Abstract

A 7-year-old boy with Marfanoid habitus presented with sudden and painless decrease in the vision of the right eye. Ocular examination revealed rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with 360° giant retinal tear in the right eye and small peripheral retinal breaks with lattice degeneration in the left eye. The patient underwent a 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy with scleral buckling in the right eye and laser around the breaks in the left eye. At 1-week follow-up visit, the child presented with similar complaints in the left eye as were seen in the right eye. This was later managed effectively with 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy only. So, with our case report, we would like to highlight the need for aggressive screening in children who are diagnosed with Marfan’s syndrome and the need for prophylactic treatment in the unaffected eye.

Keywords: retina, congenital disorders, ophthalmology

Background

Giant retinal tears (GRTs) are reported in 16%–18% of paediatric retinal detachments.1 The risk factors for GRTs include trauma, high myopia, and systemic diseases like Marfan’s syndrome, sticklers syndrome, atopic dermatitis and other disorders.2 Involvement of eyes is commonly seen in patients suffering from Marfan’s syndrome with a vast spectrum of complications. GRTs can be rarely seen, which could be missed initially. Subsequently, these patients present with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) at later follow-ups. Here, we would like to discuss an interesting case of a male child with Marfan’s syndrome where the patient had total RRD with GRT in the right eye (OD), followed by similar presentation in the left eye (OS). So, any areas of lattice degeneration or white without pressure (WWP) present in the fellow eye should be subjected to aggressive 360° barrage laser treatment once the patient has suffered RRD in one eye.

Case presentation

A 7-year-old male child with Marfanoid habitus presented with sudden and painless decrease in the vision of theOD. On ocular examination, the child had best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of perception of light with accurate projection of rays in OD and 20/80 with −11.00 D spherical lens in OS. Ocular adnexa were normal in both the eyes. Intraocular pressure was 6 mm Hg OD and 14 mm Hg in OS. On slit-lamp biomicroscopy, anterior segment examination was unremarkable with no evidence of lens subluxation or dislocation except a poorly dilating pupil in both eyes. The fundoscopy in OD revealed, tobacco dusting in the anterior vitreous with crumpled retina obscuring the view of optic disc and leaving the large area of bare choroid (figure 1A, B). The funduscopy in OS showed an area of lattice degeneration from 10’o clock to 3’o clock hours with few small retinal breaks and areas of WWP. There was no evidence of retinal detachment in OS. On general physical examination, the patient was tall for his age. The extremities showed abnormalities like long, thin, slender digits and genu valgum suggesting Marfanoid habitus (figure 2A, B).3 Pectus deformities of chest and hyperflexibility of the joints in the extremities could also be demonstrated (figure 2C). So, the patient was provisionally diagnosed as a case of Marfan’s syndrome having 360° GRT with RRD in OD and lattice degeneration with retinal breaks in OS.

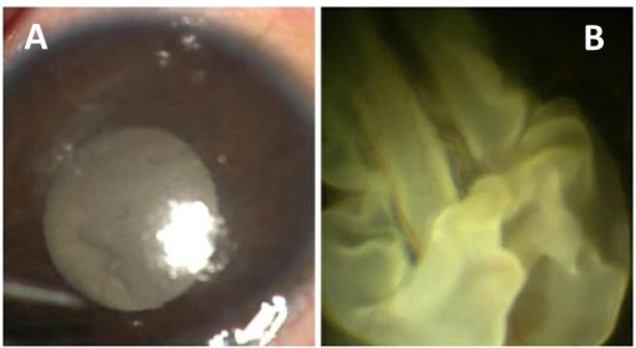

Figure 1.

(A) On diffuse light microscope examination white membrane like structure could be seen just behind the lens in OD. (B) Intraoperative image of OD showing crumpled retina with large area of bare choroid obscuring the view of optic disc. OD, right eye.

Figure 2.

(A) Both hands showing thin, long, slender digits. (B) Image showing genu valgum deformity. (C) Image showing pectus carinatum deformity.

Investigations

Paediatric consultation was taken which later confirmed our diagnosis of Marfan’s syndrome after going through complete systemic workup. Echocardiography was done which came out to be normal showing no evidence of cardiac and valvular abnormalities. Facilities for genetic workup were not available at our centre and parents also refused to get genetic testing done for the child from outside.

Treatment

The patient underwent a combined procedure comprising scleral bucking and 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with silicone oil tamponade with 360° endolaser in OD. During the surgery, after performing scleral buckle encirclage with 240 silicone band at equator PPV was done. So, after the removal of the anterior vitreous, perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL) was injected slowly over the disc to unfold the retina. The circumferential folds due to anterior circumferential proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) were noticed and cleared with the help of cutter and vertical endoscissors. The fixed retinal folds present superotemporal to the optic disc were also identified and cleared. After ensuring complete removal of vitreous tractions, the retina was settled with PFCL and 360° endolaser was done. Silicone oil—PFCL exchange was done (figure 3A, B). Focal laser treatment for the breaks within lattice degeneration was done in OS.

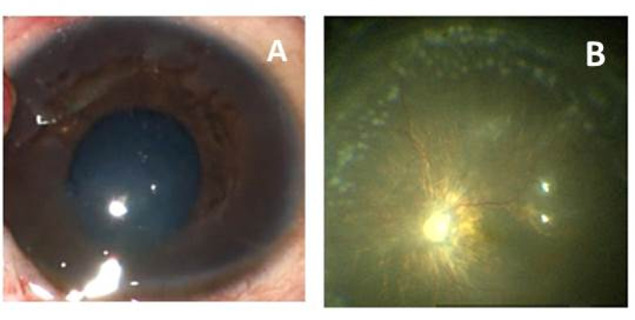

Figure 3.

(A, B) Postoperative image showing clear central visual axis and well attached retina with visible endolaser marks.

At 4 weeks follow-up visit, the patient came with decreased vision in OS after a trivial trauma sustained during the fight with a friend while playing. Anterior segment examination in OS showed the cellular reaction of 2+ according to Standardized uveitis nomenclature (SUN classification) and posterior segment examination in the same eye showed crumpled retina over the optic disc mimicking the presentation of the OD (figure 4). The patient was operated for 23-gauge PPV with silicone oil tamponade and 360° endolaser. The retina was attached postoperatively and patient achieved ambulatory vision in OS. At 6 months after parsplana vitrectomy of the OD, the patient developed cataract for which phacoaspiration with posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation was done.

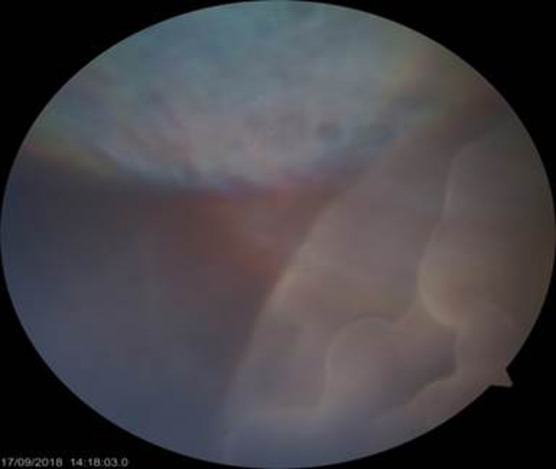

Figure 4.

Intraoperative image of OS showing crumpled retina with bare choroid similar to od presentation. OS, left eye.

Outcome and follow-up

On the last follow-up examination at 9 months, child had gained the BCVA of 20/200 OD and 20/80 OS with attached retina showing no signs of any recurrence of RRD or new breaks or silicone oil emulsification. As it was a high risk case, prolonged silicone oil tamponade was preferred.

Discussion

Marfan’s syndrome is one of the rare genetic disorders with an autosomal dominant inheritance which can result in various systemic abnormalities in major organs like the skeleton, heart, aorta, eyes and lungs. Ocular complications like ectopia lentis (50%–80%) are commonly seen as compared with retinal detachment (5%–11%) in this disease.4 GRTs which are defined as full-thickness tear in neurosensory retina involving circumferentially 90°/≥3 clock hours with posterior vitreous detachment at the posterior tear edge has an overall an incidence of 0.09–0.15/1,00,000 individuals/year but in patients with Marfan’s syndrome and the incidence rises to 11.3%.5 Most of the patients present at a very young age usually before 20 years of age. The incidence of retinal detachment in the fellow eye involved is as high as 70% forming the basis of prophylactic treatment in the normal eye if one eye has suffered the RRD or is having GRTs.6 7

The role of prophylactic laser treatment in the fellow eye is still controversial. In our present case, the retinal detachment occurred within 1 month despite laser treatment of retinal breaks in the lattice degeneration. In the index case, it appears that GRT developed in the areas of WWP and lattice degeneration. Thus, we recommend a prophylactic laser of the entire weak area and it should not be limited to breaks only.

In recent times, the prognosis of paediatric retinal detachments (RDs) with GRTs has improved with the advancements in vitreoretinal surgical techniques. In one large study, the primary success rate was reported to be around 84% after 20 years of follow-up.8 Similarly, another study of patients with Marfan’s syndrome has shown complete reattachment rates in 87.6% cases who underwent scleral buckle (including additional surgeries like vitrectomy) and in 86 %cases who underwent vitrectomy surgery only at a median follow-up of 11 months.6 British GRT Epidemiological Eye Study (BGEES) has reported the reattachment rates of 94.9% vs 94.4% in GRT without PVR and GRT with PVR, respectively, at last follow-up (11 months).9 Visual acuity showed final BCVA of ≥20/40 in 46% vs 33% in the above two mentioned groups. In the index case, both the eyes achieved anatomical success and the final BCVA was 20/200 in the eye with PVR and RD and 20/120 in the eye with fresh RD without any PVR. Keeping in mind the GRT with PVR, a belt buckle was applied and silicone oil tamponade was given. PPV with a high and a broader buckle is a recommended treatment for GRT with PVR in the presence of radial horns to prevent redetachment from anterior PVR.10 After PPV the risk of nuclear sclerosis varies from 33% to 100%. Notably, the development of cataract in not universal.

In the BGEES, British Giant Retinal Tear Epidemiology Eye Study, 70% of phakic patients had developed a cataract during the first year following GRT surgery.9 Preserving the lens in the primary sitting could minimise trauma of PPV in paediatric eyes where we expect intense inflammatory response after surgery. Moreover, intraocular lens (IOL) power calculation is often inaccurate in the eyes with macula off retinal detachments. To increase the success rates in GRT the encircling buckle and the type of tamponade could play a role. In a GRT with PVR of this gravity, the correct repositioning of the retina is difficult to be achieved with surgical procedures other than PPV with silicone oil temponade. The risk of slippage is minimised with silicone oil tamponade.11 Moreover in paediatric retinal detachments silicone oil is preferred over gases as patient fails to maintain prone position. The duration of silicone oil tamponade does not seem to correlate with visual outcome.12 As the index case was a high risk case, prolonged tamponade with silicone oil was preferred.

So, to summarise various reports have suggested that ocular complications associated with this syndrome are manageable with excellent visual outcomes if early diagnosis and timely referral is made. Anatomical success rates up to 70%–90% during long-term follow-ups can be achieved and results are now documented to be comparable to non-Marfan’s syndrome patients.6 7 With improved quality of care, the main aim is to salvage the vision in a visually impaired child and ultimately improve the quality of life for future years.

Patient’s perspective.

Early intervention and the utmost care has given my child the light for the future years. Wearing protective eye care should be emphasised.

Learning points.

Children suffering from Marfan’s syndrome should be thoroughly examined for the presence of any retinal degenerations or breaks on their first visit.

Child presenting with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in one eye should be given aggressive prophylactic 360° barrage laser treatment to all the areas of degeneration in the fellow eye at the earliest.

In cases of bilateral giant retinal tear with retinal detachment, doing early pars plana vitrectomy can greatly help in achieving good vision.

Acknowledgments

Navya Naveen Kalra MBBS student has helped in the language editing of the manuscript. Dr Siddarth Duggal MS for helping with the intraoperative images

Footnotes

Twitter: @Parrina Sehgal

Contributors: PS: writing and data acquisition. SN: concept, operating surgeon and editing. DC: editing, data acquisition.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mehdizadeh M, Afarid M, Haqiqi MS. Risk factors for giant retinal tears. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2010;5:246–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Kodolitsch Y, Robinson PN. Marfan syndrome: an update of genetics, medical and surgical management. Heart 2007;93:755–60. 10.1136/hrt.2006.098798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Kaissi A, Zwettler E, Ganger R, et al. Musculo-skeletal abnormalities in patients with Marfan syndrome. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 2013;6:CMAMD.S10279–9. 10.4137/CMAMD.S10279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nemet AY, Assia EI, Apple DJ, et al. Current concepts of ocular manifestations in Marfan syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol 2006;51:561–75. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberg DV, Lyon AT, Greenwald MJ, et al. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachments in children. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1708–13. 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00569-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma T, Gopal L, Shanmugam MP, et al. Retinal detachment in Marfan syndrome: clinical characteristics and surgical outcome. Retina 2002;22:423–8. 10.1097/00006982-200208000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abboud EB. Retinal detachment surgery in Marfan's syndrome. Retina 1998;18:405–9. 10.1097/00006982-199805000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minihan M, Tanner V, Williamson TH. Primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: 20 years of change. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:546–8. 10.1136/bjo.85.5.546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ang GS, Townend J, Lois N. Epidemiology of giant retinal tears in the United Kingdom: the British giant retinal tear epidemiology eye study (BGEES). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51:4781–7. 10.1167/iovs.09-5036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh YK, Banerjee S, Savant V, et al. Surgical treatment and outcome of patients with giant retinal tears. Eye 2004;18:996–1000. 10.1038/sj.eye.6701390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shunmugam M, Ang GS, Lois N. Giant retinal tears. Surv Ophthalmol 2014;59:192–216. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhatigan M, McElnea E, Murtagh P, et al. Final anatomic and visual outcomes appear independent of duration of silicone oil intraocular tamponade in complex retinal detachment surgery. Int J Ophthalmol 2018;11:83–8. 10.18240/ijo.2018.01.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]