Abstract

The outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19) disease is overwhelming resources, economies and countries around the world. Millions of people have been infected and hundreds of thousands have succumbed to the virus. Research regarding the coronavirus pandemic is published every day. However, there is limited discourse regarding societal perception. Thus, this paper examines blame attribution concerning the origin and propagation of the coronavirus crisis according to public perception. Specifically, data were extracted from the social media platform Twitter concerning the coronavirus during the early stages of the outbreak and further investigated using thematic analysis. The findings revealed the public predominantly blames national governments for the coronavirus pandemic. In addition, the results documented the explosion of conspiracy theories among social media users regarding the virus’ origin. In the early stages of the pandemic, the blame tendency was most frequent to conspiracy theories and restriction of information from the government, whilst in the later months, responsibility had shifted to political leaders and the media. The findings indicate an emerging government mistrust that may result in disregard of preventive health behaviours and the amplification of conspiracy theories, and an evolving dynamic of blame. This study argues for a transparent, continuing dialogue between governments and the public to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Covid–19, Blame, Social media, Pandemic, Twitter

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a cluster of atypical pneumonia cases were reported in Wuhan, China. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the virus that was identified as responsible for the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). The majority of the patients diagnosed with this atypical pneumonia had connections to the Huahan Seafood market in China. Some reports indicated early rapid spread, with cases doubling every 7.5 days (Valencia, 2020). It is one of the seven human transmissible coronaviruses, most likely originating from the bat coronavirus that was transmitted to humans through an intermediate host, likely the pangolin (Gralinski & Menachery, 2020). On January 1st, 2020, the seafood market was closed and decontaminated while countries with travel links to China went on high alert for potential travellers with unexplained respiratory disease (Cheng & Williamson, 2020). The initial reporting of cases occurred during the Chinese New Year, at the time of the largest population movement in.

China. On January 23rd, 2020, the Chinese government implemented a strict lockdown of Wuhan, followed by several nearby cities. Furthermore, airports and railway stations implemented screening measures to detect potentially ill travellers (Roosa et al., 2020). On January 30th, 2020, cases of coronavirus began to spread around the world and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency of international concern. It is estimated that the basic reproduction number (R0) is 2.2, which means that on average, each infected person spreads the infection to an additional two people. The rapid rate of infection has led several countries to institute restrictions on travel toward slowing the spread of the disease internationally. On March 11th, 2020, the WHO declared the outbreak of SARS-Cov-2 a pandemic (Fauci et al., 2020). As of September 2020, more than 28 million cases of coronavirus and over 900,000 deaths have been reported globally (http://worldometers.info/coronavirus).

The coronavirus pandemic has overwhelmed resources and countries all around the world due to its severity. Researchers have connected on social media to compare updated data and pinpoint yet undiscovered information about the outbreak. This rapid sharing of information enabled laboratories to develop diagnostic tests within weeks of the discovery of the pathogen (Cheng & Williamson, 2020). The ability to share news updates and data in real time with public health officials and researchers worldwide promises an advancement in the response to outbreaks (Gralinski & Menachery, 2020).

1.1. The online construct of an epidemic

The crucial role of social media during epidemics and emerging infectious diseases has been effectively demonstrated in research (Shahid et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2018), and even traditional media are increasingly accessed through social media platforms (Yang et al., 2013). It is imperative to expand the analytical nucleus and include social media as a corpus in the study of epidemics (Roy et al., 2020). Several studies that have analysed social media during epidemics focus on digital epidemiology, using publicly available data to detect and monitor disease outbreaks (Culotta, 2010; Hossain et al., 2016; Velasco et al., 2014)l and social media analysis can predict outbreaks rather than solely monitor the crisis (Samaras et al., 2020). Some researchers have explored misinformation and rumours circulating on the media regarding epidemics, highlighting the importance for the analysis of such discussions to counteract the spread of false information (Carter, 2014; Sharma et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2013). Moreover, several epidemics studies consider social media a mechanism through which public perceptions are accessible. Specifically, social media analysis harvests public perception about public health issues and explores users’ understanding of epidemics to adjust online communication strategies and policies (Bragazzi et al., 2017; Nielsen et al., 2017; Roy et al., 2020; Shahid et al., 2020).

1.2. Social media discourse of Covid–19

The Covid–19 outbreak is rapidly progressing worldwide, and much research regarding the pandemic is published every day. In the early stages of the outbreak, availability of public online databases is important to encourage research and provide robust evidence to guide interventions. Social media captures real-time information, capable of reconstructing the progression of the outbreak (Sun et al., 2020), and provides an accurate reflection of the disease during the crisis (Massaad & Cherfan, 2020). Several studies have effectively employed social media to provide accurate real-time predictions of the coronavirus pandemic cases (Jahanbin & Rahmanian, 2020; Li, Bailey, et al., 2020a, 2020b; Qin et al., 2020; Roosa et al., 2020), and help the government and health department identify high risk patients and accelerate emergency responses (Huang et al., 2020).

Conversely, numerous studies focused on the negative aspects of social media use during the crisis. Whilst addressing the urgency of public health measures to combat the outbreak, some studies focused on the spread of fear and panic throughout social media (Depoux et al., 2020; Jalali & Mohammadi, 2020; Radwan & Radwan, 2020). Further, information and misinformation sharing during the crisis constitutes the largest corpus of social media coronavirus research thus far (Chrousos & Mentis, 2020; Hua & Shaw, 2020; Jayaseelan et al., 2020; Kouzy et al., 2020; Kulkarni et al., 2020; Li, Bailey, et al., 2020a, 2020b; Pennycook et al., 2020; Radwan & Radwan, 2020). Several studies highlight the significance of inaccurate statistics, misinformation and rumours spreading over social networks that result in fear mongering, panic, conspiracy theories (Jalali & Mohammadi, 2020), and potentially affect the mental health of social media users (Gao et al., 2020). Overall, social media research regarding the current global health emergency scarcely explores the public's perceptions.

1.3. Twitter: epidemic communication centre

The platform Twitter has become a central communications channel during the coronavirus crisis (Kullar et al., 2020). Twitter is a social networking and micro-blogging service that has over 330 million active users as of 2019. It enables registered users to express termed tweets through short messages, containing 280 characters (http://twitter.com). It is estimated that over 50 million tweets have been published concerning the coronavirus pandemic worldwide in the months of January to March 2020 (Chen et al., 2020). According to Kullar et al. (2020), Twitter is the most popular social media platform used for infectious disease information and communication. It allows for real-time sharing of scientific conferences and educational resources regarding diseases, enabling individuals worldwide to follow updates and stimulate discussion regarding health topics with professionals. The current study employs Twitter use to assess the most current and representative public perceptions regarding the outbreak.

1.4. Dynamics of blame in epidemics

Dynamics of blame are recurrently present during epidemics as the public attempts to make sense of the catastrophe by scrutinizing human actions that could have led to the spread of the disease (Farmer, 2006). According to Monroe and Malle (2019), blame emerged in human history as a social tool to regulate others' behaviour. Typically, it is constrained by requirements for evidence – that is, evidence that one's judgement is justified. This requirement motivates individuals to systematically process available information surrounding an incident to assess whether to amplify or mitigate blame.

Contrarily, rather than the methodical examination of available evidence to assign blame, research regarding previous epidemics suggests a recurring blame pattern concerning other collectives (Sparke & Anguelov, 2012). The story of disease emergence is most commonly expressed through the construct of communities of insiders and outsiders (Wald, 2008). Specifically, accusations against certain groups, outsiders, most commonly social “others”, have been a pattern throughout history, suggesting that “others” have been repetitively blamed for different epidemics (Roy et al., 2020). The traditional outbreak narratives involve the effort of distancing oneself from the “viral otherness” represented by “foreigners”, which narrativize the nation as the basis of health citizenship (Sparke & Anguelov, 2012).

During the Middle Ages, Jewish communities were accused of propagating the plague by poisoning wells (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015). In the 1980s and 1990s, heroin users and haemophiliacs were blamed for the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Hays, 2009). In 2003, during the SARS outbreak in New York City, Chinese immigrants were stigmatized and blamed by other residents in response to the uncertainty surrounding the epidemic. In the Zika epidemic, the disease was associated with immigrants from Central and South America; the blame for the virus infection was placed on individuals from specific nationalities (Linde-Arias et al., 2020). During the Ebola epidemic, the American narrative involved phrases such as “Ebola is African”, often positioning a group of people as other to differentiate “us” and “them” (Monson, 2017). Historically, the justification of cultural blame obscures the legitimate causes of epidemics and naturalizes health inequalities in marginalized populations (Eichelberger, 2007).

Divergent research regarding blame during epidemics portrays collective perceptions as dramatized roles. Particularly, the public perceives the epidemic through introducing characters such as heroes, villains and victims (Mayor et al., 2013). In contrast to previous research that consists of traditional scapegoats (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015), the affected population is most frequently regarded as the “victim”. Moreover, the representations of the “villains” comprise of the private corporations like pharmaceutical companies and the media (Wagner-Egger et al., 2011). According to Mayor et al. (2013), the negative presentations of crucial collectives including pharmaceutical industries and the media during an outbreak may be catastrophic as public mistrust in authorities could prevent compliance regarding limiting disease spread.

1.5. Blame attributes on social media

Attribution of blame is a natural human response to unexpected events to “make sense” of the world (Hewstone, 1989). Social media offers a dynamic portrayal of public perception after catastrophic events (Canales et al., 2019).

Previous research has explored blame attributions during catastrophic events on social media, including the Flint water crisis in the United States (Bisgin & Havens, 2018), and following hurricane disasters (Canales et al., 2019). However, there has been limited research on the dynamics of blame on social media platforms during global health emergencies. In 2015, Atlani-Duault and colleagues explored the accusatory dynamics on social media during the rise of the H1N1 epidemic. The authors developed the concept ‘figures of blame’, arguing that accusations against certain groups are often historically recurring and are now expressed through social media. Furthermore, Roy et al. (2020) analysed the main groups accused of causing and propagating the Ebola epidemic on Twitter. The findings suggested a tendency to attribute blame most frequently to ‘near-by’ figures, including local authorities rather than ‘distant’ figures, such as generalized figures of otherness as previous research indicated (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015). Additionally, Roy et al. (2020) argued for the existence of an evolution in online blame, suggesting there was a different direction of attributing blame at the early stage of the Ebola epidemic in comparison to the peak of the epidemic, suggesting blame attribution is altered in response to mitigating information from the environment (Monroe & Malle, 2019). Regarding the coronavirus crisis, Barreneche (2020) aimed to highlight the re-emergence of the blame cast on “others” regarding the pandemic. The study concluded that several “others” have been constructed to articulate an explanation for the spread of the virus outside of social media. The scarce research on the concept of blame attribution during epidemics on social media appears divided, some arguing for a recurring concept of “otherness” (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015), while others cast blame upon authorities, such as governments (Roy et al., 2020). Thus, this study examines blame attribution in social media conversations during the coronavirus pandemic.

In this paper, we aim to fill the gap in knowledge regarding blame attribution and contribute to the current literature on social media and the coronavirus pandemic. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the attribution and evolving dynamics of online blame according to social media users during the coronavirus pandemic. For the purpose of this study, blame encompasses accusatory attributes for both the origin and the propagation of the outbreak. This research aims to identify the core figures and agents of blame present in Twitter conversations and analyse the implications of the emerging discourse to further contribute to communication strategies toward the public.

2. Method

The social platform Twitter was utilized to obtain data regarding blame on social media during the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. The current study employed Internet-Mediated Research (IMR) involving the remote acquisition of data collected unobtrusively. Specifically, non-reactive public data available on Twitter have been used. The nature of this process restricts the participants’ awareness since the partakers do not knowingly engage in a study. To ensure research ethics, the following ethics considerations were examined. According to the British Psychological Society (2017), IMR studies must respect autonomy and privacy of the individuals online. Privacy warrants additional consideration due to the unclear status of different sources of online information. In the current study, the data derived from Twitter were deemed public, both to the individual and the social platform, as the terms and conditions of service stated that public posts are considered to be in the public domain. Subsequently, the direct usage of quotes from the Twitter posts could potentially lead to identifying characteristics and reveal sensitive information regarding the users. Therefore, to ensure participant confidentiality, the data analysed in the paper will be presented in a paraphrased manner. Additional considerations regard copyright issues and ownership of public data. In this case, permission from the social media platform was unwarranted as terms and conditions specify that an unlimited amount of tweets can be distributed for the purpose of research (http://twitter.com).

2.1. Data collection

The most efficient way to obtain Twitter content involves using the application programming interface (API) to obtain Tweet IDs, i.e., numerical codes of each individual message that contains the post and any other public information, such as date, user or location, ensuring data comprise of the most current information directly from Twitter.

(http://developer.twitter.com). At the time of writing, the coronavirus pandemic outbreak has acutely affected countries worldwide. Consequently, companies and researchers have provided large amounts of online data concerning the coronavirus pandemic to the public. In March 2020, the first multilingual coronavirus Twitter dataset was available to the research community. Chen et al. (2020) published Twitter data in the form of Tweet IDs that had been collected since January 22nd, 2020, for the advancement of research worldwide. The dataset included tweet IDs that were extracted from the Twitter API and gathered information under keywords related to the pandemic. Table 1 illustrates the specific keywords and the words and phrases that were later incorporated in their search.

Table 1.

Keywords in online coronavirus social media database (Chen et al., 2020).

| Keyword |

Tracked Since |

|---|---|

| Coronavirus | 1/22/2020 |

| Koronavirus | 1/22/2020 |

| Corona | 1/22/2020 |

| CDC | 1/22/2020 |

| Wuhancoronavirus | 1/22/2020 |

| Wuhanlockdown | 1/22/2020 |

| Ncov | 1/22/2020 |

| Wuhan | 1/22/2020 |

| N95 | 1/22/2020 |

| Kungflu | 1/22/2020 |

| Epidemic | 1/22/2020 |

| Outbreak | 1/22/2020 |

| Sinophobia | 1/22/2020 |

| China | 1/22/2020 |

| Covid-19 | 2/16/2020 |

| Corona Virus | 3/02/2020 |

| Covid | 3/06/2020 |

| Covid19 | 3/06/2020 |

| Sars-cov-2 | 3/06/2020 |

| COVID-19 | 3/08/2020 |

| COVD | 3/12/2020 |

| Pandemic | 3/12/2020 |

Accordingly, the online Twitter database was utilized and the tweet IDs concerning the coronavirus pandemic were acquired from January 22, 2020 until March 20, 2020. At the time the online coronavirus Twitter database was published, an approximate 50,000,000 tweet IDs were reported (Chen et al., 2020). However, as the dataset is a livestream, constantly renewing information as it is published, the dataset for the present research includes 71,373,757 tweet IDs. To acquire the Tweet information from the Tweet IDs, data hydration (i.e., importing data into an object, a dormant data point, such as a numerical Tweet ID) is necessary. The Tweet IDs may be utilized to extract the pre-existing data, in this case the original Twitter post. Thus, hydration is the process of populating the object, the Tweet ID, with data from the Twitter's database (http://github.com).

The most common software to hydrate such data is “Hydrator” which requires input of the Tweet IDs and produces output files containing all the Tweet's public data, including text, user, date and location. The hydrator software was employed to hydrate the Tweet IDs into factual data. The data acquired through hydration reflect the current status of this information. Therefore, any data that the users have deleted or switched to private settings cannot be obtained through this procedure. Despite the loss of potentially valuable data, this method involves an additional ethics consideration for the participants of this study. Online communication is often considered to be in the public domain and this dataset was deemed public in the terms of service of the social platform. However, there is a level of ambiguity at times when data have been previously public, and the individual alters the status of the data (British Psychological Society, 2017). During the data collection of this study, several months had preceded the extraction of the information, therefore providing the users of the platform with ample time to reconsider and permanently delete or alter the public status of their statements, thus ensuring their withdrawal from the study.

2.2. Data analysis

The original Twitter database from the 22nd of January to the March 20, 2020 regarding the coronavirus comprised 71,373,757 tweet IDs. Following the hydration process, the tweets were reduced to 62,145,097 Twitter posts. Moreover, language was used to limit the analysis to tweets in English, further decreasing the sample to 42,791,395 tweets. Fig. 1 portrays the variances among Twitter posts before the hydration process, i.e., the original number of posts concerning the pandemic, the Twitter posts after the hydration process and the Twitter posts in English concerning the pandemic worldwide.

Fig. 1.

Number of Twitters Posts Regarding the Coronavirus Pandemic.

Thus, the sample at this stage of analysis consisted of 42,791,395 tweets. Evaluating blame attribution poses a challenge, as blame in text may be expressed through complex linguistic structures that often use implicit language (Atkeson & Maestas, 2012). The most efficient way to identify blame in text is through human coders, however due to the volume of the data this would be very costly. Therefore, a randomized selection of a reduced sample was favoured to perform thematic analysis and identify the perceived blame attributions by social media users. Thematic analysis was employed as it is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns within data (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

In contrast to more frequent usage of thematic analysis examining interview data, this study utilizes Twitter posts that already contain limited information due to character limitations, and therefore do not fit into a pre-existing coding frame (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Prior research has also applied thematic analysis to identify blame attributions on social media as this approach offers an accurate identification of blame in text (Roy et al., 2019; Mayor et al., 2013).

The selection of the sample consisted of tweets deriving from different days within the dataset to ensure capturing a potential evolution in blame, as previous research suggests a progression of blame attributes during an epidemic (Roy et al., 2020). The current study utilized a randomly selected, reduced data sample to assign attributes of blame. However, as the complex nature of blame expression in text suggests numerous implicit and unidentified complex linguistic structures, this study did not use keywords to filter data. The sample comprised of hundreds of Twitter posts from every day of the study period, resulting in 9,000 tweets coded using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo (https://www.qsrinternational.com).

This study adheres to the phrases of thematic analysis specified by Braun and Clarke (2006) and as such the analysis was conducted in five stages. Firstly, the randomly selected sample of 9,000 Twitter posts was read repeatedly to ensure immersion and identify potential patterns across the dataset. At this stage, the themes were abstract and undetermined, however the evolution of blame attribution from January to March was evident as users accused certain figures only within a specific time frame. Subsequently, the dataset was initially coded; this stage was utilized to limit the data to Twitter posts that attributed blame. Furthermore, the tweets that did not attribute blame were assigned the “No Blame” label, the tweets that used the coronavirus related keywords to promote services were assigned “Non Applicable”, while the tweets that were identical and derived from the same user were named “Repetition”. The analysis yielded 6,935 (77%) tweets that did not assign blame, 407 (5%) tweets that were non-applicable and 264 (3%) repetitions. In the overall sample, 1,395 (16%) Twitter posts assigned blame.

Subsequently, the coded Twitter posts that attributed blame were sorted into potential themes using visual representations, brief descriptions of potential themes on paper that resulted in the following overarching themes: (1) Conspiracy Theories, (2) Border Control, (3) Media, (4) Global Health Authorities, (5) Food Markets, (6) National Governments, (7) Health Care.

Institutions, (8) Quarantine Measures, (9) Political Leaders, (10) Censorship of Information, (11) Fake News, (12) Xenophobia, and (13) Individuals Spreading the Virus Deliberately. In the next stage, the themes were revised to distinguish themes that could be separated or merged. For instance, there were several themes containing different social groups accused of spreading the virus that were later merged into the theme “Social Groups”. In addition, the sample of 1,395 blame attributions was repeatedly analysed to ensure the accurate classification in themes. The identified themes and subthemes at this stage were: (1) Conspiracy Theories, (2) Media (Fake News), (3) Health Authorities, (4) Consumption of Meat, (5) National Governments (Quarantine.

Measures, Healthcare Costs, Border Control), (6) Political Leaders, (7) Censorship of Information, and (8) Social Groups.

Lastly, the themes were reviewed to accurately determine the scope of each one and refine and rename the themes. This analysis merged the themes into agents of blame rather than attributes. Specifically, the themes represent figures the social media users blame for coronavirus. Themes were further merged to identify the agents behind the figures. Accordingly, censorship of information and political leaders belong under the agency of the government. Consequently, this study concluded with the following themes: (1) National Governments, (2) Conspiracy Theories, (3) Social Groups, (4) Media, (5) Meat Consumption and (6) Health Authorities.

Any theoretical framework carries with it several assumptions about the nature of data, and what they portray (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This study acknowledges that the dataset represents the perception of social media users regarding blame attribution, and that the prevalence demonstration of such attributions is limited in this amount of data within a social platform.

3. Results

The most prominent perceived figures of blame in the Twitter posts (n = 1395) from the.

22nd of January until the March 20, 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic were: (1) National.

Governments (n = 920, 66%); Conspiracy Theories (n = 175, 13%); Media (n = 103, 7%); Social Groups (n = 87, 6%); Meat Consumption (n = 61, 4%) and Health Authorities (n = 49, 4%). Table 2 illustrates the separate subcategories of each figure of blame.

Table 2.

Thematic categories in twitter posts.

| Figures of Blame | Twitter Posts |

|---|---|

| National Governments | 920 (66%) |

| Political Leaders | 234 (25%) |

| Censorship of Information | 209 (23%) |

| Border Control | 54 (6%) |

| Pandemic Fund Reduction | 31 (3%) |

| Healthcare Costs | 21 (2%) |

| Conspiracy Theories | |

| Others (i.e., Spies, New World Order, Hoax) | 175(12%) |

| Laboratory Experiment | 85 (49%) |

| Bioweapon | |

| 5G | |

| Media | |

| Fake News | 46 (26%) |

| Social Groups | 36 (21%) |

| Xenophobia | 8 (5%) |

| Purposeful Contamination | 103 (7%) |

| Meat Consumption | 21 (20%) |

| Exotic Animal Trade | 87 (6%) |

| Health Authorities | |

| CDC | 68 (78%) |

| WHO | 19 (87%) |

| 61 (4%) | |

| 31 (51%) | |

| 49 (3%) | |

| 30 (61%) | |

| 19 (39%) | |

3.1. National governments

The most frequent accusations of blame were directed towards governments (n = 371, 40%). Specifically, the national governments that were most commonly held accountable comprised of the United States (n = 204, 22%) and China (n = 167, 18%). Respectively, the United.

States were arraigned for the cost of the existing healthcare system (n = 21, 2%), whereas China's government was blamed for the censorship of information (n = 209, 23%), which, according to social media users, could have advanced the virus propagation.

The US government was directly accused of a haphazard approach to dealing with the pandemic or lack thereof: “All the warnings for the Coronavirus but the US government has no plan!!” (Twitter Post February 15, 2020). Furthermore, the US was blamed for the current healthcare system and specifically the tremendous costs for coronavirus testing during the crisis that led to further spread of the virus: “I despise this country [US]. 3000 dollars to test for coronavirus, because they rejected WHO's tests” (Twitter Post March 3, 2020).

The Communist Party of China (CPC) was accused regarding the origin of the coronavirus: “China's Communist Party has put the entire world in danger, because of the coronavirus!” (Twitter post February 13, 2020) and the spread of the virus: “China's behaviour in addressing the pandemic involved serious delays for which they should take responsibility!” (Twitter Post March 14, 2020). Consequently, China was most frequently accused of censoring and altering information regarding the virus: “If China allowed free speech, coronavirus crisis would not exist!!” (Twitter Post February 10, 2020) which in the public's view resulted in the spread of the virus: “The Chinese government's lying has caused the coronavirus epidemic to spiral out of control” (Twitter Post February 20, 2020).

The political leaders that were explicitly accused were Donald Trump (n = 89, 10%), most notably for the elimination of the pandemic response team (n = 31, 3%), and Xi Jinping who was held accountable for mishandling the coronavirus outbreak (n = 17, 2%). President Trump was often explicitly criticized of inadequacy regarding the pandemic response: “The public health would be safer if we isolate Donald Trump,” (Twitter Post March 5, 2020) and of faultily downplaying the pandemic threat: “From the very start, Donald Trump has diminished the importance of the coronavirus crisis, portraying it as if it is a foreign threat that can easily be dealt with!” (Twitter Post March 6, 2020). Some social media users especially attributed blame to the President for the reduction of funding to the pandemic response, specifically, the pandemic response protocols that were orchestrated in 2018: “President Obama created an excellent process for epidemics after Ebola and Trump destroyed it by cutting all the funding and firing the people on the pandemic response team! Donald Trump also cut the funding of the CDC in 2018” (Twitter Post March 6, 2020).

The leader of the CPC, Xi Jinping, was accused of mismanaging the viral outbreak: “Xi Jinping was responsible for the containment of the coronavirus and there is a disappointing trail of errors and lies” (Twitter Post February 17, 2020) and suppressing pandemic-related information: “If only Xi Jinping had acted as decisively in addressing the coronavirus pandemic as he did to suppress it” (Twitter Post February 17, 2020).

Lastly, many social media users who blamed national governments expressed the pandemic crisis outbreak in terms of border politics (n = 54, 6%). They explicitly targeted governments for a perceived lack of border control, which, in their view, resulted in the dissemination of the virus: “The world's a joke. 2000 people from Wuhan are travelling across to UK without border restrictions” (Twitter Post January 26, 2020), and they frequently demanded their individual governments to close borders and deny flights, most often from China: “Please start a movement to stop all flights from China and close the borders!!” (Tweet February 12, 2020).

Conclusively, the governments were arraigned for mismanaging the coronavirus pandemic, including respective political leaders, the pandemic response and border control. National governments were targeted for the origin of the virus, the outspread of the virus and in some cases the conditions prior to the crisis that were amplified during the pandemic.

3.2. Conspiracy theories

The second most often recurring pattern in the data referred to elaborate conspiracy theories regarding both the pandemic origin and outspread (n = 175, 13%). Due to the number of divided statements in this theme, the most common category is termed Others (n = 85, 49%), referring to several diverse theories such as “spies”, “agents” and an organization called the.

“New World Order” as culpable for the coronavirus crisis. Additionally, some users identified the source of the pandemic to be a laboratory experiment (n = 46, 26%) and an elaborate bioweapon (n = 36, 21%), whereas fewer users accused 5G internet towers (n = 8, 5%).

Numerous users understood the coronavirus pandemic through intricate conspiracy theories, such as: “Chinese agents have infiltrated the US research institutions through China's Thousand Talents Plan to depopulate the US!” (Tweet February 17, 2020), “The New World Order is succeeding in its plan to depopulate the world!!!” (Tweet February 11, 2020). Others questioned the existence of the virus altogether: “The coronavirus is a hoax to hurt Trump!” (Twitter Post 8 March 2, 0202).

Several individuals identified the source of the virus as a laboratory in China.

Specifically, users supported the view that the virus was engineered in a lab and it was released into the world: “The coronavirus was conceived in a laboratory by scientists using well known genetic vectors!” (Tweet February 4, 2020). Furthermore, some users associated the laboratory theory with the Wuhan animal markets: “Coronavirus did Not begin at the Wuhan animal market; the secret laboratory of China is next to it!” (Tweet February 16, 2020), claiming that animal markets were utilized to transfer infected laboratory animals: “The laboratory animals from the secret lab were sold to the animal markets disguised as exotic animals for money!” (Twitter Post February 22, 2020).

Moreover, users regarded the virus as an engineered, destructive bioweapon that originated in China: “This coronavirus clearly did not come from someone who consumed a bat. This is a bioweapon. China released it and the governments are not aware of the danger, so they are being proactive” (Twitter Post January 26, 2020), and the US: “Coronavirus remains a US Bioweapon!!” (Tweet February 13, 2020). Some users accused internet services, explicitly 5G towers, of purposely harming individuals: “China started to establish 5G in Wuhan in October.

2019. 5G is proven to destroy your immune system!!” (Twitter Post February 11, 2020). Conspiracy theories comprised a remarkably large portion of the users’ blame perceptions, including sporadic schemes and more actualized theories of origin, such as laboratories, bioweapons and internet towers.

3.3. Media

Several users attributed blame to media sources during the coronavirus pandemic (n = 103, 7%). Most often the media were criticized for falsifying information: “I am so exhausted of the media reporting about these coronavirus lies” (Tweet March 5, 2020) and fear mongering: “The mainstream media are trying to cause terror over the coronavirus!” (Twitter Post March 9, 2020).

A number of users expressed the belief that the media reports of coronavirus were “fake news” (n = 21, 20%). In contrast to the conspiracy theories that viewed the virus as a “hoax”, here individuals voiced the opinion that the media is responsible for the spread of the “fake” virus:

“Let us be honest. All the panic for the coronavirus is caused by the media spreading fake news” (Twitter Post March 9, 2020). Consequently, the media were frequently targeted during this crisis, most notably for misinformation of the public and the deliberate spread of false news.

3.4. Social groups

Social groups were accused of both causing and accelerating the spread of the coronavirus pandemic (n = 87, 6%), including xenophobic statements directed most often at the affected population (n = 68, 78%), and individuals purposefully spreading the virus (n = 19, 22%).

Numerous individuals expressed xenophobic or prejudiced remarks toward the affected and infected population at the time, most frequently of Chinese origin: “Coronavirus is a Chinese illness and for this reason do not go near Chinese people” (Twitter Post January 30, 2020), while some individuals accused people of Chinese origin of purposefully spreading the virus: “What is wrong with them [Chinese]? They are spreading the coronavirus on purpose! Curse the.

Chinese!” (Twitter Post January 30, 2020). Some users explicitly arraigned individuals who were perceived to deliberately spread the coronavirus (n = 19): “A woman is spitting and placing the tissues back into the box. Unbelievable” (Twitter Post February 2, 2020).

Furthermore, discriminatory statements were expressed explicitly against the Chinese without pinpointing evidence of deliberate contamination.

3.5. Meat consumption

Some social media users placed responsibility for the coronavirus in the widespread consumption of animals (n = 61, 4%). Approximately half of the users who blamed the pandemic on meat consumption explicitly accused the exotic animal markets in Wuhan, China (n = 31, 51%). Most frequently users exclaimed how the termination of meat consumption would have prevented the coronavirus pandemic worldwide: “Being vegetarian would not cause this coronavirus crisis!!” (Twitter Post March 14, 2020). Several users explicitly attributed blame for the coronavirus to the exotic wildlife animal markets in Wuhan: “If you are angry about the coronavirus, blame the legal dirty animal markets!” (Twitter Post February 4, 2020). Moreover, users appeared shocked and appalled at the wildlife market industry: “Disgraceful! Over 100 wild animals on sale in the wildlife menus in the markets of Wuhan!!” (Tweet January 23, 2020). Interestingly, some individuals on social media explicitly accused the consumption of meat and the wildlife animal markets, an unforeseen figure of blame in research thus far.

3.6. Health authorities

Lastly, some users castigated global and national health authorities for the coronavirus pandemic (n = 49, 3%), specifically, the World Health Organization (n = 19, 39%) and the Centres for Disease Control located in the United States (n = 19, 39%). The World Health Organization.

(WHO) was especially blamed for censoring information related to the virus: “The World Health.

Organization and its employees are covering and censoring information about the coronavirus under the orders of the Communist Party of China!!” (Twitter Post February 18, 2020). A few social media users accused the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US for limited testing of the virus:

“The CDC has more money and resources in comparison to most countries that have been performing thousands of tests. However, the CDC intentionally did not test anyone who did not come from China directly which is ridiculous since the virus has already spread to 15 other countries” (Twitter Post January 30, 2020).

Conclusively, health authorities were not directly accused of originating the virus, however the WHO was targeted for censoring valuable information and the CDC was accused of performing limited tests, actions that amplified the outspread of the pandemic, according to some users.

3.7. Evolution of blame

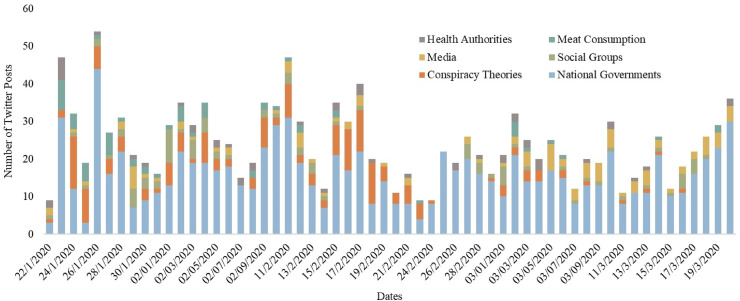

The most important perceived figures of blame regarding the coronavirus pandemic displayed a substantial progression in blame attribution. Specifically, while social media users seemed to blame national governments throughout the period examined in the study, conspiracy theories most frequently appeared in the early months of the crisis up until February with significantly fewer occurrences in March. Fig. 2 illustrates in detail the progression of blame attribution in the most notable agents of blame.

Fig. 2.

Evolution of Blame in Thematic Categories.

The identified subdivisions in the theme national governments illustrated significant differences in blame attribution during the time examined in the study. National governments sustained accusations throughout this period, whereas political figures were almost exclusively blamed in late February and March. In contrast, users blamed censorship of information from China most frequently in January and early February, once news of the virus began to spread. Fig. 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the evolution in blame attribution within the theme national governments.

Fig. 3.

Evolution of Blame in Thematic Category National Governments.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we sought to explore the perceptions of blame on social media during the coronavirus pandemic. The findings suggest that blame circulating on social media was most frequently directed at national governments. Conspiracy theories regarding the pandemic were the second most frequent figure of blame. Social media users also identified media sensationalism and misinformation as responsible for the propagation of the pandemic, and the restriction of information from health authorities, such as the WHO. Social groups were attributed blame less frequently in our sample compared to previous research (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015; Eichelberger, 2007; Monson, 2017), and comprised exclusively of people of.

Chinese origin. Notably, meat consumption and wildlife trade were attributes of blame that have not been indicated in research so far. Lastly, our results highlight a temporal progression of blame; that is, blame perception shifted along with the pandemic progression.

4.1. National governments

4.1.1. Government (Mis)Trust

Historically, distant groups have been in the centre of blame attribution during epidemics (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015; Broom & Broom, 2017; Mitman, 2014; Monson, 2017; Sinha & Parmet, 2016). In contrast, Wagner-Egger et al. (2011) argued that blame during health crises has evolved from distant groups to authorities and elites. In the same vein, studies have identified blame directed at political authorities and institutions, suggesting a dynamic of distrust toward governments (Linde-Arias et al., 2020; Roy et al., 2020). In 2013, Mayor et al. analysed the dynamic patterns of blame during the H1N1 pandemic. They discovered that as the epidemic progressed, the public conveyed divergent views concerning the authorities; more than half expressed distrust. The current study corroborates these findings. The accusation pattern divulges national governments as being in the forefront of responsibility. The loss of trust in government and health authorities has contributed to an increasing number of people questioning vaccines, delaying or refusing vaccination (Badur et al., 2020). Moreover, government mistrust may lead to the disregard of life-saving health measures and prevent the treatment of the current or a future global health crisis.

Progression of blame in national governments appears consistent with slight variations across the period examined in this study (Fig. 3) in contrast to previous research, which suggests a significant variation in accusation patterns towards national governments (Mayor et al., 2013; Roy et al., 2020). This discrepancy could be attributed to this study focusing on a fraction of time of the ongoing pandemic. Consequently the differences in evolution of blame can be attributed to the differences of the examined timeline.

4.2. Proximity of blame

The shift of blame from distant others to proximal figures has been noted in earlier research (Mayor et al., 2013; Roy et al., 2020), and our findings corroborate the divergence of blame attribution. It is possible that the tendency to blame others is mobilized earlier in the epidemic to explain the beginning of the outbreak and progressively evolves towards proximal figures as the threat of its possible arrival moves closer to one's country (Roy et al., 2020). In fact, Mayor (2013) argued that othering tendencies take place when the threat is geographically distant, and blame is transferred to local collectives when the threat is perceived to be imminent. However, in the current study, there was not a substantial difference between the progression of blame as recorded in prior studies. Social others were indeed more frequently held responsible in the early stages of the epidemic; however, governments were blamed throughout the timeline of this research. A possible explanation for the divergent results in blame progression is relevant to the geolocation of social media. Specifically, Twitter does not require users to share geolocation information publicly and the acquisition of such in this context would not be feasible. Therefore, while social groups are most often targeted in the early stages of the epidemic as previous research suggests (Mayor et al., 2013; Roy et al., 2020), this does not necessarily mean the threat was distant. For instance, it is possible that users who accuse other social groups reside in the same country as these social groups. In the same vein, it is impossible to anticipate whether the threat of the pandemic was already in the country of the social users who attribute blame to the government. The lack of geolocation information renders it impossible to identify whether proximity was relevant.

4.2.1. Censorship

Restriction of valuable information during the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic appeared to be a recurring accusation directed at governments and specifically the Communist Party of China. Shangguan et al. (2020) examined officially released information and social media sources to understand the cause of the crisis in relation to China. The research concluded that strict government control over information directly caused people to be unaware and unprepared for the coronavirus crisis. A prolonged approach was favoured to control information about the outbreak due to the political climate and the timing of the first outbreak, the Chinese New Year. The initial delays and slow response concerning the virus appear to have led to devastating consequences, as authorities and the public were not aware of the virus. This public information has stimulated the public's distrust toward the Chinese government and is in line with our findings. The strict censorship of information is theorized to have resulted in exacerbated mistrust, which could lead to conspiracy theories (Sharma et al., 2017). Censorship of information from the Chinese government was almost exclusively specified in the early stages of the pandemic according to our analysis (Fig. 3). One possibility for this temporal progression of blame is related to the geographic location of the virus. At the time that restriction of information had lessened in social media conversations, the coronavirus had spread to other countries and has therefore led to a global crisis.

4.3. Political leaders

Social media plays a central role in disseminating stories of blame, thus serving an indirect pathway to leadership accountability (Canales et al., 2019). During catastrophes, the public experiences intense mental states, even when the crisis is experienced through sources, such as social media (Atkeson & Maestas, 2012). In 2008, Maestas and colleagues examined public opinion in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The findings highlighted how social media information interacts with emotion in shaping a wide range of opinions regarding the government and political leaders. Shocking events in society encourage citizens to re-examine their understanding of the government and its leaders (Atkeson & Maestas, 2012). Similarly, our findings highlight accusatory comments towards political leaders during the crisis. The present research showed political leaders were held responsible for the propagation of the coronavirus exclusively since late February and March. This rapid increase in blame perception can be attributed to the virus having spread in other countries by late February. As fear of the virus became eminent, the public indicated government officials as responsible for the spread.

4.3.1. The theology of the wall

Some social media users focused on the protection of the country via filtering and excluding migrating bodies they identified to be a risk. The “desire for a wall” nourishes this protective fantasy in the emergence of frontier walls in the world (Roy et al., 2020). Historically, borders are central in the management of contagion, acting both as a geopolitical and symbolic barrier between the ill and the healthy. The global spread of disease provokes public reactions, in which fear of the disease can be incarnated as fear of “outsiders”, and the closure of borders is translated as creating a protective barrier (Abeysinghe, 2016). Thus, in line with previous research (Roy et al., 2020), the blame dynamic in our findings suggests that the public perceived their respective nations as an idealized space of protection. Withdrawal within the nation can decontextualize a crisis by portraying it as a border management issue without consideration for challenges that genuinely extend the spread of the disease.

4.3.2. The politics of a health crisis

In past crises, public health emergencies have appeared at the forefront of government management and strategic politicization. According to Greer and Singer (2017), during the Ebola epidemic in the United States, the democratic media devalued the epidemic, while the republican media concentrated on the outbreak to sway public opinion for an upcoming election. In this manner, the epidemic was quantified and framed for political gain at the time. Additionally, the mass media focused on framing the disease through domestic border politics. The border control measures during the epidemic in the US, the UK and Australia were narrated in the context of domestic party politics (Abeysinghe, 2016). Furthermore, the public's response to epidemic information and guidelines by the health authorities depended upon pre-existing partisanship. In other words, criticism of the health authorities' credibility among the public was driven by political affiliation (Greer & Singer, 2017). It is however unclear whether the public's perception was affected by the diverse coverage of the crisis or whether the polarized reporting of the Ebola outbreak affected the public's opinion. This strategic politicization of health crises worldwide decontextualizes the emergency by concentrating on political affiliation rather than monitoring the propagation of the outbreak. Conceivably, political favouritism during past health crises could explain the current and past results (Roy et al., 2020) of national governments in the centre of mistrust and blame attribution.

In conclusion, the most prominent figures of blame were national governments, corroborating prior research on blame perceptions during outbreaks (Roy et al., 2020). The growing mistrust in the government, the early restriction of information, and the politization of previous outbreaks could explain governments’ placement at the forefront of accusations. In casting blame on governments, it is possible that social media users felt a heightened sense of control by holding authorities accountable.

4.4. Conspiracy theories

Conspiracy theories are a manifestation of mistrust and encompass proposed plots wherein authorities or collectives collaborate to achieve a typically harmful objective (Oliver & Wood, 2014). The occurrence of conspiracy theories during epidemics has been shown in previous research (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015; Earnshaw et al., 2019). Conversely, social media data collected regarding the Ebola outbreak have also suggested that preoccupations with conspiracy theories was less frequent and widespread than previously believed (Roy et al., 2020).

However, within weeks of the coronavirus emergence, misleading rumours and conspiracy theories about the origin and spread of the virus circulated around the globe (Depoux et al., 2020). The current study corroborates the findings of conspiracy theories regarding Covid19. Indeed, the current outbreak has inspired numerous conspiracy theories on social media with potentially life-endangering consequences (Radwan & Radwan, 2020). A popular theory, present in our results, involved the connection of 5G towers to the spread of coronavirus. According to Ahmed et al. (2020) in a sample of 233 tweets, almost 35% involved the notion that 5G and the coronavirus were linked. The analysis of this theory revealed a lack of an authority figure combatting the distortion. The misinformation pandemic attached to the coronavirus pandemic has been in the centre of scientific research thus far (Chrousos & Mentis, 2020; Kouzy et al., 2020; Kulkarni et al., 2020; Pennycook et al., 2020; Li, Bailey, et al., 2020; Brindha et al., 2020; Radwan & Radwan, 2020; Hua & Shaw, 2020; Cinelli et al., 2020), however a sufficient explanation of the explosion of conspiracy theories does not currently exist.

Past research suggests that conspiracy beliefs may constitute a belief system or worldview (Wood et al., 2012), underpinned by a general distrust for authorities. In the context of a global health emergency, strict criteria and censorship are more likely to result in exacerbation of conspiracy theories and further propagation of such beliefs on social media platforms (Sharma et al., 2017). In the current study, conspiracy theories almost exclusively occurred during the early stages of the outbreak, i.e., at a time where most users accused the government of censorship of information. Accordingly, the progression of blame in our results may verify the connection between censorship of information and conspiracy theories. To prevent public health issues driven by conspiracy theories, it is imperative that the public trusts authorities (Earnshaw et al., 2019).

On the other hand, a recent study by Ferrara (2020) offers an alternative explanation for the exponential formation of conspiracy theories. The author argues that social media platforms are populated by bots (short for robot); that is, automated accounts that can amplify certain topics of discussion at the expense of others. The present findings uncovered the use of bots to promote political conspiracy theories and propaganda regarding the coronavirus in the United States.

However, the line of research regarding bot detection online is still in its infancy. Regardless of the origin, conspiracy theories have potentially devastating consequences and targeted interventions to delegitimize the sources of such fake information are essential to reduce their impact (Ahmed et al., 2020).

4.5. Media

The content and quality of information presented during emerging diseases greatly influences public perception (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015; Young et al., 2008). The mass media have been highlighted in public perception as “villains” in previous epidemics. During the H1N1 outbreak, the media were portrayed as encouraging fear mongering and misinformation (Mayor et al., 2013; Wagner-Egger et al., 2011). Similarly, during the Ebola epidemic the media were frequently accused of sensationalism, fear mongering and the deliberate spread of panic (Roy et al., 2020). The current study documents similar findings. Social media users arraigned the media during the coronavirus epidemic.

The traditional disaster coverage by mass media involves sensationalist news framing through emotionally evocative images and eyewitness accounts to persuade the public of established blame attributions (Atkeson & Maestas, 2012; Canales et al., 2019). Ongoing repetition of threatening information may increase fear and confusion and lead to mobilization. Moreover, threatening information can undermine public trust in media and government institutions, especially if they are perceived to overdramatize minor risks (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015; Larson et al., 2011; Poland, 2010; Rubin et al., 2009). Additionally, the mass media is a key conduit for strategic politicization of an outbreak. The framing of news regarding past epidemics was significantly manipulated to aid or hinder political parties (Greer & Singer, 2017). In the current pandemic, Chinese media were monopolized by the government and in the early stages of the crisis only restricted and selective information was published (Shangguan et al., 2020), leading to mistrust and disregard of preventative health behaviours.

Overall, the polarized framing of health information, the sensationalist reports for a broader audience and the politicization of emerging outbreaks has rendered the media a villainous, deceptive source of information during past and present outbreaks (Rousseau et al., 2015).

4.6. Social others

Previous media studies have documented that distant groups are often accused of an epidemic (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015; Broom & Broom, 2017). Scapegoats allow for distancing from the outbreak and from political or moral responsibility and elevate the status of accusatory nations (Atlani-Duault et al., 2015). Alternatively, the figures of blame may be interpreted through existing perceptions of groups the public already distrusts (Wilkinson & Fairhead, 2017), thus reinforcing recurrent targeting of certain collectives. However, the current study documents a decrease in blame attribution toward social others, with blame most often targeting national governments. This divergence may be attributed to the timeline examined in this research. Specifically, the prosecution of the Chinese may have exponentially increased in late March, beyond the scope of this study and following political events. Indeed, the discrimination of people of Chinese origin regardless of current country of residence has amplified online and offline (Budhwani & Sun, 2020). Chinese visitors have been labelled as dirty, insensitive and even bioterrorists (Barreneche, 2020; Shimizu, 2020). This online prosecution of the Chinese has evolved into a stigma that is reinforced by society through interpersonal and online interactions (Budhwani & Sun, 2020; Depoux et al., 2020). To add fuel to the fire, the US president referenced the term “Chinese virus” and “China virus” on Twitter. Soon after the statement, there was an high increase in the number of tweets specifying “Chinese virus” instead of “coronavirus disease”. Prior to the presidential statement, the identification of the virus as Chinese was observed in approximately 16,000 tweets, while after the publication of the tweet the coronavirus was exclusively mentioned as Chinese by over 170,000 tweets. The rise in tweets focusing on the virus as Chinese, along with the content of these tweets, indicates the Chinese community stigma perpetuation (Budhwani & Sun, 2020), which may lead to negative consequences of disease control, as prior outbreaks have documented (Lin, 2020).

The implications of otherization reach beyond the geographical boundaries of the affected population (Monson, 2017), as blame is fuelled by the mass media in the form of fear mongering (Shimizu, 2020) and leads to the escalation of conspiracy theories (Earnshaw et al., 2019) and irrational behaviours from the public.

4.7. Research limitations

At the time of writing, the coronavirus pandemic is still ongoing and as such the time examined only pertains to a fraction of the crisis timeframe. Moreover, our findings exclusively correspond to the early stages of the outbreak and cannot be generalized to identify blame patterns throughout the pandemic.

Additionally, due to the large size of the dataset (60 million Twitter posts), this study has limited the scope of examination to a fraction of Twitter posts (9000 tweets). Furthermore, the prevalence of the identified thematic categories of blame may be inaccurate when compared to the full dataset. To examine the full dataset of Twitter posts in relation to blame, keywords would have to be devised to identify possible patterns. However, blame in text is often expressed through implicit language and further, keywords could guide data extraction. Thus, the current study examined a fraction of Twitter posts without using keywords to preserve the authentic message of social media users.

Furthermore, this study limited the analysis to the social media platform Twitter. It is possible that the perception of blame is expressed differently on other social media, perhaps depending on the content regulations of each platform. Specifically, other platforms allow for a greater number of words or different forms of media that may alter or contain further information on the user's blame perception.

Recent research documents the presence of bots in social media platforms, that is, automated accounts that may spread malicious or misleading content (Ferrara, 2020). At the time of writing, the research regarding bots was limited and as such the current study does not account for the potential presence of bots in the sample.

Lastly, the current study is restricted in the analysis of English Twitter posts, which may overrepresent the perceptions of English-speaking countries. However, as geographical data are not present in the majority of Twitter posts, it is not possible to examine this conjecture.

4.8. Recommendations and future directions

Prior research (Mayor et al., 2013) argued that the negative representations of authority in the public's perception during health emergencies have potentially devastating consequences. Moreover, the mistrust and villainous perception of key collectives in times of disease by the public may persist in collective memory and affect the next pandemic. The current study appears to corroborate this argument concerning future epidemics, as the public attributed responsibility to national governments during the current coronavirus pandemic. These findings have important implications for health policy as authorities cannot ensure compliance with the recommended protective behaviours without the public's trust. Furthermore, the rise in conspiracy theories may be connected with government accusations, as previous research highlights that such theories originate in mistrust in the authorities (Wood et al., 2012). This rampant dissemination of misinformation on social media may have devastating consequences in preventive behaviours that further spread the virus worldwide (Chrousos & Mentis, 2020).

For the present crisis, several researchers have argued for the creation of a global information sharing system on social media platforms in different languages to ensure the control of misinformation and conspiracy theories to contain this pandemic (Depoux et al., 2020; Radwan & Radwan, 2020). In addition, past research has documented that clear information and coordination between health authorities and the media promotes adherence to preventative behaviours (Rousseau et al., 2015). Moreover, health authorities and government should be more attentive of public attitudes during outbreaks. Positive perceptions of governments during a crisis will improve the adherence to preventative behaviours toward long term pandemic control (He et al., 2020; Yasir et al., 2020). Furthermore, to shift the negative representation of the government, transparency is key to encourage open public health communication for emergencies (O'Malley et al., 2009).

The current study along with previous literature (Mayor et al., 2013; Roy et al., 2020) highlights the evolving nature of the perception of blame that appears to be continuously shifting on social media. Moreover, the examination of real time and ongoing analysis of social media conversations is essential to tailor online communication efforts to the user's perception. Due to the limited timeline examined in this study, the progression of blame was not captured throughout the pandemic and future longitudinal research may contribute to identifying patterns of progression during the outbreak to potentially predict blame progression in future crises.

Further studies may focus on the entirety of the coronavirus pandemic rather than the early stages and identify the divergent dynamics of blame throughout the outbreak. Additionally, studies across different platforms and languages may contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the identified patterns of blame in previous and current research, such as government mistrust and xenophobia, or alternatively discover emerging blame perceptions in the context of Covid-19. Thus, health policies and communication strategies concerning social media users will be better informed to counteract growth of discrimination and misinformation.

Lastly, our findings document a severe lack of trust in government officials, which is crucial during disease outbreaks. Moreover, future research may analyse and identify issues in government and authority management and communication strategies during global health emergencies.

5. Conclusion

At the time of writing, there are no tools to combat COVID-19 other than pharmaceutical efforts. Social media intelligence can enhance mobilization of the public and local community (Depoux et al., 2020). However, public health authorities are not sufficiently informed about the conversations circulating on social media as they predominately use social media as a one-way channel to disseminate information (Fung et al., 2016). The present study documents the pertinence social media conversations' analysis regarding blame as they contain valuable information about the public's perceptions. The knowledge of existing perceptions of health interventions can improve targeted health communication strategies, identify and counter attempts to blame, scapegoat and spread misinformation, and improve crisis management for the future (Atlani-Duault et al., 2020). Strategic communication of information is fundamental during a public health emergency (O'Malley et al., 2009). The current study argues for a dialogue between the government and the public to encourage trust, disseminate scientific information concerning the virus, promote preventive health behaviours and mobilize community efforts to combat the propagation of the devastating coronavirus pandemic.

Credit author statement

MC: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft Preparation. DJK: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Validation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

References

- Abeysinghe S. Ebola at the borders: Newspaper representations and the politics of border control. Third World Quarterly. 2016;37(3):452–467. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1111753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Vidal-Alaball J., Downing J., Seguí F.L. COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: Social network analysis of twitter data. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(5) doi: 10.2196/19458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkeson L.R., Maestas C.D. Cambridge University Press; 2012. Catastrophic politics: How extraordinary events redefine perceptions of government. [Google Scholar]

- Atlani-Duault L., Mercier A., Rousseau C., Guyot P., Moatti J.P. Blood libel rebooted: Traditional scapegoats, online media, and the H1N1 epidemic. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry. 2015;39:43–61. doi: 10.1007/s11013-014-9410-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlani-Duault L., Ward J.K., Roy M., Morin C., Wilson A. Tracking online heroisation and blame in epidemics. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(3):e137–e138. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30033-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badur S., Ota M., Öztürk S., Adegbola R., Dutta A. Vaccine confidence: The keys to restoring trust. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2020;16(5):1007–1017. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1740559. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1740559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreneche s.M. Somebody to blame: On the construction of the other in the context of the covid-19 outbreak. Society Register. 2020;4(2):19–32. doi: 10.14746/sr.2020.4.2.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgin H., Oz T., Havens R. A study on attribution of blame and responsibility in disaster recovery in the case of# FlintWaterCrisis. Frontiers in Communication. 2018;3:45. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bragazzi N.L., Alicino C., Trucchi C., Paganino C., Barberis I., Martini M., Icardi G. Global reaction to the recent outbreaks of Zika virus: Insights from a big data analysis. PloS One. 2017;12(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- British Psychological Society Ethics guidelines for internet-mediated research. 2017. https://www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/ethics-guidelines-internetmediated-research-2017 Retrieved from.

- Broom A., Broom J. Fear, duty and the moralities of care: The Ebola 2014 threat. Journal of Sociology. 2017;53(1):201–216. doi: 10.1177/1440783316634215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budhwani H., Sun R. Creating covid-19 stigma by referencing the novel coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” on twitter: Quantitative analysis of social media data. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(5) doi: 10.2196/19301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales K.L., Pope J.V., Maestas C.D. Tweeting blame in a federalist system: attributions for disaster response in social media following hurricane sandy. Social Science Quarterly. 2019;100(7):2594–2606. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter M. How Twitter may have helped Nigeria contain Ebola. BMJ British Medical Journal. 2014;349 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A.C., Williamson D.A. An outbreak of COVID- 19 caused by a new coronavirus: What we know so far. Medical Journal of Australia. 2020;212(9):393–394. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E., Lerman K., Ferrara E. Tracking social media discourse about the covid-19 pandemic: Development of a public coronavirus twitter data set. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 2020;6(2) doi: 10.2196/19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos G.P., Mentis A.F.A. Medical misinformation in mass and social media: An urgent call for action, especially during epidemics. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2020;50(5):e13227. doi: 10.1111/eci.13227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culotta A. Towards detecting influenza epidemics by analyzing Twitter messages. In Proceedings of the first workshop on social media analytics. 2010. -115122. [DOI]

- Depoux A., Martin S., Karafillakis E., Preet R., Wilder-Smith A., Larson H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2020;27(3) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa031. 031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw V.A., Bogart L.M., Klompas M., Katz I.T. Medical mistrust in the context of Ebola: Implications for intended care-seeking and quarantine policy support in the United States. Journal of Health Psychology. 2019;24(2):219–228. doi: 10.1177/1359105316650507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichelberger L. SARS and New York's Chinatown: The politics of risk and blame during an epidemic of fear. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(6):1284–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P. University of California Press; 2006. AIDS and accusation: Haiti and the geography of blame. [Google Scholar]

- Fauci A.S., Lane H.C., Redfield R.R. Covid-19—navigating the uncharted. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382:1268–1269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara E. What types of COVID-19 conspiracies are populated by Twitter bots?. First Monday. 2020. [DOI]

- Fung I.C.H., Duke C.H., Finch K.C., Snook K.R., Tseng P.L., Hernandez A.C.…Tse Z.T.H. Ebola virus disease and social media: A systematic review. American Journal of Infection Control. 2016;44(12):1660–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Zheng P., Jia Y., Chen H., Mao Y., Chen S., Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PloS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralinski L.E., Menachery V.D. Return of the coronavirus: 2019-nCoV. Viruses. 2020;12(2):135. doi: 10.3390/v12020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer S.L., Singer P.M. The United States confronts Ebola: Suasion, executive action and fragmentation. Health Economics, Policy and Law. 2017;12(1):81–104. doi: 10.1017/S1744133116000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays J.N. Rutgers University Press; 2009. The burdens of disease: Epidemics and human response in western history. [Google Scholar]

- He J., He L., Zhou W., Nie X., He M. Discrimination and social exclusion in the outbreak of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(8):2933. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewstone M. Basil Blackwell; 1989. Causal attribution: From cognitive processes to collective beliefs. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain L., Kam D., Kong F., Wigand R.T., Bossomaier T. Social media in Ebola outbreak. Epidemiology and Infection. 2016;144(10):2136–2143. doi: 10.1017/S095026881600039X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Xu X., Cai Y., Ge Q., Zeng G., Li X., Yang L. Mining the characteristics of covid-19 patients in China: Analysis of social media posts. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(5) doi: 10.2196/19087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J., Shaw R. Corona virus (Covid-19) “infodemic” and emerging issues through a data lens: The case of China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(7):2309. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanbin K., Rahmanian V. Using Twitter and web news mining to predict COVID- 19 outbreak. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2020;13 doi: 10.4103/19957645.279651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jalali R., Mohammadi M. Rumors and incorrect reports are more deadly than the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 2020;9:68. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-00738-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaseelan R., Brindha D., Kadeswaran S. Social media reigned by information or misinformation about COVID-19: A phenomenological study. Social Sciences & Humanities Open. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3596058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzy R., Abi Jaoude J., Kraitem A., El Alam M.B., Karam B., Adib E., Baddour K. 2020. Coronavirus goes viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 misinformation epidemic on Twitter. Cureus. Vol. 12(3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni P., Prabhu S., Ramraj B. COVID-19-Infodemic overtaking pandemic? Time to disseminate facts over fear. Indian Journal of Community Health. 2020;32(2):264268. [Google Scholar]

- Kullar R., Goff D.A., Gauthier T.P., Smith T.C. To Tweet or Not to Tweet—a review of the viral power of Twitter for infectious diseases. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2020;22:14. doi: 10.1007/s11908-020-00723-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson H.J., Cooper L.Z., Eskola J., Katz S.L., Ratzan S. Addressing the vaccine confidence gap. The Lancet. 2011;378(9790):526–535. doi: 10.1016/S01406736(11)60678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.O.Y., Bailey A., Huynh D., Chan J. YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19: A pandemic of misinformation? BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Chen L.J., Chen X., Zhang M., Pang C.P., Chen H. Retrospective analysis of the possibility of predicting the COVID-19 outbreak from Internet searches and social media data, China, 2020. Euro Surveillance. 2020;25(10):2000199. doi: 10.2807/15607917.ES.2020.25.10.2000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.Y. Social reaction toward the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Social Health and Behavior. 2020;3(1):1. doi: 10.4103/SHB.SHB_11_20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linde-Arias A.R., Roura M., Siqueira E. Solidarity, vulnerability and mistrust: How context, information and government affect the lives of women in times of Zika. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2020;20:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-04987-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaad E., Cherfan P. Social Media data analytics on telehealth during the COVID- 19 pandemic. Cureus. 2020;12(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.7838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor E., Eicher V., Bangerter A., Gilles I., Clémence A., Green E.G. Dynamic social representations of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic: Shifting patterns of sense-making and blame. Public Understanding of Science. 2013;22(8):1011–1024. doi: 10.1177/0963662512443326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitman G. Ebola in a stew of fear. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(19):17631765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1411244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe A.E., Malle B.F. People systematically update moral judgments of blame. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2019;116(2):215. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson S. Ebola as african: American media discourses of panic and otherization. Africa Today. 2017;63(3):3–27. doi: 10.2979/africatoday.63.3.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R.C., Luengo-Oroz M., Mello M.B., Paz J., Pantin C., Erkkola T. Social media monitoring of discrimination and HIV testing in Brazil, 2014–2015. AIDS and Behavior. 2017;21(1):114–120. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1753-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley P., Rainford J., Thompson A. Transparency during public health emergencies: From rhetoric to reality. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87:614618. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.056689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]