Abstract

Commercial Agriculture Development is widely seen as a pathway to agriculture commercialization, poverty reduction and pro-poor growth in developing economies. Using a counterfactual approach, this study assessed the impact of the Commercial Agricultural Development Project (CADP) in Nigeria on poverty status of beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries; determine its impact on commercialization of beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries and ascertain the pro-poor impact of the Project. Data from 1199 households comprising 678 beneficiaries and 521 non-beneficiaries were used for analysis. Propensity score matching was used to select comparable observations which reduced the sample size to 1142 observations: 655 beneficiaries, 487 non-beneficiaries. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, propensity score matching technique, Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) poverty measures, Average Treatment effect on the Treated (ATT) and Poverty equivalent growth rate (PEGR) pro-poor measure. FGT poverty indices were lower for CADP Beneficiaries than the non-beneficiaries. The impact of the CADP on poverty using the income of beneficiaries as proxy showed that those who participated in CADP had their income increased by N446,073.89 ($ 1,239.09) and were better off in terms of their welfare compared to those who did not participate in the program. For the impact on commercialization, the programme led to a statistically significant increase in the commercialization index of beneficiaries. Also the PEGR for non-beneficiaries was higher than the actual growth rate while that of beneficiaries was less than the actual growth rate implying that CADP was not pro-poor. The study concludes that even though the CADP impacted the poverty level of beneficiaries positively, it was not pro-poor hence there is a need to ensure that the poor are effectively targeted in designing development intervention programmes.

Keywords: Commercial agriculture development project (CADP), Propensity score matching, FGT Poverty indices, Commercialization index, Poverty equivalent growth rate

Commercial agriculture development project (CADP), Propensity score matching, FGT poverty indices, Commercialization index, Poverty equivalent growth rate.

1. Introduction

Agriculture is the mainstay of developing economies, underpinning their food security, export earnings and rural development. According to World Bank (2019a), the development of agriculture remains one of the most effective tools to end extreme poverty, boost shared prosperity and feed a projected 9.7 billion people by 2050. To meet demand, agriculture in 2050 will need to produce almost 50 percent more food, feed and biofuel than it did in 2012 (FAO, 2017). However, agricultural productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa has continued to fall short of expectations. In sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, agricultural output would need to more than double by 2050 to meet increased demand, while in the rest of the world the projected increase would be about one-third above current levels (FAO, 2017). Slow production growth and sharp annual fluctuations in output have continued to be the chronic problem of developing economies, thus constituting the main cause of their persistent poverty and rising food insecurity. Significant progress in promoting economic growth, reducing poverty and enhancing food security cannot be achieved in developing economies without consciously developing more fully the productive capacity of the agricultural sector.

Owing to this fact, most developing countries, especially in Africa have considered it a top priority in their development plans to include activities that can bring about increase productivity of the agricultural sector. Increased foreign direct investment in this sector, government pledges, commitment of public spending under the Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Development Programme (CAADP), and significant donors’ intervention in the agriculture supports this assertion of a highly prioritized sector. Furthermore, to harness the potential benefits of this sector, there have been many large scale commercial investments in the sector by governments, donor organizations and even the private sector. There is no doubt that African Agriculture is in a phase of rapid commercialization.

The quest for food security and agricultural transformation in Africa led to the launch of the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) in July 2003 which the African Heads of States endorsed as part of a New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD). The CAADP was aimed to help African countries reach a higher path of economic growth through agricultural sector led development. The main thrust was to eliminate hunger, reduce poverty attain food security and encourage export expansion.

Nigeria also endorsed the CAADP/NEPAD agreements. However, prior to this, successive Nigerian governments have implemented and continue to implement programmes targeted at agricultural output expansion, poverty reduction and rural livelihood enhancement. These programmes can be broadly divided into sectorial and multi-sectorial based on approach. The programmes designed for the expansion of agricultural output in Nigeria include; Operation Feed the Nation (OFN) and Green Revolution of 1970s, Peoples Bank of Nigeria - 1989 and Community Bank 1990. The World Bank Agricultural Development Projects (ADPs) and River Basin Development Authorities (RBDAs) were established in 1975, National Agricultural Land Development Authority (NALDA) 1991, Fadama Development Projects (1993), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) sponsored projects, and Commercial Agricultural Development Project (CADP) in 2009, the Agricultural Transformation Agenda (ATA) 2012, The Agro Processing, Productivity Enhancement and Livelihood Improvement Support – APPEALS Project (2017 to 2023).

The multi-sectoral programmes encapsulating poverty reduction and livelihood enhancement with agricultural sector component includes; Directorate of Food, Road and Rural Infrastructure (DFRRI)- 1986; National Directorate of Employment (NDE) -1986; Better Life Programme (BLP) 1987; Family Support Programme (FSP)-1994; Family Economic Advancement Programme (FEAP) -1997; Poverty Alleviation Programme (PAP) - 2000; National Poverty Eradication Programme (NAPEP)- 2001. Other programmes include Community Action Programme for Poverty Alleviation (CAPPA) - 1997; National Economic and Empowerment Development Strategy (NEEDS) -2004; Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN)-2003, N-Power-2016.

The impact of these programmes remains contentious. Some analysts have argued that these policies have benefited the poor while others opined that despite positive real growth, poverty had been on the increase. The findings of Gafaar and Osinubi (2005) showed that growth in Nigeria has been slightly pro-poor but the very poor have not benefitted from the growth, which can be adduced to the nature of growth pursued and underlying macroeconomic policies.

The Commercial Agricultural Development Project (CADP)-World Bank assisted was comprehensive in approach to agricultural development in Nigeria. The Project became effective on 30th July, 2009 and was implemented from then till 31st May, 2017. It had three main components of Agricultural Production and Commercialization, Rural Infrastructure and Project Management; Monitoring, Evaluation and Studies. Although revised when restructuring was done in 2014 and more components added. Overall, the project development objective of strengthening product systems and facilitating access to markets for selected value chains were aligned with Federal Government of Nigeria's strategic vision and World Bank's country partnership strategy (CPS).

The development objectives of CADP as reflected in the financing agreement dated May 5, 2009 had specific information on targeted value chains: i) to strengthen agricultural production systems, ii) to facilitate access to markets for small and medium scale commercial farmers engaged in targeted agricultural value chains which include aquaculture, cocoa, dairy, fruit trees, maize, palm oil, poultry and rice in the participating states. The states that participated in the Project were; Cross River, Enugu, Kaduna, Kano and Lagos; each state representing different geo-political and ecological zones to demonstrate the practicability of commercial agriculture in Nigeria.

The approach used by Commercial Agricultural Development Project was the demand-driven approach where all the Commodity Interest Group (CIGs) identified their priority needs and addressed them based on socially inclusive approach, while capacity building training was conducted for the successful implementation of Commercial Agricultural Development Project (World Bank, 2009). Commodity Interest Groups (CIGs) were the main vehicles through which the CADP was implemented not until 2014 when the project was restructured and the women and youth component of the project was now drafted into the project. The State Project Implementation Units (PIUs) were responsible for the implementation of all project components designed to achieve the main outcomes.

CADP was expected to assist in realizing the country's agricultural potential with the main strategic thrust of supporting access to productivity enhancing technologies, improve market access, improve capacity building and technical know-how, and to improve access to rural infrastructure. It is said that agricultural productivity has not grown sufficiently, due to underinvestment in new technology, slow adoption of existing improved technologies, constraints associated with the investment climate, and lagging infrastructure. A review of the theory of change for the Project reveals three key expected outcomes of increased production, yield and sales. The long term outcomes are improved farmer welfare (pro-poor growth) and non-oil (agricultural) growth. This is expected because increased production, yield and sales would have significant positive impact on farmers' welfare which would translate to poverty reduction and also bring about overall economic growth.

Many countries world over as well as international development agencies have promoted intensification and commercialization of agriculture, particularly small holder farming as a means of achieving poverty reduction and have reflected it in their development policies. The appraisal and implementation of the CADP were preceded and accompanied by a mix of significant agricultural sector issues. Shortly before the appraisal of the CADP, Nigeria was rated as a poor country, having exhibited at least 70% poverty incidence (World Bank, 2007b, World Bank, 2007a). This assessment is paradoxical, noting the substantial reliance of the country on agriculture for its contribution to GDP, total exports, labour employment and food. The average annual contribution of agriculture to the total GDP during the period 1995–2013 was 39.5% made up of; 34.5% (crop), 3.0% (livestock), 0.6% (forestry) and 1.4% (fishery), respectively.

A number of studies attempted to analyze the relationship between growth in agricultural productivity and poverty incidences in different countries at different time periods (Datt and Ravallion, 1998; Bravo-Ortega and Lederman, 2005; Byerlee et al., 2009: Ogundipe et al., 2017). In relation to the forgoing, Matthew et al. (2019) and Ogundipe et al. (2017) studied the linkages and pathways of agricultural productivity, social protection, poverty reduction and inclusive growth in Africa. Imahe and Alabi (2005), and Oni (2014) examined the role of agriculture in poverty reduction and some determinants of agricultural productivity respectively, both in Nigeria.

There are several studies on the evaluation of agricultural programmes in Nigeria, some of which include; Daneji (2011); Iwuchukwu and Igbokwe, 2012; Agber et al. (2013); International Fund for Agricultural Development [IFAD], 2016; Ozoani (2019) and Love (2020). These studies are useful as they show the state of programmes aimed at improving agricultural productivity and their impact on selected socioeconomic variables relevant to such programmes. Progress being made or otherwise is also shown by these studies. However, none of these studies explored the impact of such programmes on commercialization, poverty reduction and pro-poor growth. Specifically, Studies by Salisu (2012) and Bako (2012) reported that the CADP in Nigeria increased productivity, income, food security as well as assets in Kaduna State (one out of five states involved in the intervention). Worthy of note also, is that these two studies were conducted before the end of CADP). Ngene (2013) also carried out an assessment of the CADP. However, this present study deviates from the previous ones in its impact evaluation objectives, methodological approach and investigation of the pro-poor growth.

Specifically, the major contribution of this study is its approach of investigating counterfactual non-beneficiaries as well as project beneficiaries which allows for better attribution of the outcomes to the project. This contribution is important to evaluating not only the CADP but also the many other impact studies of projects conducted without using comparison groups (Mansuri & Rao, 2004). This study used quasi-experimental method to control for other factors that could affect project outcomes.

The prime objective of this study is an impact evaluation of CADP on commercialization, poverty reduction, and pro-poor growth in the five states that participated in the Project using a counterfactual approach. Specifically, this study firstly sought to determine the impact of CADP on poverty status of beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries; secondly, determine the impact of the Project on commercialization of beneficiaries; and thirdly, ascertain the impact of CADP commercialization among beneficiaries and fourthly, the nature of growth associated with the Commercial Agricultural Development Project. The questions of relevance to be addressed in this study are;

-

(1)

What was the impact of the project on the poverty status of beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries by socioeconomic characteristics

-

(2)

What was the impact of the project on the poverty status of beneficiaries?

-

(3)

What was the impact of CADP on commercialization among beneficiaries?

-

(4)

Was the CADP pro-poor?

2. Literature review

2.1. Concepts and theory of commercialization

Commercialization has various definitions depending on the focus and breadth, and its measurement is determined by these two factors. For this study, the CADP, commercialization is viewed as increasing the proportion of marketed output following (Govereh et al., 1999; Okezie et al., 2008). Commercialization with respect to agriculture may be defined as the degree to which a farm household is connected to markets. This connection can be observed at any given point in time, or as a dynamic process whereby a household increases its interaction with input or output markets over time (Jaleta et al., 2009). The process involves the replacement of integrated farming systems by specialized crops, livestock, poultry, and aquaculture products. The process is endogenous and is accompanied by economic growth, urbanization and shifting labour from the agricultural sector (Pingali and Rosegrant, 1995). Agricultural commercialization implies a shift, which is often gradual, from subsistence to modernized farming, entails that production and input decisions are based on profit maximization and reinforcing vertical linkages between input and output markets. When properly harnessed, commercialization results in welfare gains for farmers through comparative advantage and increased total factor productivity growth (Johnston and Mellor, 1961). It should be noted that agricultural commercialization goes beyond marketing of agricultural outputs, as it implies that product choice and input use decisions are based on the principle of profit maximization (Yoon-Donn & Yoon, 2009). Conventional wisdom suggests that the transition from subsistence (or semi-subsistence) to commercial agriculture is key for the economic development of low-income countries. Comparative advantage allows agricultural commercialization to enhance trade and efficiency, leading to economic growth and welfare improvement at the national level. This is further expected to spur a virtuous circle which raises household income and subsequent improvement in consumption, food security and nutritional outcomes inside rural households.

For the CADP programme, commercialization was construed to involve; the participation in input and output market and the degree of participation in such markets. The latter is usually measured by the amount of commodities produced and offered to the market as compared to the total production. Therefore, the production of production of marketable surplus from the selected enterprises over what is needed for own consumption was a major determinant.

Theoretical underpinning of agricultural commercialization draws from agricultural transition, population and livelihood outcomes and its transition and the importance of increased agricultural productivity, labour productivity, market development and the growth of the industrial sector. This increased productivity can be achieved through commercialization. Commercialization is central to the structural transformation process as greater input market orientation increases the demand for industrial goods and technology essential for production, increases household welfare through employment generation and increased labor productivity and enables the transfer of surplus in the form of food, labor and capital from the agrarian sector to the other sectors (Pingali et al., 2019).

Theoretical literature on commercialization over the past decades has drawn heavily from Rostow's theoretical model of economic development (Timmer, 1988; Todaro, 1989; Pingali and Rosegrant 1995; Pingali, 1997). Subsequent studies expands on the previous theoretical foundation of agricultural commercialization tied to growth in stages and characteristic changes in farming systems or transition stages. This deviation views commercialization as change from subsistence type of production to market oriented with the aim of profit maximization (Golletti, 2005). Pingali and Rosegrant (1995) view commercialization as not only the selling of output but it also includes product choice and input use decisions that are based on profit maximization principle. The impact of commercialization on output being marketed, inputs, modern tools and technology and degree of commercialization abound in literature (Von Braun, 1995; Goletti, 2005).

Several theories support commercialization (Von Thunen, 1996; Fafchamps and Shilpi, 2003; Garrett and Chowdhury, 2004). These models revolves around classic agricultural land use and urbanization as it relates to agricultural commercialization. The role of infrastructure and market access in agricultural commercialization in providing more opportunities for adoption of new technologies and enterprises is also strongly supported in theory.

2.2. Concepts and theories of poverty

There are different theories on poverty and extremely abundant literature characterized by an unusual level of ambiguity relative to economic theory. Each conceptual definition of poverty leads to a particular identification of the poor and each concept coming with its own recommendations for addressing poverty reduction.

There are three main schools of thought concerning poverty. These are; the Welfarist School, the Basic Needs School, and the Capability School. Though these three differ in their approaches in many ways, they all imply that “something”, which is defined, is not at a level considered to be a reasonable minimum. This means that an individual is judged to be poor whenever he or she is lacking, with respect to the reasonable minimum, the particular “thing” in question. The conceptual debate on poverty arises when taking up the nature of that missing thing.

Well-being is systematically used at the individual level while welfare is used for the aggregate level. This approach reduced the concept of well-being to the usual economic concept of utility sometimes referred to as standard of living. The welfarist view utility as a psychological feeling like happiness, pleasure, desire and fulfillment derived from commodity consumption (Asselin and Dauphin, 2001). The approach is anchored in classical micro economics where welfare or utility accounts for the behaviour and well-being of individuals. According to the welfarist, "Poverty” exists in a given society when one or more persons do not attain a level of economic well-being deemed to constitute a reasonable minimum by the standards of that society. To the welfarist, income determines the utility level; poverty is then defined as a socially unacceptable level of income and poverty alleviation policies will mostly try to increase the productivity of the poor. The approach recommends policies to promote productivity, employment and thus income in order to alleviate poverty. The welfarist school is the dominant in the approaches to poverty reduction and is a leader among development organizations and the World Bank in particular favour and promotes the concept.

The other two schools which are non-welfarist are the Basic Needs school approach and Capability school approach. The Basic Needs school dates back to the early 1900s with the studies of Rowntree and only took form in the 1970s, when it arose in reaction to the inattention paid to the needs of individuals. The Basic school considers that the “something” lacking in the lives of the poor is a small subset of goods and services required to meet the basic needs of all human beings. “Basic needs” implies that satisfaction of these needs is a pre-requisite to quality of life; they are not initially perceived as generators of well-being. Under this approach, the attention is on individual requirements relative to basic commodities and not utility. The traditional Basic Needs approach categorizes the basic goods and services to include: food, water, sanitation, shelter, clothing, basic education, health services, and public transportation. These needs transcend those necessary for existence, which only include: adequate nutrition, shelter and clothing. It must be noted that the subset of basic commodities is different according to sex and age.

The hypothesis of the Basic Needs approach is that a set of selective policies makes it possible to satisfy the basic human needs though it recognizes the intentions of policies oriented towards raising revenue in the fight against poverty.

The third school is the capability school, an economic theory conceived by its principal advocate, Amartya Sen, in the 1980s. The core focus of the theory is on what individuals are able to do i.e. capable of, claiming that the value of someone's life has many other constituents than utility. An individual's capability to have a good life is defined in terms of the set of valuable ‘beings and doings’ like being in good health and having loving relationships with others with which they have real access. The state of ‘beings and doings’ are called functionings which can vary from such elementary physical ones as being well-nourished, being adequately clothed and sheltered, avoiding preventable morbidity, etc, to more complex social achievements such as taking part in the life of the community, being able to appear in public without shame, and so on (Sen, 1983). The capability school refers to the set of valuable functionings that a person have effective access to. Thus, an individual's capability represents the effective freedom to choose between different combinations of being. Under this approach, poverty is understood as deprivation in the capability to live a good life and development is understood as capability expansion.

Poverty measure is a statistical function that translates the comparison of the indicator of household well-being and the chosen poverty line into one aggregate number for the population as a whole or a population subgroup (Coudouel et al., 2002). There are several models for measuring poverty. Some of these models are: Foster, Greer and Thorbecke FGT weighted poverty measure (Foster et al., 1984), Sen Index (Sen 1976), Human Development Index (HDI) (UNDP, 1990), Basic Needs Index, Food Security Index (FSI), Integrated Poverty Index (IPI), Relative Welfare Index (IFAD, 1993) and most recently, Multidimensional Poverty Measurement (Asselin, 2009; Cohen, 2010). We do not intend to discuss the different concepts of poverty here; this type of discussion is already found abundantly in the literature (Asselin and Dauphin, 2001; UNDP, 2006). Constrained by data set limitation, we focus on Foster, Greer and Thorbecke (FGT) approach in determining the poverty status of CADP beneficiaries’.

2.3. Concepts and theories of pro-poor growth

Growth is pro-poor if the poverty measure of interest falls. According to this definition there are three potential sources of pro-poor growth: (1) a high rate of growth of average incomes; (2) a high sensitivity of poverty to growth in average incomes; and (3) a poverty-reducing pattern of growth in relative incomes (Kraay, 2004). However, according to Jmorova (2017) two wide definitions (strict and general) of pro-poor growth have emerged thus: i) growth is pro-poor when is followed by decreasing in inequality (Kakwani and Pernia, 2000); ii) growth is pro-poor when it simply reduces poverty (Ravallion, 2004).

Poverty reduction depends on two factors which are: (i) growth and (ii) how the benefits of growth are distributed across the poor and non-poor. One major stream and indeed general definition of pro-poor growth is growth where poverty declines, irrespective of (i) or (ii) or both. With this definition, growth will always be pro-poor whenever there is reduction in poverty. The approach used by Ravallion and Chen (2003) tends to fall under this definition.

On the other hand, the strict definition of pro-poor growth emphasizes how the benefits of growth are distributed among the poor and non-poor in society. Under the strict definition, the sole focus is on growth that leads to poverty reduction and the benefits of growth accrue largely to the poor. The work of scholars like McCulloch and Baulch (2000), Kakwani and Pernia (2000), Kakwani and Son (2008), and Son (2004); are based on the strict definition of pro-poor growth.

Under the general approach, growth may be defined as pro-poor if the income of the poor increases by $1 and the income of the very rich increases by $1 million. This scenario, however, will always be anti-poor based on the strict approach to defining pro-poor growth. Nevertheless, one should bear in mind that the term “pro-poor” literally means in favor of the poor. In this regard, the concept and measure of pro-poor growth should be examined from a distributional perspective.

The strict approach to defining pro-poor growth can further be classified into relative or absolute approach. The relative concept refers to economic growth that proportionally benefits the poor more than the non-poor. The implication of this is that while growth reduces poverty, it also addresses inequality. Relative approach is used as it looks into the relation between growth and poverty reduction because it implies a reduction in relative inequality. In the same vein, a measure of pro-poor growth is absolute when after a comparison of the absolute benefits from growth is done, the poor gains more than the non-poor. By this definition, absolute inequality would fall during the course of growth. It provides the strongest requirement for achieving pro-poor growth. Consequently, there is more difficulty in achieving absolute pro-poor growth than relative pro-poor growth (Kakwani & Son, 2008).

The concept of pro-poor growth has been interpreted and measured differently by Economists. For instance, according to Kakwani and Pernia (2000), a growth pattern is pro-poor if the income of the poor grows at a faster rate than that of the non-poor. Literature refers to this definition as the relative approach. There is an opposing view represented by Ravallion and Chen (2003) who posited that a growth pattern will be pro-poor if and only if the income of the poor grows irrespective of how much the non-poor may have gained. This is the absolute approach. An in-between definition has also been introduced where Pro-poor growth is defined as a growth process that reduces poverty more than it does in the benchmark (Since our concern with pro-poor growth derives from our dissatisfaction with past growth experiences, these can be taken as the benchmark) In general, pro-poor growth must involve more than just poverty-reducing growth(Osmani, 2005).

Development thinking has shifted from the theory that broad economic development is good for all and only few today are of the view that the trickle-down theory works in practice. Approaches targeted at addressing poverty usually focus on one or more aspects of the phenomenon depending on the context and theory of change of the intervening agency. Examples of pro-poor measures include: addressing economic poverty (facilitating access to affordable credit; promoting income-generating opportunities), building human capacities (promoting access to education for all especially the girl-child, vocational skills training) and addressing political aspects of poverty (facilitating collective action, informing the disadvantaged of their rights, building negotiation capacities etc.). Others are: addressing socio-cultural aspects of poverty (facilitating full and equal representation of different gender groups in community decision making process, supporting discriminated groups to claim their rights) and building protective capacities (building peoples resilience to withstand domestic and external shocks). Pro-poor policies are not an end in themselves but means to an end in that they are aimed at achieving pro-poor growth. This study in determining Pro-poor growth of the CADP follows PEGR index of Kakwani and Son (2003); Ravallion and Chen (2003) index, Kakwani and Pernia (2000) index.

3. Methodology

3.1. The study area

The study covered five (5) states in Nigeria where CADP, a World Bank assisted project, was implemented as a pilot project. These States are: Cross River, Enugu and Lagos in the South; Kaduna and Kano in the North (Figure 1). Nigeria is a country in West Africa with a population of about one hundred and ninety million, nine hundred thousand (190.9 million) - based on 2017 estimate - with an average population growth rate of about 2.6%. It occupies 923,768 km2 land area situated between longitudes 3° and 15° east, and latitude 4° and 14° north. Nigeria is bounded by Cameroun in the East, Republic of Benin in the West, Niger in the North, and Chad in the North East. Its coast in the south is located on the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean (Nigeria – National Report, 2007). In Nigeria, the agricultural sector employs estimated 36.8% of the workforce (WB, 2019b)

Figure 1.

Map of Nigeria showing States participating in CADP. Source: GIS Laboratory, Geography and Environmental Science, University of Calabar, Nigeria.

Cross River state participated in the CADP, elected to focus on three commodities/value chains, namely, Oil Palm, Cocoa, and Rice with emphasis on production, processing and marketing among groups. Enugu state elected to focus on three commodities/value chains, namely, poultry, fruit trees and maize with emphasis on production, processing and marketing, among groups. Lagos state participated in the CADP with the government focusing on three value chains of Poultry, Aquaculture, and Rice. Kano state participated in CADP focusing on three value chains of; Rice, Dairy, and Maize. Kaduna State focused on three value chains of; maize, fruit trees and dairy production.

3.2. Data for the study

The study used secondary data that were collected in the five participating states (Cross River, Enugu and Lagos in the South; Kaduna and Kano States in the North) in 2017 by the Project for assessing the impact of the Commercial Agriculture Development Project. The data generating process was done using the Multi-stage sampling technique. In determining the sample size and distribution for each State, a few significant strata were considered, as it relates to the design and implementation of the CADP. These include (i) types of value chains, types of Commodity Interest Group (CIG), size of operation (small or medium) and gender. For the beneficiary category, the list of commodity interest group (CIG) beneficiaries in the various strata (producer, processor & marketer) provided by the State CADP office formed the sampling frame for the study. Beneficiaries were then randomly selected. The non-beneficiary category was purposively selected based on their willingness to participate in the survey. The data collected include demographic characteristics, total value of production, net sales, commodity prices, input prices, social capital and group membership, access to credit and income. All 2016 monetary values were computed at 2009 constant prices, i.e. 2009 = 100.

3.3. Analytical techniques

Analysis was done using Stata Version 14. The tools for data analysis included Foster, Greer and Thorbecke (FGT) poverty measures, Propensity Score Matching (PSM) and the Poverty Equivalent Growth Rate (PEGR). The statistical matching method is cross cutting being relevant to objectives 3 and 4.

3.3.1. Foster, Greer and Thorbecke (FGT) model of poverty measures

The FGT model was used to achieve part of objective 1 which is the poverty status of beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries before using the ATT to determine the impact of the CADP on them. Several methods exist in the literature for the analysis of poverty among households. However, it is important that a poverty index or a family of indices be decomposable by groups since different poor groups may not be uniformly poor. A method that is sensitive to this requirement was proposed by Foster et al. (1984) and had been widely applied (Oni and Olaniran, 2008; Akinlade 2012).

A common challenge in poverty analysis is deciding the poverty line (PL), the line that distinguishes the poor from the non-poor. Those above the poverty line are assumed to be able to attain some minimum living standard. Foster et al. (1984) proposed a family of poverty indices that accounts for varying degrees of poverty among poor individuals. For this study the poverty line was estimated from the two-third of mean per capita income of sampled households.

The computing expression for measurement of poverty by the Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) index is as follows:

| (1) |

Where,

= Poverty line defined as 2/3 of mean per capita income

= income of household,

= the number of poor households in sample N and

= the poverty index, whose value is conditioned by parameter α.

= degree of poverty aversion that takes the value 0,1or 2 (Foster et al., 1984).

For α = 0, Pα is simply m/N and called the head count (P0) which measures the incidence of poverty that is; proportion of the total population of a given group that is poor based on poverty line. α = 1 is the poverty gap index which measures the depth of poverty that is; on average how far the poor is from the poverty line; α = 2 is the squared poverty gap which measures the severity of poverty among households. It is interpreted as the amount of income required to raise people in poverty up to the poverty line. This indicator measures the extent to which individuals fall below the poverty line as a proportion of the poverty line.

Based on the FGT measures discussed above, the beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries were classified into poor and non-poor. The probit model was then used to analyse how socioeconomic variables influence the probability of being poor for both categories. The Probit model uses the cumulative normal function to model the probability of the occurrence of an event. The dependent variable is a Yes(1)/No(0) outcome given the regressors xi. Where p (y = 1|x) means the probability that an event occurs given the values of x, or explanatory variables. The estimated model is stated as

| (2) |

Where if the household is poor and 0 if otherwise; = vector of explanatory variables; = slope of coefficients, = 0,1,2…; = independently distributed error term; = number beneficiaries/non-beneficiaries.

The probability of being in poverty was determined in relation to the following variables stated explicitly as follows; x1=sex of household head (1) if male, (0) if otherwise; x2=age of household head (in years); x3 = household size (number); x4 = Educational status of household head (years); x5 = Credit access (1if household has access to credit; 0 if otherwise); x6 = farm size (hectares); x7 = farm experience (years); x8 = beneficiary status (1if beneficiary; 0 if non-beneficiary).

3.3.2. Propensity score matching (PSM)

The impact of CADP on poverty was determined using the Propensity Score Matching (PSM). PSM is a statistical matching technique that attempts to estimate the effect of a treatment or intervention by accounting for the covariates that predict receiving the treatment. Matching assumes that all relevant differences between the groups (i.e beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries) are captured by theirs observable xs; select from the non-treated pool a control group (non-beneficiaries) in which the distribution of observed variable is as similar as possible to the distribution in the treated group (Beneficiaries)Using Propensity Score Matching (PSM) (Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983; Heckman et al. 1999), 1142 samples: 655 beneficiaries, 487 non-beneficiaries were matched using PSM the matched sample (beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries) were tested for comparability. The results shows statistically insignificant difference in the explanatory variables used in the probit model between the matched groups of beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries. The match was deemed of good quality. The matched sample was then used to compute the Average Treatment Effect of the Treated (ATT) to determine the impact of the programme on the outcomes of poverty and commercialization. This is defined by Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983) as follows:

| E (Y1–Y0|D = 1) = E (Y1|D = 1) – E(Y0|D = 1) | (3) |

Where E (Y1|D = 1) is the observed outcome of the treated while participating in the programme, and E (Y0|D = 1) is the counterfactual outcome; that is the expected outcome had they not participated on the project. Standard errors using bootstrapping were computed as suggested by Lechner (2002). This method is popularly used to estimate standard errors in case analytical estimates are biased or unavailable.

We assessed the extent of commercialization of the CADP by calculating the ratio of value of sales to the value of production for each commodity for beneficiaries at baseline and endline and a comparison between baseline and endline was made. This was determined as follows:

| (4) |

The household commercialization index (HCI) to determine household specific level of commercialization is as specified by (Govereh et al., 1999; Strasberg et al., 1999). The index measures the ratio of the gross value of crop sales by household i in year j to the gross value of all crops produced by the same household i in the same year j expressed as a percentage. This index measures the actual response of CADP beneficiaries through the percentage of output being commercialized. Using the ATT discussed above, the impact of CADP on commercialization was determined.

3.3.3. Poverty Equivalent Growth Rate (PEGR)

In determining whether the CADP was Pro-poor, we follow the pro-poor growth methodology developed by Kakwani and Khandker (2004). This methodology proposes the Poverty Equivalent Growth Rate (PEGR); This is a measure of pro-poor growth that captures a direct linkage or monotonic relation with poverty reduction, indicating how the benefits of growth are shared by the poor and non-poor in the society. It is derived by multiplying the Pro-poor Growth Index (PPGI) by the growth rate of mean income. The baseline and end line data was used in estimating the PEGR thus;

| (5) |

Where = Poverty measure (a function of the poverty line z); z = poverty line; = mean income; = Lorenz function.

Growth is given by;

| (6) |

Where and is the mean income of beneficiaries for endline and baseline respectively.

Income distribution for both period is given by respectively. Then, total poverty elasticity can be written thus;

| (7) |

Decomposing this elasticity into the changes in poverty that can be attributed to growth and inequality :

| (8) |

Where;

| (9) |

| (10) |

Therefore, the PEGR is given as;

| (11) |

From Eq. (11) growth is pro-poor if is greater than . The larger the PEGR , the greater the percentage reduction in poverty between the two periods. If PEGR is greater than the actual growth rate, then growth is pro-poor but if PEGR is less than the actual growth rate, then growth is anti-poor.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Poverty status of beneficiaries (CADPB) and non-beneficiaries (N-CADPB) by socioeconomic characteristics

Table 1 shows the distribution of poverty Incidence, depth and severity across household socioeconomic characteristics. The result from sampled observation shows that the incidence of poverty (Po) is generally higher for N-CADPB and lower for CADPB. This may be as a result of their participation in the Project. For the beneficiaries, poverty incidence among the male is 0.014 while that of the female is 0.01; but for the non-beneficiaries, the Po for the male is 0.021 while that of the female is 0.026. The index of poverty depth (P1) for male beneficiaries is 0.531 which is lower than that of the female 0.791. This scenario is seen in the squared poverty gap (P2) index as well for both beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries where the index for the male is lower than that of the female. For CADPB, the P2 is 0.409 for male and 0.722 for female while that of NCADPB male is 0.687 and female is 0.835. On a general note, the indices for the female are higher than that of the male. This implies that male folks among the CADPB benefit more in terms of poverty reduction. This is consistent with the findings of (Ogunniyi et al., 2017) (Rufai et al., 2019), and (Ogundipe et al., 2019) which indicates poverty is higher among females or female headed households.

Table 1.

Distribution of Poverty Incidence, Depth and Severity across Household Socio economic characteristics.

| Socio-economic characteristics | Non-Beneficiaries |

Beneficiaries |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | P1 | P2 | P0 | P1 | P2 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 0.021 | 0.768 | 0.687 | 0.014 | 0.531 | 0.409 |

| Female |

0.026 |

0.871 |

0.835 |

0.013 |

0.791 |

0.772 |

| Age | ||||||

| <25 | 0.037 | 0.367 | 0.305 | 0.034 | 0.424 | 0.423 |

| 26–35 | 0.025 | 0.927 | 0.925 | 0.021 | 0.814 | 0.786 |

| 36–45 | 0.018 | 0.721 | 0.646 | 0.014 | 0.579 | 0.482 |

| 46–55 | 0.023 | 0.784 | 0.702 | 0.010 | 0.526 | 0.403 |

| 56–65 | 0.017 | 0.821 | 0.727 | 0.010 | 0.494 | 0.352 |

| >65 |

0.040 |

0.827 |

0.759 |

0.011 |

0.451 |

0.277 |

| Household Size | ||||||

| 1–5 | 0.042 | 0.921 | 0.992 | 0.023 | 0.969 | 0.963 |

| 6–10 | 0.020 | 0.737 | 0.662 | 0.011 | 0.383 | 0.318 |

| 11–15 | 0.005 | 0.740 | 0.637 | 0.005 | 0.527 | 0.353 |

| >15 |

0.002 |

0.789 |

0.672 |

0.004 |

0.686 |

0.498 |

| Educational status | ||||||

| No formal | 0.004 | 0.680 | 0.624 | 0.015 | 0.379 | 0.167 |

| Primary | 0.018 | 0.730 | 0.621 | 0.009 | 0.580 | 0.485 |

| Secondary | 0.025 | 0.763 | 0.670 | 0.015 | 0.518 | 0.395 |

| Tertiary |

0.020 |

0.820 |

0.769 |

0.016 |

0.617 |

0.518 |

| Credit Access | ||||||

| Yes | 0.025 | 0.842 | 0.792 | 0.017 | 0.738 | 0.646 |

| No |

0.015 |

0.328 |

0.207 |

0.14 |

0.590 |

0.480 |

| Farm Size | ||||||

| 1–5 | 0.003 | 0.773 | 0.625 | 0.002 | 0.825 | 0.689 |

| 6–10 | 0.014 | 0.802 | 0.742 | 0.014 | 0.558 | 0.448 |

| 11–15 | 0.056 | 0.526 | 0.445 | 0.003 | 0.708 | 0.502 |

| >15 |

0.570 |

0.599 |

0.384 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| Farm Experience | ||||||

| 1–10 | 0.028 | 0.851 | 0.815 | 0.019 | 0.710 | 0.667 |

| 11–20 | 0.023 | 0.763 | 0.689 | 0.012 | 0.562 | 0.471 |

| 21–30 | 0.017 | 0.754 | 0.667 | 0.011 | 0.429 | 0.271 |

| >30 | 0.004 | 0.769 | 0.658 | 0.009 | 0.519 | 0.307 |

Source: Author's own estimation using CADP Nigeria Data, 2019

For the different age sub groups, P0 is higher for the N-CADPB in all subgroups and lower for CADPB. Among the beneficiaries however, the poverty incidence is found to be reducing as the age increases; this holds true for P1 and P2 as well. For CADPB, the P0 for the under 25 category is 0.034 which is lower than the 0.037 of their N-CADPB counterpart. However, the P1 for this age category for CADPB is slightly higher at 0.424 than that of their NCADPB counterparts which is 0.367. The same scenario is reflected in the P2 which is 0.423 for CADPB and 0.305 for N-CADPB. For the 26–35 age category however, the CADPB appear better off as the P0, P1 and P2 are lower for CADPB compared to N-CADPB. For CADPB, the P0, P1 and P2 are 0.021, 0.814 and 0.786 respectively; whereas for the N-CADPB, the indices are: 0.025, 0.927 and 0.925. This order is maintained in the remaining age categories.

As expected, the indices are found to be reducing as level of education and years of farming experience increases. This scenario holds true for both CADPB and N-CADPB. This is in line with apriori expectations because level of education and years’ of experience are expected to be brought to bear in farming practices and consequently improvement in yield and income. For farm size, poverty incidence of N-CADPB is higher than that of CADPB and is found to be increasing as farm size increases. For the CADPB however, the sub group of 6–10 has had the highest poverty incidence and decreasing as the farm size increases. For credit access, among the CADPB, P0, P1 and P2 are 0.017, 0.738 and 0.646 respectively; these are higher compared to those who did not access credit with the indices standing at 0.14, 0.590 and 0.480. These results are quite interesting as credit depending on the source and the terms have a tendency of further immiserating the poor. On a general note, the indices of poverty incidence depth and gap are higher for non-beneficiaries compared to the beneficiaries.

Table 2 shows an aggregation of the indices for both beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries and the summary presented. The P0 index for beneficiaries is 0.0140 implying that 1.4% of the beneficiaries are living below the poverty line of N171, 094.30 ($475.26). For non-beneficiaries, the P0 is 0.0216 which implies that about 2.16% of them live below the poverty line. The poverty gap index P1 = 0.562 for beneficiaries is lower than that of non-beneficiaries which is 0.787. This proves that beneficiaries will require the lowest percentage of expenditure to liberate the poor to a non-poor condition. The poorest among the poor within the beneficiaries account for 45.15% of the poor population (P2 = 0.4155); which is lower than that of non-beneficiaries which is 0.7143. The lower poverty incidence among beneficiaries is probably due to their participation in CADP which makes them better off compared to their counterparts who did not participate in the Project. This is in line with the findings of Oni and Olaniran (2008) who compared the FGT poverty indices of Fadama II project beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries in Oyo State, South West Nigeria, and found that the indices were lower for the beneficiaries compared to non-beneficiaries.

Table 2.

Summary poverty status of respondents.

| Poverty measures | Non-Beneficiaries | Beneficiaries | Pooled |

|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | 0.0216 | 0.0140 | 0.0173 |

| P1 | 0.7870 | 0.5620 | 0.6757 |

| P2 | 0.7143 | 0.4515 | 0.5843 |

Source: Author's own estimation using CADP Nigeria Data, 2019

As stated earlier, the indices for beneficiaries are lower than that of non-beneficiaries which implies that the CADP has the potential to reduce poverty. The poverty depth and severity indices showed that non-beneficiaries are farther away from the poverty line and that poverty is more severe among the non-beneficiaries compared with beneficiaries.

4.2. Impact of CADP on poverty status using income as a proxy

Table 3 reports the estimates of the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) - the impact of participation in CADP on poverty of beneficiaries using income as a proxy. The income difference indicator of 446,073.89 is positive and significant at the 5% level implying that CADP positively impacted the income of beneficiaries compared to non-beneficiaries. The income is used as a proxy for welfare to assess the impact on poverty status of beneficiaries. It shows that those who participated in CADP have their income increased by N446, 073.89 ($ 1,239.09)∗ and are better off in terms of their welfare compared to those who did not participate in the program. The Average Treatment Effect (ATE) on income for the CADPB and N-CADPB selected at random was lower for the entire sample (266,244.001). The Average Treatment Effect on the Untreated (ATU) reveals the treatment on randomly selected CADPB and N-CADPB before treatment (that is, the counterfactual outcome if they were not treated); the result was also positive. This result confirms that the CADP had the potential to improve the welfare of beneficiaries.

Table 3.

Impact of CADP on Poverty Status using income as a proxy.

| Variable | Sample | Treated | Controls | Difference | S.E. | stat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm Inc 16 | Unmatched | 1,980,508.82 | 1,107,730.02 | 872,778.799 | 155236.851 | 5.62 |

| ATT | 1,597,775.52 | 1,151,701.63 | 446,073.892 | 139976.094 | 3.19∗∗ | |

| ATU | 1,095,613.62 | 1,234,003.29 | 138,389.674 | . | . | |

| ATE | 266,244.001 | . | . |

Note: ∗∗∗Significant at 1%level, ∗∗ Significant at 5%level,∗Significant at 10%.

∗1USD = 360 Nigerian Naira.

Source: Author's own estimation using CADP Nigeria Data, 2019

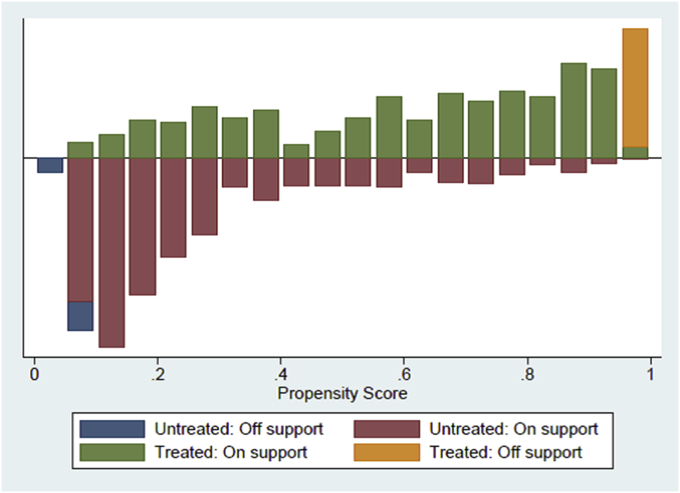

Figure 2 shows the common support region-a visual presentation of the distribution of the estimated propensity scores. This indicates that common support condition is satisfied as there is a substantial overlap in the distribution scores of both the CADPB and N-CADPB in terms of income.

Figure 2.

Distribution of propensity scores and common support region. Source: Figure generated using STATA 14 Software.

4.3. Impact of CADP on commercialization of beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries

Table 4 shows impact of participation in CADP on commercialization among the participants. It shows the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) which is the impact on the treated taking into consideration the characteristics of participants and non-participants. The ATT of 0.08 is positive and significant at the 10% level of significance. The positive value shows that CADP has a significant impact on the commercialization of participants. Also that those who participated in CADP will have their commercialization increased index by 0.9% compared to those who did not participate in the program. This indicate that taking part in CADP has led to increase in commercialization among the participants leading to increase in revenue generated by the participants. This could also lead to overall improvement in welfare of the participants. The ATU shows the spillover effect of the Project on non-participants, while the ATE is the intention to treat which excludes the spillover.

Table 4.

Impact of CADP on commercialization.

| Variable | Sample | Treated | Controls | Difference | S.E. | t-stat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercialization Index | Unmatched | 0.09129655 | 0.07731608 | 0.01398047 | 0.00481676 | 2.9 |

| ATT | 0.08334828 | 0.07368363 | 0.00966465 | 0.00569133 | 1.7∗ | |

| ATU | 0.07715206 | 0.07341133 | -0.0037407 | . | . | |

| ATE | 0.00182971 | . | . |

Note: ∗∗∗Significant at 1%level, ∗∗Significant at 5%level,∗Significant at 10% level.

Source: Author's own estimation using CADP Nigeria Data, 2019

4.4. Determining the pro-poor growth of CADP

4.4.1. Pro-poor indices for CADP beneficiaries

Table 5 provides estimates and confidence intervals for the growth rate of beneficiaries between 2009 and 2016 which is the variable g. There are also estimates of two other pro-poor indices apart from the PEGR index of Kakwani and Son (2003); Ravallion and Chen (2003) index, Kakwani and Pernia (2000) index.

Table 5.

Pro-poor indices of CADP beneficiaries.

| Pro-poor indices | Estimate | STE | LB | UB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth rate(g) | 1.87554 | 0.236532 | 1.410867 | 2.340214 |

| Ravallion and Chen (2003) index | 6.347877 | 9.763965 | -12.833702 | 25.529457 |

| Ravallion and Chen (2003) – g | 4.472337 | 9.768689 | -14.718523 | 23.663196 |

| Kakwani and Pernia (2000) index | 0.814998 | 0.088767 | 0.640613 | 0.989382 |

| PEGR index | 1.528561 | 0.235873 | 1.065181 | 1.99194 |

| PEGR – g | -0.34698 | 0.153075 | -0.647699 | -0.04626 |

STD: standard error, LB: lower bound of 95% confidence interval, UB: upper bound of 95% confidence interval.

Source: Author's own estimation using CADP Nigeria Data, 2019

From Table 5 which provides pro-poor estimates for CADP Beneficiaries using the PEGR as earlier discussed, the mean growth rate in income of 1.875, is higher than the PEGR of 1.528. For the poor to have benefitted from the intervention, the PEGR should be higher than the actual growth rate. With this result, when the PEGR is subtracted from the growth rate, a negative value is obtained. This implies that CADP benefitted mainly the rich and not the poor. Also, the PPGI Kakwani & Pernia index for beneficiaries of 0.815 lies between 0 and 1 which indicates a trickle down growth. The implication of this is that the poor received proportionally less of the benefits of growth than the non-poor (that is, poverty decreases still). This is in line with the findings of Gafaar and Osinubi (2005) that the very poor has not benefitted in the growth in Nigeria within the period analyzed, but contrary to the findings of Akinlade (2012) who assessed the pro-poor growth of Fadama II Project in Nigeria and found that the PEGR for participants was higher than that of non-participants which implied that the Fadama II Project was pro-poor. It is important that the poor is properly targeted in development programmes in order to reduce poverty and reduce the inequality between the poor and the rich.

5. Conclusion

Considering the empirical results obtained from this study, we can conclude that with the implementation of the CADP, there is a reduction in the poverty indices of the beneficiaries. Specifically, the Po index for beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries indicates that 1.4% and 3.6% of beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries respectively are living below the poverty line. The poorest among the poor of the beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries account for 45.15% and 71.43% of the poor population respectively. This indicates that the CADP is poverty decreasing.

On commercialization, we found that the programme led to a statistically significant increase in the commercialization index of beneficiaries. Beneficiaries had their commercialization index increased by at least 0.9%

The pro-poorness of the CADP was analyzed by computing the PEGR and the PPGI Kakwani and Pernia indices. The results from both indices shows that the poor received proportionally less of the benefit of growth than the non-poor, implying that the CADP was not pro-poor.

Since CADP decreases the probability of being poor and increases the commercialization index of participants, If the project is to be continued the following implementation options are recommended; the project should be scaled up to accommodate more beneficiaries. The project design and targeting mechanism should be reviewed to make the programme pro-poor. Availability and up-to-date social register would prove indispensable in targeting the poor. These options should also be a policy takeaway for other agricultural intervention programmes in Nigeria.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Etuk, Ekanem Abasiekong: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Ayuk, Josephine Oluwatoyin: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Agber T., Iortima P.I., Imbur E.N. Lessons from implementation of Nigeria’s past national agricultural programs for the transformation agenda. Am. J. Res. Commun. 2013;1(10):238–253. [Google Scholar]

- Akinlade R.J. Impact of Fadama-II project on poverty reduction of rural households in Nigeria. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Res. 2012;2(2):18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Asselin L.-M. Analysis of multidimensional poverty: theory and case studies. Econ. Stud. Inequality, Soc. Exclusion Well-Being. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Asselin Louis-Marie, Dauphin Anyck. 2001. Poverty Measurement: A Conceptual Framework.https://www.pep-net.org/sites/pepe-et.org/files/typo3doc/pdf/asselin/Poverty.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bako M.M. Climate change vulnerability assessment in parts of Northern Nigeria. Niger. J. Trop. Geograp. 2013;4(2):449–470. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Ortega C., Lederman D. 2005. Agriculture and National Welfare Around the World: Causality and International Heterogeneity since 1960.https://ssrn.com/abstract=654562 Retrieved from SSRN: [Google Scholar]

- Byerlee D., Diao X., Jackson C. World Bank; 2009. Agriculture, Rural Development and Pro-poor Growth: Country Experiences in the post-reform Era; p. 3. Agriculture and Rural Development Discussion Paper 21. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. The Multidimensional Poverty Assessment Tool: a new framework for measuring ruralpoverty. Dev. Pract. 2010;20(7):887–897. [Google Scholar]

- Coudouel A., Hentschel J.S., Wodon Q.T. 2002. Poverty Measurement and Analysis. Volume 1-Core Techniques and Cross-Cutting Issues. [Google Scholar]

- Daneji M. Agricultural development intervention programmes in Nigeria (1960 to date): a review. Savannah J. Agri. 2011;6(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Datt G., Ravallion M. Farm productivity and rural poverty in India. J. Dev. Stud. 1998;34(4):62–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fafchamps M., Shilpi F. The spatial division of labour in Nepal. J. Dev. Stud. 2003;39(6):23–66. View Record in Scopus Google Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . Accra; 2017. Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition in Africa 2016. The Challenges of Building Resilience to Shocks and Stresses. [Google Scholar]

- Foster J., Greer J., Thorbecke E. A class of decomposable poverty measures. Econometrica. 1984;52(3):761–766. http://www.jstor.org/stable/ Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/4814881_A_Class_of_Decomposable_Poverty_Indices. [Google Scholar]

- Gafaar O.A., Osinubi T.S. Proceedings of the German Development Economics Conference, Kiel 2005/Verein für Socialpolitik, Research Committee Development Economics, No. 24. 2005. Macroeconomic policies and pro-poor growth in Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett J., Chowdhury S. Google Scholar; 2004. Urban–Rural Links and Transformation in Bangladesh: A Review of the Issues. Care-Bangladesh Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Goletti F. Making Markets Work Better for the Poor, ADB/DfID. Agrifood Consulting International. Google Scholar; 2005. Agricultural Commercialization, value chains and poverty reduction. [Google Scholar]

- Govereh J., Jayne T.S., Nyoro J. the Department of Agricultural Economics and the Department of Economics, Michigan State University; 1999. Smallholder Commercialization, Interlinked Markets and Food Crop Productivity: Cross Country Evidence in Eastern and Southern Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman J.J., Lalonde R.J., Smith J.A. The economics and econometrics of active labor market programs, Handbook of Labor Economics. In: Ashenfelter O., Card D., editors. Vol. 1. 1999. pp. 1865–2097. (Handbook of Labor Economics). [Google Scholar]

- IFAD . The State of World Rural Poverty: A Profile for Africa. IFAD; Rome: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- IFAD . 2016. Federal Republic of Nigeria: Community-Based Agricultural and Rural Development Programme. Retrieved from https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714182/39731335/Nigeria%20CBARDP%20PPA%20-%20full%20report%20for%20web.pdf/b2c60d57-eb63-4b46-8889-6ed3ac1ed133. [Google Scholar]

- Imahe O.J., Alabi R.A. Determinants of agricultural productivity in Nigeria. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2005;3:269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Iwuchukwu J.C., Igbokwe E.M. 2012. Lessons from Agricultural Policies and Programmes in Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Jaleta M., Gebremedhin B., Hoekstra D. ILRI; Nairobi: 2009. ʻSmallholder Commercialization: Processes, Determinants and Impactʼ.https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/27 ILRI Discussion Paper 18. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Jmorova A. Pro-poor growth: definition, measurement and policy issues. J. Law, Policy Glob. 2017;5:2012. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/85397/ MPRA Paper No. 85397. Available Online at. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston Bruce F., Mellor John W. The role of agriculture in economic development. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961;51(4) www.jstor.org/stable/3856951 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kakwani N., Pernia E. What is pro-poor growth? Asian Dev. Rev. Stud. Asian Pac. Econ. Issues. 2000;18:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kakwani N., Son H. Poverty equivalent growth rate. Rev. Income and Wealth. 2008;5(4):643–655. [Google Scholar]

- Kakwani N., Khandker S. International Poverty Centre.; 2004. Pro-poor Growth: Concepts and Measurements with Country Case Studies (Working Paper No. 1) [Google Scholar]

- Kraay Aart. World Bank; Washington, D.C: 2004. When Is Growth Pro-poor? Cross-Country Evidence.https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/14731 Policy Research Working Paper; No.3225. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner M. Program Heterogeneity And Propensity Score Matching: An Application To The Evaluation Of Active Labor Market Policies. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2002;84(2):205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Love C. 2020. Impact of Selected Agricultural Policies and Intervention Programs in Nigeria-1960.https://www.irglobal.com/article/impact-of-selected-agricultural-policies-and-intervention-programs-in-nigeria-1960-till-date (Living Attorneys) Till Date retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Mansuri G. Community-based and –driven development: A critical review. World Bank Res. Obs. 2004;19(1):1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Agriculture and social protection for poverty reduction in ECOWAS. Matthew O.A., Osabohien R., Ogunlusi T.O., Edafe O., Amoo E.O.(, editors. Cogent Arts Humanities. 2019;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch N. Vol. 31. Institute of Development Studies; Sussex: 2000. (Tracking Pro-poor Growth. ID21 Insights No). [Google Scholar]

- Ngene A.A. 2013. Assessment of Commercial Agriculture Development Project in Enugu State, Nigeria. Master of Science (M.Sc.) thesis in Agriculture Extension, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Retrieved from http://www.unn.edu.ng/publications/files/Ngene%20Project%20-%20Preliminary%20pages.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundipe A.A., Oduntan E.A., Ogunniyi A.I., Olagunju K.O. Agricultural productivity, poverty reductionand inclusive growth in Africa: linkages and pathways. Asian J. Agri. Extension, Econom. Sociol. 2017;18(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundipe A.A., Ogunniyi A., Olagunju K., Asaleye A. Poverty and income inequality in rural agrarian household of southwestern Nigeria: the gender perspective. Open Agric. J. 2019;13:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunniyi A., Oluseyi O.K., Adeyemi O., Kabir S.K., Philips F. Scaling up agricultural innovation for inclusive livelihood and productivity outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: the case of Nigeria. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2017;29:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Okezie C.A., Nwonsu A.C., Okezie C.R. An assessment of the extent of commercialization of agriculture in abia state. Nigeria. Agric. J. 2008;3(2):129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Oni O.A. Livelihood, agroecological zones and poverty in rural Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci. 2014;6(2):103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Oni O.A., Olaniran O.T. An analysis of poverty status of Fadama II and non Fadama II beneficiaries in rural Oyo state, Nigeria. J. Rural Econom. Dev. 2008;17(1):55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Osmani S. Vol. 1. International Poverty Center; Brazil: 2005. (Defining Pro-poor Growth). [Google Scholar]

- Ozoani S.E. Appraisal of agricultural programmes in Nigeria. Int. J. Innovat. Agri. Biol. Res. 2019;7(1):86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pingali P. From subsistence to commercial production system: The transformation of Asian agriculture. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1997;24:628–634. [Google Scholar]

- Pingali P.L., Rosegrant M.W. Agricultural commercialization and diversification: processes and policies. Food Pol. 1995;20(3):171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Pingali P., Aiyar A., Abraham M., Rahman A. Transforming Food Systems for a Rising India. Palgrave Studies in Agricultural Economics and Food Policy. 2019. Enabling smallholder prosperity through commercialization and diversification. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion M., Chen S. Measuring pro-poor growth. Econ. Lett. 2003;78:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion M. Pro-Poor Growth: A Primer. Development Research Group, The World Bank; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nigeria – National Report Report of Nigeria's national population commission on the 2006 census. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2007;33(1):206–210. www.jstor.org/stable/25434601 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum P.R., Rubin D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rufai M., Ogunniyi A., Salman K., Oyeyemi M., Salawu M. Migration, labor mobility and household poverty in Nigeria: a gender analysis. Economies. 2019;7(4):101. MDPI AG. [Google Scholar]

- Salisu R. Ahmadu Bello University Zaria; 2012. Impact of Commercial Agricultural Development Project O Productivity and Food Security Status of Maize Farmers in Kaduna State, Nigeria.http://kubanni.abu.edu.ng/jspui/bitstream/123456789/8146/1/IMPACT%20OF%20COMMERCIAL%20AGRICULTURAL%20DEVELOPMENT%20PROJECT%20ON%20PRODUCTIVITY%20AND%20FOOD%20SECURITY%20STATUS%20OF%20MAIZE%20FARMERS%20IN%20KADUNA%20STATE%2C%20NIGERIA.pdf PhD dissertation. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Poverty: an ordinal approach to measurement. Econometrica. 1976;44(2):219–231. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1912718 URL: [Google Scholar]

- Sen A.K. Development: Which Way Now? Econ. J. 1983;93(2):754–757. [Google Scholar]

- Son H. A Note on Pro-Poor Growth. Econ. Lett. 2004;82:307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Strasberg P.J, Jayne T.S., Yamano T., Nyoro J., Karanja D., Strauss J. Effects of agricultural commercialization on food crop input use and productivity in Kenya. Michigan State University International Development Working Papers No. 1999;71 [Google Scholar]

- Timmer, C. P. (1988). The Agricultural Transformation. In: Handbook of Development Economics Vol 1. Eds: Chenery, H. & Srinivasan, T.N., Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., 1988.

- Todaro M.P. Economic Development in the Third World. Longman; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP . 1990. Human Development Report 1990: Concept and Measurement of Human Development. New York.http://www.hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr1990 Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- United Development Programme (UNDP) 2006. Poverty in Focus, International Poverty Centre.www.ipcig.org/pub/IPCPovertyInFocus9.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Von Braun J. Agricultural commercialization, economic development, and nutrition. Johns Hopkins University; Baltimore, Maryland: 1995. pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Von Thunen J.H. Isolated State: An English Edition of Der Isolierte Staat. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . Agriculture for Development; Washington D.C: 2007. World Development Report 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . Agriculture for Development. World Bank; Washington, D.C: 2007. World Development Report 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2009. The World Bank Project Appraisal Document (PAD). Document Prepared for the Commercial Agriculture Development Project (CADP) in Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2019. Agriculture and Food.https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/overview Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank, 2019b. Employment in Agriculture (%total employment)(Modeled ILO estimates, Nigeria) Available at: https://www.data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.AGR.FMPL,ZS? Locations=Nigeria

- Yoon-Doon K., Yoon S. A note on the improvement of evaluation system in wholesale markets of agricultural and fisheries products. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2009;6:1604–1612. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.