Abstract

Background:

Thymoquinone (TQ) has potential anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and anticancer effects but its clinical use is limited by its low solubility, poor bioavailability and rapid clearance.

Aim:

To enhance systemic bioavailability and tumor-specific toxicity of TQ.

Materials & methods:

Cationic liposomal formulation of TQ (D1T) was prepared via ethanol injection method and their physicochemical properties, anticancer effects in orthotopic xenograft pancreatic tumor model and pharmacokinetic behavior of D1T relative to TQ were evaluated.

Results:

D1T showed prominent inhibition of pancreatic tumor progression, significantly greater in vivo absorption, approximately 1.5-fold higher plasma concentration, higher bioavailability, reduced volume of distribution and improved clearance relative to TQ.

Conclusion:

Encapsulation of TQ in cationic liposomal formulation enhanced its bioavailability and anticancer efficacy against xenograft pancreatic tumor.

Keywords: : cationic lipid, liposomes, pancreatic cancer, pharmacokinetic evaluation, thymoquinone

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PC) is an extremely aggressive cancer demonstrating early spread of micro-metastatic disease, its invasion to nearby organs, poor prognosis, high drug resistance and remains asymptomatic until advanced stages of progression [1]. The incidence of PC has increased over 49% in the last two decades, projecting it to be the major root of cancer-related deaths by 2030 [2]. Despite the advances in cancer chemotherapeutics, there has been a rise in death rate of PC patients by 0.3% per year [3] signifying the imperative necessity for better therapeutic modalities.

Thymoquinone (TQ), a bioactive phytoconstituent of Nigella sativa oil, possesses promising therapeutic applications such as anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and anticancer effects [4–7]. TQ modulates multiple signaling pathways involved in cancer progression and mediates its anticancer therapeutic effects [8]. Significant inhibition of viability and apoptotic activation was observed in lung, liver, colon, melanoma and breast cancer cell lines treated with TQ [9]. TQ significantly reduced PC tumor size in 67% of tumor xenografts in vivo by promoting H4 acetylation and inhibition of HDAC expression [10]. These multiple potential cancer molecular targets establish TQ as a promising antitumor agent to prevent cancer recurrence. However, the systemic use of TQ presents an arduous challenge owing to its low solubility, nonpolar nature, poor bioavailability and clearance [11]. Odeh et al. [12] first described the encapsulation of TQ in a neutral lipid-based liposome to enhance the stability, solubility, bioavailability and decrease the nonspecific toxicity, however, the cancer-specific toxicity of neutral lipid-based liposomal TQ was relatively lesser than free TQ in breast cancer cells.

Cationic lipid-based liposomes offer more promising strategy owing to their better fusogenicity, positive surface charge and inherent advantage of tumor targeting [13] by binding to the irregular anionic domains present on the luminal plasma membrane of tumor endothelial cells [14]. Lohr et al. [15] demonstrated the selective delivery of a cationic liposomal formulation carrying paclitaxel to the activated intratumoral endothelial cells in animal models of orthotopic PC with an acceptable safety profile and antitumor activity in Phase I clinical trials. Cationic lipid-based ligands showed better therapeutic activity compared with unmodified ligands and inhibited cancer cell proliferation, induced apoptosis, reduced tumor angiogenesis and growth in melanoma tumor model [16–18]. In the past, we have demonstrated that cationic lipid-associated drug or both gene and drug delivery systems show better therapeutic activity in mice pancreatic tumor models [19,20]. Previously, we have developed three cationic lipids – asymmetric, twin stearyl chain saturated lipid, an asymmetric stearyl and oleyl chain containing lipid and symmetric, twin oleyl chain unsaturated lipid [21]. Among these cationic lipid-associated liposomal formulations, the formulation carrying cationic lipids with asymmetric aliphatic chains (i.e., one, oleyl and the other, stearyl-chain) showed relatively better cellular localization and exhibited better in vivo cytotoxic and therapeutic profiling of drug/gene cargo than other formulations [22,23]. Herein, we demonstrate the comparative in vivo efficacy of TQ-associated formulation carrying cationic lipids with asymmetric aliphatic chains and pristine TQ in terms of enhanced therapeutic and pharmacokinetic (PK) properties in mouse pancreatic tumor model.

Materials & methods

Cell lines

PANC-1, A549 and B16F10 cell lines were acquired from the National Centre for Cell Science (Pune, India). These cells were preserved in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 mg/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. Cells were grown at 37°C in DMEM with 10% FBS in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity (RH). All the reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA unless otherwise stated. Antibiotics were obtained from HiMedia, India.

Synthesis of D1 lipid

The asymmetric cationic lipid D1 was synthesized according to Supplementary Figure 1, following a previously published protocol [21]. Briefly, in a 50 ml round bottom flask, octacecyl amine (500 mg, 1.855 mmol, 1 equiv), 1-bromooctadecane (615 mg, 1.844 mmol, 1 equiv) and potassium carbonate (1.25 g, 9.044 mmol, 5 equiv) were dissolved in ethyl acetate. The reaction mixture was stirred at reflex condition for 12 h. The K2CO3 was filtered by using Whatman filter paper, followed by reaction mixture was concentrated in rotary evaporator. The resulting secondary amine was purified by 60–120 silica gel column chromatography (Methanol:Chloroform = 1:99). The product is then recrystallized by using ethyl acetate, resultant product was a white solid 886 mg, 91% yield Rf = 0.5, 5:95 methanol:chloroform, v/v). The secondary amine, (0.5 g, 1.9 mmol, 1 equiv.), potassium carbonate (0.5 g, 7.6 mmol, 1 equiv), were dissolved in chloroethanol as a solvent in 50 ml round bottom flask. The reaction mixture was stirred at reflex condition for 12 h. The K2CO3 was filtered by using Whatman filter paper, followed by reaction mixture was concentrated in rotary evaporator. The resulting mixture was purified by 60–120 silica gel column chromatography (Methanol:Chloroform = 4:96). The product was then recrystallized by using ethyl acetate; the resulting product was a 98% pure white solid (512 mg, 87% yield, Rf = 0.2, 5:95 methanol: chloroform, v/v).

Spectral values of D1 lipid

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ5.52 (s, 2H), 5.42 – 5.25 (m, 2H), 4.10 (m, 4H), 3.72 (t, 4H), 3.34 (m, 4H), 2.00 (m, 4H), 1.65–1.22 (m, 56H), 0.88 (t, 6H) ppm (Supplementary Figure 2A).

13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 130.13, 129.64, 61.35, 60.20, 55.88, 31.97, 29.75, 29.41, 29.19, 27.21, 26.36, 22.73, 22.10, 14.17 ppm (Supplementary Figure 2B).

ESI-MS: calculated mass 608.62 (for C40H82NO2+) found: 608.63 (M+) (Supplementary Figure 2C).

HRMS: 608.6290, C40H82NO2 = 608.6340 (calculated), RDBE = 0.5 (Supplementary Figure 2D).

Preparation of liposomal formulations

A 1 mM (with respect to lipid constituent) D1, D1T, D and DT liposomes were prepared with 1:1, 1:1:1, 1:1 and 1:1:1 mole ratios of asymmetric cationic lipid: cholesterol (D1), asymmetric cationic lipid:cholesterol:TQ (D1T), DOPC:cholesterol (D) and DOPC:cholesterol:thymoquinone (DT), respectively, as well as 0.05 mole ratio of fluorescent rhodamine-phosphoethanolamine (Rh-PE), were used to prepare Rh-PE labeled liposomes. The components in the appropriate mole ratios were dissolved in chloroform (0.5 ml) in a glass vial. The solvent was removed using thin flow of moisture-free nitrogen gas and the dried lipid film was further dried for removal of any minute residual chloroform under high vacuum for 4 h. The obtained dried film was again dissolved in 50 μl of ethanol and the ethanolic lipid solution was dispersed in 950 μl autoclaved MilliQ water resulting in the formation of bilayer vesicles.

Zeta potential & hydrodynamic diameter measurements

The hydrodynamic diameter and surface charges (ζ potentials) of D1, D1T, D and DT liposomal formulations (at 1:50 dilutions) were measured by photon correlation spectroscopy (dynamic light scattering [DLS]) using an Anton-PaarLitesizer 500 instrument. Each experiment was carried out in triplicates. For studying the stability of the liposomes in autoclaved Milli-Q water and 10% serum, liposomes were incubated in water and in 10% FBS and size measurements were carried out to check for consistency upto 150 days and 72 h, respectively.

Transmission electron microscopy analysis

The size and morphological features of the liposomes were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Briefly, 5 μl of 1 mM liposomes was placed on a carbon-coated copper grid (glow-discharged for 45 s using a TolarnoHavoc Evaporator) for 10 min. The excess sample was blotted with Whatman filter paper. The dried coated grids were vacuum-dried, and the electron micrographs of the liposomes were recorded with a FEITecnai 12 TEM instrument.

Thymoquinone entrapment

The amount of TQ incorporated into the lipid bilayer of the liposome was further evaluated by UV-visible spectrophotometry. Briefly, the unentrapped portion of the drug was separated by centrifugation at 3000 r.p.m. for 15 min using Amicon filter tubes (Merck Millipore, USA) with 10 KDa molecular weight cut-off. The concentrated liposomal portion containing the entrapped TQ was made upto 1 ml with milliQ water. Further, the liposomes were ruptured by incubation with surfactant (2% SDS) and the released TQ was extracted using 1 ml ethyl acetate. The absorbance was measured at 257 nm using the Jasco V-650 UV-visible spectrophotometer. A standard graph was plotted using varying concentrations of TQ and used as reference. The entrapment efficiency was calculated using the following formula:

Cellular uptake studies by confocal microscope

PANC-1, A549 and B16F10 cells were seeded on a coverslip placed in a six well plate, 24 h prior to treatment. The seeded cells were then treated with Rhodamine-PE labeled liposomes D1, D1T, D and DT in serum-containing medium. After 4 h, media was removed; the cells were washed thrice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min. The coverslip was finally mounted on a slide using mounting medium Fluoroshield with DAPI and imaged under confocal microscope (Nikon Ti Eclipse).

Cellular uptake of liposomes by FACS analysis

In a 6-well plate, 150,000 cells per well of PANC-1, A549 and B16F10 cells were seeded and incubated for 24 h in 2 ml of growth medium prior to the treatment. The treatment was done with Rhodamine-PE labeled liposomes of D1, D1T, D and DT in 10% serum containing media for 4 h. The cells were then washed with 1× PBS thrice and trypsinized and analyzed using a BD FACS Canto II flowcytometer with 10,000 cell counts.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic potential of pristine TQ, D1, D1T, D and DT liposomes was evaluated by MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay in PANC-1, A549 and B16F10 cell lines. Approximately 3000 cells in 100 μl complete media per well were seeded in 96-well plate prior to 24 h of treatment. The cells were then treated with the above formulations at 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 and 100 μM concentrations. After 4 h, the media was removed and the cells were washed with 1× PBS thrice followed by addition of 100μl of complete media and further incubation for 48 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 48 h, 50 μg MTT reagent (5 mg/ml) per well was added to the cells and incubated for 2 h followed by removal of MTT-containing media and addition of 50 μl DMSO to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured using the Synergy H1 microplate reader. Results were expressed as percent viability = (A570 [treated cells]/A570 [untreated cells]) ×100.

Colony formation assay

Approximately thousand PANC-1 cells were seeded per well in 24-well plate. After 18 h, the cells were treated with 4.6 μM TQ and 4.6 μM D1T. The cells were allowed to grow for 10 days with occasional washing and media change every 3 days. On the tenth day, the cells were washed with 1× PBS, fixed with methanol: acetic acid (3:1), stained with crystal violet (0.5% w/v) reagent and washed under tap water. The intensity of colonies between TQ and D1T treatments were compared and evaluated.

Apoptosis study

The Annexin V-FITC- labeled apoptosis detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to detect and quantify apoptosis by flow cytometry as per manufacturer’s instructions. Each well of a six-well plate was seeded with 200,000 cells prior to 18 h of treatment. The cells were then treated with 4.6 μM TQ and D1T (20 μM with respect to D1) upto 24 h. Following this, the cells were washed, trypsinized and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml binding buffer and 25 ng/ml FITC-labeled Annexin V and 50 ng/ml propidium iodide were added, followed by incubation under dark conditions for 10 min at room temperature. The extent of apoptosis was then analyzed using FACS Canto II flowcytometer with a minimum gating of 10,000 events per sample and data were processed using FCSExpress 4 software.

Scratch assay

Approximately 20,000 PANC-1 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate and allowed to grow overnight. When cells reached 100% confluence, the cell monolayer was scraped in a straight line with a pipette tip to create a cell-free gap. The culture medium was removed to clean cell debris, washed with 1× PBS and fresh medium was added followed by treatment with 4.6 μM TQ and 4.6 μM liposomal TQ (D1T) for 24 h. One set of wells were left as untreated (control). Cell migration was observed under a phase-contrast microscope and images of the scraped area were captured at the beginning (0 h) and at 24 h. A quantitative analysis was performed by using ImageJ software.

In vitro TQ release from D1T studies at different pH’s were performed according the protocols described in the Supplementary Information.

In vitro release of TQ from serum protein-TQ complex were performed according the protocols described in the Supplementary Information.

In vivo therapeutic analysis of liposomal formulation

Female NOD-SCID-Gamma (NSG) mice aged 6–8 weeks were purchased from NCI and were housed in the institutional animal facilities on a 12:12 h light and dark cycle with 5 mice per cage. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee at Mayo Clinic. Approximately 1 × 106 luciferase transfected PANC-1 cells suspended in 50 ul PBS were inoculated orthotopically into the head of the pancreas of the mouse. The growth of the tumor was monitored at 3 weeks of tumor cell implantation using IVIS bio-imager (data not shown) after injecting Luciferin. Mice were then randomized into four groups and treatment was initiated intraperitoneally (I.P.). Group 1 received PBS; group 2 received 50 g of TQ at a dose of 2 mg/kg; group 3 received D1 and group 4 received D1T. The volume of D1T was calculated to adjust the amount of TQ to 2 mg/kg. The volume of D1 was equivalent to the volume of D1T. Mice received treatments three-times a week for 3 weeks. After 3 weeks of treatment, mice were sacrificed using CO2 inhalation and tumor were harvested for further analysis. To calculate tumor volume, we measured the longest tumor axis (a) and shortest tumor axis (b) using slide calipers and used the formula: V = 0.5 x a x b2.

Histological study

Harvested tumors and other organ tissues were fixed in 10% formalin at room temperature for 24 h and then embedded in paraffin for sectioning. Tissue sections were immunolabeled for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Ki67 (DAB 150, Millipore) and cleaved caspase 3 (#9661, cell signaling). These sections were then visualized under the Aperio AT2 slide scanner (Leica) and analyzed with image scope software (Leica).

PK analysis

Eighty healthy male mice (C57BL/6j) weighing 25 g were acquired from the College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Animals were placed in two groups (n = 40 animals for each group and n = 5 for each time point) for I.P. administration and maintained in accordance with the approvals of the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” of the Center in King Saud University. Animals were placed under normal laboratory conditions (humidity 60%; temperature 23 ± 2°C and a 12:12 h light and dark cycle) with free access to granulated standard food and water.

TQ was dissolved in normal saline containing 10% DMSO. After 12 h fasting, TQ was administered in mice I.P. at a dose of 2 mg/kg (group I). Group II received liposomal formulations of TQ (D1T) through I.P. administration at a dose of 2 mg/kg equivalent to TQ. Blood samples were collected at the following intervals–immediately before administration and 0.25, 0.50, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 12-h post I.P. administration. The blood samples were then collected in Eppendorf tubes containing 8 mg of disodium EDTA as an anticoagulant. Plasma was separated by centrifugation (Eppendorf, MiniPlus centrifuge, NY, USA) at 5000xg for 10 min and stored at -80°C for the quantitative analysis of TQ.

Sample preparation & PK analysis

The concentration of TQ in mice plasma was quantified by a ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC)/UV detection method. Waters Acquity H-class UPLC system coupled with a Waters UV-detector by AcquityUPLC (Waters, MA, USA) was used for the analysis of TQ. The chromatographic system included sample manager (Acquity, UPLC Waters) with injection capacity of 10 μl, quaternary solvent manager and a column heater. The elution of TQ was performed on “Acquity UPLC BEH™ C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters)” maintained at 25°C. The mobile phase was composed of methanol: phosphate buffer % 90:10 v/v ratio (pH of the buffer was maintained at 4.2), which was pumped at an isocratic flow rate of 0.12 ml min-1. The injection volume was and detected by UV-detector at 254 nm. The ‘EMPOWER’ software was used to control the UPLC-UV system as well as for data acquisition and processing.

Plasma (200 μl) containing TQ and 20 μl of IS (20 μg/ml) was added in an Eppendorf tube and vortex to mix. The mixture was centrifuged at 2500xg for 10 min. The upper layer was removed and transferred into a new Eppendorf tube and 10 μl from the sample was injected into the UPLC column for TQ analysis. A noncompartmental PK analysis of TQ as previously described, was used to determine the PK performance of TQ in plasma [24,25]. The PK analysis was performed using PK Solver software (version 1.0) on the individual plasma concentration-time curves. The calculated parameters were as follows: The terminal elimination rate constant (λz), the apparent elimination half-life (T1/2), time to maximum concentration (Tmax), maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), the area under plasma concentration-time curve (AUC), the volume of distribution (Vd) and total clearance (CL).

Statistical analysis

Unpaired t-test was performed using GraphPad Prism (Version 6.04 for Windows, Graph Pad Software, CA, USA). It was used to analyze the data followed by ‘One-way ANOVA’ with Dunnett’s post-test.

Results

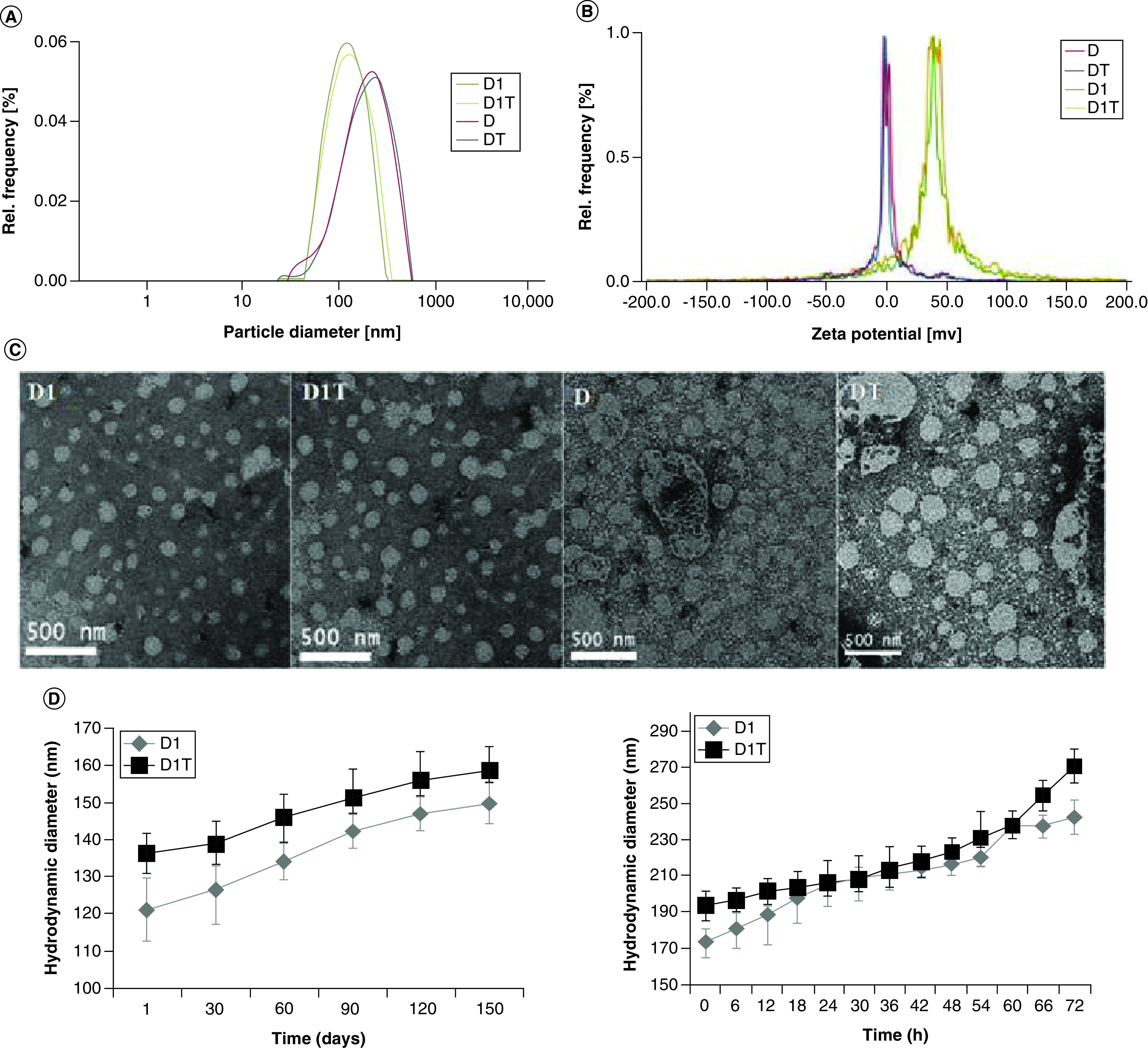

Physicochemical characteristics of the liposomal formulations

In order to know the effect of liposomal TQ, we made four liposomal formulations. Initially, we evaluated the physicochemical properties such as hydrodynamic diameter, surface potential and liposomal shape, size uniformity by DLS and TEM studies, respectively, along with the stability of the formulations. We have found that the hydrodynamic diameters of D1 and D1T liposomes are around 110–120 nm and D and DT liposomes are around 170–180 nm (Figure 1A). We further characterized the surface charge of D1 and D1T and found that these liposomes possess positive charge owing to the presence of cationic lipid, while D and DT liposomes possess a neutral charge (Figure 1B). TEM analysis clearly shows that individual particles of all four formulations have circular shapes and are uniformly distributed. It is also clear that D1 and D1T liposomal particles have a smaller size as compared with D and DT liposomal particles (Figure 1C). The stability of the D1 and D1T liposomes was evaluated by DLS up to 150 days in deionized water (Figure 1D) and up to 72 h in 10% FBS (Figure 1E). As evident from the study, the formulations are very stable under the specified conditions. Further, prior to biological evaluation studies, the effective amount of TQ entrapped in the liposomes was estimated. The respective percentages of TQ entrapped in D1T and DT liposomes were 58 and 55%, respectively.

Figure 1. . Physicochemical characteristics of the liposomal formulations.

(A) particle size distribution and (B) zeta potentials of the liposomal formulations as measured by dynamic light scattering. (C) Size distribution and morphology of the particles as seen by transmission electron microscopy. (D and E) Stability of D1 and D1T liposomal formulations in (D) deionized water and (E) 10% fetal bovine serum.

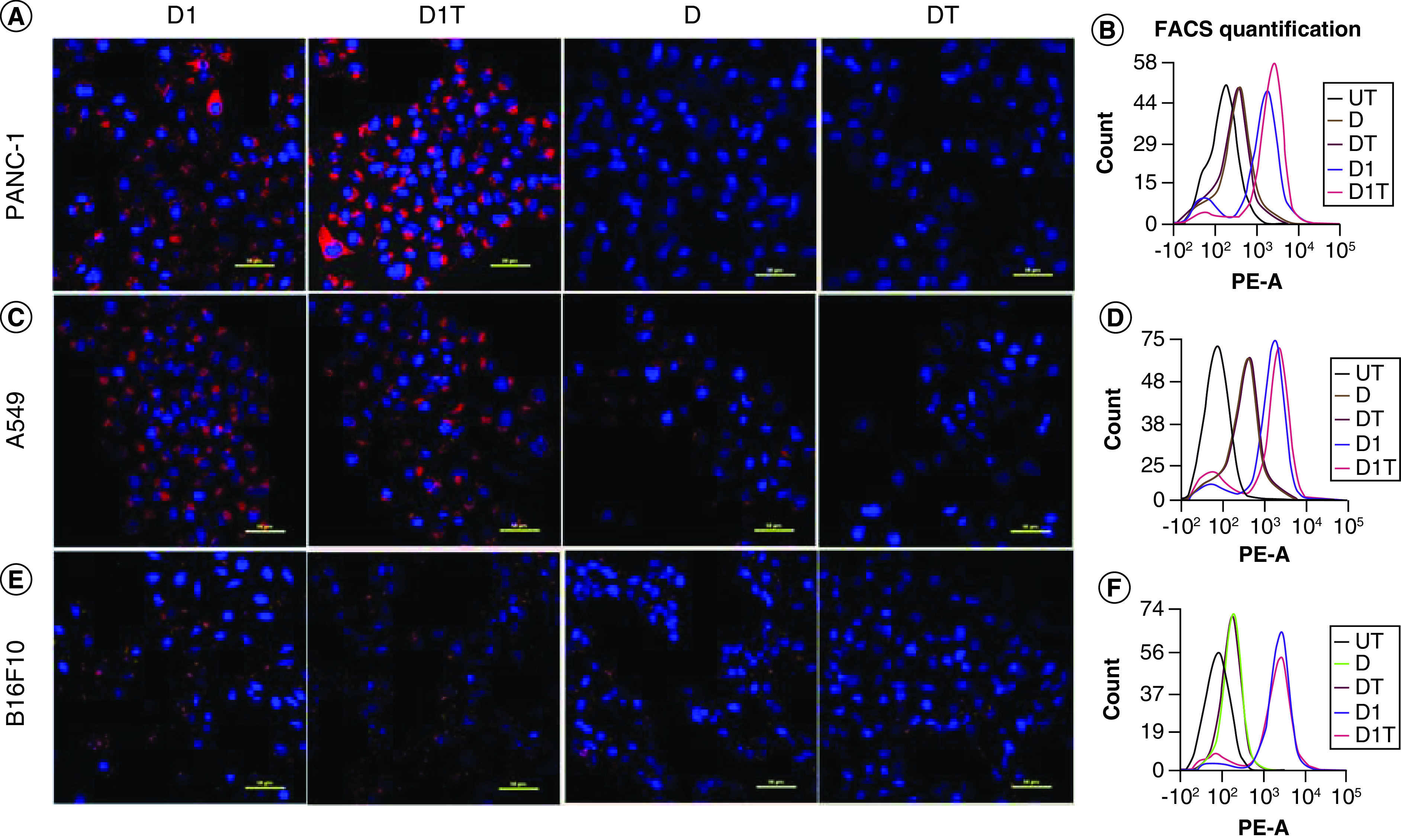

Cellular uptake of D1, D1T, D & DT

To evaluate the cellular uptake of the D1, D1T, D and DT liposomes, we used rhodamine-PE labeled liposomal formulations to treat different cancer cell lines such as human pancreatic cancer (PANC-1), human lung cancer (A549) and mouse melanoma (B16F10) and studied the cellular uptake using confocal microscopy and flow cytometry (Figure 2). We observed that D1 and D1T liposomes readily internalized into the cells as compared with D and DT liposomes after 4 h of treatment as evident from confocal microscopic and flow cytometric studies. This is because of the favorable asymmetric twin chain and net positive charge of the D1 lipid resulting in relatively higher cell membrane fusogenicity and uptake of D1 and D1T liposomes compared with DOPC lipid-containing and DT liposomes.

Figure 2. . Cell uptake of liposomal formulations.

Cellular uptake of Rh-PE labeled liposomal formulations (D1, D1T, D and DT) as seen by (A), (C & E) confocal microscopy and (B, D & F) flow cytometry in different cancer cells. (A & B) PANC-1 (human pancreatic cancer cell line), (C & D) A549 (human lung cancer cell line), (E & F) B16F10 (mouse melanoma cell line). Images were taken at 40× magnification and the scale bar is 50 μm.

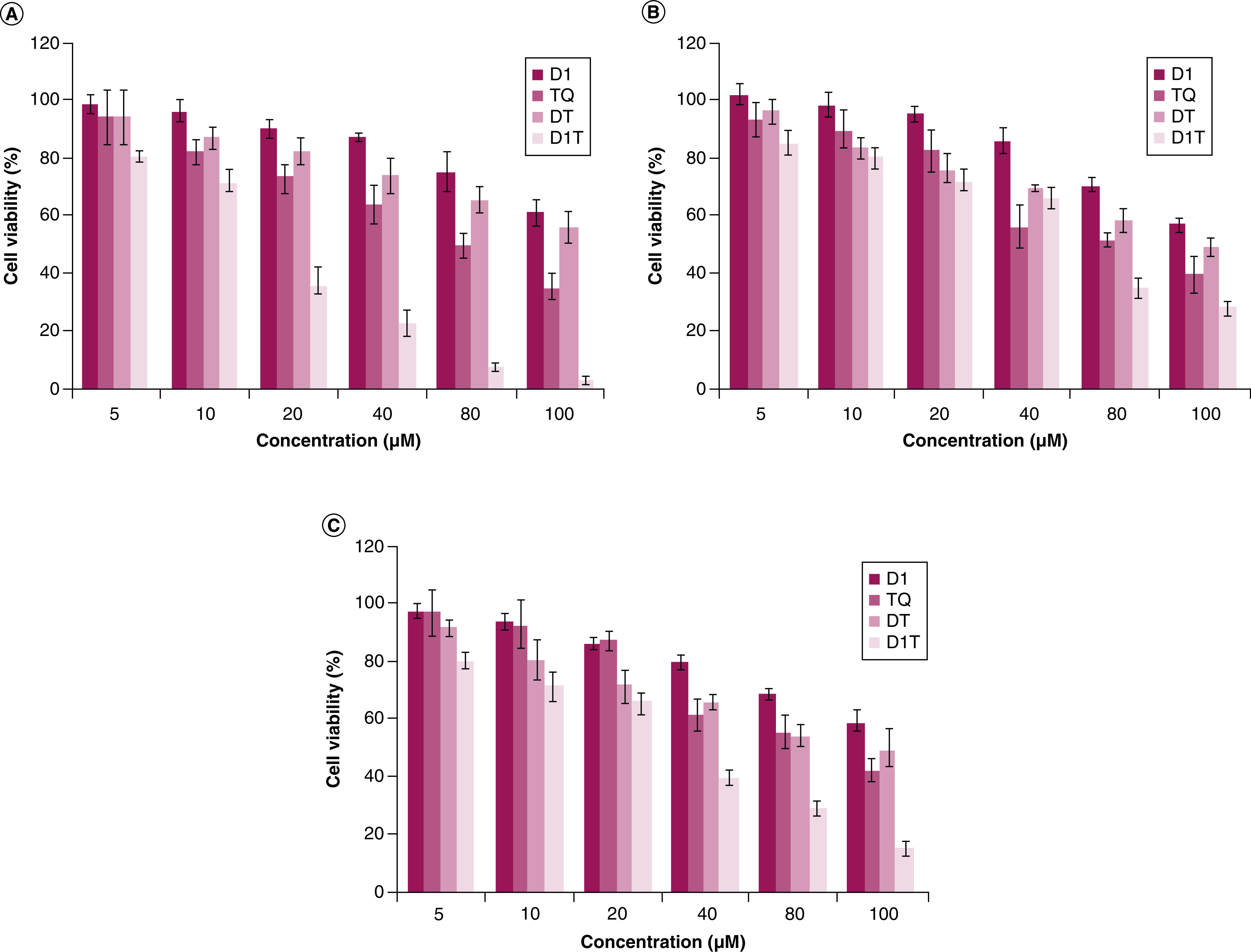

Cellular viability studies

To evaluate the in vitro cytotoxic effect of TQ containing liposomal formulations, we used MTT assay. Initially, we performed a cytotoxicity profiling of pristine TQ after 48 h exposure in three different cancer cell lines (PANC-1, B16F10 and A549). Further, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of TQ-entrapped liposomal formulations (D1T, DT) along with the liposomal controls (D1) in PANC-1 (Figure 3A), B16F10 (Figure 3B) and A549 (Figure 3C) for 48 h. As is evident from Figure 3 & Supplementary Table 1, at same TQ concentration D1T formulation show higher cytotoxicity relative to DT liposomal formulations and pristine molecule, TQ. D1T liposomal formulation showed approximately eight to tenfold higher cytotoxicity compared with the DT and four to sixfold compared with pristine TQ in PANC-1 cell line (Figure 3A). The data show that efficient cellular delivery of TQ by D1 liposome indeed induce considerable TQ-mediated cellular toxicity in cancer cells. Higher cytotoxicity of D1T is due to liposome associated TQ and not due to D1 liposome.

Figure 3. . Cell viability study of liposomal formulations.

Cellular viability studies of pristine drug (TQ) and liposomal formulations (D1, D1T and DT) in different cancer cell lines (A) PANC-1, (B) B16F10 and (C) A549 as measured by MTT assay. X-axis denotes TQ concentration. For all D1 treatments the concentration of D1 lipid is equal to the concentration of D1 lipid present in D1T under each treatment condition. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Colony formation assay

To evaluate the effect of D1T formulation in inhibiting the colony forming ability of pancreatic cancer cells, we performed a clonogenic assay by crystal violet staining. We observed that (Supplementary Figure 3) D1T significantly inhibited the colony forming ability of PANC-1 cells at TQ concentration of 4.6 μM concentration, while pristine TQ at the same concentration did not show any effect on the cancer cells’ colony forming ability.

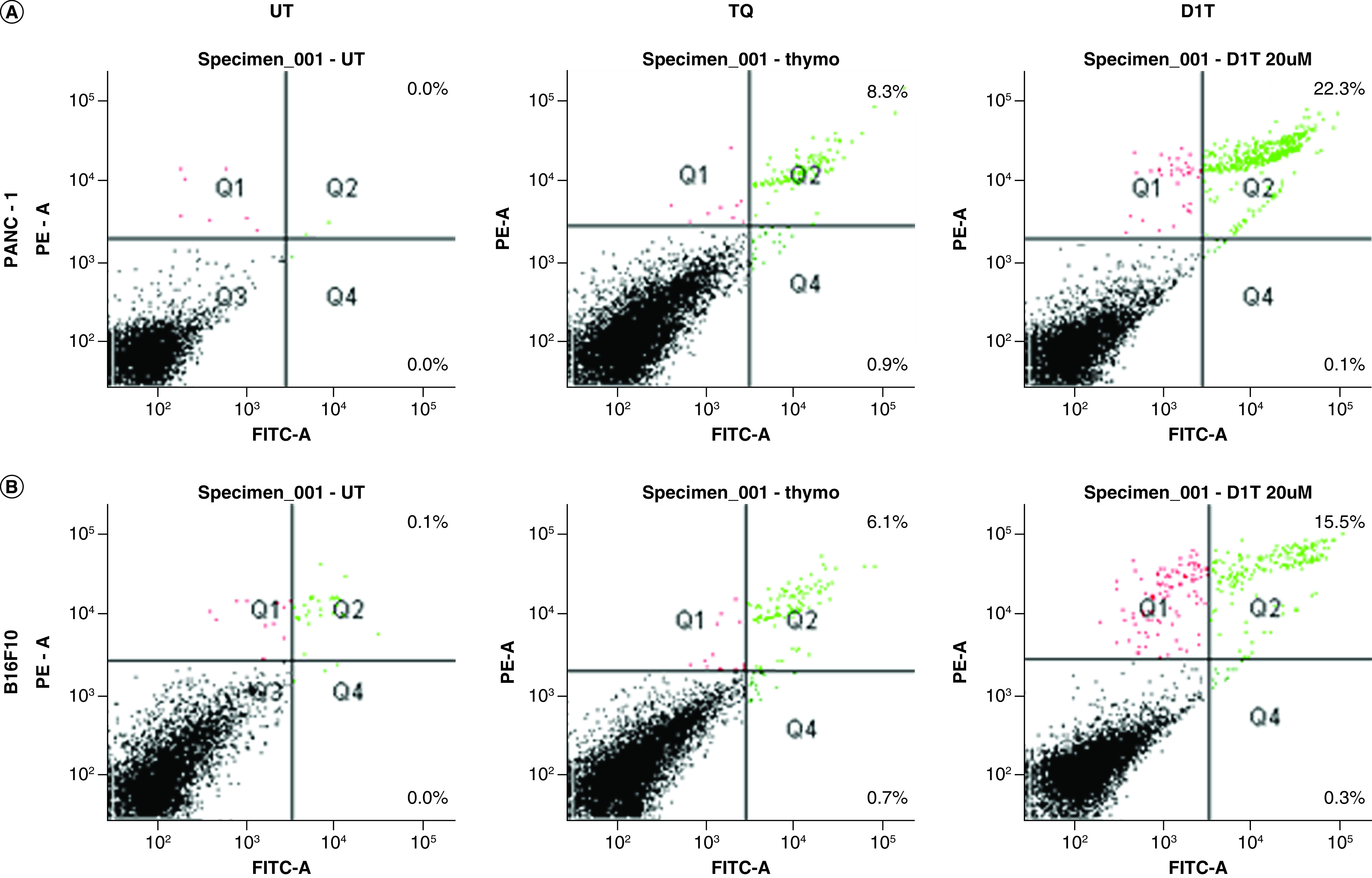

Induction of apoptosis

To determine if the cytotoxic effect of D1T is due to the induction of apoptosis, we evaluated the cells treated with 4.6 μM TQ either in pristine form or in D1T formulation using Annexin V-FITC- labeled apoptosis detection kit. It was observed that the percentage of apoptotic cells was significantly higher in the D1T treatment group compared with pristine TQ in both PANC-1(a) and B16F10(b) cell lines (Figure 4). The apoptotic effect almost got doubled in the D1T treatment group compared with pristine TQ treatment in the PANC-1 pancreatic cancer cell line, indicating a profound efficacy of D1T formulation in PC.

Figure 4. . Apoptotic analysis of liposomal formation.

Apoptosis study using flow cytometer in (A) PANC-1 and (B) B16F10 cells. Cells were either kept untreated or treated with 4.6 μM TQ and liposomal formulated TQ (equivalent to 4.6 μM TQ) for 24 h.

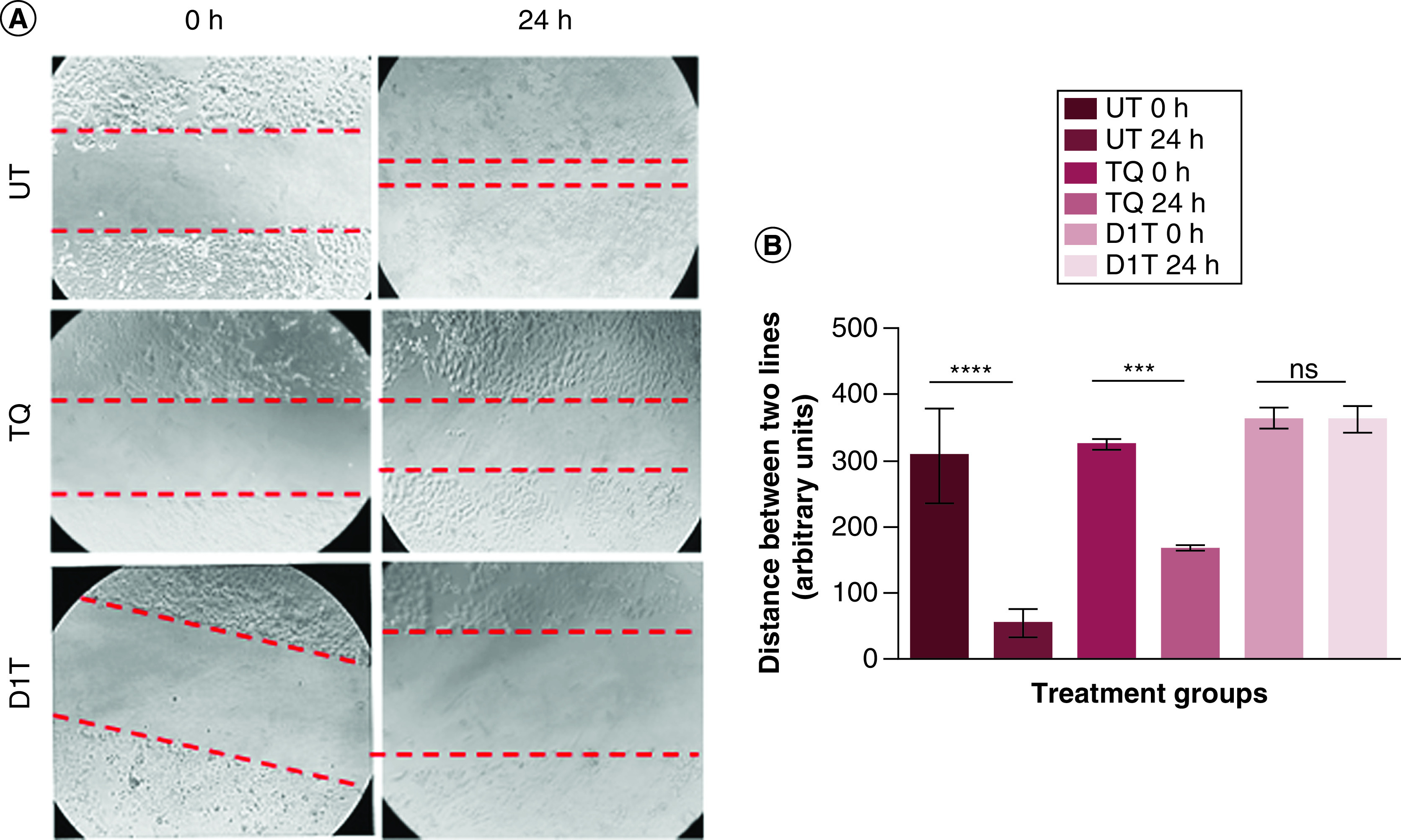

Effect of liposomal TQ on PANC-1 cell migration

To evaluate the effect of D1T formulation on attenuating the cancer cell migratory potential, we performed a scratch assay in PANC-1 cells. We observed (Figure 5A) that the gap created by the scratch almost got covered within 24 h in the untreated group and this effect was almost reduced by half in 4.6 μM pristine TQ-treated cells. However, in D1T with 4.6 μM TQ treated cells, the gap remained the same as that at 0 h time point even after 24 h and there was a visible change in cell morphology, indicating a substantial inhibition of cancer cell migratory potential (Figure 5B) and significantly enhanced cytotoxicity.

Figure 5. . Migration analysis of liposomal formulation using scratch assay.

(A) Representative images of scratch assay of UT, (4.6 μM) TQ-treated and D1T (equivalent to 4.6 μM TQ) formulation-treated PANC-1 cells at 0 and 24 h time points. The red dotted lines represent the gap created by the scratch at the start of the assay. (B) Quantification of the changes in the gap area at 0 and 24 h time points in untreated and different treatment groups. Images were taken at 10× magnification.

****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001.

ns: Non-significant; UT: Untreated.

In vitro TQ release study

To know the TQ release profile from the D1T at 4.4, 5.4 and 7.4 pHs, we used direct dispersion method at time points 0–10 h at 2 h intervals. For pH 4.4 and 5.4, we monitored 100% TQ release from liposomal formulations. On contrary, only 40% of TQ were released from D1T at the physiologic pH as shown in Supplementary Figure 4.

In vitro serum protein binding study

Furthermore, we compared the interaction of TQ with serum both in free form and encapsulated in D1T. It previously reported that TQ has high affinity to bind with serum protein [26]. We monitored subsequent release of TQ from TQ-serum complex with time from nearly 2.5 to 6% (Supplementary Figure 5). Whereas TQ released from D1T is relatively less to interact with serum; the TQ release form serum-TQ complex in this case only changes from nearly 1.75 to 2.5% overtime. Clearly, TQ is more protected in D1T and restricted from the interaction with serum proteins.

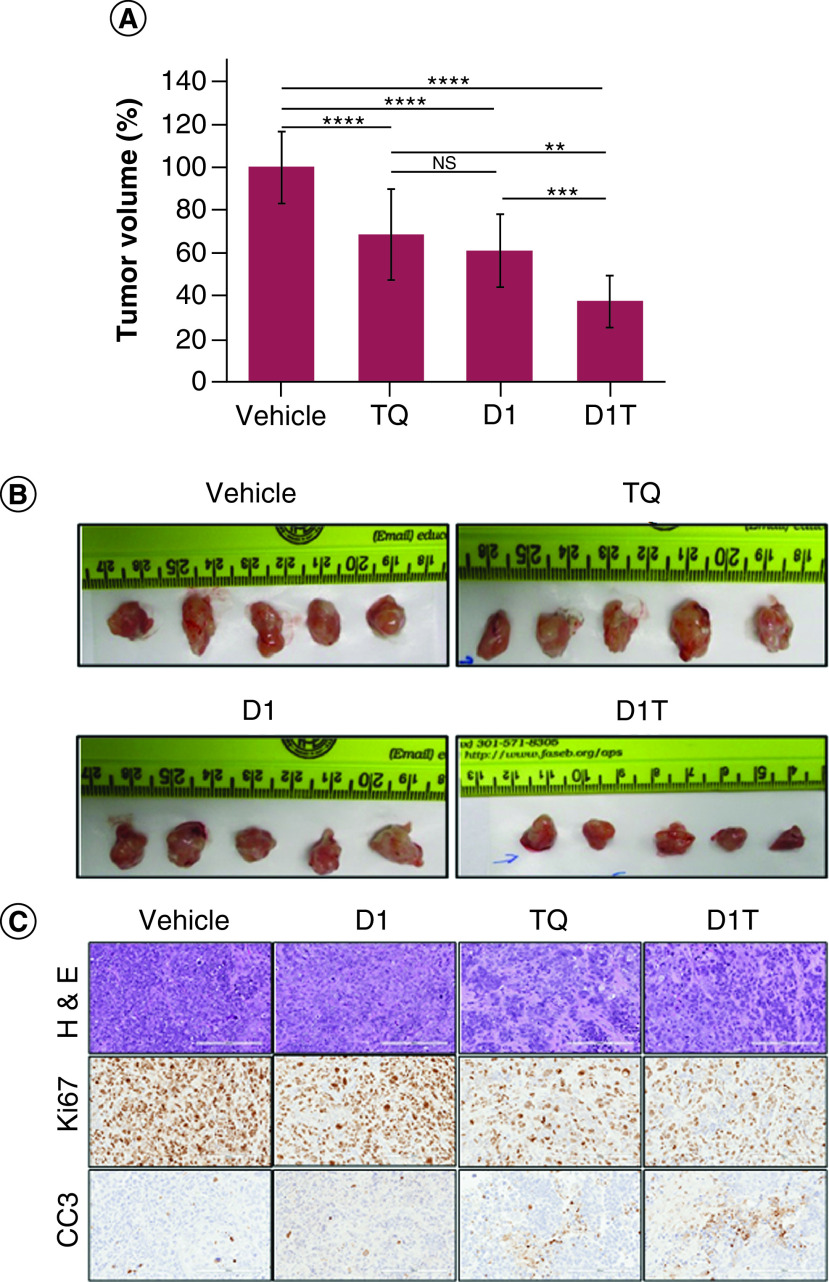

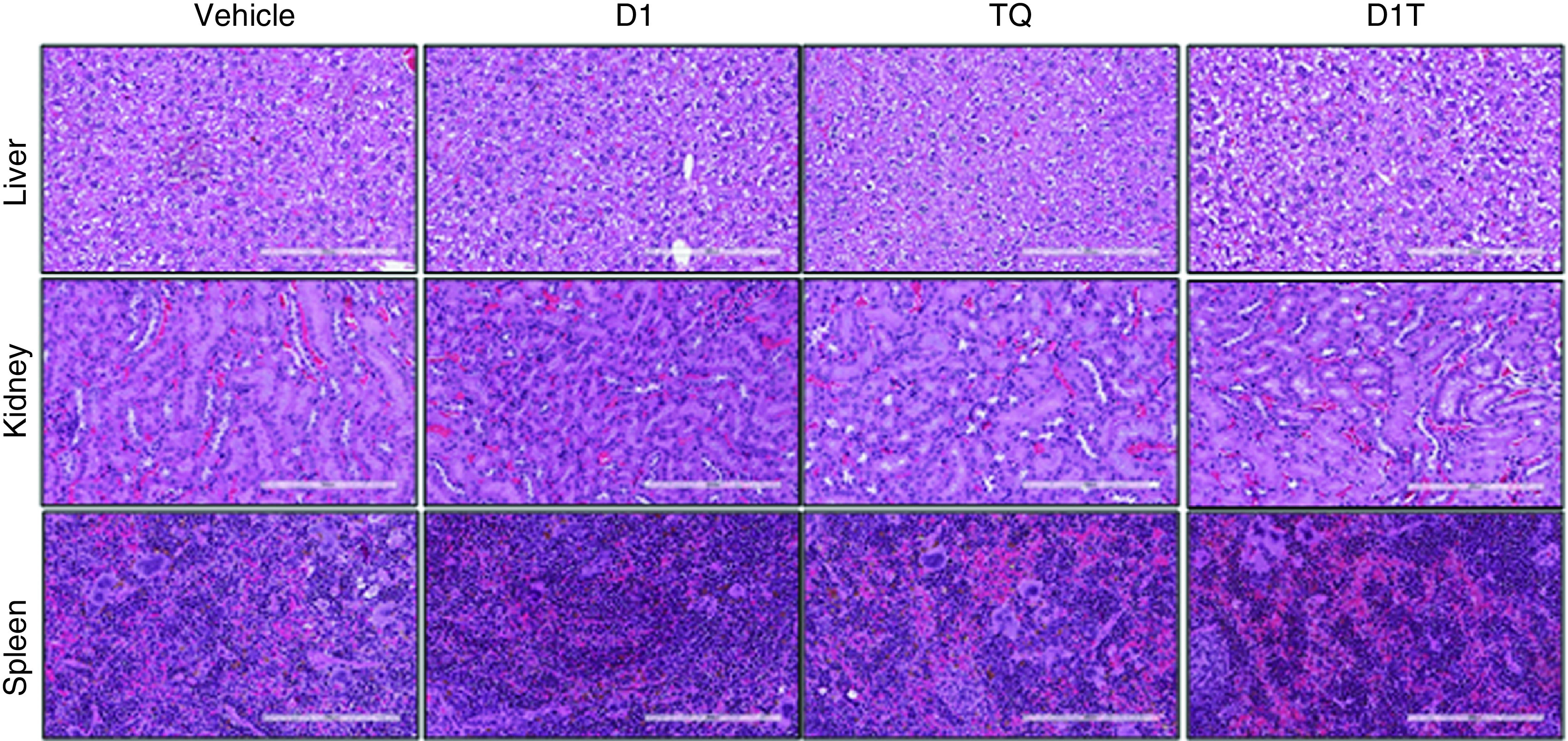

Therapeutic outcome in in vivo model

Liposomal formulation of TQ is further evaluated in the PANC-1 orthotopic xenograft model. After 3 weeks of treatment, mice were then sacrificed and tumor was harvested. Figure 6A represents the qualitative analysis of the effect of TQ liposomal formulation on tumor volume and Figure 6B displays the bright field images of tumors collected from each experimental group. Tumor volume was restricted to 69% ± 20.9 by TQ alone when compared with vehicle-treated group. D1 alone also was quite effective in restricting tumor progression (61% ± 16.69 compared with vehicle-treated group). Moreover, the TQ liposomal formulation was more effective in restricting tumor growth (up to 37.55% ± 12.16). The standard deviation for vehicle group was 16.6. H&E staining of tumor tissue sections for D1T group shows significant loss of cellularity compare with vehicle, D1 and TQ-treated group as shown in top panel of Figure 6C. Not surprisingly, tumor tissue from D1T treatment group presents less proliferative cancer cells as represented by Ki67 positive nuclei (middle panel of Figure 6C) and more apoptotic cells identified by cleaved caspase 3 (CC3) staining (lower panel of Figure 6C). To understand the toxicity of this formulation, we further examined tissue section of several major organs such as liver, kidney and spleen by H&E staining (Figure 7). Apart from TQ group alone, no significant structural alteration of liver was monitored in other treatment groups. Kidney and spleen show no insult from therapy in any experimental group.

Figure 6. . In vivo efficacy study of liposomal formulation.

In vivo inhibition of pancreatic tumor progression and immunohistochemistry analysis of tumor sections: (A) Significant reduction in tumor volumes in groups treated with D1T liposome relative to the pristine TQ, D1 and vehicle groups. (B) Images of isolated tumor mass from different treatment groups showing significant tumor volume reduction by D1T liposome relative to pristine TQ, D1 liposome and vehicle-treated groups. (C) Immunohistochemistry images of H&E staining (upper panel), cell proliferation marker (Ki67, middle panel) and apoptosis marker cleaved caspase 3 (CC3, lower panel) in tumor sections of indicated groups. Images were taken at 20× magnification and the scale bar is 200 μm.

**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

H&E: Hematoxylin and eosin; NS: Nonsignificant.

Figure 7. . Histological analysis to assess organ toxicity of liposomal formulation.

Histology examination (hematoxylin and eosin staining) of tissues taken from major organs (liver, kidney and spleen) after treatment of indicated groups. Images were taken at 20× magnification and the scale bar is 200 μm.

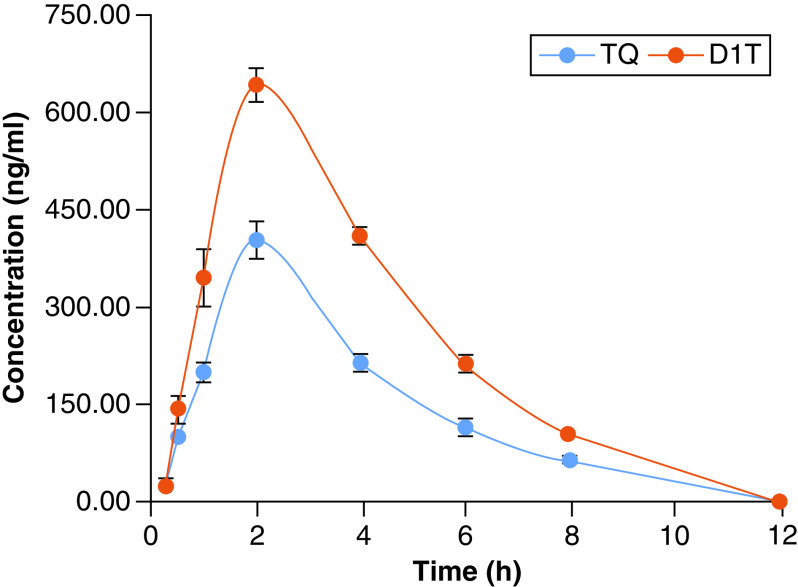

PK evaluation

The plasma concentration-time profile of D1T showed a significant improvement in in vivo absorption compared with pristine TQ. The PK data are shown in Supplementary Table 2 & Figure 8. The Tmax value was noted as 2.40, 2.0 h for D1T and TQ, respectively. However, the Cmax value of D1T was found to be 644.47 ng/ml and 404.08 ng/ml for TQ. AUC0–t of D1T was found to be 2635.82, which was highly significant (p < 0.05) as compared with AUC0–t (1527.00 ng/ml*h) of TQ alone. The relative bioavailability of D1T with respect to TQ alone was recorded as 159.49% as compared with TQ alone. The volume of distribution (Vd/F) and clearance (CL) were decreased in D1T in comparison to TQ (2.01 vs 3.84 ml/kg and 0.68 vs 1.73 ml/kg/h).

Figure 8. . Pharmacokinetic study of liposomal formulation.

Plasma concentration–time curves of pristine TQ and TQ liposomal formulation (D1T) following intraperitoneal injections in mice. Each value is expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 5).

TQ in liposomal formulation DIT exhibited significant improvement in bioavailability as compared with pristine TQ. The improved intraperitoneal bioavailability of TQ from liposomes was apparently due to nanosized droplets of liposomes and the presence of solubilizers in comparison with normal TQ.

Discussion

The therapeutic merit of TQ has been limited by its poor PK attributes. It includes poor solubility and bioavailability due to strong interaction with serum proteins [26]. To overcome this clinical challenge, recently encapsulation of TQ with lipid-based nanoformulation has been studied by many groups with limited advancements [12,27,28]. Cationic lipid has been identified as superior candidate for drug delivery and has been forwarded to clinical trials [29,30]. We have previously reported that the efficacy of asymmetric cationic liposomal formulation can be improved by selection of one saturated and one unsaturated chain containing lipid [21,22]. More specifically we have shown that, this strategy improves the cellular penetration of liposomes and reduce systemic toxicity of otherwise toxic drugs [21,22].

Here, we report liposomal formulation of TQ using asymmetric cationic lipid, D1 and have conducted a thorough physico-chemical characterization, stability and release kinetics at different pH and in serum, in vitro and in vivo therapeutic toxicity and a detail PK analysis. For comparison, we have also encapsulated TQ in neutral lipid-based formulation, DT. D1T presented improved therapeutic outcome of TQ in both cell culture and preclinical studies. D1T treated PANC-1 cells have shown a substantial inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and migration and increased apoptosis. D1T successfully restricted tumor volume progression relative to pristine TQ in orthotopic xenograft of pancreatic cancer without causing significant systemic toxicity to other organs. Following the same mode of administration, we have also performed the PK studies which have shown enhanced systemic bioavailability of TQ in D1T.

The asymmetric cationic lipid, D1 ([Z]-N, N-bis[2-hydroxyethyl]-N-octadecyloctadec-9-en-1-aminium chloride) enhances the physicochemical characteristics of liposomal formulation compared with neutral lipid (DOPC, D) based liposomes. Both TEM and DLS studies confirmed that the particles size was smaller in D1 and D1T compared with D and DT. Moreover, the both D1 and D1T found to be stable for more than 150 days in water. This is in agreement with our previous findings where we reported that the presence of asymmetric lipids in liposome resulted in smaller, stable and lesser translucent liposomal formulations than symmetric lipid containing liposomal formulations [21,22]. The selection of cationic lipids resulted in net positive charge at the liposomal surface. In addition, we have successfully presented that both D1 and D1T readily internalized in several types of cancer cells including pancreatic, melanoma and lung cancer cells compared with D and DT. As reported previously, net positive charge and single unsaturated C–C bonds of D1 and D1T improves the internalization of these liposomes into cancer cell lines [21–23].

To achieve effective cancer cytotoxicity, many groups has reported higher concentration of TQ [31,32], whereas D1T shows effective cytotoxicity at fourfold lower concentration to that of previously reported pristine TQ. This confirms that the efficient cellular delivery of TQ by D1 liposome was the paramount factor for the efficient killing of cancer cells. Additionally, D1T formulation led to the inhibition of migration and colony forming ability of PANC-1 cells and significantly increased percentage of apoptotic cells.

Additionally, systemic cytotoxicity of TQ is one major clinical challenge [33,34]. To address these, Rathore et al. developed TQ encapsulated phospholipid-nanoparticles to enhance the low oral bioavailability and anti-inflammatory activity. They have found that this formulation enhances the inflammatory disorders treatment capacity and promising carrier system to augment TQ oral bioavailability [27]. Similarly, Odeh et al. also developed the TQ encapsulated neutral liposomal nano-formulations against breast cancer cell lines. This formulation showed effective in suppressing the proliferation of breast cancer cell lines and at the same time exerting very low toxicity on normal periodontal ligament fibroblasts [12]. Additionally, many research groups have developed various nano-formulations to enhance therapeutic efficacy of TQ, but there was no valiant formulation for clinical translation [28]. Clearly, more effective formulation needs to obtain to overcome these clinical shortfalls. To evaluate the therapeutic merit of D1T in preclinical settings, we adopted commonly used orthotopic model of pancreatic cancer by implanting PANC-1 cells at the head of pancreas. Not surprisingly, D1T presents increased efficiency to restrict pancreatic tumor growth compared with pristine TQ. Histological analysis also confirmed the loss of proliferative cells and elevation of apoptotic cells in the tumor tissue sections. Additionally, this cationic lipid-based liposomal formulation prevented toxicity of TQ in liver, kidney and spleen. To assess therapeutic benefit of this nanoformulation more rigorous testing is required using transgenic mice model for pancreatic cancer that closely match with heterogeneous profile of tumor microenvironment in human pancreatic cancer.

Despite showing better therapeutic efficacy, TQ exhibits poor bioavailability and rapid clearance due to low solubility and nonpolar nature [35]. To enhance the systemic bioavailability and specific therapeutic efficacy of TQ, Singh et al. developed a solid lipid nanoparticle of TQ by solvent injection method. This nano-formulation accelerates TQ stability and bioavailability relative to TQ suspension [36]. Additionally, many research groups have tried to develop different TQ loaded nano-formulations to improve stability, bioavailability and lower clearance [28]. However, therapeutically translated TQ formulation is still not reported. Here, in this study we found D1T formulation improves the stability and bioavailability of TQ at physiologic pH (pH 7.4) and in serum. Due to this unique liposomal formulation, TQ is well guarded in D1-liposome and thus has less interaction with serum protein. Hence, this disable serum-assisted precipitation of TQ which is a common clinical demerit of TQ [24]. This in vitro data have reflected also in the in vivo PK observations. Although there exists an apparent peak pattern similarity between PK of free TQ and liposome (D1T)-bound TQ, with a significant difference in other important parameters such as maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and AUC. With enhanced Cmax and AUC, one can witness significantly decreased plasma clearance (CL) as well as the volume of distribution of TQ absorbed (Vd) for liposome bound TQ. Clearly, the free TQ, in comparison with D1 bound TQ, will have a less effective dose in blood at a given time point. These PK findings clearly improve the bioavailability of TQ entrapped in D1T and lead to enhance the therapeutic outcome of TQ.

Conclusion

Thymoquinone, a natural bioactive compound holds potential anticancer activity but exhibits poor bioavailability and rapid clearance due to low solubility and nonpolar nature. In order to enhance the systemic bioavailability and tumor-specific toxicity of TQ, we have formulated a cationic liposomal formulation containing TQ (D1T) and compared its efficacy against pristine TQ and a neutral lipid-based formulation (DT). D1T clearly exhibited better cellular uptake and higher cytotoxicity as compared with TQ and DT, owing to the net positive charge of the associated cationic lipid resulting in better fusogenicity with the cell membrane. Further, D1T also showed increased apoptosis, reduced clonogenic and migratory potential and substantially decreased the tumor volume relative to TQ in orthotopic xenograft pancreatic tumor. H&E staining of tumor sections revealed significant tumor tissue impairment in D1T treated group compared with TQ, while that of vital organs revealed a relatively negligible toxicity similar to that of vehicle-treated group, indicating a potentially enhanced, tumor-selective action of D1T. We have also evaluated the PK behavior of D1T relative to TQ upon I.P. injection and observed that D1T showed enhanced systemic bioavailability as evident from increased AUC, Cmax and reduced Vd and clearance values. These results suggest that D1T exhibits a better therapeutic potential compared with pristine TQ, owing to its favorable physico-chemical, PK, tumor-selective properties and insignificant nonspecific adverse effects. This strategy of formulating low-soluble, nonpolar drugs such as TQ in cationic liposome allows for the development of targeted and cancer-selective therapeutics with enhanced PK properties such as better bioavailability, reduced clearance and bestows beneficial therapeutic effects.

Summary points.

TQ were successfully encapsulated in liposomal formulations containing an asymmetric cationic lipid.

Asymmetric twin chain and net positive charge of the lipid in the liposomal formulations of D1 and D1T enhanced the cell membrane fusogenicity and resulted in their relatively higher cellular uptake compared with neutral DOPC lipid-based D and DT liposomal particles.

The cytotoxicity of D1T liposomal formulation was approximately eight to tenfold higher compared with DT and four to sixfold higher compared with pristine TQ in PANC-1 cell line.

D1T formulations was found to be more effective in restricting tumor growth than pristine TQ in orthotopic pancreatic cancer model.

Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor sections revealed loss of cellularity, less proliferative cells and more apoptotic cells in D1T-treated tumors as determined using hematoxylin and eosin, Ki67 and CC3 staining, respectively.

D1T-treated tissue sections of major organs including liver, kidney and spleen showed no significant structural alterations.

Improved pharmacokinetic behavior and enhanced systemic bioavailability of D1T relative to pristine TQ was evident from area under plasma concentration-time curve, Cmax, Vd and clearance values.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.futuremedicine.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/nnm-2020-0470

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors extend their appreciation to the National Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation (MAARIFAH), King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for funding this project through Award Number (Grant number 12-MED2897-02). HK Rachamalla, K Sridharan, S Jinka, MMCS Jaggarapu, V Yakati acknowledged CSIR, Govt. of India for their doctoral fellowship. R Banerjee acknowledged DST (Grant no. EMR/2017/00183) and Director, CSIR-IICT (IICT communication number IICT/Pubs./2019/356) for fund supports. This work is partly supported by the National Institutes of Health grants CA78383, CA150190 (D Mukhopadhyay), Florida Department of Health (Cancer Research Chair Fund, Florida #3J to D Mukhopadhyay). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations.

Blinded for review

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee at Mayo Clinic.

Eighty healthy male mice (C57BL/6j) weighing 25 g were acquired from the College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Animals were placed in two groups (n = 40 animals for each group and n = 5 for each time point) for I.P. administration and maintained in accordance with the approvals of the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” of the Center in KSU.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Das S, Batra KS. Pancreatic cancer metastasis: are we being pre-EMTed? Curr. Pharm. Des. 21(10), 1249–1255 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goess R, Friess H. A look at the progress of treating pancreatic cancer over the past 20 years. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 18(3), 295–304 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2012. American Cancer Society, GA, USA: (2012). https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2012.html [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abel-Salam BK. Immunomodulatory effects of black seeds and garlic on alloxan-induced diabetes in albino rat. Allergol. Immunopathol. 40(6), 336–340 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad S, Beg ZH. Mitigating role of thymoquinone rich fractions from Nigella sativa oil and its constituents, thymoquinone and limonene on lipidemic-oxidative injury in rats. SpringerPlus 3, 316 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Findings demonstrate that thymoquinone rich natural extract shows significant antioxidant activities.

- 6.Chu S, Hsieh Y, Yu C, Lai Y, Chen P. Thymoquinone induces cell death in human squamous carcinoma cells via caspase activation-dependent apoptosis and LC3-II activation-dependent autophagy. PLoS ONE 9(7), e101579 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo CC, Kumar AP, Sethi G, Tan KH. Thymoquinone: potential cure for inflammatory disorders and cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 83(4), 443–451 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majdalawieh AF, Fayyad MW, Nasrallah GK. Anti-cancer properties and mechanisms of action of thymoquinone, the major active ingredient of Nigella sativa. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57(18), 3911–3928 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attoub S, Sperandio O, Raza H et al. Thymoquinone as an anticancer agent: evidence from inhibition of cancer cells viability and invasion in vitro and tumor growth in vivo. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 27(5), 557–569 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Relles D, Chipitsyna GI, Gong Q, Yeo CJ, Arafat HA. Thymoquinone promotes pancreatic cancer cell death and reduction of tumor size through combined inhibition of histone deacetylation and induction of histone acetylation. Adv. Prev. Med. 2016, 1407840 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Far AH, Al Jaouni SK, Li W, Mousa SA. Protective Roles of thymoquinone nanoformulations: potential nanonutraceuticals in human diseases. Nutrients 10(10), 1369 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrates that thymoquinone represents rapid clearence, relatively slower absorption and poor bioavailability.

- 12.Odeh F, Ismail SI, Abu-Dahab R, Mahmoud IS, Al Bawab A. Thymoquinone in liposomes: a study of loading efficiency and biological activity towards breast cancer. Drug. Deliv. 19(8), 371–377 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrates that thymoquinone encapsulated liposomes were effective in stopping breast cancer cell growth and improve the TQ bioavailability.

- 13.Dass CR, Choong PF. Targeting of small molecule anticancer drugs to the tumour and its vasculature using cationic liposomes: lessons from gene therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 6(1), 17 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent S, Depace D, Finkelstein S. Distribution of anionic sites on the capillary endothelium in an experimental brain tumor model. Microcirc. Endothelium Lymphatics 4(1), 45–67 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Löhr JM, Haas SL, Bechstein WO et al. Cationic liposomal paclitaxel plus gemcitabine or gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled phase II trial. Ann. Oncol. 23(5), 1214–1222 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pal K, Pore S, Sinha S, Janardhanan R, Mukhopadhyay D, Banerjee R. Structure-activity study to develop cationic lipid-conjugated haloperidol derivatives as a new class of anticancer therapeutics. J. Med. Chem. 54(7), 2378–2390 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudhakar G, Bathula SR, Banerjee R. Development of new estradiol-cationic lipid hybrids: ten-carbon twin chain cationic lipid is a more suitable partner for estradiol to elicit better anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 86, 653–663 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rathore B, Chandra SJMM, Ganguly A, Reddy R HK, Banerjee R. Cationic lipid-conjugated hydrocortisone as selective antitumor agent. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 108, 309–321 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Cationic lipid-hydrocortisone conjugate (HYC16) shows higher anti-angiogenic behavior and helped in effective tumor shrinkage.

- 19.Madamsetty VS, Pal K, Dutta SK et al. Design and evaluation of PEGylated liposomal formulation of a novel multikinase inhibitor for enhanced chemosensitivity and inhibition of metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Bioconjug. Chem. 30(10), 2703–2713 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mondal SK, Jinka S, Pal K et al. Glucocorticoid receptor-targeted liposomal codelivery of lipophilic drug and anti-Hsp90 gene: strategy to induce drug-sensitivity, EMT-reversal, and reduced malignancy in aggressive tumors. Mol. Pharm. 13(7), 2507–2523 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meka RR, Godeshala S, Marepally S et al. Asymmetric cationic lipid based non-viral vectors for an efficient nucleic acid delivery. RSC Adv. 6(81), 77841–77848 (2016). [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrates that a asymmetric associated based liposomes show superior cellular localization and transfection efficiency compared with its symmetric lipids.

- 22.Rachamalla HKR, Mondal SK, Deshpande SS et al. Efficient anti-tumor nano-lipoplexes with unsaturated or saturated lipid induce differential genotoxic effects in mice. Nanotoxicology 13(9), 1161–1175 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Clearly delineates the importance of incorporating single unsaturated aliphatic chain in lipid toward developing efficient antitumor nano-lipoplexes with reduced genotoxicity.

- 23.Jinka S, Rachamalla HK, Bhattacharyya T et al. Glucocorticoid receptor-targeted liposomal delivery system for delivering small molecule ESC8 and anti-miR-Hsp90 gene construct to combat colon cancer. Biomed. Mater. 16(2), 024105 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alkharfy KM, Ahmad A, Khan RMA, Al AM. High-performance liquid chromatography of thymoquinone in rabbit plasma and its application to pharmacokinetics. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 36(16), 2242–2250 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad A, Khan RMA, Alkharfy KM. Development and validation of RP-HPLC method for simultaneous estimation of glibenclamide and thymoquinone in rat plasma and its application to pharmacokinetics. Acta. Chromatogr. 27(3), 435–448 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Najjar N, Ketola RA, Nissilä T et al. Impact of protein binding on the analytical detectability and anticancer activity of thymoquinone. J. Chem. Biol. 4(3), 97–107 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rathore C, Upadhyay NK, Sharma A, Lal UR, Raza K, Negi P. Phospholipid nanoformulation of thymoquinone with enhanced bioavailability: development, characterization and anti-inflammatory activity. J. Drug. Deliv. Sci. Technol. 52, 316–324 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ballout F, Habli Z, Rahal ON, Fatfat M, Gali-Muhtasib H. Thymoquinone-based nanotechnology for cancer therapy: promises and challenges. Drug Discov. Today 23(5), 1089–1098 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sercombe L, Veerati T, Moheimani F, Wu SY, Sood AK, Hua S. Advances and challenges of liposome assisted drug delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 6, 286 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yingchoncharoen P, Kalinowski DS, Richardson DR. Lipid-based drug delivery systems in cancer therapy: what is available and what is yet to come. Pharmacol. Rev. 68(3), 701–787 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Far AH, Tantawy MA, Al Jaouni SK, Mousa SA. Thymoquinone-chemotherapeutic combinations: new regimen to combat cancer and cancer stem cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 393(9), 1581–1598 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bashmail HA, Alamoudi AA, Noorwali A et al. Thymoquinone synergizes gemcitabine anti-breast cancer activity via modulating its apoptotic and autophagic activities. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 11674 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gauri RV, Robert AW. Current and evolving therapies for metastatic pancreatic cancer: are we stuck with cytotoxic chemotherapy? J. Oncol. Pract. 12(9), 797–805 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ong YS, Saiful Yazan L, Ng WK et al. Acute and subacute toxicity profiles of thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier in BALB/c mice. Int. J. Nanomedicine 11, 5905–5915 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mostofa AGM, Hossain MK, Basak D, Bin Sayeed MS. Thymoquinone as a potential adjuvant therapy for cancer treatment: evidence from preclinical studies. Front. Pharmacol. 8(295), (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh A, Ahmad I, Akhter S et al. Nanocarrier based formulation of thymoquinone improves oral delivery: stability assessment, in vitro and in vivo studies. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 102, 822–832 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.