Abstract

Background

Evidence for the diagnosis and management of cough due to acute bronchitis in immunocompetent adult outpatients was reviewed as an update to the 2006 “Chronic Cough Due to Acute Bronchitis: American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines.”

Methods

Acute bronchitis was defined as an acute lower respiratory tract infection manifested predominantly by cough with or without sputum production, lasting no more than 3 weeks with no clinical or any recent radiographic evidence to suggest an alternative explanation.

Two clinical population, intervention, comparison, outcome questions were addressed by systematic review in July 2017: (1) the role of investigations beyond the clinical assessment of patients presenting with suspected acute bronchitis, and (2) the efficacy and safety of prescribing medication for cough in acute bronchitis. An updated search was undertaken in May 2018.

Results

No eligible studies relevant to the first question were identified. For the second question, only one relevant study met eligibility criteria. This study found no difference in number of days with cough between patients treated with an antibiotic or an oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agent compared with placebo. Clinical suggestions and research recommendations were made based on the consensus opinion of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Conclusions

The panelists suggested that no routine investigations be ordered and no routine medications be prescribed in immunocompetent adult outpatients first presenting with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis, until such investigations and treatments have been shown to be safe and effective at making cough less severe or resolve sooner. If the cough due to suspected acute bronchitis persists or worsens, a reassessment and consideration of targeted investigations should be considered.

Key Words: bronchitis, cough, guidelines, infection

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PICO, population, intervention, comparison, outcome

Summary of Suggestions

1. For immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis, we suggest no routine investigation with chest x-ray, spirometry, peak flow measurement, sputum for microbial culture, respiratory tract samples for viral PCR, serum C-Reactive Protein (CRP) or procalcitonin (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

2. For immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis, to help establish the etiology if the acute bronchitis persists or worsens, we suggest that the patient is advised to seek reassessment and targeted investigation(s) be considered (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

Remarks: Suggested targeted investigations could include chest x-ray, sputum for microbial culture, peak expiratory flow rate recording(s), complete blood count and inflammatory markers such as CRP.

3. For immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to acute bronchitis, we suggest no routine prescription of antibiotic therapy, antiviral therapy, antitussives, inhaled beta agonists, inhaled anticholinergics, inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, oral NSAIDs or other therapies until such treatments have been shown to be safe and effective at making cough less severe or resolve sooner (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

4. For immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to acute bronchitis, if the acute bronchitis worsens, we suggest consideration for treatment with antibiotic therapy if a complicating bacterial infection is thought likely (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

Remarks: Differential diagnoses, such as exacerbations of chronic airways diseases (COPD, asthma, bronchiectasis) that may require other therapeutic management (such as with oral corticosteroids) should also be considered.

Background

Acute bronchitis, manifested by an acute cough and referring to inflammation of the trachea and lower airways, is a common clinical condition responsible for both primary care consultations and ED attendances.1

Currently, the diagnosis is clinical, with the importance of initial assessment being the exclusion of pertinent differential diagnoses. The CHEST 2006 guidelines recommended that acute bronchitis be diagnosed only if there was no evidence of pneumonia, the common cold, acute asthma, or an exacerbation of COPD.2

Previous retrospective cohort studies including patients with a diagnosis of acute bronchitis have found that at initial presentation just over one-third would also meet the criteria for a diagnosis of asthma and that 3 years after a diagnosis of acute bronchitis 34% of the cohort fulfilled criteria for either asthma or chronic bronchitis.3,4 The initial clinical evaluation is important in the longitudinal care of patients; in a retrospective study of 46 patients with a history of at least two similar physician-diagnosed episodes of acute bronchitis, 65% episodes were found to have mild asthma.5 Presentation with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis warrants a detailed review and exploration of preexisting health conditions, exposure history, and consideration of such differential diagnoses such as the common cold, cough variant asthma, acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis in a smoker, acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis, and acute rhinosinusitis.

Despite this, to date, it is not known whether there is additional value in the routine ordering of investigations such as chest x-rays, sputum cultures, measurement of serum inflammatory markers, or indeed other laboratory tests at initial presentation.

Acute bronchitis is considered to be a self-limiting condition but there remains data to suggest that practitioners frequently prescribe both antibiotics and other medication.6,7 The importance of antimicrobial stewardship is well recognized, as is the individual morbidity experienced from cough due to acute bronchitis, such as days off work and primary care consultations.8 There is a need to review the evidence for the benefit of routine prescriptions for cough due to acute bronchitis.

The 2006 guidelines encompassed both adult and pediatric patients and found no role for sputum cultures or viral or serologic assays in making the diagnosis of acute bronchitis but emphasized the importance of clinically and radiographically excluding other differential explanations for the presentation. The guidelines found no role for routine antibiotic use or mucokinetic agents, but suggested that in adults with accompanying wheeze, inhaled bronchodilator therapy may be useful.

This document sought to update the 2006 guidelines, reviewing the role of investigations in the diagnosis of acute bronchitis and the efficacy for medications in the management of cough due to acute bronchitis in immunocompetent adult patients.2 The suggestions made are intended to be useful for clinical practitioners assessing immunocompetent adult patients with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis, both in primary care and EDs.

Methods

The methodology of the CHEST Guideline Oversight Committee was used to select the Expert Cough Panel Chair and the international panel of experts in acute bronchitis to identify, evaluate, and synthesize the relevant evidence and to develop the suggestions that are contained within this paper. In addition to the quality of the evidence, the recommendation/suggestion grading also includes strength of recommendation dimension, used for all CHEST guidelines. The strength of recommendation here is based on consideration of three factors: balance of benefits to harms, patient values and preferences, and resource considerations. Further details of the methods for guideline development including management of conflicts of interests and transparency for all CHEST guidelines have been previously published.9

Key Question Development

Key clinical questions were developed using the population, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) format. The following two questions were addressed: (1) for immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis, is there added predictive value over history and physical examination alone from the addition of chest x-rays, spirometry, peak flow measurement, sputum for microbial culture, respiratory tract samples for viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR), serum C-reactive protein, or procalcitonin to rule out pneumonia, influenza, pertussis, asthma, or acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis?; and (2) for immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to acute bronchitis, what are the comparative effectiveness and safety of antibiotic therapy, antiviral therapy, antitussives, inhaled beta agonists, inhaled anticholinergics, inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or other therapies on cough and need for additional treatment?

We defined acute bronchitis as follows: an acute lower respiratory infection manifested predominantly by cough with or without sputum production, lasting no more than 3 weeks but with no clinical (eg, heart rate ≥ 100 beats/min, respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/min, oral temperature ≥ 37.8°C, and chest examination findings of adventitious sounds) or any recent radiographic evidence to suggest pneumonia and no other alternative explanation (eg, noninfective causes of cough, sinusitis, exacerbation of an underlying lower respiratory condition such as asthma, bronchiectasis, or COPD).

See Table 1 for the inclusion criteria for each question.

Table 1.

PICO Questions and Inclusion Criteria

| PICO Question | Study Characteristic | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| PICO question 1: for adult outpatients with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis,a is there added predictive value over history and physical alone from the addition of CXR, pulmonary function testing, sputum for microbial culture, PCR for virus, C-reactive protein, or procalcitonin to rule out pneumonia, influenza, pertussis, asthma, or acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis? | Study design |

|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Comparator | History and physical alone | |

| Outcomes |

|

|

| PICO question 2: for adult outpatients with cough due to acute bronchitis,a what are the comparative effectiveness and safety of antibiotic therapy, antiviral therapy, antitussives, inhaled beta agonists, anticholinergics, inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, NSAIDs, or other therapies on cough and need for additional treatment? (Note that the decision was made to exclude alternative therapies without FDA or other regulatory approval.) | Study design |

|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Comparator |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

CXR = chest x-ray; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; GRACE = the Genomics to combat Resistance against Antibiotics in Community-acquired LRTI in Europe (GRACE consortium); NSAID = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; PICO = population, intervention, comparison, outcome; RCT = randomized controlled trial; ROC = receiver operating characteristic.

An acute lower respiratory infection manifested predominantly by cough with or without sputum production, lasting no more than 3 wk but with no clinical (eg, heart rate ≥ 100 beats/min, respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/min, oral temperature ≥ 37.8°C, and chest examination findings of adventitious sounds) or radiographic evidence to suggest pneumonia and no other alternative explanation (eg, noninfective causes of cough—sinusitis, exacerbation of an underlying lower respiratory condition such as asthma, bronchiectasis, or COPD).

Protocol

The systematic review was registered with PROSPERO – The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews and can be accessed online (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=78153).

Systematic Literature Search

Education and Clinical Services Librarian, Nancy Harger, MLS, working in the University of Massachusetts Medical School Library, performed all systematic literature searches for each PICO question in the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The date limitations were from database inception through August 7, 2017, for PICO question 1 and through July 17, 2017, for PICO question 2. Searches were restricted to English language. Search strategies for PICO questions 1 and 2 are presented in e-Appendix 1. After completion of the systematic review, an updated search in PubMed alone was conducted on May 16, 2018, for both PICO questions using the same search strategies to see if new studies were available.

To achieve dual review, four panelists were divided into two pairs and the retrieval divided in half. Panelists independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of their assigned search results to identify potentially relevant articles based on the inclusion criteria specified in Table 1. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Studies determined to be eligible based on abstract review underwent a second round of full-text screening for final inclusion. Important data from each included study were then extracted into structured evidence tables. In each step, dual review and dual extraction were performed and resolved by discussion.

Quality Assessment

All included studies were then subject to quality assessment by the methodologist (B. I.). Systematic reviews were assessed using the Documentation and Appraisal Review Tool.10 Randomized controlled trials were assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.11 Observational studies were assessed using the Cochrane bias methods group’s tool to assess risk of bias in cohort studies.12 Diagnostic studies were evaluated using the modified QUADAS form for diagnostic studies.13 Studies at high risk of bias or of poor quality were excluded.

Grading the Evidence and Development of Recommendations

When possible, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) evidence profiles were created to grade the overall quality of the body of evidence supporting the outcomes for each intervention based on five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The quality of the evidence for each outcome is rated as high, moderate, or low, modified from GRADE standards.14

The panel could draft recommendations for each key clinical question that had sufficient evidence. Recommendations would be graded using the CHEST grading system, which is composed of two parts: the strength of the recommendation (either strong or weak) and a rating of the overall quality of the body of evidence. In the case of weak or insufficient evidence, when guidance was still warranted, a weak suggestion could be developed and either graded 2C or labeled Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement.9

All drafted suggestions were presented to the full panel in an anonymous voting survey to achieve consensus through a modified Delphi technique. Panelists were requested to indicate their level of agreement on each statement, using a 5-point Likert scale.9 Panelists also had the option to provide open-ended feedback on each statement with suggested edits or general comments. For a suggestion to pass, it required at least 75% of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel to vote and at least 80% of the votes to agree or strongly agree with the statement. All of the suggestions presented in this paper met these rigorous thresholds and no CHEST Expert Cough Panelist was excluded from voting. A patient representative who had been a member of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel provided patient-centered input for this expert panel report and approved of the suggestions contained herein.

Peer Review Process

The manuscript with suggestions went through two rounds of review. During the first round, reviewers from the Guidelines Oversight Committee of the CHEST Organization reviewed the content and methods of the manuscript for consistency, accuracy, and completeness. The manuscript was revised after consideration by the panel of the feedback received from the Guidelines Oversight Committee reviewers and then submitted to the CHEST journal for review by a representative from the CHEST Board of Regents, one of the four CHEST Presidents, and journal-identified reviewers. Because none of the suggestions were revised, voting did not need to be undertaken again by the entire panel.

Subsequent Guidelines

Future updates to this guideline will be conducted in accordance with the previously published CHEST methodology.9,15

Results

Search results for each PICO question are presented at the beginning of each summary.

PICO Question 1

For immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis, is there added predictive value over history and physical examination alone from the addition of chest x-rays, spirometry, peak flow measurement, sputum for microbial culture, respiratory tract samples for viral PCR, serum C-reactive protein, or procalcitonin to rule out pneumonia, influenza, pertussis, asthma, or acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis?

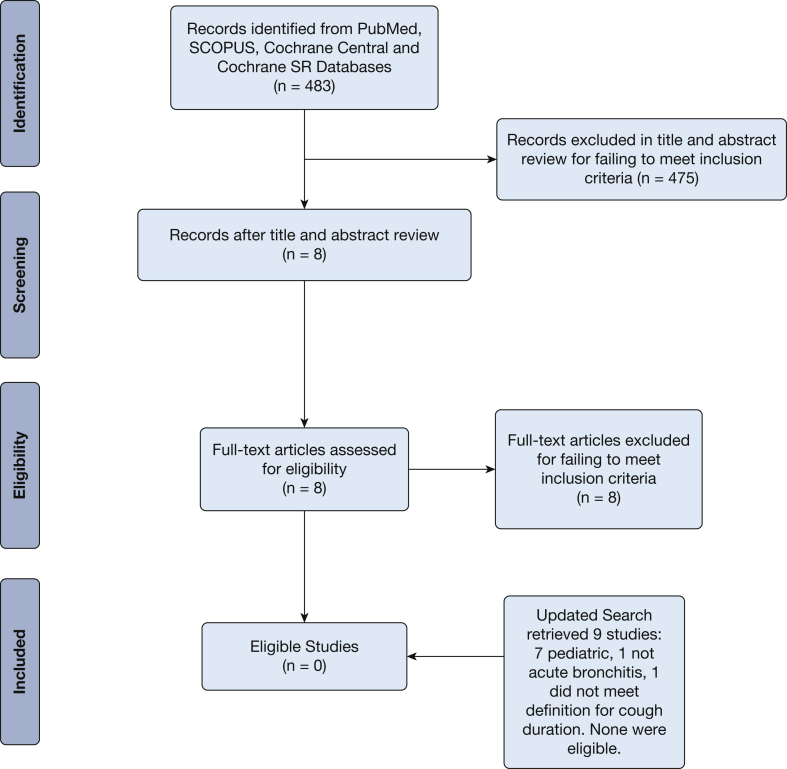

For PICO question 1, the first search of PubMed (including unindexed papers and systematic reviews) identified 242 studies. Scopus search identified 238 studies after duplicates were removed. A search of Cochrane systematic reviews found three studies after duplicates were removed. This totaled 483 studies retrieved. Eight studies out of the 483 proceeded to full text review where no studies were determined to meet all inclusion and exclusion criteria specified by the panel.

The PICO question 1 updated search retrieved nine studies; seven were pediatric studies, one was not acute bronchitis, and one was acute bronchitis but did not meet the definition for cough duration. None were eligible. The search summary is presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Acute bronchitis population, intervention, comparison, outcome question 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart. SR = Systematic Review.

Summary of Evidence and Discussion

Our systematic review of the literature retrieved no papers meeting all inclusion criteria to specifically address the PICO question on the added predictive value of chest x-rays, spirometry, peak flow measurement, sputum for microbial culture, respiratory tract samples for viral PCR, serum CRP, or procalcitonin over history and physical examination alone to rule out pneumonia, influenza, pertussis, asthma, or acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Nearly one-half of the 483 studies were excluded for not meeting study design criteria and almost another one-half were excluded for ineligible patient populations. Many of the ineligible population studies were excluded for focusing on subjects with conditions such as the common cold, chronic bronchitis, acute exacerbations of COPD, asthma, pneumonia, and other respiratory conditions or for including children. The diagnosis of acute bronchitis as an entity in its own right may be clinically challenging but using a robust definition for the diagnosis would be helpful for future randomized controlled studies.

The following represents gaps in knowledge. Defining populations to account for comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus would be of clinical importance to physicians and internationally agreed standards for inclusion criteria such as age for adult population studies would also provide a stronger evidence base from which to draw conclusions. In addition to exploring the predictive value of routine laboratory and other investigations in the diagnosis of cough in acute bronchitis, it would be useful to evaluate the predictive value of the test with the duration and severity of acute bronchitis.

Suggestions

1. For immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis, we suggest no routine investigation with chest x-ray, spirometry, peak flow measurement, sputum for microbial culture, respiratory tract samples for viral PCR, serum C-Reactive Protein (CRP) or procalcitonin (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

2. For immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis, to help establish the etiology if the cough due to suspected acute bronchitis persists or worsens, we suggest that the patient is advised to seek reassessment and targeted investigation(s) be considered (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

Remarks: Suggested targeted investigations could include chest x-ray, sputum for microbial culture and peak expiratory flow rate(s) complete blood count and inflammatory markers such as CRP.

PICO Question Two

For adult outpatients with cough due to acute bronchitis, what are the comparative effectiveness and safety of antibiotic therapy, antiviral therapy, antitussives, inhaled beta agonists, inhaled anticholinergics, inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, oral NSAIDs, or other therapies on cough and need for additional treatment?

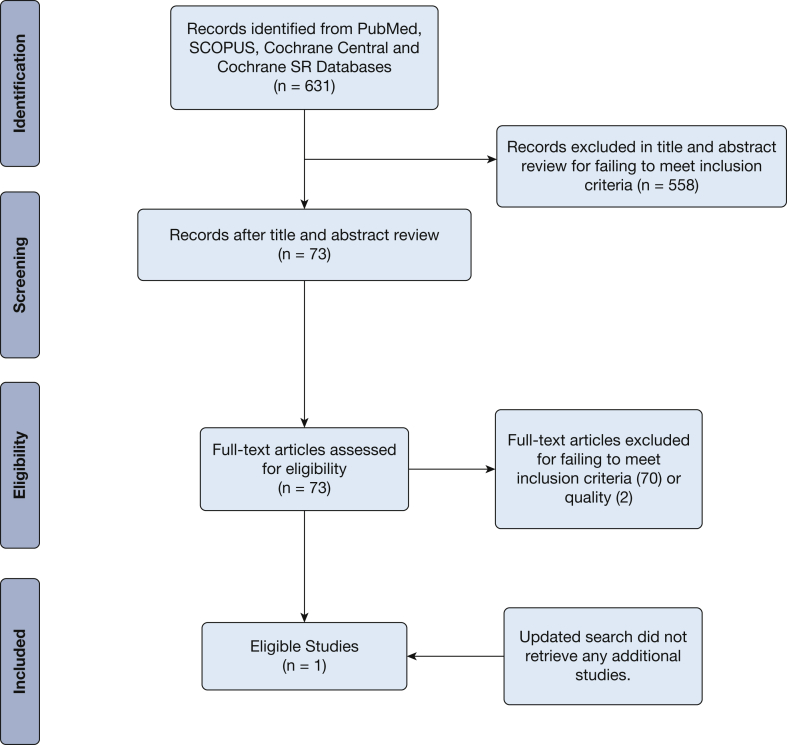

For PICO question 2, the first search of PubMed (including unindexed papers and systematic reviews) identified 292 studies. Scopus search identified 143 studies after duplicates removed. A search of Cochrane systematic reviews found 28 studies after duplicates were removed, and 168 unique studies were identified from a search of Cochrane Central. This totaled 631 studies retrieved. Seventy-three studies out of the 631 proceeded to full-text review, where only one study was determined to meet all inclusion and exclusion criteria specified by the panel.16 Almost two-thirds of the 630 studies excluded were for ineligible patient populations and the rest were almost evenly split between ineligible study design and ineligible interventions. Many of the studies excluded for ineligible population once again focused on subjects with conditions such as common cold, chronic bronchitis, acute exacerbations of COPD, asthma, pneumonia, and other respiratory conditions or for including children.

The PICO question 2 updated search retrieved no new studies. The search summary is presented in a PRISMA flowchart in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Acute bronchitis population, intervention, comparison, outcome question 2 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart. SR = Systematic Review.

Summary of Evidence and Discussion

Our systematic review of the literature discovered one study that met all inclusion criteria to address the PICO question on the comparative effectiveness and safety of antibiotic therapy, antiviral therapy, antitussives, inhaled beta agonists, inhaled anticholinergics, inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, oral NSAIDs, or other therapies on cough and need for additional treatment in immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to acute bronchitis.16

The study by Llor et al16 was a multicenter, single-blinded randomized controlled trial in 416 adults with symptoms of respiratory infection (including cough, colored sputum, and at least one of the following: dyspnea, wheezing, chest discomfort, or chest pain) for < 1 weeks’ duration who attended primary care centers in Spain. They were randomly assigned to one of three treatment regimens: ibuprofen 600 mg, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 500 mg/125 mg, or placebo three times a day for 10 days. The primary outcome was the number of days with frequent cough. Median days with frequent cough were reported for each group as follows: ibuprofen: 9 days (95% CI, 8-10), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid: 11 days (95% CI, 10-12), and placebo: 11 days (95% CI, 8-14).

The authors concluded no significant differences were observed in the number of days with cough between patients with uncomplicated acute bronchitis and discolored sputum treated with ibuprofen, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, or placebo.

This PICO question excluded studies involving the efficacy and safety of herbal and complementary therapies for cough in acute bronchitis. Many of these therapies are not regulated nor considered as therapeutic options by medical providers in many countries.

There is insufficient evidence to confirm or refute the efficacy of prescribed treatments for cough due to acute bronchitis. An obvious gap that came out of this systematic review is that randomized controlled studies of treatments with rigorously defined patient populations of sufficient duration are necessary.

Suggestions

3. For immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to acute bronchitis, we suggest no routine prescription of antibiotic therapy, antiviral therapy, antitussives, inhaled beta agonists, inhaled anticholinergics, inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, oral NSAIDs or other therapies until such treatments have been shown to be safe and effective at making cough less severe or resolve sooner (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

4. For immunocompetent adult outpatients with cough due to acute bronchitis, if the acute bronchitis worsens, we suggest consideration for treatment with antibiotic therapy if a complicating bacterial infection is thought likely (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

Remarks: Differential diagnoses, such as exacerbations of chronic airways diseases (COPD, asthma, bronchiectasis) that may require other therapeutic management (such as with oral corticosteroids) should also be considered.

Areas for Future Research

First, there is a need for randomized controlled trials in adult patients with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis to assess the potential role for both antibiotic and nonantibiotic treatments. Patients with conditions that may mimic acute bronchitis such as cough variant asthma, acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, acute exacerbations of bronchiectasis, bacterial sinusitis, and the common cold should be excluded. Until these exclusionary conditions are considered and ruled out, the true frequency of acute bronchitis as a distinct clinical entity will not be known.

Second, there is a need for studies to routinely use reliable and valid cough outcome measures to assess resolution of episodes of cough due to suspected acute bronchitis.

Conclusions

For immunocompetent adult outpatients presenting with cough due to suspected acute bronchitis, we suggest no routine investigation. If the cough persists or worsens, we suggest reassessment and consideration of targeted investigations. We suggest no routine prescription of antibiotic therapy, antiviral therapy, antitussives, inhaled beta agonists, inhaled anticholinergics, inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, oral NSAIDs, or other therapies. If the cough due to suspected acute bronchitis worsens, we suggest reassessment and consideration for treatment with antibiotic therapy if a bacterial infection is thought likely or treatment for other alternative conditions deemed likely.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the design and analysis of the study and writing of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: CHEST was the sole supporter of these guidelines, this article, and the innovations addressed within.

∗CHEST Expert Cough Panel Collaborators: Todd M. Adams, MD (Webhannet Internal Medicine Associates of York Hospital, York, ME); Kenneth W. Altman, MD, PhD (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX); Elie Azoulay, MD, PhD (University of Paris, Paris, France); Alan F. Barker, MD (Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR); Fiona Blackhall, MD, PhD (University of Manchester, Department of Medical Oncology, Manchester, England); Surinder S. Birring, MBChB, MD (Division of Asthma, Allergy and Lung Biology, King’s College London, Denmark Hill, London, England); Donald C. Bolser, PhD (College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL); Louis-Philippe Boulet, MD, FCCP (Institut universitaire de cardiologie et de pneumonlogie de Québec, Quebec [IUCPQ], QC, Canada); Sidney S. Braman, MD, FCCP (Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY); Christopher Brightling, MBBS, PhD, FCCP (University of Leicester, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, England); Priscilla Callahan-Lyon, MD (Adamstown, MD); Anne B. Chang, MBBS, PhD, MPH (Royal Children’s Hospital, Queensland, Australia); Terrie Cowley (The TMJ Association, Milwaukee, WI); Paul Davenport, PhD (Department of Physiological Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL); Ali A. El Solh, MD, MPH (University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY); Patricio Escalante, MD, MSc, FCCP (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN); Stephen K. Field, MD (University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada); Dina Fisher, MD, MSc (University of Calgary, Respiratory Medicine, Calgary, AB, Canada); Cynthia T. French, PhD, FCCP (UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, MA); Cameron Grant, MB ChB, PhD (University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand); Susan M. Harding, MD, FCCP (Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL); Anthony Harnden, MB ChB, MSc (University of Oxford, Oxford, England); Adam T. Hill, MB ChB, MD (Royal Infirmary and University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland); Richard S. Irwin, MD, Master FCCP (UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, MA); Peter J. Kahrilas, MD (Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL); Joanne Kavanagh, MBChB (Division of Asthma, Allergy and Lung Biology, King’s College London, Denmark Hill, London, England), Kefang Lai, MD, PhD (First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical College, Guangzhou, China); Andrew P. Lane, MD (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD), Craig Lilly, MD, FCCP (UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, MA); Mark Lown, MBBS, PhD, (University of Southampton, Aldermoor Health Centre, Aldermorr Close, Southampton, England); J. Mark Madison, MD, FCCP (UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, MA); Mark A. Malesker, PharmD, FCCP (Creighton University School of Pharmacy and Health Professions, Omaha, NE); Stuart Mazzone, PhD, FCCP (University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia); Lorcan McGarvey, MD (The Queens University Belfast, Belfast, Northern Ireland); Alex Molasoitis, PhD, MSc, RN (Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China); M. Hassan Murad, MD, MPH (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN); Mangala Narasimhan, DO, FCCP (Hofstra-Northwell Health, Manhasset, NY); Peter Newcombe, PhD (School of Psychology University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia); John Oppenheimer, MD (UMDNJ-Rutgers University); Mark Rosen, MD, Master FCCP (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY); Bruce Rubin, MEngr, MD, MBA (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA); Richard J. Russell, MBBS, (University of Leicester, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, England); Jay H. Ryu, MD, FCCP (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN); Sonal Singh, MD, MPH (UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, MA); Jaclyn Smith, MB ChB, PhD (University of Manchester, Manchester, England); Maeve P. Smith, MB ChB, MD (University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada); Susan M. Tarlo, MBBS, FCCP (Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada); Anne E. Vertigan, PhD, MBA, BAppSc (SpPath) (John Hunter Hospital, New Lambton Heights, NSW, Australia); and Miles Weinberger, MD, FCCP (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA).

Endorsements: This guideline has been endorsed by the American Association for Respiratory Care.

Other contributions: We thank Nancy Harger, MLS, Education and Clinical Services Librarian, University of Massachusetts Medical School Library, Worcester, MA, who undertook all the searches for the systematic reviews.

Additional information: The e-Appendix can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article. CHEST Expert Panel Collaborator, Mark Rosen, MD, FCCP, died July 2, 2019.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Dr Linder is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging [R21AG057400, R21AG057396, R33AG057383], National Institute on Drug Abuse [R33AG057395], Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [R01HS024930, R01HS026506], The Peterson Center on Healthcare, and a contract from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [HHSP233201500020].

DISCLAIMER: CHEST Guidelines are intended for general information only, are not medical advice, and do not replace professional medical care and physician advice, which should always be sought for any medical condition. The complete disclaimer for this guideline can be accessed at: http://www.chestnet.org/Guidelines-and-Resources.

Contributor Information

Maeve P. Smith, Email: maeve1@ualberta.ca.

CHEST Expert Cough Panel:

Todd M. Adams, Kenneth W. Altman, Elie Azoulay, Alan F. Barker, Fiona Blackhall, Surinder S. Birring, Donald C. Bolser, Louis-Philippe Boulet, Sidney S. Braman, Christopher Brightling, Priscilla Callahan-Lyon, Anne B. Chang, Terrie Cowley, Paul Davenport, Ali A. El Solh, Patricio Escalante, Stephen K. Field, Dina Fisher, Cynthia T. French, Cameron Grant, Susan M. Harding, Anthony Harnden, Adam T. Hill, Richard S. Irwin, Peter J. Kahrilas, Joanne Kavanagh, Kefang Lai, Peter J. Kahrilas, Craig Lilly, Mark Lown, J. Mark Madison, Mark A. Malesker, Stuart Mazzone, Lorcan McGarvey, Alex Molasoitis, M. Hassan Murad, Mangala Narasimhan, Peter Newcombe, John Oppenheimer, Mark Rosen, Bruce Rubin, Richard J. Russell, Jay H. Ryu, Sonal Singh, Jaclyn Smith, Maeve P. Smith, Susan M. Tarlo, Anne E. Vertigan, and Miles Weinberger

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Woodhead M., Blasi F., Ewig S. Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections--full version. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(suppl 6):E1–E59. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braman S.S. Chronic cough due to acute bronchitis: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 suppl):95S–103S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.95S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thiadens H.A., Postma D.S., de Bock G.H., Huysman D.A., van Houwelingen H.C., Springer M.P. Asthma in adult patients presenting with symptoms of acute bronchitis in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18(3):188–192. doi: 10.1080/028134300453412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonsson J.S., Gislason T., Gislason D., Sigurdsson J.A. Acute bronchitis and clinical outcome three years later: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 1998;317(7170):1433. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7170.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallett J.S., Jacobs R.L. Recurrent acute bronchitis: the association with undiagnosed bronchial asthma. Ann Allergy. 1985;55(4):568–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raherison C., Poirier R., Daures J.P. Lower respiratory tract infections in adults: non-antibiotic prescriptions by GPs. Respir Med. 2003;97(9):995–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)00030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulliford M.C., Dregan A., Moore M.V. Continued high rates of antibiotic prescribing to adults with respiratory tract infection: survey of 568 UK general practices. BMJ Open. 2014;4(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hordijk P.M., Broekhuizen B.D., Butler C.C. Illness perception and related behaviour in lower respiratory tract infections-a European study. Fam Pract. 2015;32(2):152–158. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis S.Z., Diekemper R., Ornelas J., Casey K.R. Methodologies for the development of CHEST guidelines and expert panel reports. Chest. 2014;146(1):182–192. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diekemper R.L.I.B., Merz L.R. Development of the Documentation and Appraisal Review Tool for systematic reviews. World J Metaanal. 2015;3(3):142–150. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins J.P., Altman D.G., Gotzsche P.C. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterne J.A., Hernan M.A., Reeves B.C. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiting P., Rutjes A.W., Reitsma J.B., Bossuyt P.M., Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balshem H., Helfand M., Schunemann H.J. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis S.Z., Diekemper R.L., French C.T., Gold P.M., Irwin R.S., CHEST Expert Cough Panel Methodologies for the development of the management of cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2014;146(5):1395–1402. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llor C., Moragas A., Bayona C. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory or antibiotic treatment in patients with non-complicated acute bronchitis and discoloured sputum: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f5762. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.