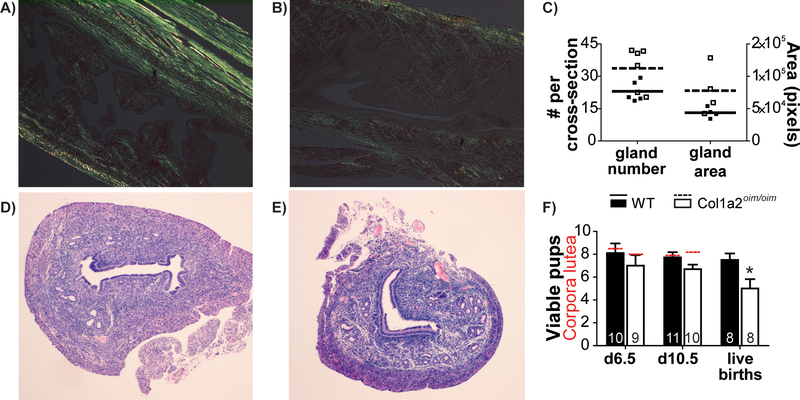

Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI), or brittle bone disease, is most often caused by mutations in genes encoding type I collagen or the proteins that process it. The osteogenesis imperfecta mouse (Col1a2oim/oim) is a well-established model of moderately severe OI. Like OI patients, the Col1a2oim/oim mouse suffers from osteopenia, fractures, bone deformities and small stature (Yao et al., 2013). While flushing embryos from Col1a2oim/oim uteri, we observed differences in extensibility of the uterine wall, and hypothesized that Col1a2oim/oim may have impaired uterine function. To test this, first longitudinal uterine sections were stained with picrosirius red and photographed under polarized light to visualize the collagen fiber network. Whereas collagen bundles are abundant in the myometrium and apparent in the endometrium of control (Col1a2+/+) uteri (Figure 1A), birefringence is much fainter in Col1a2oim/oim uteri (Figure 1B), consistent with previous observations of diminished collagen in the myometrium of a patient with OI (Christodoulou, Freemont, McVey, & Vause, 2007). Uterine cross-sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin suggest an expansion of uterine glands. This observation was somewhat supported by ImageJ analysis of the number (p=0.055) and total area (p=0.12) of uterine glands in three cross-sections each from 4–6 control and Col1a2oim/oim dams, but no significant difference was found (Figure 1C–E). Next, control and Col1a2oim/oim dams were mated and either sacrificed for examination at gestation day 6.5 (just after implantation) or day 10.5 (mid-pregnancy), or allowed to continue to term, with pups assessed at postnatal day 1 and 2. The number of viable pups was significantly reduced in Col1a2oim/oim dams, independent of stage of gestation, though in pairwise comparisons the loss was only significant at term (Figure 1F). There was no difference in the number of corpora lutea present in the ovaries at days 6.5 or 10.5, consistent with similar numbers of ovulated oocytes (Figure 1F). These data suggest that while ovulation occurs normally, there is a gradual loss of viable pups over the course of gestation. However, there was no difference in mean weight amongst pups that were born to control (1.3 ± 0.03g) and Col1a2oim/oim (1.2 ± 0.06g) dams and gestation length was normal. When dams were mated a second time, control dams (8.0 ± 1.0 pups) again had significantly more pups than Col1a2oim/oim dams (5.8 ± 0.9 pups), with no differences in pup weights. To rule out any effect of Col1a2oim/+ pup genotype on viability, we mated control females to Col1a2oim/+ sires, and found the expected proportion of pups (17/29) were Col1a2oim/+. Thus, the reduction in viable pups in Col1a2oim/oim dams is due to the uterine environment, not the embryo genotype. Overall, the Col1a2oim/oim mouse data suggest that OI impairs uterine function in pregnancy in a way that affects a small but significant number of fetuses. Similarly, in a retrospective cohort study of 295 births, most women with OI had healthy pregnancies, but there were significantly elevated rates of antepartum hemorrhage, placental abruption and uterine rupture (Ruiter-Ligeti, Czuzoj-Shulman, Spence, Tulandi, & Abenhaim, 2016). Data from the mouse model add to the concern for these rare, but dangerous, pregnancy outcomes in OI.

Figure 1.

Collagen bundles visible in (A) Control (Col1a2+/+) and (B) Col1a2oim/oim (OIM) longitudinal uterine sections as birefringence (yellow-green) under polarized light. (C) Uterine gland numbers and total area averaged in three randomly selected cross-sections per mouse (p>0.05). Representative cross-sections of (D) control and (E) Col1a2oim/oim uteri. The number of viable pups or fetuses (columns) was significantly reduced in Col1a2oim/oim dams, independent of gestational age (ANOVA, p=0.009) *p<0.05 (Student’s t-test). The number of corpora lutea (red hashed lines) were not different between maternal genotypes. The number of animals examined is indicated at base of each column. Error bars represent SEM.

Acknowledgements:

Authors wish to thank Lixing Reneker for assistance with polarized light microscopy and Kathleen Pennington for assistance with uterine gland histology.

Funding Source- March of Dimes, Leda J. Sears Trust Foundation

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- Christodoulou S, Freemont AJ, McVey R, & Vause S (2007). Prospective comparative case study of uterine collagen in a woman with osteogenesis imperfecta type 1 who had previously ruptured her uterus. J Obstet Gynaecol, 27(7), 738–739. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17999312. doi: 10.1080/01443610701667288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiter-Ligeti J, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Spence AR, Tulandi T, & Abenhaim HA (2016). Pregnancy outcomes in women with osteogenesis imperfecta: a retrospective cohort study. J Perinatol, 36(10), 828–831. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27442154. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Carleton SM, Kettle AD, Melander J, Phillips CL, & Wang Y (2013). Gender-dependence of bone structure and properties in adult osteogenesis imperfecta murine model. Ann Biomed Eng, 41(6), 1139–1149. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23536112. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0793-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]