Abstract

Background: Chemotherapy is suggested to use in all stages of pancreatic cancer. Is it reasonable to recommend chemotherapy for all PDAC patients? It is necessary to distinguish low-risk PDAC patients underwent pancreatectomy, who may not lose survival time due to missed chemotherapy and not need to endure pain, nausea, tiredness, drowsiness, and breath shortness caused by chemotherapy.

Methods: Nomograms were constructed with basis from the multivariate Cox regression analysis. X-tile software was utilized to perform risk stratification. Survival curves were used to display the effect of chemotherapy in different risk-stratification.

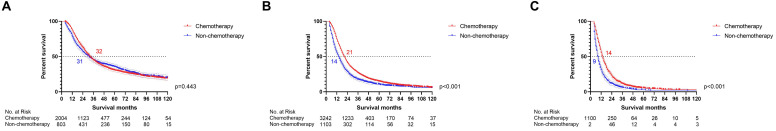

Results: All of the significant variables were used to create the nomograms for overall survival (OS). The total risk score of each patient was calculated by summing the scores related to each variable. X-tile software was utilized to classify patients into high-risk (score >283), median-risk (197<score ≤283), and low-risk (score ≤197) according to the total risk score. The low-risk PDAC patients after pancreatectomy cannot gain survival benefit from chemotherapy after surgery (p=0.443). Moreover, chemotherapy improved survival for patients with resected PDAC in the median-risk (p<0.001) and high-risk (p<0.001) groups.

Conclusions: our research constructed a new risk-scoring system based on survival nomogram to screen low-risk PDAC patients after pancreatectomy and confirmed that those can avoid enduring side effects caused by chemotherapy without affecting the survival time.

Keywords: PDAC, nomogram, chemotherapy, SEER database, surgical resection

Introduction

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma retains the worst prognosis among all gastrointestinal malignancies with growing steadily incidence in the last two decades 1. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the main histological type of pancreatic tumors and accounts for about 85% of cases 2, 3. Multiple factors are responsible for the poor prognosis, including early metastatic locoregional, unusual aggressiveness, the lack of effective systemic therapies and distant spread of pancreatic cancer cells 4.

Chemotherapy is suggested, by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and the European Society for Medical Oncology-European Society of Digestive Oncology (ESMO-ESDO) guidelines, to use in all stages of pancreatic cancer 5, 6. However, is it reasonable to recommend chemotherapy for all PDAC patients? A meta-analysis including five randomized controlled trials showed that adjuvant chemotherapy only provided an extra 3 months of median survival time for patients with resected PDAC 7. A recent study confirmed that chemotherapy even cannot provide survival benefit for patients with early-stage PDAC 8. Moreover, experiences from the treatment of other tumors, such as colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, are able to affirm that early-stage tumors can be completely cured by surgical resection. Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish low-risk PDAC patients after pancreatectomy, who may not lose survival time due to missed chemotherapy and not need to endure pain, nausea, tiredness, drowsiness, and breath shortness caused by chemotherapy.

An effective risk scoring system is crucial to screen low-risk PDAC patients after pancreatectomy. Survival nomogram is a two-dimensional diagram giving a computation of mathematical functions and can calculate the risk score of independent prognostic factors based on survival time. Hence, the purpose of this study is to construct an effective scoring system based on survival nomogram stratifying the risk of patients with resected PDAC, and compare the effect of chemotherapy on PDAC patients after surgery at different risk levels.

Materials and Methods

Patients

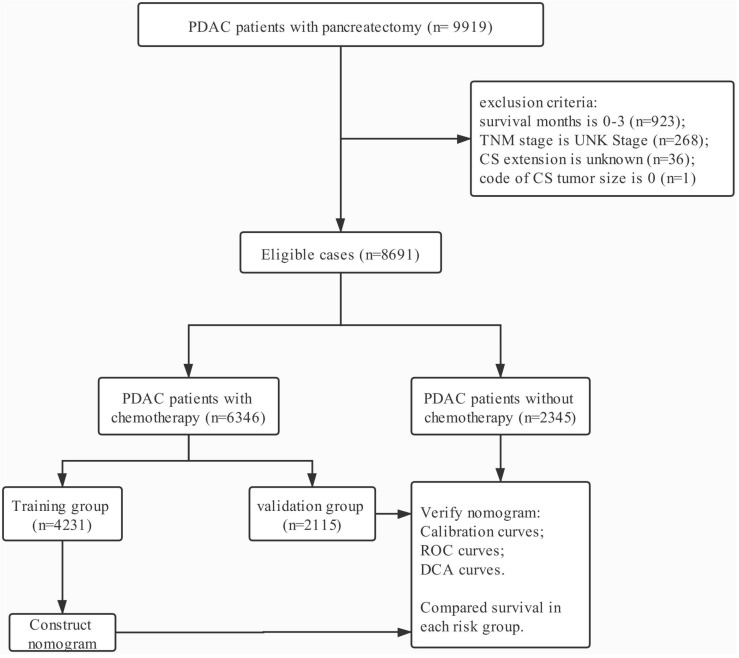

Data in this retrospective analysis were extracted from the SEER linked database. The target population was limited to the patients with resected PDAC (ICD-O-3: 8140, 8141, 8144, 8160, 8170, 8210, 8211, 8255, 8260, 8261, 8263, 8290, 8310, 8323, 8342, 8350, 8430; RX Summ--Surg Prim Site (1998+): 10-90) diagnosed in the periods of 2004-2015, 9,919 patients in total. The exclusion criteria: survival months is 0-3 (n=923); TNM stage is UNK Stage (n=268); CS extension is unknown (n=36); code of CS tumor size is 0 (n=1). The final study sample contained 8,691 patients (Fig. 1). All procedures performed in this study were in line with the STROCSS criteria 9.

Figure 1.

The flow chart.

For each patient, the following data was acquired: age at diagnosis, gender, race, tumor size, tumor location, grade, T stage, N stage, M stage, regional nodes examined (RNE), extension, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The final sample included 6,346 PDAC patients with chemotherapy and 2,345 ones without chemotherapy. PDAC patients with chemotherapy were used to build survival nomogram due to who received standard treatment as the guidelines, and then inconsistently separated into two groups (training group, n = 4231 and validation group, n = 2115). According to the eighth edition AJCC staging criteria, T staging was re-performed based on the tumor size (T1a-b: ≤1 cm; T1c: 1-2 cm T2: 2-4 cm; T3: >4 cm) and N staging was also re-classified based on the number of positive lymph nodes (N0: 0 positive regional lymph nodes; N1: one to three positive regional lymph nodes; N2: four or more positive regional lymph nodes). According to the code of CS extension, this study classified patients who were equivalent to the T1-2 staging in the seventh edition of AJCC as localized tumor, and those who matched with T3 staging as extrapancreatic extension.

Statistical Analysis

An odds ratio (OR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI) were evaluated by univariable and multivariate Cox regression model. Variables with significant differences in univariate analysis were included in the Cox regression model for multivariate analysis. With the multivariate analysis results as the basis, by means of R 3.6.1 software (Institute for Statistics and Mathematics, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org/), nomograms were constructed. The prognostic prediction nomograms were validated by time-dependent receiver operating characteristics (ROC), decision curve analysis (DCA) and calibration curves. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS statistics trial ver. 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All reported p-values lower than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The characteristics of patients with resected PDAC enrolled from the SEER database are summarized in Table 1. The cohort is predominantly elderly patients (>60-year-old, 69.08%) with pancreatic head cancer (73.93%) in this study. Most of resected tumors are between 2 and 4 cm in size (T2, 53.85%). Moreover, metastatic lymph nodes were detected in 5,095 (58.62%) patients. Meanwhile, this study displayed extrapancreatic extension in 81.50% of patients. Patients receiving chemotherapy reach 73.02% of the entire cohort. Nevertheless, PDAC patients with limited extension and N0 stage incline to give up chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with PDAC after surgery

| Characteristics | Total (n=8691) | With chemotherapy(n=6346) | Without chemotherapy (n=2345) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training group (n=4231) | Verification group (n=2115) | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 4266 | 49.09% | 2051 | 48.48% | 1047 | 49.50% | 1168 | 49.81% |

| Male | 4425 | 50.91% | 2180 | 51.52% | 1068 | 50.50% | 1177 | 50.19% |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| ≤40 | 106 | 1.22% | 49 | 1.16% | 31 | 1.47% | 26 | 1.11% |

| 41-50 | 605 | 6.96% | 318 | 7.52% | 182 | 8.61% | 105 | 4.48% |

| 51-60 | 1976 | 22.74% | 1081 | 25.55% | 506 | 23.92% | 389 | 16.59% |

| 61-70 | 3020 | 34.75% | 1557 | 36.80% | 795 | 37.59% | 668 | 28.49% |

| 71-80 | 2366 | 27.22% | 1042 | 24.63% | 516 | 24.40% | 808 | 34.46% |

| >80 | 618 | 7.11% | 184 | 4.35% | 85 | 4.02% | 349 | 14.88% |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 5527 | 63.59% | 2809 | 66.39% | 1394 | 65.91% | 1324 | 56.46% |

| Unmarried/NOS | 3164 | 36.41% | 1422 | 33.61% | 721 | 34.09% | 1021 | 43.54% |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 7243 | 83.34% | 3533 | 83.50% | 1800 | 85.11% | 1910 | 81.45% |

| Black | 867 | 9.98% | 431 | 10.19% | 189 | 8.94% | 247 | 10.53% |

| Other/NOS | 581 | 6.69% | 267 | 6.31% | 126 | 5.96% | 188 | 8.02% |

| Tumor location | ||||||||

| Head | 6425 | 73.93% | 3205 | 75.75% | 1581 | 74.75% | 1639 | 69.89% |

| Body/Tail | 1380 | 15.88% | 624 | 14.75% | 339 | 16.03% | 417 | 17.78% |

| Other | 886 | 10.19% | 402 | 9.50% | 195 | 9.22% | 289 | 12.32% |

| Pathological grade | ||||||||

| I | 780 | 8.97% | 358 | 8.46% | 161 | 7.61% | 261 | 11.13% |

| II | 3857 | 44.38% | 1852 | 43.77% | 908 | 42.93% | 1097 | 46.78% |

| III | 2859 | 32.90% | 1397 | 33.02% | 729 | 34.47% | 733 | 31.26% |

| IV | 71 | 0.82% | 40 | 0.95% | 17 | 0.80% | 14 | 0.60% |

| Unknown | 1124 | 12.93% | 584 | 13.80% | 300 | 14.18% | 240 | 10.23% |

| T stage | ||||||||

| T1a-b | 201 | 2.31% | 69 | 1.63% | 34 | 1.61% | 98 | 4.18% |

| T1c | 1173 | 13.50% | 517 | 12.22% | 278 | 13.14% | 378 | 16.12% |

| T2 | 4680 | 53.85% | 2313 | 54.67% | 1163 | 54.99% | 1204 | 51.34% |

| T3 | 1858 | 21.38% | 926 | 21.89% | 459 | 21.70% | 473 | 20.17% |

| T4 | 591 | 6.80% | 324 | 7.66% | 142 | 6.71% | 125 | 5.33% |

| Tx | 188 | 2.16% | 82 | 1.94% | 39 | 1.84% | 67 | 2.86% |

| N stage | ||||||||

| N0 | 2975 | 34.23% | 1357 | 32.07% | 676 | 31.96% | 942 | 40.17% |

| N1 | 3231 | 37.18% | 1629 | 38.50% | 813 | 38.44% | 789 | 33.65% |

| N2 | 1864 | 21.45% | 944 | 22.31% | 479 | 22.65% | 441 | 18.81% |

| Nx | 621 | 7.15% | 301 | 7.11% | 147 | 6.95% | 173 | 7.38% |

| M stage | ||||||||

| M0 | 8148 | 93.75% | 3959 | 93.57% | 1984 | 93.81% | 2205 | 94.03% |

| M1 | 543 | 6.25% | 272 | 6.43% | 131 | 6.19% | 140 | 5.97% |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||||

| Neoradiotherapy | 581 | 6.69% | 387 | 9.15% | 184 | 8.70% | 10 | 0.43% |

| RadiotherapyA | 2861 | 32.92% | 1797 | 42.47% | 897 | 42.41% | 167 | 7.12% |

| No | 5249 | 60.40% | 2047 | 48.38% | 1034 | 48.89% | 2168 | 92.45% |

| RNE | ||||||||

| ≤5 | 1629 | 18.74% | 751 | 17.75% | 372 | 17.59% | 506 | 21.58% |

| 6-10 | 1633 | 18.79% | 772 | 18.25% | 363 | 17.16% | 498 | 21.24% |

| 11-15 | 1855 | 21.34% | 914 | 21.60% | 441 | 20.85% | 500 | 21.32% |

| 16-20 | 1452 | 16.71% | 721 | 17.04% | 390 | 18.44% | 341 | 14.54% |

| >20 | 1997 | 22.98% | 1014 | 23.97% | 519 | 24.54% | 464 | 19.79% |

| NOS | 115 | 1.32% | 49 | 1.16% | 30 | 1.42% | 36 | 1.54% |

| Extension | ||||||||

| Localized | 1608 | 18.50% | 684 | 16.17% | 350 | 16.55% | 574 | 24.48% |

| Extrapancreatic | 7083 | 81.50% | 3547 | 83.83% | 1765 | 83.45% | 1771 | 75.52% |

RNE: Regional nodes examined; NOS: Not otherwise specified.

A: not neoadjuvant.

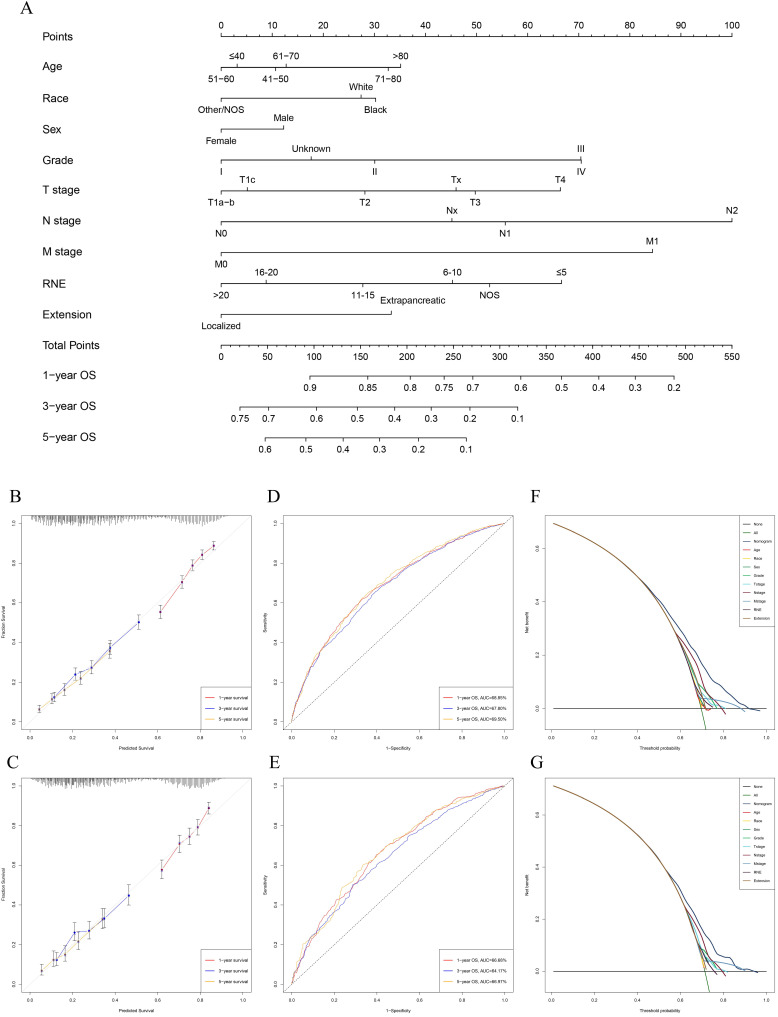

Calibration and Verification of Prognostic Nomograms

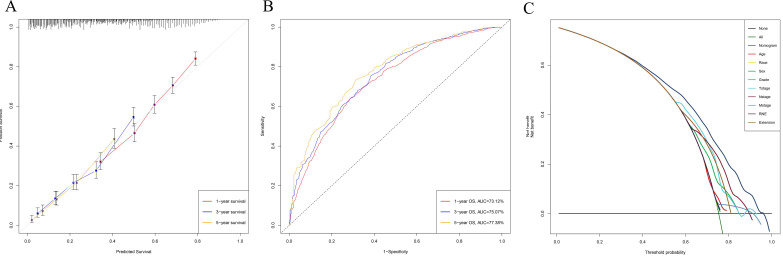

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses were used to calculate the effect of variables on overall survival (OS). The measure of the effect of each variable on OS was presented as the odds ratio (OR) and used to identify independent risk factors. Univariate analysis of variables with significant differences were included in the Cox regression model for multivariate analysis. According to the results based on the multivariate Cox regression analysis, OS is significantly associated with 9 variables, namely, age, race, sex, pathological grade, T stage, N stage, M stage, RNE and extension (Table 2). All of the significant variables were used to create the nomograms for OS. The prognostic nomogram for 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS is shown in Fig. 2A. The risk score of each independent prognostic factor is listed in Table 3. Various methods, including C-index value, time-dependent ROC curves, DCA curves and calibration curves, then were used to identify the discriminating superiority of nomogram. There are no obviously deviations from the reference line in calibration curves for OS in both training group and verification group (Fig. 2B-C), which demonstrating a high degree of reliability. Time-dependent receiver operating characteristics (ROC) at 1, 3, and 5 years are conducted to confirm that the nomogram have a favorable sensitivity and specificity (Fig. 2D-E). The DCA of the nomogram own excellent net benefits and is superior to the any single prognostic factors across the wider range of reasonable threshold probabilities, indicating outstanding value of clinical application (Fig. 2F-G). Moreover, the C-index values are 0.635 (95%CI: 0.624-0.646) in training cohort and 0.618 (95%CI: 0.603-0.633) in verification cohort respectively. Interestingly, the C-index value (0.658, 95%CI: 0.643-0.673), the time-dependent ROC curve, calibration curve, and decision curve also show favorable effects in resectable PDAC patients without chemotherapy (Fig. 3), verifying that this nomogram is also applicable to those who do not receive chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression model analyses for nomogram

| Characteristics | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p-value | OR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p-value | |

| Gender | 0.022 | 0.018 | ||||||

| Female | reference | reference | ||||||

| Male | 1.084 | 1.012 | 1.162 | 0.022 | 1.088 | 1.015 | 1.167 | 0.018 |

| Age (years) | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||

| ≤40 | reference | reference | ||||||

| 41-50 | 0.959 | 0.684 | 1.346 | 0.811 | 1.057 | 0.753 | 1.485 | 0.748 |

| 51-60 | 0.919 | 0.667 | 1.268 | 0.607 | 0.982 | 0.711 | 1.356 | 0.913 |

| 61-70 | 0.980 | 0.712 | 1.348 | 0.899 | 1.070 | 0.777 | 1.473 | 0.680 |

| 71-80 | 1.117 | 0.810 | 1.540 | 0.500 | 1.221 | 0.884 | 1.685 | 0.226 |

| >80 | 1.169 | 0.822 | 1.663 | 0.384 | 1.229 | 0.862 | 1.751 | 0.254 |

| Marital status | 0.235 | |||||||

| Married | reference | NA | ||||||

| Unmarried/NOS | 1.045 | 0.972 | 1.125 | 0.235 | ||||

| Race | 0.037 | 0.044 | ||||||

| White | reference | reference | ||||||

| Black | 0.982 | 0.876 | 1.101 | 0.760 | 1.016 | 0.905 | 1.141 | 0.787 |

| Other/NOS | 0.821 | 0.706 | 0.955 | 0.010 | 0.826 | 0.709 | 0.962 | 0.014 |

| Tumor location | .963 | |||||||

| Head | reference | NA | ||||||

| Body/Tail | 0.989 | 0.894 | 1.093 | 0.824 | ||||

| Other | 1.008 | 0.895 | 1.136 | 0.894 | ||||

| Pathological grade | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| I | reference | reference | ||||||

| II | 1.267 | 1.106 | 1.451 | 0.001 | 1.229 | 1.070 | 1.410 | 0.003 |

| III | 1.704 | 1.484 | 1.957 | <0.001 | 1.614 | 1.402 | 1.857 | <0.001 |

| IV | 1.439 | 0.979 | 2.115 | 0.064 | 1.650 | 1.120 | 2.431 | 0.011 |

| Unknown | 1.233 | 1.051 | 1.446 | 0.010 | 1.118 | 0.947 | 1.319 | 0.187 |

| T stage | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| T1a-b | reference | reference | ||||||

| T1c | 1.427 | 1.017 | 2.003 | 0.039 | 1.051 | 0.744 | 1.484 | 0.779 |

| T2 | 1.814 | 1.309 | 2.512 | <0.001 | 1.228 | 0.879 | 1.716 | 0.227 |

| T3 | 2.176 | 1.564 | 3.028 | <0.001 | 1.423 | 1.014 | 1.997 | 0.041 |

| T4 | 2.540 | 1.799 | 3.587 | <0.001 | 1.598 | 1.116 | 2.287 | 0.010 |

| Tx | 2.214 | 1.484 | 3.301 | <0.001 | 1.385 | 0.920 | 2.087 | 0.119 |

| N stage | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| N0 | reference | reference | ||||||

| N1 | 1.510 | 1.386 | 1.644 | <0.001 | 1.471 | 1.345 | 1.608 | <0.001 |

| N2 | 1.941 | 1.762 | 2.139 | <0.001 | 1.992 | 1.791 | 2.216 | <0.001 |

| Nx | 1.927 | 1.672 | 2.221 | <0.001 | 1.347 | 1.133 | 1.602 | 0.001 |

| M stage | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| M0 | reference | reference | ||||||

| M1 | 2.057 | 1.805 | 2.343 | <0.001 | 1.737 | 1.512 | 1.996 | <0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | 0.014 | 0.109 | ||||||

| Neoradiotherapy | reference | reference | ||||||

| RadiotherapyA | 1.079 | 0.947 | 1.230 | 0.254 | 0.950 | 0.826 | 1.093 | 0.474 |

| No | 1.172 | 1.029 | 1.334 | 0.017 | 1.029 | 0.896 | 1.182 | 0.683 |

| RNE | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| ≤5 | ||||||||

| 6-10 | 0.910 | 0.814 | 1.017 | 0.096 | 0.859 | 0.757 | 0.974 | 0.018 |

| 11-15 | 0.830 | 0.745 | 0.926 | 0.001 | 0.759 | 0.670 | 0.861 | <0.001 |

| 16-20 | 0.785 | 0.699 | 0.881 | <0.001 | 0.668 | 0.585 | 0.763 | <0.001 |

| >20 | 0.782 | 0.702 | 0.871 | <0.001 | 0.629 | 0.553 | 0.715 | <0.001 |

| NOS | 0.984 | 0.720 | 1.345 | 0.920 | 0.910 | 0.664 | 1.247 | 0.557 |

| Extension | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Localized | reference | reference | ||||||

| Extrapancreatic | 1.455 | 1.320 | 1.603 | <0.001 | 1.259 | 1.136 | 1.395 | <0.001 |

RNE: Regional nodes examined; NOS: Not otherwise specified, NA: Unavailable.

A: not neoadjuvant.

Figure 2.

Construction and verification of the nomogram. A: The nomogram predicting OS for resectable PDAC patients with chemotherapy. B: The calibration curves predicting OS at 1-year, 3-year, 5-year in training group. C: The calibration curves predicting OS at 1-year, 3-year, 5-year in verification group. D: The AUC values of time- dependent ROC curves regarding nomogram predicting 1-year, 3-year, 5-year OS in training group. E: The AUC values of time- dependent ROC curves regarding nomogram predicting 1-year, 3-year, 5-year OS in verification group. F: The decision curve analysis displayed the obvious advantages of the nomogram comparing with the other indicators in training group. G: The decision curve analysis displayed the obvious advantages of the nomogram comparing with the other indicators in verification group.

Table 3.

The risk score of each independent prognostic factor

| Characteristics | Points |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| ≤40 | 3 |

| 41-50 | 11 |

| 51-60 | 0 |

| 61-70 | 13 |

| 71-80 | 33 |

| >80 | 35 |

| Race | |

| White | 27 |

| Black | 30 |

| Other/NOS | 0 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 0 |

| Male | 12 |

| Pathological grade | |

| I | 0 |

| II | 30 |

| III | 70 |

| IV | 70 |

| Unknown | 18 |

| T stage | |

| T1a-b | 0 |

| T1c | 5 |

| T2 | 28 |

| T3 | 50 |

| T4 | 66 |

| Tx | 46 |

| N stage | |

| N0 | 0 |

| N1 | 56 |

| N2 | 100 |

| Nx | 45 |

| M stage | |

| M0 | 0 |

| M1 | 84 |

| RNE | |

| ≤5 | 67 |

| 6-10 | 45 |

| 11-15 | 28 |

| 16-20 | 9 |

| >20 | 0 |

| NOS | 53 |

| Extension | |

| Localized | 0 |

| Extrapancreatic | 33 |

Figure 3.

The calibration curve (A), time-dependent ROC curve (B), and DCA curve (C) showed favorable effects in resectable PDAC patients without chemotherapy.

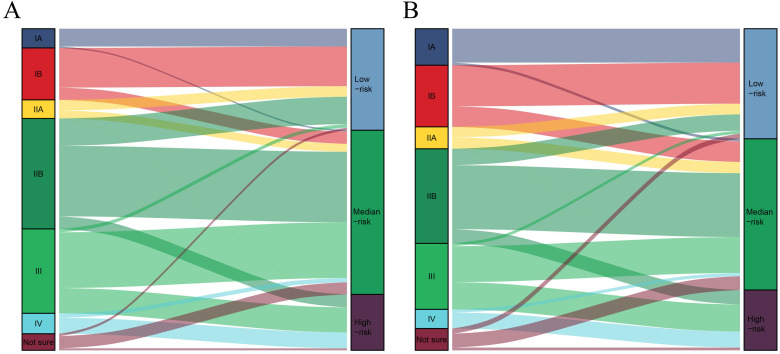

Performance of the Nomograms in Stratifying on the basis of Risk Scores

The total risk score of each patient was calculated by summing the scores related to each variable. X-tile software was utilized to classify patients into high-risk (score >283), median-risk (197<score ≤283), and low-risk (score ≤197) according to the total risk score (Supplementary Figure 1). Sankey diagrams were then delineated to show the correspondence between our risk stratification and the AJCC staging (Fig. 4). Patients in the low-risk group mainly originated from early-stage PDAC patients. However, the risk stratification cannot completely correspond to the AJCC staging system.

Figure 4.

The correspondence between our risk stratification and the AJCC staging. A: The correspondence between our risk stratification and the AJCC staging in PDAC patients with chemotherapy. B: The correspondence between our risk stratification and the AJCC staging in PDAC patients without chemotherapy.

The impact of chemotherapy on patients at each risk level

Can resectable PDAC patients at all risk levels really get survival benefit from chemotherapy? The survival differences between chemotherapy and non-chemotherapy patients were compared in each risk group by log-rank test respectively (Fig. 5). The survival curves indicated that the low-risk resectable PDAC patients cannot receive survival benefit from chemotherapy (p=0.443). Moreover, chemotherapy improved survival for resectable PDAC patients in the median-risk (p<0.001) and high-risk (p<0.001) groups. Therefore, our study successfully screened out low-risk resectable PDAC patients, who can avoid enduring side effects caused by chemotherapy without affecting the survival time.

Figure 5.

The survival differences between chemotherapy and non-chemotherapy in each risk stratification. A: The survival differences between chemotherapy and non-chemotherapy in PDAC patients with low-risk (p=0.443). B: The survival differences between chemotherapy and non-chemotherapy in PDAC patients with median-risk (p<0.001). C: The survival differences between chemotherapy and non-chemotherapy in PDAC patients with high-risk (p<0.001).

Discussion

As described in the guidelines, clinicians usually recommend chemotherapy for patients with PDAC to prolong survival since the unusual aggressiveness. Promising chemotherapy regimens, such as FOLFIRINOX, indeed demonstrated superiority 10. However, multi-drug chemotherapy leads to a highly toxic combination and serious adverse effects. Moreover, a recent study displayed that advances in surgery, including accurate assessment of the resection margins and total mesopancreatic excision (TMpE), contributed to the apparent improvement of survival in resectable PDAC patients, but progress in radiotherapy and chemotherapy was tedious for PDAC 11. Advanced surgical concepts may allow more resectable PDAC patients to avoid multi-drug chemotherapy or even chemotherapy. Moreover, a recent study reported that PDAC patients with stage IA cannot receive better survival from chemotherapy 8. These evidences motivated us to identify low-risk PDAC patients after pancreatectomy who do not need chemotherapy. To the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to look into a scoring system to screen out low-risk PDAC patients after pancreatectomy, who cannot obtain survival benefit from chemotherapy, based on public database. The successful scoring system also confirmed that chemotherapy for all PDAC patients is unreasonable.

Most of the studies usually focus on exploring optimal chemotherapy regimen and enroll more relatively advanced PDAC patients to investigate the effect of chemotherapy on survival. These studies, including more than 50% stage III PDAC patients 12, 13 or even over 70% ones with lymph nodes metastasis 14, 15, confirmed the chemotherapy superiority but ignored the fact that a small number of patients may not need chemotherapy. In addition, the guidelines do not formulate a corresponding chemotherapy regimen based on the pathological characteristics of resectable PDAC. Meanwhile, scarce research is not enough to support the rationality of chemotherapy for early-stage PDAC after resection. Therefore, these concepts involving chemotherapy for all PDAC patients need to be changed. A recent study reported that adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with improved OS in PDAC patients with negative lymph nodes who underwent resection of pancreatic cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy 16, which indicates that some limited PDAC, that may be controlled by preoperative chemotherapy, can be completely cured by surgery without adjuvant chemotherapy. Another study further confirmed that chemotherapy cannot improve the survival of resectable PDAC patients with negative resectable lymph nodes by using a national database 17. However, it is not enough to judge whether chemotherapy is needed only by lymph node status, or even the AJCC staging system for resectable PDAC.

Previous studies reported the updated AJCC staging system owning better clinical value 18, 19. The nomogram displayed that N2 and T3 hold a higher risk score than N1 and extrapancreatic extension respectively, which can, to a certain extent, prove the superiority of the 8th edition of AJCC staging compared to the 7th, at least for resectable PDAC. Nevertheless, the 8th edition AJCC staging system is still not comprehensive enough for identifying low-risk groups. In fact, the predictive effect of the AJCC staging system, detected by C-index (nomogram: 0.637, 95%CI: 0.630-0.645; vs. the AJCC staging system: 0.616, 95%CI: 0.608-0.624), calibration curves, ROC curves and DCA curves, was not as good as the nomogram in this study (Supplementary Figure 2). In fact, the results regarding the survival difference between chemotherapy and non-chemotherapy in each AJCC stage display that only stage IA PDAC cannot obtain survival benefit from chemotherapy (Supplementary Figure 3), which matches the previous study 8. Furthermore, the early-stage PDAC patients defined by the AJCC staging system may be classified as intermediate or high-risk groups, as displayed by the Sankey diagrams. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate other independent prognostic factors into the evaluation system. Moreover, the 8th edition of AJCC staging of PDAC only considered the tumor size regardless of extrapancreatic extension for T3 5. Our study believed that AJCC staging should not completely ignore the extension since it is significantly related to OS. RNE is considered as the priority for the assessment of the quality of surgery 20, 21 and can serve as an independent prognostic factor for resectable PDAC patients. Increasing RNE is able to decrease the risk score for resectable PDAC in the nomogram. In fact, RNE is one of the key factors in determining whether a colorectal cancer patient needs chemotherapy 22. Similarly, RNE as an independent prognostic factor should be included in the chemotherapy decision-making system for PDAC after resection. Aggregately, the comprehensive scoring system can better serve for chemotherapy decisions-making than the AJCC staging system.

Plenty of studies did not provide detailed chemotherapy regimens to explore the effect of chemotherapy on survival 17, 23, 24, which may be influenced by that the guidelines never draft discriminate chemotherapy regimens for resectable PDAC patients with different risk, which weakens the defect in this study that we cannot get detailed chemotherapy regimens from the SEER database. Moreover, the data from the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) demonstrated that T1/T2 PDAC patients have similar survival irrespective of the timing of chemotherapy and surgery and upfront resection is able to increase the possibility of long-term survival 23, which further supports our point that resection could completely cure some early-stage PDAC patients. Hence, despite the lack of detailed chemotherapy regimens and the timing of chemotherapy and surgery, the conclusion that the low-risk PDAC patients cannot obtain survival benefit from chemotherapy after resection is trustworthy. There were, unfortunately, a large number of patients with median- and high-risk in the non-chemotherapy group, who should obtain survival benefit from chemotherapy. Therefore, our risk scoring system can also be used to encourage these patients to actively receive chemotherapy.

The role of radiotherapy and indications for its use in this setting have been debated for some time and are still under investigation. Some studies indicated that radiotherapy can improve marginal negative resection and local control of PDAC 25. However, some scholars believed that the use of radiotherapy in pancreatic cancer has ended due to the poor results of several important radiotherapy trials 26. PDAC, being surrounded by many radiosensitive organs but with extremely treatment-resistant, actually bears high risks and low benefits in the case of receiving radiotherapy, which also cannot be used as an independent prognostic factor in this study.

The risk score does not always increase with age in our nomogram. Previous research indicated that young cancer patients suffered a higher risk of lymph node metastasis 27-29, which may be the reason why the risk score of PDAC patients under 50 is higher than that of ones aged 51-60. Limitations of this study include: (1) the use of retrospective data; (2) detailed treatment information for included patients were not recorded in the SEER cohort, and we cannot investigate specific options, including R0 or not, preoperative or postoperative chemotherapy in the survival of PDAC patients; (3) other important factors, such as proximity/involvement of major vascular structures, CA 19-9, and patient comorbidities should also be minded.

Conclusion

Our study confirmed that the recommendation suggesting all patients with PDAC after pancreatectomy receive chemotherapy is unreasonable. The novel risk-scoring system based on survival nomogram could serve as a chemotherapy decision tool and is capable of identifying low-risk patients with resected PDAC, who can avoid enduring side effects caused by chemotherapy without affecting the survival time.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgments

The first author, Yuqiang Li, gratefully acknowledges financial support from China Scholarship Council.

Funding

This study was supported by the Nature Scientific Foundation of China (Grant No. 81702956).

Ethics approval

Approval from the ethical board for this study was not required because of the public nature of all the data.

Informed consent

Patients' informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study design.

Data availability statement

These data were derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database (https://seer.cancer.gov/) and identified using the SEER*Stat software (Version 8.3.5) (https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/).

Author Contributions

Yuqiang Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration;

Mengxiang Tian: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing;

Yuan Zhou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision;

Fengbo Tan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition;

Wenxue Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization;

Lilan Zhao: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing;

Daniel Perez: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization;

Xiangping Song: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization;

Dan Wang: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization;

Christine Nitschke: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization;

Qian Pei: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization;

Cenap Güngör: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision.

References

- 1.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch AM, Gingras MC. et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:607–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hidalgo M, Cascinu S, Kleeff J, Labianca R, Lohr JM, Neoptolemos J. et al. Addressing the challenges of pancreatic cancer: future directions for improving outcomes. Pancreatology: official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology. 2015;15:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gungor C, Hofmann BT, Wolters-Eisfeld G, Bockhorn M. Pancreatic cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:849–58. doi: 10.1111/bph.12401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Chiorean EG, Czito B, Scaife C, Narang AK. et al. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 1.2019. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN. 2019;17:202–10. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seufferlein T, Bachet JB, Van Cutsem E, Rougier P. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: ESMO-ESDO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii33–40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boeck S, Ankerst DP, Heinemann V. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with resected pancreatic cancer: systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. Oncology. 2007;72:314–21. doi: 10.1159/000113054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Xu G, Chen M, Wei Q, Zhou T, Chen Z. et al. Stage IA Patients With Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cannot Benefit From Chemotherapy: A Propensity Score Matching Study. Frontiers in oncology. 2020;10:1018. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agha R, Abdall-Razak A, Crossley E, Dowlut N, Iosifidis C, Mathew G. STROCSS 2019 Guideline: Strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. International journal of surgery (London, England) 2019;72:156–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y. et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Liu W, Zhao L, Xu Y, Yan T, Yang Q. et al. The Main Bottleneck for Non-Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma in Past Decades: A Population-Based Analysis. Medical science monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2020;26:e921515. doi: 10.12659/MSM.921515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CM. et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1011–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Cunningham D, Goldstein D. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2010;304:1073–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, Hartmann JT, Gellert K, Ridwelski K. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. Jama. 2013;310:1473–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.279201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, Safran H, Hoffman JP, Konski A. et al. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2008;299:1019–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Roessel S, van Veldhuisen E, Klompmaker S, Janssen QP, Abu Hilal M, Alseidi A, Evaluation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients With Resected Pancreatic Cancer After Neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX Treatment. JAMA oncology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Skau Rasmussen L, Vittrup B, Ladekarl M, Pfeiffer P, Karen Yilmaz M, Østergaard Poulsen L. et al. The effect of postoperative gemcitabine on overall survival in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: A nationwide population-based Danish register study. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 2019;58:864–71. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1581374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamarajah SK, Burns WR, Frankel TL, Cho CS, Nathan H. Validation of the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) 8th Edition Staging System for Patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Analysis. Annals of surgical oncology. 2017;24:2023–30. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5810-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JW, Lee JH, Park Y, Lee W, Kwon J, Song KB. et al. Prognostic Predictability of American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th Staging System for Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Limited Improvement Compared with the 7th Staging System. Cancer research and treatment: official journal of Korean Cancer Association. 2020;52:886–95. doi: 10.4143/crt.2020.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Zhao L, Gungor C, Tan F, Zhou Z, Li C. et al. The main contributor to the upswing of survival in locally advanced colorectal cancer: an analysis of the SEER database. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology. 2019;12:1756284819862154. doi: 10.1177/1756284819862154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai Y, Cheng G, Lu X, Ju H, Zhu X. The re-evaluation of optimal lymph node yield in stage II right-sided colon cancer: is a minimum of 12 lymph nodes adequate? International journal of colorectal disease. 2020;35:623–31. doi: 10.1007/s00384-019-03483-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), Colon Cancer, Version 2.2020.

- 23.Vidri RJ, Olsen WT, Clark DE, Fitzgerald TL. Upfront resection versus neoadjuvant therapy for T1/T2 pancreatic cancer. HPB: the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H. et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;350:1200–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D, Liu C, Zhou Y, Yan T, Li C, Yang Q. et al. Effect of neoadjuvant radiotherapy on survival of non-metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a SEER database analysis. Radiation oncology (London, England) 2020;15:107. doi: 10.1186/s13014-020-01561-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouchart C, Navez J, Closset J, Hendlisz A, Van Gestel D, Moretti L. et al. Novel strategies using modern radiotherapy to improve pancreatic cancer outcomes: toward a new standard? Therapeutic advances in medical oncology. 2020;12:1758835920936093. doi: 10.1177/1758835920936093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li M, Zhang J, Dan Y, Yao Y, Dai W, Cai G. et al. A clinical-radiomics nomogram for the preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. Journal of translational medicine. 2020;18:46. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02215-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Liu W, Zhou Z, Ge H, Zhao L, Liu H. et al. Development and validation of prognostic nomograms for early-onset locally advanced colon cancer. Aging. 2020;13:477–92. doi: 10.18632/aging.202157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ordonez JE, Hester CA, Zhu H, Augustine M, Porembka MR, Wang SC. et al. Clinicopathologic Features and Outcomes of Early-Onset Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma in the United States. Annals of surgical oncology. 2020;27:1997–2006. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-08096-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.

Data Availability Statement

These data were derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database (https://seer.cancer.gov/) and identified using the SEER*Stat software (Version 8.3.5) (https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/).