Abstract

Background:

Metastatic breast cancer (MBC) is not curable and there is a growing interest in personalized therapy options. Here we report molecular profiling of MBC focusing on molecular evolution in actionable alterations.

Experimental design:

Sixty-two patients with MBC were included. An analysis of DNA, RNA and functional proteomics was done, and matched primary and metastatic tumors were compared when feasible.

Results:

Targeted exome sequencing of 41 tumors identified common alterations in TP53 (21; 51%), PIK3CA (20; 49%), as well as alterations in several emerging biomarkers such as NF1 mutations/deletions (6; 15%), PTEN mutations (4; 10%), ARID1A mutations/deletions (6; 15%). Among 27 hormone receptor-positive patients, we identified MDM2 amplifications (3; 11%), FGFR1 amplifications (5; 19%), ATM mutations (2; 7%), and ESR1 mutations (4; 15%). In 10 patients with matched primary and metastatic tumors that underwent targeted exome sequencing, discordances in actionable alterations were common, including NF1 loss in 3 patients, loss of PIK3CA mutation in 1 patient, and acquired ESR1 mutations in 3 patients. RNA-seq in matched samples confirmed loss of NF1 expression with genomic NF1 loss. Among 33 patients with matched primary and metastatic samples that underwent RNA profiling, 14 actionable genes were differentially expressed, including antibody drug conjugate targets LIV-1 and B7-H3.

Conclusion:

Molecular profiling in MBC reveals multiple common as well as less frequent but potentially actionable alterations. Genomic and transcriptional profiling demonstrates intertumoral heterogeneity and potential evolution of actionable targets with tumor progression. Further work is needed to optimize testing and integrated analysis for treatment selection.

Keywords: breast cancer, metastasis, gene expression, molecular evolution, actionable targets

Introduction

Breast cancer is a major cause of cancer death in women throughout the world (1). Locoregional recurrence (LRR), recurrence of tumor in the ipsilateral breast, chest wall, or regional lymph nodes, is potentially curable, but is associated with a high risk of distant metastasis (DM) (2,3). DM, the recurrence of cancer in distant parts of body is considered treatable, but unfortunately usually not curable. The American Cancer Society reports 5-year relative survival rates for localized versus DM breast cancer as 99% and 27%, respectively (4). Therefore there is a great need to better understand the biology of metastatic disease, and to identify novel therapeutic targets and strategies for treatment selection.

There is great interest in personalizing cancer therapy through molecular profiling especially next generation sequencing (NGS) to identify “actionable alterations”, alterations that impact the function of drivers of tumor cell growth, survival or progression that can be directly or indirectly targeted with approved or investigational agents. Genomic alterations have been shown to have therapeutic implications across all three breast cancer subtypes. Human epidermal receptor 2 (HER2)-positive tumors are defined by the amplification of HER2 (ERBB2 gene) and/or HER2 overexpression. In HER2+ tumors, coalterations such as PIK3CA mutations or low PTEN have been shown to impact the therapeutic efficacy of certain HER2-targeted regimens (5). Recently the PI3Kα-specific inhibitor alpelisib was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in combination with fulvestrant for patients with PIK3CA-mutated HR+ advanced breast cancer. Targeting several other genomic alterations such as mutations in AKT1, PTEN and HER2 have shown therapeutic potential (6–9). In triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), Akt inhibitors enhanced chemosensitivity of paclitaxel in patients with PI3K/Akt/PTEN altered tumors (10,11). In addition, protein based biomarkers, specifically PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry has been able to assist in selecting benefit from checkpoint inhibitors atezolimuzumab and pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy in TNBC (12,13). Germline alterations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have already been associated with a benefit in progression free survival with the use of PARP inhibitors (14,15). There is also data to suggest benefit from PARP inhibitors in somatic BRCA mutations and germline PALB2 mutations (16). We and others have found that TP53 is a significantly mutated gene in all three breast cancer subtypes, and TP53 mutations are associated with poorer recurrence-free survival, progression-free survival and overall survival (17).

In clinical practice, genomic profiling for metastatic breast cancer (MBC) treatment selection is often done on the available tumors, which may be an archival tumor specimen from the surgical resection of the primary breast cancer. However, recent studies have shown that metastases may not show the same genomic alterations as their matched primaries (18) and treatments can lead to clonal expansion forcing new activating mutations (19,20). Enrichment of these mutations in metastatic tumors may promote acquired resistance and acceleration of metastasis. ESR1 mutations are almost exclusively detected in patients with metastatic disease after endocrine therapy in the adjuvant or metastatic setting (21), and may differentially benefit from different endocrine therapies (22). We have reported an enrichment of NF1 mutations in breast cancer patients with LRR and DM, with acquisition of NF1 mutations in some patients (23). Recently somatic NF1 loss was shown to activate Ras/MAPK pathway and confer resistance to endocrine therapy. The combination of MEK inhibitors with endocrine therapy was shown to have efficacy in ER+ preclinical models with NF1 mutations. These data suggest that understanding emerging alterations in the breast cancer metastasis might help optimize treatment options.

There is growing interest in using transcriptional profiling to identify additional therapeutic targets. With the recent FDA approval of antibody drug conjugates (ADC) with TROP2 and HER2, ADCs are emerging as an exciting drug class. Although these agents target proteins on the cell surface, many of these targets were initially identified through their high RNA expression on tumor profiling studies. For many of these targets, little is known about the evolution of their expression with tumor progression.

In this study we sought to determine the molecular profile of metastatic breast tumors, with a focus on actionable alterations. We performed integrated analysis of DNA, RNA and protein as well as comparison of matched primary vs metastasis when feasible.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

Sixty-two patients with metastatic breast cancer treated at the MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) that had tumor samples available for DNA, RNA and/or proteomic analysis were included in the study. Fifty-seven patients had paired primary tumor samples and metastatic tumor biopsies. Clinico-pathological information was obtained by a retrospective review of patient records. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center approved the study. This study was conducted in accordance to the U.S. Common Rule. Patients gave written informed consent for either prospective tumor collection and/or retrospective analysis of their archival samples. Clinical data were collected retrospectively from electronic medical records.

We obtained archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections of 51 primary and 27 metastatic breast cancer samples. For all cases, hematoxylin and eosin stained slides were reviewed by breast pathologist to verify the histologic diagnosis and select the sections with tumor. In addition, 38 fine-needle aspiration biopsies (FNAs) of metastatic and recurrent tumors were obtained. FNAs were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. A corresponding normal blood sample was submitted as normal comparator for all FNAs. Thirty-five samples had matched tumor-normal. In 25 samples targeted exome sequencing was performed without matched normal tissue. Four patients had two metastatic samples.

DNA sequencing

DNA extraction, library preparation, target enrichment, sequencing, and variant calling were performed on all samples following a validated protocol as previously described (24). Sequencing was performed on hybrid capture platform T200.V1 consisting of 262 genes (Supplementary Table S1).

RNA sequencing

For cases with limited yield, RNA sequencing was prioritized over DNA sequencing. RNA extraction, cDNA and library preparation, target enrichment, and sequencing were performed on all samples following a validated protocol as previously described (23).

Analysis of actionable genes and the actionable transcriptome

A gene was considered actionable if there are clinically available therapies that directly or indirectly target alterations in the gene and/or there are clinical trials selecting for alterations in the gene as previously described (Supplementary Table S2) (25–27). The actionable transcriptome was defined as the expression of actionable genes (oncogenes/tumor suppressor genes) as well as targets of antibody drug conjugates and selected genes involved with drug metabolism (Supplementary Table S3) (manuscript in preparation).

Proteomic profiling

Thirty-four metastatic samples were evaluated by reverse phase protein arrays (RPPA). Fine-needle biopsy samples were obtained and snap frozen immediately. RPPA was done in the MD Anderson Cancer Center Functional Proteomics Reverse Phase Protein Array Core Facility as described previously (28). The panel had 295 antibodies (Supplementary Table S4). PI3K pathway activity score was defined as the sum of the normalized values of the phospho-protein levels of Akt, 4E-BP1, S6K, and S6 (i.e., PI3K score = p-S6 S240/244 + p-S6 S235/236 + p-S6K T389 + p-4E-BP1 S65 + p-4E-BP1 T37/46 + p-mTOR S2448 + p-PRAS40 T246 + p-AKT S473 + p-AKT T308) (29). Samples were considered PI3K activated if their PI3K scores were in the top quartile (29).

Statistical and bioinformatics analysis

The association between genetic alterations and the most recent molecular subtype was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. Gene expression in amplified/mutated and not amplified/wild-type genes was compared by t test. Gene expression in matched primary tumors and metastasis were compared by paired t test. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

We aligned the T200 target-capture deep-sequencing data to human reference assembly hg19 using BWA (30) and removed duplicated reads using Picard (31). We called single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small indels using an in-house developed analysis pipeline (24), which classified variants into three categories: somatic, germline, and loss of heterozygosity based on variant allele frequencies in the tumor and the matched normal tissues. We called copy number alterations using a previously published algorithm (32), which reports gain or loss status of each exon. To understand the potential functional consequence of detected variants, we compared them with dbSNP, COSMIC (33), and TCGA databases, and annotated them using VEP (34), Annovar (35), CanDrA (36) and other programs. For Paired T200 samples variants that were only detected by ClinSek (37) and had an allele frequency less than 10% were filtered. Unpaired T200 used a pooled normal sample to use the paired T200 pipeline. In addition recurrent variants of unpaired samples were filtered out and then we filtered out more variants based on COSMIC_EXACT_MATCH, 1000 genome MAF and ESP6500 MAF. A deletion was defined as a loss of copy number less than or equal to 0.6. An amplification was defined as a gain of copy number greater than or equal to 5.

The RNA-seq read counts were normalized with “DESeq2” (38). Boxplot, unsupervised hierarchical clustering, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and heatmap for most variant genes were used for quality assessment. The read counts were fitted with a negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) and tested with Wald statistics. Variance stabilizing transformation (VST) was used in visualization, clustering and PCA analysis. VST is the transformed data on the log2 scale which has been normalized with respect to library size or other normalization factors. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified with a specified FDR.

Results

Patient and sample characteristics

Sixty-two patients with MBC and primary and recurrent/metastatic tumor tissue available were included in the study. Supplementary Table S5 summarizes their clinico-pathological characteristics. The primary breast cancers were mainly HR+ (84%), followed by TNBC (10%) and HER2+ (6%). The molecular subtype was discordant between the primary tumor and recurrence for eight pairs (13%). Six patients had HR+ primary tumors, whereas metastasis was TNBC. One HER2+/ER+/PR+ primary tumor was converted to HR+ and was no longer HER2+.

Genomic alterations in patients with metastatic breast cancer

Targeted exome sequencing was performed on the T200.1 deep targeted sequencing platform on 60 breast cancer samples from 41 patients with MBC. Of these samples, 17 were primary, 6 were LRR and 37 were DM samples. Alterations found in at least five samples are listed in Supplementary Fig. S1. Mutations were identified in several cancer-related genes. Focally amplified genes (>5 copies) included NOTCH1, CCND1, ORAOV1, PREX2, WHSLC1L1, FGFR1, LETM2, ANO1, FADD, RPS6KB1, and TUBD1. This list contains regions with copy number gains: WHSLC1L1 and FGFR1 on 8p11.23, ANO1 and FADD on 11q13.3, and RPS6KB1 and TUBD1 on 17q23.1. HR+ tumors, compared to the whole dataset, had similar mutation and amplification profiles, however, there were fewer deletions (< 0.6 copies). Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2B show alteration profiles and frequencies of HR+ patients.

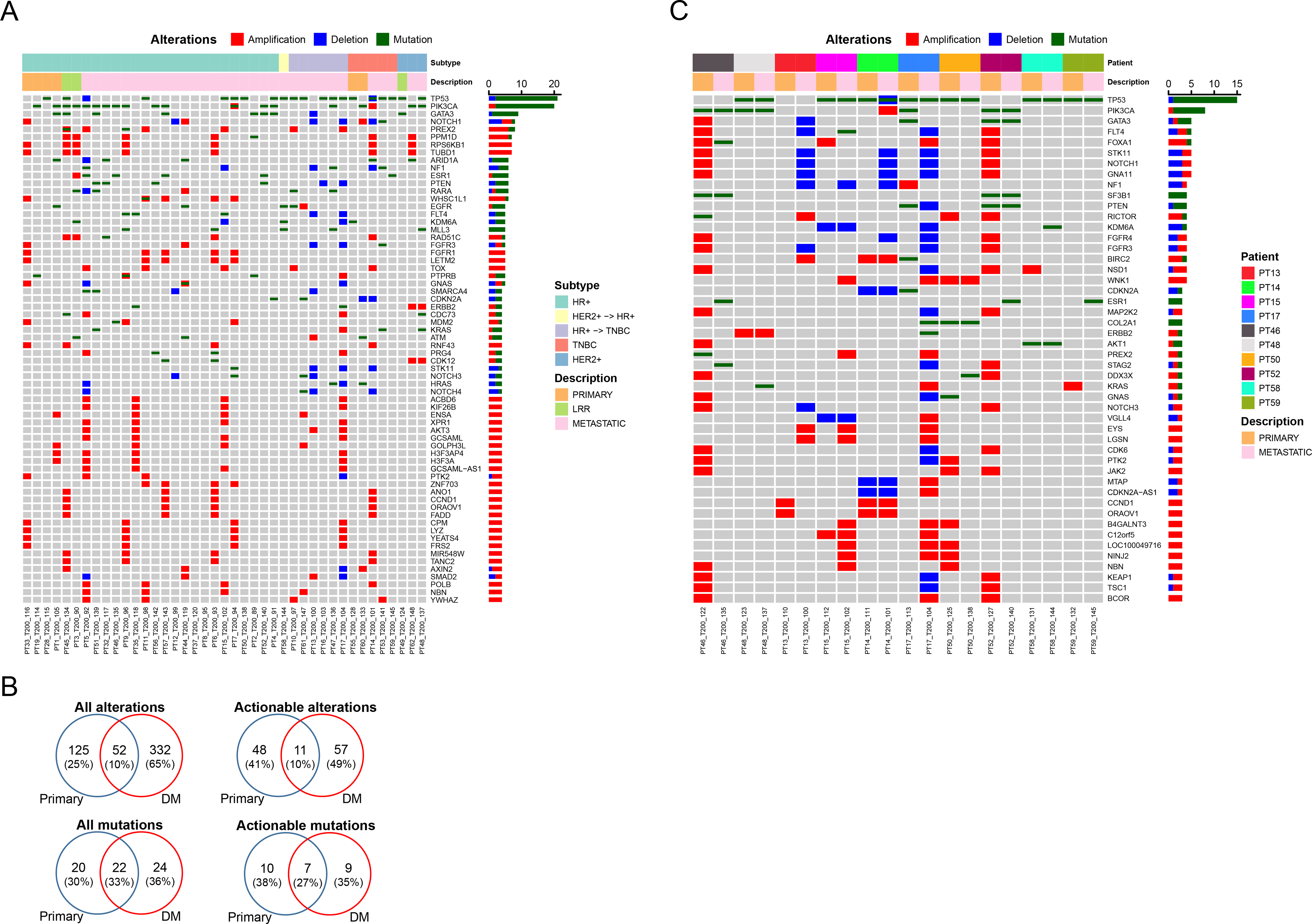

We focused on the 41 most recent samples for each patient and 32 of these samples were metastatic. The average number of alterations per tumor was 23 (median 13, range 0–176) and one patient tumor did not have any alterations (PT_T200_95). Fig. 1A demonstrated alterations in 66 genes, representing genes altered in at least four samples. Twenty tumors (49%) had 21 TP53 alterations, two copy number losses and 19 mutations. TP53 alterations were significantly associated with tumor subtype and were found in 82% of TNBC and 30% of HR+ samples (p = 0.0049). Nineteen tumors (46%) had 20 PIK3CA alterations, two amplifications and 18 mutations. PIK3CA mutations were found in 52% of HR+ and 18% of TNBC samples (p = 0.0776). This patient population was drawn from patients undergoing research biopsies, potentially leading to an enrichment of PI3K pathway alterations. Nine tumors (22%) had GATA3 alterations, one deletion and eight mutations. GATA3 mutations were observed in 26% of HR+ and 33% of HER2+ samples but none of the TNBC tumors.

Figure 1. Genomic alterations in primary, locoregional recurrence (LRR), and metastatic breast tumors.

(A) Genomic alterations in primary, LRR and metastatic tumors are shown. Each column represents a single tumor sample. Each row represents an individual gene. The samples were aligned by tumor subtypes (HR+/HER2+ -> HR+/HR+ -> TNBC/TNBC/HER2+) and location (primary/LRR/metastatic). The genes that were altered in at least four samples were shown. Bar graphs on the right summarize the number of alterations. (B) Venn diagrams showing all alterations, actionable alterations, all mutations, and actionable mutations in primary and DM. (C) Genomic alterations in paired primary and metastatic tumors are shown. Each column represents a single tumor sample. Each row represents an individual gene. The paired samples were aligned by patient and location (primary/LRR/metastatic). The genes that were altered in at least three samples were shown. Bar graphs on the right summarize the number of alterations.

There were several other genes that are involved in breast cancer. Eight tumors (20%) had NOTCH1 and seven tumors (17%) had PREX2 alterations. Seven tumors (17%) had both RPS6KB1 and TUBD1 amplifications. These latter two genes are both located on 17q23.1, and there increased copy numbers were reported to be associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis (39). Several tumors had alterations in less frequently altered genes but that are potentially actionable genes in the context of precision oncology. Six tumors (15%) had ARID1A alterations, including one deletion. Two of the five mutations were inactivating. Six tumors (15%) had NF1 alterations, three mutations and three deletions. One mutation was inactivating. Six tumors (15%) had ESR1 alterations, one amplification and five mutations. All ESR1 mutations were in metastatic samples and clustered in the ligand binding domain (40). Interestingly, one ESR1 mutation was detected in a TNBC who had not received prior endocrine therapy. Six tumors (15%) had PTEN alterations, four mutations and two deletions. Three mutations were inactivating. Five tumors (12%) had six EGFR alterations, five mutations and one amplification. Functional significance of the mutations were unknown. Nine tumors (22%) had 10 FGFR alterations. Five tumors (12%) had FGFR1 amplifications, and there were two FGFR3 amplifications (including one tumor with both FGFR1 and 3 amplification), two deletions and one mutation. All FGFR1/3 amplifications were in HR+ tumors. Four tumors (10%) had CDKN2A alterations, two deletions and two mutations that might cause a deleterious effect. Four tumors (10%) had KRAS alterations, one amplification and three mutations of which two were hot spot mutations in codon 12. Three tumors (7%) had MDM2 amplifications. Three tumors (7%) had inactivating ATM mutations. Three tumors (7%) had STK11 deletions. TP53, PIK3CA, FGFR1, GATA3, CCND1, CDKN2A, PTEN, ARID1A, NF1, KRAS, and STK11 have already been reported to be among the most frequently altered genes in breast cancer and previously defined as drivers (41,42). Looking at HR+ tumors only, in the 27 HR+ tumors there was meaningful alteration frequency of several potential clinically relevant targets/biomarkers including FGFR1 amplification (5 patients; 19%), PTEN mutation (4; 15%), ESR1 mutation (4; 15%), MDM2 amplification (3; 11%), ATM mutation/deletion (2; 7%), and NF1 mutation/deletion (2; 7%).

Genomic alterations in matched primary and DM tumors

First, we looked at genomic alterations in all HR+ primary, LRR and DM tumors. There were 11 primary, 5 LRR and 30 DM samples. In primary, LRR, and DM samples, we detected 185, 405 and 382 genomic alterations, respectively. Then we compared primary vs LRR, primary vs DM, and LRR vs DM groups. For each gene we created a contingency table by counting the number of altered samples primary or LRR or DM tumors. A two tailed Fisher’s exact test did not identify any differentially altered genes in all three comparisons.

Next, we looked at paired samples. Ten patients had matched primary and DM with targeted exome sequencing. We counted the number of alterations and mutations appearing in primary samples only, DM samples only, and both primary and DM samples. There were 445 genes on the panel and 339 (76%) genes had at least one alteration; 10% of the alterations were concordant (Fig. 1B). We repeated this analysis focusing on alterations in actionable genes only (Supplementary Table 2). Of the 80 actionable genes on the panel, 57 (71%) genes had at least one alteration; 10% of the actionable alterations were concordant (Fig. 1B). Of the 127 genes on the panel, 49 (38%) genes had at least one mutation; 33% of the mutations were concordant (Fig. 1B). Of the 55 actionable genes in the panel, 26 (47%) genes had at least one mutation; 27% of the mutations in the actionable genes were concordant (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1C shows the genes that were altered in least three samples in paired primary and DM tumors. Seven patients had TP53 mutations in their paired samples. Three patients had PIK3CA mutations in their paired samples and notably one lost the PIK3CA mutation in DM tumor while one of the patients gained an amplification. Three patients had gained ESR1 mutations in their DM.

Two patients had several amplifications detected in the primary tumor but not in the DM (PT46_T200_122 primary vs. PT46_T200_135 DM, PT52_T200_127 primary vs. PT52_T200_140 DM). One patient had a mixed pattern, lost mutations and gained deletions and amplifications (PT17_T200_113 primary vs. PT17_T200_104 DM). In all three of these patients the primary and DM had shared mutations confirming that indeed they were matched pairs. However, patient 13 (PT13) had no common alterations between the primary and DM (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Comparison of genomic alterations with external datasets

We compared our genomic data from 41 patients (MDA) and their most recent samples, with the Cancer Genome Atlas Breast Invasive Carcinoma (TCGA-BRCA) and the Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC) (43) datasets, focused on patients with primary breast cancer. In this series data, there were 241 altered genes, out of which 118 were mutated. The TCGA-BRCA dataset had 963 primary tumor samples. The METABRIC dataset had 2509 samples with mutation data and 2173 samples with both mutation and copy number alteration (CNA). The mutation data included 173 genes. There were 23 genes in our series that had alterations in at least five samples (Supplementary Table S6). TCGA-BRCA and METABRIC databases included 22 and 9 of these genes, respectively. There were 23 genes in our list that had mutations in at least three samples. TCGA-BRCA and METABRIC databases included 22 and 14 of these genes, respectively. In both alteration and mutation comparisons, TP53, PIK3CA, and GATA3 ranked top three in all lists.

In our data, there were 27 HR+ patients and their most recent tumors had 289 altered genes, of which 92 were mutated. TCGA-BRCA and METABRIC datasets had 400 and 1413 patients with HR+ tumors, respectively. There were 11 genes in our series that had alterations in at least five samples (Supplementary Table S6). TCGA-BRCA and METABRIC databases included 11 and 3 of these genes, respectively. There were 11 genes that had mutations in at least three samples. TCGA-BRCA and METABRIC databases included 10 and 7 of these genes respectively. In both alteration and mutation comparisons, PIK3CA, TP53 and GATA3 ranked top three in all lists.

Whole transcriptome profiling of hormone receptor-positive tumors

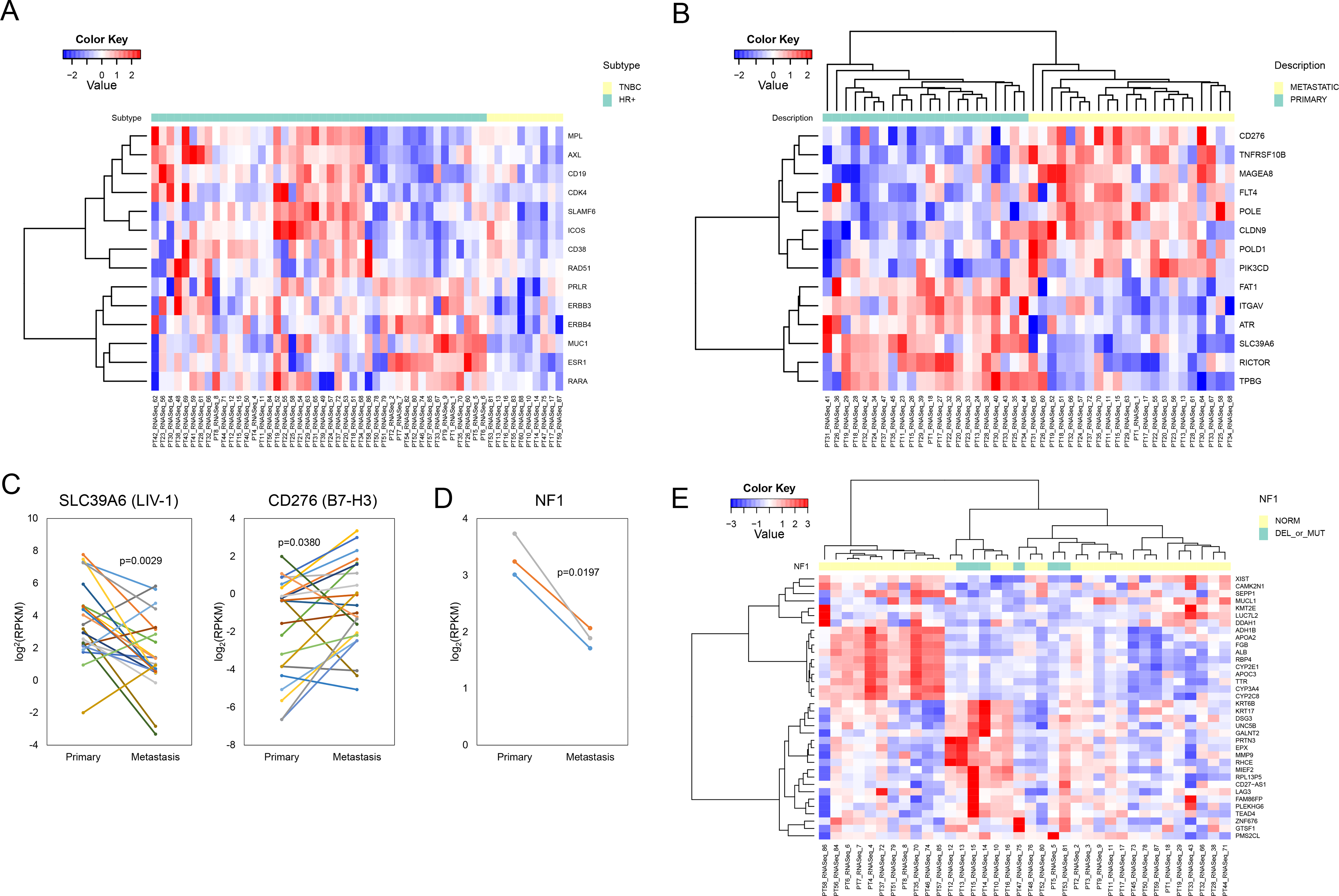

Sixty patients had 88 RNA-seq data and these were on 26 primary, 5 LLR and 57 metastatic samples. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of these 88 samples did not define tumor groups or their subtypes. We narrowed down our analysis to identify the actionable transcriptome in metastatic disease. The three subtypes of breast tumors have different biologic behaviors and require different management approaches; thus, we further analyzed the actionable transcriptome between 44 HR+ and 10 TNBC metastatic samples. With FDR 0.05 and fold change ≥ 2 or ≤ −2, we identified 14 DEGs (Fig. 2A). In addition to ESR1 being overexpressed in HR+ tumors as expected, selected investigational therapeutic targets were overexpressed in HR+ tumors including MUC1, HER3, HER4 and Prolactin receptor (PRLR).

Figure 2. Differential gene expression in primary and metastatic breast tumors.

(A) The supervised heatmap shows the actionable transcriptome (FDR 0.05 and fold change ≥2 or ≤2) in the HR+ vs triple-negative metastatic tumors. Each column represents a single tumor sample and each row represents an individual gene. (B) The supervised heatmap shows the actionable transcriptome (FDR 0.05 and fold change ≥2 or ≤2) in the HR+ matched primary vs metastatic tumors. Each column represents a single tumor sample and each row represents an individual gene. The random effect from each patient was removed. (C) SLC39A6 (LIV-1) and CD276 (B7-H3) mRNA expression in the HR+ matched primary and metastatic tumors. Paired t-test was used to compare the groups. (D) NF1 gene expression in primary and DM (deleted) samples. Paired t-test was used to compare the groups. (E) The unsupervised heatmap shows the DEGs (FDR 0.05 and fold change ≥2 or ≤2) in the NF1 normal (NORM) vs NF1 altered (DEL_or_MUT) tumors. Each column represents a single tumor sample and each row represents an individual gene.

We focused our analysis on matched samples for HR+ patients. There were 22 matched primary and metastatic samples that had RNA-seq data; with FDR 0.05 and fold change ≥ 2 or ≤ −2, we identified 970 DEGs. Genes that were altered in at least two samples were shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. We used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (QIAGEN Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuitypathway-analysis) to identify canonical pathways and functions of DEGs in primary and metastatic tumors (44). Top canonical pathway was acetone degradation I (cytochrome P450 family) (p=2.63e-07 with 34.5% overlap). The cytochrome P450s (CYPs) metabolize chemotherapeutic agents, such as taxanes, docetaxel and paclitaxel. In breast tumors, CYPs expression had previously been reported to be have a significant association with lymph node positivity (45). Thirteen of 14 CYPs in our study had increased expression in DMs.

Next, we studied the molecular evolution of the actionable transcriptome in the 22 patients with matched primary and DM samples. With FDR 0.05 and fold change ≥ 2 or ≤ −2, we identified 14 DEGs (Fig. 2B). These included differential expression of emerging targets for ADCs and bispecific antibodies including an increase in expression of some of the targets in the metastasis such as B7-H3 (CD276), death receptor 5 (TNFRSF10B), and melanoma associated antigen 8 (MAGEA8), while a decrease of several others including LIV-1 (SLC39A6) (Fig. 2C).

We looked at the impact of genomic alterations on gene expression. Of 41 patients whose most recent samples were genomically profiled, seven had RPS6KB1 amplifications. We had RNA-Seq data available for six of the amplified and 30 RPS6KB1 normal samples, amplification did not significantly change RPS6KB1 gene expression (p = 0.8768). We looked at NF1 gene expression in three patients who had NF1 deletion in their metastatic tumors and detected a significant decrease (p = 0.0197) (Fig. 2D). Six patients had NF1 mutations or deletions and 30 were normal. With FDR 0.05 and fold change ≥ 2 or ≤ −2, we identified 36 DEGs (Fig. 2E) (Supplementary Table S7). IPA matched nine of these DEGs (ALB, APOA2, APOC3, CAM2N1, CYP2C8, CYP2E1, CYP3A4, DDAH1, and DSG3) as a part of lipid metabolism, small molecule biochemisty, vitamin and mineral metabolism (p=2.21e-12).

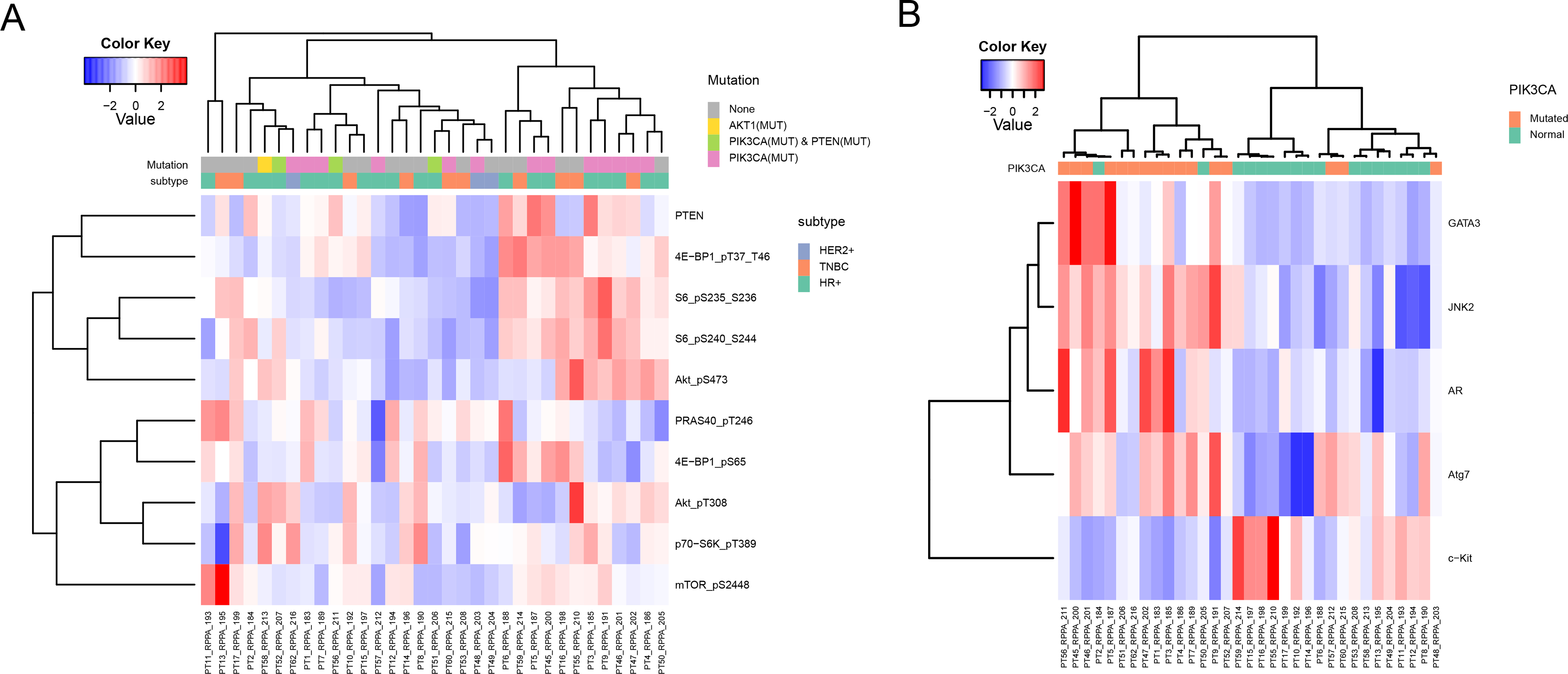

Effect of gene mutations on pathway activation

Thirty three patients had matching gene mutation (T200.1) data and functional proteomic analysis with RPPA. Sixteen samples had PIK3CA and one sample had AKT1 mutations. Three of the PIK3CA mutants also had PTEN mutations. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of protein expression based on mutations status showed that PIK3CA and AKT1 mutant samples did not cluster together (Supplementary Fig. S4). PTEN (not included in PI3K score), p-4E-BP1 T37/46, p-6 S235/236, p-S6 S240/244, and p-Akt S473 mostly had similar expression patterns as a group, high or low (Fig. 3A). Overall, when samples were clustered by PI3K pathway activation on RPPA, the patients were not separated by their PIK3CA/Akt/PTEN genotype. Eight samples had their PI3K scores by RPPA in the top quartile and were considered as having PI3K pathway activation. Two (25%) of these 8 PI3K activated samples had PI3KCA mutations, while 13 (52%) of 25 PI3K non-activated tumors had PIK3CA mutations; this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.2419).

Figure 3. Differential protein expression in metastatic breast tumors.

(A) The heatmap shows the expression of proteins that are involved in PI3K pathway activation. Each column represents a single tumor sample and each row represents a protein. The samples were aligned by mutational status (no mutation (None), AKT1 mutant (AKT1(MUT)), PIK3CA and PTEN mutant (PIK3CA(MUT) & PTEN(MUT)), and PIK3CA mutant (PIK3CA(MUT)) and tumor subtypes. (B) The heatmap shows the DEPs (FDR 0.2) in PIK3CA wild-type (Normal) and PIK3CA mutant (Mutated) samples. Each column represents a single protein sample and each row represents a protein. The samples were aligned by mutational status.

Next, we compared differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in altered and not altered gene groups. The comparison of PIK3CA mutant versus wild-type identified five DEPs. Four were upregulated in PIK3CA mutant tumors: GATA3, mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 (JNK2), androgen receptor (AR), ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme ATG7 (ATG7), and one was upregulated in wild-type PIK3CA tumors: mast/stem cell growth factor receptor (KIT) (FDR 0.2) (Fig. 3B). There were five ESR1 mutated and 28 wild-type samples and there were no DEPs. Genomic analysis revealed six NF1 altered (mutated or deleted) samples. The comparison of NF1 altered versus normal did not identify any DEPs (FDR 0.2). We repeated the analysis in NF1 altered and normal groups, and looked at expression of phospho-proteins related to MAPK (p-B-Raf S445, p-c-Jun S73, p-C-Raf S338, p-JNK T183 Y185, p-MAPK T202/Y204, p-MEK1 S217/S221, and p-p38 T180/Y182) (Fig. 3C) and PI3K pathways (p-4E-BP1 T37/46, p-4E-BP1 S65, p-S6 pS235/236, p-S6 S240/244, p-Akt T308, p-Akt S473, p-PRAS40 T246, p-p70-S6K T389, p-mTOR S2448, and p-Tuberin T1462) (Fig. 3D). These comparisons did not identify any DEPs at FDR 0.2.

There were 207 matching total protein and gene expression data. Only eight (ESR1, KIT, JAG1, CLDN7, SERPINE1, EIF4EBP1, GATA3, and MSM6) had a moderate-strong correlation (r = 0.50–0.76) (Supplementary Table S8).

Discussion

In spite of advances in oncology MBC remains an incurable disease. Thus there is urgency in better understanding the molecular features of MBC and identify actionable molecular alterations and their evolution with progression. There have been several studies on the molecular profile of breast cancer, with demonstration of several actionable genomic alterations, and recognition of several additional therapeutic opportunities. However, many initial studies were performed in primary breast cancers, few studies systematically studied DNA, RNA and protein, and even fewer incorporated primary and matched DM. In this study, we evaluated DNA, RNA and protein expression in patients with MBC. We confirmed alterations in several well established breast cancer genes, and some other less frequent but potentially actionable genes. Further, our series of matched primary and DM samples allowed us to assess molecular evolution in genomics and the transcriptional profile.

Comparative genomics-based analysis of matched primary and metastatic tumors is a way to understand the evolution of cancer. In this series we had 10 matched primary and DM tumors. The concordance of alterations in primary and matched DM samples was only 10%. TP53 and PIK3CA mutations were the most common hotspot mutations between the matched primary and metastatic tumors with a concordance rate of 100% and 75%, respectively. Three patients gained ESR1 mutations in the DM; emergence of new ESR1 mutations in metastatic tumors of patients treated with endocrine therapies has been previously documented (19,21,46). The level of CNA has been shown to be a prognostic factor in several cancers, including breast cancer (47). We hypothesized that metastatic tumors may have further genomic changes including loss of or gain of key driver mutations. Among the actionable genes list, the concordance of alterations in primary and matched DM samples was only 10%, when we analyzed mutations only and excluded CNAs, the concordance increased to 27%. In the PI3K pathway, PIK3CA (three out of four patients), PTEN (one out of two) and AKT1 (one out of one) mutations were concordant. Overall, ten genes had lost and ten genes had gained actionable mutations in the DM. Notably one patient in the matched series had a complete mismatch of genomic alterations, with a match of polymorphisms (not shown) confirming the same donor. We had reported such a case in a prior breast cancer study as well (23). Such cases emphasize that patients with DM could have another primary (same tumor type or other), emphasizing importance of pathologic confirmation of metastatic disease. Taken together, this data provides support for obtaining repeat biopsies in the metastatic setting, both to assess ER, PR, and HER2 status and to provide a new sample for molecular profiling.

A gene of interest that demonstrated genomic evolution was NF1. We detected NF1 mutations as well as NF1 deletions in both HR+ breast cancer and in TNBC, as shown in Fig. 1A. In a previous study of genomic sequencing in patients with MBC, we had found that NF1 is a significantly altered gene (17). We had identified NF1 loss in patients with both HR+ MBC and TNBC, and found that NF1 deletions noted on NGS on the T200 platform are indeed lost on SNP arrays. We had also reported NF1 as a gene of interest in a multicenter study of breast cancer patients who had modified radical mastectomy for clinical node positive disease with 1–3 positive nodes (23). DNA analysis on primary tumors of patients who developed a LRR, or DM vs patients who did not recur identified significantly more NF1 mutations in patients with LRR or DM respectively. Three patients had matched primary vs. LRR samples, in that series and one patient had a gain of a NF1 mutation in the LRR. Angus et al analyzed the whole genomic profile of 442 MBC patients and found 35 SNV/ InDels in NF1, and one NF1 deletion (48). They compared their results to those from studies conducted in primary breast cancer (49,50), and found six genes, including NF1 was more frequently mutated in HR+ MBC than primary breast cancer. In our current series, out of the 10 patients with matched samples shown in Fig. 1B, four had copy number loss in NF1, three with detection of deletions in the DM, and a fourth with loss of NF1 amplification. Looking at the transcriptome of the three patients with acquired NF1 deletion, we indeed observed a decrease in their NF1 mRNA expression in the DM compared to the primary as well. NF1 encodes neurofibromin that inhibits Ras-Raf-Mek-Erk (Ras/MAPK) signaling (51). Recently, MEK inhibitor selumetinib was approved by the FDA for pediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, establishing a role for MEK inhibition for patients with NF1 inactivation. It was reported that somatic NF1 loss confers endocrine resistance in ER+ breast cancer preclinically and that there is enhanced efficacy with the combination of MEK inhibitors and selective ER degraders (51). Thus, this compelling data is being brought forward into combination therapy trials in ER+ NF1 mutant cancers. Further, there is growing interest in targeting MAPK pathway in many tumor types including breat cancer. As Ras/MAPK pathway was implicated in promoting immunesuppression (52) many combinations with MEK inhibtors and immunotherapy has been explored. In addition there are emerging data for several other exciting MEK combinations, including combinations with inhibitors of CDK4/6, SHP2, and BET (53–55). Many of these combinations may how promise for MAPK driven tumors. Taken together, these data suggest NF1 mutation/loss may be an acquired alteration conferring more aggressive biology and therapeutic resistance and may open up new therapeutic options.

ADCs bind to their targets and deliver cytotoxic drugs (or payloads) into the cells after internalization. An ideal ADC target would have high expression in tumor and no or very low expression in all normal tissues. A well-established ADC target is HER2, with initial FDA approval of T-DM1 and more recently approval of trastuzumab deruxtecan for HER2+ breast cancer. Recently TROP2 ADC sacituzumab govitecan was FDA approved for TNBC, with significant effort in drug development with other ADCs targeting TROP2 as well as multiple other targets such as LIV-1 (SLC39A6) and B7-H3 (CD276) for breast cancer and other solid tumors. When we compared the primary tumors and matched DMs, 4 of 16 DEGs in our actionable transcriptome were targets of ADCs or bispecifics in development. We observed higher expression of B7-H3, TNFRSF10B, and MAGEA8 and lower expression of LIV-1 in metastatic tumors. This suggest that mRNA expression profile changes as the DM tumors evolve over time and this may effect expression of actionable targets. This data provides support for building pre-treatment biopsies into ongoing ADC trials to determine target expression at treatment initiation to facilitate expression/response comparisons as well as to allow for comparisons to archival expression to better understand tumor evolution.

PIK3CA and PTEN alterations, mRNA expression and high PI3K scores are all indicating activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. We identified 5 DEGs between PIK3CA mutant and wild-type groups. Notably there was not a clear segregation of patients based on their gene expression profile by genotype. There was not a significant difference in PI3K activation by RPPA in PIK3CA mutant tumors. This analysis was limited by numbers and pathway activation could have occurred due to other mechanisms such as PTEN protein expression loss that we did not systematically assess. Further studies are needed to identify optimal approaches to assess pathway activation for targeted therapy.

We looked at the role of genomic alterations in gene expression (DNA vs RNA) and pathway activation (DNA vs protein), and compared gene and protein expression (RNA vs protein). Neither genomic alterations predicted gene or protein expression nor there was strong correlation between proteomic and transcriptomic data. We cannot exclude the possibility that the lack of concordance between DNA alterations and RNA and protein and protein phosphorylation are not merely the result of tumor heterogeneity and the tumor cellularity of the samples. Previous studies have investigated the impact of laser capture dissection as an approach for tumor cell enrichment, and found that LCM has no detrimental effect on RPPA data, but rather increase accuracy and quality of RPPA data (56,57). In another study, tumor cell enrichment using laser capture microdissection resulted in the identification of molecular associations, such as PTEN protein expression was reduced only in dissected samples with PTEN alterations, which was missed when whole tissue lysates were used (58). It was shown that mRNA levels were not always correlated with protein levels and their activation (phosphorylation) (59). This warrants further validation of biomarkers especially when proteomic and genomic data are not concordant.

To date there have been several genomic profiling studies focused on breast cancer. Many of these have studied the molecular characteristics of primary breast cancer (50), while some recent manuscripts have profiled MBC (60,61). Due to the limited amount of tumor available from metastatic sites, even when a biopsy performed, there is need to preserve the tissue for patient care. Thus it has been more challenging to do larger cohort studies with MBC (17). The studies that have been done, have been done with different genomic testing platforms, often with variant calls from different callers. Few studies have compared matched primary and metastatic breast cancers (62–64), while some others compared findings in MBC to historical primary breast cancer series (48,61). Most of these efforts in MBC were unable to address transcriptomics and proteomics and none addressed evolution of the actionable transcriptome to our knowledge. Our study is thus unique, as we attempted to integrate data emerging from DNA and RNA and functional proteomics. Further we were able to provide data on transcriptomic profile in MBC and the evolution of the actionable transcriptome in 33 matched samples.

Our study had several limitations. We initiated the study at a time when genomic testing was less frequently offered in clinical practice and the sequencing was performed retrospectively in a research environment. Doing studies on genomic evolution is challenging as biopsies of metastases are small in size, and are often depleted during biomarker analysis for clinical care or clinical trials. Although we started with a cohort of over 200 patients in whom matched primary and DM samples were available, our sample size ultimately became substantially smaller due to difficulty in identifying both primary and metastatic samples. We had further attrition due to poor tumor cellularity, or poor yield or poor quality of DNA and/or RNA samples. Ultimately, some of the metastatic samples originated from extra biopsies obtained on patients undergoing pre-treatment biopsies on ongoing clinical trials, thus, there might be a sample selection bias. This gave us good quality metastatic samples for RNA analysis, but also means that often the primary tumors were tested on archival tissue and metastatic tumors were tested on snap-frozen samples. Although FFPE and frozen tumors are thought to yield similar sequencing results (65,66), and FFPE is now routinely utilized in clinical sequencing genomic testing, we cannot exclude the possibility that use of different types of biospecimens led to some of the differences in our results. Further, matching blood was available only on patients who had prospective sample collection. Thus for some patients targeted exome sequencing was done without normal comparators. The heterogeneity of treatments did not allow us to formally study the selective pressure related to prior exposure to different therapeutics and their impact on molecular evolution. We expect that many of these challenges could be overcome in future studies as integrated DNA and RNA analysis starts being deployed clinically in routine care.

Conclusion

Our data provided insights into evolution of metastatic breast cancer by describing the genotype and phenotype changes in primary and metastatic tumors. Both gains and losses of actionable genes were observed in DM and concordance of alterations was low, which justifies repeat biopsy and genomic profiling of metastatic tumors. NF1 acquired alterations were particularly interesting, and suggest that they might be conferring therapeutic resistance, and may represent a therapeutic target in MBC. Notably, most of the patients had multiple alterations, which highlights one challenge in precision medicine, and need for strategies to prioritize treatment options. Evolution of both genomic targets and novel targets such as ADC targets highlight the importance of repeat testing for novel treatment strategies as well as the need to systematically test impact of molecular evolution on treatment efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Metastatic breast cancer is not curable. There is a great need to understand the biology of metastatic disease, identify novel therapeutic targets and develop strategies for treatment selection. In this study, we report molecular profiling of metastatic breast cancer focusing on molecular evolution in actionable alterations. An analysis of DNA, RNA, and functional proteomics was done. Several common alterations and alterations in emerging biomarkers were identified. In patients with matched primary and metastatic tumors that underwent targeted exome sequencing, discordances in actionable alterations were common. RNA profiling identified significant differences in expression levels of actionable genes including antibody drug conjugate targets. Thus both genomic and transcriptional profiling demonstrated intertumoral heterogeneity and potential evolution of actionable targets with tumor progression. These findings have important implications for biomarker-driven personalized therapy. Further work is needed to optimize testing and integrated analysis for treatment selection.

Acknowledgements

The Precision Oncology Decision Support (PODS) database receives licensing fees from Philips Healthcare to support ongoing development of the solution.

This study was partially funded by a grant from Astra Zeneca, and the Nellie B. Connally Breast Cancer EndowmentOCRA Collaborative Research Development Award, ICI Fund Award, CPRIT RP170640, NIH/NCI U24CA210950, NIH/NCAT UL1TR003167 (F.M-B and A.K., NIH/NCI P30CA016672/Cancer Center Support (Core) Grant (A. K. and F-M-B). The results shown here are in part based upon data generated by the TCGA Research Network: https://www.cancer.gov/tcga.

We would like to thank Ms. Susanna E. Brisendine for helping prepare and submit the manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflict of Interests:

A. Akcakanat, X. Zheng, C. X. Cruz Pico, T. Kim, K. Chen, A. Korkut, A. Sahin, V. Holla, E. Tarco, G. Singh, and A. M. Gonzalez-Angulo declare no potential conflict of interest.

S. Damodaran reports receiving research support from Guardant Health, EMD Serono, Taiho, and Novartis. Served as consultant for Pfizer and on the advisory committee for Taiho.

G. B. Mills is a SAB/Consultant: for AstraZeneca, Chrysallis Biotechnology, GSK, ImmunoMET, Ionis, Lilly, PDX Pharmaceuticals, Signalchem Lifesciences, Symphogen, Tarveda, Turbine, Zentalis Pharmaceuticals; has Stock/ Options/Financial relationships with Catena Pharmaceuticals, ImmunoMet, SignalChem, Tarveda; has Licensed Technology: HRD assay to Myriad Genetics, DSP patents with Nanostring and has Sponsored research from Nanostring Center of Excellence, Ionis (Provision of tool compounds).

F. Meric-Bernstam reports receiving commercial research grants from Aileron Therapeutics, Inc.,AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceutical, Calithera Biosciences Inc., Curis Inc., CytomX Therapeutics Inc., Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd., Debiopharm International, eFFECTOR Therapeutics, Genentech Inc., Guardant Health Inc., Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., Novartis, Puma Biotechnology Inc., and Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. She also served as a consultant for Aduro BioTech Inc., DebioPharm, eFFECTOR Therapeutics, F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., Genentech Inc., IBM Watson, Jackson Laboratory, Kolon Life Science, OrigiMed, PACT Pharma, Parexel International, Pfizer Inc., Samsung Bioepis, Seattle Genetics Inc., Tyra Biosciences, Xencor, and Zymeworks. Additionally, she serves on the advisory committee for Immunomedics, Inflection Biosciences, Mersana Therapeutics, Puma Biotechnology Inc., Seattle Genetics, Silverback Therapeutics, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals and Zentalis.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park S, Han W, Kim J, Kim MK, Lee E, Yoo TK, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Distant Metastasis and Survival Outcomes in Breast Cancer Patients with Locoregional Recurrence. J Breast Cancer 2015;18(2):160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong Y, Kim SS, Gong G, Lee HJ, Ahn SH, Son BH, et al. Prognostic Factors for Distant Metastasis in Patients with Locoregional Recurrence after Mastectomy. J Breast Cancer 2015;18(3):279–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. 2020. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. <https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf>. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- 5.Rimawi MF, De Angelis C, Contreras A, Pareja F, Geyer FC, Burke KA, et al. Low PTEN levels and PIK3CA mutations predict resistance to neoadjuvant lapatinib and trastuzumab without chemotherapy in patients with HER2 over-expressing breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;167(3):731–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman DM, Smyth LM, Donoghue MTA, Westin SN, Bedard PL, Dean EJ, et al. AKT Inhibition in Solid Tumors With AKT1 Mutations. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(20):2251–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smyth LM, Tamura K, Oliveira M, Ciruelos EM, Mayer IA, Sablin MP, et al. Capivasertib, an AKT Kinase Inhibitor, as Monotherapy or in Combination with Fulvestrant in Patients with AKT1 (E17K)-Mutant, ER-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26(15):3947–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smyth LM, Zhou Q, Nguyen B, Yu C, Lepisto EM, Arnedos M, et al. Characteristics and Outcome of AKT1 (E17K)-Mutant Breast Cancer Defined through AACR Project GENIE, a Clinicogenomic Registry. Cancer Discov 2020;10(4):526–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smyth LM, Batist G, Meric-Bernstam F, Kabos P, Spanggaard I, Lluch A, et al. Abstract P1–19-05: Capivasertib (AZD5363) in combination with fulvestrant in PTEN-mutant ER+ metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Research 2020;80(4 Supplement):P1–19–05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmid P, Abraham J, Chan S, Wheatley D, Brunt AM, Nemsadze G, et al. Capivasertib Plus Paclitaxel Versus Placebo Plus Paclitaxel As First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: The PAKT Trial. J Clin Oncol 2020;38(5):423–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SB, Dent R, Im SA, Espie M, Blau S, Tan AR, et al. Ipatasertib plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (LOTUS): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18(10):1360–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for locally recurrent unresectable or metastatic triple negative breast cancer. <https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-pembrolizumab-locally-recurrent-unresectable-or-metastatic-triple>. Accessed December 7, 2020.

- 13.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves atezolizumab for PD-L1 positive unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. <https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-atezolizumab-pd-l1-positive-unresectable-locally-advanced-or-metastatic-triple-negative>. Accessed December 7, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Robson ME, Tung N, Conte P, Im SA, Senkus E, Xu B, et al. OlympiAD final overall survival and tolerability results: Olaparib versus chemotherapy treatment of physician’s choice in patients with a germline BRCA mutation and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2019;30(4):558–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, Hurvitz SA, Goncalves A, Lee KH, et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med 2018;379(8):753–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tung NM, Robson ME, Ventz S, Santa-Maria CA, Marcom PK, Nanda R, et al. TBCRC 048: A phase II study of olaparib monotherapy in metastatic breast cancer patients with germline or somatic mutations in DNA damage response (DDR) pathway genes (Olaparib Expanded). J Clin Oncol 2020;38(15_suppl). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meric-Bernstam F, Zheng X, Shariati M, Damodaran S, Wathoo C, Brusco L, et al. Survival Outcomes by TP53 Mutation Status in Metastatic Breast Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 2018;2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yates LR, Knappskog S, Wedge D, Farmery JHR, Gonzalez S, Martincorena I, et al. Genomic Evolution of Breast Cancer Metastasis and Relapse. Cancer Cell 2017;32(2):169–84 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, Su F, Lonigro RJ, Cao X, et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet 2013;45(12):1446–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujii T, Matsuda N, Kono M, Harano K, Chen H, Luthra R, et al. Prior systemic treatment increased the incidence of somatic mutations in metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2018;89:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeselsohn R, Yelensky R, Buchwalter G, Frampton G, Meric-Bernstam F, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Emergence of constitutively active estrogen receptor-alpha mutations in pretreated advanced estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20(7):1757–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andreano KJ, Baker JG, Park S, Safi R, Artham S, Oesterreich S, et al. The Dysregulated Pharmacology of Clinically Relevant ESR1 Mutants is Normalized by Ligand-activated WT Receptor. Mol Cancer Ther 2020;19(7):1395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keene KS, King T, Hwang ES, Peng B, McGuire KP, Tapia C, et al. Molecular determinants of post-mastectomy breast cancer recurrence. NPJ Breast Cancer 2018;4:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen K, Meric-Bernstam F, Zhao H, Zhang Q, Ezzeddine N, Tang LY, et al. Clinical actionability enhanced through deep targeted sequencing of solid tumors. Clin Chem 2015;61(3):544–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meric-Bernstam F, Johnson A, Holla V, Bailey AM, Brusco L, Chen K, et al. A decision support framework for genomically informed investigational cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurnit KC, Dumbrava EEI, Litzenburger B, Khotskaya YB, Johnson AM, Yap TA, et al. Precision Oncology Decision Support: Current Approaches and Strategies for the Future. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24(12):2719–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson A, Khotskaya YB, Brusco L, Zeng J, Holla V, Bailey AM, et al. Clinical Use of Precision Oncology Decision Support. JCO Precis Oncol 2017;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hennessy BT, Meric-Bernstam F, Sahin A, Liu W, Ju Z, et al. Functional proteomics can define prognosis and predict pathologic complete response in patients with breast cancer. Clin Proteomics 2011;8(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meric-Bernstam F, Akcakanat A, Chen H, Sahin A, Tarco E, Carkaci S, et al. Influence of biospecimen variables on proteomic biomarkers in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20(14):3870–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009;25(14):1754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 2011;43(5):491–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lonigro RJ, Grasso CS, Robinson DR, Jing X, Wu YM, Cao X, et al. Detection of somatic copy number alterations in cancer using targeted exome capture sequencing. Neoplasia 2011;13(11):1019–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bamford S, Dawson E, Forbes S, Clements J, Pettett R, Dogan A, et al. The COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database and website. Br J Cancer 2004;91(2):355–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics 2010;26(16):2069–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38(16):e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao Y, Chen H, Liang H, Meric-Bernstam F, Mills GB, Chen K. CanDrA: cancer-specific driver missense mutation annotation with optimized features. PLoS One 2013;8(10):e77945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou W, Zhao H, Chong Z, Mark RJ, Eterovic AK, Meric-Bernstam F, et al. ClinSeK: a targeted variant characterization framework for clinical sequencing. Genome Med 2015;7(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parssinen J, Kuukasjarvi T, Karhu R, Kallioniemi A. High-level amplification at 17q23 leads to coordinated overexpression of multiple adjacent genes in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2007;96(8):1258–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dustin D, Gu G, Fuqua SAW. ESR1 mutations in breast cancer. Cancer 2019;125(21):3714–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stephens PJ, Tarpey PS, Davies H, Van Loo P, Greenman C, Wedge DC, et al. The landscape of cancer genes and mutational processes in breast cancer. Nature 2012;486(7403):400–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegel MB, He X, Hoadley KA, Hoyle A, Pearce JB, Garrett AL, et al. Integrated RNA and DNA sequencing reveals early drivers of metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Invest 2018;128(4):1371–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pereira B, Chin SF, Rueda OM, Vollan HK, Provenzano E, Bardwell HA, et al. The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refines their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nat Commun 2016;7:11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kramer A, Green J, Pollard J Jr., Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 2014;30(4):523–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haas S, Pierl C, Harth V, Pesch B, Rabstein S, Bruning T, et al. Expression of xenobiotic and steroid hormone metabolizing enzymes in human breast carcinomas. Int J Cancer 2006;119(8):1785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Razavi P, Chang MT, Xu G, Bandlamudi C, Ross DS, Vasan N, et al. The Genomic Landscape of Endocrine-Resistant Advanced Breast Cancers. Cancer Cell 2018;34(3):427–38 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hieronymus H, Murali R, Tin A, Yadav K, Abida W, Moller H, et al. Tumor copy number alteration burden is a pan-cancer prognostic factor associated with recurrence and death. Elife 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Angus L, Smid M, Wilting SM, van Riet J, Van Hoeck A, Nguyen L, et al. The genomic landscape of metastatic breast cancer highlights changes in mutation and signature frequencies. Nat Genet 2019;51(10):1450–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nik-Zainal S, Davies H, Staaf J, Ramakrishna M, Glodzik D, Zou X, et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature 2016;534(7605):47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012;490(7418):61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng ZY, Anurag M, Lei JT, Cao J, Singh P, Peng J, et al. Neurofibromin Is an Estrogen Receptor-alpha Transcriptional Co-repressor in Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020;37(3):387–402 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ebert PJR, Cheung J, Yang Y, McNamara E, Hong R, Moskalenko M, et al. MAP Kinase Inhibition Promotes T Cell and Anti-tumor Activity in Combination with PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade. Immunity 2016;44(3):609–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee MS, Helms TL, Feng N, Gay J, Chang QE, Tian F, et al. Efficacy of the combination of MEK and CDK4/6 inhibitors in vitro and in vivo in KRAS mutant colorectal cancer models. Oncotarget 2016;7(26):39595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zawistowski JS, Bevill SM, Goulet DR, Stuhlmiller TJ, Beltran AS, Olivares-Quintero JF, et al. Enhancer Remodeling during Adaptive Bypass to MEK Inhibition Is Attenuated by Pharmacologic Targeting of the P-TEFb Complex. Cancer Discov 2017;7(3):302–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nichols RJ, Haderk F, Stahlhut C, Schulze CJ, Hemmati G, Wildes D, et al. RAS nucleotide cycling underlies the SHP2 phosphatase dependence of mutant BRAF-, NF1- and RAS-driven cancers. Nat Cell Biol 2018;20(9):1064–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baldelli E, Haura EB, Crino L, Cress DW, Ludovini V, Schabath MB, et al. Impact of upfront cellular enrichment by laser capture microdissection on protein and phosphoprotein drug target signaling activation measurements in human lung cancer: Implications for personalized medicine. Proteomics Clin Appl 2015;9(9–10):928–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hunt AL, Pierobon M, Baldelli E, Oliver J, Mitchell D, Gist G, et al. The impact of ultraviolet- and infrared-based laser microdissection technology on phosphoprotein detection in the laser microdissection-reverse phase protein array workflow. Clin Proteomics 2020;17:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mueller C, deCarvalho AC, Mikkelsen T, Lehman NL, Calvert V, Espina V, et al. Glioblastoma cell enrichment is critical for analysis of phosphorylated drug targets and proteomic-genomic correlations. Cancer Res 2014;74(3):818–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wahjudi LW, Bernhardt S, Abnaof K, Horak P, Kreutzfeldt S, Heining C, et al. Integrating proteomics into precision oncology. Int J Cancer 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mao P, Cohen O, Kowalski KJ, Kusiel JG, Buendia-Buendia JE, Cuoco MS, et al. Acquired FGFR and FGF Alterations Confer Resistance to Estrogen Receptor (ER) Targeted Therapy in ER(+) Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26(22):5974–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bertucci F, Ng CKY, Patsouris A, Droin N, Piscuoglio S, Carbuccia N, et al. Genomic characterization of metastatic breast cancers. Nature 2019;569(7757):560–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meric-Bernstam F, Frampton GM, Ferrer-Lozano J, Yelensky R, Perez-Fidalgo JA, Wang Y, et al. Concordance of genomic alterations between primary and recurrent breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2014;13(5):1382–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akahane T, Kanomata N, Harada O, Yamashita T, Kurebayashi J, Tanimoto A, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing assays using triplet samples of normal breast tissue, primary breast cancer, and recurrent/metastatic lesions. BMC Cancer 2020;20(1):944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paul MR, Pan TC, Pant DK, Shih NN, Chen Y, Harvey KL, et al. Genomic landscape of metastatic breast cancer identifies preferentially dysregulated pathways and targets. J Clin Invest 2020;130(8):4252–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hedegaard J, Thorsen K, Lund MK, Hein AM, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Vang S, et al. Next-generation sequencing of RNA and DNA isolated from paired fresh-frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples of human cancer and normal tissue. PLoS One 2014;9(5):e98187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oh E, Choi YL, Kwon MJ, Kim RN, Kim YJ, Song JY, et al. Comparison of Accuracy of Whole-Exome Sequencing with Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded and Fresh Frozen Tissue Samples. PLoS One 2015;10(12):e0144162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.