Abstract

Objectives

To assess the acceptability of neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) of the quadriceps muscles in people with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and to identify whether a future definitive trial is feasible.

Design

A randomised, parallel, two-group, participant and assessor-blinded, placebo-controlled feasibility trial with embedded qualitative interviews.

Setting

Outpatient department, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals.

Participants

Twenty-two people with IPF: median (25th, 75th centiles) age 76 (74, 82) years, forced vital capacity 62 (50, 75) % predicted, 6 min walk test distance 289 (149, 360) m.

Interventions

Usual care (home-based exercise, weekly telephone support, breathlessness management leaflet) with either placebo or active NMES for 6 weeks, with follow-up at 6 and 12 weeks.

Primary outcome measures

Feasibility of recruitment and retention, treatment uptake and adherence, outcome assessments, participant and outcome assessor blinding and adverse events related to interventions.

Secondary outcome measures

Outcome measures with potential to be primary or secondary outcomes in a definitive clinical trial. In addition, purposively sampled participants were interviewed to capture their experiences and acceptability of the trial.

Results

Out of 364 people screened, 23 were recruited: 11 were allocated to each group and one was withdrawn prior to randomisation. Compared with the control group, a greater proportion of the intervention group completed the intervention, remained in the trial blinded to group allocation and experienced intervention-related adverse events. Assessor blinding was maintained. The secondary outcome measures were feasible with most missing data associated with the accelerometer. Small participant numbers precluded identification of an outcome measure suitable for a definitive trial. Qualitative findings demonstrated that trial process and active NMES were acceptable but there were concerns about the credibility of placebo NMES.

Conclusions

Primarily owing to recruitment difficulties, a definitive trial using the current protocol to evaluate NMES in people with IPF is not feasible.

Trial registration number

Keywords: interstitial lung disease, rehabilitation medicine, respiratory medicine (see thoracic medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to examine the feasibility of neuromuscular electrical stimulation in people with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The intervention was developed using a combination of patient and public involvement feedback and previously published studies.

We blinded the outcome assessor to group allocation and used an existing placebo neuromuscular electrical stimulator device to blind participants in the control group.

We conducted qualitative interviews to capture participant experiences.

The study took place at a single site and may have been a limiting factor for participant recruitment.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is characterised by progressive dyspnoea, reduction in functional capacity and subsequent loss of independence.1 2 Several factors contribute to this, including declining lung function and peripheral muscle weakness.3 There is growing interest in the latter, as it is known that people with IPF have smaller rectus femoris cross-sectional area4 as well as reduced quadriceps strength3–5 and endurance5 compared with matched healthy controls.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends regular assessment for and offering pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) to people with IPF.6 However, people with advanced disease and severe breathlessness may have difficulties undertaking PR as ventilatory limitation may preclude effective whole body training.7 Centre-based PR or exercise programme completion rates range from 43%8 to 94%.9 People with more severe disease and those unwilling to participate in group programmes are less likely to complete these programmes.10 Accordingly, home-based ways of conferring the benefits of exercise are required.

Guidance from NICE states that in people not suitable for, or unable to participate in, existing rehabilitation programmes, neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) of the quadriceps offers an alternative means of enhancing muscle strength.11 NMES uses a small battery-operated stimulator which, via surface electrodes placed on the anterior thigh, produces a controlled contraction and relaxation of the underlying muscles. It is safe, relatively inexpensive and is performed seated at home. In people with advanced chronic disease including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure and cancer, a meta-analysis demonstrated that compared with placebo, NMES led to a significant improvement in quadriceps strength, muscle mass and exercise capacity.12 Therefore, NMES may be a potential treatment for muscle weakness in advanced progressive disease and could be considered a suitable home intervention for people with muscle weakness who have difficulty engaging with existing PR services.11 12 To date, there are no published studies exploring the role or effects of NMES in IPF, although there is one small randomised controlled trial (n=30) comparing active NMES plus aerobic exercise to placebo NMES plus aerobic exercise that is currently recruiting people with IPF (NCT03890250). Therefore, we aimed to determine the acceptability of NMES of the quadriceps in people with IPF and to identify whether a future definitive trial is feasible.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a randomised, parallel, two-group, participant and assessor-blinded, placebo-controlled feasibility trial with embedded qualitative interviews. The trial was conducted and reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials.13 Participants were recruited from outpatient clinics at the Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, UK, between November 2018 and February 2020. The inclusion criteria were (1) diagnosis of IPF according to international guidelines,14 (2) Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea score ≥3, (3) quadriceps maximum voluntary contraction (QMVC) <80% predicted,15 (4) declined or failed to complete supervised centre-based PR, and (5) ability to provide informed consent. People were excluded for the following reasons: (1) cardiac pacemaker, (2) coexisting neurological condition, for example, lower limb paralysis, (3) completion of PR within the previous 6 months, (4) change in medication and/or exacerbation requiring hospitalisation within the previous 4 weeks, or (5) current regular exerciser (structured exercise ≥3/week in the previous month). All participants provided written informed consent. The trial was pre-registered on ClinicalTrials.gov.

Randomisation and blinding

Following baseline assessment, participants were randomly allocated 1:1 at the individual level to receive active or placebo NMES. Minimisation was used to balance groups for age (<65 years vs ≥65 years), sex (male vs female) and quadriceps strength (<20 kg vs ≥20 kg). The allocation sequence was generated using an independent web-based randomisation system within the UK Clinical Research Collaboration-registered King’s Clinical Trials Unit. Following randomisation, the Clinical Trials Unit informed trial staff by secure email. An unblinded researcher selected an active or placebo device accordingly. Blinded researchers were informed of trial entry but not group allocation. The participant was not informed of group allocation. Subsequent assessment visits were completed immediately after the 6-week intervention period and at 12 weeks by a researcher blinded to group allocation. Qualitative in-depth, topic-guided interviews were completed in a subgroup of participants who were selected purposively to include both intervention and control groups, sexes and a range of baseline MRC scores so that different perspectives could be explored.

Interventions

The treating healthcare professionals provided potential participants with the study information leaflet who were then screened by the research team via telephone. Those interested in participating in the study attended an assessment to confirm eligibility.

The interventions were based on a combination of patient and public involvement (PPI) feedback and published studies.16 The NMES programme was a self-administered, home-based protocol involving 30 min stimulation of bilateral quadriceps muscles for 6 weeks. The active device was KneeHab XP (Neurotech, USA) and the placebo device was MicroStim Exercise Stimulator MS2v2 (Odstock Medical, UK). Although different machines were used for the active and placebo devices, they were outwardly identical as both were covered in the same garment (online supplemental file). The parameters of both devices were the same (frequency 50 Hz, pulse width 400 μs, duty cycle 18%–33% which increased weekly for the first 3 weeks) except for the amplitude range (active: 0–120 mA; placebo: 0–20 mA). Consequently, participants in the control group received sensory feedback during stimulation but the device did not elicit a tetanic muscle contraction.

bmjopen-2021-048808supp001.pdf (167.1KB, pdf)

Participants in both groups also received a leaflet on how to manage breathlessness and an individualised home exercise programme supplemented with a manual which they were instructed to perform at least three times per week (online supplemental file).

The unblinded researcher delivered a standardised 40 min training session to participants in both groups to demonstrate and supervise NMES application and the home exercise programme. Participants were provided with a diary to record NMES and exercise performance. During the 6-week intervention period, the unblinded researcher telephoned participants weekly to review and progress NMES use and home exercise performance. To progress NMES, participants were asked to increase the amplitude of the electrical current, within the limits of the device.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcomes were related to feasibility: participant recruitment and retention, treatment uptake and adherence, feasibility of outcome assessments, feasibility of participant and assessor blinding and adverse events related to the interventions. To assess recruitment and retention-related feasibility outcomes, the numbers of potential eligible participants as well as recruitment and retention rates at the 6 and 12-week assessments were recorded. To assess treatment uptake and adherence, the following were recorded: feasibility, outcomes, rates of uptake of and adherence to the allocated intervention and frequency and time spent using the NMES device and performing the home exercise programme. Feasibility of outcome assessment was measured by recording the amount of missing data for each outcome measure at each assessment. Participant and assessor blinding was assessed by the unblinded researcher at the 6-week assessment, and 6 and 12-week assessments, respectively. Research staff recorded adverse events during assessment visits and weekly telephone calls. These were classified as related or unrelated to the allocated intervention using as much information as available to determine the potential attribution of the event.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures were those that had the potential to be primary or secondary outcomes in a definitive clinical trial. These were: exercise capacity (6 min walk test),17 functional performance (Short Physical Performance Battery),18 4 m gait speed,19 rectus femoris size (ultrasound of rectus femoris cross-sectional area (Mindray DP-50, Caiyside Imaging, Scotland)), quadriceps strength (isometric QMVC),20 health-related quality of life (King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease questionnaire),21 activities of daily living (London Chest Activities of Daily Living questionnaire)22 and physical activity parameters (daily step count, time spent sedentary, light and moderate-intensity activity (SenseWear, BodyMedia, USA)).23

Following the 12-week assessment, purposively sampled participants were invited to take part in semistructured, topic-guided, telephone-based interviews. The audio-recorded interviews explored experiences of the intervention, how it impacted perceptions of outcome, acceptability of outcome measures and trial conduct in order to inform the rationale for and conduct of a definitive trial. The topic guides were updated inductively to reflect experiences and perceptions raised during previous interviews.

Sample size

Sample size estimation was performed to achieve the primary feasibility outcomes, and not to detect differences in the secondary outcome measures. Based on guidance in the literature, we estimated that a sample size of 60 (30 per group) would be sufficient to adequately evaluate the feasibility of undertaking a definitive trial. A sample size of 10 was chosen for the qualitative interviews as it was based on the predicted minimum number of interviews required to achieve data saturation and is based on the concept of information power.24

Statistical analysis

The feasibility outcomes and baseline demographics were described and summarised overall and by trial group using proportions (percentage) or median (25th, 75th centiles). The baseline data and change at 6 and 12 weeks were reported as median (25th, 75th centiles) or median (25th, 75th centiles) change for each trial group.

Anonymised interview transcripts were transcribed verbatim and imported into NVivo (QSR International, Australia) to facilitate analysis using the framework method.25 The coding frame was predefined and included experiences of the interventions, impact of intervention on perceived outcome, acceptability and experiences of trial conduct and acceptability of the outcome measures. During indexing, secondary codes were inductively applied. A mixed methods matrix26 of qualitative and key quantitative data was used to illuminate barriers and facilitators for intervention completion by participants to inform protocol adaptation and/or optimisation.

Patient and public involvement

This research has included PPI throughout each stage. Two PPI representatives were involved in the design of the study and intervention and met the project manager at regular intervals throughout the study. The PPI representatives also provided input into written material for participants and topic guides for qualitative interviews. Going forward, they will have a role in dissemination of research findings to lay audiences.

Results

Primary outcome

Feasibility of recruitment and retention

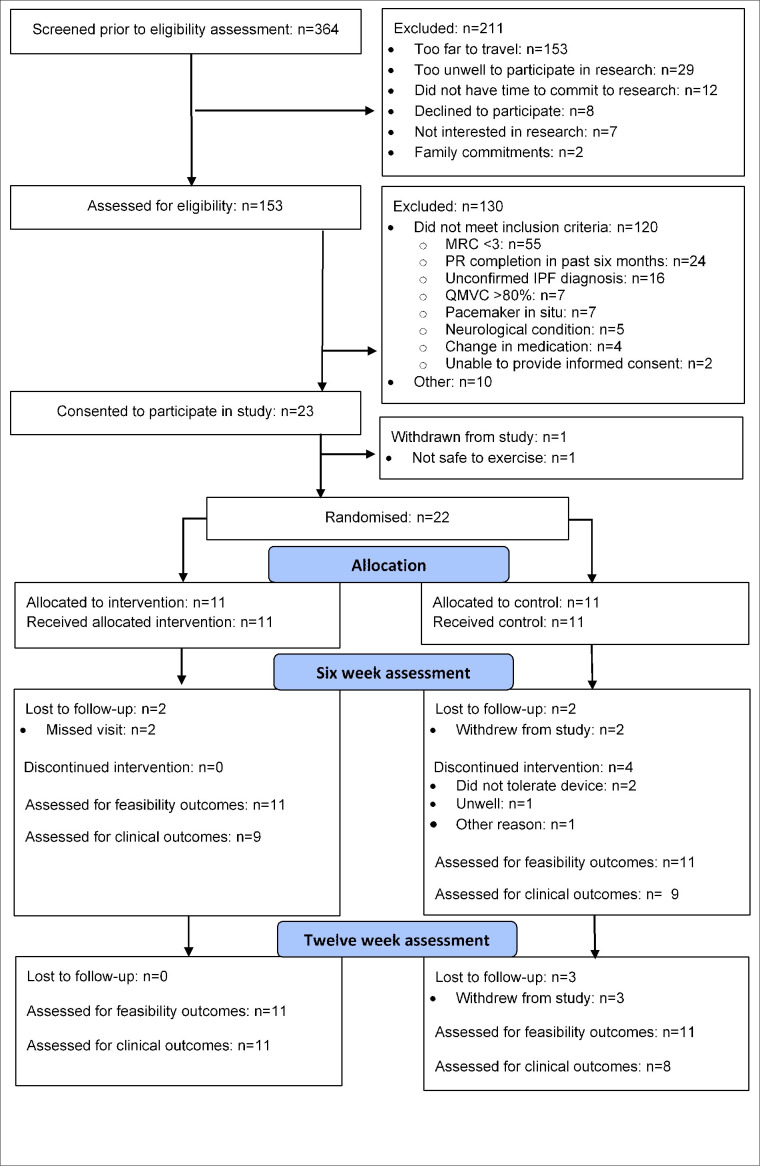

We screened 364 people, of whom 153 were assessed for eligibility and 23 consented to participate in the study: 11 were allocated to both the intervention and control groups and one was withdrawn prior to randomisation for safety reasons (figure 1). By far, the most common reason for failing the telephone-based screening assessment was the distance participants were required to travel to the research centre (n=153). MRC<3 (n=55) or PR completion within 6 months (n=24) were the most common reasons for failing the eligibility assessment. At the 6-week assessment, two participants in both groups were lost to follow-up (intervention: n=2 missed visit, control: n=2 withdrew from the study). At the 12-week assessment, all participants in the intervention group were assessed whereas three participants in the control group were lost to follow-up (withdrew from the study).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; MRC, Medical Research Council; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation; QMVC, quadriceps maximum voluntary contraction.

Feasibility of treatment uptake and adherence

All participants started their allocated intervention. Both groups received the same median number of weekly telephone calls but there was a trend for higher frequency and duration of use of the NMES device and home exercise programme in the intervention compared with the control group (table 1). All participants in the intervention group completed the allocated intervention. In contrast, four participants in the control group discontinued the intervention: n=2 did not tolerate placebo NMES, n=1 unwell, n=1 felt NMES was ineffective.

Table 1.

Intervention uptake, adherence and completion

| Variable | Intervention | Control |

| Number of weekly telephone calls | 6 (5, 6) | 6 (4, 6) |

| Number of times device* used between V1 and V2 | 31 (22, 44) | 24 (4, 40) |

| Total minutes device* used between V1 and V2 | 930 (660, 1110) | 570 (120, 1230) |

| Number of times HEP performed between V1 and V2 | 20 (17, 32) | 14 (4, 26) |

| Total minutes HEP performed between V1 and V2 | 906 (600, 1527) | 648 (110, 1399) |

Data reported number or median (25th, 75th) centile.

*Device: intervention group: active stimulator; control group: placebo stimulator.

HEP, home exercise programme; V, visit.

Feasibility of outcome assessment

Missing data for each clinical outcome according to assessment time point are described in the online supplemental file. There were no missing data at the baseline assessment. Missing data at the 6 and 12-week assessments mostly related to participants that were lost to follow-up. The outcome measures with the most missing data were the physical activity parameters (intervention, control: baseline: n=4, n=4; 6 and 12 weeks: n=5, n=6). Reasons for missingness included participants declining to wear the device and insufficient data to analyse.

Feasibility of participant and outcome assessor blinding

Participant blinding was maintained in the intervention group but three participants in the control group were unblinded as they did not believe the placebo NMES was credible. The outcome assessor remained blinded to intervention allocation of all participants.

Adverse and serious adverse events

There was one serious adverse event in the intervention group and four in the control group. None of these events were unexpected or related to the allocated intervention or assessments. One participant experienced two adverse events prior to randomisation. A total of 10 and five adverse events in the intervention and control groups were experienced by eight and four participants, respectively. None of the events prior to randomisation or in the control group were unexpected or related to the study. Three adverse events in the intervention group were expected and related to the study. These included redness on anterior thigh and itchiness on anterior thigh following NMES use as well as ‘burning sensation’ on anterior thigh during NMES use. The remaining seven adverse events were expected and unrelated to the intervention.

Secondary outcomes

The groups were balanced in terms of age, gender, absolute and relative forced vital capacity values, body mass index and quadriceps strength (table 2). However, compared with the intervention group, the control group had a greater proportion of participants diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, prescribed supplementary oxygen and corticosteroid, former smokers and worse absolute and relative diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) values, exercise capacity, activities of daily life performance, walking speed and physical activity levels. Due to the small number of participants in each group, it was not possible to test for between-group differences.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

| Whole group (n=22) | Intervention (n=11) | Control (n=11) | |

| Gender: male (%) | 16 (73) | 7 (64) | 8 (73) |

| Age (years) | 76 (74, 82) | 77 (73, 81) | 76 (74, 84) |

| MRC dyspnoea score | 4 (4, 4) | 4 (4, 4) | 4 (4, 4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.4 (22.4, 29.1) | 24.2 (22.0, 26.5) | 25.2 (22.6, 29.2) |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.84 (0.78, 0,86) | 0.80 (0.77, 0,85) | 0.84 (0.78, 0,87) |

| FVC (L) | 1.83 (1.39, 2.44) | 1.83 (1.44, 2.45) | 1.82 (1.22, 2.44) |

| FVC (% predicted) | 61.8 (49.8, 75.0) | 63.0 (49.0, 78.2) | 60.5 (50.0, 68.0) |

| DLCO (mL/min/mm Hg) | 2.16 (1.71, 2.77) | 2.50 (1.92, 3.36) | 1.88 (1.64, 2.20) |

| DLCO (% predicted) | 26.0 (21.9, 36.7) | 36.5 (22.3, 40.4) | 25.0 (20.8, 29.8) |

| Smoking status: never/former/current (%) | 13 (59)/9 (41)/0 (0) | 7 (64)/4 (36)/0 (0) | 6 (55)/5 (45)/0 (0) |

| Smoking pack-year history | 0 (0, 8) | 0 (0, 5) | 0 (0, 13) |

| Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2 (0, 5) | 4 (0, 5) | 0 (0, 6) |

| COPD, n (%) | 3 (14) | 1 (10) | 2 (18) |

| Pulmonary hypertension, n (%) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (18) |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 8 (36) | 5 (46) | 3 (27) |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Self-reported hospitalisations in previous year, n (%) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) |

| Self-reported chest infections in previous year, n (%) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 1) |

| Oxygen, n (%) | |||

| Long term | 4 (18) | 1 (10) | 3 (27) |

| Ambulatory | 9 (41) | 4 (36) | 5 (46) |

| Walking aid, n (%) | 5 (23) | 2 (18) | 3 (27) |

| Prescribed pirfenidone, n (%) | 6 (27) | 4 (36) | 2 (18) |

| Prescribed nintedanib, n (%) | 7 (32) | 4 (36) | 3 (27) |

| Prescribed corticosteroid, n (%) | 4 (18) | 3 (27) | 1 (9) |

| 6MWT (m) | 289 (149, 360) | 326 (150, 361) | 240 (130, 325) |

| SPPB score | 9 (6, 11) | 10 (6, 11) | 7 (4, 11) |

| Four-metre gait speed (m/s) | 0.71 (0.50, 0.94) | 0.82 (0.38, 0.97) | 0.66 (0.51, 0.84) |

| QMVC (kg) | 22.4 (15.6, 28.7) | 22.5 (15.1, 28.3) | 22.4 (15.7, 31.3) |

| QMVC (% predicted) | 62.4 (52.0, 69.1) | 64.3 (44.0, 68.1) | 61.6 (52.8, 72.2) |

| Rectus femoris cross-sectional area (mm2) | 459 (371, 534) | 451 (321, 579) | 479 (375, 581) |

| KBILD—psychological | 54.4 (53.2, 69.1) | 58.8 (41.2, 71.6) | 53.5 (43.8, 65.5) |

| KBILD—breathlessness and activities | 35.6 (21.6, 45.9) | 37.8 (27.0, 50.2) | 35.6 (17.7, 41.9) |

| KBILD—chest symptoms | 68.6 (44.0, 85.2) | 63.7 (44.0, 85.2) | 73.4 (54.3, 85.2) |

| KBILD—total score | 53.5 (46.4, 59.4) | 56.1 (43.9, 66.4) | 53.5 (47.2, 56.1) |

| LCADL—self-care | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 7.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 7.0) |

| LCADL—domestic | 10.5 (4.8, 18.5) | 5.0 (1.0, 17.0) | 14.0 (10.0, 22.0) |

| LCADL—physical | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) |

| LCADL—leisure | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) |

| LCADL—total score | 26.0 (17.5, 37.3) | 20.0 (14.0, 28.0) | 33.0 (22.0, 29.0) |

| Daily step count | 1511 (776, 3456) | 1820 (1148, 3232) | 988 (657, 4115) |

| Daily minutes spent in moderate-intensity PA | 34 (20, 84) | 47 (25, 100) | 22 (5, 74) |

| Daily minutes spent in light-intensity PA | 194 (147, 221) | 217 (126, 248) | 187 (153, 199) |

| Daily minutes spent sedentary | 1144 (1098, 1206) | 1123 (1095, 1151) | 1194 (1137, 1237) |

Data reported as number (percentage) or median (25th centile, 75th centile).

KBILD domains and total score: range 0–100; higher scores indicate better health-related quality of life.

LCADL range: self-care: 0–20; domestic: 0–30; physical: 0–10; leisure: 0–15; total: 0–75; higher scores indicate greater impact on activities of daily living (ADL) performance.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; KBILD, King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease questionnaire; LCADL, London Chest Activities of Daily Living questionnaire; MRC, Medical Research Council; 6MWT, 6 min walk test; PA, physical activity; QMVC, quadriceps maximum voluntary contraction; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

The response to the intervention between baseline and 6-week assessment, and baseline and 12-week assessment is shown in tables 3 and 4, respectively. Again, owing to the small numbers of participants, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions from these data. However, between the baseline and 6-week assessment, there was a trend for a greater reduction in sedentary time in the intervention group, compared with an increase in sedentary time in the control group (table 3). Similarly, between the baseline and 12-week assessment, there was a trend for a greater increase in rectus femoris cross-sectional area, self-care related to activities of daily living performance and time spent in light-intensity physical activity in the intervention compared with the control group (table 4).

Table 3.

Within-group and between-group responses of the secondary outcome measures to the intervention from visit 1 to visit 2

| Outcome | Intervention | Control | ||

| n | Within-group difference | n | Within-group difference | |

| ∆ 6MWT (m) | 9 | 6 (−16, 45) | 8 | −17 (−74, 4) |

| ∆ SPPB | 9 | 0 (−1, 1) | 8 | 0 (0, 0) |

| ∆ Four-metre gait speed (m/s) | 9 | 0.03 (0.01, 0.06) | 8 | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.03) |

| ∆ QMVC (kg) | 9 | −0.1 (−1.9, 2.5) | 8 | −0.2 (−1.7, 2.0) |

| ∆ Rectus femoris cross-sectional area (mm2) | 9 | 18.0 (−32.6, 48.3) | 8 | 16.0 (−50.6, 33.0) |

| ∆ KBILD—psychological | 9 | 5.9 (−3.4, 12.8) | 9 | 0 (−7.2, 9.6) |

| ∆ KBILD—breathlessness and activities | 9 | 9.3 (−7.8, 13.8) | 9 | 0 (−8.4, 13.5) |

| ∆ KBILD—chest symptoms | 9 | 9.7 (−5.9, 16.7) | 9 | 9.7 (−5.9, 22.9) |

| ∆ KBILD—total score | 9 | 2.7 (−0.2, 7.4) | 9 | 0.1 (−2.2, 3.9) |

| ∆ LCADL—self-care | 9 | −1.0 (−2.0, 0.0) | 9 | 1.0 (−0.5, 1.5) |

| ∆ LCADL—domestic | 9 | 1.0 (−3.0, 4.5) | 9 | −1.0 (−3.0, −5.0) |

| ∆ LCADL—physical | 9 | 0.0 (−0.5, 0.5) | 9 | 0.0 (−1.0, 1.5) |

| ∆ LCADL—leisure | 9 | 0.0 (−1.0, 1.0) | 9 | 0.0 (−1.0, 1.5) |

| ∆ LCADL—total score | 9 | 0.0 (−5.0, 2.0) | 9 | 4.0 (−3.0, 10.0) |

| ∆ Daily step count | 5 | −270 (−504, 877) | 5 | −740 (−2026, −230) |

| ∆ Daily minutes spent in moderate-intensity PA | 5 | −3 (−20, 4) | 5 | −19 (−51, −5) |

| ∆ Daily minutes spent in light-intensity PA | 5 | 24 (5, 71) | 5 | −39 (−65, 15) |

| ∆ Daily minutes spent sedentary | 5 | −40 (−58, −21) | 5 | 54 (22, 86) |

Data reported as median (25th centile, 75th centile) difference.

KBILD domains and total score: range 0–100; higher scores indicate better health-related quality of life.

LCADL range: self-care: 0–20; domestic: 0–30; physical: 0–10; leisure: 0–15; total: 0–75; higher scores indicate greater impact on activities of daily living (ADL) performance.

KBILD, King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease questionnaire; LCADL, London Chest Activities of Daily Living questionnaire; 6MWT, 6 min walk test; PA, physical activity; QMVC, quadriceps maximum voluntary contraction; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Table 4.

Within-group and between-group responses of the secondary outcome measures to the intervention from visit 1 to visit 3

| Outcome | Intervention | Control | ||

| n | Within-group difference | n | Within-group difference | |

| ∆ 6MWT (m) | 10 | −13 (−73, −15) | 6 | −23 (−100, 18) |

| ∆ SPPB | 10 | 0 (−1, 0) | 7 | 0 (−1, 1) |

| ∆ Four-metre gait speed (m/s) | 10 | −0.03 (−0.14, 0.08) | 7 | 0.01 (−0.12, 0.09) |

| ∆ QMVC | 11 | 1.0 (−0.9, 4.3) | 7 | −1.7 (−3.4, 3.7) |

| ∆ Rectus femoris cross-sectional area (mm2) | 11 | 32.6 (2.5, 54.4) | 7 | −48.6 (−87.8, 10.0) |

| ∆ KBILD—psychological | 11 | 7.8 (4.6, 19.1) | 8 | 4.2 (−4.1, 8.7) |

| ∆ KBILD—breathlessness and activities | 11 | 9.3 (−7.5, 13.6) | 8 | 0 (−10.0, 5.9) |

| ∆ KBILD—chest symptoms | 11 | 10.3 (0, 19.7) | 8 | 10.8 (0, 24.9) |

| ∆ KBILD—total score | 11 | 5.4 (1.1, 8.8) | 8 | 2.6 (−4.1, 4.3) |

| ∆ LCADL—self-care | 11 | −1.0 (−2.0, 0.0) | 8 | 1.0 (0.3, 2.5) |

| ∆ LCADL—domestic | 11 | 1.0 (−1.0, 3.0) | 8 | 4.0 (−2.5, 9.5) |

| ∆ LCADL—physical | 11 | 0.0 (−1.0, 0.0) | 8 | 0.0 (−1.0, 1.8) |

| ∆ LCADL—leisure | 11 | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 8 | 0.5 (−0.8, 2.8) |

| ∆ LCADL—total score | 11 | 1.0 (−2.0, 5.0) | 8 | 4.5 (0.8, 15.3) |

| ∆ Daily step count | 5 | −215 (−966, 176) | 5 | −334 (−2712, 7) |

| ∆ Daily minutes spent in moderate-intensity PA | 5 | 2 (−29, 22) | 5 | 2 (−31, −11) |

| ∆ Daily minutes spent in light-intensity PA | 5 | 37 (−46, 54) | 5 | −3 (−61, 35) |

| ∆ Daily minutes spent sedentary | 5 | 8 (−29, 87) | 5 | 7 (−24, 50) |

Data reported as median (25th centile, 75th centile) difference.

KBILD domains and total score: range 0–100; higher scores indicate better health-related quality of life.

LCADL range: self-care: 0–20; domestic: 0–30; physical: 0–10; leisure: 0–15; total: 0–75; higher scores indicate greater impact on activities of daily living (ADL) performance.

KBILD, King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease questionnaire; LCADL, London Chest Activities of Daily Living questionnaire; 6MWT, 6 min walk test; PA, physical activity; QMVC, quadriceps maximum voluntary contraction; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Six participants (four male, two female), aged between 54 and 84 years, participated in the qualitative interviews. The majority had been allocated to the intervention group, with only one participant from the control group. Other participants allocated to the control group who were approached to take part in the interviews declined or were unable to take part because of illness or death. Despite interviewing almost one-third of participants who were recruited to the trial, new data were being gained up to and including the last interview.

All participants found the research staff, trial processes and outcome measures acceptable:

I was able to comply with what was required,…, other than the fact that the walking is limited, but at least I could rest. (Male, 80s, intervention group)

Most participants stated that the NMES device was feasible and acceptable:

The instructions were pretty straightforward, and once you have done it the first time,…, you just got it out of the bag and off you went. (Male, 80s, intervention group)

However, two participants reported negative NMES experiences:

It was a damn nuisance, to be perfectly frank,…, no, it was a bit of a performance and a bit of a nuisance. (Female, 70s, intervention group)

It was as if it was a placebo in place of the real thing,…, yes, I would say that it was the placebo, it wasn't the real thing. (Male, 70s, control group)

All participants reported that the exercise programme was feasible, acceptable and beneficial:

I’m still doing them, actually. It’s a good programme. (Female, 70s, intervention group)

However, maintaining motivation to complete the programme was difficult with one participant stating that he did so because it was part of the study:

I made sure I did the leg exercises [even when unwell] because that’s what I promised I would do. (Male, 60s, intervention group)

There was disparity in participants’ experience of the weekly telephone support during the 6-week intervention period. Some found it burdensome and suggested that digital monitoring would have been preferable:

That [provision of electronic version of home exercise programme] would have better. Yes, that would have been brilliant, and to then send it [diary reporting compliance and progress] back that way too. (Female, 70s, intervention group)

In contrast, other participants found it to be a positive experience and suggested more frequent monitoring would have been preferable:

I think once a week, or maybe twice a week would be a secondary call, if you did it on a Monday and then on a Friday. (Male, 60s, intervention group)

In addition, some participants reported that diary completion was difficult which affected their compliance with this tool:

I didn’t fill in the form right. I didn’t find the form very easy. I did it my own way. (Female, 70s, intervention group)

Discussion

We aimed to determine the acceptability of NMES of the quadriceps muscles in people with IPF and identify whether a future definitive trial is feasible. The qualitative interviews suggest that participants found the trial process, active NMES device and home exercise programme acceptable, but there were concerns about the credibility of placebo NMES and divergent opinions regarding the telephone support and diary. The quantitative data demonstrate that a definitive trial using this protocol should not be undertaken because of challenges in participant recruitment as well as between-group differences in retention, treatment adherence and blinding of participants in the control compared with the intervention group. However, this feasibility study provided important additional information that could inform future rehabilitation-based interventions.

Primary feasibility outcomes

The principal reason this protocol in its current format should not be tested in a definitive trial is that an insufficient number of participants were recruited to satisfy the a priori sample size requirement. A total of 364 potential participants were screened with 211 excluded prior to the eligibility assessment. The main reason for exclusion was the distance between the person’s home and assessment centre, despite the provision of transport. The Interstitial Lung Disease Unit at our hospital provides specialist care to people who live in a large geographic area, which may explain the reluctance to participate in the study. Although we have not faced such recruitment issues in other studies, our experience with this protocol suggests future rehabilitation-based research should be multisite and conducted alongside clinical appointments and/or located in centres accessible to participants and/or in participants’ homes. Out of 153 participants who attended the eligibility assessment, 23 consented to participate in the study. The most common reason for failing this assessment was MRC<3 or PR completion within 6 months. These conditions formed part of the inclusion criteria to ensure that people with advanced disease and a sedentary lifestyle respectively were recruited to the study. Going forward, trial eligibility based on indication for NMES rather than PR completion status may be more appropriate.

There was a trend for a greater proportion of participants in the control group to withdraw from the study, discontinue and perform less of the intervention, and/or become unblinded to group allocation. These findings may be related to statistical chance because of the small sample size, differences in between-group baseline characteristics and/or poor placebo NMES device credibility. The between-group difference in baseline characteristics and concerns about placebo NMES credibility were unexpected findings because the minimisation criteria used in the randomisation process and the placebo device were informed by previous studies.16 Furthermore, although two different devices were used to deliver active and placebo NMES, the outward appearance of both was identical and as such should not have contributed to the differences in participant perception. However, qualitative findings demonstrated that a participant in the control group believed he used a placebo device as the sensation was insufficiently strong. However, as only one participant allocated to the control group agreed to participate in the qualitative interviews, it is unclear if this finding is generalisable. Future research should consider reviewing the intensity and/or individualise the intensity of the placebo device.

In contrast to the control group, qualitative findings demonstrated that active NMES was acceptable to participants in the intervention group. In addition, the home exercise programme was also acceptable to both groups. However, there was a difference of opinion regarding the frequency of the telephone support and utility of the NMES and exercise diary. Exploration of these aspects of the intervention is important for future home-based rehabilitation studies in IPF.

Although blinding of some participants was not maintained, assessor blinding was successful. This was achieved by provision of an office isolated from the research laboratory that allowed the unblinded researcher to inform participants of group allocation, deliver the training session and schedule telephone calls.

The majority of the outcome measures were acceptable to participants and feasible to perform. However, there were a significant volume of missing accelerometer data because participants declined to wear the device or there were insufficient data to analyse. Going forward, researchers may decide to make wearing the device a prerequisite to study entry, shorten the device-wearing time or consider an alternative device that is more acceptable to participants.

There was a difference in the amount of expected and related adverse events in the intervention compared with the control group. These events occurred during or following NMES use and did not result in discontinuation of the intervention. Although not categorised as serious, these findings reinforce the importance of explaining the risks associated with this type of intervention in the patient information sheet.

Secondary outcome measures

Although the intervention and control groups were balanced in terms of the minimisation variables, there was imbalance in important variables that might influence exercise and physical activity capacity as a greater proportion of the control group were diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension and had a supplementary oxygen prescription associated with worse absolute and relative DLCO values, exercise capacity, activities of daily life performance, walking speed and physical activity levels. This may have arisen because of statistical chance given the small participant numbers; however, the minimisation variables used for randomisation may also have contributed to the problem. The minimisation variables (age, gender and quadriceps strength) were chosen as they were relevant to the population of interest and intervention, and were also informed by previous studies.16 However, although there is a strong correlation between quadriceps strength and exercise capacity (r=0.56, p<0.001) in interstitial lung disease,27 accounting for exercise capacity itself, as well as comorbidities and physical activity levels may be important in ensuring balance between trial groups in future research.

Owing to the small sample size, imbalance in between-group baseline characteristics and smaller number of control versus intervention group participants, it is challenging to identify an outcome measure that has the potential to be a primary or secondary outcome measure in a definitive trial. However, as there was a trend for greater reduction in sedentary time between baseline and 6 weeks as well as a greater increase in self-care ability and light-intensity physical activity between baseline and 12 weeks that favoured the intervention group, these outcomes may be worth exploring. However, as previously discussed, there was a significant amount of missing accelerometer data.

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths to this research. It was performed in line with the CONSORT 2010 statement.13 One of the inclusion criteria was a measure of quadriceps strength, which ensured NMES was indicated in the trial population. The intervention was based on PPI feedback and informed by published trials.16 We used an accepted placebo intervention to maintain participant blinding with outcomes assessed by a blinded assessor. We tested numerous relevant outcome measures that could be used in a definitive trial and undertook qualitative interviews that complemented the quantitative findings. However, there were some limitations. The use of a single centre in this trial likely contributed to under-recruitment of participants and consequently, we conclude that the current protocol should not be used in a definitive trial. This in turn led to insufficient recruitment of participants to the qualitative aspect, specifically to the control group which is in part a limitation, but also provides initial data on feasibility. Consequently, data saturation of experiences and perceptions was not achieved. Accordingly, the transferability of the qualitative findings may be limited.

Conclusion

We conclude that a definitive clinical trial to investigate the efficacy of NMES of the quadriceps muscles in advanced IPF using this protocol is not feasible. However, novel findings such as the frequency of telephone support, exercise and NMES diary format and choice of support and monitoring platform, for example, online versus telephone, could inform trials of future home rehabilitation interventions in this population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @clairemnolan84

Contributors: Concept and design of study: CMN, MM, WDCM. Acquisition of data: CMN, OP, SP, REB, JAW. Analysis of data: CMN, REB, WDCM. Drafting of manuscript: CMN, REB, WDCM. Revision of manuscript critically for important intellectual content: CMN, MM, WDCM, OP, SP, REB, JAW, PMG, EAR, AUW, PLM, VK, FC, TMM. Approval of final manuscript: CMN, MM, WDCM, OP, SP, REB, JAW, PMG, EAR, AUW, PLM, VK, FC, TMM.

Funding: This work was supported by a British Lung Foundation IPF Project Grant (grant number IPF/PG/17-15).

Competing interests: CMN reports receiving fees from Novartis, outside of this work. PMG reports fees, honoraria and grants from Roche Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cippla and Brainomix. EAR reports lecture and/or advisory board fees and/or grants from Roche Pharmaceuticals and Boehringer Ingelheim. AUW reports speaking and consultancy fees from Roche and Boehringer Ingelheim. PLM reports receiving fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim and Hoffman-La Roche, outside the submitted work. VK reports fees from Roche, outside the submitted work. FC reports fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche, outside the submitted work. TMM has, via his institution, received industry-academic funding from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline R&D and has received consultancy or speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Blade Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Galapagos, Galecto, GlaxoSmithKline R&D, Indalo, IQVIA, Pliant, Respivant, Roche and Theravance. WDCM reports personal fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Mundipharma, personal fees from Novartis, grants from Pfizer, non-financial support from GSK, grants from National Institute for Health Research, grants from British Lung Foundation, outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by London-Harrow Research Ethics Committee and Health Research Authority (18/LO/0209).

References

- 1.Fell CD. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: phenotypes and comorbidities. Clin Chest Med 2012;33:51–7. 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland AE, Fiore JF, Bell EC, et al. Dyspnoea and comorbidity contribute to anxiety and depression in interstitial lung disease. Respirology 2014;19:1215–21. 10.1111/resp.12360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishiyama O, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, et al. Quadriceps weakness is related to exercise capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2005;127:2028–33. 10.1378/chest.127.6.2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendes P, Wickerson L, Helm D, et al. Skeletal muscle atrophy in advanced interstitial lung disease. Respirology 2015;20:953–9. 10.1111/resp.12571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendoza L, Gogali A, Shrikrishna D, et al. Quadriceps strength and endurance in fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Respirology 2014;19:138–43. 10.1111/resp.12181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NICE . Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the diagnosis and management of suspected idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, 2013. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg163/chapter/introduction [Accessed 10th Jan 2019].

- 7.Dowman L, Hill CJ, Holland AE, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for interstitial lung disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;42:CD006322. 10.1002/14651858.CD006322.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishiyama O, Kondoh Y, Kimura T, et al. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2008;13:394–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vainshelboim B, Oliveira J, Yehoshua L, et al. Exercise training-based pulmonary rehabilitation program is clinically beneficial for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration 2014;88:378–88. 10.1159/000367899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holland AE, Hill CJ, Conron M, et al. Short term improvement in exercise capacity and symptoms following exercise training in interstitial lung disease. Thorax 2008;63:549–54. 10.1136/thx.2007.088070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NICE . Electrical stimulation to improve muscle strength in chronic respiratory conditions, chronic heart failure and chronic kidney disease, 2020. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg677 [Accessed 16th Dec 2020].

- 12.Jones S, Man WD-C, Gao W, et al. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for muscle weakness in adults with advanced disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;10:CD009419. 10.1002/14651858.CD009419.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016;355:i5239. 10.1136/bmj.i5239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:788–824. 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seymour JM, Spruit MA, Hopkinson NS, et al. The prevalence of quadriceps weakness in COPD and the relationship with disease severity. Eur Respir J 2010;36:81–8. 10.1183/09031936.00104909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maddocks M, Nolan CM, Man WD-C, et al. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation to improve exercise capacity in patients with severe COPD: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:27–36. 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00503-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European respiratory Society/American thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1428–46. 10.1183/09031936.00150314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MS, Mohan D, Andersson YM, et al. Phenotypic characteristics associated with reduced short physical performance battery score in COPD. Chest 2014;145:1016–24. 10.1378/chest.13-1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolan CM, Maddocks M, Maher TM, et al. Phenotypic characteristics associated with slow gait speed in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2018;23:498–506. 10.1111/resp.13213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canavan JL, Maddocks M, Nolan CM, et al. Functionally relevant cut point for isometric quadriceps muscle strength in chronic respiratory disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:395–7. 10.1164/rccm.201501-0082LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nolan CM, Birring SS, Maddocks M, et al. King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease questionnaire: responsiveness and minimum clinically important difference. Eur Respir J 2019;54:1900281. 10.1183/13993003.00281-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrod R, Bestall JC, Paul EA, et al. Development and validation of a standardized measure of activity of daily living in patients with severe COPD: the London chest activity of daily living scale (LCADL). Respir Med 2000;94:589–96. 10.1053/rmed.2000.0786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nolan CM, Maddocks M, Canavan JL, et al. Pedometer step count targets during pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:1344–52. 10.1164/rccm.201607-1372OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res 2016;26:1753–60. 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:1–8. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ 2010;341:c4587. 10.1136/bmj.c4587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe F, Taniguchi H, Sakamoto K, et al. Quadriceps weakness contributes to exercise capacity in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Respir Med 2013;107:622–8. 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-048808supp001.pdf (167.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.