INTRODUCTION

Race and ethnicity are complex social constructs whose measurement and subsequent classification have ramifications for how health systems track and address racial/ethnic health disparities.1, 2 Racial/ethnic classifications are proxies for social contexts, lived-experiences, and relationships that influence healthcare experiences including experiences with racism, cultural proficiency, and communication barriers.3 Some research suggests that racial/ethnic minorities, including Hispanics, report worse provider satisfaction and communication, and posit that cultural and language barriers in healthcare settings contribute to these disparities.3–5

Research on racial/ethnic differences in patient experiences often combines race and ethnicity into a single measure. However, the relationship between Hispanic ethnicity and patient experience for patients of different races is unknown, which has implications for whether combined race/ethnicity categories accurately capture differences. We examined whether the relationship between race and patient experience differed by Hispanic ethnicity among Veteran Health Administration (VHA) users of different races.

METHODS

We used data from the 2014 and 2015 Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP) Patient-Centered Medical Home Survey, conducted by the VHA Office of Reporting, Analytics, Performance, Improvement and Deployment. SHEP, based on the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CAHPS) survey, includes validated patient healthcare experience measures.6 Our sample included a stratified random sample of VHA users with at least one VHA primary care visit in 2013–2015 (n = 551,992) drawn from VA care facilities nationwide. Self-reported patient race (White, Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN), Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NH/OPI)) and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic) came from SHEP. Outcomes were two domains of patient experience with primary care: a six-item composite provider communication measure (percent of items receiving top rating versus not) and a single-item overall provider rating measure (high [≥ 9] on 0-to-10 scale versus not high [≤ 8]).

We assessed whether patient experiences differed between Hispanics and non-Hispanics within each race group with multivariate linear and logistic regression models that included a product term between patient race and Hispanic ethnicity, while controlling for patient age, sex, self-rated health, and education. For each race group, we used the fitted model to compute (1) predicted probability of a high provider rating for Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients separately; (2) mean provider communication rating for Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients separately; and (3) difference in probability or mean rating between Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients.

RESULTS

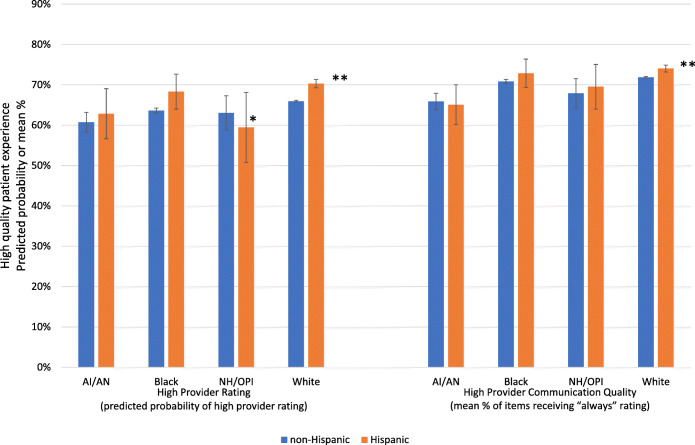

Within race groups, the proportion identifying as Hispanic ranged from 2.4% (Blacks) to 17.0% (AI/ANs) (Table 1). After controlling for individual-level characteristics, Hispanic Whites were more likely to report high provider ratings (predicted probability difference = 4.4%, p value < 0.001) and better provider communication (mean difference = 2.2%, p value < 0.001) than non-Hispanic Whites (Fig. 1). By contrast, Hispanic NH/OPIs were less likely to report higher provider rating than non-Hispanic NH/OPIs (predicted probability difference = 3.6%, p value = 0.088). We did not find differences by Hispanic ethnicity for provider rating or provider communication quality in other race groups (all p values ≥ 0.280).

Table 1.

VHA Sample Characteristics

| White | AI/AN | Black | NH/OPI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | |

| Sample size | 21,859 | 439,515 | 942 | 4,596 | 1,349 | 55,021 | 377 | 1,972 |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 65.9 (13.1) | 69.4 (11.4) | 62.3 (11.6) | 64.2 (10.9) | 62.6 (13.4) | 62.5 (11.9) | 62.1 (11.8) | 61.9 (11.9) |

| Sex, % | ||||||||

| Female | 4.9 | 4.1 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 9.2 | 9.9 | 4.8 | 5.9 |

| Self-rated health, % | ||||||||

| Excellent | 5.3 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 6.9 | 4.1 | 5.6 | 4.1 |

| Very good | 17.9 | 21.6 | 15.0 | 16.8 | 18.6 | 16.1 | 15.3 | 17.0 |

| Good | 34.9 | 38.3 | 31.2 | 33.0 | 30.2 | 36.6 | 33.5 | 35.5 |

| Fair | 32.2 | 27.5 | 33.8 | 33.8 | 35.3 | 34.6 | 32.7 | 31.1 |

| Poor | 9.7 | 7.7 | 14.6 | 12.4 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 12.9 | 12.4 |

| Educational attainment, % | ||||||||

| ≤ 8th grade | 4.2 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 0.7 |

| Some high school | 7.1 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 8.2 | 6.0 | 7.7 | 4.2 |

| High school graduate or GED | 29.2 | 35.3 | 28.6 | 29.8 | 29.6 | 31.7 | 34.4 | 33.0 |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 40.2 | 36.2 | 46.1 | 43.4 | 35.2 | 43.5 | 41.1 | 45.2 |

| 4-year college graduate | 10.8 | 9.5 | 8.8 | 8.0 | 15.0 | 9.0 | 7.2 | 9.8 |

| > 4-year college degree | 8.6 | 9.5 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 7.1 |

| Patient experience | ||||||||

| Provider rating1, % | ||||||||

| High rating | 68.5 | 69.2 | 64.4 | 63.3 | 70.9 | 66.0 | 65.7 | 65.3 |

| < High rating | 31.5 | 30.8 | 35.6 | 36.7 | 29.1 | 34.1 | 34.3 | 34.7 |

| Provider communication quality2, mean % (SD) |

72.3 (31.2) |

74.4 (36.2) |

66.8 (40.3) |

67.4 (39.8) | 75.4 (35.1) | 72.5 (37.4) | 70.7 (38.4) | 69.1 (39.5) |

Notes. AI/AN denotes American Indian/Alaska Native; NH/OPI denotes Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander

1Provider rating based on a 0 (worst) to 10 (best) scale, dichotomized as high rating of 9–10 versus < high rating of 0–8.

2Percent of questions assessing provider communication quality to which respondents answered always (versus never, sometimes, usually): how well provider listened, showed respect, explained well, spent enough time, gave information that was easy to understand, and knew about patients’ medical history

Figure 1.

High quality patient experience by race and Hispanic ethnicity—adjusted predicted probabilities and means. Notes: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05 for ethnicity-by-race interaction. Provider rating based on a 0 (worst) to 10 (best) scale, dichotomized as high rating of 9–10 versus < high rating of 0–8. Provider communication quality based on percent of questions to which respondents answered always (versus never, sometimes, usually): how well provider listened, showed respect, explained well, spent enough time, gave information that was easy to understand, and knew about patients’ medical history. Models adjusted for age, sex, self-rated health, and educational attainment. Predicted probabilities and contrasts calculated at mean.

DISCUSSION

We found few differences in patient experience by Hispanic ethnicity within race groups. However, there were exceptions. Among Whites, those of Hispanic ethnicity reported higher provider ratings and better provider communication quality. Non-Hispanic NH/OPIs reported greater provider satisfaction than their Hispanic counterparts. While previous research notes that self-identified Hispanic ethnicity may indicate acculturation and language barriers,4 our findings among White and NH/OPI VHA users suggest that Hispanic identity’s influence on patient experience is more complex for these groups. Specifically, the Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic association with patient experience differed across race groups. Additionally, in our sample of VHA users, NH/OPI had the second largest proportion of individuals who identified as Hispanic (16%), so understanding the multifaceted interplay between race and Hispanic ethnicity may be particularly important for this group.

Study limitations included having too few Asian and multiple race patients to study in this sample, limited power to detect differences by Hispanic ethnicity for smaller race groups, and limited generalizability to non-VHA users (e.g., VHA users may have better healthcare experiences and higher English proficiency). Additionally, these differences are small, and their clinical meaning is uncertain.

VHA and other federal agencies should consider whether and how to combine racial and ethnic categories in ways to accurately capture patients’ experiences. While current categories may suffice for reporting and monitoring purposes,2 it is also important to qualitatively understand how individuals self-identify by and experience race and ethnicity, and how these identities shape their healthcare experiences.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted through the Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Health Equity (OHE)–Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Center, funded by the VA OHE and QUERI (Grant No. PEC-15-239). Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP) Patient-Centered Medical Home Survey data were obtained through a data use agreement with the VHA Office of Reporting, Analytics, Performance, Improvement & Deployment (RAPID) (10A8). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or of the U.S. government.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Magaña López M, Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Yang L, Wallen GR. Discrepancies in Race and Ethnicity Documentation: a Potential Barrier in Identifying Racial and Ethnic Disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;4(5):812–818. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mays VM, Ponce NA, Washington DL, Cochran SD. Classification of race and ethnicity: implications for public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24:83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper LA, Powe NR. Disparities in patient experiences, health care processes, and outcomes: the role of patient-provider racial, ethnic, and language concordance. New York: Commonwealth Fund New York; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morales LS, Cunningham WE, Brown JA, Liu H, Hays RD. Are Latinos Less Satisfied with Communication by Health Care Providers? J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(7):409–417. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.06198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oguz T. Is Patient-Provider Racial Concordance Associated with Hispanics' Satisfaction with Health Care? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;16(1):31. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16010031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholle SH, Vuong O, Ding L, et al. Development of and Field Test Results for the CAHPS PCMH Survey. Med Care. 2012;50:S2–S10. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182610aba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]