Abstract

Background

Italy was among the first countries hit by the pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. The application of strict lockdown measures disproportionately affected both cancer patient care as well as basic and translational cancer research.

Materials and methods

The Italian Cancer Society (SIC) conducted a survey on the effect of lockdown on laboratories involved in cancer research in Italy. The survey was completed by 570 researchers at different stages of their career, working in cancer centers, research institutes and universities from 19 Italian regions.

Results

During the lockdown period, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic emergency on face-to-face research activities was high, with a complete (47.7%) or partial (36.1%) shutdown of the laboratories. In the post-lockdown period, research activities were resumed in most of the respondents’ institutions (80.4%), though with some restrictions (77.2%). COVID-19 testing was offered to research personnel only in ~50% of research institutions. Overall, the response to the pandemic was fragmented as in many cases institutions adopted different strategies often aimed at limiting possible infections without a clearly defined contingency plan. Nevertheless, research was able to provide the first answers and possible ways out of the pandemic, also with the contribution of many cancer researchers that sacrificed their research programs to help overcome the pandemic by offering their knowledge and technologies.

Conclusions

Given the current persistence of an emergency situation in many European countries, a more adequate organization of research centers will be urgent and necessary to ensure the continuity of laboratory activities in a safe environment.

Key words: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, cancer research

Highlights

-

•

The SIC conducted a survey on the effect of COVID-19 lockdown on cancer research laboratories in Italy.

-

•

The impact of the lockdown on research activities was high, with complete or partial shutdown of >80% of the laboratories.

-

•

Response to the pandemic was fragmented with different strategies adopted without a clearly defined contingency plan.

-

•

An adequate organization of research centers is urgently needed to ensure laboratory activities in a safe environment.

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has resulted in an ongoing pandemic that affected >115 million people and caused >2.5 million deaths worldwide (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html).

Italy was among the first countries hit by this pandemic and its rapid evolution in Northern Italy led to the application of strict lockdown measures that profoundly affected all activities and disproportionately affected both cancer patient care as well as cancer research. This effect became then evident not only in Italy but worldwide, as recently reviewed by Painter and colleagues.1 Cancer patients experienced a particularly adverse outcome upon SARS-CoV-2 infection.1, 2, 3 The pandemic also negatively impacted cancer care with ~90% of cancer centers experiencing a reduction in their ability to provide services worldwide4 and in the possibility to carry out cancer screening programs, especially for racial and ethnic minorities.5,6

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic had a relevant impact on clinical research in oncology, with a reduction of 74% of patients enrolled in clinical trials in May 2020 compared with the same period in 2019.7 This drop in patient recruitment has been related to the decreased ability of clinical, support and preclinical units in providing nonessential activities and to the reallocation of resources to more critical services and trials.7 For instance, between January and June 2020, >1200 SARS-CoV-2-related clinical trials have been registered in only nine countries.7

Basic and translational cancer research was also profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic at different levels. A cut in cancer research funding due to the pandemic has been anticipated worldwide,1,8,9 and many researchers reported a reduction or complete shutdown in their laboratory activities with possibly profound consequences on years of previous activities in building models, collecting samples and supporting clinical activities not only in Italy but also worldwide.10, 11, 12

Yet, although there is the clear perception that preclinical cancer research has been strongly affected by the current pandemic, we still do not have any systematic report on how the pandemic impacted at the national and/or international level on the activities of cancer research laboratories and how the cancer research community lived during the months of more severe lockdown.

To fill this gap, here we show the results of a survey conducted by the Italian Cancer Society (SIC) on the effect of lockdown on laboratories involved in cancer research in Italy during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey was completed by 570 researchers at different stages of their career, working in cancer centers, research institutes and universities from 19 Italian regions. We discuss what the Italian cancer community has learned from this experience and what we think should be the next steps to face the new challenges raised by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Materials and methods

In May 2020, the Italian Cancer Society (Società Italiana di Cancerologia, SIC; https://www.cancerologia.it) launched a survey to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer research conducted in Italy. To deploy the questionnaire rapidly and for very fast data collection, a web-based modality was chosen. The Google Forms platform was the choice to implement the survey, and responses were automatically stored in a database built with Excel (Microsoft Office).

The survey was proposed to scientists involved in cancer research in universities, cancer centers and research institutes. Responses were collected between 5 and 27 May, with 93% of responses registered in the first 10 days (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survey response rate between 5 and 27 May. Dots represent the number of responders per day. Squares represent the cumulative number of responders per day.

Twenty-nine questions were asked, including rating scale (from 0 to 10), multiple-choice, closed- and open-ended questions (Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100165). Questions covered the characteristics of responders, as well as the modality of research activity during the first two phases (phase 1 and 2) of the COVID-19 pandemic that in Italy were distinguished by over 2 months of total lockdown all around Italy (phase 1 from 9 March) and a gradual easing of lockdown from 4 to 18 May (phase 2). Rating scale responses (from 0 to 10) were recoded into three-level variables, combining the bottom three boxes (from 0 to 2) as low, the middle rates (from 3 to 7) as neutral, and the top three boxes (from 8 to 10) as high. Manual content analysis was carried out on multiple-choice and open-ended questions, and responses were categorized into three levels (no/partially/yes or increased/unchanged/decreased, as appropriate). Eleven questions related to the lockdown phase were further summarized by means of a ‘lockdown score’, representing the sum over the 11 responses, after having assigned the lowest (bottom three boxes/no/increased), middle (neutral/partially/unchanged) and the highest (top three boxes/yes/decreased) categories to 0, 0.5 and 1 values, respectively. The sum was then divided by 11 to normalize the lockdown score into range 0-1. High score represents a high impact on research activities during the lockdown phase.

Responses were described as frequencies and percentages, or median and first/third quartiles for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Chi-square test was used to assess the association between variables. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare continuous distributions. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Italian cancer researchers were invited to respond to an online questionnaire aimed at verifying the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent lockdown on their activity (see Materials and Methods). The response rate to this survey was high with a total of 570 researchers participating (Figure 1). Participants were 44 years old on average, 68.4% female and 28.8% male (Table 1). Over 200 survey respondents were group leaders, professors or directors of research institutions (Table 1). Cancer centers and universities were the prominent affiliations among survey respondents (81%; Table 1). Overall, research institutions were located in Northern (58.4%), Central (18.9%) and Southern (20.7%) Italy (Table 1). During the lockdown period, namely, phase 1 from 9 March to 4 May 2020, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic emergency on face-to-face research activities was high (70.7%; high top three boxes; Tables 2 and 3), with a complete (47.7%) or partial (36.1%) shutdown of the laboratories (Tables 2 and 3). Geographical distribution of work area was significantly associated with research activity interruption (P < 0.01; chi-square test), with a prevalence in North Italy (60%-75%; Figure 2 and Table 3). This result could be interpreted in light of a higher number of COVID-19 infections in Northern Italy as well as of more severe restrictions to both access to research centers and individual mobility.

Table 1.

Characteristics of responders; N = 570

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 164 | 28.8 |

| Female | 390 | 68.4 |

| NA | 16 | 2.8 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20-25 | 8 | 1.4 |

| 26-30 | 76 | 13.3 |

| 31-35 | 90 | 15.8 |

| 36-40 | 89 | 15.6 |

| 41-50 | 114 | 20.0 |

| >50 | 185 | 32.5 |

| NA | 8 | 1.4 |

| Educational level | ||

| PhD | 363 | 63.7 |

| PhD Fellow | 49 | 8.6 |

| No PhD | 142 | 24.9 |

| NA | 16 | 2.8 |

| Main country of work | ||

| Italy | 562 | 98.6 |

| Not Italy | 4 | 0.7 |

| NA | 4 | 0.7 |

| Italian geographical area of work | ||

| Northern Italy | 333 | 58.4 |

| Central Italy | 108 | 18.9 |

| Southern Italy | 118 | 20.7 |

| NA | 11 | 1.9 |

| Role | ||

| Director/Group leader/Professor | 215 | 37.7 |

| Junior group leader | 15 | 2.6 |

| Researcher | 190 | 33.3 |

| Student | 58 | 10.2 |

| Technician/Administrative/Consultant | 41 | 7.2 |

| NA | 51 | 8.9 |

| Time spent on computer activities | ||

| Low | 12 | 2.1 |

| Neutral | 327 | 57.4 |

| High | 229 | 40.2 |

| NA | 2 | 0.4 |

| Research fields (multiple options) | ||

| Basic research | 301 | 39.3 |

| Translational research | 395 | 51.6 |

| Preclinical/Clinical research | 59 | 7.7 |

| Public health | 1 | 0.1 |

| Bioinformatics | 3 | 0.4 |

| Epidemiology | 2 | 0.3 |

| Biomedical research | 1 | 0.1 |

| NA | 3 | 0.4 |

| Research institute | ||

| University | 195 | 34.2 |

| Cancer center | 267 | 46.8 |

| University and cancer center | 27 | 4.7 |

| Other | 77 | 13.5 |

| NA | 4 | 0.7 |

Percentages do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

NA, not applicable.

Table 2.

Research activities during lockdown (phase 1); N = 570

|

N(%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Bottom 3-boxes |

Neutral | High Top 3-boxes |

NA | |

| Impact on research activities | 37 (6.5) | 210 (36.8) | 323 (56.7) | 0 |

| Impact on face-to-face research activities | 44 (7.7) | 110 (19.3) | 403 (70.7) | 13 (2.3) |

| Use of smart working | 82 (14.4) | 171 (30.0) | 315 (55.3) | 2 (0.4) |

| No | Partially | Yes | NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institute research activities shutdown | 90 (15.8) | 206 (36.1) | 272 (47.7) | 2 (0.4) |

| Research group internal communication ceased (no mail/no virtual meeting/no phone call) | 554 (97.2) | – | 13 (2.3) | 3 (0.5) |

| Collaboration with other facilities ceased | 300 (52.6) | – | 78 (13.7) | 192 (33.7)a |

| Collaboration with clinicians ceased | 171 (30.0) | – | 394 (69.1) | 5 (0.9) |

| Involvement in COVID-19 research protocols | 386 (67.7) | – | 182 (31.9) | 2 (0.4) |

| Involvement in COVID-19 research activities/diagnosis | 403 (70.7) | – | 165 (28.9) | 2 (0.4) |

| Increased | Unchanged | Decreased | NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of worked hours per week | 153 (26.8) | 205 (36.0) | 207 (36.3) | 5 (0.9) |

| Salary variation | 9 (1.6) | 539 (94.6) | 12 (2.1) | 10 (1.8) |

Percentages do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

NA, not applicable.

Including 189 responders not using facilities for their research.

Table 3.

Distribution of research activities during lockdown phase 1 and phase 2, according to Italian geographical area of work and role of responders; distributions for significant association (chi-square test) are reported

| Italian geographical area of work |

Role |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern n = 333 | Central n = 108 | Southern n = 118 | Director/GL/Professor n = 215 | JGL n = 15 | Researcher n = 190 | Student n = 58 | TAC n = 41 | |

| Lockdown phase | ||||||||

| Institute research activities shutdown | P = 0.0003 | |||||||

| Low | 6.9 | 4.6 | 6.8 | |||||

| Neutral | 33.3 | 30.6 | 54.2 | |||||

| High | 59.8 | 64.8 | 39.0 | |||||

| Impact on face-to-face research activities | P = 0.0029 | P = 0.0434 | ||||||

| Low | 9.2 | 2.8 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 5.5 | 14.3 | 10.0 |

| Neutral | 15.6 | 23.4 | 30.1 | 24.5 | 13.3 | 20.8 | 5.4 | 20.0 |

| High | 75.2 | 73.8 | 61.1 | 68.4 | 86.7 | 73.8 | 80.4 | 70.0 |

| Use of smart working | P = 0.0121 | P < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Low | 13.3 | 7.4 | 22.0 | 16.4 | 13.3 | 6.3 | 15.8 | 43.9 |

| Neutral | 27.8 | 36.1 | 30.5 | 32.2 | 26.7 | 30.0 | 26.3 | 19.5 |

| High | 58.9 | 56.5 | 47.5 | 51.4 | 60.0 | 63.7 | 57.9 | 36.6 |

| Involvement in COVID-19 research protocols | P = 0.0284 | P = 0.0031 | ||||||

| No | 71.2 | 68.5 | 57.8 | 58.1 | 86.7 | 71.4 | 79.3 | 68.3 |

| Yes | 28.8 | 31.5 | 42.2 | 41.9 | 13.3 | 28.6 | 20.7 | 31.7 |

| Involvement in COVID-19 research activities/diagnosis | P < 0.0001 | |||||||

| No | 56.3 | 80.0 | 81.6 | 89.7 | 58.5 | |||

| Yes | 43.7 | 20.0 | 18.4 | 10.3 | 41.5 | |||

| Number of worked hours per week | P < 0.0001 | |||||||

| Increased | 35.1 | 33.3 | 23.3 | 15.5 | 29.0 | |||

| Unchanged | 36.5 | 33.3 | 40.2 | 20.7 | 47.4 | |||

| Decreased | 28.5 | 33.3 | 36.5 | 63.8 | 23.7 | |||

| Salary variation | P = 0.0053 | |||||||

| Increased | 1.2 | 0.0 | 4.4 | |||||

| Unchanged | 97.3 | 94.4 | 94.8 | |||||

| Decreased | 1.5 | 5.6 | 0.9 | |||||

| Phase2 | ||||||||

| Institute research activities resumed | P = 0.0457 | |||||||

| No | 18.3 | 14.8 | 27.1 | |||||

| Yes | 81.7 | 85.2 | 72.9 | |||||

| Involvement in the drafting of internal guidelines for research activities during phase 2 | P = 0.0141 | P < 0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 82.8 | 93.4 | 89.0 | 75.7 | 93.3 | 91.1 | 91.1 | 92.7 |

| Yes | 17.2 | 6.6 | 11.0 | 24.3 | 6.7 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 7.3 |

GL, Group Leader; JGL, Junior Group Leader; TAC, Technician/Administrative/Consultant.

Figure 2.

Distribution of research activities during lockdown phase 1 and phase 2, according to Italian geographical area of work. Absolute numbers of survey participants distributed in the geographical areas are also shown.

The use of smart-working modality was the choice to continue research activities (85.3%; neutral and high top three boxes; Figures 2 and 3 and Tables 2 and 3). This helped maintain regular communication among laboratory members (97.2% of agreement, Table 2) and maintaining research collaboration with other research facilities (52.6% of agreement; Table 2). Remarkably, survey respondents positively evaluated smart-working modality used in combination with face-to-face meetings in a future post-pandemic situation (Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100165). On the other hand, the COVID-19 emergency had a negative impact on the interaction between researchers and clinicians as expected, with 69.1% of activities ceased in phase 1 (Table 2).

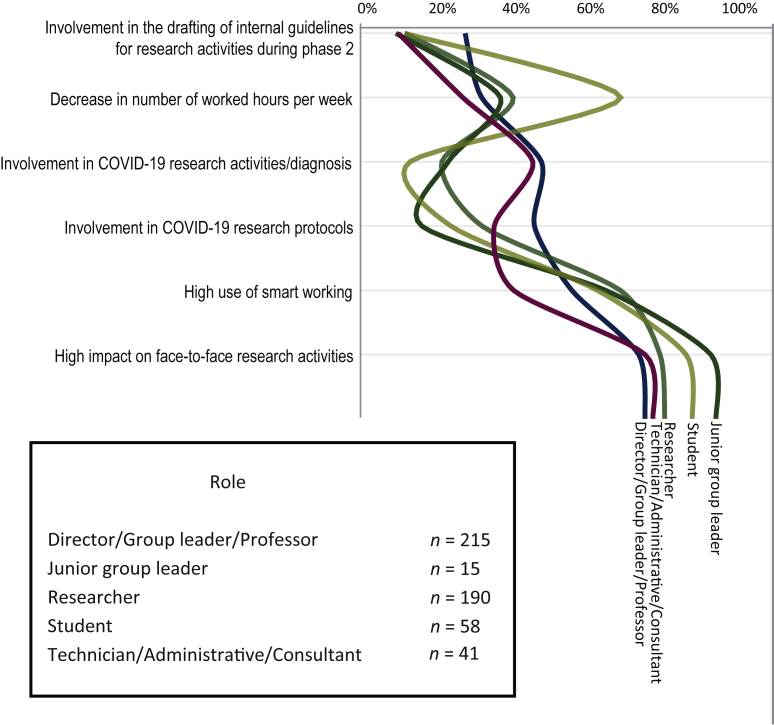

Figure 3.

Distribution of research activities during lockdown phase 1 and phase 2 according to job role. Absolute numbers of survey participants stratified by role are also shown.

Importantly, a sizable fraction of researchers was involved in COVID-19 research activities/diagnostics (31.9%; Figure 2 and Table 2) with, as expected, a high percentage of group leaders/professors/directors (41.9%, P = 0.0031; Figure 3 and Table 3) contributing to drafting COVID-19 research protocols and reorganization of research infrastructures. Lastly, salary remains overall unchanged (94.6% of agreement; Figure 2 and Tables 2 and 3).

In the post-lockdown period, i.e. phase 2, research activities were resumed in most of the respondents’ institutions (80.4%; Figure 2 and Tables 3 and 4) though with some restrictions for new internal guidelines (77.2%; Table 4) to primarily ensure safety in the workplace and productivity. Workplace space reorganization and work shift modification happened quite frequently in 60.5% and 82.5% of instances (Table 4). Furthermore, COVID-19 testing was offered to research personnel in ~50% of research institutions (Table 4). Group leaders, professors and directors of research departments/institutes were also frequently involved in drafting internal guidelines for resuming research activities (P < 0.0001; Figures 2 and 3 and Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Research activities during phase 2 (N = 570)

|

N (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Partially | Yes | NA | |

| Institute research activities resumed | 111 (19.5) | — | 458 (80.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Internal guidelines for research activities during phase 2 provided | 103 (18.1) | — | 440 (77.2) | 27 (4.7) |

| Involvement in the drafting of internal guidelines for research activities during phase 2 | 485 (85.1) | — | 81 (14.2) | 4 (0.7) |

| Workplace space reorganization during phase 2 | 149 (26.1) | — | 345 (60.5) | 76 (13.3) |

| Work shifts modified during phase 2 | 22 (3.9) | 3 (0.5) | 470 (82.5) | 75 (13.2) |

| PPE provided by research institute | 33 (5.8) | 4 (0.7) | 486 (85.3) | 47 (8.2) |

| COVID-19 testing during phase 2 | 163 (28.6) | 8 (1.4) | 277 (48.6) | 122 (21.4) |

| Collaboration with facilities | 13 (2.3) | 154 (27.0) | 244 (42.8) | 159 (27.9) |

Percentages do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

PPE, personal protective equipment.

Finally, we developed a ‘lockdown score’ (see methods) to assess the overall impact of the COVID-19 emergency on research during phase 1, considering the geographical distribution of research centers as well as the career level of interviewed researchers. Cancer research in Southern Italy seemed to be slightly less impacted by COVID-19 (P = 0.0566; Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100165), while the impact on ‘junior group leaders’ appeared to be significantly high (P = 0.0419; Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100165).

Discussion

This survey, for the first time, provides a quantitative estimation of the impact of COVID-19 on cancer research in Italy during and immediately after the lockdown in 2020. The results of this survey are very impressive as they clearly demonstrate that the emergency linked to COVID-19 has severely interrupted the activities of numerous laboratories engaged in the fight against cancer for many months. Although this survey refers to the first wave of the pandemic, its results are very current given the persistence of the emergency and the slowness of the vaccination campaign in many countries.

The impact on research activities was most evident in the Northern Italian regions, but this should not be surprising given the greater spread of the epidemic in this part of the country in the first quarter of 2020. The consequences of this limitation are difficult to estimate, but we can safely say that the reduction in the activities of laboratories involved in cancer research will result in a delay in those fundamental discoveries for developing new technologies to fight cancer. In 2020, precision oncology reached several important milestones. A number of highly active new targeted therapies become available for diseases that are extremely difficult to treat.13 The pandemic likely jeopardized the development of new drugs as well as the identification and validation of innovative biomarkers for diagnosis anticipation and prognosis prediction. This will negatively impact cancer patients’ prognosis in the short term.

Importantly, our survey also revealed that the response to the pandemic was fragmented as in many cases institutions adopted different strategies often aimed at limiting possible infections without a clearly defined contingency plan. It is worth noting that such a disorganized response to the emergency was expected because our country, as likewise many others, was not at all prepared for this challenge, as evidenced by the high number of deaths that we continue to record. During the first phase of the pandemic, Italian health care workers did not have access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), such as face masks, that was difficult to find. Therefore, in order to avoid massive infection of health care workers, clinical center directors decided to shut down research laboratories rather than trying to develop contingency plans and protocols to allow them to work safely. This evidence is also confirmed by the fact that some research laboratories in Northern Italy had not resumed activities even after the lockdown. Even more surprisingly, no specific measures, such as swabbing research workers, were adopted when the laboratories reopened in some centers, thus underlying the absence in many instances of COVID-19 work safety protocols for resuming research activities.

The COVID-19 lockdown has affected all research laboratories, but the observation that junior group leaders have been affected by this difficult period more than others highlights how this situation of uncertainty can negatively impact particularly younger researchers at the beginning of their academic career.

A limitation of this study was our inability to assess the response rate of the survey since the invitation was intentionally left open to all researchers and not limited to members of the Italian Cancer Society. However, we think this makes results more generalizable and representative of COVID-19’s detrimental impact on Italian cancer research activities.

The results of this survey are in agreement with previous studies that have described the significant impact of the pandemic on clinical practice and clinical research activities in oncology in Italy. Clinical oncology departments had to adapt their organization and treatment protocols taking into account the risk/benefit ratio for each individual patient.14, 15, 16, 17 These precautions were also necessary because patients with cancer who develop COVID-19 have a high probability of mortality.18 The impact on clinical research activities was also significant, with reductions reported by 80% of clinicians.16 Finally, a survey among 53 thoracic pathology centers from 18 European countries reported that clinical and molecular pathology activities decreased dramatically by 31% and 26%, respectively.19

Conclusion

The pandemic has now lasted for more than a year and is continuing to negatively impact cancer patient management and both experimental and clinical cancer research. Activities resumed in almost all the institutions, but the problems related to the reorganization of spaces, the preparation of risk plans and the monitoring of epidemic spread in the research community were only partially addressed. This unprecedented situation has, however, forced us to think of and develop new ways of working and communicating, to alternate work in the laboratory with smart working and perhaps to plan laboratory activities better. However, it is undeniable that the progress of research is based on idea exchange among collaborators, among researchers of different backgrounds and on constant mentoring between lab heads and trainees. The limitation of these activities will certainly affect above all the training and personal growth of the youngest researchers.

Among the effects of the pandemic, there is a fear of a considerable decrease in funding for research in general and for cancer research in particular. Yet, if there is one thing we should have learned from the pandemic, it is precisely the relevance of research: research was able to provide the first answers and possible ways out of this situation, with the contribution of many cancer researchers that sacrificed their research programs to help overcome the pandemic by offering their knowledge and technologies. Finally, a more adequate organization of research centers will be urgently required and necessary to assure the continuity of laboratory activities in a safe environment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) for its support in promoting this survey at a national level.

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Bakouny Z., Hawley J.E., Choueiri T.K. COVID-19 and cancer: current challenges and perspectives. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:629–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garassino M.C., Whisenant J.G., Huang L.-C. COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:914–922. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30314-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Passamonti F., Cattaneo C., Arcaini L. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity in patients with haematological malignancies in Italy: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e737–e745. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30251-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jazieh A.R., Akbulut H., Curigliano G. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care: a global collaborative study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1428–1438. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gathani T., Clayton G., MacInnes E., Horgan K. The COVID-19 pandemic and impact on breast cancer diagnoses: what happened in England in the first half of 2020. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:710–712. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carethers J.M., Sengupta R., Blakey R., Ribas A., D’Souza G. Disparities in cancer prevention in the COVID-19 era. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2020;13:893–896. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-20-0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey C., Black J.R.M., Swanton C. Cancer research: the lessons to learn from COVID-19. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1263–1266. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burki T.K. Cuts in cancer research funding due to COVID-19. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(1):e6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30749-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cancer Discovery COVID-19 hits cancer research funding. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:756. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-ND2020-007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zon L., Gomes A.P., Cance W.G. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on cancer research. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:591–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colbert L.E., Kouzy R., Abi Jaoude J., Ludmir E.B., Taniguchi C.M. Cancer research after COVID-19: where do we go from here? Cancer Cell. 2020;37:637–638. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bardelli A. Coronavirus lockdown: what I learnt when I shut my cancer lab in 48 hours. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn W.C., Bader J.S., Braun T.P. An expanded universe of cancer targets. Cell. 2021;184:1142–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meattini I., Franco P., Belgioia L. Radiation therapy during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy: a view of the nation’s young oncologists. ESMO Open. 2020;5(2):e000779. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambertini M., Toss A., Passaro A. Cancer care during the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy: young oncologists’ perspective. ESMO Open. 2020;5(2):e000759. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poggio F., Tagliamento M., Di Maio M. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the attitudes and practice of Italian oncologists toward breast cancer care and related research. activities. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(11):e1304–e1314. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onesti C.E., Rugo H.S., Generali D. Oncological care organisation during COVID-19 outbreak. ESMO Open. 2020;5(4):e000853. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saini K.S., Tagliamento M., Lambertini M. Mortality in patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and pooled analysis of 52 studies. Eur J Cancer. 2020;139:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofman P., Ilié M., Chamorey E. Clinical and molecular practice of European thoracic pathology laboratories during the COVID-19 pandemic. The past and the near future. ESMO Open. 2021;6(1):100024. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2020.100024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.