Abstract

In female mammals, meiotic prophase one begins during fetal development. Oocytes transition through the prophase one substages consisting of leptotene, zygotene, and pachytene, and are finally arrested at the diplotene substage, for months in mice and years in humans. After puberty, luteinizing hormone induces ovulation and meiotic resumption in a cohort of oocytes, driving the progression from meiotic prophase one to metaphase two. If fertilization occurs, the oocyte completes meiosis two followed by fusion with the sperm nucleus and preparation for zygotic divisions; otherwise, it is passed into the uterus and degenerates. Specifically in the mouse, oocytes enter meiosis at 13.5 days post coitum. As meiotic prophase one proceeds, chromosomes find their homologous partner, synapse, exchange genetic material between homologs and then begin to separate, remaining connected at recombination sites. At postnatal day 5, most of the oocytes have reached the late diplotene (or dictyate) substage of prophase one where they remain arrested until ovulation. This review focuses on events and mechanisms controlling the progression through meiotic prophase one, which include recombination, synapsis and control by signaling pathways. These events are prerequisites for proper chromosome segregation in meiotic divisions; and if they go awry, chromosomes mis-segregate resulting in aneuploidy. Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms regulating meiotic progression is important to provide a foundation for developing improved treatments of female infertility.

Keywords: meiosis, diplotene arrest, oocyte development, synaptonemal complex, recombination, primordial follicle formation

Introduction: Mammalian Oocyte Development and Meiosis

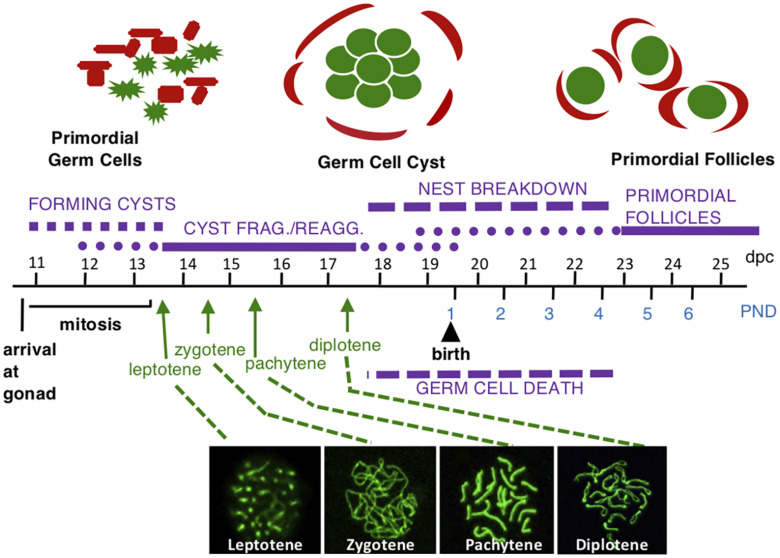

Meiosis is a special type of cell division that generates haploid gametes important for sexual reproduction. In meiosis, cells replicate their DNA once, followed by two rounds of division: meiosis one (MI)- a reductional division, and then meiosis two (MII)-an equational division analogous to mitotic division. In the mammalian female embryo, meiotic division of the oocyte is preceded by several rounds of mitosis. Oocytes differentiate from primordial germ cells (PGCs) that migrate to the genital ridge starting at 10.5 days post coitum (dpc) in the mouse (see Figure 1; Molyneaux et al., 2001). The germs cells divide by mitosis until 13.5 dpc and are referred to as oogonia during this time. However, cytokinesis is not complete and the oogonia remain connected by intercellular bridges in structures called germ cell cysts (Pepling and Spradling, 1998). Oogonia enter meiosis in a wave from anterior to posterior and become oocytes beginning at 13.5 dpc in the mouse (Menke et al., 2003; Bullejos and Koopman, 2004). Oocytes remain associated during fetal development though cysts may fragment and reassociate as germ cell nests (Lei and Spradling, 2013). Oocytes gradually arrest near the end of prophase one with some oocytes reaching arrest as early as 17.5 dpc and most by postnatal day (PND) 5 (Cohen et al., 2006). Concurrently, the oocytes contained in germ cell nests separate and each individual oocyte is surrounded by somatic pregranulosa cells forming structures called primordial follicles (Pepling and Spradling, 2001). As oocytes separate and follicles form, a large number of oocytes are lost by programmed cell death that in part aid in individualization of surviving cells (Greenfeld et al., 2007). In addition, other potential functions of germ cell loss have been proposed including selection for the highest quality oocytes or as support for a subset of the cyst cells (Pepling et al., 1999). More recent work has provided evidence that some oocytes play a supporting role similar to nurse cells in Drosophila (Lei and Spradling, 2016). Thus, a pool of primordial follicles each containing an oocyte arrested at the end of prophase one is established and represents the population of germ cells available for the reproductive lifespan in female mammals (Pepling, 2012). Human and mouse germ cells progress through these developmental processes analogously, except that the process in mouse is accelerated likely due to their shorter lifespan and primordial follicle formation in humans is completed during fetal development (Hartshorne et al., 2009).

FIGURE 1.

Mouse female germ cell development. Germ cells are shown in green and somatic cells are shown in red above timeline. At 10.5 dpc, germ cells migrate to the gonad and begin rapidly dividing by mitosis, forming germ cell cysts. Some cysts fragment into smaller cysts and reassociate with unrelated cysts to form nests where some cells are still connected by intercellular bridges with others associated by aggregation. Beginning at 13.5 dpc, oogonia enter meiotic prophase one to become oocytes and progress through meiotic prophase one substages: leptotene, zygotene, pachytene, and diplotene (with representative surface spread nuclei labeled with SYCP3 in green shown below the timeline). The arrow for each substage indicates the first day oocytes are found in the indicated substage. Oocytes are found in each substage for several days. The oocytes arrest at the diplotene stage starting at 17.5 dpc. At this time, germ cell nests begin to breakdown and oocytes that are not lost due to apoptosis are surrounded by somatic cells forming primordial follicles.

In sexually mature females, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates granulosa cell proliferation and estradiol production, inducing a preovulatory surge of luteinizing hormone (LH) which triggers meiotic resumption (Mcgee and Hsueh, 2000). This drives meiotic progression from prophase one to metaphase two. The oocyte is ovulated after the LH surge and becomes arrested in metaphase two. If fertilization occurs, the MII division is completed and followed by DNA replication in preparation for the first zygotic division; otherwise, the oocyte is passed to the uterus and disintegrates. Proper meiotic progression is important as aneuploidy, an abnormal number of chromosomes per cell occurs in at least 5% of all clinically recognized pregnancies (Hassold and Hunt, 2001). It has been estimated that women over 35 suffer from a greater risk of aneuploidy, resulting in a dramatic increase of infertility, miscarriage, and birth defects (Herbert et al., 2015).

While meiosis evolved from mitosis, novel steps were acquired that include pairing and recombination between homologous chromosomes, the inhibition of sister-chromatid separation during meiosis one (MI), and the absence of DNA replication during MII (Wilkins and Holliday, 2009). Following premeiotic DNA replication, germ cells enter an extended MI prophase which is further divided into four substages called leptotene, zygotene, pachytene, and diplotene based on cytology (Borum, 1961). During the leptotene stage, the earliest stage, chromosomes have not yet condensed and appear relatively long. In the zygotene stage, homologs begin to pair by a process called synapsis and start to condense. The pachytene stage is the third and longest stage of prophase one. By the start of the pachytene stage, the paired homologous chromosomes have become fully synapsed and by the end of this stage, chromosomes appear shortest and highly condensed. Toward the end of prophase one, homologs separate from each other marking entry into the diplotene stage. Homologous chromosomes remain physically connected at chiasmata which represent regions where crossing over has occurred during recombination which is the exchange of genetic material (Bolcun-Filas and Schimenti, 2012). It is thought that oocytes arrest in the diplotene substage because this is the most stable conformation of chromosomes as oocytes may remain at this stage until ovulation occurring months later in mice and years later in humans (Hartshorne et al., 2009). The significance of prophase one events for ensuring accurate chromosome segregation is underlined by the observation that most aneuploidies result from chromosome non-disjunction during the first meiotic division (Morelli and Cohen, 2005). This review describes recent findings on meiotic prophase one progression in mammalian oocytes up to the dictyate stage, with some reference to analogous events in mouse spermatocytes and yeast. By understanding what is known in the mouse model, we may gain insights into causes of high aneuploidy rates in human females.

Recombination: Formation and Repair of Double-Strand Breaks

Double-Strand Break Formation

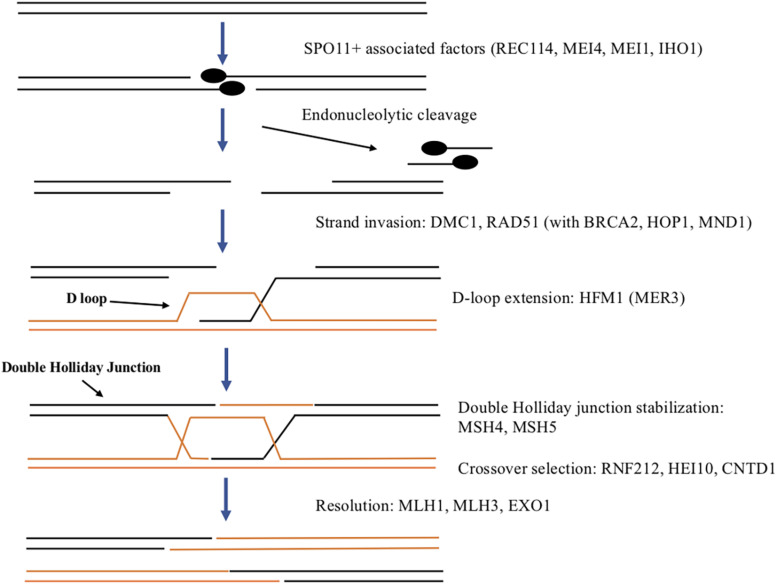

The process of recombination involves exchange of genetic material between homologous chromosomes and is initiated by generation of double-strand breaks (DSBs). In eukaryotes including mammals, DSBs are created by the SPO11 topoisomerase beginning early in prophase one (see Figure 2; Keeney, 2008). DSBs are thought to occur at recombination hotspots throughout the genome (Paigen and Petkov, 2010) and genome-wide mapping studies have identified thousands of hotspots in the mouse (Smagulova et al., 2011; Brunschwig et al., 2012). The methyltransferase, PRDM9 has been shown to be important for targeting SPO11 to recombination hotspots and is thought to direct DSB machinery to crossover sites by direct sequence-specific binding (Baudat et al., 2010; Brick et al., 2012). SPO11 creates DSBs via a transesterification reaction that cleaves the DNA backbone on both strands, with SPO11 monomers covalently attached to the 5′ ends (Keeney, 2008). SPO11-oligonucleotide (SPO11-oligo) complexes are released by endonucleolytic cleavage and serve as a by-product of DSB formation that can be used to measure DSB levels as well as distribution (Neale et al., 2005; Daniel et al., 2011). The DSBs induced by SPO11 are required for homologous chromosomes to synapse (Baudat et al., 2000; Romanienko and Camerini-Otero, 2000). In Spo11 mutant oocytes, defects in synapsis lead to the eventual loss of all oocytes (Di Giacomo et al., 2005). Many oocytes are lost even before follicles form, though oocytes remaining undergo normal primordial follicle formation and the first wave of follicles begins to develop but within 2 months all oocytes are lost. REC114, MEI4, and MEI1 have also been implicated in DSB formation in mouse (Baudat et al., 2013). REC114 and MEI4 along with IHO1 colocalize on meiotic chromosomes and have been shown to form a complex required for DSB formation. It is thought that this complex may recruit and/or regulate the catalytic activity of SPO11 (Kumar et al., 2010, 2018; Stanzione et al., 2016) In addition, MEI1 is also required for DSB formation (Libby et al., 2003) and for MEI4 localization to meiotic chromosomes (Kumar et al., 2015).

FIGURE 2.

Summary of DSB formation and repair in mammals. SPO11 and associated factors including REC114, MEI4, MEI1, and IHO1 generate a double strand break to initiate recombination. Endonuclease activity results in cleavage of a small DNA fragment associated with SPO11. The resulting single-stranded DNA overhang is extended on both DNA strands by exonuclease activity. RAD51 and DMC1 along with other proteins aid in strand invasion of the homologous chromosome to begin the process of homologous recombination to repair the DSB. This forms the D-loop on the homolog that is extended by HFM1. If the other side of the DSB is “captured” a double Holliday junction is formed and stabilized by MSH4 and MSH5. This can either resolve to a crossover or a non-crossover with RNF212, HEI10, and CNTD1 involved in regulating crossover selection. Resolution to the final crossover products is promoted by MLH1, MLH3, and EXO1.

A large number of DSBs may damage genome integrity while too few might result in deficient recombination, therefore, it is important to maintain DSB numbers within an optimal range. In yeast, orthologs of Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and Ataxia telangiectasia and RAD3-related (ATR), members of the PI3 kinase like family of protein kinases (PIKKs) are thought to work antagonistically to regulate DSB formation during mitosis and also in meiotic prophase one (Cooper et al., 2014). Mec1, the yeast ATR ortholog is able to promote DSB formation while the yeast ATM, called Tel1 appears to negatively regulate DSBs. Similarly, in the mouse, DSB formation in meiotic prophase one significantly increases in Atm null spermatocytes and excessive levels of DSBs cause severe meiotic defects resulting in infertility (Lange et al., 2011). However, overexpression of ATM does not affect the number of DSBs (Modzelewski et al., 2015). In addition, ATR does not seem to affect DSB numbers in mouse spermatocytes suggesting the balance of DSBs is regulated by a different mechanism in mice (Widger et al., 2018). There is no evidence that ATM or ATR are important for regulating DSB numbers in mouse oocytes (Pacheco et al., 2019) though in both oocytes and spermatocytes, ATM and ATR play roles in the DNA damage checkpoint and elimination of germ cells (see section “Elimination of Oocytes With Defective DNA Repair or Synapsis”). Regulation of DSB formation in mammalian oocytes may involve another kinase or feedback may be provided by factors detecting synapsis.

Double Stand Break Repair

Once DSBs are formed, they must be repaired and during this process crossovers can form. DSB repair involves end processing, strand invasion, intermediate processing and resolution with only a subset resulting in crossovers and in mouse oocytes takes about 4–5 days (Hartshorne et al., 2009). Much of our understanding of DSB repair comes from studies in yeast, flies and nematodes and the process appears to be conserved in mammals as well (reviewed in Gray and Cohen, 2016). The first step in repairing DSBs is end processing which begins with each strand of DNA being cleaved by an endonuclease releasing an oligonucleotide associated with a SPO11 monomer (see Figure 2). The cleavage is offset on one strand compared to the other leaving a two base pair overhang on each strand that is extended up to 800 bps by exonuclease activity. Recombinases RAD51 and DMC1 coat the resulting single-stranded DNA and aid in strand invasion of the homologous chromosome (Pittman et al., 1998). Several other proteins including BRCA2, HOP2, and MND1 assist RAD51 and DMC1 in strand invasion (Petukhova et al., 2005). The complementary DNA strand on the homolog is displaced forming a displacement (or D) loop. HFM1 (also called MER3) is a helicase thought to be involved in extending the D-loop (Guiraldelli et al., 2013). If a second end capture occurs, a double Holliday junction intermediate is formed and stabilized by mismatch repair proteins MSH4 and MSH5 to promote crossovers (Kneitz et al., 2000). In the mouse, several proteins participate in crossover selection including RNF212, a SUMO E3 ligase, HEI10, a ubiquitin E3 ligase, and CNTD1, a cyclin domain containing protein (Reynolds et al., 2013; Holloway et al., 2014; Qiao et al., 2014; Rao et al., 2017). Two other mismatch repair proteins MLH1 and MLH3 along with EXO1 promote resolution to crossovers (Lipkin et al., 2002). Alternatively, single end strand invasion will lead to the non-crossover pathway.

Homolog Pairing

DSB-Dependent Pairing

Homologous chromosome pairing starts at the zygotene stage and is essential for accurate homolog segregation during meiotic progression. It relies on DSB-dependent as well as DSB-independent pathways, and in recent years, many proteins have been identified that are involved in this regulation (see Table 1). DSBs mediate homolog pairing, and as this process culminates, homologs are coaligned ∼400 nm from each other (reviewed in Zickler and Kleckner, 2015). The coalignments consist of linkages between homologous axes which can be represented by “bridges,” each corresponding to a site of DSB-mediated inter-homolog association. Each bridge represents a nascent D-loop in which the “leading” DSB end interacts with its homologous chromosome, and therefore provides informational bias for homolog recognition, whereas the “lagging” DSB end associates with its sister chromatid. A “tentacle” hypothesis has been proposed where one end of the DSB would be released from its chromatin axis and conduct a search of the homologous chromosome (Kim et al., 2010; Panizza et al., 2011). Once the DSB has identified its partner sequence, the strands become associated and a bridge is created (Kim et al., 2010; Storlazzi et al., 2010).

TABLE 1.

Proteins involved in homolog pairing.

| Protein name | Characteristic | Functions | References |

| SUN1 | An inner nuclear membrane protein associated with telomeres | Required for telomere-NE attachment, homologous pairing, and synapsis in spermatocytes and oocytes | Ding et al., 2007 |

| KASH5 | A dynein-dynactin binding protein locating at the outer nuclear membrane; exclusively localizes to telomeres and associates with SUN1 | Essential for homologous pairing and DSB repair in spermatocytes; similar functions are assumed in oogenesis | Morimoto et al., 2012; Horn et al., 2013 |

| TREB1 | A telomere repeat-binding bouquet formation protein, meiosis-specific | Required for telomere-NE attachment and synapsis in male and female mice; homologous pairing and chromosome movement are defective in TREB1 null spermatocytes | Shibuya et al., 2014 |

| TREB2 | A telomere repeat-binding bouquet formation protein, meiosis-specific | Regulate homologous synapsis in spermatocytes and oocytes | Shibuya et al., 2015 |

| MAJIN | Inner nuclear membrane-anchored junction protein | Essential for efficient synapsis in both male and female mice | Shibuya et al., 2015 |

| Speedy A | A non-canonical activator of cyclin-dependent kinases; localizes to telomeres; telomere-localization domain contains distal N-terminus and Cdk2-binding Ringo domain | Mediates telomere-NE attachment, homologous pairing and synapsis in male and female mice | Tu et al., 2017 |

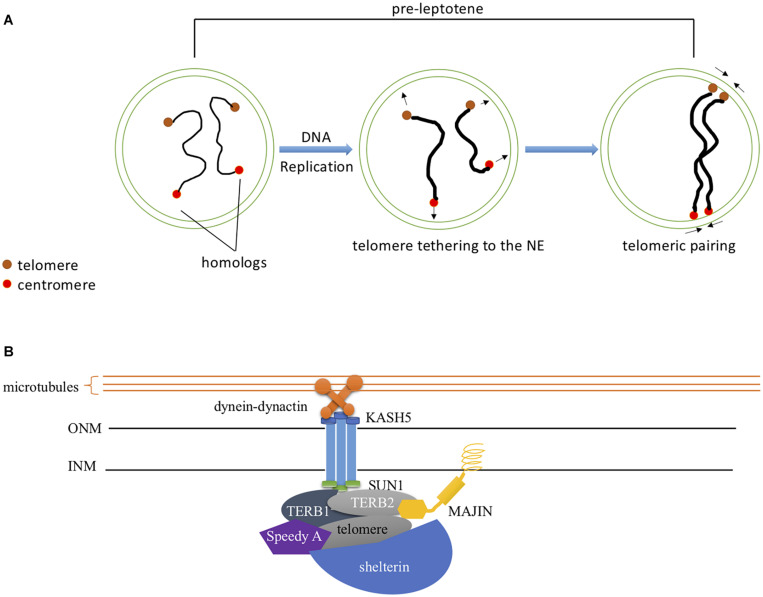

DSB-Independent Pairing

It was widely thought that DSBs were needed for pairing of homologous chromosomes but studies from several organisms suggest that some pairing can occur before DSBs are formed (reviewed in Klutstein and Cooper, 2014). In mouse spermatocytes, a significant proportion of pairing was established before SPO11 induced DSBs (Boateng et al., 2013). In either Mei1 mutant male mice where DSBs are absent but SPO11 expression is normal or Spo11 mutants with defective catalytic activity, pre-leptotene pairing levels were similar to wild type. Thus, pairing also involves a DSB independent mechanism, and SPO11 catalytic activity is dispensable for this process. This involves interactions of the meiotic chromosome telomeres with the nuclear envelope (Figure 3A). The telomeres are tethered to the nuclear envelope by a protein complex called LINC (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton) consisting of SUN1, SUN2, KASH5, and a cohesin subunit (Figure 3B; Ding et al., 2007; Schmitt et al., 2007; Adelfalk et al., 2009). KASH5 recruits dynein to the telomere attachment sites at the outer nuclear membrane and therefore mediates chromosome movements (Horn et al., 2013). The TERB1/2-MAJIN complex connects the telomeres to the LINC complex (Shibuya et al., 2015). The telomeres are capped with the Shelterin complex that protects them from damage (Palm and de Lange, 2008; Shibuya et al., 2015). TERB1/2-MAJIN binds to Shelterin thereby connecting the telomere to the nuclear envelope. An additional protein, Speedy A, has been identified as a protein required for telomere-nuclear envelope attachment in both male and female mice during meiosis (Tu et al., 2017). Mice lacking any of these meiosis-specific structural molecules are sterile (Ding et al., 2007; Morimoto et al., 2012; Horn et al., 2013; Shibuya et al., 2014, 2015; Tu et al., 2017). In mice, both telomere-nuclear envelope attachment and chromosome movements gather correct homologs together and prevent non-homologs from pairing (Koszul and Kleckner, 2009; Storlazzi et al., 2010; Tu et al., 2017). Recently, detailed interactions of pairing have been examined in mouse oocytes including how chromosomes with acrocentric telomeres interact with the nuclear envelope (Kazemi and Taketo, 2021).

FIGURE 3.

DSB-Independent Homolog Pairing (A) DSB-independent pairing at pre-leptotene. Telomeric homolog pairing occurs at pre-leptotene independent of DSB formation. SPO11, not through its catalytic activity, is required for this process. Interstitial pairing is promoted by telomeric pairing and its frequency decreases upon leptotene entry. (B) Meiotic specific protein regulation of telomere-NE attachment. Speedy A localizes to the telomere and regulates its association to the NE. TERB1/2-MAJIN attaches the telomere-shelterin complex to the nuclear envelope by anchoring MAJIN within the INM. The downstream accumulation of the SUN1-KASH5 complex to the telomere attachment site facilitates chromosome movement by linking it to the dynein-dynactin motors through KASH5.

Meiosis-specific cohesion proteins also regulate homologous pairing. Hopkins and colleagues identified Stromal Antigen Protein 3 (STAG3) which localizes to chromocenters (heterochromatin rich pericentrometric clusters) at the pre-leptotene stage (Hopkins et al., 2014). In Stag3 mutant oocytes, the levels of chromosome associations within chromocenters are significantly reduced at both leptotene-like and zygotene-like stages. Homologous pairing depends on chromocenter clustering which is mediated by STAG3; therefore, STAG3 indirectly regulates inter-homolog associations in mouse oocytes.

Synaptonemal Complex Formation and Function

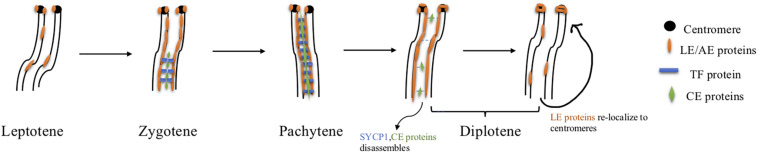

Synaptonemal Complex Assembly

The synaptonemal complex (SC) is a proteinaceous structure that forms between homologous chromosomes and “zippers” them together in eukaryotes. In mice, SC assembly is initiated through DSB formation, which promotes homology search and synapsis (Kauppi et al., 2013). The SC is a tripartite structure composed of lateral elements (LE) on each chromosome attached to the central element (CE) by transverse filaments (TF) (see Figure 4 and Table 2). Prior to synapsis the LEs are referred to as axial elements (AE) that assemble along the chromosomes (for reviews see Fraune et al., 2012; Cahoon and Hawley, 2016). SC formation begins during the leptotene stage when SYCP2 and SYCP3 load onto the chromosome to form AEs (Yang et al., 2006). Recently, in addition to these two AE-localized proteins, five other SC proteins were identified, the TF localized protein, SYCP1 (de Vries et al., 2005) and CE proteins, SYCE1, SYCE2, SYCE3, and TEX12 (Costa et al., 2005; Hamer et al., 2006; Schramm et al., 2011). Mutations in any of these SC proteins cause a failure of synapsis in mouse spermatocytes, prophase one arrest and infertility. The situation in females is more complicated. Like the male, mutations in genes encoding CE proteins or the TF protein, SYCP1 lead to synapsis defects, meiotic arrest and infertility (de Vries et al., 2005; Bolcun-Filas et al., 2007, 2009; Hamer et al., 2008; Schramm et al., 2011). However, Sycp2 or Sycp3 mutant females are subfertile with smaller litter sizes. Oocytes can be fertilized and begin embryonic development but some embryos are aneuploid and do not survive (Yuan et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2006). A more recent study has identified an additional CE protein SIX6OS1, which co-localizes with SYCE1 and SYCE3 (Gomez et al., 2016). In SIX6OS1 deficient oocytes, synapsis failed and all meiocytes were arrested in a pachytene-like stage similar to the other CE mutants.

FIGURE 4.

SC assembly and disassembly in mice. Axial element proteins (orange) start to load onto chromosomes at the leptotene stage. Transverse filament protein SYCP1 (blue) as well as central element proteins (green) begin to assemble at the zygotene stage. By the pachytene stage, homologous chromosomes are fully synapsed and the axial element becomes the lateral element completing the assembly of the SC. Disassembly of the SC depends on PLK1, INCENP(AURKB), and CDK1-Cyclin B1. Phosphorylated PLK1 targets central element protein TEX12, and transverse filament protein SYCP1 to promote central region disassembly. The other central element proteins are then removed from the SC. Simultaneously, both INCENP and AURKB redistribute to centromeres and facilitate lateral element protein relocation to centromere regions. CDK1 is activated by HSPA2, and active CDK1 interacts with Cyclin B1 which also targets lateral element proteins and initiates their redistribution to centromeres.

TABLE 2.

Synaptonemal protein complex components.

| Name | Time | Region | Characteristic | References |

| SYCP1 (synaptonemal complex 1) | Zygotene-diplotene | Transverse filament | N-terminus locates within CE and C-terminus locates within AE; recruits other CE proteins to accomplish SC assembly | Costa et al., 2005; Hamer et al., 2006; Schramm et al., 2011; Gao and Colaiácovo, 2018 |

| SYCP2 (synaptonemal complex 2) | Leptotene-diplotene | Axial element | Interacts with C-terminus directly interacts with SYCP1; a “linker” between AE and TF | Winkel et al., 2009 |

| SYCP3 (synaptonemal complex 3) | Leptotene-diplotene | Axial element | Major structural component of AE | Yuan et al., 2000 |

| SYCE1 (synaptonemal complex central element 1) | Zygotene-diplotene | Central element | Recruited by SYCP1 to the CE region; interacts more directly with SYCP1 | Costa et al., 2005; Hamer et al., 2006 |

| SYCE2 (synaptonemal complex central element 2) | Zygotene-diplotene | Central element | Localization on the CE region depends on SYCP1 | Costa et al., 2005 |

| SYCE3 (synaptonemal complex central element 3) | Zygotene-diplotene | Central element | Downstream of SYCP1 but upstream of SYCE1 and -2 and enables their loading | Schramm et al., 2011 |

| TEX12 (testis expressed sequence 12) | Zygotene-diplotene | Central element | Depends on SYCP1 to localize on the CE; co-localize with SYCE2 | Hamer et al., 2006 |

| SIX60S1 | Zygotene-diplotene | Central element | Co-localizes with SYCE1 and SYCE3 | Gomez et al., 2016 |

SC Extension and Maintenance

Once the SC starts to assemble, it polymerizes down the length of chromosomes to fully synapse the homologs. Cells must maintain full synapsis until the completion of recombination to ensure that homologs are properly aligned and DSB repair errors are reduced (Cahoon and Hawley, 2016). In yeast, the transverse filament protein, Zip1 is important for both the extension and maintenance of the SC (Voelkel-Meiman et al., 2012, 2013; Leung et al., 2015). However, no Zip1 homolog has been identified in mammals. Recently, a protein called synaptonemal complex reinforcing element (SCRE) was found to be important for stabilizing the SC (Liu et al., 2019). In Scre deficient oocytes, the SC formed but synapsis could not be maintained and oocytes were lost, resulting in infertility. Therefore, SCRE maintains the integrity and stability of the SC which is essential for fertility.

SC Disassembly

The SC disassembles during diplotene after crossovers have formed. In male mice, disassembly relies on Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) and Aurora B together with Inner Centromere Protein (INCENP) targeting CEs and LEs, respectively (Parra et al., 2003; Jordan et al., 2012). PLK1 phosphorylates SYCP1 and TEX12 causing subsequent central region collapse during diplotene. Following disassembly of the central region, INCENP re-localizes to centromeric heterochromatin, where Aurora B begins to localize; and results in SYCP2 and SYCP3 disassembling from LEs, both of which subsequently localize to the centromeric heterochromatin (Parra et al., 2003; Sun and Handel, 2008). In addition to PLK1 and Aurora B, CDK1- Cyclin B1 is also required for SC disassembly, as Cdk1 deficient germ cells are arrested at the mid to late pachytene stage (Cahoon and Hawley, 2016). CDK1 is activated by interacting with the chaperone protein HSPA2, and active CDK1 further interacts with Cyclin B1 to promote LE disassembly (Zhu et al., 1997). However, the mechanism of how CDK1-Cyclin B assists in SC disassembly is not well understood. In addition, SC disassembly has not been well studied in mammalian females.

Elimination of Oocytes With Defective DNA Repair or Synapsis

Oocytes With Unrepaired Double Strand Breaks

During meiotic prophase one, DNA is intentionally “damaged” so that recombination can occur. Mechanisms are in place to repair this damage but if the DNA is not repaired a DNA damage response is triggered leading to the elimination of defective oocytes (for review see Gebel et al., 2020). The ATM kinase is upregulated in damaged oocytes leading to activation of CHK2 (Hirao et al., 2002). CHK2 in turn activates an oocyte-specific isoform of the p53 homolog, p63, called TAp63α (Bolcun-Filas et al., 2014; Tuppi et al., 2018). TAp63α is present in oocytes but remains inactive unless damage is detected (Kim and Suh, 2014). Recent work has shown that TAp63α upregulates proapoptotic BCL2 family members PUMA, NOXA, and BAX leading to programmed cell death of the damaged oocytes (ElInati et al., 2020). ATR, at least in spermatocytes, binds to the short stretches of single stranded DNA that appear during DSB processing (Pacheco et al., 2018; Widger et al., 2018). In females, ATR has been implicated in detecting oocytes with DSBs and activating TAp63α (Kim et al., 2019). Besides CHK2, another checkpoint kinase, CHK1 has also been found to mediate removal of damaged oocytes (Martinez-Marchal et al., 2020; Rinaldi et al., 2020).

Oocytes With Unsynapsed Homologous Chromosomes

Mechanisms are also in place to check for and eliminate oocytes with unsynapsed homologous chromosomes (Di Giacomo et al., 2005; Cloutier et al., 2015). Oocytes lacking SPO11 cannot induce DSB formation and mice are infertile due to defective synapsis. However, the SPO11 mutants still accumulate DSBs that may be caused by activation of the LINE1 transposon (Carofiglio et al., 2013; Malki et al., 2014). The current model is that SPO11 makes DSBs and they are required for synapsis to occur. The DSBs get repaired using the homologous chromosome. HORMADs bind to unsynapsed chromosomes preventing repair using the sister chromatid and thereby promoting interaction instead with the homologous chromosome (Wojtasz et al., 2009). Interestingly, RNF212, the SUMO ligase involved in crossover control also plays a role in selecting oocytes for elimination (Qiao et al., 2018). Finally, the elimination of oocytes with unsynapsed chromosomes also depends on CHK2 and the DNA damage response pathway (Rinaldi et al., 2017). However, unlike oocytes with unrepaired DSBs, elimination of Spo 11 mutant oocytes which contain unsynapsed chromosomes does not require BCL2 family members suggesting separate genetic mechanisms of oocyte death (ElInati et al., 2020).

Signaling Pathways in Meiotic Prophase One

In mammalian females, oocytes are arrested in meiotic prophase one until puberty, lasting for months in mice and years in humans. Understanding the signaling events that regulate meiotic progression through prophase one is imperative to shed light on the formation of the ovarian reserve. Retinoic acid (RA) signaling initiates meiosis in mouse ovaries (Bowles et al., 2006; Koubova et al., 2006). The basis helix-loop-helix transcription factor STRA8 is activated by RA signaling (Anderson et al., 2008). This activation requires the RNA binding protein DAZL (Lin et al., 2008). RNA-seq analysis of wild-type, Kit mutant (which are germ cell deficient), Dazl mutant and Stra8 mutant mouse fetal ovaries resulted in the identification of over 100 genes expressed during meiotic prophase one in developing female mouse ovaries (Soh et al., 2015). Almost all of these genes require DAZL for induction but only some are dependent on STRA8. Interestingly, STRA8 independent and partly independent genes encode products important for chromosome structure during meiosis such as SC proteins that would be required early in meiosis.

Steroid hormone signaling plays a role in regulating meiotic progression. Progesterone treatment of fetal mouse ovaries in organ culture resulted in a delay of progression through prophase one (Dutta et al., 2016) and this effect was mediated through the progesterone membrane receptor, PGRMC1 (Guo et al., 2016). Guo and colleagues also found that progesterone caused downregulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) synthesis. An earlier study showed that inhibition of cAMP resulted in meiotic prophase one delay as well as reduced primordial follicle formation (Wang et al., 2015). In addition, they found that blocking cAMP reduced the removal and degradation of SYCP1 protein suggesting that cAMP was important for regulation of SC disassembly. Another study found that the combination of estradiol and progesterone but not progesterone alone affected prophase one progression (Burks et al., 2019). Collectively, steroid hormones have been implicated in regulating meiotic prophase one progression, and further experiments are needed to fully understand this regulation.

Phthalates are synthetic chemical esters of phthalic acid and can act as endocrine disruptors impairing reproductive function with effects on reproductive organs including the ovary (Hannon and Flaws, 2015). Neonatal exposure to the phthalate, di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) reduces primordial follicle formation and increases autophagy (Mu et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018). The effect on primordial follicle formation was mediated through estrogen receptors which are known to be expressed in mouse ovaries at this time (Chen et al., 2009). Fetal DEHP exposure delays progression through meiotic prophase one and impairs DSB repair (Liu et al., 2017) supporting the idea that estrogens play a role in meiotic progression and can be negatively impacted by endocrine disruptors. In addition, another phthalate, dibutyl phthalate (DBP) had effects on meiotic progression and DNA repair similar to DEHP (Tu et al., 2019). Expression of DNA repair proteins including ATR was reduced and oxidative stress was induced leading to an increase in oocyte apoptosis. Another endocrine disruptor, bisphenol A (BPA) also caused meiotic prophase one defects including higher than normal recombination and synapsis failure and again these effects are thought to be through estrogen receptors (Susiarjo et al., 2007).

Concluding Remarks

Meiotic prophase one is imperative to ensure accurate chromosome segregation as well as reproductive success. Much progress has been made in understanding the crucial checkpoints in mammalian prophase one. Interestingly, many studies have used mouse spermatocytes for elucidating meiotic events, such as DSB level regulation and homologous pairing. This is likely due to the fact that germ cells in all stages of meiotic prophase one can be obtained from adult male mice. In contrast, in females, oocytes need to be obtained during fetal stages which can be more difficult to obtain. Even though these critical events are controlled by similar genetic pathways, there are differences in checkpoint control in males and females (Morelli and Cohen, 2005). In most cases, mammalian oocytes have higher fault-tolerant rates. Therefore, while studies conducted on mouse spermatocytes contribute to our understanding of mammalian meiotic progression, there are also differences in mouse oocytes. Understanding the regulation of and progression through meiotic prophase one in oocytes and comparisons to spermatocytes will provide a more comprehensive picture of meiosis and aid in developing better female infertility treatments.

Author Contributions

XW and MP contributed to writing and editing of this review. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joshua Burton, Suzanne Getman, and Jessica O’Connell for critical proofreading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R15 HD 099859).

References

- Adelfalk C., Janschek J., Revenkova E., Blei C., Liebe B., Gob E., et al. (2009). Cohesin SMC1beta protects telomeres in meiocytes. J. Cell Biol. 187 185–199. 10.1083/jcb.200808016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. L., Baltus A. E., Roepers-Gajadien H. L., Hassold T. J., De Rooij D. G., Van Pelt A. M., et al. (2008). Stra8 and its inducer, retinoic acid, regulate meiotic initiation in both spermatogenesis and oogenesis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 14976–14980. 10.1073/pnas.0807297105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudat F., Buard J., Grey C., Fledel-Alon A., Ober C., Przeworski M., et al. (2010). PRDM9 is a major determinant of meiotic recombination hotspots in humans and mice. Science 327 836–840. 10.1126/science.1183439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudat F., Imai Y., De Massy B. (2013). Meiotic recombination in mammals: localization and regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14 794–806. 10.1038/nrg3573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudat F., Manova K., Yuen J. P., Jasin M., Keeney S. (2000). Chromosome synapsis defects and sexually dimorphic meiotic progression in mice lacking Spo11. Mol. Cell 6 989–998. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00098-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boateng K. A., Bellani M. A., Gregoretti I. V., Pratto F., Camerini-Otero R. D. (2013). Homologous pairing preceding SPO11-mediated double-strand breaks in mice. Dev. Cell 24 196–205. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolcun-Filas E., Costa Y., Speed R., Taggart M., Benavente R., De Rooij D. G., et al. (2007). SYCE2 is required for synaptonemal complex assembly, double strand break repair, and homologous recombination. J. Cell Biol. 176 741–747. 10.1083/jcb.200610027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolcun-Filas E., Hall E., Speed R., Taggart M., Grey C., De Massy B., et al. (2009). Mutation of the mouse Syce1 gene disrupts synapsis and suggests a link between synaptonemal complex structural components and DNA repair. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000393. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolcun-Filas E., Rinaldi V. D., White M. E., Schimenti J. C. (2014). Reversal of female infertility by Chk2 ablation reveals the oocyte DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Science 343 533–536. 10.1126/science.1247671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolcun-Filas E., Schimenti J. C. (2012). Genetics of meiosis and recombination in mice. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 298 179–227. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394309-5.00005-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borum K. (1961). Oogenesis in the mouse. A study of the meiotic prophase. Exp. Cell Res. 24 495–507. 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90449-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J., Knight D., Smith C., Wilhelm D., Richman J., Mamiya S., et al. (2006). Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science 312 596–600. 10.1126/science.1125691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brick K., Smagulova F., Khil P., Camerini-Otero R. D., Petukhova G. V. (2012). Genetic recombination is directed away from functional genomic elements in mice. Nature 485 642–645. 10.1038/nature11089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunschwig H., Levi L., Ben-David E., Williams R. W., Yakir B., Shifman S. (2012). Fine-scale maps of recombination rates and hotspots in the mouse genome. Genetics 191 757–764. 10.1534/genetics.112.141036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullejos M., Koopman P. (2004). Germ cells enter meiosis in a rostro-caudal wave during development of the mouse ovary. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 68 422–428. 10.1002/mrd.20105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burks D. M., Mccoy M. R., Dutta S., Mark-Kappeler C. J., Hoyer P. B., Pepling M. E. (2019). Molecular analysis of the effects of steroid hormones on mouse meiotic prophase I progression. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 17:105. 10.1186/s12958-019-0548-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon C. K., Hawley R. S. (2016). Regulating the construction and demolition of the synaptonemal complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23 369–377. 10.1038/nsmb.3208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carofiglio F., Inagaki A., De Vries S., Wassenaar E., Schoenmakers S., Vermeulen C., et al. (2013). SPO11-independent DNA repair foci and their role in meiotic silencing. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003538. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Breen K., Pepling M. E. (2009). Estrogen can signal through multiple pathways to regulate oocyte cyst breakdown and primordial follicle assembly in the neonatal mouse ovary. J. Endocrinol. 202 407–417. 10.1677/JOE-09-0109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier J. M., Mahadevaiah S. K., Elinati E., Nussenzweig A., Toth A., Turner J. M. (2015). Histone H2AFX links meiotic chromosome asynapsis to prophase I oocyte loss in mammals. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005462. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. E., Pollack S. E., Pollard J. W. (2006). Genetic analysis of chromosome pairing, recombination, and cell cycle control during first meiotic prophase in mammals. Endocr. Rev. 27 398–426. 10.1210/er.2005-0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper T. J., Wardell K., Garcia V., Neale M. J. (2014). Homeostatic regulation of meiotic DSB formation by ATM/ATR. Exp. Cell Res. 329 124–131. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Y., Speed R., Ollinger R., Alsheimer M., Semple C. A., Gautier P., et al. (2005). Two novel proteins recruited by synaptonemal complex protein 1 (SYCP1) are at the centre of meiosis. J. Cell Sci. 118 2755–2762. 10.1242/jcs.02402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel K., Lange J., Hached K., Fu J., Anastassiadis K., Roig I., et al. (2011). Meiotic homologue alignment and its quality surveillance are controlled by mouse HORMAD1. Nat. Cell Biol. 13 599–610. 10.1038/ncb2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries F. A., De Boer E., Van Den Bosch M., Baarends W. M., Ooms M., Yuan L., et al. (2005). Mouse Sycp1 functions in synaptonemal complex assembly, meiotic recombination, and XY body formation. Genes Dev. 19 1376–1389. 10.1101/gad.329705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giacomo M., Barchi M., Baudat F., Edelmann W., Keeney S., Jasin M. (2005). Distinct DNA-damage-dependent and -independent responses drive the loss of oocytes in recombination-defective mouse mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 737–742. 10.1073/pnas.0406212102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X., Xu R., Yu J., Xu T., Zhuang Y., Han M. (2007). SUN1 is required for telomere attachment to nuclear envelope and gametogenesis in mice. Dev. Cell 12 863–872. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S., Burks D. M., Pepling M. E. (2016). Arrest at the diplotene stage of meiotic prophase I is delayed by progesterone but is not required for primordial follicle formation in mice. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 14:82. 10.1186/s12958-016-0218-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElInati E., Zielinska A. P., Mccarthy A., Kubikova N., Maciulyte V., Mahadevaiah S., et al. (2020). The BCL-2 pathway preserves mammalian genome integrity by eliminating recombination-defective oocytes. Nat. Commun. 11:2598. 10.1038/s41467-020-16441-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraune J., Schramm S., Alsheimer M., Benavente R. (2012). The mammalian synaptonemal complex: protein components, assembly and role in meiotic recombination. Exp. Cell Res. 318 1340–1346. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Colaiácovo M. P. (2018). Zipping and unzipping: protein modifications regulating synaptonemal complex dynamics. Trends Genet. 34 232–245. 10.1016/j.tig.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebel J., Tuppi M., Sanger N., Schumacher B., Dotsch V. (2020). DNA damaged induced cell death in oocytes. Molecules 25:5714. 10.3390/molecules25235714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez H. L., Felipe-Medina N., Sanchez-Martin M., Davies O. R., Ramos I., Garcia-Tunon I., et al. (2016). C14ORF39/SIX6OS1 is a constituent of the synaptonemal complex and is essential for mouse fertility. Nat. Commun. 7:13298. 10.1038/ncomms13298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S., Cohen P. E. (2016). Control of meiotic crossovers: from double-strand break formation to designation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 50 175–210. 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld C. R., Pepling M. E., Babus J. K., Furth P. A., Flaws J. A. (2007). BAX regulates follicular endowment in mice. Reproduction 133 865–876. 10.1530/REP-06-0270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiraldelli M. F., Eyster C., Wilkerson J. L., Dresser M. E., Pezza R. J. (2013). Mouse HFM1/Mer3 is required for crossover formation and complete synapsis of homologous chromosomes during meiosis. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003383. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M., Zhang C., Wang Y., Feng L., Wang Z., Niu W., et al. (2016). Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 mediates progesterone-induced suppression of oocyte meiotic prophase I and primordial folliculogenesis. Sci. Rep. 6:36869. 10.1038/srep36869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer G., Gell K., Kouznetsova A., Novak I., Benavente R., Hoog C. (2006). Characterization of a novel meiosis-specific protein within the central element of the synaptonemal complex. J. Cell Sci. 119 4025–4032. 10.1242/jcs.03182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer G., Wang H., Bolcun-Filas E., Cooke H. J., Benavente R., Hoog C. (2008). Progression of meiotic recombination requires structural maturation of the central element of the synaptonemal complex. J. Cell Sci. 121 2445–2451. 10.1242/jcs.033233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon P. R., Flaws J. A. (2015). The effects of phthalates on the ovary. Front. Endocrinol. 6:8. 10.3389/fendo.2015.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne G. M., Lyrakou S., Hamoda H., Oloto E., Ghafari F. (2009). Oogenesis and cell death in human prenatal ovaries: what are the criteria for oocyte selection? Mol. Hum. Reprod. 15 805–819. 10.1093/molehr/gap055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T., Hunt P. (2001). To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2 280–291. 10.1038/35066065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert M., Kalleas D., Cooney D., Lamb M., Lister L. (2015). Meiosis and maternal aging: insights from aneuploid oocytes and trisomy births. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7:a017970. 10.1101/cshperspect.a017970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao A., Cheung A., Duncan G., Girard P. M., Elia A. J., Wakeham A., et al. (2002). Chk2 is a tumor suppressor that regulates apoptosis in both an ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-dependent and an ATM-independent manner. Mol. Cell Biol. 22 6521–6532. 10.1128/mcb.22.18.6521-6532.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway J. K., Sun X., Yokoo R., Villeneuve A. M., Cohen P. E. (2014). Mammalian CNTD1 is critical for meiotic crossover maturation and deselection of excess precrossover sites. J. Cell Biol. 205 633–641. 10.1083/jcb.201401122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins J., Hwang G., Jacob J., Sapp N., Bedigian R., Oka K., et al. (2014). Meiosis-specific cohesin component, Stag3 is essential for maintaining centromere chromatid cohesion, and required for DNA repair and synapsis between homologous chromosomes. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004413. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn H. F., Kim D. I., Wright G. D., Wong E. S., Stewart C. L., Burke B., et al. (2013). A mammalian KASH domain protein coupling meiotic chromosomes to the cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 202 1023–1039. 10.1083/jcb.201304004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan P. W., Karppinen J., Handel M. A. (2012). Polo-like kinase is required for synaptonemal complex disassembly and phosphorylation in mouse spermatocytes. J. Cell Sci. 125 5061–5072. 10.1242/jcs.105015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppi L., Barchi M., Lange J., Baudat F., Jasin M., Keeney S. (2013). Numerical constraints and feedback control of double-strand breaks in mouse meiosis. Genes Dev. 27 873–886. 10.1101/gad.213652.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi P., Taketo T. (2021). Two telomeric ends of acrocentric chromosome play distinct roles in homologous chromosome synapsis in the fetal mouse oocyte. Chromosoma 130 41–52. 10.1007/s00412-021-00752-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney S. (2008). Spo11 and the formation of DNA double-strand breaks in meiosis. Genome Dyn. Stab. 2 81–123. 10.1007/7050_2007_026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. A., Suh E. K. (2014). Defying DNA double-strand break-induced death during prophase I meiosis by temporal TAp63alpha phosphorylation regulation in developing mouse oocytes. Mol. Cell Biol. 34 1460–1473. 10.1128/MCB.01223-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. P., Weiner B. M., Zhang L., Jordan A., Dekker J., Kleckner N. (2010). Sister cohesion and structural axis components mediate homolog bias of meiotic recombination. Cell 143 924–937. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Y., Nair D. M., Romero M., Serna V. A., Koleske A. J., Woodruff T. K., et al. (2019). Transient inhibition of p53 homologs protects ovarian function from two distinct apoptotic pathways triggered by anticancer therapies. Cell Death Differ. 26 502–515. 10.1038/s41418-018-0151-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klutstein M., Cooper J. P. (2014). The chromosomal courtship dance-homolog pairing in early meiosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 26 123–131. 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneitz B., Cohen P. E., Avdievich E., Zhu L., Kane M. F., Hou H., Jr., et al. (2000). MutS homolog 4 localization to meiotic chromosomes is required for chromosome pairing during meiosis in male and female mice. Genes Dev. 14 1085–1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszul R., Kleckner N. (2009). Dynamic chromosome movements during meiosis: a way to eliminate unwanted connections? Trends Cell Biol. 19 716–724. 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koubova J., Menke D. B., Zhou Q., Capel B., Griswold M. D., Page D. C. (2006). Retinoic acid regulates sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 2474–2479. 10.1073/pnas.0510813103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Bourbon H. M., De Massy B. (2010). Functional conservation of Mei4 for meiotic DNA double-strand break formation from yeasts to mice. Genes Dev. 24 1266–1280. 10.1101/gad.571710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Ghyselinck N., Ishiguro K., Watanabe Y., Kouznetsova A., Hoog C., et al. (2015). MEI4 - a central player in the regulation of meiotic DNA double-strand break formation in the mouse. J. Cell Sci. 128 1800–1811. 10.1242/jcs.165464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Oliver C., Brun C., Juarez-Martinez A. B., Tarabay Y., Kadlec J., et al. (2018). Mouse REC114 is essential for meiotic DNA double-strand break formation and forms a complex with MEI4. Life Sci. Alliance 1:e201800259. 10.26508/lsa.201800259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange J., Pan J., Cole F., Thelen M. P., Jasin M., Keeney S. (2011). ATM controls meiotic double-strand-break formation. Nature 479 237–240. 10.1038/nature10508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L., Spradling A. C. (2013). Mouse primordial germ cells produce cysts that partially fragment prior to meiosis. Development 140 2075–2081. 10.1242/dev.093864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L., Spradling A. C. (2016). Mouse oocytes differentiate through organelle enrichment from sister cyst germ cells. Science 352 95–99. 10.1126/science.aad2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W. K., Humphryes N., Afshar N., Argunhan B., Terentyev Y., Tsubouchi T., et al. (2015). The synaptonemal complex is assembled by a polySUMOylation-driven feedback mechanism in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 211 785–793. 10.1083/jcb.201506103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby B. J., Reinholdt L. G., Schimenti J. C. (2003). Positional cloning and characterization of Mei1, a vertebrate-specific gene required for normal meiotic chromosome synapsis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 15706–15711. 10.1073/pnas.2432067100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Gill M. E., Koubova J., Page D. C. (2008). Germ cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors govern meiotic initiation in mouse embryos. Science 322 1685–1687. 10.1126/science.1166340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkin S. M., Moens P. B., Wang V., Lenzi M., Shanmugarajah D., Gilgeous A., et al. (2002). Meiotic arrest and aneuploidy in MLH3-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 31 385–390. 10.1038/ng931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Huang T., Li M., Li M., Zhang C., Jiang J., et al. (2019). SCRE serves as a unique synaptonemal complex fastener and is essential for progression of meiosis prophase I in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 5670–5683. 10.1093/nar/gkz226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. C., Lai F. N., Li L., Sun X. F., Cheng S. F., Ge W., et al. (2017). Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate exposure impairs meiotic progression and DNA damage repair in fetal mouse oocytes in vitro. Cell Death Dis. 8:e2966. 10.1038/cddis.2017.350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malki S., Van Der Heijden G. W., O’donnell K. A., Martin S. L., Bortvin A. (2014). A role for retrotransposon LINE-1 in fetal oocyte attrition in mice. Dev. Cell 29 521–533. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Marchal A., Huang Y., Guillot-Ferriols M. T., Ferrer-Roda M., Guixe A., Garcia-Caldes M., et al. (2020). The DNA damage response is required for oocyte cyst breakdown and follicle formation in mice. PLoS Genet. 16:e1009067. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcgee E. A., Hsueh A. J. (2000). Initial and cyclic recruitment of ovarian follicles. Endocr. Rev. 21 200–214. 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke D. B., Koubova J., Page D. C. (2003). Sexual differentiation of germ cells in XX mouse gonads occurs in an anterior-to-posterior wave. Dev. Biol. 262 303–312. 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00391-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modzelewski A. J., Hilz S., Crate E. A., Schweidenback C. T., Fogarty E. A., Grenier J. K., et al. (2015). Dgcr8 and Dicer are essential for sex chromosome integrity during meiosis in males. J. Cell Sci. 128 2314–2327. 10.1242/jcs.167148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux K. A., Stallock J., Schaible K., Wylie C. (2001). Time-lapse analysis of living mouse germ cell migration. Dev. Biol. 240 488–498. 10.1006/dbio.2001.0436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli M. A., Cohen P. E. (2005). Not all germ cells are created equal: aspects of sexual dimorphism in mammalian meiosis. Reproduction 130 761–781. 10.1530/rep.1.00865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto A., Shibuya H., Zhu X., Kim J., Ishiguro K., Han M., et al. (2012). A conserved KASH domain protein associates with telomeres, SUN1, and dynactin during mammalian meiosis. J. Cell Biol. 198 165–172. 10.1083/jcb.201204085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X., Liao X., Chen X., Li Y., Wang M., Shen C., et al. (2015). DEHP exposure impairs mouse oocyte cyst breakdown and primordial follicle assembly through estrogen receptor-dependent and independent mechanisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 298 232–240. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale M. J., Pan J., Keeney S. (2005). Endonucleolytic processing of covalent protein-linked DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 436 1053–1057. 10.1038/nature03872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco S., Maldonado-Linares A., Garcia-Caldes M., Roig I. (2019). ATR function is indispensable to allow proper mammalian follicle development. Chromosoma 128 489–500. 10.1007/s00412-019-00723-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco S., Maldonado-Linares A., Marcet-Ortega M., Rojas C., Martinez-Marchal A., Fuentes-Lazaro J., et al. (2018). ATR is required to complete meiotic recombination in mice. Nat. Commun. 9:2622. 10.1038/s41467-018-04851-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paigen K., Petkov P. (2010). Mammalian recombination hot spots: properties, control and evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11 221–233. 10.1038/nrg2712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm W., de Lange T. (2008). How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42 301–334. 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizza S., Mendoza M. A., Berlinger M., Huang L., Nicolas A., Shirahige K., et al. (2011). Spo11-accessory proteins link double-strand break sites to the chromosome axis in early meiotic recombination. Cell 146 372–383. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra M. T., Viera A., Gomez R., Page J., Carmena M., Earnshaw W. C., et al. (2003). Dynamic relocalization of the chromosomal passenger complex proteins inner centromere protein (INCENP) and aurora-B kinase during male mouse meiosis. J. Cell Sci. 116 961–974. 10.1242/jcs.00330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepling M. E. (2012). Follicular assembly: mechanisms of action. Reproduction 143 139–149. 10.1530/REP-11-0299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepling M. E., De Cuevas M., Spradling A. C. (1999). Germline cysts: a conserved phase of germ cell development? Trends Cell Biol. 9 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepling M. E., Spradling A. C. (1998). Female mouse germ cells form synchronously dividing cysts. Development 125 3323–3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepling M. E., Spradling A. C. (2001). Mouse ovarian germ cell cysts undergo programmed breakdown to form primordial follicles. Dev. Biol. 234 339–351. 10.1006/dbio.2001.0269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petukhova G. V., Pezza R. J., Vanevski F., Ploquin M., Masson J. Y., Camerini-Otero R. D. (2005). The Hop2 and Mnd1 proteins act in concert with Rad51 and Dmc1 in meiotic recombination. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12 449–453. 10.1038/nsmb923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman D. L., Cobb J., Schimenti K. J., Wilson L. A., Cooper D. M., Brignull E., et al. (1998). Meiotic prophase arrest with failure of chromosome synapsis in mice deficient for Dmc1, a germline-specific RecA homolog. Mol. Cell 1 697–705. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80069-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H., Prasada Rao H. B., Yang Y., Fong J. H., Cloutier J. M., Deacon D. C., et al. (2014). Antagonistic roles of ubiquitin ligase HEI10 and SUMO ligase RNF212 regulate meiotic recombination. Nat. Genet. 46 194–199. 10.1038/ng.2858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H., Rao H., Yun Y., Sandhu S., Fong J. H., Sapre M., et al. (2018). Impeding dna break repair enables oocyte quality control. Mol. Cell 72 211.e3–221.e3. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao H. B., Qiao H., Bhatt S. K., Bailey L. R., Tran H. D., Bourne S. L., et al. (2017). A SUMO-ubiquitin relay recruits proteasomes to chromosome axes to regulate meiotic recombination. Science 355 403–407. 10.1126/science.aaf6407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A., Qiao H., Yang Y., Chen J. K., Jackson N., Biswas K., et al. (2013). RNF212 is a dosage-sensitive regulator of crossing-over during mammalian meiosis. Nat. Genet. 45 269–278. 10.1038/ng.2541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi V. D., Bloom J. C., Schimenti J. C. (2020). Oocyte elimination through DNA Damage signaling from CHK1/CHK2 to p53 and p63. Genetics 215 373–378. 10.1534/genetics.120.303182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi V. D., Hsieh K., Munroe R., Bolcun-Filas E., Schimenti J. C. (2017). Pharmacological inhibition of the DNA damage checkpoint prevents radiation-induced oocyte Death. Genetics 206 1823–1828. 10.1534/genetics.117.203455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanienko P. J., Camerini-Otero R. D. (2000). The mouse Spo11 gene is required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Mol. Cell 6 975–987. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00097-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J., Benavente R., Hodzic D., Hoog C., Stewart C. L., Alsheimer M. (2007). Transmembrane protein Sun2 is involved in tethering mammalian meiotic telomeres to the nuclear envelope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 7426–7431. 10.1073/pnas.0609198104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm S., Fraune J., Naumann R., Hernandez-Hernandez A., Hoog C., Cooke H. J., et al. (2011). A novel mouse synaptonemal complex protein is essential for loading of central element proteins, recombination, and fertility. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002088. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya H., Hernandez-Hernandez A., Morimoto A., Negishi L., Hoog C., Watanabe Y. (2015). MAJIN links telomeric DNA to the nuclear membrane by exchanging telomere cap. Cell 163 1252–1266. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya H., Ishiguro K., Watanabe Y. (2014). The TRF1-binding protein TERB1 promotes chromosome movement and telomere rigidity in meiosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 16 145–156. 10.1038/ncb2896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smagulova F., Gregoretti I. V., Brick K., Khil P., Camerini-Otero R. D., Petukhova G. V. (2011). Genome-wide analysis reveals novel molecular features of mouse recombination hotspots. Nature 472 375–378. 10.1038/nature09869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh Y. Q., Junker J. P., Gill M. E., Mueller J. L., Van Oudenaarden A., Page D. C. (2015). A gene regulatory program for meiotic prophase in the fetal ovary. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005531. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanzione M., Baumann M., Papanikos F., Dereli I., Lange J., Ramlal A., et al. (2016). Meiotic DNA break formation requires the unsynapsed chromosome axis-binding protein IHO1 (CCDC36) in mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 18 1208–1220. 10.1038/ncb3417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storlazzi A., Gargano S., Ruprich-Robert G., Falque M., David M., Kleckner N., et al. (2010). Recombination proteins mediate meiotic spatial chromosome organization and pairing. Cell 141 94–106. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F., Handel M. A. (2008). Regulation of the meiotic prophase I to metaphase I transition in mouse spermatocytes. Chromosoma 117 471–485. 10.1007/s00412-008-0167-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susiarjo M., Hassold T. J., Freeman E., Hunt P. A. (2007). Bisphenol A exposure in utero disrupts early oogenesis in the mouse. PLoS Genet. 3:e5. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z., Bayazit M. B., Liu H., Zhang J., Busayavalasa K., Risal S., et al. (2017). Speedy A-Cdk2 binding mediates initial telomere-nuclear envelope attachment during meiotic prophase I independent of Cdk2 activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 592–597. 10.1073/pnas.1618465114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z., Mu X., Chen X., Geng Y., Zhang Y., Li Q., et al. (2019). Dibutyl phthalate exposure disrupts the progression of meiotic prophase I by interfering with homologous recombination in fetal mouse oocytes. Environ. Pollut. 252 388–398. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuppi M., Kehrloesser S., Coutandin D. W., Rossi V., Luh L. M., Strubel A., et al. (2018). Oocyte DNA damage quality control requires consecutive interplay of CHK2 and CK1 to activate p63. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25 261–269. 10.1038/s41594-018-0035-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelkel-Meiman K., Moustafa S. S., Lefrancois P., Villeneuve A. M., Macqueen A. J. (2012). Full-length synaptonemal complex grows continuously during meiotic prophase in budding yeast. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002993. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelkel-Meiman K., Taylor L. F., Mukherjee P., Humphryes N., Tsubouchi H., Macqueen A. J. (2013). SUMO localizes to the central element of synaptonemal complex and is required for the full synapsis of meiotic chromosomes in budding yeast. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003837. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Teng Z., Li G., Mu X., Wang Z., Feng L., et al. (2015). Cyclic AMP in oocytes controls meiotic prophase I and primordial folliculogenesis in the perinatal mouse ovary. Development 142 343–351. 10.1242/dev.112755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widger A., Mahadevaiah S. K., Lange J., Elinati E., Zohren J., Hirota T., et al. (2018). ATR is a multifunctional regulator of male mouse meiosis. Nat. Commun. 9:2621. 10.1038/s41467-018-04850-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins A. S., Holliday R. (2009). The evolution of meiosis from mitosis. Genetics 181 3–12. 10.1534/genetics.108.099762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkel K., Alsheimer M., Ollinger R., Benavente R. (2009). Protein SYCP2 provides a link between transverse filaments and lateral elements of mammalian synaptonemal complexes. Chromosoma 118 259–267. 10.1007/s00412-008-0194-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtasz L., Daniel K., Roig I., Bolcun-Filas E., Xu H., Boonsanay V., et al. (2009). Mouse HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, two conserved meiotic chromosomal proteins, are depleted from synapsed chromosome axes with the help of TRIP13 AAA-ATPase. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000702. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., De La Fuente R., Leu N. A., Baumann C., Mclaughlin K. J., Wang P. J. (2006). Mouse SYCP2 is required for synaptonemal complex assembly and chromosomal synapsis during male meiosis. J. Cell Biol. 173 497–507. 10.1083/jcb.200603063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Liu J. G., Hoja M. R., Wilbertz J., Nordqvist K., Hoog C. (2002). Female germ cell aneuploidy and embryo death in mice lacking the meiosis-specific protein SCP3. Science 296 1115–1118. 10.1126/science.1070594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Liu J. G., Zhao J., Brundell E., Daneholt B., Hoog C. (2000). The murine SCP3 gene is required for synaptonemal complex assembly, chromosome synapsis, and male fertility. Mol. Cell 5 73–83. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80404-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Mu X., Gao R., Geng Y., Liu X., Chen X., et al. (2018). Foetal-neonatal exposure of Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate disrupts ovarian development in mice by inducing autophagy. J. Hazard. Mater. 358 101–112. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.06.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D., Dix D. J., Eddy E. M. (1997). HSP70-2 is required for CDC2 kinase activity in meiosis I of mouse spermatocytes. Development 124 3007–3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickler D., Kleckner N. (2015). Recombination, Pairing, and Synapsis of Homologs during Meiosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7:a016626. 10.1101/cshperspect.a016626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]