven the utility of this material for clinical translation. This could be due to the limitations of Ti as the base material for stent manufacturing and the complexity involved in translating TiO2 nanostructures onto clinically available coronary stent materials like SS and CC. This requires that titanium, which is deposited on SS or CC stents, be anodized to generate TNTs. Here, the restraints posed by the process of anodization (strong acidic/alkaline environment) can hamper the durability of the extremely thin stent struts (typically <100 μm) upon expansion and crimping. In a sole in vivo study reported thus far on a titanium stent prototype (Ti6Al4V) bearing nanotopographical cues of diameter 90 ± 5 nm and height 1800 ± 300 nm, significantly lower restenosis rates with minimal intimal hyperplasia and good stent strut coverage were observed after implantation in rabbit iliofemoral arteries as depicted in Fig. 2. This ascertained the importance of nanotopography in offering reduced in-stent restenosis, with concurrently enhanced endothelialization.91

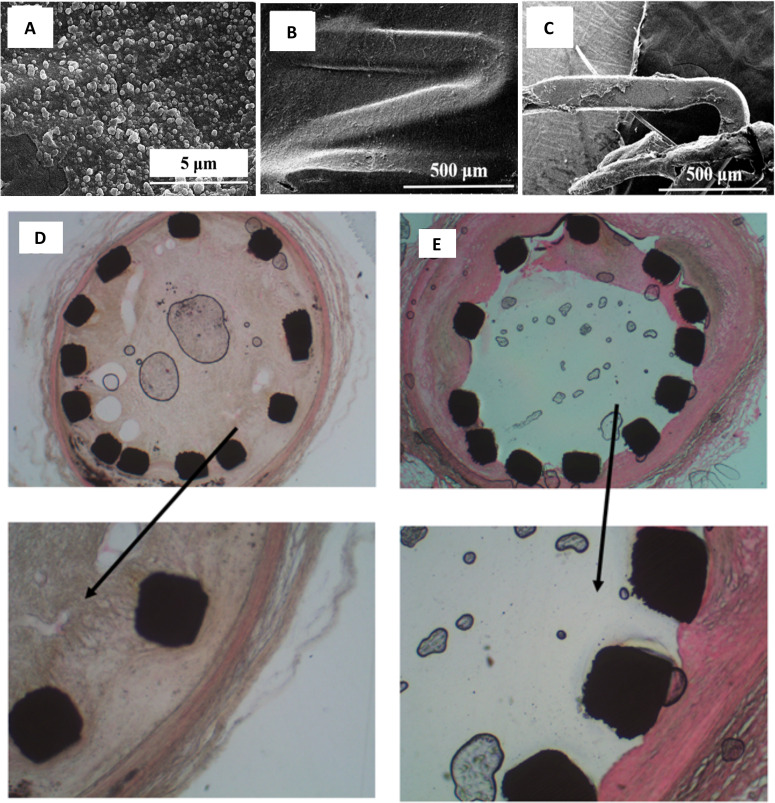

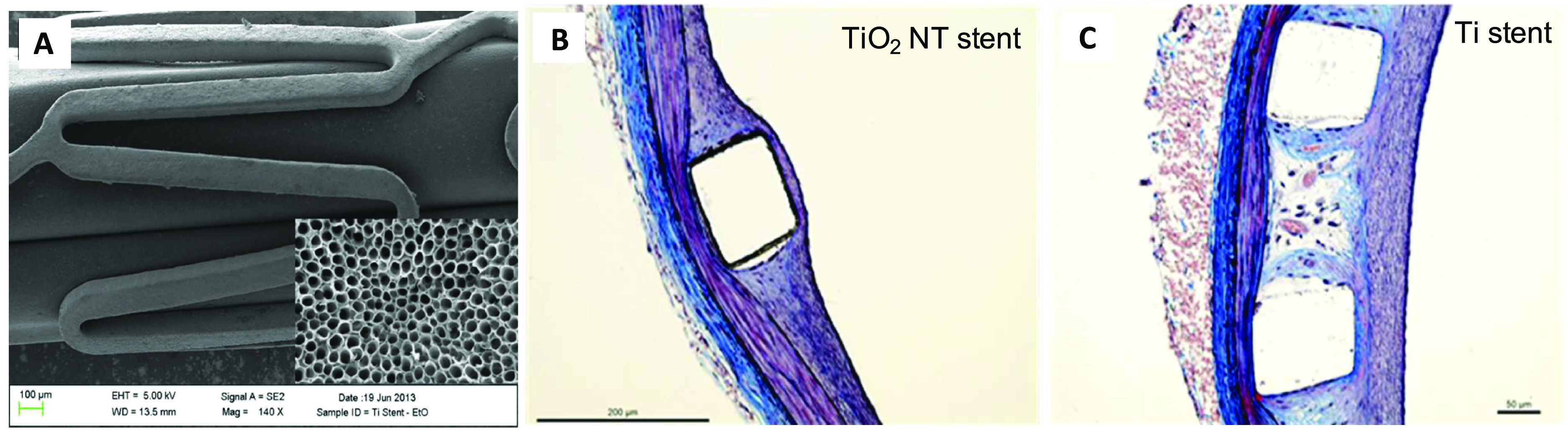

FIG. 2.

(a) Electron micrograph of titania nanotube coated stent. Inset: nanotubes with an average nanotube diameter of 90 nm (magnification ×250 000). Moffat trichrome-stained images of a stented artery. (b) Titania nanoengineered and (c) Ti stents, showing a 15.6% and 5.6% thinner neointima over the struts for TiO2 NT stents than Ti stent. Reprinted with permission from Nuhn et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9(23), 19677–19686 (2017). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

In contrast to titanium-based stents, which find minimal use in coronary stenting, nitinol (NiTi), a widely explored alloy of titanium with nickel, finds applicability as coronary stents. The process of anodization helps to generate Ni–Ti–O nanotubular structures on the NiTi surface. The impact of nanotopography on vascular response to nitinol substrates was akin to titanium nanotubular structures when investigated in vitro using ECs and SMCs. These NTs showed reduced proliferation of SMCs, along with a decreased expression of collagen I and MMP-2, and parallelly enhanced EC spreading and migration.92 Moreover, nanotube diameter was found to influence EC and SMC response. While SMCs proliferated less, ECs showed increased proliferation and migration, with augmented production of elastin and collagen, on larger diameter (110 nm) NTs.93 Regardless of the limited investigations done on NiTi surfaces, nanotopography, especially NTs, showed promise for stenting applications and surprisingly these nanostructures always exhibited a preferential vascular response, the reason for which remains to be explored. Researchers have also developed a nanotubular α-Fe2O3 coating on biodegradable iron stents. PLGA coated on the NT surface incorporating the drug (Rapamycin) could efficiently reduce the initial burst with a sustained drug release of 30 days. These surfaces showed better EC viability than SMC along with good hemocompatibility.94

Other nanotopographies (nanoleaves, nanograss, nanoflakes, nanopillars, and nanowires) on stent surface

As an alternative to anodization, researchers have delved into chemical/thermochemical processing or lithography95,96 as a means to develop uniform and homogeneous nanostructures on metallic surfaces.31 Hydrothermal/thermochemical synthesis proposes various advantages such as low cost, simple experimental set up, and high yield.97 In a normal hydrothermal reaction, acidic or alkaline media are subjected to elevated temperature and pressure for a specific time, thus providing a one-step process for the generation of highly crystalline materials.98 The reaction parameters such as concentration and type of solvent, reaction temperature and time, offer significant effects on the formed nanostructures.99,100 Diverse titania nanotopographies were generated on Ti substrates using this facile thermochemical technique in NaOH at 200 °C, which exhibited a preferential vascular cell response, like for titania NTs.101 Static and dynamic blood contact studies done on Ti stent prototypes revealed these hydrothermally generated nanostructures to be antihemolytic, with minimal activation of coagulation cascade and platelets.102 Among the different topographies, a specific titania nanoleafy structure [Fig. 3(a)] yielded superior cyto- and hemocompatibility response in vitro, with high endothelialization and low SMC proliferation [Figs. 3(b) and 3(c)]. The uniqueness of this simple polymer-free and drug-free nanotexturing approach is that it could be readily translated onto any metallic stent substrate or on clinical stent materials of SS and CC. The nanoleafy structures were found to be extremely stable and adherent upon stent crimping and expansion with good corrosion resistance.103 This titania nanotexturing developed on SS bare-metal coronary stents presented minimal in-stent restenosis, effective endothelialization, and no thrombus formation after 8 weeks of implantation in a rabbit iliac artery model,104 as evident from Figs. 3(d)–3(f).

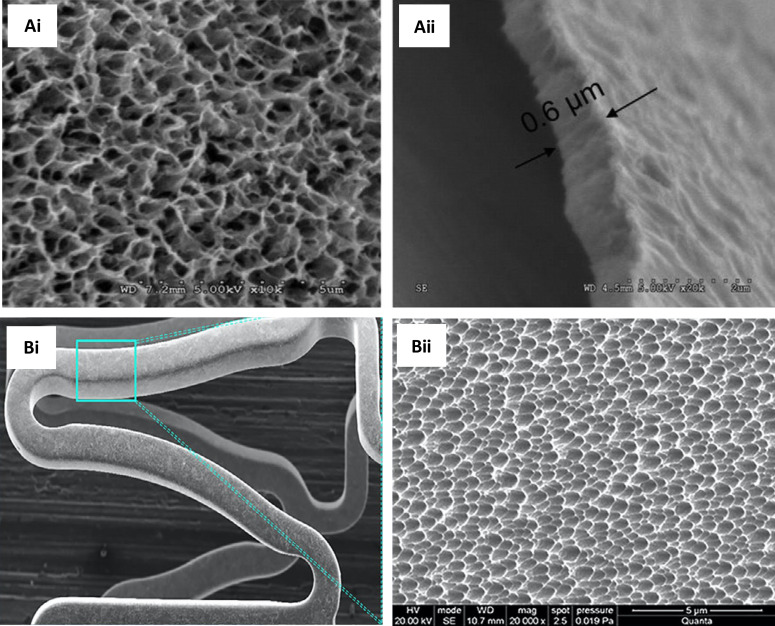

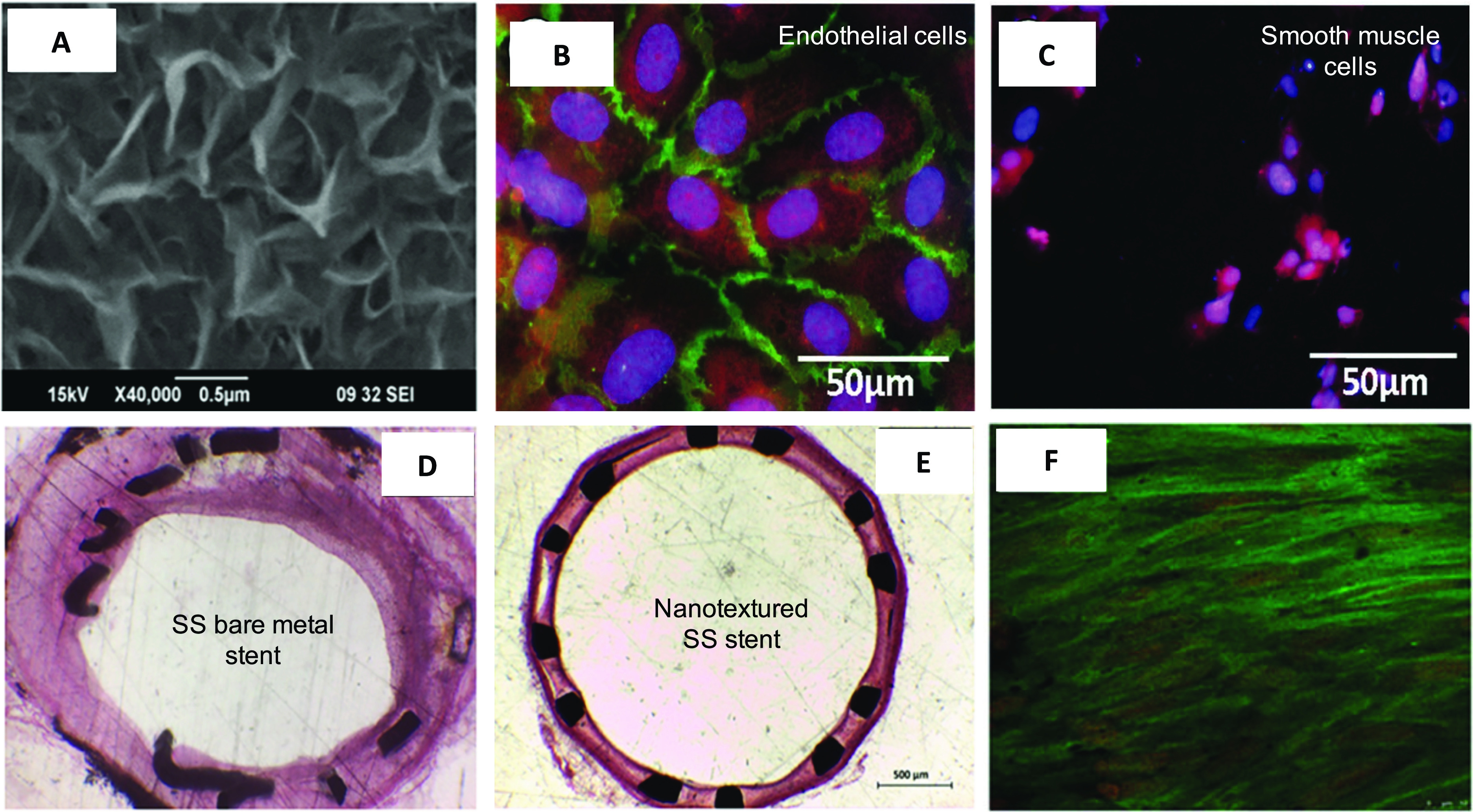

FIG. 3.

(a) Electron micrograph of titania nanoleafy textured stent surface (magnification ×40 000). Fluorescence imaging of (b) endothelial cells stained for F-actin (red) and PECAM1 (green) and (c) smooth muscle cells stained for F-actin (red) and nucleus (blue) on nanotextured SS surfaces, showing preferential adsorption and proliferation of ECs over SMCs on nanoleafy SS surface. Reprinted with permission from Mohan et al., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 6, 1601353 (2017). Copyright 2017 John Wiley and Sons. H&E images of rabbit iliac artery after 2 months implantation of (d) SS bare-metal stent and (e) nanotextured SS stent, showing nearly 50% decrease in neointimal stenosis for the nanotextured stent. (f) Immunofluorescent en-face stained images of wheat germ agglutinin on ECs in nanotextured stent implanted artery, showing complete endothelialization (scale bar: 10 μm). (a) and (d)–(f) Reprinted with permission from Cherian et al., ACS Omega 5, 17582–17591 (2020). Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Likewise, direct nanotexturing of metallic substrates have also yielded nanotopographical features. For example, nanosized pyramidal structures were developed on SS substrates by hydrothermal treatment under alkaline conditions, which showed improved corrosion resistance, hemocompatibility, and EC growth, while inhibiting the proliferation of SMCs.105 A superhydrophilic nanoscale morphology with nanograss-like structures was likewise generated on Ni-free Ti–29Nb alloy after subjecting it to hydrothermal processing in alkaline sodium hydroxide solution at 250 °C for 10 h. This nanostructured material showed reduced hemolysis, minimal platelet adhesion, and activation upon contact with blood. The initially adsorbed intermediate water layer on this superhydrophilic surface might have caused resistance to platelet attachment, which can be attributed to the existence of a large number of hydrogen bonds.106 In the same manner, radially emanating metallic nanopillar structures were created on the surface of CC stent wires (MP35N) via controlled RF plasma processing technique.107 These uniformly coated nanopillar arrays of diameter 100 to 300 nm were developed directly on the stent wires. This surface displayed greater endothelial cell growth and functionality, continuous and complete endothelial monolayer formation, and minimal oxidative stress level in ECs.108 Increased EC and SMC adhesion has also been reported on nanostructured Ti and CC surfaces generated by compacting commercially pure metal particulates. Well-spread morphologies of both vascular cell types, with an increased ratio of viable ECs to SMCs, were noted on these nanostructured surfaces. A large number of particle boundaries at the surface of nanostructured metals were speculated to be responsible for improved adhesion of vascular cells on these surfaces.109 Such nanostructured Ti also showed greater competitive adhesion of ECs than SMCs.110,111 Utilizing a simple chemical conversion treatment of Mg−Nd−Zn−Zr alloys in 0.1 M potassium fluoride solution, they were surface textured to deposit MgF2 film with nanoscale flake-like features (∼200–300 nm-sized, having a thickness of 800 nm). These nanotextured films showed a significant reduction in corrosion rates and presented a favorable surface for enhanced viability, growth, and proliferation of ECs. Furthermore, implantation in rabbit abdominal aorta confirmed a complete and uninterrupted endothelial lining on the nano-MgF2 modified stent, along with minimal inflammatory reaction, thrombogenicity, and restenosis.112 Similar to the above studies, ultra-thin (300 nm) and chaotic one-dimensional (1D) aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanostructures having a nanowire (NW) morphology were synthesized by chemical vapor deposition on a glass substrate. Al2O3 NWs presented a preference for EC adhesion and proliferation in comparison with SMC.113 ECs seem to favor growth on low-density NWs, while SMCs disliked this topography in contrast to commercially available microstructured Al2O3 plates.114 Recombinant filamentous bacteriophages (re-phage) with a cell adhesive peptide (RGD) were immobilized onto Al2O3 NWs by a simple dip-coating process for improvement of cell binding. This re-phage-coated material allowed a strong EC–nanostructure interaction, with increased cell population and viability, in comparison with Al2O3 NWs.115 A novel superhydrophobic hybrid coating that couples the effect of the topography of Al2O3 NWs and the low surface energy of poly (bis (2,2,2-trifluoroethoxy) phosphazene) (PTFEP) was developed by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method and ultrasonic infiltration technique, for improved hemocompatibility of cardiovascular implants. The dual-scale surface roughness (micro/nano) and the superhydrophobic nature of the nanowired substrate reduced the contact area between the surface and blood, yielding a non-wetting surface that prevented platelet adhesion and activation. This reduced contact area and non-wetting nature imparted significant blood repellence to the surface.116

The impact of surface roughness in modulating EC response has also been investigated by various groups, especially on Ti surfaces. It is generally noted that ECs interact more efficiently on nanometer rough surfaces than on flat surfaces, with enhanced adhesion, proliferation, and migration. Nanoscale surface roughness on Ti enabled better and well-adherent endothelium under flow conditions as well.117 Such nanotexturing approaches have also been translated to metallic alloys and polymers. Commercially pure titanium, titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V), and polymers used to incorporate drugs in DES (e.g., polyethylene terephthalate, polytetrafluoroethylene, polyvinyl chloride, polyurethane, and nylon) were modified using an ionic plasma deposition and nitrogen ion implantation plasma deposition process to generate nanorough surface features. It was demonstrated that changes in surface chemistry and roughness at the nanoscale resulted in improved adhesion of ECs.118

Thus, results from literature point to the fact that nanostructured surfaces, irrespective of the method used or its surface chemistry, are able to modulate vascular cell response preferentially, with specific nanotopographies favoring endothelial cell adhesion and proliferation over smooth muscle cells. Various studies cited in this review,103–105 especially the titania nanotubes,80–83 have shown a selective response to the vascular cells, specifically ECs and SMCs. The exact reason for this preferential response still remains unclear and requires further investigation.

Patterned nanostructures

Femtosecond laser irradiation can produce periodic nanostructures on metals and semiconductors.119–121 Hierarchical micro/nanostructures possessing properties of dual-scale roughness were fabricated on Ni–Ti using a femtosecond laser for the surface modification of stents. Hydrophilic periodic nano- and hydrophobic micro/nanostructures formed could regulate the spreading of ECs, with more effect observed at the nanometer scale. Moreover, platelets failed to adhere to the micro/nanostructures.122 Utilizing femtosecond laser, micro-/nanobiomimetic surface patterns mimicking the morphology of VSMCs were generated on 316L SS stents. In vitro studies showed that this VSMC-biomimetic surface pattern of width ∼700 nm promoted adhesion, proliferation, and migration of ECs, with rapid re-endothelialization in vivo after 30 days.123 Ti patterning formed by plasma-based dry etching technique with a width and spacing varying from 750 nm to several micrometers presented significantly improved function and orientation, higher density, viability, and proliferation of rat aortic ECs compared to substrates with micro and random nanofeatures.111 Patterned TiO2 nanogratings as small as 70 nm significantly inhibited the proliferation of SMCs and concurrently enhanced EC proliferation. ECs could sense these nanogratings, yielding elongated morphologies with a larger number of focal adhesions on the patterned surfaces.124 Large-scale nanopatterns were developed on NiTi stents using target-ion-induced plasma sputtering (TIPS) onto which the PTFE layer was coated, resulting in a nanoporous surface having diameters ranging from 100 to 200 nm and depths of 600 nm, with infiltration of PTFE into nanoscale pores.125 Tantalum coating was provided on the same nanoroughened NiTi stents to generate distinct and uniform nanoscale surface structures (50–100 nm), as a means to reduce Ni ion release from the base material. These Ta-coated NiTi stents significantly improved EC attachment, proliferation, density, and coverage, in comparison with bare stents that had a considerable decrease in EC proliferation due to rapid dissolution of Ni ions.126 A similar process was used to develop a Ta-implanted nanoridge surface with a ripple-like surface pattern having round hills and steep valleys (depth of ∼470 nm) on CC stents. ECs that adhered on this stent surface formed numerous inter-endothelial adherent junctions through cell membrane protrusions, with faster migration rates and proliferation, besides exhibiting minimal platelet activation and fibrin formation. Synergistic effects of Ta and nanoscale surface features of this stent in rabbit iliac artery model resulted in very minimal intimal hyperplasia and lumen loss, with rapid re-endothelialization.127 Similarly, zirconium (Zr) ion implantation using metal vapor vacuum arc plasma source with pure Zr as the target material resulted in a nanopatterned Zr–NiTi alloy. Further, a thick Ni-depleted composite ZrO2/TiO2 nanofilm was developed on the surface of zirconium–NiTi (Zr–NiTi). Corrosion resistance was increased, depletion of Ni in the superficial surface layer resulted in reduced ion release rate of Zr–NiTi, and EC proliferation was favored after five and seven days of culture.128

Nanoporous architecture on stents for drug/biologics loading

In addition to the impact of nanotexturing on cellular response in vitro and in vivo, researchers have investigated the combined effects of nanotexturing with biologics/drug incorporation. Mostly, the nanotextures present on metallic surfaces are porous and these can be efficient sites for high drug loading.41 This polymer-free approach can be a viable strategy to circumvent the risks of using polymers as drug-eluting stent coatings.129,130 In one such study, an anti-CD146 antibody anchored onto a porous architecture bearing nanosized silicone filaments on CC stent surface helped to develop an endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) capturing stent. This stent enabled enhanced selective capture and adherence of circulating EPCs from blood and thereby induced rapid healing of endothelium at 1-week implantation in porcine, resulting in reduced neointimal thickening. Thus, the co-existence of the silicone nanofilaments and CD146 antibody provided synergistic effects for suppression of in-stent restenosis by promoting re-endothelialization.131 A nanoporous Al2O3 nanocoating (∼200 nm thick) on NiTi alloy substrate deposited via simple sputtering, followed by functionalization with VEGF, helped to significantly enhance EC adhesion, spreading, and proliferation. Additionally, higher levels of NO and prostaglandin (PGI2) secretion on the nanocoating indicated its advantage on EC functionality.132 Similarly, a ceramic stent coating of nanoporous alumina on SS stents served as a suitable carrier for the drug tacrolimus. These drug-coated nanoporous stents showed inhibition of neointimal proliferation in rabbits.133 However, after implantation in a porcine model, particle debris resulting from the cracking of ceramic coating during stent expansion resulted in increased neointimal growth and stenosis in these stents.134 A polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stent (PFSES) with a unique nanoporous surface was developed by adopting a simple electrochemical method to generate nanosized pores (∼400 nm) on the surface of SS stents. These stents when implanted in pigs showed low levels of neointima and inflammation than BMS, 3 months post-implantation.135 The same polymer-free nanoporous stent was loaded with the drug paclitaxel, revealing a significant reduction in neointimal hyperplasia and better endothelialization than polymer-based SES.136 This nanoporous stent, in another study, was spray-coated with sirolimus drug on the abluminal surface and immobilized with anti-CD34 antibodies on the blood-contacting luminal surface. This polymer-free stent completely re-endothelialized in 2 weeks with minimal restenosis in vivo.137 These nanoporous stents with anti-CD34 antibody immobilization alone facilitated effective capture of CD34+ ECs, with significantly high endothelialization.138 The same clinically tested platform as above, but containing CREG (a markedly upregulated gene during SMC differentiation) showed a similar degree of inhibition of SMCs as that of the drug sirolimus. However, EC proliferation was improved by CREG, in contrast to sirolimus which inhibits ECs. This CREG eluting stent attenuated neointimal formation with accelerated re-endothelialization after 4 weeks in porcine.139 BICARE is a novel version of the above nanoporous PFSES which elutes dual drugs (rapamycin and probucol). To assess the safety and efficacy of this PFSES-based dual drug delivery system (DDES), nanoporous SS stents loaded with probucol and rapamycin in combination were implanted in a porcine coronary artery. This DDES was found to be as safe as the commercial BMS and SES, but did not show any enhancement of re-endothelialization in porcine arteries.140

Nano-thin-films and their combination with drugs/biologics

Apart from the nanostructured topography generated on metallic surfaces, deposition of thin films on stents/substrates has also been widely examined. The concept of utilizing stent coatings was initially introduced as a means to mask the underlying stent surface, to prevent ion leaching from bare-metal stent surface into the bloodstream.41 Coating a stent with a thin film of biocompatible surface can improve blood compatibility, vascular cell response as well as the corrosion potential of the implant.4,141 These coatings can act as an inert barrier between the blood/tissue and metal with good biocompatibility.142,143 Deposition of thin films is a common and effective technique in surface engineering. Methods for thin-film deposition can be either physical or chemical, based on the nature of the deposition process. Chemical methods such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD), atomic layer deposition (ALD) and sol-gel involves gas- or liquid-phase chemical reactions, whereas physical methods involves sputter deposition, evaporation, and spraying.144,145 Such coatings can be based on polymers, inorganics, or other biocompatible materials.146

Titanium-oxide and titanium-oxy-nitride nano-thin-film coatings on stents

Titanium oxide-based coatings are the most promising coatings for cardiovascular stent applications among all inorganic materials, offering good blood compatibility, which is attributable to its surface energy and semiconducting behavior.147,148 The addition of nitrogen to TiO2 films has shown remarkable improvements in its blood compatibility due to the presence of nitride oxide on the surface.149 Adhesion of platelets and fibrinogen deposition were minimal for titanium–nitrideoxide (TiNOx) coatings in comparison with titanium oxide.150,151 TiNOx coating of thickness 500 nm was generated on metallic stents by reactive physical vapor deposition (PVD). The number of ECs on titanium oxide and titanium nitride was higher in comparison with control SS and NiTi substrates.152 Preclinical testing of these TiNOx-coated stents in a porcine model showed significantly less neointimal hyperplasia than SS stents at 6-weeks.149 The promising results from this study facilitated its transition to the clinical trial stage. Likewise, oxides of titanium, viz., Ti–O and TiO2, have been extensively investigated as stent coatings. A 25-nm-thick Ti–O film modified CC vascular stent developed via magnetron sputtering exhibited a faster rate of endothelialization without any thrombus, in-stent stenosis, or inflammatory reaction in vivo.153 Similarly, TiO2 thin-film layers consisting of embedded nanoscale TiO2 particles deposited on electro-polished SS using sol-gel dip coating showed enhanced blood compatibility in vitro, with longer blood clotting times and lesser platelet adhesion.154 Two types of titanium-based coatings having different thicknesses of 300 and 500 nm, respectively, deposited on 316L SS by a sol-gel route, displayed increased proliferation rates of ECs and also induced prolonged plasma recalcification time. In contrast, response to SMCs was not significantly altered by this chemistry155 and proved no superiority to BMS in vivo.156 In another study, a 100-nm-thick TiO2 film having a surface roughness of 35 nm deposited on magnesium–zinc (Mg–Zn) bioresorbable vascular scaffold helped to improve endothelial cell spreading with a good cytoskeletal arrangement. Moreover, the protective TiO2 layer had the potential to reduce the degradation rate of bare Mg–Zn alloy and retain its functionality.157 Likewise, Cu-doped TiO2 nanofilms containing Cu ion crystals sized 10 nm were deposited on wires through sol-gel method, wherein Cu behaved as a redox co-catalyst and promoted NO release. In vitro studies revealed a significant reduction of fibrinogen adsorption and platelet coverage, along with superior antithrombotic properties and anti-inflammatory ability. Reduction in neointimal thickening and suppression of inflammation, along with re-endothelialization, were noted in vivo within 4 weeks.158

Metallic coronary stents based on CC coated with TiO2 by a plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) process and loaded with drugs/biologics have also been tested for their ability to improve in vivo response after implantation in animal models. TiO2 films having a surface roughness of ∼10 nm and chemically grafted with heparin were found to reduce neointima formation with decreased inflammation and fibrin deposition.159 A similar study by the same group also investigated the effect of polymer-free TiO2 film-coated stent with abciximab or alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) in vivo. Both the thin-film-coated stents showed an effective reduction of in-stent restenosis and accelerated re-endothelialization.160 A similar TiO2 coating on stents, but having a dual-delivery system of abciximab (drug) and Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4)-plasmid (gene), showed analogous results.161 Yet another platform developed by this group for coating drugs like tacrolimus or everolimus on stents was nitrogen-doped TiO2 (N–TiO2) thin films. Drug coating was provided on the abluminal surface by electrospraying/dip coating, while N–TiO2 films were deposited by PECVD. The drug coating proved to be effective in reducing inflammation and in-stent restenosis, while the titania layer helped in increased re-endothelialization and reduced thrombosis in vivo (Fig. 4). The study yielded results that proved the non-inferiority of their stent to commercial controls.162,163 A 200-nm-thick nano-TiO2 ceramic film was deposited by radio frequency magnetron sputtering along with EC selective adhesion peptide Arg-Glu-Asp-Val (REDV) coating (polydopamine-coating technology) on 316L SS stents, which efficiently reduced nickel ion release from SS, and also promoted EC adhesion and proliferation with increased NO release. REDV/TiO2-coated stents when implanted in rabbit iliac arteries effectively reduced in-stent restenosis and promoted re-endothelialization as compared to TiO2-coated rapamycin-eluting stent and BMS.164

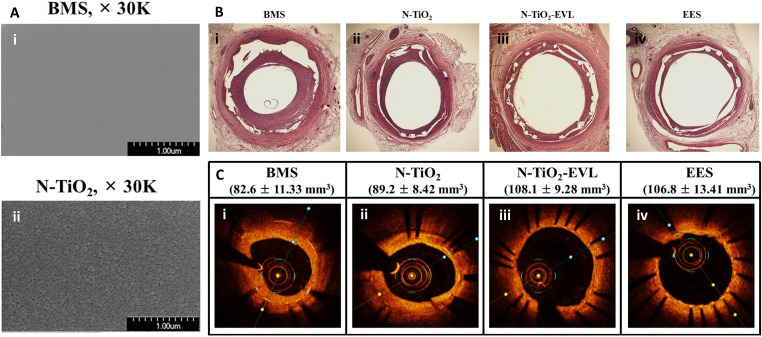

FIG. 4.

(a) SEM images of (i) BMS and (ii) N–TiO2 film deposited on a bare stent. (b) Histopathological H&E staining and (c) optical coherence tomography of porcine coronary arteries implanted with (i) BMS, (ii) N–TiO2, (iii) N–TiO2 with everolimus, and (iv) EES for 4 weeks. The restenosis area was significantly decreased in the N–TiO2-everolimus group compared to that in the BMS group and was at par with the commercial EES. Reprinted with permission from Park et al., Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 91, 615–623 (2018). Copyright 2018 Elsevier. (BMS: bare-metal stent; N–TiO2: nitrogen-doped TiO2 film; EES: everolimus-eluting stent.)

Carbon-based nano–thin-film stent coatings

Diamond-like carbon (DLC) thin films have also been investigated in earlier days as a stent coating because of their outstanding mechanical characteristics, and specifically the ability to reduce platelet activation and thrombus formation. DLC films of thickness 50 nm were deposited on CC stents using the PECVD method with excellent stability and crack resistance. Plasma irradiation of these films resulted in increased functional groups on its surface, making it possible to graft polymer with drugs to develop a DES that can continuously and slowly elute drugs.165,166 Biocompatible Si-doped DLC films deposited on Ti6Al7Nb alloy using magnetron sputtering exhibited a positive effect on the proliferation and viability of ECs.167 Nanothin DLC films deposited by physical vapor deposition (PVD) on CC stents had a nanostructured surface with well acceptable hemocompatibility and anti-inflammatory properties. These stents showed effective inhibition of fibrin deposition and thrombus activation, along with an early and complete endothelial healing (30 days) and decreased neointimal proliferation at 180 days in pigs.168 Neointimal hyperplasia was significantly lower for DLC-coated nitinol stents after implantation in a canine iliac artery model.169 Another class of diamond-like nanocomposite (DLN) stent coating showed reduced thrombogenicity and minimal neointimal hyperplasia in pigs. This coating when covered with another DLC showed enhanced inflammatory reaction without any added advantage, compared to single-layer DLN coating.170 Another fundamental study presented strong evidence for the influence of various material and processing parameters such as surface chemistry, nanotopography, and hydrophilicity, in mediating platelet adhesion as well as cell compatibility. Three different surface chemistries provided by amorphous hydrogenated carbon (C:H), Carbon Nanotube (CNT)/DLC, and titanium boron nitride (TiBxNy) thin films of ∼100 nm thickness, deposited by magnetron sputtering technique were compared. While the hydrophilicity and nanoscale roughness of C:H and TiBxNy films favorably influenced platelet behavior, the high roughness of CNT bundles and its hydrophobicity made the surface less thromboprotective.171 In another study, topography, stoichiometry, and surface properties were studied as the key parameters that regulate the thrombogenicity of a-C:H and titanium nitride (TiNx) nanocoatings developed by magnetron sputter deposition. By appropriate tuning of the deposition parameters (ion bombardment and content of hydrogen/nitrogen in plasma), the thrombogenic behavior of these nanocoatings could be tailored.172

Other inorganic coatings

As a biocompatible inert ceramic coating material for stents, iridium oxide has also been studied. The effect of the oxidation state of IrxTi1−x-oxide coatings formed on Ti substrate by thermal method showed a significant reduction in platelet adhesion and activation, rendering the surface blood compatible. Moreover, a substantial improvement in the ratio of EC/SMC count was also observed.173 Similarly, the antithrombogenic properties of amorphous silicon carbide (SiC) stent coating developed by chemical vapor deposition process could reduce the adhesion of platelets, leukocytes, and monocytes on the stent surface.174

Plasma coating using various materials has also been explored on coronary stents. Trimethylsilane (TMS) plasma coating of thickness 20–25 nm was formed on 316L SS coronary stents by direct current and radio frequency glow discharges, followed by an additional NH3/O2 plasma treatment. TMS plasma coatings imparted superior corrosion resistance to SS stents, thus hindering metallic ion release into the bloodstream.175 These coatings possessed good long-term chemical stability and displayed improved proliferation of ECs.176 SiCOH plasma nanocoatings of thickness 30–40 nm were also used to modify the surface of stents by low‐temperature plasma formed by a gas mixture of TMS and oxygen. This nanocoating showed excellent hemo‐ and cytocompatibility in vitro.177

Alumina coatings on stents have also been probed for their ability to impart antithrombogenicity and also as an inert layer that can inhibit metal ion leaching. Stents coated with sub-30 nm thick Al2O3 using plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition (ALD) displayed improved antithrombogenicity, without altering its mechanical properties.178 Likewise, alumina coatings of thickness 10–20 nm deposited on NiTi by ALD technique could effectively better the corrosion resistance of NiTi, and inhibit the release of Ni atoms, thus reducing the serious problems of nickel allergic reactions.179

Another coating that has been investigated on clinical stents is the bioceramic hydroxyapatite, which has also been utilized as a substrate for drug loading. Porous nanothin hydroxyapatite coatings on stents were found to be stable for more than 4 months, with an in vivo anticipated lifetime between 9 months and 1 year for the coating, during which time the loaded drug would get released completely. A similar coating on CC stents aided the elution of low doses of sirolimus, which inhibited platelet adhesion and activation in vitro.180

Nanothin polyphosphazene polymer-based coating

Similar to the inorganic coatings on stents, polymeric coatings of nanothickness have also been extensively investigated. Specifically, polyzene-F (PzF) surface coating has gained immense attention because of the multifarious characteristics of this polymer, which include its biocompatibility, anti-inflammatory, and inherent thromboresistance.181,182 These properties can potentially help to overcome the deficits of the current clinically used DES, in patients having bleeding risk. Extensive preclinical studies including vascular cell response and platelet adhesion, followed by in vivo testing in various animal models were carried out on CC stents with a nanoscale PzF coating of ∼50 nm thickness. This nanocoating unfailingly exhibited minimal platelet adhesion and clotting, reduced inflammation, and accelerated endothelial healing. PzF stents have also shown significantly lower neointimal thickening, reduced thrombogenicity,183 and rapid healing, with complete re-endothelialization in rabbits in 1 week itself.184 Similar were the results when implanted in a pig coronary artery as well.185,186 This coating showed superior endothelial coverage than commercially available DES. This polymer coating, as a result of its excellent preclinical response, has found its place in clinical trials.

Thus, the vast literature on nanostent coatings cited above clearly underlines the impact of nanotechnology in offering the primary requisite of an ideal coronary stent, viz., its in vivo biological response. Table I lists the diverse nanoarchitectures and coatings developed on clinical stents and their in vivo outcomes.

TABLE I.

Diverse nanostructures and thin-film coatings developed on stents which have been tested in various animal models.

| Type of surface on stents | Description | Development technique | Drug/biologics | Animal model | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanotubular structures | Titanium dioxide nanotubes (Ti stent) | Anodization | ⋯ | In vivo rabbit iliac artery | Enhanced endothelialization and minimal in-stent restenosis | 89 |

| Nanostructures | Titanium dioxide nanoleaves (SS stent) | TiO2 sputter deposition followed by hydrothermal | ⋯ | In vivo rabbit iliac artery | Reduction of neointima and complete endothelialization | 102 |

| Nanoflaky MgF2 film (Mg–Nd–Zn–Zr stent) | Chemical conversion treatment | ⋯ | In vivo rabbit abdominal aorta | Complete endothelial lining with minimal thrombogenicity and restenosis | 110 | |

| VSMC biomimetic patterns (SS stent) | Femtosecond laser processing | ⋯ | In vivo rabbit iliac artery | Rapid re-endothelialization in thirty days | 121 | |

| Ta implanted nanoridges (CC stent) | Target-ion-induced plasma sputtering | ⋯ | In vivo rabbit iliac artery | Minimal neointimal hyperplasia and rapid re-endothelialization | 125 | |

| Nanosized silicone filament (CC stent) | Anti-CD164 antibody | In vivo porcine coronary artery | Improved selective EPC capture resulting in rapid endothelial healing in 1 week | 129 | ||

| Nanoporous alumina (SS stent) | Physical vapor deposition of aluminum followed by electrochemical conversion | Tacrolimus | In vivo rabbit iliac artery | Inhibited neointimal proliferation | 131 | |

| In vivo porcine coronary artery | Particle debris resulting from the cracking of ceramic coating during stent expansion resulted in increased neointimal growth and stenosis | 132 | ||||

| Nanoporous structures (SS stent) (Lepu Medical Technologies, China) | Electrochemical method to generate pores | Sirolimus and anti-CD34 antibody/anti-CD34 alone | In vivo porcine coronary artery | Endothelialization in 2 weeks with minimal restenosis | 135, 136 | |

| CREG gene | Accelerated endothelium in 4 weeks | 137 | ||||

| Rapamycin and probucol | As safe as BMS and SES without any significant enhancement in re-endothelialization | 138 | ||||

| Nano-thin-film coatings | Titanium nitride coating (SS stent) | Reactive physical vapor deposition | ⋯ | In vivo porcine coronary artery | Reduced neointimal hyperplasia | 147 |

| Ti–O film (CC stent) | Magnetron sputter deposition | ⋯ | In vivo rabbit abdominal aorta | Faster rate of endothelialization | 151 | |

| Titanium nano-thin-film coating (SS stent) | Sol-gel processing | ⋯ | In vivo porcine coronary artery | Non-inferior to BMS | 154 | |

| Copper-doped TiO2 nanofilms (Ti wire) | Sol-gel spin-coating | ⋯ | In vivo Rat abdominal aorta | Reduced neointimal hyperplasia and re-endothelialization in 4 weeks | 156 | |

| TiO2 thin films (CC stent) | Plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition | Heparin | In vivo porcine coronary artery | Reduced neointima, inflammation and fibrin deposition | 157 | |

| Abciximab/alpha lipoic acid | Effective reduction of in-stent restenosis and accelerated re-endothelialization | 158 | ||||

| Abciximab and Kruppel-like factor 4 gene | Reduced neointimal thickening and faster endothelialization | 159 | ||||

| Nitrogen-doped TiO2 thin films | Plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition | Tacrolimus | In vivo porcine coronary artery | Reduced in-stent restenosis and increased endothelial formation | 160 | |

| Everolimus | Decreased neointimal thickening and thrombosis with faster healing | 161 | ||||

| Nanothin TiO2 film (SS stent) | Radio frequency magnetron sputtering | REDV peptide | In vivo rabbit iliac artery | Reduced in-stent restenosis and promoted re-endothelialization | 162 | |

| Nanothin DLC (CC stent) | Physical vapor deposition | ⋯ | In vivo porcine coronary artery | Early and complete endothelial healing in 30 days and decreased neointimal proliferation at 180 days | 166 | |

| Nanothin DLC (NiTi stent) | Physical vapor deposition | ⋯ | In vivo canine iliac artery model | Significantly lower neointimal hyperplasia | 167 | |

| Nanothin polyzene F coating (CC stent) | Deposited from a solution and subsequently dried | ⋯ | In vivo rabbit iliac artery | Rapid healing in 1 week | 182 | |

| In vivo porcine coronary artery | Complete endothelial coverage and reduced neointimal hyperplasia and inflammation | 183, 184 |

Nanofibrous systems

Nanofibers (NF) have unique advantages as coating materials for cardiovascular stents on account of their nanoscale diameter, tunable surface morphology, flexibility, porosity, and higher length/diameter ratio. The large surface area to volume ratio of NFs permits them to be good platforms for incorporation of drugs/biologics with high drug loading.187 Nanofibrous matrix covered biomedical implants thus facilitate localized drug-eluting platforms, which provide sustained release of different kinds of drugs (anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic, antirestenotic) for prolonged durations at required doses188 and protect the vessel wall from direct metal contact.189 This can in turn help to reduce late stent thrombosis and restenosis risks, akin to the commercial DES. More predictable laminar flow also results from nanofiber-coated stents, thus reducing the probability of restenosis,190,191 but there is experimental and clinical evidence demonstrating that the covering of BMS with drug eluting polymers results in increased stent stiffness and thus modifies the mechanical properties of the stent platform,192 which needs to be addressed.

Fibrous polymeric nanoplatforms as coatings on BMS are commonly fabricated through a simple and cost-effective technique of electrospinning.193,194 This is a voltage-driven fiber production process, which uses electric force to draw charged threads of polymer solutions up to fiber diameters in the order of hundreds of nanometers.45,195,196 Diverse biodegradable polymeric materials [e.g., poly-L-lactic acid (PLA), poly(caprolactone) (PCL), poly-lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA), chitosan (CS)], and drugs have been studied as candidates for developing nanofiber-coated stents. For example, chitosan/β-cyclodextrin nanofibers loaded with simvastatin, a drug commonly used for restenosis prevention, was developed by electrospinning to cover a self-expandable NiTi stent. Drug release time was extended by altering the duration of electrospinning and blending with cyclodextrin in the NF matrix. A dose-dependent effect on vascular cells was observed using these NF-coated stents, with EC viability affected less than SMC in the presence of the drug.197 The same technique was extended to polymeric stents of PLA, wherein the stents were coated with NFs of PLA/chitosan, eluting the drug paclitaxel at different concentrations. This NF-coated stent offered controlled drug release in vitro and displayed effective cytotoxicity to normal fibroblast cells in culture.198 Chitosan/PLGA-PLA nanofibers incorporating β-estradiol in Eudragit nanoparticles were developed as electrospun coatings on metallic stents, which provided high endothelial proliferation rate and enhanced NO production. Moreover, these NFs also alleviated reactive oxygen species induced toxicity to ECs in vitro.190 Another stent coating studied is the nanofibrous matrix made from a blend of PCL, human serum albumin, and paclitaxel having a coating thickness of 150–180 μm and fiber diameter of ∼500 nm. After implantation in the rabbit iliac artery, these stents were less traumatic and induced weaker neointimal growth over 6 months, with increased blood flow as against that of BMS.199 Nanoscale cellulose acetate fibers containing rosuvastatin and heparin were developed and loaded on three different commercially available stents (SS, CC, and NiTi). This hybrid DES provided local and sustained delivery of high concentrations of the two drugs for 4 weeks, presenting a novel therapeutic method for patients who have a high risk of stent thrombosis, with minimal systemic side effects.200 Propylthiouracil (PTU), an antithyroid drug proven to suppress neointimal formation, was incorporated within biodegradable PLGA nanofibers with fiber diameter ranging from 112 to 622 nm and coated on BMS. These stents showed improved EC proliferation and migration, with increased NO production and eNOS activation, along with reduced platelet adhesion. A sustained release of PTU for 3 weeks, with a marked reduction in neointima formation and enhanced re-endothelialization, was observed in the injured aorta in rabbits.201 A blood-compatible nanofiber scaffold was developed using mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) embedded PCL/gelatin electrospun nanofibers, for controlled dual delivery of 2-O-d-Glucopyranosyl-l-Ascorbic Acid (AA-2G) and heparin. Controlled release of AA-2G prevented initial oxidation and inflammation of blood cells, and the simultaneous release of heparin rendered long-term antithrombotic potential in vitro. Subcutaneous implantation in rats proved its biocompatibility and resistance to inflammation and thrombosis.202 Controlled and localized delivery of dipyridamole (DIP), a platelet aggregation inhibitor, using electrospun PCL scaffold has also been proposed as a stent coating. The released DIP accumulated in ECs without causing cytotoxicity, but inhibited EC proliferation in vitro, while concurrently increasing the gap junction coupling of ECs, which is a primary requirement in maintaining normal vascular physiology.203 In another study, PLA nanofibrous scaffolds consisting of DIP were developed by electrospinning as a cytocompatible coating for Co/Ni stents. Pharmacokinetics of the PLA/DIP nanofibers showed an initial burst, followed by a slow and controlled release for 7 months.204 Sustained and localized delivery of ticagrelor for about 4 weeks was achieved in vivo via the use of electrospun PLGA nanofiber coating on Gazelle stents. These stents reduced neointimal formation and favored endothelial recovery with lesser vasoconstrictor response and improved NO-mediated vasorelaxation after implantation in rabbit abdominal aorta as shown in Fig. 5.205 Likewise, PLGA nanofiber membrane-coated bare-metal SS stents were developed as a local and sustained delivery depot for acetylsalicylic acid. The electrospun PLGA/acetylsalicylic acid nanofibers had a diameter ranging from 50 nm to 8 μm. This hybrid stent was highly effective as inhibitors of platelet and monocytes and promoted re-endothelialization in rabbit denuded artery. NFs induced very minimal inflammatory reaction and were completely absorbed in 4 weeks.206 Nanofibrous coatings of antihyperglycemic drug vildagliptin have been developed on Gazelle stents as a strategy to treat diabetic vascular disease. Stents with vildagliptin loaded PLGA nanofibers showed effective drug delivery for more than 28 days in the abdominal aorta of diabetic rabbits. This stent accelerated the revival of diabetic endothelia and also decreased neointimal hyperplasia and type I collagen content in the vascular intima than that of the non-vildagliptin-eluting group.207 Poly-L-lactide films cut and rolled into a cable-tie type stent were coated with rapamycin-eluting biodegradable nanofibers, which exhibited excellent mechanical properties and delivered high drug concentrations for over 4 weeks. Moreover, these stents showed a substantial reduction in intimal hyperplasia in denuded rabbit arteries during 6 months follow-up.208

FIG. 5.

(a) Bare-metal stent with a nanofibrous membrane coating. (b) SEM micrographs of the electrospun nanofibrous membrane with ticagrelor. Magnification of ×3000. (c) SEM images of platelets on electrospun ticagrelor eluting membrane. Red arrow indicates activated platelets (scale bars = 10 μm). Magnification 3000×. (d) Hematoxylin–eosin stained section of arterial lesions in ticagrelor group exhibiting a complete lining of endothelial cells (red arrows). (e) Pathological arterial lesions in the ticagrelor group stained using HES5 markers at 4 weeks following stent implantation. The amount of formed neointima suggests less proliferation of SMCs in the media. (f) SEM images of the stented vessel showing complete endothelial coverage in the ticagrelor group. Reprinted with permission from Lee et al., Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 6039–6048 (2018). Copyright 2018 Dove Medical Press.

Drug-loaded coaxial nanofibers have also been tried as stent coatings. A drug-eluting stent coated with PCL/PU blend coaxial nanofibers containing the drug paclitaxel (PTX) in PCL, with PCL as the core and PU blended PCL as the shell, has been studied for controlled drug release. PCL/PU nanofibers containing PTX inhibited the proliferation of SMCs in vitro.209 Likewise, paclitaxel/chitosan (PTX/CS) core-shell NFs have been developed on Ni-Ti stents through the co-assembly of paclitaxel and chitosan, with very high drug loading. This nanofibrous coating displayed better EC viability in vitro than the drug alone, due to the presence of CS outside the NFs, which prevented direct cell contact with the drug.210 Using a similar coaxial spinning, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)/gelatin nanofibers (with gelatin in the shell and PVA in the core of each nanofiber) were prepared as possible stent coating. This nanofibrous scaffold possessed the requisite biocompatibility (due to gelatin), mechanical strength, and stiffness (from PVA). It promoted EC migration and proliferation, with concurrent SMC inhibition.211 The same group also looked into the correlation between mechanical properties and hemocompatibility of this scaffold. It was observed that the increased stiffness of coaxial nanofibers resulted in higher rates of platelet activation and thrombin formation, in comparison with individual gelatin and PVA fibers, implying that mechanical stiffness and surface roughness are dominant factors that control platelet activity.212

Similar to drug-loaded stents, biological molecules have also been utilized for preparing nanofibrous coatings on stent materials. In one such study, a native endothelium extracellular matrix (ECM) mimicking self-assembled peptide amphiphile (PA) nanofibrous coating functionalized with fibronectin-derived EC-specific adhesion molecule, REDV, and mussel-adhesive protein inspired Dopa residue was formed on SS surfaces. REDV–PA was designed to enhance endothelial cell-specific activity and Dopa for immobilizing REDV-conjugated nanofibers on the stent surface. In vitro studies proved increased adhesion, spreading, and long-term viability of ECs, with significantly lower viability of SMCs.213 A similar endothelial ECM mimicking nanofibrous matrix was fabricated by self-assembly of PAs containing NO donating residues, EC adhesive YIGSR peptide ligands, and enzyme-mediated degradable sites (MMP-2). A rapid release, followed by a sustained release of NO from the nanofibrous matrix for over 30 days, promoted increased EC adhesion, proliferation and concurrently limited SMC proliferation, with a 150-fold reduction in platelet attachment.214 Similarly, functional peptide sequences containing enzyme-mediated degradable sites combined with either endothelial cell-adhesive ligands (YIGSR) or polylysine (KKKKK) nitric oxide (NO) donors were attached to the self-assembled PAs. Linkages of two different PAs (PA–YIGSR and PA–KKKKK) to pure NO helped to develop PA–YK–NO, which was self-assembled onto electrospun PCL nanofibers to fabricate a hybrid nanomatrix. NO release could trigger significant EC activity and suppress SMC and platelet adhesion, similar to the previous study.215 The same group could demonstrate mitigation of inflammation due to this NO release from PA-YK-NO stent coatings under static and dynamic physiological flow conditions in vitro.216 Table II summarizes those studies that have progressed to the in vivo (small animal) stage.

TABLE II.

Bare-metal stents coated with electrospun nanofibers tested in vivo.

| Type of coating | Description | Active agent | Animal model | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospun nanofibrous coatings | PCL and human serum albumin | Paclitaxel | In vivo rabbit iliac artery | Induced weaker neointimal growth over 6 months | 197 |

| PLGA nanofibers on BMS | Propylthiouracil | In vivo rabbit injured aorta | Reduced neointimal hyperplasia and enhanced re-endothelialization | 199 | |

| PLGA nanofibers on BMS | Ticagrelor | In vivo rabbit abdominal aorta | Minimal neointimal formation and favored endothelial recovery | 203 | |

| PLGA nanofibers on SS stents | Acetylsalicylic acid | In vivo rabbit denuded artery | Promoted re-endothelialization | 204 | |

| PLGA nanofibers on BMS | Vildagliptin | In vivo rabbit abdominal aorta | Accelerated endothelial recovery and decreased SMC hyperplasia | 205 | |

| poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) cable tie type stents | Rapamycin | In vivo rabbit denuded artery | Reduced neointimal hyperplasia | 206 |

Despite the significant efforts undertaken on nanofiber-coated stents demonstrating controlled drug/biologics release and synchronized cell response in vitro, research in this direction has not progressed further to the preclinical (large animal) or clinical stages. The stability and durability of these nanofibrous coatings upon stent expansion and crimping are important aspects that need to be assessed before proposing it for clinical translation.

Nanoparticulate systems

Nanoparticulate drug delivery systems are bestowed with significant benefits that can be readily capitalized in the cardiovascular field.217 This includes the possibility of target-specific drug delivery, enhanced intracellular uptake and high bioavailability, reduced drug dosage with less toxicity in tandem, tunable, and sustained drug release, etc.218,219 Nanoparticles (NP) loaded with drugs, when incorporated onto stent platforms, facilitate improved release kinetics and also promote a spatiotemporal delivery at the site of intervention.220 Nanoparticle encapsulation may also allow higher arterial wall concentrations and residence times than traditional drugs, two important factors for the prevention of restenosis.49,219 Additionally, drug stability is improved when loaded within a NP and an effective drug release from stents into the abluminal wall can be attained. This in turn enhances the intracellular uptake and local bioavailability of the drug at the stented site.49,221 After localized delivery from the stent surface, nanocarriers can infiltrate the vessel wall and form a depot, which offers a locally limited and sustained drug release into the arterial wall,222 thereby preventing in-stent restenosis. Local delivery of drug loaded nanoparticles, combined with antibody targeting strategies, can also permit high concentration, sustained drug therapy, which is required to prevent restenosis.46,223

Numerous studies have focused on enhancing localized drug delivery within arteries using nanoparticle formulations on stent platforms. Most commonly used polymers as stent coating include the bioabsorbable polymeric matrices of poly-D, L-lactic Acid (PDLLA), PLGA, PLA, PCL, etc., due to their excellent in vivo-biocompatibility.224 In one such study, sirolimus-loaded PDLLA nanoparticles exhibited good cellular and interstitial uptake as well as sufficient drug loading and revealed biphasic release kinetics with a short burst followed by a longer, slower release phase in vitro. However, these drug-loaded nanoparticles inhibited viability and proliferation of both EC and SMCs, although the nanodrug was less toxic to ECs compared to the free drug.225 A similar study in which bioresorbable PLLA stent surface was grafted with polyethylene vinyl acetate (PEVA) and PVP by plasma polymerization followed by coating with PDLLA nanoparticles carrying sirolimus displayed pronounced inhibition effect on SMCs than on ECs.226 Antirestenosis drugs, dexamethasone/rapamycin-loaded nanoparticles based on poly(ethylene oxide) and PLGA block copolymers, demonstrated a rapid burst release. This fast release kinetics was tuned by conjugating these nanoparticles with gelatin or albumin, which yielded a sustained release of dexamethasone and rapamycin for 17 and 50 days, respectively, after gelatin treatment.227 To address the problem of late stent thrombosis, an antiplatelet drug dipyridamole was loaded within PLA NPs, which showed a sustained drug release over 1 month in vitro.228 Stents coated with PLGA/chitosan nanoparticles containing a fluorescence marker (FITC) after 4 weeks of implantation in porcine coronary artery led to the specific uptake of these NPs by SMCs, yielding FITC fluorescence in the neointimal and medial layers of the stented artery in comparison with bare. However, the extent of neointima formation and re-endothelialization was comparable for the bare-metal and NP-eluting stents.229 This nanocarrier was utilized by the same group as a matrix for delivering various biomolecules/drugs. Imatinib mesylate [a platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor inhibitor] eluting PLGA/chitosan NPs attenuated the proliferation of SMCs associated with inhibition of the target molecule (phosphorylation of PDGF receptor-β), but showed no effect on EC proliferation in vitro. This observation was well reflected in vivo wherein a marked reduction (by 50%) of in-stent neointima formation and stenosis was observed, without any effect on re-endothelialization in pigs.230 Similarly, Pitavastatin loaded PLGA/chitosan NPs were as effective as the bare drug in inhibiting SMC proliferation and tissue factor expression even at very low doses. These NP eluting stents significantly reduced in-stent stenosis in a porcine model and also elicited endothelial healing effects for re-endothelialization of stented arteries.231 In vivo efficacy of a polymer-free stent that utilizes nanosized phospholipid particles to deliver sirolimus from a combined balloon-plus-stent platform was compared with a BMS and biolimus eluting stent in a porcine coronary model. Results revealed a larger lumen area with reduced neointimal thickness and stenosis, with completely covered stent struts after 28 days.232

Researchers have also probed into ways of selective targeting of drug/biologics to SMCs or ECs. Gene-eluting stents were developed to deliver Akt1 siRNA nanoparticles (ASNs) from a hyaluronic acid (HA)-coated stent surface to specifically suppress the pro-proliferative Akt1 protein in SMCs. This stent released Akt1 siRNA to the SMCs attached to the stent, thereby reducing cell proliferation in the implanted vasculature and also in-stent restenosis in a rabbit iliac artery model.233 A gene and drug co-delivering SS coronary stent coated with bi-layered PLGA NPs containing a VEGF plasmid in the outer layer and PTX in the inner core was developed. These stents could promote early endothelium healing and inhibit smooth muscle cell proliferation in the porcine coronary injury model.234 In another study, the possibility of using chitosan/PLGA NPs containing miR-126 dsRNA for efficient incorporation into ECs was investigated. These NPs enhanced EC proliferation and migration appreciably, while SMC proliferation was reduced in vitro. Implantation of stents coated with chitosan-modified PLGA NPs containing dsRNAs in a rabbit restenosis model significantly inhibited the progression of neointimal hyperplasia.235 Likewise, a substrate-mediated gene delivery system was prepared by using bioinspired PDA coating to which DNA complex nanoparticles, composed of protamine (PrS) and plasmid DNA encoding with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF-pDNA) gene, were immobilized. EC proliferation was specifically promoted due to HGF, with less influence on SMC growth.236 A nanobioactive stent platform was developed containing multiple angiogenic genes (VEGF and Ang1) carrying NPs entrapped in polyacrylic acid (PAA) functionalized CNTs and fibrin hydrogel. The developed stent coating could significantly reduce the loss of therapeutics while traversing through the vessel and during deployment, and showed significantly enhanced endothelial regeneration and inhibition of subsequent neointimal proliferation in vivo.237

Heparin, an antithrombotic agent, has been utilized for developing nanocarriers that encapsulate drugs/biologics, with supplemented targeting functionality, as stent coatings. VEGF-loaded heparin/poly-l-lysine nanoparticles immobilized on dopamine-coated SS surfaces indicated enhanced blood compatibility with reduced platelet adhesion and activation, SMC inhibition, and significantly improved EC response.238 The same group developed a biomimetic nanocoating of laminin loaded heparin/poly-L-lysine nanoparticles, which prevented platelet adhesion and thrombus formation and showed beneficial effects in promoting EC proliferation.239 These nanoparticles were also loaded with fibronectin in another study to enhance the anticoagulant properties of the surface and demonstrated effective improvement in EC adhesion and proliferation.240 A multifunctional endothelium mimicking coating was built by cystamine-modified heparin/polyethylenimine (PEI) nanoparticles immobilized on the polydopamine surface. Active heparin along with in situ NO generation by the cystamine moieties in NPs resulted in good anticoagulant activity, along with a significant inhibition of SMC proliferation, promotion of EC proliferation, and tissue safety after subcutaneous implantation in rats.241 Similarly, a stent coating was developed by grafting Hep/NONOates onto SS stent surface. Synergistic and complementary effects of the released heparin and NO resulted in superior blood compatibility and promoted re-endothelialization with a subsequent reduction in in-stent restenosis, after implantation in the atherosclerotic rabbit model as shown in Fig. 6.242 Heparin coating has also been explored for its potential to minimize ion leaching from stents. Chitosan-heparin nanoparticle-coated nitinol nanotube surface helped to reduce Ni ion release and offered improved EC response. The initial burst release of heparin followed by its slow and sustained release also yielded improved blood compatibility.243

FIG. 6.

SEM images of (a) heparin/NONOate nanoparticles immobilized on polyglycidyl methacrylate (PGMA)-coated SS stents. Strut coverage on (b) SS-PGMA-Hep/NONOates and (c) control 316L SS stents harvested at 1 month. Histological hematoxylin−eosin stained images of (d) SS-PGMA-Hep/NONOates and (e) 316L SS stent after implantation for 1 month (arrows point to the higher magnification images). Reprinted with permission from Zhu et al., Langmuir 36, 2901–2910 (2020). Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.