Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the subtype imaging features of basal ganglia germ cell tumors (GCTs).

Methods:

Clinical and imaging data of 33 basal ganglia GCTs were retrospectively analyzed, including 17 germinomas and 16 mixed germ cell tumors (MGCTs).

Results:

The cyst/mass ratio of germinomas (0.53 ± 0.32) was higher than that of MGCTs (0.28 ± 0.19, p = 0.030). CT density of the solid part of germinomas (41.47 ± 5.22 Hu) was significantly higher than that of MGCTs (33.64 ± 3.75 Hu, p < 0.001), while apparent diffusion coefficients (ADC, ×10-3 mm2/s) value of the solid part was significantly lower in geminomas (0.86 ± 0.27 ×10-3 mm2/s) than in MGCTs (1.42 ± 0.39 ×10-3 mm2/s, p < 0.001). MGCTs were more common with intratumoral hemorrhage (68.75% vs 11.76%, p = 0.01), T1 hyperintense foci (68.75% vs 5.88%, p < 0.001) and calcification (64.29% vs 20.00%, p = 0.025) than germinomas. There was no significant difference in internal capsule involvement between the two subtypes (p = 0.303), but Wallerian degeneration was more common in germinomas than in MGCTs (70.59% vs 25.00%, p = 0.015).

Conclusion:

The subtypes of GCT have different imaging features. Tumoral cystic-solidity, heterogeneity, ADC value, CT density, and Wallerian degeneration are helpful to differentiate germinomas and MGCTs in basal ganglia.

Advances in knowledge:

The subtypes of GCT have different histological characteristics, leading to various imaging findings. The imaging features of GCT subtypes in basal ganglia may aid clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Introduction

Intracranial germ cell tumors (GCTs) are uncommon and mostly observed in children and young adults, accounting for 0.5–2.0% of all primary intracranial tumors and 9.5% of all pediatric brain tumors. 1 Most of them are located in the pineal and suprasellar regions. Only about 5–10% of GCTs occur in basal ganglia with insidious onsets and atypical clinical symptoms, which can easily delay clinical diagnosis. 2 The imaging findings can provide more information for clinical diagnosis and management. For a long time, basal ganglia GCTs were often studied as a whole, because of the low incidence and limited imaging data of subtypes. Intracranial GCTs can be classified into germinomas and non-germinomatous germ cell tumors (NGGCTs). 3 Germinomas are the most common, accounting for 65–70% of GCTs. While more than 50% of NGGCTs were mixed germ cell tumors (MGCTs). 4 MGCTs comprise at least two histological components, and the components of germinoma, teratoma, and yolk sac tumor are the most common. 5,6 Indeed, GCT subtypes have some different histological characteristics, resulting in various imaging findings and therapeutic strategies. However, the imaging features of GCT subtypes have not been sufficiently investigated, especially for those in basal ganglia. Therefore, we retrospectively analyzed the subtype imaging features of basal ganglia GCTs to aid accurate clinical diagnosis and individualized treatment.

Methods and materials

Clinical data

From May 2014 to November 2019, 33 patients with basal ganglia GCTs verified by histopathology were collected, including 21 patients with surgery and 12 patients with stereotactic biopsy. The inclusion criteria: definite pathological results; unilateral basal ganglia lesion; complete clinical and imaging data. The exclusion criteria: bilateral basal ganglia lesions; combined with the sellar or pineal lesion; intracranial metastatic lesions; previous history of treatment. Specific tumor markers were available in 23 patients before the clinical management, such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG). According to the criteria of our hospital (Beijing Tiantan Hospital), AFP >7 ng ml−1 and/or β-hCG > 5 mIU/mL were positive in this study. The clinical data such as gender, age at onset, course of disease, and tumor marker levels were recorded and analyzed.

Imaging analysis

Before treatment, all 33 patients underwent brain MRI (3.0T Philips scanners, Eindhoven, Netherlands), and 29 patients underwent non-contrast CT (16-slice GE scanners, Milwaukee). MR scanning sequences included T 1 weighted imaging (T 1WI), T 2 weighted imaging (T 2WI), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, diffusion-weighted imaging. Post-contrast T 1WI after gadolinium injection (0.2 ml/kg) was obtained. Imaging indicators included: tumor size (volume), mass effect (subtle, obvious), peritumoral edema (subtle, obvious), tumoral cystic-solidity (cyst/mass ratio), intratumoral hemorrhage (present, absent), T1 hyperintense foci (present, absent), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC, ×10-3 mm2/s) value, inhomogeneous enhancement (subtle, obvious), internal capsule involvement (complete, partial) and Wallerian degeneration (present, absent). Meanwhile, tumor density (Hounsfield unit, Hu) and intratumoral calcification (present, absent) were evaluated on non-contrast CT. Peritumor edema was evaluated by edema index (EI, EI < 1.5, the subtle edema; EI > 1.5, the obvious edema). 7 The cystic-solidity of the tumor (cyst/mass ratio) was relative and based on the size ratio of the cystic part to the whole tumor (cyst volume/tumor volume). 8 For multiple separate cysts, we measured their volumes separately and sum them up to get the total volume of cysts. The volume measurement was performed on Neusoft workstation (V5.125). Intratumoral hemorrhage was defined as a localized hyper-hypointense interface or hypointense ring around the lesion on T 2WI. On T 2WI, ill-defined hyperintensity in the internal capsule was considered as the internal capsule involvement. Wallerian degeneration was defined as ipsilateral atrophy of the cerebral peduncle, basal ganglia, or cerebral hemisphere, compared with the contralateral side. CT density and ADC value of lesions were targeted at the solid part of the tumor for assessment. Avoiding intratumoral calcification, hemorrhage, and cystic change, the CT density and ADC value of each lesion were determined by a mean value of three different regions of interest (ROI, 20–100 mm2) on Neusoft workstation (V5.125). All imaging data were reviewed separately by three experienced neuroradiologists, who were blind to histological results. The disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS v. 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were performed to characterize clinical and imaging features. Independent t-test (two-tailed) or Mann–Whitney U test was used for statistical comparison of continuous variables between the two groups. Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used to test the difference of dichotomous variables. All data are presented as median (range), mean ± SD, or number (percentage). p < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical findings of both subtypes

33 basal ganglia GCTs included 31 males and 2 females, with a mean age of 11.3 ± 4.2 years and a median course of 13.5 months (range 2–44 months). Clinical manifestations included hemiparesis, hemifacial nerve palsy, dyskinesia, hemianopsia, dizziness, and cognitive disorders. Histologically, 33 GCTs were classified into germinomas (17 cases, 15 males and 2 females) and MGCTs (16 cases, 16 males). Both subtypes showed male tendency (p = 0.485). The onset age of germinomas (15. 3 ± 3.3 years) was significantly older than that of MGCTs (10.2 ± 4.6 years, p = 0.037). There was no significant difference in median course of disease between the two subtypes (p = 0.186). 16 MGCTs contained 2–4 different tumor components: 14 cases (87.5%) contained germinoma, 11 cases (68.75%) contained teratoma (immature teratoma in 6 cases, mature teratoma in 5 cases), 7 cases (43.75%) contained yolk sac tumor, 4 cases (25%) contained embryonic carcinoma and 2 cases (12.5%) contained choriocarcinoma. There was no significant difference in tumor marker test between the two subtypes (10 germinomas and 13 MGCTs, p = 0.100). See Table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Clinical and imaging features of subtypes

| Geminomas (n = 17) | MGCTs (n = 16) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical findings | |||

| Gender (M : F) | 15:2 | 16:0 | 0.485 |

| Age at onset (years) | 15.3 ± 3.3 | 10.2 ± 4.6 | 0.037 a |

| Course of disease (months) | 10.6 (3–26) | 8.8 (2–44) | 0.186 |

| Tumor marker tests (n = 23, positive : negative) |

3:7 | 9:4 | 0.100 |

| Imaging findings | |||

| Size (cm3) | 54.27 ± 17.95 | 75.23 ± 27.23 | 0.487 |

| Mass effect (n, subtle:obvious) |

13:4 | 8:8 | 0.157 |

| Peritumoral edema (n, subtle:obvious) |

14:3 | 10:6 | 0.259 |

| Tumor cystic-solidity (cyst/mass ratio) |

0.53 ± 0.32 | 0.28 ± 0.19 | 0.030 a |

| ADC value (×10-3 mm2/s) | 0.86 ± 0.27 | 1.42 ± 0.39 | <0.001 a |

| Inhomogeneous enhancement (n, subtle:obvious) |

4:13 | 7:9 | 0.282 |

| Intratumoral hemorrhage (n, present:absent) |

2:15 | 11:5 | 0.01 a |

| T1 hyperintense foci (n, present:absent) |

1:16 | 11:5 | <0.001 a |

| Intratumoral calcification (n = 29, present:absent) |

3:12 | 9:5 | 0.025 a |

| CT density (Hu) | 41.47 ± 5.22 | 33.64 ± 3.75 | <0.001 a |

| Internal capsule involvement (n, partly:completely) |

7:10 | 10:6 | 0.303 |

| Wallerian degeneration (n, subtle:obvious) |

5:12 | 12:4 | 0.015 a |

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; Hu, Hounsfield unit; MGCT, mixed germ cell tumor; SD, standard deviation.

Values are given as n, mean ± SD, or median (range).

significance values.

Imaging findings of both subtypes

There was no difference in size, mass effect and peritumoral edema between germiomas and MGCTs (p = 0.487, p = 0.157 and p = 0.259, respectively). The cyst/mass ratio of germinomas (0.53 ± 0.32) was higher than that of MGCTs (0.28 ± 0.19, p = 0.030). CT density of the solid part of germinomas (41.47 ± 5.22 Hu) was significantly higher than that of MGCTs (33.64 ± 3.75 Hu, p < 0.001), while ADC value of the solid part was significantly lower in geminomas (0.86 ± 0.27 ×10-3 mm2/s) than in MGCTs (1.42 ± 0.39 ×10-3 mm2/s, p < 0.001). Compared with germinomas, MGCTs were more common with intratumoral hemorrhage (68.75% vs 11.76%, p = 0.01), T1 hyperintense foci (68.75% vs 5.88%, p < 0.001) and calcification (64.29% vs 20.00%, p = 0.025). On post-contrast T 1WI, inhomogeneous enhancement was obvious in both subtypes (p = 0.282). There was no significant difference in internal capsule involvement between the two subtypes (p = 0.303), but germinomas were more prone to Wallerian degeneration (70.59% vs 25.00%, p = 0.015). See Figures 1–3 Figures 1–4, Table 1 for details.

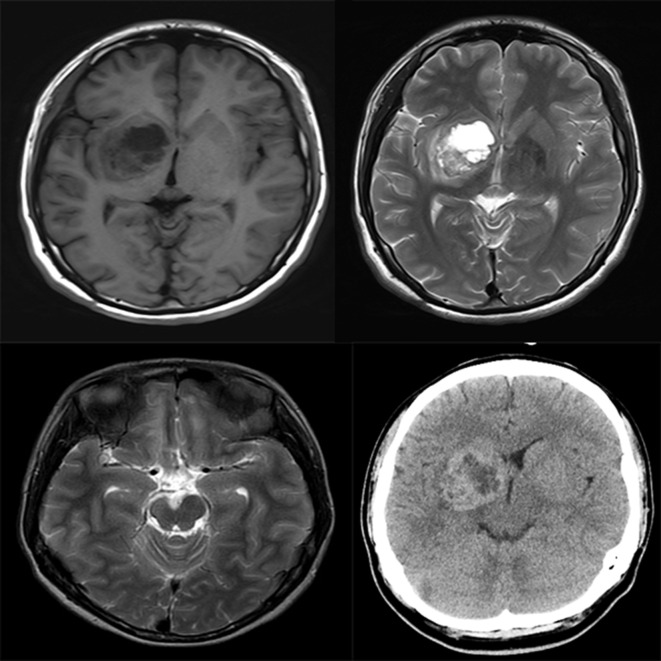

Figure 1.

Basal ganglia germinoma. Axial MRI scans reveal a lesion (cyst/mass ratio = 0.71) in the right basal ganglia, showing iso-hypointensity on T 1WI (Top left) and iso-hyperintensity on T 2WI (Top right). The posterior limb of ipsilateral internal capsule is involved, showing hyperintensity on T 2WI (Top right). The atrophy of ipsilateral cerebral peduncle is visible on T 2WI (Lower left). The lesion shows mixed density on axial CT, and CT density of the solid part is 40 Hu (Lower right). Hu Hounsfield unit; T 1WI, T 1 weighted imaging; T 2WI, T 2 weighted imaging.

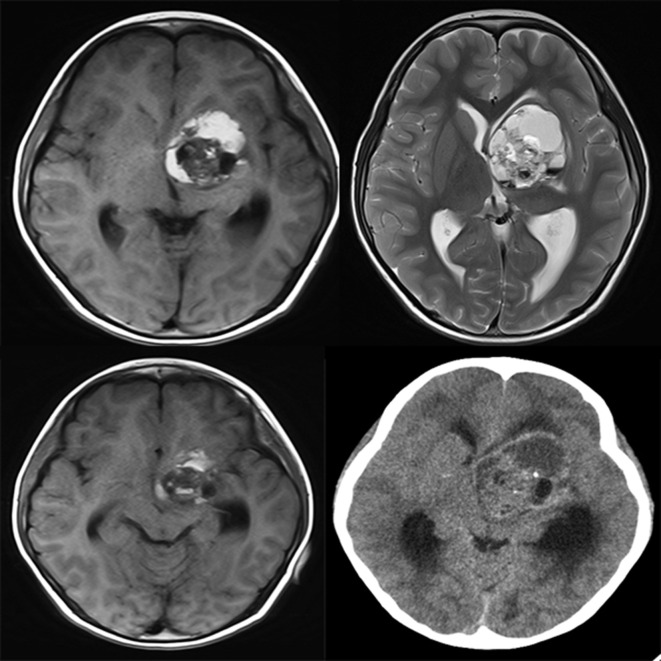

Figure 2.

Basal ganglia MGCT. Axial MRI scans reveal a lesion (cyst/mass ratio = 0.41) in the left basal ganglia, showing iso-hyperintensity on T 1WI (Top left) and T 2WI (Top right). On T 2WI, multiple hypo-hyperintense interfaces are localized, and the left internal capsule is involved, showing hyperintensity in the posterior limb (Top right). But the ipsilateral cerebral peduncle is normal (Lower left). CT density of the solid part is 31 Hu, and with stippled calcification (Lower right). Ventricular compression and dilation can be seen. Hu Hounsfield unit; T 1WI, T 1 weighted imaging; T 2WI, T 2 weighted imaging.

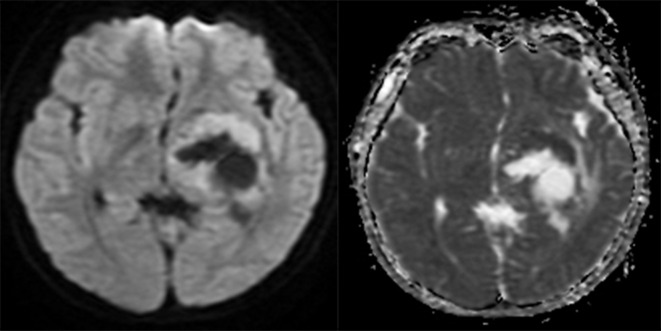

Figure 3.

Basal ganglia germinoma. Axial MRI scans reveal a cystic lesion in the left basal ganglia. The solid part of the lesion shows hyperintensity on DWI (Left) and hypointensity on ADC map (Right). The mean ADC value is 0.71×10-3 mm2/s. ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging.

Figure 4.

Basal ganglia MGCT. Axial MRI scans reveal a solid lesion in the right basal ganglia. The solid part of the lesion shows iso-hypointensity on DWI (Left) and hyperintensity on ADC map (Right). The mean ADC value is 1.69 ×10-3 mm2/s. ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; MGCT, mixed germ cell tumor.

Discussion

Intracranial ectopic GCTs are most common in basal ganglia, affecting males under 20 years old. 9 Our patients in this study showed a similar demographic distribution. Development of the third ventricle might divert germ cells from the midline, leading to the emergence of basal ganglia GCTs. 10 The onset age of germinomas was older than that of MGCTs, which might be attributable to the occult onset of germinomas or abnormal secretory functions of MGCTs. The clinical manifestation of basal ganglia GCTs is associated with the location and composition of tumors. 11 On the one hand, basal ganglia invasion can cause hemiparesis, oculomotor palsy, dystonia, and anesthesia. On the other hand, the levels of tumor markers depend on tumoral composition, resulting in some endocrine abnormalities. However, tumor marker tests did not play a key role in this study. Most germinomas were non-secretory, with normal AFP and β-hCG levels. While the β-hCG level is increased in some germinomas with syncytiotrophoblast component, explaining the positive tumor markers in germinomas. 12 Due to the complexity of tumor components, the levels of AFP and β-hCG in the MGCTs group fluctuated greatly. Especially, some MGCTs were also non-secretory, with normal tumor marker levels. All of these could confuse the diagnosis of GCT subtypes.

There was no difference in tumor size, mass effect, and peritumoral edema between the two subtypes. In other words, similar tumor size leads to similar mass effects and peritumoral edema. Some studies reported that peritumoral edema could suggest immature or malignant tumor components. 4,13 But our study did not show this tendency. With the growth of a tumor, the compressed basal ganglia can also cause venous reflux edema. 14

Cystic changes may be associated with tumor enlargement, suggesting growth potential. 2,14 Compared with NGGCTs, germinomas have stronger growth potential, showing more cystic changes and inhomogeneous enhancement. 15 However, there was no significant relationship between enhancement patterns and subtypes on post-contrast T 1WI. In addition to cystic changes, different histological components also lead to inhomogeneous enhancement. 16 Germinoma, yolk sac tumor, and immature teratoma were the most common components with obvious enhancement in MGCTs, which could be confused with germinomas. 17 Chih-Chun Wu et al and Ryuji Awa et al reported that in the pineal region, NGGCTs were larger than germinomas and more common with cystic changes and inhomogeneous enhancement. 7,18 Our results are inconsistent with theirs. Maybe, the narrow space of pineal region can bring about different imaging features.

In this study, MGCTs were more heterogeneous, with intratumoral hemorrhage, T1 hyperintense foci, and calcification. Neoplastic transformation at different stages leads to mixed components and complex imaging findings. 5 Previous studies showed that with the enlargement of intracranial GCTs, intratumoral hemorrhage was more common. 2 However, intratumoral hemorrhage may be related not only to tumor growth but also to tumor components. The components of choriocarcinoma and yolk sac tumor are more likely to cause intratumoral hemorrhage. 19,20 T1 hyperintense foci may present subacute hemorrhage, high-protein materials, fat, or calcification. Calcification and fat are more common in teratoma components. 21 While the composition of germinoma is relatively pure, and the solid part of the tumor is more homogeneous. This difference may be related to histogenesis. It is currently believed that only pure germinomas arise from primordial germ cells, while other GCTs may originate from misfolded embryonic cells. 15,22 Moreover, CT hyperdensity and lower ADC value of the solid part were more common in germinomas. Relative to MGCTs, germinomas have denser cellularity, higher nucleocytoplasmic ratio, and lower water content. 23

Wallerian degeneration was common in basal ganglia GCTs, resulting from the infiltration of nerve fiber tracts. 24 With the enlargement of a lesion, the mass effect can cover up the atrophy of basal ganglia or cerebral hemisphere, while the atrophy of ipsilateral cerebral peduncle still exists. Therefore, the assessment of Wallerian degeneration in this study depended more on the ipsilateral cerebral peduncle. Wallerian degeneration has been emphasized as a reliable sign of basal ganglia GCTs. 25 However, the role of different subtypes remains unclear. In the current study, basal ganglia germinomas were more likely to cause Wallerian degeneration, although there was no significant difference in internal capsule involvement between the two subtypes. To some extent, the slow and invasive growth of germinomas may be more reasonable for Wallerian degeneration. 2,24,26 Histological studies confirmed that germinomas had strong proliferation and low collagen development, leading to infiltrative growth. 7,27 Because MGCTs contain more non-germinomatous components, their invasiveness is lower.

Intracranial germ cell tumors should be treated according to different histological subtypes. Germinoma is very sensitive to radiotherapy. Therefore, radiotherapy is an effective treatment, while surgery is not recommended. 28 Whole-brain or whole ventricular radiotherapy plus tumor boost can reduce local or spinal relapse, while focal radiotherapy alone may significantly increase the recurrence rate. 29 Due to the low incidence rate, there is no specific therapeutic regimen for MGCTs. However, the treatment of MGCTs should focus on the most malignant components. 30 In general, the responsiveness of MGCTs to radiotherapy is low, and the combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy can significantly improve the prognosis. 31 Surgery is an alternative treatment for MGCTs, especially when the tumors are not sensitive to chemoradiotherapy. 32

Of cause, this study has some limitations. Considering the rarity of intracranial ectopic GCTs, this study did not include more other subtypes. Due to the lack of fat-suppressed sequence and susceptibility-weighted imaging in this retrospective study, T1 hyperintense foci could not be interpreted accurately. However, this did not hinder the determination of tumor heterogeneity. Stereoscopic biopsies might induce inadequate sampling and misrepresentation, but multipoint sampling could reduce errors. Because basal ganglia GCTs were not considered in pre-operative diagnosis, some patients were not tested for tumor markers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the subtypes of GCT in basal ganglia have different imaging features. Although these imaging features are not pathognomonic, they can provide useful information for clinical management. Tumoral cystic-solidity, heterogeneity, ADC value, CT density, and Wallerian degeneration could be helpful to differentiate the two subtypes. Detailed analysis of GCT subtypes in basal ganglia requires further studies with larger cohorts.

Contributor Information

Wei Li, Email: liweiqd830127@163.com.

Xin Kong, Email: 874807413@qq.com.

Jun Ma, Email: 15106566170@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Packer RJ, Cohen BH, Cooney K, Coney K. Intracranial germ cell tumors. Oncologist 2000; 5: 312–20. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2000-0312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Echevarría ME, Fangusaro J, Goldman S. Pediatric central nervous system germ cell tumors: a review. Oncologist 2008; 13: 690–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 131: 803–20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borja MJ, Plaza MJ, Altman N, Saigal G. Conventional and advanced MRI features of pediatric intracranial tumors: supratentorial tumors. American Journal of Roentgenology 2013; 200: W483–503. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liang L, Korogi Y, Sugahara T, Ikushima I, Shigematsu Y, Okuda T, et al. MRI of intracranial germ-cell tumours. Neuroradiology 2002; 44: 382–8. doi: 10.1007/s00234-001-0752-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sato K, Takeuchi H, Kubota T. Pathology of intracranial germ cell tumors. Prog Neurol Surg 2009; 23: 59–75. doi: 10.1159/000210053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim B-W, Kim M-S, Kim S-W, Chang C-H, Kim O-L. Peritumoral brain edema in meningiomas : correlation of radiologic and pathologic features. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2011; 49: 26–30. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2011.49.1.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee SM, Kim I-O, Choi YH, Cheon J-E, Kim WS, Cho H-H, et al. Early imaging findings in germ cell tumors arising from the basal ganglia. Pediatr Radiol 2016; 46: 719–26. doi: 10.1007/s00247-016-3542-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Villano JL, Virk IY, Ramirez V, Propp JM, Engelhard HH, McCarthy BJ. Descriptive epidemiology of central nervous system germ cell tumors: nonpineal analysis. Neuro Oncol 2010; 12: 257–64. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sano K. Pathogenesis of intracranial germ cell tumors reconsidered. J Neurosurg 1999; 90: 258–64. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.2.0258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsutani M, Sano K, Takakura K, Fujimaki T, Nakamura O, Funata N, et al. Primary intracranial germ cell tumors: a clinical analysis of 153 histologically verified cases. J Neurosurg 1997; 86: 446–55. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.3.0446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fujimaki T. Central nervous system germ cell tumors: classification, clinical features, and treatment with a historical overview. J Child Neurol 2009; 24: 1439–45. doi: 10.1177/0883073809342127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moon WK, Chang KH, Kim IO, Han MH, Choi CG, Suh DC, et al. Germinomas of the basal ganglia and thalamus: Mr findings and a comparison between Mr and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994; 162: 1413–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.6.8192009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rasalkar DD, Chu WCW, Cheng FWT, Paunipagar BK, Shing MK, Li CK. Atypical location of germinoma in basal ganglia in adolescents: radiological features and treatment outcomes. Br J Radiol 2010; 83: 261–7. doi: 10.1259/bjr/25001856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jennings MT, Gelman R, Hochberg F. Intracranial germ-cell tumors: natural history and pathogenesis. J Neurosurg 1985; 63: 155–67. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.63.2.0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kishore M, Monappa V, Rao L, Kudva R. Mixed malignant germ cell tumour of third ventricle with hydrocephalus: a rare case with recurrence. J Clin Diagn Res 2014; 8: 1903–5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9866.5124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sonoda Y, Kumabe T, Sugiyama S-I, Kanamori M, Yamashita Y, Saito R, et al. Germ cell tumors in the basal ganglia: problems of early diagnosis and treatment. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2008; 2: 118–24. doi: 10.3171/PED/2008/2/8/118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu C-C, Guo W-Y, Chang F-C, Luo C-B, Lee H-J, Chen Y-W, et al. Mri features of pediatric intracranial germ cell tumor subtypes. J Neurooncol 2017; 134: 221–30. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2513-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao S, Shao G, Guo W, Chen X, Liu Q. Intracranial pure yolk sac tumor in the anterior third ventricle of an adult: a case report. Exp Ther Med 2014; 8: 1471–2. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takahashi T, Ishikawa E, Masuda Y, Yamamoto T, Sato T, Shibuya M, et al. Mixed germ cell tumor with extensive yolk sac tumor elements in the frontal lobe of an adult. Case Rep Surg 2012; 2012: 1–5. doi: 10.1155/2012/473790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dufour C, Guerrini-Rousseau L, Grill J. Central nervous system germ cell tumors: an update. Curr Opin Oncol 2014; 26: 622–6. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chaganti RS, Houldsworth J. Genetics and biology of adult human male germ cell tumors. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 1475–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ho DM, Liu HC. Primary intracranial germ cell tumor. pathologic study of 51 patients. Cancer 1992; 70: 1577–84. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okamoto K, Ito J, Ishikawa K, Morii K, Yamada M, Takahashi N, et al. Atrophy of the basal ganglia as the initial diagnostic sign of germinoma in the basal ganglia. Neuroradiology 2002; 44: 389–94. doi: 10.1007/s00234-001-0735-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim DI, Yoon PH, Ryu YH, Jeon P, Hwang GJ. Mri of germinomas arising from the basal ganglia and thalamus. Neuroradiology 1998; 40: 507–11. doi: 10.1007/s002340050634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Phi JH, Cho B-K, Kim S-K, Paeng JC, Kim I-O, Kim IH, et al. Germinomas in the basal ganglia: magnetic resonance imaging classification and the prognosis. J Neurooncol 2010; 99: 227–36. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0119-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hirano H, Yokoyama S, Yunoue S, Yonezawa H, Yatsushiro K, Yoshioka T, et al. Mri T2 hypointensity of metastatic brain tumors from gastric and colonic cancers. Int J Clin Oncol 2014; 19: 596–602. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0596-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen Y-W, Huang P-I, Ho DM-T, Hu Y-W, Chang K-P, Chiou S-H, et al. Change in treatment strategy for intracranial germinoma: long-term follow-up experience at a single Institute. Cancer 2012; 118: 2752–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rogers SJ, Mosleh-Shirazi MA, Saran FH. Radiotherapy of localised intracranial germinoma: time to sever historical ties? Lancet Oncol 2005; 6: 509–19. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70245-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aoyama H, Shirato H, Yoshida H, Hareyama M, Nishio M, Yanagisawa T, et al. Retrospective multi-institutional study of radiotherapy for intracranial non-germinomatous germ cell tumors. Radiother Oncol 1998; 49: 55–9. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(98)00081-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goldman S, Bouffet E, Fisher PG, Allen JC, Robertson PL, Chuba PJ, et al. Phase II trial assessing the ability of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without second-look surgery to eliminate measurable disease for Nongerminomatous germ cell tumors: a children's Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 2464–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Souweidane MM, Krieger MD, Weiner HL, Finlay JL. Surgical management of primary central nervous system germ cell tumors: proceedings from the second International Symposium on central nervous system germ cell tumors. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2010; 6: 125–30. doi: 10.3171/2010.5.PEDS09112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]