Abstract

Background

Orai3 is a mammalian‐specific member of the Orai family (Orai1‒3) and a component of the store‐operated Ca2+ entry channels. There is little understanding of the role of Orai channels in cardiomyocytes, and its role in cardiac function remains unexplored. Thus, we developed mice lacking Orai1 and Orai3 to address their role in cardiac homeostasis.

Methods and Results

We generated constitutive and inducible cardiomyocyte‐specific Orai3 knockout (Orai3cKO) mice. Constitutive Orai3‐loss led to ventricular dysfunction progressing to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Orai3cKO mice subjected to pressure overload developed a fulminant dilated cardiomyopathy with rapid heart failure onset, characterized by interstitial fibrosis and apoptosis. Ultrastructural analysis of Orai3‐deficient cardiomyocytes showed abnormal M‐ and Z‐line morphology. The greater density of condensed mitochondria in Orai3‐deficient cardiomyocytes was associated with the upregulation of DRP1 (dynamin‐related protein 1). Cardiomyocytes isolated from Orai3cKO mice exhibited profoundly altered myocardial Ca2+ cycling and changes in the expression of critical proteins involved in the Ca2+ clearance mechanisms. Upregulation of TRPC6 (transient receptor potential canonical type 6) channels was associated with upregulation of the RCAN1 (regulator of calcineurin 1), indicating the activation of the calcineurin signaling pathway in Orai3cKO mice. A more dramatic cardiac phenotype emerged when Orai3 was removed in adult mice using a tamoxifen‐inducible Orai3cKO mouse. The removal of Orai1 from adult cardiomyocytes did not change the phenotype of tamoxifen‐inducible Orai3cKO mice.

Conclusions

Our results identify a critical role for Orai3 in the heart. We provide evidence that Orai3‐mediated Ca2+ signaling is required for maintaining sarcomere integrity and proper mitochondrial function in adult mammalian cardiomyocytes.

Keywords: calcium signaling, dilated cardiomyopathy, ion channels, Orai3

Subject Categories: Hypertrophy, Heart Failure, Cardiomyopathy, Remodeling

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- α‐Myh

alpha‐myosin heavy chain

- a.u.

arbitray units

- cKO

cardiomyocyte‐specific knockout

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- DRP1

dynamin‐related protein 1

- EC

excitation‐contraction

- NRCM

neonatal rat cardiomyocytes

- RCAN‐1

regulator of calcineurin 1

- STIM1

stromal interaction molecule 1

- TAC

transverse aortic constriction

- TRPC6

transient receptor potential canonical type 6

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling apoptosis

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

We report that Orai3 is the most abundant Orai isoform expressed in healthy mouse cardiomyocytes.

We provide evidence that constitutive and conditional cardiomyocyte‐specific genetic deletion of Orai3 induces dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure in adult mice.

Orai3 is required for cytoskeletal and energy homeostasis; we have positioned Orai3 as a key protein in cardiac function and structure.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Because dilated cardiomyopathy is a significant problem that contributes to a wide array of cardiovascular diseases, our identification of Orai3 as a new regulator of cardiac function points to previously unknown mechanisms that may emerge as therapeutic targets of heart disease.

Our findings point to the Orai3 channel as a novel Ca2+ source required to maintain cardiac signaling necessary for cardiac structure and could be a future target in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a severe condition, usually idiopathic, resulting in heart enlargement, progressive systolic dysfunction and arrhythmia. 1 , 2 DCM has a poor prognosis leading to heart failure (HF) and death, cardiac transplantation remains the ultimate treatment for patients with end‐stage HF. The molecular mechanisms that trigger the development of DCM remain poorly understood. Genetic abnormalities in the sarcomere, Z‐disc, Ca2+ regulatory and cytoskeletal proteins complex may be causal for DCM. 3 , 4

Experimental evidence suggests that Orai1 (Ca2+ release‐activated Ca2+ modulator 1), is involved in maintaining cardiac pump function and sarcomere structure in invertebrates and lower vertebrates. 5 Loss of Orai1 in zebrafish leads to progressive disruption of myofibers resulting in skeletal muscle weakness and HF. 6 According to the same study, Orai1‐loss was found to induce disruption of the calcineurin signaling transduction machinery at the Z‐disc level. 6 Orai channels are activated by the STIM1 (stromal interaction molecule 1), a single transmembrane protein primarily localized in the endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum. 7 , 8 The STIM1/Orai complex mediates the store‐operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE). 9 , 10 Petersen et al., recently reported that cardiac‐specific suppression of Orai1 or STIM1 in Drosophila causes abolition of SOCE, highly disorganized myofibers, and DCM, 5 further supporting the role of these proteins in healthy cardiomyocytes.

Despite mounting evidence suggests a role of Orai in the myocardium, the function of Orai in adult heart has remained elusive, and some controversy has been generated as to whether Orai1 is expressed in adult mammalian cardiomyocytes. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 For instance, patients lacking functional STIM1 and Orai1 develop a severe form of combined immunodeficiency associated with skeletal muscle myopathy, but these patients show no obvious cardiac muscle‐related phenotypes. 11 , 16 In lymphocytes, as well in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCM), STIM1 and Orai1‐mediated Ca2+ signaling couples to the calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T‐cells (calcineurin/NFAT) pathway. This highly Ca2+‐dependent signaling pathway enables tightly controlled regulation of gene expression through different stimuli that can promote pathological remodeling of the adult heart. Therefore, STIM/Orai has been proposed as an upstream source of Ca2+ that activate the calcineurin/NFAT, 17 , 18 , 19 and it has been postulated that inhibition of Orai1 channel activity or suppression of STIM1 expression in the heart is protective against pathological remodeling. 20 However, transgenic mice with cardiac‐restricted Orai1 deletion did not show any cardiac structural abnormalities, and did not protect agaist angiotensin‐II‐induced pathological cardiac remodeling. 21

Orai2 and Orai3 are homologs of Orai1. 22 In contrast to the Orai1 gene, which is present in invertebrates and vertebrates alike, the Orai3 gene is exclusive to mammals, 23 and has been relatively under‐investigated. Perhaps the exclusive existence of Orai3 in mammals could explain why Orai1 loss of function in Zebrafish and Drosophila has deleterious effects not seen in human patients carrying STIM1/Orai1 mutations. 11 , 16 Cardiomyocytes from hypertrophic rat hearts exhibit a voltage‐independent, inward current activated by arachidonic acid, a known activator of the Orai1/Orai3 channel complex. 15 Moreover, a recent study reported that acute inhibition of Orai3 using siRNA accelerates isoproterenol‐induced HF. 24 Taken together, these data suggest that Orai3, and maybe Orai1, play a critical role in preserving the structural integrity and function of the mammalian heart. However, the role of these channels in cardiac physiology and pathology remains elusive.

For a detailed investigation of the physiological role of cardiac Orai channels, we used a Cre‐LoxP system to generate conditional and inducible Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific knockout mice (Orai3cKO). We show that deletion of Orai3, specifically in adult mouse cardiomyocytes, induces DCM characterized by progressive loss of ventricular function leading to HF and premature death. We found that cardiomyocytes from Orai3cKO mice exhibited abnormal cytoskeletal structure associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and dysregulation of critical elements of the excitation contraction‐coupling (EC‐coupling). These results suggest an indispensable role for Orai3 in maintaining cardiac structure and function. We conclude that Orai3cKO mice resemble the morphological and clinical cardiac features as those observed in acquired adult DCM in humans and may be used as a model for this condition.

Methods

Data Availability Disclosure Statement

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available on request to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedures reported here.

Mouse Models Generation

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and comply with US regulations on animal experimentation. Mice were housed in a facility maintained at 22°C with an alternating 12‐hour light/dark cycle and had free access to food and water ad libitum. Orai1 flox/flox and Orai3 flox/flox mice were crossed with transgenic mice FVB‐Tg(Myh6‐cre)2182Mds/J, expressing Cre‐recombinase under the cardiomyocyte‐specific α‐Myh6 (α‐myosin‐heavy chain promoter) (Jackson Laboratory, cat. 011038). Mice were backcrossed for 6 generations with C57BL/6N mice to harbor cardiac‐specific Orai1‐ or Orai3‐deficient (Orai1cKO and Orai3cKO) mice. Tamoxifen‐inducible, cardiomyocyte‐specific, Orai1cKO and Orai3cKO mice were obtained by crossing Orai1 flox/flox and Orai3 flox/flox with tamoxifen‐inducible Cre recombinase under the α‐Myh cardiac‐specific promoter: (C57BL)‐Tg(Myh6‐ cre/Esr1*)1Jmk/J, (Jackson laboratory, cat. 5657).

Cardiac Phenotyping

Mice from both groups were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed on the warming pad of a recording stage of a Vevo 2100 ultrasound machine. The anterior chest was previously shaved, ultrasound coupling gel was applied, electrodes were connected to each limb, and an ECG was simultaneously recorded while body temperature was monitored. Two‐dimensional (short axis‐guided) M‐mode measurements (at the level of the papillary muscles) were taken using an 18 to 32 MHz MS400 transducer as previously described. 25 , 26 , 27 Images were also recorded in the parasternal long‐axis. For analysis purposes, ≥3 beats were averaged; measurements within the same heart rate interval (500±50 bpm) were used for analysis. Measurements were performed before and after left anterior descending coronary artery ligation. Pressure‐volume loop measurements were taken with the ADV 500 PV system (Transonic Scisense).

Histological and Morphometric Analysis

The heart was arrested in diastole by nominally Ca2+ free Tyrode solution containing 2,3‐butanedione monoxime, (10 mmol/L), and was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes under pressure (diastolic arterial pressure). The heart was excised, weighed, and stored for 24 to 48 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde. Picrosirius Red staining was performed on 5‐μm‐thick paraffin‐embedded tissue sections. 28 Wheat‐germ agglutinin (WGA) staining was performed using FITC‐conjugated lectin (Sigma Aldrich L4895). Heart sections were incubated with WGA solubilized in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature. After washing 3 times with PBS, the sections were mounted with Prolong Gold containing DAPI (Invitrogen, cat. P36931) and kept at 4°C in dark. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling apoptosis (TUNEL) staining was performed using Invitrogen Click‐IT Plus TUNEL assay (ThermoFisher, cat. C10618). Images were obtained for all histological experiments using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal laser scanning microscope. Fibrosis, apoptosis, and cell area were measured using ImageJ.

Myocyte Isolation From Neonatal and Adult Hearts

NRCM were isolated from Sprague‐Dawley rats (1–3 day‐old) as described earlier. 25 , 29 Bfiefly, neonatal rat hearts were removed, atria were trimmed off, the remaining ventricles were minced and the myocytes were dissociated with a Ca2+/bicarbonate free Hanks buffer (pH 7.5) containing penicillin (50 000 U/L)/streptomycin (50 mg/L), gentamicin (50 mg/L), heparin (5000 USP units/mL), DNase I (2 mg/mL), and trypsin (1.5 mg/mL) at 25°C with gentle mixing. The dissociated NRCMs were pre‐plated for 2 hours to reduce non‐myocyte contamination, the medium was then replaced with DMEM (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 5% FBS (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA), Bromodeoxyuridine / 5‐bromo‐2'‐deoxyuridine (BrdU) (0.1 mmol/L; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA), vitamin B12 (1.5 mmol/L; Sigma), and antibiotics. After the first 24 hours, the medium was replaced again with DMEM supplemented with: insulin (10 µg/mL; Sigma), transferrin (10 µg/mL; Sigma), vitamin B12 (1.5 mmol/L; Sigma), and antibiotics. NRCM were grown on fibronectin‐coated coverslips. Cells were transfected with G‐GECO1‐Orai3 30 and STIM1‐mCherry using lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies). Live‐cell imaging was conducted using the IX83 Olympus microscope attached to a Zyla 5.5 sCMOS camera.

Adult mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated using the langendorff retro‐reperfusion method and digested using collagenase type II (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) as described earlier. 31 Mouse myocytes loaded with different fluorophores as indicated in the text (ie, fura‐2, JC‐1), according to the manufacturer. Cells were observed on a Nikon Eclipse TE300 or IX83 Olympus microscope. Cells were used within 6 hours from the isolation.

Transmission Electron Microscopic Analysis

Cardiac muscle samples were obtained and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours at 4°C. After washing in cold cacodylate buffer, the specimens were post‐fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, stained in aqueous uranyl acetate, and then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultra‐thin sections (600–800 Å) from the resin blocks were stained using lead citrate and examined by transmission electron microscopy (TAM), (JEOL 2000EX).

Cell Shortening and Intracellular Ca2+ Measurements

Morphological and mechanical properties of the myocytes and intracellular Ca2+ activity were measured using the methods described earlier. 31 , 32 Briefly, after a period of Ca2+ re‐adaptation, isolated cardiomyocytes cells were stored in Tyrode solution (0.5 mmol/L CaCl2) and used within 6 hours from the isolation. Cell shortening was measured in naïve cells placed in a perfusion chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Eclipse T300, Nikon). The cells were left to attach on a coverslip pre‐coated with laminin and were bathed with modified Tyrode solution, which contained (in mmol/L) 137 NaCl, 10 glucose, 5.4 KCl, 1.3 MgSO4, 2.0 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). Cells were electrically paced, video motion edge detector software (Ionoptix, Milton, MA) was used to analyze and calculate the myocyte shortening fraction and the maximal rates of the cell shortening and re‐lengthening. Cell length was assessed in 15 to 25 myocytes/heart. For intracellular Ca2+ measurements, the myocytes were incubated with fura‐2 for 30 minutes at room temperature (22°C–24°C). Excess of fura‐2 was washed out and the cells were re‐suspended in physiological buffer with 0.5 mmol/L CaCl2. Cells were excited at 360/380, fluorescence emission was detected at 510 (interpolated method) with a dual‐excitation fluorescence multiplier system (IonOptics). Steady‐state contractions or Ca2+ transients were averaged for each cell and used. SOCE was measured with the following method: fura2‐loaded cardiomyocytes were electrically stimulated to confirm the presence of Ca2+ transients, then in the absence of electrical stimulation, cells underwent store depletion by adding thapsigargin (5 µmol/L) and caffeine (10 mmol/L) to the extracellular, Ca2+ free buffer. This procedure is commonly used to induce STIM1 oligomerization and activation of SOCE. When intracellular Ca2+ reaches baseline, extracellular Ca2+was added and the cytosolic fluorescence signal was recorded.

Western Blots

Total proteins were extracted from mutants and control hearts by bead homogenization in RIPA Lysis Buffer (ThermoFisher cat. #89900) in the presence of a mixture of protease inhibitors (Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail cat. #78438). The homogenates were centrifuged at 13 000 rpm (20 784g) for 10 minutes at 4°C to obtain clarified lysates. Cell lysates were separated by precast PAGE gels (Genscript) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF). In this study, the following primary antibodies were used for Western blot and immunohistochemical detection: mouse anti‐Orai1 (Santa Cruz, cat. sc‐377281), rabbit anti‐Orai2 (Proteintech, cat. 26766), rabbit anti‐Orai3 (ProSci, cat. 4117), rabbit anti‐TRPC6 (transient receptor potential canonical type 6) (Abcam, cat. ab62641), rabbit anti‐tubulin (Cell Signaling, cat. 2146), rabbit anti‐GAPDH (Cell Signaling, cat. 5174), rabbit anti‐DRP1 (dynamin‐related protein 1) (Invitrogen, cat. pa5‐20176), mouse anti‐SERCA2a (sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+‐ATPase) (Santa Cruz, cat. sc‐376235), rabbit anti‐NCX1 (Abcam, cat. ab177952), rat anti‐ERTR7 (fibroblast marker, Santa Cruz, cat. sc‐73355, phalloidin (Invitrogen, cat. R415). Protein loading was normalized to a reversible total protein stain (Li‐Cor, cat. 926‐11010), GAPDH or beta‐tubulin. Primary antibodies were detected by appropriate secondary antibodies, and membranes were imaged using blot imager LI‐COR Odyssey system according to manufacturer protocols.

Data Analysis

All data were expressed as mean±SEM. Comparisons between the control group and OraicKO were performed with the Student t‐test on raw data before normalization. Comparisons between >2 groups were conducted on raw data with ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction, which was calculated with GraphPad Prism, version 9 (GraphPad Software; San Diego, CA, USA). Cardiac phenotype studies were performed blind with experimenters not knowing the genotype of the mouse. In cases when the 2 control groups were combined, statistics were performed on the pooled raw data of both control groups and compared with OraicKO mice with the Student t‐test. Experiments using isolated cardiomyocyte (n) were obtained from several heart (N) preparations.

Results

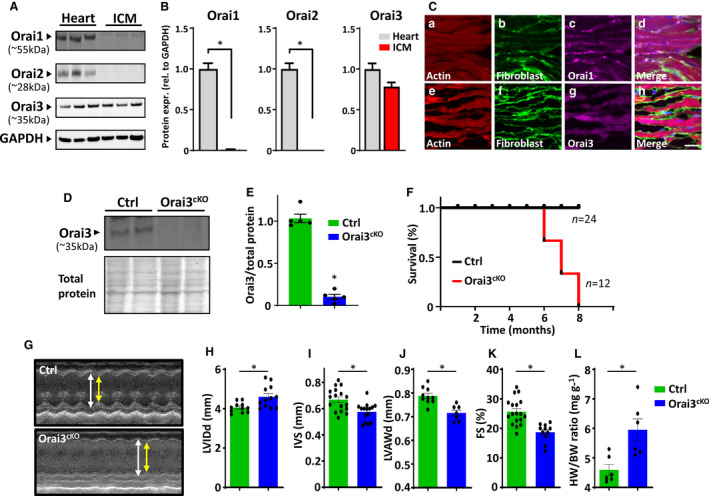

Orai Isoform Expression in Cardiac Tissue and Cardiomyocytes

We first evaluated the expression pattern of all 3 Orai isoforms (Orai1‒3) in the mouse heart. Protein immunoblots of crude cardiac tissue lysate produced a band at ≈55 kDa corresponding to Orai1; this is higher than the predicted size because of protein glycosylation in its native environment. 33 Orai2 and Orai3 were detected near the expected molecular size at ≈28 and ≈37 kDa, respectively. In contrast, lysates enriched with freshly isolated cardiomyocytes from adult mice displayed the presence of Orai3 protein, while Orai1 and Orai2 proteins were not detectable (Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. Orai isoforms expression in the heart and cardiac phenotype of Orai3cKO mice.

A, Expression profiling of Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 proteins in tissue lysates from the whole heart and freshly isolated adult cardiomyocytes. Protein load was normalized to GAPDH. B, Quantitative data analysis of Orai isoforms expression shown in (A), data presented as fold change tissue vs. isolated cardiomyocytes. C, Representative images of immunofluorescent staining of Orai1 and 3 in cardiac muscle from wild‐type mice. Tissue was stained with phalloidin (red), fibroblast marker ER‐TR7 (green), and Orai1 or ‐Orai3 antibody (violet). Scale bar=50μm. D and E, Western blot analysis of lysates from cardiac tissue reveals reduced Orai3 protein amount in Orai3cKO hearts. Protein load was normalized to total protein. F, Kaplan–Meier survival curve shows that Orai3 loss reduces the survival of Orai3cKO mice. G, Representative echocardiography images (M‐mode) and analyses showing left ventricular wall thickness in control vs. Orai3cKO mice. Quantitative analysis of cardiac function, showing increased left ventricular internal dimension in (H), and wall thickness in interventricular septum and LV anterior wall decreased (I and J). K, Fractional shortening was significantly lower in Orai3cKO mice than in control mice (*P<0.05). L, The ratio of heart weight to body weight was significantly higher in Orai3cKO mice (*P<0.01). Statistical significance was determined via 2‐sided Student t‐tests and reported as mean±SEM. Ctrl indicates control; FS, fractional shortening; IVS, interventrular septum; LV, left ventricle; LVAWd, left ventricle anterior wall, diastole; LVIDd, left ventricle internal dimension, diastole; and Orai3cKO, Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific knockout.

The spatial distribution of Orai1 and Orai3 in adult mouse heart appeared to be cell‐specific. Orai1 immunoreactivity was mainly associated with fibroblasts and co‐stained with the fibroblast marker ER‐TR7. Cardiomyocytes stained poorly with Orai1 antibody (Figure 1C, a through d). In contrast, anti‐Orai3 staining colocalized mainly with phalloidin staining, which suggested the presence of Orai3 in cardiomyocytes with a weak signal from the interstitial cells (Figure 1C, e through h). It has been reported that gene expression of STIM and Orai in the heart is dynamic and undergoes pronounced changes during development. 17 , 34 We show that while STIM1 and Orai1 were abundantly expressed in the NRCM, Orai3 protein level was barely detectable at this stage. In contrast, in the adult myocardium, we observed a dramatic downregulation of STIM1 and Orai1 and a rise of Orai3 expression (Figure S1A and S1B). These findings suggest a distinct spatial distribution of Orai isoforms in the mouse cardiac tissue and that Orai3 is the predominant isoform expressed in the post‐natal heart.

Orai3cKO Mice Develop DCM and HF

To address the physiological role of Orai3 channels in the myocardium, we generated Orai3cKO mice. Mutant mice were viable and born at the expected Mendelian ratios, indicating the absence of embryonic lethality. Orai3cKO mice were fertile and were indistinguishable from control mice expressing the Orai3 wild type (wt) allele and cre‐recombinase (Orai3wt /wt‐α‐Myh‐\+). Examination of 5‐week‐old Orai3cKO mice confirmed the lack of Orai3 protein from cardiac tissue homogenates (Figure 1D and 1E), further suggesting that most of the Orai3 present in the heart is expressed in cardiomyocytes. The Orai3cKO mice had a reduced lifespan, with death occurring between 6 and 10 months of age, as quantified by Kaplan‒Meier survival curve analysis (Figure 1F).

Echocardiographic analysis of adult (12–16 weeks) Orai3cKO mice revealed dilation of the left ventricular (LV) chamber as suggested by increased end‐diastolic LV internal dimension associated with thinning of the LV anterior wall and interventricular septum (Figure 1G through 1J). Reduced cardiac function was observed in the Orai3‐null mice, shown as decreased fractional shortening percentage (Figure 1K). The heart weight to body weight ratio was increased in the Orai3cKO mice when compared with the control group (Figure 1L). Overall, Orai3cKO mice showed the anatomic features of eccentric hypertrophy characterized by dilation of the ventricular chambers and compromised cardiac function. Our data provide evidence that Orai3 protein expression in the adult myocardium is required for maintaining cardiac function and structure.

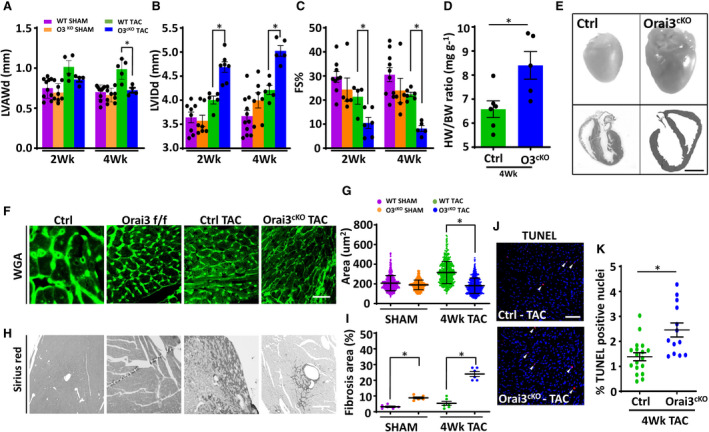

Orai3 Expression Protects the Heart From Pressure Overload‐Induced HF

STIM1 and Orai1 have been implicated in stress‐induced maladaptive cardiac remodeling. 25 , 34 In contrast, the role of Orai3 in the heart remains unknown. To test the hypothesis that Orai3 is involved in pathological cardiac remodeling in mammalians, we subjected Orai3cKO and control mice to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) to induce LV pressure‐overload and HF. Because of the severity of the cardiac phenotype of Orai3cKO older mice, we used young (1–2 months) mice that exhibited a mild cardiac phenotype as assessed by echocardiography.

Cardiac function was evaluated by 2D echocardiography at various times post‐surgery. Two weeks post‐TAC, Orai3cKO mice showed a significant increase of LV internal dimension accompanied by a mild reduction in cardiac contraction measured as fractional shortening percentage. The LV chamber further dilated and cardiac function progressively degraded at the 4‐week time point. In contrast, the control group exhibited a typical compensatory response with thickening of the free ventricular walls and mild LV chamber dilation (Figure 2A through 2C). Post‐mortem analysis confirmed cardiac chamber dilation and cardiac hypertrophy in Orai3cKO mice (Figure 2D and 2E). Most Orai3cKO mice with TAC died prematurely at the 7‐week timepoint because of HF and pulmonary edema with occasional left atrial fibrin clots.

Figure 2. Transverse aortic constriction (TAC) accelerated progression toward heart failure in Orai3cKO mice.

A through C, Echocardiographic measures of cardiac function at 2‐ and 4‐weeks post‐TAC. A and B, Orai3cKO TAC mice showed a thinner left ventricular anterior wall and dilated left ventricular chamber. C, Fractional shortening decreases dramatically in Orai3cKO TAC mice with worse cardiac function starting at week 2 post‐TAC. D, Postmortem analysis, HW/BW, indicated greater heart weight in Orai3cKO TAC mice than the hearts from the control TAC mice. E, Upper panels, representative pictures showing post‐TAC hearts from control and Orai3cKO mice. E, Lower panels, representative photographs of transverse heart sections. Scale bar=2 mm. F and G, Representative immunofluorescence of transverse heart section stained with WGA and cross‐sectional area analysis. Scale bar=100 μm. H and I, Representative images of transverse heart section stained with Sirius red showing greater fibrosis in Orai3cKO TAC mice. Scale bar, 200 μm. J, Photomicrograph showing apoptosis‐positive nuclei visualized in red identified by TUNEL staining. All nuclei were stained with DAPI shown in blue. White arrows indicate apoptotic cells. Scale bar, 100 μm. K, Quantitative analysis of the apoptotic cells from control and Orai3cKO heart sections. Data are shown as mean±SEM. Data in (D and K) were analyzed with paired t‐test. Data in (A through C, G through I) were analyzed with ANOVA 2‐way analysis followed by Bonferroni correction. *P<0.05 vs control TAC group. FS indicates fractional shortening; HF, heart faulure; HW/BW, heart weight‐to‐body weight ratio; LV, left ventricle; LVAW, left ventricle anterior wall; LVID, left ventricular internal dimension; Orai3cKO, Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific knockout; TAC, transverse aortic constriction; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling; and WGA, wheat‐germ agglutin.

Wheat‐germ agglutinin staining for cell size assessment confirmed the presence of cell hypertrophy in post‐TAC control cardiac tissue. In contrast, Orai3cKO showed a decrease of cross‐sectional area (Figure 2F and 2G) associated with greater fibrosis and collagen deposition than the relatively healthy hearts from the control group (Figure 2H and 2I). Cardiac apoptosis is an essential mechanism of pathological stimuli‐induced cell death and a significant factor underlying pressure overload‐induced cardiac dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. 35 , 36 Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that loss of Orai3 induces cardiac structural and functional deterioration by increasing cardiomyocyte susceptibility to apoptosis. TUNEL analysis performed on cardiac section from mice subjected to TAC showed a higher incidence of apoptotic cells in Orai3cKO hearts than control hearts. These results indicate that Orai3 is required for the maintenance of normal heart function by preventing cardiomyocyte cell death in response to cardiac stress.

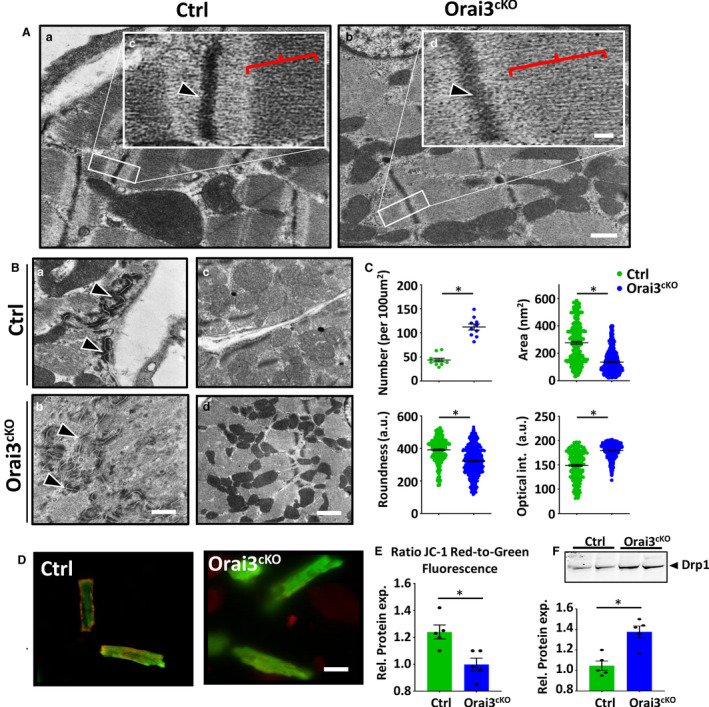

Orai3‐Loss Causes Aberrant Myocyte Cytoarchitecture and Altered Mitochondrial Morphology

Orai1 has been linked to the maintenance of sarcomere integrity in skeletal and cardiac muscle of invertebrates and lower vertebrates. 5 , 37 However, these findings were not corroborated in mammalians. Based on our data and in silico analyses of Orai isoforms distribution pattern, we reasoned that Orai3 compensates for the lack of Orai1 in mouse cardiomyocytes. Morphologic and ultrastructural examination of ventricular myocardium showed that sarcomeres from the Orai3cKO heart were disorganized compared with those from matched controls. The ultrastructure of the Z‐line in left ventricular cardiomyocytes Orai3cKO exhibited a lower density of myofibrils and defect in the demarcation of Z‐line and M‐line (Figure 3A, a and b). Orai3‐deficient cardiomyocytes displayed wider Z‐lines (461.1±121.6 versus 102.9±12.1 nm; P<0.001; Orai3‐deficient versus control, respectively). The M‐line structure was mostly lost in areas with severe disruption of Z‐line architecture. Intercalated discs of control samples were clearly observed connecting adjacent myocytes end‐to‐end. However, in Orai3CKO intercalated disc structures were variably affected, highly convoluted, and gaps of the intercalated discs were significantly widened in some cases. Overall, the number of gap junctions in Orai3cKO hearts was significantly reduced (Figure 3B, a and b).

Figure 3. Sarcomere and mitochondrial dysfunction in Orai3cKO mice.

A, a and b showing representative transmission electron microscopy pictures of the sarcomere structure of cardiac muscle from 1‐month‐old male mice. Scale bar=500 nm. High magnification images (inset, c‐d) depicting normal Z‐line (arrowhead) and M‐band (red parenthesis) in the control and disorganized Z‐line and shallow M‐band in Orai3cKO sections. Scale bar=10 nm. B, Cross‐sections through intercalated disc showing large mixed‐type junction (area composita) surrounded by two dense desmosome structures (a and b, black arrows). Representative ultrastructural images of left ventricle from control and Orai3cKO hearts showing normal (control) and altered (Orai3cKO) mitochondrial morphology and density (c and d). C, Graphs summarizing mitochondria number, mitochondrial size, mean cross‐sectional area, and optical. Data are expressed as mean±SEM t‐test, ⁎ P<0.01 for Orai3cKO vs. control. D and E, Representative photograph and analysis of cardiomyocytes loaded with JC‐1 to measure mitochondrial membrane potential, emissions at 525/585 are visualized in green and red fluorescence, respectively. Scale bar=50 µm. Cells isolated from 3 mice each group, t‐test: *P<0.01. F, Immunoblot and analysis showing that the expression of DRP1 (dynamin‐related protein 1) was increased in Orai3cKO hearts when compared with the control group. Loading was normalized using total protein (Figure S5). DRP1 indicates dynamin‐related protein 1; LV, left ventricle; Orai3cKO, Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific knockout; and TEM, transmission electron microscopy. t‐test: *P<0.01.

Cytoskeletal disarray increases susceptibility to apoptosis and is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. 38 , 39 We then investigated whether the cytoarchitecture aberration observed in Orai3cKO mice was associated with altered mitochondrial morphology and distribution. We performed ultrastructural and morphometric analysis on a subset of myocardial samples (Orai3cKO versus control). A mean of 805 isolated mitochondria (defined as organelles enclosed by a double‐contoured membrane) was analyzed from each sample (range, 500–1230; SD±116.18). As shown in Figure 3B (c and d), mitochondria from Orai3cKO heart are increased in number and appear smaller as compared with control. The absolute number of mitochondria per area was increased in Orai3cKO, while the mean cross‐sectional area of individual mitochondria was reduced in Orai3cKO compared with controls (Figure 3C). During apoptosis, mitochondrial membrane potential decreases, inducing the releases of mitochondrial apoptogenic factors. 23 To test whether loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) was associated with the increased apoptosis observed in the Orai3cKO, we measured ΔΨm in JC‐1 loaded viable control and Orai3cKO isolated cardiomyocytes. JC‐1 is a positively charged carbocyanine dye that accumulates in the inner mitochondrial membrane and fluoresces in green at low and in red at high membrane potentials. JC‐1‒stained control cells displayed healthy mitochondria with high red to green ratio, whereas in many Orai3‐deficient cardiomyocytes exhibited predominantly green fluorescence, which indicated dysfunctional depolarized mitochondria (Figure 3D and 3E). Mitochondrial fragmentation usually precedes apoptosis in a phenomenon mediated by DRP1, a fission‐related protein. Accordingly, we observed that the expression level of DRP1 was elevated in Orai3cKO mice (Figure 3). In conclusion, these data suggest that Orai3 is required for promoting proper cardiomyocyte cytoarchitecture and maintain optimal mitochondria shape and function.

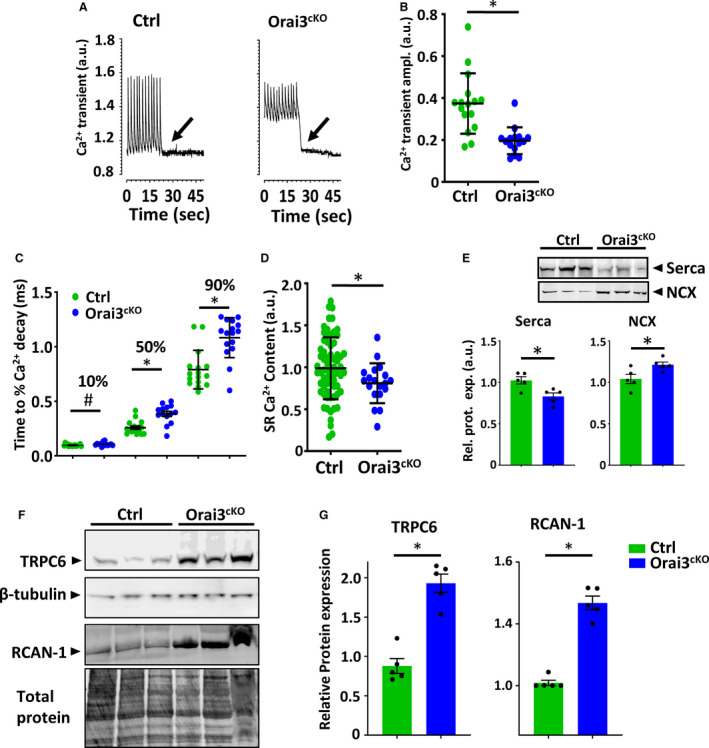

Orai3 is Essential for Maintaining Normal EC‐Coupling

The potential effect of Orai3‐loss on the intracellular Ca2+ cycling was measured in individual myocytes isolated from hearts of 3‐ to 4‐month‐old mice. Cardiomyocytes from the Orai3cKO mice exhibited higher resting Ca2+ levels during pacing protocols (1Hz) that significantly dropped when pacing was ceased (Figure 4A). Electrically evoked Ca2+ transients showed reduced peak amplitude in Orai3‐deficient cells (Figure 4B). The decay time of the Ca2+ transient was significantly prolonged at 50% and 90% (Figure 4C). We found that endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ loading, measured as caffeine‐induced Ca2+ release, was decreased in Orai3‐deficient cardiomyocytes (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Intracellular Ca2+ recordings and regulation of essential proteins for the excitation‐contraction‐coupling.

A, Ca2+ transients from fura‐2 loaded adult mouse ventricular myocyte. Cells were initially stimulated at 1 Hz; the stimulator was turned off as indicated by the arrow. B, Mean Ca2+ transient amplitude in Orai3cKO and control myocytes. C, Decay kinetics Ca2+ transient in Orai3cKO and control myocytes using an exponential smoothed curve fitting function at 10% decay, 50% decay, and 90% decay. D, SR load determined by caffeine‐induced Ca2+ release. Statistical analysis, t‐test, *P<0.05 vs control (n, 28‒24 myocytes per group). E, SERCA and NCX, immunoblots and bar graphs. SERCA protein levels were reduced in the Orai3cKO heart compared with the control heart. The NCX level was higher in Orai3cKO than control mice. Loading was normalized using total protein (Figure S5). F and G, Immunoblot image and quantification analysis on TRPC6 and RCAN‐1 immunoblots. Both TRPC6 and RCAN‐1 expression was higher in Orai3cKO than control. All values were normalized to β‐tubulin or total protein to correct for minor loading variations. Statistical analysis. T‐test, (P<0.05). EC indicates excitation‐contraction; NCX, sodium‐calcium exchanger; Orai3cKO, Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific knockout; RCAN‐1, regulator of calcineurin 1; SERCA, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+‐ATPase; SR, endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum; and TRPC6, transient receptor potential canonical type 6.

Orai3 is a member of the store‐operated Ca2+ channels (SOCC), hence, we evaluated its response to intracellular store emptying in isolated adult cardiomyocytes. Cells were subjected to Ca2+ free buffer and exposed to thapsigargin, an SERCA inhibitor, to deplete internal Ca2+ stores. Ca2+ was then returned to the media and entry into the cell was monitored by a change in the fura‐2 fluorescence absorbance ratio. About 50% of adult control myocytes showed a subtle but significant Ca2+ entry. In contrast, all Orai3cKO cells analyzed did not show Ca2+ entry when Ca2+ was reintroduced in the extracellular solution (Figure S2).

Since Ca2+ clearance was affected in the Orai3‐deficient cells we further analyzed the expression of essential proteins involved in the Ca2+ cycle. We found decreased SERCA expression accompanied by increased NCX (sodium Ca2+ exchanger) expression (Figure 4E). This was in keeping with the prolonged Ca2+ decay time and more in general with the HF phenotype of Orai3cKO mice. Some members of the TRPC channels family have often been suspected of acting as (SOCC) or being affected by them. We found elevated levels of TRPC6 protein in the Orai3cKO heart lysates (Figure 4F). A sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ level can trigger downstream gene transcription believed to play a causative role in adverse cardiac remodeling and the pathogenesis of HF. Accordingly, we found that the RCAN1 (regulator of calcineurin‐1) expression was increased in Orai3cKO mice (Figure 5G), suggesting calcineurin signaling activation, this was probably attributable to the Ca2+ overload from the defective Ca2+ cycle and the TRPC6 upregulation in response to Orai3 deletion.

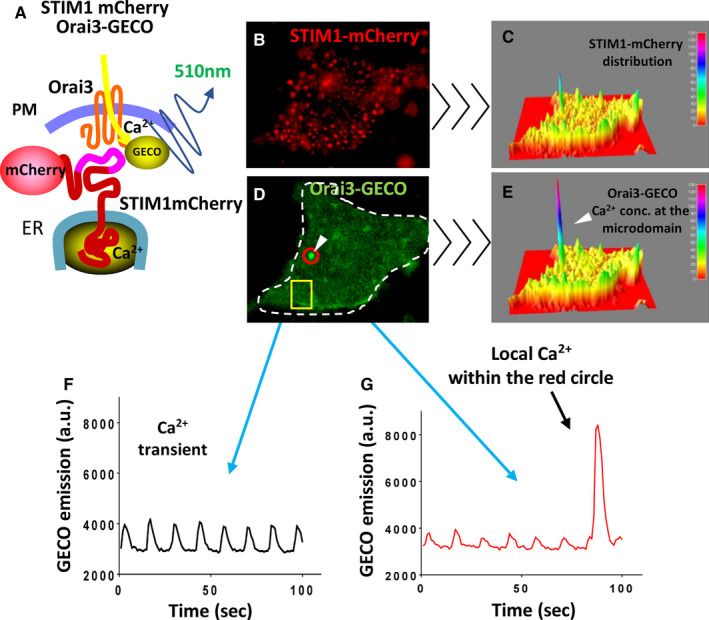

Figure 5. Orai3 channel optical recording in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes.

A, Cartoon showing the strategy followed to detect Orai3 dependent Ca2+‐entry. Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were co‐transfected with STIM1 (stromal interaction molecule 1)‐mCherry and with Orai3‐GECO (genetically encoded calcium indicators for optical imaging). Fluorescent tags were visible under an epifluorescent microscope and Ca2+ entry from Orai3 was detected by GECO attached to the cytoplasmic portion of Orai3. B, NRCM expressing STIM1‐mCherry and excited at 550 nm. C, Three‐dimensional profile of STIM1‐mCherry distribution in a resting cell. D, Same cell as in (B) showing Orai3‐GECO distribution excited at 488 nm. E, Three‐dimensional profile of the same cell showing a Ca2+ microdomain detected by Orai3‐GECO (E). F, Global Ca2+ transients detected from the yellow square from (D). G, Ca2+ transients captured from the spot circled in red from (D) showing Ca2+transients and then a Ca2+ concentration microdomain. The video from which these frames were extracted is provided as supplemental material. ER indicates endoplasmic reticulum; GECO, genetically encoded calcium indicators for optical imaging; NRCM, neonatal rat cardiomyocytes; Orai3cKO, Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific knockout; PM, plasma membrane; and STIM1, stromal interaction molecule 1.

We previously reported that STIM1‐tagged with a genetic Ca2+ sensor, the GCaMP6, associates with Ca2+ concentration microdomains in cardiomyocytes. 25 To determine whether Orai3 mediate Ca2+ influx, NRCMs were co‐transfected with mCherry‐tagged STIM1 and Orai3 tagged with GECO1.2, the Ca2+ sensor, attached in its cytosolic portion of the channel. 30 This highly informative model allows the visualization of STIM1, Orai3, and Ca2+‐entry detected by the GECO1.2 domain in live cardiomyocytes (Figure 5A). When overexpressed, the spatial distribution of STIM1‐mCherry suggested the formation of clusters as we and others have reported earlier, 12 , 25 and shown in Figure 5B and 5C. STIM1/Orai3 form complexes when expressed together, however, Orai3‐GECO1.2 aggregates in cells not expressing STIM1‐mCherry, probably indicating Orai3 interacting with endogenous STIM1 (Figure 5D and 5E, Figure S3). Cells were electrically paced to induce Ca2+ transients that were detected by the cytosolic GECO1.2 portion of the tagged Orai3. We observed spontaneous Ca2+ entry at the STIM1/Orai3 interaction sites independent of the global cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Figure 5D through 5G and Video S1). Importantly, these data show that Ca2+‐entry through the STIM1/Orai3 complex is independent of the electrically evoked global Ca2+ transients.

Rapid Orai3 Downregulation in the Adult Myocardium Causes DCM and HF

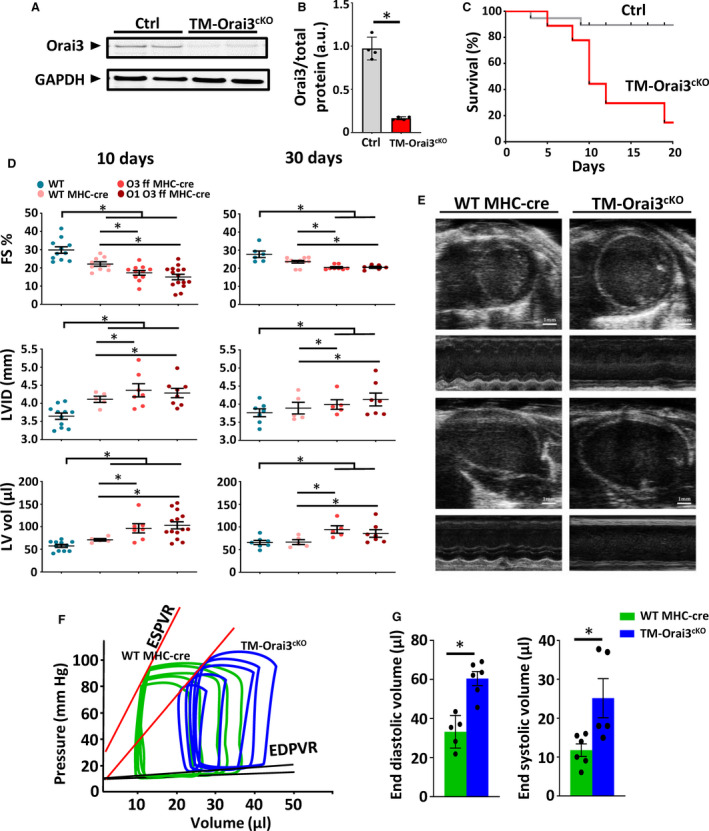

Our findings that Orai3 is predominantly expressed in the adult myocardium prompted us to evaluate the impact of Orai3 deletion on the cardiac function of adult mice. We generated a tamoxifen‐inducible cardiomyocyte‐specific Orai3 knockout (TM‐Orai3cKO) mouse by crossing mice carrying loxP‐flanked alleles of Orai3 with the cardiac‐specific α‐Myh promoter directing expression of a tamoxifen‐inducible Cre recombinase (MerCreMer) in adult cardiomyocytes. 40 To rule out any contribution from Orai1, which has been reported to be expressed in cardiomyocytes during pathological conditions, 41 the same strategy was used to generate TM‐inducible Orai1/Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific double knockout mice. Two weeks after tamoxifen injection, expression of Orai3 protein in TM‐Orai3cKO mouse hearts was almost totally abolished compared with controls (Figure 6A and 6B). TM‐injected TM‐Orai3cKO mice died prematurely. In contrast, the survival rate in the controls was not significantly affected (Figure 6C). Serial echocardiography revealed that 15 days after TM injection, mice expressing MerCreMer (used as a control group) exhibited depressed cardiac function. However, such detrimental effect was greater in the TM‐Orai3cKO and TM‐inducible Orai1/Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific double knockout mice (Figure 6D). The LV internal dimension and LV volume increased significantly in the MerCreMer mice and was significantly higher in TM‐Orai3cKO and TM‐inducible Orai1/Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific double knockout mice. Thirty days post‐TM injection, cardiac dysfunction induced by MerCreMer was reduced, and heart function recovered to levels comparable with those of wild‐type mice. However, most of the TM‐Orai3cKO and TM‐inducible Orai1/Orai3 cardiomyocyte‐specific double knockout mice had died at this point, and those that survived showed significantly depressed cardiac function and exaggerated LV dilation (Figure 6D and 6E). Pressure‐volume loop measurements in both control and TM‐Orai3cKO mice 30 days after TM injection are illustrated in Figure 6F, and hemodynamic parameters are reported in Figure 6G. Compared with control mice, TM‐Orai3cKO mice showed a significant LV volume increase, the slope of the end‐diastolic pressure‐volume relationship, which describes the diastolic function and passive properties of the ventricle, was elevated in TM‐Orai3cKO mice, suggesting an increase in diastolic myocardial stiffness in TM‐Orai3cKO mice. Collectively, these data show impaired cardiac function in the adult myocardium subsequent to genetic Orai3 deletion. Quantitative analysis of apoptosis‐positive nuclei in cardiac myocytes revealed increased apoptotic cell death in the TM‐Orai3cKO hearts. At the cellular level, cardiomyocytes were elongated and thinner (Figure S4). Overall, the cardiac phenotype of TM‐Orai3cKO was consistent with the DCM observed in the constitutive Orai3cKO mice.

Figure 6. Deletion of Orai3 in adult cardiomyocytes results in dilated cardiomyopathy.

A and B, Representative and summarized Western blot analysis of Orai3 protein in control and TM‐Orai3cKO, 2 weeks post‐tamoxifen injection, n=5 mice each group, t‐test, *P<0.01. C, Kaplan–Meier survival curve shows that Orai3 loss reduces survival of TM‐Orai3cKO mice. D, Echocardiographic analyses of TM‐Orai3cKO mice and ctrl mice at 10‐ and 30‐days post‐tamoxifen injection. FS, LVID, and LV vol measurements are shown. Two‐way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test was used to compare the mean differences between groups, P<0.05. E, Frames extracted from echocardiographic videos performed 30 days post‐tamoxifen injection showing trans‐thoracic B‐mode and M‐mode from controls and TM‐Orai3cKO mice in both long‐ and short‐axes view. F and G, Representative left ventricular pressure‐volume loops performed 30 days post‐tamoxifen from TM‐Orai3cKO and control group illustrate the emerging systolic dysfunction (ie, rightward shift in the end‐systolic pressure‐volume relationship and the upward shift of end‐diastolic pressure‐volume relationship) in TM‐Orai3cKO mice; n=5 mice each group, t‐test, *P<0.05. ESPVR indicates end‐systolic pressure volume relationship; FS, fractional shortening; LV, left ventricle; LVID, left ventricular internal diameter; MHC, myosin heavy chain. Orai3 ff, Orasi flox/flox; Orai1 Orai3 ff; Orai1 and Orai3 double floxed; TM, tamoxifen‐inducible; TM‐Orai3cKO, tamoxifen‐inducible cardiomyocyte‐specific Orai3 knowckout; and WT, wild‐type.

Discussion

The role of local Ca2+ signaling that governs cardiac homeostasis and remodeling has been extensively studied, but remains one of the least understood processes. In our present study, we used several experimental models and found that Orai3 Ca2+ channel is critical for maintaining the proper function and structure of the mouse heart. First, we established that among all 3 Orai isoforms, Orai3 is the most abundant in the healthy adult mouse myocardium. In contrast, Orai1 and STIM1 are more abundant in neonatal cardiomyocytes and are downregulated in adult cardiomyocytes. This implies the presence of a maturation‐specific regulation network that was not recognized previously. Second, we showed genetic disruption of Orai3 results in severe myofilament disarray that impacted both sarcomere structure and mitochondrial maturation. Third, we reported that the STIM1/Orai3 mediated Ca2+‐entry is independent of, and coexists with, the EC‐coupling Ca2+ machinery. Fourth, loss of Orai3 causes abnormalities of intracellular Ca2+ handling resulting in calcineurin signaling cascade activation with detrimental effects on cell survival, cell structure, mitochondrial morphology.

The new information acquired in this study provides potential guidance to improve cellular structural stability and metabolic demands. For example, sarcomere disarray is a typical phenotype observed in various clinical settings, including hypertrophic and DCMs. Furthermore, muscle cytoarchitecture is organized to promote efficient communication between mitochondria, endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum, and sarcomeres, cytoarchitectural perturbations could promote energetic dysfunction. 42 This indicates that processes which regulate sarcomere organization are likely to be key mechanisms whose manipulation can improve functional integrity of the sarcomere and energy transfer.

We found that Orai3 is the main isoform expressed in the adult mouse cardiomyocyte, while Orai1 and Orai2 proteins were undetectable. In contrast, NRCMs express high levels of Orai1 and STIM1 with low levels of Orai2 and Orai3 protein. RNA‐Seq transcriptomic of developmental changes in Orai3 expression across 4 developmental stages in rats agree with our results. 43 Furthermore, many laboratories showed undetectable Orai1 and Orai2 proteins expression in the adult mouse myocardium. 12 , 13 Our findings are in line with the absence of a cardiac phenotype in patients with loss‐of‐function mutations in Orai1 and with a recently described cardiac‐specific Orai1 knockout mouse, which lacks a cardiac phenotype under normal conditions and shows no protection against pathological cardiac hypertrophy. 21 However, it is still possible that low levels of Orai1 protein is expressed in the adult mouse cardiomyocytes and that may interact with Orai3 to form heterodimers that may or may not require STIM1 activation and are sensitive to arachidonic acid. 44 , 45 Previous studies in non‐excitable cells showed that Orai3 channel activity is significantly weaker than Orai1 and that Orai3 can heterodimerize with Orai1 to dampen the activity of store‐operated Ca2+ entry. 46 Therefore, it can be argued that the weaker activity of Orai3 channels is better suitable to coexist with the EC‐coupling in cardiomyocytes. Further studies are needed to shed light on the biological reason for these findings.

Orai3 downregulation achieved by pharmacological treatment or siRNA results in accelerated HF. 24 Here, we used novel constitutive and inducible Orai3cKO animal models as our key strategy. These models generated new information that significantly updated our previous understanding of the role of Orai3 in cardiomyocytes. For example, we demonstrate that Orai3 is necessary for adult cardiac homeostasis and its deletion causes DCM similarly to invertebrates lacking Orai1, further supporting the idea that Orai3 likely substitutes for Orai1 in the mammalian adult heart.

Our data suggest an increase of TRPC6 expression in Orai3cKO mice. This can be a compensatory response to the loss of Orai3. Indeed, Orai channels coexist with TRPC channels, and they affect each other’s function and expression. 47 Furthermore, TRPC6, 3 and 1 have been linked to cardiac remodeling through activation of calcineurin. 48 In our case, TRPC6 upregulation could provide enough Ca2+ entry to activate calcineurin and its downstream target, RCAN‐1 (regulator of calcineurin 1). Similar to our results, in zebrafish, Orai1‐loss also resulted in calcineurin over‐activation. 37 However, intracellular Ca2+ overload because of alteration of SERCA and NCX could contribute to RCAN‐1 activation. Further investigation will have to clarify these modalities in cardiomyocytes.

Orai3 genetic deletion from cardiomyocytes results in mitochondrial dysfunction and elevated apoptosis in the Orai3‐null myocardium. Indeed, constitutive rise in intracellular Ca2+ activates calcineurin, which induces dephosphorylation and translocation of DRP1, triggering exaggerated mitochondrial fission, mitochondrial fragmentation, and loss of ΔΨm, known hallmark of early apoptosis, 49 and are consistent with our findings. Interestingly, disorders in the mitochondrial organization and the presence of abnormally small and fragmented mitochondria have been observed in end‐stage human DCM, myocardial hibernation, and ventricular‐associated congenital heart disease. 50

We show, for the first time, that in NRCM, STIM1/Orai3 microdomain can trigger Ca2+ entry that is distinct from the global intracellular Ca2+ transient observed during the EC‐coupling. Such microdomains coexist with the global Ca2+ transients in electrically paced NRCMs. Remarkably, despite a dramatic rise in local Ca2+ in correspondence with STIM/Orai3 domains, the signal remained spatially constrained without affecting the global Ca2+ transient. These findings concur with previous observations that in cardiac and skeletal muscle, STIM1 clusters independently of the endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ load. 12 , 25 , 51 We show an unprecedented phenomenon of STIM1/Orai3 channel activation, where only a few of the STIM/Orai clusters trigger Ca2+‐entry in NRCMs. Although we show that Orai3 is activated by intracellular Ca2+ store depletion, the mechanisms leading to Orai3‐mediated Ca2+ entry in cardiomyocytes need to be further elucidated.

Altogether, these data suggest that Orai3‐signaling is involved in the regulation gene transcription program that maintain sarcomere integrity and plays an important role in cellular energy balance as well as in stress response to pressure‐induced cardiac stress. Future studies should be conducted to explore the potential for Orai3 as a therapeutic target for patients with HF.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the intramural department funds and by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant number HL114869, HL153638, and HL142631 to Dr Mancarella).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Video S1

Figures S1–S5

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Janith Halpage for his technical assistance and animal colony management.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e019486. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.019486.)

Supplementary Materials for this article are available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.120.019486

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 14.

References

- 1. Graham RM, Owens WA. Pathogenesis of inherited forms of dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1759–1762. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:531–547. DOI: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arguin G, Caron AZ, Elkoreh G, Denault JB, Guillemette G. The transcription factors NFAT and CREB have different susceptibilities to the reduced Ca2+ responses caused by the knock down of inositol trisphosphate receptor in HEK 293A cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;26:629–640. DOI: 10.1159/000322330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Judge DP. Use of genetics in the clinical evaluation of cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2009;302:2471–2476. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2009.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Petersen CE, Wolf MJ, Smyth JT. Suppression of store‐operated calcium entry causes dilated cardiomyopathy of the drosophila heart. Biol Open. 2020;9:bio049999. DOI: 10.1242/bio.049999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Völkers M, Dolatabadi N, Gude N, Most P, Sussman MA, Hassel D. Orai1 deficiency leads to heart failure and skeletal myopathy in zebrafish. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:287–294. DOI: 10.1242/jcs.090464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Soboloff J, Spassova MA, Tang XD, Hewavitharana T, Xu W, Gill DL. Orai1 and STIM reconstitute store‐operated calcium channel function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20661–20665. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.C600126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mancarella S, Wang Y, Gill DL. Calcium signals: STIM dynamics mediate spatially unique oscillations. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R950–R952. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Store‐operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:1383–1436. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trebak M, Kinet JP. Calcium signalling in T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:154–169. DOI: 10.1038/s41577-018-0110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCarl C‐A, Picard C, Khalil S, Kawasaki T, Röther J, Papolos A, Kutok J, Hivroz C, LeDeist F, Plogmann K, et al. Orai1 deficiency and lack of store‐operated Ca2+ entry cause immunodeficiency, myopathy, and ectodermal dysplasia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1311–1318.e1317. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao G, Li T, Brochet DX, Rosenberg PB, Lederer WJ. STIM1 enhances SR Ca2+ content through binding phospholamban in rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E4792–E4801. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1423295112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Oh‐hora M, Hogan PG, Lamperti ED, Yamashita M, Gelinas C, Neems DS, Sasaki Y, Feske S, et al. Hair loss and defective T‐ and B‐cell function in mice lacking ORAI1. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5209–5222. DOI: 10.1128/MCB.00360-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Troupes CD, Wallner M, Borghetti G, Zhang C, Mohsin S, von Lewinski D, Berretta RM, Kubo H, Chen X, Soboloff J, et al. Role of STIM1 (stromal interaction molecule 1) in hypertrophy‐related contractile dysfunction. Circ Res. 2017;121:125–136. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saliba Y, Keck M, Marchand A, Atassi F, Ouillé A, Cazorla O, Trebak M, Pavoine C, Lacampagne A, Hulot J‐S, et al. Emergence of Orai3 activity during cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;105:248–259. DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvu207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feske S, Picard C, Fischer A. Immunodeficiency due to mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1. Clin Immunol. 2010;135:169–182. DOI: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Voelkers M, Salz M, Herzog N, Frank D, Dolatabadi N, Frey N, Gude N, Friedrich O, Koch WJ, Katus HA, et al. Orai1 and Stim1 regulate normal and hypertrophic growth in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:1329–1334. DOI: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luo X, Hojayev B, Jiang N, Wang ZV, Tandan S, Rakalin A, Rothermel BA, Gillette TG, Hill JA. STIM1‐dependent store‐operated Ca(2)(+) entry is required for pathological cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:136–147. DOI: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ohba T, Watanabe H, Murakami M, Sato T, Ono K, Ito H. Essential role of stim1 in the development of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;389:172–176. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Horton JS, Buckley CL, Alvarez EM, Schorlemmer A, Stokes AJ. The calcium release‐activated calcium channel Orai1 represents a crucial component in hypertrophic compensation and the development of dilated cardiomyopathy. Channels. 2014;8:35–48. DOI: 10.4161/chan.26581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Segin S, Berlin M, Richter C, Medert R, Flockerzi V, Worley P, Freichel M, Camacho Londoño JE. Cardiomyocyte‐specific deletion of Orai1 reveals its protective role in angiotensin‐II‐induced pathological cardiac remodeling. Cells. 2020;9:1092. DOI: 10.3390/cells9051092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan‐Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, et al. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store‐operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006;312:1220–1223. DOI: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cai X. Molecular evolution and structural analysis of the Ca(2+) release‐activated Ca(2+) channel subunit, Orai. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:1284–1291. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keck M, Flamant M, Mougenot N, Favier S, Atassi F, Barbier C, Nadaud S, Lompré A‐M, Hulot J‐S, Pavoine C, et al. Cardiac inflammatory CD11B/c cells exert a protective role in hypertrophied cardiomyocyte by promoting TNFR2‐ and Orai3‐ dependent signaling. Sci Rep. 2019;9:6047. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-42452-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parks C, Alam MA, Sullivan R, Mancarella S. STIM1‐dependent Ca(2+) microdomains are required for myofilament remodeling and signaling in the heart. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25372. DOI: 10.1038/srep25372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li X, Matta SM, Sullivan RD, Bahouth SW. Carvedilol reverses cardiac insufficiency in AKAP5 knockout mice by normalizing the activities of calcineurin and CAMKII. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;104:270–279. DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvu209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kamatham S, Waters CM, Schwingshackl A, Mancarella S. TREK‐1 protects the heart against ischemia‐reperfusion‐induced injury and from adverse remodeling after myocardial infarction. Pflugers Arch. 2019;471:1263–1272. DOI: 10.1007/s00424-019-02306-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yeap XY, Dehn S, Adelman J, Lipsitz J, Thorp EB. Quantitation of acute necrosis after experimental myocardial infarction. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1004:115–133. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-62703-383-1_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karnabi E, Qu Y, Mancarella S, Yue Y, Wadgaonkar R, Boutjdir M. Silencing of Cav1.2 gene in neonatal cardiomyocytes by lentiviral delivered shRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384:409–414. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dynes JL, Amcheslavsky A, Cahalan MD. Genetically targeted single‐channel optical recording reveals multiple Orai1 gating states and oscillations in calcium influx. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:440–445. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1523410113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mancarella S, Yue Y, Karnabi E, Qu Y, El‐Sherif N, Boutjdir M. Impaired Ca2+ homeostasis is associated with atrial fibrillation in the alpha1D L‐type Ca2+ channel KO mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2017–H2024. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00537.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lehnart SE, Terrenoire C, Reiken S, Wehrens XHT, Song L‐S, Tillman EJ, Mancarella S, Coromilas J, Lederer WJ, Kass RS, et al. Stabilization of cardiac ryanodine receptor prevents intracellular calcium leak and arrhythmias. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7906–7910. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0602133103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gregory RB, Rychkov G, Barritt GJ. Evidence that 2‐aminoethyl diphenylborate is a novel inhibitor of store‐operated Ca2+ channels in liver cells, and acts through a mechanism which does not involve inositol trisphosphate receptors. Biochem J. 2001;354:285–290. DOI: 10.1042/bj3540285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hulot J‐S, Fauconnier J, Ramanujam D, Chaanine A, Aubart F, Sassi Y, Merkle S, Cazorla O, Ouillé A, Dupuis M, et al. Critical role for stromal interaction molecule 1 in cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2011;124:796–805. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.031229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gao X, Liu W, Huang L, Zhang T, Mei Z, Wang X, Gong J, Zhao Y, Xie F, Ma J, et al. HSP70 inhibits stress‐induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by competitively binding to FAF1. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2015;20:653–661. DOI: 10.1007/s12192-015-0589-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pan S, Zhao X, Wang XU, Tian X, Wang Y, Fan R, Feng NA, Zhang S, Gu X, Jia M, et al. Sfrp1 attenuates TAC‐induced cardiac dysfunction by inhibiting wnt signaling pathway‐ mediated myocardial apoptosis in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17:202. DOI: 10.1186/s12944-018-0832-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Volkers M, Dolatabadi N, Gude N, Most P, Sussman MA, Hassel D. Orai1 deficiency leads to heart failure and skeletal myopathy in zebrafish. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:287–294. DOI: 10.1242/jcs.090464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goldfarb LG, Dalakas MC. Tragedy in a heartbeat: malfunctioning desmin causes skeletal and cardiac muscle disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1806–1813. DOI: 10.1172/JCI38027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kostareva A, Sjöberg G, Bruton J, Zhang S‐J, Balogh J, Gudkova A, Hedberg B, Edström L, Westerblad H, Sejersen T, et al. Mice expressing L345P mutant desmin exhibit morphological and functional changes of skeletal and cardiac mitochondria. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2008;29:25–36. DOI: 10.1007/s10974-008-9139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sohal DS, Nghiem M, Crackower MA, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Tymitz KM, Penninger JM, Molkentin JD. Temporally regulated and tissue‐specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen‐inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001;89:20–25. DOI: 10.1161/hh1301.092687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bartoli F, Bailey MA, Rode B, Mateo P, Antigny F, Bedouet K, Gerbaud P, Gosain R, Plante J, Norman K, et al. Orai1 channel inhibition preserves left ventricular systolic function and normal Ca(2+) handling after pressure overload. Circulation. 2020;141:199–216. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saks VA, Kaambre T, Sikk P, Eimre M, Orlova E, Paju K, Piirsoo A, Appaix F, Kay L, Regitz‐zagrosek V, et al. Intracellular energetic units in red muscle cells. Biochem J. 2001;356:643–657. DOI: 10.1042/bj3560643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yu Y, Fuscoe JC, Zhao C, Guo C, Jia M, Qing T, Bannon DI, Lancashire L, Bao W, Du T, et al. A rat RNA‐Seq transcriptomic BodyMap across 11 organs and 4 developmental stages. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3230. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. The molecular architecture of the arachidonate‐regulated Ca2+‐selective ARC channel is a pentameric assembly of Orai1 and Orai3 subunits. J Physiol. 2009;587:4181–4197. DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shuttleworth TJ. Orai3–the 'exceptional' orai? J Physiol. 2012;590:241–257. DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.220574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yoast RE, Emrich SM, Zhang X, Xin P, Johnson MT, Fike AJ, Walter V, Hempel N, Yule DI, Sneyd J, et al. The native ORAI channel trio underlies the diversity of Ca(2+) signaling events. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2444. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-16232-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lopez JJ, Jardin I, Sanchez‐Collado J, Salido GM, Smani T, Rosado JA. TRPC channels in the SOCE scenario. Cells. 2020;9:126. DOI: 10.3390/cells9010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nakayama H, Wilkin BJ, Bodi I, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin‐dependent cardiomyopathy is activated by TRPC in the adult mouse heart. FASEB J. 2006;20:1660–1670. DOI: 10.1096/fj.05-5560com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, Martins de Brito O, Chang CR, Blackstone C, Bernardi P, Scorrano L. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15803–15808. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0808249105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hom J, Yu T, Yoon Y, Porter G, Sheu SS. Regulation of mitochondrial fission by intracellular Ca2+ in rat ventricular myocytes. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:913–921. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Launikonis BS, Rios E. Store‐operated Ca2+ entry during intracellular Ca2+ release in mammalian skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2007;583:81–97. DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video S1

Figures S1–S5

Data Availability Statement

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available on request to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedures reported here.