Abstract

BACKGROUND

Alternative splicing (AS) increases the diversity of mRNA during transcription; it might play a role in alteration of the immune microenvironment, which could influence the development of immunotherapeutic strategies against cancer.

AIM

To obtain the transcriptomic and clinical features and AS events in stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD) from the database. The overall survival data associated with AS events were used to construct a signature prognostic model for STAD.

METHODS

Differentially expressed immune-related genes were identified between subtypes on the basis of the prognostic model. In STAD, 2042 overall-survival-related AS events were significantly enriched in various pathways and influenced several cellular functions. Furthermore, the network of splicing factors and overall-survival-associated AS events indicated potential regulatory mechanisms underlying the AS events in STAD.

RESULTS

An eleven-AS-signature prognostic model (CD44|14986|ES, PPHLN1|21214|AT, RASSF4|11351|ES, KIAA1147|82046|AP, PPP2R5D|76200|ES, LOH12CR1|20507|ES, CDKN3|27569|AP, UBA52|48486|AD, CADPS|65499|AT, SRSF7| 53276|RI, and WEE1|14328|AP) was constructed and significantly related to STAD overall survival, immune cells, and cancer-related pathways. The differentially expressed immune-related genes between the high- and low-risk score groups were significantly enriched in cancer-related pathways.

CONCLUSION

This study provided an AS-related prognostic model, potential mechanisms for AS, and alterations in the immune microenvironment (immune cells, genes, and pathways) for future research in STAD.

Keywords: Stomach adenocarcinoma, Alternative splicing, Tumor microenvironment, Immune-related genes and pathways

Core Tip: In this study, we performed a systematic analysis of prognostic splicing events in stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), constructed an elevated Alternative splicing (AS)-signature prognostic model, and explored the association between AS and cancer immunity. The final overall survival-related AS events, differentially expressed immune-related genes, and the enriched pathways may play an important role in tumorigenesis in STAD; they deserve further study in clinical applications as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

INTRODUCTION

Stomach cancer is a multifactorial cancer with a relatively high mortality (the third leading cause of death) worldwide. Each year, approximately one million new cases are reported, and the disease kills approximately 700000 men annually[1]. Around 90%-95% of all stomach cancers are stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), which develops from cells that form in the mucosa[2]. Despite progress in surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, improvement in survival remains a major challenge in STAD therapy[3]. Several patients with early-stage gastric cancer are misdiagnosed with chronic gastritis or gastric ulcers owing to insidious clinical characteristics related to early-stage symptoms. Most gastric cancer patients lose the chance to undergo radical surgery, which decreases the 5-year survival rate in STAD[4]. Moreover, gastric cancer tends to lead to local infiltration and distant metastasis, spreading from the stomach to other organs of the body, especially the liver, peripheral vascular system, lungs, bones, supraclavicular lymph nodes, lining of the abdomen, and lymph nodes[5]. In patients with advanced stages of STAD, development of novel effective biomarkers and exploration of the most reliable mechanism for predicting the development and progression would be beneficial for improving the accuracy and specificity of disease prevention, risk prediction, and favorable STAD prognosis[6].

Alternative splicing (AS) increases the diversity of mRNA during transcription, which indicates that a single gene could code multiple proteins. A total of 20000 protein-coding genes might generate a mass of variants, even more than we expected in the traditional way of thinking[7]. Abundant AS production has broad implications for complex biological processes. AS occurs as a normal and common phenomenon in humans. Traditional classification of AS modes includes exon skip (ES), alternate promoters (AP), alternate terminators (AT), alternate acceptors (AA), alternate donors (AD), retained introns (RI), and exclusive exons (ME)[8]. The relative frequencies of the AS modes vary among humans; moreover, new AS events have been consistently identified using high-throughput techniques[9]. Abnormal AS events are frequently implicated in genetic disorders that result in human diseases, particularly, tumorigenesis and cancer progression. A comparison of cancerous and normal cells through combined RNA-Seq and proteomics analyses indicated significantly different expressions or types of splice events for key proteins in cancer-associated pathways [10]. For instance, cancerous cells exhibit higher levels of RI and lower levels of ES compared with normal cells[11]. Changes in trans-acting splicing factors (SFs) are general splicing mechanisms, including posttranslational modification, chromatin structure and histone modifications[12], DNA methylation[13], and gene mutation. The remarkable developments in immunotherapy strategies against STAD have yielded good results and almost changed the landscape of STAD treatment. The immune checkpoint molecules programmed death-1 (PD-1) and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), that focus on the role of T cells and associated co-inhibitory signals, hamper the immune escape of tumor cells[14]. Through clinical trials, researchers have evaluated the safety and efficacy of novel immunotherapies that target new immune checkpoint molecules, such as mucin domain containing-3, lymphocyte-activation gene 3, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and T cell immunoglobulin[15]. In a previous study, immunotherapeutically relevant gene signatures were constructed on the basis of tumor microenvironment characterization in gastric cancer; they have great potential for improving STAD patient outcome[16]. Researchers have observed that new antigens generated through AS mechanisms are common in most cancer patients; these new antigens may serve as potential therapeutic targets for patients with low tumor mutation burden[17]. Studies have demonstrated that the tumor microenvironment profile undergoes specific changes that are induced by SFs[18]. AS-influenced immune processes have captured great attention, including the B cell receptor signaling pathway, T cell receptor signaling pathway, antigen processing and presentation pathways, interleukins and interleukin receptors, chemokines and chemokine receptors, natural killer cell cytotoxicity, transforming growth factor (TGF) family members and TGF family member receptors, and interferons and interferon receptors[19]. Survival-associated AS events interact with the immune microenvironment and could influence the development of immunotherapeutic strategies against STAD.

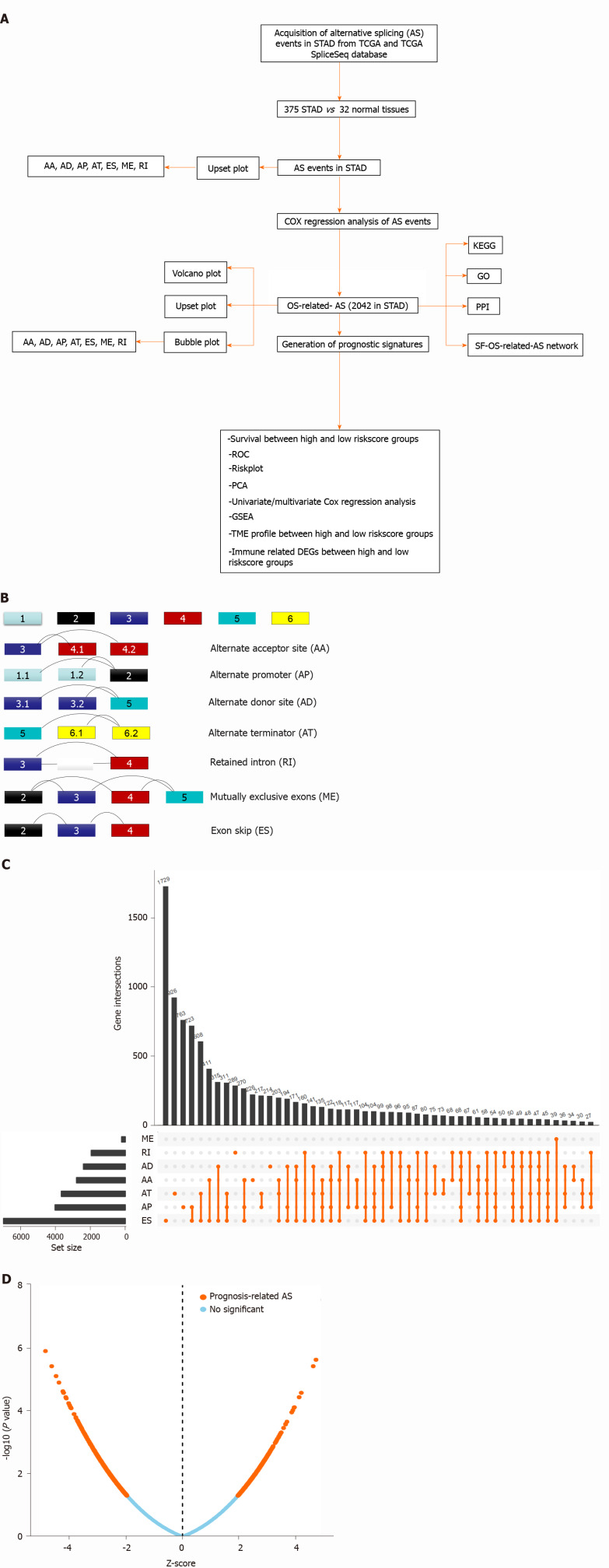

Here, AS signatures were systematically analyzed on the basis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database for elucidating the survival-associated AS event profile, cancer-related pathways of AS genes, and potential mechanisms of SF-AS interactions in STAD. The overall survival (OS)-related AS signature prognostic model-based high and low risk score groups were significantly related to STAD OS. Furthermore, the significantly different distribution of immune cells between the high- and low-risk score groups according to the AS signatures induced further exploration of the differentially expressed immune-related genes (DEIRGs) between the two groups. The enriched pathways of these DEIRGs suggested that survival-associated AS events might influence the immune microenvironment. These observations need further experimental verification and clinical research for the development of clinical applications utilizing the identified AS-associated biomarkers and immune-related genes (IRGs). A flow chart of the study is presented in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Overview of alternative splicing events profiling in stomach adenocarcinoma. A: The flow chart for identification of overall survival (OS)-related alternative splicing (AS) signatures in stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD); B: Schematic diagram of seven splicing modes; C: UpSet plot of different types of AS events in STAD; D: Volcano plot of OS-related AS events in STAD. Upregulated OS-related AS events are indicated by red points and downregulated OS-related AS events by green points. TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GO: Gene Ontology; PPI: Protein-protein interaction; ES: Exon skip; AP: Alternate promoters; AT: Alternate terminators; AA: Alternate acceptors; AD: Alternate donors; RI: Retained introns; ME: Exclusive exons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection in STAD

The RNA transcriptome (level 3) profiles and corresponding clinical variables (including age, sex, pathologic stage, pathologic T, pathologic M, and pathologic N) of the STAD cohorts were downloaded from the TCGA data portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/). AS events in STAD were obtained from TCGA SpliceSeq (https://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/public-software/tcgaspliceseq/). The Percent Spliced In values, which represent the ratio between reads excluding or including exons, were used to calculate splice events, including AA, AD, AP, AT, ES, ME, and RI. Each splicing event has a unique code consisting of the gene symbol, ID number, and splicing type to ensure accuracy. In addition, an UpSet plot (https://www.rdo cumentation.org/packages/UpSetR/versions/1.4.0/topics/upset) was generated using the R package to summarize overlapping sets among the seven types (AA, AD, AT, AP, ES, ME, and RI) of AS events in STAD. IRGs were matched with the ImmPort database (https://www.immport.org/shared/home). The proportion of 22 human immune cells in STAD was evaluated with the CIBERSORT (http://cibersort.stanford.edu/) algorithm-based LM22 gene signature using 1000 permutations.

Cox regression analysis of IRG AS events in STAD

The Cox proportional hazard regression model was constructed using the survival R package (https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/survival/versions/3.2-3) to select OS-related AS events (P value < 0.05) in STAD. Additionally, we generated an UpSet plot (https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/UpSetR/versions /1.4.0/topics/upset) and bubble plot (https://www.rdocumentation.org/ggplot2/versions/3.3.2) using the R package to summarize OS-related AS event modes (AA, AD, AT, AP, ES, ME, and RI) in STAD.

Functional and pathway enrichment analyses of OS-related AS events in STAD

The identified OS-related AS event genes in STAD were input into the DAVID functional annotation bioinformatics microarray database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) to analyze the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways [P < 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05]. Gene Ontology (GO) terms analysis according to biological process (BP) was performed using Cytoscape ClueGO (two-sided hypergeometric test, adjusted P value < 0.05, corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg method). All OS-related AS events were used to construct a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network in the STRING database (https://string-db.org/), which had a combined score > 0.9 and which was confirmed through experiments.

Construction of the SF-OS-related AS network in STAD

The SF protein is involved in removing introns from strings of mRNA, following which the exons combine again; the AS process occurs in the spliceosomes. The SF gene list was matched and selected from the Splice Aid database (http://www.introni.it/splicing.html). Furthermore, the correlation between the SFs and OS-related-AS was analyzed using the Corrplot R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/vignettes/corrplot-intro.html). The network of OS-related AS events and SFs was constructed using Cytoscape on the basis of the cutoff value (correlation coefficient > 0.6 and P value < 0.05).

Lasso regression construction and verification in STAD

The OS-related AS events were selected for constructing a prognostic model in STAD with lasso regression using the glmnet R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmnet/index.html). Lasso regression achieves dimension reduction of high-dimensional data by restricting the sum of the absolute value of coefficients to be smaller than a predetermined value. As a result, variables with a relatively small contribution would be conferred a coefficient of zero. The best model was determined by maximizing model performance and minimizing the number of features (i.e., genes). Only genes with nonzero coefficients in the lasso regression model were chosen to further calculate the risk score. We computed the risk score for each patient using the following formula: Risk scores =∑j=1nCoefj × Xj, with Coefj indicating the coefficient and Xj representing the relative expression levels of each AS-related gene standardized by the z-score. The median risk score was chosen as a cutoff value to dichotomize TCGA-STAD cohorts. The STAD samples were divided into two subtypes (high-risk-score group and low-risk-score group) according to the median risk score obtained through the OS-related AS events prognostic model. We plotted the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves using the R package (https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/pROC/versions/1.16.2/topics/roc) to show the specificity and sensitivity of the risk score for predicting prognosis in STAD. The Kaplan-Meier curve was used to evaluate the relevance of the OS between the risk score groups. Additionally, univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to analyze the association between OS and clinical characteristics of STAD, including age, sex, pathologic stage, pathologic T, pathologic M, pathologic N, and risk score. Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (version 4.1.0) was used to identify different gene sets in the high-risk-score group and low-risk-score group using 1000 permutations (P value < 0.05 and FDR Q value < 0.05, as calculated using the Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing).

Identification of different immune cells and DEIRGs between high- and low-risk-score groups in STAD

The distribution of immune cells (P value < 0.05) in STAD tissue samples was compared between the high- and low-risk-score groups on the basis of the OS-related AS prognostic model using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with the R package (https://stat.ethz.ch/R-manual/R-devel/Library/stats/html/ks.test.html). Furthermore, the correlation of different immune cells was performed using the Corrplot R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/vignettes/corrplot-intro.html). We used the Limma package (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html) to compare DEIRGs (P value < 0.05, FDR ≤ 0.05, and log(fold change) filter ≥ 0.58) between the high- and low-risk-score groups. The DEIRGs in STAD were input into the DAVID functional annotation bioinformatics microarray database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) for analyzing significant KEGG pathways (P < 0.05 and FDR < 0.05).

RESULTS

Identification of OS-related AS events in STAD

The AS event modes included seven traditional types, namely ES, AA, AT, AP, AD, ME, and RI (Figure 1B). The diagrammatic drawing of different AS event modes described different splicing locations in the pre-mRNAs. For example, the ES form is the most common splicing mode in mammalian pre-mRNAs, where an exon may be spliced out of the primary transcript or retained. In the AA mode, an alternative 3' splice junction is used to change the downstream exon 5' boundary. In the AD mode, an alternative 5' splice junction is used to change the upstream exon 3' boundary. In the ME mode, one of the two exons would be retained in the mRNAs after splicing but not both. RI is the rarest mode in mammalian pre-mRNAs, where a sequence might be spliced out as an intron or simply retained.

In total, 375 STAD patients and 32 normal tissues were included in the analysis of the AS events. The AS profile of STAD is shown in the UpSet plot (Figure 1C). A total of 48141 AS events were detected, and the original data were obtained from the TCGA SpliceSeq database (https://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/TCGASpliceSeq/). Among these AS events, 2042 OS-related AS events were identified using the Cox survival regression analysis (Figure 1D), including 157 AA, 174 AD, 297 AT, 461 AP, 805 ES, 18 ME, and 130 RI (Figure 2A). There were 569 genes that only occurred in ES; 262 genes, in AP; 178 genes, in AT; 122 genes, in AD; 118 genes, in AA; 95 genes, in RI; and 13 genes, in ME. Some genes exhibited multiple OS-related AS events; for example, four types of AS events were detected for IL32, including IL32|33378|RI, IL32|33396|AD, IL32|33397|ES, IL32|33399|ES, IL32|33402|ES, IL32|33403|ES, IL32|33406|ES, IL32|33407|ES, IL32|33412|ES, IL32|33413|ES, IL32|33426|RI, IL32|33435|AA, and IL32|33439|AD. Three types of AS events were detected for the following: ANAPC11, which included ANAPC11|44201|AP, ANAPC11|44207|ES, ANAPC11|44211|ES, ANAPC11|44214|AD, and ANAPC11|44217|ES; CARD8, which included CARD8|50711|ES, CARD8|50713|ES, CARD8|50715|ES, CARD8|50719|AD, and CARD8|50721|RI; IDS, which included IDS|90286|AP, IDS|90287|AP, IDS|90290|AT, IDS|90291|AT, and IDS|90294|ES; KIAA1217, which included KIAA1147|82046|AP, KIAA1217|10993|AP, KIAA1217|11000|RI, KIAA1217|11002|ES, KIAA1217|11003|ES, and KIAA1217|11004|ES; MIB2, which included MIB2|183|AP, MIB2|184|AP, MIB2|192|ES, MIB2|196|ES, and MIB2|198|AD; NUDT22, which included NUDT22|16584|AT, NUDT22|16587|ES, and NUDT22|16591|AD; PHRF1, which included PHRF1|13697|AA, PHRF1|13699|ES, and PHRF1|13700|AD; SRSF7, which included SRSF7|53276|RI, SRSF7|53277|RI, SRSF7|53278|AA, SRSF7|53279|RI, SRSF7|53280|RI, and SRSF7|53284|ES; and TMEM205, which included TMEM205|47656|RI, TMEM205|47657|RI, TMEM205|47665|AD, TMEM205|47673|RI, TMEM205| 47675|ES, and TMEM205|47678|AD. Some genes had multiple AS locations with the same AS events, for example, CD44 (CD44|14985|ES, CD44|14986|ES, CD44|14989|ES, CD44| 15133|ES, and CD44|15142|ES), COL1A1 (COL1A1|1058233|ES, COL1A1|1557945|ES, COL1A1|1569777|ES, COL1A1|316114|ES, COL1A1| 316125| ES, COL1A1|316133|ES, COL1A1| 409264|ES, COL1A1|941205|ES, and COL1A1|941210|ES), SRSF2 (SRSF2|43661|RI, SRSF2|43662| RI, and SRSF2| 43663|RI), and ZNF436 (ZNF436|1050|AP, ZNF436|1051|AP, ZNF439|47755|AP, and ZNF439|47756|AP). The distribution of OS-related AS events in STAD is shown in the bubble plot, including AAs, ADs, ATs, APs, ESs, ME, and RIs (Figure 2B-H). The difference in the distribution of OS-related AS events in STAD might indicate specific splicing locations in the genome and could enable the development of novel treatment strategies for STAD.

Figure 2.

Overall survival-related alternative splicing events and the distribution in stomach adenocarcinoma. A: UpSet plot of different types of overall survival (OS)-related alternative splicing (AS) events in stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD); B-H: The distribution of OS-related AS events in STAD are illustrated by the bubble plot, including exon skip, alternate promoters, alternate terminators, alternate acceptors, alternate donors, retained introns, and exclusive exons.

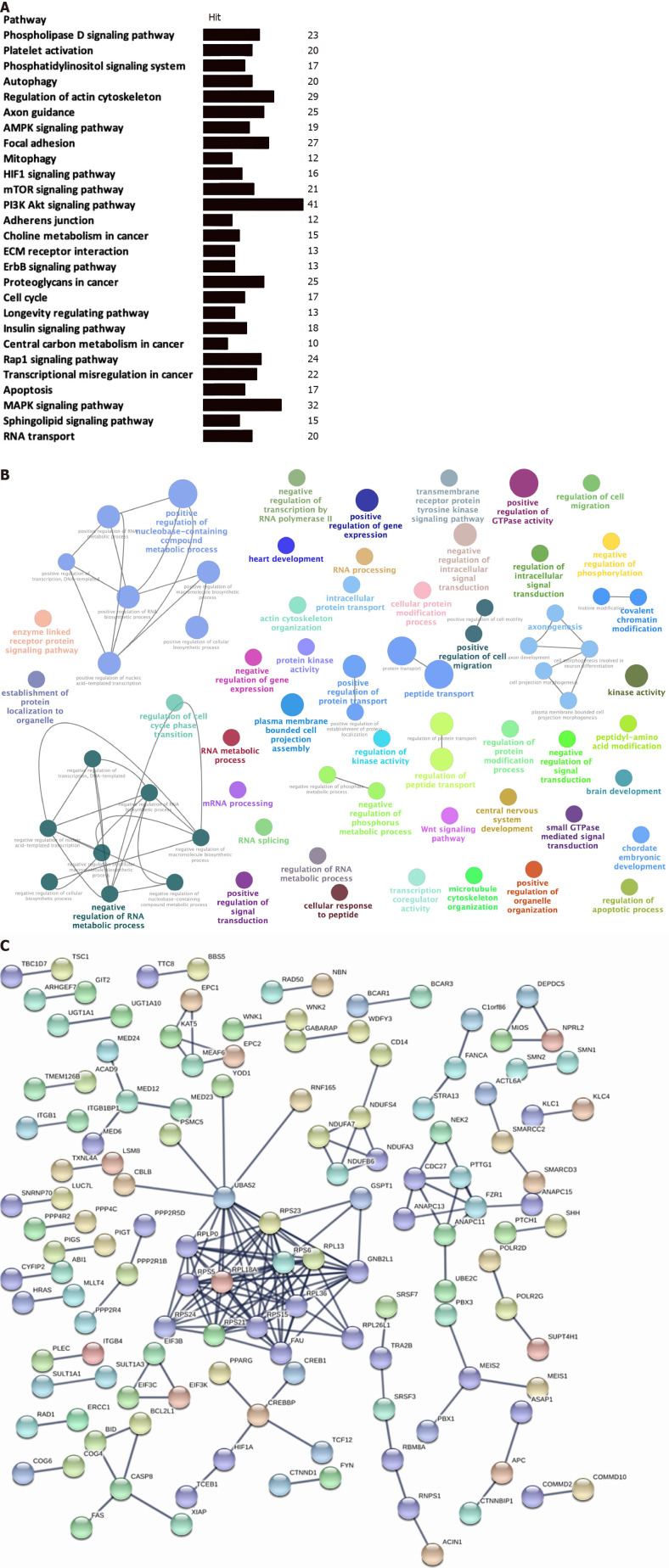

OS-related-AS genes were significantly enriched in certain cancer-related pathways and BPs in STAD

The KEGG enrichment analysis was used to analyze pathways involved in the identified OS-related-AS events. A total of 27 statistically significant KEGG pathways were enriched in STAD (Figure 3A); most of the pathways were closely associated with tumorigenesis and cancer development. Some of the OS-related-AS genes played important roles in the signaling pathways and served as hub molecules.

Figure 3.

Functional enrichment and pathway analysis of overall survival-related alternative splicing events in stomach adenocarcinoma. A: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analysis of overall survival (OS)-related alternative splicing (AS) events in stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD) (P < 0.05); B: GO enrichment analysis (biological process) of OS-related AS events in STAD. Only gene sets with natural organic matter P < 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) Q < 0.05 (adjusted P value using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the FDR) were considered significant. The lower P value and higher significant enrichment are shown with the greater node size. The same color indicated the same function group. Among the groups, we chose a representative for the most significant term and lag highlighted; C: Protein-protein interaction network of OS-related AS events in STAD.

We used the GO enrichment analysis according to BP to analyze the identified OS-related-AS genes. A total of 72 statistically significant BPs were obtained in STAD (Figure 3B), which primarily included cellular processes involved in positive and negative regulation of gene expression (positive and negative regulation of transcription, positive regulation of nucleic-acid-templated transcription), regulation of RNA metabolic processes (negative regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II, RNA processing, mRNA processing, RNA splicing, positive and negative regulation of RNA metabolic process, and positive and negative regulation of RNA biosynthetic process), regulation of metabolic processes (protein kinase activity, regulation of protein modification process, establishment of protein localization to organelles, cellular protein modification process, intracellular protein transport, enzyme-linked receptor protein signaling pathway, transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway, protein transport, regulation of protein transport, positive regulation of protein localization, kinase activity, negative regulation of phosphorylation, and positive regulation of protein transport), and regulation of intracellular signal transduction (transcription coregulator activity, Wnt signaling pathway, regulation of cell migration, regulation of apoptotic process, and regulation of cell cycle phase transition). These BP enrichments of the identified OS-related-AS genes have broad implications in STAD cells, influencing the process of DNA, RNA, protein, and related signal transductions.

The identified OS-related-AS genes were used for constructing a PPI network for STAD (Figure 3C). Stringent filter conditions were set for the PPI network, which included a combined score more than 0.9; the interactions were experimentally determined in previous studies. A total of 170 protein pairs (132 proteins) were obtained.

Key modules in the PPI network of STAD include CASP8, CREBBP, NDUFS4, CDC27, PTTG1, FZR1, ANAPC11, UBA52, RPS23, RPS6, RPL13, RPL36, GNB2L1, RPL26L1, FAU, RPS15, RPS21, RPS24, RPS5, RPLP0, and RPL18A. Several ribosome-associated proteins were present in the PPI network.

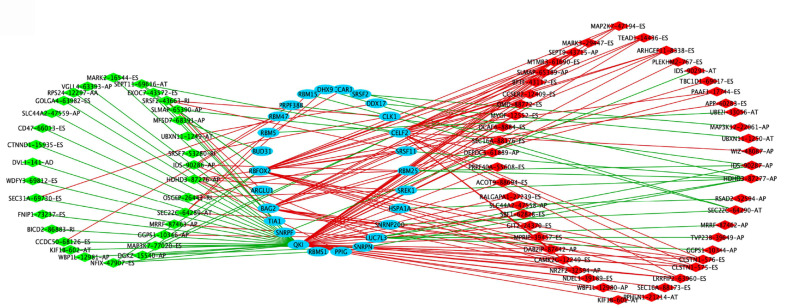

Construction of potential SF-AS regulatory network in STAD

For exploring the potential upstream regulatory mechanisms of the SFs of OS-related-AS events in STAD, the RNA expression of the SFs was extracted from the TCGA database based on the Splice Aid database in STAD. The regulatory mechanisms between SF and AS with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.6 and a P value less than 0.05 were utilized to construct the SF-AS regulatory network (Figure 4). A total of 26 SFs were included in the network, including RBM25, SREK1, HSPA1A, SNRNP200, LUC7L3, SNRPN, PPIG, RBMS1, QKI, SNRPF, BAG2, RBFOX2, BUD31, RBM5, PRPF38B, RBM15, DHX9, CCAR1, SRSF2, DDX17, CELF2, SRSF11, TIA1, ARGLU1, RBM47, and CLK1. A total of 81 AS events were included in the network, of which 33 AS events were negatively correlated with SFs and 48 AS events were positively correlated with SFs. Certain potential SF-AS pairs showed a correlation coefficient greater than 0.7, for example, QKI with CLSTN1-575-ES, PLEKHM2-767-ES, KIF1B-601-AT, ACOT9-88694-ES, ARHGEF11-8338-ES, LRRFIP2-63960-ES, KIF1B-602-AT, SEPT11-69616-AT, MAP3K7-77020-ES, and CD47-66013-ES; BAG2 and DAB2IP-87442-AP; BUD31 and MFSD7-68391-AP; CELF2 and ARHGEF11-8338-ES; and RBFOX2 and CCSER2-12409-ES. These SF-AS pairs would be important when exploring the upstream SFs and downstream regulatory mechanisms of the OS-related AS events in STAD.

Figure 4.

Splicing factor-alternative splicing interaction network in stomach adenocarcinoma. The favorable prognosis of overall survival (OS)-related alternative splicing (AS) events are indicated in green; the unfavorable prognosis of OS-related AS events, red; the upstream splicing factors (SFs), blue; the negative correlation between SFs and OS-related AS events, green lines; the positive correlation between SFs and OS-related AS events, red lines.

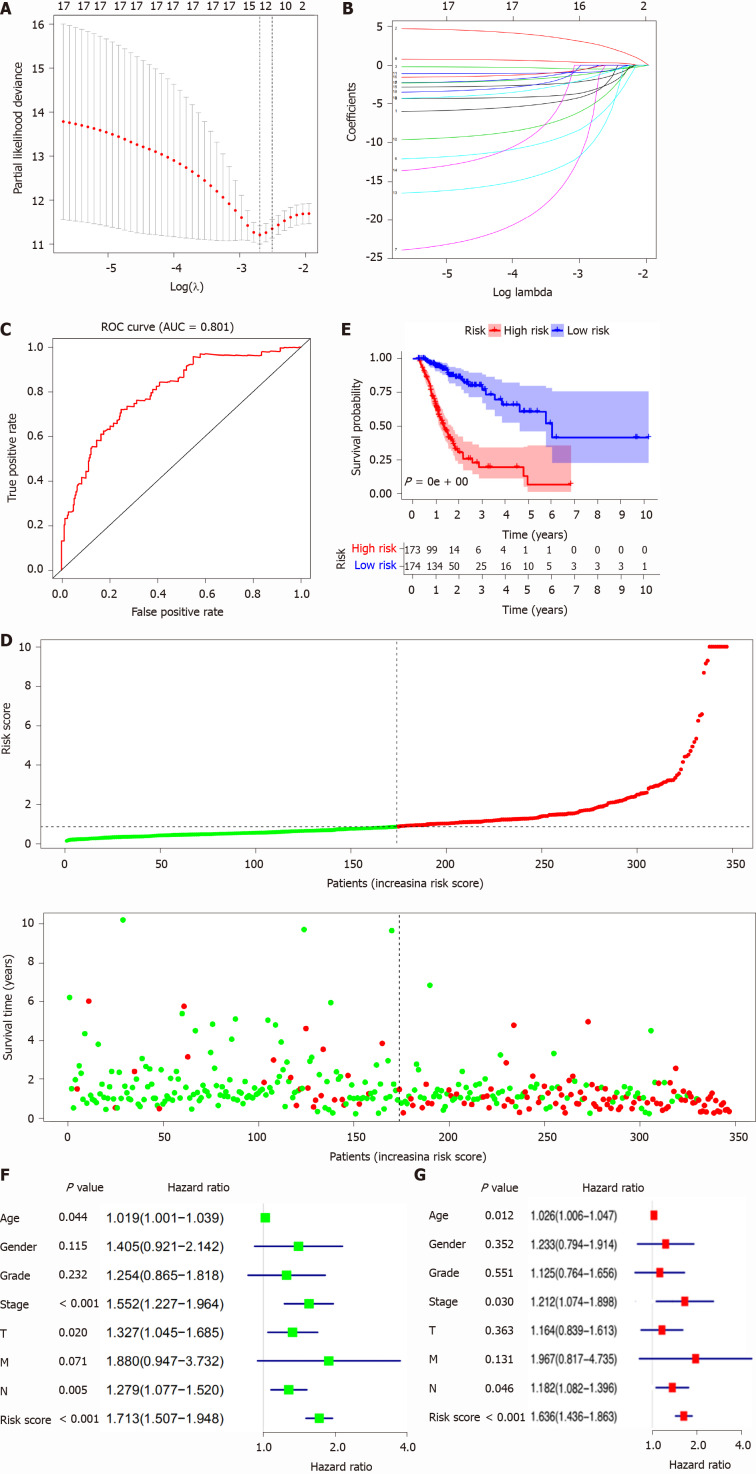

Construction of the OS-related AS prognostic model for STAD patients

The OS-related AS events were selected to construct a prognostic model for STAD patients using lasso regression. Furthermore, when log (lambda) was set within -2 and -3 (Figure 5A and B), a signature model of 11 OS-related AS events (CD44|14986|ES, PPHLN1|21214|AT, RASSF4|11351|ES, KIAA1147|82046|AP, PPP2R5D|76200|ES, LOH12CR1| 20507| ES, CDKN3|27569|AP, UBA52|48486|AD, CADPS|65499|AT, SRSF7|53276|RI, and WEE1|14328|AP) was obtained for STAD. On the basis of the OS-related AS-event signature model, the STAD samples were clustered into high- and low-risk-score groups based on the median risk score (median risk score = 0.87). In addition, the ROC revealed that the constructed prognostic model exhibited high sensitivity and specificity; the area under the curve was equal to 0.81 (Figure 5C). OS analysis revealed that high mortality occurred in the high-risk-score group (Figure 5D), and the survival probability was significantly different between the high- and low-risk-score groups (Figure 5E). Univariate analysis indicated that age, pathologic stage, pathologic T, pathologic N, and risk score were significantly associated with OS (Figure 5F). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that age, pathologic stage, pathologic N, and risk score might be independent risk factors for STAD (Figure 5G).

Figure 5.

Lasso regression identified the prognostic model in stomach adenocarcinoma. A and B: Lasso regression complexity was controlled by lambda using the glmnet R package; C: The receiver operating characteristic of risk score in stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD); D: Risk plot between the high- and low-risk-score groups; E: Overall survival analysis between the high- and low-risk-score groups; F: The univariate Cox regression analysis of risk factors in STAD; G: The multivariate Cox regression analysis of risk factors in STAD. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic; AUC: Area under the curve.

Gene-set enrichments between high- and low-risk-score groups based on the OS-related AS prognostic model in STAD

GSEA revealed 27 statistically significant gene sets between the high- and low-risk score groups in STAD. These included ECM receptor interaction (Figure 6A), cytokine and cytokine receptor interaction (Figure 6B), MAPK signaling pathway (Figure 6C), focal adhesion, neuroactive ligand receptor interaction, calcium signaling pathway, hematopoietic cell lineage, cell adhesion molecules, gap junction, leukocyte transendothelial migration, TGF beta signaling pathway, hedgehog signaling pathway, and pathways in cancer, which were enriched in the high-risk-score group, and spliceosome (Figure 6D), cell cycle (Figure 6E), proteasome (Figure 6F), homologous recombination, nucleotide excision repair, one carbon pool by folate, DNA replication, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism, peroxisome, aminoacyl tRNA biosynthesis, alanine aspartate and glutamate metabolism, pyrimidine metabolism, RNA degradation, and the citrate cycle, which were enriched in the low-risk-score group.

Figure 6.

Gene set enrichment analysis identified gene sets that were different between the high-risk-score group and low-risk-score group in stomach adenocarcinoma. A: The ECM receptor interaction pathway was significantly different between the high-risk-score group and low-risk-score group; B: The cytokine and cytokine receptor interaction pathway was significantly different between the high-risk-score group and low-risk-score group; C: The MAPK signaling pathway was significantly different between the high-risk-score group and low-risk-score group; D: The spliceosome pathway was significantly different between the high-risk-score group and low-risk-score group; E: The cell cycle pathway was significantly different between the high-risk-score group and low-risk-score group; F: The proteasome pathway was significantly different between the high-risk-score group and low-risk-score group.

Difference in distribution of immune cells, expressed IRGs, and immune-related pathways between the high- and low-risk-score groups

The proportion of immune cells in STAD was significantly different between the high- and low-risk groups, including naïve B cells, CD8 T cells, memory activated CD4 T cells, activated natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, M0 macrophages, and resting mast cells, activated mast cells, and neutrophils (Figure 7A). Additionally, certain immune cells that were distributed differently between the risk-score subtypes were correlated with each other, for example, neutrophils and activated mast cells, CD8 T cells and activated mast cells, CD8 T cells and activated CD4 memory T cells, CD8 T cells and M0 macrophages, and resting mast cells and activated mast cells (Figure 7B). Furthermore, 112 DEIRGs were identified between the high-risk-score group and low-risk score group, including 2 down-regulated IRGs and 110 up-regulated IRGs (Figure 7C). The identified DEIRGs were enriched in 13 significant KEGG pathways, such as pathways in cancer (Figure 7D), cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (Figure 7E), neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, Ras signaling pathway, TGF-beta signaling pathway, ErbB signaling pathway, Jak-STAT signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, melanoma, hematopoietic cell lineage, Rap1 signaling pathway, transcriptional misregulation in cancer, and MAPK signaling pathway. Certain DEIRGs were located at the key points of signaling pathways, for example, AR, EGF, FGF, FGFR, FLT3, and GPCR in pathways in cancer and CCL19, CCR9, GHR, NGFR, and BMPR1B in the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway.

Figure 7.

Difference in distribution of immune cells, expressed immune-related genes, and immune-related pathways between high- and low-risk score groups. A: Boxplot shows the differences in the ratio of nine immune cells between the high- and low-risk-score groups in stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD); B: The correlation between those nine immune cells in STAD; C: Volcano plot of differentially expressed immune-related genes (DEIRGs) in STAD between the high- and low-risk-score groups. Upregulated DEIRGs are indicated in red points and downregulated DEIRGs in green points; D: The pathways in cancer was significantly enriched among DEIRGs in STAD (P < 0.05); E: The cytokine and cytokine receptor interaction pathway was significantly enriched among DEIRGs in STAD (P < 0.05). aP < 0.05, and bP < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Early clinical signs and symptoms of STAD might include continuous upper abdominal pain, heartburn, loss of appetite, emesis, and nausea; however, these nonspecific clinical manifestations commonly result in misdiagnosis of STAD[20]. Most STAD patients progress to advanced stages with symptoms including yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes, vomiting, difficulty in swallowing, malnutrition, weight loss, intolerable pain, and blood in the stool[21]. The development of undiscovered biomarkers could improve the accuracy and specificity of disease prevention, risk prediction, and early diagnosis, promoting a more favorable prognosis in STAD[22]. AS events have been shown to play an essential role as both oncogenes and tumor suppressors in various human cancers, including STAD[23]. An increasing number of studies have shown that AS events could regulate tumor cell proliferation, cell death, the immune microenvironment, energy metabolism, epigenetic regulation, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, and drug resistance[24]. For example, RhoA, a member of the Rho family of small GTPases, has been identified as a driver of STAD through recent large-scale sequencing studies. The aberrant splicing variants of RHOA exclusively occurred in gastric carcinoma cell lines; however, wild-type RhoA was nearly undetectable using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis, which indicated that aberrant AS induced the loss of the activity and expression of RhoA in STAD cells[25]. A previous study demonstrated that splicing variants (M-RIP, CDCA1, HYAL2, and MSMB) showed differential expression between 38 cancer cell lines from various organs and 9 corresponding normal tissues. Furthermore, RT-PCR verified that 2 splicing variants of CDCA1 were upregulated in surgically resected gastric cancer tissues, while the variants of MSMB were predominantly determined in the corresponding normal tissues[26]. Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors, such as targeting PD-1 or PD-L1, is a novel treatment approach in clinical applications for various cancers, including STAD. Available reports regarding IRG expression and immune cell alteration in gastric cancer would be helpful in promoting potential clinical implications of immunotherapy for STAD patients[27]. Certain novel immune checkpoints on the T cell surface were observed to have the ability to inhibit T cell responses. For example, the T cell surface molecule TIGIT plays a crucial role in the development and progression of STAD. The percentage of TIGIT+CD8 T cells was increased in STAD patients compared with that in healthy individuals, and the TIGIT+CD8 T cells showed functional exhaustion with proliferation, cytokine production, impaired activation, and metabolism. Targeting of TIGIT enhances CD8 T cell activation and significantly improves the chances of survival of tumor-bearing mice[28]. Certain subtypes of immune cells have also been shown to be pivotal in cancer progression and prognosis in STAD. For example, prognosis and treatment outcomes in STAD patients can be predicted by analyzing cytokines and the proportion of immune cells. The proportions of CD45RO+HLA-DR+CD8 T lymphocytes, FoxP3+Tregs, and PD-1+CD3+T lymphocytes were identified as independent prognostic factors in STAD[29]. AS increases the diversity of the mRNA during transcription. Recently, AS was reported to play a role in the alteration of the immune microenvironment, thus influencing the development of immunotherapeutic strategies against cancer; therefore, the novel splicing variants discovered may be potentially useful targets for cancer therapy and could be utilized in immunotherapy[30].

Some of the OS-related AS events identified in this study have been reported to exhibit unique functions in tumorigenesis and prognosis in STAD. For example, CD44 is a cell-surface glycoprotein that is involved in a wide variety of cellular processes, such as cell-cell interactions, lymphocyte activation, cell adhesion and migration, recirculation and homing, tumor metastasis, hematopoiesis, and interaction with matrix metalloproteinases. The complex alternative splicing variants of CD44 have been determined to be related to tumor metastasis[31]. Certain variants of CD44 are associated with gastric cancer. Among the CD44 splicing variants, CD44v8-10 has been proven to be the most promising biomarker for theranostic agents in STAD. The differentially expressed CD44 splicing variant (CD44v8-10) has been verified in stomach cancer cell lines and 74 STAD patient tissues by exon-specific qRT-PCR[32]. TRA2B, as a sequence-specific serine/arginine SF, plays a role in splicing patterns, mRNA processing, and gene expression. Alternative splicing generates multiple transcript variants of TRA2B (tra2beta1-5). The functions of different transcript variants vary in gastric cancer cell lines. In a previous study, a gastric cancer cell line was treated with arsenite (100 µM) for generation of oxidative stress. In this process, the isoforms tra2beta4 and tra2beta1 continued to be upregulated at the level of mRNA expression; simultaneously, higher amounts of full-length tra2beta were translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during the initial 4-6 h (acute phase)[33]. TACC, a centrosome and microtubule-associated protein, is essential for mitotic spindle function. At least six different transcript variants of TACC1 have been found, and splicing variants of TACC1 with abnormal expression in gastric cancer cells might contribute to genetic instability. TACC1-D showed relatively strong expression in 50% of gastric cancer tissue samples but not in other normal tissues. Additionally, TACC1-F was observed to show predominant expression in gastric tumors[34]. Additionally, the identified OS-related AS events in our study were enriched in a wide variety of cancer-related pathways. Most of these pathways are crucial in the development and progression of STAD, and certain pathways have been reported to be affected by AS of important genes in pathways. For example, the autophagy pathway is critical for maintaining homeostasis; disruption of this pathway can mediate both tumorigenesis and tumor cell survival. The alternative mRNA splicing of the autophagy-related protein ATG5 specifically disrupted the binding pocket of ATG5-ATG16L1 interactions and blocked the conjugation of ATG12-ATG5. Therefore, the assembly and stability of the ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L1 complex in the autophagy pathway was damaged[35]. Mammalian cells sense oxygen and target multiple associated genes in response to hypoxia. The hypoxia signaling pathway is a hallmark of various solid tumors, due to the rapid proliferation of cancer cells and the alternative angiogenesis within tumors. Hypoxia-induced factor (HIF)-1 was identified as a key component in the hypoxia signaling pathway. One study suggested that HIF-1 isoforms modulated the expression of targeted genes with different activities under hypoxia. Both HIF-1alpha (736) and HIF-1alpha (FL) could combine with HIF-1beta to activate the VEGF promoter. However, the shorter HIF-1alpha isoform, which lacks the C-terminal transactivation domain, was 3-fold less active than HIF-1alpha (FL) under hypoxia [36]. In terms of the mechanism, a potential SF-AS regulatory network was constructed in our study, which explored the upstream SFs and downstream regulatory mechanisms of the OS-related AS events in STAD. Certain SFs were consistent with previous studies. For example, SRSF2 is a member of the serine/ arginine-rich family of pre-mRNA SFs and is critical for mRNA splicing. The reported data suggested that abnormal SRSF2 could set off a cascade of gene regulatory events that collectively drive cancer, known as the "splicing-cascade" phenotype, indicating that abnormal SFs could lead to widespread modifications in multiple proteins involved in RNA processing and splicing[37]. In our study, the identification of meaningful OS-related AS events in STAD and their upstream SFs or enriched cancer-related pathways involved in the development and progression of STAD would provide valuable prospects for clinical diagnosis and new therapeutic strategies.

Furthermore, a single gene for predicting the prognosis of STAD patients would be limited; therefore, the eleven-AS-signature prognostic model was constructed and significantly related to the OS in STAD. Most OS-associated AS genes in prognostic models have been proven to be related to cancers. For example, the upregulated CD44 variant isoforms are often observed in cancers and are significantly related to the more aggressive tumor phenotypes. CD44v9 is a major protein splicing variant of CD44, which is differentially expressed in human STAD cells. These findings indicate that targeting the cancer-related CD44v9 isoform has significant implications in clinical applications in STAD patients[38]. CDKN3, a dual-specificity protein tyrosine phosphatase, can dephosphorylate CDK1/CDK2 and other proteins. The expression and alternative splicing of CDKN3 are often abnormal in human cancers, which correlates with survival in several types of cancer. Certain CDKN3 transcript variants induce CDKN3 overexpression or CDKN3 activity, offering an advantage in tumorigenesis[39]. Alternative splicing of WEE1 has also been identified as a novel oncogene and prognostic biomarker to promote proliferation ability through regulating the cell cycle[40]. In a previous semiquantitative immunoblot analysis, HNRNPA1 and SRSF7 levels were significantly higher in gastric cancer than in gastric normal mucosa, and SRSF7 levels were higher in intestinal-type compared with diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinoma[41]. Our study demonstrates new findings that have not been reported in previous studies, including data on PPHLN1|21214|AT, RASSF4|11351|ES, KIAA1147|82046|AP, PPP2R5D|76200|ES, LOH12CR1|205 07|ES, UBA52|48486|AD, and CADPS|65499|AT. The functions and expression of the OS-associated AS genes in the prognostic model need to be verified in further experiments. In terms of mechanisms, the GSEA analysis demonstrated the differential enrichment of several gene sets between the high- and low-risk score groups. These gene sets indicated potential regulatory mechanisms of the prognostic model in STAD. Further study and verification of the identified OS-associated AS genes in a prognostic model is necessary.

Immunotherapy has achieved favorable effects in the management of advanced human cancers, and immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting CTLA-4 or PD-1 have revolutionized cancer immunotherapy[42]. Increasing evidence suggests that AS plays a crucial role in promoting tumorigenesis, progression, invasion, and metastasis in various cancer cells[43]. The process of AS on pre-mRNAs would increase the diversity of RNAs and proteins, and neo-antigens derived from different AS variants might alter the antigen-presenting mechanism. However, a limited number of cancer patients have been shown to respond to immunotherapy using cancer-specific RNA splicing[44]. This prompted us to explore whether STAD, which presents OS-related AS events, may exhibit a favorable response to immunotherapy. In this study, the proportion of immune cells in STAD was significantly different between the high- and low-risk groups, including naïve B cells, CD8 T cells, memory-activated CD4 T cells, activated NK cells, monocytes, M0 macrophages, resting mast cells, activated mast cells, and neutrophils. Furthermore, the IRGs that were expressed differently between the high-risk score group and low-risk score group were enriched in 13 significant cancer-related KEGG pathways. We conducted an in-depth investigation of IRGs driven by AS variants. For example, AR-V7 is an AS variant of the androgen receptor, and it has been shown to be associated with resistance against hormone therapies in prostate cancer[45]. Additionally, AS controlled the expression of human interleukin-5 receptor alpha, which generated two different AS variants encoding a membrane-anchored and a soluble form of the IL-5 receptors, respectively[46]. A systematic analysis of IRGs between AS-event subtypes would be beneficial for clarifying the role of splice variants in cancer immunotherapy.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this study included a systematic analysis of prognostic splicing events in STAD, constructed an elevated AS-signature prognostic model, and explored the association between AS and cancer immunity. The final OS-related AS events, DEIRGs, and the enriched pathways may play an important role in tumorigenesis in STAD; they deserve further study in clinical applications as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Alternative splicing (AS) increases the diversity of mRNA during transcription; it might play a role in alteration of the immune microenvironment, which could influence the development of immunotherapeutic strategies against cancer.

Research motivation

To explore survival-associated AS events which interact with immune microenvironment in stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD).

Research objectives

The overall survival data associated with AS events were used to construct a signature prognostic model for STAD.

Research methods

In STAD, 2042 overall-survival-related AS events were significantly enriched in various pathways and influenced several cellular functions.

Research results

An eleven-AS-signature prognostic model (CD44|14986|ES, PPHLN1|21214|AT, RASSF4|11351|ES, KIAA1147|82046|AP, PPP2R5D|76200|ES, LOH12CR1|205 07|ES, CDKN3|27569|AP, UBA52|48486|AD, CADPS|65499|AT, SRSF7|53276|RI, and WEE1|14328|AP) was constructed and significantly related to STAD overall survival, immune cells, and cancer-related pathways.

Research conclusions

This study provided an AS-related prognostic model, potential mechanisms for AS, and alterations in the immune microenvironment (immune cells, genes, and pathways) for future research in STAD.

Research perspectives

This study provided a paradigm in STAD.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The manuscript used data from TCGA database, which is a common database. The Institutional review board statement was not addressed in this article.

Clinical trial registration statement: The manuscript used data from TCGA database, which is a common database. The Clinical trial registration statement was not addressed in this article.

Informed consent statement: The manuscript used data from TCGA database, which is a common database. The Informed consent statement was not addressed in this article.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: December 25, 2020

First decision: January 17, 2021

Article in press: April 9, 2021

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tanabe H S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Zai-Sheng Ye, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology, Fujian Cancer Hospital & Fujian Medical University Cancer Hospital, Fuzhou 350014, Fujian Province, China.

Miao Zheng, Department of Clinical Laboratory, Fujian Maternity and Child Health Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350001, Fujian Province, China.

Qin-Ying Liu, Department of Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Tumor Biotherapy, Fujian Cancer Hospital & Fujian Medical University Cancer Hospital, Fuzhou 350014, Fujian Province, China.

Yi Zeng, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology, Fujian Cancer Hospital & Fujian Medical University Cancer Hospital, Fuzhou 350014, Fujian Province, China.

Sheng-Hong Wei, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology, Fujian Cancer Hospital & Fujian Medical University Cancer Hospital, Fuzhou 350014, Fujian Province, China.

Yi Wang, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology, Fujian Cancer Hospital & Fujian Medical University Cancer Hospital, Fuzhou 350014, Fujian Province, China.

Zhi-Tao Lin, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology, Fujian Cancer Hospital & Fujian Medical University Cancer Hospital, Fuzhou 350014, Fujian Province, China.

Chen Shu, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology, Fujian Cancer Hospital & Fujian Medical University Cancer Hospital, Fuzhou 350014, Fujian Province, China.

Qiu-Hong Zheng, Department of Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Tumor Biotherapy, Fujian Cancer Hospital & Fujian Medical University Cancer Hospital, Fuzhou 350014, Fujian Province, China.

Lu-Chuan Chen, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology, Fujian Cancer Hospital & Fujian Medical University Cancer Hospital, Fuzhou 350014, Fujian Province, China. luchuanchen@fjzlhospital.com.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Arndt V. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:467–477. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdi E, Latifi-Navid S, Zahri S, Yazdanbod A, Pourfarzi F. Risk factors predisposing to cardia gastric adenocarcinoma: Insights and new perspectives. Cancer Med. 2019;8:6114–6126. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagaraja AK, Kikuchi O, Bass AJ. Genomics and Targeted Therapies in Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1656–1672. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triantafillidis JK, Cheracakis P. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with early gastric cancer--a literature review. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:618–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polom K, Marrelli D, D'Ignazio A, Roviello F. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: how to look for and how to manage it. Updates Surg. 2018;70:161–166. doi: 10.1007/s13304-018-0545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuoka T, Yashiro M. Biomarkers of gastric cancer: Current topics and future perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2818–2832. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i26.2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tress ML, Abascal F, Valencia A. Alternative Splicing May Not Be the Key to Proteome Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demircioğlu D, Cukuroglu E, Kindermans M, Nandi T, Calabrese C, Fonseca NA, Kahles A, Lehmann KV, Stegle O, Brazma A, Brooks AN, Rätsch G, Tan P, Göke J. A Pan-cancer Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Pervasive Regulation through Alternative Promoters. Cell 2019; 178: 1465-1477. :e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omenn GS, Guan Y, Menon R. A new class of protein cancer biomarker candidates: differentially expressed splice variants of ERBB2 (HER2/neu) and ERBB1 (EGFR) in breast cancer cell lines. J Proteomics. 2014;107:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He C, Zhou F, Zuo Z, Cheng H, Zhou R. A global view of cancer-specific transcript variants by subtractive transcriptome-wide analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim E, Goren A, Ast G. Insights into the connection between cancer and alternative splicing. Trends Genet. 2008;24:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luco RF, Allo M, Schor IE, Kornblihtt AR, Misteli T. Epigenetics in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 2011;144:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S, Zhang J, Huang S, He X. Genome-wide analysis reveals that exon methylation facilitates its selective usage in the human transcriptome. Brief Bioinform. 2018;19:754–764. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim ST, Cristescu R, Bass AJ, Kim KM, Odegaard JI, Kim K, Liu XQ, Sher X, Jung H, Lee M, Lee S, Park SH, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, Lee H, Choi M, Talasaz A, Kang PS, Cheng J, Loboda A, Lee J, Kang WK. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat Med. 2018;24:1449–1458. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwak Y, Seo AN, Lee HE, Lee HS. Tumor immune response and immunotherapy in gastric cancer. J Pathol Transl Med. 2020;54:20–33. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2019.10.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng D, Li M, Zhou R, Zhang J, Sun H, Shi M, Bin J, Liao Y, Rao J, Liao W. Tumor Microenvironment Characterization in Gastric Cancer Identifies Prognostic and Immunotherapeutically Relevant Gene Signatures. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7:737–750. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Payer LM, Steranka JP, Ardeljan D, Walker J, Fitzgerald KC, Calabresi PA, Cooper TA, Burns KH. Alu insertion variants alter mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:421–431. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brosseau JP, Lucier JF, Nwilati H, Thibault P, Garneau D, Gendron D, Durand M, Couture S, Lapointe E, Prinos P, Klinck R, Perreault JP, Chabot B, Abou-Elela S. Tumor microenvironment-associated modifications of alternative splicing. RNA. 2014;20:189–201. doi: 10.1261/rna.042168.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhattacharya S, Andorf S, Gomes L, Dunn P, Schaefer H, Pontius J, Berger P, Desborough V, Smith T, Campbell J, Thomson E, Monteiro R, Guimaraes P, Walters B, Wiser J, Butte AJ. ImmPort: disseminating data to the public for the future of immunology. Immunol Res. 2014;58:234–239. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8516-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito M, Tanaka S, Chayama K. Characteristics and Early Diagnosis of Gastric Cancer Discovered after Helicobacter pylori Eradication. Gut Liver. 2020 doi: 10.5009/gnl19418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez A, Harada K, Mizrak Kaya D, Ajani JA. Current therapeutic landscape for advanced gastroesophageal cancers. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:78. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.10.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamashima C. Current issues and future perspectives of gastric cancer screening. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13767–13774. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Yuan Y. Alternative RNA splicing and gastric cancer. Mutat Res. 2017;773:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urbanski LM, Leclair N, Anczuków O. Alternative-splicing defects in cancer: Splicing regulators and their downstream targets, guiding the way to novel cancer therapeutics. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9:e1476. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyamoto S, Nagamura Y, Nakabo A, Okabe A, Yanagihara K, Fukami K, Sakai R, Yamaguchi H. Aberrant alternative splicing of RHOA is associated with loss of its expression and activity in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;495:1942–1947. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohnuma S, Miura K, Horii A, Fujibuchi W, Kaneko N, Gotoh O, Nagasaki H, Mizoi T, Tsukamoto N, Kobayashi T, Kinouchi M, Okabe M, Sasaki H, Shiiba K, Miyagawa K, Sasaki I. Cancer-associated splicing variants of the CDCA1 and MSMB genes expressed in cancer cell lines and surgically resected gastric cancer tissues. Surgery. 2009;145:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vrána D, Matzenauer M, Neoral Č, Aujeský R, Vrba R, Melichar B, Rušarová N, Bartoušková M, Jankowski J. From Tumor Immunology to Immunotherapy in Gastric and Esophageal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He W, Zhang H, Han F, Chen X, Lin R, Wang W, Qiu H, Zhuang Z, Liao Q, Zhang W, Cai Q, Cui Y, Jiang W, Wang H, Ke Z. CD155T/TIGIT Signaling Regulates CD8+ T-cell Metabolism and Promotes Tumor Progression in Human Gastric Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6375–6388. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park HS, Kwon WS, Park S, Jo E, Lim SJ, Lee CK, Lee JB, Jung M, Kim HS, Beom SH, Park JY, Kim TS, Chung HC, Rha SY. Comprehensive immune profiling and immune-monitoring using body fluid of patients with metastatic gastric cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:268. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0708-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez NM, Lynch KW. Control of alternative splicing in immune responses: many regulators, many predictions, much still to learn. Immunol Rev. 2013;253:216–236. doi: 10.1111/imr.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prochazka L, Tesarik R, Turanek J. Regulation of alternative splicing of CD44 in cancer. Cell Signal. 2014;26:2234–2239. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi ES, Kim H, Kim HP, Choi Y, Goh SH. CD44v8-10 as a potential theranostic biomarker for targeting disseminated cancer cells in advanced gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4930. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05247-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeo K, Kawai T, Nishida K, Masuda K, Teshima-Kondo S, Tanahashi T, Rokutan K. Oxidative stress-induced alternative splicing of transformer 2beta (SFRS10) and CD44 pre-mRNAs in gastric epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C330–C338. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00009.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Line A, Slucka Z, Stengrevics A, Li G, Rees RC. Altered splicing pattern of TACC1 mRNA in gastric cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2002;139:78–83. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00607-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wible DJ, Chao HP, Tang DG, Bratton SB. ATG5 cancer mutations and alternative mRNA splicing reveal a conjugation switch that regulates ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L1 complex assembly and autophagy. Cell Discov. 2019;5:42. doi: 10.1038/s41421-019-0110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gothié E, Richard DE, Berra E, Pagès G, Pouysségur J. Identification of alternative spliced variants of human hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6922–6927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang Y, Tebaldi T, Rejeski K, Joshi P, Stefani G, Taylor A, Song Y, Vasic R, Maziarz J, Balasubramanian K, Ardasheva A, Ding A, Quattrone A, Halene S. SRSF2 mutations drive oncogenesis by activating a global program of aberrant alternative splicing in hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2018;32:2659–2671. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0152-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreira IB, Pinto F, Gomes C, Campos D, Reis CA. Impact of Truncated O-glycans in Gastric-Cancer-Associated CD44v9 Detection. Cells. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/cells9020264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cress WD, Yu P, Wu J. Expression and alternative splicing of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor-3 gene in human cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;91:98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kouyama Y, Masuda T, Fujii A, Ogawa Y, Sato K, Tobo T, Wakiyama H, Yoshikawa Y, Noda M, Tsuruda Y, Kuroda Y, Eguchi H, Ishida F, Kudo SE, Mimori K. Oncogenic splicing abnormalities induced by DEAD-Box Helicase 56 amplification in colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:3132–3144. doi: 10.1111/cas.14163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park WC, Kim HR, Kang DB, Ryu JS, Choi KH, Lee GO, Yun KJ, Kim KY, Park R, Yoon KH, Cho JH, Lee YJ, Chae SC, Park MC, Park DS. Comparative expression patterns and diagnostic efficacies of SR splicing factors and HNRNPA1 in gastric and colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:358. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2387-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haanen JB, Robert C. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Prog Tumor Res. 2015;42:55–66. doi: 10.1159/000437178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Climente-González H, Porta-Pardo E, Godzik A, Eyras E. The Functional Impact of Alternative Splicing in Cancer. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2215–2226. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frankiw L, Baltimore D, Li G. Alternative mRNA splicing in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:675–687. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferraldeschi R, Welti J, Powers MV, Yuan W, Smyth T, Seed G, Riisnaes R, Hedayat S, Wang H, Crespo M, Nava Rodrigues D, Figueiredo I, Miranda S, Carreira S, Lyons JF, Sharp S, Plymate SR, Attard G, Wallis N, Workman P, de Bono JS. Second-Generation HSP90 Inhibitor Onalespib Blocks mRNA Splicing of Androgen Receptor Variant 7 in Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2731–2742. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pérez C, Vandesompele J, Vandenbroucke I, Holtappels G, Speleman F, Gevaert P, Van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction for measurement of human interleukin-5 receptor alpha spliced isoforms mRNA. BMC Biotechnol. 2003;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.