Abstract

Objectives

Reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) is considered the most sensitive method for the detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2). However, this method is relatively resource- and time-consuming. This study was performed to compare SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antigen (N-Ag) testing using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection.

Methods

Parallel SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR and quantitative N-Ag ELISA analysis was executed on nasopharyngeal specimens obtained during SARS-CoV-2 screening in a cohort of pre-hospitalization patients.

Results

In total, 277 specimens were examined, including 182 (65.7%) RT-PCR-positive specimens, which demonstrated a median cycle threshold (Ct) value of 27 (interquartile range (IQR) 23–35). The SARS-CoV-2 N-Ag was detected in 164 of the 182 RT-PCR-positive specimens (overall sensitivity 90.1%). Among the 95 RT-PCR-negative specimens, 72 were N-Ag-negative (specificity 75.8%). SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR and N-Ag ELISA results demonstrated a strong agreement (Cramer’s V = 0.668; P < 0.001). N-Ag concentrations spanned from 5.4 to 296 000 pg/ml (median 901 pg/ml, IQR 43–1407 pg/ml) and were inversely correlated with Ct values (Spearman’s r = −0.720; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 N-Ag ELISA results were in close agreement with RT-PCR results, and N-Ag concentrations were proportional to viral loads. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 quantitative antigen testing could be an additional diagnostic instrument for SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, RNA, Antigen, Concentration, Concordance

Introduction

The ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) poses serious challenges for healthcare. Unprecedented demands on molecular testing have revealed a number of practical limitations of the PCR-based COVID-19 diagnostics. In this situation, additional and less demanding laboratory tools for SARS-CoV-2 detection, such as testing for viral antigens, merit consideration. A series of studies have reported the performance of numerous qualitative immunochromatographic rapid diagnostic tests (Young et al., 2020, Chaimayo et al., 2020, Lanser et al., 2020), as well as several variants of automated quantitative assays (Hirotsu et al., 2021, Pollock et al., 2021). In the present study, quantitative SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antigen (N-Ag) testing was performed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in parallel with SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in a series of nasopharyngeal specimens obtained during COVID-19 screening.

Materials and methods

Nasopharyngeal specimens (N = 277) were obtained from individuals during routine screening for COVID-19 before planned hospitalization using the Σ-Transwab system (MWE, UK) in October–November 2020. RT-PCR was performed using the SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV Multiplex Real-Time PCR Detection Kit (DNA-Technology LLC, Russia) (SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV instruction manual, 2021) targeting a conserved E-gene site common to the group of SARS-CoV-like coronaviruses (including SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2) and SARS-CoV-2-specific E-gene and N-gene sites; the manufacturer’s protocol was followed (SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV instruction manual). An RT-PCR result was considered positive if all three target genes demonstrated a cycle threshold (Ct) value of ≤38. Ct values for the common E-gene probe were used for calculations. The residual specimens were frozen at −80 °C until determination of the N-Ag concentration using the CoviNAg ELISA kit (XEMA, Russia) (CoviNAg instruction manual, 2021). Specimens with a concentration of <5 pg/ml were considered negative. A subset of specimens demonstrating an N-Ag concentration >1000 pg/ml were diluted 10- to 1000-fold to obtain a true concentration value.

Results

Among the 277 specimens examined, 182 (65.7%) were RT-PCR-positive (Table 1 ), with a median Ct value of 27 (interquartile range (IQR) 23–35). The SARS-CoV-2 N-Ag was detected in 164 of the 182 RT-PCR-positive specimens, demonstrating an overall sensitivity of 90.1%. Among the 95 RT-PCR-negative specimens, 72 were N-Ag-negative (specificity 75.8%). The Cramer’s V test demonstrated a strong agreement between SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR and N-Ag ELISA results (V = 0.668; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Parallel detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and nucleocapsid antigen in nasopharyngeal specimens.

| N-Ag SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (by Ct range) |

Negative | ||||||

| Any Ct | ≤20 | 21–25 | 26–30 | 31–35 | >35 | ||

| Total (N = 277) | 182 | 26 | 62 | 42 | 34 | 18 | 95 |

| Positive, n | 164 | 26 | 61 | 39 | 29 | 9 | 23 |

| Negative, n | 18 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 72 |

| Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | 90.1 (85.1–93.8) | 100 | 98.4 (92.7–99.8) | 92.9 (82.1–97.9) | 85.3 (70.7–94.2) | 50 (28.4–71.6) | NA |

| Specificity, % (95% CI) | NA | 75.8 (66.5–83.5) | |||||

Note: The sensitivity and specificity of the N-Ag test were calculated considering RT-PCR results as the reference. CI, confidence interval; Ct, cycle threshold; NA, not applicable; N-Ag, nucleocapsid antigen; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

At Ct ≤20, there were no discordant results between the SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR and N-Ag test (100% sensitivity) (Table 1). Furthermore, >90% of specimens demonstrating a Ct value in the range of 21–30 were also positive in the N-Ag ELISA assay. Higher Ct values resulted in a decreased sensitivity rate of 85.3% and 50% for the Ct range of 31–35 and >35, respectively.

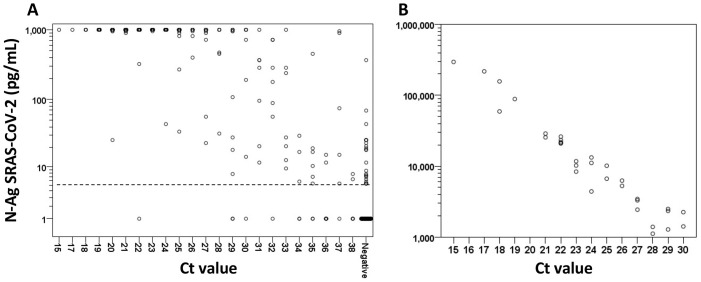

In 82 (50%) RT-PCR-positive/N-Ag-positive specimens, the N-Ag concentration was above the upper detection limit of 1000 pg/ml of the ELISA assay (Figure 1 A); therefore a repeated N-Ag measurement was performed in a subset of specimens from this cohort (n = 32) after dilution (Figure 1B). Thus, the true N-Ag concentration was detected in 114 RT-PCR-positive specimens, which spanned from 5.4 to 296 000 pg/ml (median 901 pg/ml, IQR 43–1407 pg/ml). N-Ag concentrations correlated inversely with Ct values (Spearman’s r = −0.720; P < 0.001) suggesting a tight correlation with the viral load.

Figure 1.

Nucleocapsid antigen (N-Ag) SARS-CoV-2 concentration distribution in relation to SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values. (A) Nasopharyngeal specimens (N = 277) were subjected to SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR (Ct value of 38 for defining positivity) and N-Ag ELISA (assay range 5–1000 pg/ml) in parallel. All specimens with a concentration of >1000 pg/ml and <5 pg/ml are depicted on the scattergram at 1000 pg/ml and 1 pg/ml, respectively. The dashed line at 5 pg/ml indicates the N-Ag positivity threshold. (B) To obtain the true N-Ag concentration, the measurement was repeated after a 10- to 1000-fold dilution in a subset of specimens with an N-Ag concentration >1000 pg/ml (n = 32).

Among 18 RT-PCR-negative specimens in which the N-Ag was detected, N-Ag concentrations varied between 5.3 and 364 pg/ml (median 11 pg/ml, IQR 6–25 pg/ml).

Discussion

This study demonstrated a strong agreement between SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR and N-Ag testing results. The highest rate of concordant results was observed at Ct ≤35, indicating that the N-Ag test was highly likely to be positive in individuals with a significant viral load, who are considered as key vectors for virus spreading (Bullard et al., 2020). In specimens with Ct >35, much more discordant results with a negative N-Ag test were observed.

Several studies have demonstrated a direct correlation between viral load and SARS-CoV-2 culture positivity. According to Singanayagam et al. (2020), the probability of culturing virus is as low as 8.3% in samples with a Ct >35, while Bullard et al. (2020) did not observe SARS-CoV-2 infectivity at Ct ≥24. Importantly, compared to RT-PCR, antigen testing could be a better predictor of the presence of cultivable SARS-CoV-2 (Pekosz et al., 2021). Ct values are widely used as a semiquantitative indicator of the SARS-CoV-2 viral load (Singanayagam et al., 2020); thus, the close relationship between SARS-CoV-2 antigen concentrations and RT-PCR Ct values, as observed in the present study and by other authors (Pollock et al., 2021), may explain this finding. The epidemiological significance of specimens demonstrating high RT-PCR Ct values but no detectable SARS-CoV-2 antigen is not clear.

N-Ag ELISA concentrations in RT-PCR-positive specimens were distributed over a wide range (at least five orders of magnitude), which is similar to the findings of Hirotsu et al. (2021). The quantitative SARS-CoV-2 antigen measurement may be instrumental for monitoring viral clearance, demonstrating a gradual decline over a broad concentration range in contrast to abrupt fluctuations in RT-PCR positivity (Hirotsu et al., 2021).

A number of RT-PCR-negative specimens in which N-Ag was detected were observed, albeit at low concentrations. Such results were unlikely to be related to the ELISA assay specificity, because it had been tested over a panel of coronavirus strains and no cross-reactivity was detected (CoviNAg instruction manual). The RT-PCR method as a relatively ‘fastidious’ technique could be more demanding in terms of specimen quality and RNA stability compared to antigen testing. Clinical as well as SARS-CoV-2 serology data could be helpful in resolving this situation, but this information was not available for the study.

In conclusion, quantitative SARS-CoV-2 N-Ag ELISA demonstrating a comparable sensitivity with RT-PCR at the epidemiologically important Ct values may be a useful additional instrument for detecting SARS-CoV-2.

Funding

This study had no special funding.

Ethics statement

According to national rules and regulations, ethical approval was not required.

Conflict of interest

Y.L. is an employee of XEMA Company. All other authors have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The RNA extraction and RT-PCR were performed using the equipment of the Center for Precision Genome Editing and Genetic Technologies for Biomedicine, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University, Moscow, Russia (grant 075-15-2019-1789).

References

- Bullard J., Dust K., Funk D., Strong J.E., Alexander D., Garnett L. Predicting infectious SARS-CoV-2 from diagnostic samples. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;(May) doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaimayo C., Kaewnaphan B., Tanlieng N., Athipanyasilp N., Sirijatuphat R., Chayakulkeeree M. Rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection assay in comparison with real-time RT-PCR assay for laboratory diagnosis of COVID-19 in Thailand. Virol J. 2020;17(1):177. doi: 10.1186/s12985-020-01452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CoviNAg instruction manual. https://xema-medica.com/eng/sets/ifu/Archive/. (kit K053NIE v2007). [Assessed 20 May 2021].

- Hirotsu Y., Maejima M., Shibusawa M., Amemiya K., Nagakubo Y., Hosaka K. Prospective study of 1308 nasopharyngeal swabs from 1033 patients using the LUMIPULSE SARS-CoV-2 antigen test: comparison with RT-qPCR. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;105:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanser L., Bellmann-Weiler R., Öttl K.W., Huber L., Griesmacher A., Theurl I. Evaluating the clinical utility and sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing in relation to RT-PCR Ct values. Infection. 2020;13:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01542-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekosz A., Parvu V., Li M., Andrews J.C., Manabe Y.C., Kodsi S. Antigen-based testing but not real-time polymerase chain reaction correlates with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viral culture. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;(January) doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock N.R., Savage T.J., Wardell H., Lee R.A., Mathew A., Stengelin M. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antigen and RNA concentrations in nasopharyngeal samples from children and adults using an ultrasensitive and quantitative antigen assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;(January) doi: 10.1128/JCM.03077-20. JCM.03077-20. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV instruction manual. https://dna-technology.com/equipmentpr/pcr-kits-respiratory-infections/sars-cov-2sars-cov-multiplex. [Assessed 27 February 2021].

- Singanayagam A., Patel M., Charlett A., Lopez Bernal J., Saliba V., Ellis J. Duration of infectiousness and correlation with RT-PCR cycle threshold values in cases of COVID-19, England, January to May 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(32) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.32.2001483. pii=2001483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S., Taylor S.N., Cammarata C.L., Varnado K.G., Roger-Dalbert C., Montano A. Clinical evaluation of BD Veritor SARS-CoV-2 point-of-care test performance compared to PCR-based testing and versus the Sofia 2 SARS antigen point-of-care test. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;59(1):e02338–20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02338-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]