Abstract

Urban runoff is known as an important contributor to diffuse a wide range of pollutants to receiving environments. Hydrocarbons are common contaminants in runoff mainly transported coupled to suspended particles and sediments. The aim of the study was to investigate the distribution and sources of Aliphatics in the sediments of Tehran’s runoff drainage network. Thirty surface sediment samples were collected along with three main sub-catchments of Tehran during April 2017. The concentrations of n-Alkanes (nC-11-nC-35) and isoprenoids were determined by GC-MS, and their possible emission sources were evaluated using the biomarkers and the diagnostic ratios. Total aliphatic hydrocarbon (n-alkanes + isoprenoids) concentrations were found in the range of 2.94 to114.7 mg.kg−1 dw with the total mean of 25.4 mg.kg-1 dw in the whole catchment. The significant concentrations of n-alkanes between n-C20 and n-C24 indicate the predominance of petrogenic origins at all stations. The CPI values range from 0.7 to 3, except the station C1S28 (CPI = 4.2). The CPI values were less than 1.6 at 70% of the stations which indicate the petrogenic nature of the aliphatic origins. Pr/Ph and LMW/HMW ratios ranged from 0.3 to 2.5 and 0.3 to 5.6 confirmed the petrogenic sources as the major origin of Aliphatics in urban runoff sediments. The ratios of n-C17/Pr and n-C18/Ph vary from 0.4 to 2.1 and 0.2 to 2.1, respectively which showed that petroleum contamination is mainly due to the degraded oil products with a lesser extent of fresh oil. Results revealed that the aliphatic hydrocarbons in the sediment samples were derived mainly from petrogenic sources such as leakage and spillage of fuels and petroleum derivatives with a relatively low contribution of biogenic sources. Vascular plants’ waxes and microbial activities are identified as the most important biogenic sources of the samples. The mean concentrations of total organic carbon were 13.3,12 and14.7 mg.g−1 dw in the sub-catchments 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Pearson correlation test demonstrated a weak correlation between the concentrations of n-alkanes and TOC (P > 0.05) with a correlation coefficient of less than 0.54 for all the sub-catchments.

Keywords: Aliphatic hydrocarbons, Sediment, Total organic carbon, Runoff, Source identification

Introduction

Urban development and rising human activities have made urban runoff as a major challenge for the management of these areas [1]. The presence of chemical contaminants in the urban storm-water from various sources is a major threat to the receiving environments, particularly aquatic ecosystems [2, 3]. During a rainfall event, a large number of contaminants are washed from the atmosphere and impermeable surfaces, and carried by storm-water runoff, in forms of soluble, suspended, and colloidal. Point and non-point sources such as vehicle emissions and industrial activities lead to a complex runoff mixture containing organic and inorganic compounds, nutrients, hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and so on [4, 5].

petroleum hydrocarbons as a broad group of organic compounds are frequently found in various media in the cities including airborne particulates [6, 7], soil [8], runoff water [9] and etc. urban runoff which have harmful effects on human and environmental health [10]. Two main groups of petroleum hydrocarbons including aliphatic hydrocarbons (AHs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are among the most important organic pollutants which are found in considerable concentration in these streams [11–13]. The AHs are composed of straight and saturated carbon chains from C6 to C40, which consist of about 80% of crude oil [14, 15]. Numerous studies have reported various sources of AHs from a variety of petrogenic and biogenic sources. The main natural sources of AHs are terrestrial vascular plants, plankton, bacteria, algae, degradation of plants and, animal biomass, while crude oil and its products are the major anthropogenic sources [16–19].

Due to the low solubility and hydrophobicity properties, these compounds generally have a high tendency to adhere to and accumulate to suspended solids and sediments [20]. Hence street dust and sediments in urban areas act as an medium for transport of these pollutants to the runoff and its accumulation in sediments [21]. Their accumulation due to biological and geochemical mechanisms can be toxic to the sediment-dwelling organisms or impaired reproduction and lowered species diversity in environments affected by urban runoff. Therefore, sediment has a key role in exploring the fate of hydrocarbons in aquatic environments [14, 22]. The physicochemical characteristics of hydrocarbons especially n-alkane compounds in water and sediment samples depend on the source of these pollutants in the environmental matrices [23]. The compounds are commonly found in the environment as complex mixtures deriving from multiple sources.

Therefore, Understanding the distinction between biogenic and anthropogenic origins, as well as the further identification of inputs from petrogenic, pyrogenic sources require the use of geochemical or molecular markers. Geochemical or molecular markers as the compounds that retain the signature of their sources and structural correction which occurred during transport in the environment [24]. Some typical indices, molecular marker, and diagnostic ratios utilizing the distribution of sedimentary AHs that have been employed to differentiate the multiple origins in the aquatic environments are CPI, NAR, TAR, ACL, PLK, UCM/R, n-C29/n-C17, LMW/HMW, Pristane/C17, Phytane/C18, Pristane/Phytane, Rn-alkanes/n-C16 [25–28]. Hence, urban runoff is considered as one of the major emission sources of the Aliphatic compounds into the environment, however, there are few studies on the distribution and/or source identification of the compounds in urban streams[29, 30] and urban runoff [9].

In Tehran, urban runoff is usually transported to south areas of the city through a separate sewer system, and significant volume of it is used for irrigation of croplands and green spaces, and the rest is discharged to sensitive ecosystems. The previous studies demonstrated the presence of those compounds in the groundwater and the raw wastewater of the city [31, 32]. In addition, the mean concentration of hydrocarbons in the top soil of agricultural fields was reported 0.22 to 68.11 mg.kg−1dw in south of the city [33]. Despite the importance of runoff pollution, there is no published data on aliphatic hydrocarbon concentrations and source identification in Tehran’s runoff sediments, which is the subject of this current study.

In this study, we identify the concentration and source of AHs and total organic carbon1 as a key factor in the distribution of these compounds in the sediments of the surface runoff channels and streams in three sub-catchments of Tehran city.

Materials and methods

Study area

Tehran, the capital of Iran with a population of about 11 million [34] and 730 km2 area, is located in the south of Alborz Mountains and has a semi-arid climate with precipitation around 230 mm/yr. In the year 2015, its runoff was estimated at approximately 500 mm3.yr−1, while over 250 mm3 had been passed out of the city [35]. It has a complex drainage network including eight natural streams and more than 550 km of main concrete channels. In fact, this city is divided into three sub-catchments with separate discharge including west and northwest (Kan), central (Firozabad) and east and southeast (Sorkheh Hesar). Most of the collected runoff is used for irrigation in the southern fields of the city and the rest discharge to Band-e-Alikhan wetland and the Salt Lake, where both of them are environmentally protected areas.

Sampling and sediment preparation

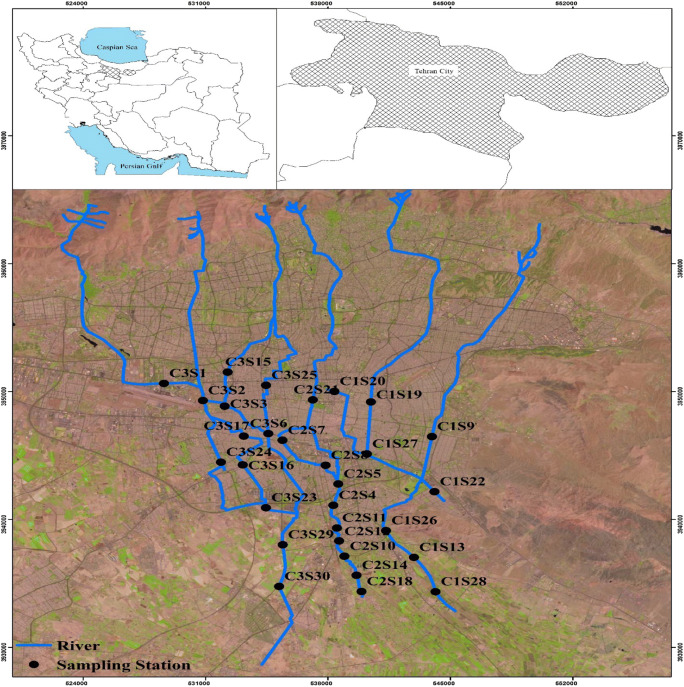

During April 2017, surface sediment samples (0–10 cm) were collected after a rainfall event in 30 stations with three replications, within 24 h following 30 days dry period. Tehran’s’ runoff main drainage network and sampling stations being demonstrated and presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study area within Iran, Tehran province and Tehran city accompanied by location of sampling stations

The samples were taken using stainless steel shovel, immediately placed in aluminum bags, kept at 4 °C, transferred to the laboratory, and stored in the freezer under −20 °C until analysis. Before sampling, all equipment was completely washed and rinsed with deionized water and Acetone, respectively.

All solvents were distilled before use, glassware was rinsed with deionized water, methanol, hexane and acetone and finally placed in the oven at 150 °C for 4 h to eliminate any feasibility organic contamination. Silica, alumina, and sodium sulfate were purified by heating at 400 °C for 4 h. The samples were purified and extracted according to MOOPAM(1999)[36]which includes silica gel chromatography cleanup, Soxhlet extraction2 and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis (GC-MS) [36]. The samples were air-dried at room temperature, homogenized with an agate pestle and mortar, then sieved through 63 μm mesh to remove large materials and homogenize, 10 g sieved sample was weighed and mixed with 5 g anhydrous sodium sulfate and activated copper in order to eliminate moisture and sulfur respectively. Hydrocarbons were extracted from the sample (about 10 g accurately weighted) in a pre-cleaned cellulose extraction thimble by Soxhlet apparatus for 8 h with a 100 mL mixture of HPLC grade N-hexane/ Dichloromethane (1:1, v:v). Deuterated surrogate standards (n-dodecane-d26) were added to the sample aliquot before extraction. Then the extracts concentrated to about 2 mL with rotary evaporator. A fully activated silica gel column chromatography (0.45 cm i.d. 18 cm) was used to fractionate n-alkanes using 20 mL of 1:1 v/v n-Hexane/ Dichloromethane. Then they were concentrated under a gentle stream of nitrogen blow down and reconstituted in a volume of 1 mL. All the authentic standards for n-alkanes were purchased from Merck (Germany). All solvents used for analyses were of chromatographic grade from Merck.

Instrumental analysis

All the cleaned samples were analyzed for 27 AHs, including n-alkanes (n- C11 to n-C35) and two isoprenoids (Pristane and Phytane) by a gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, model7890A) and Mass Spectrometer(Model 5975C) with split-less injection, HP5 Column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm film thickness) and helium carrier gas (99.99%) with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The temperature of the GC oven was set 60 °C, (held for 5 min), then 290 °C (rate of 6 °C.min−1) and held for 10 min came back to the basic status. Mass Spectrometer operation conditions were: the ion source was operated at 240 °C, electron multiplier 70 eV, interface temperature 240 °C. Peak identification was performed by comparison with retention times of authentic standards. The calibration curve was achieved by linear regression of the peak levels versus the known concentrations (r2 = 0.95). The total organic carbon content (TOC) of the samples was measured by the Loss on Ignition3 method [37]. The samples were dried at 60 °C for 24 h, acidified to pH = 2 to remove inorganic carbon content, then weighed by 0.0001 g digital Balance (Sartorius TE 124 s). Followed by placing the samples in an electric furnace at 450 °C for 6 h. TOC was determined in mg.kg−1dw from the weight difference of the dried sample before and after furnacing.

Quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC)

Blanks were used periodically with each batch of the samples (10 samples/batches) to determine contamination, and the values were always less than the detection limit or higher than the normal values. Approximately5–10 g of each freeze-dried sample was spiked with 10 μl of n-Alkane surrogate internal standard (54 μg g−1 of n-dodecane-d26) prior to extraction and analysis. The calibration curve was achieved by linear regression of the peak levels versus the known concentrations (r2 = 0.95).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (ver22). Shapiro-Wilk Test and one-way ANOVA test were applied to determine the normality of data and compare the concentration distribution of AHs and TOC, the differences of AHs’ concentration (the least significant difference4) in three sub-catchments, respectively. Pearson’s correlation coefficient test was used to quantify the statistical relationship between AHs concentration and TOC values. The main hydrocarbon (MH) and the five diagnostic ratios: C17/Pr,5C18/Ph,6Pr/Ph, LMW/HMW and carbon preference index (CPI) were applied to identify potential sources.

Result and discussion

Concentration and distribution of aliphatic compounds

Table 1 summarizes the mean and the range of concentrations of n-alkanes7 (n-C11–35) and isoprenoids (Pr and Ph). The total concentrations of n-alkanes range from 2.22 to 99.49 mg.kg−1 dw with an overall mean of 21.5 mg.kg−1 dw and illustrate large variation throughout stations. The mean concentration of the n-alkanes along with the Isoprenoids ranged from 2.94 (station C2S10) to 114.7 (station C3S25) mg.kg−1 dw with a total mean of 25.4 mg.kg−1 dw. These figures are higher than the total mean concentrations reported in the sediments of urban rivers in Brazil (0.01–165.6 μg.kg−1 dw) [29] and France (0.18–26.7 mg.kg−1 dw) [30], and were comparatively lower than those reported for sediments from the runoff of São Paulo city (116.2–2393.5 mg.kg−1) [9], sediments of river in Vietnam (1056 - 34794μgg−1) [38] and some coastal areas such as superficial sediments of the coral reefs of the Persian Gulf (385–937 μg.g−1) [28]. Some previous studies [39, 40] have recommended a classification to AHs contamination status in sediment media as following: less than 10 mg.kg−1dw as non-contaminated, 10–100 mg.kg−1 dw as low, 100–500 mg.kg−1dw as moderate, and more than 500 mg.kg−1dw as highly contaminated . The sediment samples are mostly classified as non-contaminated to low contaminated levels based on the classification. The distribution of AHs in the sub-catchments indicates heterogeneous spatial variation, which could be explained in terms of station characteristics [41]. There is no obvious pattern of odd to even numbers of carbon atoms of n-Alkane, but short chain n-alkanes (<23 carbons) are more abundant than long chain n-alkanes (>23 carbons), where the short-chains form >70%, >60% and > 50% of the total concentration of n-alkanes at stations of the sub-catchments 1, 2 and 3, respectively except C1S28, C2S14 and C3S29 where the significant concentration of n–C25, n-C27 and n-C29 are found. Figure 2 exhibits the Compositional profile of AHs in the samples of some stations. The highest total concentrations detected at the stations C3S25 (99.4 mg.kg−1 dw), C2S5 (76.9 mg.kg−1 dw) and C2S4 (74.4 mg.kg−1 dw) which are located in densely populated with heavy traffic areas while stations of C2S10, C1S13 and C2S18, with the lowest concentration, are located in the vicinity of crop fields with a low population density in the south of Tehran. Generally, main stations with high total concentrations were located in areas with high traffic density and human activities, whereas the stations with lower concentrations were located in agricultural zones and light traffic areas. The influence of vehicles traffic and population density was evident in runoff samples of Madrid city, where the automobile exhaust particulates and the lubricant oils have introduced as the primary contributors to the hydrocarbon build-ups in this city [42]. Distributions of n-alkanes and isoprenoids in the sub-catchments are illustrated in Fig. 3. Whereas the mean concentrations of the major n-alkanes (n-C12 to n-C26, n-C30), and the isoprenoids in sub-catchment 2 are significantly higher than that of the remaining due to the situation in the enteral area of the city with more dense population, heavy traffic and human activities rather than the two other sub-catchments. Totally, Ph ( = 2.29 mg.kg−1 dw) and n-C35 (= 0.02 mg.kg−1 dw) had the highest and the lowest concentration at all stations, respectively. One-way ANOVA analysis demonstrated no significant difference between the mean concentrations of the total AHs among the stations of the sub-catchments (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Concentrations (mg.kg−1 dw), and biomarker ratios in surface sediment of urban runoff from the Tehran’s sub-catchments

| Compound | Sub-catchment 1 | Sub-catchment 2 | Sub-catchment 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | |

| C11 | 0.01–1.59 | 0.68 | 0.01–0.93 | 0.67 | 0.05–2.17 | 0.25 |

| C12 | 0.03–0.53 | 0.3 | 0.02–3.2 | 0.52 | 0.09–2.55 | 0.54 |

| C13 | 0.26–2.02 | 0.78 | 0.14–5.3 | 0.74 | 0.13–2.96 | 1.28 |

| C14 | 0.19–1.77 | 0.8 | 0.12–5.28 | 0.85 | 0.2–3.8 | 1.15 |

| C15 | 0.14–2.10 | 1.2 | 0.1–7.25 | 1.17 | 0.22–4.63 | 1.88 |

| C16 | 0.31–1.54 | 0.67 | 0.04–6.07 | 1.23 | 0.17–8.1 | 1.65 |

| C17 | 0.2–3.1 | 1.43 | 0.07–9.3 | 1.93 | 0.28–13.7 | 2.4 |

| C18 | 0.05–3.3 | 1.07 | 0.04–7.68 | 1.88 | 0.19–13.18 | 2.28 |

| Pristane | 0.4–3.3 | 1.37 | 0.52–5.7 | 1.44 | 0.19–5.44 | 1.9 |

| Phytane | 0.3–3.6 | 1.8 | 0.2–9.3 | 2.57 | 0.24–9.8 | 2.66 |

| C19 | 0.1–2 | 1.28 | 0.15–6.55 | 1.67 | 0.24–8.5 | 2.12 |

| C20 | 0.16–1.83 | 0.81 | 0.05–7.05 | 1.98 | 0.18–9.88 | 2.37 |

| C21 | 0.16–1.6 | 0.8 | 0.14–6.14 | 1.65 | 0.02–8.87 | 1.99 |

| C22 | 0.01–3.85 | 1.1 | 0.1–5.3 | 1.55 | 0.03–8.28 | 1.7 |

| C23 | 0.09–1.12 | 0.5 | 0.12–3.8 | 1.02 | 0.02–2.26 | 1.29 |

| C24 | 0.13–0.9 | .048 | 0.11–3.03 | 0.87 | 0.01–5 | 1.13 |

| C25 | 0.13–1.63 | 0.82 | 0.15–3.5 | 0.98 | 0.03–3.18 | 1.3 |

| C26 | ND - 1.09 | 0.63 | 0.02–2.14 | 0.6 | ND - 2.03 | 0.69 |

| C27 | 0.02–6.1 | 1.4 | ND - 2.02 | 1.15 | 0.01–4.7 | 0.77 |

| C28 | ND - 0.9 | 0.32 | 0.01–0.11 | 0.25 | 1- ND | 0.05 |

| C29 | ND - 4.28 | 1.13 | ND - 1.14 | 0.57 | ND - 2.55 | 0.44 |

| C30 | ND - 0.3 | 0.06 | ND - 1.03 | 0.06 | ND - 0.23 | 0.17 |

| C31 | ND - 1.96 | 0.4 | ND - 0.42 | 0.37 | ND - 1.33 | 0.19 |

| C32 | 0.01–0.22 | 0.07 | ND - 0.98 | 0.32 | ND - 3.06 | 0.13 |

| C33 | 0.01–0.45 | 0.09 | ND - 0.06 | 0.35 | ND - 3.45 | 0.02 |

| C34 | ND - 2.15 | 0.36 | ND - 0.07 | 0.04 | ND - 0.3 | 0.02 |

| C35 | ND - 0.13 | 0.03 | ND - 0.01 | 0.06 | ND - 0.47 | – |

| Σ n-alkane | 3.1–28.2 | 16.8 | 2.2–76.9 | 21.7 | 4.9–99.4 | 26 |

| Total AHs | 3.9–30.8 | 20 | 2.94–91.9 | 25.7 | 5.4–114.7 | 30.6 |

| CPI | 0.9–4.2 | 1.8 | 0.99–1.6 | 1.2 | 0.6–3 | 1.5 |

| Pr/Ph | 0.4–1.49 | 0.7 | 0.4–2.5 | 1 | 0.3–1.2 | 0.6 |

| C17/Pr | 0.4–2.1 | 1.1 | 0.1–1.9 | 0.9 | 0.4–1.6 | 0.9 |

| C18/Ph | 0.2–2.1 | 0.6 | 0.1–1.4 | 0.7 | 0.2–1 | 0.5 |

| HMW/LMW | 0.3–5.6 | 1.7 | 0.7–2.6 | 1.4 | 0.5–2.3 | 1.1 |

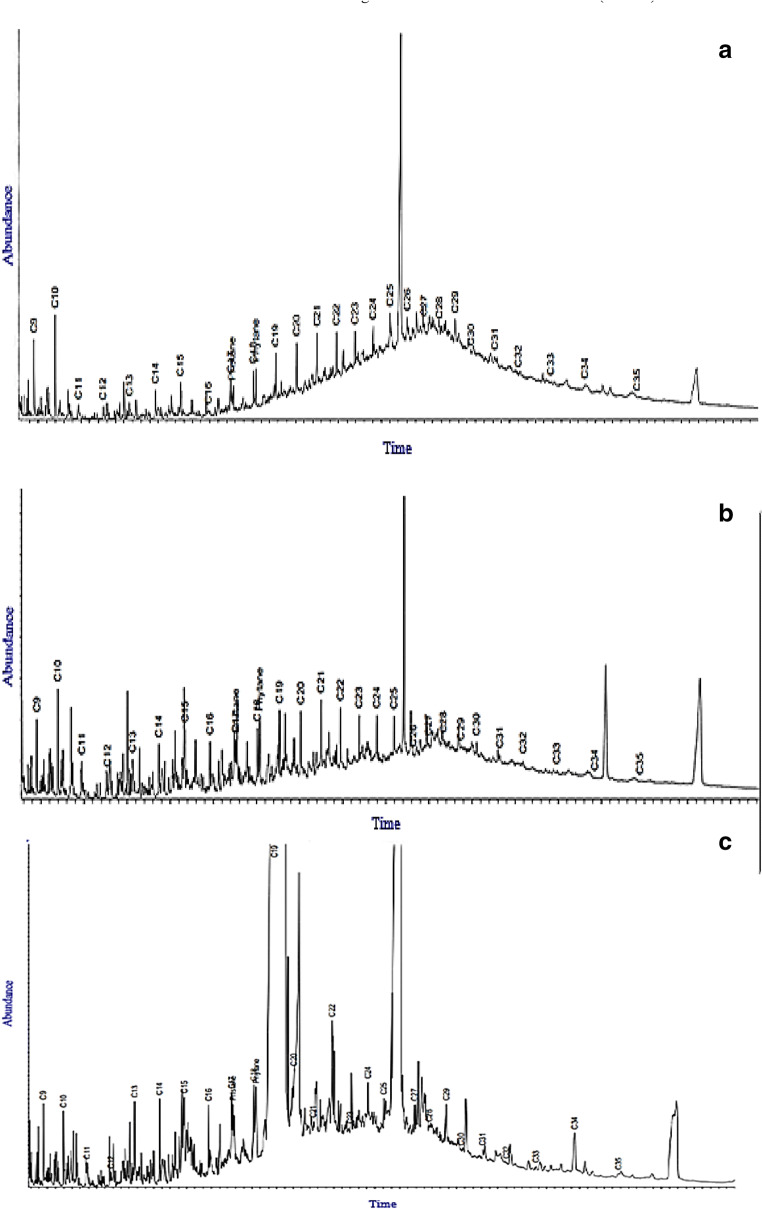

Fig. 2.

Diagrams of concentration versus carbon number for n-Alkanes in the samples: (a) Station C2S8, (b) station CCS23 and (c) C1S27

Fig. 3.

Distributions of n-alkanes and isoprenoids in the surface sediment of urban runoff, Tehran city

Our results also revealed that the concentrations of AHs are varied between stations in sub-catchments due to their specific location, whereas overall, the concentrations of n-alkanes in the upstream stations and the downstream stations are lower than those in the middle of the sub-catchments. It could be linked with (1) sediment contamination is under influence of local environmental factors and the effect of upstream sources is low; and (2) the middle parts of the sub-catchments locate in the areas with high population density and high human activities.

Source identification using molecular markers and diagnostic ratios

The use of n-alkanes as a molecular marker can be used to identification of pollution sources in aquatic environments [43]. Many mathematical ratios and biomarkers which described in numerous references [27, 28, 44] have been used to identifying the source of n-Alkanes in the environment. Figure 2 depicts that most compounds were found at significant values in the sub-catchments which indicate the matrix complexity and the variety of emission sources. High concentrations of the lower chain n-alkanes in comparison with their higher homologs in all sub-catchments can be ascribable to high anthropogenic activities [28]. However, the biomarkers and the diagnostic ratios (the major hydrocarbons and C17/Pr, C18/Ph, Pr/Ph, LMW/HMW and carbon preference index) are used to evaluate the probable sources of the hydrocarbons (anthropogenic or biogenic).

The major hydrocarbon

The major hydrocarbon denotes the highest compound concentration. Generally, significant concentrations of the most AHs depict contribution of both petrogenic and pyrogenic sources to the release of these compounds into the surface runoff of Tehran city [45]. In more detail, the dominance of short-chain compounds illustrates the dominant contribution of the petrogenic sources compare to the biogenic sources in the sub-catchments [46].The concentration of n-C18 is significant but is lower than n-C17 concentration at all stations. The sum of the peak areas of n-C18 + Ph and n-C17 + Pr in the chromatogram clearly indicate that n-C17 and n-C18 have the most intense peaks which are a strong proof of the significant contribution of petrogenic sources at all stations. The high concentrations of n-C18 and Ph were observed in urban sediment stream of São Paulo State in southeast Brazil, which indicated petroleum contamination [29]. Notably, the major hydrocarbon is Ph in all samples which is another sign of the predominance of petrogenic [46]. In addition, the second highest peak belongs to n-C20 which is also related to petrogenic sources [45]. Besides, the high concentrations of n-C15, n-C16 and n-C17 at most stations, especially in sub-catchment 2, seems to be related to the spills of heavy fuels such as gas oil leakage and spillage of fuels and petroleum derivatives are the probable anthropogenic source of petrogenic inputs to Tehran’s urban runoff sedimentary. It’s different from the results of similar studies on surficial sediment of some rivers which indicate the predominance of biogenic resources (marine and/or terrestrial) in comparison to petrogenic [47, 48].

The carbon preference index

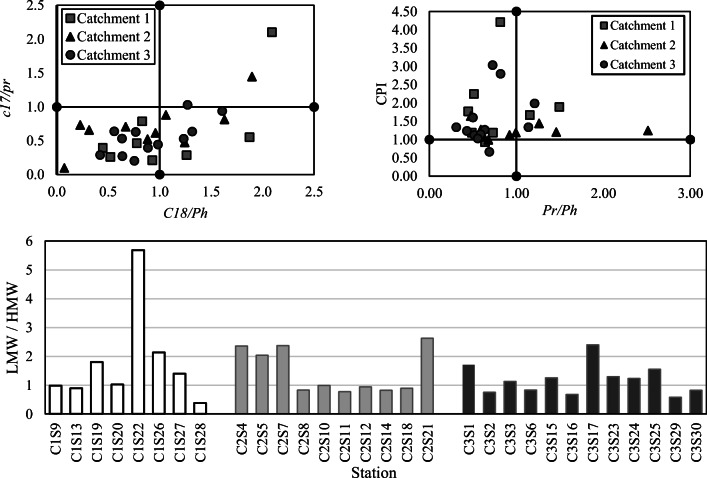

The carbon preference index (CPI) of n-Alkanes is defined as the ratio of the odd to the even carbon numbered n-alkanes [49]. It is a robust indicator for the identification of hydrocarbons’ sources from vascular plants versus fossil fuel contamination [50]. It indicates the relative contribution of biogenic (CPI > 4) and petrogenic (CPI ≈ 1) sources [51]. The CPI computed values ranged from 0.7 to 3, except the station C1S28 (CPI = 4.2). The CPI values are less than 1.6 at 70% of the stations (except stations C1S13, C1S19, C1S22, C1S26, C1S28, C2S14, C3S15, C3S16, C3S29 and C3S30), which confirms the anthropogenic nature of the hydrocarbons’ sources [52]. values of this index at most stations were similar to those reported in coastal areas (0.62–1.7) which affected by urban runoff [53]. A possible explanation for relatively high values of this index at some stations might be the fact that plants produce long-chain compounds in warmer climates [54]. For example, the highest calculated values of the ratio were 3 and 4.2 at stations C1S28 and C3S29, respectively which are located in crop fields in the south of Tehran. The concentrations of n-C27, n-C29, n-C31 and n-C33 were significant. as a result, the index values were also higher than other stations whose most important biogenic hydrocarbon contribution is associated with terrestrials inputs [55]. The higher abundance of n-C27 and n-C29 than n-C31 at all stations, suggests higher contribution of plants as a sediment contamination source [56], due to the dominance of trees comparative to grasses in the streets of the study area. The abundance of these compounds has reported in Surface Sediments of Strategic Areas of the Western Moroccan Mediterranean Sea which is assigned to a terrestrial biologic origin more precisely linked to the superior plants [53]. On the other hand, the significant concentrations of n-alkanes between n-C20 and n-C24 represent the dominance of petroleum sources at most stations [45]. In general, this index demonstrates n-alkanes in the surface sediment of runoff are affected by a combination of the petrogenic and the biogenic sources, while the contribution of petrogenic is dominant at most of the stations. In addition, natural plants’ waxes are the most important biogenic source of these compounds in the catchment of Tehran. The predominance of petrogenic origins in sediments of Yellow river estuary which affected by urban runoff has been proven [57]. The contribution of the petrogenic sources of n-alkanes in the respirable particles in Tehran, as one of the contamination inputs to the runoff, is reported more than 65% [58]. The results of some studies have also confirmed the petrogenic sources as the major contributor to AHs emission in urban runoff. Besides, waxes of terrestrial plants provide an important contribution of natural hydrocarbons in urban areas [9, 42, 59]. Generally, The highly populated and neighborhoods of industrial areas show anthropogenic interferences as the main contamination sources of streams; however, in sparsely populated areas most hydrocarbons are originated from biogenic sources [29].

The ratio of low to high molecular weight n-alkanes

The ratio of low to high molecular weight n-alkanes (LMW/HMW) is the fraction of the sum of n-alkanes ˂ n-C20 to the sum of n-alkanes > n-C21. The values close to 1 specify petroleum, phytoplankton or algae sources and commonly have lower values in higher plants, animals, and sedimentary transformations, while >2 is typically indicative of fresh petroleum compounds in the environment [60]. This index is close to 1 at most of the stations which confirms the petroleum origin of the contamination, and lower values at some stations including C1S28 (0.4), C3S29 (0.6) and C3S16 (0.7) could be attributed to the biogenic sources. The values of CPI for the mentioned stations confirm the significant contribution of the biogenic sources, in particular the vascular plants. Considering the flora of the study area, the high levels of odd number HMW n-alkanes in the urban runoff can originate from the vascular plants [16]. As a result, the significant concentrations of some n-alkanes with plant origins have led to a decrease in this index. Moreover, the higher biodegradation of LMW compounds in the sediments can be a reason for the low values of this index in the mentioned stations [61]. The values of the ratio showed the number of the stations which affected by fresh petroleum compounds in sub-catchment 2 (C2S4, C2S5, C2S7 and C2S21) which are more than other sub-catchments (C1S22, C3S17), as a result of the higher population density and activities and the heavy traffic. Overall, according to Ines et al. (2013), the presence of the lighter n-alkanes indicates recent input of hydrocarbons in these stations as waste fuels and petroleum compounds [45].

The ratio of Pristane to Phytane (Pr/Ph)

Generally, the concentrations of Pristane (Pr) and Phytane (Ph) are almost equal in petroleum-contaminated samples [60]. The early formation rates of Pr and Ph are the same, but the decomposition of Ph is slightly faster than Pr. Therefore high concentrations of Pr may be indicative of a high level of microbial degradation [62]. Hence, the ratio of Pr to Ph (Pr/Ph) close to 1 indicates the petrogenic contamination and values from 1.4 to 6.7 specify the dominance of the biogenic or the natural sources [63]. The Pr/Ph values ranged from 0.3 to 1.5 at all stations except for C2S10 with a value of 2.5. The mean values of this index for sub-catchments 1, 2 and 3 are 0.8, 1 and 0.7, respectively that indicate the petrogenic sources are predominant in a sub-catchment scale. Generally, the low values of this ratio observe in more than 76% of stations may reveal that the contaminations are probably historically and/or chronically petrogenic with continuous input of the biogenic origin [64]. The presence of Pr and Ph with the low values of C17/Pr and C18/Ph (˂5) confirm the microbial activity in the runoff sediments [65]. Moreover, the mean concentrations of Ph were higher than Pr at 21 stations which reflect the dominance of the petrogenic sources over the biogenic sources [46]. These results suggested a possible petrogenic origin for the hydrocarbons as well as the weak microbial degradation at all stations [29, 66].

The ratio of isoprenoid to n-alkane

The ratios of n-C17/Pr and n-C18/Ph are often used for evaluation of the relative (short to mid-term) biodegradation of n-alkanes. n-C17 and n-C18 are easily degradable, while Pr and Ph have lower degradability. Therefore, the low values of these indexes suggest the presence of degraded oil while high values indicate low degradation. When the concentrations of hydrocarbons are high, the ratio > 1 indicates fresh oil inputs and < 1 shows the degradation of petroleum compounds [40, 65]. The ratios of n-C17 to Pr and n-C18 to Ph vary from 0.4 to 2.1 and 0.2 to 2.1, respectively. These figures depict the petroleum contamination is mainly due to the degraded oil products and to a lesser extent fresh oil. Both ratios were higher than 1 for the stations C1S27, C2S4 and C3S15 where field visit and map surveys revealed that C1S27 locates next to the industrial workshops and warehouses, C2S4 is in the vicinity of two fuel stations and C3S15 places in adjacent to numerous car repair shops and parking lots (Fig. 1). According to the results of our previous study on PAHs in these sub-catchments, the petrogenic sources were predominant in the mentioned stations [67]. While in the other stations, the values lower than 1 along with the high concentrations of hydrocarbons indicate the significant biodegradation of hydrocarbons in the samples. In particular, the ratios of n-C18/Ph were relatively low (0.2–1) with high concentrations of hydrocarbons which indicate the microbial degradation processes are generally important in the study area, except for C2S4 and C1S27 [68]. The significant concentration of compounds between n-C16 and n-C22 at most stations can be attributed to microbial degradation of organic matter [9], which confirmed the microbial degradation processes in the whole catchment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of diagnostic ratios

Total organic carbon

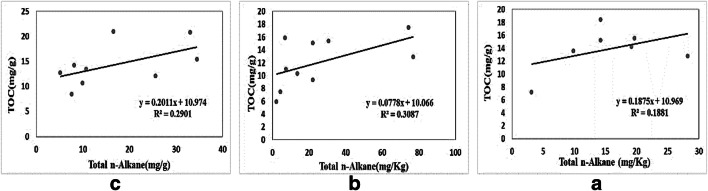

Aliphatics are hydrophobic compounds with a tendency to sorb to organic matters in the aquatic environment. Hence, organic matter plays a key role in the distribution of many organic pollutants among different media [69]. total organic carbon content (TOC) in the sediments ranged from 7.2 to18.4, 5.9 to 17.4 and 8.4 to 21 mg.g−1 dw with the overall mean 13.3,12 and 14.7 mg.g−1 dw in the sub-catchments 1, 2 and 3, respectively (Fig. 5). One-way ANOVA reveals no significant difference among the concentrations of TOC in the sub-catchments, which means possible homogeneity of the origins and loads of emissions in the sub-catchments. TOC values measured in sub-catchment 3 were generally higher than corresponding TOC values in the other catchments’ sediments. It could be due to the higher density of vegetation in this sub-catchment compared to the others. Plant growth and subsequent mummification of dead plant material could be led to high TOC content observed in the catchments’ sediment. Pearson correlation test demonstrates a weak correlation between the concentrations of n-alkanes and TOC (P > 0.05) with correlation coefficients of 0.22, 0.54 and 0.36 in the sub-catchments 1, 2 and 3, respectively. This relationship was further checked in plots of TOC against total n-Alkanes. The plots showed a straight line with correlation coefficient 0.18, 0.3 and 0.29 in the sub-catchments (Fig. 6). This result is in agreement with other studies [70–72], while some researchers reported a significant positive correlation between these two variables [73, 74].

Fig. 5.

Distribution of total organic carbon content in the sub-catchments

Fig. 6.

The correlation between the total organic carbon content and the total n-alkanes in the sediment samples in (a) sub-catchment 1, (b) sub-catchment 2, and (c) sub-catchment 3

Conclusions

This study represents the spatial distribution and origin of aliphatic hydrocarbons include n-alkanes (n-C11–35), isoprenoids (Pr and Ph) in thirty surface sediment samples which were collected from Tehran’s runoff network. The concentrations of AHs in the sediment samples varied among the stations, while the highest concentrations were observed in the stations of densely populated and high traffic areas. This could be a result of the continuous deposition of hydrocarbons derived from different pollutant sources. The mix of the contamination sources in the Tehran region confirms the complexity of the contaminant loads transport by the runoff drainage channels. The maximum total concentrations were observed in the stations with a high density of population and activities. The level of sediment contamination with the aliphatic compounds was found low to moderate at all catchments. The variation of the AHs concentration along each sub-catchment indicates the contamination levels are affected by the local activities. This investigation showed that the sedimentary hydrocarbons contain a mixture of compounds from natural and anthropogenic sources, but the dominance of each source depends on the location of stations. Petroleum products were identified as the major source of the AHs in the urban runoff the catchment, while the waxes of vascular plants and the microbial activities also recognized as an important contribution of the natural hydrocarbons. However, it is difficult to determine the exact type and the contribution of each source due to the complexity of the sample texture as well as the high diversity of the source of AHs. The results provide a comprehensive overview of the content of AHs found in the runoff sediment in Tehran. Given the significant hydrocarbons concentrations in the sediments of urban runoff in Tehran city, since the water and associated sediments are used in the agricultural fields as well as discharge to the protected areas of environment. Therefore, future studies should focus on the fate and transport of these pollutants in the receiving environments and their health and ecological impacts.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Total Organic Carbon (TOC)

Soxhlet Extraction Method

Loss on Ignition (LOI)

The least significant difference (LSD)

Pristane (Pr)

Phytane (Ph)

n-Alkane

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Khiadani M, Zarrabi M, Foroughi M. Urban runoff treatment using nano-sized iron oxide coated sand with and without magnetic field applying. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2013;11(1):43. doi: 10.1186/2052-336X-11-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Hurk P, Haney DC. Biochemical effects of pollutant exposure in fish from urban creeks in Greenville, SC (USA) Environ Monit Assess. 2017;189(5):211. doi: 10.1007/s10661-017-5918-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Andrade LC, Coelho FF, Hassan SM, Morris LA, de Oliveira Camargo FA. Sediment pollution in an urban water supply lake in southern Brazil. Environ Monit Assess. 2019;191(1):12. doi: 10.1007/s10661-018-7132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gnecco I, Berretta C, Lanza L, La Barbera P. Storm water pollution in the urban environment of Genoa, Italy. Atmos Res. 2005;77(1–4):60–73. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howitt JA, Mondon J, Mitchell BD, Kidd T, Eshelman B. Urban stormwater inputs to an adapted coastal wetland: role in water treatment and impacts on wetland biota. Sci Total Environ. 2014;485:534–544. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.03.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanedar A, Alp K, Kaynak B, Baek J, Avsar E, Odman MT. Concentrations and sources of PAHs at three stations in Istanbul, Turkey. Atmos Res. 2011;99(3–4):391–399. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanedar A, Alp K, Kaynak B, Avşar E. Toxicity evaluation and source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) at three stations in Istanbul, Turkey. Sci Total Environ. 2014;488:437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.11.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Zhang S, Wang L, Zhang W, Shi X, Lu X, Li X, Li X. Concentration and risk evaluation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban soil in the typical semi-arid city of Xi’an in Northwest China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(4):607. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanches Filho PJ, Böhm EM, Böhm GM, Montenegro GO, Silveira LA, Betemps GR. Determination of hydrocarbons transported by urban runoff in sediments of São Gonçalo Channel (Pelotas–RS, Brazil) Mar Pollut Bull. 2017;114(2):1088–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paule-Mercado MCA, Salim I, Lee B-Y, Lee C-H, Jahng D. Intra-event variability of bacterial composition in stormwater runoff from mixed land use and land cover catchment. Membr Water Treat. 2019;10(1):29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Göbel P, Dierkes C, Coldewey W. Storm water runoff concentration matrix for urban areas. J Contam Hydrol. 2007;91(1–2):26–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jconhyd.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye B, Zhang Z, Mao T. Petroleum hydrocarbon in surficial sediment from rivers and canals in Tianjin, China. Chemosphere. 2007;68(1):140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartlett A, Rochfort Q, Brown L, Marsalek J. Causes of toxicity to Hyalella azteca in a stormwater management facility receiving highway runoff and snowmelt. Part I: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and metals. Sci Total Environ. 2012;414:227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maciel DC, de Souza JRB, Taniguchi S, Bícego MC, Schettini CAF, Zanardi-Lamardo E. Hydrocarbons in sediments along a tropical estuary-shelf transition area: sources and spatial distribution. Mar Pollut Bull. 2016;113(1):566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martins CC, Bícego MC, Taniguchi S, Montone RC. Aliphatic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarctica. Antarct Sci. 2004;16(2):117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeng W-L, Huh C-A. A comparison of sedimentary aliphatic hydrocarbon distribution between the southern Okinawa trough and a nearby river with high sediment discharge. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2006;66(1–2):217–224. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akhbarizadeh R, Moore F, Keshavarzi B, Moeinpour A. Aliphatic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons risk assessment in coastal water and sediments of Khark Island, SW Iran. Mar Pollut Bull. 2016;108(1–2):33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolaus EM, Law RJ, Wright SR, Lyons BP. Spatial and temporal analysis of the risks posed by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, polychlorinated biphenyl and metal contaminants in sediments in UK estuaries and coastal waters. Mar Pollut Bull. 2015;95(1):469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou R, Qin X, Peng S, Deng S. Total petroleum hydrocarbons and heavy metals in the surface sediments of Bohai Bay, China: long-term variations in pollution status and adverse biological risk. Mar Pollut Bull. 2014;83(1):290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang M, Wang C, Hu X, Zhang H, He S, Lv S. Distributions and sources of petroleum, aliphatic hydrocarbons and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surface sediments from Bohai Bay and its adjacent river, China. Mar Pollut Bull. 2015;90(1–2):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azimi A, Bakhtiari AR, Tauler R. Chemometrics analysis of petroleum hydrocarbons sources in the street dust, runoff and sediment of urban rivers in Anzali port-south of Caspian Sea. Environ Pollut. 2018;243:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yunker MB, Macdonald RW. Alkane and PAH depositional history, sources and fluxes in sediments from the Fraser River basin and strait of Georgia, Canada. Org Geochem. 2003;34(10):1429–1454. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cortes J, Suspes A, Roa S, Gonzãlez C, Castro H. Total petroleum hydrocarbons by gas chromatography in Colombian waters and soils. Am J Environ Sci. 2012;8(4):396. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turki A. Distribution and sources of aliphatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments of Al-Arbaeen lagoon, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Fish Livest Prod. 2016;4(2):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simoneit BR. Diterpenoid compounds and other lipids in deep-sea sediments and their geochemical significance. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1977;41(4):463–476. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourbonniere RA, Meyers PA. Anthropogenic influences on hydrocarbon contents of sediments deposited in eastern Lake Ontario since 1800. Environ Geol. 1996;28(1):22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jafarabadi AR, Dashtbozorg M, Bakhtiari AR, Maisano M, Cappello T. Geochemical imprints of occurrence, vertical distribution and sources of aliphatic hydrocarbons, aliphatic ketones, hopanes and steranes in sediment cores from ten Iranian Coral Islands, Persian gulf. Mar Pollut Bull. 2019;144:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jafarabadi AR, Bakhtiari AR, Aliabadian M, Toosi AS. Spatial distribution and composition of aliphatic hydrocarbons, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and hopanes in superficial sediments of the coral reefs of the Persian Gulf, Iran. Environ Pollut. 2017;224:195–223. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Awan AT, Niño LR, Paix MDA, Mozeto AA, Fadini PS. Urban stream vulnerability toward PAHs and n-alkanes and their source identification. Polycycl Aromat Compd. 2018;38(3):294–309. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanzari F, Syakti A, Asia L, Malleret L, Piram A, Mille G, et al. Distributions and sources of persistent organic pollutants (aliphatic hydrocarbons, PAHs, PCBs and pesticides) in surface sediments of an industrialized urban river (Huveaune), France. Sci Total Environ. 2014;478:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bayat J, Hashemi S, Khoshbakht K, Deihimfard R, Shahbazi A, Momeni-Vesalian R. Monitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on agricultural lands surrounding Tehran oil refinery. Environ Monit Assess. 2015;187(7):451. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4646-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hani A, Pazira E, Manshouri M, Kafaky SB, Tali MG. Spatial distribution and mapping of risk elements pollution in agricultural soils of southern Tehran, Iran. Plant Soil Environ. 2010;56(6):288–296. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayat J, Hashemi SH, Khoshbakht K, Deihimfard R. Fingerprinting aliphatic hydrocarbon pollutants over agricultural lands surrounding Tehran oil refinery. Environ Monit Assess. 2016;188(11):612. doi: 10.1007/s10661-016-5614-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramyar R, Saeedi S, Bryant M, Davatgar A, Hedjri GM. Ecosystem services mapping for green infrastructure planning–the case of Tehran. Sci Total Environ. 2020;703:135466. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghahroudi Tali M, Derafshi KB. Investigation of turbulence in the pattern of flood risk in Tehran city. J Spatial Anal Environ Hazarts. 2015;2:1–16.

- 36.Moopam R. Manual of oceanographic observations and pollutant analysis methods. ROPME Kuwait. 1999;1:20. [Google Scholar]

- 37.(DIN) Soil Improvers And Growing Media - Determination Of Organic Matter Content And Ash; German Version EN 13039. 2012

- 38.Duong HT, Kadokami K, Pan S, Matsuura N, Nguyen TQ. Screening and analysis of 940 organic micro-pollutants in river sediments in Vietnam using an automated identification and quantification database system for GC–MS. Chemosphere. 2014;107:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volkman JK, Holdsworth DG, Neill GP, Bavor H., Jr Identification of natural, anthropogenic and petroleum hydrocarbons in aquatic sediments. Sci Total Environ. 1992;112(2–3):203–219. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(92)90188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Commendatore MG, Nievas ML, Amin O, Esteves JL. Sources and distribution of aliphatic and polyaromatic hydrocarbons in coastal sediments from the Ushuaia Bay (Tierra del Fuego, Patagonia, Argentina) Mar Environ Res. 2012;74:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dauner ALL, Hernández EA, MacCormack WP, Martins CC. Molecular characterisation of anthropogenic sources of sedimentary organic matter from potter cove, King George Island, Antarctica. Sci Total Environ. 2015;502:408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bomboi M, Hernandez A. Hydrocarbons in urban runoff: their contribution to the wastewaters. Water Res. 1991;25(5):557–565. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adeniji A, Okoh O, Okoh A. Petroleum hydrocarbon fingerprints of water and sediment samples of Buffalo River estuary in the eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J Anal Methods Chem. 2017;2017:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2017/2629365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shirneshan G, Bakhtiari AR, Memariani M. Identifying the source of petroleum pollution in sediment cores of southwest of the Caspian Sea using chemical fingerprinting of aliphatic and alicyclic hydrocarbons. Mar Pollut Bull. 2017;115(1–2):383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ines Z, Amina B, Mahmoud R, Dalila S-M. Aliphatic and aromatic biomarkers for petroleum hydrocarbon monitoring in Khniss Tunisian-coast,(Mediterranean Sea) Procedia Environ Sci. 2013;18:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z, Fingas MF. Development of oil hydrocarbon fingerprinting and identification techniques. Mar Pollut Bull. 2003;47(9–12):423–452. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(03)00215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Darilmaz E. Aliphatic hydrocarbons in coastal sediments of the northern Cyprus (eastern Mediterranean) Environ Earth Sci. 2017;76(5):220. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanil Kumar K, Nair S, Salas P, Prashob Peter K, Ratheesh KC. Aliphatic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contamination in surface sediment of the Chitrapuzha River, South West India. Chem Ecol. 2016;32(2):117–135. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bray E, Evans E. Distribution of n-paraffins as a clue to recognition of source beds. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1961;22(1):2–15. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boehm PD, Requejo A. Overview of the recent sediment hydrocarbon geochemistry of Atlantic and Gulf Coast outer continental shelf environments. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 1986;23(1):29–58. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Saad HT, Farid WA, Ateek AA, Sultan AWA, Ghani AA, Mahdi S. n-Alkanes in surficial soils of Basrah city. Southern Iraq. Int J Mar Sci. 2015;5(52):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanches Filho PJ, Luz LPd, Betemps GR, Silva MDRGd, Caramão EB. Studies of n-alkanes in the sediments of colony Z3 (Pelotas-RS-Brazil). Braz J Aquat Sci Technol Itajaí, SC Vol 17, n 1 (2013), p 27–33. 2013.

- 53.Bouzid S, Raissouni A, Khannous S, Arrim AE, Bouloubassi I, Saliot A, et al. Distribution and origin of aliphatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments of strategical areas of the western Moroccan Mediterranean Sea. Open Environ Pollut Toxicol J. 2012;3(1).

- 54.Simoneit BR, Sheng G, Chen X, Fu J, Zhang J, Xu Y. Molecular marker study of extractable organic matter in aerosols from urban areas of China. Atmos Environ Part A. 1991;25(10):2111–2129. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tran K, Yu CC, Zeng EY. Organic pollutants in the coastal environment off San Diego, California. 2. Petrogenic and biogenic sources of aliphatic hydrocarbons. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1997;16(2):189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meyers PA. Applications of organic geochemistry to paleolimnological reconstructions: a summary of examples from the Laurentian Great Lakes. Org Geochem. 2003;34(2):261–289. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang S, Liu G, Yuan Z, Da C. N-alkanes in sediments from the Yellow River estuary, China: occurrence, sources and historical sedimentary record. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018;150:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moeinaddini M, Sari AE, Chan AY-C, Taghavi SM, Hawker D, Connell D. Source apportionment of PAHs and n-alkanes in respirable particles in Tehran, Iran by wind sector and vertical profile. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2014;21(12):7757–7772. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoffman EJ, Latimer JS, Mills GL, Quinn JG. Petroleum Hydrocarbons in Urban Runoff from a Commerical Land Use Area. J Water Pollut Control Fed. 1982:1517–25.

- 60.Gearing P, Gearing JN, Lytle TF, Lytle JS. Hydrocarbons in 60 Northeast Gulf of Mexico shelf sediments: a preliminary survey. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1976;40(9):1005–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang J, Dai J, Du X, Li F, Wang W, Wang R. Distribution and sources of petroleum-hydrocarbon in soil profiles of the Hunpu wastewater-irrigated area, China's northeast. Geoderma. 2012;173:215–223. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wakeham SG, Carpenter R. Aliphatic hydrocarbons in sediments of Lake Washington 1. Limnol Oceanogr. 1976;21(5):711–723. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mille G, Asia L, Guiliano M, Malleret L, Doumenq P. Hydrocarbons in coastal sediments from the Mediterranean Sea (gulf of Fos area, France) Mar Pollut Bull. 2007;54(5):566–575. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) Chemicals. Master list of actions: on the reduction and/or elimination of the releases of persistent organic pollutants. Geneva: UNEP Chemicals; 2003.

- 65.Columbo J, Pelletier C, Brochu A, Khalil M, Catoggio J. Determination of hydrocarbons sources using n-alkanes and polyaromatic hydrocarbons distribution indexes. Environ Sci Technol. 1989;23:888–894. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moilleron R, Gonzalez A, Chebbo G, Thévenot DR. Determination of aliphatic hydrocarbons in urban runoff samples from the “Le Marais” experimental catchment in Paris Centre. Water Res. 2002;36(5):1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(01)00322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hashemi SH, Hasani Moghaddam A, Ghadiri A. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Urban Runoff Sediments (Case Study: Tehran City, Amirkabir). J Civ Eng. 2019. 10.22060/ceej.2019.16098.6124.

- 68.Ezra S, Feinstein S, Pelly I, Bauman D, Miloslavsky I. Weathering of fuel oil spill on the East Mediterranean coast, Ashdod, Israel. Org Geochem. 2000;31(12):41–1733. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shi Z, Tao S, Pan B, Liu W, Shen W. Partitioning and source diagnostics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in rivers in Tianjin, China. Environ Pollut. 2007;146(2):492–500. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zamani-Ahmadmahmoodi R, Esmaili-Sari A, Mohammadi J, Bakhtiari AR, Savabieasfahani M. Spatial distribution of cadmium and lead in the sediments of the western Anzali wetlands on the coast of the Caspian Sea (Iran) Mar Pollut Bull. 2013;74(1):464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang X-C, Sun S, Ma H-Q, Liu Y. Sources and distribution of aliphatic and polyaromatic hydrocarbons in sediments of Jiaozhou Bay, Qingdao, China. Mar Pollut Bull. 2006;52(2):129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Commendatore M, Esteves J. Natural and anthropogenic hydrocarbons in sediments from the Chubut River (Patagonia, Argentina) Mar Pollut Bull. 2004;48(9–10):910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bakhtiari AR, Zakaria MP, Yaziz MI, Lajis MNH, Bi X, Shafiee MM, et al. Distribution of PAHs and n-alkanes in Klang River surface sediments, Malaysia Pertanika. J Sci Technol. 2010;18(1):167–179. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harris KA, Yunker MB, Dangerfield N, Ross PS. Sediment-associated aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons in coastal British Columbia, Canada: concentrations, composition, and associated risks to protected sea otters. Environ Pollut. 2011;159(10):2665–2674. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]