Graphical abstract

Keywords: Functional epitranscriptome, RNA modification, Bioinformatics approaches, Recent advances, Future perspective

Abstract

RNA modifications, in particular N6-methyladenosine (m6A), participate in every stages of RNA metabolism and play diverse roles in essential biological processes and disease pathogenesis. Thanks to the advances in sequencing technology, tens of thousands of RNA modification sites can be identified in a typical high-throughput experiment; however, it remains a major challenge to decipher the functional relevance of these sites, such as, affecting alternative splicing, regulation circuit in essential biological processes or association to diseases. As the focus of RNA epigenetics gradually shifts from site discovery to functional studies, we review here recent progress in functional annotation and prediction of RNA modification sites from a bioinformatics perspective. The review covers naïve annotation with associated biological events, e.g., single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), RNA binding protein (RBP) and alternative splicing, prediction of key sites and their regulatory functions, inference of disease association, and mining the diagnosis and prognosis value of RNA modification regulators. We further discussed the limitations of existing approaches and some future perspectives.

1. Introduction

RNA modifications, in particular N6-methyladenosine (m6A), post-transcriptionally regulate many aspects of RNA metabolism, including its degradation [1], [2], protein translation [3], [4] and alternative splicing [5], [6]. More than 170 kinds of RNA modifications [7] have been identified on mRNA, tRNAs, rRNAs, lncRNAs and other noncoding RNAs [8], [9], and most of them are methylation modifications. The functional significance of RNA modifications was not fully aware of until the discovery of human fat mass gene FTO as an m6A demethylase [10] and the invention of transcriptome-wide m6A profiling technology, MeRIP-seq (or m6A-seq) [11], [12], which identified m6A in more than 25% human mRNA and indicates the influence of m6A in gene expression. Since then, the study of whole transcriptome RNA modifications became blooming and known as the 'epitranscriptome' [13]. Thanks to the advances of high-throughput techniques, whole-transcriptome-wide maps of at least 12 modifications were profiled, including N6-methyladenosine (m6A), Pseudouridine (ψ), N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C), N1-methyladenosine (m1A), N7-methylguanosine (m7G), 2′O-methylations (Cm, Am, Gm, Um), 5-methylcytidine (m5C), 5-hydroxymethylcytidine Cytidine (hm5C) and Inosine (I) [8], [9].

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant and the most well studied chemical modification on eukaryotic mRNA [14], which has been known to play important roles in gene expression regulation [15] and translation mediation [3], [16]. The dynamic RNA m6A methylation can be added by m6A methyltransferases (writers), removed by demethylases (erasers) and recognized by corresponding RNA binding proteins (readers) [17]. The methyltransferase compound mainly consists of METTL3, METTL14 and WTAP, as well as later discovered regulatory components KIAA1429, RBM15 and RBM15B; the demethylases mainly include FTO [18] and ALKBH5 [19]. The reader protein complexes, which can specifically recognize m6A, mainly include YTH family proteins (YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1) , transcription initiation complex eIF3 [3], ribonucleoprotein HNRNPA2B1 [20] and HNRNPC [21]. The dynamic m6A modification mediated by these regulators has been shown to play significant roles in many vital biological processes, e.g., embryonic development [22], stem cell differentiation [23], [24], [25], cell death and cell proliferation [26], circadian clock cycle [27] and viral life cycle [28], [29]. The m6A perturbations also contribute to pathogenesis of cancers [26], [30], [31], [32], viral infection [33] and other human diseases [34], [35], [36]. Besides m6A, 5-methylcytosine (m5C) is another wide spread RNA modification, which is primarily mediated by RNA methyltransferase DNMT2 and NSUN2 along with its homologs [37], [38], [39] and its reader proteins YBX1 [40] and ALYREF [39]. m5C can influence mRNA stability [40], [41] and regulate viral gene expression [6]. Adenosine-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing, as the main form of RNA editing in mammals [42], is mediated by the members of the adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) enzyme family. A-to-I RNA editing plays key role in innate immunity [43], [44] and contributes to the pathogenesis of some diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [45] and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [46]. N7-methylguanosine (m7G) is the most ubiquitous RNA cap modification [47], which also plays significant roles in RNA metabolism including transcription, mRNA splicing and translation [48], [49], [50]. We briefly summarized here some well-studied modifications. Please refer to recent reviews [8], [9] for more comprehensive background of RNA modifications.

With recent development in high-throughput sequencing techniques and bioinformatics approaches, it becomes increasingly easy to obtain the locations of RNA modifications. Millions of RNA modification sites have been identified in more than 10 species [51], [52], [53], [54], [7], posing a major challenge in charting the 'functional epitranscriptome', i.e., identifying the functional components out of tens of thousands of RNA modification sites and elucidating their functions and disease association. As the focus of RNA epigenetics gradually shifts from site discovery to functional studies, we review here some recently developments in computational approaches for deciphering the functional relevance of RNA modification sites.

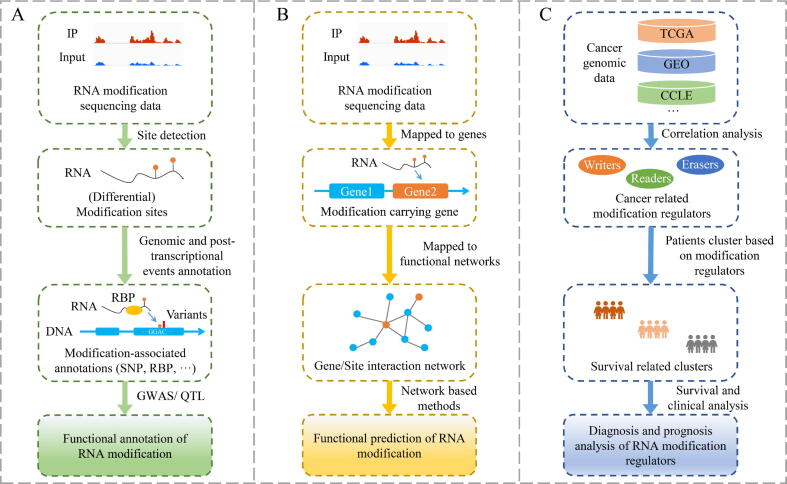

The very first step of functional epitranscriptome analysis is to identify the RNA modification sites. Then, there exist two paths to annotate the functions of RNA modification sites: 1) The naïve idea is to annotate the associated functional event according to their proximity to the RNA modification sites on the genome, e.g., miRNA target sites located within 100 bp of the RNA modification sites, which may be potentially mediated by the modification (see Fig. 1A). 2) The more sophisticated annotation approach is to identify key sites and genes based on the functional annotations and the interactions of the genes modified at RNA level, and then further predict RNA modification-mediated functional circuits and associated diseases using complex network theories (see Fig. 1B). Moreover, for the most prevalent RNA methylation, some studies have predicted the diagnosis- and prognosis-related methylation regulators, which start from genetic mutations and expression dysregulation of m6A regulators in cancers via integrated analysis and predict the potential diagnostic and prognostic methylation markers via survival and clinical analysis (see Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Functional annotation and prediction of the epitranscriptome. A. Functional annotation of RNA modification; B. Functional prediction of RNA modification; C. Diagnosis and prognosis analysis of RNA modification regulators.

2. Identification of RNA modification site

The first step of functional epitranscriptome prediction is to identify modification sites, either directly from high-throughput sequencing data or by using sequenced-based computational prediction tools. There exist a large number of sequencing technologies and software tools that can serve this purpose, including but not limited to those based on reverse transcription signature [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], bisulfite treatment [39], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], antibody [11], [12] and the primary sequences of RNA molecules [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84]. In the following paragraph, we cover primarily two most widely used approaches, including site detection from MeRIP-Seq data and sequence-based in silico prediction methods.

2.1. Site detection from MeRIP-Seq data

MeRIP-Seq (or m6A-seq) [11], [85] is the first and the most widely adopted approach for profiling transcriptome-wide distribution of m6A methylation. With MeRIP-seq, the m6A sites can be identified in a process called “peak calling”, in which the regions enriched with m6A signals (shown as peaks in tag density) are identified by comparing to the input control samples. A number of peak calling tools have been developed for this analysis. MACS [86] has been a popular peak calling tool for ChIP-Seq data and is also applied to analyze MeRIP-Seq data [87]. However, MACS was developed for DNA-Seq, which failed to address some intrinsic properties of MeRIP-Seq, such as, the impact of differential RNA expression, alternative splicing [88]. exomePeak is another popular peak calling tools designed specifically for epitranscriptome peak calling of MeRIP-Seq data [89]. exomePeak supports both site detection and differential methylation analysis, but it doesn’t model the variance among biological replicates. MeTPeak [90] captures the variances by introducing a hierarchical layer of Beta variables and characterizes the reads dependency across a site using a Hidden Markov model.

MACS2, exomePeak and MeTPeak have been widely used to detect m6A peaks from MeRIP-seq data. Developing for DNA-Seq data, MACS2 can detect peaks located in intron and none gene region, while it failed to address some intrinsic properties of MeRIP-Seq data. exomePeak and MeTPeak are specifically designed for epitranscriptome peak calling of MeRIP-Seq data. MeTPeak outperforms exomePeak in robustness against data variance and can detect less enriched peaks [90] and exomePeak achieves better motif enrichment than MeTPeak in some cases [91]. Recently, an updated version of exomePeak has been released officially on Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/exomePeak2.html), which corrects the GC content bias generated by PCR amplification during the library preparation, a common bias among MeRIP-Seq samples. exomePeak2 should be another promising peak calling tool for MeRIP-Seq data.

2.2. Sequence-based in silico prediction methods

By directly learning the RNA modification sites reported from high-throughput sequencing approaches, a large number of prediction models have been established for the computational identification of RNA modification sites from the primary sequences of the RNA molecule as well as by taking advantage of other information [71], [92], [93]. Thanks to the development of sequencing technology such as miCLIP and PA-m6A-seq for m6A, it becomes possible to train m6A site prediction models using machine learning approaches, which extract features from the primary sequences centered around the m6A sites to predict the probability of another nucleotide being a methylation site or not. The sequence features mainly contain nucleotide chemical and physiochemical property, K-mer frequency, nucleotide encoding (including one-hot, spectrum encoding, word embedding, Gene2vec, et.al), and various genomic features (including nucleotide position, i.e., the relative position on 3′UTR, 5′UTR and whole transcript, the length of the transcript region containing the modification site, the evolutionary conservation score, et.al). The adopted machine learning algorithms may range from support vector machine, random forest, XGBoost to more advanced deep learning models such as CNN, LSTM and GRU. For example, iRNA-Methyl [94] extracted “pseudo dinucleotide composition” feature where three RNA physiochemical properties were incorporated and trained a SVM model; SRAMP [68] encoded the RNA and DNA sequence using one-hot binary encoding, spectrum encoding and K-nearest neighbor encoding (KNN encoding), and trained 10 RF models using balanced training dataset; DeepM6ASeq [95] encoded the nucleotide using one-hot and trained a CNN + BLSTM model; WHISTLE extracted the most comprehensive features including nucleotide chemical property and 35 additional genomic features, and achieved state-of-the-art performance with SVM classifier. These approaches consider only the sequence features while ignore the methylation levels under specific context. Considering this, Deep-m6A [96] was proposed to predict context-specific m6A sites using a CNN model which encode the RNA sequence together with context-specific MeRIP-Seq reads count. Song et al. has developed pseudouridine site identification and functional annotation webserver (named PIANO), which trained a high-accuracy predictor that takes input of both conventional sequence features and 42 additional genomic features [97].

2.3. Differential methylation analysis from MeRIP-Seq data

Differential methylation analysis is aimed to detect the dynamics of epitranscriptome in a case-control study. Since these methylation sites are differentially between two biological conditions, they are more likely to be functionally related to the perturbation factor of the samples, which can be disease association or responses to a particular treatment of samples. A number of computational approaches have been developed to identify differential methylation sites from MeRIP-Seq data by comparing samples under two different biological conditions based on different assumption of reads count distribution and statistical models. exomePeak [89] takes the hypothesis that read counts arising from a particular genomic region follows Poisson distributions and adopts a rescaled version of Fisher’s exact test to detect differential methylation peaks. exomePeak2 uses a generalized linear model to handle the over-dispersion of reads count and GC content bias. MeTDiff [98] models biological variation with beta-binomial model and applies a likelihood ratio test to test differential methylation peaks. DRME [99] and QNB [100] both adopt negative binomial distributions to model the reads count fall into the methylation region. DRME considers the variance is smooth function of the reads abundance, while QNB assumes it also depends on the percentage of methylation. RADAR [101] models the reads count distribution using a Poisson random effect model and adopts generalized linear model framework to detect differential methylation peaks. Limited to the resolution of MeRIP-Seq, these approaches can only identify differential methylation regions of 50–100 bps. To infer the real altered methylation sites, DMDeep-m6A [102] was proposed to predict differential methylation sites at single-base resolution from MeRIP-Seq data. Moreover, to identify RNA editing sites, RNA-editing tests (REDITs) was developed based on a suite of tests that employ beta-binomial models [103].

In general, different approaches behave differently on the same dataset, while the top differential peaks are often consistent. This is adopted by DEQ [104], which believes the consensus result of DESeq2 GLM, edgeR GLM and QNB should be real differential methylation peaks. In this way, the detected differential peaks are supposed to have lower false positive rate meanwhile lose much sensitivity. exomePeak has been widely used for differential m6A peak calling with high sensitivity. MeTDiff, DRME and QNB aim to detect more accurate differential peaks when sample size is small and have achieved lower false positive rate than exomePeak, while losing some sensitivities for more rigorous statistical test. RADAR can achieve lower false positive rate and higher sensitivity when the replication sample size is greater than 6 (not available for most published MeRIP-Seq data) and when the available samples are no more than 2, RADA gets similar false positive rate but lower sensitivity comparing with exomePeak [101]. Generally, researchers can choose different approaches based on their requirement and MeRIP-Seq sample size. They may use exomePeak when a high sensitivity is required and there are some subsequential strategies to control the false positive rate; MeTDiff, DRME or QNB is suitable when less differential peaks with relatively higher degree of differential methylation are required; RADAR performs better when there are more replication samples; and DMDeep-m6A works well when the inference of single-base differential methylation sites from MeRIP-seq data is required.

Recently, some longitudinal or time course MeRIP-seq datasets have been produced to depict the regulation process of m6A methylation during different context, such as virus infect and cell differentiation process [105]. It is necessary to develop some approaches to reveal whether and how the methylation levels are changed in different time point and whether the m6A regulated genes' expression could be changed according to contexts. Generalized linear mixed model is a popular model to analyze variance in gene expression for time-course RNA-seq data. However, limited to the small sample size of MeRIP-seq data, the methods for RNA-seq data can’t be directly applied for MeRIP-seq data. Then, it is necessary to develop new methods to solve the small sample issue for time-course, longitudinal or clustered MeRIP-seq data.

3. Functional annotation of RNA methylation sites

3.1. Distance-based functional annotation of RNA methylation sites

The most straightforward and also the simplest way to predict the functional relevance of an RNA modification site is to considering the functional events closely next to it (usually within round 100 bp distance in the genome). Conceivably, closely adjacent biological events are likely to interact with each other or functionally related. Most popular databases and annotation tools support this type of naïve annotation for RNA modification. We summarize in Table 1 these type of annotations related to chemical description of the modifications (Chemical Description), genomic features near the modification sites (Genomic Features), visualization of modification sites in a genome browser (Genome Browser), GO and signaling pathway enrichment of modification sites carrying genes (GO/Pathway), epigenomic modifications around the RNA modification sites (Epigenomic Data), post-transcriptional regulations (Post-Transcription) including RNA binding protein (RBP) binding (RBP), micro RNA targeting (miRNA) and alternative splicing (Splicing), genetic mutations such as SNP next to the modification sites (SNP), and diseases associations (Disease).

Table 1.

Summary of naïve annotation of RNA modification provided from existing databases and web tools.

| Database/Tools | # of Modifications | Chemical Description | Genomic Features | Genome Browser | GO/Pathway | Epigenomic data | Post-Transcription |

SNP | Disease | Last update | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBP | miRNA | Splicing | |||||||||||

| RNAMDB | 109 | √ | 2012 | [106] | |||||||||

| MODOMICS | 172 | √ | 2017 | [7] | |||||||||

| RMBase | >100 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2017 | [53] | ||||

| MeT-DB | 1 (m6A) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2017 | [54] | |||||

| m6AVar | 1 (m6A) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2018 | [107] | |||

| CVm6A | 1 (m6A) | √ | √ | √ | 2019 | [108] | |||||||

| m6A-Atlas | 1 (m6A) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2020 | [51] | ||

| REPIC | 1 (m6A) | √ | √ | √ | 2020 | [91] | |||||||

| M6A2Target | 1 (m6A) | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2020 | [109] | ||||||

| M7GHub | 1 (m7G) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2020 | [74] | |||

| RADAR | 1 (A-to-I) | √ | √ | √ | 2014 | [110] | |||||||

| REDIportal | 1 (A-to-I) | √ | √ | √ | 2017 | [111] | |||||||

| RCAS | NA (Tool) | √ | √ | 2017 | [112] | ||||||||

| RNAmod | NA (Tool) | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2019 | [113] | ||||||

RNAMDB [106], MODOMICS [7] and RMBase [53] are databases that collected multiple RNA modifications. RNAMDB collected basic description of 109 RNA modifications, including chemical structure of the nucleoside, common chemical name, symbol, elemental composition, et.al. MODOMICS has collected currently the most comprehensive RNA modification pathway sources. It has collected 172 RNA modifications and provides comprehensive information concerning the chemical structures, biosynthetic pathways, the location in RNA sequences of RNA modifications, and RNA-modifying enzymes. RMBase is currently the most comprehensive database for RNA modification sites, which collected more than 100 RNA modifications and provides epitranscriptome sequencing data of different modifications on RNAs, their relationships with microRNA binding events, disease-related SNPs and RNA-binding proteins (RBP), and the visualization of this information in a genome browser.

MeT-DB [54], REPIC [91], CVm6A [108], M6A2Target [109], m6Avar [107] and m6A-Atlas [51] are databases for m6A RNA methylation. MeT-DB [54] is the first database for transcriptome m6A modification, which collected context-specific m6A sites and annotated the target sites of m6A readers, writers and erasers as well as RBP, miRNA target and splicing sites. Moreover, MeT-DB provides visualization and functional prediction tools including GuitarPlot [114] and m6A-Driver [115] for investigating the distribution and functions of m6A methyltranscriptome. MeT-DB v2.0 provided a wealth of information related to m6A, which makes it a valuable resource for researchers to understand the biological mechanisms and functions of m6A [116]. REPIC [91] records more than 10 million m6A peaks from 11 species. It integrated 1418 histone ChIP-seq and 118 DNase-seq data tracks from the ENCODE project to visualize m6A sites, histone modification sites, and chromatin accessibility regions in the genome browser. CVm6A [108] was aimed to visualize and explore global m6A patterns across cell lines. It identified 340,950 and 179,201 m6A peaks from public MeRIP-Seq and m6A-CLIP-Seq datasets on 23 human and eight mouse cell lines, respectively, and then mapped them in different subcellular components and gene regions. For human, 190,050 and 150,900 peaks were identified in cancer and non-cancer cells, respectively, which may predict putative associations between m6A and cancer pathology.

M6A2Target [109] has collected the target gene of writers, erasers and readers of m6A modification. M6A2Target contains both 'Validated Targets' which were validated by low-throughput experiments of human and mouse and 'Potential Targets' which were evaluated by high-throughput experiments, such as CLIP-Seq, RIP-seq and ChIP-seq. It also provides the genome browser of m6A sites and the 'Binding' (including protein-RNA, protein-DNA and protein–protein binding) and 'Perturbation' (including changes of gene expression, m6A level, translation efficiency and alternative splicing) information of m6A targets.

m6AVar [107] is the first database of m6A-assocoated genetic mutations (including SNP from dbSNP and cancer somatic mutations from TCGA), which may potentially destroy m6A modification. Starting from m6A-assocoated mutations, m6AVar provides disease related m6A-associated variants from GWAS and ClinVar. It also provides various information related to post-transcriptional regulation such as splicing sites, RNA binding protein and miRNA targeting, which may be affected by m6A-associated variants.

m6A-Atlas [51] is the first quantitative knowledgebase of m6A methylation, which contains annotation of 442,162 reliable m6A sites reported from base-resolution technology together with their methylation level under various experimental conditions. It also provides the putative GO biological functions of individual m6A sites and the annotation of RBP, miRNA binding, alternative splicing and genetic mutation sites next to m6A sites and visualize them in a genome browser. Moreover, m6A-Atlas also provides m6A-related disease information inferred from disease-associated genetic mutations that can directly destroy m6A sequence motifs.

M7GHub [74] is a database of m7G methylation, which consists of 2 sub-databases and 2 web tools: 1) m7GDB, a database which collected 44,058 experimentally-validated internal mRNA m7G sites; 2) m7GFinder, a web server to predict m7G sites from sequences; 3) m7GSNPer, a web server to evaluate whether a genetic mutation can alter m7G RNA methylation; and 4) m7GDiseaseDB, a database which collected disease-associated genetic variants that may lead to the gain or loss of an internal m7G site.

RADAR [110] and REDIportal [111] are databases for A-to-I RNA editing. RADAR [110] is a rigorously annotated database of A-to-I RNA editing, which includes a comprehensive collection of A-to-I RNA editing sites identified in humans, mice and flies, together with extensive manually curated annotations for each editing site. The annotation includes genomic features (strand, associated gene, coding sequence, untranslated region, intron, associated repetitive element, et.al) and annotation of overlapping gene annotations, genomic nucleotide conservation, overlapping SNP database entries and overlapping repetitive elements that can be visualized in UCSC genome browser. REDIportal contains the largest and comprehensive collection of RNA editing in humans and mice including more than 4.5 million of A-to-I events detected in 55 body sites from thousands of RNAseq experiments. REDIportal embeds RADAR database and designed its own browser (JBrowse) that show A-to-I changes and the neighboring annotations in user defined genomic context. For each RNA editing site, REDIportal provide different info such as: 1) genomic features, including the genomic position, the reference and edited nucleotide, the strand, the editing location, the gene symbol according to Gencode v19 and the genic region; 2) editing level, including the number of edited samples, the potential amino acid change, the PhastCons conservation score across 46 organisms and a flag indicating in which database (ATLAS [117], RADAR [110] or DARNED [118]) is reported; and 3) neighboring annotations, including the dbSNP accession and the repeated element.

RNAmod [113] is an integrated webserver to annotate and visualize mRNA modifications, especially for m6A. It provides the distributions, the GO and signaling pathway enrichment and the genome browser of the input modification sites and their neighboring RBPs.

RCAS [112] was developed to ease the process of creating gene-centric annotations and analysis for the genomic regions of interest obtained from various RNA-based omics technologies. The RCAS R package and webserver can provide summary of genomic annotations, coverage profiles of query regions, motif analysis, GO term analysis and Gene set enrichment analysis.

ANNOVAR [119] and SnpEff [120] were developed for functional annotation of variants and can be used to achieve functional characterization of mutations arising due to A-to-I editing especially in the coding sequence of genes. The PIANO webserver [97] can systematically annotate the predicted pseudouridine sites with post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms (miRNA-targets, RBP-binding regions, and splicing sites), which can help explore the potential machinery of pseudouridine.

RNAMDB, MODOMICS and RMBase were developed for multi kinds of RNA modifications, where RMBase is more functional relevance based on its comprehensive integration of microRNA binding events, disease-related SNPs and RBPs. MeT-DB, REPIC, CVm6A, M6A2Target, m6Avar and m6A-Atlas concentrated on m6A only, where MeT-DB is the first database; M6A2Target concentrated more in m6A binding proteins; REPIC integrated the epigenetic information; and m6Avar and m6A-Atlas annotated more in disease associated m6A-SNP co-occurrence. Moreover, m6AVar is the first database of m6A-assocoated genetic mutations and m6A-Atlas annotated the putative GO biological functions of individual m6A sites. M7GHub is a comprehensive database specific for m7G methylation. RADAR and REDIportal were both developed for A-to-I editing, where REDIportal embeds RADAR database.

3.2. Annotating with genetic variants that may affect RNA modification status

Besides directly annotating RNA modification sites, enormous efforts have been made to annotate the genetic variants that may affects RNA methylation status. It is well established that many kinds of cancers are evoked by different kinds of cancer-causing variants of different genes and dysregulation of m6A has been implicated in cancer progression [121], [122]. Therefore, it is important to explore the effect of variants on m6A modification and understand how these variations influence the biological function during cancer process and disease.

To solve this issue, some researchers are devoted to uncover how the gene variants (e.g. SNP) influence the status of m6A modification and identify the potential roles of m6A-associated variants in various RNA-related processes and diseases. m6ASNP is the first tool that developed to predict whether the methylation status of an m6A site can altered by genetic variants close to it [123]. The m6ASNP collected two kinds of datasets: 1) SNP from dbSNP for human and mouse [124]; and 2) m6A modification sites from two miCLIP-seq studies [125], [126], two PA-m6A-seq experiments [127] and 244 MeRIP-seq samples. m6ASNP firstly trained a random forest (RF) model to predict m6A site in single-base resolution using the primary RNA sequence and secondary structure features. Based on the RF model, m6ASNP mapped the genetic variants to known methylated transcript and checked whether the methylation status was changed by their neighboring sequence variants comparing to the wild-type transcript. If an m6A site occurred in the wild-type transcript and disrupted in the mutant transcript, m6ASNP defined it as an m6A-associated loss variant and vice versa. m6ASNP constructed three confidence levels of m6A-associated variants annotation. The high-confidence-level annotation contains m6A sites derived from miCLIP-seq and PA-m6A-seq dataset; the medium-confidence-level annotation contains m6A sites obtained from MeRIP-seq detected methylation peak where the DRACH motifs were significantly altered by SNP; the low-confidence-level annotation contains m6A sites that predicted by m6ASNP whole transcriptome widely. To further mine the function of m6A-associated variants, m6ASNP annotated the m6A-associated variants by their neighboring RBP sites [128], miRNA target sites [128] and canonical splicing sites, and conducted GWAS analysis to infer disease-association for m6A-associated SNPs [129]. Using the same analysis pipeline defined in m6ASNP, m6AVar [107] was developed as the first comprehensive database of m6A-associated variants. m6AVar is a powerful resource for investigating the relationship between m6A-associated variants and diseases.

RMVar [130] was developed to extend the analysis to 9 kinds of RNA modifications [130]. m6A-Atlas is another database of m6A-associated variants, which can be used to further detect the potential pathogenesis of m6A sites inferred from disease-associated genetic mutations that directly destroy the m6A forming DRACH motif [51]. m6A-Atlas is a comprehensive knowledgebase for high-confidence collection of m6A sites covering seven species and including virus infection epitranscriptomes. Similar to m6AVar, m6A-Atlas also annotated the potential involvement of m6A sites in pathogenesis by integrating GWAS information. Similar to RMVar, RMDisease [131] collected eight types of RNA modifications and their disease-associated variants. Importantly, RMDisease integrated multiple algorithms and used more information and provides quantitatively the impact of the genetic variants on RNA modification.

The above researches mainly study the influence of SNP on RNA modification based on the disturbed modification sites nearby SNP using RNA sequence analysis. Moreover, some researchers tried to build the relationship between SNPs and methylation level of m6A sites, and further tested cis-associations between methylation peaks and SNPs within specific region. Zhang et al have applied a linear model implemented in FastQTL [132] to detect the associations between SNPs and m6A sites within 100 kb from m6A-seq data in lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from 60 Yoruba (YRI) individuals [133]. This pipeline is similar to eQTLs or sQTLs and they defined the significant associations as m6A QTL. To account for multiple genetic variants tested for each peak, a permutation strategy adopted by FastQTL software [132] was performed. m6A QTLs are found to be largely independent of eQTLs and enriched with binding sites of RBPs [134], RNA structure-changing variants [135] and transcriptional features. And m6A QTLs are more likely to be other kind of QTLs than random SNP-gene pairs, suggesting functional associations between m6A and other molecular phenotypes based on five downstream traits analysis: mRNA expression; ribosome binding; protein level; mRNA decay rate; and alternative polyadenylation (APA). Similar with the previous m6A-associated SNP studies, m6A QTLs are found to contribute to the heritability of various immune and blood-related traits by GWAS analysis. The TWAS/FUSION [136], [137] was also applied treating m6A as a molecular-level trait to determine the correlations of m6A levels and specific phenotype.

4. Advanced approaches for functional prediction

RNA m6A methylation is reported to mediate mRNA turn-over and translational efficiency of genes such as MYC [138], TGFb [139], and FOXM1 [140] to regulate pathways such as cell apoptosis, proliferation, migration and self-renewal in both normal and disease conditions [141]. Therefore, the behaviors of functional m6A sites and their carrying genes are supposed orchestrated in complex networks. Based on this hypothesis, some computational methods in particular network-based approaches have been developed to predict the key RNA methylation sites and their mediated functions and disease-association (Table 2). The approaches were summarized based on the modification type it is developed for (Modification Type), whether it is developed for RNA methylation function prediction (Function Prediction) or disease association prediction (Disease Association) and whether the predicted results are for methylation sites (Site-based) or their carrying genes (Gene-based).

Table 2.

Summary of advanced approaches for functional prediction of epitranscriptome.

| Approaches | Modification type | Function prediction | Disease Association | Gene- based | Site- based | Last | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m6A-Driver | m6A | √ | √ | 2016 | [115] | ||

| Hot-m6A | m6A | √ | √ | √ | 2018 | [96] | |

| FunDMDeep-m6A | m6A | √ | √ | 2019 | [102] | ||

| Funm6AViewer | m6A | √ | √ | 2021 | [142] | ||

| m6Acomet | m6A | √ | √ | 2019 | [143] | ||

| ConsRM | m6A | √ | √ | 2021 | [144] | ||

| DRUM | m6A | √ | √ | 2019 | [145] | ||

| HN-CNN | m7G | √ | √ | 2021 | [146] | ||

| m7GDisAI | m7G | √ | √ | 2021 | [147] | ||

| Lin et al. | m6A | √ | √ | 2020 | [148] | ||

| Qiu et al. | m6A | √ | √ | 2020 | [149] |

4.1. Prediction of RNA methylation-mediated functions

m6A-Driver is the first network-based computational algorithm for predicting m6A-driven genes and associated networks, whose functional interactions are likely to be actively modulated by m6A methylation under a specific condition with respect to a reference condition (e.g., disease vs. normal, differentiated cells vs. stem cells or gene knockdown cells vs. wild type cells) [115]. m6A-Driver integrates the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and the predicted differential methylation sites from MeRIP-Seq data using a Random Walk with Restart (RWR) algorithm, and then builds a consensus m6A-driven network of m6A-driven genes. The m6A-driven genes refer to genes whose mRNAs harbor differential RNA methylation sites, thus may be under dynamic epitranscriptomic regulation, and be functionally significant to the biological contexts of interest. m6A-driven genes were identified in four steps by the m6A-Driver algorithm: 1) replicate-specific prediction of differential methylation carrying genes using exomePeak; 2) replicate-specific prediction of candidate differential methylation site carrying genes with RWR algorithm; 3) topological and functional significance-based evaluation of the candidate differential methylation carrying genes; 4) construction of a consensus m6A-driven gene network from edges across all replicates. Starting from MeRIP-Seq data, m6A-Driver can predict functional methylation sites carrying genes and their mediated functional circuit. A major limitation of m6A-Driver method is that, it only models the functional interactions between differential methylation carrying genes but ignores the functional interaction of differential methylation carrying genes with known signaling pathways and their up- and down-stream genes in the pathways.

The FunDMDeep-m6A method was proposed to help reveal the dynamics of m6A level under a specific context and identify the genes, functions and pathways mediated by the dynamic m6A methylation using data from MeRIP-seq [102]. FunDMDeep-m6A develops, at the first step, DMDeep-m6A to identify differential m6A methylation sites from MeRIP-Seq data at a single-base resolution, and then identifies and prioritizes functional differential methylation carrying genes by combing differential methylation with differential expression analysis using a network-based method. A novel m6A-signaling bridge (MSB) score was devised to quantify the functional significance of differential methylated genes by assessing functional interaction of these genes with their signaling pathways via a heat diffusion process in PPI networks. FunDMDeep-m6A can identify more context-specific and functionally significant functional methylation genes than m6A-Driver. Taking FunDMDeep-m6A as prediction engine, Funm6AViewer webserver and R package were developed to prioritize context-specific functional m6A-carrying genes, characterize and visualize the differential m6A sites, and construct and functionally interpretate the gene interaction networks mediated by RNA methylation, including its functionality, relation to gene expression, and network topology [142].

Different from gene-based network algorithms, m6Acomet constructed a network of co-methylated m6A sites from 109 experimental conditions and predict biological functions of individual m6A sites based on the significantly enrichment GO functions of its neighboring sites carrying genes [143]. The co-methylation network was constructed based on the Pearson’s correlation of methylation level of m6A sites and the co-methylated sites in the network are speculated to share some common regulators at the epitranscriptome layer and have related biological functions. The GO prediction for individual m6A site was achieved by mapping its neighboring sites to genes and applying GO enrichment analysis for their carrying genes, and thus can only predict GO functions of specific m6A site instead of the entire gene. m6A-Atlas adopted the same analysis and collected the GO function annotation of each m6A sites in the database [51]. Song et.al. constructed a centralized platform, ConsRM, to achieve conservation analysis and functional prioritization of individual RNA methylation sites [144].

4.2. Inference of disease-association

To conduct a comprehensive prediction of m6A mediated functions and associated diseases, Zhang et al proposed a pipeline that carries out global analysis of m6A regulated genes using 75 human methylated MeRIP-seq samples curated by MeT-DB V2.0 [54]. The pipeline is mainly consisting of three parts: 1) Deep-m6A, the first deep learning model for detecting condition-specific m6A sites from MeRIP-Seq data with base resolution; 2) Hot-m6A, a new network-based algorithm that prioritizes functional significant m6A genes and their regulated networks; and 3) Random Walk with Restart (RWR) in a heterogeneous gene-disease networks to infer m6A regulated gene-disease associations. Consistent with current researches, Hot-m6A reveals that m6A targets key genes of many important biological processes (e.g., transcription, cell organization and transport, and cell proliferation) and cancer related pathways (e.g., Wnt pathway, Ras signaling, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway). The disease-association analysis prioritized five diseases including leukemia and renal cell carcinoma along with the corresponding m6A regulated marker genes. This pipeline provided new leads for understanding m6A regulatory functions and its roles in disease pathogenesis. However, the analysis was conducted in gene level, and only the m6A site with the highest methylation level of a gene was considered, which may lead to the loss of some information.

To capture the site-specific information, the DRUM method [145] constructed a multi-layered heterogeneous network for prediction m6A site and disease association, in which, the methylation sites and genes were linked via the association of expression and methylation levels, and the genes and diseases were linked according to existing gene-disease association database. Then a RWR approach was adopted to predict associations between individual m6A sites and diseases. Nevertheless, the co-expression network cannot well establish the gene functional interaction module in disease gene prediction problems and straight-forward linking of m6A sites and their carrying genes may not quantify the regulation level of RNA methylation to genes. The HN-CNN method trained a convolutional neural network (CNN) to predict m7G site disease associations [146] and the m7GDisAI predicted the potential disease-associated m7G sites based on a matrix decomposition method on heterogeneous networks of m7G sites and diseases [147].

Another way to investigate m6A clinical relevance is to find functional methylation-associated SNPs using genome-wide association studies in patients. From published GWAS summary statistics through a public database, Lin et al have identified a large number of BMI (body mass index)-associated m6A-SNPs and established an m6A-SNP/gene expression/adiposity triplet, where the SNP located next to the m6A site on 3′UTR of IPO9 gene was predicted to affect the m6A modification site and regulate the expression of the IPO9 gene to participate in the pathogenesis of adiposity [148]. Using GWAS in Parkinson's disease (PD) patients, Qiu et al have investigated potential functional variants of m6A-SNPs [149] and identified 12 m6A-SNPs that were significantly associated with PD risk using expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis and differential gene expression analysis.

4.3. Clustering of epitranscriptome data

Clustering of RNA modification data can discover co-methylation patterns and contributes to explain the specific regulatory mechanisms of RNA modification. Liu et al. have developed the first clustering approach, which adopted K-means, hierarchical clustering (HC), Bayesian factor regression model (BFRM) and nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF) to unveil the co-methylation patterns of m6A MeRIP-Seq datasets collected from 10 different experimental conditions [150]. Chen et al. developed a convenient measurement weighting strategy to tolerate the artifacts of high-throughput sequencing data and improve performance in epitranscriptome module discovery [151]. A weighted Plaid bi-clustering model (FBCwPlaid) [152] and an RNA Expression Weighted Iterative Signature Algorithm (REW-ISA) [153] were also developed to discover the potential functional patterns from MeRIP-seq data of 69,446 methylation sites under 32 experimental conditions. Recently, a biclustering algorithm based on the beta distribution (BDBB) was proposed to mine local co-methylation patterns (LCPs) of m6A epitranscriptome data and BDBB unveiled two functional LCPs from MeRIP-Seq data of 32 experimental conditions from 10 human cell lines [154].

5. Diagnosis and prognosis analysis

Perturbation of m6A regulators including writers, erasers and readers in cancer, has revealed their critical roles in regulating cellular proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis, and metastasis [155], [156], [157], [158] and unveiled the critical insights into the role of m6A regulators in cancer pathogenesis [159]. Starting from methylation regulators, some studies have investigated the diagnostic and prognostic roles of methylation in cancers and some common diseases using correlation and survival analysis from large-scale cancer genomic data, such as those from TCGA or ENCODE.

Kandimalla et al have comprehensively analyzed gene expression profiles of 9770 cancer cell lines and clinical specimens from 13 human cancers [159] to establish RNAMethyPro, a gene expression signature of seven m6A regulators, which robustly predicted patient survival in multiple human cancers. RNAMethyPro was built based on a multivariate Cox regression model, which was trained using the corresponding training dataset for each cancer type. Then, the derived formula, i.e., RNAMethyPro, was subsequently used to calculate the risk scores predictive of overall survival or relapse-free survival. Patients in each cohort were stratified into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups based on the risk scores predicted by RNAMethyPro and the performance of RNAMethyPro is validated by survival analysis, gene set enrichment analysis, ESTIMATE [160] analysis of stromal and immune content and network analysis for different risk groups.

Meanwhile, Li et al have conducted another pan-cancer analysis, which investigated the clinical relevance of m6A regulators across more than 10,000 subjects representing across 33 cancer types [161]. They firstly profiled the widespread genetic and expression alterations to 20 m6A regulators across cancer types; then implemented correlation analysis, showing that the m6A regulators' expression levels are significantly correlated with the activity of cancer hallmark-related pathways; and finally, built survival landscape for 20 m6A regulator in 33 cancers and identified survival-related subgroups of cancer patients based on the global expression pattern of m6A regulators. According to their results, m6A regulators were found to be potentially useful for prognostic stratification, and IGF2BP3 was identified as a potential oncogene across multiple cancer types.

Using similar pipeline, many studies have revealed the diagnostic and prognostic roles of m6A or other methylation (e.g., m1A) regulators in specific cancer including but not limited to hepatocellular carcinoma [162], [163], uveal melanoma [164], prostate cancer [165], gynecological cancers [166], esophageal cancer [167], thyroid carcinoma [168] and renal carcinoma [169]. Moreover, Meng et al have built the m6A-related mRNA signature to predict the prognosis of pancreatic cancer patients [170] and predicted that PAH, ZPLD1, PPFIA3, and TNNT1 genes exhibited an independent prognostic value using correlation and survival analysis. Tu et al have investigated the prognostic value of m6A-related long non-coding RNAs in 646 lower-grade glioma (LGG) samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) datasets [171] using gene co-expression analysis and univariate Cox regression analysis for survival.

6. Conclusion and future perspective

The dynamic RNA modifications, especially m6A, have been identified to play regulatory roles in many essential biological processes, and the dysregulation of their regulators has been shown to mediate the pathogenesis, diagnosis and prognosis of many cancers and other human diseases. In the last decade, the epitranscriptome profiling approaches have been well established for a dozen of RNA modifications, and the epitranscriptome of many species under various biological contexts have bene collected and publically available from existing bioinformatics databases. Nevertheless, the functional epitranscriptome, which consists of the functional modification sites along with their mediated functions and disease association, remains unclear. We have summarized here the current bioinformatics approaches for functional annotation and prediction of RNA modifications, including the prediction of functional RNA modification sites and their hosting genes, along with RNA modification-mediated functions, disease association and diagnosis/prognosis.

Started from the successfully identified RNA modification sites, there are mainly two ways of functional analysis of RNA modifications: 1) the distance-based path that associate various biological events with RNA modification sites based on their proximity on the genome. 2) the omics-based path that predicts functional methylation sites/genes with their mediated functions and associated diseases using complex network-based methods from large-scale omic data.

Existing functional analysis approaches have unveiled partially the landscape of functional epitranscriptome, while there are still some shortages and limitations. The annotation-based approach associates the functions of RNA modification sites to other biological events based on simply the co-localization. There exists certainly a large number of false positive association and the potential regulatory mechanism is not clear. Though some works such as m6Var and m6A-Atlas have defined m6A-associated SNPs as SNPs that can alter m6A methylation sites according to machine learning analysis, it is difficult to validate those predictions directly with experimental data due to the lack of paired epitranscriptome profiles from the wild type and mutated samples.

The network-based approaches directly mapped methylation sites to genes, and then predict their mediated function circuits based on the hypothesis that the closely interacted nodes (module) in a network tends to be regulated by the same regulator or mediate common functions using the complex network theories. The straight-forward mapping of methylation sites to genes presumes the dynamic sites can disturb gene functions but ignores the site-specific regulation mechanism when there exist multiple RNA methylation sites on the same transcript. For m6A methylation, the m6A sites located on 3′UTR and CDS near the stop codon of mRNA are more likely to mediate mRNA stability and degradation, which is correlated with gene expression level, while the m6A sites located on 5′UTR and caps of mRNA are more likely to mediate mRNA translation efficiency, which is correlated with the protein expression level. Different locations and characteristics of methylation sites may lead to different mechanisms and levels of regulation, then it is important to quantify the regulation of methylation sites rather than the whole genes. Some approaches such as FunDMDeep-m6A have simply quantified the regulation level of methylation sites by combing the differential gene expression with differential methylation under specific biological context (e.g., stem cell differentiation), while only the gene expression level is considered with the location information ignored. Conceivably, it may be more convictive if the network-based approach considers the detailed regulatory mechanism of every individual sites in the future.

A perspective way to predict RNA methylation-mediated functions could be mining key genes, whose expression, splicing state or translation efficiency is regulated by RNA methylation under specific context. The primary mode of m6A post-transcriptional regulation is mRNA stability regulation, where YTHDF1-3 selectively bind to m6A sites to promote mRNA decay [172]. The methylation level of specific m6A sites and gene expression may have tightly correlation under specific condition. A common challenge in studying condition-specific m6A regulatory functions is the limited MeRIP-seq replicates. Some efficient approaches such as DESeq2 [173] have been developed to process small samples of RNA-seq data, which can inspire the solution for limited MeRIP-seq replicates. Xiao et al. provided the first transcriptome-wide analysis of splicing changes induced by YTHDC1 knockdown [5] and some researchers also revealed the m6A erasers, such as FTO, could influence RNA alternative splicing [174]. Due to the limited sequencing depth, it is difficult to identify alternative splicing sites from input samples of MeRIP-Seq data, while it is still interesting if the distribution of m6A sites and splicing sites can be compared to find some patterns for further correlation analysis. m6A can affect the efficiency of mRNA translation via m6A-binding protein YTHDF1 or directly recruiting some translation initial factors depending on m6A in specific biological context [3], [175]. The regulation pattern may be different depends on the distribution of m6A sites, the binding of translation factor recruited by m6A readers or writers and different contexts (e.g., cell lines, treated conditions). Some regression or correlation analysis methods can be adopted to uncover the RNA sequence-based or gene-specific m6A regulated translation patterns under specific condition.

Moreover, METTL14- or METTL3-mediated m6A methylation could influence the stability or translation of histone methyltransferase, such as Ezh2 and SETD, which further advances the level of H3K27ac, H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 modification during the cell development [176], [177], [178]. The m6A-mediated histone mark may be context-specific during transcription process. Some specific sequence patterns or histone marker binding motifs may help uncover the relationship between m6A methylation and specific histone mark. Integrated analysis of paired MeRIP-seq and ChIP-seq data for histone markers should contribute to uncovering some interesting m6A-mediated histone mark patterns.

Meanwhile, current diagnosis and prognosis analysis pipelines for RNA methylation are mainly activated by two engines: methylation regulators-powered analysis where the diagnostic and prognostic roles of RNA methylation regulators in cancers are investigated using correlation analysis and survival analysis from large scale cancer genomic data; and methylation-associated SNPs-powered analysis where the diagnostic and prognostic roles of RNA methylation in specific disease are investigated using genome wide association analysis for methylation-associated SNPs. The RNA modification regulators-powered diagnosis and prognosis analysis focused on the genetic mutations and dysregulation in the expression of methylation regulators in cancers from large-scale cancer data. The involvement of big data can surely improve our understanding of the diagnostic and prognostic roles of these regulators; however, the absence of methylation profile data in these studies may lead to missing of further epitranscriptome mechanisms. To date, the value of epitranscriptome profile (rather than the regulators of the epitranscriptome) in diagnostic and prognostic analysis has not been fully explored, which is primary due to the data availability. To the best of our knowledge, none of existing large consortium projects, such as TCGA, has covered the epitranscriptome of patients, which is a major limitation for large-scale and in-depth studies of the pathogenic relevance of epitranscriptome mechanisms.

Additional perspectives for functional annotating RNA modifications may include: (1) Association to virus. Recent studies have unveiled the critical role of RNA modifications during virus infection [179]. Although m6A-Atlas provided the viral epitranscriptome of ten different viruses, it should be interesting to further label host m6A sites that may regulate the fate of endogenous retroviruses [180] or functions during virus infection. (2) Relevance to RNA structure. A number of studies have shown that RNA modifications may affect RNA structure [181], [182], [183], [184], [185]. Permeably, RNA modification sites that can change its overall structure are likely to be functionally critical. However, a systematic labeling of all the RNA modification sites that can modify the structure is yet available. (3) Isoform specificity. Most existing epitranscriptome profiling approaches suffers from an isoform ambiguity problem, i.e., it is unclear whether an RNA modification site is located on a specific isoform transcript when there exist multiple isoform RNAs transcribed from the same DNA coordinate. As a result, isoform specificity of RNA modification is not provided in any of the bioinformatics databases. Labeling isoform belonging clearly provides more detailed information of the RNA modification. Recently, a computational model MetaTX shed some light on this issue from a statistical perspective by taking advantage of the overall distribution pattern of RNA modification [186] and a computational package Episo was also developed to quantify epitranscriptomal RNA m5C at the transcript isoform level [187]. The Nanopore technology provide a parallel experimental solution [188], [189], [190], [191], [192], [193], [194]. (4) Evolutionary conservation of individual RNA modification sites. Conservation has been a very powerful perspective to study the function of protein and DNA sequences. Conceivably, conserved RNA modification sites, i.e., RNA modification occurs on the homologous regions of different species, survived from nature selection, and are thus likely to be functionally important for the organisms. Currently, the conservation information is only available for m6A RNA methylation through the m6A-Atlas [51] database. It should be interesting to further label the conservation status all other RNA modification sites.

Funding

China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [No. 2020M683568 for Song-Yao Zhang]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 61873202 and No. 61473232 for Shao-Wu Zhang, No. 31671373 for Jia Meng].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Song-Yao Zhang: Writing - original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Shao-Wu Zhang: Writing - review & editing, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Teng Zhang: Writing - original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Xiao-Nan Fan: Writing - original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Jia Meng: Writing - review & editing, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Shao-Wu Zhang, Email: zhangsw@nwpu.edu.cn.

Jia Meng, Email: jia.meng@xjtlu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Wang X. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505(7481):117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou J. Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526(7574):591–594. doi: 10.1038/nature15377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X. N(6)-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell. 2015;161(6):1388–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slobodin B. Transcription Impacts the Efficiency of mRNA Translation via Co-transcriptional N6-adenosine Methylation. Cell. 2017;169(2):326–337 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao W. Nuclear m(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol Cell. 2016;61(4):507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courtney D.G. Epitranscriptomic Addition of m(5)C to HIV-1 transcripts regulates viral gene expression. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26(2):217–227 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boccaletto P. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D303–D307. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCown P.J. Naturally occurring modified ribonucleosides. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2020;11(5) doi: 10.1002/wrna.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones J.D., Monroe J., Koutmou K.S. A molecular-level perspective on the frequency, distribution, and consequences of messenger RNA modifications. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2020;11(4) doi: 10.1002/wrna.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia G.F. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(12):885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominissini D. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485(7397):201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer K.D. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3' UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149(7):1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saletore Y. The birth of the Epitranscriptome: deciphering the function of RNA modifications. Genome Biol. 2012;13(10):175. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz S. High-resolution mapping reveals a conserved, widespread, dynamic mRNA methylation program in yeast meiosis. Cell. 2013;155(6):1409–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roundtree I.A. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell. 2017;169(7):1187–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer K.D. 5' UTR m(6)A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell. 2015;163(4):999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaccara S., Ries R.J., Jaffrey S.R. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(10):608–624. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X. Structural insights into FTO's catalytic mechanism for the demethylation of multiple RNA substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(8):2919–2924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820574116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng G. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alarcon C.R. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m(6)A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell. 2015;162(6):1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu N. N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature. 2015;518(7540):560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature14234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao B.S. m(6)A-dependent maternal mRNA clearance facilitates zebrafish maternal-to-zygotic transition. Nature. 2017;542(7642):475–478. doi: 10.1038/nature21355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batista P.J. m(6)A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(6):707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geula S. Stem cells. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naive pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. 2015;347(6225):1002–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.1261417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertero A. The SMAD2/3 interactome reveals that TGFbeta controls m(6)A mRNA methylation in pluripotency. Nature. 2018;555(7695):256–259. doi: 10.1038/nature25784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delaunay S., Frye M. RNA modifications regulating cell fate in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(5):552–559. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fustin J.M. RNA-methylation-dependent RNA processing controls the speed of the circadian clock. Cell. 2013;155(4):793–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennedy E.M. Posttranscriptional m(6)A Editing of HIV-1 mRNAs enhances viral gene expression. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22(6):830. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan B. Viral and cellular N(6)-methyladenosine and N(6),2'-O-dimethyladenosine epitranscriptomes in the KSHV life cycle. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(1):108–120. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choe J. mRNA circularization by METTL3-eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature. 2018;561(7724):556–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han D. Anti-tumour immunity controlled through mRNA m(6)A methylation and YTHDF1 in dendritic cells. Nature. 2019;566(7743):270–274. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0916-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbieri I. Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m(6)A-dependent translation control. Nature. 2017;552(7683):126–131. doi: 10.1038/nature24678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y. N (6)-methyladenosine RNA modification-mediated cellular metabolism rewiring inhibits viral replication. Science. 2019;365(6458):1171–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.aax4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H.B. m(6)A mRNA methylation controls T cell homeostasis by targeting the IL-7/STAT5/SOCS pathways. Nature. 2017;548(7667):338–342. doi: 10.1038/nature23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoon K.J. Temporal control of mammalian cortical neurogenesis by m(6)A Methylation. Cell. 2017;171(4):877–889 e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi X. Integrating genome-wide association study and methylation functional annotation data identified candidate genes and pathways for schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;96 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ehrenhofer-Murray A.E. Cross-Talk between Dnmt2-Dependent tRNA Methylation and Queuosine Modification. Biomolecules. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.3390/biom7010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuorto F. RNA cytosine methylation by Dnmt2 and NSun2 promotes tRNA stability and protein synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(9):900–905. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X. 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export - NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m(5)C reader. Cell Res. 2017;27(5):606–625. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Y. RNA 5-Methylcytosine facilitates the Maternal-to-Zygotic transition by preventing maternal mRNA Decay. Mol Cell. 2019;75(6):1188–1202 e11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen X. 5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(8):978–990. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0361-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishikura K. Functions and regulation of RNA editing by ADAR deaminases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:321–349. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060208-105251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han L. The genomic landscape and clinical relevance of A-to-I RNA Editing in Human Cancers. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(4):515–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samuel C.E. Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR1), a suppressor of double-stranded RNA-triggered innate immune responses. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(5):1710–1720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.TM118.004166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamashita T., Kwak S. The molecular link between inefficient GluA2 Q/R site-RNA editing and TDP-43 pathology in motor neurons of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Brain Res. 2014;1584:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vlachogiannis N.I. Increased adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing in rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun. 2020;106 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.102329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowling V.H. Regulation of mRNA cap methylation. Biochem J. 2009;425(2):295–302. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pei Y., Shuman S. Interactions between fission yeast mRNA capping enzymes and elongation factor Spt5. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(22):19639–19648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Konarska M.M., Padgett R.A., Sharp P.A. Recognition of cap structure in splicing in vitro of mRNA precursors. Cell. 1984;38(3):731–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muthukrishnan S. 5′-Terminal 7-methylguanosine in eukaryotic mRNA is required for translation. Nature. 1975;255(5503):33–37. doi: 10.1038/255033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang Y. m6A-Atlas: a comprehensive knowledgebase for unraveling the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) epitranscriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D134–D143. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu S. REPIC: a database for exploring the N(6)-methyladenosine methylome. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xuan J.J. RMBase v2.0: deciphering the map of RNA modifications from epitranscriptome sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D327–D334. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu H. MeT-DB V2.0: elucidating context-specific functions of N6-methyl-adenosine methyltranscriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D281–D287. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hauenschild R. The reverse transcription signature of N-1-methyladenosine in RNA-Seq is sequence dependent. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(20):9950–9964. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carlile T.M. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature. 2014;515(7525):143–146. doi: 10.1038/nature13802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hauenschild R. CoverageAnalyzer (CAn): A tool for inspection of modification signatures in RNA sequencing profiles. Biomolecules. 2016;6(4) doi: 10.3390/biom6040042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryvkin P. HAMR: high-throughput annotation of modified ribonucleotides. RNA. 2013;19(12):1684–1692. doi: 10.1261/rna.036806.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt L. Graphical workflow system for modification calling by machine learning of reverse transcription signatures. Front Genet. 2019;10:876. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Motorin Y., Helm M. Methods for RNA modification mapping using deep sequencing: Established and new emerging technologies. Genes. 2019;10(1):35. doi: 10.3390/genes10010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hussain S. Characterizing 5-methylcytosine in the mammalian epitranscriptome. Genome Biol. 2013;14(11):215. doi: 10.1186/gb4143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schaefer M. RNA methylation by Dnmt2 protects transfer RNAs against stress-induced cleavage. Genes Dev. 2010;24(15):1590–1595. doi: 10.1101/gad.586710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huber S.M. Formation and abundance of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in RNA. Chem BioChem. 2015;16(5):752–755. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang T. Genome-wide identification of mRNA 5-methylcytosine in mammals. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2019;26(5):380–388. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Amort T. Distinct 5-methylcytosine profiles in poly(A) RNA from mouse embryonic stem cells and brain. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1139-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Edelheit S. Transcriptome-wide mapping of 5-methylcytidine RNA modifications in bacteria, archaea, and yeast reveals m5C within archaeal mRNAs. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zou Q. Gene2vec: gene subsequence embedding for prediction of mammalian N (6)-methyladenosine sites from mRNA. RNA. 2019;25(2):205–218. doi: 10.1261/rna.069112.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou Y. SRAMP: prediction of mammalian N6-methyladenosine (m6A) sites based on sequence-derived features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(10) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen K. WHISTLE: a high-accuracy map of the human N6-methyladenosine (m6A) epitranscriptome predicted using a machine learning approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(7) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dai C. Iterative feature representation algorithm to improve the predictive performance of N7-methylguanosine sites. Brief Bioinform. 2020 doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen Z. Comprehensive review and assessment of computational methods for predicting RNA post-transcriptional modification sites from RNA sequences. Brief Bioinform. 2020;21(5):1676–1696. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhai J. PEA: an integrated R toolkit for plant epitranscriptome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(21):3747–3749. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu Z.C. iRNAD: a computational tool for identifying D modification sites in RNA sequence. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(23):4922–4929. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Song B. m7GHub: deciphering the location, regulation and pathogenesis of internal mRNA N7-methylguanosine (m7G) sites in human. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(11):3528–3536. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu K., Chen W. iMRM: a platform for simultaneously identifying multiple kinds of RNA modifications. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(11):3336–3342. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li Y.H., Zhang G., Cui Q. PPUS: a web server to predict PUS-specific pseudouridine sites. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(20):3362–3364. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jiang J. m6AmPred: Identifying RNA N6, 2’-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am) sites based on sequence-derived information. Methods. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xue H. Prediction of RNA methylation status from gene expression data using classification and regression methods. Evol Bioinform Online. 2020;16 doi: 10.1177/1176934320915707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Song B. PIANO: A web server for pseudouridine-Site (Psi) identification and functional annotation. Front Genet. 2020;11(88):88. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Song B. PSI-MOUSE: Predicting mouse pseudouridine sites from sequence and genome-derived features. Evol Bioinform Online. 2020;16 doi: 10.1177/1176934320925752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu L. WITMSG: Large-scale prediction of human intronic m(6)A RNA methylation sites from sequence and genomic features. Curr Genom. 2020;21(1):67–76. doi: 10.2174/1389202921666200211104140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu L. ISGm1A: Integration of sequence features and genomic features to improve the prediction of human m1A RNA Methylation Sites. IEEE Access. 2020;8:81971–81977. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu L. LITHOPHONE: Improving lncRNA methylation site prediction using an ensemble predictor. Front Genet. 2020;11(545):545. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jiang J. m5UPred: A Web Server for the Prediction of RNA 5-Methyluridine Sites from Sequences. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;22:742–747. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meyer K.D. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149(7):1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang Y. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9(9):R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dominissini D. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N(6)-methyladenosine by m(6)A-seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(1):176–189. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Love M.I., Hogenesch J.B., Irizarry R.A. Modeling of RNA-seq fragment sequence bias reduces systematic errors in transcript abundance estimation. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(12):1287–1291. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meng J. Exome-based analysis for RNA epigenome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(12):1565–1567. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cui X. A novel algorithm for calling mRNA m6A peaks by modeling biological variances in MeRIP-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(12):i378–i385. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu S. REPIC: a database for exploring the N-6-methyladenosine methylome. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lv H. Evaluation of different computational methods on 5-methylcytosine sites identification. Briefings Bioinf. 2019 doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu L. Bioinformatics approaches for deciphering the epitranscriptome: Recent progress and emerging topics. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:1587–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen W. iRNA-Methyl: Identifying N(6)-methyladenosine sites using pseudo nucleotide composition. Anal Biochem. 2015;490:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang Y., Hamada M. DeepM6ASeq: prediction and characterization of m6A-containing sequences using deep learning. BMC Bioinf. 2018;19(Suppl 19):524. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2516-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]