Abstract

Organizational factors impacting burnout have been under-explored among providers in low income, minority-serving, safety net settings. Our team interviewed fourteen healthcare administrators, serving as key decision-makers in Federally Qualified Health Center primary care clinics. Using a semi-structured interview guide, we explored burnout mitigation strategies and elements of organizational culture and practice. Transcribed interviews were coded and analyzed using the Braun and Clark (2006) Thematic Analysis method. Mission-Driven Ethos to Mitigate Provider Burnout, emerged as the primary theme with two categories: 1) Promoting the Mission: ‘Bleeders’ and 2) Competing Priorities: ‘Billers’. These categories represent various properties and reflect administrators’ use of organizational mission statement as a driver of staff recruitment, training, retention and stratification. Data collection occurred before and during the COVID-19 global pandemic, as such, additional themes associated with administrative behaviors during a prolonged, clinical crisis provide insight into possible strategies that may mitigate burnout in this setting.

Keywords: Burnout, Wellbeing, Safety Net, Administrators, Primary Care

As many as fifty-four percent of physicians and 82% of nurses in the United States (US) experience burnout, which adversely affects their ability to provide quality care.1 The COVID-19 global pandemic has had an unprecedented, negative effect on providers, and organizations have struggled to support clinical staff that are often overburdened and under-resourced.2 Recent national studies have highlighted a growing distress among physicians and registered nurses (RNs), many of whom may leave their current position or the field all together when the pandemic resolves.3, 4 Among physicians, stories of moral injury and feelings of personal inadequacy to stem the tide of COVID-19-related deaths have led to at least one highly publicized suicide and a renewed call for solutions to the pervasive and persistent burnout we have seen over the past year. 5 Additional studies describing a “second pandemic,” a mental health crisis in health systems and communities, suggest that the worst is yet to come.6 While numerous data-driven position papers have emerged in recent months evaluating the effectiveness of wellbeing initiatives and suggesting practical methods for addressing employee anxiety and distress, few have examined this issue from the perspective of the individuals driving decision-making in their organizations.7 Even fewer have considered the long-term consequence of depersonalized care (an aspect of provider burnout) on health outcomes in historically marginalized racial/ethnic minority groups. that value empathy and an emotional connection with their providers.8, 9

Safety-net settings, including Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), address the care needs of the medically underserved who suffer from elevated poverty and health risk, as well as a shortage of primary care providers.10 As a barrier to the delivery (and acceptance) of culturally appropriate care in FQHCs, burnout is a threat not only to the provider, but to the patients. In a recent national survey of providers exploring physician burnout and suicide (n=~15,000 providers), approximately half reported that their feelings of depression have an impact on their delivery of patient care, including being more easily frustrated in front of patients (~17%), getting exasperated with patients (~38%), being less motivated to be careful with documenting in the medical record (~27%), or making errors they might not otherwise make (~16%).11

To date, the majority of previous burnout research among physicians has investigated high-stress/high-stakes, well-compensated12 clinical environments (emergency departments, intensive care, and surgical units) and during medical school training.13, 14 Among RNs and nurse practitioners (NPs), most have explored acute/intensive care, and inpatient areas.15, 16 While rarely representing a diverse community-based perspective, these studies have identified correlations between organizational processes (e.g., clinician training and use of multi-disciplinary teams) and rates of provider burnout suggesting a new, possibly fertile, direction for this research.

Finally, the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, which has demonstrated a consistent pattern of higher rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization, and death among underserved populations of color, highlights the need for immediate investigation of ways to support providers delivering necessary care among these vulnerable groups.17–22 Academic literature abounds with data on wellbeing programs and other provider burnout management strategies in academic and hospital settings, but there have been limited explorations among community-based providers working in shortage areas and a marked paucity of studies examining this phenomenon from the perspective of healthcare leaders/administrators. Our focus on FQHC administrators fills a large gap in the burnout literature and highlights the potential of systemic or organizational-level burnout interventions; therefore, our purpose was to describe current, systemic strategies employed by administrators in the safety net to prevent and alleviate provider burnout.

METHODS

Design

This qualitative, descriptive study was conducted between September 2019 and November 2020. The research used Grounded Theory techniques23 and the practical guidance of Duffy, Ferguson, and Watson (2004).24 (See Figure 1 in Data Analysis).

Figure 1.

6-Step Thematic Analysis of Administrator Data

Conceptual Model

We used two conceptual models to sensitize our research approach and interview guide. The first, The Action Model of Professional Fulfillment, acknowledges organizational and system-level culture as critical inputs for provider burnout.25 The second, The Burnout Dyad Model, brings patient experiences and social determinants of health impacting these experiences to the forefront of conceptualizing burnout.26 Additionally, this study explicitly rejected the traditional view of the patient as a minor character (or passive participant) in models of burnout.27 As we explored the experiences of administrators working in historically under-resourced, and/or marginalized communities, it was necessary to acknowledge the added complexity of serving this clinical population.

Data Collection

Setting.

The study focused on healthcare administrators, defined as individuals who hold a clinical license, hold a management/leadership position, and serve as key decision-makers for their clinical setting in FQHCs in Los Angeles County. Los Angeles County has over 10 million residents, and the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services is the second largest safety net health system in the US.28 Approximately 74% of county residents are non-White, compared to 40% of the overall US population. Los Angeles County also has an elevated poverty rate compared to the overall US population (13.4% vs. 10%).29

Sample.

We used convenience sampling and snowball sampling to recruit safety net administrators from Los Angeles County. These sampling approaches reflect the positioning of this exploration as Phase 1 of a larger qualitative study of burnout in FQHCs in Los Angeles County and leveraged preexisting relationships with participating sites for recruitment. Inclusion criteria were healthcare administrators, as described above, actively employed in a community-based FQHC or FQHC look-alike settings that meet the requirements of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Health Center Program. Exclusion criteria were clinicians not actively serving in a supervisory position in a FQHC or similar community-based, primary-care environment. A total of 20 administrators were contacted, 17 responded to recruitment materials, and all 17 were eligible for the study. In the end, a total of 14 administrators across 12 FQHCs participated in the interviews; all those who were qualified but declined to participate indicated that time constraints were the source of their decision.

Procedures.

Recruitment began by contacting organizations previously committed to participate in a cross-sectional, quantitative analysis of the impact of provider burnout on the quality of diabetes care delivery in the safety net. Facility contacts recommended individuals both inside and outside of their organization that met inclusion criteria; many of these individuals were members of a local Community Clinic Association. These contacts facilitated introductions with potential participants via email (including a flyer about the study). Interested parties contacted the PI directly for eligibility determination.

Participants were interviewed in person and by telephone (note: four in-person interviews were conducted in 2019 prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic; all subsequent interviews were conducted by phone). Interviews lasted 1–2 hours and were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide and recorded for later transcription. Some participants were interviewed more than once during theoretical sampling, for a total of 18 interviews.

Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using Grounded Theory methods in a process of continuous data collection and analyses. These analyses were organized using a Thematic Analysis approach.30 This study followed this six-step method that began with reviewing interview data and engaging in discussion and memoing with members of the study team; the data was then coded, themes were proposed, and theoretical sampling validated and clarified the thematic choices via the creation of robust definitions for each theme. These definitions were further refined and named through collaborative discussion and memoing. In this exploration, these steps resulted in the identification of a primary theme with two associated categories. Ultimately the process culminates in the dissemination of these findings (see Figure 1).

To protect participant confidentiality, original recordings were destroyed following transcription. De-identified transcriptions and other materials relevant to the study were maintained in a secured location under password protection. The University of California at Los Angeles Institutional Office of Research Protection Program determined that this study was exempt from full IRB review.

RESULTS

Fourteen administrators (N=14) in safety net settings were interviewed. Demographic data was collected for descriptive purposes only. The sample was 64% male (n=9) and 64% self-identified as physicians or Medical Doctors (MDs) (n=9); other professional licensure included RNs (n=2) and licensed social worker or licensed therapist (n=2). They were predominantly Hispanic/Latinx (57%, n=8); other races were white (n=2) and Asian (n=3).

An overarching theme, Mission-Driven Ethos to Mitigate Provider Burnout, emerged during analysis. This theme has two categories that reflect administrators’ efforts to use the organization’s mission statement as a driver of clinical culture and training. These categories are 1) Promoting the Mission: ‘Bleeders’ and 2) Competing Priorities: ‘Billers’. These categories represent various properties and are associated with specific administrative behaviors or activities designed to prevent or mitigate staff burnout (see Table 1). Across these interviews, the benefits and pitfalls of this approach were discussed, including the failure of mission-driven wellbeing approaches to resonate with individuals who had other reasons for choosing to work in an FQHC environment.

Table 1.

Categories and Properties of Mission-Driven Burnout Mitigation

| Categories of the Theme | Properties of the Categories |

|---|---|

| Promoting the Mission: ‘Bleeders’ | • Recruiting and Retaining ‘Bleeders’

• Making the Connection through Upstream Efforts |

| Competing Priorities: ‘Billers’ | • “We need to keep the lights on.”

• Making a Place for ‘Billers’ • Staff Shortages Help Bad Actors |

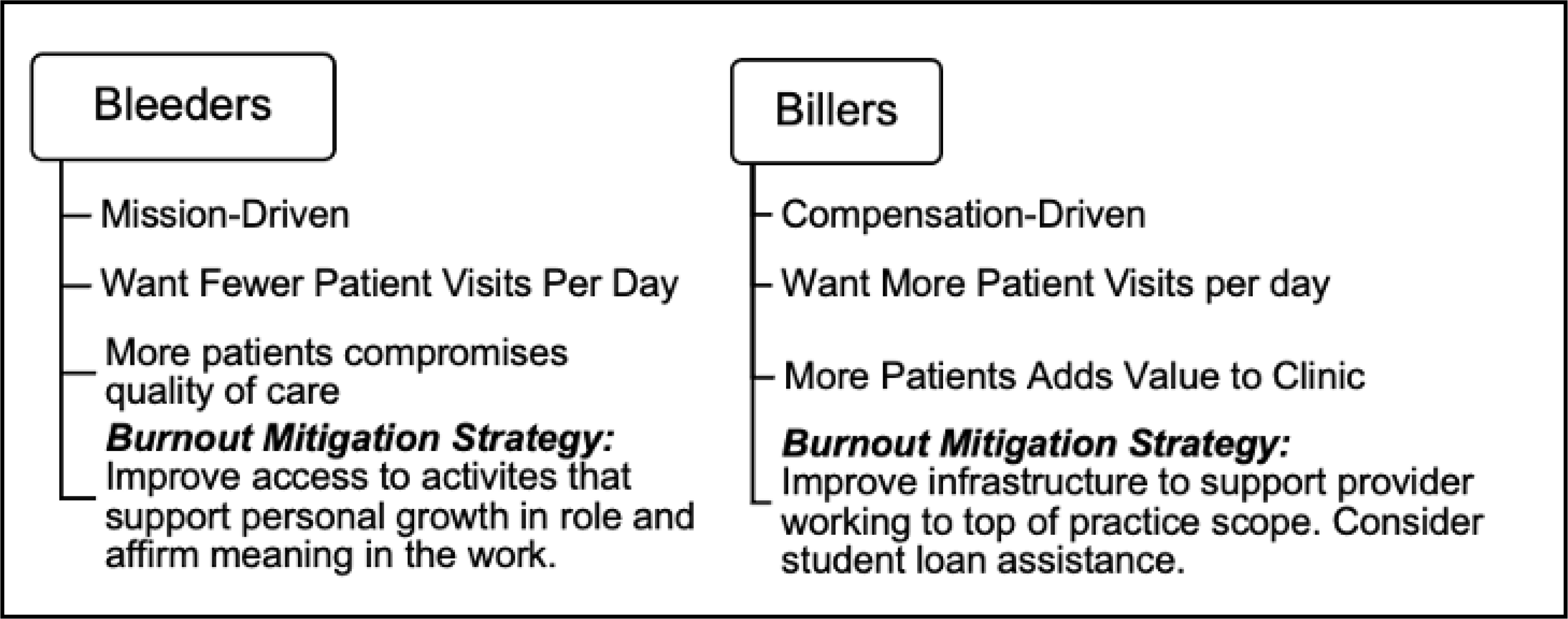

In addition to these categories, findings suggest an explanatory framework, the Bleeder-Biller Support Framework, which associates provider attributes/motivation with burnout mitigation strategies more likely to be effective for this group. This conceptual model describes two distinct provider types employed across FQHCs (‘Bleeders’ and ‘Billers’) and posits the need for burnout strategies according to provider type (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Bleeder-Biller Support Framework

Promoting the Mission: ‘Bleeders’

The category Promoting the Mission:

‘Bleeders’ describes how administrators convey and perpetuate an organizational mission. Properties of this category were: Recruiting and Retaining Bleeders and Making the Connection through Upstream Efforts.

Recruiting and Retaining Bleeders.

Administrators described working to fill and maintain their ranks with individuals committed to the organizations’ mission. Part of this effort is evaluating applicants for personal ethos during the hiring process. Across the interviews, many administrators lamented over their chronic understaffing and difficulty recruiting into a safety net environment yet expressed deep commitment to unspoken (sometimes difficult to attain) heuristics driving their hiring decisions. One administrator described this group as “well-meaning, do-gooders.” Another said: “We look for bleeders,” which was how they described deeply committed individuals. This same individual described how they would prefer a person who is “mission-fit” to a clinician who had received training from an elite medical school but was not committed to health equity work.

Administrators identify the search for deeply committed individuals as the beginning of an employment timeline that continues with ongoing efforts to mitigate burnout through reinforcing the mission. One administrator described this philosophy on staff retention as “not a sprint, but a marathon” and saw a primary component of their role as supporting providers in their purpose of “want(ing) to help people…the thing that drove (them) to be a physician.”

In addition to recruiting “bleeders,” administrators also described the need to frame challenges inherent to the safety net setting as part of a larger mission. They promoted a mission-driven identity that superseded the daily stress and challenges inherent to the work, one even stating that “It’s a calling … a fight against injustice.” Another administrator spoke of telling recruits that “You’re not only doing your job; you’re an ambassador for your patients. You’re becoming an ambassador for different types of thinking to other systems.” The same administrator pointed out that the capacious role of “bleeders” puts stress on a provider’s support system: “they can’t (or) don’t have the same type of relationships/ with boyfriends, girlfriends, (and) significant others.”

The proposed solution to this was early training to acquaint staff with this process of personal transformation and the need to bond with peers. In fact, the encouragement of supportive peer-mentorship networks was mentioned across several interviews.

Making the Connection through Upstream Efforts.

Several administrators described supporting their providers’ identity-building through exposure to upstream health-equity work. This included volunteerism and the ability to engage in research activities that inform evidence-based practice or policy. Some organizations have formal programs that “buy-out” time from clinicians’ workload to engage with these activities, while others simply found a way to work them into their providers’ billable services.

The idea that activities that add to the workload counterintuitively result in burnout mitigation was addressed by one administrator:

They get to do things within their schedule that they’re passionate about…that gives them an opportunity not to be bored because they’re doing something that they like… It’s filling your glass. It’s like getting it back to why you chose to do this work.

Another administrator summed it up: “research is another potential outlet for people… [it] stops them from feeling like another cog (in the system).” Similarly, volunteerism supported peer-bonding, which alleviated feelings of burnout.

Administrators also reported positive staff retention when early training explicitly recognized the clinical barriers facing care delivery in the setting. One administrator described the environment of the FQHC as “unique” in that it reflects “resource scarcity in the community,” suggesting providers should be trained to expect diminished ability of their patients to comply with treatment. Another described staff training that reflects this reality: “The core philosophy is training; and to give (the staff) context. Because if I don’t give context (of social determinates) they’re gonna be more frustrated with the work.”

Competing Priorities: ‘Billers’

Administrators in this study continually returned to the financial limitations they face when trying to combat staff burnout. The category, Competing Priorities: ‘Billers’, describes these challenges, across three properties: “We need to keep the lights on”, Making a Place for ‘Billers’ and Staff Shortages Help Bad Actors. Each of these properties describe the personal and logistical issues faced by administrators trying to meet the needs of a safety net provider population.

“We need to keep the lights on”.

Across these interviews, administrators described their distress from balancing the financial needs of the organization against their ethical duty to uphold the mission. Administrators explain the need to book (or over-book) clients in a payment model that often has to account for variability in patients’ adherence to scheduled appointments. Overbooking (as many as 60 patients per day) could allow for “no-shows” or patients who did not keep their appointment, but frequently led to providers having to sacrifice breaks during the day or stay late to accommodate the schedule when patients did arrive for their appointments.

Many administrators felt strongly that excessive patient load impacted the quality-of-care but felt bound by the financial needs of the organization. One noted that overworked providers might be comforted by the company ethos when asked to see an excessive number of patients: “because you’re working towards a bigger goal, I think that you adjust, and you just keep going.”

Making a Place for ‘Billers’.

Several administrators described how their overall costs could be offset by employing individuals who one participant described as ‘billers’. These clinical employees were prized for their ability to take on heavy caseloads, largely reflecting a philosophy rooted in maximizing billing at the expense of time spent or relationship-building with patients.

Similarly, across the interviews, administrators seemed to contrast those providers who were deeply mission-driven (‘bleeders’), and ‘billers’ who had chosen to work in the safety net for other reasons, such as student loan forgiveness. These ‘biller’ individuals were also described as “2-year commitments,” reflecting the two- to four-year contract usually required for student loan forgiveness through several government programs.31 One administrator who serves over a large, safety net health system described it as the “2-year/20-year problem,” “billers” staying for 2 years and “bleeders” for their careers.

The same individual who described the “2-year/20-year problem” said they had challenges with people who stayed long term (even if they believed in the mission of the organization) because this group tended to get detached from their peers and scientific progress in the field (such as using the latest in evidence-based practice). An administrator over a small FQHC added another angle on this concern; they said that individuals motivated by external validation from family and peers for their altruism could become quickly disillusioned by their more-committed peers.

Staff Shortages Help Bad Actors.

A compromised disciplinary process was another challenge mentioned by administrators in terms of burnout. One participant lamented: “a bad apple ruins the bunch” but also noted that terminating such employees would cause a huge deficit to the practice due to costly recruitment and on-boarding. “Bad apples,” therefore, were generally allowed to stay long after they might have been dismissed in other settings. Such inaction in turn has a deleterious effect on other staff members and can add to their burnout. The problem thus becomes how one can turn the bad apples into good ones. Remediation plans or leaves of absence are two possible strategies mentioned.32, 33

FQHC Provider Burnout during COVID-19

The semi-structured interview guide (SSIG) driving participant interviews was not adjusted to reflect emergent issues facing safety net settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, participants were not explicitly asked about the impact of COVID-19 on their experiences supervising clinical staff during this period; however, many organically shifted their responses to address this emergent public health crisis.

Administrators described covering for their clinical staff, and clinical staff covering for each other during the pandemic. This increased expectation of flexibility and reciprocity seemed to bolster a sense of teamwork. Other administrators described their clinical teams being galvanized by the conditions of the pandemic: “This is what we trained for”, said one. Another (interviewed in Spring of 2020) remarked several times on their concerns about insufficient availability of personal protective equipment, especially among those who came to work despite minor flu symptoms.

The decreased use of preventive and primary care services by hesitant patients in these clinics seemed to reduce pressure on some providers to perform despite short staffing. Others noted they had been asked to quickly pivot to online or telehealth platforms which could give their patients “24-hour access” to them. This opened the door to more uncompensated time providing patient care.

DISCUSSION

Administrators in our sample detailed the persistent challenges they face managing burnout among their safety net providers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The recognition of an overarching theme, Mission-Driven Ethos to Mitigate Provider Burnout, allowed our study team to frame these perspectives and explore how providers both promoted this mission through identity building and managed their own conflicting priorities as supervisors dedicated to the financial stability and success of the organization. Additionally, the recognition of (at least) two different and distinct types of employees, Bleeders vs. Billers, is a previously undescribed stratification method suggesting a better path towards targeted, efficient strategies to mitigate burnout.

Despite the tenuous financial nature of providing care in the safety net, which prompted administrators to continually balance mission with profit, our participants did not describe provider dissatisfaction with compensation as a driver of burnout. This is notable, as a recent Medscape 2020 Physician Compensation Report, representing 30 specialties, found that physicians who generally practice in community-based settings (pediatrics, family and preventive medicine) were among the lowest-compensated physician groups.12 They were also the least likely to receive incentive bonuses, which indicates this group is unlikely to connect increased caseload with financial benefit. However, of the providers polled in this national survey, 49% reported they would accept a salary reduction to have better work-life balance.12 These data indicate that systemic changes designed to improve provider compensation may be less valued than assistance with daily caseload or other structural issues impacting FQHC provider wellbeing. Given our stratification of providers based on motivation, however, this may be truer of ‘bleeders,’ who are generally less financially motivated than their ‘biller’ counterparts who value incentive-based bonuses. It is possible that provider compensation strategies that offer the option of either financial incentives, or time reserved for personal development (including participation in training, research or social activities) would be more broadly acceptable to both provider groups.

A challenge to such compensation strategies is reserving provider time in a historically overburdened and under-resourced setting. Several solutions to workload burden have been proposed in the literature, such as the use of “physician extenders” or other clinical professionals who can share the caseload in busy practices or assist with activities that do not require a medical license (such as patient education).12 However, in one VA study, authors found that spending time working with someone who has less training (OR 1.29, 95 % CI 1.07, 1.57) and in a stressful, fast-paced work environment (OR 4.33, 95 % CI 3.78, 4.96) was associated with higher burnout.34 Similarly, a recent national survey of 17k (17,461) MDs representing 30 specialties, found that half (49%) of physicians said hiring practitioners to “share the workload” had “no effect” on the profitability of their practice and the same group associated the tasks generally off-loaded to these individuals as one of the top three reasons they found their job to be rewarding (“building relationships with and feeling gratitude from patients”).12 This data, combined with our findings, suggest that augmenting providers’ opportunities to meaningfully engage with patients during visits may best support the feeling that their contributions are valued.

Participants in our study also said the underlying ethos/mission of the organization was a primary motivating factor and focus of their staff training model. Yet only one-third of physicians in the Medscape study reported the most rewarding part of the job was feeling like they were contributing to a larger mission (27%), while almost as many identified using their ability to exercise problem-solving skills (“being good at what I do,” “finding answers,” and “being good at diagnosing” [23%]) as valued aspects of their work.12 These data are consistent with our findings suggesting variability in provider motivation and the potential for use of a provider stratification system to build interventions that are most likely to engage providers where their interests lie.

Our findings also suggest organizational wellbeing initiatives promoting peer engagement may support commitment to the mission, while providing an additional benefit beyond burnout mitigation. While peer-based activities reinforce altruistic identity among Bleeders and may provide their Biller counterparts the opportunity to engage their analytic capabilities (in group case reviews, etc.) they also create a space for human connection and spontaneous discussions about mental/physical wellbeing. Self-isolating was the most commonly reported coping strategy to manage burnout in a 2020 national poll of providers (~45%).11 Of the ~15,000 physicians surveyed, 15–20% reported they were experiencing clinical depression, yet a large percent had not spoken to anyone about their thoughts of suicide (~40%), and the majority (~63%) had not sought professional care for burnout or depression in the past, with only a small number (~4%) reporting they intended to in the future.11 Wellbeing and burnout mitigation initiatives are intended to capture this at-risk population, yet almost half (42%) of the national sample said they would not participate in an employer-sponsored wellness program but were more willing to talk to a friend, colleague, or family member.11 Given these findings, opportunities for peer-peer mentorship or teams-focused interventions may bridge the gap between at-risk providers and critical, mental health services by creating a safe space to discuss pervasive, shared challenges.

Finally, concerns around lowered standards or slowed disciplinary processes in FQHCs highlight an important antecedent to burnout: the lack of enforcement of professional standards in chronically short-staffed environments. The consistent application of disciplinary standards regardless of staffing has been advocated across multiple industries.35, 36 However, the unique (and often competing) priorities challenging the provision of care in this setting call for tailored approaches to staff discipline that demonstrate consistency to the larger group, while reinforcing the seriousness of the infraction to the individual.

Most of our participants described heightened challenges to provider wellbeing across their clinical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. One emergent challenge was the need for rapid uptake/adoption of telehealth or other virtual platforms.37 These findings are consistent with a recent national survey that found telehealth visits/remote engagement increased 225% since the beginning of the pandemic.12 While most providers saw this new approach to patient visits as innovative and potentially beneficial in terms of access for the historically under-resourced patient population, some found the added pressure of 24-hour access to patient feedback/requests to be burdensome. Strategies that support work-sharing, previously described as an answer to burnout, have organically emerged during the pandemic (such as the spontaneous, flexible coverage described by our participants) and should be considered for continuation following the resolution of the pandemic.38

CONCLUSION

The FQHC setting is host to a variety of internal and external challenges facing provider wellbeing and remains a stand-out as a clinical setting and provider specialty in terms of burnout. Identity building using a mission-driven approach emerged as the primary method of burnout mitigation employed by our administrator participants. While this strategy is in alignment with findings from national polls of primary care providers, it may fail to support valuable segments of the workforce that choose to practice in the FQHC environment for reasons other than organizational mission. By diversifying burnout prevention/mitigation strategies, FQHCs and other safety net primary care environments might better support providers who aren’t “mission fit” but still fill a needed and important role in these provider shortage areas.

Limitations of this study included the lack of representative participation across ethnic/racial minority administrators in the safety net. Notably, the lack of African American participants (who comprise ~8% of the safety net patient population nationally, but 10.5% in the geographic area of the study) may have limited our view and compromised our access to critical insight on the phenomenon.39 Authors also acknowledge that binary views of complex phenomena are rarely able to capture nuance and variability in a population (or an individual) and may be impacted by secular events, such as the global pandemic during the period of data collection. Future explorations should consider examining these provider categories along a continuum, or to determine if additional provider types can be identified/described for the benefit of incentive alignment. Also, expanding across service provider areas (SPAs) in the geographic area of the study (a large, urban center), including rural areas of the county, may support a fully representative view. Additionally, due to the nature of data gathering during a global pandemic, the study team/PI was unable to perform site visits for most of the interviews, which may have prevented them from obtaining non-verbal cues reflecting participants’ responses.

Interventions piloting findings from this study represent a fruitful direction for burnout mitigation research. The core of this research, however, must remain the impact of improved provider wellbeing on the health outcomes of patients. Luckily, to borrow an aphorism from Former President John F. Kennedy, “a rising tide raises all boats”, and efforts to address FQHC provider burnout has the added benefit of potentially improving care delivery among vulnerable populations equally deserving of quality care, but historically denied it.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Our study team would like to thank our participants who shared their stories and experiences.

Contributor Information

Adrienne Martinez-Hollingsworth, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), 1100 Glendon Ave. Suite 900, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Linda Kim, Cedars Sinai, 8700 Beverly Blvd., Los Angeles, CA

Tabia Graham Richardson, Pepperdine University, Howard Hughes Center, 6100 Center Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90045.

Marco Angulo, AltaMed, 2040 Camfield Avenue, Los Angeles, CA.

Roger Liu, AltaMed, 2040 Camfield Avenue, Los Angeles, CA

Theodore Friedman, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science (CDU), 1731 E 120th St, Los Angeles, CA.

Kristen Choi, UCLA, School of Nursing, 700 Tiverton Dr. Rm 3-238, Los Angeles CA 90095.

References

- 1.Albott CS, Wozniak JR, McGlinch BP, Wall MH, Gold BS, Vinogradov S. Battle Buddies: Rapid Deployment of a Psychological Resilience Intervention for Health Care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anesth Analg July 2020;131(1):43–54. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blake N. Caring for the Caregivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. AACN Adv Crit Care. August 2020:e1–e3. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2020612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LitCovid. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/

- 4.Survey: Physician Practice Patterns Changing as a Result of COVID-19 | Merritt Hawkins. https://www.merritthawkins.com/news-and-insights/media-room/press/-physician-practice-patterns-changing-as-a-result-of-covid-19/

- 5.NBCNews. E.R. doctor on ‘front lines’ of coronavirus fight in N.Y. died by suicide. 2021; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi KR, Heilemann MV, Fauer A, Mead M. A Second Pandemic: Mental Health Spillover From the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2020. Jul/Aug 2020;26(4):340–343. doi: 10.1177/1078390320919803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohll A. How To Bring Mindfulness Into Your Employee Wellness Program. 2021; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Hollingsworth A, Hamilton N, Choi K, & Heilemann M (2021). The Secret-Self Management Loop: A grounded theory of provider mistrust among older Latinas with type 2 diabetes and mental health symptoms. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 175, 108787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Hollingsworth AS (2019). Simultaneous Experiences of Type 2 Diabetes and Symptoms of Depression and/or Anxiety Among Latina Women 60 and Older (Doctoral dissertation, UCLA). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aging NCo. Why Partner with FQHCs? https://www.ncoa.org/uncategorized/why-partner-with-fqhcs/#:~:text=They can be particularly useful in helping FQHCs,of patient involvement, patient education, and self-management support.

- 11.Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020: The Generational Divide. 2021;

- 12.Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020. 2021;

- 13.Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of Clinical Specialty With Symptoms of Burnout and Career Choice Regret Among US Resident Physicians. JAMA. September 2018;320(11):1114–1130. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huschka MM, et al. A multicenter study of burnout, depression, and quality of life in minority and nonminority US medical students. Mayo Clin Proc November 2006;81(11):1435–42. doi: 10.4065/81.11.1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purvis TE, Saylor D, Group NCaCS. Burnout and Resilience Among Neurosciences Critical Care Unit Staff. Neurocrit Care. August 2019;doi: 10.1007/s12028-019-00822-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blake N, Leach LS, Robbins W, Pike N, Needleman J. Healthy work environments and staff nurse retention: the relationship between communication, collaboration, and leadership in the pediatric intensive care unit. Nurs Adm Q 2013 Oct-Dec 2013;37(4):356–70. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3182a2fa47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Guilamo-Ramos V, Mena L, et al. Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Annals of epidemiology. 2020;52:46–53. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooper MW, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. Jama. 2020; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center KE, Da Silva J, Hernandez AL, et al. Multidisciplinary Community-Based Investigation of a COVID-19 Outbreak Among Marshallese and Hispanic/Latino Communities—Benton and Washington Counties, Arkansas, March–June 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(48):1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podewils LJ, Burket TL, Mettenbrink C, et al. Disproportionate Incidence of COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalizations, and Deaths Among Persons Identifying as Hispanic or Latino—Denver, Colorado March–October 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(48):1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riley AR, Chen Y-H, Matthay EC, et al. Excess deaths among Latino people in California during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sáenz R, Garcia MA. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on older Latino mortality: The rapidly diminishing Latino paradox. 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss C. Grounded theory methodology: An overview. - PsycNET. 2021;doi:TBD

- 24.Duffy FW. Data collecting in grounded theory - some practical issues. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Removed for blinding.

- 26. Removed for blinding.

- 27.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine, Medicine NAo, Well-Being CoSAtIPCbSC. A Framework for a Systems Approach to Clinician Burnout and Professional Well-Being. Text. 2019/October/23 2019;doi:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552621/ [PubMed]

- 28.Home - Health Services Los Angeles County. http://dhs.lacounty.gov/

- 29.Bureau USC. Quick Facts. Accessed January 19, 2021, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2014;9:26152. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v9.26152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Student Loan Forgiveness (and Other Ways the Government Can Help You Repay Your Loans). 2021.

- 32.Harding AD, Sipe M, Whalen KC, Almeida N. Applying the American Nurses Association Credentialing Center Accreditation Program in the Setting of Registered Nurse Remediation. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2018 Nov/Dec 2018;34(6):E1–E7. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Family and Medical Leave (FMLA) | U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/benefits-leave/fmla

- 34.Helfrich CD, Dolan ED, Fihn SD, et al. Association of medical home team-based care functions and perceived improvements in patient-centered care at VHA primary care clinics. Healthc (Amst). December 2014;2(4):238–44. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(PDF) The Effectiveness and Consistency of Disciplinary Actions and Procedures within a South African Organisation. 2021;doi: 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n4p589 [DOI]

- 36.Does Inconsistency Always Kill the Cat? 2021;

- 37.@CDCgov. Using Telehealth to Expand Access to Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic | CDC. 2020–09-10T04:34:03Z 2020; [Google Scholar]

- 38.@nypost. Job sharing might be the answer to avoiding burnout. 2017–04-07 2017;

- 39.#RACECOUNTS - Health Care Access Report. 2021;