Abstract

Background

Healthcare workers are at risk of acquiring hepatitis B and C virus infections through patients’ blood and bodily fluids exposure. So far, there is no pooled data that shows the prevalence of HBV and HCV among health care workers in Africa. This study aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of hepatitis B and C infections among health care workers in Africa.

Methods

Studies reporting the prevalence of HBV and HCV were identified from major databases and gray literature. PubMed, CINAHL, POPLINE, ScienceDirect, African Journals Online (AJOL), and Google Scholar were systematically searched to identify relevant studies. A random-effect model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of hepatitis B and C among health care workers in Africa. The heterogeneity of studies was assessed using Cochran Q statistics and I2 tests. Publication bias was assessed using Begg’s tests.

Result

In total, 1885 articles were retrieved, and 44 studies met the inclusion criteria and included in the final analysis. A total of 17,510 healthcare workers were included. The pooled prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in Africa is estimated to be 6.81% (95% CI 5.67–7.95) with a significant level of heterogeneity (I2 = 91.6%; p < 0.001). While the pooled prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection using the random-effects model was 5.58% (95% CI 3.55–7.61) with a significant level of heterogeneity (I2 = 95.1%; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Overall, one in fifteen and more than one in twenty healthcare workers were infected by HBV and HCV, respectively. The high burden of HBV and HCV infections remains a significant problem among healthcare workers in Africa.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12199-021-00983-9.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, Health care workers, Africa

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus and hepatitis C virus ( HCV) is an RNA virus [1]. Both HBV and HCV are transmitted by parenteral or mucosal exposure to infected blood and body fluids [1, 2]. Hepatitis B and C viruses are the most common causes of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma resulting in high morbidity and mortality all over the world [3, 4]. Hepatitis B virus is more contagious [2] and HCV is a predominant cause of chronic hepatitis [5].

About 350 million people are chronically infected with HBV [6], and 150 million people have chronic hepatitis C virus infection [7]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 14 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis B, and nine million people are chronically infected with hepatitis C in the European region in 2011 [8]. The majority of HBV and HCV infected cases are living in developing countries of sub-Saharan Africa [6]. Globally, HBV and HCV together accounted for an estimated 1.34 million deaths in the year 2015 [9] and in 2013 viral hepatitis infection was the seventh foremost cause of global mortality [10].

The transmission risk of viral hepatitis among health care workers (HCWs) is of great concern. The risk of acquiring hepatitis B virus by HCWs is four times greater than that of the general population [11, 12]. Healthcare workers are usually infected by HBV and HCV via occupational exposure to blood and bodily fluids [11, 13–15]. The circumstance is awful in Africa and Asia where 90% of worldwide hepatitis infections occur [16, 17]. In developing countries, 40–60% of HBV infections in HCWs were attributed to professional hazards [18]. Health care workers are vulnerable to contaminated sharp injuries which constitute a major source of hepatitis B infection, with an estimated 66,000 cases and 261 deaths annually in developing countries [19, 20]. Further, about half of African HCWs are occupationally exposed to blood and body fluids [21, 22]. The evidence available suggests that many HCWs in Africa are at higher risk of hepatitis B infection [23].

Understanding the relative contribution of HBV and HCV to liver disease burden is important for setting public health priorities and guiding prevention programs [24]. In spite of recommendations on hepatitis B vaccination, the immunization rates among health professionals have remained consistently low in African countries [3]. A meta-analysis conducted in 2018 also reported that only a quarter of African HCWs were fully vaccinated against hepatitis B virus [23].

So far, different studies have been conducted in Africa about the prevalence of HBV and HCV infections among HCWs, but the finding was inconsistent on HBV [25–57] and HVC [58–73], and the pooled prevalence is still uncertain. For instance, the prevalence of HBV was 1.4% in Egypt [33], 2.4% in Ethiopia [29], 17.8% in Senegal [54], and 25.7% in Nigeria [55], while the prevalence of HCV was 0.4% in Ethiopia [60], 1.3 in Rwanda [65], and 16.7% in Egypt [58]. Up to date, no pooled data estimate shows the prevalence of HBV and HCV among HCWs in Africa. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of hepatitis B and C infections among HCWs in Africa.

Methods

Study design and reporting

The protocol of this study was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (ID number CRD42021230905). A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of HBV and HCV among HCWs in Africa. This review and meta-analysis were conducted according to the guideline of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Supplementary file 1).

Eligibility criteria

Studies conducted in Africa that have reported the prevalence of hepatitis B or/and hepatitis C and fulfilled the following criteria were included.

Population. Healthcare works (HCWs) with direct contact to patients

Study designs. Observational studies reporting the prevalence of hepatitis B or/and hepatitis C were eligible for this systematic review and meta-analysis

Language. Articles published in English were considered.

Publication status. Both published and unpublished articles were considered.

Year of publication. All publications reported up to December 31, 2020, were considered.

Exclusion criteria. Studies that reported hepatitis B prevalence but do not have a separate outcome for HBsAg

Operational definition

Healthcare workers are referred to as full-time employees working in a healthcare setting whose activities involve direct contact with patients. Hence, we incorporated studies, which have involved physicians, nurses, and laboratory technicians mainly.

Outcome of interests and measurement

Prevalence hepatitis B and C virus infection were the outcome of interests. The prevalence of HBV was calculated from primary studies by dividing the number of HCWs tested for HBsAg and reported as positive to the total number of health care workers multiplied by 100. Similarly, the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection was calculated by dividing the number of HCWs tested for serum HCV antibody, and reported positive to the total number of health care workers multiplied by 100.

Search strategy

A systematic search of works of literature was conducted by the authors to identify all relevant primary studies. Both published and unpublished articles on the prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections in Africa were identified through a literature search. The databases used to search for studies were PubMed, Science Direct, CINAHL, Popline, Cochrane Library, and African Journals Online (AJOL) and gray literature was searched on Google and Google Scholar until December 31, 2020. The following key search terms and Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] were used “prevalence” OR “magnitude” AND “hepatitis B” OR “hepatitis C” AND “health care workers” OR “health professionals” AND “Africa [MeSH]” were used separately or in combination with the Boolean operator’s terms “AND” and “OR” (Supplementary file 2). In addition, the reference lists of the retrieved studies were also scanned to access additional articles and screened against our eligibility criteria.

Data Extraction

In this review, all the searched articles were exported into the EndNote version X8 software, and subsequently, the duplicate articles were removed. Screening of retrieved articles titles, abstracts, and full-text quality were conducted independently by two review authors (DA and BS) based on the eligibility criteria. Any disagreement between the two review authors was resolved by consensus through discussion. Afterward, full-text articles were retrieved and appraised to approve eligibility. Finally, the screened articles were compiled together by the two investigators. Data were extracted using a data extraction format in Microsoft Office Excel software. The data extraction tool consists of the name of the author(s), year of publication, country and sub-region, study design, sample size, and prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies in meta-analysis on prevalence of hepatitis B and C in Africa

| Author name | Year of publication | Country | Study design | Sample size | Prevalence of HBV | Prevalence of HCV | Prevalence of HBV in nurses | Prevalence of HBV in laboratory technician | Prevalence of HBV in physician |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desalegn et al. [27] | 2013 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 254 | 2.4 | 4 | 3.8 | ||

| Ziraba et al. [53] | 2010 | Uganda | Cross-sectional | 370 | 8.1 | 8.61 | 18.18 | 3.8 | |

| Mueller et al. [51] | 2016 | Tanzania | Cross-sectional | 598 | 7 | ||||

| Nail et al. [50] | 2008 | Sudan | Cross-sectional | 211 | 2.3 | 3.1 | |||

| Abiola et al. [25] | 2016 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 134 | 1.5 | 1.15 | 2.23 | ||

| Abdelwahab et al. [58] | 2012 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | 842 | 1.5 | 16.7 | |||

| Braka et al. [28] | 2006 | Uganda | Cross-sectional | 311 | 9 | 10.58 | 11.11 | 2.44 | |

| Djeriri et al. [31] | 2008 | Morocco | Cross-sectional | 285 | 5 | 1.5 | 1.85 | ||

| Ngekeng et al. [48] | 2018 | Cameroon | Cross-sectional | 281 | 5 | ||||

| Elmaghloub et al. [33] | 2017 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | 564 | 1.4 | ||||

| Elmukashfi et al. [34] | 2012 | Sudan | Cross-sectional | 843 | 6 | ||||

| Elduma and Saeed [36] | 2006 | Sudan | Cross-sectional | 245 | 4.9 | ||||

| Fritzsche et al. [59] | 2015 | Cameroon | Cross-sectional | 237 | 6.3 | 1.7 | 7.29 | 2.7 | 6.25 |

| Gebremariam et al. [38] | 2018 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 332 | 4.52 | 4.3 | 4.44 | 5 | |

| Hebo et al. [60] | 2019 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 240 | 2.5 | 0.4 | |||

| Mafopa et al. [62] | 2019 | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional | 81 | 4.9 | 2.5 | |||

| Alese et al. [26] | 2016 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 187 | 1.1 | ||||

| Munier et al. [63] | 2013 | Egypt | Cohort | 597 | 7.3 | 7.2 | |||

| Kisangau et al. [57] | 2018 | Kenya | Cross-sectional | 295 | 4.5 | ||||

| Jean-Baptiste et al. [61] | 2018 | Ivory cost | Cross-sectional | 632 | 8.4 | 1.4 | 19.48 | 28 | 38.14 |

| Souly et al. [64] | 2016 | Moroccoo | Cross-sectional | 1189 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 4.03 | 3.45 | 2.7 |

| Orji et al. [47] | 2020 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 236 | 2.1 | ||||

| Yizengaw et al. [43] | 2018 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 268 | 2.6 | 1.87 | 6.45 | ||

| Ndako et al. [49] | 2014 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 188 | 17 | 13.4 | 12.9 | 21.43 | |

| Elikwu et al. [32] | 2016 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 100 | 7 | 7.02 | 5.88 | ||

| Geberemicheal et al. [37] | 2013 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 110 | 7.3 | ||||

| Shao et al. [46] | 2018 | Tanzania | Cross-sectional | 442 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 10.81 | 5.38 | |

| Sondlane et al. [45] | 2016 | South Africa | Cross-sectional | 314 | 2.9 | ||||

| Tatsilong et al. [44] | 2016 | Cameroon | Cross-sectional | 100 | 11 | 10.2 | 25 | ||

| Kateera et al. [65] | 2014 | Rwanda | Cross-sectional | 378 | 2.9 | 1.3 | |||

| Elbahrawy et al. [66] | 2017 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | 564 | 8.7 | ||||

| Akazong et al. [27] | 2020 | Cameroon | Cross-sectional | 338 | 10.6 | 12.5 | 8.89 | 5.88 | |

| Amiwero et al. [67] | 2017 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 248 | 11.3 | 2.4 | 13.04 | 11.76 | |

| Daw et al. [30] | 2000 | Libya | Cross-sectional | 459 | 4 | ||||

| Romieu et al. [54] | 1989 | Senegal | Cross-sectional | 775 | 17.8 | ||||

| Qin et al. [52] | 2018 | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional | 211 | 10 | ||||

| Elzouki et al. [35] | 2014 | Libya | Cohort | 601 | 1.8 | 2.41 | 0.91 | 0.74 | |

| Ndongo et al. [56] | 2016 | Cameroon | Cross-sectional | 1790 | 8.7 | ||||

| Vardas et al. [68] | 2002 | South Africa | Cross-sectional | 399 | 1.8 | ||||

| Lungosi et al. [41] | 2018 | DR Congo | Cross-sectional | 97 | 18.6 | ||||

| Massaquoi et al. [39] | 2018 | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional | 447 | 8.7 | ||||

| Mbaawuaga et al. [40] | 2019 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 221 | 10.6 | 11.63 | |||

| Sani et al. [69] | 2011 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 100 | 19 | 5 | |||

| Zayet et al. [72] | 2015 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | 215 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 32 | 14.29 | |

| Kefenie et al. [42] | 1989 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 432 | 9.2 | 8.82 | 6.45 | ||

| El-Sokkary et al. [70] | 2017 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | 69 | 40.6 | ||||

| Belo et al. [55] | 2000 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 167 | 25.7 | ||||

| Gyang et al. [73] | 2016 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 155 | 8.5 | 6.5 | 2.74 | 3.13 |

Risk of bias assessment

The qualities of the included studies were assessed and the risks for biases were refereed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality assessment tool for the prevalence studies [74]. Two reviewers (DA and BS) assess the quality of included studies independently and the discrepancy between the two review authors was resolved by reaching a consensus through discussion. The assessment tool consists of nine parameters: (1) appropriate sampling frame, (2) proper sampling technique, (3) adequate sample size, (4) study subject and setting description, (5) sufficient data analysis, (6) use of valid methods for the identified conditions, (7) valid measurement for all participants, (8) using appropriate statistical analysis, and (9) adequate response rate [74]. Failure to satisfy each parameter was scored as 1 if not 0. When the information provided was not adequate to assist in making a judgment for a specific item, we agreed to grade that item as 1 (failure to satisfy a specific item). The risks for biases were classified as either low (total score, 0 to 2), moderate (total score, 3 or 4), or high (total score, 5 to 9) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk bias assessment of individual studies included for meta-analysis on prevalence of hepatitis B and C in Africa

| Wow | Year of publication | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Total score | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desalegn et al. [29] | 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | Moderate |

| Ziraba et al. [53] | 2010 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low |

| Mueller et al. [51] | 2016 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Nail et al. [50] | 2008 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | High |

| Abdelwahab et al. [58] | 2012 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | High |

| Braka et al. [28] | 2006 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| Djeriri et al. [31] | 2008 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Low |

| Ngekeng et al. [48] | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Moderate |

| Elmaghloub et al. [33] | 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Moderate |

| Elmukashfi et al. [34] | 2012 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Moderate |

| Elduma and Saeed [36] | 2006 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Moderate |

| Fritzsche et al. [59] | 2015 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | High |

| Gebremariam et al. [38] | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Munier et al. [63] | 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Moderate |

| Kisangau et al. [57] | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| Jean-Baptiste et al. [61] | 2018 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | Moderate |

| Souly et al. [64] | 2016 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Moderate |

| Orji et al. [47] | 2020 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Yizengaw et al. [43] | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low |

| Ndako et al. [49] | 2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | Moderate |

| Elikwu et al. [32] | 2016 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | Moderate |

| Geberemicheal et al. [37] | 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| Shao et al. [46] | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| Sondlane et al. [45] | 2016 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Tatsilong et al. [44] | 2016 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| Kateera et al. [65] | 2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| Elbahrawy et al. [66] | 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| Akazong et al. [27] | 2020 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Amiwero et al. [67] | 2017 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | Low |

| Daw et al. [30] | 2000 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Moderate |

| Romieu et al. [54] | 1989 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | High |

| Qin et al. [52] | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Elzouki et al. [35] | 2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Ndongo et al. [56] | 2016 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Vardas et al. [68] | 2002 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | Moderate |

| Lungosi et al. [41] | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| Massaquoi et al. [39] | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Mbaawuaga et al. [40] | 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| Sani et al. [69] | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | High |

| Zayet et al. [72] | 2015 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | High |

| Kefenie et al. [42] | 1989 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Low |

| El-Sokkary et al. [70] | 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Low |

| Belo et al. [55] | 2000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | Moderate |

| Gyang et al. [73] | 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Low |

The risk of bias was classified as either low (total score, 0 to 2), moderate (total score, 3 or 4), or high (total score, 5 to 9)

Q1 = Was the sample frame appropriate to address the target population?

Q2 = Were study participants sampled in an appropriate way?

Q3 = Was the sample size adequate?

Q4 = Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail?

Q5 = Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample?

Q6 = Were valid methods used for the identification of the condition?

Q7 = Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants?

Q8 = Was there appropriate statistical analysis?

Q9 = Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately?

Statistical methods and analysis

The extracted data were imported into STATA version 14 software for statistical analysis. The heterogeneity among all included studies was assessed by I2 statistics and Cochran Q test. In this meta-analysis, the tests indicate that the presence of significant heterogeneity among included studies (I2 = 91.6, P-value < 0.001). Thus, a random-effects model was used to analyze the data. Pooled prevalence along their corresponding 95% CI was presented using a forest plot. Sub-group analyses for the prevalence of hepatitis B and C were performed by sub-regions of Africa, sample size, year of publication, and professions of HCWs.

Publication bias

In this meta-analysis, the presence of publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and Begg’s tests at a significance level of less than 0.05.

Sensitivity analysis

To identify the source of heterogeneity, a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was employed.

Results

Description of included studies

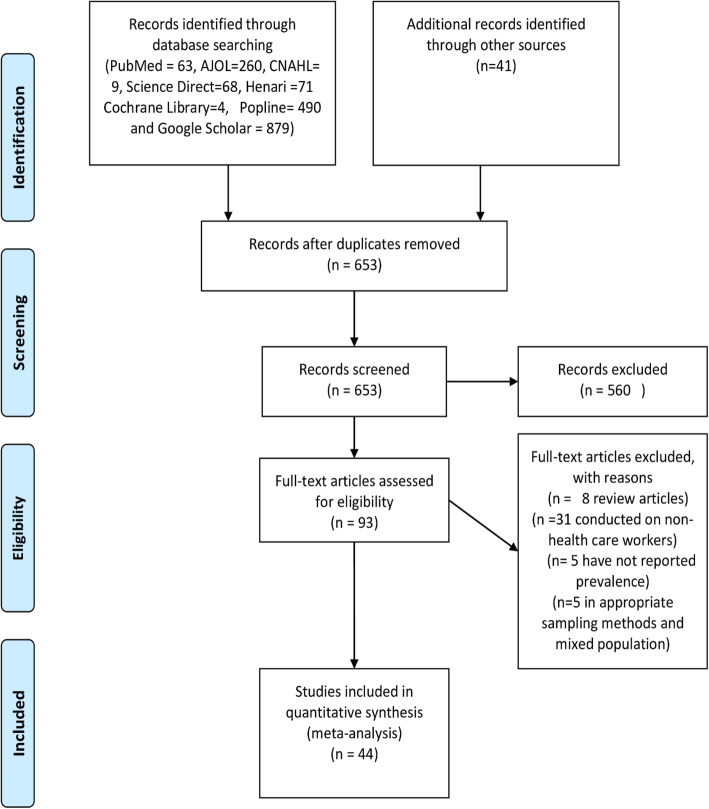

About 1885 studies were retrieved from initial electronic searches using international databases and google search. The database included PubMed (n = 63), ScienceDirect (n = 68), Hinari (n = 71), Google Scholar (n = 879), Cochrane Library (n = 4), AJOL (n = 260), CINAHL (n = 9), POPLINE (n = 490), and the remaining (n = 41) studies were identified through manual search. Of these, 1332 duplicates were removed, the remaining 553 articles were screened by title and abstract, and 460 articles were excluded after reading their titles and abstracts. Ninety-three full-text articles remained and were further assessed for their eligibility. Finally, based on the pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 44 articles were included in the meta-analysis and data were extracted for the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of systemic review and meta-analysis on prevalence of hepatitis B and C among health care workers in Africa, 1989–2021

Characteristics of the included studies

Of 44 articles included in this review and meta-analyses, 5 were conducted in Ethiopia, 2 in Uganda, 2 in Tanzania, 3 in Sudan, 8 in Nigeria, 6 in Egypt, 5 in Cameron, 2 in Morocco, 2 in Sierra Leone, 2 in Rwanda, 1 in Kenya, 1 in Côte d’Ivoire, 2 in south Africa, 1 in Senegal, 1 in DR Congo, and 2 in Libya (Table 1).

A total number of 17,510 HCWs participated in this study. The lowest sample size was reported from Egypt (n = 69) and the highest was from Cameron (n = 1790). Among the included studies, 31 of them reported the prevalence of HBV, 3 of them presented the prevalence of HCV, and 10 studies reported the prevalence of both HBV and HCV (Table 1).

The latest article was published in 2020, and the earliest study was concluded in 1989. The prevalence of hepatitis B among African HCWs ranged from 1.4% in Egypt to 25.7% in Nigeria. The prevalence of hepatitis C varied from 0.4% in Ethiopia to 40.6% in Egypt (Table 1).

Socioeconomic status of African countries included in this meta-analysis

Out of sixteen countries included in this meta-analysis, 6 (37.50%) of them have gross national income (GNI) per capita less than $1036, 8 (50%) of them have GNI per capita between $1036 to 4036, and 2 (12.50%) of them have GNI per capita above $4036. In terms of governmental health care expenditure, about 9 (56.25%) of included countries have less than 30% health expenditure from domestic government funding and 2 (12.50%) have higher than 50% of health expenditure from domestic government funding. In addition, out of the sixteen countries, 7 (43.75%) of them have universal health coverage less than 50% and one country has universal health coverage greater than 60% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Socioeconomic characteristics of African countries included in meta-analysis for prevalence of HBV and HCV in Africa

| Countries | GNI per capita (US$) (word bank.org 2019) | Governmental health care expenditure (%) (africanhealthcarestats.org) | Universal health coverage (%) (healthdata.org) | Classification by World Bank (world bank data.org 2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria | 2030 | 13 | 38.3 | Low-middle income |

| Ethiopia | 850 | 28 | 46.5 | Low income |

| Sudan | 590 | 19 | 51.8 | Low income |

| Egypt | 2690 | 29 | 54.8 | Low-middle income |

| DR Congo | 530 | 12 | 45.2 | Low income |

| Sierra Leone | 540 | 11 | 42.1 | Low income |

| Libya | 7640 | 63 | 66.3 | Upper-middle income |

| Cameron | 1500 | 13 | 42.3 | Low-middle income |

| Senegal | 1460 | 33 | 49.6 | Low-middle income |

| Rwanda | 830 | 34 | 59.4 | Low income |

| South Africa | 6040 | 54 | 59.7 | Upper-middle income |

| Kenya | 1750 | 36 | 51.6 | Low-middle income |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 2290 | 26 | 43.0 | Low-middle income |

| Tanzania | 1080 | 41 | 55.2 | Low-middle income |

| Uganda | 780 | 17 | 52.7 | Low income |

| Morocco | 3190 | 47 | 58.0 | Low-middle income |

Prevalence of hepatitis B and C infection among health HCWs in Africa

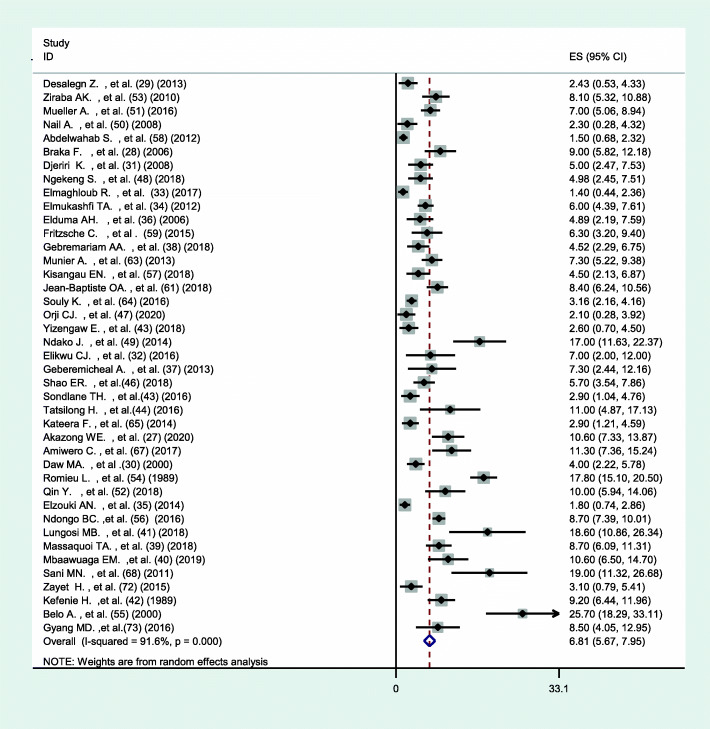

The pooled prevalence of hepatitis B among HCWs in Africa using the random-effect model was estimated to be 6.81% (95% CI 5.67–7.92) with a significant level of heterogeneity (I2 = 91.6%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). While the pooled prevalence of hepatitis C using the random-effects model was 5.58% (95% CI 3.55–7.61) with a significant level of heterogeneity (I2 = 95.1%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of hepatitis B among HCWs in Africa

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of hepatitis C among HCWs in Africa

Sub-group analysis

To identify the possible source of heterogeneity, sub-group analysis was conducted by sub-regions of Africa, sample size, year of publication, and professions of HCWs.

The prevalence of hepatitis B was found to be highest in Western Africa 11.67% (95% CI 8.21–15.17), and the lowest was reported from Northern Africa 3.50% (95% CI 2.41–4.58). Heterogeneity has been shown to vary from I2 = 72 to 91.6% on this estimate (Table 4). This meta-analysis also found that the prevalence of hepatitis C infection varied between different sub-regions of Africa, and the highest prevalence was found in Northern Africa, 11.23% (95% CI 5.45–17.01), with significant heterogeneity I2 = 97.8% and the lowest prevalence was identified in Eastern Africa 1.32% (95% CI 0.16–2.47) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Showing sub-group analysis of HBV prevalence by sample size, year of publication, regions of Africa, and HCWs professions in Africa

| Prevalence of HBsAg | 95% Confidence interval | Heterogeneity (I2%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-group analysis by sample size | ||||

| 1. < 101 | 11.33 | 6.17–16.50 | 76.0 | P = 0.002 |

| 2. 101–384 | 5.57 | 4.31–6.83 | 85.7 | P < 0.001 |

| 3. 385–1000 | 6.42 | 4.24–8.61 | 95.1 | P < 0.001 |

| 4. > 1000 | 5.91 | 0.48–11.54 | 97.6 | P < 0.001 |

| Sub-group analysis by year of publication | ||||

| 1. < 2001 | 12.32 | 3.32–21.39 | 97.1 | P < 0.001 |

| 2. 2001–2010 | 5.79 | 3.43–8.16 | 88.3 | P < 0.001 |

| 3. 2011–2021 | 5.71 | 4.68–6.74 | 87.7 | P < 0.001 |

| Sub-group analysis by regions of Africa | ||||

| 1. North Africa | 3.50 | 2.41–4.58 | 83.8 | P < 0.001 |

| 2. East Africa | 5.51 | 4.03–6.99 | 77.5 | P < 0.001 |

| 3. Middle Africa | 8.77 | 6.32–11.21 | 72.2 | P = 0.003 |

| 4. Western Africa | 11.69 | 8.21–15.17 | 91.8 | P < 0.001 |

| 5. Southern Africa | 2.90 | 1.04–4.99 | - | - |

| Sub-group analysis by professions | ||||

| 1. Physician | 6.30 | 3.54–9.07 | 81.8 | P < 0.001 |

| 2. Nurses | 6.31 | 4.23–8.40 | 84.5 | P < 0.001 |

| 3. Laboratory staff | 7.32 | 3.77–10.88 | 59.4 | P = 0.003 |

Table 5.

Showing sub-group analysis of HCV prevalence by sample size, year of publication, and sub-regions of African countries

| Prevalence of HCV | 95% confidence interval | Heterogeneity (I2%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-group analysis by sample size | ||||

| 1. < 101 | 14.28 | 1.16–27.40 | 94.8 | P = 0.001 |

| 2. 101–384 | 1.19 | 0.54–1.84 | 21.8 | P = 0.269 |

| 3. 385–1000 | 7.04 | 2.46–11.62 | 97.6 | P < 0.001 |

| 4. > 1000 | 1.26 | 0.67–1.85 | - | - |

| Sub-group analysis by year of publication | ||||

| 1. < 2011 | 3.74 | 2.24–5.23 | 94.2 | P < 0.001 |

| 2. 2011–2021 | 17.94 | 17.94–24.75 | 95.7 | P < 0.001 |

| Sub-group analysis by regions of Africa | ||||

| 1. North Africa | 11.23 | 5.76–17.02 | 97.8 | P < 0.001 |

| 2. East Africa | 1.32 | 0.17–2.48 | - | - |

| 3. Middle Africa | 1.69 | 0.004–3.33 | - | - |

| 4. Western Africa | 3.04 | 1.08–4.99 | 65.5 | P < 0.033 |

| 5. South Africa | 2.90 | 1.04–4.78 | - | - |

The analysis of sub-group by sample size identified that highest prevalence of HBV among studies with sample size < 101, 11.33% (95% CI 6.17–16.50), and lowest prevalence was identified among sample size between 101 and 384, 5.57 (95% CI 4.31–6.83) (Table 4). Similarly, the highest prevalence of HCV among studies with sample size < 101, 14.28% (95% CI 1.16–27.40) and lowest prevalence was identified among sample size between 101 and 384, 1.19 (95% CI 0.54–1.84) (Table 5). The heterogeneity was shown to vary from 76.0 to 97.6% for HBV and from 21.8 to 97.6% for HCV.

In the sub-group analysis of studies by year of publication, highest prevalence of HBV was revealed by studies conducted before 2001, 12.33 (95% CI 3.32–21.39), and lowest among studies conducted between 2011 and 2021, 5.71 (95% CI 4.68–6.74) (Table 4). For HCV, lowest prevalence was revealed by studies conducted before 2001, 3.74 (95% CI 2.24–5.23), and highest among studies conducted between 2011 and 2021, 17.94 (95% CI 17.94–24.75) (Table 5).

The sub-group was also conducted by profession of HCWs for HBV, in which laboratory staffs were identified to have relatively highest prevalence, 7.32 (95% CI 3.77–10.88), and lowest prevalence were identified among physician 6.30 (95% CI 3.54–9.07). The heterogeneity was shown to vary from 59.7% among laboratory staff and to 84.4% among nurses (Table 4).

Sensitivity analysis

To detect the source of heterogeneity, a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was employed. The result of sensitivity analysis using the random-effects model revealed that there was no single study that influenced the overall prevalence of hepatitis B and C infection among HCWs (Supplementary file 3).

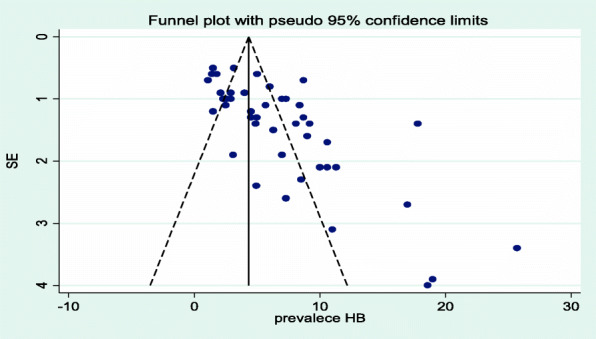

The publication biases

The presence of publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and Begg’s tests at a significance level of less than 0.05. The findings revealed that publication bias was significant for the studies on the prevalence of hepatitis B (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Similarly, it was statistically significant (p = 0.001) for the prevalence of hepatitis C among health care workers. The trim and fill analysis added twenty-nine studies and the pooled prevalence of hepatitis B in Africa varied to 9.1% (95% CI 7.1–11.7), while nine studies were added, and pooled prevalence of hepatitis C in Africa varied to 1.32 (95% CI 0.92–1.55).

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot showing publication bias of studies included for the prevalence of hepatitis B among health care workers in Africa

Meta-regression

In a meta-regression analysis, the publication year and sample size were not significant sources of heterogeneity for the prevalence of hepatitis B. In this study, no significant relationship was identified between the prevalence of hepatitis B and the publication year (p-value = 0.35) and sample size (p-value = 0.46). Likewise, there was no significant association between the prevalence of hepatitis C and the publication year (p-value = 0.67) and sample size (p-value = 0.84).

Discussion

This is the first review and meta-analysis conducted in Africa on the prevalence of hepatitis B and C among HCWs. The pooled prevalence of hepatitis B and C among HCWs in Africa was 6.81% and 5.58%, respectively. The highest and lowest prevalence of HBV was identified in the western and northern parts of Africa, respectively.

The pooled prevalence of HBV among HCWs in Africa was not shown to have a significant difference from the general population (6.1%) [75]. The current finding was almost similar to a review conducted in Thailand which has revealed the pooled prevalence of hepatitis B among HCWs to be 5.2% [76]. The present prevalence of HBV identified by our analysis is higher than a review conducted in 2017 in Middle Eastern countries [77] and a study conducted in Turkey which has revealed hepatitis B prevalence among HCWs to be 3% [78]. It was also found to be much higher than the pooled prevalence of hepatitis B among HCWs reported in Iranians (0.4%) [79] and Brazilian 0.8% [80]. This may be due to the higher vaccination status of Iranians against hepatitis B [81] and the low vaccination status of African HCWs against hepatitis B [23]. Further, in developing countries, more than half of HBV infections in HCWs were attributable to percutaneous occupational exposure [21, 82].

The current review has revealed the prevalence of HCV among HCWs in Africa was nearly two times higher when compared with the prevalence in the general population (2.9%) [83]. This difference may be due to HCWs vulnerability towards occupational blood and body flood exposure than the general population. This finding is significantly higher when compared with the pooled prevalence reported in Germany (0.04%) [84], Turkey (0.3%) [78], and Scotland (0.28%) [85]. The possible reason for the discrepancy may be due to higher frequencies of healthcare associated infection in Africa than developed countries [86].

In this study, we found a variation in hepatitis B prevalence among HCWs across African regions. The sub-group analysis has revealed that the highest and lowest prevalence of hepatitis B among HCWs was found in the western and northern parts of Africa, respectively. The difference can be explained by the vaccination status of HCWs in the region. In the northern part of Africa, about 62% of HCWs have fully vaccinated against hepatitis B [23]. While only 30% of HCWs have been fully vaccinated in the western part of Africa [23]. The highest prevalence of HCV was identified in the northern part of Africa. The difference might be due to the higher occupational exposure rate of blood and body fluid in the northern part of Africa [21].

The strengths of this review and meta-analysis were comprehensive search through all reachable databases and rigorously following the PRISMA statement in all processes of conducting this systematic and meta-analysis.

This meta-analysis was reported with the following limitations. First, some studies included in this review had small sample sizes (n < 100 HCWs) which may affect the estimated prevalence of HBV and HCV in HCWs. As revealed by the sub-group analysis studies with a small sample size have shown higher prevalence of HBV (Table 4) and HCV (Table 5) among HCWs in Africa. This is supported by the fact that a small sample size will have a wider confidence interval and overestimate the magnitude of the association [87]. In addition, studies with a wide confidence interval are related to the low precision of the finding [88]. Second, there is a significant publication bias of included studies. Publication bias is bias caused by unpublished studies and usually researches with negative results less likely to be published [89]. Unpublished articles are not easily available in areas where there are no repositories. This is the most common problem in Africa since most research institutes and universities do not have repositories available online [90].

Conclusion

The prevalence of hepatitis B is more than one in fifteen HCWs in Africa. While about one in twenty HCWs are affected by the hepatitis C virus. This high prevalence shows that hepatitis B and C are still endemic among HCWs in Africa. To reduce the prevalence of HCV and HBV among HCWs it needs a new strategy that reduces occupational exposure to blood and body fluids. Including mandatory vaccination against hepatitis B is required for HCWs as they are among the risky groups in the community and reduction of occupational exposure by maintaining adequate personal protective equipment supported by regulations. In addition, continuous training on infection prevention procedures for all HCWs should be provided.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Additional file 2. Searched data base with search strategy.

Additional file 3: Table 1. Sensitivity analysis of prevalence of HBsAG among health care workers in Africa for each study being removed at a time, 1989-2020. Table 2. Sensitivity analysis of prevalence of anti – HCV among health care workers in Africa for each study being removed at a time, 1989-2020.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the authors of original articles who have responded timely to our queries through emails.

Authors’ contributions

DA: Conceptualize, study protocol, data extraction and analysis, and writing the original draft of the manuscript. DA, BS, and ZT conducted study design, literature review, and statistical analysis of the review. DA, BS, and ZT conducted a critical appraisal and data extraction. DA wrote the original draft of the manuscript. ZT, BS, and DA critically revised the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Nil

Availability of data and materials

The part of the data analyzed during this study is included in this manuscript. Other data will be available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Te HS, Jensen DM. Epidemiology of hepatitis B and C viruses: a global overview. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muvunyi CM, Harelimana JDD, Sebatunzi OR, Atmaprakash AC, Seruyange E, Masaisa F, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among healthcare workers at a tertiary hospital in Rwanda. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-4002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budak GG, Gülenç N, Özkan E, Bülbül R, et al. Seroprevalences of hepatitis B and hepatitis C among healthcare workers in Tire State Hospital. Dicle Med J. 2017;44(3):267–270. doi: 10.5798/dicletip.339008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westermann C, Peters C, Lisiak B, Lamberti M, Nienhaus A. The prevalence of hepatitis C among healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72(12):880–888. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-102879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alam S, Ahmad N, Khan M, Mustafa G, Al Mamun A, Mashud G. Hepatitis C virus infection among health care workers. J Bangladesh Coll Physicians Surg. 2007;25(3):126–9.

- 6.Ogoina D, Pondei K, Adetunji B, Chima G, Isichei C, Gidado S. Prevalence of hepatitis B vaccination among health care workers in Nigeria in 2011-12. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2014;5(1):51–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westermann C, Dulon M, Wendeler D, Nienhaus A. Hepatitis C among healthcare personnel: secondary data analyses of costs and trends for hepatitis C infections with occupational causes. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2016;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12995-016-0142-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatzakis A, Wait S, Bruix J, Buti M, Carballo M, Cavaleri M, Colombo M, Delarocque-Astagneau E, Dusheiko G, Esmat G, Esteban R, Goldberg D, Gore C, Lok ASF, Manns M, Marcellin P, Papatheodoridis G, Peterle A, Prati D, Piorkowsky N, Rizzetto M, Roudot-Thoraval F, Soriano V, Thomas HC, Thursz M, Valla D, van Damme P, Veldhuijzen IK, Wedemeyer H, Wiessing L, Zanetti AR, Janssen HLA. The state of hepatitis B and C in Europe: report from the hepatitis B and C summit conference. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishizaki A, Bouscaillou J, Luhmann N, Liu S, Chua R, Walsh N, et al. Survey of programmatic experiences and challenges in delivery of hepatitis B and C testing in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):130–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Aaron D, Nagu TJ, Rwegasha J, Komba E. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among healthcare workers at national hospital in Tanzania: how much, who and why? BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2893-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abebaw TA, Aderaw Z, Gebremichael B. Hepatitis B virus vaccination status and associated factors among health care workers in Shashemene Zonal Town, Shashemene, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2582-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadler SC. Hepatitis B virus infection and health care workers. Vaccine. 1990;8(1):24–28. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(90)90211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ssekamatte T, Mukama T, Kibira SPS, Ndejjo R, Bukenya JN, Kimoga ZPA, et al. Hepatitis B screening and vaccination status of healthcare providers in Wakiso district, Uganda. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abeje G, Azage M. Hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and vaccination status among health care workers of Bahir Dar City Administration, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0756-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nitin DS, Prashant, Nitin A, Prashant P, Kumar DH. Status of protection against hepatitis B infection among healthcare workers (HCW) in a tertiary healthcare center in India: results can’t be ignored! J Hematol Clin Res. 2017;2(1):001–005. doi: 10.29328/journal.jhcr.1001005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adenlewo OJ, Adeosun PO, Fatusi OA. Medical and dental students’ attitude and practice of prevention strategies against hepatitis B virus infection in a Nigerian university. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28(33):1–8. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.28.33.11662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziglam H, El-Hattab M, Shingheer N, Zorgani A, Elahmer O. Hepatitis B vaccination status among healthcare workers in a tertiary care hospital in Tripoli, Libya. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6(4):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kisic-Tepavcevic D, Kanazir M, Gazibara T, Maric G, Makismovic N, Loncarevic G, Pekmezovic T. Predictors of hepatitis B vaccination status in healthcare workers in Belgrade, Serbia, December 2015. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22(16):0–8. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.16.30515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas RJ, Fletcher GJ, Kirupakaran H, Chacko MP, Thenmozhi S, Eapen CE, Chandy G, Abraham P. Prevalence of non-responsiveness to an indigenous recombinant hepatitis B vaccine: a study among South Indian health care workers in a tertiary hospital. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33(1):S32–S36. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.150877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan FY, Ross AJ. Hepatitis B immunisation amongst doctors and laboratory personnel in Kwazulu-natal, South Africa. Afr J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. 2013;5(1):1–6. doi: 10.1071/HC13001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auta A, Adewuyi EO, Tor-Anyiin A, Aziz D, Ogbole E, Ogbonna BO, Adeloye D. Health-care workers’ occupational exposures to body fluids in 21 countries in Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(12):831–841. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.195735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahiledengle B, Tekalegn Y, Woldeyohannes D, Quisido BJE. Occupational exposures to blood and body fluids among healthcare workers in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-Analysis. Environ Health Prev Med. 2020;25(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12199-020-00897-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auta A, Adewuyi EO, Kureh GT, Onoviran N, Adeloye D. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among health-care workers in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2018;36(32):4851–4860. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJF, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45(4):529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abiola AHO, Agunbiade AB, Badmos KB, Lesi AO, Lawal AO, Alli QO. Prevalence of HBsAg, knowledge, and vaccination practice against viral hepatitis b infection among doctors and nurses in a secondary health care facility in Lagos state, south-western Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;23:1–10. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.160.8710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alese OO, Alese MO, Ohunakin A, Oluyide PO. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen and occupational risk factors among health care workers in Ekiti state, Nigeria. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(2):LC16–LC18. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/15936.7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akazong WE, Tume C, Njouom R, Ayong L, Fondoh V, Kuiate JR. Knowledge, attitude and prevalence of hepatitis B virus among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional, hospital-based study in Bamenda Health District, NWR, Cameroon. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braka F, Nanyunja M, Makumbi I, Mbabazi W, Kasasa S, Lewis RF. Hepatitis B infection among health workers in Uganda: evidence of the need for health worker protection. Vaccine. 2006;24(47–48):6930–6937. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desalegn Z, Selassie SG. Prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) among health professionals in public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Heal Dev. 2013;27(1):72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daw MA, Siala IM, Warfalli MM, Muftah MI. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus markers among hospital health care workers: analysis of certain potential risk factors. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(12):1157–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Djeriri K, Laurichesse H, Merle J l, Charof R, Abouyoub A, Fontana L, et al. Hepatitis B in Moroccan health care workers. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2008;58(6):419–424. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqn071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elikwu CJ, Shonekan O, Shobowale E, Nwadike V, Tayo B, Okangba C, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigenaemia among healthcare worker in a private Nigerian tertiary health institution. Int J Infect Control. 2016;12(2):1–6.

- 33.Elmaghloub R, Elbahrawy A, El Didamony G, Elwassief A, Saied Mohammad A-G, Alashker A, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype E infection among Egyptian health care workers. J Transl Intern Med. 2017;5(2):100–105. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2017-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elmukashfi TA, Elkhidir IM, Ibrahim OA, Bashir AA, Elkarim MAA. Hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in public teaching hospitals in Khartoum State, Sudan. Saf Sci. 2012;50(5):1215–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elzouki AN, Elgamay SM, Zorgani A, Elahmer O. Hepatitis B and C status among health care workers in the five main hospitals in eastern Libya. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7(6):534–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elduma AH, Saeed NS. Hepatitis B virus infection among staff in three hospitals in Khartoum, Sudan, 2006–07. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17(6):2011. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.6.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geberemicheal A, Gelaw A, Moges F, Dagnaw M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infections among health care workers at the Bulle Hora Woreda Governmental Health Institutions, Southern Oromia, Ethiopia. J Environ Occup Sci. 2013;2(1):9. doi: 10.5455/jeos.20130220105759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gebremariam AA, Tsegaye AT, Shiferaw YF, Reta M, Getaneh A. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and associated factors among mothers in Gondar, North-west Ethiopia: a population based study. Ethiop Med J. 2019;57(2):97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massaquoi TA, Burke RM, Yang G, Lakoh S, Sevalie S, Li B, et al. Cross sectional study of chronic hepatitis B prevalence among healthcare workers in an urban setting, Sierra Leone. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mbaawuaga EM, Hembah-hilekaan SK, Iroegbu CU, Ike AC. Hepatitis B virus and human immunodeficiency virus infections among health care workers in some health care centers in Benue State, Nigeria. 2019. pp. 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lungosi MB, Muzembo BA, Mbendi NC, Nkodila NA, Ngatu NR, Suzuki T, et al. Assessing the prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in a referral hospital in Kisantu, Congo DR: A pilot study. Ind Health. 2019;57(5):621–626. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2018-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kefenie H, Desta B, Abebe A. Prevalence of hepatitis B infection among hospital personnel in Addis Ababa (Ethiopia) Environ Prot. 1993;5(4):489–496. doi: 10.1007/BF00140142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yizengaw E, Getahun T, Geta M, Mulu W, Ashagrie M, Hailu D, et al. Sero-prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and associated factors among health care workers and medical waste handlers in primary hospitals of North-west Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):4–9. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tatsilong HOP, Noubiap JJN, Nansseu JRN, Aminde LN, Bigna JJR, Ndze VN, et al. Hepatitis B infection awareness, vaccine perceptions and uptake, and serological profile of a group of health care workers in Yaoundé, Cameroon. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sondlane TH, Mawela L, Razwiedani LL, Selabe SG, Lebelo RL, Rakgole JN, Mphahlele MJ, Dochez C, de Schryver A, Burnett RJ. High prevalence of active and occult hepatitis B virus infections in healthcare workers from two provinces of South Africa. Vaccine. 2016;34(33):3835–3839. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao ER, Mboya IB, Gunda DW, Ruhangisa FG, Temu EM, Nkwama ML, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and associated factors among healthcare workers in northern Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3376-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orji CJ, Chime OH, Ndibuagu EO. Vaccination status and prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among health-care workers in a tertiary health institution, Enugu State, Nigeria. Proc Singapore Healthc. 2020;29(2):119–125. doi: 10.1177/2010105820923681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ngekeng S, Chichom-Mefire A, Nde P, Nsagha D, Nkuigue A, Tiogouo K, Oben F, Ekotang P, Choukem S. Hepatitis B prevalence, knowledge and occupational factors among health care workers in Fako Division, South West Region Cameroon. Microbiol Res J Int. 2018;23(4):1–9. doi: 10.9734/MRJI/2018/40445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ndako J, Onwuliri E, Adelani-Akande T, Olaolu D, Dahunsi S, Udo U. Screening for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) among health care workers (HCW) in an urban community South-South Nigeria. Int J Biol Pharm Allied Sci. 2014;3(3):415–425. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nail A, Eltiganni S, Imam A. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C among health care workers in Omdurman, Sudan. Sudan JMS. 2008;3(3):201–205. doi: 10.4314/sjms.v3i3.38536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mueller A, Stoetter L, Kalluvya S, Stich A, Majinge C, Weissbrich B, Kasang C. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1129-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qin YL, Li B, Zhou YS, Zhang X, Li L, Song B, et al. Prevalence and associated knowledge of hepatitis B infection among healthcare workers in Freetown, Sierra Leone. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3235-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziraba AK, Bwogi J, Namale A, Wainaina CW, Mayanja-Kizza H. Sero-prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Romieu I, Sow I, Lu S, Laroque G, Prince-David M, Romet-Lemonne JL. Prevalence of hepatitis B markers among hospital workers in Senegal. J Med Virol. 1989;27(4):282–287. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890270405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Belo A. Prevalence of hepatitis b virus markers in surgeons in lagos, nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2000;77(5):283–285. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v77i5.46634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ndongo BC, Eteki L, Siedner M, Mbaye R, Chen J, Ntone R, et al. Prevalence and vaccination coverage of Hepatitis B among healthcare workers in Cameroon: a national seroprevalence survey. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(12):1582–1587. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kisangau EN, Awour A, Juma B, Odhiambo D, Muasya T, Kiio SN, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and uptake of hepatitis B vaccine among healthcare workers, Makueni County, Kenya 2017. J Public Health (United Kingdom) 2019;41(4):765–771. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdy186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abdelwahab S, Rewisha E, Hashem M, Sobhy M, Galal I, Allam WR, Mikhail N, Galal G, el-Tabbakh M, el-Kamary SS, Waked I, Strickland GT. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among Egyptian healthcare workers in a national liver diseases referral centre. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106(2):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fritzsche C, Becker F, Hemmer CJ, Riebold D, Klammt S, Hufert F, Akam W, Kinge TN, Reisinger EC. Hepatitis B and C: neglected diseases among health care workers in Cameroon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2013;107(3):158–164. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trs087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hebo HJ, Gemeda DH, Abdusemed KA. Hepatitis B and C Viral Infection: Prevalence, knowledge, attitude, practice, and occupational exposure among healthcare workers of Jimma University Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia. Sci World J. 2019:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Jean-Baptiste OA, Amadou K, Mamadou D, Fabrice A, Sroboua TA, N’guessan N. Predictive factors for viral B and C infection in health workers in a university hospital in Ivory Coast. Open J Gastroenterol. 2018;8(10):377–385. doi: 10.4236/ojgas.2018.810039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mafopa NG, Giovanetti M, Wadoum REG, Minutolo A, Yinda CK, Russo G, et al. Viral hepatitis B and C detection among Ebola survivors and health care workers in Makeni, Sierra Leone. J Biosci Med. 2020;8(10):18–32. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Munier A, Marzouk D, Abravanel F, El-Daly M, Taylor S, Mamdouh R, et al. Frequent transient hepatitis C viremia without seroconversion among healthcare workers in Cairo, Egypt. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):1–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Souly K, El Kadi MA, Elkamouni Y, Biougnach H, Kreit S, Zouhdi M. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus in health care personnel in Ibn Sina Hospital, Rabat, Morocco. Open J Med Microbiol. 2016;6(1):17–22. doi: 10.4236/ojmm.2016.61004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kateera F, Walker TD, Mutesa L, Mutabazi V, Musabeyesu E, Mukabatsinda C, et al. Hepatitis B and C seroprevalence among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Rwanda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;109(3):203–208. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elbahrawy A, Elwassief A, Abdallah AM, Kasem A, Mostafa S, Makboul K, Ali MS, Alashker A, Eliwa AM, Shahbah H, Othman MA, Morsy MH, Abdelbaseer MA, Abdelhafeez H. Hepatitis C virus exposure rate among health-care workers in rural Lower Egypt governorates. J Transl Intern Med. 2017;5(3):164–168. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2017-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amiwero C, Nelson EA, Yusuf M, Olaosebikan OF, Adeboye MA, Adamu UG, et al. Knowledge, awareness and prevalence of viral hepatitis among health care workers (HCWs) of the Federal Medical Centre Bida, Nigeria. J Med Res. 2017;3(3):114–120. doi: 10.31254/jmr.2017.3306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vardas E, Ross MH, Sharp G, McAnerney J, Sim J. Viral hepatitis in South African healthcare workers at increased risk of occupational exposure to blood-borne viruses. J Hosp Infect. 2002;50(1):6–12. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2001.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sani NM, Bitrus I, Sarki AM, Mujahid NS. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C among healthcare workers in Dutse Metropolis Jigawa State, Nigeria. bioRxiv. 2018. 10.1101/327940.

- 70.El-Sokkary RH, Tash RME, Meawed TE, El Seifi OS, Mortada EM. Detection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) among health care providers in an Egyptian university hospital: different diagnostic modalities. Infect Drug Resist. 2017;10:357–364. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S145844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abuojokh A. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viral infection among health care workers in Elmak Nimir University Hospital. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zayet H, AM EE-D. SM A. MR E-K Hepatitis B and C virus infection among health care workers in General Surgery Department, Assiut Univers Ity Hospitals. Egypt J Occup Med. 2015;39(1):85–104. doi: 10.21608/ejom.2015.813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gyang MD, Madaki AJK, Dankyau M, Toma BO, Danjuma SA, Gyang BA. Prevalence and correlates of hepatitis B and C seropositivity among health care workers in a semi urban setting in Northern central Nigeria. Highland Med Res J. 2016;16(2):75–9.

- 74.Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for prevalence studies. Checkl Prevalance Stud. 2016;7 Available from: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/critical-appraisal-tools/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Prevalence_Studies.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

- 75.Spearman CW, Afihene M, Ally R, Apica B, Awuku Y, Cunha L, Dusheiko G, Gogela N, Kassianides C, Kew M, Lam P, Lesi O, Lohouès-Kouacou MJ, Mbaye PS, Musabeyezu E, Musau B, Ojo O, Rwegasha J, Scholz B, Shewaye AB, Tzeuton C, Sonderup MW, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Association of sub-Saharan Africa (GHASSA) Hepatitis B in sub-Saharan Africa: strategies to achieve the 2030 elimination targets. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(12):900–909. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leroi C, Adam P, Khamduang W, Kawilapat S, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Ongwandee S, Jiamsiri S, Jourdain G. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Thailand: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;51:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davoudi-Kiakalayeh A, Mohammadi R, Pourfathollah AA, Siery Z, Davoudi-Kiakalayeh S. Alloimmunization in thalassemia patients: new insight for healthcare. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:144. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_111_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ozsoy M, Oncul O, Cavuslu S, Erdemoglu A, And GE, Pahsa A. Seroprevalences of hepatitis B and C among health care workers in Turkey. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10(3):150–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sayehmiri K, Azami M, Borji M, Nikpay S, Chamani M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) in Iranian health care workers: systematic review and meta-analysis study. J Occup Environ Heal. 2016;2(1):47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Malkappa SK, Sreekanth B. Hepatitis B and C in healthcare workers: prevalence, relation to vaccination and occupational factors. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2014;3(15):3919–3922. doi: 10.14260/jemds/2014/2376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hiva S, Negar K, Mohammad-reza P, Gholam-reza G, Mohsen A. High level of vaccination and protection against hepatitis B with low rate of HCV infection markers among hospital health care personnel in north of Iran : a cross- sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(920):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09032-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singhal V, Bora D, Singh S. Hepatitis B in health care workers: Indian scenario. J Lab Physicians. 2009;1(2):041–048. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.59697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Petruzziello A, Marigliano S, Loquercio G, Cozzolino A, Cacciapuoti C, Petruzziello A, et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection : an up-date of the distribution and circulation of hepatitis C virus genotypes. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(34):7824–7840. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i34.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sperle I, Steffen G, Leendertz SA, Sarma N, Beermann S, Thamm R, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B, C, and D in Germany: results from a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2020;8:424. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thorburn D, Dundas D, McCruden EAB, Cameron SO, Goldberg DJ, Symington IS, Kirk A, Mills PR. A study of hepatitis C prevalence in healthcare workers in the West of Scotland. Gut. 2001;48(1):116–120. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nejad SB, Allegranzi B, Syed SB, Ellisc B, Pittetd D. Infections liées aux soins de santé en afrique: une étude systématique. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(10):757–765. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.088179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hackshaw A. Small studies: strengths and limitations. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(5):1141–1143. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00136408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hirpara N, Jain S, Gupta A, Dubey S. Interpreting research findings with confidence interval. J Orthod Endod. 2015;1(1):8. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gilbody SM, Song F, Eastwood AJ, Sutton A. The causes, consequences and detection of publication bias in psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102(4):241–249. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ezema IJ. Local contents and the development of open access institutional repositories in Nigeria University libraries: challenges, strategies and scholarly implications. Libr Hi Tech. 2013;31(2):323–340. doi: 10.1108/07378831311329086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Additional file 2. Searched data base with search strategy.

Additional file 3: Table 1. Sensitivity analysis of prevalence of HBsAG among health care workers in Africa for each study being removed at a time, 1989-2020. Table 2. Sensitivity analysis of prevalence of anti – HCV among health care workers in Africa for each study being removed at a time, 1989-2020.

Data Availability Statement

The part of the data analyzed during this study is included in this manuscript. Other data will be available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.