Key Points

Question

For adults with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin without prandial insulin in primary care practices, does continuous glucose monitoring improve hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels compared with blood glucose meter monitoring?

Findings

In a randomized clinical trial including 175 adults with type 2 diabetes, there was a significantly greater decrease in HbA1c level over 8 months with continuous glucose monitoring than with blood glucose meter monitoring (−1.1% vs −0.6%).

Meaning

Continuous glucose monitoring resulted in better glycemic control compared with blood glucose meter monitoring in adults with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin without prandial insulin.

Abstract

Importance

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has been shown to be beneficial for adults with type 2 diabetes using intensive insulin therapy, but its use in type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin without prandial insulin has not been well studied.

Objective

To determine the effectiveness of CGM in adults with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin without prandial insulin in primary care practices.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial was conducted at 15 centers in the US (enrollment from July 30, 2018, to October 30, 2019; follow-up completed July 7, 2020) and included adults with type 2 diabetes receiving their diabetes care from a primary care clinician and treated with 1 or 2 daily injections of long- or intermediate-acting basal insulin without prandial insulin, with or without noninsulin glucose-lowering medications.

Interventions

Random assignment 2:1 to CGM (n = 116) or traditional blood glucose meter (BGM) monitoring (n = 59).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level at 8 months. Key secondary outcomes were CGM-measured time in target glucose range of 70 to 180 mg/dL, time with glucose level at greater than 250 mg/dL, and mean glucose level at 8 months.

Results

Among 175 randomized participants (mean [SD] age, 57 [9] years; 88 women [50%]; 92 racial/ethnic minority individuals [53%]; mean [SD] baseline HbA1c level, 9.1% [0.9%]), 165 (94%) completed the trial. Mean HbA1c level decreased from 9.1% at baseline to 8.0% at 8 months in the CGM group and from 9.0% to 8.4% in the BGM group (adjusted difference, −0.4% [95% CI, −0.8% to −0.1%]; P = .02). In the CGM group, compared with the BGM group, the mean percentage of CGM-measured time in the target glucose range of 70 to 180 mg/dL was 59% vs 43% (adjusted difference, 15% [95% CI, 8% to 23%]; P < .001), the mean percentage of time at greater than 250 mg/dL was 11% vs 27% (adjusted difference, −16% [95% CI, −21% to −11%]; P < .001), and the means of the mean glucose values were 179 mg/dL vs 206 mg/dL (adjusted difference, −26 mg/dL [95% CI, −41 to −12]; P < .001). Severe hypoglycemic events occurred in 1 participant (1%) in the CGM group and in 1 (2%) in the BGM group.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among adults with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin without prandial insulin, continuous glucose monitoring, as compared with blood glucose meter monitoring, resulted in significantly lower HbA1c levels at 8 months.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03566693

This clinical trial compares the efficacy of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) vs traditional blood glucose meter monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin without prandial insulin in primary care practices.

Introduction

A study based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data between 2005 and 2012 estimated that approximately 30% of US residents with type 2 diabetes were treated with insulin, with about two-thirds using basal insulin without prandial insulin. Yet only 62% of individuals using insulin were estimated to have achieved a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of less than 8.0% and only 31% achieved a level of less than 7.0%.1 More recent evaluation of NHANES data suggests there had not been any improvement in diabetes glycemic outcomes in the US between 2005 and 2016.2

Glucose monitoring is central to safe and effective management for individuals with type 2 diabetes using insulin. Glucose management based on blood glucose meter (BGM) testing for individuals with type 2 diabetes using insulin has been demonstrated to be effective in treat-to-target trials3 and in observational studies,4 but other studies have documented that self-monitoring of blood glucose with self-titration of insulin was underutilized in routine practice.5,6

Real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), by providing glucose measurements as often as every 5 minutes, low and high glucose alerts, and glucose trend information, has the potential to better inform diabetes management decisions compared with episodic self-monitoring with a BGM. Studies have demonstrated that CGM improved glycemic control in individuals with type 1 diabetes7,8,9,10,11,12 and with type 2 diabetes using insulin regimens with basal plus prandial insulin.13 The role of CGM in individuals with type 2 diabetes using less-intensive insulin regimens is not well defined. To evaluate the effectiveness of CGM in these patients, an 8-month randomized, multicenter, clinical trial was conducted comparing CGM vs BGM monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin without prandial insulin whose diabetes was being managed by primary care clinicians.

Methods

Trial Conduct and Oversight

This multicenter, randomized, open-label, parallel-group trial was conducted at 15 centers in the US. Seven additional centers were certified for the study but did not randomize any participants. The protocol and informed consent form were approved by a central institutional review board for 14 centers and a local board for 1 center. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in Supplement 1. The protocol included 2 phases. This article reports the primary results for phase 1; phase 2, which included an evaluation of the effect of discontinuation of CGM, will be reported separately.

Trial Design and Participants

Potential participants were not under the care of an endocrinologist for their diabetes and were recruited from primary care practices. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Major eligibility criteria included age 30 years or older, diagnosis of type 2 diabetes treated with 1 or 2 daily injections of long- or intermediate-acting basal insulin for at least 6 months, locally measured HbA1c level of 7.8% to 11.5% (lower limit changed during study from 8.0% to 7.8% to enhance recruitment), self-reported BGM testing averaging at least 3 or more times per week, and availability of a smart phone compatible with the CGM device for data uploading. Participants could be using any other antidiabetic medication in addition to basal insulin, provided the regimen had been stable for at least 3 months, but not prandial insulin. See eTable 1 in Supplement 2 and a prior publication14 for a complete listing of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. To characterize the cohort with respect to the generalization of the results, race and ethnicity were recorded through self-report by the study participants from a structured list of choices.

Prior to randomization, each participant used a CGM system that recorded glucose concentrations not visible to the participant (“blinded” version of the CGM device used by the CGM group) for up to 10 days. Eligibility required a minimum of 168 hours of glucose values. Prior to randomization, blood was drawn for laboratory testing, height and weight were measured, and general diabetes education was provided per the center’s usual diabetes educational program.

On the study website, following verification of eligibility from data entered, each participant was assigned randomly from a computer-generated sequence to either the CGM or BGM group in a 2:1 ratio, using a permuted block design (random block sizes of 3 and 6) stratified by site. The random allocation sequence was generated by a study statistician at the Jaeb Center for Health Research.

Participants in both groups were provided with a Bluetooth-enabled BGM (OneTouch Verio Flex; LifeScan) and test strips. Participants in the BGM group were asked to perform BGM testing fasting and postprandial 1 to 3 times daily. Participants in the CGM group were provided with a Dexcom G6 Continuous Glucose Monitoring System, which is factory-calibrated and measures interstitial fluid glucose every 5 minutes, and instructed to use CGM continuously. The CGM group performed BGM testing as needed, particularly if CGM readings did not match symptoms. High and low glucose alert alarms were set at the start and adjusted as indicated during the study.

Follow-up clinic visits for both treatment groups to review glucose data and self-titration of insulin occurred after 2 weeks and 1 and 8 months, with virtual visits by telephone after 2, 4, and 6 months. After each clinic or virtual visit, the study clinician sent the glucose data record and management suggestions to the participant’s primary care clinician. Diabetes therapy changes were made by the primary care clinician, unless deemed imperative for safety by the study center investigator.

Both groups had a clinic visit at 3 months and a final visit at 8 months for HbA1c measurement. Height and weight were measured, and non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level was obtained at 8 months. The BGM group had a blinded CGM sensor placed at the 3-month visit and again at an additional visit prior to the 8-month visit. HbA1c level was measured at a central laboratory (University of Minnesota Advanced Research Diagnostic Laboratory) using the Tosoh G8 HPLC system (TOSOH Biosciences Inc). Participant-reported outcome surveys (eTable 2 in Supplement 2) completed at baseline and 8 months by both groups will be reported separately. The CGM satisfaction scale (44 items with a 1 to 5 Likert response scale; higher scores indicate a more positive perception of the use of CGM) was completed by the CGM group at 8 months and a mean score was computed for each participant, with a possible range of 1.0 to 5.0.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected the ability to complete in-clinic study visits beginning in March 2020 through the end of the study. When an in-clinic visit could not occur, a virtual visit was completed (N = 31 visits for 24 participants). For the 8-month visit, this included sending a kit to the participant for a fingerstick capillary blood draw that was sent to the same central laboratory for HbA1c measurement using the same method as the venous samples. This process using a fingerstick capillary blood draw has been demonstrated to have accuracy comparable with that of a venous blood draw.15

Outcomes

The primary outcome was HbA1c level at 8 months adjusted for the baseline value. Key secondary outcomes as part of a hierarchy with the primary outcome to control for the familywise type I error were CGM-measured time in the target glucose range of 70 to 180 mg/dL, time at greater than 250 mg/dL for glucose, and mean glucose level at 8 months adjusted for the baseline value. Other secondary outcomes included HbA1c level at 8 months adjusted for the baseline HbA1c value in subgroups based on the baseline HbA1c level: 8.5% or greater, 9.0% or greater, 9.5% or greater, and 10.0% or greater. Additional secondary and exploratory CGM outcome metrics included time at greater than 180 mg/dL, time at less than 70 mg/dL, and time at less than 54 mg/dL, and coefficient of variation. The 3 key secondary CGM outcomes plus the above listed secondary and exploratory CGM outcomes were selected based on a publication by an international consensus group.16,17 Additional secondary, exploratory, and post hoc outcomes are listed in eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

Reportable adverse events included all device or study-related adverse events, severe hypoglycemia (defined as an event that required assistance from another person to administer carbohydrates or other resuscitative action), severe hyperglycemia including diabetic ketoacidosis, and serious adverse events regardless of causality.

Sample Size and Power Calculation

Sample size was calculated to be 207 in order to have at least 85% power to detect a difference in mean HbA1c level between treatment groups, assuming a population difference of 0.4%, SD of the 8-month values of 0.8, a 2-sided α level of .05, and 165 participants completing the 8-month visit (assuming a 20% dropout rate). A 0.4% treatment group difference represents a clinically meaningful shift in the HbA1c distribution and is generally associated with at least a 50% greater proportion of participants experiencing improvement in HbA1c level by 10% or more, which was shown in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial to be associated with a substantial risk reduction in diabetic microvascular complications.18 This is further supported by the results of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, which showed that any improvement in HbA1c level is associated with a reduction in risk of diabetic complications.19

Statistical Analysis

Participant data were analyzed according to their randomization assignment. The analysis data set included all participants, except those deemed to not have type 2 diabetes after randomization. The primary analysis was a treatment group comparison of HbA1c level at 8 months in a longitudinal mixed-effects linear model with baseline HbA1c level as a fixed effect and clinical site as a random effect. A similar analysis was conducted on the 3-month HbA1c data. Binary HbA1c outcomes were evaluated in mixed-effects logistic regression models with baseline HbA1c level as a fixed effect and clinical site as a random effect. The adjusted differences for the binary outcomes were calculated as described by Kleinman and Norton20 and confidence intervals were calculated using bootstrap. The models for all outcomes handled missing data using direct likelihood analysis, which maximizes the likelihood function integrated over all possible values of the missing data. To assess for interaction between the treatment effect on HbA1c level at 8 months adjusted for baseline, interaction terms were included in mixed-effects models. Key secondary and exploratory CGM outcomes were calculated separately for daytime (6:00 am-11:59 pm) and nighttime (12:00 am-5:59 am) periods. To evaluate the interaction between the treatment effect and time of day, a treatment × time of day interaction term was included in mixed-effects models. The study was not specifically powered to test for interactions.

In a post hoc analysis, a linear regression model adjusting for baseline HbA1c level as a covariate and including main effects for treatment group and site, as well as a treatment × site interaction term, was used to test the heterogeneity of the treatment effect across sites. Additional statistical methods describing sensitivity analyses using different methods for accounting for missing data and the criteria for participant inclusion in the per-protocol analysis are described in eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). All P values are 2-sided. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05 for the primary analysis and for the 3 key secondary outcomes prespecified as part of a hierarchy with the primary outcome to control for the familywise type I error. For other secondary and exploratory outcomes, confidence intervals and P values were adjusted to control the false discovery rate using the 2-stage Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Throughout, to convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555.

Results

Although the sample size was planned to be 207, recruitment was stopped prior to reaching 207 when it was evident that the study completion rate was higher than projected and that achieving 165 participants completing the 8-month visit would require a smaller number randomized. A decision was made on September 25, 2019, by the study sponsor in conjunction with the coordinating center director to discontinue recruitment at the end of October 31, 2019. This decision was made in the absence of review of any outcome data, based on the following: number randomized as of September 25, 2019 = 154, number dropped prior to the 8-month visit = 4, number active in screening phase = 15, and anticipated additional recruitment between September 25, 2019, and October 31, 2019.

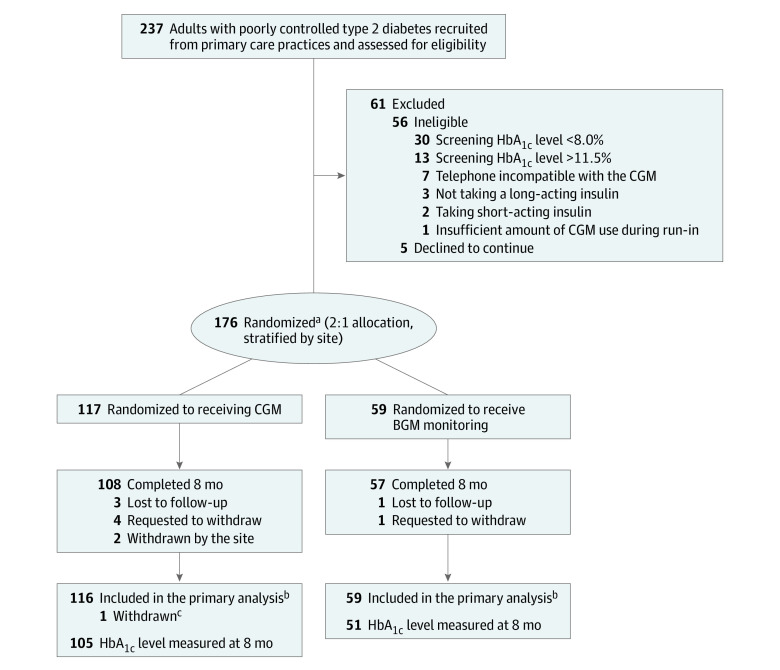

Between July 30, 2018, and October 30, 2019, 237 adults with type 2 diabetes were screened, of whom 61 did not proceed to the randomized trial (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2) and 1 with subsequently diagnosed type 1 diabetes was randomized but excluded from analyses. Of the remaining 175 randomized participants, 116 were assigned to the CGM group and 59 to the BGM group. The participants’ mean age was 57 years (range, 33-79 years) and 92 (53%) were of minority race or ethnicity. The mean baseline HbA1c level was 9.1% (range, 7.1%-11.6%). In addition to insulin, 16 participants (9%) were taking no other glucose-lowering medications at the time of randomization and 62 (35%) were taking 1 medication, 84 (48%) were taking 2 medications, 11 (6%) were taking 3 medications, and 2 (1%) were taking 4 medications (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Participant characteristics according to treatment group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline Demographics, Medical History, and Insulin Therapies.

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Continuous glucose monitoring (n = 116) | Blood glucose meter monitoring (n = 59) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56 (9) | 59 (9) |

| ≥60 | 43 (37) | 28 (47) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 61 (53) | 27 (46) |

| Male | 55 (47) | 32 (54) |

| Race or ethnicitya | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 50 (43) | 33 (56) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 35 (30) | 14 (24) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 24 (21) | 8 (14) |

| Asian | 4 (3) | 4 (7) |

| >1 Race | 2 (2) | 0 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Highest education level | ||

| <High school diploma | 26 (22) | 10 (17) |

| High school | 39 (34) | 21 (36) |

| Bachelor degree | 35 (30) | 24 (41) |

| Advanced degree | 15 (13) | 4 (7) |

| Did not provide | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Insurance coverageb | ||

| Private | 51 (44) | 22 (37) |

| Medicare | 42 (36) | 26 (44) |

| Medicaid | 11 (9) | 6 (10) |

| Other government insurance | 9 (8) | 3 (5) |

| None | 3 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Diabetes duration, mean (SD), y | 14 (9) | 15 (10) |

| Self-reported blood glucose meter monitoring, checks per day | ||

| ≤1 | 61 (53) | 23 (39) |

| 2-3 | 54 (47) | 36 (61) |

| ≥4 | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 2) |

| No. of noninsulin glucose-lowering medicationsc | ||

| None | 11 (9) | 5 (8) |

| 1 | 42 (36) | 20 (34) |

| 2 | 56 (48) | 28 (47) |

| 3 | 6 (5) | 5 (8) |

| ≥4 | 1 (<1) | 1 (2) |

| HbA1c level, % | ||

| At screening, mean (SD)d | 9.2 (1.0) | 9.0 (0.9) |

| At randomizationd | ||

| Mean (SD) [No.] | 9.1 (1.0) [115] | 9.0 (0.9) [58] |

| <8.5% | 31 (27) | 17 (29) |

| 8.5%-<10.0% | 58 (50) | 32 (55) |

| ≥10.0% | 26 (23) | 9 (16) |

| BMI | ||

| Mean (SD) [No.] | 33.8 (6.7) [115] | 33.9 (6.3) |

| Severely obese (≥35) | 44 (38) | 23 (39) |

| Basal insulin, mean (SD), U/kg/d | 0.47 (0.26) | 0.49 (0.30) |

| Nonfasting C-peptide level, mean (SD) [No.], ng/mLe | 2.9 (2.2) [112] | 3.4 (3.0) [51] |

| Non-HDL cholesterol level, mean (SD), mg/dLe | 122 (47) | 121 (43) |

| Subjective numeracy scale, mean (SD)f | 4.0 (1.0) | 3.9 (1.1) |

Abbreviations: BGM, blood glucose meter; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IQR, interquartile range.

Race/ethnicity is self-reported.

Medicare includes 9 in the CGM group and 2 in the BGM group who also had private insurance, and 2 in the CGM group and 1 in the BGM group who also had Medicaid. Medicaid includes 2 in the CGM group who also reported having private insurance.

See eTable 4 in Supplement 2 for listing of specific medications. Most participants taking a single medication were using metformin (n = 31 in the CGM group and 13 in the BGM group). Most patients taking 2 medications were taking a combination of metformin and sulfonylurea (n = 31 in the CGM group and 21 in the BGM group) or a combination of metformin and a GLP-1-agonist (n = 19 in the CGM group and 3 in the BGM group).

Screening HbA1c level was measured locally, which may have been a point-of-care device, and randomization HbA1c level was measured about 10 days at the central laboratory (randomization HbA1c level used in all analyses).

C-peptide and cholesterol levels were measured locally at each study center; normal ranges varied between sites. Additionally, C-peptide was nonfasting for which there is no established normal range.

Includes 8 items, each on a 1-6 scale, evaluating ability to perform various mathematical tasks and preferences for the use of numerical vs prose information as an indicator of mathematical ability that may be useful for diabetes management. Each item is on a 1-6 scale. The score for a participant represents an average across the 6 items, with a higher score denoting a higher perceived mathematical ability.

Follow-up was completed on July 7, 2020. The 8-month primary study outcome visit was completed by 108 participants (93%) in the CGM group and 57 (97%) in the BGM group (Figure 1; eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). Eight-month HbA1c results were available for 105 participants (91%) in the CGM group and 51 (86%) in the BGM group; of the 19 participants without an 8-month HbA1c value, 14 (74%) had a 3-month value. In the CGM group, the median CGM use was 6.1 days per week (interquartile range, 5.1-6.6) over the 8 months (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). No participant in the BGM group initiated CGM use prior to the primary outcome.

Figure 1. Screening, Allocation, and Study Follow-up.

BGM indicates blood glucose meter; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; and HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

aThree participants who wore CGM for less than 70% of the time during the 10-day prerandomization screening phase (≥70% was eligibility criterion) were randomized: 2 to the CGM group and 1 to the BGM group.

bOne participant in each group was missing baseline data.

cOne participant randomized to the CGM group who was determined after randomization to have type 1 diabetes was excluded from the analyses (participant had HbA1c level of 8.2% at baseline, 7.3% at month 3, and 6.8% at month 8).

The mean number of blood glucose self-monitoring was 1.4 tests per day at baseline and 0.7 tests per day at 8 months in the CGM group, and 1.5 tests per day at baseline and 1.5 tests per day at 8 months in the BGM group (adjusted difference, −0.79 [95% CI, −1.13 to −0.45]; P < .001; eTable 6 in Supplement 2).

Primary and Key Secondary Outcomes

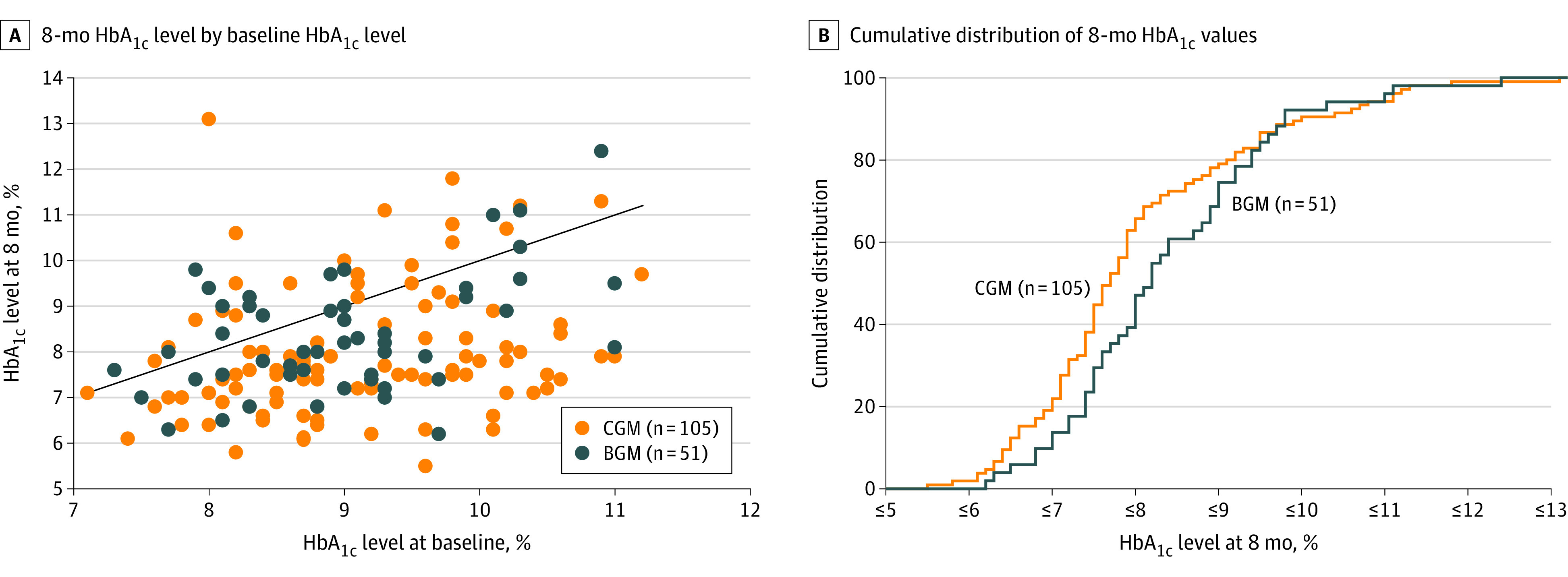

The mean HbA1c level, which was 9.1% in the CGM group and 9.0% in the BGM group at baseline, decreased to 8.0% vs 8.4%, respectively, at the 8-month primary outcome (adjusted difference in mean change in HbA1c level, −0.4% [95% CI, −0.8% to −0.1%]; P = .02; Table 2; Figure 2). Results of the per-protocol analysis and 2 sensitivity analyses with different methods for handling missing data are provided in eTable 7 in Supplement 2.

Table 2. Glycemic Outcomesa.

| Mean (SD) | 8-mo Risk-adjusted difference, % (95% CI) | P valueb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 8 mo | |||||

| Continuous glucose monitoring | Blood glucose meter monitoring | Continuous glucose monitoring | Blood glucose meter monitoring | |||

| Primary outcomec | ||||||

| No. | 115 | 58 | 105 | 51 | ||

| HbA1c level, % | 9.1 (1.0) | 9.0 (0.9) | 8.0 (1.4) | 8.4 (1.3) | .02 | |

| Change from baseline, % | −1.1 (1.5) | −0.6 (1.2) | −0.4 (−0.8 to −0.1) | |||

| Key secondary outcomesd | ||||||

| No. | 114 | 59 | 93 | 53 | ||

| % Time in range of 70-180 mg/dL | 40 (26) | 40 (25) | 59 (25) | 43 (26) | 15 (8 to 23) | <.001 |

| % Time >250 mg/dLe | 26 (22) | 25 (21) | 11 (11) | 27 (24) | −16 (−21 to −11) | <.001 |

| Mean glucose, mg/dL | 209 (48) | 206 (45) | 179 (43) | 206 (53) | −26 (−41 to −12) | <.001 |

| Additional HbA1c outcomes, No. (%)f | ||||||

| No. | 115g | 58g | 105h | 51h | ||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Reduction from baseline ≥0.5% | NA | NA | 76 (73) | 33 (65) | 9.9 (0.1 to 21.1) | .05 |

| Exploratory outcomes | ||||||

| <7.0% | 0 | 0 | 20 (19) | 5 (10) | 11.8 (0.6 to 24.5) | .04 |

| <7.5% | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 40 (38) | 12 (24) | 17.6 (0.6 to 34.3) | .04 |

| Relative reduction from baseline ≥10% | NA | NA | 66 (63) | 21 (41) | 22.4 (12.0 to 32.0) | <.001 |

| Reduction from baseline ≥1% | NA | NA | 56 (54) | 20 (39) | 14.7 (−1.2 to 30.4) | .07 |

| Reduction from baseline ≥1% or HbA1c <7.0% | NA | NA | 57 (55) | 20 (39) | 15.6 (0.7 to 30.0) | .04 |

| Additional CGM outcomes, mean (SD)i | ||||||

| No. | 114 | 59 | 93 | 53 | ||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Proportion improving time in range 70-180 mg/dL, No. (%) | ||||||

| ≥10% | NA | NA | 54 (59) | 20 (38) | 22.1 (7.5 to 35.7) | .006 |

| ≥15% | NA | NA | 49 (54) | 17 (32) | 22.1 (10.4 to 33.2) | .001 |

| Glucose variability: coefficient of variation, %j | 28 (7) | 28 (7) | 27 (6) | 29 (6) | −1.8 (−3.5 to 0.0) | .05 |

| % Time <70 mg/dLe | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.5 (0.8) | −0.24 (−0.42 to −0.05) | .02 |

| Exploratory outcomes | ||||||

| % Time >300 mg/dLe | 11.8 (13.2) | 10.7 (12.1) | 3.8 (5.5) | 11.9 (13.7) | −8.1 (−11.0 to −5.2) | <.001 |

| % Time >180 mg/dL | 59 (26) | 59 (26) | 41 (25) | 57 (27) | −15.1 (−22.9 to −7.3) | <.001 |

| Area under curve at 180 mg/dLe | 44.6 (31.6) | 42.0 (29.6) | 21.1 (17.3) | 43.5 (34.3) | −22.2 (−29.6 to −14.8) | <.001 |

| % Time <54 mg/dLe | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.3) | −0.10 (−0.15 to −0.04) | .001 |

| Hypoglycemia event rate/wke,k | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.4) | −0.1 (−0.2 to −0.1) | <.001 |

| Proportion with time in range >70%, No. (%) | 12 (11) | 8 (14) | 33 (35) | 10 (19) | 16.9 (3.7 to 29.6) | .01 |

| Post hoc outcomes, No. (%) | ||||||

| HbA1c level <8.0%l | 10 (9) | 6 (10) | 66 (63) | 20 (39) | 25.8 (14.2 to 36.8) | <.001 |

| ≥5% Increase in time in rangem | NA | NA | 60 (66) | 23 (43) | 23.1 (6.2 to 40.2) | .01 |

Abbreviations: BGM, blood glucose meter; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; NA, not applicable.

SI conversion factor: To convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555.

Additional secondary and exploratory outcomes are shown eTables 7-10 in Supplement 2.

The primary outcome and key secondary outcomes were part of a statistical hierarchy to control for the familywise type I error rate. For all other outcomes, nominal (uncorrected) P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the adaptive 2-stage group Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Point estimate, confidence interval, and P value estimated using a mixed-effects linear regression model adjusting for baseline HbA1c level and a random site effect.

Key secondary outcomes measured with CGM and included in the statistical hierarchy with the primary outcome. Point estimates, confidence intervals, and P values were calculated using a mixed-effects linear regression model adjusting for the baseline value of the outcome and a random site effect. Outcomes tested in a hierarchy to control for the familywise error rate. At baseline, the median number of CGM values per participant used in the computation of the CGM metrics was 2831 and 2819 in the BGM group, and at 8 months, there were 2925 values per participant in the CGM group and 2746 in the BGM group. Among participants with 8-month HbA1c data missing, 3-month HbA1c level was available and included in the model for 6 of 11 in the CGM group and 8 of 8 in the BGM group. Of participants without 8-month CGM data, 3-month CGM data were available and included in the model for 16 of 23 in the CGM group and 4 of 6 in the BGM group.

Winsorized at the 10th and 90th percentiles prior to reporting summary statistics.

For continuous HbA1c outcomes, a mixed-effects linear regression model was fitted, adjusted for baseline HbA1c level and a random site effect. Local HbA1c level was included as an auxiliary variable. For binary outcomes, a mixed-effects logistic regression model was fitted, adjusting for baseline HbA1c level and a random site effect. The 95% CIs are reported for the mean difference for continuous outcomes and difference in proportion for binary outcomes.

HbA1c level missing at baseline for 1 participant in each group.

HbA1c level missing at 8 months for 11 participants in the CGM group and 8 participants in the BGM group.

For continuous CGM outcomes, a mixed-effects linear regression model was fitted, adjusting for the baseline value of the outcome and a random site effect; for binary outcomes, a mixed-effects logistic regression model was fitted, adjusting for the baseline value of the outcome and a random site effect. The 95% CIs are reported for the mean difference for continuous outcomes and difference in proportion for binary outcomes.

The coefficient of variation represents a measure of glucose variability and is calculated by taking the SD of glucose values divided by the mean of glucose values.

Analytic definition of a CGM-measured hypoglycemic event: A hypoglycemic event was defined as 15 consecutive minutes with a sensor glucose value below 54 mg/dL (at least 2 sensor values <54 mg/dL that are ≥15 minutes apart plus no intervening values of ≥54 mg/dL are required to define an event). The end of the hypoglycemic event was defined as a minimum of 30 consecutive minutes with a sensor glucose concentration of 70 mg/dL or greater (at least 2 sensor values ≥70 mg/dL that are ≥30 minutes apart with no intervening values <70 mg/dL were required to define the end of an event). When a hypoglycemic event ended, the study participant became eligible for a new event.

Post hoc outcome to provide results with respect to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set performance metric of HbA1c level less than 8.0%

Post hoc outcome to provide results for a 5% change in time in range, which is considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Values at 8 Months.

BGM indicates blood glucose meter; and CGM, continuous glucose monitoring.

A, In this scatterplot, points below the diagonal line represent cases in which the 8-month HbA1c level was lower than the baseline level (80 [76%] in the CGM group vs 34 [67%] in the BGM group) and points above the diagonal line represent cases in which the 8-month HbA1c level was higher than the baseline level (23 [22%] in the CGM group vs 14 [27%] in the BGM group). Two participants in the CGM group and 3 in the BGM group had a baseline value equal to the 8-month value.

B, For any given 8-month HbA1c level, the percentage of participants in each treatment group with a HbA1c value at that level or lower can be determined from the figure.

The 3 key secondary outcomes included in the statistical hierarchy with the primary outcome—CGM-measured time in the target glucose range of 70 to 180 mg/dL, time at greater than 250 mg/dL for glucose, and mean glucose level—all showed statistically significant treatment group differences. In the CGM group, compared with the BGM group, the mean percentage of time at 70 to 180 mg/dL was 59% vs 43% (adjusted mean difference, 15% [95% CI, 8% to 23%]; P < .001; equivalent to 3.6 hours more per day; Table 2). The mean percentage of time at greater than 250 mg/dL was 11% vs 27% (adjusted mean difference, −16% [95% CI, −21% to −11%]; P < .001; equivalent to 3.8 hours less per day; Table 2). There was a downward shift in mean glucose levels throughout the 24 hours of the day (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2), with the means of mean glucose level of 179 mg/dL vs 206 mg/dL (adjusted difference, −26 mg/dL [95% CI, −41 to −12]; P < .001) in the CGM group compared with the BGM group.

Other Glycemic Outcomes

Among participants with baseline HbA1c levels of 8.5% or greater, there was not a statistically significant treatment group difference in 8-month HbA1c level (P = .10, eTable 8 in Supplement 2). In exploratory subgroup analyses, there was no statistically significant interaction assessing the treatment effect on 8-month HbA1c levels according to levels of baseline factors (eTable 9 in Supplement 2). There also was no statistically significant heterogeneity of effect across the clinical sites in a post hoc analysis (P for interaction = .37). There was not statistically significant interaction of the effect of CGM on the 3 key secondary glycemic outcomes comparing daytime and nighttime (eTable 10 in Supplement 2).

In an exploratory analysis, there was a suggestion of a reduction in CGM-measured hypoglycemia in the CGM group compared with the BGM group at 8 months for time at less than 54 mg/dL (adjusted mean difference, −0.10% [95% CI, −0.15% to −0.04%]; P = .001) and time at less than 70 mg/dL (adjusted mean difference, −0.24% [95% CI, −0.42% to −0.05%]; P = .02).

Diabetes Treatments and Metabolic Outcomes

In an exploratory analysis, there were no statistically significant differences between groups in the total daily insulin dose, nor were there significant differences in the addition or reduction of diabetes medications in post hoc analyses (eTables 11, 12, and 13 in Supplement 2). Prandial insulin was started by 12 participants (10%) in the CGM group and 9 (15%) in the BGM group. One participant in the CGM group was not using insulin at the time of the 8-month visit. A study center investigator made a medication change for safety in response to hypoglycemia on 23 occasions for 21 participants (18%) in the CGM group and on 24 occasions for 17 participants (29%) in the BGM group.

There were no statistically significant differences between groups in change in body weight, blood pressure, or non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in exploratory analyses (eTable 14 in Supplement 2).

Adverse Events

A severe hypoglycemic event occurred in 1 participant (1%) in the CGM group and in 1 (2%) in the BGM group. There was 1 occurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis in the CGM group (Table 3). A complete listing of reported adverse events is provided in eTable 15 in Supplement 2.

Table 3. Adverse Events and Serious Adverse Eventsa.

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Continuous glucose monitoring (n = 116) | Blood glucose meter monitoring (n = 59) | |

| Adverse events (including serious adverse events)b | ||

| No. of adverse events | 45 | 16 |

| Participants with ≥1 adverse events | 30 (26) | 12 (20) |

| Serious adverse events (excluding severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis events)b | ||

| No. of adverse events | 14 | 7 |

| Participants with ≥1 adverse events | 10 (9) | 5 (9) |

| Severe hypoglycemic events | ||

| No. of severe hypoglycemic events | 1 | 1 |

| Participants with ≥1 severe hypoglycemic events | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis events | ||

| No. of diabetic ketoacidosis events | 1 | 0 |

| Participants with ≥1 diabetic ketoacidosis events | 1 (1) | 0 |

See eTable 15 in Supplement 2 for a full listing of adverse events.

A serious adverse event was defined as any untoward medical occurrence that resulted in death or was life-threatening, required in-patient hospitalization or prolonged hospitalization, resulted in persistent or significant disability, or required medical or surgical intervention to prevent permanent impairment.

CGM Satisfaction Scale

In the CGM group, the mean score on the CGM satisfaction scale was 4.1, with mean scores of 4.2 on the benefits subscale and 1.9 on the hassles subscale (greater value is reflected in a higher score on the benefits subscale and a lower score on the hassles subscale) (eTable 16 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

In this randomized trial of patients with type 2 diabetes and poor glycemic control (mean HbA1c level, 9.1%) treated with basal insulin without prandial insulin and recruited from a primary care setting, HbA1c level improvement at 8 months was significantly greater in participants using CGM than in participants using a BGM alone for glucose monitoring. The greater HbA1c level improvement was reflected in an increase in CGM-measured time in the target glucose range of 70 to 180 mg/dL and a reduction in both time spent at greater than 250 mg/dL and mean glucose level.

Exploratory subgroup analyses based on baseline participant characteristics suggested that a HbA1c level difference favoring the CGM group was present across the age range of 33 to 79 years and the baseline HbA1c range of 7.1% to 11.6%, for all education levels, and in those with higher and lower diabetes numeracy. HbA1c level improvement was achieved while reducing the frequency of CGM-measured hypoglycemia.

The high rate of persistent CGM use over 8 months and the high scores on the CGM satisfaction scale are similar to the findings of a randomized trial evaluating CGM in patients with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin plus prandial insulin.13 To our knowledge, there has not been a prior randomized trial that has evaluated CGM in patients with type 2 diabetes using basal but not prandial insulin.

The strengths of this study included a racially and socioeconomically diverse study population, with most participants being non-White, with less than a college degree, and without private insurance. The study assessed the benefit of CGM vs optimized care for the BGM group, which was reflected in improvement in HbA1c level in the BGM group. Because type 2 diabetes is primarily managed in the primary care setting and not by endocrinologists, the study was designed to recruit patients from primary care practices. However, the involvement of the diabetes specialists in this study as advisors to primary care clinicians is not currently standard practice in many clinical settings and thus limits the generalizability of the study findings.

Limitations

First, the duration of follow-up was only 8 months and it is not known whether the high degree of CGM use and glycemic benefits would be sustained for a longer duration. A 6-month extension phase of the study may provide some insights in this regard. Second, although the participant retention rate was higher than projected in designing the trial, some of the 8-month visits needed to be completed virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic that resulted in some participants not having 8-month HbA1c or CGM data. Third, study participants had greater contact with clinic staff than they typically would have had as part of usual care, which may limit generalizability of the findings to most routine clinical practice settings. Fourth, while benefit of CGM, compared with BGM monitoring, was observed, the finding that about one-third of the CGM group still had an HbA1c level greater than 8% after 8 months suggests that more aggressive approaches to pharmacologic management may have been beneficial.

Conclusions

Among adults with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin without prandial insulin, CGM, as compared with BGM monitoring, resulted in significantly lower HbA1c levels at 8 months.

Trial Protocol

MOBILE Study Group Listing

eFigure 1. Flow Chart of Screening

eFigure 2. Flow Chart of Visit Completion Rates

eFigure 3. Mean Glucose Over 24 Hours at 8 Months

eTable 1. Patient Eligibility Criteria

eTable 2. Description of Quality of Life and Satisfaction Questionnaires

eTable 3. Secondary and Exploratory Study Outcomes and Additional Statistical Methods

eTable 4. Glucose Lowering Medications in Use at Time of Randomization in Addition to Insulin

eTable 5. CGM Use in CGM Group

eTable 6. Frequency of Blood Glucose Meter Testing

eTable 7. Change in HbA1c: Per-Protocol Analysis and Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 8. Change in HbA1c According to Baseline HbA1c Group

eTable 9. Change in HbA1c According to Baseline Subgroups

eTable 10. CGM Outcomes According to Time of Day

eTable 11. Daily Insulin Delivery

eTable 12. Additions and Discontinuations of Diabetes Medications and Insulin Use

eTable 13. Medications Added and Stopped During Follow-up

eTable 14. Body Weight, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol

eTable 15. Listing of Types of Reported Adverse Events

eTable 16. CGM Satisfaction Scale

Nonauthor Collaborators. MOBILE Study Group

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Selvin E, Parrinello CM, Daya N, Bergenstal RM. Trends in insulin use and diabetes control in the US: 1988-1994 and 1999-2012. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(3):e33-e35. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazemian P, Shebl FM, McCann N, Walensky RP, Wexler DJ. Evaluation of the cascade of diabetes care in the United States, 2005-2016. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(10):1376-1285. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnell O, Hanefeld M, Monnier L. Self-monitoring of blood glucose: a prerequisite for diabetes management in outcome trials. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8(3):609-614. doi: 10.1177/1932296814528134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murata GH, Shah JH, Hoffman RM, et al. ; Diabetes Outcomes in Veterans Study (DOVES) . Intensified blood glucose monitoring improves glycemic control in stable, insulin-treated veterans with type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Outcomes in Veterans Study (DOVES). Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1759-1763. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falk J, Friesen KJ, Okunnu A, Bugden S. Patterns, policy and appropriateness: a 12-year utilization review of blood glucose test strip use in insulin users. Can J Diabetes. 2017;41(4):385-391. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossi MC, Lucisano G, Ceriello A, et al. ; AMD Annals-SMBG Study Group . Real-world use of self-monitoring of blood glucose in people with type 2 diabetes: an urgent need for improvement. Acta Diabetol. 2018;55(10):1059-1066. doi: 10.1007/s00592-018-1186-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck RW, Riddlesworth T, Ruedy K, et al. ; DIAMOND Study Group . Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(4):371-378. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolinder J, Antuna R, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn P, Kröger J, Weitgasser R. Novel glucose-sensing technology and hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, non-masked, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2254-2263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31535-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermanns N, Schumann B, Kulzer B, Haak T. The impact of continuous glucose monitoring on low interstitial glucose values and low blood glucose values assessed by point-of-care blood glucose meters: results of a crossover trial. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8(3):516-522. doi: 10.1177/1932296814524105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lind M, Polonsky W, Hirsch IB, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring vs conventional therapy for glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes treated with multiple daily insulin injections: the GOLD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(4):379-387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Beers CA, DeVries JH, Kleijer SJ, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring for patients with type 1 diabetes and impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia (IN CONTROL): a randomised, open-label, crossover trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(11):893-902. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30193-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong JC, Foster NC, Maahs DM, et al. ; T1D Exchange Clinic Network . Real-time continuous glucose monitoring among participants in the T1D Exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(10):2702-2709. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck RW, Riddlesworth TD, Ruedy K, et al. ; DIAMOND Study Group . Continuous glucose monitoring versus usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving multiple daily insulin injections: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(6):365-374. doi: 10.7326/M16-2855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters A, Cohen N, Calhoun P, et al. Glycaemic profiles of diverse patients with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin: MOBILE study baseline data. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(2):631-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck RW, Bocchino LE, Lum JW, et al. An evaluation of two capillary sample collection kits for laboratory measurement of HBALC. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23(8):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the International Consensus on Time in Range. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1593-1603. doi: 10.2337/dci19-0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danne T, Nimri R, Battelino T, et al. International consensus on use of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(12):1631-1640. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group . The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes. 1995;44(8):968-983. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.8.968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):405-412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinman LC, Norton EC. What’s the risk? a simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(1):288-302. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00900.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

MOBILE Study Group Listing

eFigure 1. Flow Chart of Screening

eFigure 2. Flow Chart of Visit Completion Rates

eFigure 3. Mean Glucose Over 24 Hours at 8 Months

eTable 1. Patient Eligibility Criteria

eTable 2. Description of Quality of Life and Satisfaction Questionnaires

eTable 3. Secondary and Exploratory Study Outcomes and Additional Statistical Methods

eTable 4. Glucose Lowering Medications in Use at Time of Randomization in Addition to Insulin

eTable 5. CGM Use in CGM Group

eTable 6. Frequency of Blood Glucose Meter Testing

eTable 7. Change in HbA1c: Per-Protocol Analysis and Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 8. Change in HbA1c According to Baseline HbA1c Group

eTable 9. Change in HbA1c According to Baseline Subgroups

eTable 10. CGM Outcomes According to Time of Day

eTable 11. Daily Insulin Delivery

eTable 12. Additions and Discontinuations of Diabetes Medications and Insulin Use

eTable 13. Medications Added and Stopped During Follow-up

eTable 14. Body Weight, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol

eTable 15. Listing of Types of Reported Adverse Events

eTable 16. CGM Satisfaction Scale

Nonauthor Collaborators. MOBILE Study Group

Data Sharing Statement