Abstract

Sepsis is a heterogeneous syndrome clinically and biologically, but biomarkers of distinct host response pathways for early prognostic information and testing targeted treatments are lacking. Olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4), a matrix glycoprotein of neutrophil-specific granules, defines a distinct neutrophil subset that may be an independent risk factor for poor outcomes in sepsis. We hypothesized that increased percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils on sepsis presentation would be associated with mortality. In a single-center, prospective cohort study, we enrolled adults admitted to an academic medical center from the emergency department (ED) with suspected sepsis [identified by 2 or greater systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria and antibiotic receipt] from March 2016 through December 2017, followed by sepsis adjudication according to Sepsis-3. We collected 200 µL of whole blood within 24 h of admission and stained for the neutrophil surface marker CD66b followed by intracellular staining for OLFM4 quantitated by flow cytometry. The predictors for 60-day mortality were 1) percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils and 2) OLFM4+ neutrophils at a cut point of ≥37.6% determined by the Youden Index. Of 120 enrolled patients with suspected sepsis, 97 had sepsis and 23 had nonsepsis SIRS. The mean percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was significantly increased in both sepsis and nonsepsis SIRS patients who died (P ≤ 0.01). Among sepsis patients with elevated OLFM4+ (≥37.6%), 56% died, compared with 18% with OLFM4+ <37.6% (P = 0.001). The association between OLFM4+ and mortality withstood adjustment for age, sex, absolute neutrophil count, comorbidities, and standard measures of severity of illness (SOFA score, APACHE III) (P < 0.03). In summary, OLFM4+ neutrophil percentage is independently associated with 60-day mortality in sepsis and may represent a novel measure of the heterogeneity of host response to sepsis.

Keywords: biomarkers, critical care, flow cytometry, olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4), outcomes, sepsis

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis, defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction due to a dysregulated host response to infection, remains a leading cause of death in the United States lacking successful targeted treatments (1–4). However, this clinical syndrome encompasses biologically heterogenous mechanisms which present the potential for identification of mechanistic pathways of organ dysfunction in sepsis that may differentially respond to therapy (5–9). Some experimental studies have recently focused on clinically relevant models of pneumonia and sepsis that include antibiotic therapy, which may represent a step forward in modeling clinical sepsis (10). However, there remains a need for clinical studies of sepsis that include translational markers of early sepsis and key pathways of injury.

Neutrophils have long been known to play a major role in the initial inflammatory pathway in sepsis (11, 12). There is growing evidence that neutrophil-related pathways may be directly linked to the development of sepsis-related organ failure and death (13–19). In our prior transcriptional study of whole blood published in this Journal, olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4) was the most upregulated gene associated with the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and shock among adults with sepsis (20). OLFM4 is a matrix glycoprotein of neutrophil-specific granules that is present at detectable levels in 20%–30% of circulating neutrophils in healthy adults, defining a distinct neutrophil subset that can be measured using flow cytometry (21, 22). In children with septic shock, the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was independently associated with increased organ dysfunction and death (23). In addition, in a sepsis mouse model, OLFM4 may downregulate neutrophil bactericidal activity in the presence of infection, and OLFM4-null mice were at a decreased risk of death (21, 24, 25). Finally, among patients undergoing major surgery, increased OLM4 gene expression was associated with postsurgical sepsis and shock mortality (26), and recently, OLFM4 gene polymorphisms have been identified as potential mediators of postsurgical septic shock mortality (27). These data from independent populations and across the translational spectrum suggest that percentage of circulating neutrophils with OLFM4+ matrix glycoprotein may affect the neutrophil-related response to sepsis.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that increased percentage of OLFM+ neutrophils would be associated with death, shock, and respiratory failure among adults presenting to the emergency department (ED) with sepsis.

METHODS

Human Subjects

We included prospectively enrolled patients with suspected sepsis admitted to University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center from the emergency department between March 2016 and November 2017. This was a substudy of the ongoing National Institutes of Health (NIH)-supported Early Assessment of Renal and Lung Injury (EARLI) cohort study, the details of which have been previously published (15, 28, 29). For rapid identification for the present study, we prospectively enrolled patients with suspected sepsis who were (28) prescribed systemic antimicrobial therapy (physician-suspected infection), (24) triaged for admission either in a step-down unit or the intensive care unit (ICU), and (23) met at least two systemic inflammatory response criteria (30). Sepsis diagnosis according to Sepsis-3 was subsequently confirmed (31). Patients were excluded (28) when the presenting white blood cell (WBC) count was < 1,000/mm3, as isolation of neutrophils for flow cytometric staining would be challenging and unreliable (24), when flow cytometry testing could not be performed within 48 h of sample acquisition (most within 24 h) (23), and for patients with chronic, ventilator-dependent respiratory failure.

Patient Selection and Consent

Patients were included at the time of the first study blood sample draw with an initial waiver of consent to obtain a fresh sample of blood for immediate flow cytometry testing. Subsequent written informed consent was obtained from the patient or their surrogate, with the exceptions of patients expiring before informed consent could be obtained and patients whose medical condition precluded informed consent and for whom a surrogate could not be identified after 28 days, for whom a full waiver of consent was approved. We utilized SIRS to screen for patients for our study to aid in earlier identification and enrollment of patients recognizing that a subset would end up being adjudicated as nonsepsis SIRS.

Biological Specimen Collection, Processing, and Measurements

All blood specimens were drawn within 24 h of hospital admission in an EDTA tube. We prospectively collected and processed 200 µL of whole blood for flow cytometric analysis. Unless immediately processed for flow cytometry, the sample was stored at 4°C for no greater than 48 h. Flow cytometric staining of cells for OLFM4+ was performed as previously described by Welin et al. (22). Briefly, red cell lysis (BD PharmLyse) followed by surface staining using anti-CD66b was performed (Alexa Fluor 647, Clone: G10F5, BD Biosciences). The cells were fixed for 30 min using 2% paraformaldehyde, washed with water, and then permeabilized with ice-cold methanol and acetone (1:1) for 5 min. Cells were then washed with PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), blocked with 1:100 Human Fc block (BD Biosciences), and then stained with rabbit anti-OLFM4 diluted to 1:200 (Abcam ab96280) for 1 h. Cells were again washed and stained with the secondary antibody donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 at 1:800 (Invitrogen).

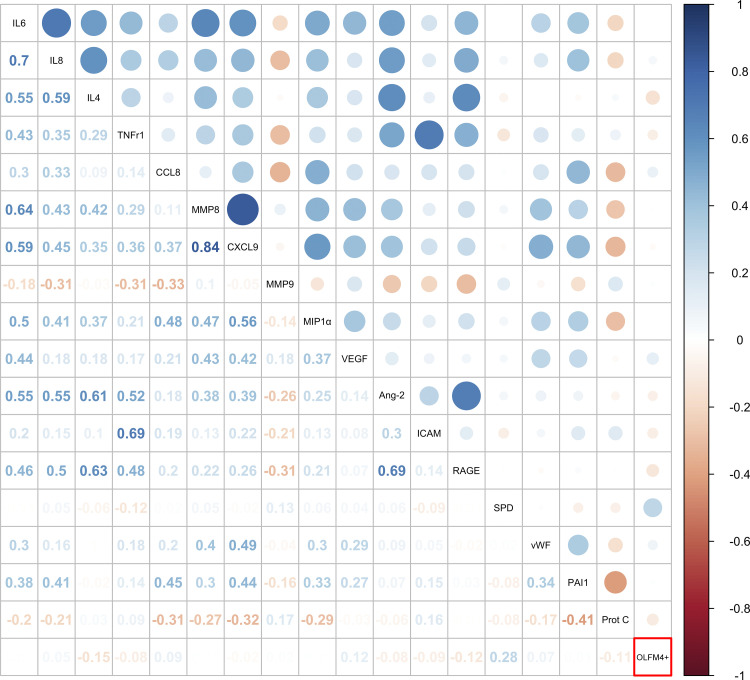

Plasma biomarkers of inflammation and injury were measured to determine correlation with neutrophil percentage of OLFM4+ among patients with sepsis-associated organ dysfunction. Interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, IL-4, tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (TNFr1), chemokine ligand 8 (CCL8), matrix metallopeptidase 8 (MMP8), CCL9, MMP9, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP1α), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM), receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), surfactant protein D (SP-D), and von Willebrand factor (vWF) were measured using a MAGPIX multiplex instrument (Luminex; Austin, TX) with single replicates. Measurement of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and protein C (Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, TX) were conducted in duplicate using ELISA.

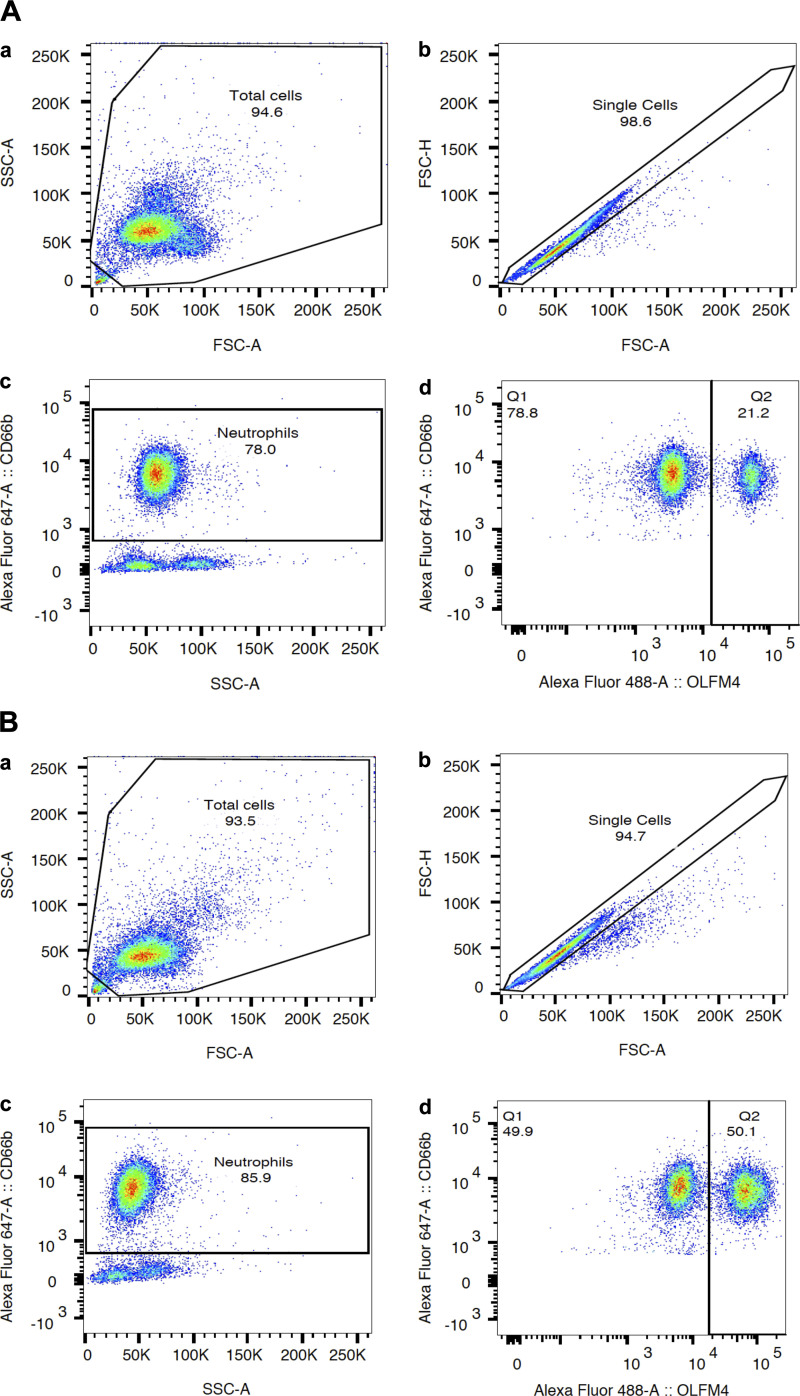

Data were collected on a single BD LSR Fortessa flow cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc.). All measurements were carried out by one of three coauthors (Fang, Clemens, and Kangelaris). Investigators performing flow cytometry were blinded to patient characteristics outside of inclusion/exclusion criteria. The gating strategy to identify percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils is described in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of percentage of olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4+) neutrophils in a patient with “normal” OLFM4+ percentage (A) and elevated OLFM4 percentage (B). Gating strategies are shown in both A and B. Aa and Ba: selection of total cells defined as leukocytes with appropriate forward (FSC-A) and side (SSC-A) scatter patterns. Analyzed cells are surrounded with a black line. Ab and Bb: selection of single cells eliminating clumped cells. Ac and Bc: fluorescence markers used to identify neutrophils (CD66b positive). Ad and Bd: percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils [analysis restricted analysis to neutrophils identified in Ac and Bc due to our observation as well as published data showing the nonneutrophil leukocytes (mononuclear cells, basophils, eosinophils), which do not express OLFM4] (22). A: nonelevated olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4) level: 78% of leukocytes were neutrophils (Ac) and 21% of neutrophils were OLFM4+ (Ad). B: elevated OLFM4 level: 85% of leukocytes were neutrophils (Bc) and 50% of neutrophils were OLFM4+.

Collection of Clinical Variables and Phenotyping

Using the electronic medical record, research coordinators collected clinical data on all subjects. Data collected at enrollment included patient demographics, components of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III score, hemodynamic data, laboratory values included in the sepsis-related organ failure assessment (SOFA) score (32), and the need for vasopressors and mechanical ventilation.

Sepsis diagnosis was adjudicated by experienced intensive care physicians, taking into account the presence of underlying infection and alternative presentations of nonsepsis SIRS. The diagnosis of sepsis was confirmed by SOFA score of at least 2 (33). Type of sepsis was subsequently classified as pulmonary, nonpulmonary, both, or none. Septic shock was defined as a systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg and the need for vasopressor support within 5 days of enrollment to the study (30, 33). Patients were defined as having ARDS if they met criteria as defined by the Berlin definition within 24 h of study enrollment (20). To study a clearly defined clinical phenotype for the ARDS secondary analysis, patients were excluded (n = 12) if they had an equivocal diagnosis of ARDS based on chest radiograph or absent arterial blood gas or if they did not receive positive pressure ventilation. Mortality was defined as death to hospital discharge or at 60 days. Comorbidities including active cancer, cirrhosis, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) were also adjudicated. Variables obtained from manual chart review (by Kangelaris) included closest/concurrent white blood cell count (WBC), absolute neutrophil count (ANC), and band count to the flow cytometry sample draw.

Data Analysis

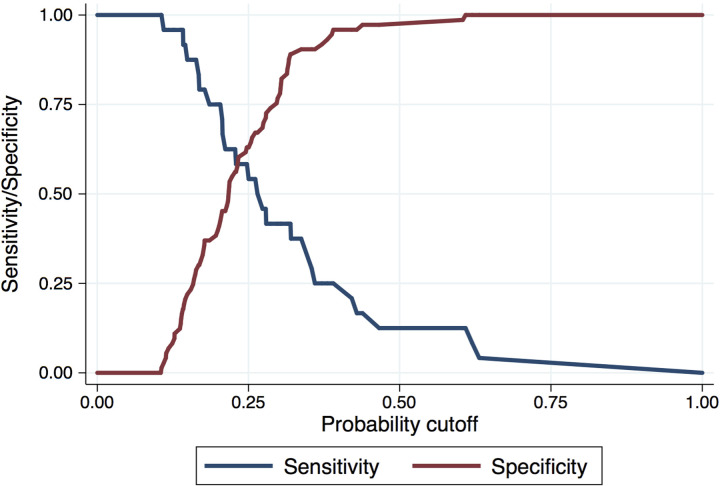

The primary predictor was the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils. Initial analyses tested OLFM4+ as a continuous variable. We hypothesized a priori that there is a wide range of normal OLFM4+ neutrophil percentages and that there would be a detectable clinical association at a threshold level around ∼40% OLFM4+ neutrophils, based on the distribution of OFLM4+ neutrophils among children with prolonged organ dysfunction (23) and nonseptic patients in prior studies (21, 22). We then finalized the cut point using the Youden Index (34, 35) post hoc to maximize sensitivity and specificity for 60-day mortality. We dichotomized patients for subsequent analyses at the final cut point of 37.6%.

The primary outcome was 60-day hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included development of shock, the need for mechanical ventilation, and ARDS. Covariates in multivariate analyses with mortality included age, sex, race, active cancer, cirrhosis, ESRD, band count, ANC, WBC, SOFA score, and APACHE III score. These were adjusted serially to avoid overfitting. We also performed a multivariate model analysis adjusting for age, sex, WBC, and APACHE III to determine if combined regression modeling would affect the results.

For bivariate analyses, we used the appropriate parametric and nonparametric tests. Logistic multivariate regression was used for analyses of the association between OLFM4+ percentage and mortality. The log-rank test was used to compare survival duration between high and normal OLFM4+ groups. Analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

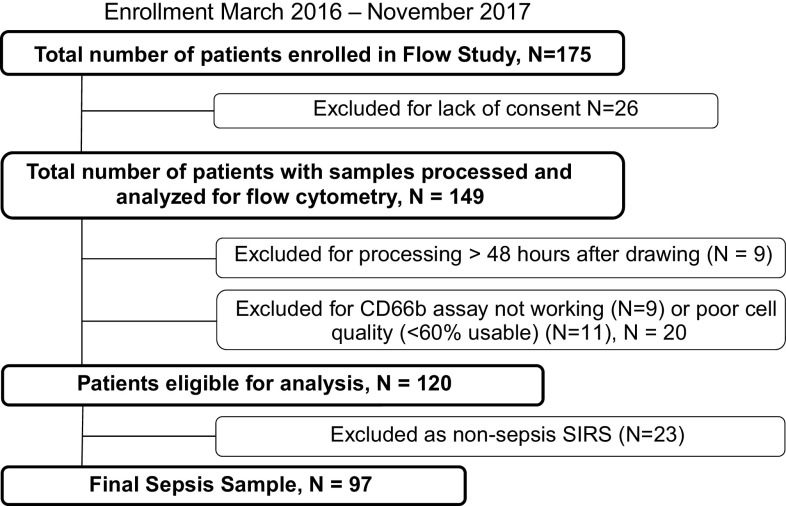

Of 175 patients initially enrolled, 55 were excluded (Fig. 2), resulting in 120 remaining patients. Although the primary analysis was focused on 97 patients meeting physician-adjudicated sepsis, an initial comparison of clinical characteristics and OLFM4 percentage among patients with sepsis compared with the 23 patients adjudicated as nonsepsis-related SIRS is presented in Table 1. The initial severity of illness as measured by APACHE III and SOFA was higher in the patients with sepsis compared with the patients with SIRS (APACHE III: 83 ± 42 vs. 62 ± 30, P = 0.02; SOFA 11.0 ± 4.0 vs. 8.6 ± 2.9, P = 0.01). Also, shock was more prevalent in the sepsis group (52% vs. 22%, P = 0.01). There were no other significant differences in demographics or comorbidities between the two groups, and 60-day mortality did not differ significantly (sepsis 25% and SIRS 22%, P = 0.76). Primary presenting diagnoses of nonsepsis SIRS are presented in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of enrollment of adults with suspected sepsis between March 2016 and November 2017.

Table 1.

Differences between nonsepsis SIRS and sepsis in 120 adults admitted with suspected sepsis

| Characteristic | SIRS Only n = 23 (19%) | Sepsis n = 97 (81%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 59 ± 22 | 66 ± 16 | 0.08 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 12 (52) | 56 (58) | 0.63 |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 4 (18%) | 33 (34%) | 0.28 |

| Black | 4 (18%) | 9 (9%) | |

| Latino | 4 (18%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Pacific Islander | 0 | 2 (2%) | |

| White | 8 (36%) | 37 (38%) | |

| Other | 3 (13%) | 10 (10%) | |

| Admitted to the ICU | 17 (74%) | 81 (84%) | 0.29 |

| Active cancer | 6 (26%) | 24 (25%) | 0.89 |

| Cirrhosis | 1 (4%) | 5 (5%) | 0.87 |

| ESRD | 1 (4%) | 9 (9%) | 0.44 |

| Illness severity | |||

| SOFA score day 1 | 8.6 ± 2.9 | 11.0 ± 4.0 | 0.01 |

| APACHE III | 62.0 ± 30.2 | 83.0 ± 41.7 | 0.02 |

| WBC | 11.2 ± 6.1 | 16.6 ± 10.4 | 0.02 |

| ANC | 9.5 ± 5.6 | 13.8 ± 9.3 | 0.03 |

| %PMNs OLFM4+ | 28.9% ± 16.2% | 26.6% ± 15.5% | 0.51 |

| Clinical outcomes | |||

| 60-day mortality | 5 (22%) | 24 (25%) | 0.76 |

| Shock | 5 (22%) | 50 (52%) | 0.01 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 7 (30%) | 42 (43%) | 0.26 |

Values are means ± SD. ANC, absolute neutrophil count; APACHE III, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation severity of disease classification system, which ranges from 0 to 299, with higher scores indicating higher severity of illness; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; OLFM4, olfactomedin 4; PMNs, polymorphonuclear leukocytes or neutrophils; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; SOFA, sepsis-related organ failure assessment score, which ranges from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating more severe organ dysfunction; WBC, white blood cell count. Statistical tests used: for continuous variables (with SD), t test; for dichotomous variables, chi-squared test.

Table 2.

Primary presenting diagnoses in 23 nonsepsis SIRS

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Bowel ischemia, infarction, or obstruction | n = 2, 8.7% |

| Fulminant hepatic failure | n = 2, 8.7% |

| Pancreatitis | n = 4, 17.4% |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Congestive heart failure | n = 2, 8.7% |

| Hypertensive crisis | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Hypotension | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Pulmonary edema | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Pulmonary hypertension | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Syncope | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Endocrine | |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Infectious disease | |

| Bacterial NOS (not septic) | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Oncology | |

| Solid tumor | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Respiratory | |

| COPD | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Deep venous thrombosis | n = 1, 4.4% |

| Hypercarbic or hypoxemic respiratory failure | n = 2, 8.7% |

| Neuromuscular weakness | n = 1, 4.4% |

SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NOS, not otherwise specified.

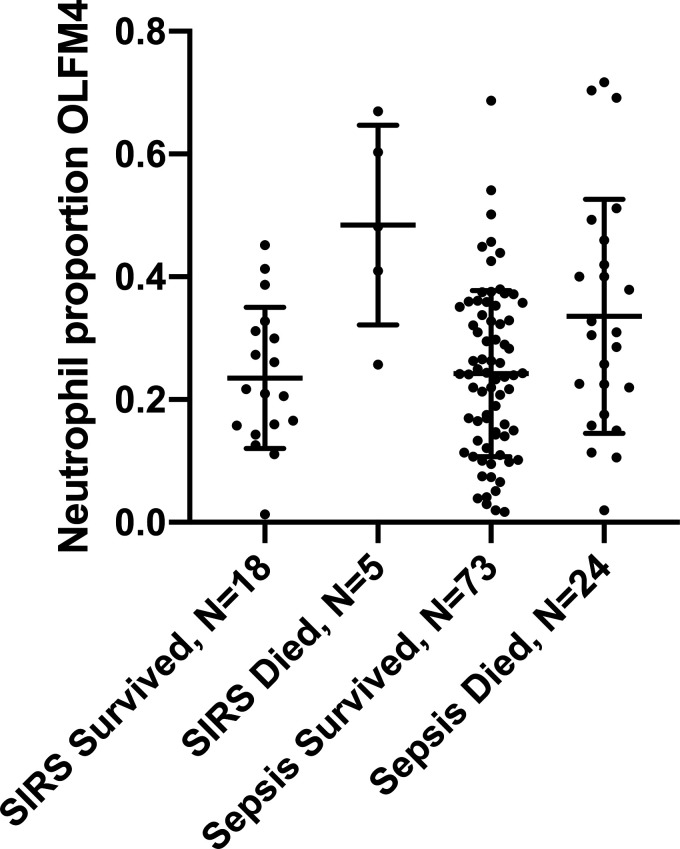

There was no difference in the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils between the nonsepsis SIRS and sepsis groups (28.9% ± 16.2% vs. 26.6% ± 15.5%, P = 0.51) (Table 1). However, among patients who died, the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was significantly increased compared with among those who survived (Fig. 3). In SIRS, the mean percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was 48.4% ± 16.3% among those who died compared with 23.5% ± 11.5% among those who survived, P = 0.001. In sepsis, the mean percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was 33.6% ± 19.1% among those who died compared with 24.2% ± 13.5% among those who survived, P = 0.01. Further analyses were limited to 97 patients with adjudicated sepsis, given our a priori hypothesis to study patients with sepsis and the limited power of 23 patients in the SIRS group.

Figure 3.

Mean percentage of olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4+) neutrophils according to outcome in adults with nonsepsis systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and those with sepsis. SIRS: mean OLFM4 was 23.5% ± 11.5% among those who survived compared with 48.4% ± 16.3% among those who died among 23 patients with SIRS (P = 0.001). Sepsis: mean OLFM4 was 24.2% ± 13.5% among those who survived compared with 33.6% ± 19.1% among those who died (P = 0.01; t test utilized for comparison between groups).

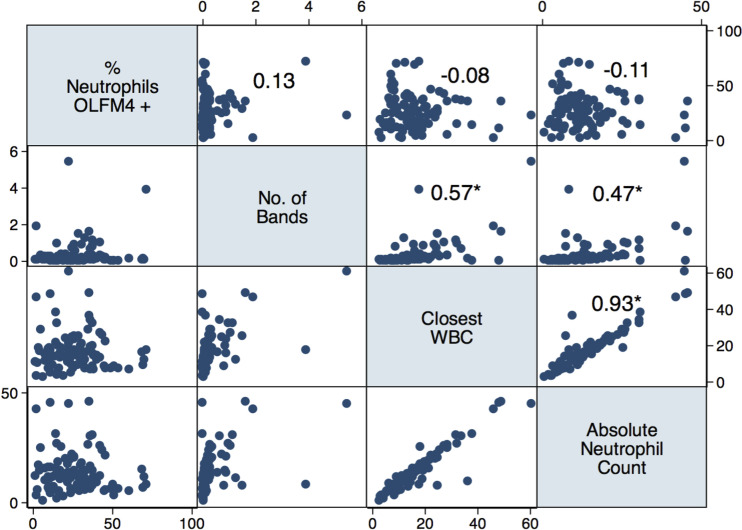

Among 97 patients with sepsis, there was no significant correlation between percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils and other clinical markers of neutrophil response, including concurrent WBC, ANC, or band count, P > 0.15 (Fig. 4). In contrast, concurrent WBC, ANC, and band count were all intercorrelated (P < 0.001). Similarly, several plasma biomarkers of inflammation and injury were intercorrelated (Fig. 5); however, none was correlated with the neutrophil percentage of OLFM4+, with the exception of plasma SP-D, where there was a weak positive correlation (Spearman’s ρ = 0.28, P < 0.006). In unadjusted analysis, each one-point increase in the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was associated with a 4% increased odds of death [odds ratio (OR) = 1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.01–1.07, P = 0.01].

Figure 4.

Graph matrix demonstrating the correlation coefficient between percentage of olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4+) neutrophils and clinical variables of neutrophil number and maturity [number of bands, closest/concurrent white blood cell count (WBC), and absolute neutrophil count (ANC)] among 97 patients with sepsis. No significant correlation was seen between percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils and other variables (P > 0.15); number of bands, WBC, and ANC are significantly intercorrelated. *P < 0.001 using Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Figure 5.

Dot plot comparing the correlation between percentage olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4+) neutrophils and plasma biomarkers of inflammation and injury among 97 patients with sepsis. Only surfactant protein D (SPD) is modestly positively correlated with OLFM4+ (Spearman’s ρ = 0.28, P = 0.006).

For further analyses, we dichotomized the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils using the Youden Index to identify an OLFM4 cut point of 37.6% (Fig. 6). Patients with a percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils ≥ 37.6% (“elevated OLFM4+,” n = 18, 19%) were significantly older (mean age = 74 ± 14 vs. 64 ± 16, P = 0.02), were more likely to have active solid or hematologic cancer (44% vs. 20%, P = 0.03), and had increased severity of illness compared with patients with nonelevated OLFM4+ (APACHE III 104 ± 39 vs. 78 ± 41, P = 0.02; SOFA 13.1 ± 3.7 vs. 10.5 ± 4.0) (Table 3). Among cases of active cancer, there were only two with leukemia, so we were underpowered to evaluate the association between elevated OLFM4+ and outcomes in this population. There was no association between elevated OLFM4+ neutrophils and positive culture results, bacteremia, or gram-positive or -negative microorganisms (Table 4).

Figure 6.

Youden Index among 97 patients with sepsis. Maximal area under the curve (AUC max) is at OLFM4 neutrophil expression of 37.6%.

Table 3.

characteristics, illness severity, and clinical outcomes in 97 septic adults according to OLFM4 ≥ 37.6% vs. < 37.6%*

|

Characteristic |

OLFM4 < 37.6%n = 79 (81%) | OLFM4 ≥ 37.6%n = 18 (19%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 64 ± 16 | 74 ± 14 | 0.02 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 43 (54) | 13 (72) | 0.17 |

| Race | 0.40 | ||

| Asian (3) | 25 (32%) | 8 (44%) | |

| Black (2) | 7 (9%) | 2 (11%) | |

| Latino (5) | 6 (8%) | 0 | |

| Pacific Islander (4) | 2 (3%) | 0 | |

| White (1) | 29 (37%) | 8 (44%) | |

| Other (6) | 10 (13%) | 0 | |

| Admitted to the ICU | 64 (81%) | 17 (94%) | 0.17 |

| Active cancer | 16 (20%) | 8 (44%) | 0.03 |

| Cirrhosis | 4 (5%) | 1 (6%) | 0.93 |

| ESRD | 9 (11%) | 0 | 0.13 |

| Illness severity | |||

| Micro positive | 53 (67%) | 11 (61%) | 0.63 |

| Positive Bacterial culture | 44 (56%) | 10 (56%) | 0.99 |

| Gram positive | 27 (61%) | 6 (60%) | 0.94 |

| Gram negative | 27 (61%) | 5 (50%) | 0.51 |

| Bacteremia | 20 (25%) | 6 (33%) | 0.48 |

| Pulmonary sepsis | 42 (55%) | 11 (61%) | 0.61 |

| SOFA score day 1 | 10.5 ± 4.0 | 13.1 ± 3.65 | 0.01 |

| APACHE III | 78 ± 41 | 104 ± 39 | 0.02 |

| WBC | 17.3 ± 11.1 | 13.2 ± 6.4 | 0.13 |

| ANC | 14.4 ± 9.7 | 11.1 ± 6.5 | 0.17 |

| Band count, Median (IQR) | 0.12 (0.06, 0.29) | 0.09 (0.05, 0.21) | 0.34 |

| Clinical Outcomes | |||

| Died at 60 days | 14 (18%) | 10 (56%) | 0.001 |

| Shock | 37 (47%) | 13 (72%) | 0.05 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 30 (38%) | 12 (67%) | 0.03 |

| ARDS* | 16/69 (23%) | 7/16 (44%) | 0.10 |

Values are means ± SD. ANC, absolute neutrophil count; APACHE III, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation severity of disease classification system, which ranges from 0 to 299, with higher scores indicating higher severity of illness; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; OLFM4, olfactomedin 4; SOFA, sepsis-related organ failure assessment score, which ranges from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating more severe organ dysfunction; WBC, white blood cell count. Micro positive, includes culture from any source tested [blood, urine, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), fluid, nasal swab, etc.] and any pathological microorganism including bacteria, virus, or fungus. Some patients had more than one source positive and had multiple positive cultures. Positive bacterial culture, includes culture from any source tested (blood, urine, CSF, fluid, etc.); gram positive and gram negative, percentages calculated from total number of positive bacterial cultures; pulmonary sepsis, out of a total of 95 due to 3 cases being excluded in this analysis for being “unknown”; *ARDS, defined according to the Berlin definition (20) and out of a total of 85 patients (patients with equivalent diagnosis for ARDS excluded). Statistical tests used: for continuous variables with SD, t test; for continuous variables with IQR (interquartile range) rank-sum test; for dichotomous variables, chi-squared test.

Table 4.

Pathologic microbiological findings in 97 adults presenting with sepsis*

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Bacteria | |

| Gram negative | |

| Aeromonas species | Blood n = 1 |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Blood n = 2 |

| Wound n = 1 | |

| Citrobacter freundii | Urine n = 2 |

| Escherichia coli | Blood n = 10 |

| Respiratory n = 1 | |

| Urine n = 17 | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Blood n = 1 |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae | Sputum n = 1 |

| Pancreatic pseudocyst n = 1 | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | Blood n = 1 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Blood n = 2 |

| Urine n = 4 | |

| Respiratory n = 1 | |

| Proteus mirabilis | Urine n = 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Respiratory n = 1 |

| Urine n = 2 | |

| Wound n = 1 | |

| Salmonella, Group B | Blood n = 1 |

| Serratia marcescens | Urine n = 1 |

| Other gram negative, not speciated | Blood n = 1 |

| Pancreatic pseudocyst n = 1 | |

| Pleural fluid n = 1 | |

| Peritoneal fluid n = 1 | |

| Respiratory n = 2 | |

| Urine n = 1 | |

| Wound n = 1 | |

| Gram positive | |

| Clostridium difficile | Stool n = 3 |

| Clostridium perfringens | Blood n = 1 |

| Clostridium species (nonperfringens) | Wound n = 1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Blood n = 1 |

| Urine n = 1 | |

| Enterococcus faecium | Urine n = 1 |

| Gemella morbillorum | Blood n = 1 |

| Pleural fluid n = 1 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Blood n = 3 |

| Respiratory n = 5 | |

| Urine n = 1 | |

| Wound n = 3 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Blood n = 2 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS) | Blood n = 1 |

| Urine n = 1 | |

| Respiratory n = 1 | |

| Wound n = 1 | |

| Streptococcus anginosis | Blood n = 2 |

| Pleural fluid n = 2 | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Blood n = 5 |

| Respiratory n = 4 | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Blood n = 1 |

| Wound n = 1 | |

| Streptococcus species, Group C | Wound n = 1 |

| Propionibacterium acnes | Pleural fluid n = 1 |

| Wound n = 1 | |

| Viridans streptococci | Other source n = 2 |

| Other gram positive, not speciated | Pancreatic pseudocyst n = 1 |

| Pleural fluid n = 1 | |

| Respiratory n = 1 | |

| Wound n = 1 | |

| Virus | |

| Influenza | Respiratory n = 7 |

| Metapneumonvirus | Respiratory n = 2 |

| Rhinovirus | Respiratory n = 5 |

| Fungus | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Serum Ag n = 2 |

Microorganisms not treated as infection by clinical team not included: Staphylococcus epidermidis, Enterococcus species, Candida in urine, Peptostreptococcus in blood, yeast.

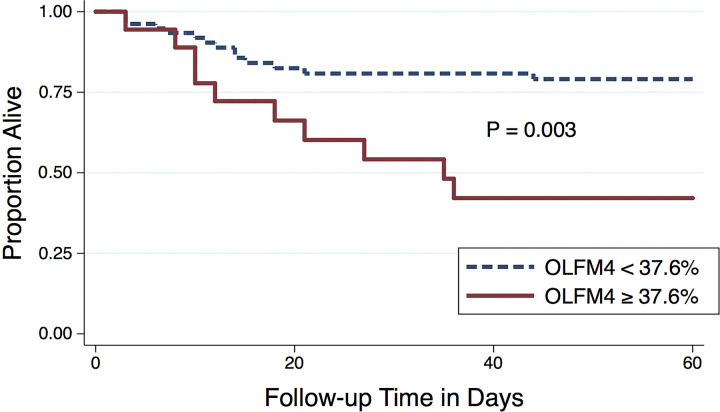

In terms of clinical outcomes, elevated OLFM4+ was associated with increased risk of death (56% vs. 18%, P < 0.001). In addition, elevated OLFM4+ was associated with shock (72% vs. 47%, P = 0.05) and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation (67% vs. 38% P = 0.03) in the first 5 days (Table 3). There was a trend toward an association between elevated OLFM4 and ARDS, though this did not meet statistical significance (P = 0.10). ARDS was more prevalent in the elevated OLFM4 group (44% vs. 23%). The probability of survival was significantly lower in patients with elevated OLFM4+, P = 0.003 (Fig. 7). The divergence in mortality curves began at ∼7–9 days after enrollment and persisted until around 30 days when the curves plateau.

Figure 7.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing the probability of survival in septic adults with neutrophil percentage of olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4) ≥ 37.6% compared with OLFM4 < 37.6% in 97 patients with sepsis using the log rank test.

In unadjusted analysis, elevated OLFM4+ was associated with nearly sixfold increased odds of death (OR = 5.80, 95% CI = 1.94–17.34, P = 0.002). Serial adjustment for age, sex, clinical neutrophil markers (closest WBC, ANC, band count), cancer, SOFA, and APACHE III did not attenuate the association between elevated OLFM4+ and death (Table 5). After combined adjustment for age, sex, WBC, and APACHE III, elevated OLFM4 was associated with a 4.8-fold increased odds of death compared with nonelevated OLFM4+ (OR = 4.82, 95% CI = 1.15–20.13, P = 0.03). The association between elevated OLFM4+ and death was also robust to adjustment for the presence of shock (OR = 4.83, 95% CI = 1.56–14.98, P = 0.006) and the need for mechanical ventilation within the first 5 days of admission (OR = 4.87, 95% CI = 1.58–14.98, P = 0.006) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Odds of death in 97 septic adults according to neutrophil expression of OLFM4 ≥ 37.6% compared with OLFM4 < 37.6% referent

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 5.80 (1.94–17.34) | 0.002 |

| Adjusted by age | 4.76 (1.55–14.60) | 0.006 |

| Adjusted by sex | 6.48 (2.08–20.17) | 0.004 |

| Adjusted by race | 7.47 (2.28–24.50) | 0.001 |

| Adjusted by closest WBC | 6.44 (2.08–19.93) | 0.001 |

| Adjusted by ANC | 6.20 (2.02–19.03) | 0.001 |

| Adjusted by band count | 6.91 (2.16–22.14) | 0.001 |

| Adjusted by active cancer | 4.96 (1.62–15.26) | 0.005 |

| Adjusted by SOFA score day 1 | 4.06 (1.22–13.53) | 0.02 |

| Adjusted by APACHE III | 4.06 (1.12–14.63) | 0.03 |

| Multivariate adjustment* | 4.82 (1.15–20.13) | 0.03 |

| Adjusted by shock in first 5 days | 4.83 (1.56–14.98) | 0.006 |

| Adjusted by need for mechanical ventilation first 5 days | 4.87 (1.58–14.98) | 0.006 |

Multivariate logistic regression of the association of OLFM4 ≥37.6% on mortality adjusted by age, sex, WBC, and APACHE III among 97 patients with sepsis. APACHE III ranges from 0 to 299, with higher scores indicating higher severity of illness. OLFM4, olfactomedin 4; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; SOFA, sepsis-related organ failure assessment score; APACHE III, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation severity of disease classification system.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of adults presenting to the emergency department with sepsis, the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was significantly increased in patients who ultimately died. The percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was not correlated with clinical measures of neutrophil numbers or immaturity and was not associated with plasma biomarkers of inflammation and injury. Elevated OLFM4+, defined as percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils ≥ 37.6% based on Youden distribution in this study, had a similar association with death, and its association with death withstood adjustment for demographics, comorbidities, severity of illness, and development of organ dysfunction within the first 5 days of enrollment. Elevated neutrophil OLFM4+ was also associated with shock and the need for mechanical ventilation in the first 5 days after enrollment.

Collectively, these data indicate that the neutrophil subset defined by the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils measures a biological response that is distinct from clinical measures of neutrophil numbers and maturity as well as several plasma measures of inflammation and injury in human sepsis. Taken together, these findings indicate that percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils may have the potential to provide independent prognostic information in the initial phases of illness. We did not observe a correlation between OLFM4 percentage and other biomarkers associated with sepsis prognosis. Future studies will need to evaluate the role of OLFM4 as a potential prognostic biomarker in patients presenting with sepsis and nonseptic critically ill patients.

Importantly, we also observed a statistically significant association between neutrophil percentage of OLFM4+ and death in patients with nonsepsis SIRS. This finding suggests that the mechanism leading to death in patients with an elevated neutrophil OLFM4+ percentage may occur independent of the host response to a microbial insult. The lack of association between OLFM4+ elevation and culture positive sepsis also supports a nonmicrobial mechanism in the association between OLFM4 elevation and death. Given the small sample size of nonsepsis SIRS in this study, additional studies will be needed to determine the prognostic utility of elevated OLFM4 in nonsepsis patients. This finding also augments the point that much is still to be learned about the mechanism of OLFM4 neutrophil percentage host response to infection and injury, including whether it primarily affects the host response to infection or other noninfectious acute illness states. Nevertheless, biomarkers can be useful and nonspecific to different underlying diseases (36). For example, IL-6 is an important prognostic marker in traumatic causes of acute and critical illness. In addition, TNF-α and RAGE are nonspecific but valuable inflammatory markers of organ injury (17, 18).

Importantly, it is not clear whether OLMF4 percentage is a response to severity of illness in sepsis or a preexisting risk factor for adverse immune responses in sepsis. First, the normal range of OLFM4+ neutrophils in healthy individuals is not known. For example, in two independent studies of healthy volunteers, Welin et al. (22) demonstrated a wide variance of OLFM4+ neutrophil subsets (8%–57%, mean = 34), whereas Clemmensen et al. (21) found less variance and a mean of <20%. Furthermore, changes in response to acute illness are further challenging to assess, as it is nearly impossible to follow patient from a healthy state to sepsis hospitalization, a relatively rare outcome at the population level. In a recent study, Stark et al. (37) reported dynamic changes in percentages of OLFM4+ neutrophils among children following bone marrow transplantation engraftment. Although this study demonstrates that the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils can change over time, it is not clear whether this translates to patients with sepsis, though Stark et al. (37) did identify decreased expression of CD64, a marker associated with response to infection, among OLFM4+ neutrophils. Finally, there are likely to be genetic differences in baseline OLFM4 expression among different populations sampled based on recent data of OLFM4 polymorphisms associated with outcomes in postsurgical septic shock, though percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was not measured in that study (27). In sum, we do not yet have enough data to establish normal baseline of OLFM4+ percentage in circulating neutrophils, and this is only the fourth manuscript to report percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils in humans.

Emergence of several recent studies provide biological plausibility of a role for OLFM4 in sepsis pathogenesis. Although the mechanism of OLMF4 in sepsis pathogenesis is not fully elucidated, OLFM4 has been identified in specific granules of 20%–30% of circulating neutrophils in humans, and functional studies have shown that OLFM4 inhibits the activation of several granular proteases critical to the innate immune response, including cathepsin C and G, neutrophil elastase, and proteinase 3 (21, 38). In murine studies, OLFM4−/− mice demonstrated enhanced in vivo bacterial clearance and decreased mortality in response to bacterial challenge. In sum, these findings suggest that expression of OLFM4 could be a marker of a pathogenic neutrophil subset or negatively impact the efficiency of bacterial killing for affected neutrophils (24, 25). In addition, recent clinical studies have found that increased OLFM4 gene expression and gene polymorphisms are associated with postsurgical sepsis shock mortality (26, 27, 39), and increased OLFM4 gene expression levels were associated with severe bronchiolitis among children with respiratory syncytial virus (40). In a transcriptional study of children with septic shock, OLFM4 was the most differentially expressed gene among those who died, similar to our prior findings of upregulated OLFM4 expression in adult patients developing sepsis-related ARDS (15, 23). In a smaller study of children with septic shock (n = 41), increased percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was associated with a more complicated sepsis course, defined as increased organ dysfunction and death (23). Our findings in adults expand on this finding with an increased prevalence of sepsis-associated mortality in a larger sample size.

The results of our study support the hypothesis that percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils measures a novel aspect of neutrophil-mediated host response that current clinical measures of neutrophil number and immaturity, plasma biomarkers of inflammation and organ injury, and general clinical risk factors for adverse outcomes do not encompass. The percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils may serve as an important pathogenic biomarker that could also be useful for identification of distinct treatment pathways in clinical trials (41). Further studies are needed to determine the mechanism of OLFM4+ neutrophils in the pathogenesis of organ dysfunction in sepsis.

This study has some limitations. First, this is a single-center study. Experimental studies involving flow cytometry require rapid analysis and use of the same flow cytometer for consistent readings. Although this process limited the study to a single site in this initial study, the current use of flow cytometry in clinical practice provides a precedent for the potential use of a flow-based clinical test in the future. Also, to our knowledge, this study is the largest to date of flow cytometric measurement of percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils. Future work to measure percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils in multiple independent centers would require clinically validated flow cytometric approaches for measurement. Second, determination of a cut point for elevated OLFM4 was performed based on the data within this cohort. Further work in larger cohorts will be required to determine clinically relevant cut points. Third, our initial screening criteria included meeting two of the four SIRS criteria. Given the advent of Sepsis-3 (31), our screening strategy may have missed patients with sepsis who met SOFA organ dysfunction criteria but not SIRS (42). However, a recent study from our institution has found that among patients with sepsis initially meeting sepsis criteria via SOFA, 84% develop at least two SIRS criteria within the subsequent several hours (43). Therefore, our screening strategy would have captured the large majority of patients presenting with sepsis. Fourth, we may not have been able to detect the entire association between the percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils and the development of acute organ dysfunction because this study measured the need for vasopressors and mechanical ventilation only through study day 5. The more robust association between elevated OLFM4+ and mortality and the timing of divergence of mortality curves beyond the first 5 days suggest that the association between elevated OLFM4+ and prolonged organ dysfunction may persist. Fifth, flow cytometry demonstrates that only cells that are CD66b positive are OLFM4 positive. This leaves open the possibility of eosinophils expressing OLFM4 as well. However, they typically account for <5% of the peripheral blood leukocytes, and expression would not change overall results significantly. Finally, our study was not powered to further assess the important hypothesis-generating finding of increased OLFM4 percentage in patients with nonsepsis SIRS who died. The a priori hypothesis for this study was to study patients with sepsis. Although it is interesting that a similar association between OLFM4 percentage and clinical outcomes was found in the nonsepsis group, we do not think that these samples can be combined because the clinical phenotypes are different for the patients with SIRS and the patients with sepsis. Although these preliminary findings suggest that OLFM4 percentage may not be specific to sepsis, other clinical studies to date have identified an association between OLFM4 and sepsis death, including among postsurgical patients (26, 39). Further work studying the association between OLFM4 and noninfectious organ dysfunction is warranted.

Conclusions

In summary, an increased percentage of OLFM4+ neutrophils was associated with death in adult patients presenting in the early phases of sepsis. This association was independent of demographic characteristics, clinical measures of neutrophil number and immaturity, plasma biomarkers of inflammation and injury, and initial severity of illness and comorbidities. The OLFM4+ neutrophil subset may help elucidate some of the heterogeneity in the host response to infection and may serve as a prognostic marker for patients presenting with sepsis and a potential point-of-care biomarker for characterization of sepsis subtypes.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R37 HL51856, R01 HL134828 (to M.A.M); 1K23 HL116800 (to K.N.K); R35 HL140026 (C.S.C); the National Institutes of Health Grants KO8AI119134 (to R.C.) and RO1 AI113272 (to C.L.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.N.K., R.C., K.D.L., M.N.A., H.R.W., C.S.C., C.L., and M.A.M. conceived and designed research; K.N.K., R.C., X.F., A.J., T.L., K.V., T.D., and M.A.M. performed experiments; K.N.K., R.C., X.F., T.D., P.S., H.Z., C.L., and M.A.M. analyzed data; K.N.K., R.C., X.F., P.S., A.L., K.D.L., M.N.A., C.S.C., C.L., and M.A.M. interpreted results of experiments; K.N.K. and X.F. prepared figures; K.N.K. drafted manuscript; K.N.K., R.C., A.L., K.D.L., M.N.A., H.R.W., C.S.C., C.L., and M.A.M. edited and revised manuscript; K.N.K., R.C., X.F., A.J., T.L., K.V., T.D., P.S., A.L., K.D.L., H.Z., M.N.A., H.R.W., C.S.C., C.L., and M.A.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients and families for consent and participation in this study, without whom this research would not have been possible. We thank Emily Siegel for assistance with manuscript editing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Epstein L, Dantes R, Magill S, Fiore A. Varying estimates of sepsis mortality using death certificates and administrative codes–United States, 1999-2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65: 342–345, 2016. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6513a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med 41: 1167–1174, 2013. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotts JE, Matthay MA. Sepsis: pathophysiology and clinical management. BMJ 353: i1585, 2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, Seymour CW, Liu VX, Deutschman CS, Angus DC, Rubenfeld GD, Singer M; Sepsis Definitions Task Force. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the third International Consensus Definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 315: 775–787, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antcliffe DB, Burnham KL, Al-Beidh F, Santhakumaran S, Brett SJ, Hinds CJ, Ashby D, Knight JC, Gordon AC. Transcriptomic signatures in sepsis and a differential response to steroids. From the VANISH randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 199: 980–986, 2019. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1419OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhavani SV, Carey KA, Gilbert ER, Afshar M, Verhoef PA, Churpek MM. Identifying novel sepsis subphenotypes using temperature trajectories. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200: 327–335, 2019. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201806-1197OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardlund B, Dmitrieva NO, Pieper CF, Finfer S, Marshall JC, Thompson BT. Six subphenotypes in septic shock: latent class analysis of the PROWESS Shock study. J Crit Care 47: 70–79, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seymour CW, Kennedy JN, Wang S, Chang CH, Elliott CF, Xu Z, Berry S, Clermont G, Cooper G, Gomez H, Huang DT, Kellum JA, Mi Q, Opal SM, Talisa V, van der Poll T, Visweswaran S, Vodovotz Y, Weiss JC, Yealy DM, Yende S, Angus DC. Derivation, validation, and potential treatment implications of novel clinical phenotypes for sepsis. JAMA 321: 2003–2017, 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinha P, Delucchi KL, Thompson BT, McAuley DF, Matthay MA, Calfee CS, Network NA; NHLBI ARDS Network. Latent class analysis of ARDS subphenotypes: a secondary analysis of the statins for acutely injured lungs from sepsis (SAILS) study. Intensive Care Med 44: 1859–1869, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5378-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotts JE, Bernard O, Chun L, Croze RH, Ross JT, Nesseler N, Wu X, Abbott J, Fang X, Calfee CS, Matthay MA. Clinically relevant model of pneumococcal pneumonia, ARDS, and nonpulmonary organ dysfunction in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 317: L717–L736, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00132.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Annane D, Bellissant E, Cavaillon JM. Septic shock. Lancet 365: 63–78, 2005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17667-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hotchkiss RS, Opal S. Immunotherapy for sepsis–a new approach against an ancient foe. N Engl J Med 363: 87–89, 2010. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1004371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delano MJ, Scumpia PO, Weinstein JS, Coco D, Nagaraj S, Kelly-Scumpia KM, O'Malley KA, Wynn JL, Antonenko S, Al-Quran SZ, Swan R, Chung CS, Atkinson MA, Ramphal R, Gabrilovich DI, Reeves WH, Ayala A, Phillips J, Laface D, Heyworth PG, Clare-Salzler M, Moldawer LL. MyD88-dependent expansion of an immature GR-1(+)CD11b(+) population induces T cell suppression and Th2 polarization in sepsis. J Exp Med 204: 1463–1474, 2007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerin E, Orabona M, Raquil MA, Giraudeau B, Bellier R, Gibot S, Bene MC, Lacombe F, Droin N, Solary E, Vignon P, Feuillard J, Francois B. Circulating immature granulocytes with T-cell killing functions predict sepsis deterioration*. Crit Care Med 42: 2018–2014, 2007. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kangelaris KN, Prakash A, Liu KD, Aouizerat B, Woodruff PG, Erle DJ, Rogers A, Seeley EJ, Chu J, Liu T, Osterberg-Deiss T, Zhuo H, Matthay MA, Calfee CS. Increased expression of neutrophil-related genes in patients with early sepsis-induced ARDS. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308: L1102–L1113, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00380.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kangelaris KN, Seeley EJ. From storm to suppression in sepsis: are bands the link?*. Crit Care Med 42: 2135–2136, 2014. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stensballe J, Christiansen M, Tonnesen E, Espersen K, Lippert FK, Rasmussen LS. The early IL-6 and IL-10 response in trauma is correlated with injury severity and mortality. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 53: 515–521, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uchida T, Shirasawa M, Ware LB, Kojima K, Hata Y, Makita K, Mednick G, Matthay ZA, Matthay MA. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products is a marker of type I cell injury in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173: 1008–1015, 2006. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1477OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warszawska JM, Gawish R, Sharif O, Sigel S, Doninger B, Lakovits K, Mesteri I, Nairz M, Boon L, Spiel A, Fuhrmann V, Strobl B, Muller M, Schenk P, Weiss G, Knapp S. Lipocalin 2 deactivates macrophages and worsens pneumococcal pneumonia outcomes. J Clin Invest 123: 3363–3372, 2013. doi: 10.1172/JCI67911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS; ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 307: 2526–2533, 2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clemmensen SN, Bohr CT, Rorvig S, Glenthoj A, Mora-Jensen H, Cramer EP, Jacobsen LC, Larsen MT, Cowland JB, Tanassi JT, Heegaard NH, Wren JD, Silahtaroglu AN, Borregaard N. Olfactomedin 4 defines a subset of human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol 91: 495–500, 2012. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0811417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welin A, Amirbeagi F, Christenson K, Bjorkman L, Bjornsdottir H, Forsman H, Dahlgren C, Karlsson A, Bylund J. The human neutrophil subsets defined by the presence or absence of OLFM4 both transmigrate into tissue in vivo and give rise to distinct NETs in vitro. PLoS One 8: e69575, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alder MN, Opoka AM, Lahni P, Hildeman DA, Wong HR. Olfactomedin-4 is a candidate marker for a pathogenic neutrophil subset in septic shock. Crit Care Med 45: e426–e432, 2017. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alder MN, Mallela J, Opoka AM, Lahni P, Hildeman DA, Wong HR. Olfactomedin 4 marks a subset of neutrophils in mice. Innate Immun 25: 22–33, 2019. doi: 10.1177/1753425918817611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, Yan M, Liu Y, McLeish KR, Coleman WG , Jr, Rodgers GP. Olfactomedin 4 inhibits cathepsin C-mediated protease activities, thereby modulating neutrophil killing of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in mice. J Immunol 189: 2460–2467, 2012. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almansa R, Ortega A, Avila-Alonso A, Heredia-Rodriguez M, Martin S, Benavides D, Martin-Fernandez M, Rico L, Aldecoa C, Rico J, Lopez de Cenarruzabeitia I, Beltran de Heredia J, Gomez-Sanchez E, Aragon M, Andres C, Calvo D, Andaluz-Ojeda D, Liu P, Blanco-Antona F, Blanco L, Gomez-Herreras JI, Tamayo E, Bermejo-Martin JF. Quantification of immune dysregulation by next-generation polymerase chain reaction to improve sepsis diagnosis in surgical patients. Ann Surg 269: 545–553, 2019. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez-Garcia F, Resino S, Gomez-Sanchez E, Gonzalo-Benito H, Fernandez-Rodriguez A, Lorenzo-Lopez M, Heredia-Rodriguez M, Gomez-Pesquera E, Tamayo E, Jimenez-Sousa MA; Group of Biomedical Research in Critical Care Medicine (BioCritic). OLFM4 polymorphisms predict septic shock survival after major surgery. Eur J Clin Invest e13416, 2020. [32996122] doi: 10.1111/eci.13416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agrawal A, Matthay MA, Kangelaris KN, Stein J, Chu JC, Imp BM, Cortez A, Abbott J, Liu KD, Calfee CS. Plasma angiopoietin-2 predicts the onset of acute lung injury in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 736–742, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1460OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang M, Hsu R, Hsu CY, Kordesch K, Nicasio E, Cortez A, McAlpine I, Brady S, Zhuo H, Kangelaris KN, Stein J, Calfee CS, Liu KD. FGF-23 and PTH levels in patients with acute kidney injury: a cross-sectional case series study. Ann Intensive Care 1: 21, 2011. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 101: 1644–1655, 1992. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315: 801–810, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 22: 707–710, 1996. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, Osborn TM, Nunnally ME, Townsend SR, Reinhart K, Kleinpell RM, Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Machado FR, Rubenfeld GD, Webb SA, Beale RJ, Vincent JL, Moreno R; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 41: 580–637, 2013. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perkins NJ, Schisterman EF. The Youden Index and the optimal cut-point corrected for measurement error. Biom J 47: 428–441, 2005. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 3: 32–35, 1950. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spindler-Vesel A, Wraber B, Vovk I, Kompan L. Intestinal permeability and cytokine inflammatory response in multiply injured patients. J Interferon Cytokine Res 26: 771–776, 2006. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stark JE, Opoka AM, Fei L, Zang H, Davies SM, Wong HR, Alder MN. Longitudinal characterization of olfactomedin-4 expressing neutrophils in pediatric patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. PLoS One 15: e0233738, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen L, Li H, Liu W, Zhu J, Zhao X, Wright E, Cao L, Ding I, Rodgers GP. Olfactomedin 4 suppresses prostate cancer cell growth and metastasis via negative interaction with cathepsin D and SDF-1. Carcinogenesis 32: 986–994, 2011. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez-Paz P, Aragon-Camino M, Gomez-Sanchez E, Lorenzo-Lopez M, Gomez-Pesquera E, Lopez-Herrero R, Sanchez-Quiros B, de la Varga O, Tamayo-Velasco A, Ortega-Loubon C, Garcia-Moran E, Gonzalo-Benito H, Heredia-Rodriguez M, Tamayo E. Gene expression patterns distinguish mortality risk in patients with postsurgical shock. J Clin Med 9: 1276, 2020. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brand HK, Ahout IM, de Ridder D, van Diepen A, Li Y, Zaalberg M, Andeweg A, Roeleveld N, de Groot R, Warris A, Hermans PW, Ferwerda G, Staal FJ. Olfactomedin 4 serves as a marker for disease deverity in pediatric respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. PLoS One 10: e0131927, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthay MA, Zemans RL, Zimmerman GA, Arabi YM, Beitler JR, Mercat A, Herridge M, Randolph AG, Calfee CS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 5: 18, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 373: 881, 2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1506819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prasad PA, Fang MC, Abe-Jones Y, Calfee CS, Matthay MA, Kangelaris KN. Time to recognition of sepsis in the emergency department using electronic health record data: a comparative analysis of SIRS, SOFA and qSOFA. Crit Care Med 48: 200–209, 2020. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]