Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the effect of concomitant use of levothyroxine (LT4) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) on thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels in patients with primary hypothyroidism.

Methods

A systematic review of interventional and observational studies that compared the TSH levels before and after concomitant use of LT4 and PPI was performed. Articles published in English up to September 1, 2019, were included. PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases. Gray literature was also searched in repositories, websites OpenGrey and Google Scholar, and abstracts of major international congresses. Study quality was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale for observational studies and the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was used.

Results

Five thousand twelve discrete articles were identified. Following assessment and application of eligibility criteria, seven studies were included. There was a considerable heterogeneity among the included studies in design, sample size, inclusion and exclusion criteria, treatment regimen, and baseline demographics. Each of the included studies showed an increase in TSH levels following LT4 and PPI consumption, and in the majority of these, the increase was statistically significant.

Discussion

The concomitant use of LT4 and PPI showed a significant increase in TSH concentration. However, given the small number of studies, further research is needed to clarify the interfering role of PPI on LT4 intestinal absorption.

PROSPERO Registration Number

CRD42020047084.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-020-06403-y.

KEY WORDS: hypothyroidism, drug interaction, levothyroxine

INTRODUCTION

The use of levothyroxine (LT4) as the mainstay of treatment for hypothyroidism is a common clinical practice considered simple and safe.1–5 As symptoms and signs of hypothyroidism are neither sensitive nor specific, periodic assessment of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which reflects plasma concentrations of free thyroid hormones, is used to assess the adequacy of LT4 therapy.2–5 Therefore, serum TSH is an indirect marker of intestinal absorption of thyroxine.4–6 Increased LT4 requirements may stem from either reduced intestinal absorption (due to gastrointestinal diseases, food, beverages, or medications)6–10 or increased clearance.11 An optimum gastric acidity environment is a prerequisite for effective tablet LT4 absorption.12–16

Regarding gastrointestinal disorders, atrophic gastritis causing hypochlorhydria and Helicobacter pylori infection via ammonia production increase gastric pH, which is the major cause of tablet LT4 malabsorption.17,18 Gastrointestinal manifestations are common in thyroid disease, and also patients with hypothyroidism may experience dyspepsia or nausea due to delayed gastric emptying.19,20 The reduction of gastric acid is the target of certain medications in patients with common diseases such as dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux, and peptic ulcer. One such class of drugs includes proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which act by blocking the secretion of gastric acid through covalent binding to the H+/K+ ATPase enzyme.21,22 Hence, they are capable of reducing significantly LT4 absorption by increasing the gastric pH.23–25

In an observational retrospective study, a significant interaction between LT4 and PPI, which led to recurrence of hypothyroid state, was reported.26 Other studies with a retrospective design confirmed this interaction.27,28

However, there is also evidence that PPIs do not have influence on LT4 absorption in both healthy volunteers29,30 and treated hypothyroid patients.31

The contradictory findings mentioned may result from the limited size of the cohorts analyzed as well as differences in subjects enrolled (patients vs. healthy volunteers). To clarify the effect of the concomitant ingestion of PPI and tablet LT4, we conducted a systematic review of interventional and observational studies in the literature aiming at determining serum TSH changes before and after the concomitant use of these two drugs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature Search

A systematic review of studies was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement32 with the Reference Librarian’s assistance. The methods were stipulated in a protocol that was registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews33 under the registration number CRD42020047084. After developing the clinical question and translating it into a well-defined systematic review question based on the PICOS (patients, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and studies) format, a manual search was performed in PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library for studies published in the English language from the inception of each database through September 1, 2019. Gray literature was also searched in repositories, websites OpenGrey and Google Scholar, and abstracts of major international congresses. The search was conducted using the following PICOS format: P: patients with hypothyroidism and dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux, or peptic ulcer; I: patients treated with LT4 and PPI; C: patients with concomitant ingestion of LT4 and PPI; O: TSH levels; S: interventional and observational studies. Supplementary Table S1 shows the specific search strategy for each database reviewed.

The results were supplemented by a manual search of the bibliographies of the shortlisted review and original study articles. In addition, a number of field experts were approached in order to identify additional viable studies from the gray literature. Two independent investigators (YGP and OS) separately screened the titles and abstracts for eligible studies published up to September 1, 2019. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between all authors.

Study Selection

Studies were included if (1) they were interventional or observational studies on humans; (2) > 18-year-old patients were enrolled; (3) primary hypothyroidism coexisted with dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux, or peptic ulcer; (4) patients took orally both tablet LT4 and PPIs (omeprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, and/or rabeprazole at any dose); and (5) serum TSH was one endpoint. Studies were excluded if (1) they were case reports, editorial, comment, or letters and (2) they were written in languages other than English. Conflicts in study selection at this stage were resolved by discussion between the researchers, referring back to the original article in consensus between all authors.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The selected studies were reviewed and data was extracted by two researchers (YGP and OS) independently. Discrepancies between them were resolved by consensus between all authors. Numeric and texted data were extracted from the eligible articles as follows: country/region, author, publication year, study type, number of patients, age, LT4 dose, PPI dose, TSH levels before and after concomitant use of PPI. Data was extracted into a bibliographic database using Microsoft® Office Excel® version 14.0 software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

The Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale was used to assess the quality of the observational studies, evaluating three items: patient selection, comparability of study groups, and assessment of outcomes.34 Regarding interventional studies, the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was used to explore the existence of confounding bias, selection bias, bias in classification of interventions, bias in deviation from intended interventions, bias due to missing data, bias in measurement of outcome, and bias in selection of the reported results.35 No randomized controlled trials were found in the literature search. We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) assessment to assess the overall quality of evidence.36 Studies were not excluded a priori based on quality reporting assessment. Two researchers (YGP and OS) independently evaluated the risk of bias. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between all authors.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

A narrative synthesis of the findings from the included studies was structured around the study design, sample size, target population characteristics, dosage and length regimens of LT4 and PPI, and mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range of TSH levels before and after concomitant use of LT4 and PPI measurements.

RESULTS

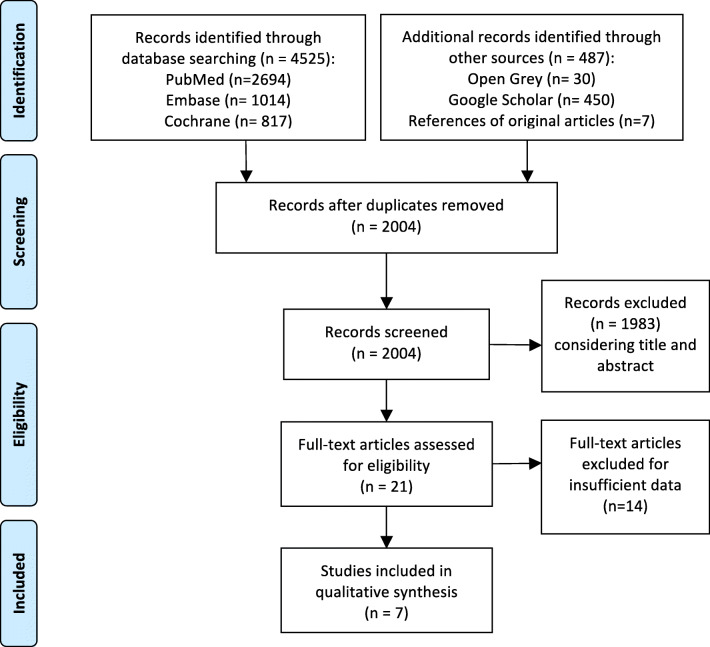

In the preliminary search, 5012 studies were identified through the literature search, and 2004 remained after the duplicates were removed. A title and abstract review was performed on the remaining 2004 studies, with 1983 excluded at this first stage for not meeting the PICOS criteria. A total of 21 articles were eligible for full-text screening. Seven full-text publications were included in the analysis. A PRISMA flow diagram of the screening and selection process can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Two studies included in the analysis were observational26,27 and five interventional 25,28,31,37,38 studies. Five of them had a prospective design25,28,31,37,38 and two were retrospective.26,27 The studies were published between 2006 and 2015. Four studies were from Italy,25,28,37,38 one from the UK,26 one from the USA,27 and one from Brazil.31

In all studies, patients took tablet LT4, but in two,37,38 the liquid formulation was also used. The purpose of LT4 treatment was replacement in six studies26–28,31,37,38 or TSH-suppression in one study,25 with three studies including patients on both replacement and TSH-suppression.25,37,38 Two studies31,38 reported an interval between LT4 and PPI ingestion of 30 min, whereas in the remaining five, no interval was given. The PPIs used in the studies were omeprazole25,26,31,37,38; lansoprazole26,27,37,38; pantoprazole26,37,38; esomeprazole26,38; and rabeprazole.26 Their doses ranged from 20 to 40 mg/day. Concerning how long was target TSH maintained on a stable LT4 dose before commencement of PPI, in the papers by Abi-Abib,31 Irving,26 and Trifirò,28 this period was > 1 year, while in that of Sachmechi,27 it was > 6 months. Particularly, in the Scottish one, a subset of patients had had stable serum TSH for > 2 years.26 The other three papers did not mention this period. Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Selected Studies

| Country | Author, year (ref.) | Study type | Number of patients (female/male) | Age (mean) years | LT4 dose | PPI dose | TSH mU/l before PPI | TSH mU/l after PPI | Follow-up | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Centanni, 200625 | Interventional, non-randomized controlled study | 10 (F) | NS |

1.58 μg/kg/day tablets (Eutirox®) Was taken at least 1 h before breakfast |

omeprazole 40 mg/day |

0.1 | 1.70 | 6 months | Low risk of bias* |

| UK | Irving, 201526 | Observational, retrospective | 1491 | 58.1 |

Tablets. For at least 6 months |

omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole esomeprazole rabeprazole | 1.51 ± 2.64 | 1.69 ± 2.83 | 6 months | Good quality** |

| USA | Sachmechi, 200727 | Observational, retrospective |

37 (30 F, 7 M) |

59 ± 7.5 |

25 to 200 μg/day (mean 82.8 ± 40.3) (tablets) For at least 6 months |

lansoprazole 30 mg/day | 2.34 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 2–6 months | Good quality** |

| Brazil | Abi-Abib, 2014,31 | Interventional, uncontrolled before–after study |

All: 19 Group omeprazole 20 mg: 10 (8 F 2 M). Group omeprazole 40 mg: 9 (8 F, 1 M). |

Group 1 (omeprazole 20 mg): 54.6 ± 10.9 Group 2 (omeprazole 40 mg): 50.6 ± 10.2 |

Tablets (Puran T4®) for at least 1 year. Was taken at least 30 min before PPI, and PPI 15 min before breakfast |

Group 1: omeprazole 20 mg (Neoprazol®) Group 2: omeprazole 40 mg (Neoprazol®) |

All: 2.48 ± 1.12. Group omeprazole 20 mg: 2.45 ± 0.98. Group omeprazole 40 mg: 2.51 ± 1.33. |

All: 2.76 ± 1.75. Group omeprazole 20 mg: 2.80 ± 1.80. Group omeprazole 40 mg: 2.71 ± 1.79. |

3 months | Low risk of bias* |

| Italy | Trifiró. 2015,28 | Quasi-experimental pre–post analysis | 3787 | 54.6 ± 14.47 | NS | NS | NS | TSH levels increased with the concomitant use of PPI (adjusted IRR: 1.02; 95% CI: 1.01–1.03) | 15 days | Low risk of bias* |

| Italy | Saraceno, 201237 | Interventional non-randomized crossover study |

All: 15 (12 F, 3 M). Group 1 (REP): 6 Group 2 (SUP): 9 |

NS | Tablets and then oral solution (Tirosint®) |

omeprazole (n = 7) pantoprazole (n = 5) lansoprazole (n = 3) |

NS |

Group 1 (REP) LT4 tablet and PPI: 2.77 ± 2.05. LT4 solution and PPI: 1.63 ± 0.66. Group 2 (SUP) LT4 tablet and PPI: 1.15 ± 1.85. LT4 solution and PPI: 0.12 ± 0.12 |

2 months after switch | Moderate risk of bias* |

| Italy | Vita, 201438 | Interventional non-randomized study |

All: 24 (18 F, 6 M) Group 1 (REP): 14 (11 F, 3 M) Group 2 (SUP): 10 (7 F, 3 M) |

All: 56.2 ± 14.5 Group 1: 63.3 ± 11.2 Group 2: 46.7 ± 13.2 |

Tablets and then oral solution (Tirosint®) 1.5 μg/kg/day ± 0.4. Was taken 30 min before PPI and 60 min before breakfast |

omeprazole (n = 9) pantoprazole (n = 7) lansoprazole (n = 6) esomeprazole (n = 2) |

NS |

Group 1 (REP) LT4 tablet and PPI: 5.4 ± 4.3. LT4 solution and PPI: 1.7 ± 1.0. Group 2 (SUP) LT4 tablet and PPI: 2.1 ± 2.7 LT4 solution and PPI: 0.1 ± 0.3 |

Group 1: 20.0 ± 7.5 weeks Group 2: 28.8 ± 15.2 weeks |

Low risk of bias* |

*The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I)30 tool was used to evaluate seven bias domains as low, moderate, or serious risk of bias

**Assessed by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale29 for observational studies with a score of 8/9 (maximum of 9 points). Score > 6 points is considered to be of high quality. NS not specified, TSH thyroid-stimulating hormone, LT4 levothyroxine, PPI proton pump inhibitor, NOS Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, F female, M male, REP replacement therapy, SUP suppressive therapy, IRR incidence rate ratio

While all included studies provide essential data on TSH levels after concomitant use of LT4 and PPI, just four studies reported TSH levels before PPI,25–27,31 one of which did not inform the standard deviation or interquartile range.25 Notably, important study differences regarding the sample size, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, form of LT4, dose adjustment, co-medications, and comorbidities among the included studies prevent direct comparisons. Therefore, the results of this systematic review were summarized qualitatively.

Findings from Studies with LT4 Tablet Formulation

In an interventional, non-randomized, controlled study by Centanni et al.,25 10 female patients with multinodular goiter and gastroesophageal reflux disease were treated with LT4 at a median dose of 1.58 μg/kg per day. The median level of TSH was 0.1 mU/l while on LT4 alone, but 1.70 mU/l upon addition of omeprazole 40 mg/day, this difference being statistically significant (p = 0.002). Of note, the authors reported a second analysis with an increase in LT4 dose (median, 2.16 μg/kg) while continuing to receive omeprazole at the same dose (40 mg/day), and found that the low level of TSH was re-established (median, 0.1 mU/l).

The study by Irving et al.26 included 1491 patients aged on average 58 years who were prescribed LT4 on at least three occasions in the 6 months before PPIs were initiated. The authors did not report data concerning the dose of LT4. Patients with history of pituitary disorder or use of carbimazole, propylthiouracil, or amiodarone were excluded. The median level of TSH after LT4 treatment was 1.51 mU/l (interquartile range, 2–64). There was an increase in the TSH level after the concomitant use of LT4 and PPIs (omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, esomeprazole, or rabeprazole) with a median TSH of 1.69 (range, 2–83) mU/l. The change in the median TSH was 0.18 mU/l (p = 0.001). The authors stated that a change of more than 5 mU/l was recognized as being more likely to be of clinical significance. In addition, there was a sub-study looking at patients who were on an unchanged dose of LT4 for at least 2 years. These patients had median TSH levels of 1.52 mU/l before taking PPI but 1.64 mU/l while on PPI (p = 0.01). In this subset of patients, 5.6% had an increase of 5 mU/l and 3.2% had a decrease of 5 mU/l in the levels of TSH.

Sachmechi et al.27 retrospectively reviewed 92 patients with primary hypothyroidism who were receiving between 25 and 200 μg of LT4 daily for a period of at least 6 months before the start of the study, without a change in LT4 dose. Patients with history of comorbidities and use of drugs known to affect TSH metabolism were excluded. Thirty-seven patients were included in the study group, who received concomitantly lansoprazole 30 mg daily, and 55 patients were allocated to the control group receiving stable dose of LT4 alone. In the study group, the mean change of TSH after 2 and 6 months of follow-up was statistically significant (0.69 μgIU/ml; p = 0.03), whereas the change reported in the control group (0.11 μgIU/ml) was not statistically significant (p = 0.45). Of note, 19% of participants had TSH levels higher than 5 μIU/ml after PPI ingestion and required 35% mean increase in LT4 dose.

In an interventional uncontrolled before–after study, Abi-Abib et al.31 recruited 19 patients who were taking LT4 for at least 1 year before the study. As described in the previous studies, patients with history of comorbidities and use of drugs known for interfering with LT4 absorption or TSH metabolism were excluded. The patients were allocated into two groups according to the esomeprazole dose: 20 mg or 40 mg. After 3 months, in the first group, there was no significant difference in TSH levels before and after the concomitant use of PPIs (median levels: 2.24 vs. 2.42 mU/l; p = 0.62). Similarly, the group taking omeprazole 40 mg showed no significant variation in TSH values (2.28 vs. 2.30 mU/l; p = 0.82).

Trifiró et al.28 conducted a quasi-experimental pre–post analysis using a self-controlled study design. In total, 3787 patients on LT4 were co-prescribed PPIs. TSH levels before and 15 days after the concomitant use of PPIs were compared. Multivariate analyses were performed adjusting for potential confounders including gastrointestinal diseases related to malabsorption condition. TSH levels increased with the exposure to PPIs (adjusted incidence rate ratio: 1.02; 95% CI: 1.01–1.03). Interestingly, the authors also found an increasing dose of LT4 once the exposure to PPI started suggesting that clinicians increased the number of LT4 prescriptions in order to re-establish TSH levels.

Findings from Studies with LT4 Liquid Formulation

Saraceno et al.37 carried out a crossover study in 15 patients on LT4, 6 of them on replacement therapy and 9 on TSH-suppressive therapy, who were receiving PPI. The patients switched from the tablet to the oral solution of LT4. Serum levels of TSH were lower under the oral solution compared with the tablet both in the replacement group (1.63 ± 0.66 mU/l vs. 2.77 ± 2.05 mU/l) and in the suppressive group (0.12 ± 0.12 mU/l vs.1.15 ± 1.85 mU/l).

Likewise, one coauthor of this paper (RV)38 evaluated the efficacy of a liquid formulation of LT4 in correcting tablet LT4 malabsorption by PPI in 24 patients, switching from the LT4 tablet formulation to the oral solution while maintaining the same dose. Indeed, serum TSH levels were lower under the oral solution compared with the tablet both in the replacement group (1.7 mU/l ± 1.0 vs. 5.4 mU/l ± 4.3) and in the TSH-suppressive group (0.1 mU/l ± 0.3 vs. 2.1 mU/l ± 2.7).

Quality Assessment

Regarding the quality assessment, six out of seven studies were considered at low risk of bias,25–28,31,38 while one37 was considered at moderate risk because of measurement of outcomes. A detailed assessment of the systematic error risk of all included studies is presented in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, and Supplementary Figures S1 and S2. The GRADE quality of evidence suggested that there was moderate quality of evidence in the included studies (Supplementary Table S4).

DISCUSSION

LT4 and PPIs are two of the most frequently prescribed drugs. As these two drugs are frequently co-ingested, our findings can have consequences in the clinical practice. Very recently, Benvenga reported that around half of LT4 users take at least one drug interfering with LT4 intestinal absorption.39 Not unexpectedly, the most frequent interferers are PPIs, either alone (74.8%) or in combination (25.2%) with other such drugs.39 Another study on more than 5000 LT4 users showed that in approximately 70% of them, PPIs were co-prescribed.28 In such patients, an increase of > 5 mU/l in serum TSH levels may occur.26

The present systematic review shows that in patients who take LT4, the concomitant use of PPI may reduce its intestinal absorption, reflected by a significant increase in serum TSH. This is consistent with the studies in the literature demonstrating that PPI may interact with LT4 by increasing the gastric pH thus impairing LT4 intestinal absorption.28,40–42 In our systematic review, we elected to include pre–post studies on patients on stable doses of T4 who had started PPI, as the outcome of interest was the impact of this drug on TSH levels. We do think that pre–post studies, in which patients serve as their own control, are more helpful than other types of studies, such as randomized trials. However, we were unable to pool the data because of the small number of included studies and the differences in study characteristics, namely the sample size, form of LT4, dose adjustment, co-medications, and comorbidities. Although there was a common study design and treatment in two studies,26,27 the number of patients in these studies varied too greatly to support a valid meta-analysis. In addition, the TSH measures pre and post intervention were not independent from each other, thereby preventing the performance of a meta-analysis on pre–post effect sizes.43

It is noteworthy that in two studies37,38 patients were switched from the tablet formulation to the liquid one while maintaining the co-ingestion of PPI and the daily dose of LT4, with a significant decrease in serum TSH levels (Table 1). Recently, Virili et al. reviewed systematically and meta-analyzed studies in the literature addressing TSH level changes after the switch from the traditional tablet LT4 to the oral solution at the same daily dose.44 The authors found that after the switch, suboptimal TSH levels improved significantly.44 Apart from the small sample size of the studies analyzed, the authors highlighted also another potential limitation of their meta-analysis, namely the same country (Italy) in which studies were performed, given the large availability of liquid LT4.

In this regard, two novel formulations, i.e., the liquid formulation and the soft gel capsule, have been recently developed and marketed in most, but not all, countries. Both formulations have been demonstrated to solve malabsorption issues due to a number of drugs,37,41,45,46 beverages,47 and gastrointestinal48 and non-gastrointestinal diseases.11 However, the traditional tablet LT4 is the most frequently prescribed formulation in the least developed countries and in countries where the organization that is paying for the medicine opts for a less expensive LT4 product, such as the generic one.49,50 An overlooked aspect is also the different composition of LT4 formulations. Particularly, while in the tablet formulation a number of inactive ingredients are present, the oral solution and the soft gel capsule include only two excipients, namely ethanol and glycerine or gelatine and glycerine, respectively.51 In turn, the different composition may account for differences in pharmacokinetics.50

Major strengths of our study include a broad literature search including also sources of gray literature and the rigorous methodology for performing systematic reviews to eliminate potential biases. However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings: (i) the limited number of available studies. Only seven studies were included, and most of these studies, except one,26 included small cohorts of patients. Among them, only four studies have TSH before PPI administration; (ii) the lack of well-designed randomized controlled trials; (iii) a poor description of confounding factors such as comorbidities, diet, and adherence to the treatment, preventing us from speculating in that regard; (iv) heterogeneity between studies, as most of them differed in sample size and study design; (v) the lack of statistical procedure for combining numerical data from different studies; (vi) the search strategy limited to the English language due to restricted resources to perform this investigation may have increased the risk of bias in the outcomes. A total of 243 articles either written in languages other than English or without an English version were excluded. In addition, a relatively short follow-up period (up to 7 months) in the studies included in our review and not carefully evaluating drug exposures in observational studies may impose additional risk of bias.

CONCLUSION

Each of the included studies showed an increase in TSH levels following LT4 and PPI consumption and in the majority of these, the increase was statistically significant. This effect could be much evident in subjects in whom LT4 absorption is already impaired for other reasons. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution due to the limited number of studies with relatively short follow-up period and lack of robust statistical evidence. Well-designed large studies are needed in order to further better clarify the interfering role of PPI on LT4 intestinal absorption.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 118 kb)

Author Contributions

Conception and design: YGP, RV, OS. Drafting of the article: YGP. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: YGP, RV, OS. Final approval of the article: YGP, RV, OS.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuli Guzman-Prado, Email: juliguzmanprado@outlook.com.

Roberto Vita, Email: roberto.vita@yahoo.it.

Ondrej Samson, Email: ondsam@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Okosieme O, Gilbert J, Abraham P, Boelaert K, Dayan C, Gurnell M, Leese G, McCabe C, Perros P, Smith V, Williams G. Management of primary hypothyroidism: statement by the British Thyroid Association Executive Committee. Clin Endocrinol. 2016;84(6):799–808. doi: 10.1111/cen.12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hennessey JV. The emergence of levothyroxine as a treatment for hypothyroidism. Endocrine. 2017;55(1):6–18. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centanni M, Benvenga S, Sachmechi I. Diagnosis and management of treatment-refractory hypothyroidism: an expert consensus report. J Endocrinol Investig. 2017;40(12):1289–301. doi: 10.1007/s40618-017-0706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappola AR, Arnold AM, Wulczyn K, Carlson M, Robbins J, Psaty BM. Thyroid function in the euthyroid range and adverse outcomes in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(3):1088–96. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, Burman KD, Cappola AR, Celi FS, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association Task Force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24:1670–751. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiPiro J, Talbert R, Yee G, Matzke G, Wells B, Posey LM. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 9e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2014.

- 7.Liwanpo L, Hershman JM. Conditions and drugs interfering with thyroxine absorption. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23(6):781–92. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benvenga S, Bartolone L, Pappalardo MA, Russo A, Lapa D, Giorgianni G, Saraceno G, Trimarchi F. Altered intestinal absorption of L-thyroxine caused by coffee. Thyroid. 2008;18(3):293–301. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benvenga S, Di Bari F, Vita R. Undertreated hypothyroidism due to calcium or iron supplementation corrected by oral liquid levothyroxine. Endocrine. 2017;56(1):138–45. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Virili C, Bassotti G, Santaguida MG, Iuorio R, Del Duca SC, Mercuri V, Picarelli A, Gargiulo P, Gargano L, Centanni M. Atypical celiac disease as cause of increased need for thyroxine: a systematic study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(3):E419–22. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benvenga S, Vita R, Di Bari F, Fallahi P, Antonelli A. Do not forget nephrotic syndrome as a cause of increased requirement of levothyroxine replacement therapy. Eur Thyroid J. 2015;4(2):138–42. doi: 10.1159/000381310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groener JB, Lehnhoff D, Piel D, et al. Subcutaneous application of levothyroxine as successful treatment option in a patient with malabsorption. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:48–51. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.883788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benvenga S. When thyroid hormone replacement is ineffective? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:467–77. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker JN, Shillo P, Ibbotson V, et al. A thyroxine absorption test followed by weekly thyroxine administration: a method to assess non-adherence to treatment. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168:913–7. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centanni M. Thyroxine treatment: absorption, malabsorption, and novel therapeutic approaches. Endocrine. 2013;43:8–9. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9814-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Virili C, Antonelli A, Santaguida MG, Benvenga S, Centanni M. Gastrointestinal malabsorption of thyroxine. Endocr Rev. 2018;40(1):118–36. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skelin M, Lucijanić T, Klarić DA, Rešić A, Bakula M, Liberati-Čizmek AM, Gharib H, Rahelić D. Factors affecting gastrointestinal absorption of levothyroxine: a review. Clin Ther. 2017;39(2):378–403. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carvalho GA, Fighera TM. Effect of gastrointestinal disorders in autoimmune thyroid diseases. Transl Gastrointest Cancer. 2014;4(1):76–82. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4778.2014.07.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daher R, Yazbeck T, Jaoude JB, Abboud B. Consequences of dysthyroidism on the digestive tract and viscera. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(23):2834–2838. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebert EC. The thyroid and the gut. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44(6):402–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181d6bc3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin JM, Kim N. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of the Proton Pump Inhibitors. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:25–35. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badillo R, Francis D. Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2014;5:105–12. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v5.i3.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang JH, Kang HS, Lee SY, Kim JH, Sung IK, Park HS, Shim CS, Jin CJ. Recurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease correlated with a short dinner-to-bedtime interval. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:730–735. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yue CS, Benvenga S, Scarsi C, Loprete L, Ducharme M. When bioequivalence in healthy volunteers may not translate to bioequivalence in patients: differential effects of increased gastric pH on the pharmacokinetics of levothyroxine capsules and tablets. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;18(5):844–55. doi: 10.18433/J36P5M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centanni M, Gargano L, Canettieri G, Viceconti N, Franchi A, Fave GD, Annibale B. Thyroxine in goiter, Helicobacter pylori infection, and chronic gastritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1787–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irving SA, Vadiveloo T, Leese GP. Drugs that interact with levothyroxine: an observational study from the Thyroid Epidemiology, Audit and Research Study (TEARS) Clin Endocrinol. 2015;82:136–141. doi: 10.1111/cen.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sachmechi I, Reich DM, Aninyei M, et al. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on serum thyroid stimulating hormone level in euthyroid patients treated with levothyroxine for hypothyroidism. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:345–349. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trifirò G, Parrino F, Sultana J, et al. Drug interactions with levothyroxine therapy in patients with hypothyroidism: observational study in general practice. Clin Drug Invest. 2015;35:187–195. doi: 10.1007/s40261-015-0271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietrich JW, Gieselbrecht K, Holl RW, Boehm BO. Absorption kinetics of levothyroxine is not altered by proton-pump inhibitor therapy. Horm Metab Res. 2006;38:57–59. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ananthakrishnan S, Braverman LE, Levin RM, et al. The effect of famotidine, esomeprazole, and ezetimibe on levothyroxine absorption. Thyroid. 2008;18:493–498. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abi-Abib RD, Vaisman M. Is it necessary to increase the dose of levothyroxine in patients with hypothyroidism who use omeprazole? Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab. 2014;58(7):731–6. doi: 10.1590/0004-2730000002997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.PROSPERO—International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews. (University of York, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, United Kingdom, 2015). http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed 1 May 2020).

- 34.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [Available: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp] Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. [Accessed 1st September, 2019].

- 35.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355. 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saraceno G, Vita R, Trimarchi F, Benvenga S. Interference of L-T4 absorption by proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) can be solved by a liquid formulation of L-thyroxine (L-T4) Thyroid. 2012;22(s1):a50. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vita G, Saraceno F, Trimarchi S, Benvenga S. Switching levothyroxine from the tablet to the oral solution formulation corrects the impaired absorption of levothyroxine induced by proton-pump inhibitors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:4481–4486. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benvenga S, Pantano R, Saraceno G, Lipari L, Alibrando A, Inferrera S, Pantano G, Simone G, Tamà S, Scoglio R, Ursino MG. A minimum of two years of undertreated primary hypothyroidism, as a result of drug-induced malabsorption of L-thyroxine, may have metabolic and cardiovascular consequences. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2019;16:100189. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2019.100189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vita R, Di Bari F, Benvenga S. Oral liquid levothyroxine solves the problem of tablet levothyroxine malabsorption due to concomitant intake of multiple drugs. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2017;14(4):467–72. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2017.1290604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vita R, Benvenga S. Tablet levothyroxine (L-T4) malabsorption induced by proton pump inhibitor; a problem that was solved by switching to L-T4 in soft gel capsule. Endocr Pract. 2013;20(3):e38–41. doi: 10.4158/EP13316.CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guzman-Prado Y, Vita R, Samson O. The impact of proton pump inhibitors on levothyroxine absorption: The good, the bad and the ugly. Eur J Internal Med. 2020;76:118–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuijpers P, Weitz E, Cristea IA, Twisk J. Pre-post effect sizes should be avoided in meta-analyses. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2017;26:364–368. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Virili C, Giovanella L, Fallahi P, Antonelli A, Santaguida MG, Centanni M, Trimboli P. Levothyroxine Therapy: Changes of TSH Levels by Switching Patients from Tablet to Liquid Formulation. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:10. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trimboli P, Virili C, Centanni M, Giovanella L. Thyroxine treatment with softgel capsule formulation: usefulness in hypothyroid patients without malabsorption. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:118. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cappelli C, Pirola I, Gandossi E, Formenti A, Castellano M. Oral liquid levothyroxine treatment at breakfast: a mistake? Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170:95–99. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vita R, Saraceno G, Trimarchi F, Benvenga S. A novel formulation of L-thyroxine (L-T4) reduces the problem of L-T4 malabsorption by coffee observed with traditional tablet formulations. Endocrine. 2013;43(1):154–60. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santaguida MG, Virili C, Del Duca SC, Cellini M, Gatto I, Brusca N, De Vito C, Gargano L, Centanni M. Thyroxine softgel capsule in patients with gastric-related T 4 malabsorption. Endocrine. 2015;49(1):51–7. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0476-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ross JS, Rohde S, Sangaralingham L, Brito JP, Choi L, Dutcher SK, et al. Generic and brand-name thyroid hormone drug use among commercially-insured and medicare beneficiaries, 2007–2016. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(6):2305–14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-02197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benvenga S, Carlé A. Levothyroxine Formulations: Pharmacological and Clinical Implications of Generic Substitution. Adv Ther. 2019;36(Suppl 2):59. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vita R, Fallahi P, Antonelli A, Benvenga S. The administration of L-thyroxine as soft gel capsule or liquid solution. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11(7):1103–11. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.918101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 118 kb)