Abstract

Metastatic melanoma can be difficult to detect until at the advanced state that decreases the survival rate of patients. Several FDA-approved BRAF inhibitors have been used for treatment of metastatic melanoma, but overall therapeutic efficacy has been limited. Lutetium-177 (177Lu) enables simultaneous tracking of tracer accumulation with single-photon emission computed tomography and radiotherapy. Therefore, the co-delivery of 177Lu alongside chemotherapeutic agents using nanoparticles (NPs) might improve the therapeutic outcome in metastatic melanoma. Cellulose nanocrystals (CNC NPs) can particularly deliver payloads to lung capillaries in vivo. Herein, we developed 177Lu-labeled CNC NPs loaded with vemurafenib ([177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs) and investigated the synergistic chemo/radiotherapeutic effects in BRAF V600E mutation-harboring YUMM1.G1 murine model of lung metastatic melanoma. The [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs demonstrated favorable radiolabel stability, drug release profile, cellular uptake, and cell growth inhibition in vitro. In vivo biodistribution revealed significant retention of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs in the lung, liver, and spleen. Ultimately, the median survival time of animals was doubly increased after treating with [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs compared to control groups. The enhanced therapeutic efficacy of [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs in the lung metastatic melanoma animal model provides convincing evidence for the potential clinical translation of theranostic CNC NP-based drug delivery systems after intravenous administration.

Keywords: cellulose nanocrystal, vemurafenib, Lutetium-177, theranostic nanosystem, drug delivery system, metastatic melanoma

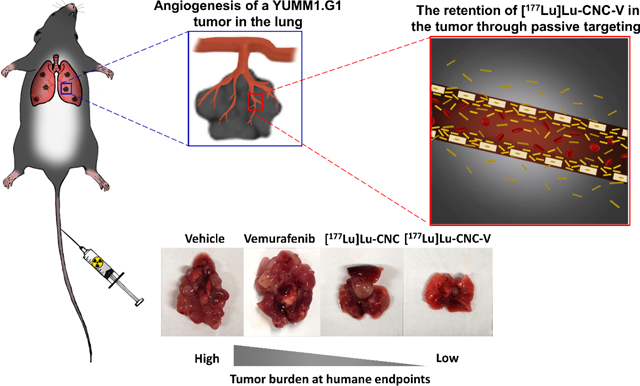

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Metastatic melanoma is the most aggressive form of skin cancer, and patients with the disease continue to have a poor prognosis after treatment.[1–3] Metastatic melanoma develops through the dissemination of melanoma cells from the primary tumor site to different parts of the body (e.g. lung, liver, spleen, and kidney) via the circulatory and lymphatic systems.[4,5] In clinical practice, there are several options for the treatment of metastatic melanoma, including immunotherapy, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy[3]. In melanoma, the serine/threonine protein kinase BRAF plays a critical role in growth signaling transduction in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway.[6–8] Over 90% of tumorigenic BRAF mutations appear at codon 600 (V600E), where an α-amino acid (valine; V) position in the protein kinase domain is substituted by glutamic acid (E).[9,10] Kinase activity in melanomas harboring the BRAF V600E mutation is elevated 500-to 700-fold compared to wild-type BRAF, leading to cell transformation and tumor formation.[11] In addition, the BRAF V600E mutation is found in 40–60% of melanoma patients, rendering it a promising candidate for targeted therapy.[12] PLX4032 (vemurafenib) is a clinically approved tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits ATP binding in BRAF V600E-mutated melanomas, resulting in the deactivation of the MAPK pathway and reduction in cell proliferation and survival.[13,14] Vemurafenib is currently in the frontline for the treatment of metastatic and non-resectable BRAF V600E-expressing melanomas. However, the therapeutic efficacy of vemurafenib remains suboptimal due to the need for high doses, the poor bioavailability of the drug, adaptive drug resistance behavior, and the reactivation of the MAPK pathway from drug-induced stress responses after repeated cycles of treatment.[14–17]

Radiolabeled tracers have been applied in oncology for diagnosis, staging, therapy, and long-term monitoring of numerous cancers.[18] Lutetium-177 (177Lu) is a theranostic radionuclide that is frequently used in the clinic due to physical and nuclear properties — a relatively long half-life (t1/2 = 6.6 d) and the emission of both gamma (γ) and beta (β−) radiation — that enable simultaneous imaging and radiotherapy. The emission of gamma radiation (Eγ = 208 keV, 10% intensity) facilitates non-invasive diagnostic imaging using single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). The β− radiation (Eβmax = 0.498 MeV, 79% intensity) enables endoradiotherapy through the deposition of ionizing particles that induce cytotoxic ROS formation and DNA double-strand breaks within the cells.[19,20]

Nanostructured materials have been employed in the field of nanomedicine as drug delivery systems (DDS) intended to address the limitations in conventional formulations.[21,22] Nanoparticles (NPs) are a versatile platform that can be tailored to have the desired characteristics and properties for specific drug delivery applications. Engineered NPs offer several advantages, including improved drug solubility, controlled drug release, increased drug circulation half-life, and enhanced targetability.[23–25] Cellulose is an abundant biomacromolecular material obtained from various renewable resources.[26,27] In drug delivery applications, nanocrystalline cellulose nanoparticles (CNC NPs) have received great interest as a biopolymer-based nanomaterial that can be easily and economically prepared from the separation of the crystalline regions of native cellulose through strong acid hydrolysis.[28,29] The CNC NPs possess versatile physical and chemical properties, including a needle-like structure with dimensions of 5–10 nm in width and 100–300 nm in length (for CNC NPs derived from wood and cotton), a high aspect ratio (length/width), and surface chemistry that is amenable to conjugation via the manipulation of hydroxyl (OH), aldehyde (CHO), and sulfate (OSO3) groups.[29,30] Furthermore, the biocompatibility, biodegradability, and lack of toxicity of CNC NPs has led many to advocate their use in biomedical tools.[31–35] According to our previous reports[31,35], radiolabeled CNC nanoprobes display a transient uptake and retention in the lung tissue, suggesting that CNC NPs could be used to target the lung vascular bed and pulmonary metastasis through the enhanced permeability and retention effect.[36] Since CNC NPs tend to accumulate in the lung capillaries, the delivery of vemurafenib with CNC NPs to metastatic melanoma in the lung is an attractive model to explore the drug delivery potential of the CNC NPs to lung tissue. Furthermore, the diagnostic radioisotope 111In used previously can be readily swapped for 177Lu to explore the potential synergistic effects of 177Lu-radiotherapy and vemurafenib chemotherapy.

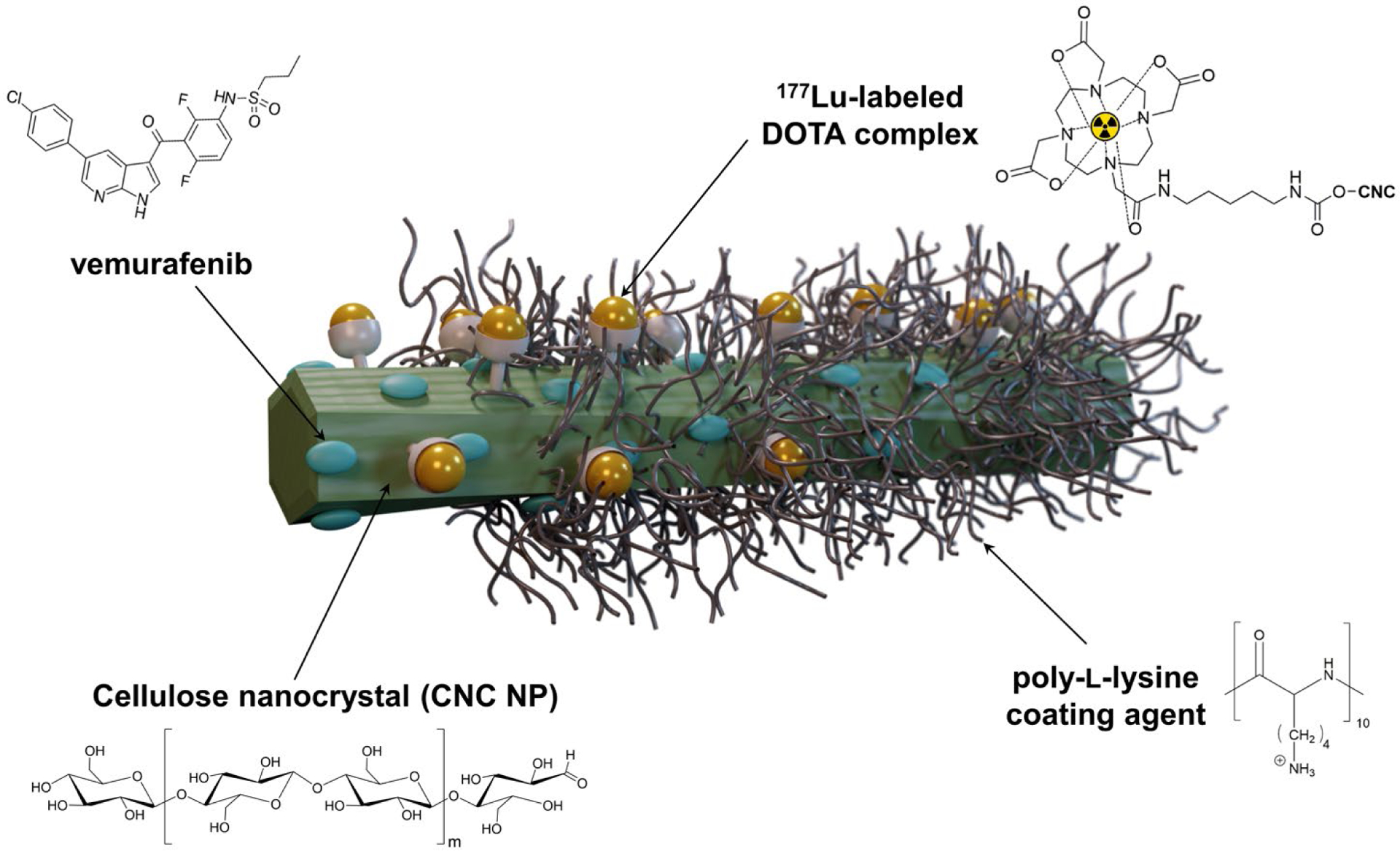

In this study, we developed theranostic 177Lu-labeled CNC NPs loaded with vemurafenib ([177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs, Figure 1) and investigated their biological behavior in both murine and human melanoma cell models and animals bearing metastatic melanoma allografts in the lung. The theranostic CNC NPs were prepared through the conjugation of 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) to the hydroxyl groups on the surface of the CNC NPs followed by radiolabeling with 177Lu. Then, vemurafenib was incorporated onto the surface of the 177Lu-labeled CNC NPs via the electrostatic interactions using a cationic polymer (poly-L-lysine) as a capping agent. The in vitro radiolabeling stability and drug release profiles of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs were studied in different physiological simulated conditions. Furthermore, the cell cytotoxicity, cellular uptake, and clonogenic cell survival were evaluated in both murine and human melanoma cell models. Finally, the ex vivo biodistribution and therapeutic studies of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs were assessed in mice bearing YUMM1.G1 lung metastatic melanoma allografts for the preclinical evaluation of the theranostic CNC NP-based DDS and its potential of future clinical translation.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the 177Lu-labeled CNC NPs loaded with vemurafenib ([177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs). The green rod represents a cotton cellulose nanocrystal (CNC NP). The bifunctional radiometal chelator DOTA-NH2 is conjugated on the CNC surface via CDI-activated OH groups and further radiolabeled with 177Lu. Vemurafenib is entrapped on the surface of CNC by electrostatic interaction with the aid of poly-L-lysine as a capping agent.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Materials’ characterization

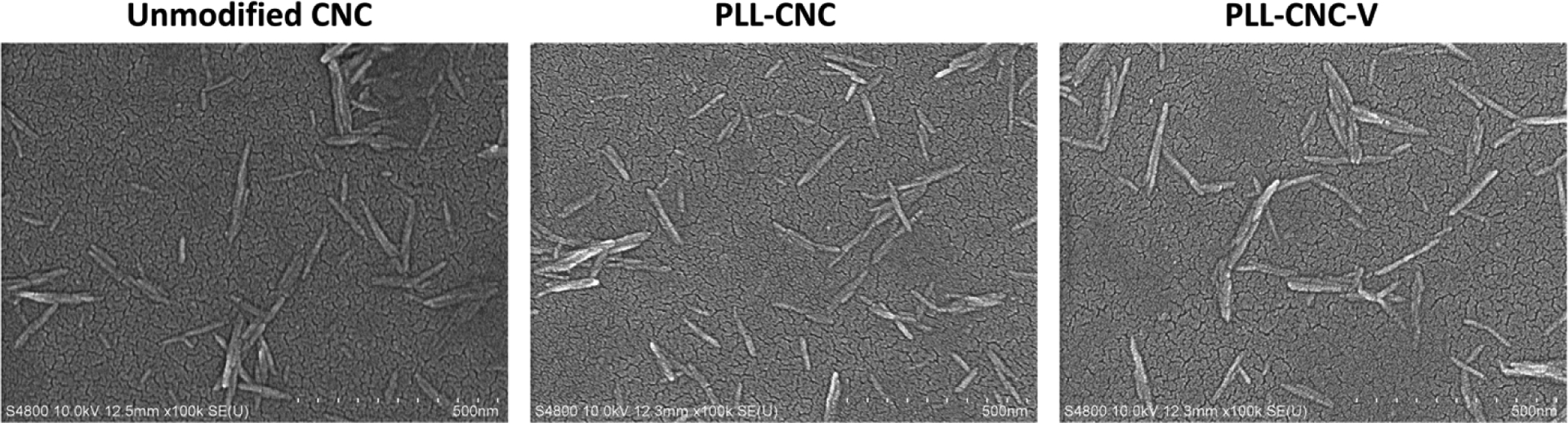

The DOTA-modified CNC NPs were successfully prepared through the CDI-mediated amidation reaction between the activated hydroxyl groups and DOTA-NH2. When compared to unmodified CNC spectrum, the ATR-FTIR spectrum of the DOTA-CNC NPs contained the conjugation product peaks, including the amide II band (C–N stretching and N–H bending) at 1510–1700 cm−1, and alkyl band (C–H stretching) at 2850–2950 cm−1, demonstrating successful conjugation of DOTA chelator to the surface of the CNC NPs (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Moreover, the changes in the C, H, and N compositions of modified CNC NPs corroborated the successful conjugation reaction. While there was no significant difference in the C and H content from that of unmodified CNC NPs, the amount of N increased substantially to approximately 0.9% in the DOTA-CNC NPs, presumably due to the presence of the N in the DOTA macrocyclic ring (Table S1, Supporting Information). The N content was further used to estimate the degree of substitution (DS), providing the average number of DOTA molecules attached per monomeric unit of the CNC NPs (Supporting Information). The DS of DOTA molecules to the CNC NPs was approximately 0.24, which is in agreement with the values reported in the literature where the DS of grafting molecules on the cellulose surface through heterogeneous reactions is generally less than 1.0 as a result of an unreactive hydroxyl group at the carbon position C2 and C3 of the anhydroglucose unit.[37] The DOTA-CNC NPs showed an increase in zeta (ζ)-potential value (−30.67±0.91 mV) compared to the native CNC NPs (−52.53±2.67 mV). However, the negative surface charge of the DOTA-modified CNC NPs is sufficiently low to avoid non-specific adsorption of plasma proteins.[38] Upon capping with PLL, the ζ-potential reversed to positive (47.23 ± 1.26 mV) and was lowered to close to 0 mV (1.72 ± 0.27 mV) in the full 177Lu-radiolabeled [177Lu]Lu-CNC-PLL-V nanotheranostic construct. Compared to neutral or negatively charged nanoparticles, positively charged nanoparticles have a stronger interaction with the negatively charged cell membrane driven by electrostatic attraction. The slightly positive charge of [177Lu]Lu-CNC-PLL-V NPs might favor the cell adhesion both in vitro and in vivo, leading to higher accumulation within cells.[39] The ζ-potential results of all non-radiolabeled and radiolabeled CNC NPs in this work are compiled in Table S2, Supporting Information. In addition, FE-SEM images were acquired to determine the morphology of the CNC NPs after the chemical modifications. There is no dramatic change in the morphology of the modified CNC NPs compared to unmodified CNC NPs, and all the CNC NPs demonstrated a rod-like shape with an average width of 9–14 nm and length of 136–158 nm as well as a uniform particle size distribution (Figure 2 and Figure S2, Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

FE-SEM images of unmodified CNC NPs, PLL-coated CNC (PLL-CNC) NPs, and vemurafenib-loaded CNC (PLL-CNC-V) NPs, scale bar = 500 nm.

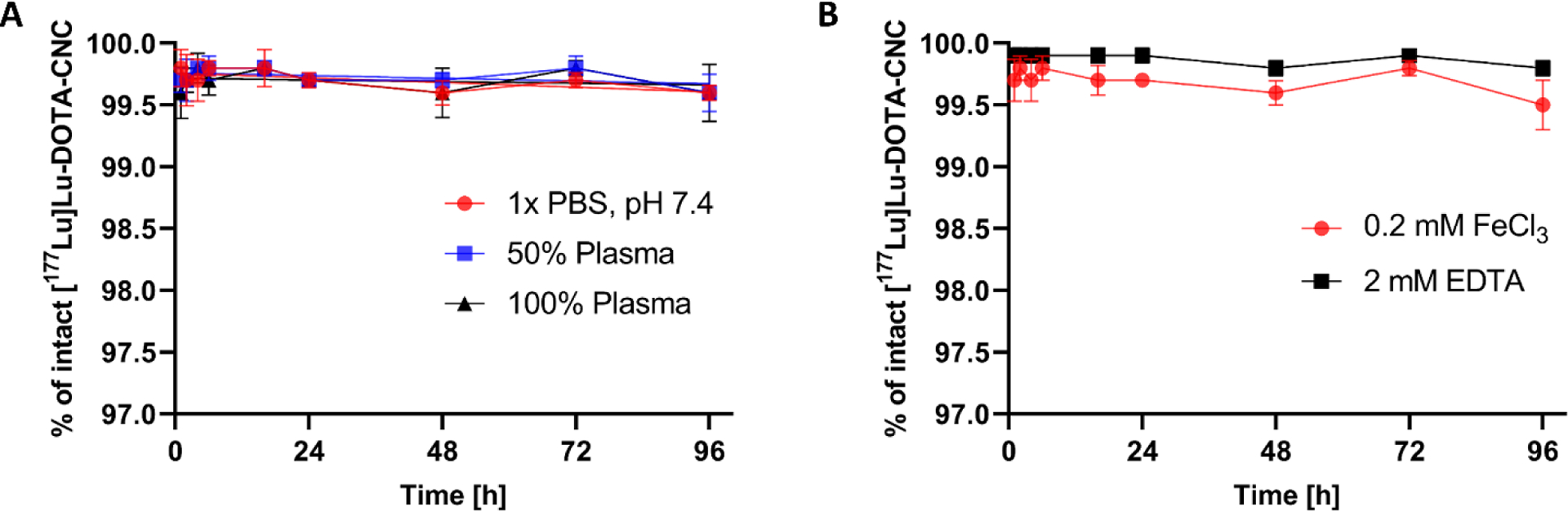

2.2. 177Lu-radiolabeled CNC NPs and in vitro stability

The DOTA-CNC NPs were successfully labeled with 177Lu using standard radiolabeling procedures with a decay-corrected radiochemical yield (RCY = 74 ± 2%, n = 4) and a radiochemical purity (RCP > 99.5%) after purification. The in vitro stability of 177Lu-radiolabeled CNC construct was thoroughly studied in various simulated physiological conditions, including 1×PBS (pH 7.4), and 50% and 100% human plasma. The stability of the radiometal-ligand complex was also investigated using 0.2 mM FeCl3 and 2 mM EDTA as a competing metal and ligand, respectively.

In general, the [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs demonstrated good radiolabel stability with > 99.5% of the 177Lu radiolabel remaining bound to the surface of the CNC NPs after 96 h of incubation in 1×PBS (pH 7.4), and in 50% and 100% human plasma in 1×PBS (pH 7.4) at 37 °C (Figure 3A). The results suggest that plasma proteins have no significant effect on the radiolabel complex stability or nanomaterial degradation, indicating suitability for in vivo use. Moreover, the [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs revealed remarkable complex stability (≥ 99.5% intact) over 96 h of incubation in 0.2 mM FeCl3 solution where the Fe3+ concentration was considerably higher than the normal range (10–30 μM) in human tissues.[40] Similarly, the percentage of intact [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-CNC NPs in 2 mM EDTA solution was maintained at 99.8% over the incubation period, which indicates stable coordination of the 177Lu3+ in the DOTA chelator (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The in vitro stability of 177Lu-radiolabeled CNC NPs in (A) 1×PBS (pH 7.4), and in 50% and 100% human plasma in 1×PBS (pH 7.4), and (B) 0.2 mM FeCl3 and 2 mM EDTA challenges. The values represent mean ± s.d. (n=3).

2.3. Drug-loaded CNC NPs and in vitro drug release profiles

Vemurafenib was successfully loaded to both non-radiolabeled and radiolabeled CNC NPs through non-covalent binding on the surface of the CNC in the presence of cationic PLL as a capping agent, promoting the electrostatic binding of the hydrophobic drug. The non-radiolabeled PLL-CNC-V NPs showed a moderate drug loading efficiency of 13.13 ± 1.00%, while the loading efficiency on the radiolabeled [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs (29.50 ± 3.50%) was improved about 2-fold (Table S3, Supporting Information). This might be the result of a higher positive surface charge of [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs compared to non-radiolabeled CNC NPs (Table S2, Supporting Information). The additional negative charge from the deprotonated carboxylic acid residues on the DOTA chelator of [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs could promotes the capping with PLL, which may drive a greater amount of vemurafenib to entrap on the surface of the CNC in radiolabeled particles. Moreover, the obtained drug loading efficiency and loading degree of non-radiolabeled CNC NPs in this work were slightly lower than those reported for the CNC NP-based DDS in the literature, in which the average loading efficiency and loading degree for hydrophobic compounds have ranged between 21–25% and 14–20%, respectively.[41–43]

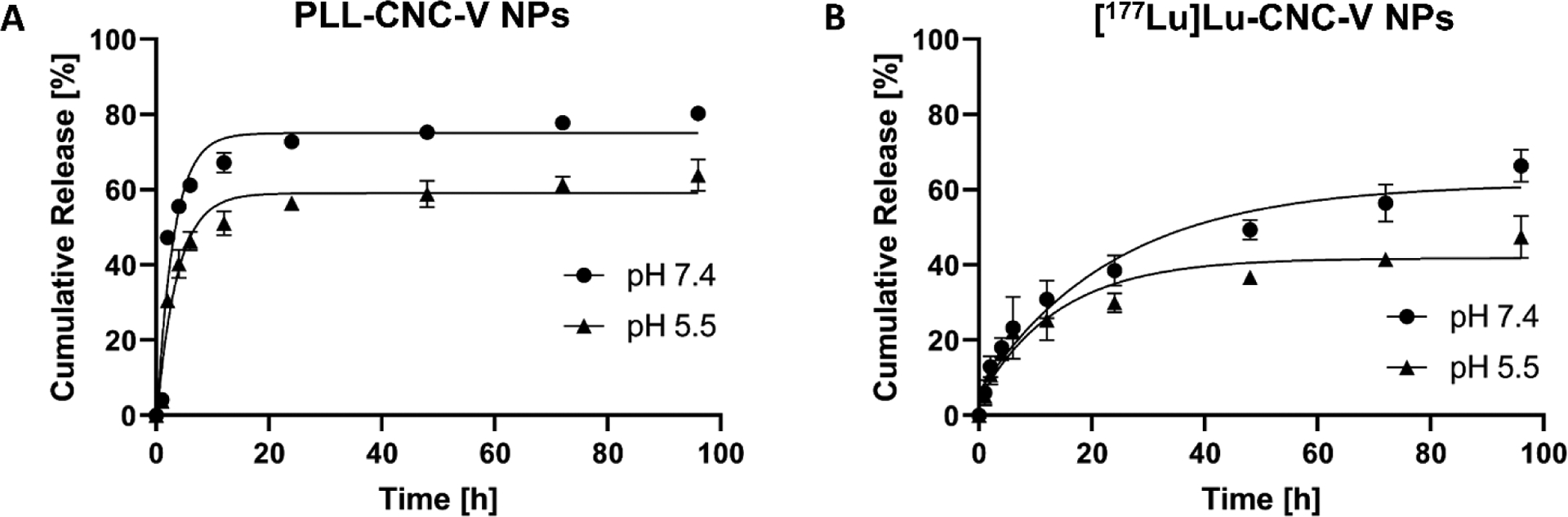

The ability of the developed CNC NPs DDS to release the vemurafenib payload was first evaluated in physiological fluids in vitro, including 1×PBS (pH 7.4) and 10 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.5) for blood and tumor microenvironment mimicking conditions, respectively. Overall, both PLL-CNC-V NPs and the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs exhibited a rapid release pattern of vemurafenib after 2 h of incubation in both simulated media before the release kinetics were sustained over the incubation period (Figure 4). Interestingly, both NP constructs demonstrated superior drug release rate in 1×PBS (pH 7.4) in which the cumulative release reached 80% and 66% while only 64% and 47% were attained at pH 5.5 after 96 h of incubation for PLL-CNC-V NPs and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs, respectively. This phenomenon could be explained by the fact that the PLL coated on the surface of CNC is bound by electrostatic interactions. A strong electrolyte of 137 mM NaCl in PBS buffer might screen some electrostatic interactions and weaken the binding of PLL, resulting in loss of the capping capacity. Furthermore, the 10% (v/v) human serum added to the incubation media in order to induce a sink condition could promote the scavenging of the PLL coating due to electrostatic interactions with the serum proteins.

Figure 4.

In vitro drug release profiles of vemurafenib-loaded non-radiolabeled PLL-CNC-V NPs (A) and vemurafenib-loaded radiolabeled [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs (B) in simulated physiological 1×PBS (pH 7.4) and condition mimicking the tumor microenvironment (pH 5.5, representing the late endosome) over 96 h. The values represent mean ± s.d. (n=3).

In contrast, the release profiles of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs in both conditions were decelerated compared to the non-radioactive PLL-CNC-V NPs. This might be the influence from the carboxylic residues on the non-radiolabeled DOTA chelator left on the surface of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs after radiolabeling. The negative charge from the carboxylic groups might foster an interaction with vemurafenib while PLL starts to lose its capping capacity, leading to a slower drug release pattern. Therefore, the drug loading strategy and coating materials for surface stabilization could be further optimized to enhance the capping capacity and minimize the release at physiological pH 7.4 while triggering a burst release at the acidic pH of the tumor microenvironment. Regardless of the room for improvement, the results demonstrate that both non-radiolabeled and radiolabeled CNC NPs are promising nanocarriers for the delivery of vemurafenib with satisfactory release behavior for in vivo use.

2.4. In vitro cytocompatibility

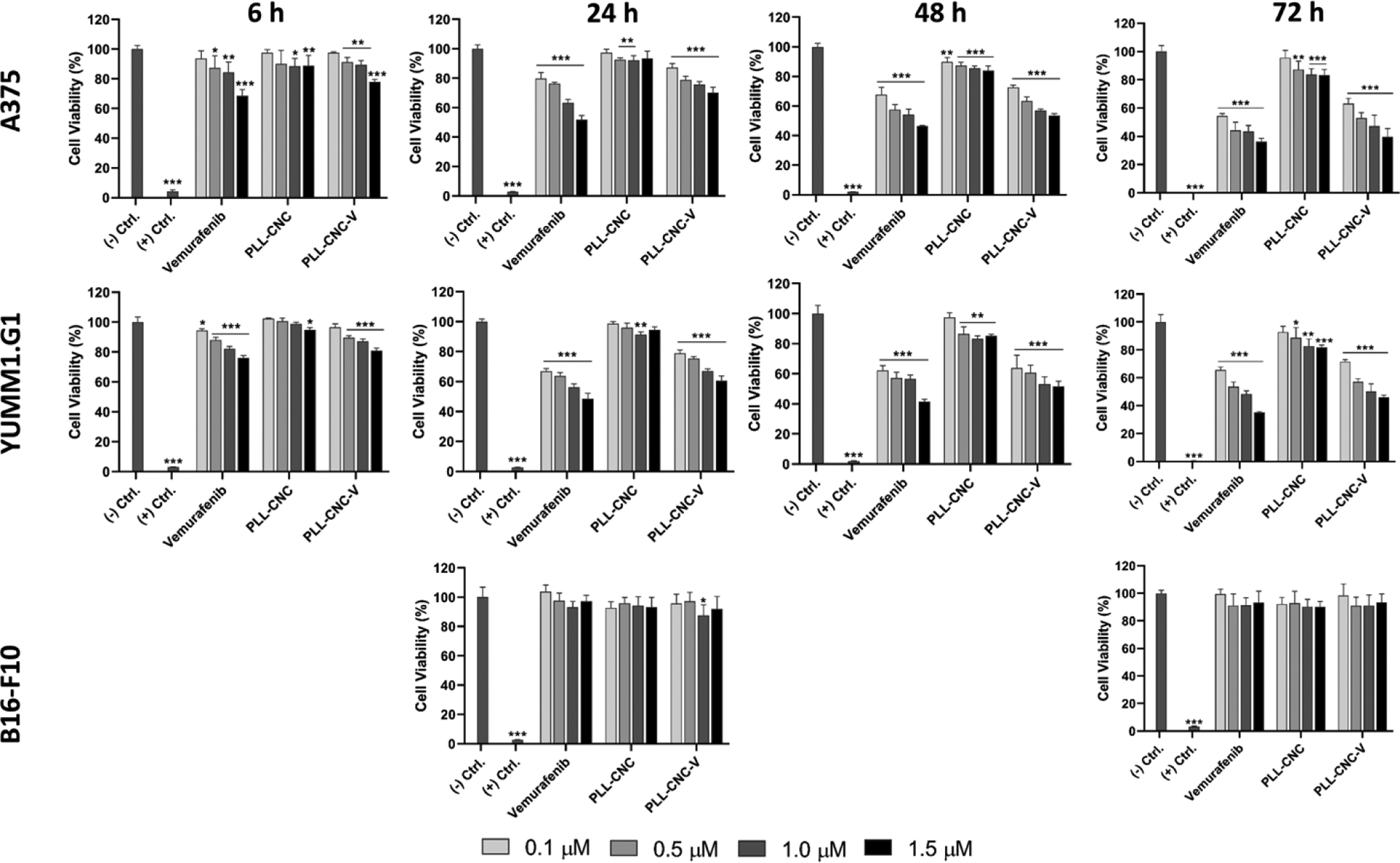

Despite the promising radiolabeling yield, radiolabel stability and drug release pattern of the CNC NPs, the cytotoxicity of the newly developed vemurafenib-loaded CNC NPs is an important issue that needs to be investigated before in vivo applications. The in vitro cytotoxicity screening test could provide preliminary information on the potential toxicity and subcellular targeting of drug-loaded nanoparticles that could suggest a prediction of in vivo effects. The in vitro cytotoxicity of the PLL-CNC-V NPs was studied in both BRAF V600E mutant cell lines (murine YUMM1.G1 and human A375) and wild-type BRAF cell line (murine B16-F10) at various concentrations and incubation times. In general, the YUMM1.G1 and A375 cell lines exhibited a linear decrease in cell viability when incubated with either free vemurafenib or PLL-CNC-V NPs at increasing concentrations over time (Figure 5). The PLL-CNC-V NPs were less cytotoxic than free vemurafenib in both cell lines up to 24 h of incubation, suggesting the capability of CNC NPs to sustain the release of vemurafenib over time before the cytotoxic effect became similar at 48 h and 72 h of incubation (Table S4, Supporting Information). Moreover, the downstream effects of BRAF inhibition in YUMM1.G1 and A375 cell lines were corroborated with western blot showing that MEK phosphorylation was successfully inhibited with the increase in vemurafenib concentration (Figure S3, Supporting Information) in both of the cell lines. As expected, the PLL-CNC NPs (empty nanosystem) showed no significant cytotoxic effect at any of the concentrations up to 48 h of incubation, which was in accordance with our previous reports [31, 32]. However, a slight decrease in cell viability (< 90%) was observed at 4.5 and 6.7 μg/ml concentrations after 72 h of incubation in both cell lines. This might be due to the potential cytotoxicity induced by the cationic charge of PLL after long exposure time with the cells. Additionally, in order to further corroborate that the cytotoxic effects were primarily arising from the vemurafenib release and effects in the BRAF V600E mutant cell lines, the cytotoxicity of the constructs was assayed in the murine BRAF wild-type B16-F10 melanoma cell line at 24 h and 72 h representing medium and long exposure times. The proportion of viable B16-F10 cells stayed over 90% for all conditions, concentrations and time points. Therefore, the overall results indicate the potential to use of the CNC NPs as a nanocarrier to delivery and sustained release of vemurafenib to tumor cells expressing the BRAF V600E mutation in vivo, while the construct remains safe for non-target cells expressing wild-type BRAF.

Figure 5.

In vitro cell viability studies in BRAF V600E expressing cell lines (human A375 and murine YUMM1.G1 melanoma) and wild-type BRAF expressing melanoma cell line (murine B16-F10) after incubation with free vemurafenib, PLL-CNC NPs, and PLL-CNC V NPs at vemurafenib concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 μM with respective CNC concentrations of 0.5, 2.2, 4.5, and 6.7 μg/mL for 6, 24, 48, and 72 h. For B16-F10 the assay was carried out only at 24 and 72 h. The negative (−) and positive (+) controls for cell viability were fresh cell culture media and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 solution, respectively. The statistical analysis was carried out using the unpaired Student’s t-test in comparison with the negative control where the significant differences were set at *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001. Columns represent the mean ± s.d. (n=4).

2.5. Cellular uptake studies

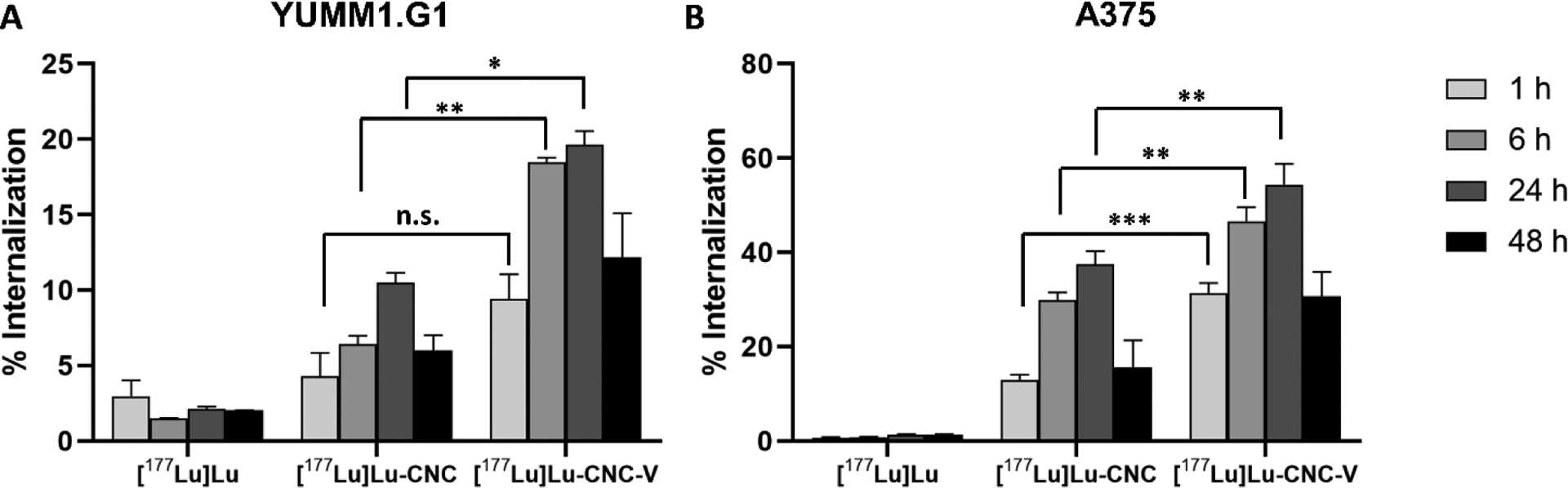

The internalization of NPs into the cells is often needed for successful transportation and accumulation of active molecules (e.g. drugs, DNA, RNA, and imaging agents) to specific intracellular sites. The cellular uptake of non-targeted NPs is usually through the endocytosis pathway and penetration at the lipid bilayer on the cell membrane, however, other internalization pathways can be regulated for targeted NPs, such as ion channels, receptors, and transporters.[44] The uptake mechanisms of NPs vary depending on size, uniformity of the size distribution, shape, and surface properties. Typically, the internalization in cells is qualitatively determined through the visualization of the signal from a fluorescent dye tagged on the surface of NPs using fluorescence microscopy. However, the internalization of the 177Lu-radiolabeled CNC constructs in this work is conveniently evaluated through the quantitative detection of gamma radiation from the 177Lu accumulated within the cells. The results showed that there was no substantial accumulation of free 177Lu3+ in either YUMM1.G1 or A375 cell lines while an increase in internalized radioactivity within the cells was observed with the [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs over time (Figure 6). Both radiolabeled CNC NPs revealed a linear trend of radioactivity accumulation in both cell lines up to 24 h of incubation. Furthermore, [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs exhibited a higher uptake in both cell lines compared to the [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs with double the internalization at all time points. A greater degree of internalization of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs could be a result of the positive surface charge of the NPs (Table S2, Supporting Information), which possibly stimulates a strong interaction with the negatively charged cell membrane. Surprisingly, both the CNC NPs tend to accumulate in human A375 melanoma cells with approximately 3 times higher uptake than in murine YUMM1.G1 melanoma cells at all time points. Unlike spherical NPs, the interaction and internalization mechanisms of rod-shaped NPs, especially the CNC NPs in this work are not completely elucidated and could rely on different factors, including physicochemical properties of the NPs, the cell type, membrane-wrapping energy consumption, activity of endocytosis pathways, and uptake behavior.[45] Moreover, the decrease of internalization after 48 h of incubation was noticed in both the radiolabeled CNC NPs in both tested cell lines. This is likely a result of the cytotoxic effect after long exposure during which the dead cells start to detach from the surface of the culturing plate. The detached cells with their accumulated radioactivity are potentially washed out to the unbound fraction, complicating the determination of the internalized activity at time points beyond 24 hours.

Figure 6.

Cellular uptake of radioactivity after incubation with free [177Lu]Lu, [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs, and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs in (A) murine YUMM1.G1 and (B) human A375 melanoma cell lines at 1, 6, 24, and 48 h of incubation with fixed concentrations of 1 MBq/mL for 177Lu, 40 μg/mL for CNC NPs and 0.1 μM for vemurafenib. The statistic was analyzed using the unpaired Student’s t-test between [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs at the same incubation time point where the significant probabilities were set at n.s. (not significant, p>0.05), *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001. Columns represent the mean ± s.d. (n=3).

2.6. Clonogenic cell survival

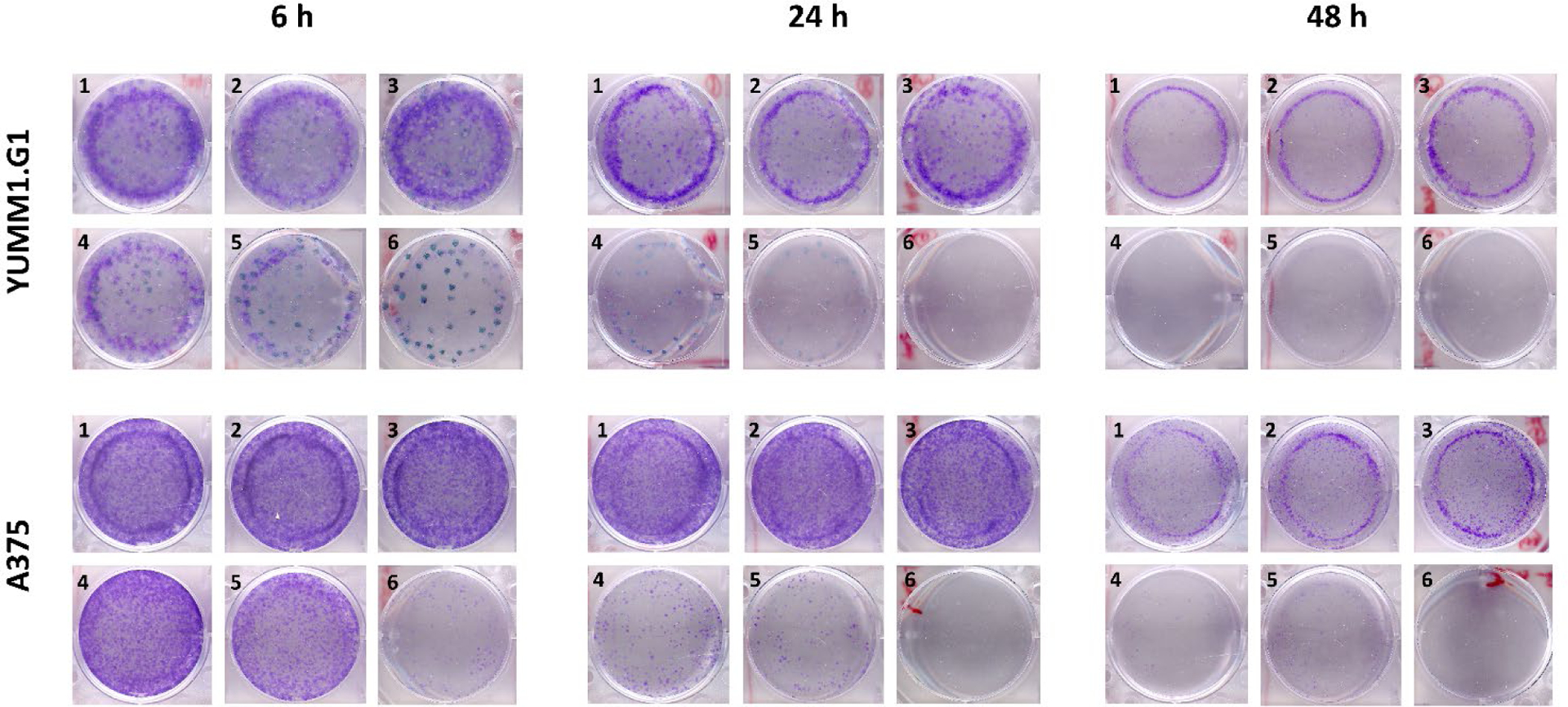

Clonogenic assays are commonly used to investigate the ability of cells to proliferate after exposure to ionizing radiation that induces DNA damage and cell apoptosis, but it is also useful for investigation of the combination of radiation with other treatment modalities.[46] In this experiment, the clonogenic cell survival in YUMM1.G1 and A375 cells was explored after treatments with PLL-CNC NPs, free vemurafenib, free 177Lu3+, [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs, and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs for 6, 24, and 48 h to examine the effects of the chemo–radiotherapeutic combination of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs and the individual nanotheranostic components (Figure 7). As the colonies formed by both cell lines tended to clump together, the plating efficiency and surviving fraction could not be accurately determined. Therefore, the discussion of results herein is simplified as a qualitative analysis through the overall intensity of the crystal violet staining in the samples. The theranostic [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs revealed to be the most effective formulation, and there were no cell colonies formed after 24 and 48 h treatments in both cell lines. There was no clear difference in the stained cell colonies between samples treated with non-radioactive components (vemurafenib and PLL-CNC NPs) alone compared to the negative control in all tested cell lines and time points. Undoubtedly, the PLL-CNC NPs are non-toxic and should not cause cytotoxicity, while in contrast vemurafenib at 0.1 μM should already exhibit cytotoxic effects after 24 h incubation, as shown by the CellTiter-Glo assay results earlier. The lack of cytotoxic effects observed in the clonogenic assay for these components could be a result of drug resistance behavior in which different complex mechanisms, such as the efflux of anticancer drugs, the escape from therapy-induced senescence, and the enhanced DNA damage repair are elicited in response to treatment, which only becomes apparent in the clones grown for the relatively long period of 10 days.[47] Furthermore, the murine YUMM1.G1 cell line appears to be more radiosensitive than the human A375 cell line by comparison of the intensity of the crystal violet staining; however, the mechanisms underlying the differences in intrinsic radiosensitivity of cancer cell lines are variable and still under investigation.[48]

Figure 7.

Representative qualitative clonogenic cell survival assay in murine YUMM1.G1 and human A375 melanoma cells regrown after treatments in fresh medium (1), PLL-CNC NPs (2), free vemurafenib (3), free 177Lu (4), [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs (5), and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs (6) at doses of 1 MBq/mL for 177Lu, 40 μg/mL for CNC NPs, and 0.1 μM for vemurafenib at 6, 24, and 48 h.

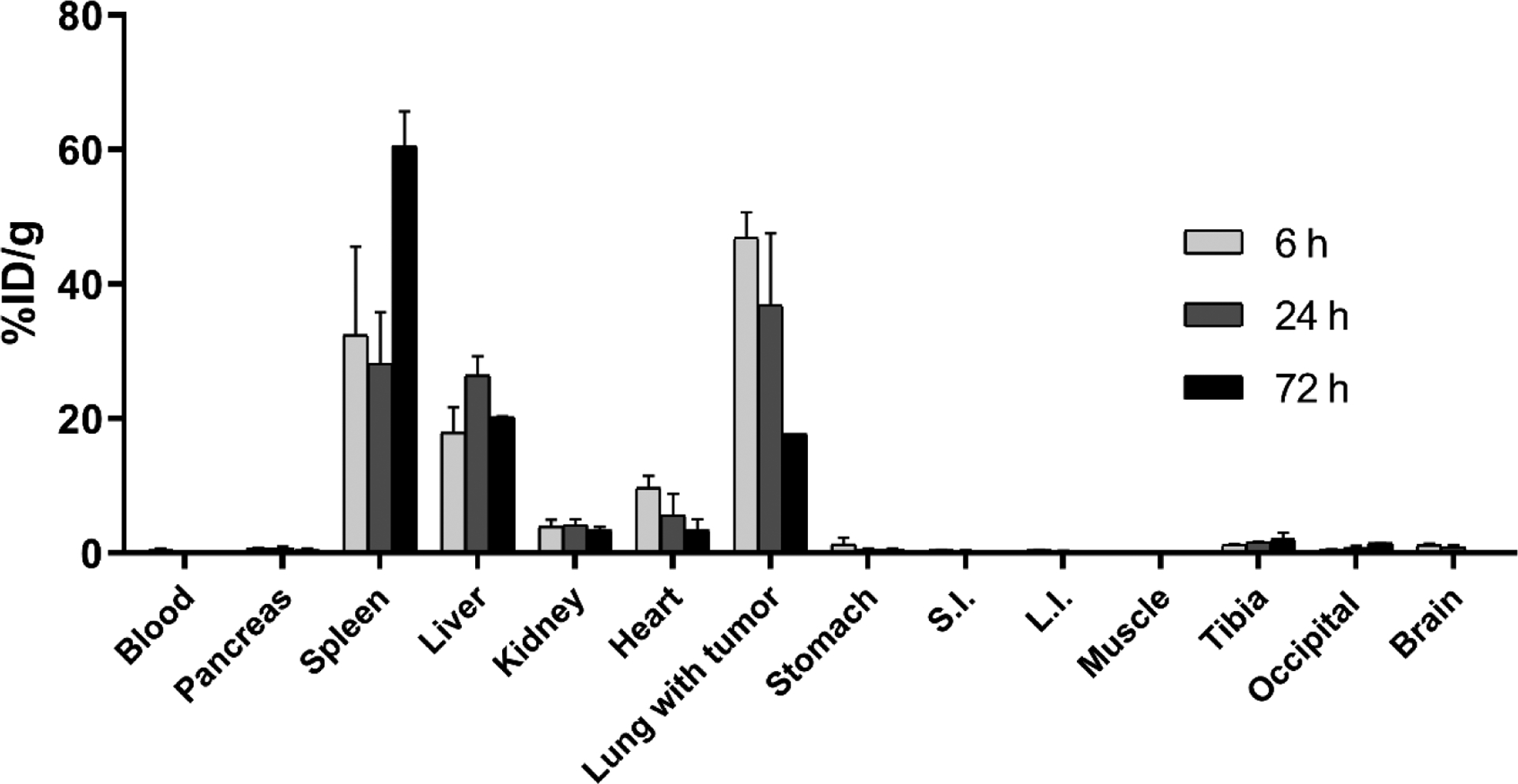

2.7. Ex vivo biodistribution and dosimetry

The ex vivo biodistribution of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs was first evaluated in YUMM1.G1 lung metastatic melanoma bearing C57BL/6NRj female mice prior to the therapeutic studies as the first step to examine the distribution profiles of the developed theranostic CNC NPs in vivo as a function of time. The YUMM1.G1 cell is a congenic mouse melanoma cell line with C57BL/6J strain background and with defined genotype of BrafV600E/wt Pten−/− Cdkn2−/− Mc1re/e developed in the Yale University Mouse Melanoma (YUMM) series.[49] The [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs were successfully radiolabeled with 177Lu (RCY = 64%) and loaded with vemurafenib (%LE = 19%) with a high radiochemical purity (RCP = 98.9%) upon the administration. The final concentrations of CNC NPs, vemurafenib, and 177Lu were 1 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg, and 1.2 MBq/injection, respectively, formulated in 150 μL of sterilized 1×PBS supplemented with 5% Solutol HS 15. As expected, the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs demonstrated high but transient retention in the lung with average values of 47 %ID/g at 6 h, 37 %ID/g at 24 h, and 18 %ID/g at 72 h, which correspond to our previous report on the behavior of [111In]In-CNC NPs in vivo.[31] The transient accumulation is likely a result of the rheology of the needle-like particles in the lung vascular bed, as they tend to tumble close to the vessel walls and can potentially embolize in narrow capillaries and tumor neovascularization.[50,51] No acute adverse effects of this trapping were seen in the mice as the dispersion stability is properly maintained by the solubilizer in the optimized NP formulation. Major uptake was also seen in the liver (18–26 %ID/g) and spleen (28–60 %ID/g), which are sites for the clearance of non-targeted NPs through the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). The values in the kidney (< 4 %ID/g) and other excised tissues (< 1 %ID/g) revealed no significant accumulation over the period of studies indicating in vivo stability of the construct. Furthermore, there was no acute toxicity or severe side effects noticed during the course of the biodistribution studies. Therefore, the biodistribution profile and animal health status after the treatment suggest the potential use of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs for treating melanoma metastasis in the lung through the enhanced retention in the lung vascular bed and potentially in the metastasis neovasculature itself.

The results of the ex vivo biodistribution were used to estimate the absorbed dose in select organs, which could be used as a guideline for the safe administration dose of [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs in order to minimize the radiation burden in non-target organs. The dosimetry calculation showed high total absorbed doses in the lung with tumor (232.38 cGy/MBq), liver (418.33 cGy/MBq), and spleen (1056.03 cGy/MBq) while only low absorbed doses were observed in the kidney (54.26 cGy/MBq), heart (36.42 cGy/MBq) and other tissues (< 5 cGy/MBq, Table S5, Supporting Information). There is not much research to date on the dosimetry or radiotoxicity of 177Lu-radiolabeled nanoparticles in small animal models. However, widely varying doses ranging from 6–55.5 MBq of 177Lu-radiolabeled peptides and antibodies have been used in therapeutic studies for mice[52–55], which could be used as a starting point for the estimation of safe radioactive doses in the treatment plan. Naturally, the clearance patterns and rates for peptides and antibodies are considerably different from nanomaterials, and the role of the spleen as a dose-limiting organ in this experimental setup cannot be overlooked.

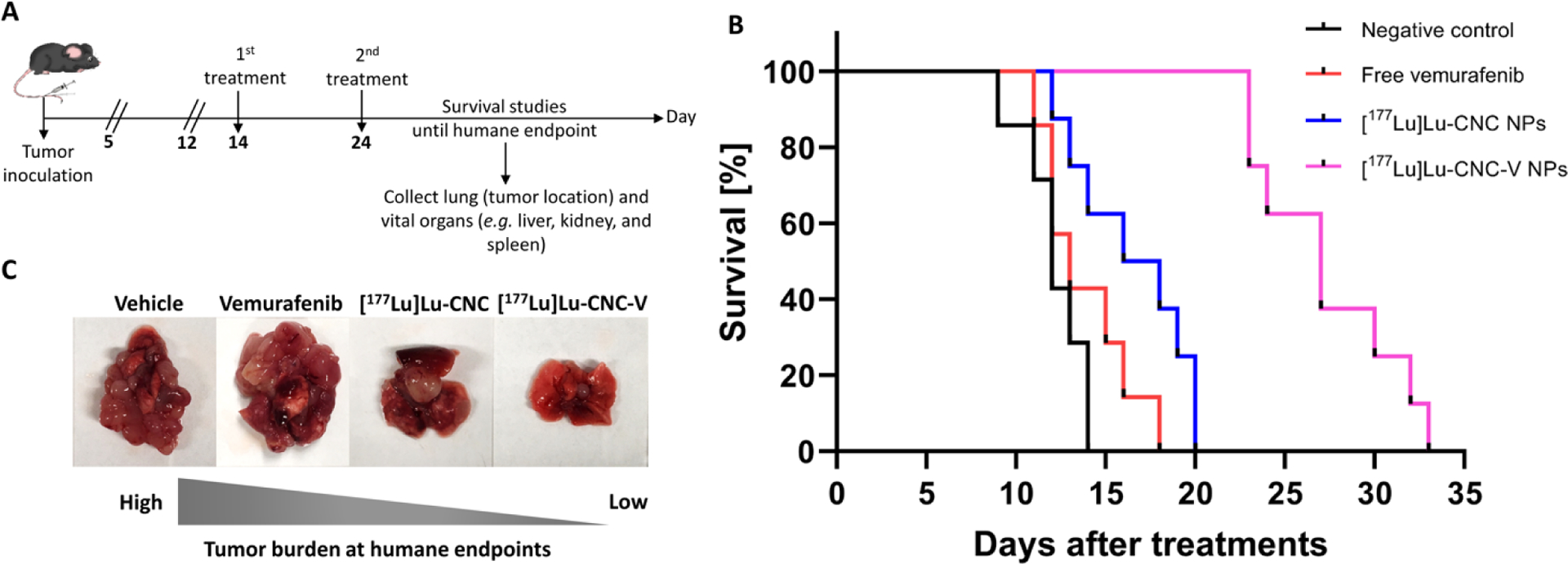

2.8. Therapeutic studies

Following the biodistribution study, therapeutic studies were conducted to explore the potential synergistic effects of vemurafenib chemo- and 177Lu radiotherapy delivered by the theranostic [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs through monitoring of the survival rate of YUMM1.G1 lung metastatic melanoma-bearing animals comparing to the survival in animals treated with the vehicle only (negative control), free vemurafenib (positive control), and the [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs alone. The [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs were selected as the single-modality treatment where the therapeutic efficacy is solely generated from the ionizing radiation of 177Lu, as the biodistribution pattern of free 177Lu3+ would be considerably different and studying the radiometal alone would not be meaningful in terms of tumor accumulation according to the results of the cell uptake assay in YUMM1.G1. After 14 days of tumor inoculation, the first treatment was administered followed by the second round of treatment after 10 days. The animal weight and body condition score were monitored daily after the initiation of the treatment and lung with tumor tissues and vital organs (e.g. liver, kidney, and spleen) were collected to observe the tumor burden and potential metastasis in other organs at the humane endpoint (Figure 9A). The injected [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs were prepared at high radiolabeling yield and radiochemical purity. The radiochemical yield, radiochemical purity, drug loading efficiency, and drug loading degree of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs in both constructs are compiled in Table S6, Supporting Information. The administered doses of 177Lu, vemurafenib, and CNC NPs were fixed at 2 MBq, 3.5 mg/kg, and 1.25 mg/kg respectively per treatment round. The humane endpoints were set based on the weight loss exceeding the 20% threshold using the weight on the second treatment day as the baseline in combination with the health status of the animals (body condition score of 2 on two consecutive observations, labored breathing and cyanosis). The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed superior therapeutic effect of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs compared to other groups (the Mantel-Cox test, p-value < 0.0001) after treatments (Figure 9B). The animals treated with the theranostic [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs displayed the longest median survival time of 27 days after treatment followed by cohorts treated with the [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs (17 days), free vemurafenib (13 days), and vehicle (12 days). There was no acute toxicity observed in any of the treatment groups upon administration. The survival studies demonstrated the evident synergism of vemurafenib chemotherapy and 177Lu radiotherapy generated from the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs in pulmonary metastatic melanoma model, which pave the way for the development of CNC-based theranostic nanosystem for combination therapy of metastatic melanoma with improved pharmacokinetics and antitumor efficacy.

Figure 9.

(A) Timeline of therapeutic studies, (B) Kaplan-Meier survival plot as a function of time after treatments with the vehicle (negative control), free vemurafenib, [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs, and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs (n=7–8/group), where the administered doses of vemurafenib, CNC NPs, and radioactivity were fixed at 3.5 mg/kg, 1.25 mg/kg, and 2 MBq per animal per treatment round, respectively. Day 0 on the x-axis indicates as the day of the second treatment, and (C) Representative images of tumor burden in the lung tissue collected at the humane endpoint of each injected formulation.

Furthermore, cohort treated with the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs showed less tumor burden in the lung at the humane endpoint compared to the other treatment groups (Figure 9C). Although the survival of mice treated with the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs was improved, it could not be further prolonged in this study because of ultimately fatal secondary metastases found in the cardiac muscle (75%, 6/8, Figure S4, Supporting Information) and thoracic cavity (25%, 2/8). These were not discovered in other treatment groups, suggesting that they are not characteristic of the progression of YUMM1.G1 tumors. Further studies into this are warranted, as this is to our knowledge the first account of the use of this cell line in an orthotopic model of lung metastatic melanoma. In general, cardiac metastasis is rarely found at the first instance in intravenous models, which is similar to the observations in this study. This might be a result of the escape of radiation or vemurafenib resistant cells from the original tumor site. There are four possible pathways to the spread of cells to the heart and chest cavity, including direct extension, the bloodstream, the lymphatic system, and intracavitary diffusion through the inferior vena cava or pulmonary veins.[56] Among these, the lymphatic system is believed to be the most plausible route since lung and heart have multiple connective lymph channels that resistant melanoma cells migrate in, coalesce into the mediastinum and eventually drain to the thoracic duct.[57] Future efforts should be targeted to resolving this issue with the DDS, potentially by increasing the radioactive or pharmaceutical doses or adjusting the timing and frequency of the therapeutic administration which fell beyond the scope of this study. Also, studies with less aggressive human BRAF V600E-positive A375 xenografts or patient-derived xenografts are warranted. Histological examination of the H&E sections of select vital organs after treatment with all formulations revealed normal architecture with no sign of radiation burden or secondary metastasis compared to the vehicle control group (Figure S5, Supporting Information). This indicated no severe radiotoxicity in liver and spleen tissues after two consecutive treatments and suggested safety of the theranostic formulation. However, the immunohistochemical Ki-67 staining of the lung infiltrated tumor at the humane endpoints showed no significant difference in cell proliferation markers in all treatment groups (Figure S5, Supporting Information). This is likely because the animals from each group were euthanized upon meeting the criteria for a humane end point, at a minimum of 12 days after the second treatment (vehicle group) or considerably later, not at a fixed time point after the treatment. As a consequence, differences in the impact of the treatments on the proliferative capacity of the tumor cells could not be detected. These effects between the treatment groups could have been more evident closer to the time of theranostic nanosystem administration. Furthermore, in patients, BRAF kinase inhibition has been shown to elicit severe adverse effects if not discontinued during external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) which were not seen in this study with local radiotherapy.[58] The radiosensitizing effect of vemurafenib could therefore be harnessed to potentiate the effects of the radiotherapy in this previously unexplored strategy to the treatment of pulmonary metastasis of melanoma.

In summary, the therapeutic study results confirm that the transient trapping of the theranostic CNC NP-based DDS in the lung is a viable strategy for therapeutic delivery to the lung and to pulmonary metastases, alluding to potential clinical utility of CNC-based DDS after systemic administration, which has remained challenging with CNC-based biomaterials to date.

3. Conclusion

Taken together, the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs developed in this work demonstrate the feasibility of using CNC NPs as a naturally sourced and renewable nanoscale platform for theranostic nanosystems for the treatment of BRAF V600E positive metastatic melanoma in the lung with radiotherapy and kinase inhibition after systemic delivery. The energy and tissue range of β− particles emitted by 177Lu as well as the rate of the sustained release of the vemurafenib were appropriate for the application, resulting in the prolonged survival of YUMM1.G1 tumor-bearing mice receiving the theranostic combination. The system is modular, as the trivalent radiometal, the capping agent and drug payload can be exchanged to generate new theranostic combinations and tailor the properties of the DDS. Furthermore, future efforts should be dedicated to elucidating the mechanism of the transient trapping of the CNC NPs in the lung and the possibility of modulating this behavior through CNC NP engineering to enhance delivery to lung tissue and pulmonary metastasis.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Materials and Chemicals

All general chemicals and anhydrous organic solvents as well as human serum were purchased from Merck (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) unless otherwise denoted and used without additional purification. Cotton fiber derived CNC NPs were prepared from ashless Whatman® filter paper through acid hydrolysis as described in literature[59,60] and the acid residue was washed out with excess amount of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and ultrapure water before further syntheses. The 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7-tris(acetic acid)-10-(4-aminobutyl) acetamide (DOTA-amine or DOTA-NH2) was acquired from Macrocyclics (Plano, TX, U.S.A.). Vemurafenib (purity > 98%) was obtained from Adooq® Bioscience (Irvine, CA, U.S.A.). Poly-L-lysine hydrochloride or PLL (MW 1.6 kDa with 10 repeating units of L-lysine) was purchased from Alamanda Polymers (Huntsville, AL, U.S.A.). The dialysis membrane (MWCO 12–14 kDa) was obtained from Spectrum Laboratories (Waltham, MA, U.S.A.). 177LuCl3 was acquired from Curium Pharma (Petten, The Netherlands). The polypropylene protein LoBind microcentrifuge tubes (1.5 mL) were obtained from Eppendorf (Hamburg, Germany). The Solutol HS 15 solubilizer was acquired from BASF ChemTrade GmbH (Burgbernheim, Germany). The glass microfiber chromatography sheets impregnated with silicic acid (iTLC-SA) was acquired from Agilent Technologies (Folsom, CA, U.S.A.). Donor human plasma (FFP 24) was obtained from the Finnish Red Cross Blood Service (Helsinki, Finland) under an ethical approval for research purposes. Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm at 25 °C, 2 ppb TOC) was prepared in-house by a Milli-Q® Integral 10 water purification unit equipped with 0.22 μm Millipak® Express 40 membrane filter (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, U.S.A.) at the point of dispense for producing bacteria- and particulate-free ultrapure water. Cell culture reagents and general procedures are described in the Supporting Information.

4.2. Preparation of DOTA-modified CNC NPs

The bifunctional DOTA chelator-functionalized CNC (DOTA-CNC) NPs used in this work were synthesized by the conjugation of DOTA-amine to the hydroxyl groups on the surface of the CNC NPs as previously reported.[31] Briefly, the CNC NPs were dispersed in anhydrous DMSO at a concentration of 5 mg/mL and sonicated for 5 min at 20% amplitude tip sonicator (QSonica, Newton, CT, U.S.A.). Carbonyldiimidazole (CDI, 2 eq w/w) in anhydrous DMSO was added to the CNC solution while flushing with argon flow and constant agitation. The reaction was left stirring overnight in a temperature-controlled silicone oil bath at 60 °C under argon atmosphere. The unreacted CDI was washed out twice with 5 mL of fresh DMSO and the CDI-activated CNC NPs were collected by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 5 min (Heraeus Megafuge 1.0R, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.). The CDI-activated CNC NPs were redispersed in anhydrous DMSO (5 mg/mL) and the solution was constantly flushed with argon flow for 10 min while stirring. Then, the DOTA-amine (1 eq w/w) in anhydrous DMSO was added dropwise to the CDI-activated CNC solution. The reaction was continued for 3 days under argon atmosphere at 60 °C, meanwhile, the argon balloon was refilled daily to maintain a sufficient inert atmosphere inside the reaction flask. Following the 3-day reaction, the mixture was centrifuged, and the collected DOTA-CNC NPs were washed twice with 5 mL of fresh DMSO to remove any unreacted DOTA-amine. The DOTA-CNC NPs were further dialyzed against ultrapure water for 3 days with at least 4 changes of water daily. Finally, the DOTA-CNC NPs were collected by centrifugation and lyophilized.

4.3. Material characterization

The elemental composition of unmodified and modified CNC NPs was analyzed using a Vario MICRO Cube CHNS analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Lagenselbold, Germany) and are reported as percent of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and nitrogen (N). The CNC NPs were further characterized with a Spectrum™ One Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR) equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) unit (PerkinElmer Instruments LLC, Shelton, CT, U.S.A.). The electrokinetic potential of unmodified and modified CNC NPs in ultrapure water (ζ-potential) was measured using a Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern, Worcestershire, U.K.) at a concentration of 300 μg/mL. The morphology and dimensions (width and length) of CNC NPs were determined with a Hitachi S-4800 field emission-scanning electron microscope at 10 kV (FE-SEM, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The FE-SEM samples were prepared by dispersing the CNC NPs in ultrapure water at a concentration of 25 μg/mL and sonicated for 2 min. The silicon wafer substrates were taped to the cylindrical specimen holder and wiped with ultrapure water followed by blowing with the compressed air to remove dust from the surface. Then, an aliquot of CNC samples (10 μL) was applied on the silicon wafer and left to dry in a desiccator overnight. The same procedure was repeated once on each substrate in order to get an adequate number of particles for the imaging. Prior to imaging, the samples were coated with a 3-nm layer of Au-Pd alloy in a high-resolution sputtering coater (208HR, Cressington Scientific Instruments, Watford, U.K.) in order to increase the conductivity and signal-to-noise ratio of the samples. The dimensions (width and length) of each sample (n ≥ 100 particles) were determined from the images using ImageJ 1.52i software.

4.4. Radiolabeling of DOTA-CNC NPs

Before radiolabeling experiments, ultrapure water used for the preparation of all radiolabeling buffer solutions was pretreated with Chelex® 100 ion-exchange resin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.) at a concentration of 5 g/L for 24 h and filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane to obtain the metal-free water. The DOTA-CNC NPs (1 mg/mL) were dispersed in 0.2 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 4.0) in a 1.5-mL Protein LoBind microcentrifuge tube (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The DOTA-CNC solution was sonicated for 5 min at 20% amplitude on a tip sonicator. 177LuCl3 (20–180 MBq) was added to the DOTA-CNC solution. The radiolabeling reaction was heated to 100 °C in a digital dry bath heater (AccuBlock™, Labnet International, Edison, NJ, U.S.A.) placed on an orbital shaker at 600 rpm for 1 h. Following the incubation, the reaction mixture was equilibrated to room temperature and quenched with 100 μL of 50 mM DTPA solution. The reaction vial was centrifuged at 10 000 g for 5 min to collect the [177Lu]Lu-CNC pellet. The supernatant was removed, and the product pellet was purified with sequential washes in 50 mM DTPA solution twice, three times with 1×PBS (pH 7.4), and once with metal-free ultrapure water with collection of the radiolabeled CNC NPs by centrifugation after each step. The radioactivity in both supernatant and collected pellet was monitored using a VDC-603 dose calibrator (VIK-202 ionization chamber model, Comecer, Joure, The Netherlands) after every step. Then, the purified radiolabeled product was redispersed in 1×PBS (pH 7.4) and quality control was done by radio-TLC. An aliquot of radiolabeled CNC solution (1–2 μL) was spotted on the iTLC-SA chromatography sheet and run in a closed glass chamber with 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 5.0). The [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs remain at the baseline of application spot while the free 177Lu3+ moves along with the solvent front (Rf = 0.9–1.0). After air-drying, the iTLC-SA sheet was exposed to a digital imaging plate for photostimulated luminescence (PSL) detection (Fuji BAS-TR2025, 20×25 cm) for 2 min. The imaging plate was scanned on a Fujifilm Fluorescent Image Analyzer (FLA-5100 V.1, Fuji Film Photo, Tokyo, Japan). The radiochemical purity (RCP) of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs was analyzed using AIDA image analysis software version 5.0 SP 3 (Elysia-Raytest GmbH, Straubenhardt, Germany).

4.5. Radiolabel stability and EDTA/Fe3+ challenges

The in vitro radiolabel stability of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs was evaluated in simulated physiological conditions, including 1×PBS (pH 7.4), and 50 and 100% human plasma, and in the presence of competing 0.2 mM FeCl3 and 2 mM EDTA. The [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs were dispersed in the specified buffer at a concentration of 100 μg/mL and incubated at 37 °C at 500 rpm. Samples (2 μL) were drawn and spotted on the iTLC-SA chromatography paper at specified time points (1, 2, 4, 6, 16, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h). The radio-TLC chromatograms were run in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 5.0) and the percentage of 177Lu remaining on the surface of the CNC NPs was quantified using digital autoradiography as described in the previous section. All assays were carried out in triplicate.

4.6. Drug loading

The drug loading of both non-radiolabeled and radiolabeled CNC NPs was carried out in a one-pot reaction. Either unmodified CNC NPs or [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs (1 mg) were dispersed in 200 μL of anhydrous DMSO in a 1.5-mL Protein LoBind microcentrifuge tube. Vemurafenib (1:1 w/w) and PLL (1:10 w/w) in anhydrous DMSO were added to the CNC dispersion. The reaction volume was adjusted with fresh anhydrous DMSO to a total solid concentration to 6 mg/mL. The reaction mixture was sonicated for 2 min at 30% amplitude and further incubated at 37 °C for 1 h on a shaker at 750 rpm (Eppendorf Thermomixer C, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The reaction vial was centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and filtered through a 0.2 μm PVDF 13-mm diameter filter (Acrodisc, Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY, U.S.A.). The amount of vemurafenib in the supernatant (unbound drug) was quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (Prominence HPLC system, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The separations were carried out on a reverse-phase XBridge™ C18 analytical column (130 Å, 5 μm, 4.6×250 mm, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, U.S.A.) with an isocratic flow of 0.1 M glycine buffer (pH 9.0) and acetonitrile (45:55) eluent system at a flow rate of 0.9 mL/min, and 254 nm UV detection. The retention time of vemurafenib was 8.70–8.79 min. The amount of vemurafenib was quantified using a vemurafenib standard curve ranging from 1.56–200 μg/mL (R2 = 1). The drug loading efficiency (%LE) and loading degree (%LD) were determined using equations detailed in the Supporting Information. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

4.7. In vitro drug release profiles

The in vitro drug release experiments were conducted in 1×PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and tumor microenvironment mimicking conditions (10 mM acetate buffer pH 5.5, representing the late endosome).[61] Both buffer systems were supplemented with 10% (v/v) human serum to induce sink conditions for drug dissolution. The non-radiolabeled PLL-CNC-V NPs and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs containing 200 μg of CNC NPs and 22 μg of vemurafenib were dispersed in 500 μL of the respective buffers in Protein LoBind microcentrifuge tubes and incubated at 37 °C with 500 rpm shaking. At each time point (1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h), sample vials were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant separated to a new microcentrifuge tube. The sample pellets were redispersed with an equal initial volume (500 μL) of corresponding media and the incubation was continued. Proteins in the isolated supernatant were denatured by adding an ice-cold acetonitrile (1:1 v/v) and pelleted by centrifugation at 9 000 g for 10 min. The protein precipitates were discarded, and the collected supernatants were lyophilized overnight. The lyophilized samples were dissolved in 500 μL of HPLC grade DMSO and passed through 0.2 μm PVDF filter before HPLC analysis. The amount of released vemurafenib was quantified using the HPLC method described previously. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

4.8. In vitro cell viability studies

The in vitro cytotoxicity was determined using a commercial CellTiter-Glo® luminescent cell viability assay which is the most appropriate assay for the CNC NPs according to previous reports [31, 32]. Murine YUMM1.G1 and human A375 cell lines were chosen as mouse and human melanoma cell models harboring the activating BRAF V600E mutation while murine B16-F10 skin melanoma cell expressing wild-type BRAF gene was used as the negative control cell line. Cells were plated at a density of 5 000 cells per well on an opaque-walled 96-well plate with clear bottom in 100 μL of the corresponding media and allowed to attach overnight. The media was removed and replaced with 100 μL of the corresponding media containing free vemurafenib, PLL-CNC NPs (empty particle), or PLL-CNC-V NPs at drug concentration of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 μM. The PLL-CNC NP concentrations were determined in correspond with the amount of the CNC NPs used in the PLL-CNC-V formulation: 0.5, 2.2, 4.5, and 6.7 μg/mL for 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 μM, respectively. Fresh medium and Triton X-100 solution (1% v/v) were used as negative and positive controls for cytotoxicity, respectively. The plates were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 atmosphere and 95% relative humidity for 6, 24, 48, and 72 h. Moreover, to corroborate the sensitivity of the cell lines to vemurafenib, western blot analysis was carried out to observe the decrease in phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK, the downstream target of BRAF) in response to vemurafenib at 0.1 and 1 μM concentration for 6, 24, and 48 h. The protocols for cytotoxicity determination and western blot analysis are detailed in the Supporting Information.

4.9. Cellular uptake studies of radiolabeled CNC constructs

The in vitro cell internalization of radiolabeled CNC constructs was studied in YUMM1.G1 and A375 melanoma cell lines. Cells were seeded on a transparent 12-well plate at a density of 25 000 cells per well and allowed to attach overnight. Prior to the experiments, the cells were acclimatized to the CO2 independent medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin at 37 °C incubator with 0% CO2 for at least 30 min. The medium was removed and replaced with 1 mL of CO2 independent medium containing free 177LuCl3+, [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs, or [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs. The radioactivity of 177Lu in each sample was set at 1 MBq/mL while the CNC NPs and vemurafenib doses were 40 μg/mL and 0.1 μM, respectively. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1, 6, 24, and 48 h. At each time point, the cells were treated to yield fractions for unbound, membrane-bound and internalized radioactivity. Details for the uptake protocol are described in the Supporting Information.

4.10. Clonogenic assay

The in vitro clonogenic cell survival was evaluated in murine YUMM1.G1 and human A375 melanoma cell lines. Both cell lines were treated with non-radiolabeled PLL-CNC NPs, free vemurafenib, free 177LuCl3+, [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs, and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs while the untreated cells (negative control for cytotoxicity) were incubated with CO2 independent medium throughout the study. The concentrations of radioactivity, CNC NPs, and vemurafenib were fixed at 1 MBq/mL, 40 μg/mL, and 0.1 μM, respectively. At the specified time points (6, 24, and 48 h), the cells were collected and cultured for further 10 days in fresh medium on 6-well plates. At the end of the assay period, the cell colonies were stained with crystal violet and the plates scanned for colony observation. The experimental procedure is described in the Supporting Information.

4.11. Ex vivo biodistribution, dosimetry, and therapeutic studies

All animal experiments in this work were conducted under a project license number ESAVI/12132/04.10.07/2017 approved by the National Board of Animal Experimentation in Finland and in compliance with the European Union Directive 2010/63/EU. In general, animals were group-housed in conventional polysulfones cages supplied with aspen bedding, nesting material (Tapvei®, Harjumaa, Estonia) and enrichment (aspen blocks and disposable cardboard hut). Pelleted food (Teklad 2019C diet, Envigo, Huntingdon, U.K.) and tap water were provided ad libitum. The environmental conditions of the animal housing unit were maintained at 12:12 h light/dark cycle, 22±1 °C, and 55±15% relative humidity throughout the experimental period. Both ex vivo biodistribution and therapeutic studies were carried out in YUMM1.G1 lung metastatic melanoma-bearing C57BL/6NRj mice (female, weighing 16–19 g, aged 8–12 weeks, Janvier Laboratories, Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France). For orthotopic model of YUMM1.G1 metastatic melanoma in the lung, 1×106 YUMM1.G1 cells in 150 μL sterilized 1×HBSS (viability > 95%) were intravenously injected via the lateral tail vein to conscious mice. The tumors were allowed to develop for at least 14 days before start of the nanotheranostic studies.

For ex vivo biodistribution, the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs were intravenously injected via the tail vein at a dose of 1.2 MBq of 177Lu, 1 mg/kg of CNC NPs and 2 mg/kg of vemurafenib in 150 μL of sterilized 1×PBS (pH 7.4) supplemented with 5% (v/v) Solutol HS 15. At predetermined time points (6, 24, and 72 h), mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation to harvest interest tissue samples, including blood, pancreas, spleen, stomach, liver, kidney, lung with tumor, heart, small intestine, large intestine, skeletal muscle, tibia, occipital bone, and brain. The tissue samples were individually collected and weighted in the 5-mL liquid scintillation tubes. The radioactivity in tissue samples was counted using an automatic gamma counter 1480 Wizard™ 3” and the results expressed as percent of injected dose per weight of tissue (%ID/g). The number of animals was set at n = 3 per time point.

Following the ex vivo biodistribution study, the average activity concentration of 2–3 tissue specimens from each time point was fitted to a biexponential function to create a time-activity curve (TAC). For most tissues, the best TAC fit comprised of a one- or two-phase exponential decay model. Notably, spleen exhibited marked uptake over the measured time course, therefore, a trapezoidal model was used for this tissue up to the latest time point, after which it was assumed that clearance was determined entirely by radioactive decay. The cumulative uptake was calculated from the area under the uptake curves. The absorbed dose to all organs was estimated based on the assumption that the absorbed fraction is equal to 1 for β− emission of 177Lu and 0 for the penetrating photon emission with the equilibrium absorbed dose constant of 0.085g·Gy/MBq·h (0.31 g·cGy/μCi·h). The estimated absorbed dose (cGy/MBq) in an individual organ was used as a guideline for the administration plan of safe and effective radiation dose in therapeutic studies to minimize the radiation burden in healthy tissues after the nanotheranostic construct administration.

In therapeutic studies, the animals were randomized into 4 groups after 14 days of the YUMM1.G1 tumor inoculation: vehicle (1×PBS with 6% Solutol HS 15), free vemurafenib (3.5 mg/kg), [177Lu]Lu-CNC NPs, and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs (n=7–8 per group). The [177Lu]Lu-CNC and [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V groups were treated with the corresponding theranostic CNC formulations containing 2 MBq of 177Lu, 1.25 mg/kg of CNC NPs, and 3.5 mg/kg of vemurafenib per treatment cycle. The second treatment for all groups was done 10 days after the first treatment. The animal weight and condition using body condition scoring[62] were monitored and recorded daily until the humane endpoint. At the endpoint, the lung tissue with the tumor and select vital organs (liver, spleen, and kidney) were collected in 10% (v/v) neutral buffered formalin and sent to histological analysis with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry for proliferation using the Ki-67 marker. Details for the immunohistochemical procedure are given in the Supporting Information.

4.12. Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n≥3). A direct comparison between sample groups was made using unpaired Student’s t-tests where the statistical significance (p-value) was set at *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001. The survival in therapeutic studies was determined using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with GraphPad Prism software version 8.0.1 (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

Supplementary Material

Figure 8.

Ex vivo biodistribution profiles of the radioactivity after the administration of the [177Lu]Lu-CNC-V NPs in YUMM1.G1 lung metastatic melanoma-bearing C57BL/6NRj female mice at 6, 24, and 72 h post-injection. The values represent the mean ± s.d. (n=3). %ID/g = percent of injected dose per gram of tissue, S.I. for small intestine, and L.I. for large intestine.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Finnish Cultural Foundation (grant no. 00190375), the Academy of Finland (decision nos. 318422, 278056, 298481, 302102, and 331659), and the University of Helsinki Research Funds are gratefully acknowledged. Finnish Center for Laboratory Animal Pathology (FCLAP) at HiLIFE, University of Helsinki, is acknowledged for the tissue preparation and staining services. The authors also thank Dr. Jaakko Sarparanta for help with phospho-MEK western blot, Ms. Karina Moslova for assistance with the elemental analysis, Ms. Alexandra Correia for assistance with cell culture, and Ms. Phetcharada Imlimthan for the assistance with the images.

Footnotes

Supporting information

Supporting information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Leonardi GC; Falzone L; Salemi R; Zanghi A; Spandidos DA; McCubrey JA; Candido S; Libra M, Int J Oncol 2018, 52 (4), 1071–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Davis LE; Shalin SC; Tackett AJ, Cancer Biol Ther 2019, 20 (11), 1366–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Maverakis E; Cornelius LA; Bowen GM; Phan T; Patel FB; Fitzmaurice S; He Y; Burrall B; Duong C; Kloxin AM; Sultani H; Wilken R; Martinez SR; Patel F, Acta Derm Venereol 2015, 95 (5), 516–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Erdei E; Torres SM, Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2010, 10 (11), 1811–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Massague J; Obenauf AC, Nature 2016, 529 (7586), 298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Holderfield M; Deuker MM; McCormick F; McMahon M, Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14 (7), 455–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bottos A; Martini M; Di Nicolantonio F; Comunanza V; Maione F; Minassi A; Appendino G; Bussolino F; Bardelli A, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109 (6), E353–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Griffin M; Scotto D; Josephs DH; Mele S; Crescioli S; Bax HJ; Pellizzari G; Wynne MD; Nakamura M; Hoffmann RM; Ilieva KM; Cheung A; Spicer JF; Papa S; Lacy KE; Karagiannis SN, Oncotarget 2017, 8 (44), 78174–78192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cheng L; Lopez-Beltran A; Massari F; MacLennan GT; Montironi R, Mod Pathol 2018, 31 (1), 24–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yao Z; Yaeger R; Rodrik-Outmezguine VS; Tao A; Torres NM; Chang MT; Drosten M; Zhao H; Cecchi F; Hembrough T; Michels J; Baumert H; Miles L; Campbell NM; de Stanchina E; Solit DB; Barbacid M; Taylor BS; Rosen N, Nature 2017, 548 (7666), 234–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dankner M; Rose AAN; Rajkumar S; Siegel PM; Watson IR, Oncogene 2018, 37 (24), 3183–3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shinozaki M; Fujimoto A; Morton DL; Hoon DS, Clin Cancer Res 2004, 10 (5), 1753–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lidsky M; Antoun G; Speicher P; Adams B; Turley R; Augustine C; Tyler D; Ali-Osman F, J Biol Chem 2014, 289 (40), 27714–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Saei A; Eichhorn PJA, Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11 (8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Manzano JL; Layos L; Buges C; de Los Llanos Gil M; Vila L; Martinez-Balibrea E; Martinez-Cardus A, Ann Transl Med 2016, 4 (12), 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Luebker SA; Koepsell SA, Front Oncol 2019, 9, 268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chan XY; Singh A; Osman N; Piva TJ, Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18 (7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Langbein T; Weber WA; Eiber M, J Nucl Med 2019, 60 (Suppl 2), 13S–19S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yong KJ; Milenic DE; Baidoo KE; Brechbiel MW, Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17 (5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Azorin-Vega E; Aranda-Lara L; Torres-Garcia E; Santiago-Banuelos JA, Appl Radiat Isot 2019, 146, 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Din FU; Aman W; Ullah I; Qureshi OS; Mustapha O; Shafique S; Zeb A, Int J Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 7291–7309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Egusquiaguirre SP; Igartua M; Hernandez RM; Pedraz JL, Clin Transl Oncol 2012, 14 (2), 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cukierman E; Khan DR, Biochem Pharmacol 2010, 80 (5), 762–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Senapati S; Mahanta AK; Kumar S; Maiti P, Signal Transduct Target Ther 2018, 3, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xin Y; Yin M; Zhao L; Meng F; Luo L, Cancer Biol Med 2017, 14 (3), 228–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Klemm D; Heublein B; Fink HP; Bohn A, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2005, 44 (22), 3358–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Reiniati I; Hrymak AN; Margaritis A, Crit Rev Biotechnol 2017, 37 (4), 510–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bondeson D; Mathew A; Oksman K, Cellulose 2006, 13 (2), 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Beck-Candanedo S; Roman M; Gray DG, Biomacromolecules 2005, 6 (2), 1048–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Heise K; Delepierre G; King AWT; Kostiainen MA; Zoppe J; Weder C; Kontturi E, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2020, 10.1002/anie.202002433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Imlimthan S; Otaru S; Keinänen O; Correia A; Lintinen K; Santos HA; Airaksinen AJ; Kostiainen MA; Sarparanta M, Biomacromolecules 2019, 20 (2), 674–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Imlimthan S; Correia A; Figueiredo P; Lintinen K; Balasubramanian V; Airaksinen AJ; Kostiainen MA; Santos HA; Sarparanta M, J Biomed Mater Res A 2020, 108 (3), 770–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].De France KJ; Chan KJ; Cranston ED; Hoare T, Biomacromolecules 2016, 17 (2), 649–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sunasee R; Hemraz UD; Ckless K, Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2016, 13 (9), 1243–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sarparanta M; Pourat J; Carnazza KE; Tang J; Paknejad N; Reiner T; Kostiainen MA; Lewis JS, Nucl Med Biol 2020, 80–81, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tong X; Wang Z; Sun X; Song J; Jacobson O; Niu G; Kiesewetter DO; Chen X, Theranostics 2016, 6 (12), 2039–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Eyley S; Thielemans W, Nanoscale 2014, 6 (14), 7764–7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fleischer CC; Payne CK, J Phys Chem B 2012, 116 (30), 8901–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Albanese A; Tang PS; Chan WC, Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2012, 14, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ganz T; Nemeth E, Biochim Biophys Acta 2006, 1763 (7), 690–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Letchford; Jackson; Wasserman B; Ye; Hamad W; Burt H, International Journal of Nanomedicine 2011, 10.2147/ijn.S16749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Akhlaghi SP; Berry RC; Tam KC, Cellulose 2013, 20 (4), 1747–1764. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Barbosa AM; Robles E; Ribeiro JS; Lund RG; Carreno NLV; Labidi J, Materials (Basel) 2016, 9 (12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Behzadi S; Serpooshan V; Tao W; Hamaly MA; Alkawareek MY; Dreaden EC; Brown D; Alkilany AM; Farokhzad OC; Mahmoudi M, Chem Soc Rev 2017, 46 (14), 4218–4244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhao J; Stenzel MH, Polymer Chemistry 2018, 9 (3), 259–272. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Franken NA; Rodermond HM; Stap J; Haveman J; van Bree C, Nat Protoc 2006, 1 (5), 2315–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wang X; Zhang H; Chen X, Cancer Drug Resistance 2019, 10.20517/cdr.2019.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Maeda J; Froning CE; Brents CA; Rose BJ; Thamm DH; Kato TA, PLoS One 2016, 11 (6), e0156689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Meeth K; Wang JX; Micevic G; Damsky W; Bosenberg MW, Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research 2016, 29 (5), 590–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Decuzzi P; Godin B; Tanaka T; Lee SY; Chiappini C; Liu X; Ferrari M, J Control Release 2010, 141 (3), 320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Shukla S; Eber FJ; Nagarajan AS; DiFranco NA; Schmidt N; Wen AM; Eiben S; Twyman RM; Wege C; Steinmetz NF, Adv Healthc Mater 2015, 4 (6), 874–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Neyrinck K; Breuls N; Holvoet B; Oosterlinck W; Wolfs E; Vanbilloen H; Gheysens O; Duelen R; Gsell W; Lambrichts I; Himmelreich U; Verfaillie CM; Sampaolesi M; Deroose CM, Theranostics 2018, 8 (10), 2799–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Keinanen O; Brennan JM; Membreno R; Fung K; Gangangari K; Dayts EJ; Williams CJ; Zeglis BM, Mol Pharm 2019, 16 (10), 4416–4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Pirooznia N; Abdi K; Beiki D; Emami F; Arab SS; Sabzevari O; Soltani-Gooshkhaneh S, Bioorganic Chemistry 2020, 102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Poty S; Mandleywala K; O’Neill E; Knight JC; Cornelissen B; Lewis JS, Theranostics 2020, 10 (13), 5802–5814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bussani R; De-Giorgio F; Abbate A; Silvestri F, J Clin Pathol 2007, 60 (1), 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Cui Y; Urschel JD; Petrelli NJ, Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001, 49 (1), 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hecht M; Zimmer L; Loquai C; Weishaupt C; Gutzmer R; Schuster B; Gleisner S; Schulze B; Goldinger SM; Berking C; Forschner A; Clemens P; Grabenbauer G; Muller-Brenne T; Bauch J; Eich HT; Grabbe S; Schadendorf D; Schuler G; Keikavoussi P; Semrau S; Fietkau R; Distel LV; Heinzerling L, Ann Oncol 2015, 26 (6), 1238–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lu P; Hsieh Y-L, Carbohydrate Polymers 2010, 82 (2), 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Sun B; Zhang M; Hou Q; Liu R; Wu T; Si C, Cellulose 2015, 23 (1), 439–450. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Amreddy N; Muralidharan R; Babu A; Mehta M; Johnson EV; Zhao YD; Munshi A; Ramesh R, Int J Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 6773–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ullman-Cullere MH; Foltz CJ, Lab Anim Sci 1999, 49 (3), 319–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.