Abstract

Novel moral norms peculiar to the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in tension between maintaining one’s preexisting moral priorities (e.g., loyalty to one’s family and human freedoms) and avoiding contraction of the COVID-19 disease and SARS COVID-2 virus. By drawing on moral foundations theory, the current study questioned how the COVID-19 pandemic (or health threat salience in general) affects moral decision making. With two consecutive pilot tests on three different samples (ns ≈ 40), we prepared our own sets of moral foundation vignettes which were contextualized on three levels of health threats: the COVID-19 threat, the non-COVID-19 health threat, and no threat. We compared the wrongness ratings of those transgressions in the main study (N = 396, Mage = 22.47). The results showed that the acceptability of violations increased as the disease threat contextually increased, and the fairness, care, and purity foundations emerged as the most relevant moral concerns in the face of the disease threat. Additionally, participants’ general binding moral foundation scores consistently predicted their evaluations of binding morality vignettes independent of the degree of the health threat. However, as the disease threat increased in the scenarios, pre-existing individuating morality scores lost their predictive power for care violations but not for fairness violations. The current findings imply the importance of contextual factors in moral decision making. Accordingly, we conclude that people make implicit cost-benefit analysis in arriving at a moral decision in health threatening contexts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12144-021-01941-y.

Keywords: Moral foundations theory, Vignettes, COVID-19, Health threat

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) emerged in December 2019 and rapidly progressed to a global health crisis within several months. At the time of this writing (November, 2020), COVID-19 has infected more than 50 million people and caused over 1.3 million deaths worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020). As COVID-19 poses a significant risk of death or severe illness for individuals, the disease is an existential threat for human beings (Pyszczynski et al., 2020).

Significant changes in social structures and community practices have occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic (Francis & McNabb, 2020). New moral norms such as maintaining physical distance from others, increased hygiene, and lockdowns have been introduced and encouraged by official authorities. Relatedly, the pandemic (especially, COVID-19 avoiding behaviors) has raised a number of distressing moral dilemmas. For example, people began to question whether it is morally acceptable to prohibit elderly parents from going out, force family members to change their clothes when arriving home, and avoid family gatherings. Such situations create tension between maintaining one’s moral priorities (e.g., loyalty) and reducing the spread of COVID-19 (Prosser et al., 2020). Although these issues make the COVID-19 pandemic quite relevant to moral decision making research, only limited studies have examined how this pandemic influences moral judgments (Antoniou et al., 2020; Francis & McNabb, 2020). In addressing this gap, the current study draws on the Moral Foundation Theory (MFT; Haidt, 2007), and mainly compares the wrongness ratings of transgressions that are committed to avoid varying levels of disease threats (including COVID-19).

Moral Foundations Theory

MFT proposes that humans have five innate moral foundations: care/harm, fairness/cheating, in-group loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation (Graham et al., 2013). Liberty/oppression has also been proposed as a sixth foundation of morality (Iyer et al., 2012). The care/harm foundation relates to the feeling of compassion towards the victims of psychological or physical injuries. The fairness/cheating foundation is concerned with preserving justice, equity, and trust. The in-group loyalty/betrayal foundation deals with the sacrifice for, devotion to, and support of an in-group. The authority/subversion foundation is associated with respect and obedience to traditions. The sanctity/degradation foundation focuses upon self-control, purity of the body, and moral disgust (Graham et al., 2013). The first two foundations (care/harm and fairness/cheating) emphasize the provision and protection of individual rights and freedoms and are categorized as the “individualizing foundations”. In-group loyalty, authority, and purity are referred to as “binding foundations” as they are adopted as a group-oriented morality. They are primarily concerned with preserving the group as a whole. The liberty/oppression foundation deals with the domination and coercion by the more powerful upon the less so (Haidt, 2012).

Disease Threat and Evaluations of Moral Foundation Transgressions

The wrongness evaluations of moral foundation violations might change depending on contextual cues. Situational factors such as mental states (knowledge and intent of the perpetrator), group membership, and social threat play an important role in evaluating the extent to which a moral transgression is wrong (Ardila-Rey et al., 2009; Bettache et al., 2018; Ekici, 2019; Giffin & Lombrozo, 2018; Valdesolo & DeSteno, 2007). For example, Ekici (2019) found that Syrian refugee adolescents evaluated transgressions of moral foundations more acceptable when they were committed to avoid the war threat than when committed without an excuse. In the present study, we questioned whether the disease threat was also influential in evaluating the severity of moral foundation transgressions. As COVID-19 avoiding behaviors are highly moralized within communities (Francis & McNabb, 2020; Prosser et al., 2020), moral transgressions that are committed to avoid COVID-19 might be considered more acceptable than violations that are committed to reduce other disease threats (i.e., non-COVID-19 heath threats), and violations committed without an apparent health reason.

Moralization of COVID-19 Avoiding Behaviors

Preventing the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic necessitates large scale behavioral changes; consequently, such efforts place “significant psychological burdens” on individuals (Diaz & Cova, 2020; van Bavel et al., 2020, p. 460). According to public health experts, slowing viral transmission during COVID-19 largely depends on individual behaviors rather than pharmaceutical interventions (Ferguson et al., 2020). Correspondingly, international organizations (e.g., the World Health Organization) and governments have provided official recommendations to slow the spread of the disease, such as wearing masks, washing hands, social distancing, and limiting social interactions (Diaz & Cova, 2020). Failure to follow those COVID-19 avoiding behaviors can increase infection rates and thus hasten the spread of the virus.

Morality plays an important role in regulating individuals’ behaviors in social life (Araque et al., 2019; Ellemers et al., 2013; Ellemers & van den Bos, 2012) by public condemnation of immoral behaviors (Prosser et al., 2020). Similarly, during the pandemic, non-compliant behaviors such as not wearing mask or not keeping physical distance have been moralized at a community level (Francis & McNabb, 2020; Prosser et al., 2020). For example, individuals who fail to keep physical distance from others face social sanctioning. Therefore, previously neutral behaviors (e.g., arranging a house party or visiting grandparents) have been carried into the moral domain during the pandemic (Brown, 2018).

This moralization process influences community norms in ways that encourage adherence to those COVID-19 avoiding behaviors (Francis & McNabb, 2020). Recent empirical findings have evidenced that the moralization of COVID-19 mitigating practices predicted individuals’ engagement in those governmentally recommended behaviors (Francis & McNabb, 2020). In this scenario, individuals who fail to follow moral proscriptions pose a risk of death or severe health complications for themselves and others. At this point, people make an implicit cost-benefit analysis between the costs of adherence to COVID-19 avoiding behaviors (e.g., decreased creativity, violation of preexisting moral values such as loyalty) and its disease-specific benefits (i.e., reduced risk of catching and spreading the virus). “These benefits would have been more likely to outweigh the costs” (p. 44) when the disease threat is high or is perceived to be so (Murray et al., 2019). Correspondingly, the higher the disease threat, the higher the individual cost. Therefore, a moral transgression committed to avoid it is likely to become more acceptable.

As the COVID-19 avoiding practices are highly encouraged and moralized within communities, we expect that people would consider moral transgressions committed to avoid COVID-19 more acceptable than violations committed without this kind of justification. For a comparative understanding, we created three very similar variations of the same moral foundation vignettes in the present study. A transgressor commits a moral foundation violation to avoid the personal risk of infection of COVID-19 in Type A scenarios and that of non-COVID-19 illness in Type B scenarios. The same transgression is committed without an ostensible health concern in Type C scenarios. Our first hypothesis is as follows:

H1: As the disease threat increases, the moral violation committed to avoid illness would become more acceptable. Individuals would evaluate Type A transgressions more acceptable than Type B and Type C violations. Since the health threat is still salient in Type B scenarios, they would also be evaluated as more acceptable than Type C scenarios.

Disease Threat and Endorsement of Moral Foundations

Individuals’ endorsement of moral foundations is not always fixed (Alper et al., 2019). Moral foundations might be differentially endorsed depending on contextual factors. Past studies indicate that situational cues such as abstract (vs. concrete) thinking (Napier & Luguri, 2013), or societal threats (Alper et al., 2019; Ekici, 2019; van de Vyver et al., 2016) can shape the endorsement of particular moral foundations. For example, van de Vyver et al. (2016) report greater endorsement of the in-group loyalty foundation and lower endorsement of the fairness foundation following the July 7, 2005 London Bombings. Inspired from this literature, we questioned how the COVID-19 pandemic might influence the endorsement of different moral foundations. To understand which foundations of morality are more endorsed, we ranked the wrongness ratings of transgressions concerning varying moral foundations within different levels of health threat. We assumed that the impact of the disease threat might be more relevant to the sanctity/degradation, care/harm, and fairness/cheating foundations. The underlying rationale for each foundation is explained below.

The sanctity/degradation foundation is functionally relevant to the mitigating health threat (Murray et al., 2019). Infectious diseases have posed a threat to reproductive fitness for a very long time (Schaller & Park, 2011). In an evolutionary response, the behavioral immune system detects the presence of pathogens in the environment. Upon detection, the immune system triggers the adaptive psychological responses that facilitate the avoidance of those pathogens. The sanctity/degradation-based proscriptions lessen the disease threat by regulating behaviors that are most conducive to the spread of pathogens, such as increased hand washing, physical distancing, and hygienic food preparation (Murray et al., 2019). In line with this reasoning, in the current study, we expected to observe greater endorsement of the sanctity/degradation foundation as the disease threat increases.

Individuating foundations, namely, care/harm and fairness/cheating are critical for each and every individual in the community to survive during the pandemic. There are no differences among various human societies or groups in terms of vulnerability to infectious diseases (Fabrega, 1997; Ntontis & Rocha, 2020); furthermore, everyone suffers from almost the same problems stemming from the pandemic (Ntontis, 2018). The sense that the impact of the disease is equally shared might be characterized as an experience of “we are all in this together” or “common fate” (Ntontis et al., 2019). This perception might be the point where individuating moral foundations gain greater importance in the pandemics.

Firstly, the care/harm foundation connects the perceptions of suffering with motivations to care, nurture, and protect. All social animals face an adaptive challenge of caring for young, vulnerable, or injured offspring for a long time (Graham et al., 2013). In relation to this challenge, the original triggers of the care/harm foundation are suffering, distress, or neediness expressed by one’s child. However, the care/harm foundation is not limited to the mother-child relationship. Illnesses and infectious diseases are also other contexts in which individuals need care and produce signals of suffering and distress. Care/harm proscriptions increase the chances of survival for every individual during pandemics or disease outbreaks by ensuring and encouraging care for people in need. Relatedly, in this study, we predicted greater endorsement of the care/harm foundation as the disease threat increases.

Secondly, the fairness/cheating foundation relates to preserving fair treatment, justice, and equality in communities (Graham et al., 2013). All mammals including the most similar to humans, such as chimpanzees and bonobos, face the adaptive challenge of reaping the benefits of two-way cooperation or exchanges. Relatedly, individuals whose minds are structured to be extremely sensitive to the signs of cheating, deception, and cooperation possess an advantage over those who act based on their general intelligence. The original triggers of fairness/cheating include acts of deception, cheating, or cooperation (Graham et al., 2013). The current pandemic provides a fertile platform for the upsurge in injustices such as mask hoarding or inflating mask prices. Furthermore, when the state intervenes selectively to certain groups to control the pandemic, the issues of equal treatment or fairness might also rise to the surface and cause discomfort in societies (Stott & Radburn, 2020). Evidence from pandemics in different parts of the world reveals that communities which successfully cope with the epidemic are those characterized by norms of trust and reciprocity (Ntontis & Rocha, 2020). Correspondingly, fairness proscriptions might increase the chances of survival for every individual by ensuring equal treatment in the face of COVID-19.

To sum up, the above-mentioned three foundations, namely, sanctity/degradation, care/harm, and fairness/cheating appear to be decisive for survival during pandemics. Based on this theoretical reasoning, we hypothesized that as the disease threat increases, people would endorse more sanctity/degradation, fairness/cheating, and care/harm foundations than other foundations. More specifically our hypothesis is as follows:

H2: The wrongness ratings of transgressions concerning sanctity/degradation, fairness/ cheating, and care/harm foundations would be ranked as follows: Type A scenarios < Type B scenarios < Type C scenarios.

Chronic Moral Foundations as the Determinants of Moral Priorities in Threatening Contexts

According to the motivated social cognition model by Jost et al. (2003), conservatism is helpful in soothing anxieties and threats that people experience in the face of uncertainties of everyday life. People react to the real-life or laboratory threats with shifting to an attitudinally conservative stance (e.g., Bonanno & Jost, 2006; Ullrich & Cohrs, 2007). There is also evidence regarding a conservative shift in terms of greater endorsement of traditional gender roles (Rosenfeld & Tomiyama, 2020) or greater support for more right-wing candidates (Karwowski et al., 2020) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite this clear pattern of attitudinal shift towards conservatism, many studies have revealed that conservative people downplay the coronavirus threat by endorsing COVID-19 specific political views which reduce the virus’s severity in their eyes (Calvillo et al., 2020; Conway et al., 2020).

In this study, we attempt to understand how people make moral decisions in choosing between the maintenance of their moral priorities and avoidance of various kinds of health threats (including the COVID-19 threat). One of our basic aims was to unearth the interaction between people’s chronic moral priorities and contextual health threat in deciding about specific kinds of moral dilemmas. We will refer to people’s context-independent, pre-existing moral priorities as “chronic” throughout the current text to distinguish between general moral tendencies and context-dependent moral judgments. Given the aforementioned findings that conservatives were free from the perceived threat of COVID-19, we did not expect to find a decrease in the power of chronic binding foundations in predicting the wrongness ratings of binding morality violations across different health threat conditions. However, since liberals rate COVID-19 as more threatening than do conservatives (Malloy & Schwartz, 2020), it is highly probable that liberals would experience incongruence in preserving their individuating moral priorities and reducing the health threat, given the ethical dilemmas included in the present study. Accordingly, chronic individuating moral priorities might lose their predictive power in explaining how people evaluate individuating morality violations which were committed to protect one from various health threats.

Our predictions could also be based upon the reactive liberal hypothesis (Nail et al., 2009). This account asserts that liberals’ moral priorities are more susceptible to contextual threat salience than conservatives since the latter group is chronically sensitive (prepared) to threats. For example, liberals experienced a greater degree of a conservative shift than did conservatives following the July 7, 2005, London Bombings by adopting the ingroup loyalty foundation and reducing their priority for the fairness foundation (van de Vyver et al., 2016). Accordingly, a consistent association between the chronic priority of binding foundations and the wrongness ratings of binding morality violations would likely to be observed independent of the salience of the health threat in the current scenarios. In contrast, chronic individuating preferences would only be associated with the evaluations of individuating morality violations when there is no apparent health threat in the scenarios. Our third hypotheses can be re-phrased as follows:

H3a: Participants’ chronic binding morality preferences would predict their evaluations of all kinds of binding morality violations, independent of the degree of the health threat in scenarios. That is to say, the chronic preference for binding morality would consistently predict the wrongness ratings of loyalty, authority, and purity violations in all types of scenarios (Type A, B, &C).

H3b: Participants’ chronic individuating morality preferences would predict the wrongness ratings of individuating morality (i.e., care and fairness) violations only for Type C scenarios. However, chronic individuating morality scores would lose their predictive power concerning the Type A and B individuating morality scenarios.

The disease threat intrinsic to the current pandemic is unpredictable, mysterious, infectious, and threatening to all people (Fabrega, 1997). Some studies have examined the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on moral decision making in adults. However, most of these studies have focused on contrasting utilitarian and deontological responses to hypothetical dilemmas and revealed mixed findings (Antoniou et al., 2020; Francis & McNabb, 2020; Navajas et al., 2020). To the best of our knowledge, no study has examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the endorsement of moral foundations. The current study might be a unique attempt in addressing this gap in the literature. In addition, if only particular types of moral sensitivities (e.g., care, fairness, or purity) surface in health threatening contexts (including pandemic conditions); public messages prevalent in the mass media could be more effective in combatting public health problems when such messages are re-tailored according to those moral foundations. In this respect, the present findings could have applied implications as well.

Method

Participants

We reached 452 participants via an online survey tool at the very first days of the COVID-19 normalization process in Turkey (May 12th–30th, 2020). A great majority of the participants (91.7%) were undergraduates, most of whom were students in İstanbul, İzmir, and Ankara. Because 56 participants failed to pass either of two attention checks included in the Moral Foundations Questionnaire ([MFQ] which is covered below), we removed them from analysis. There were 319 females and 77 males in the final set. Their ages ranged between 18 and 59 (M = 22.47, SD = 5.95). Only one participant reported to have a diagnosis of COVID-19. However, there were 40 participants with close family or friends receiving COVID-19 treatment, 23 participants who had lost close members to COVID-19, and 64 participants with close family or friends who had recovered from COVID-19. Since these COVID-19-related statistics were not impactful on the study variables, we also included those participants for further analyses. Participants’ ideological status was around the mid-point of a 10-point left-right scale (M = 4.78, SD = 1.87).

Instruments

Moral Violation Vignettes

We basically questioned whether wrongness ratings of the same transgressions would change when they were committed to protect oneself from varying degrees of a health threat. Accordingly, we prepared various moral transgression scenarios regarding different MFT dimensions (i.e., Care, Fairness, Liberty, Loyalty, Authority, and Purity). We created three versions of the same scenarios. Type C violations were neutral; they were committed with no apparent health reasons. In Type A vignettes, a transgressor committed the same (or very similar) C type moral violation with an aim to protect him/herself from the COVID-19 threat. In Type B scenarios, those violations were committed to avoid various non-COVID-19 health threats (e.g., influenza, allergy).

Prior to administering the main study, we prepared a large pool of moral violation vignettes. In the preparation of those vignettes, we modeled the contents of moral violation vignettes written by Clifford et al. (2015). To check whether our vignettes violated the intended moral foundation, we took two different experts’ views who had been extensively studying MFT in Turkey. From the larger set of moral violations, we selected the scenarios that the experts had reached a 100% consensus regarding the moral foundations of these violations. This step ensured the face validity of our vignettes, and we were left with 60 scenarios. Next, we conducted two pilot tests to ensure that neutral scenarios (Type C) and health threat scenarios (Type A & B) significantly differentiated from each other concerning the degree of health threat directed towards the transgressor. In other words, the aim of those pilot tests was to ascertain that Type C violations were not perceived to be committed with an apparent or implicit health threat. We obtained two different samples (ns = 42, 40) for the first pilot test, and another sample for the second pilot test (n = 41). Sex distribution was similar across different samples. The first two samples were equal to each other in terms of their mean age, religiosity levels, and ideological status. Yet, the third sample was older, more religious, and ideologically more right-oriented than the first two samples (see Table 1 in the Supplementary Material for further demographics about them). All pilot test participants were asked to rate the wrongness degree of violations in the scenarios (1 = not at all wrong; 5 = very wrong), and the degree of health threat which might lead the transgressor to commit those violations (1 = There is no health risk for the transgressor to 5 = The transgressor is fully under health threat). Since our initial scenario set was bulky (i.e., 60 scenarios to be evaluated), we divided it into two and recruited two different samples for the first pilot test. The scenarios which met our expectations in the first pilot test were warranted for use in the main study. However, we revised some of our scenarios for a second pilot test, and recruited a third group of participants to evaluate the qualities of those scenarios. Table 2 in the Supplementary Material presents the exact wording of the scenarios in the pilot tests.

Table 1.

Quality of scenarios in terms of the degree of health threat

| Foundation | Type of threat | Scenarios | Perceived health threat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Differences across scenarios | |||

| Care-1 | Type A | You see someone shouting at tourists and removing them from his/her shop for fear of coronavirus infection. | 3.44 (.14) |

F(2, 80) = 24.06 p < .001 A > B > C |

| Type B | You see someone shouting at tourists and removing them from his/her shop for fear of contracting bird flu. | 2.80 (.18) | ||

| Type C | You see someone shouting at tourists passing by his/her shop and trying to drive them away. | 2.07 (.18) | ||

| Care-2 | Type A | You see someone on the bus shouting at a coughing passenger for fear of coronavirus infection. | 3.98 (.15) |

F(2, 82) = 56.64 p < .001 A = B > C |

| Type B | You see someone scolding a passenger who is constantly sneezing on the minibus for fear of contracting the flu. | 3.69 (.17) | ||

| Type C | You see someone scolding a passenger who missed his/her stop on the subway. | 1.79 (.16) | ||

| Fairness-1 | Type A | You see someone in the queue for the COVID-19 test who takes advantage of his/her friend working there so as to go to the front of the queue and thus not risk coronavirus infection. | 3.10 (.18) |

F(2, 80) = 24.48 p < .001 A > B > C |

| Type B | You see someone in the hospital waiting to be examined who takes advantage of his/her neighbor working there so as to avoid waiting in a queue and thus not risk infection with seasonal flu. | 2.51 (.20) | ||

| Type C | You see someone who does not wait in the queue at the post office by taking advantage of the fact that his/her friend works there. | 1.61 (.16) | ||

| Fairness-2 | Type A | You see someone who buys all of the masks remaining in his/her district to protect him/herself from coronavirus. | 3.12 (.18) |

F(2, 82) = 14.51 p < .001 A = B > C |

| Type B | You see someone who collects all of the flu medicines left in the pharmacies in his/her district due to his/her having frequent colds. | 3.07 (.17) | ||

| Type C | You see someone who buys all of the bread for him or herself in the only market of his/her town. | 2.14 (1.15) | ||

| Liberty-1 | Type A | You see a man who forces his wife to wear a mask when going outside so that she does not carry the coronavirus home. | 3.98 (.19) |

F(2, 82) = 28.51 p < .001 A > B > C |

| Type B | You see a man who forces his wife to wear a woolen tank top while going out so that she won’t bring home cold and sickness. | 2.74 (.15) | ||

| Type C | You see a man who forces his wife to dress only in a way that he approves. | 1.98 (.20) | ||

| Liberty-2 | Type A | You see someone who wants one’s sibling coming into the home from outside to undress down to his/her underwear before entering the house, so that s/he does not carry coronavirus indoors. | 3.55 (.19) |

F(2, 78) = 7.47 p < .001 A > B = C |

| Type B | You see someone who wants his or her colorfully dressed sibling to change his/her clothes because excessively colored clothing triggers his/her migraine. | 2.52 (.18) | ||

| Type C | You see someone who asks his or her sibling to change his/her clothes because s/he is not dressing in a way that s/he approves. | 2.80 (.21) | ||

| Loyalty-1 | Type A | You see an asthma patient trying to leave Turkey by claiming that Turks would fail in their fight with the coronavirus. | 3.02 (.22) |

F(2, 80) = 30.70 p < .001 A = B > C |

| Type B | You see a chronic diabetes patient wanting to live in another country by claiming that Turks offer inadequate in healthcare. | 2.78 (.18) | ||

| Type C | You see someone who says s/he wants to live abroad because s/he finds Turks uncivilized and backward. | 1.58 (.15) | ||

| Loyalty-2 | Type A | You see someone who refuses to be his or her sibling’s wedding witness due to the coronavirus epidemic. | 3.55 (.18) |

F(2, 82) = 42.35 p < .001 A = B > C |

| Type B | You see someone who doesn’t attend his or her sibling’s wedding in the country because s/he is allergic to pollen. | 3.33 (.17) | ||

| Type C | You see someone not attending his or her sibling’s wedding. | 1.69 (.15) | ||

| Authority-1 | Type A | You see someone shouting publicly at his or her boss who refuses to take action against the coronavirus at work. | 4.17 (.15) |

F(2, 80) = 61.70 p < .001 A > B > C |

| Type B | You see someone publicly shouting at his or her boss who refuses to buy a heater at work, even though the employees often get cold and sick. | 3.61 (.19) | ||

| Type C | You see someone raising his/her voice to his or her boss in public. | 1.83 (1.16) | ||

| Authority-2 | Type A | You see a hospital cleaner who refuses to perform the tasks assigned to him/her because the hospital officials do not provide COVID-19 protective clothing for their employees. | 4.33 (.15) |

F(2, 82) = 19.33 p < .001 A > B = C |

| Type B | You see a cleaner who refuses to fulfill his/her duty because the hospital authorities do not provide non-slip soles for hospital staff working on wet ground. | 3.59 (.14) | ||

| Type C | You see a caregiver who refuses to follow the hospital director’s instructions. | 3.14 (.18) | ||

| Purity-1 | Type A | You see someone who burned the Holy Quran which s/he recently bought from a bookshop after learning that the bookseller of that shop was diagnosed with COVID-19. | 2.60 (.20) |

F(2, 78) = .14 p > .05 A = B = C |

| Type B | You see someone throwing away the old Holy Quran in her room because she is allergic to book dust. | 2.50 (.21) | ||

| Type C | You see someone who tears and burns the Holy Quran. | 2.47 (.25) | ||

| Purity-2 | Type A | You see someone who cuts up the Turkish flag in her home to make a mask to protect against coronavirus. | 3.17 (.19) |

F(2, 82) = 16.83 p < .001 A > B > C |

| Type B | You see someone tearing the Turkish flag and wrapping it around his/her sprained ankle. | 2.64 (.17) | ||

| Type C | You see someone sitting on the Turkish flag in the park. | 1.90 (.20) | ||

Notes. Health threat scores were computed on three different pilot test datasets (Ns ≈ 40). Type A scenarios refers to the salience of the COVID-19 threat, Type B scenarios to the salience of a non-COVID-19 health threat, and Type C scenarios to the absence of health threat. SD = Standard deviation. ** p < .01, * p < .05

Table 2.

Wrongness ratings of scenarios and their correlations with MFQ-scores

| Scenario codes | Mean wrongness (SD) | Correlations between wrongness ratings and MFQ-dimensions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care | Fairness | Liberty | Loyalty | Authority | Purity | ||

| Care1 – Type A | 3.92 (1.02) | .02 | .02 | .04 | −.01 | −.02 | .05 |

| Care1 – Type B | 4.10 (.92) | .04 | .02 | −.02 | .00 | .01 | .07 |

| Care1 – Type C | 4.54 (.69) | .07 | .06 | .02 | −.03 | −.04 | .00 |

| Care2 – Type A | 2.83 (1.09) | .02 | .00 | −.07 | .02 | .06 | .08 |

| Care2 – Type B | 3.65 (.96) | −.01 | −.02 | .12* | −.13** | −.10* | −.09 |

| Care2 – Type C | 4.58 (.69) | .15** | .04 | .13** | −.03 | −.10 | .05 |

| Fairness1 – Type A | 4.27 (.89) | .07 | .13** | −.05 | −.07 | −.07 | .01 |

| Fairness1 – Type B | 4.38 (.81) | .12* | .18** | −.03 | −.07 | −.11* | .02 |

| Fairness1 – Type C | 4.07 (.90) | .09 | .11* | −.01 | −.02 | .00 | .11* |

| Fairness2 – Type A | 4.70 (.69) | .18** | .07 | .04 | .03 | −.04 | .01 |

| Fairness2 – Type B | 4.62 (.72) | .16** | .06 | .08 | .10 | −.02 | .01 |

| Fairness2 – Type C | 4.51 (.84) | .09 | .02 | −.05 | .09 | .02 | .12* |

| Liberty1 – Type A | 1.76 (.83) | −.07 | −.10* | −.05 | .01 | −.04 | .01 |

| Liberty1 – Type B | 2.60 (1.08) | −.13* | −.11* | −.03 | −.14** | −.11* | −.03 |

| Liberty1 – Type C | 4.65 (.68) | .17** | .20** | .35** | −.16** | −.31** | −.25** |

| Liberty2 – Type A | 2.84 (1.29) | −.03 | −.06 | −.10* | .02 | −.02 | .08 |

| Liberty2 – Type B | 2.34 (1.09) | −.03 | −.06 | .02 | −.00 | −.03 | −.02 |

| Liberty2 – Type C | 4.39 (.94) | .19** | .08 | .38** | −.13** | −.26** | −.25** |

| Loyalty1 – Type A | 2.79 (1.28) | .05 | −.08 | −.19** | .30** | .30** | .31** |

| Loyalty1 – Type B | 2.34 (1.22) | .09 | −.10 | −.22** | .31** | .30** | .31** |

| Loyalty1 – Type C | 3.23 (1.27) | .09 | −.04 | −.20** | .33** | .28** | .34** |

| Loyalty2 – Type A | 2.21 (1.03) | .06 | .04 | −.07 | .19** | .23** | .19** |

| Loyalty2 – Type B | 2.41 (1.11) | .06 | −.01 | −.0.09 | .21** | .19** | .22** |

| Loyalty2 – Type C | 3.03 (1.19) | .20** | .05 | −.17** | .24** | .28** | .29** |

| Authority1 – Type A | 2.34 (1.06) | −.17** | −.11* | −.23** | .10* | .18** | .13** |

| Authority 1 – Type B | 2.55 (1.08) | −.03 | −.11* | −.13** | .06 | .13* | .19** |

| Authority 1 – Type C | 3.67 (.90) | .05 | .01 | −.07 | .13* | .19* | .15** |

| Authority 2 – Type A | 1.61 (.89) | −.11* | −.17** | −.19** | .21** | .22** | .20** |

| Authority 2 – Type B | 2.12 (1.06) | −.11* | −.12* | −.22** | .17** | .21** | .20** |

| Authority 2 – Type C | 3.90 (.91) | .15** | .01 | −.05 | .25** | .27** | .19** |

| Purity1 – Type A | 3.67 (1.41) | .06 | −.05 | −.26** | .35** | .41** | .46** |

| Purity1 – Type B | 3.90 (1.34) | .09 | −.04 | −.34** | .42** | .43** | .56** |

| Purity1 – Type C | 4.36 (1.06) | .08 | .05 | −.25** | .41** | .36** | .44** |

| Purity2 – Type A | 3.55 (1.33) | .15** | .04 | −.17** | .47** | .44** | .35** |

| Purity2 – Type B | 3.55 (1.31) | .14** | .03 | −.20** | .50** | .48** | .35** |

| Purity2 – Type C | 4.09 (1.11) | .08 | .01 | −.15** | .45** | .43** | .32** |

Notes. Wrongness ratings of the scenarios and their correlations with MFQ-dimensions were computed in the main analysis set (N = 396). SD = Standard deviation. ** p < .01, * p < .05

We followed several guidelines while revising our vignettes during pilot testing. We largely tried to ensure that Type A scenarios were perceived as more health-threatening than Type B scenarios which were, in turn, also perceived to be more health-threatening than Type C scenarios. In doing so, for example, we replaced the phrase “surgical operation” in the Type B version of the Loyalty-1 set in the first pilot test with the term “diabetes” in the second pilot test. Furthermore, to combat the ceiling effect (Goodwin, 2010), we discarded or revised some scenarios that had overtly violent content (e.g., “stoning and chasing tourists with sticks” in the initial version of care-1 set), weird cases (e.g., “taking pleasure in wearing the mask that someone made from a sanitary napkin” in the discarded purity-3 set), or provocative phrases (e.g., “telling his/her boss that s/he is ignorant” in the discarded authority-3 set). Some scenarios were also dropped because they were not at all perceived as a moral transgression (e.g., “leaving someone’s father’s company and starting to work for a rival company” in the loyalty-4 set).

We also purposefully selected the scenarios which could plausibly occur in everyday life during the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g., “mask storage” and “having the COVID-19 test without waiting in line” for fairness sets). In validating the scenarios at this step, we also checked correlations whenever possible among the scenario sets which were supposed to represent the same moral foundation. Inter-scenario positive correlations within the same moral domain informed us that different scenarios were conceptually linked to each other. In the end, we selected 2 vignette sets for six moral foundations, and each set included its own Type A, Type B, and Type C versions.

Table 1 presents a summary of the quality of final scenarios in terms of the participants’ health threat attributions. Generally speaking, we can say that Type C scenarios were attributed as lower levels of health threat than were Type A and Type B scenarios. However, in the case of the purity-1 set, three versions of the vignettes were undistinguishable in terms of health threat evaluations. It seemed that participants underestimated the health threat in Type A and Type B scenarios even though there was no apparent health threat in Type C scenarios. This underestimation might reflect the possibility that there could be no valid reason to commit certain types of purity violations (e.g., throwing away a divine book) in the eye of the current participants. However, we decided to use this set during our main analysis since our main findings did not change even when excluding this purity set (see Supplementary Material for this extra analysis).

In further validating the moral foundations of each scenario set, we also examined the correlations of the wrongness ratings of the vignettes with MFQ scores in the main dataset (see Table 2). We expected to find a positive correlation at least between the evaluations of Type C scenarios (which are inherently context-free in terms of health threat) and MFQ scores of the related foundations. By and large, the descriptive patterns seemed to confirm the validity of our vignettes in touching upon the target moral foundation. The only exceptions were Type C scenarios of the care-1 and fairness-2 sets. Even though these vignettes did not correlate consistently with the related MFQ dimensions, we decided to use them due to the following reasons. First, in writing the Type A versions of those sets, we focused on the events that are prevalent in everyday life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stockpiling (particularly mask storage) or discrimination against (Korean and other Asian) tourists were common issues at the beginning of the pandemic (and occurred while we performed this study). We thought that it would be interesting to understand how those acts were morally evaluated. This rationale explains our designing the Type B and Type C versions of such acts. Second, generally speaking, the wrongness ratings of the care-1 and fairness-2 sets were meaningfully correlated with the other set of scenarios representing the same moral domain, but the wrongness ratings of the care-1 and fairness-2 sets did not correlate with the other scenarios pertaining to unrelated moral foundations (see Table 3 in the Supplementary Material to check the bivariate correlations among the scenarios in the main study). These correlational patterns also indirectly imply the validity of so-called problematic vignettes. Third, while constructing our scenarios, we modelled the scenario contents of Clifford et al.’s (2015) study. In their study, discriminatory acts were also classified as care violation by respondents, and unequal distribution of limited resources as fairness violation. Fourth, the expert views also ensured the face validity of our vignettes with a 100% consensus concerning their moral foundations. Accordingly, we preferred to use care-1 and fairness-2 sets in our main analysis. We also checked whether the main findings of the current study changed without including those vignettes in our analysis. As can be found in the Supplementary Material, our main conclusions remained unchanged even when we excluded those seemingly problematic scenarios. Consequently, since other foundations were represented by two vignette sets, for the sake of consistency, we also used two scenario sets for the fairness and care foundations.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables

| Variables Names | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Care-A | 3.38 (.85) | 1 | .57** | .28** | .10* | .18** | .14** | .19** | .13** | .10 | .12* | .05 | .15** | .40** | .19** | .14** | .04 | .03 | -.03 | .02 | .05 | .10* | .07 | .05 | -.12* | -.11* |

| 2. Care-B | 3.87 (.76) | 1 | .39** | .21** | .29** | .24** | .21** | .10 | .17** | .10* | .02 | .09 | .16** | .10* | .24** | .13* | .03 | .07 | .01 | -.05 | .07 | -.08 | -.03 | -.00 | .01 | |

| 3. Care-C | 4.56 (.55) | 1 | .26** | .37** | .21** | .10* | .08 | .30 | .06 | .07 | .10* | -.02 | .05 | .25** | .09 | .10* | .14** | .12* | -.03 | .09 | .08 | .03 | -.01 | -.06 | ||

| 4. Fairness-A | 4.49 (.61) | 1 | .71** | .61** | .10* | .07 | .20** | .05 | .00 | .15** | -.04 | -.04 | .16** | .03 | .06 | .09 | .17** | -.04 | .11* | .08 | .03 | -.05 | -.09 | |||

| 5. Fairness-B | 4.50 (.59) | 1 | .58** | .14** | .08 | .26** | .07 | .03 | .15** | -.03 | -.01 | .20** | .08 | .11* | .14** | .20** | -.02 | .07 | .03 | .03 | -.04 | -.04 | ||||

| 6. Fairness-C | 4.29 (.63) | 1 | .15** | .08 | .16** | .16** | .12* | .24** | .06 | .05 | .21** | .13* | .09 | .12* | .13* | .09 | .08 | .06 | .11* | -.04 | -.12* | |||||

| 7. Liberty-A | 2.29 (.86) | 1 | .33** | .02 | .13* | .11* | .10* | .20** | .15** | .15** | .07 | .05 | -.01 | -.08 | .02 | .05 | -.05 | .12* | -.22** | -.17** | ||||||

| 8. Liberty-B | 2.47 (.80) | 1 | .19** | .05 | .19** | .02 | .18** | .11* | .05 | .03 | -.02 | -.01 | -.13* | -.08 | .02 | .14** | -.04 | -.05 | -.08 | |||||||

| 9. Liberty-C | 4.51 (.73) | 1 | -.09 | -.07 | -.10* | -.17** | -.08 | .02 | -.09 | -.14** | -.03 | .20** | -.29** | .24** | -.06** | -.34** | .18** | -.00 | ||||||||

| 10. Loyalty-A | 2.50 (.92) | 1 | .61** | .50** | .29** | .17** | .14** | .37** | .38** | .32** | .03 | .38** | .04 | .13* | .15** | .07 | .03 | |||||||||

| 11. Loyalty-B | 2.38 (.90) | 1 | .55** | .29** | .24** | .24** | .41** | .40** | .31** | .03 | .39** | .08 | .08 | .22** | .15** | .10 | ||||||||||

| 12. Loyalty-C | 3.13 (.94) | 1 | .22** | .20** | .32** | .41** | .45** | .38** | .12* | .44** | .10* | .07 | .30** | .09 | .02 | |||||||||||

| 13. Authority-A | 1.97 (.80) | 1 | .50** | .17** | .23** | .19** | .09 | -.20** | .24** | .02 | .08 | .25** | -.10 | -.02 | ||||||||||||

| 14. Authority-B | 2.33 (.85) | 1 | .25** | .27** | .24** | .14** | -.13** | .24** | .08 | -.01 | .24** | .02 | .03 | |||||||||||||

| 15. Authority-C | 3.78 (.73) | 1 | .33** | .34** | .41** | .09 | .28** | .15** | -.01 | .21** | .01 | -.04 | ||||||||||||||

| 16. Purity-A | 3.61 (1.13) | 1 | .76** | .68** | .08 | .57** | .14** | .00 | .31** | .10* | .06 | |||||||||||||||

| 17. Purity-B | 3.73 (1.12) | 1 | .73** | .08 | .63** | .16** | .01 | .36** | .09 | .03 | ||||||||||||||||

| 18. Purity-C | 4.22 (.94) | 1 | .08 | .53** | .10 | -.03 | .30** | .14** | .07 | |||||||||||||||||

| 19. MFQ-Individ. | 4.16 (.46) | 1 | .18** | .24** | .05 | -.12* | .15** | .08 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 20. MFQ-Binding | 4.26 (.46) | 1 | .11* | .01 | .44** | .10 | .03 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 21. Sex | - | 1 | .01 | .09 | .18** | .06 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 22. Age | 22.47 (5.95) | 1 | .03 | -.06 | -.12* | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 23. Ideol. Orient. | 4.78 (1.87) | 1 | -.05 | -.11* | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 Covid-19 Fear | 2.03 (.88) | 1 | .48** | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25. Health Anx. | 1.70 (.74) | 1 |

Notes. ** p < .01, * p < .05

In the main study, participants evaluated the wrongness of our final vignettes set on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = not at all wrong to 5 = very wrong. This study had a within-subject design. To combat sequence effect, during the scenario writing process, we refrained from using same wording or transgressions across different health threat conditions within the same foundation set. However, eventually, our Type A, B, and C scenarios in each set were remarkably similar to one other except for the degree of health threat. In further eliminating carry-over effect, prior to the study, we intentionally mixed our scenarios by ensuring that consecutive scenarios were not different versions of the same scenario sets and did not represent the same moral foundation content. Additionally, most successive scenarios also differed from one other in terms of the degree of health threat. We gave them to participants in this fixed order. Since each moral foundation was represented by two vignettes, we calculated the mean of the wrongness ratings of two scenarios for each foundation at three levels of health threat and attained 18 different wrongness ratings for the main analysis.

Moral Foundations Questionnaire

The thirty-item MFQ (Graham et al., 2009, b; Graham et al., 2011; Yilmaz et al., 2016), and Life-Style Liberty scale (Iyer et al., 2012; Yalçındağ, 2015) were used for two reasons: (a) to check the construct validity of the newly-developed vignettes, and (b) to evaluate participants’ chronic moral priorities. Both of these scales are composed of two parts. In the first part, there are items about the moral relevance of certain criteria in deciding whether something is right or wrong (e.g., “Whether or not someone did something to betray his or her group”). Items in this part were assessed via a 6-point scale, ranging from 0 = not at all related to 5 = very much related. The second part consists of certain statements about each moral foundation (e.g., “Chastity is an important and valuable virtue”); those items were assessed through a 6-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). In the current sample, the Cronbach’s alpha was .55 for Care, .46 for Fairness, .70 for Loyalty, .78 for Authority, .80 for Purity, and .66. for Liberty. We did not delete any items on the basis of relatively lower estimates of internal consistency since Graham et al. (2011) gave priority to content broadness over reliability in their scale development approach. MFQ-individuating morality scores (α = .70) were computed by summing and taking the mean of the care and fairness subscales, and MFQ-binding morality scores (α = .89) were computed by summing and taking the mean of loyalty, authority, and purity scores. Higher scores indicated greater adoption of the related moral foundation.

Health Anxiety Measure

We suspected that participants’ health anxiety might be impactful on their evaluations of moral violations due to the epidemic. Inspired from Ferguson and Daniel (1995), Kellner (1986), and Sirri et al. (2008), a translated set of 14 health anxiety questions were prepared by the researchers. Participants reacted to those questions (e.g., Are you worried that you may get a serious illness in the future?) on a scale ranging between 1 = no/ never and 5 = most of the time. A principal component analysis was held on the items. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value of sampling adequacy was .93. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was also significant (χ2(91) = 2639.53, p < .001), suggesting that the dataset was suitable for factor analysis. The initial solution yielded two-factors. However, all three items in the second factor loaded onto the first factor with item loadings above .40. Consequently, we decided to remove them in the calculation of total health anxiety scores. The remaining 11 items explained 50.64% of the variance. Item loadings ranged between .59 and .78. (α = .90). Increasing scores on this scale indicated higher levels of health anxiety.

Fear of COVID-19 Infection

Since perceiving oneself as vulnerable to infectious diseases was impactful on people’s moral evaluations (e.g., Duncan et al., 2009), we decided to measure the fear of contracting COVID-19 as another control variable. Accordingly, we came up with four questions evaluating participants’ fear of COVID-19 (e.g., Are you worried about your own health because of the coronavirus epidemic?). Responses were rated through 5-point Likert scales, ranging from 0 = No to 4 = Very much. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin’s value of sampling adequacy was .80, which is “meritorious” according to Kaiser (1974). Bartlett’s test of sphericity was also significant (χ2(6) = 723.89, p < .001). A principal component factor analysis on these items revealed a single factor, accounting for 68.64% of the variance, item loadings ranging between .68 and .89. A mean COVID-19 fear score (α = .84) was calculated; increasing scores indicated greater fear of COVID-19 infection.

Procedure

A national institutional ethics approval was obtained before data collection. Participants’ informed consent was taken online. Participants firstly evaluated the wrongness of 36 moral violation vignettes. Next, they were given MFQ, which was followed by the health anxiety measure, fear of COVID-19 questions, and demographics form. Completing the battery of tests took participants approximately 20 min. As an incentive, student participants were given extra course credits for their participation.

Results

Descriptive statistics concerning the study variables are presented in Table 3. To test our first and second hypotheses, a 3 (Health Threat: COVID-19 health threat, non-COVID-19 health threat, & no health threat) X 6 (Moral Foundations: Care, Fairness, Liberty, Loyalty, Authority, & Purity) two-way repeated measures ANCOVA was held by controlling for participants’ age, sex, COVID-19 fear, ideology, and health anxiety. The results revealed the main effects of the health threat (F(1.82, 711.72) = 60.09, p < .001, partial eta-squared = .13), and of moral foundations (F(3.85, 1500.71) = 40.89, p < .001, partial eta-squared = .09). However, those main effects were shaped by a significant interaction effect, F(9.01, 3513.82) = 13.31, p < .001, eta2 = .03. Simple effects analyses were run to understand the nature of this interaction effect.

We firstly compared the wrongness ratings of the scenarios involving different levels of health threat within each moral foundation. For care, authority, liberty, and purity violations, Type A and Type B scenarios were seen as more acceptable than Type C scenarios while Type A scenarios were also evaluated as more acceptable than Type B scenarios. For fairness violations, Type A and Type B scenarios were rated equally more wrong than Type C scenarios. In terms of loyalty violations, participants rated Type B scenarios as more acceptable than Type A scenarios. However, both types of scenarios were rated as more acceptable than Type C scenarios. All of the p-values concerning the significant differences between the scenarios were smaller than .001. Except for fairness violations, these findings appeared to support our first hypothesis (H1).

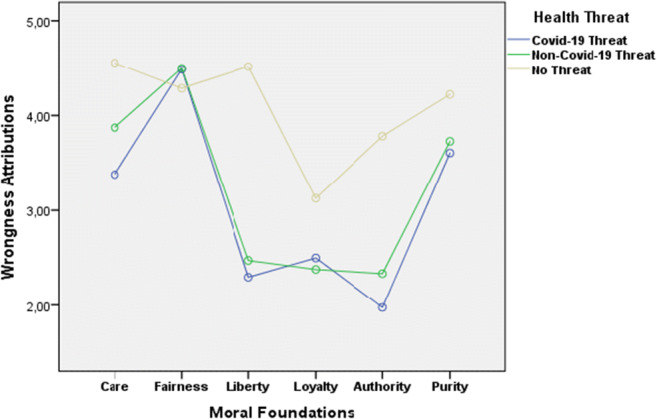

We conducted another simple effects analysis by changing the focus of comparison. This time we compared the wrongness ratings of vignettes concerning different moral foundations within different health threat conditions. In the face of a COVID-19 threat (for Type A scenarios), authority violations were seen as the most acceptable ones; the wrongness ratings of the violations could be ranked as follows: Authority < Liberty < Loyalty < Purity < Care < Fairness. In case of violations committed due to a non-COVID-19 threat (for Type B scenarios), authority, loyalty, and liberty violations were seen as equally acceptable than were purity, care, and fairness violations (Authority = Liberty = Loyalty < Purity = Care < Fairness). Concerning Type C scenarios, the wrongness rankings of those violations were as follows: Loyalty < Authority < Purity = Fairness < Liberty = Care. Almost all p-values concerning the significant differences between the scenarios were smaller than .001 (see Fig. 1 for the change patterns). These findings also supported our second hypothesis (H2) given the fact that participants’ sensitivity to fairness, care, and purity violations was high in various health threat contexts.

Fig. 1.

Wrongness attributions concerning the violations of different moral foundations at varying degrees of health threat

To determine whether participants’ wrongness attributions changed as a function of their chronic moral foundations, we conducted 18 different 2-step hierarchical regression analyses with the inclusion of control variables in the first step, and MFQ-individuating and MFQ-binding scores in the second step. Regression weights concerning the wrongness ratings of the Type A, Type B, and Type C vignettes are summarized in Tables 4, 5, and 6, respectively.

Table 4.

Summary of hierarchical regression analyses for variables predicting the wrongness ratings of Type A scenarios

| Wrongness Ratings of Type A Scenarios | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care violations | Fairness violations | Liberty violations | Loyalty violations | Authority violations | Purity violations | |||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| 1st step predictors | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | .25 | .11 | .12* | .14 | .08 | .09† | .19 | .11 | .09† | .01 | .11 | .00 | .11 | .10 | .05 | .22 | .12 | .08† |

| Age | .01 | .01 | .05 | .01 | .01 | .06 | −.01 | .01 | −.07 | .02 | .01 | .13** | .01 | .01 | .09 | −.00 | .01 | .00 |

| Ideological Orient. | .00 | .03 | .01 | .03 | .02 | .08 | .04 | .03 | .09 | −.02 | .03 | −.04 | .05 | .02 | .11 | .04 | .03 | .06 |

| Fear of Covid-19 | −.11 | .06 | −.11† | −.03 | .04 | −.04 | −.18 | .06 | −.18** | .04 | .06 | .04 | −.11 | .05 | −.12 | .03 | .06 | .02 |

| Health Anxiety | −.07 | .07 | −.06 | −.06 | .05 | −.07 | −.09 | .06 | −.08 | .02 | .07 | .01 | .07 | .06 | .07 | .07 | .07 | .04 |

| 2nd step predictors | ||||||||||||||||||

| MFQ-Individuating | .01 | .10 | .01 | .25 | .07 | .19*** | −.10 | .10 | −.06 | −.13 | .10 | −.07 | −.40 | .09 | −.24*** | −.09 | .11 | −.04 |

| MFQ-Binding | .05 | .06 | .05 | −.08 | .04 | −.11† | .00 | .06 | .00 | .44 | .06 | .40*** | .23 | .05 | .24*** | .74 | .06 | .54*** |

| R2 (Last Step) | .04* | .06** | .08*** | .17*** | .15*** | .34*** | ||||||||||||

| ΔR2 | .00 | .03** | .00 | .12*** | .07*** | .22*** | ||||||||||||

Notes. † p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Table 5.

Summary of hierarchical regression analyses for variables predicting the wrongness ratings of Type B scenarios

| Wrongness Ratings of Type B Scenarios | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care violations | Fairness violations | Liberty violations | Loyalty violations | Authority violations | Purity violations | |||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| 1st step predictors | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | .16 | .10 | .08 | .04 | .08 | .03 | .14 | .10 | .07 | .06 | .11 | .03 | .17 | .11 | .08 | .26 | .12 | .09* |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | −.08 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .02 | .01 | .14** | .01 | .01 | .09* | .00 | .01 | −.00 | −.00 | .01 | −.00 |

| Ideological Orient. | −.00 | .02 | −.00 | .03 | .02 | .10† | −.03 | .02 | −.06 | .03 | .03 | .06 | .06 | .02 | .13* | .06 | .03 | .10* |

| Fear of Covid-19 | −.02 | .05 | −.02 | −.03 | .04 | −.05 | −.01 | .05 | −.01 | .11 | .06 | .10† | −.00 | .05 | −.00 | .02 | .06 | .02 |

| Health Anxiety | .00 | .06 | .00 | −.02 | .04 | −.02 | −.06 | .06 | −.06 | .07 | .06 | .06 | .05 | .06 | .05 | .02 | .07 | .01 |

| 2nd step predictors | ||||||||||||||||||

| MFQ-Individuating | .02 | .09 | .01 | .29 | .07 | .23*** | −.26 | .09 | −.15** | −.12 | .10 | −.06 | −.33 | .10 | −.18** | −.08 | .10 | −.03 |

| MFQ-Binding | −.06 | .05 | −.06 | −.07 | .04 | −.10† | −.03 | .06 | −.03 | .39 | .06 | .36*** | .21 | .06 | .20*** | .77 | .06 | .58*** |

| R2 (Last Step) | .02 | .06** | .05** | .18*** | .11*** | .41*** | ||||||||||||

| ΔR2 | .00 | .05*** | .03* | .09*** | .05*** | .25*** | ||||||||||||

Notes. † p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Table 6.

Summary of hierarchical regression analyses for variables predicting the wrongness ratings of Type C scenarios

| Wrongness Ratings of Type C Scenarios | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care violations | Fairness violations | Liberty violations | Loyalty violations | Authority violations | Purity violations | |||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| 1st step predictors | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | .08 | .07 | .06 | .06 | .08 | .04 | .42 | .08 | .23*** | .06 | .11 | .03 | .21 | .09 | .11* | .05 | .10 | .02 |

| Age | .01 | .01 | .06 | .00 | .00 | .04 | −.01 | .00 | −.07 | .01 | .01 | .06 | −.00 | .01 | −.03 | −.00 | .01 | −.03 |

| Ideological Orient. | .02 | .02 | .08 | .03 | .02 | .10† | −.01 | .02 | −.23** | .07 | .03 | .15** | .04 | .02 | .11† | .04 | .02 | .09 |

| Fear of Covid-19 | .00 | .04 | .00 | −.00 | .04 | −.00 | .16 | .04 | .20*** | .05 | .06 | .05 | −.01 | .05 | −.02 | .09 | .05 | .09† |

| Health Anxiety | −.04 | .04 | −.06 | −.10 | .05 | −.11* | −.15 | .05 | −.15** | .01 | .06 | .01 | −.04 | .06 | −.04 | .02 | .06 | .02 |

| 2nd step predictors | ||||||||||||||||||

| MFQ-Individuating | .16 | .06 | .14* | .18 | .07 | .13* | .25 | .07 | .16*** | .12 | .10 | .06 | .06 | .08 | .04 | −.04 | .09 | −.02 |

| MFQ-Binding | −.06 | .04 | −.10† | .02 | .04 | .02 | −.23 | .04 | −.26*** | .41 | .06 | .36*** | .19 | .05 | .21*** | .55 | .06 | .49*** |

| R2 (Last Step) | .04* | .05** | .28*** | .22*** | .10*** | .30*** | ||||||||||||

| ΔR2 | .02* | .02* | .06*** | .11*** | .04*** | .18*** | ||||||||||||

Notes. † p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

MFQ-binding morality scores positively predicted participants’ ratings of binding morality vignettes (i.e., Loyalty, Authority, & Purity) not only for Type C scenarios, but also for Type A and Type B scenarios. In other words, participants’ MFQ-binding morality scores were associated with the evaluations of binding morality vignettes, independent of the degree of health threat in scenarios. This persistent association between MFQ-binding scores and the wrongness ratings of binding morality violations across differing health threat levels provides support for our third hypothesis (H3a).

The results yielded mixed evidence for our hypothesis regarding the role of MFQ-individuating morality scores in predicting the wrongness ratings of individuating morality vignettes (H3b). MFQ-individuating morality scores positively predicted the wrongness ratings of Type C care and fairness violations. However, even though MFQ-individuating morality scores lost their power in predicting the evaluations of care violations in the face of health threat salience, participants’ chronic preference for individuating morality was still predictive of their evaluations of fairness violations in health threat contexts. Accordingly, we can conclude that H3b seemed to be supported for care foundation, but not for fairness foundation.

Discussion

The current study had three basic aims. First, we questioned whether people’s wrongness attributions of moral foundation transgressions would change according to the degree of the health threat. Second, we examined what particular types of moral foundations would gain importance in health threatening contexts (including the COVID-19 pandemic). Third, we addressed whether chronic moral foundations preserved or lost their power in predicting the wrongness ratings of vignettes at different levels of health threat.

The results supported our first hypothesis (H1) which suggested a positive link between the acceptability of moral violations and their degree of health threat. Except for the fairness foundation, participants rated the moral foundation vignettes more acceptable if the transgressors committed them for a health concern. However, fairness violations were evaluated as less acceptable as the degree of health threat increased. In contrast to our fairness-related finding, a recent study examining how COVID-19 pandemic changes people’s fairness views (more specifically inequality acceptance) revealed that the current pandemic has increased public acceptance of social inequality (Cappelen et al., 2020). This disagreement between the study findings might be due to the differences in the nature of dependent variables. Cappelen et al. (2020) used a more abstract notion of inequality acceptance as an outcome measure. More specifically, after manipulating the salience of a COVID-19 threat, they asked respondents to rate whether or not “it is unfair if luck determines people’s economic situation”. However, we asked our respondents to rate the wrongness of fairness transgressions under different threat conditions.

Our fairness vignettes relate to the allocation of medical resources such as masks and COVID-19 tests. Compared to other moral foundations, the wrongness or rightness of fairness violations is more likely to be evaluated in terms of its outcomes (Wheeler & Laham, 2016). Regarding data collection time, the probable consequences of fairness violations such as health care inequalities or mask storage might be highly salient for the present participants. Since the prevalence of such inequalities hinders equal chances of survival for everybody in the community during an epidemic, the authorities are expected to ensure equal treatment in allocating scarce medical sources (Emanuel et al., 2020). Thus, this expectation might be the reason why people’s sensitivity to fairness violations seemed to increase as a function of health threat in the current study.

In supporting our second hypothesis (H2), the results also showed that participants endorsed care, fairness, and purity foundations more than the remaining foundations in the face of a disease threat. The mean wrongness ratings for violations of those foundations were remarkably close to the upper ends of 5-point Likert scales across varying degrees of a health threat. In the present study, participants were forced to choose between maintaining moral principles and avoiding an immediate health threat. The results revealed that people were reluctant to sacrifice fairness, care, and purity foundations even for pathogen avoidance. This reluctance might underline the possibility that those foundations themselves play a role in regulating social life in health threatening contexts (including the global COVID-19 crisis). In contrast, even though the current participants were extremely sensitive to liberty violations (given the fact that liberty violations were seen as the most egregious violations among Type C scenarios), they started to see such violations as one of the least important transgressions in health threatening contexts. This result might be associated with the moralization of COVID-19 restrictions such as lockdowns (Francis & McNabb, 2020). To control the outbreak of COVID-19 disease, many governments have launched specific interventions that violate the conceptions of liberty and rights. A moralization of these restrictions has “led people in many countries to accept – even to embrace – a level of surveillance and restriction on their personal freedom that might ordinarily lead to fury” (Stott & Radburn, 2020, p. 93). Yet, with the data at hand, we do not know how people justify or emotionally react to those contextualized moral foundation violations. Further studies could address how the kinds of contextual justifications or emotional reactions change as a function of moral foundations so as to better understand the context-dependent moral reasoning.

Participants’ personal preference for binding morality predicted their evaluations of binding morality violations across different levels of health threat. This finding seemed to provide evidence for the first part of third hypothesis (H3a) which offered a consistent association between chronic binding morality and contextual binding sensitivities. Yet, we cannot surely explain whether cross-situational consistency in conservatives’ moral judgments is caused by their reduced concern about COVID-19 threat or by their chronic sensitivity to threats (Nail et al., 2009). The current descriptive data suggests that fear of COVID-19 infection was not associated with participants’ MFQ-binding scores. Accordingly, we can say that more conservative participants in the present study do not seem to experience less fear of COVID-19 than less conservative people do. However, a number of US studies (e.g., Calvillo et al., 2020; Conway et al., 2020) demonstrate that a negative association existed between conservatism and a perceived COVID-19 threat. In contrast, the conservative German participants were found to experience greater fear of COVID-19 than their liberal counterparts did (Lippold et al., 2020). These contrasting findings call for further studies which directly question and compare the link between ideology and reactions to disease outbreaks in countries which have different policy responses to the Coronavirus pandemic (ILO, 2020).

The current results yielded partial support for the second part of our third hypothesis (H3b) which suggested an inconsistent association between chronic individuating morality preferences and reactions to individuating morality transgressions. The descriptive data suggests that participants’ MFQ-individuating morality scores and fear of COVID-19 infection were positively correlated. Accordingly, people who chronically prioritize individuating morality might experience a dissonance when choosing between their moral priorities and avoiding disease in health threatening contexts. This prediction seemed to be true for care violations as the link between chronic individuating morality and moral judgments lost its significance in disease-salient vignettes. However, such a pattern was not observed for fairness violations. In other words, participants’ chronic individuating morality scores were predictive of their reactions to fairness violations independent of the degree of health threat in the scenarios. This outcome might also be associated with the salience of negative outcomes of fairness violations in the data collection time of the present study.

The present study should be evaluated with its shortcomings as well. Even though we tried to ensure that health threatening scenarios and context-free scenarios were differentiated from each other in terms of the degree of health threat, some of our scenarios (e.g., purity-1 set) did not meet this criterion. Additionally, we expected to find a significant association between the evaluations of context-free (Type C) scenarios and the scores of the related MFQ-dimensions. This criterion was met for binding morality vignettes. However, the individuating morality vignettes and the related MFQ-dimensions only barely correlated. Relatedly, our moral violation vignettes need further validation in confirming their moral foundations. In addition, we did not address how people’s moral judgments are associated with their real-world behaviors during a pandemic. Future studies could compare the impact of chronic moral preferences and context-dependent judgments in adhering to COVID-19 mitigating practices.

Furthermore, we utilized within-subject design to examine the impact of the (COVID-19) health threat on moral decision making. Despite its drawbacks (especially the sequence effect), we preferred within-subject design due to its superiority over between-subject design in eliminating variance that is caused by difference between subjects (Goodwin, 2010). What is more, this design better allowed us to simultaneously test our three hypotheses. To minimize the sequence effect in our study, we took certain precautions. For example, we did not give those scenarios to participants in a random order since different versions of the same scenario set or the scenarios representing the same moral foundation might coincidentally come one after the other. Additionally, we preferred not to use the same wording or transgressions across different health threat conditions within the same foundation set. Furthermore, the times of COVID-19 pandemic have their own dynamics, community practices, and peculiar forms of moral transgressions. It is difficult (if not impossible) to construct vignettes by using the same wording across different health threat conditions because some of the moral violations committed to avoid the COVID-19 disease might become meaningless in other health threat contexts. For example, for a probable Type B version of the fairness-2 set, it would be somehow pointless to store masks for avoiding a cold. However, for its Type A version, mask storage was a very hot issue; even governments restricted the purchase and sale of masks at the beginning of the pandemic. As a result, we came up with a different case of stockpiling (i.e., flu medicine) for the Type B version of this set. However, this strategy (i.e., changing the wording or content of the scenarios of the same set) by itself might have caused extra variance between the scenarios in addition to the variance caused by our health threat manipulation. In testing similar questions, further studies could adopt between-subject design which allows designing vignettes with equivalent wording across different health threat conditions.

Last but not least, in consideration of the fact that certain symbols such as the church, cross, holy books, and flags might become sacralized (Haidt, 2013), we treated disrespect for a flag as a form of a purity violation. However, the stories relating to destroying a flag were typically used to depict a loyalty violation (e.g., Graham et al., 2009). Yet, other studies revealed that reactions to flag burning were equally associated with purity and loyalty foundations (e.g., Koleva et al., 2012). On the other hand, Tepe et al. (2016) found that Turkish participants employed the ethics of divinity more frequently than other ethical codes (such as autonomy and community) in justifying their moral decisions about flag desecration. As a result, considering disrespecting a flag as a purity violation in the Turkish context might not pose a crucial validity threat to our findings. Even when we analyzed our two types of purity vignettes separately with relation to the remaining variables, our findings remained unchanged (see the Supplementary Material for the statistical details).

In general, the current study findings imply the critical role of context in moral decision making. Even though people have chronic moral preferences, their personal qualities interact with contextual cues in the process of moral decision making (Giammarco, 2016). In health threatening contexts, people make an implicit cost-benefit analysis between the costs of adherence to disease avoiding behaviors (i.e., violation of pre-existing moral preferences) and their disease-specific benefits (i.e., reduced risk of being infected). From a theoretical perspective, we can say that the current findings are unique in explaining the link between chronic moral orientations and real-life moral judgments. From an applied perspective, we can state that certain moral foundations such as fairness, care, and purity give shape to social life more than other foundations during a health crisis. With this premise in mind, policy makers should consider adopting/accommodating those foundations in the moral content of their messages to regulate social behavior during a health crisis. Such messages might be more powerful for creating social change and are more easily and widely accepted in the community.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 70 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [E.Y.].

Author Contributions

All authors contributed significantly. They agree with the content of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Social and Humanity Sciences Ethical Board of İzmir Katip Çelebi University, İzmir, Turkey. The research reported in the manuscript was conducted following general ethical guidelines in psychology.

Footnotes

Originality

This manuscript has not been published in any language before and has not being considered concurrently for publication elsewhere.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hatice Ekici, Email: haticeozen11@gmail.com.

Emine Yücel, Email: ey.emineyucel@gmail.com.

Sevim Cesur, Email: cesur@istanbul.edu.tr.

References

- Alper S, Bayrak F, Öykü Us E, Yılmaz O. Do changes in threat salience predict the moral content of sermons? The case of Friday Khutbas in Turkey. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2019;50(3):662–672. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, R., Romero-Kornblum, H., Young, J. C., You, M., Kramer, J. H., & Chiong, W. (2020). No utilitarians in a pandemic? Shifts in moral reasoning during the COVID-19 global health crisis. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/yjn3u

- Araque O, Gatti L, Kalimeri K. Moral strength: Exploiting a moral lexicon and embedding similarity for moral foundations prediction. ArXiv. 2019;191:105184. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2019.105184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardila-Rey A, Killen M, Brenick A. Moral reasoning in violent contexts: Displaced and non-displaced Colombian children’s evaluations of moral transgressions, retaliation, and reconciliation. Social Development. 2009;18(1):181–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettache K, Hamamura T, Idrissi JB, Amenyogbo RGJ, Chiu C. Monitoring moral virtue: When the moral transgressions of in-group members are judged more severely. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2018;50(2):268–284. doi: 10.1177/0022022118814687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Jost JT. Conservative shift among high-exposure survivors of the September 11th terrorist attacks. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2006;28(4):311–323. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp2804_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RC. Resisting moralisation in health promotion. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice. 2018;21(4):997–1011. doi: 10.1007/s10677-018-9941-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo DP, Ross BJ, Garcia RJB, Smelter TJ, Rutchick AM. Political ideology predicts perceptions of threat of COVID-19 (and susceptibility to fake news about it) Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2020;11(8):1119–1128. doi: 10.1177/1948550620940539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelen, A. W., Falch, R., Sørensen, E. Ø., & Tungodden, B. (2020). Solidarity and fairness in times of crisis. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.3600806 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Clifford S, Iyengar V, Cabeza R, Sinnott-Armstrong W. Moral foundations vignettes: A standardized stimulus database of scenarios based on moral foundations theory. Behavior Research Methods. 2015;47(4):1178–1198. doi: 10.3758/s13428-014-0551-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway, L., Woodard, S., Zubrod, A., & Chan, L. (2020). Why are conservatives less concerned about the coronavirus (COVID-19) than liberals? Testing experiential versus political explanations. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/fgb84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Diaz, R., & Cova, F. (2020). Moral values and trait pathogen disgust predict compliance with official recommendations regarding COVID-19 pandemic in US samples. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/5zrqx

- Duncan LA, Schaller M, Park JH. Perceived vulnerability to disease: Development and validation of a 15-item self-report instrument. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47(6):541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ekici, H. (2019). Politik şiddet deneyimi ve ahlaki temeller kuramı: Politik şiddete maruz kalan Suriyeli ergenler ile politik şiddet deneyimi yaşamayan Türk ergenlerin ahlaki temellerinin incelenmesi (exposure to political violence and moral foundations theory: The investigation of moral foundations of Syrian adolescents who has been exposed to war and Turkish adolescents who has no experience of war) [dissertation thesis, Istanbul University]. Turkish National Thesis Center.

- Ellemers N, van den Bos K. Morality in groups: On the social-regulatory functions of right and wrong. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2012;6(12):878–889. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2013.841490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers N, Pagliaro S, Barreto M. Morality and behavioural regulation in groups: A social identity approach. European Review of Social Psychology. 2013;24(1):160–193. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, Zhang C, Boyle C, Smith MJ, Phillips JP. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(21):2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrega H. Earliest phases in the evolution of sickness and healing. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1997;11(1):26–55. doi: 10.1525/maq.1997.11.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson E, Daniel E. The illness attitudes scale (IAS): A psychometric evaluation on a non-clinical population. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995;18(4):463–469. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)00186-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]