Abstract

Popliteus is an integral component of the posterolateral corner of the knee. We review the anatomy and various pathologies affecting the popliteus.

Keywords: Popliteus, Anatomy, Pathology

1. Introduction

The popliteus musculotendinous complex is an important component of the posterolateral corner of the knee. In this retrospective study we will review the anatomy of the popliteus and pathologies of the popliteus muscle and tendon, which include tears, infection, arteriovenous malformation, pigmented villonodular synovitis,.

2. Anatomy

The popliteus muscle is located in the deep posterior compartment of the leg accompanied by three other muscles the flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus and tibialis posterior. It is a flat triangular muscle that acts as a major stabilizer of the posterolateral knee. It is unique, inverted, having insertion with a proximal tendinous origin from the lateral condyle of the femur and a distal muscular insertion onto the posterior aspect of the proximal tibia (Fig. 1). The popliteus tendon is intra-capsular, but extra-synovial and forms a crucial component of the posterolateral corner of the knee (Fig. 2). From its attachment at the posteromedial tibia the popliteus courses superolaterally. The popliteofibular ligament is a relatively consistent ligament, which secures the popliteus myotendinous junction to the posterior aspect of the fibular styloid process (Fig. 4, Fig. 5).1 The tendon traverses underneath the posterolateral joint capsule and arcuate ligament to move from extra-capsular to intra-capsular. The tendon attaches to the lateral meniscus via superior and inferior popliteomeniscal fascicles. There is a degree of anatomical variation to this attachment with cadaveric studies demonstrating that up to 45% of specimens has no attachment to the lateral meniscus.2 The popliteus tendon passes underneath the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) and the biceps femoris tendon and attaches proximally onto the popliteal notch on the lateral condyle of the femur inferior to the origins of lateral head of gastrocnemius and femoral attachment of the fibular collateral ligament.

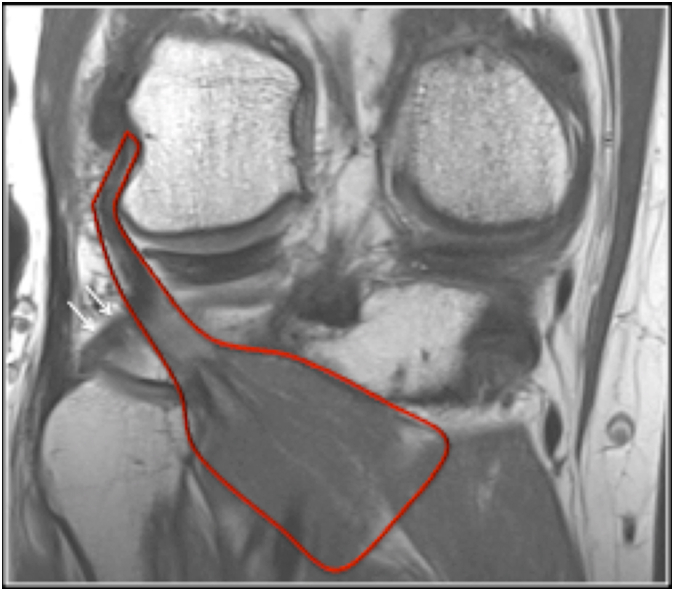

Fig. 1.

Coronal PD MR sequence showing the popliteus muscle and tendon (red outline) and popliteofibular ligament (arrow).

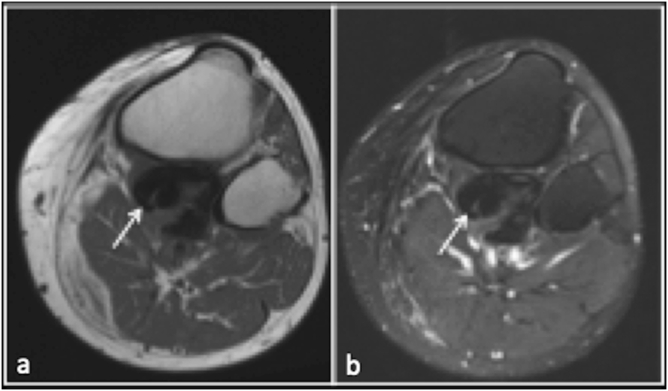

Fig. 2.

Axial (a) and coronal (b) CT arthrogram demonstrating the popliteus tendon (arrow) located in the popliteal groove of the lateral femoral condyle.

Fig. 4.

Axial(a) and coronal (b) STIR MR sequences demonstrating popliteus tendon tear (arrow) in the setting of multiple other injuries including cruciate ligament, lateral collateral ligament and posterolateral.

Fig. 5.

Coronal T1(a) and PDFS(b) MR showing chronic avulsion fracture of popliteus.

The popliteus receives arterial blood supply from the popliteal artery via the medial inferior genicular branch and the muscular branch of the posterior tibial artery.3 Innervation is via the tibial nerve from the anterior rami of L4, L5 and S1. There can be up to 3 parallel tibial nerve branches. The entry point of the nerve into the popliteus muscle is the lateral distal margin inferior to the fibular head.4 The lymphatic drainage is to the popliteal nodes and subsequently to the deep inguinal nodes of the groin5. Very rarely the cyamella, a small sesamoid bone can be found within the tendon or myotendinous junction. When present the cyamella can articulate with the lateral condyle of the tibia.6

3. Popliteus musculotendinous complex injury

Injury to the popliteus musculotendinous complex is relatively common and most often occurs in combination with other injuries particularly to but not limited to the other structures of the posterolateral corner of the knee.7 In addition cruciate, collateral ligament injuries and meniscal tears can be associated with popliteus injury (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5).8,9 Popliteus injuries are detected in 1% of all knee MRI examinations.8

Fig. 3.

Axial(a) and coronal(b) PD demonstrating heterogeneous signal intensity and thickening of the popliteus tendon (arrow) at the femoral notch in keeping with popliteal tendinopathy.

However isolated injury to the popliteus is relatively uncommon (7 9). Injury is usually secondary to trauma.10 Proposed mechanisms of injury for traumatic popliteus injury include secondary to a direct blow to the anteromedial aspect of the proximal tibia with the knee hyperextended however other studies have found no clear mechanism of injury.1

Injury can be further subdivide into those affecting the muscle (Fig. 6), the myotendinous junction and the tendon itself (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). In a study of traumatic injury by Brown et al. 23 of 24 patients had muscle tears and 3 patients had combined muscle and tendon tears or tendon alone.8 Strain injuries affect the myotendinous junction, the weakest point of the musculotendinous unit.11 Tendon injuries can occur at the popliteal hiatus or at the femoral attachment where there can be an associated osteochondral avulsed fragment. The presence of an avulsed osteochondral fragment is favourable for subsequent surgical repair.12

Fig. 6.

Coronal, (a), sagittal (b) and axial (c) PDFS MR showing marked oedema involving the popliteus muscle (arrow) in keeping with grade 2 strain.

4. Popliteal recess pathology

The popliteal recess is an extension of the synovial membrane of the knee joint. This recess extends from the popliteal hiatus along the proximal part of the popliteus tendon. The recess should not be mistaken for a ganglion cyst of the proximal tibiofibular joint. Intra-articular loose bodies, from any aetiology, but most commonly seen in the setting of osteoarthritis can migrate into the recess and present as posterolateral knee pain(Fig. 7, Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Axial T1(a), STIR (b) and coronal STIR (c) demonstrating multiple loose bodies.

Fig. 8.

Axial(a) and coronal (b) PDFS sequences demonstrating low intensity loose bodies along the popliteus (arrow).

5. Myositis ossificans

Myositis ossificans (MO) as the name suggests is a benign inflammatory condition characterized by heterotopic bone formation in skeletal muscle.

It can broadly be divided into three categories including posttraumatic myositis ossificans that accounts for up to 75% of cases, non-traumatic/pseudomalignant myositis ossificans and the hereditary and pathologically diverse myositis ossificans progressive.13

Three overlapping stages of MO are described including early, intermediate and mature which also have differing radiological and clinical features. The early stage occurs in the first four weeks and is characterized by inflammation and soft tissue swelling usually with an absence of ossification and calcification. Radiographs can often appear normal during this phase. In the intermediate phase, 4–8 weeks peripheral calcification becomes apparent radiographically. In the mature stage there is further osseous consolidation resulting in a densely calcified lesion usually parallel to the long axes of adjacent bone.14,15

Differentials for MO include infection particularly in the early stage when muscle swelling and inflammation are the predominant features. Conversely chronic abscess can also have associated peripheral calcification. Other tumours that can have associated calcification/ossification include synovial sarcoma, parosteal and soft tissue osteosarcoma, soft tissue chondrosarcoma, recurrent giant cell tumour, bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (Nora's lesion) and bone sclerosing dysplasia such as melorheostosis.16

Myositis ossificans of popliteus muscle is extremely rare and we could not find any reported case in literature. We demonstrate a case of myositis ossificans isolated to the popliteus muscle demonstrating typical peripheral calcification on CT (Fig. 9). Concurrent MRI imaging reveals diffuse oedema within the popliteus muscle. As is often the case the calcification can be difficult to appreciate on MR imaging but is seen as subtle T1W peripheral hypointensity (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

T1 (a) and STIR (b) axial sequences showing ill-defined mild TI hyperintensity of the popliteus muscle with subtle peripheral TI hypointensity representing the ossification seen on CT (arrow). MR STIR sequence demonstrates poorly marginated diffuse oedema within popliteus. Axial CT(c) demonstrating peripheral ossification in the popliteus muscle.

6. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS)

PVNS is a member of a family of benign proliferative lesions characterized by villous or nodular hyperplasia of the synovium of a joint, bursa or tendon sheath. In the World Health Organization (WHO) classification it is classified as a member of the tenosynovial giant-cell tumours group of which there are two types with similar histological appearance including a localised or nodular form and a diffuse type also known as PVNS.

The aetiology of PVNS is unknown but has been associated with trauma, haemarthrosis, chronic inflammation, disorders of lipid metabolism and chromosomal abnormalities including trisomy 5 and 7.17

Presentation with mono-articular involvement is the most common clinical scenario with the knee accounting for over 80% of cases.18 The diffuse type of disease tends to be more common in the larger joints.19 Presentation is often ambiguous and insidious but well documented features include slowly progressive pain, joint dysfunction, oedema, and soft tissue swelling.17 Recurrent joint haemarthrosis is a classically described presentation.20 PVNS in the popliteal hiatus and recess along with extension into the tendon sheath is well known and can present with lateral knee pain.

Radiology plays an important role in diagnoses and monitoring of the condition. Radiographs are often normal especially early in the course of the disease. Positive findings on radiographs include joint effusions, which can be hyperdense effusions indicative of haemarthrosis. As the disease progresses bony erosions can develop involving both sides of the joint with thin sclerotic margins.20

MRI is the modality of choice for diagnoses and surveillance of PVNS. The typical appearance is a synovial based mass with T1 intermediate to hypointense signal change. Hemosiderin deposition in the synovium leads to shortening of T2 relaxation times and characteristic T2 hypointensity(Fig. 10, Fig. 11). This effect is exaggerated using magnetic susceptibility artefact on gradient echo sequences which causes the characteristic blooming artefact of PVNS. Post contrast enhancement is variable but often pronounced due to the hyper-vascular nature of the disease. MRI is more sensitive in identifying bone erosions than radiographs.21

Fig. 10.

Axial PD(a) and PDFS (b) demonstrating low signal intensity focus in the muscle belly of popliteus (arrow) in keeping with PVNS.

Fig. 11.

Coronal PDFS (a) and axial PDFS(b) showing focal nodule synovitis within the tendon sheath of the popliteus.

The radiological differential includes amyloid arthropathy, haemophila associated arthropathy, and synovial chondromatosis.

7. Infection

Pyomyositis is a subacute infection, often referred to as a tropical myositis due to its penchant for warmer climes. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative pathogen although atypical organisms are also encountered including anaerobic and mycobacterium (Fig. 12, Fig. 13).22 The risk factors include diabetes, immunocompromised states, intravenous drug use, cellulitis and penetrating injuries. However patients with no significant history can also be affected, and there is a higher incidence among children and young adults.23 The lower limbs tend to be the most commonly affected especially the thigh musculature and in particular the quadriceps, followed by the psoas and gluteal muscles.24 No case of pyomyositis of popliteus has been reported in literature.

Fig. 12.

Axial T1(a) and STIR(b) demonstrating localised abscess formation in popliteus (arrow) and proximal tibia. Aspiration of the popliteus component cultured positive for staphylococcus aureus.

Fig. 13.

Axial T1 (a) and PDFS (b) demonstrating diffuse T1 mild hypointensity with diffuse STIR hyperintensity in the popliteus, tibialis anterior and proximal tibia. Cultures in the case were positive for mycobacterium tuberculous (TB).

MRI remains the gold standard in the radiological diagnoses of pyomyositis. Typically there is generalized quite marked muscle swelling and oedema appearing as T2/STIR hyperintensity with intramuscular abscess formation that is the hallmark of pyomyositis.25 Intramuscular abscess typically appears as T1 hypo/isointense, T2 hyperintense with peripheral post contrast enhancement.26 MRI is also essential in evaluating the extent of the infection including adjacent osteomyelitis or septic arthritis and to assess for complications such as compartment syndrome or necrotizing fasciitis. MRI also aids in planning surgical intervention by delineating degree of soft tissue involvement.27

8. Arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

Vascular malformations often occur as isolated lesions or may occasionally present as part of a spectrum of syndromic disease such as Klippel Trenaunay syndrome or Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT). Typically AVM's occur in the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues however more complex lesions with intra-muscular, intra-articular and intra-osseous components are not uncommon and can create quite a diagnostic challenge.

Vascular malformations can be further subdivided into arteriovenous, capillary, venous, lymphatic and combined malformations.28 The classification of the International Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) has become widely adopted internationally.29 High frequency ultrasound (HFUS) and MRI remain the most useful imaging modalities in radiologically assessment of AVMs. HFUS allows outstanding visualisation of superficial lesions whilst Doppler ultra-sonography is the most straightforward way to assess flow dynamics. MRI is superior for evaluating the physical extent of lesions and relationship to adjacent structures.30 The visualisation of phleboliths in soft tissues on radiography or computed tomography (CT) is also useful and frequently an incidental finding, which the radiologist needs to be aware of. Rarely high flow vascular malformations usually arteriovenous malformation or high flow venous malformations can present on radiographs with an aggressive component causing erosion of the underlying bone. It is likely due to long standing high pressure in the vascular malformation eroding causing pressure induced bony erosion.

Vascular malformation involving the lower limb and in particular the popliteal fossa are well described. However a vascular malformation confined to the popliteus muscle is a rarely encountered lesion (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14.

Axial T1 & PDFS sequences demonstrating relatively homogenous TI iso to mild hyperintensity and PD hyperintensity with a lobulated margin following the course of the popliteus. This was a biopsy proven arteriovenous malformation.

A spectrum of pathologies can involve the popliteus. History of trauma and oedema of popliteus on MRI is strain and presence of peripheral rim of ossification in the muscle belly helps one to make the diagnosis of myositis ossificans. Infective process though rare can be diagnosed with presence of abscess and marked soft tissue oedema on MR with raised inflammatory markers. Avulsion fracture of the popliteus is extremely rare but easy to identify if present. Osseous loose bodies from knee joint can track along the popliteus and so can PVNS. Vascular malformation of popliteus though rare can be diagnosed by presence of vessels and intervening fat.

9. Conclusion

We describe the anatomy and various pathologies of the popliteus. Surgeons and radiologists need to review the popliteus while examining the knee or reporting MRI of knee.

Financial disclosures

No financial disclosures.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jadhav S.P., More S.R., Riascos R.F., Lemos D.F., Swischuk L.E. Comprehensive review of the anatomy, function, and imaging of the popliteus and associated pathologic conditions. Radiographics. 2014;34(2):496–513. doi: 10.1148/rg.342125082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tria A.J., Jr., Johnson C.D., Zawadsky J.P. The popliteus tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(5):714–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson J.H., Jahangir A. StatPearls. Treasure Island. FL; 2020. Tibia fractures overview. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyland S., Varacallo M. StatPearls. Treasure Island. FL; 2020. Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb, popliteus muscle. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan W.R., Zeng F.Q., Wang D.G., Qiu Z.Q. Perforating and deep lymphatic vessels in the knee region: an anatomical study and clinical implications. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87(5):404–410. doi: 10.1111/ans.13893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rehmatullah N., McNair R., Sanchez-Ballester J. A cyamella causing popliteal tendonitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96(1):91E–93E. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13824511649931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bencardino J.T., Rosenberg Z.S., Brown R.R., Hassankhani A., Lustrin E.S., Beltran J. Traumatic musculotendinous injuries of the knee: diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiographics. 2000 doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.suppl_1.g00oc16s103. 20 Spec No:S103-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown T.R., Quinn S.F., Wensel J.P., Kim J.H., Demlow T. Diagnosis of popliteus injuries with MR imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24(7):511–514. doi: 10.1007/BF00202148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guha A.R., Gorgees K.A., Walker D.I. Popliteus tendon rupture: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(4):358–360. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doucet C., Gotra A., Reddy S.M.V., Boily M. Acute calcific tendinopathy of the popliteus tendon: a rare case diagnosed using a multimodality imaging approach and treated conservatively. Skeletal Radiol. 2017;46(7):1003–1006. doi: 10.1007/s00256-017-2623-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noonan T.J., Garrett W.E., Jr. Injuries at the myotendinous junction. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11(4):783–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koong D.P., An V.V.G., Lorentzos P., Moussa P., Sivakumar B.S. Non-operative rehabilitation of isolated popliteus tendon rupture in a rugby player. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2018;30(3):269–272. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.17.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyler P., Saifuddin A. The imaging of myositis ossificans. Semin Muscoskel Radiol. 2010;14(2):201–216. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walczak B.E., Johnson C.N., Howe B.M. Myositis ossificans. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(10):612–622. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Chuah T., Loh T.P., Loi H.Y., Lee K.H. Myositis ossificans. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(4):371. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2011.1.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamalapur M.G., Patil P.B., Joshi S., Shastri D. Pseudomalignant myositis ossificans involving multiple masticatory muscles: imaging evaluation. Indian J Radiol Imag. 2014;24(1):75–79. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.130706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jo V.Y., Fletcher C.D. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46(2):95–104. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falek A., Niemunis-Sawicka J., Wrona K. Pigmented villonodular synovitis. Folia Med Cracov. 2018;58(4):93–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorwart R.H., Genant H.K., Johnston W.H., Morris J.M. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of synovial joints: clinical, pathologic, and radiologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143(4):877–885. doi: 10.2214/ajr.143.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garner H.W., Ortiguera C.J., Nakhleh R.E. Pigmented villonodular synovitis. Radiographics. 2008;28(5):1519–1523. doi: 10.1148/rg.285075190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes T.H., Sartoris D.J., Schweitzer M.E., Resnick D.L. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: MRI characteristics. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24(1):7–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02425937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shittu A., Deinhardt-Emmer S., Vas Nunes J., Niemann S., Grobusch M.P., Schaumburg F. Tropical pyomyositis: an update. Trop Med Int Health. 2020 doi: 10.1111/tmi.13395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chauhan S., Jain S., Varma S., Chauhan S.S. Tropical pyomyositis (myositis tropicans): current perspective. Postgrad Med. 2004;80(943):267–270. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.009274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fayad L.M., Carrino J.A., Fishman E.K. Musculoskeletal infection: role of CT in the emergency department. Radiographics. 2007;27(6):1723–1736. doi: 10.1148/rg.276075033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayeri M.R., Ziai P., Shehata M.L., Teytelboym O.M., Huang B.K. Soft-tissue infections and their imaging mimics: from cellulitis to necrotizing fasciitis. Radiographics. 2016;36(6):1888–1910. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016160068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smitaman E., Flores D.V., Mejia Gomez C., Pathria M.N. MR imaging of atraumatic muscle disorders. Radiographics. 2018;38(2):500–522. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gold R.H., Hawkins R.A., Katz R.D. Bacterial osteomyelitis: findings on plain radiography, CT, MR, and scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157(2):365–370. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.2.1853823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung H.C., Kim D.H., Park B.K., Park M.K. Extensive intramuscular venous malformation in the lower extremity. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012;36(6):893–896. doi: 10.5535/arm.2012.36.6.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madani H., Farrant J., Chhaya N. Peripheral limb vascular malformations: an update of appropriate imaging and treatment options of a challenging condition. Br J Radiol. 2015;88(1047):20140406. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubois J., Alison M. Vascular anomalies: what a radiologist needs to know. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(6):895–905. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1621-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]