Abstract

As one step in developing a measure of hand contamination with respiratory viruses, this study assessed if human rhinovirus (HRV) was detectable on hands in a low income non-temperate community where respiratory disease is a leading cause of child death. Research assistants observed residents in a low income community in Dhaka, Bangladesh. When they observed a resident sneeze or pick their nose, they collected a hand rinse and anterior nare sample from the resident. Samples were first tested for HRV RNA by real-time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR). A subset of rRT-PCR positive samples were cultured into MRC-5 and HeLa Ohio cells. Among 177 hand samples tested for HRV by real-time RT-PCR, 52 (29%) were positive. Among 15 RT-PCR positive hand samples that were cultured, two grew HRV. HRV was detected in each of the sampling months (January, February, June, July, November, and December). This study demonstrates in the natural setting that, at least after sneezing or nasal cleaning, hands were contaminated commonly with potentially infectious HRV. Future research could explore if HRV RNA is present consistently and is associated sufficiently with the incidence of respiratory illness in communities that it may provide a proxy measure of respiratory viral hand contamination.

Keywords: rhinovirus, handwashing, Bangladesh, hand

INTRODUCTION

In randomized controlled trials, people who were encouraged to wash their hands regularly with soap or disinfect them with alcohol-based gel had fewer symptomatic respiratory infections compared with groups who did not receive these interventions [White et al., 2003; Luby et al., 2005; Rabie and Curtis, 2006; Bowen et al., 2007; Talaat et al., 2011].

The efficacy of handwashing interventions to interrupt transmission of enteric pathogens can be assessed by measuring the concentration of fecal indicator bacteria from hand rinse specimens. The concentration of these organisms are associated with the occurrence of diarrhea and so provide a proxy measurement of the efficacy of handwashing promotion interventions [Luby et al., 2007; Pickering et al., 2010]. There is no analogous assay to assess the efficacy of handwashing interventions on interrupting respiratory virus transmission.

There are limited data on the impact of handwashing on specific respiratory pathogens. In one handwashing promotion trial in Cairo, Egypt, students attending schools that received the handwashing intervention had 50% fewer absences associated with confirmed influenza infections [Talaat et al., 2011].

There is a rich, but inconclusive literature on the role of hand transmission of human rhinovirus (HRV) in wealthy countries in temperate climates. People with symptomatic HRV respiratory infections commonly have culturable HRV on their hands [Hendley et al., 1973; Reed, 1975; D’Alessio et al., 1976]. Intervention trials to reduce hand transmission of rhinovirus have produced mixed results. Mothers randomized to treat their hands with aqueous iodine after one of their children developed symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection were 40% less likely to develop symptomatic rhinovirus infection compared with mothers who treated their hands with a similarly colored placebo [Hendley and Gwaltney, 1988]. By contrast adults randomized to receive a hand lotion that contained organic acids with persistent activity against rhinovirus, were just as likely to develop rhinovirus infection compared with controls [Turner et al., 2012]. There has been little investigation of the presence or potential role of respiratory viruses on hands in settings where respiratory disease are the leading cause of child deaths.

As one step in developing a measure of hand contamination with respiratory viruses, this study assessed if HRV would be detectable on hands in a low income non-temperate community where respiratory disease is a leading cause of child death. As part of a randomized controlled trial that encouraged hand washing with soap or a waterless hand sanitizer and evaluated hand washing practices and fecal indicator bacteria on hands [Luby et al., 2010], research assistants also collected hand rinse samples for HRV detection. The objective of this analysis was to assess if hands were contaminated commonly with viable HRV in these communities.

METHODS

The methods of the larger trial have been reported previously [Luby et al., 2010]. Briefly, this study was conducted in the Kamalapur neighborhood of Dhaka, Bangladesh, a densely populated low income community with a high incidence of childhood respiratory disease [Brooks et al., 2010]. Fieldworkers identified 30 eligible housing compounds. Compounds were assigned randomly to different hand hygiene interventions, but for this analysis the data from the different groups were analyzed together.

The research assistant arrived in the participating compound by 7:00 AM on the day of observation. Within 10 min of observing a compound resident sneeze, the research assistant collected a hand rinse and an anterior nare swab sample from the resident. If no compound resident had sneezed by 10:00 AM, then the research assistant collected a hand rinse and anterior nares sample from a compound resident who either picked his/her nose, coughed, had a runny nose or who entered the compound after being outside for more than 60 min. Handwashing with soap or sanitizer was observed in only 3 of 1186 episodes of coughing, sneezing, or nose-picking among the study population [Luby et al., 2010]. Study subjects with symptoms of respiratory illness were enrolled to minimize the risk that the rate of detection of virus from asymptomatic residents would be too low to assess.

To collect the hand rinse sample, the research assistant instructed the resident to insert his or her hand in a sterile 1 L bag containing 20 ml of viral transport media [VTM; Dulbecco’s MEM containing 2.5% bovine serum albumin fraction V, 1% glutamine, 2% HEPES buffer, 1% penicillin–streptomycin (100,000 U penicillin, 10 mg/ml streptomycin), and 1.0% amphotericin B, pH 7.4] and rub his or her fingers against their palm and thumb. After collecting the anterior nares specimen, the assistant broke the swab tips off into vials that contained VTM. The bag and vials were placed on ice and transported to the ICDDR,B laboratory. In the laboratory, a technician concentrated potential HRV in the hand rinse samples by ultracentrifugation [Chapple and Harris, 1966]. Briefly, 14 ml of VTM wash was centrifuged at 30,000 rpm (67,000g) for 2 h at 4°C (Beckman SW 40 Ti), the supernatant discarded and the pellet resus-pended in 1 ml of cold VTM. The enriched sample was transferred immediately to a sterile cryovial and stored at −70°C until shipping on dry ice to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for HRV testing.

All participants provided informed consent. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of ICDDR,B. Because the nasal swab collection was added as a later amendment to the protocol, field worker did not collect nasal samples at the baseline.

Total nucleic acid was extracted from 200 μl of each swab/hand rinse sample using a NucliSENS® easy-MAG® (bioMérieux, Durham, NC). Samples were first tested for HRV RNA by an in-house real-time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR) assay [Lu et al., 2008]. rRT-PCR positive samples were inoculated into MRC-5 and HeLa Ohio cells known to be permissive for HRV culture. Prior to inoculation into cell culture, the hand rinse concentrates were extracted with an equal volume of chloroform to remove potential bacterial and fungal contaminants. Briefly, cells were grown on slanted stationary 15 ml glass tubes in Eagle’s MEM growth media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT) and 30 mM Mg + + (for the HeLa Ohio cells), pH adjusted to 7.0–7.2 (HEPES). When cells reached near confluency (~2 days), the growth media was removed and the cells washed with sterile phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.2 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were then inoculated with 200 μl of the sample and incubated on slant at room temperature with gentle rocking for 1 hr. Two milliliters of maintenance media (as above, but with 2% fetal bovine serum) was then added to the cells and the tubes were loaded onto a roller drum in a 33°C incubator with 5% CO2 and rolled at low speed. Cultures were observed for cytopathic effect (CPE) at 2-day intervals for up to 10 days. If CPE was observed, cultures were frozen at −70°C and 100 μl of the cell lysate screened for HRV by rRT-PCR. If no CPE was observed, a second passage of the culture lysate was prepared (without chloroform) and inoculated as above. rRT-PCR was performed on the second passage and if negative, the sample was presumed to be culture negative for HRV.

RESULTS

Most samples were collected from children, 53% from children under age 10 years (Table I). The Human Rhinovirus in Bangladesh median level of education among participating adults was 0 years (inter quartile range [IQR]: 0–4). The median monthly per capita income was 22.5 US$ (IQR: 15–30).

TABLE I.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age groups (years) (N = 166a) | |

| <5 | 34 (57) |

| 5–<10 | 19 (31) |

| 10–<20 | 18 (30) |

| 20–40 | 22 (36) |

| >40 | 7 (12) |

| Males (N = 166a) | 43 (72) |

| Education (years) (N = 141b) | |

| None | 62 (88) |

| 1–5 | 18 (26) |

| >5–<10 | 18 (25) |

| ≥10 | 1 (2) |

| Per capita monthly household income (US$)c | |

| <7.5 | 5 (7/139) |

| 7.5–<75 | 93 (129/139) |

| >75 | 3 (3/139) |

Eleven samples were not linked to baseline age and gender information.

Education analysis restricted to the 141 study subject >age 1 year.

Analysis restricted to 139 households who reported income and could be linked to the sample; 1 US$ = 66.7 Taka.

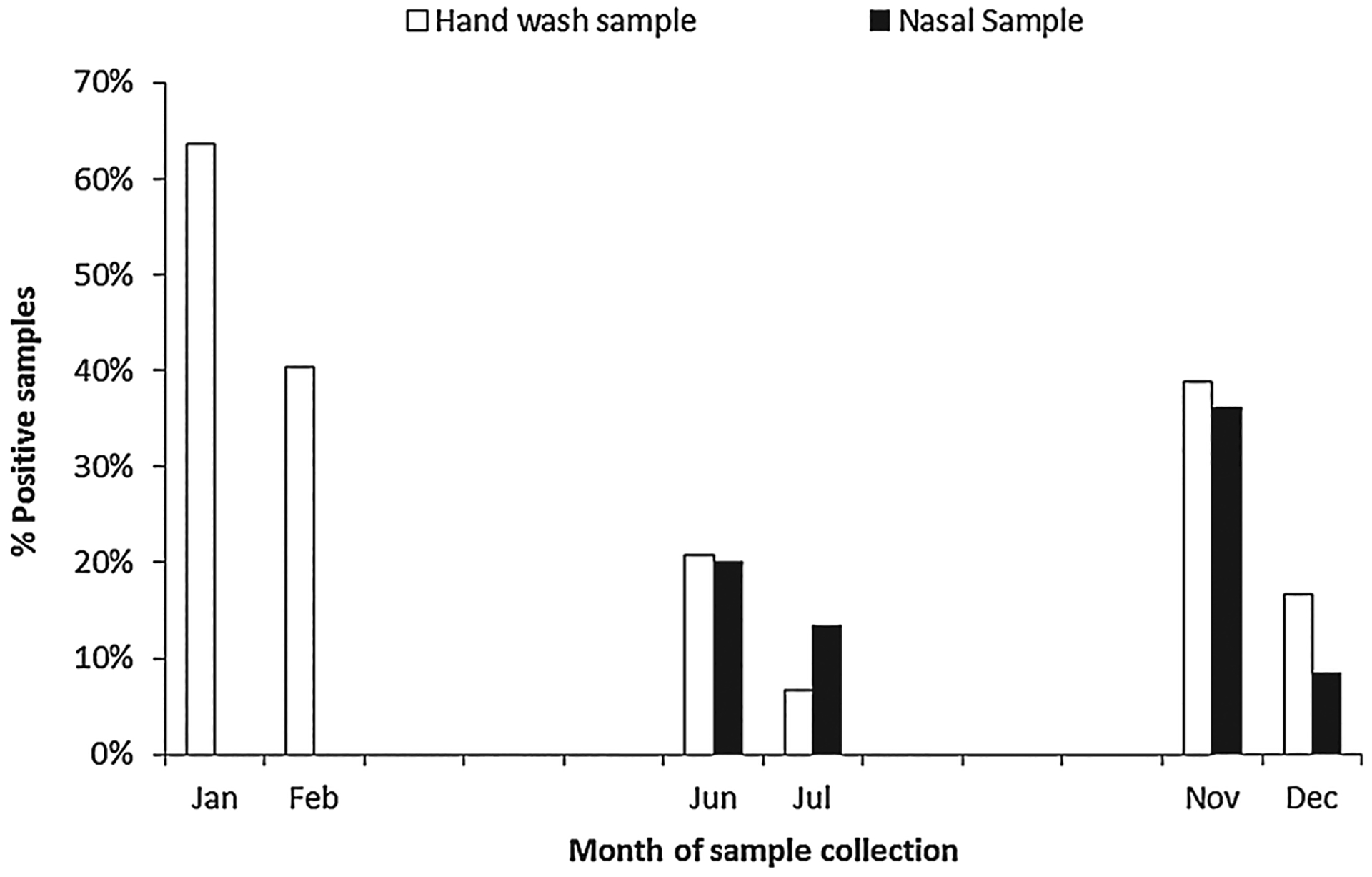

Research assistants collected and analyzed 177 hand rinse samples and 120 nasal swab samples from 30 compounds (Table II). Most samples, 140 (79%) hand rinse and 109 (92%) nasal, were collected after sneezing. Overall, among 177 hand rinse samples, 52 (29%) were RT-PCR positive for HRV RNA. HRV RNA was detected in each of the 6 months when samples were collected (Fig. 1). Among 120 nasal samples, 25 (21%) were rRT-PCR positive for HRV RNA. Of the 24 nasal samples that were rRT-PCR positive and cultured, 6 (25%) grew HRV; of 15 hand rinse samples that were rRT-PCR positive and cultured, 2 (13%) grew HRV. HRV RNA was detected more commonly after nose picking than after sneezing (54% vs. 26%, P = 0.01).

TABLE II.

Collected Samples and HRV rRT-PCR Results

| Exposure | Hand samples tested by rRT-PCR | Hand samples positive n (%) | Nasal samples tested by rRT-PCR | Nasal samples positive n (%) | Paired hand and nasal samples tested by rRT-PCR | Both hand and nasal sample positive n (%) | Nasal sample positive, but hand sample negative n (%) | Hand sample positive, but nasal sample negative n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After sneezing | 140 | 36 (26) | 110 | 22 (20) | 109 | 19 (17) | 3 (3) | 5 (5) |

| After nose picking | 26 | 14 (54) | 3 | 1 (33) | 3 | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Coughing | 6 | 1 (17) | 4 | 1 (25) | 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) |

| Runny nose | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 | 1 (100) | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| After coming from outside | 3 | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 177 | 52 (29) | 120 | 25 (21) | 119 | 20 (17) | 5 (5) | 6 (5) |

Fig. 1.

Human rhinovirus detections by month.

Among the 110 participants who had both a hand and nasal specimen tested, 20 were rRT-PCR positive for HRV on both their hand rinse and nasal specimen, five had HRV RNA detected only on the nasal specimen, and six only on the hand specimen (Table II). Among the six residents whose hands were HRV rRT-PCR positive, but whose nasal specimens were rRT-PCR negative, none of their hand wash samples grew HRV on culture; two samples grew non-polio enteroviruses.

DISCUSSION

In this densely populated low income urban community where respiratory diseases were a leading cause of child death, hands were contaminated frequently with HRV after sneezing. Although it is likely that some of the PCR positive results reflected viral RNA fragments that were not infectious viral particles, the prevalence of viable HRV on the hands of study participants was likely underestimated by the culture results since HRV RNA was identified more commonly, and recovery by culture is less sensitive [van Kraaij et al., 2005; Loens et al., 2006].

The most common source of HRV in the present study was apparently from the study subjects’ own respiratory tract. Indeed, recovery of HRV might even have been higher if study workers collected nasopharyngeal samples rather than sampling the anterior nares. In two previous studies of patients with culturally confirmed HRV, the virus was recovered rarely from the saliva/mucus ejected by sneezing [Hendley et al., 1973; Gwaltney et al., 1978]. It is likely that these HRV rRT-PCR positive samples represent the ongoing hand contamination associated with symptomatic respiratory illness. The role that contaminated hands play in HRV transmission in these communities is an open question.

The concentration of thermotolerant coliforms or E. coli on hands provides a measure of bacterial hand contamination that is associated with the risk of diarrhea in settings where diarrhea is a leading cause of death [Luby et al., 2007; Pickering et al., 2010]. This study demonstrates that at least after sneezing or nasal cleaning, hands were commonly contaminated with HRV RNA. The price of molecular detection will likely continue to decline. Future research could explore if HRV RNA is consistently present and is associated sufficiently with the incidence of respiratory illness in communities that it may serve as a proxy measure of respiratory viral hand contamination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ICDDR,B acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of the Procter & Gamble Company and CDC to the Centre’s research efforts. The authors appreciate Farzana Yeasmin’s supervision of field work and Goutam Podder’s assistance with specimen handling.

Grant sponsor: Procter & Gamble Company; Grant sponsor: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

REFERENCES

- Bowen A, Ma H, Ou J, Billhimer W, Long T, Mintz E, Hoekstra RM, Luby S. 2007. A cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of a handwashing-promotion program in chinese primary schools. Am J Trop Med Hyg 76:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks WA, Goswami D, Rahman M, Nahar K, Fry AM, Balish A, Iftekharuddin N, Azim T, Xu X, Klimov A, Bresee J, Bridges C, Luby S. 2010. Influenza is a major contributor to childhood pneumonia in a tropical developing country. Pediatr Infect Dis J 29:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple PJ, Harris W. 1966. Biophysical studies of a rhinovirus: Ultracentrifugation and electron microscopy. Nature 209:790–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessio DJ, Peterson JA, Dick CR, Dick EC. 1976. Transmission of experimental rhinovirus colds in volunteer married couples. J Infect Dis 133:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney JM Jr., Moskalski PB, Hendley JO. 1978. Hand-to-hand transmission of rhinovirus colds. Ann Intern Med 88:463–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendley JO, Gwaltney JM Jr., 1988. Mechanisms of transmission of rhinovirus infections. Epidemiol Rev 10:243–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendley JO, Wenzel RP, Gwaltney JM Jr., 1973. Transmission of rhinovirus colds by self-inoculation. New Engl J Med 288: 1361–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loens K, Goossens H, de Laat C, Foolen H, Oudshoorn P, Pattyn S, Sillekens P, Ieven M. 2006. Detection of rhinoviruses by tissue culture and two independent amplification techniques, nucleic acid sequence-based amplification and reverse transcription-PCR, in children with acute respiratory infections during a winter season. J Clin Microbiol 44:166–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Holloway B, Dare RK, Kuypers J, Yagi S, Williams JV, Hall CB, Erdman DD. 2008. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for comprehensive detection of human rhinoviruses. J Clin Microbiol 46:533–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Feikin DR, Painter J, Billhimer W, Altaf A, Hoekstra RM. 2005. Effect of handwashing on child health: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 366:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Billhimer W, Hoekstra RM. 2007. Field trial of a low cost method to evaluate hand cleanliness. Trop Med Int Health 12:765–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby SP, Kadir MA, Yushuf Sharker MA, Yeasmin F, Unicomb L, Sirajul Islam M. 2010. A community-randomised controlled trial promoting waterless hand sanitizer and handwashing with soap, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Trop Med Int Health 15: 1508–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering AJ, Davis J, Walters SP, Horak HM, Keymer DP, Mushi D, Strickfaden R, Chynoweth JS, Liu J, Blum A, Rogers K, Boehm AB. 2010. Hands, water, and health: Fecal contamination in Tanzanian communities with improved, non-networked water supplies. Environ Sci Technol 44:3267–3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabie T, Curtis V. 2006. Handwashing and risk of respiratory infections: A quantitative systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 11:258–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SE. 1975. An investigation of the possible transmission of Rhinovirus colds through indirect contact. J Hyg (Lond) 75: 249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talaat M, Afifi S, Dueger E, El-Ashry N, Marfin A, Kandeel A, Mohareb E, El-Sayed N. 2011. Effects of hand hygiene campaigns on incidence of laboratory-confirmed influenza and absenteeism in schoolchildren, Cairo, Egypt. Emerg Infect Dis 17: 619–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RB, Fuls JL, Rodgers ND, Goldfarb HB, Lockhart LK, Aust LB. 2012. A randomized trial of the efficacy of hand disinfection for prevention of rhinovirus infection. Clin Infect Dis 54: 1422–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kraaij MG, van Elden LJ, van Loon AM, Hendriksen KA, Laterveer L, Dekker AW, Nijhuis M. 2005. Frequent detection of respiratory viruses in adult recipients of stem cell transplants with the use of real-time polymerase chain reaction, compared with viral culture. Clin Infect Dis 40:662–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C, Kolble R, Carlson R, Lipson N, Dolan M, Ali Y, Cline M. 2003. The effect of hand hygiene on illness rate among students in university residence halls. Am J Infect Control 31: 364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]