Abstract

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis has revealed extremely high abundances of rearranged hopanes in Jurassic source rocks and related crude oils in the center of the Sichuan Basin. The detected rearranged hopanes include 17α(H)-diahopanes (C27D and C29–35D), early-eluting rearranged hopanes (C27E and C29–33E), and 18α(H)-neohopanes (C29Ts and Ts). Both the 17α(H)-diahopanes and the early-eluting rearranged hopanes exhibit a distribution pattern similar to that of the 17α(H)-hopane series, with a predominance of the C30 member and the presence of 22S and 22R epimers of hopanes in the extended series (>C30). The results of this study show that the relatively high abundance of rearranged hopanes in Jurassic source rocks in the study area is associated with their depositional environments and with clay-mediated acidic catalysis rather than, as was previously thought, thermal maturity. Shallow lacustrine facies with brackish water and a suboxic to weak reducing sedimentary environment have contributed to the enrichment of rearranged hopanes, and clay-mediated acidic catalysis may also have had a positive influence on their abundance. The distribution patterns of the diahopane series indicate that the oils from Jurassic reservoirs in the Gongshanmiao Oilfield are sourced from Jurassic source rocks. Rearranged hopanes are therefore considered to be effective biomarkers for oil-source correlation in the center of the Sichuan Basin.

1. Introduction

“Rearranged hopanes” refer to a series of biomarkers that have the same carbon skeleton as the 17α(H)-hopane series (H series) but with different alkyl side chains. Four series of rearranged hopanes have been detected in oils and sediments, including 17α(H)-diahopanes (D series), early-eluting series (E series), 21-methyl-28-norhopanes (Nsp), and 18α(H)-neohopanes (Ts series). The 18α(H)-22,29,30-trisnorneohopane (Ts) biomarker was initially identified by means of X-ray.1 Subsequently, Moldowan et al. detected another, 18α(H)-neohopane (C29Ts), using NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) spectroscopy.2 It was considered that the precursors of 18α(H)-neohopanes were likely to be C29 hopanoids, or diploptene and diplopterol because of the limited carbon number distribution.3 Using X-ray crystallography techniques and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry (GC-MS-MS), 17α(H)-diahopanes were detected in oils from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, with similar carbon numbers to those of 17α(H)-hopanes.2 Importantly, a number of unidentified early-eluting rearranged hopanes were identified in lacustrine crude oils.4 Farrimond and Telnes found that the distribution of early-eluting rearranged hopanes is comparable with that of 17α(H)-diahopanes and 17α(H)-hopanes, with sequential carbon numbers from C27 to C35 (but with C28E missing).5 Nytoft et al. synthesized the C30 member in the laboratory. The process used for the synthesis may be similar to the manner in which rearranged hopanes are formed in geological conditions.6 In addition, 21-methyl-28-norhopanes, ranging from C29 to at least C34, were identified by Nytoft et al., with C29Nsp predominating.7

Research, of which there has been a great deal, has tended to focus on the precursors of diahopanes. Nevertheless, their origins and formation mechanisms remain controversial. Because they were first observed in terrigenous oils and coals, 17α(H)-diahopanes were initially regarded as terrestrial biomarkers8 and it was assumed that their biological precursors were bacteria due to their similarity to regular hopanes in carbon isotope composition.2 Killops and Howell suggested that diahopanes may have originated from higher plant material, which had been reworked by particular types of bacteria in favorable depositional environments.4 However, Zhang et al. proposed that some specific algae (such as Rhodophytes) may also have been sources of rearranged hopanes.9 It is now generally believed that rearranged hopanes most probably arose from bacterial precursors through a process of clay-mediated acidic catalysis in suboxic to oxic depositional environments.5 Molecular mechanics calculations have suggested that the thermal stabilities of rearranged hopanes follow the order 17α(H)-diahopanes > 18α(H)-neohopanes > 17α(H)-hopanes,2 implying that thermal maturity may contribute to their enrichment.10 However, further calculations have indicated that the relative thermal stabilities of C30-rearranged hopanes are in the order C30 17α(H)-diahopane > C30 17α(H)-hopane > C30 early-eluting rearranged hopane, suggesting that relatively low maturity may also contribute to the generation of rearranged hopanes.11 Following the identification and classification of rearranged hopanes, their potential applications have become a subject of growing interest in geochemical studies. Li et al. suggested that C30 17α(H)-diahopane can be an effective indicator for maturity assessment, having observed that the C30 17α(H)-diahopane/(C30 17α(H)-hopane + C30 17α(H)-diahopane) ratios of source rocks in the Fushan Depression, in the South China Sea, increased with burial depth.12 The 18α(H)-neohopane series have also been widely used as indicators for maturity evaluation (for example, Ts/(Ts + Tm) and C29Ts/(C29H + C29Ts)).13 The 17α(H)-diahopane series and C29Ts have been widely applied in oil family classification and oil-source correlation.14

Three relatively high-abundance series of rearranged hopanes have been detected in oils from Jurassic reservoirs in the Shilongchang Oilfield in the center of the Sichuan Basin.15 However, the distribution characteristics of diahopanes in Jurassic source rocks remain unknown, which has hindered oil-source correlation in the study area. This study has investigated both the distribution patterns and the principal factors affecting the abundance of rearranged hopanes in Jurassic source rocks. Moreover, based on the systematic oil-source correlation in the study area using various biomarkers, the reliability of using different series of diahopanes as molecular indicators for oil-source correlation has been investigated and the results validated.

2. Geological Setting

The Sichuan Basin, in southwest China, is a huge gas-bearing basin. The periphery of the basin is delineated by Daba Mountain, Longmen Mountain, and Micang Mountain and it has an area of about 230 000 km2.16 The study area is located in the center of the basin. Currently discovered oil reserves in the study area are primarily in the Zhongtaishan, Gongshanmiao, Lianchi, Jinhua, and Guihua oil and gas fields, with the Jurassic as the principal oil-producing horizon (Figure 1a).17,18 Many oil- and gas-bearing structures, such as the Bajiaochang, Qiulin, and Nancong structures, have been discovered in the study area, which therefore has great potential for further exploration.

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of the main oil- and gas-bearing structures (a), and the schematic stratigraphic column of Jurassic strata (b) in the center of the Sichuan Basin, China.

The Sichuan Basin was considered to be a typical superposed basin composed of Precambrian to Middle Triassic marine strata and Late Triassic to Tertiary continental strata.19 Source rocks below the Late Triassic have entered the gas-generating stage.20 In contrast, the Jurassic source rocks are still within the maturity stage of oil generation. Vertically, there are five major oil and gas reservoirs in the study area: the Zhenzhuchong Member, the Dongyuemiao Member, the Da’anzhai Member in the Ziliujing Formation, the Lianggaoshan Formation, and the Shaximiao Formation (Figure 1b). The Da’anzhai Member of the Ziliujing Formation and the Lianggaoshan Formation are the main source rocks.

The Da’anzhai Member is composed of continental lacustrine sediments.21 It is divided into three submembers on the basis of variations in rock type (Da3, Da13, and Da1 from bottom to top).22 The source rocks of the Da’anzhai Member in the Ziliujing Formation are primarily located in the Da13 submember. They have good hydrocarbon generation capacity, with primarily Type II kerogen and average TOC (total organic carbon content) of more than 1.0%.18 The vitrinite reflectance of Da’anzhai Member source rocks ranges from 0.9 to 1.5%,20 implying good oil generation properties. The Lianggaoshan Formation, which is primarily composed of littoral to lacustrine sediments,23 is also divided into two members, the lower (J1l1) and upper (J1l2) members. The source rocks for the formation are mainly located in the upper member with an average TOC of more than 1.0%.17

3. Samples and Experiments

Twenty-two representative Early Jurassic core samples were collected from the Da’anzhai Member (12 samples) and the Lianggaoshan Formation (10 samples). For comparison, five source rocks from the Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation and eight oils from Jurassic reservoirs in the Gongshanmiao Oilfield were also analyzed. Detailed information on the Jurassic source rocks is given in Table 1, and the locations of source rocks and crude oil wells are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1. Selected Geochemical Parameters for Representative Jurassic Rock Extracts from the Central of Sichuan Basina.

| no. | well | depth (m) | Fm. | lithology | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | G17 | 2468.6 | J1l | mudstone | 0.66 | 2.01 | 0.44 | 1.53 | 0.57 | 0.91 | 6.65 | 0.74 | 1.47 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 2.76 | 51.5 | 24.4 | 24.1 | 17.9 | 21.9 | 60.1 |

| 2 | G17 | 2472.0 | J1l | mudstone | 0.52 | 1.31 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 6.19 | 0.75 | 1.80 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 1.98 | 42.4 | 29.6 | 27.9 | 16.0 | 18.8 | 65.2 |

| 3 | G17 | 2472.5 | J1l | mudstone | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.64 | 1.46 | 5.71 | 0.78 | 1.75 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.38 | 46.5 | 23.3 | 30.2 | 28.1 | 26.6 | 45.3 |

| 4 | G17 | 2487.7 | J1l | mudstone | 0.47 | 1.70 | 0.34 | 1.38 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 6.86 | 0.76 | 1.54 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 2.21 | 59.4 | 20.7 | 19.9 | 22.4 | 18.3 | 59.3 |

| 5 | G17 | 2503.9 | J1l | mudstone | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 4.77 | 0.81 | 2.83 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 55.4 | 20.1 | 24.4 | 18.5 | 16.9 | 64.6 |

| 6 | G1 | 2239.9 | J1l | mudstone | 0.44 | 1.76 | 0.36 | 1.80 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 6.39 | 0.74 | 1.85 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 1.10 | 51.4 | 22.1 | 26.5 | 23.7 | 23.9 | 52.4 |

| 7 | G1 | 2247.6 | J1l | mudstone | 0.39 | 1.55 | 0.34 | 1.76 | 0.56 | 0.94 | 5.44 | 0.74 | 2.08 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.98 | 48.5 | 22.3 | 29.2 | 23.8 | 19.8 | 56.4 |

| 8 | G1 | 2248.4 | J1l | mudstone | 0.46 | 1.92 | 0.40 | 2.22 | 0.55 | 0.99 | 5.65 | 0.73 | 2.10 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 1.68 | 46.5 | 24.5 | 29.0 | 24.7 | 18.4 | 56.9 |

| 9 | G1 | 2340.7 | J1dn | mudstone | 0.16 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.94 | 5.44 | 0.74 | 1.48 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 37.4 | 30.4 | 32.2 | 26.1 | 26.1 | 47.8 |

| 10 | G1 | 2377.3 | J1dn | mudstone | 0.61 | 1.60 | 0.53 | 1.83 | 0.51 | 1.03 | 4.83 | 0.71 | 1.53 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 2.38 | 42.2 | 24.3 | 33.6 | 24.5 | 28.9 | 46.6 |

| 11 | G1 | 2381.1 | J1dn | mudstone | 1.41 | 3.50 | 0.70 | 2.31 | 0.61 | 1.13 | 8.59 | 0.76 | 1.47 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 1.91 | 50.0 | 24.2 | 25.7 | 17.4 | 23.2 | 59.4 |

| 12 | LH2 | 2520.0 | J1l | mudstone | 8.24 | 21.67 | 3.17 | 7.41 | 1.10 | n.d. | 25.38 | 1.06 | 1.60 | 0.1 | 0.17 | n.d. | 1.61 | 59.1 | 22.6 | 18.3 | 27.6 | 16.9 | 55.5 |

| 13 | LH2 | 2545.2 | J1l | mudstone | 0.14 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.61 | n.d. | 10.33 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 22.0 | 30.1 | 47.9 | 35.0 | 25.9 | 39.1 |

| 14 | X28 | 1977.1 | J1dn | mudstone | 0.19 | 0.77 | 0.09 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 4.89 | 0.67 | 2.00 | 0.1 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.59 | 34.0 | 30.2 | 35.8 | 22.7 | 29.1 | 48.2 |

| 15 | X28 | 1980.5 | J1dn | mudstone | 0.25 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.75 | 5.90 | 0.68 | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 1.11 | 44.2 | 28.9 | 26.9 | 23.0 | 20.5 | 56.5 |

| 16 | X28 | 2015.5 | J1dn | mudstone | 0.91 | 2.58 | 0.49 | 1.54 | 0.58 | 1.14 | 8.47 | 0.75 | 1.02 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 50.5 | 25.3 | 24.2 | 26.6 | 24.3 | 49.1 |

| 17 | P10 | 1998.0 | J1dn | shale | 1.44 | 5.66 | 0.79 | 3.28 | 0.46 | 1.17 | 1.95 | 0.68 | 1.23 | 0.16 | 0.2 | n.d. | 2.41 | 49.1 | 24.5 | 26.4 | 19.4 | 11.7 | 68.9 |

| 18 | P10 | 2007.5 | J1dn | shale | 1.63 | 5.10 | 0.92 | 2.56 | 0.47 | 1.25 | 2.48 | 0.68 | 1.75 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 4.53 | 51.7 | 23.5 | 24.7 | 19.7 | 13.4 | 66.9 |

| 19 | P10 | 2026.3 | J1dn | shale | 1.27 | 5.43 | 1.01 | 5.71 | 0.62 | n.d. | 8.10 | 0.77 | 1.66 | 0.1 | 0.16 | 0.39 | 4.20 | 45.0 | 27.3 | 27.7 | 23.6 | 14.0 | 62.4 |

| 20 | P103 | 1672.5 | J1dn | shale | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 13.87 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 15.2 | 24.3 | 60.4 | 32.0 | 28.2 | 39.8 |

| 21 | P103 | 1696.6 | J1dn | shale | 0.33 | 1.83 | 0.26 | 2.27 | 0.88 | 2.22 | 14.13 | 0.93 | 1.44 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.34 | 1.39 | 35.4 | 28.8 | 35.8 | 18.7 | 33.8 | 47.6 |

| 22 | L104x | 3533.7 | J1dn | mudstone | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.85 | n.d. | 7.40 | 0.91 | 1.10 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 16.5 | 28.6 | 54.9 | 36.4 | 26.5 | 37.0 |

Note: (1) C29D/C30H; (2) C30D/C30H; (3) C29E/C30H; (4) C30E/C30H; (5) MPI-1 = 1.5 × (2-MP + 3-MP)/(P + 1-MP + 9-MP); (6) MNR = 2-MN/1-MN; (7) MDR = [4-MDBT]/[1-MDBT]; (8) Rc % = 0.6 × MPI-1 + 0.4; (9) Pr/Ph; (10) Ph/nC18; (11) Pr/nC17; (12) Ga/C30H; (13) C2713α(H),17β(H),20R-diasterane/C275α(H),14α(H),17α(H),20R-sterane; (14) C19+20TT (%); (15) C21TT (%); (16) C23TT (%); (17) C27αααR-/C27–C29αααR-steranes; (18) C28αααR-/C27–C29αααR-steranes; (19) C29αααR-/C27–C29αααR-steranes. TT = tricyclic terpane; H = 17α(H),21β(H)-hopanes; D = 17α(H)-diahopane; E = early-eluting rearranged hopane; nd = not determined.

All of the cores were crushed into powders with particle diameters of less than 0.2 mm (80 mesh). The powdered samples (≈60 g) were extracted for 72 h using a Soxhlet apparatus with 500 mL of a dichloromethane and methyl alcohol mixture (93:7, v–v) to obtain soluble bitumen. Asphaltene precipitation of the extracts and oils was achieved by adding an excessive volume of n-hexane. After filtration, the deasphalted maltene fraction was fractionated into saturate, aromatic, and resin fractions in a silica gel/alumina column, sequentially using n-hexane, dichloromethane/n-hexane (2:1, v–v), and dichloromethane/methyl alcohol (9:1, v–v).

GC-MS analysis of the saturate and aromatic hydrocarbon fractions was carried out using an Agilent 6890GC/5975iMSD instrument coupled with an HP-5MS fused silica capillary column. Helium was utilized as the carrier gas for GC. The process for GC analysis of the saturated fractions was as follows: the initial oven temperature was 50 °C, then increased to 120 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min, programmed to 310 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min, and finally held at 310 °C for 25 min. For the aromatic fractions, the initial oven temperature was also 50 °C, then programmed to 310 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min and held at 310 °C for 16 min. The MS ion source was operated at 70 eV.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Identification of Rearranged Hopanes

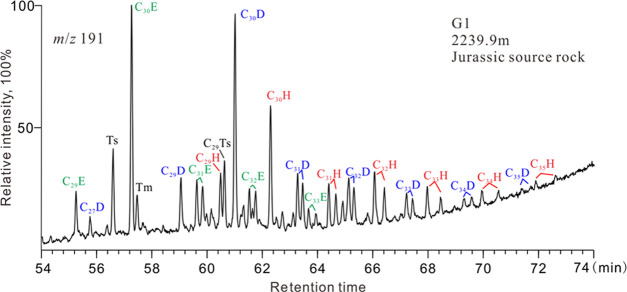

Jurassic oils from the Shilongchang Oilfield in the center of the Sichuan Basin have been found to contain three series of rearranged hopanes: 17α(H)-diahopanes, 18α(H)-neohopanes (Ts and C29Ts), and early-eluting rearranged hopanes.15 These three series of rearranged hopanes were also detected in both Jurassic source rock extracts and in crude oils in this study, as confirmed by comparison of elution sequences, retention times, and mass spectra with those described in the previous literature.5,15 The most abundant diahopanes in the samples in this study are 17α(H)-diahopanes, which have similar distribution patterns to the 17α(H)-hopane series, including the predominance of the C30 isomer and the presence of 22S and 22R epimers of C31–C35 members. The carbon numbers of the 17α(H)-diahopanes range from C27 to C35 but with very low abundance of C28 and C35 homologues (Figure 2). It is clear from m/z 191 mass chromatograms that the carbon number range of early-eluting rearranged hopanes (Figure 2) is similar to that of 17α(H)-diahopanes and 17α(H)-hopanes. The early-eluting rearranged hopanes, with carbon numbers ranging from C29 to C33, also contain 22S and 22R epimers of C31–C33 homologues. In source rock extracts, the neohopane series, which has a markedly lower abundance than that of 17α(H)-diahopanes, comprises mainly C27 and C29 members (Ts and C29Ts).

Figure 2.

Mass chromatogram (m/z 191) showing the distribution of rearranged hopanes in representative Jurassic source rock sample in the center of the Sichuan Basin. Notes: H = 17α(H),21β(H)-hopane; D = 17α(H)-diahopane; E = early-eluting rearranged hopane.

The mass spectrum of C30-17α(H),21β(H)-diahopane (C30D) exhibits very similar characteristics to that of C30-early-eluting rearranged hopane (C30E), with M+ 412 as the molecular peak and m/z 191 as the base peak (see also ref (24)). The m/z 287 ions in the mass spectrum may be derived from the cleavage of B-rings of C30E.25 The relative abundance of m/z 287 ions in the mass spectra can therefore be used to distinguish between C30E and C30D (Figure 3a,b). In addition, the mass spectrum of C29D shows many similarities to that of C29E, with M+ 412 as the molecular peak, a base peak of m/z 191, and diagnostic fragment ions at m/z 383, 217, and 177 (Figure 3c,d). The similarity between the molecular structures of 17α(H)-diahopanes and those of the early-eluting rearranged hopane series may imply an affinity in origin among these rearranged hopanes.

Figure 3.

Mass spectra of the C30 member of 17α(H)-diahopane and early-eluting rearranged hopane (a, b); C29 member of 17α(H)-diahopane and early-eluting rearranged hopane (c, d). All taken from the same full-scan GC-MS analysis of a single source rock sample (G17, 2472.0 m) from the center of the Sichuan Basin.

4.2. Distribution Characteristics of Rearranged Hopanes

The distribution patterns of rearranged hopanes in Jurassic source rocks on the m/z 191 mass chromatogram fall into three main types. Pattern A: abundance of regular hopanes is higher than that of rearranged hopanes, with the C30D/C30H value ranging from 0.06 to 0.85 (Figure 4a). Pattern B: rearranged hopanes predominate over regular hopanes (Figure 4b), with the C30D/C30H value ranging from 1.31 to 5.66. Pattern C: regular hopanes are below the detection limit, but unusually high abundances of the rearranged hopane series are present (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Representative partial m/z 191 mass chromatograms of the saturate fractions showing the distribution of rearranged hopanes in source rocks from well G17 (a, b) and LH2 (c) in the center of the Sichuan Basin.

The abundance of C30 early-eluting rearranged hopane shows a strong linear correlation with that of C30 17α(H)-diahopane.5,10,26 Likewise, all the relative abundance parameters (C29D/C30H, C30D/C30H, C29E/C30H, C30E/C30H) in the study area show similar tendencies in relation to burial depth (Figure 5). This observation suggests that the early-eluting rearranged hopanes may have biological precursors similar to those of 17α(H)-diahopanes.11 However, the biological precursors of the early-eluting rearranged hopanes are still obscure. It is also worth noting that the abundances of rearranged hopanes exhibit great heterogeneity in the vertical section in Jurassic source rocks. As shown in Figure 5, the relative abundance of the different rearranged hopanes fluctuates frequently and markedly in both P103 and G17 profiles. The C30D/C30H ratio (>1.3) in a source rock sample collected at a depth of 2472 m in well G17 is several times higher than that of a sample from a depth of 2472.5 m. A similar phenomenon was also observed in the Yabulai Basin, northwest China.27

Figure 5.

Depth-trend plot of C29D/C30H, C30D/C30H, C29E/C30H, C30E/C30H, and C29Ts/C30H in Jurassic source rock extracts from wells G17 and G103 in the center of the Sichuan Basin.

4.3. Factors Controlling the Distribution of Rearranged Hopanes in Source Rocks

4.3.1. Thermal Maturity

Molecular calculations indicate that 17α(H)-diahopane should be more stable than 17α(H)-hopane.2 The ratio of C30D/C30H has been suggested to be a maturity parameter, particularly in the late oil window. In the Fushan Depression, in the South China Sea, the C30D/(C30D + C30H) ratios of oils correlate fairly well with other maturity indicators, such as methylphenanthrene index (MPI-1), methyldibenzothiophene ratio (MDR), and dimethylnaphthalene ratio (DNR).12 Similarly, the C30D/C30H ratios of oils from the Songliao Basin, China, tend to increase with thermal maturity.10 Nevertheless, the relative abundance of 17α(H)-diahopane in rock extracts and oils from the Yanchang Formation may be primarily controlled by its sedimentary environment and lithology rather than thermal maturity.28 Although thermal evolution can contribute to the generation of rearranged hopanes, it is not the only factor affecting their abundance in source rocks and related crude oils. Moreover, the critical factors influencing the abundance of rearranged hopanes may vary from region to region.

The Jurassic Linggaoshan Formation and the Da’anzhai Member have been proved to be the primary source rocks in the center of the Sichuan Basin.20 With calculated vitrinite reflectance (Rc %) ranging from 0.67 to 1.06% (Table 1), the Jurassic source rocks in the center of the Sichuan Basin are at the peak of hydrocarbon generation. As shown in Figure 6, neither C30D/C30H nor C30E/C30H in source rocks exhibits any correlation with MPI-1, MNR, or MDR, which have hitherto been universally used as indicators of thermal maturity.29−31 The actual values of MPI-1, MNR, and MDR of source rocks from well G17 show very little variation, at around 0.62, 0.88, and 6.04, respectively (Table 1). However, the abundances of rearranged hopanes in the same source rocks show considerable differences, implying that thermal maturity is not the major factor controlling the enrichment of rearranged hopanes in the Jurassic source rock extracts in the study area.

Figure 6.

Cross-plots showing the correlations between (a) C30D/C30H vs MPI-1; (b) C30E/C30H vs MPI-1; (c) C30D/C30H vs MNR; (d) C30E/C30H vs MNR; (e) C30D/C30H vs MDR; and (f) C30E/C30H vs MDR. Notes: MPI-1 = 1.5 × (2-MP + 3-MP)/(P + 1-MP + 9-MP); MNR = 2-MN/1-MN; MDR = 4-/1-MDBT; MN = methylnaphthalene; MP = methylphenanthrene. MDBT = methyldibenzothiophene.

4.3.2. Depositional Environment

Extensive research has suggested that enrichment of rearranged hopanes is affected by the water salinity and redox conditions of their sedimentary environment.10,28 The Pr/nC17 and Ph/nC18 ratios are commonly used to determine the organic matter types and redox conditions of sedimentary environments as well as the thermal maturity of the source rocks and related oils.32,33 The Pr/nC17 and Ph/nC18 ratios of Jurassic source rocks range from 0.1 to 0.37 and 0.08 to 0.35 (Table 1), respectively, indicating that most of the Jurassic source rock samples in this study were deposited in a transitional environment with mixed organic matter input.34 The pristane/phytane ratio (Pr/Ph) has been widely applied to distinguish different depositional environments of source rocks.35 In general, a low Pr/Ph ratio (<0.8) indicates an anoxic sedimentary environment, while a high Pr/Ph ratio (>3.0) suggests oxic conditions with relatively high terrigenous organic matter input.13 In this study, the Pr/Ph ratios of Jurassic source rocks range from 0.54 to 2.83, with an average of 1.55, indicating a suboxic to weak reducing environment. As shown in Figure 7, a relatively high abundance of rearranged hopanes seems to be generated when Pr/Ph is in the range 1.0–2.1 (see also ref (36)), implying that rearranged hopanes may be generated in suboxic to weak reducing depositional environments.

Figure 7.

Cross-plots showing the correlations between (a) C30D/C30H and Pr/Ph; and (b) C30E/C30H and Pr/Ph.

The presence of gammacerane suggests water column stratification in the sedimentary environment, which generally arises in hypersaline conditions.37 For this reason, the ratio of Ga/C30H (gammacerane index) is widely used to assess the salinity of water. In the Songliao Basin, China, a positive correlation was found between the gammacerane index and the abundance of diahopanes in crude oils.10 Similarly, Jin et al. suggested that the relatively high abundance of 17α(H)-diahopanes in extracts from the Yabulai Basin, northwest China, is the result of a brackish water depositional environment.27 In the present study area, the abundances of 17α(H)-diahopanes and early-eluting rearranged hopanes in the Jurassic source rocks generally increase with the increase of Ga/C30H values (Figure 8). Based on the study of major elements and trace elements, the Jurassic source rocks were evidenced to be deposited in a shallow lake, with fluctuating depth, in fresh to saline water conditions.38 Therefore, a saline water depositional environment may have promoted the enrichment of rearranged hopanes in the center of the Sichuan Basin.

Figure 8.

Cross-plots showing the correlation between (a) C30D/C30H and Ga/C30H; and (b) C30E/C30H and Ga/C30H of source rock in the center of the Sichuan Basin.

4.3.3. Acidic Catalysis

The precursors of hopanes, such as diplopterol and bacteriohopanetetrol, are important components of bacterial cell membranes.39 The relative abundance of 17α-hopanes often reflects the input of prokaryotic organisms. Xiao et al. proposed a general biosynthetic/diagenetic scheme showing the generation of 17α-hopane and diahopanes.11 As shown in Figure 9a, both 17α-diahopanes and early-eluting rearranged hopanes may have similar precursors to the bacteria-derived 17α-hopanes.11 The observations made in this study support this mechanism, with the relative abundances of 17α-diahopanes and early-eluting rearranged hopanes showing a significant negative correlation with that of 17α-hopanes in Jurassic source rock extracts in the study area (Figure 9b,c). Biosynthetic reaction schemes indicate that acidic catalysis plays an important role in the formation of rearranged hopanes (see also ref (6)).

Figure 9.

Scheme for the generation of diahopanes (a),11 a and cross-plots showing a correlation between (b) C30H/(C30H + C30D + C30E) and C30D/(C30H + C30D + C30E); and (c) C30H/(C30H + C30D + C30E) and C30E/(C30H + C30D + C30E) of source rocks in the center of the Sichuan Basin. 1: Bacteriohopanepolyols, 2: hopa-17(21),22(29)-diene, 3: hopa-16,21-diene, 4: hopa-15,17(21)-diene, 5: 17α-hopane (C30H), 6: 17α-diahop-13-ene, 7: 17α-diahopane (C30D), 8: 9,15-dimethy-25,27-bisnorhop-5(10)-ene, and 9: 9,15-dimethy-25,27-bisnorhopane (C30E). a Reprinted in part with permission from [Org. Geochem. 2019, 138, 1–11]. Copyright [2019] [Organic Geochemistry].

Diasteranes are considered to be products of acid-catalyzed backbone conversion of sterols during diagenesis.40 High diasteranes/steranes ratios are typical characteristics of petroleum generated from clay-rich source rocks.13 High maturity may also result in high diasteranes/steranes ratios in source rock extracts and crude oils.41−43 Jurassic source rocks with similar maturity show great differences in relative abundances of diasteranes (Table 1), indicating that maturity is not the main factor affecting the abundance of diasteranes. As shown in Figure 10, the abundances of 17α-diahopanes and early-eluting rearranged hopanes correlate with the abundance of rearranged hopanes, suggesting that acidic catalysis may be one of the factors affecting the generation and enrichment of diasteranes and rearranged hopanes in the study area.

Figure 10.

Cross-plots showing correlations between (a) C30D/C30H and C27αβ,20R-diasterane/C27ααα,20R-sterane; and (b) C30E/C30H and C27αβ,20R-diasterane/C27ααα,20R-sterane. Note: C27αβ,20R-diasterane/C27ααα,20R-sterane = C2713α(H),17β(H),20R-diasterane/C275α(H),14α(H),17α(H),20R-sterane.

It is not thermal maturity but a suboxic to weak reducing sedimentary environment with saline water that contributes to the enrichment of rearranged hopane in Jurassic source rock extracts. Clay-mediated acidic catalysis may be another key factor affecting the generation of rearranged hopanes in the study area. Confusingly, the abundances of rearranged hopanes in source rocks from many other basins are much lower than in those of the Sichuan Basin, even in basins with similar depositional environments and maturation levels.26−28 Perhaps a bloom of aquatic life, or some other biological group, in the early Jurassic in the study area had some influence on the enrichment of diahopanes.15 Although the mechanism causing such a high abundance of rearranged hopanes remains unclear, the study of the geochemical characteristics of rearranged hopanes may have significant implications for oil-source correlation in the study area.

4.4. Rearranged Hopanes as Indicators of Oil-Source Correlation in the Gongshanmiao Oilfield

Apart from the Da’anzhai Member and Lianggaoshan Formation, the Xujiahe Formation (especially, T3x1, T3x3, and T3x5) was proven to be an important source rock in the center of the Sichuan Basin, with TOC and Ro % ranging from 0.5 to 9.7% and 0.8 to 2.6%, respectively.44 Tricyclic terpanes (TTs) are commonly observed in source rock extracts and crude oils from a number of sedimentary basins. Previous studies have indicated that distribution patterns of tricyclic terpanes are mainly controlled by the sedimentary environment and organic composition.45 Generally, C19TT and C20TT are abundant in terrestrial oils and source rocks with relatively high input of terrigenous organisms,46,47 whereas C23TT tends to predominate in typical marine oils and saline lacustrine oils.48,49 As shown in Figure 11a, Jurassic source rocks and oils exhibit similar distribution patterns for C19TT to C23TT, with C19+20TT predominating. However, T3x source rocks present a remarkably different distribution of tricyclic terpanes, with a significantly higher abundance of C23TT.

Figure 11.

Ternary diagram of C19+20TT, C21TT, and C23TT (a),50 a and C27, C28, and C29 regular steranes (b) in source rocks and crude oils from the center of the Sichuan Basin. C27(%): C27αααR-/C27-C29αααR-steranes; C27(%): C28αααR-/C27-C29αααR-steranes; and C29(%): C29αααR-/C27-C29αααR-steranes. a Adapted with permission from [Geochimica2019, 2, 1–10]. Copyright [2019] [Geochimica].

The distribution of C27–C29 regular steranes has been widely used in oil-source correlation and for classifying oil families.13 Regular steranes in Jurassic source rock extracts are characterized by a predominance of C29 steranes, accounting for 37.0–68.9% of C27–C29 homologues. In contrast, T3x source rocks present a distribution pattern of steranes, with similar abundances of C27 and C29 steranes and a lower abundance of C28 steranes (Table 1). A ternary diagram of C27–C29 regular steranes illustrates that data points of Jurassic source rocks and oils all fall within the same area (Figure 11b). It can therefore be presumed that there is a close genetic correlation between oils from the Gongshanmiao Oilfield and Jurassic source rocks in the center of the Sichuan Basin.

Rearranged hopanes have stronger thermostability and biodegradation resistance than 17α(H)-hopanes,2 so rearranged hopanes have frequently been used in oil-source correlation studies.28 High abundances of rearranged hopanes—including 17α(H)-diahopanes, early-eluting rearranged hopanes, and 18α(H)-neohopanes—have also been detected in oils from the Gongshanmiao Oilfield. The distribution pattern of rearranged hopanes in oils is very similar to that found in Jurassic source rocks. However, Upper Triassic (T3x) source rock extracts are characterized by a predominance of 17α(H)-hopanes, with a relatively low abundance of rearranged hopanes (Figure 12). Furthermore, in a cross-plot of C29Ts/C30H vs C30D/C30H, the data points from the Jurassic source rocks and Jurassic oils from the Gongshanmiao Oilfield fall within the same zone (Figure 13). The oils from the Gongshanmiao Oilfield are therefore likely to be derived from Jurassic source rocks, a conclusion which is in agreement with correlation results using other conventional biomarkers. This confirms that rearranged hopanes are effective indicators for oil-source correlation in the study area.

Figure 12.

Representative m/z 191 mass chromatograms of the saturate fractions showing the distributions of rearranged hopanes in oils (a, b), Jurassic source rocks (c, d), and source rocks from Xujiahe Formation (e, f) in the center of the Sichuan Basin.

Figure 13.

Cross-plot of C29Ts/C30H and C30D/C30H ratios for source rock extracts and crude oils in the center of the Sichuan Basin.

5. Conclusions

Unusually high abundances of diahopanes were detected in Jurassic source rocks and related oils in the center of the Sichuan Basin, in Southwest China, including 17α(H)-diahopanes (D series), early-eluting rearranged hopanes (E series), and 18α(H)-neohopanes (Ts and C29Ts). The 17α(H)-diahopanes display distribution characteristics analogous to those of the 17α(H)-hopane series, with the C30 member predominating among C27–C35 homologues and the presence of two epimers of C31–C35 members (22S and 22R). The early-eluting rearranged hopanes only extend from C29 to C33 and exhibit a distribution pattern similar to that of the 17α(H)-hopane series, including a predominance of the C30 member and the presence of two epimers (22S and 22R) of the extended series (>C30). The 18α(H)-neohopanes, of which only C29Ts and Ts were detected, were present in relatively much lower concentrations than the other two series. Three source rock types can be distinguished according to their relative abundances of rearranged hopanes. These types are designated as patterns A, B, and C, with C30D/C30H ratios of 0.06–0.85, 1.31–5.66, and >10, respectively.

The relationship of rearranged hopanes to other biomarkers confirms that depositional environment rather than thermal maturation levels is the principal factor controlling the relative abundances of rearranged hopanes in Jurassic source rocks. Shallow lacustrine facies with suboxic to weak reducing environments and brackish water offer favorable conditions for the enrichment of rearranged hopanes. Clay-mediated acidic catalysis may also be a significant factor in promoting the generation of rearranged hopanes.

Systematic oil-source correlation of oils from the Gongshanmiao Oilfield has been carried out using a variety of indicators. The Jurassic source rocks are markedly different from the source rocks of the Xujiahe Formation in terms of the distribution characteristics of tricyclic terpanes, regular steranes, and rearranged hopanes in the study area. However, all of the characteristics of these indicators in Jurassic oils from the Gongshanmiao Oilfield correlate closely with those of the Jurassic source rock extracts, which strongly suggests that oils from the Gongshanmiao Oilfield are sourced from Jurassic source rocks. These results provide persuasive evidence that rearranged hopanes can be used as effective indicators for oil-source correlation in the center of the Sichuan Basin.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (Grant No. 41972148) and the National Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2016ZX05004-005). The authors would like to thank the Associate Editor Dr. Mohamed Mahmoud and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions that significantly improved the quality of the manuscript. The authors also thank the Exploration and Development Research Institute of Southwest Oil & Gas Field Company, PetroChina, for providing samples and data, and for permission to publish this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Whitehead E. V.The Structure of Petroleum Pentacyclances. In Advances in Organic Geochemistry; Tissot B.; Tissot B.; Bienner F., Eds.; Technip, 1973; pp 225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Moldowan J. M.; Fago F. J.; Carlson R. M. K.; Young D. C.; Duyne G. V.; Clardy J.; Schoell M.; Pillinger C. T.; Watt D. S. Rearranged hopanes in sediments and petroleum. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1991, 55, 3333–3353. 10.1016/0016-7037(91)90492-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Fu J.; Sheng G.; Xiao Q.; Li J.; Zhang Y.; Piao M. Geochemical characteristics and applications of 18α(H)-neohopanes and 17α(H)-diahopanes. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2000, 45, 1742–1748. 10.1007/BF02886257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Killops S. D.; Howell V. J. Complex series of pentacyclic triterpanes in a lacustrine 509 sourced oil from Korea Bay Basin. Chem. Geol. 1991, 91, 65–79. 10.1016/0009-2541(91)90016-K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrimond P.; Telnæs N. Three series of rearranged hopanes in Toarcian sediments (northern Italy). Org. Geochem. 1996, 25, 165–177. 10.1016/S0146-6380(96)00127-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nytoft H. P.; Lund K.; Kennet T.; Jørgensen C.; Thomsen J. V.; Sørensen S. W.; Lutnæs B. F. Identification of an early-eluting rearranged hopane series. Synthesis from hop 17(21)-enes and detection of intermediates in sediments. Abst. Rep. – Int. Congr. Org. Geochem. 2007, 23, 1017–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Nytoft H. P.; Lutnæs B. F.; Johansen J. E. 28-Nor-spergulanes, a novel series of rearranged hopanes. Org. Geochem. 2006, 37, 772–786. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Philp R. P.; Gilbert T. D. Biomarker distributions in Australian oils predominantly derived from terrigenous source material. Org. Geochem. 1986, 10, 73–84. 10.1016/0146-6380(86)90010-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Zhang B.; Bian L.; Jin Z.; Wang D.; Chen J. The Xiamaling oil shale generated through Rhodophyta over 800 Ma ago. Sci. China, Ser. D: Earth Sci. 2007, 50, 527–535. 10.1007/s11430-007-0012-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.; George S. C.; Zhang M. The occurrence and distribution of rearranged hopanes in crude oils from the Lishu Depression, Songliao Basin, China. Org. Geochem. 2018, 115, 205–219. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H.; Li M.; Wang W.; You B.; Liu X.; Yang Z.; Liu J.; Chen Q.; Uwiringiyimana M. Identification, distribution and geochemical significance of four rearranged hopane series in crude oil. Org. Geochem. 2019, 138, 103929 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2019.103929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Wang T.; Ju L.; Zhang M.; Hong L.; Ma Q.; Gao L. Biomarker 17α(H)- diahopane: a geochemical tool to study the petroleum system of a Tertiary lacustrine basin, Northern South China Sea. Appl. Geochem. 2009, 24, 172–183. 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2008.09.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters K. E.; Walters C. C.; Moldowan J. M.. The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers and Isotopes in Petroleum Exploration and Earth History, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2005; pp 475–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z.; Huang G.; Lu Y.; Zhang Q. Rearranged hopanes in oils from the Quele 1 Well, Tarim Basin, and the significance for oil correlation. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2004, 31, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.; Zhong R.; Cai X.; Luo Y. Composition and origin approach of rearranged hopanes in Jurassic oils of central Sichuan basin. Org. Geochem. 2007, 36, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Su K.; Lu J.; Zhang G.; Chen S.; Li Y.; Xiao Z.; Wang P.; Qiu W. Origin of natural gas in Jurassic Da’anzhai Member in the western part of central Sichuan Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 167, 890–899. 10.1016/j.petrol.2018.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Gao X.; Wang L.; Lu J.; Liu C.; Tang H.; Zhang H.; Huang Y.; Ni H. Factors controlling Oiliness of Jurassic Lianggaoshan tight sands in central Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2014, 41, 468–474. 10.1016/S1876-3804(14)60053-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Zhang H.; Lu J.; Yang Y.; Liu C.; Wang L.; Zou X.; Yang J.; Tang H.; Yao Y.; Huang Y.; Ni S.; Chen Y. Controlling factors of Jurassic Da’anzhai Member tight oil accumulation and high production in central Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2015, 42, 206–214. 10.1016/S1876-3804(15)30007-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He D.; Li D.; Zhang G.; Zhao L.; Fan C.; Lu R.; Wen Z. Formation and evolution of multi-cycle superposed Sichuan Basin, China. Sci. China: Chem. 2011, 46, 589–606. [Google Scholar]; (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Yang Y.; Yang J.; Yang G.; Tao S.; Ni C.; Zhang B.; He X.; Lin J.; Huang D.; Liu M.; Zou J. New research progress of Jurassic tight oil in central Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2016, 43, 954–964. 10.1016/S1876-3804(16)30113-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. Y.; Li J. Z.; Li D. H.; Gong C. M. The potential of tight oil resource in Jurassic Da’anzhai Formation of the Gongshanmiao oil field, central Sichuan Basin. Geol. China 2013, 40, 477–486. [Google Scholar]; (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Xu Q.; Ma Y.; Liu B.; Song X.; Su J.; Chen Z. Characteristics and control mechanism of nanoscale pores in lacustrine tight carbonates: Examples from the Jurassic Da’anzhai Member in the central Sichuan Basin, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2019, 178, 156–172. 10.1016/j.jseaes.2018.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qing Y.; Lu Z.; Wu J.; Yang J.; Zhang S.; Xiong C.; Liu J. Formation mechanisms of calcite cements in tight sandstones of the Jurassic Lianggaoshan Formation, northeastern Central Sichuan Basin. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2019, 66, 723–740. 10.1080/08120099.2018.1564935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Jiang L.; Chen X.; Zhang M. Identification of the four rearranged hopane series in geological bodies and their geochemical significances. Chin. J. Geochem. 2015, 34, 550–557. 10.1007/s11631-015-0065-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Feng Y.; Liu H.; Zhang L.; Zhao S. Geological characteristics and resource potential of lacustrine shale gas in the Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2013, 40, 454–460. 10.1016/S1876-3804(13)60057-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.; Zhang M. Geochemical characteristics and significances of rearranged hopanes in hydrocarbon source rocks, Songliao Basin, NE China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 131, 138–149. 10.1016/j.petrol.2015.04.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X.; Zhang Z.; Wu J.; Zhang C.; He Y.; Cao L.; Zheng R.; Meng W.; Xia H. Origin and geochemical implication of relatively high abundance of 17α(H)- diahopane in Yabulai basin, northwest China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 99, 429–442. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.10.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.; Liu G.; Feng Y. Geochemical significance of 17α(H)-diahopane and its application in oil-source correlation of Yanchang formation in Longdong area, Ordos basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2016, 71, 238–249. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radke M.; Welte D. H.; Willsch H. Maturity parameters based on aromatic hydrocarbons: Influence of organic matter type. Org. Geochem. 1986, 10, 51–63. 10.1016/0146-6380(86)90008-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radke M.; Leythaeuser D.; Teichmüller M. Relationship between rank and composition of aromatic hydrocarbons for coals of different origins. Org. Geochem. 1984, 6, 423–430. 10.1016/0146-6380(84)90065-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radke M.; Willsch H.; Leythaeuser D.; Teichmüller M. Aromatic components of coal: relation of distribution pattern to rank. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1982, 46, 1831–1848. 10.1016/0016-7037(82)90122-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters K. E.; Moldowan J. M.. The Biomarker Guide: Interpreting Molecular Fossils in Petroleum and Ancient Sediments; Prentice Hall, 1993; pp 1–363. [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam G. Significance of coniferous rain forests and related organic matter in generating commercial quantities of oil, Gippsland Basin, Australia. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 1985, 69, 1241–1254. 10.1306/AD462BC3-16F7-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam G. Significance of Coniferous Rain Forests and Related Organic Matter in Generating Commercial Quantities of Oil, Gippsland Basin, Australia. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 1985, 69, 1241–1254. 10.1306/AD462BC3-16F7-11D7-8645000102C1865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Didyk B. M.; Simoneit B. R. T.; Brassell S. C.; Eglinton G. Organic geochemical indicators of palaeoenvironmental conditions of sedimentation. Nature 1978, 272, 216–222. 10.1038/272216a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong T.; Zhang M. Effects of depositional environment on rearranged hopanes in lacustrine and coal measure rocks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 169, 785–795. 10.1016/j.petrol.2017.11.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinninghe Damsté J. S.; Kenig F.; Koopmans M. P.; Koster J.; Schouten S.; Hayes J. M.; de Leeuw J. W. Evidence for gammacerane as an indicator of water column stratification. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 1995, 59, 1895. 10.1016/0016-7037(95)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q.; Liu B.; Ma Y.; Song X.; Wang Y.; Xin X.; Chen Z. Controlling factors and dynamical formation models of lacustrine organic matter accumulation for the Jurassic Da’anzhai Member in the central Sichuan Basin, southwestern China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2017, 86, 1391–1405. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2017.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer M.; Bouvier P.; Ourisson G. Molecular evolution of biomembranes: Structural equivalents and phylogenetic precursors of sterols. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1979, 76, 847–851. 10.1073/pnas.76.2.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein I.; Sieskind O.; Albrecht P. Rearranged sterenes in a shale: occurrence and simulated formation. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1975, 1833–1836. 10.1039/p19750001833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moldowan J. M.; Sundararaman P.; Schoell M. Sensitivity of biomarker properties to depositional environment and/or source input in the Lower Toarcian of S. W. Germany. Org. Geochem. 1986, 10, 915–926. 10.1016/S0146-6380(86)80029-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brincat D.; Abbott G.. Some Aspects of the Molecular Biogeochemistry of Laminated and Massive Rocks from the Naples Beach Section (Santa Barbara- Ventura Basin). In The Monterey Formation: From Rocks to Molecules; Columbia University Press: New York, 2001; pp 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert W. K.; Moldowan J. M. Applications of steranes, terpanes and monoaromatics to the maturation, migration and source of crude oils. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1978, 42, 77–95. 10.1016/0016-7037(78)90219-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y.; Liao F.; Yao L.; Gao J.; Zhang D. Stable hydrogen isotopic characteristics of nature gas from the Xujiahe Formation in the central Sichuan Basin and its implications for water salinization. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2019, 30, 880–896. [Google Scholar]; (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Jincai T.; Wang X.; Chen J. Distribution and evolution of tricyclic terpanes in lacustrine carbonates. Org. Geochem. 1999, 30, 1429–1435. 10.1016/S0146-6380(99)00117-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ekweozor C.; Strausz O.. Tricyclic Terpanes in the Athabasca Oil Sands: Their Geochemistry; Bjorøy M., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 1983; pp 746–766. [Google Scholar]

- Chen A.; Zhao J.; Qi J.; Shao M. Distribution of tricyclic terpane and sterane with application to oil-source correlation in southern Turgay Basin. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2013, 34, 602–606. [Google Scholar]; (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Aquino Neto F. R.; Trendel J. M.; Restlé A.; Connan J.; Albrecht P.. Occurrence and Formation of Tricyclic Terpanes in Sediments and Petroleums; Bjorøy M.; Albrecht P.; Cornford C.; de Groot K.; Eglinton G.; Galimov E.; Leythaeuser D.; Pelet R.; Rullkötter J.; Speers G., Eds.; Wiley: New York, 1983; pp 659–667. [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Zhang S.; Gu Y.; Su J. Impacts of source input and secondary alteration on the extended tricyclic terpane ratio: a case study from Palaeozoic sourced oils and condensates in the Tarim Basin, NW China. Org. Geochem. 2017, 112, 158–169. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H.; Li M.; Yang Z.; Zhu Z. The distribution patterns and geochemical implication of C19-C23 tricyclic terpanes in source rocks and crude oils occurred in various depositional environment. Geochimica 2019, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]; (in Chinese with English abstract).