Patient engagement has become a key component and indicator of high-quality development of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).1–5 Engaging patients in CPG development respects their expertise in the lived experience of clinical conditions and aims to create more patient-centered guideline recommendations.6, 7 As this area of guideline development has matured, guideline development groups and other healthcare policy stakeholders are interested in shifting from engagement of a limited number of patients at isolated phases of CPG development to more in-depth, continuous engagement of a larger group of patients across all stages of the development process.8 Frameworks for continuous patient engagement in CPG development have highlighted various approaches to identify the preferences and perspectives of patients, caregivers, and other patient representatives by using surveys, focus groups, and representation on guideline development groups.9

Online Delphi processes offer a promising approach to rigorous, systematic, scalable, and convenient engagement of patients in all stages of CPG development.10 The online Delphi process is an iterative, multistage method to solicit information and synthesize opinion into group consensus.11 “Traditional” online Delphi processes involve a series of sequential questionnaires answered anonymously by a panel of stakeholders with relevant expertise on the topic of interest.12 Online “modified-Delphi” processes combine survey rounds with a round of moderated, anonymous, online discussion boards.13 For example, ExpertLensTM is an online system for conducting Delphi processes that automatically summarizes responses from each structured questionnaire round, provides these summaries to participants after each round via controlled feedback, and allows them to discuss results using anonymous online discussion boards in which participants post and respond to written comments.14 Combined, these features allow participants to consider their previous opinions, challenge others’ ideas, and stimulate engagement with new concepts without pressures to conform to other participants.

Online modified-Delphi processes are gaining traction as a patient engagement method due to several comparative advantages.15–17 First, they include anonymous discussion boards and controlled feedback that reduce social-cognitive biases (e.g., yielding to real or perceived social pressure) more likely to lead to conformity in group discussion.11 By using successive online surveys, controlled feedback, and anonymous discussions, participants may be more likely to consider group opinions in a non-adversarial manner compared to focus group formats.12 Second, feedback and anonymous discussion that are moderated by the study team may help avoid group dominance by certain individuals and decrease pressures toward group conformity. Third, online modified-Delphi processes maintain a plurality of views through facilitated group interaction. Participants are still informed by the collective opinions of the group and can identify items that may have been missed or thought unimportant, allowing the opportunity for participants to change their opinions in light of feedback.11 This structured process facilitates an efficient and effective way to solicit input from geographically dispersed stakeholders on important and potentially complex topics.13

In light of these advantages, online modified-Delphi processes can be used as a method for patient engagement in CPG development.10 For example, we developed an online modified-Delphiapproach—theRAND/ Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy Patient-Centeredness Method (RPM)—to engage patients and their caregivers in rating the patient-centeredness of CPG recommendations (see Text Box 1).7, 18 Based on findings from a proof-of-concept study, we developed practical step-by-step guidance on how online modified-Delphi process could be used to engage patients and caregivers in determining the patient-centeredness of CPG recommendations.23 Upon reflection of our project, we believe that online modified-Delphi processes can be used throughout all stages of CPG development to continuously engage a panel of patients and their representatives. In this Perspective, we propose ways that guideline development groups can use online modified-Delphi processes to engage a large panel of patients in a manner compatible with best-practices at each stage of CPG development1–5, 24 and consistent with frameworks for continuous patient engagement across the entire CPG development process.9 Unless otherwise specified, “patients” refers to patients, caregivers, and their representatives. While we focus on online modified-Delphi processes, proposals below are also relevant to “traditional” online Delphi processes unless specific to the use of moderated discussion boards.

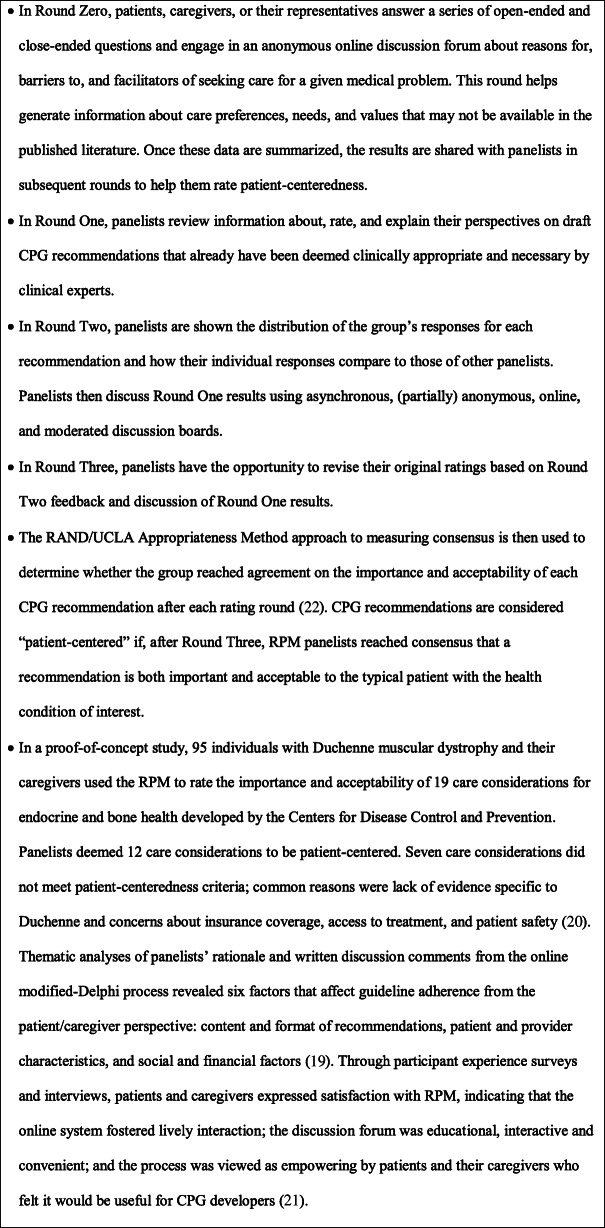

Text Box 1 The RAND/PPMDPatient-Centeredness Method7, 18–21

ONLINE DELPHI PROCESSES AS A CONTINUOUS PATIENT ENGAGEMENT METHOD ACROSS CPG STAGES

At the beginning of the CPG development process, patients can help nominate and prioritize topics that they find important. Online modified-Delphi processes can be used to have patients systematically propose and develop consensus on the most important CPG topics. This process could either help identify an entire disease state that requires CPGs or decide which topics within that disease state to address. Specifically, patients could propose potential topics in an initial and open-ended “brainstorming” round, and then prioritize them during subsequent rounds using close-ended rating or ranking questions. Alternatively, an online modified-Delphi process could help engage patients in prioritizing an existing list of potential topics.

Following topic selection, patients provide a unique perspective on selecting guideline development group members to help ensure the group has a representative and trustworthy composition. Online modified-Delphi processes could be used to propose and prioritize desired characteristics of guideline development group members, including the type of expertise or experience group members should have. Given the importance of balancing conflicts of interest in guideline development groups,25 patients also could indicate which conflicts of interest and mitigation strategies are most salient for developing a given CPG.

Once the guideline development group is established, patients can assist with developing the questions, analytic framework, and research plan for the evidence review to ensure that its scope will be relevant and useful to real-world issues that the CPG aims to address. Online Delphi processes have been used previously to finalize the questions and outcomes addressed in CPGs.26 Specifically, patients can help refine clinical questions to be addressed through an online modified-Delphi process that develops consensus on the importance of sub-populations, outcomes, aspects of treatments, and other elements proposed for inclusion in the research questions, analytic framework, and research plan.27

When forming conclusions about the literature and developing recommendations, patients can appraise the degree to which review summaries and conclusions seem valid, meaningful, and intelligible.28 Patient engagement particularly can assist in developing recommendations that foster shared decision-making, respect variability in patient preferences, and identify gaps from a patient perspective.7, 19 Online modified-Delphi processes can be used to identify consensus on which review summaries and conclusions patients find most believable, credible, or useful. Guideline development groups can then engage patients in recommendation development to ensure that recommendations facilitate patient-centered care. For example, we developed the RPM specifically to engage large numbers of patients and caregivers in rating the patient-centeredness of CPG recommendations already deemed clinically appropriate and necessary.20 Online modified-Delphi processes such as the RPM also can be used in the initial development of recommendations according to established methods for CPG development. For example, the RAND-UCLA Appropriateness Method is used by several groups to identify recommendations that clinicians find appropriate and necessary22; rather than after this step, the RPM could be used concurrently to identify patient consensus on key aspects of evidence-to-decision frameworks,7 such as outcome importance, recommendation acceptability, and equity concerns related to disadvantaged patient sub-populations.29

Once CPGs have been finalized, patients can then assist in disseminating and implementing CPG recommendations, such as facilitating the use of acceptable terminology in CPG recommendations and lay language summaries. For example, patients and patient advocacy groups can endorse guidelines to improve their legitimacy and trustworthiness to patient communities, as well as patient adherence to guideline recommendations. Online modified-Delphi processes can be used to engage patients in identifying items to include in decision aids, as well as barriers and solutions to guideline uptake.19

Lastly, patients can assist in updating and evaluating CPGs, such as determining if and when guidelines require an update, assessing whether patients made meaningful contributions to a CPG, and informing improvements to future patient engagement strategies in CPG development. To facilitate patient engagement at this stage, online modified-Delphi processes can be used to continually assess the current patient-centeredness of CPG recommendations. For example, patients can define and prioritize significant changes in views from the patient community since a CPG has been developed, such as outcomes and interventions that should be included in a CPG update.

RESEARCH AGENDA FOR DELPHI-BASED CONTINUOUS PATIENT ENGAGEMENT IN CPG DEVELOPMENT

We propose several avenues of future research to investigate empirically the potential of using online modified-Delphi processes to continuously engage patients in CPG development. First, future research could directly compare online modified-Delphi processes with other engagement methods to examine comparative advantages to (or synergistic benefits when used in conjunction with) other methods for continuous patient engagement in CPG development.9, 10 For example, future research could examine the value of online modified-Delphi processes that allow patients to interact with each other, reflect on their views in light of feedback from their peers, and explore consensus over iterative rounds by comparing their outcomes to those of online surveys. In addition, future research could test whether the benefits of online modified-Delphi processes over face-to-faceinteractions—such as groupthink, being overruled by traditional experts or professionals, and tokenistic representation—replicate when used with patients in the context of CPG development.11, 12, 14, 30, 31 For example, guideline development groups could examine how much time and resources are needed to ensure patients understand the task and language in online modified-Delphi processes compared to in-person methods that allow for live explanation and training.32, 33 Moreover, empirical studies could examine how online modified-Delphi processes can be used in combination with other engagement strategies to increase the representation of patient views in CPG recommendations.

Recruitment and retention procedures are another important avenue of future research. A major potential advantage of online modified-Delphi processes is their ability to engage a large number of patients with diverse perspectives, despite geographic and transportation barriers.34 As a result, they could enhance representativeness of the target patient population and sub-populations, particularly groups historically underrepresented or marginalized in the development of healthcare policy and practice. To achieve this aim, effective recruitment and retention are essential. While the ability to accommodate a large number of participants is a benefit, it also means guideline development groups may have to spend significant time and resources recruiting and retaining these patients.35 Patients may not have sufficient time, interest, or resources themselves to complete multiple Delphi rounds. Future research could examine strategies we found useful in our RPM pilot project, such as reviewing previous research on patient preferences, using an established and curated patient registry, purposively sampling a diverse group of patients (e.g., demographically, geographically, and in stages of disease progression), and tactics to keep participants engaged across rounds (e.g., personalized reminders, incentives for each round, flexible deadlines).23

Lastly, future research should focus on the conditions under which patient engagement with online modified-Delphi processes is most beneficial. For example, while they could be used to approve proposed members of the guideline development group, this approach could lead to interpersonal tension if patients are asked to rate directly their approval of specific individuals. Moreover, patients may require more training for more-technical stages and aspects of CPG development (e.g., evidence review methodology). In contrast, examples exist of using online Delphi processes as part of finalizing or validating products already drafted by the guideline development group, such as CPG recommendations,36 quality indicators based on guideline recommendations,37 and patient summaries.38 In addition to specific stages of CPG development, continuous patient engagement with online modified-Delphi processes also may vary in utility based on the remit of a given CPG. For example, our RPM pilot focused on care considerations for a genetic disorder with a pediatric onset and with which patients and caregivers have significant lived experience; a CPG focusing entirely on screening and prevention decisions for asymptomatic patient populations may face greater difficulty in sustained, continuous online patient engagement. Future research examining these issues ultimately could shed light on the potential of continuously engaging patients via online modified-Delphi processes to enhance the trustworthiness, credibility, utility, and patient-centeredness of CPG recommendations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the Project Advisory Board for sharing thoughts and suggestions for this paper during our advisory board meetings.

Funding

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program Award (ME-1507-31052). All statements in this article, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, or the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

DK and SG are members of the RAND ExpertLens team. SG’s spouse is a salaried employee of Eli Lilly and Company and owns stock. SG has accompanied his spouse on company-sponsored travel. All other co-authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sean Grant, Email: spgrant@iu.edu.

Courtney Armstrong, Email: carmstro@rand.org.

Dmitry Khodyakov, Email: Dmitry_Khodyakov@rand.org.

References

- 1.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839–E42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine . Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F, Ollenschläger G, Phillips S, van der Wees P, et al. Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann InternMed. 2012;156(7):525–31. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . WHO handbook for guideline development (2nd edition) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krahn M, Naglie G. The next step in guideline development: incorporating patient preferences. JAMA. 2008;300(4):436–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khodyakov D, Denger B, Grant S, Kinnett K, Armstrong C, Martin A, et al. The RAND/PPMDPatient-Centeredness Method: A novel online approach to engaging patients and their representatives in guideline development. Eur J Person Cent Healthc. 2019;7(3):470–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong MJ, Bloom JA. Patient involvement in guidelines is poor five years after institute of medicine standards: review of guideline methodologies. Res Involv Engag. 2017;3(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40900-017-0070-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong MJ, Rueda JD, Gronseth GS, Mullins CD. Framework for enhancing clinical practice guidelines through continuous patient engagement. Health Expect. 2017;20(1):3–10. doi: 10.1111/hex.12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant S, Hazlewood GS, Peay HL, Lucas A, Coulter I, Fink A, et al. Practical considerations for using online methods to engage patients in guideline development. Patient-Patient-Cent Outcomes Res. 2018;11(2):155–66. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanders CFB, Askham J, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(3). [PubMed]

- 12.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalal S, Khodyakov D, Srinivasan R, Straus S, Adams J. ExpertLens: A system for eliciting opinions from a large pool of non-collocated experts with diverse knowledge. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2011;78(8):1426–144. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2011.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber C, Marshall D, Mosher D, Akhavan P, Tucker L, Houghton K, et al. Development of system-level performance measures for evaluation of models of care for inflammatory arthritis in Canada. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(3):530–40. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall DA, Smith H, Heffernan E, Fackrell K. Recruiting and retaining participants in e-Delphi surveys for core outcome set development: Evaluating the COMiT'ID study. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0201378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khodyakov D, Grant S, Barber CE, Marshall DA, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Acceptability of an online modified Delphi panel approach for developing health services performance measures: results from 3 panels on arthritis research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(2):354–60. doi: 10.1111/jep.12623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khodyakov D, Kinnett K, Grant S, Lucas A, Martin A, Denger B, et al. Engaging patients and caregivers managing rare diseases to improve the methods of clinical guideline development: A research protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(4):e57. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denger B, Kinnett K, Martin A, Grant S, Armstrong C, Khodyakov D. Patient and caregiver perspectives on guideline adherence: the case of endocrine and bone health recommendations for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14:205. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1173-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khodyakov D, Grant S, Denger B, Kinnett K, Martin A, Booth M, et al. Using an online modified-Delphi approach to engage patients and caregivers in guideline development: A case study of patient-centeredness of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy care considerations. Med Decis Making. 2019;39(8):1019–31. doi: 10.1177/0272989X19883631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong C, Grant S, Kinnett K, Denger B, Martin A, Coulter I, et al. Participant experiences with a new online modified-Delphi approach for engaging patients and caregivers in developing clinical guidelines. Eur J Person Cent Healthc. 2019;7(3):476–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, Burnand B, LaCalle JR. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user's manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khodyakov D, Grant S, Denger B, Kinnett K, Martin A, Peay H, et al. Practical considerations in using online modified-Delphi approaches to engage patients and other stakeholders in clinical practice guideline development. Patient: Patient-Cent Outcomes Res. 2020;13:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s40271-019-00389-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, Falavigna M, Santesso N, Mustafa R, et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):E123–E42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schünemann HJ, Al-Ansary LA, Forland F, Kersten S, Komulainen J, Kopp IB, et al. Guidelines International Network: principles for disclosure of interests and management of conflicts in guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):548–53. doi: 10.7326/M14-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pai M, Yeung CH, Akl EA, Darzi A, Hillis C, Legault K, et al. Strategies for eliciting and synthesizing evidence for guidelines in rare diseases. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Atkins D, Brozek J, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, Synnot A, Nunn J, Hill S, et al. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: A scoping review. System Rev. 2018;7(1):208. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0852-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Meyrick J. The Delphi method and health research. Health Educ. 2003;103(1):7–16. doi: 10.1108/09654280310459112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keeney S, McKenna H, Hasson F. The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van de Bovenkamp HM, Trappenburg MJ. Reconsidering patient participation in guideline development. Health Care Anal. 2009;17:198–216. doi: 10.1007/s10728-008-0099-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Wersch A, Eccles M. Involvement of consumers in the development of evidence based clinical guidelines: practical experiences from the North of England evidence based guideline development programme. Qual Health Care. 2001;10:10–6. doi: 10.1136/qhc.10.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Haire C, McPheeters M, Nakamoto E, LaBrant L, Most C, Lee K, et al. Engaging Stakeholders To Identify and Prioritize Future Research Needs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockeville, MD; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Légaré F, Boivin A, van der Weijden T, Pakenham C, Burgers J, Légaré J, et al. Patient and public involvement in clinical practice guidelines: a knowledge synthesis of existing programs. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(6):E45–E74. doi: 10.1177/0272989X11424401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Wit MP, Berlo SE, Aanerud GJ, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Croucher L, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the inclusion of patient representatives in scientific projects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):722–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.135129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.den Breejen EME, Nelen WLDM, Schol SFE, Kremer JAM, Hermens RPMG. Development of guideline-based indicators for patient-centredness in fertility care: what patients add. Human Reprod. 2013;28(4):987–96. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boelens PG, Taylor C, Henning G, Marang-van de Mheen PJ, Espin E, Wiggers T, et al. Involving patients in a multidisciplinary European consensus process and in the development of a ‘patient summary of the consensus document for colon and rectal cancer care’. Patient: Patient-Cent Outcomes Res. 2014;7(3):261-70. [DOI] [PubMed]