Abstract

A lack of effective therapist training is a major barrier to evidence-based intervention (EBI) delivery in the community. Systematic reviews published nearly a decade ago suggested that traditional EBI training leads to higher knowledge but not more EBI use, indicating that more work is needed to optimize EBI training and implementation. This systematic review synthesizes the training literature published since 2010 to evaluate how different training models (workshop, workshop with consultation, online training, train-the-trainer, and intensive training) affect therapists’ knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors. Results and limitations for each approach are discussed. Findings show that training has advanced beyond provision of manuals and brief workshops; more intensive training models show promise for changing therapist behavior. However, methodological issues persist, limiting conclusions and pointing to important areas for future research.

Keywords: dissemination, evidence-based practice, implementation, mental health, training

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Psychological treatments have been developed and found to be efficacious for a range of mental health disorders (e.g., substance abuse, anxiety, depression), yet most therapists do not receive training in or use evidence-based interventions (EBIs; treatment techniques that have empirical support for improving mental health outcomes1) in routine practice (Garland, Bickman, & Chorpita, 2010; Gyani, Shafran, Myles, & Rose, 2014; Shiner et al., 2013). The field of implementation science (Eccles & Mittman, 2006) has identified strategies to facilitate the transfer of knowledge into settings where mental health services are most often delivered (e.g., community mental health; Ringel & Sturm, 2001). However, lack of EBI training remains a primary driver of poor access to effective mental health services, particularly for vulnerable populations (Kilbourne et al., 2018; Weissman et al., 2006). Conceptual models of implementation highlight that therapist use of EBIs is influenced by a complicated web of intersecting variables (e.g., organizational, fiscal, policy factors; Damschroder et al., 2009). Nonetheless, improving training remains a necessary step for successful EBI implementation and sustainment.

Many studies have examined the role of training to facilitate EBI implementation into practice. In 2010, three reviews of the effectiveness of training were published (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010; Rakovshik & McManus, 2010). Each took a slightly different approach to evaluating the literature; however, all three highlighted the potential for optimizing training procedures as a strategy for increasing therapist EBI use. Overall, findings suggested that therapist self-study of treatment manuals was generally ineffective at increasing EBI use (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005). In-person and online training courses demonstrated some effectiveness for increasing therapist knowledge and self-efficacy, but had limited effect on provider behavior and client outcomes (e.g., Dimeff et al., 2009; McHugh & Barlow, 2010). Prior reviews also indicated that using active training strategies, such as behavioral rehearsal (role play), led to higher adherence and skill on behavioral rehearsals after training, without consistently translating to greater use in practice (Beidas & Kendall, 2010). Given that increasing implementation of EBIs in clinical practice is the ultimate goal of therapist training, further examination of effective training strategies and their impact on practice is warranted.

The 2010 reviews also highlighted the importance of training that moves beyond the traditional workshop format (e.g., providing ongoing consultation or supervision2 following workshops) to increase therapist EBI use. In particular, consultation following workshops led to increased knowledge and skill and more use of the target EBI in practice (Beidas, Edmunds, Edmunds, Marcus, & Kendall, 2012; Schoenwald, Sheidow, & Letourneau, 2004). Multi-component trainings (i.e., using multiple of the following: in-person workshops, consultation, supervisor training, booster training) also demonstrated better outcomes than training approaches that relied on one or two components. These earlier reviews were consistent in calling for more research in areas related to therapist training strategies, including web-based training, consultation/supervision practices, and “train-the-trainer” (TT) methods, as well as the need for direct comparisons of different training methods. Such work has relevance in identifying specific implementation strategies to increase the uptake of EBIs in routine clinical care. All prior reviews also highlighted methodological issues that limited drawing firm conclusions, including limited use of theory to guide study design, lack of comprehensive measurement of target constructs (i.e., self-report only; no gold-standard outcome measures), and use of nonstandardized measures.

Despite these calls for more research and advances in implementation science (Williams & Beidas, 2019), EBI use in routine practice remains low (Becker, Smith, & Jensen-Doss, 2013; Beidas et al., 2019; Stirman et al., 2012). Active training strategies combined with post-training consultation are currently referred to as “gold-standard” packages, yet their dosage is not well defined, and they have yielded disappointing results (e.g., Beidas et al., 2019). Concerns about the feasibility and sustainability of strategies such as expert consultation and session feedback have been raised due to being resource-intensive and relatively short-term (McHugh & Barlow, 2010). Understanding how to optimize training strategies for EBI is key for improving access to EBIs for treatment-seeking individuals. A comprehensive review of the research conducted in this space since 2010 is needed to characterize the current state of the science for EBI training strategies to identify effective strategies and future directions for research on therapist training.

This review focused on five types of training: workshop only (an “in-person” time-limited training opportunity that focuses on a single intervention topic), workshop plus consultation (workshop plus additional expert consultation/supervision after conclusion of the initial training), online training (training conducted via an online platform with either asynchronous [self-paced] or synchronous learning, with or without consultation), TT (an expert trainer trains a set of local trainers who in turn will train local therapists, alternatively called a “cascade” model of training), and intensive training (defined as at least 20 hours of training plus two or more additional training components, such as consultation, direct observation of practice, or learning collaboratives). Outcomes of interest for this review represented a range of implementation and effectiveness constructs, including the following: (a) therapist attitudes, knowledge, self-efficacy, and training satisfaction; (b) EBI adherence, competence, and use; (c) implementation barriers; and (d) client outcomes. This review also examined the degree to which previously identified limitations (e.g., lack of theory, nonstandard measures) have been addressed. Finally, attention was paid to the extent to which therapist characteristics (e.g., age, experience) affected training outcomes, given work suggesting clinical outcomes may vary by therapist (Huppert et al., 2001). Although EBI training efforts might target therapists completing graduate education (i.e., “pre-service”), this review focused on strategies for training mental health therapists employed in community practice settings, including hospitals, private practice, and community mental health settings (i.e., “post-service” therapists).

2 |. METHOD

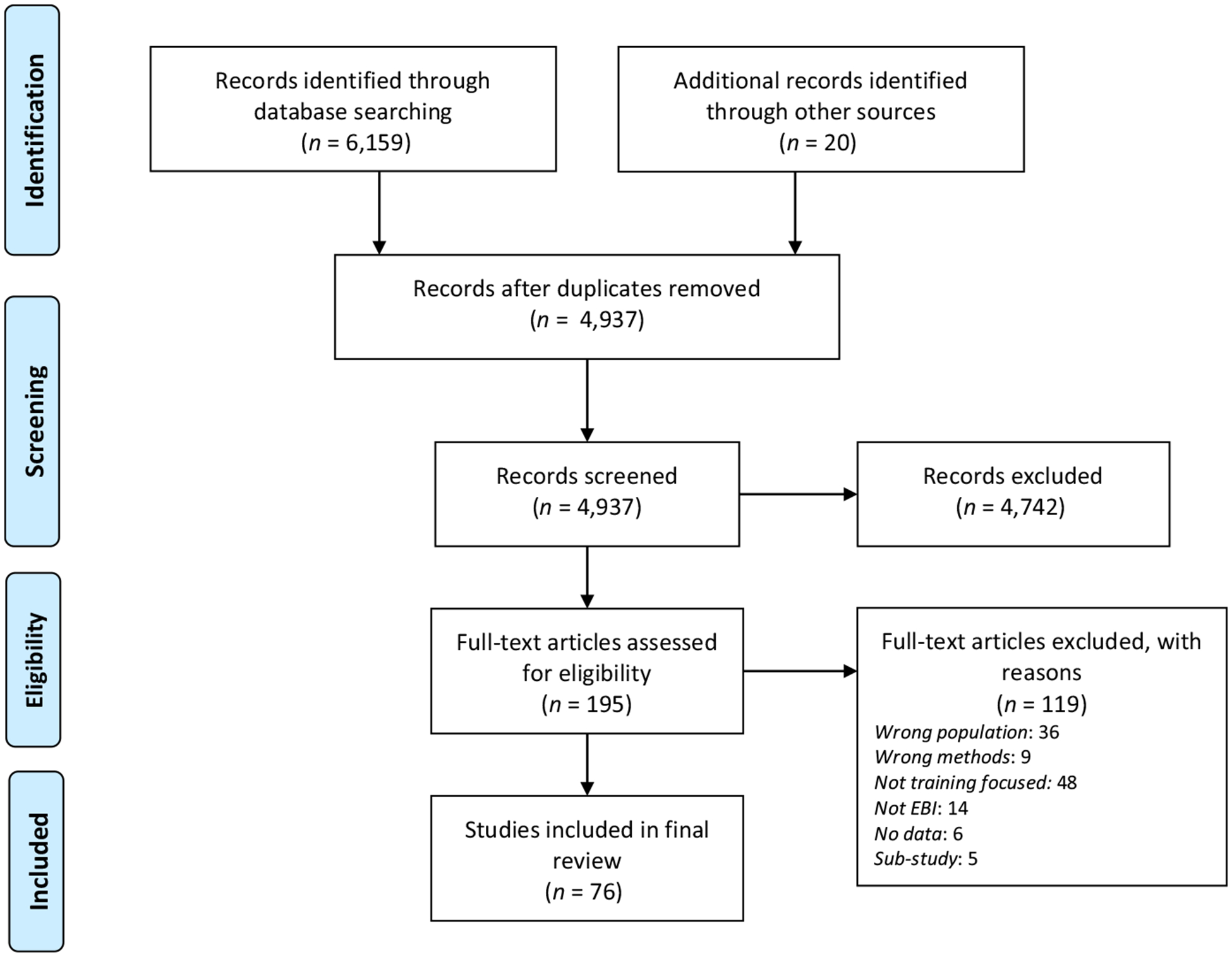

A systematic literature search identified all relevant articles published since the 2010 reviews (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell et al., 2010; Rakovshik & McManus, 2010) between March 2010 and May 2018. An initial search for articles published between 2010 and 2017 was conducted in PsycINFO and PubMed using the following key words: training, workshop, dissemination, implementation, TT, web-based training, online training, adoption, therapist, clinician, community, mental health, behavior health, evidence-based, empirically supported, intervention, evidence-based practice, empirically-supported treatment. Due to the length of the review process, Google alerts for the phrases “dissemination and implementation” and “clinician training evidence-based practice” identified articles from November 2017 to May 2018. Finally, consistent with Greenhalgh et al. (2004) and Herschell et al. (2010), a snowball method augmented the database search, whereby references of included articles were used to identify additional citations. Abstracts were screened by the first and second authors, supported by Rayyan software (Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, 2016). Regular meetings were used to discuss uncertainties about an abstract’s relevance with decisions made by consensus. Relevant articles were full-text reviewed to determine inclusion. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA study flow diagram.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram indicating study identification, screening, and selection

Studies were included if (a) the focus was on training mental health providers with an advanced degree (i.e., a medical degree, doctorate, or master’s degree) in a mental health field (e.g., social work, psychology, psychiatry, substance abuse counseling), and (b) the training focus was an evidence-based mental health or substance abuse intervention. Studies additionally had to report on at least one of the following training outcomes: post-training attitudes, knowledge, self-efficacy, satisfaction, adherence, competence, or EBI use, include at least some quantitative data, be a peer-reviewed study, and be in the English language. Inclusion criteria were intended to allow for the broadest possible sample of studies aimed at improving EBI use in mental health and thus allowed for inclusion of studies with different training foci, durations, and approaches. Exclusion criteria included the following: (a) more than half of participants were not mental health providers (e.g., teachers, occupational therapists, nurses) or were high-school or bachelor’s level therapists (e.g., peer specialists), (b) the target EBI was not a mental health intervention, (c) the study used an identical sample to a parent study included in the review, or (d) the training was geared toward graduate students (e.g., semester-long courses, graduate education initiatives) and not practicing therapists. This latter exclusion criterion was selected because implementation challenges are thought to differ for students relative to postgraduate, practicing therapists (Becker-Haimes et al., 2018). Included studies were classified as follows: workshop only, workshop with consultation, online training, TT, or intensive trainings. Studies that examined multiple training approaches were classified by the modality of the active comparison condition (e.g., if a study compared an online workshop to traditional in-person workshops, it was included in the online training section).

Consistent with Herschell et al. (2010), studies were classified according to Nathan and Gorman’s (2002, 2007) criteria for evaluating methodological rigor. All studies in this review were classified as Type 1, Type 2, or Type 3; as noted above, studies needed to include quantitative data analysis; as such, Type 4 (reviews with secondary data analysis), Type 5 (reviews without secondary data analysis), and Type 6 (case studies, essays, opinion papers) studies were excluded. Type 1 studies are randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with comparison conditions, random assignment, blind assessments, clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, state-of-the-art diagnostic methods, and sufficient statistical power and description of statistical methods. Type 2 studies are clinical trials missing one or more of the criteria for Type 1 studies (e.g., lack of random assignment, underpowered), but not fatally flawed. Finally, Type 3 studies have clear methodological limitations and are typically uncontrolled studies using pre-post design and retrospective design. The first author coded all studies for classification as Type 1, Type 2, or Type 3. The last author reviewed a random subset of studies (n = 16; 21.1%) and discussed classification with the first author, obtaining consensus of classification for 100% of studies reviewed. A minority (12%; n = 9) of studies were Type 1, 14% (n = 11) were Type 2, and 74% (n = 56) were Type 3. Most Type 2 studies lacked clear inclusion criteria or random assignment to condition. Most Type 3 studies had a lack of comparison conditions (i.e., within-subjects design) or lack of randomization.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Summary of the literature

A total of 76 reports met inclusion criteria. Identified studies examined in-person workshop only (n = 9), in-person workshop and consultation (n = 21), online workshop (n = 20), TT (n = 4), and intensive trainings (n = 22). No identified studies examined treatment manuals or written materials alone. The following sections detail and review the approach, findings, and limitations of studies using each training modality, consistent with Herschell et al. (2010). Additional details for each study are in Tables 1–5, and an overview of findings for all studies is shown in Table 6.

TABLE 1.

Workshop only

| Author | Nathan & Gorman classification | Sample size | Training topic | Amount of training | Comparison groups | Follow-up | Role of consultation | Outcome measure domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farrell et al. (2016) | 2 | N = 49 mental health clinicians | Exposure therapy for anxiety disorders | 8 hr | 2: Standard versus Enhanced training | None | None | A, K, S |

| Chin et al. (2018) | 3 | N = 53 community clinicians | Prolonged exposure for PTSD | 8 hr | None | None | None | A, Int |

| Crisanti et al. (2016) | 3 | n = 20 licensed behavioral health practitioners + n = 15 peer support workers | Seeking Safety for trauma | 6 hr | None | None | None | K, S, Sat |

| Deacon et al. (2013) | 3 | N = 162 community mental health professionals | Exposure therapy for anxiety disorders | 7 hr | None | None | None | A |

| Lim et al. (2012) | 3 | N = 268 public sector youth mental health providers | EBIs for internalizing and externalizing disorders | Not specified | None | None | None | A, K |

| Mirick et al. (2016) | 3 | N = 543 participants | Suicide assessment and intervention | 6 hr | None | None | None | C, K |

| Richards et al. (2011) | 3 | N = 73 mental health clinicians | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy | 1 day | None | 1 year | None | K, P, PF |

| Scott et al. (2016) | 3 | N = 30 therapists | CBT | 1 day | None | None | None | K |

| Waller et al. (2016) | 3 | N = 34 clinicians | Exposure therapy for eating disorders | 1.5 hr | None | None | None | A |

Abbreviations: A, attitudes; C, confidence (self-efficacy); CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; Cl, clinical outcome; F, treatment fidelity or adherence; I, implementation difficulty or barrier—anticipated or actual; Int, intentions; K, knowledge; P, practices or techniques used; PF, psychological flexibility; S, skills/competence; Sat, satisfaction/acceptability; T, therapeutic interaction/rapport/working alliance.

TABLE 5.

Intensive training

| Author | Nathan &Gorman classification | Sample size | Training topic | Amount of training | Comparison groups | Follow-up | Role of consultation | Outcome measure domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kolko et al. (2012) | 1 |

N= 128 practitioners; N = 34 supervisors |

Alternative for Families (AF-CBT) | 32 hr | 2; learning community; training as usual | 18 months | 10 90-min biweekly group consultation | A, O, P, K, Sat |

| German et al. (2017) | 2 | N = 214 clinicians | CBT | 22 hr | 2; In-person training, expert-led consultation; Web-based training; peer- led consultation | 6 months | Weekly 2-hr meetings for 6-months with experts; then with peers only | K, S |

| Stirman et al. (2017) | 2 | N = 85 clinicians | Cognitive Therapy | 22 hr | 2; individual consultation; group consultation | 2 years (from baseline) | Individual: 1-hr individual; 1-hr group; Group: 2 hr group | S |

| Webster- Stratton et al. (2014) | 2 | N = 56 community mental health therapists | Incredible Years for Conduct Problems | 3 days | 2; workshop only; workshop + consultation | None | Weekly consultation calls (duration not reported); Written feedback on video recordings | F |

| Beveridge et al. (2015) | 3 | N = 143 therapists | PCIT | 40 hr + two 1-day advanced trainings held 2 months after initial training | None | None | 1-hr biweekly phone consultation group until PCIT completed with 2 clients | Sat |

| Creed et al. (2013) | 3 | N = 25 school- based therapists | Cognitive Therapy | 22 hr | None | 6 months | Weekly 2-hr meetings for 6 months | K, S, Sat |

| Creed et al. (2016) | 3 | N = 321 community mental health therapists | CBT | 22 hr | None | 6 months | Weekly 2-hr meeting for 6 months | S |

| Herschell et al. (2014) | 3 | N = 64 mental health therapists | DBT | 2-day clinical + 1-day admin overview; two 5-day workshops (6-months apart); 2-day follow-up training | None | 6-, 14-, and 22-months post-training | Weekly phone consultation for 14 months | A, C, P |

| Jackson et al. (2017) | 3 | N = 32 clinicians | PCIT | 40 hr; advanced 16-hr training 6 months later | None | 2 years (from baseline) | Up to 24 1-hr consultation calls over 1 year | I, K, S |

| Karlin et al. (2012) | 3 |

N = 221 mental health therapists; N = 356 veteran patients |

CBT for depression | 3 days | None | 6-month postconsult.; 3–12 months post-training | 6 months of 90-min weekly group calls; submission of audio recordings | A, C, Cl, Int. P, S, Sat |

| Karlin et al. (2013) | 3 | N = 102 clinicians; N = 182 veteran patients | CBT for insomnia | 3 days | None | None | 4 mo. of weekly 90-min group calls; submission of audio recordings | Cl, S |

| Lopez and Basco, (2011) | 3 | N =7 therapists | CBT for major depressive disorder | 36 hr | None | None | 5 months of 1-hr group phone supervision 2x/week; submission of audiotaped sessions | A, Cl, S |

| Manber et al. (2013) | 3 | N = 207 therapists | CBT for insomnia | 3 days | None | 6 months post-consultation | 4 months of weekly 90-min group consultation calls; submission of audiotaped sessions | A, C |

| McManus et al. (2010) | 3 | N = 278 trainees | CBT | 36 days over 12-week term; 5 hr workshops each day | None | None | 90 min. supervision at each workshop; submission of audiotaped sessions | S |

| Navarro-Haro et al. (2019) | 3 | N = 412 participants | DBT for borderline personality disorder | 2 sets of 5-day workshops (6-months apart) | None | None | Contact with trainers, but no formal consultation | A, C, I, P |

| Ruzek et al. (2016) | 3 | N = 943 licensed mental health clinicians | Prolonged exposure for PTSD | 4 days | None | Post-consultation | 6–9 months of 60-min weekly individual and group consultation; audiotape review | A, C, Int |

| Ruzek et al. (2017) | 3 | N= 1,034 clinicians | Prolonged exposure for PTSD | 4 days | None | Post-consultation; 6 months post-consultation | Weekly individual (30- min) and group (60-min) consultation for at least two cases; audiotape review | A, C, Int, P |

| Shah, Scogin, Presnell, Morthland, and Kaufman (2013) | 3 |

N = 5 therapists; N =88 patients |

CBT for rural adults | 24 hr | None | Post-treatment | Weekly group supervision and feedback on mock sessions (duration not reported) | Cl, F, S |

| Smith et al. (2017) | 3 | Study 1:N= 234 regional learners; Study 2: N = 24 blended pilot learners; Study 3: N= 40 blended pilot learners | Study 1: Cognitive Processing Therapy; Study 2: CBT for depression; Study 3: Prolonged exposure for PTSD |

Study 1: 3 days Study 2: 7 hr online + 7 weekly 1–2hr. webinars Study 3: web-based course + 5 weekly 2-hr webinars |

Each study compared alternative training models to traditional VA training model | Study 1: none; Study 2:4 months postconsultation; Study 3:6 months postconsultation |

All studies: Weekly consultation with tape review (call duration not reported) Blended learning: 4 months Traditional learning: 6 months |

Study 1: Cl, Sat Study 2: S, Sat Study 3: Cl, K, S |

| Stephan, Connors, Arora, and Brey (2013) | 3 | Not reported | Core elements of EBIs for anxiety, depression, disruptive behavior disorders, substance abuse | 4 days over 13 months | None | Post-training (13 months) | Monthly technical assistance (duration not reported); Learning Collaborative | K, P |

| Walser et al. (2013) | 3 |

N = 391 therapists; N = 745 patients |

ACT for depression | 3 days | None | Post-consultation (3–12 months) | 6-months of 90 min weekly consultation; feedback on audiotaped sessions | A, C, Cl, Int, K, S, T |

| Williams, Martinez, Dafters, Ronald, and Garland (2011) | 3 | N = 267 therapists | CBT self-help workbook | 38.5 hr | None | Post-intervention, 3-month follow-up | Weekly supervision (5 hr total) | K, P, S, Sat |

Abbreviations: A, attitudes; ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; C, confidence (self-efficacy); CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; Cl, clinical outcome; DBT, dialectical behavior therapy; F, treatment fidelity or adherence; I, implementation difficulty or barrier—anticipated or actual; Int, intentions; K, knowledge; P, practices or techniques used; PCIT, parent–child interaction therapy; PF, psychological flexibility; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; S, skills/competence; Sat, satisfaction/acceptability; T, therapeutic interaction/rapport/working alliance, VA, Veterans Affairs.

T A B L E 6.

Summary of results

| Workshop type | Conclusions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Workshop only |

|

|

| Workshop and consultation |

|

|

| Online training |

|

|

| Train-the-trainer |

|

|

| Intensive training |

|

|

3.2 |. Workshop only

3.2.1 |. Description of studies

Of the workshop-only studies (n = 9; Table 1), one was Type 2 and eight were Type 3. Most studies used within-subject designs and only included pre- and post-training assessments without follow-up. Sample sizes varied widely, ranging from 30 to 268 participants working primarily in community mental health and public sector settings. Workshop length ranged from 90 minutes to 8 hours. Outcome measures were all self-report, and client outcomes were not examined. Knowledge was the most commonly assessed outcome (in six of nine studies). Two studies used psychometrically supported assessments of knowledge (Lim, Nakamura, Higa-McMillan, Shimabukuro, & Slavin, 2012; Scott, Klech, Lewis, & Simons, 2016); the remainder used knowledge measures developed for the study. Attitudes were the second most frequently examined outcome (five of nine studies); four studies used attitude measures with acceptable psychometric properties (i.e., the Evidence-Based Practice Attitudes Scale (EBPAS; Aarons, 2004) or the Therapist Beliefs about Exposure Scale (TBES; Deacon, Lickel, Farrell, Kemp, & Hipol, 2013).

3.2.2 |. Summary of findings

Consistent with prior reviews, studies of in-person workshops without additional consultation or follow-up indicated improvement in knowledge and attitudes about EBIs after training, although results were variable. Scott et al. (2016) demonstrated that even though training led to improvements in knowledge, overall post-training knowledge scores remained low. Lim et al. (2012) found that providers over-generalized the label for EBIs, applying it to non-EBI strategies. Farrell, Kemp, Blakey, Meyer, and Deacon (2016) conducted the only study comparing two training conditions and found that therapists who received an enhanced training focused on discussing therapist concerns about exposure therapy had significantly greater reductions in such concerns than those in standard training. Those in enhanced training also self-reported superior quality delivery of exposure therapy based on case vignettes.

Several studies examined pre-training therapist characteristics as predictors of training outcomes (Lim et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2016; Waller, Walsh, & Wright, 2016). Results were mixed regarding whether prior experience with the EBI or more favorable attitudes toward EBIs are associated with post-training changes in knowledge and attitudes (Deacon et al., 2013; Lim et al., 2012; Mirick, McCauley, Bridger, & Berkowitz, 2016; Scott et al., 2016; Waller et al., 2016). Richards et al. (2011) reported that participants with higher psychological flexibility had more knowledge post-training. Therapist skill was examined in two studies (Crisanti, Murray-Krezan, Karlin, Sutherland-Bruaw, & Najavits, 2016; Farrell et al., 2016) and EBI use was only examined in one study (Richards et al., 2011), all using self-report measures. Thus, these findings provide limited information about the extent to which workshops alone changed therapist behaviors.

3.2.3 |. Limitations of studies reviewed

Workshop-only studies were predominantly within-subject, nonrandomized, and did not include follow-ups. Most had a naturalistic design that allowed for examination of training efforts that were already underway but were not designed to examine empirical questions. Most of the measures were self-report and had not been psychometrically evaluated, limiting generalizability. In addition, comparison across studies was difficult given variability in the length of training and training approach. Most workshops were reported to include active learning components (e.g., role plays), citing previous research suggesting their importance, but most studies did not expand on the ways or frequency with which these strategies were implemented.

3.3 |. Workshop and consultation

3.3.1 |. Description of studies

Of the workshop and consultation studies (n = 21), only one was Type 1, an RCT comparing different training approaches (Beidas, Edmunds, et al., 2012). There were three Type 2 studies, none of which had explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria, and some of which were lacking in blind assessments or a sufficient sample size. Finally, there were 17 Type 3 studies with predominantly pre-post designs, though some included follow-ups, quasi-experimental designs, retrospective surveys, and qualitative interviews. Of note, several studies had sub-studies from the same datasets (Beidas, Mychailyszyn, et al., 2012; Leathers, Melka-Kaffer, Spielfogel, & Atkins, 2016; Lloyd et al., 2015), which are not included in this review.

Sample sizes ranged from 7 to 1,107 participants working in community, public sector, or Veterans Affairs (VA) settings. Workshop lengths varied from 4 hours to 4 days. The most frequently assessed outcomes included attitudes (10 studies), intervention use (10 studies), and competence (nine studies). A minority of studies used measures of attitudes with psychometric support (Hamblen, Norris, Gibson, & Lee, 2010; Pemberton et al., 2017); most used attitude measures developed for each study. Intervention use was assessed by therapist self-report in all studies, typically using measures designed for each study. Competence, assessed in nine studies, was the only outcome measure that consistently used observer ratings. Competence was assessed through role plays with standardized clients (Beidas, Edmunds, et al., 2012), observation of actual sessions (Brookman-Frazee, Drahota, & Stadnick, 2012; Henggeler, Chapman, Rowland, Sheidow, & Cunningham, 2013; Lu et al., 2012; Simons et al., 2010), or both (Petry, Alessi, & Ledgerwood, 2012). Studies that included client outcomes (n = 6) typically had limited or no exclusion criteria for clients and were said to be representative of clients in community settings.

Consultation was weekly or biweekly for most studies and typically occurred over the phone or via video chat for up to 1-year post-training. Most consultation was in a group format for 60–90 min. However, some studies offered individual consultation calls that lasted 30–60 min. One study provided on-site weekly group supervision (Lu et al., 2012), and others provided feedback on fidelity based on reviews of recorded sessions (e.g., Brookman-Frazee et al., 2012; Petry et al., 2012). Leather, Spielfogel, et al. (2016) incorporated a project-trained change agent (i.e., someone who demonstrates advanced knowledge and generates interest in the intervention) into the agency setting. The change agent initiated informal discussions about the intervention and offered formal consultation, which was rarely used (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Workshop and consultation

| Author | Nathan & Gorman classification | Sample size | Training topic | Amount of training | Comparison groups | Follow-up | Role of consultation | Outcome measure domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beidas, Edmunds, et al. (2012) | 1 | N= 115 community clinicians | CBT for child anxiety | 6 hr | 3: Routine, Computerized, & Augmented training | 3 months | Weekly for 3 months | F, K, S, Sat. |

| Henggeler et al. (2013) | 2 | N = 161 therapists | Contingency Management for substance abuse | 1 day | 3: Workshop/Resources (WS+); WS+ computer-assisted training (CAT); WS+/ CAT+ supervisory support | 1 year | Biweekly review of barriers to implementation; duration not reported | F, KP |

| Leathers, Spielfogel, et al. (2016) | 2 | N = 57 providers | Keeping Foster Parents Trained and Supported | 16 hr over 4 sessions | 2: TAU versus. Enhanced Training (contact with change agent) | 5 time points over 14-month period | TAU: As needed; Enhanced: change agent offered 6 mo. of informal and formal consultation | P |

| Luoma and Vilardaga (2013) | 2 |

N =22 mental health professionals |

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy | 2 days | 2; training alone; training + 6 sessions phone consultation | 3 months | 6 30-min phone consultations | K, PF, Sat. |

| Accurso, Astrachan- Fletcher, O’Brien, McClanahan, and Le Grange (2018) | 3 | N =7 therapists; N = 11 youth participants | Family-based treatment for anorexia nervosa (+4 DBT skills sessions) | 2 days | None | None | Weekly 1-hr group supervision (number of weeks not reported) | A, F, Cl, T |

| Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012) | 3 | N= 13 therapist/family dyads | Individualized Mental Health Intervention for Children with ASD | 6 hr | None | None | 1 hr twice per month for 5 months | A, Cl, F, K, P, S, Sat. |

| Chard, Ricksecker, Healy, Karlin, and Resick (2012) | 3 | Varies depending on measure (range from N = 237 to ii = 1,107); N = 374 veteran patients | Cognitive Processing Therapy | 3 days | None | 3 years | 6 months of weekly phone consultation with expert trainers | A, C, Cl, I, Sat |

| Chu et al. (2015) | 3 | N = 23 mental health clinicians | CBT for child anxiety and depression | 6 hr | None | 3–5 years | Weekly supervision (duration not reported) | A, P |

| Dorsey et al. (2016) | 3 | N = 180 clinicians | CBT for anxiety, PTSD, depression, and parent management training for behavior problems (“CBT+”) | 3 days; optional annual 1-day booster training | None | Post-assessment was 6-months post-consultation; subsample completed measures 3-months post-consultation | 6 weeks biweekly phone consultation; access to CBT+ listserv | P. S |

| Gellis et al. (2014) | 3 | N = 16 practitioners | Problem-solving therapy in community- based settings for depression | 1 day | None | None | Weekly 30 min phone-based consultation for 6 months; supervisors reviewed audiotaped sessions | A, I (qual) |

| Hamblen et al. (2010) | 3 | N = 111 psychologists, LPCs, and social workers | CBT for postdisaster distress | 2 days | None | None | Biweekly consultation (duration not reported) | A, F, K |

| Leffler et al. (2013) | 3 | N = 28 professional clinicians and psychology trainees | Multi-Family Psychoeducation Psychotherapy for mood disorders | 4, 5, or 7 hr | None | None | Received feedback while facilitating group; 30 min consultation after group | C |

| Lewis and Simons (2011) | 3 | N = 24 therapists from community agencies | CBT for depression | 3 days | None | 8 months | Every 3–5 weeks over 8 months | A, I, P |

| Lu et al. (2012) | 3 | N =25 clinicians | CBT for PTSD | 2 days; 1-day booster 1 year post-training | None | None | Weekly group supervision; submission of audiotaped sessions | F, S, Sat |

| Lyon, Charlesworth- Attie, Stoep, and McCauley (2011) | 3 | N = 18 therapists | Managing and Adapting Practice system for depression and anxiety | 3 half days | None | None | Biweekly, in-person, 90-min group consultation for academic year | A, K, P |

| Lyon et al. (2015) | 3 | N = 11 therapists and supervisors | CBT for children and families | 3 days | None | 3 months | 6 months of expert- provided biweekly 1-hr phone consultation | A, P, S |

| Ngo et al. (2011) | 3 | N = 35 therapists | CBT for depression in disaster-impacted areas | 1–2 days | None | None | 1-hr weekly open group conference call + 1-hr weekly individual phone consultation with review of audiotaped sessions (duration not reported) | K, S, Sat. |

| Petry et al. (2012) | 3 | N = 15 clinicians; N = 78 patients | Contingency management for substance abuse | 2 half-day trainings | None | Post-supervision | Weekly meetings and feedback on supervisors’ ratings of audiotaped sessions until competency reached | Cl, F, S, K, Sat |

| Reese et al. (2016) | 3 | N = 161 clinicians | CBT for OCD | 3 days | None | None | 3 30-min consultation calls | I, P. S |

| Simons et al. (2010) | 3 | N = 12 community mental health therapists; N = 116 clients | CBT for depression | 2 days | None | 1 year | 16 1-hr group phone consultation for 1 year | Cl, s |

| van den Berg et al. (2016) | 3 | N = 16 therapists; N = 19 patients | PE and EMDR for PTSD | 4 days(2 theoretical, 2 technical) for each intervention | None | 2 years | Monthly 4-hr group supervision for trial duration (−19 months) | A, Cl |

Abbreviations: A, attitudes; C, confidence (self-efficacy); CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; Cl, clinical outcome; DBT, dialectical behavior therapy; E, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; F, treatment fidelity or adherence; I, implementation difficulty or barrier—anticipated or actual; Int, intentions; K, knowledge; P, practices or techniques used; PE, prolonged exposure; PF, psychological flexibility; S, skills/competence; Sat, satisfaction/acceptability; T, therapeutic interaction/rapport/working alliance; TAU, training as usual.

3.3.2 |. Summary of findings

Findings indicated that workshops combined with consultation are a successful approach to increase self-reported intervention use, effect change in competence, and improve client outcomes. Results from these studies indicated improved training outcomes among participants who received consultation. For example, Beidas, Edmunds, et al. (2012) found that although all training modalities (routine, computer, and active learning) resulted in limited improvements in therapist adherence and skill, the more consultation calls attended, the higher participants performed on measures of adherence and skill at a three month follow-up. Another study included a comparison of therapists who did and did not receive consultation after an acceptance and commitment therapy workshop on psychological flexibility and burnout (Luoma & Vilardaga, 2013). Those who received consultation had higher psychological flexibility at three month follow-up than those who did not receive consultation. Reese et al. (2016) also reported that among therapists who attended a workshop on OCD treatment, using phone consultation and peer consultation after training was associated with more self-reported use of the intervention. Several studies found that intervention use decreased in the absence of consultation (i.e., when consultation ended or if consultation attendance was poor; Lyon, Dorsey, Pullmann, Silbaugh-Cowdin, & Berliner, 2015; Ngo, Centanni, Wong, Wennerstrom, & Miranda, 2011; Petry et al., 2012), although the presence of a change agent in the organization increased participants’ use of the intervention (Leathers, Spielfogel, Blakey, Christian, & Atkins, 2016) in the absence of formal consultation.

Only one study found a lack of improved training outcomes with ongoing supervision (Henggeler et al., 2013). This study included a comparison of three conditions: (a) workshop only, (b) workshop and access to computer-assisted training (CAT), and (c) workshop, access to CAT, and supervisory support and coaching, and found no differences across conditions. All conditions demonstrated comparable improvements in intervention use, knowledge, and adherence to contingency management for substance use. The authors suggest that the lack of condition differences may have been due to strong organizational support, high practitioner turnover (27% turnover during the study), or the fact that the support was primarily for supervisors (i.e., not direct consultation with therapists implementing the intervention).

Several studies examined outcomes with gold-standard measurements of fidelity (i.e., direct observation of videotaped sessions). Simons et al. (2010) trained therapists in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression and found that therapists demonstrated improved EBI competence 6 and 12 months after training relative to baseline. Lu et al. (2012) used videotaped sessions to provide feedback on delivery of CBT for PTSD to therapists and found that 91% of therapists achieved competency with their first case. Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012) developed a training protocol following recommendations made by Herschell et al. (2010). Their training in an intervention for children with autism was interactive and included opportunities for practicing treatment planning during the training. It also included self-study, ongoing consultation, and feedback on delivery with an actual client. Similar to other studies, Brookman-Frazee et al. (2012) found that observer-rated therapist fidelity during consultation was high and that parent-reported child problem behaviors significantly decreased from pretreatment to follow-up. All three of these studies also examined client outcomes and found improvements in client symptoms after trained therapists delivered the EBI.

3.3.3 |. Limitations of studies reviewed

Despite generally positive findings, there was variability in the type and quality of outcomes measured, the type of training provided, and the study design. Several studies were limited by the lack of emphasis on sustainment and follow-up greater than one year. Many studies included only pre- and post-assessments, or had brief (e.g., 3 month) follow-ups. Studies with longer follow-ups had mixed results (e.g., Leathers, Spielfogel, et al., 2016; van den Berg et al., 2016). Sustainment of gains, especially after the discontinuation of consultation calls, merits further examination.

Measurement issues persist. Many studies used measures that have not been psychometrically evaluated. A notable concern is the number of studies that assessed fidelity and intervention use with only therapist self-reports. Several studies did use direct observation of sessions to assess fidelity, but many relied on therapist-report (e.g., Henggeler et al., 2013; Reese et al., 2016) or administrative claims data (Hamblen et al., 2010). Another used behavioral role plays as an analogue fidelity measure (Beidas, Edmunds, et al., 2012), which is preferred over self-report, but less preferred than observation of in-session behavior. Given limitations in self-reported fidelity measures (Hurlburt, Garland, Nguyen, & Brookman-Frazee, 2010), conclusions from studies that did not use direct observation of fidelity of intervention delivery should be made with caution.

Another concern is the variability in training, including the duration/dose of training and the workshop training content. The length of training ranged from 4 hours to 4 days. Only one study (Leffler, Jackson, West, McCarty, & Atkins, 2013) compared various workshop durations, so it is not known how much training time is sufficient to successfully transfer knowledge or to change practice. The decision for the workshop duration was typically not discussed nor empirically determined. A similar limitation is true for the dosage of consultation calls, where the length and frequency were rarely justified. No studies examined the ideal dosing or delivery of consultation, though this is under study (Monson et al., 2018; Stirman et al., 2013).

3.4 |. Online training with or without consultation

3.4.1 |. Description of studies

Of the 20 unique studies of online training (Table 3), six were Type 1, four were Type 2, and 10 were Type 3. Type 1 and Type 2 studies used between-subjects designs and compared two or more different training approaches. Most Type 3 studies did not include a comparison condition, with the exception of Mallonee, Phillips, Holloway, and Riggs (2018), which compared in-person training to online training. Three studies (Harned et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2015; Ruzek et al., 2014) had sub-studies (Edwards et al., 2017; Harned, Dimeff, Woodcock, & Contreras, 2013; Nowrouzi, Manassis, Jones, Bobinski, & Mushquash, 2015), which were excluded. Sample sizes ranged from 8 to 706 participants working primarily in community mental health and VA settings. Length of training also varied (2–20 hours). The most commonly assessed outcomes were knowledge (14 studies), followed by skill, use of the intervention, and satisfaction with training (11 studies each). Measures of knowledge typically lacked psychometrics. Measures of skill were mostly based on role plays with standardized clients (e.g., Dimeff et al., 2015) or observation of actual therapy sessions (e.g., Rakovshik, McManus, Vazquez-Montes, Muse, & Ougrin, 2016). Intervention use was generally measured by self-report, except for one study that used client report of therapist behavior (Gryglewicz, Chen, Romero, Karver, & Witmeier, 2016). Satisfaction with training was measured using a wide array of measures, some of which have psychometric support (e.g., Kobak, Craske, Rose, & Wolitsky-Taylor, 2013; Kobak, Lipsitz, Lipsitz, Markowitz, & Bleiberg, 2017; Kobak, Wolitzky-Taylor, Wolitzky-Taylor, Craske, & Rose, 2017), but many of which were designed for each study. Two studies examined client outcomes and did not have strict client inclusion or exclusion criteria.

TABLE 3.

Online training

| Author | Nathan &Gorman classification | Sample size | Training topic | Amount of training | Comparison groups | Follow-up | Role of consultation | Outcome measure domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper et al. (2017) | 1 | N = 156 therapists | CBT for eating disorders | ~8–9 hr online training | 2: independent training; support with nonspecialist worker | 6 months | Support Condition Only: 12 30-min phone calls over 20 weeks | K, S |

| Dimeff et al. (2011) | 1 | N = 132 participants | Distress Tolerance DBT module | 2.5 hr (timed with proctors present) | 3; self-study; e-learning course; placebo attention control e-learning course | 2-, 7-, 11-, 15-week | None | C, K, P, Sat |

| Dimeff et al. (2015) | 1 | N = 172 license mental health professionals | DBT Core Strategies |

Online: ~12 hr In-Person: 12 hr |

2; online; in-person | 3 months | None | C, K, P, S, Sat |

| Ehrenreich-May et al. (2016) | 1 | N = 140 community clinicians | CBT for anxiety/panic disorders | 7 hr online training | 3; text-alone; text + online training; text + online + learning community | 3 months | 8 weekly calls for learning community | C, I, K, P, S, Sat |

| Harned et al. (2014) | 1 | N = 181 mental health providers & students in mental health field | Exposure therapy for anxiety disorders | ~10 hr online training | 3; online training, online + ME; online + ME + online learning community | 3 months | Integrated into last 3 weeks of learning community | A, K, P, S, Sat |

| Ruzek et al. (2014) | 1 | N = 168 clinicians | CBT for PTSD | ~4 hr online training | 3; web-based training; web-based training + consultation; no-training control | None | 6 weekly 45–60 min group calls | C, K, P, S |

| Bennett-Levy et al. (2012) | 2 | N = 49 participants | CBT | 12-weeks | 2; online only; online + telephone/Skype support | 4 weeks | Biweekly 15-min support sessions over 12 weeks | C, K, P, S |

| Harned et al. (2011) | 2 | N = 46 mental health providers | Exposure therapy for anxiety disorders | ~2 hr online training | 3; online training; online training + MI; placebo control online training | None | None | A, C, K, P, Sat |

| Rakovshik et al. (2016) | 2 | N = 61 clinicians | CBT for anxiety | 20-hr online CBT training program | 3; internet-based training with consultation worksheet; internet + supervision; delayed control | None | 3 30-min individual supervision sessions once per month | S |

| Stein et al. (2015) | 2 | N = 36 clinicians; N = 136 patients | Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy for bipolar disorder | Online: 12-hr asynchronous online program + learning collaborative; TAU: 12-hr in-person training | 2; Online training; TAU (in- person training) | Monthly follow-up for 12 months posttraining | Online: Monthly 60 min group phone supervision for 3–6 months after training; TAU: onsite supervision as usual; able to contact experts | P |

| Fairburn, Allen, Bailey- Straebler, O’Connor, and Cooper (2017) | 3 | N = 102 therapists | CBT for eating disorders | 9 hr minimum online training | None | None | Up to 12 30-min calls | S |

| Gryglewicz et al. (2016) | 3 | N = 178 participants | QPRT suicide risk assessment and management training | 8–12 hr (within 4 weeks) | None | None | None | A, C, K, Sat |

| Jones et al. (2015) | 3 | N = 78 therapists; N =71 youth | CBT for anxious youth | 20-session, weekly group supervision training model with didactic component | None | None | 20-session weekly group seminar included didactics and supervision | Cl, K |

| Kobak, Lipsitz, et al. (2017) | 3 | N =26 clinicians | Interpersonal therapy for depression | 3–4 hr web-based tutorial | None | 1–3 months after applied training | 45–60 min live remote training (role play) via videoconference with feedback; web-based training portal allowed option to request case consultation | K, Sat |

| Kobak, Wolitzky- Taylor, et al. (2017) | 3 | N = 10 community clinicians; N= 33 patients | CBT for anxiety disorders | Online training time not reported | None | Post-live applied training | 4 60-min remote live training sessions with feedback | Cl, K, S, Sat |

| Kobak et al. (2013) | 3 | N = 39 social workers, psychologists, and graduate students | CBT for anxiety disorders | ~5.5 hr online training; 3 hr live feedback | None | None | None | K, S, Sat |

| Mallonee et al. (2018) | 3 | N = 706 mental health professionals (pre) N = 780 (post) | CBT for PTSD, depression, insomnia, pain, suicidality | Online training time not reported; 2 days in person | 2; in-person; online ”3D” training | None | None | K, Sat. |

| Martin, Gladstone, Diehl, and Beardslee (2016) | 3 | N = 58 clinicians | Family Talk prevention intervention for depression | 4-hr web- based + 3.5 hr face-to-face | None | 4-months | None | P, Sat |

| Persons et al. (2016) | 3 | N =26 clinicians | Progress Monitoring | 60-min orientation + 4 1.5 hr online classes | None | 1 year | Listserv | P |

| Puspitasari, Kanter, Murphy, Crowe, and Koerner (2013) | 3 | Study 1: N = 8 participants; Study 2: N =9 participants | Behavioral Activation | Not specified (“self-paced”) | None | Study 2 only: 6-week follow-up | Studies 1 + 2:3 live 90-min online training sessions | Study 1: P, Sat; Study 2: C, P, S, Sat |

Abbreviations: A, attitudes; C, confidence (self-efficacy); CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; Cl, clinical outcome; DBT, dialectical behavior therapy; F, treatment fidelity or adherence; I, implementation difficulty or barrier—anticipated or actual; Int, intentions; K, knowledge; MI, motivational interviewing; P, practices or techniques used; PF, psychological flexibility; QPRT, Question, Persuade, Refer, Treat; S, skills/competence; Sat, satisfaction/acceptability; T, therapeutic interaction/rapport/working alliance; TAU, training as usual.

3.4.2 |. Summary of findings

Similar to findings regarding in-person workshops alone, there was clear evidence that online trainings can improve therapist knowledge and skill in the short-term. Dimeff, Woodcock, Harned, and Beadnell (2011) compared training in the dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) distress tolerance module across conditions: online training, self-study of treatment manual, and placebo attention control e-learning. The online training resulted in the greatest improvements in therapist-reported use of the intervention, but the manual and online training resulted in similar increases in knowledge and self-efficacy. Other less rigorous studies also demonstrated an increase in CBT knowledge, skill, and use of the intervention after online training (Kobak et al., 2013; Kobak, Lipsitz, et al., 2017; Kobak, Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2017).

Three studies directly compared in-person and online trainings. Stein et al. (2015) found comparable improvements in use of interpersonal and social rhythm therapy for bipolar disorder for an asynchronous online and an in-person training. Similarly, Mallonee et al. (2018) compared in-person training to live “3-D” (i.e., involving interactive virtual worlds) synchronous training for a variety of EBIs. They found that participants in both conditions had significant and comparable gains in knowledge and readiness to implement EBIs, suggesting that online and in-person training may be equally effective. However, other findings are in contrast: Dimeff et al. (2015) compared online training, in-person training, and self-study of a DBT manual and found that knowledge was highest for participants who received online training, although there were no differences for observer-rated proficiency by condition. This study also found that instructor-led training was better than online training at improving motivation to use a more complex strategy (chain analysis) than a simpler skill (validation). This suggests that there may need to be a match between training and treatment strategies, such that more complex treatment strategies may benefit from being taught in person. Consistent with this, Persons, Koerner, Eidelman, Thomas, and Liu (2016) reported that a more straightforward EBI (i.e., measurement-based care; using quantitative measures to monitor symptom change) improved significantly from online training alone.

Two studies examined the role of consultation following online training. Ruzek et al. (2014) conducted an RCT of web-based training approaches for PTSD comparing webbased training and consultation, web-based training alone, and a no-training control condition. They found that participants who received consultation demonstrated greater skill on a standardized client assessment for two of the three skills relative to the other conditions. There were no condition differences on the third skill or on self-reported implementation of the strategies taught in the training, which improved for all conditions. Rakovshik et al. (2016) conducted a similar RCT in which they compared internet-based training with a consultation worksheet, internet-based training with CBT supervision, and a delayed-training control condition. The consultation worksheet asked questions about CBT approaches for the case and whether the therapist had the skills to implement the planned interventions. Those in the consultation worksheet condition turned in these self-report worksheets, but did not discuss them with a supervisor, whereas those in the supervision condition received supervision based on this worksheet. Similar to Ruzek et al. (2014), participants who received supervision had better observer-rated CBT competence than participants in both other conditions. Consistent with in-person training, online training alone does not seem sufficient to improve CBT competence in practice, but consultation improves outcomes.

Other studies examined additional enhancements to webbased trainings. Cooper et al. (2017) conducted an RCT of web-based training for CBT for eating disorders. In one condition, participants completed the training independently and in the other condition they received support by a nonspecialist worker who encouraged the participants to complete all aspects of the online program. There were no condition differences on competence in the intervention following training. Similarly, Bennett-Levy, Hawkins, Perry, Cromarty, and Mills (2012) provided brief (15-minute) post-training support sessions for a subset of therapists receiving training and also did not find condition differences in confidence, knowledge, skills, or self-reported use of the intervention. However, those who received the support sessions were significantly more likely to complete all elements of the training program. Another study trained therapists in CBT for anxiety and panic (Ehrenreich-May et al., 2016). Participants were randomized to manual-alone, online training and manual, or online training, manual, and a learning community that incorporated weekly conference calls and online discussions via Twitter. Participants who were engaged in the learning community had the highest clinical proficiency ratings based on role play performance, but this effect was not maintained at two and three month follow-ups. Harned et al. (2014) conducted an RCT that incorporated a web-based learning community with online training and motivational enhancement. Other conditions included online training alone and online training plus a motivational enhancement. Results indicated that all conditions had increased self-efficacy and self-reported use of exposure, but the learning community condition had the highest knowledge, better attitudes, and higher clinical proficiency. The motivational enhancement component did not improve attitudes relative to the online training alone condition in this study, which is in contrast to a previous similar study conducted by Harned, Dimeff, Woodcock, and Skutch (2011), that provided the motivational enhancement in person rather than online. Taken together, studies examining enhancements to web-based trainings found that brief support after training improved compliance to training requirements but did not have a substantive effect on key training outcomes. Online learning communities may improve outcomes, but sustainability of these gains merits further examination.

3.4.3 |. Limitations of studies reviewed

Findings indicated that online training can be an effective method for training, but there were variants of online training and questions about the ideal approach to online training. Online training had more Type 1 and Type 2 studies than any other category. Many Type 3 studies were limited by only using within-subject designs. Only three studies made direct comparisons between online training and in-person training (Dimeff et al., 2011; Mallonee et al., 2018; Stein et al., 2015). All studies examining online training demonstrated some positive effects. However, additional work is needed to determine strategies to continue improving online trainings, especially given that satisfaction for in-person trainings may be rated more highly (e.g., Mallonee et al., 2018).

Regarding measurement, several studies used standardized client role plays to measure clinical skill (e.g., Rakovshik et al., 2013; Ruzek et al., 2014), and one study used observation of therapy sessions (Rakovshik et al., 2016). Kobak and colleagues (2013; Kobak, Lipsitz, et al., 2017; Kobak, Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2017) used standardized clients as a tool for training in addition to using it as a method for measuring skill. Although measures of clinical skill were relatively strong in several studies, measures of clinical use were generally limited by reliance on therapist self-report.

Another limitation was short follow-ups. The longest follow-up was one year, but the majority were three months, and several studies had no follow-up. Some studies that did include follow-ups found that some gains were not maintained (e.g., Ehrenreich-May et al., 2016; Persons et al., 2016). In addition, the length of training varied widely, making direct comparison of studies difficult and leaving unanswered questions about optimal length of training.

To address these limitations, future studies should compare online training with consultation to in-person training with consultation, include longer follow-ups, and compare synchronous (trainers and trainees move through training at the same time on a set schedule) to asynchronous (self-paced) training. In addition, online trainings often incorporated interactive components, such as completing virtual role plays with other attendees as an adjunct to training. However, there has not been empirical study of what components and teaching strategies for online training are most effective and likely to enhance the probability of therapist behavior change.

3.5 |. Train-the-trainer

3.5.1 |. Description of studies

There were four TT studies involving training supervisors or select therapists who in turn trained other staff (Table 4). These studies involved expert-led group training sessions for trainees to be eligible to train other participants. The first study (Martino et al., 2010) was Type 1 and randomized 12 outpatient programs to one of three conditions for receiving training in motivational interviewing (MI). The other studies were Type 3. Nakamura et al. (2014) used a within-subject multiple baseline design and included four supervisor–therapist dyads. Southam-Gerow et al. (2014) trained therapists in an evidence-informed model of care, Managing and Adapting Practice (MAP). This study did not randomize therapists to conditions but described outcomes for therapists who were trained by expert trainers, as well as for those trained via a TT model. The final study (Wade et al., 2014) examined a TT approach for a post-disaster mental health training program.

TABLE 4.

Train-the-trainer

| Author | Nathan & Gorman classification | Sample size | Training topic | Amount of training | Comparison groups | Follow-up | Role of consultation | Outcome measure domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martino et al. (2010) | 1 | N = 92 therapists | Motivational interviewing for substance use problems | Self-study: 20 hr; Expert-led: 15-hr; Train-the-trainer: 15 hr + additional 15 hr for trainers | 3; Self-study; Expert-led; Train-the-trainer | Postsupervision and 12-week follow-up | Expert: 3 monthly individual face- to-face sessions to review audiotaped sessions; Train- the-trainer: Expert calls + monthly consultation calls for trainers (duration not reported) | F, S, Sat |

| Nakamura et al. (2014) | 3 |

N = 4 supervisors N = 4 therapists |

Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems | Supen’isors: three 2-day workshops | None | None | None | S |

| Southam- Gerow et al. (2014) | 3 |

N = 504 for national training pathway; N = 283 for agency supervisor pathway (train-the-trainer); N= 1,172 youth clients |

Managing and Adapting Practices (MAP) | 40 hr; Supen’isor training: additional 16 hr of training | None | None | 6 months of biweekly 1-hr phone consultation and submission of materials for 2 cases; Supen’isor training: additional 6 months of 1-hr consultation calls | Cl, F, P |

| Wade et al. (2014) | 3 |

N = 40 trainers; N = 684 practitioners |

Skills for Psychological Recovery |

Trainers: 2-days + competency assessment; Practitioners: 1 day; Both groups: online booster modules at 3- and 6-months |

None | 3- and 6-month post-training | Trainers: 1-hr teleconference at 3- and 6-months to receive advice, support, and feedback; feedback on actual training sessions for a subset of trainers | C, I, P; Trainers Only: S |

Abbreviations: A, attitudes; C, confidence (self-efficacy); Cl, clinical outcome; F, treatment fidelity or adherence; I, implementation difficulty or barrier—anticipated or actual; Int, intentions; K, knowledge; P, practices or techniques used; PF, psychological flexibility; S, skills/competence; Sat, satisfaction/acceptability; T, therapeutic interaction/rapport/working alliance.

Sample sizes ranged from four supervisor–therapist dyads to 684 practitioners working in community mental health. The length of training ranged from 1 day to 56 hours. Three out of four studies examined therapist and/or trainer competence. Measures of competence included observer ratings using standardized scales (Martino et al., 2010; Nakamura et al., 2014). One study had practitioners use a (non-standardized) measure to assess trainers’ competence (Wade et al., 2014). The other most frequent outcomes were treatment fidelity and EBI use, measured in two studies. Fidelity was measured using observer ratings of submitted session recordings (Martino et al., 2010; Southam-Gerow et al., 2014). Finally, EBI use was measured via therapist-report (Wade et al., 2014) and claims data (Southam-Gerow et al., 2014). Southam-Gerow et al. (2014) measured client outcomes and did not have client inclusion or exclusion criteria.

3.5.2 |. Summary of findings

Martino et al. (2010) conducted the most rigorous of the TT studies and compared self-study, expert-led training, and TT conditions. They found improvements in therapists’ MI performance for the expert and TT conditions, such that a greater percentage performed MI adequately compared to those in the self-study condition. However, contrary to expectations, participants in the expert-led condition achieved higher standards of MI performance than those in the TT condition at 12-week follow-up. The authors suggest that this may be because trainers for the TT condition had no prior MI training and were rated as covering MI material less extensively and skillfully than experts during the workshops they conducted. Southam-Gerow et al. (2014) similarly found that participants who received training from expert trainers had higher proficiency ratings than those trained by trainers in the TT condition. However, overall ratings of therapists’ portfolios were in the proficient range, and time to successful completion of training was comparable for both types of training. These findings highlight the promise of the TT model to achieve positive therapist training outcomes, though not at the level of expert-led trainings.

The other two TT studies also suggest positive results, although methodological limitations preclude firm conclusions. Nakamura et al. (2014) completed observational coding of four therapist–supervisor dyads and found that supervisors improved in their teaching (i.e., style; content) and therapists improved in their EBI performance. Similarly, Wade et al. (2014) found that participants met minimum trainer-rated competency standards to conduct trainings and were rated by other therapists as having high competence in delivering training. Furthermore, therapists who received training from those participants had increases in confidence in using the intervention.

3.5.3 |. Limitations of studies reviewed

Herschell et al.’s (2010) prior review noted that, although potentially cost-efficient, there were limited data to support the use of the TT method. The four studies conducted since the 2010 review provide additional evidence for its support, but gaps remain. Only one study was Type 1 (Martino et al., 2010); the others did not randomize participants, limiting the ability to compare TT to other training approaches. Further, the studies conducted by Nakamura et al. (2014) and Martino et al. (2010) were conducted within a small number of agencies, which limits generalizability.

Other limitations are similar to those noted for other training approaches. For example, follow-up length was absent (Nakamura et al., 2014) or limited (longest was 6 months; Wade et al., 2014); thus, sustainability of this approach is unknown. Client outcomes were only measured in one study (Southam-Gerow et al., 2014) and only represented a subset of cases. Client outcomes may be particularly important in a TT model, where the knowledge passed on to therapists may not be as comprehensive as the training provided to supervisors, which could in turn affect client outcomes. The specific amount and content of consultation provided to supervisors and trainees warrants further examination, as does fidelity to training and consultation by TT trainers.

3.6 |. Intensive training

3.6.1 |. Description of studies

Twenty-two studies evaluated intensive training, which was defined as including at least 20 hours of training, as well as two or more additional training components (Table 5). Among studies of intensive training, only one was Type 1 (Kolko et al., 2012). Three were Type 2, of which two were part of the Beck Initiative. The Beck Initiative studies (German et al., 2017; Stirman et al., 2017) involved condition comparisons with sufficient sample sizes for planned analyses, but neither included randomization to a condition. Webster-Stratton, Reid, and Marsenich’s (2014) randomized trial was considered Type 2 due to lack of clear inclusion and exclusion criteria. The remaining 18 studies were Type 3. All except one of the Type 3 studies (Smith et al., 2017) did not have comparison conditions. Most were uncontrolled within-subjects designs, but many included follow-ups of 2 years after initial training.

Sample sizes ranged from 5 to 1,034 therapists practicing in community mental health, school-based, and VA settings. Intensive training models ranged from the minimum of 20 training hours for inclusion in this category to up to 40 training hours prior to consultation or booster training. In terms of outcome measures, therapist skill was most frequently measured (16 of 22 studies). The Beck Initiative studies all included measures of therapist skill based on observations of therapy session recordings, as did a subset of VA studies (Smith et al., 2017 (study 2); Karlin et al., 2012; Karlin, Trockel, Taylor, Gimeno, & Manber, 2013; Walser, Karlin, Trockel, Mazina, & Barr Taylor, 2013). Several other studies also used observer-rated measures of therapist skill. Confidence using the intervention was the second most frequently measured outcome (13 studies), followed by attitudes (9 studies). In most studies, confidence was measured with questions developed for the study. Attitudes were measured with psychometrically supported measures (the EBPAS) in three studies (Karlin et al., 2012; Kolko et al., 2012; Navarro-Haro et al., 2019) but were measured using study-specific measures for the others. Studies that measured client outcomes (n = 6) had no or limited client exclusion criteria.

Besides consultation, additional components of intensive trainings included homework between training sessions, therapy session tape review with feedback, role play feedback, advanced booster trainings, and a learning collaborative. Studies were part of several different initiatives, including statewide efforts to implement parent–child interaction therapy (PCIT; Beveridge et al., 2015; Jackson, Herschell, Schaffner, Turiano, & McNeil, 2017), examination of adoption of DBT in community clinics (Herschell, Lindhiem, Kogan, Celedonia, & Stein, 2014; Navarro-Haro et al., 2019), VA initiatives for training in EBIs (Karlin et al., 2012, 2013; Manber et al., 2013; Ruzek et al., 2017, 2016; Smith et al., 2017; Walser et al., 2013), and the Beck Initiative for training in Cognitive Therapy (as described in Creed et al., 2013; Creed, Stirman, & Evans, 2014; Creed, Wolk, Feinberg, Evans, & Beck, 2016; German et al., 2017; Stirman et al., 2017).

3.6.2 |. Summary of findings

Studies of intensive training approaches demonstrated evidence for improvements in therapist knowledge, intervention use, and observer-rated competence. All except one study (Navarro-Haro et al., 2019) included formal consultation and many included expert feedback on recorded therapy sessions. Webster-Stratton et al. (2014) compared training conditions with and without consultation. Those who received ongoing consultation and feedback on recorded sessions demonstrated higher fidelity in several domains, suggesting that consultation enhanced adherence. However, fidelity in some areas, such as conducting role plays, was still limited even in the presence of phone consultation. This suggests that phone consultation was insufficient for addressing some of the challenging skills taught as part of the intervention.

Consultation appears to be a key element of intensive trainings. VA training initiatives led to improvements in competency after consultation based on observer-rated sessions (e.g., Karlin et al., 2012, 2013; Walser et al., 2013). Similarly, the Beck Initiative included consultation calls and examined outcomes across multiple settings (i.e., schools; Creed et al., 2013; community settings; Creed et al., 2016). These studies found that there was a significant increase in therapists’ competency in delivering cognitive therapy at 6-month follow-up. Furthermore, over 70% of therapists achieved the competency threshold by this final assessment. Stirman et al. (2017) compared two consultation call formats for participants in the Beck Initiative training. One condition received individual feedback from expert consultants who reviewed full audio-recorded therapy sessions. The other condition received group consultation in which short segments of tape were reviewed in group consultation with the expert consultant. At the end of consultation, the majority of therapists in both groups achieved the required level of competence in cognitive therapy. At 2-year follow-up, participants in the individual feedback condition who had high competence scores at post-consultation had a decrease in competence, but those in the group feedback condition had increases in competence. This provides support for group consultation, which reduces the amount of expert consultation time required. However, nearly half of therapists were ineligible for recertification at the 2-year follow-up, largely due to turnover. Herschell et al. (2014) also reported low rates of DBT training completion (55%) due to turnover.

Intensive trainings tend to be cost- and resource-intensive because of the amount of expert time required. For example, Kolko et al. (2012) randomized participants to either a learning community model (i.e., workshops and consultation) or training as usual (TAU) per agency standards. The former condition required more resources (i.e., expert time), with therapists attending an average of 22.8 hours (SD = 9.1) of workshop training and 9.8 hours (SD = 5.2) of consultation. Therapists in the active condition demonstrated greater improvements in knowledge and self-reported EBI use 6 months after training compared to therapists receiving TAU. These gains were generally maintained at 12- and 18-month follow-ups. German et al. (2017) examined a modification to the Beck Initiative training model that aimed to reduce the need for expert time and resources. They compared in-person workshops with expert-led consultation to web-based training followed by peer-led consultation. Both conditions demonstrated comparable knowledge gains and improvements in therapy competence. However, those who received the web-based training with peer-led consultation were significantly less likely to complete the training than those who received in-person training. Despite this limitation, the model is a promising approach given that web-based training required only 8% of the resources of the in-person training. Furthermore, there are strategies that may improve engagement and completion of a web-based training (e.g., training with a cohort of trainees, pay increases for EBI certification).

3.6.3 |. Limitations of studies reviewed

As in other categories, most intensive studies were within-subject designs without comparison groups. However, these studies are notable for the number of studies with follow-ups, with many having at least a 6-month or 1-year follow-up. This extended contact involved booster training, consultation, and/or tape review. That said, studies of sustainability would benefit from longer follow-ups, as a minimum of 2 years typically represents the duration needed to determine EBI sustainability (Jackson et al., 2017; Stirman et al., 2017).

Consistent with other training methods, limitations related to outcome measurement persist. Studies relied exclusively on self-reports (e.g., Herschell et al., 2014) and used measures that lacked adequate psychometrics (e.g., Jackson et al., 2017). Several studies addressed previous limitations by using observational measures of therapist competence (e.g., the Cognitive Therapy Ratings Scale; CTRS: Young & Beck, 1980), but the lack of their widespread use may be due to these measures being time-intensive and having limited feasibility in low-resourced settings. In addition, there may be some conflation in the literature due to variability in quality of outcome measurement. Specifically, intensive training models have the most rigorous measurement, whereas less intense models tend to rely on self-report, which may inflate outcomes. Thus, there may be even greater differences between intensive and non-intensive training approaches.

The variability in the timing and length of training merits attention. Evaluated approaches were consistent in being intensive, but the configurations for the timing of the multiday workshops varied. For example, Kolko et al. (2012) had four full-day workshops once a week for a month, whereas Navarro-Haro et al. (2019) had two separate blocks of 5-day workshops approximately 6 months apart. Other intensive trainings (e.g., Jackson et al., 2017) had an initial 40 hours of training over several days and an advanced booster training 6 months later. The Beck Initiative studies (Creed et al., 2013, 2016; German et al., 2017; Stirman et al., 2017) did not space out the trainings but included substantial consultation and feedback that was spread out over time. Given that massed and spaced trainings may differ, there is need for research on how spacing of training may enhance training outcomes and/or improve consolidation of learning.

4 |. DISCUSSION

This review of therapist training studies confirms and extends findings from previous reviews (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell et al., 2010; Rakovshik & McManus, 2010). Therapist training in EBIs has been a growing area of research since 2010, with 76 studies added to the literature. Most studies examined intensive training, in-person workshops with consultation, or online workshops. Only four studies examined TT methods since the last review, and nine studies examined in-person workshops only. Consistent with conclusions from prior reviews, therapist knowledge and attitudes toward EBIs improve after attending a workshop; yet workshops alone are unlikely to increase EBI use. There remains limited evidence that those seeking to change therapist behavior should rely solely on manuals and workshops without additional consultation or other post-training activities. An extension to prior work is that this appears to be true regardless of whether training is conducted in person or online. Importantly, this review suggests that training is more likely to translate into increased EBI use and improved fidelity if therapists are supported by consultation after training, although major questions about optimal dosage and content remain.

This review notably expands upon previous work in the areas of online training, intensive training, and TT approaches. Recent studies suggest that more straightforward EBIs (i.e., those involving one component, such as measurement-based care) can be taught with comparable outcomes using online or in-person trainings, but more complex EBIs (i.e., involving several components or more nuanced application, such as CBT; Wolk et al., 2019) might benefit from being taught in person. Additional work is needed to identify which EBIs can be taught effectively online. Intensive training appears to have the most promise for increasing competence and use of EBIs, including more complex ones. However, limitations to intensive trainings include the amount of resources needed, uncertainty about sustainability, and investment in staff who may turnover (Beidas et al., 2016; Okamura et al., 2018). The TT model demonstrates the most promise with respect to sustainability, but raises important questions about the benefits of sustaining “watered down” EBIs (Demchak & Browder, 1990) if high fidelity is not achieved, as client outcomes were rarely examined in these studies. Without concomitant studies examining clinical outcomes, the merit of TT (and other intensive training) models will remain unclear.

Studies included in this review also included assessment of therapist variables (e.g., characteristics of the trainee therapists). There were mixed findings, such as whether having previous experience with the intervention leads to more or less change in knowledge and attitudes after training. However, among therapists who attended workshops followed by consultation, more positive attitudes toward EBIs generally predicted better training outcomes (e.g., adherence, skill, use of the intervention). A recent meta-analysis concluded that therapist experience has only a modest impact on client outcomes (Walsh, Roddy, Scott, Lewis, & Jensen-Doss, 2018), but there are other potential therapist variables for evaluation. For instance, there is evidence that therapist clinical practices (i.e., use of cognitive, behavioral, family, and psychodynamic techniques) are related to therapist background characteristics (e.g., type of graduate training; Becker-Haimes, Lushin, Creed, & Beidas, 2019). Some studies have begun to examine therapist constructs such as psychological flexibility (e.g., Richards et al., 2011), which may affect openness to learning and therapists’ ability to adopt new methods. Assessing a broad range of therapist constructs might allow for better tailoring of training methods to learner needs. As measurement across training studies becomes more standardized and meta-analysis becomes feasible, therapist variables should be examined as moderators.