Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 outbreaks associated with mass religious gatherings which have the potential of invoking epidemics at large scale have been a great concern. This study aimed to evaluate the risk of outbreak in mass religious gathering and further to assess the preparedness of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) for preventing COVID-19 outbreak in this context.

Methods

The risk of COVID-19 outbreak in mass religious gathering was evaluated by using secondary COVID-19 cases and reproductive numbers. The preparedness of a series of NPIs for preventing COVID-19 outbreak in mass religious gathering was then assessed by using a density-dependent model. This approach was first illustrated by the Mazu Pilgrimage in Taiwan and validated by using the COVID-19 outbreak in the Shincheonji Church of Jesus (SCJ) religious gathering in South Korea.

Results

Through the strict implementation of 80% NPIs in the Mazu Pilgrimage, the number of secondary cases can be substantially reduced from 1508 (95% CI: 900–2176) to 294 (95% CI: 169–420) with the reproductive number (R) significantly below one (0.54, 95% CI: 0.31–0.78), indicating an effective containment of outbreak. The expected number of secondary COVID-19 cases in the SCJ gathering was estimated as 232 (basic reproductive number (R0) = 6.02) and 579 (R0 = 2.50) for the first and second outbreak, respectively, with a total expected cases (833) close to the observed data on high infection of COVID-19 cases (887, R0 = 3.00).

Conclusion

We provided the evidence on the preparedness of NPIs for preventing COVID-19 outbreak in the context of mass religious gathering by using a density-dependent model.

Keywords: Non-pharmaceutical intervention, COVID-19, Mass gathering, Religious activity

Introduction

Containment measures stemming from the principle of NPIs plays a major role for the prevention of outbreak during the incipient stage of the emerging disease.1, 2, 3 This is especially true for highly contagious disease when effective pharmaceutical interventions are not yet available, which is the situation for early COVID-19 pandemic.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 The rationale for applying NPIs lies in the mechanism of transmission for infectious disease captured by basic reproductive number, R0.10 An infectious process involved with two components: the contact between susceptible and infectives and the transmission of the disease with certain probability. This two-step process should take place during the infectious period of the infectives for an effective transmission to occur. Following this rationale, the main purpose of NPIs is thus to reduce the contact rate by which the transmission of disease can be attenuated.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 The policy of setting restriction on mass gathering including closure of school, cancelling activities such as exhibitions and conferences with attendances reaching a predefined limit, and religious activities is one of the realizations of NPIs by which the contact rate can be reduced and the clustering event can be prevented.17, 18, 19, 20

Among the types of mass gathering associated with increased risk of COVID-19 outbreaks, the balance between the spiritual roles of religious activities in communities and its risk of clustered COVID-19 cases have incurred vigorous debate on whether the religious gathering should be suspended, at least temporarily, as one of the social distancing measures to prevent or mitigate regional epidemic.18 , 21, 22, 23, 24 In the early outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, several clustered transmissions of SARS-CoV-2 in mass religious gatherings occurred worldwide.21 , 23, 24, 25 Followed by the clustered COVID-19 cases associated with religious activities, regional epidemics were reported.21 , 23 The early regional COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu, South Korea is one of such an event.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 After the cluster of COVID-19 cases association with the Shincheonji Church of Jesus (SCJ) mass religious gathering in Daegu, the confirm cases of South Korea have increased from 30 to more than 8000 in March.27 The soaring COVID-19 cases accelerated substantially by the SCJ mass religious gathering in South Korea have underscored the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in such a scenario.

Due to its characteristics of attracting massive attendants and close contacts during a substantial period, the mass religious gathering has often been postponed or canceled during COVID-19 pandemic.17 , 18 , 21 , 33 However, the efficacy of such a strict measure in preventing COVID-19 spread has not been assessed and quantified. Furthermore, with the ebb of COVID-19 pandemic, some of the mass gathering events including religious activities may return with daily life in post-pandemic era. The assessment on the risk of clustered transmission and the NPIs preparedness are imperative for allowing its engagement and the implementation of acceptable and feasible preventive measures. Although it is intuitive to implement the NPIs to curb the epidemic curve, its effectiveness has been barely addressed in the context of its implementation.19 , 20 , 33 Furthermore, given the variety and complexity in the activities involved in mass gathering, it calls for a specific and evidence-based guidance for the type of social distancing measures that should be taken and the scale of the restrictions that should be implemented. This is especially true for the recommendations for mass gathering involved with religious events, which often have great importance on both societal and religious aspects.

We thus aimed to assess the risk of disease spread in public gathering event by making use of the long standing and well established mass religious gathering of Mazu Pilgrimage in Taiwan.34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 The extended duration with complex contents of the entire itinerary of Mazu Pilgrimage provide a good chance to look into the efficacy and the preparedness of a series of NPIs in preventing the transmission of disease based on the current scenario of COVID-19 epidemic profile. We further assessed the scale of NPIs required to contain the COVID-19 outbreak for the SCJ religious gathering in South Korea based on the proposed framework.

Material and methods

Mazu Pilgrimage

Mazu is the sea goddess and one of the main religion and ideology in southeast coast of China and Taiwan since 18th century.34 more than 870 temples are dedicated to the worship for Mazu in Taiwan.37 To celebrate the birthday of Mazu in the third month of the Chinese lunar calendar (around April), temples in Taiwan hold religious activities during this period. The Mazu pilgrimage in Dajia, Taiwan is one of the largest of celebrations.37 , 39 This annual mass religious gathering set off from the home temple of Zhenlan in Dajia district located in central part of Taiwan with the route of the nine-day pilgrimage following the path of early immigrants to Taiwan.37 , 39 In addition to the pilgrimage brigades organized by the temple, numerous congregations and devotees will participate in the pilgrimage and attend the parade and ritual activities.37 , 39 , 40 With the outbreak of COVID-19, this classical mass religious gathering involved with the crowds and long exposure period have raised the concern over the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission.38

The evaluation on the risk of COVID-19 transmission in Mazu Pilgrimage was started from the estimation on the imported infectives among the travelers from China. The proportion of potential infectives imported from China to Taiwan can be derived by using positive rate among passengers traveled from China to Taiwan in the 14-day period, namely 5–18 of March, with the consideration of incubation and transmission period learned from early epidemic.18 The number of passengers traveled from China to Taiwan in 14 days prior to Mazu Pilgrimage was around 90,000 (Table S1).34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 The number of infectives that may attend Mazu Pilgrimage can be calculated by using this figure weighted by the age-specific proportion of the activity reported in previous studies. Due to the policy of fever screening implemented in the airport of Taiwan, subjects with body temperature higher than 37.6 Celsius degree will be isolated and tested for SARS-CoV-241 without having the chance of attending Mazu Pilgrimage.

External application to the outbreak of SCJ religion gathering in Korea

The outbreak associated with the SCJ religious gathering was initiated by the identification of a member of religious group as a pneumonia case on Feb 17, 2020. This index case showed typical COVID-19 symptoms on February 9 and attended the SCJ religious gathering comprising more than one thousand members regularly during the infectious period in February. Following the identification of this COVID-19 case, an extensive surveillance with testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection was performed for members of this religious group, which revealed the travel history of a group of SCJ members around the epicenter of Wuhan for religious activity since December, 2019 when the spread of SARS-CoV-2 had already taken place in several communities of Wuhan.28, 29, 30, 31, 32

Fig. 1 illustrates the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the SCJ religious gathering followed by the introduction of COVID-19 cases stemming from early cases imported from Wuhan. According to the registered data,42 , 43 as of Feb 6 there were a total of 23 COVID-19 cases in South Korea possibly imported from the SCJ religious group infected in Wuhan, China. Making allowance for a 14-day incubation period in the early stage of outbreak, these cases were infected and imported to South Korea around January 20. The COVID-19 epidemics in the SCJ mass religious gathering can propagate due to the lack of social distancing and NPIs and give rise to the second wave of outbreak. The propagation of COVID-19 following the introduction of these initial cases was estimated on the basis of the basic reproductive number of 1.7 of Wuhan (accompanying article of this special issue) with a generation time of 14 days, which yielded 76 initial cases during one month and further gave rise two waves of transmission from Feb 11 to 17 and Feb 18 to 24 with 833 total confirmed cases.43

Figure 1.

COVID-19 outbreak in the scenario of the SCJ religious gathering in South Korea.

Based on the information on the scenario of the mass SCJ religious gathering and the associated COVDI-19 cases, we extend the household transmission model to develop a density-dependent method transmission model of SARS-CoV-2 for estimating the close contact rate in mass religious gathering delineated the following method section.

NPIs preparedness required to contain COVID-19 outbreak in mass religious gathering

Mazu Pilgrimage

Fig. 2 (a) shows the risk of COVID-19 transmission in mass gatherings without NPIs. White spot represents susceptible subjects and red spot stands for infectives. The orange circle is the range of close contact with the radius of 1.13 m with the area covering 4 m2 while the blue circle is the range with doubled radius (2.26 m) covering the 16 m2. Given the existence of infectives in this 4 m2 range, close contact with infectives for attendants occurs and the group covered by the orange circle is thus at risk of being infected. The more the number of infectives within this range, the higher the chance of being infected. The crowdedness reflected by the number of attendants covered by the orange circle also have effect on the extent of risk population.

Figure 2.

Concept of containing the speared of COVID-19 in mass gathering with NPIs. (a) Without NPIs. (b) Social distancing. (c) Fever screening. (d) Sequestration for high-risk subjects. (e) Social distancing and NPIs of fever screen and sequestration for high risk subjects.

The determinants for disease transmission thus include the population density (white spots) and the infectives density (red spots) given the 4 m2 range (orange circle). Under this context, three types of NPIs including attendance restriction, fever screening, and sequestration for attendants with elevated risk, can be implemented during the mass religious gathering to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission. The concept of these NPIs and their mechanisms on reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission are illustrated in Fig. 2 and detailed as follows.

Social distancing

Fig. 2 (b) shows the effect of attendant restriction on reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission. By reducing the attendants of a mass gathering event, the crowdedness is reduced so as to reduce the risk of infection (covered by orange circle). For infectives, similar condition applies. The reduction in the total number of attendants thus contributes to bring down the contact rate between susceptibles and infectives and ultimately results in a lower basic reproductive number due to mass gathering.

Fever screening

Fig. 2 (c) shows the effect of fever screening in reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Based on current evidence, around half of infectives present with the symptom of fever (body temperature higher than 37.6 Celsius degree). The measure of body temperature is thus plays an important role for the identification of potential infectives.47 , 48 Following this rationale, the number of infectives can be reduced through fever screening to reduce of force of COVID-19 transmission in mass gathering events.

Sequestration for high-risk attendants

The risk of being a potential infectives for the attendants can be assessed by querying for contact history and travel history. The attendants of mass gathering with positive answers on these questions thus have a higher risk and can be separated from attendants without these risk exposures to reduce the possibility of COVID-19 transmission. Fig. 2 (d) shows the effect of this sequestration procedure.

The NPIs mentioned above can be combined with other NPIs to maximize the effect in reducing the COVID-19 transmission during mass gathering events. Fig. 2 (e) shows this implication. Through the integrated implementation of social distancing measures, both the densities of population and infectives are reduced due to restriction of attendants and fever screening. The risk of transmission was further reduced through the sequestration of attendants with elevated risk. Note that the combine use of self-protection measures such as wearing mask and hand hygiene can further reduce the transmission probability.

Based on these concepts, a series of NPIs can be implemented during the mass religious gathering of Mazu Pilgrimage to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission. These NPIs contribute mainly to a lower contact rate which can be augmented with the use of self-protection measures.

External application to SCJ religious gathering

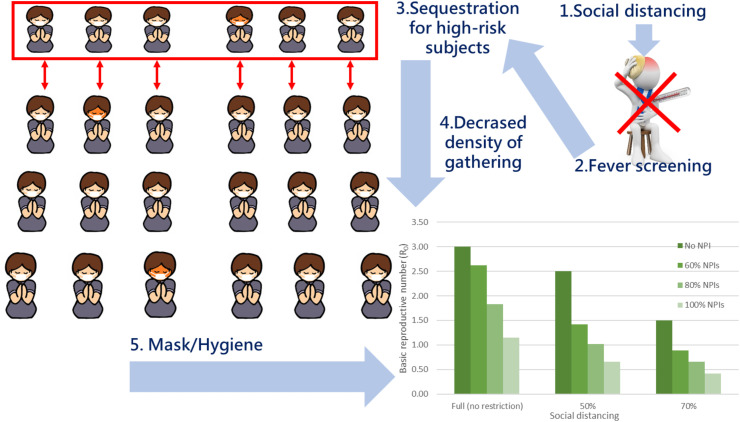

Based on the proposed density-dependent model, the scale of NPIs required for containing the COVID-19 outbreak in the SCJ mass religious gathering was assessed. The scenario for the assessment was referred to the COVID-19 outbreak associated with SCJ religious gatherings in South Korea following the cases imported from the epicenter of Wuhan in January with persistent transmission in mass religious gathering events up to February 24.28, 29, 30, 31, 32 Fig. 3 shows the steps for the implementation of NPIs for containing SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the SCJ religious gathering. The social distancing measures can first be implemented by reducing the attendants of service. The fever screening can prevent symptomatic COVID-19 cases from attending the service. Subjects with high–risk profiles such as the history of contact or exposure to suspected cases can be sequestrated form other attendants to reduce the risk of transmission. These approach can thus reduce the density of religious gathering. The use of mask and hygiene measures can further reduce the transmission probability. Following the framework depicted in Fig. 3, the effectiveness of social distancing and NPIs with different scales in implementation for containing the SCJ COVID-19 outbreak were assessed by using the density-dependent COVID-19 transmission model.

Figure 3.

Social distancing and NPIs for preventing COVID-19 outbreak in the SCJ religious gathering in South Korea.

Statistical analysis

To assess the preparedness of NPIs for preventing COVID-19 spreading during the Mazu Pilgrimage and mass SCJ gathering we applied the density-dependent close contact measurement for the types of involved activities following the dynamic of infectious disease transmission guided by reproductive number (R). By using the density approach with a defined range of close contact, the main concern for the drive of disease transmission during mass gathering can be captured. The development on methods for assessing the transmission force for the Mazu Pilgrimage following by the validation using SCJ gathering are detailed as follows.

Population density during the Mazu Pilgrimage

Regarding the scenario of Mazu pilgrimage, Table 1 summarizes the itinerary during the 9-day period of mass religious gathering. The activities can be categorized into four types: parade, dinning, sleeping, and religious ritual, according to the information provided from the official website with the cross-validation by using the web-based information and the reports of previous studies,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 , 43 the duration and the number of attendants of each type of activity can be obtained, which was further used for the derivation of the population density.44

Table 1.

Itinerary of a classical mass religious gathering of Mazu Pilgrimage in Taiwan.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

| Activity | Durationa (hours) | Estimated number of attendants | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parade | 144 | 2,000,000 | During the 9-day activity, a total 347 km route will be covered |

| Dining | 8 | 15,000 | The lunch and dinner will be provided by temples and believers |

| Sleeping | 24 | 7000 | The area for sleeping will be provided by temple and local institutes such as school and administrative offices |

| Religious ritual | 40 | 28,000 | Ten activities hold in temple will be included as part of the pilgrim |

Total duration of the Mazu pilgrimage: 216 hours.

As a measurement of close contact for the transmission to occur, the population density was further transformed into the measurement of 4 m2 unit. Based on this close-contact unite, we further developed a unit-day measurement refereeing to the duration of activities listed in Table 1 to take into account the exposure period due to attending each type of activity (Table S2). On the basis of this information, the density of infectives for each type of activities can be calculated for the Mazu Pilgrimage.

Transmission probability of close contact

The probability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission due to the close contact in mass religious gatherings was derived by using the empirical data with household information reported by the Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC)5 which was also cross validated from the web-based information for the household size. The probability of COVID-19 transmission in the context of household contact with the saturated transmission model (Greenwood transmission model45 , 46) was applied. Following the methodology used in the accompanying article of this special issue, we applied the household transmission model to estimating the transmission probability with close contact in 4 m2 unit during religious gathering.

Estimating the secondary cases associated with mass religious gathering

Following the principle of basic reproductive number in conjunction with the scenarios of Mazu Pilgrimage with a variety of types of mass gathering, the secondary cases resulting from the effective contact between infectives and susceptibles can be derived. Specifically, given the type of mass gathering (parade, dinning, sleeping, and religious ritual), the contact rate is proportion to the density of susceptibles and infectives which were both derived from the information summarized above. To take into account the time scale for each type of close contact between infectives and susceptibles, the contact density was further weighted by the 4 m2 unit-day during the entire itinerary of Mazu Pilgrimage. Given a specified type of activity, the derivation for the number of secondary cases (r s) can then be represented as follows.

| rs = ds⨯di⨯utc⨯p, |

where d s is the density of susceptibles and d i is density of infectives calculated as above. ut c represents the total number of close contact unite (the 4 m2 range) occurred throughout the itinerary of Mazu Pilgrimage. For the derivation of secondary cases resulting from a type of activity, the effective contact was estimated by incorporating the daily transmission probability (p). The basic reproductive number was derived by using the ratio of the secondary cases to the initial infectives introduced into the activities of mass religious gathering. A Bayesian MCMC method was adopted for the derivation of 95% credible intervals for the estimated results on the number of secondary cases and the basic reproductive numbers.

External validation by the SCJ gathering

Based on the available information, the SCJ mass religious gathering involved as much as 2000 members hold in modern buildings for service activity. We thus assumed the area of 496 m2 (150 pyeong in South Korea unit of measurement) as the area of mass gathering, which can be packed as much as 1000 members. Under this scenario, around 8 subjects will be packed in the area of 4 m2. Two such sites for the religious gathering sites were used in assessing the SARS-CoV-2 spreading during SCJ religious activities. The duration of contact in the SCJ gathering were estimated on the basis of 6 services per week with the duration of 4 h for each service, which gives the contact duration of one day per week.

Following the density-dependent method detailed above in conjunction with the 4 m2 unit measurement of close contact and the total number of infectives that may attend the SCJ mass religious gathering, the density of infectives for the SCJ gathering was estimated. The proposed method was then validated by comparing the expected number of COVID-19 cases and that was reported from registry data.42 , 43

Result

Transmission probability of close contact during mass religious gathering

The probability of COVID-19 transmission with the saturated transmission model (Greenwood transmission model45 , 46) was estimated as 33.5 (95% CI: 17.8–49.3%). By applying an exponential transmission function with a 7-day infectious period, the daily transmission probability was thus estimated as 5.84 (95% CI: 2.45–9.22%).

Estimating the secondary cases and reproductive number in mass religious gathering without NPIs

Mazu Pilgrimage

After application of close contact probability to population density for deriving secondary cases, Table 2 shows the estimated results on the number of secondary cases resulting from the close contacts during the mass religious gathering of Mazu Pilgrimage. Table 2 also lists the estimated results on the density of susceptibles and infectives measured by a 4 m2 unit-day for each type of activities in the Mazu pilgrimage. The first column of Table 2 lists the densities of close contact based on the 4 m2 range and the number of attendants. The average number of attendants within the 4 m2 range were estimated as 2.9, 10, 2, and 11.6 for the activity of parade, dinning, sleeping, and religious ritual, respectively.

Table 2.

Estimated number of secondary case results from the mass religious gathering.

| Activity | Population Density (per 4 m2) | Infective Density (per 4 m2) | Total unit-daya | Transmission probability (%) | Estimated number of secondary cases during the MZ pilgrimage |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | 95% CI | |||||

| Parade | 2.9 | 0.025 | 173,500 | 5.84 | 728 | (435,1051) |

| Dinning | 10 | 0.36 | 500 | 105 | (63,152) | |

| Sleeping | 2 | 0.15 | 3500 | 63 | (38,91) | |

| Religious ritual |

11.6 |

0.22 |

4002 |

611 |

(365,882) |

|

| Overall | – | – | – | – | 1508 | (900,2176) |

Basic reproductive number: 2.79 (1.66–4.02).

Based on the COVID-19 epidemic during the early period before the Wuhan lockdown, the basic reproductive number was estimated as 1.7. The positive rate during the period was estimated as 6% given the case fatality rate of 8.5% derived from published article.47 This figure, together with the estimated number of 92,500 travelers from China (Table S1) with the consideration of age distribution of attendants (Table S3) and the potential of disease transmission in the 14-day period, gives the total of 540 infectives that may attend the Mazu Pilgrimage. This number of infectives attending the Mazu Pilgrimage results in the infective density per 4 m2 of 0.025, 0.36, 0.15, and 0.22 for the activity of parade, dinning, sleeping, and religious ritual, respectively (Table 2, Second column).

Summarizing the components of contact between infectives and susceptibles, the total unit-day of close contact, and the probability of COVID-19 transmission due to close contact (5.84% per day) by using the density-dependent transmission model, the estimated number of secondary cases resulting from parade, dinning, sleeping, and religious ritual were 728 (95% CI: 435–1051), 105 (95% CI: 63–152), 63 (95% CI: 38–91), and 611 (95% CI: 365–882), respectively. The total secondary cases during the 9-day itinerary of Mazu Pilgrimage was thus estimated as 1508 (95% CI: 900–2176), which gives the basic reproductive number of 2.79 (95% CI: 1.66–4.02).

External applications to mass SCJ gathering

Following the household transmission probability estimated from Taiwan, we estimated the close contact probability in the SCJ gathering by fitting the population density and dynamic susceptibles (decreasing with time) with 883 COVID-19 among 1016 members receiving RT-PCR test based on the non-significant (χ 2 = 3.29, P = 0.07) difference between the expected (887) and observed (833) COVID-19 cases in the SCJ outbreak. The average transmission probability (in day) due to close contact was 19.4% (95% CI: 17.5–21.3, Fig. 1), which was around three times higher than that based on close contact of household transmission in Taiwan.

Based on 887 secondary cases (95% CI: 824–947), the overall basic reproductive number was estimated as 3.00 (95% CI: 2.97–3.02). By dividing the period into two weeks, the number of secondary case was 232 (95% CI: 210–255) and 579 (95% CI: 539–617) with the basic reproductive number of 6.02 (95% CI: 5.44–6.62) and 2.50 (95% CI: 2.42–2.57) for the first (February 11 to February 17), and second (February 18 to February 24) wave of the SCJ outbreak, respectively (Fig. 1).

NPIs preparedness for preventing COVID-19 outbreak in Mazu Pilgrimage

Based on the estimated results on the total of 1508 secondary cases resulting from the Mazu Pilgrimage, we explore the efficacy on the implementation of a series of NPIs including social distancing, fever screening, sequestration for high risk attendants, and personal protective measures in reducing the secondary cases and also the reproductive number with the results shown in Fig. 4 and Table S4.

Figure 4.

Estimated results on basic reproductive number (R0) by scale of social distancing and NPIs. (a) Social distancing. (b) Social distancing and NPIs.

Effectiveness of social distancing

By the social distancing measure of reducing the number of attendants, the density of attendants is decreased so as the number of subjects exposed to infectives in the 4 m2 range of close contact. With the attendants reducing as much as 40%, the number of secondary cases were decreased by 526 (95% CI: -228-1250), from 1508 to 975 (95% CI: 594–1401, Table S4). Fig. 4 (a) shows the corresponding results on the reproductive number, which decreased from 2.79 to 1.80 (95% CI: 1.10–2.59). For the scenario with 10% reduction in attendant, the efficacy of this social distancing measure diminished with the reproductive number of 2.55 (95% CI: 1.55–3.66, Fig. 4 (a) and Table S4). Note that even at the scenario of reducing the attendant by 40%, the reproductive number is still larger than 1, indicating the outbreak of COVID-19 cannot be prevented by the social distancing measure.

Effectiveness of overall NPIs

For effective prevention of outbreak in Mazu pilgrimage, the social distancing can be incorporated with other NPIs. Fig. 4 (b) shows the estimated results of the preparedness of NPIs on the reproductive number in Mazu pilgrimage. Given a 30% social distancing, the combining use of other NPIs (fever screening, sequestration of high risk attendants, and waring mask) with the implementation scale of 60% can bring down the number of secondary cases from 1508 to 469 (95% CI: 286–681, Table S4) and a reproductive number less than one (0.87, 95% CI: 0.53–1.26, Fig. 4 (b) and Table S4). The number of secondary cases averted was estimated as 1032 (95% CI: 375–1689). With the enhanced implementation of 80% NPIs, the secondary cases were estimated as 294 (95% CI: 169–420, Table S4) with the reproductive number of 0.54 (95% CI: 0.31–0.78, Fig. 4 (b) and Table S4). A total of 1208 (95% CI: 576–1850) secondary cases will be averted under this scale of implementation for NPIs. Note that given 30% social distancing, it still requires 80% NPIs to prevent COVID-19 outbreak in the Mazu pilgrimage (Fig. 4 (b) and Table S4).

Table S4 also lists the details on the effectiveness of each of the NPIs including fever screening, sequestrating high risk attendants, and the personal preventive measures of wearing mask to prevent COVID-19 outbreak in the mass religious gathering of Mazu pilgrimage. With the 100% implementation, the NPIs of fever screening, sequestration of high risk attendants, and waring mask will bring down the reproductive number to 1.40 (95% CI: 0.82–2.02), 0.74 (95% CI: 0.43–1.09), and 1.51 (95% CI: 0.87–2.22), respectively. These results suggest that the use of single NPI will not be able to prevent COVID-19 outbreak in the Mazu pilgrimage.

Estimated effectiveness of NPIs for containing the outbreak in SCJ mass religious gathering in South Korea

Based on this result, we were able to assess the social distancing and NPIs (Fig. 3) required for containing the SCJ outbreak. Fig. 5 shows the estimated results on the effectiveness of applying social distancing in conjunction with NPIs on the reproductive number. With a higher social distancing from none to 50% and 70%, the reproductive number can be reduced to 2.50 (95% CI: 2.36–2.60) and 1.50 (95% CI: 1.40–1.61), respectively (Fig. 5 and Table S5). To further bring down the reproductive number to less than one, the incorporation of other NPIs is required. Details on the estimated results on the reproductive number and COVID-19 cases associated with different scales of the implementation of NPIs were listed in Table S5.

Figure 5.

Estimated results of the NPIs on reproductive number required for containing the COVID-19 outbreak in the SCJ mass religious gathering in South Korea.

As a minimum requirement for keeping the reproductive number at one, 50% social distancing (reduce the attendants by 50%) and 80% NPIs (fever screening, sequestration of high-risk subjects, and wearing mask) should be implemented (R = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.87–1.17, Fig. 5 and Table S5) for the SCJ mass religious gathering. To contain the outbreak with certainty by maintaining a reproductive number less than one, a complete (100%) implementation of NPIs with 50% social distancing (R = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51–0.79) or 80% implementation of NPIs with 70% social distancing (R = 0.65, 95% CI; 0.56–0.75, Fig. 5 and Table S5) is required.

Discussion

For the safety of the engagement of mass religious gathering in the face of COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative to control the basic reproductive number lower than one so as to prevent COVID-19 outbreak. By using the narrative study to decompose the activities of Mazu Pilgrimage, we demonstrated that through the integrated social distancing approach including the restriction of attendants (30%), fever screening (60%), and sequestration of high risk attendants (60%) combining with the use of personal protective measures (60%), the number of secondary cases can be substantially reduced from 1508 to 469 with a basic reproductive number of 0.87. The preparedness assessment for the Mazu pilgrimage shows a strict implementation of NPIs (80%) will be required to prevent the COVID-19 outbreak given a 30% social distancing.

Following the mechanism of disease transmission guided by basic reproductive number, we evaluated the effectiveness of a series of NPIs for reducing the number of secondary cases due to mass religious gathering events. The preparedness of NPIs for containing and preventing COVID-19 outbreak in mass religious gathering was assessed based on the Mazu pilgrimage and the SCJ religious gathering. For the SCJ mass religious gathering, the R0 was estimated as 3.00 (95% CI: 2.97–3.02). The implementation of 70% social distancing and 80% NPIs was required for containing the COVID-19 outbreak in the SCJ mass religious gathering with a reduced reproductive number of 0.65 (95% CI: 0.56–0.75).

During the first pandemic period of COVID-19 up to Jun, 2020, a series of NPIs including social distancing and fever screening, and the personal protective measures such as wearing mask have been implemented in most of countries. One of the social distancing measures adopted by many countries in the early phase of COVID-19 is the closure of schools and day-care centers. The ban on mass gathering, especially for religious events was also announced in most of countries soon after a series of COVID-19 outbreaks associated with clustered events.21 , 33 , 49 The clustered outbreaks with large number of secondary cases had been reported in several mass religious gatherings and was associated with the amplification of COVID-19 pandemic in countries such as Iran, Korea, Malaysia, and USA.23 , 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 , 42 , 50, 51, 52

Although the physical contact between infectives and susceptibles can be reduced by the ban on mass religious gathering and the transmission force can be reduced to reach the aim of containing COVID-19 outbreak, these measures results in great impact in religious and societal aspect. Furthermore, the risk of COVID-19 transmission and the preparedness of NPIs required to prevent COVID-19 outbreak in the scenarios of mass religious gathering have not been quantified. By using the empirical report of the SCJ outbreak in South Korea.,27, 28, 29, 30 , 53, 54, 55 our results not only quantify the risk of COVID-19 spread in mass religious gathering but also provide insight into the preparedness of NPIs required to prevent the outbreak for the scenarios of Mazu pilgrimage in Taiwan.

Mazu Pilgrimage is one of the most important mass religious gathering in Taiwan which is held at annual basis. It involves a variety of activities including parade, dining, sleeping and religious ritual have mass gathering of people. Due to its highly integrated nature in terms of societal, cultural, religious, and economical aspect, such a mass religious gathering attracts millions of attendants during its well-designed nine-day course. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Mazu Pilgrimage was postponed under the consideration of the risk of clustered outbreak. Although the decision may contribute to the containment of COVID-19 outbreak in Taiwan, its efficacy has not been addressed. Furthermore, possible social distancing measures that may play the role for the sustained engagement of this important mass religious gathering have not yet had the chance to be explored.

Following these evidence, the assessment for the risk of outbreak should take place at the planning stage for the engagement of mass gathering with the consideration of types and density of close contact. Based on the risk level of outbreak indicated by the number of secondary cases and basic reproductive number, the scale and approaches of social distancing measures can then be implemented to avoid the clustered event of COVID-19 outbreak seen in mass gathering globally.18 The estimated results on the number of secondary cases can also shed light on the preparedness in medical capacity required to cope with the potential infectives resulting from a mass gathering, which should be part of the planning for mass gathering in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Note that the absolute medical needs indicated by the number of secondary cases can be overwhelming in relative to the local medical capacity even with a basic reproductive number lower than one. These two indicators thus provide a thorough guidance for the risk of outbreak which should be included in the planning of mass gathering event.

In conclusion, the proposed density-dependent approach with the consideration of the types and duration of close contact that may encountered in mass religious gathering provides a practical guidance for the assessment of the risk of COVID-19 transmission for mass gathering engagement. On the basis of this assessment, we demonstrated how to quantify the social distancing measures and the scale of implementation required for the containment of COVID-19 transmission in the examples of Mazu Pilgrimage and SCJ religious gathering.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2021.04.017.

Funding support

Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 109-2327-B-002-009).

Role of funder/sponsor

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Haug N., Geyrhofer L., Londei A., Dervic E., Desvars-Larrive A., Loreto V. Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(12):1303–1312. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.What is social distancing? CDC. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/social-distancing.html Available at:

- 3.Wikipedia Social distancing. wikipedia. 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_distancing Available at:

- 4.Kissler S.M., Tedijanto C., Goldstein E., Grad Y.H., Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368(6493):860–868. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CECC announces social distancing measures for COVID-19. Taiwan CDC. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/kM0jm-IqLwNBeT6chKk_wg?typeid=158 Available at:

- 6.Considerations relating to social distancing measures in response to COVID-19 – second update. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. ECDC Technical Report. 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/considerations-relating-social-distancing-measures-response-covid-19-second Available at:

- 7.Lewnard J.A., Lo N.C. Scientific and ethical basis for social-distancing interventions against COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6) doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30190-0. 30190-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Considerations for quarantine of individuals in the context of containment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19). World Health Organization. 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/considerations-relating-social-distancing-measures-response-covid-19-second Available at:

- 9.Wilder-Smith A., Chiew C.J., Lee V.J. Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):e102–e107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas J.C., Weber D.J. Oxford University Press; 2001. Epidemiologic methods for the study of infectious diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bondy S.J., Russell M.L., Laflèche J.M., Rea E. Quantifying the impact of community quarantine on SARS transmission in Ontario: estimation of secondary case count difference and number needed to quarantine. BMC Publ Health. 2009;9:488. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bootsma M.C., Ferguson N.M. The effect of public health measures on the 1918 influenza pandemic in U.S. cities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(18):7588–7593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611071104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatchett R.J., Mecher C.E., Lipsitch M. Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(18):7582–7587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610941104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson N.M., Cummings D.A., Cauchemez S., Fraser C., Riley S., Meeyai A. Strategies for containing an emerging influenza pandemic in Southeast Asia. Nature. 2005;437(7056):209–214. doi: 10.1038/nature04017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jefferson T., Foxlee R., Del Mar C., Dooley L., Ferroni E., Hewak B. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;336(7635):77–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39393.510347.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glass R.J., Glass L.M., Beyeler W.E., Min H.J. Targeted social distancing design for pandemic influenza. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(11):1671–1681. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebrahim S.H., Memish Z.A. COVID-19 - the role of mass gatherings. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020; Mar 9:101617. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCloskey B., Zumla A., Ippolito G., Blumberg L., Arbon P., Cicero A. Mass gathering events and reducing further global spread of COVID-19: a political and public health dilemma. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1096–1099. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30681-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell D., Nicoll A., Fukuda K., Horby P., Monto A., Hayden F. Non-pharmaceutical interventions for pandemic influenza, national and community measures. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(1):88–94. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.051371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guidelines for the use of non-pharmaceutical measures to delay and mitigate the impact of 2019-nCoV. ECDC Technical Report; 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/guidelines-use-non-pharmaceutical-measures-delay-and-mitigate-impact-2019-ncov Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yezli S., Khan A. COVID-19 pandemic: it is time to temporarily close places of worship and to suspend religious gatherings. J Trav Med. 2021;28(2) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa065. taaa065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wildman W.J., Bulbulia J., Sosis R., Schjoedt U. Religion and the COVID-19 pandemic. Relig Brain Behav. 2020;10(2):115–117. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quadri S.A. COVID-19 and religious congregations: implications for spread of novel pathogens. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:219–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kye B., Hwang S.J. Social trust in the midst of pandemic crisis: implications from COVID-19 of South Korea. Res Soc Stratif Mobil. 2020;68:100523. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peck K.R. Early diagnosis and rapid isolation: response to COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(7):805–807. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S.W., Yuh W.T., Yang J.M., Cho Y.S., Yoo I.K., Koh H.Y. Nationwide results of COVID-19 contact tracing in South Korea: individual participant data from an epidemiological survey. JMIR Med Inform. 2020;8(8) doi: 10.2196/20992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang Y.J. Characteristics of the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea from the mass infection perspective. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020;53(3):168–170. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.20.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H.J., Hwang H.S., Choi Y.H., Song H.Y., Park J.S., Yun C.Y. The delay in confirming COVID-19 cases linked to a religious group in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020;53(3):164–167. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.20.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J.Y., Hong S.W., Hyun M., Park J.S., Lee J.H., Suh Y.S. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in Daegu, South Korea. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeong E., Hagose M., Jung H., Ki M., Flahault A. Understanding South Korea's response to the COVID-19 outbreak: a real-time analysis. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(24):9571. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang M.C., Baek J.H., Park D. Lessons from South Korea regarding the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak. Healthcare. 2020;8(3):229. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8030229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S., Jeong Y.D., Byun J.H., Cho G., Park A., Jung J.H. Evaluation of COVID-19 epidemic outbreak caused by temporal contact-increase in South Korea. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:454–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S., Yang J., Yang W., Wang C., Bärnighausen T. COVID-19 control in China during mass population movements at New Year. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):764–766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang H., editor. Multiple Religious and national identities Mazu Pilgrimages across the Taiwan Strait after 1987. Religion and nationalism in Chinese societies. 2017. pp. 373–396. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang C.L., Chu C.H. The expanding of Mazu belief in Taiwan-A analysis on the 2009 Tachia Mazu go around boundary ceremony. J Data Anal. 2012;7(1):107–127. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong M.H. Mazu mania: free food, great parties. Wait, this is a religious festival? CNN. 2013. http://travel.cnn.com/taiwan-mazu-religious-festival-pilgrimage-226351/ Available at:

- 37.Religious activities. Tourism bureau, Republic of China (taiwan) 2019. https://eng.taiwan.net.tw/m1.aspx?sNo=0002022 Available at:

- 38.Wu L.Y. Taipei Times; 2020. Virus outbreak: Dajia Mazu pilgrimage going ahead.http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2020/02/27/2003731690 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazu Pilgrimage from zhenlan temple, Dajia. Taiwan religious culture map. 2020. https://www.taiwangods.com/html/landscape_en/1_0011.aspx?i=39 Available at:

- 40.The Mazu pilgrimage experience. Taiwan scene. 2019. https://taiwan-scene.com/the-mazu-pilgrimage-experience/ Available at:

- 41.Hsieh V.C. Putting resiliency of a health system to the test: COVID-19 in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119(4):884–885. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korean Society of Infectious Diseases Report on the epidemiological features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in the Republic of Korea from January 19 to March 2, 2020. J Kor Med Sci. 2020;35(10):e112. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Central Disease Control Headquarters, Korea Coronavirus disease-19, Republic of Korea. 2020. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en?fbclid=IwAR2xJtezxurweDLkRRTuQFBpd-FxK-onIoC9cpBsNS0gG3UC-aPyzeetQ0g Available at:

- 44.Wikipedia. Jacobs's method. Wikipedia. 2020. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crowd_counting#Jacobs.27s_Method Available at:

- 45.Norman T.J. Bailey the use of chain-binomials with a variable chance of infection for the analysis of intra-household epidemics. Biometrika. 1953;40(3/4):279–286. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenwood M. On the statistical measure of infectiousness. J Hyg. 1931;31(3):336-351. doi: 10.1017/s002217240001086x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng H.Y., Li S.Y., Yang C.H. Initial rapid and proactive response for the COVID-19 outbreak - taiwan's experience. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119(4):771–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chinazzi M., Davis J.T., Ajelli M., Gioannini C., Litvinova M., Merler S. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wikipedia. COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. Wikipedia. 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic_in_Iran Available at:

- 51.Hashim H.T., Babar M.S., Essar M.Y., Ramadhan M.A., Ahmad S. The hajj and COVID-19: how the pandemic shaped the world's largest religious gathering. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021 doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Badshah S.L., Ullah A. Spread of coronavirus disease-19 among devotees during religious congregations. Ann Thorac Med. 2020;15(3):105. doi: 10.4103/atm.ATM_162_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ha K.M. A lesson learned from the outbreak of COVID-19 in Korea. Indian J Microbiol. 2020;60(3):1–2. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00882-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yi J., Lee W. Pandemic nationalism in South Korea. Society. 2020;17:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12115-020-00509-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarkar S. Religious discrimination is hindering the covid-19 response. BMJ. 2020;369:m2280. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.