Abstract

Objective:

To measure anti-glycan antibodies (AGA) in cervical cancer (CC) patient sera and assess their effect on therapeutic outcome.

Patients and Methods:

Serum AGA was measured in 276 stage II and 292 stage III Peruvian CC patients using a high content and throughput Luminex multiplex glycan array (LMGA) containing 177 glycans. Association with disease-specific survival (DSS) and progression free survival (PFS) were analyzed using Cox regression.

Results:

AGAs were detected against 50 (28.3%) of the 177 glycans assayed. Of the 568 patients, 84.5% received external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) plus brachytherapy (BT), while 15.5% only received EBRT. For stage-matched patients (Stage III), receiving EBRT alone was significantly associated with worse survival (HR 6.4, p < 0.001). Stage III patients have significantly worse survival than Stage II patients after matching for treatment (HR = 2.8 in EBRT+BT treatment group). Furthermore, better PFS and DSS were observed in patients positive for AGA against multiple glycans belonging to the blood group H, Lewis, Ganglio, Isoglobo, lacto and sialylated tetrarose antigens (best HR = 0.49, best p = 0.0008).

Conclusions:

Better PFS and DSS are observed in cervical cancer patients that are positive for specific antiglycan antibodies and received brachytherapy.

Keywords: glycans, anti-glycan antibodies, biomarkers, cervical cancer, therapeutic outcome

Background

Cervical cancer is the third most common female cancer and second most frequent cause of cancer related death in women world-wide [1]. Chronic persistent infections with certain human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes have been identified as the causative agents for this disease [2, 3]. Screening programs and effective methods of treatment have been the primary reasons for lower incidences and better outcomes in developed nations [4]; however, in developing countries, a higher proportion of women are diagnosed with cervical cancer at advanced stages. Approximately 51% of women are diagnosed with stage IIB or later, which requires treatment with pelvic external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) combined with brachytherapy (BT), and chemotherapy when available [5]. Those with distant metastasis are treated with EBRT alone with or without chemotherapy [6]. Many patients with stage IVB disease are treated with EBRT for palliation and the EBRT nearly doubles progression-free survival (PFS) [7, 8]. Unfortunately, in developed countries less than half of patients have access to surgery or radiation. Even less have access to chemotherapy as rates of chemotherapy have been reported as low as 3% [9, 10]. Given the limited access to care, it is imperative that the treatment for these patients is optimized to be as effective as possible. Currently there are no biomarkers available that can predict cervical cancer treatment outcomes or which treatment may be most effective. Therefore, biomarkers that could guide therapeutic selection are highly desired.

Anti-glycan antibodies (AGA) which are present in normal human serum [11–13] offer a new and unique target which may aide in this task. Elevated AGAs have been shown to be present in the serum of a number of other cancers including ovarian [14–16], colorectal [17], and breast [18]. Additional studies on AGAs have shown they can also predict survival in melanoma [19], colorectal [17] and prostate [20] cancer patients. AGAs are functionally relevant to cancer and may represent actionable targets in cancer. First, AGAs can neutralize glycans and thereby reduce the availability of free glycans that have important functions in multiple malignant activities such as proliferation and metastasis [13, 18, 21–24]. Furthermore, glycans may be actively exported from tumor cells to suppress immune responses, alter the tumor microenvironment, increase angiogenic signaling and promote tumor growth [25]. Therefore, neutralizing specific glycans by AGAs may be beneficial to cancer patients. Second, AGA levels may reflect the immune competency to fight cancer [26]. This may be even more the case in certain treatment situations such as radiation therapy, which is known to activate antitumor immune response by altering the immunosuppressive microenvironment [27].

The present study was undertaken to determine if serum levels of AGAs to a diverse set of glycan structures, such as blood group antigens, pathogen-related oligosaccharides, lactosamines, sulfated carbohydrates, sialylated carbohydrates, fucosylated carbohydrates and known tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens could be associated with patient’s survival outcome in cervical cancer.

Methods

Study design and patients

This study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review boards of the Augusta University and the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas. All the subjects included in this study were recruited from the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima, Peru, between 2004 and 2007. Informed consent was obtained from every subject or a legally authorized representative. Women 18 years or older presenting with a histologic diagnosis of cervical neoplasia, or clinical evidence of invasive cervical cancer were asked to participate in the study. Serum was obtained from 568 women with stage II and III squamous cell cervical carcinoma prior to initiation of treatment. Because the study was conducted from 2004–2007 it was not recorded if patients had stage IIIC disease. Most patients underwent treatment with pelvic external beam radiation (EBRT) plus brachytherapy (EBRT+BT), while a small subset of patients received EBRT alone primarily because they lived far away from the clinics and could not afford brachytherapy. The stage and grade of the tumors were determined according to the criteria established by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Disease-specific (DSS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were used as the clinical endpoints.

Construction of glycan array and measurement of anti-glycan IgG antibodies

Glycans containing a free amino group (Supplementary Table 1) were chemically coupled to carboxylated beads with a unique fluorescent spectral address (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX, USA), to create a Luminex multiplex glycan array (LMGA) [28]. Sera were screened for IgG-type antibody to 177 glycans by solid-phase micro-bead fluorescence immuno-assay [28]. Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) was collected on the FlexMAP 3D Luminex Corp., Austin, TX, USA) and used for all statistical analysis. Anti-glycan IgG positivity (AGA+) was defined as observed net MFI greater than the mean plus 3 times of standard deviation of the background beads.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the R language and environment for statistical computing (R version 3.44; R Foundation for Statistical Computing; www.rproject.org). All statistical tests were two-tailed and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Cox regression analysis and Log-Rank test were used to evaluate the impact of serum anti-glycan IgG levels on DSS (diagnosis to date of death) and PFS (date of first treatment to the date of failure to achieve remission). Patients who were alive with no evidence of disease were censored at the date of last follow-up visit. For DSS, patients who died from causes other than cervical cancer were also censored. Kaplan-Meier analysis, and log rank test were used to compare differences in DSS and PFS. Initially the anti-glycan IgG levels were incorporated into the Cox regression model, then age, stage and treatment type were included as co-variates. Based on stage and treatment the data was divided into three groups to perform Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression to determine the HR within each stage and treatment group. Relationship between the type of radiation therapy and anti-glycan IgG levels were tested as interaction in the Cox regression analysis. The HR and 95% confidence interval (CI) for all glycans are presented as forest plots.

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics of study population

Clinical information obtained included age, stage, treatment type and sites for recurrence for the study subjects are presented in Table 1A. The median age of diagnosis was 47 years. 276 (48.6%) had stage II, and 292 (51.4%) had stage III disease. The most common treatment was EBRT plus BT (480, 84.5%). Of the entire cohort, 88 (15.5%) women underwent EBRT alone and this cohort contain only stage III patients and did not differ from the other stage III patients who were treated with EBRT+BT for clinical and demographic factors. Median DSS and PFS for the stage II subjects (136.2 and 131.9 months) was higher compared to stage III subjects (37.9 and 17.5 Table 1A)

Table 1A:

clinical and demographic variables for subjects with squamous cell carcinoma of cervix (n=568) participating in Cervicusco study.

| Variable | IIB (n=276) | IIIB (n=292) | pvalue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis (Years) | 48.4 | 51.1 | 0.00127 |

| Median age (range, years) | 47 (26–76) | 51 (27–82) | 0.0005979* |

| Median survival Time (months) | |||

| DSS | 136.2 | 37.9 | |

| PFS | 131.9 | 17.5 | |

| Treatment type | |||

| EBRT (n) | 88 (15.5%) | ||

| EBRT+BT (n) | 276 (48.6%) | 204 (36%) | |

| Recurrence Sites | |||

| No information | 214 (37.7%) | 237 (41.7%) | |

| Other Organs | 26 (4.6%) | 11 (1.9%) | |

| Pelvis | 13 (2.3%) | 21 (3.7%) | |

| Retroperitoneal Ganglionar | 11 (1.9%) | 15 (2.6%) | |

| Vagina/Cervix | 12 (2.2%) | 8 (1.4%) |

Kruskall-Wallis test, DSS: Disease specific survival, PFS: Progression free survival, EBRT: external beam radiotherapy, EBRT+BT: EBRT plus brachytherapy.

The effect of age, stage and treatment on survival was assessed using univariate Cox proportional hazard. Increased stage was associated with DSS (HR = 2.8 95% CI: 2.1–3.65; p=4×10−13) and PFS (HR = 3.2, 95% CI: 2.5–4.2, p=4×10−19). Age was not significantly associated with DSS (HR=0.99, 95% CI: 0.97–0.99, p=0.03) and PFS (HR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98–1.0; p=0.07). Treatment with EBRT+BT was associated with better outcome (HR=0.23, 95% CI: 0.16–0.32; p=3.2×10−19 Table 1B)

Table 1B:

Kaplan-Meier analysis for effect of Age, stage and treatment in Cervicusco patients used in the current study.

| Disease specific Survival | Progression free Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | pvalue | HR | pvalue |

| Stage | ||||

| II(n=276) | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| III (n=292) | 2.8 (2.10–3.65) | 4×10−13 | 3.2 (2.5–4.2) | 4.5×10−19 |

| Age | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.03 | 0.99 (0.98–1.0) | 0.07 |

| Treatment Type | ||||

| EBRT (n=88) | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| EBRTRT+BT (n=480) | 0.23 (0.16–0.31) | 3.2×10−19 | 0.15 (0.11–0.19) | 1.7×10−42 |

Log rank p are presented, EBRT: External beam radiotherapy, EBRT+BT: EBRT plus Brachytherapy

Stage and treatment were used to assign all patients into three groups. Group 1 are stage II patients treated with EBRT+BT (n=276). Group 2 are stage III patients treated with EBRT+BT (n=204). Group 3 are stage III patients treated with EBRT alone (n=88). Group 2 (HR = 2.2 (95% CI: 1.6–2.9), p=3.1×10−7) and Group 3 patients (HR = 6.4(4.4–9.2), p=3.0×10−23) had worse DSS compared to Group 1 (Figure 1A). Group 2 (HR = 2.2, 95% CI: p=2.8×10−8) and group 3 (HR = 10.1, 95%CI: p=3×10−45) also had worse PFS compared to Group 1 (Figure 1B). Among stage III patients, Group 2 patients (EBRT+BT) had better DSS compared to Group 3 patients (EBRT) (HR=0.35, p=5.9×10−9). Among patients treated with EBRT+BT, Stage III patients (Group 2) had worse DSS (HR=2.2, p=2.3×10−7) and PFS (HR =3.2, p=4.5×10−19) than stage II (Group 1, Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Kaplan-Meier plots and Cox regression analysis. The three groups of subjects were defined using stage and treatment types. Group 1: Stage II patients treated with EBRT+BT (Solid line). Group 2: Stage III patients treated with EBRT+BT (dashed line). Group 3: Stage III patients treated with EBRT alone (dotted line). A) Disease specific survival (DSS). B) Progression free survival (PFS).

Profiling of AGA on LMGA

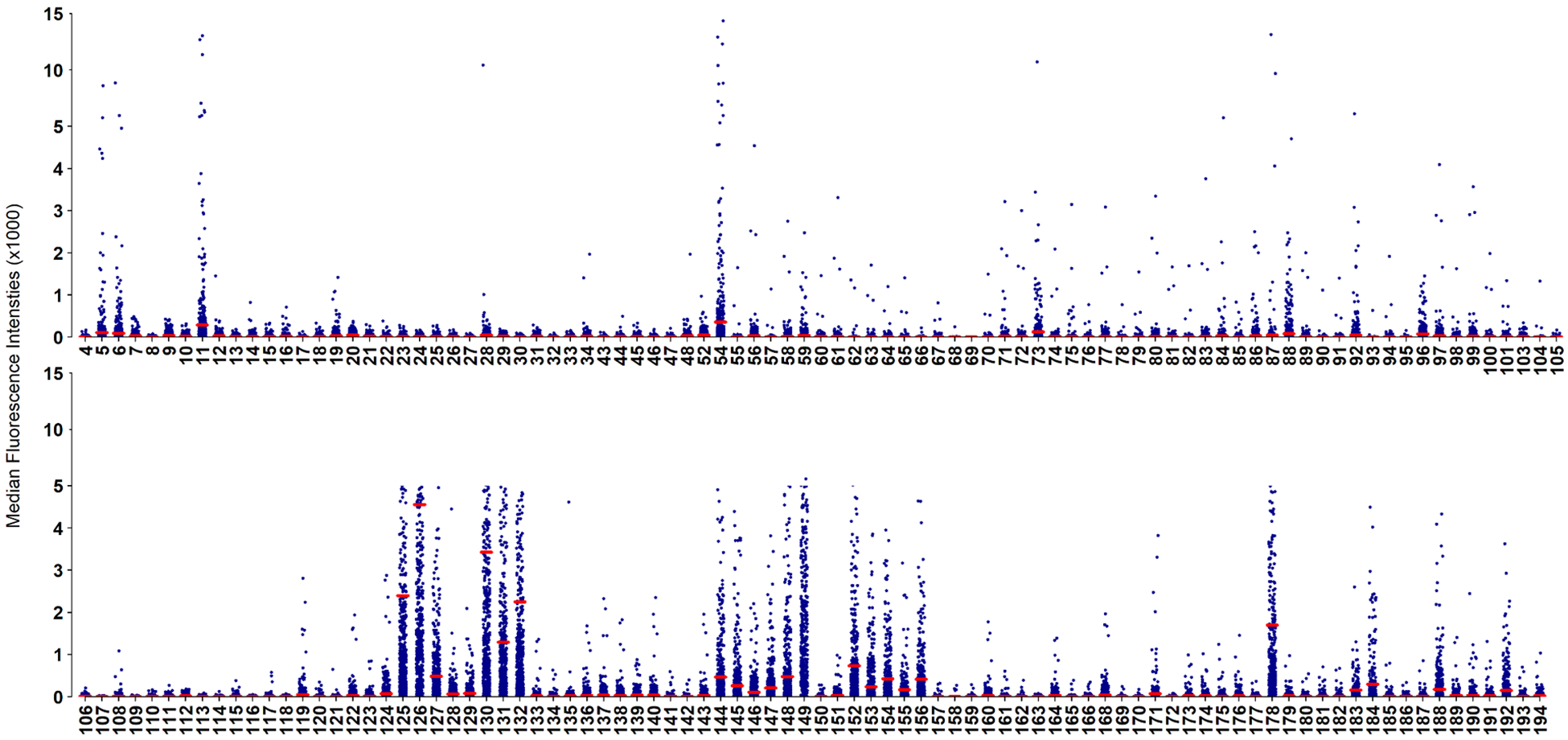

AGAs against 177 glycans were measured in sera of all patients. AGA levels varied for different glycans and dot blots for net MFI for all glycans are presented in Figure 2. AGAs against 50 (28.3%) glycans were positive in at least 2.0% of the subjects (Supplementary Table 2). These 50 AGAs belonged to 12 different groups including blood group antigens (Gly#54, 122–125, 127, 130–132), Lewis antigens (#128,129, 133–139), Galili and xeno antigens (#147–149,151,152), isoglobo and globo series (#153–156, 178), ganglio-series (#164, 168,171) and Forsman antigens (#183,184). Anti-glycan IgG antibodies to sialylated forms of glycans (#9 and 160), blood group (#188) and isoglobo (#192) analogues were also observed (Figure 2). These 50 AGAs were further analyzed for their association with patient survival.

Figure 2:

Dot plots of anti-glycan IgG antibodies against 177 glycans in serum of 568 cervical cancer patients. Glycan IDs are shown at the bottom of the plot. Each dot represents one subject. Red bar represents the mean for each glycan.

Interaction Effect of AGA and Treatment Modality on Survival

Since survival of patients is greatly influenced by the treatment modality, we first conducted Kaplan-Meier survival and Cox regression analysis to examine the interaction effect of treatment modality (EBRT alone versus EBRT+BT) and AGA status on survival outcome. In all survival analyses, patients were divided into AGA+ and AGA− subsets based on each glycan.

Analyses were conducted using Stage III patients which include patients treated with EBRT alone and EBRT+BT as well as all patients that include stage II patients (all treated with EBRT+BT) and stage III patients. Results for both analyses were similar (Supplementary Table 3). The interaction was significant for 19 glycans in nine different glycan categories and representative survival curves for stage 3 patients (Group 2) and nine glycans are shown in Figure 3. Because the glycan epitopes are probably the same or very similar among glycans in the same structure group, we corrected p values for multiple testing using Bonferoni correction for the 12 groups of glycans tested. Five of the seven Lewis antigen variants are associated with survival when considering interaction between AGA and treatment modality (best p value = 0.0003, Pc = 0.003, HR = 0.38). Three of the five IsoGlobo antigens are also significant (best p = 0.0049, Pc = 0.059, HR =0.47). Association with both Ganglio AGA is also significant (best p = 0.0007, Pc = 0.008, HR = 0.34). Blood group H AGA also showed significant association (p = 0.0027, Pc 0.033, HR = 0.45).

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier plots for progression free survival and analyses of interaction between treatment and AGA. Subjects were assigned to the AGA− (blue lines) or AGA+ (red lines) in each of the two treatment groups: EBRT (dashed lines), EBRT+BT (solid lines). Nine representative AGA in Stage 3 patients (Group 2) are presented. P-values for HR presented are computed from Log-Rank Test.

Marginal Effect of AGA on Survival in EBRT-treated Subset

Since the effect of AGA on survival may be treatment-dependent, it is necessary to further dissect the effect of AGA on survival in different treatment groups. In the small group of 88 stage III patients treated with EBRT alone (Group 3), no significant DSS difference was observed with any AGA (Supplementary Table 4). However, AGAs against Lewis, Ganglio and Isoglobo antigens are marginally associated with worse PFS (HR = 1.6–1.7, p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 4).

EBRT+BT-treated Patients with AGA have better survival

In contrast to the results for EBRT-treated patients, multiple analyses indicate that patients treated with EBRT+BT with AGA positivity have better survival than patients negative for AGA. In these analyses, we focused on 20 glycans from six glycan groups that showed significant results in the interactive analyses (Table 2) and p values were corrected by 6 multiple tests. In multivariate analyses of stage 2 and stage patients treated by EBRT+BT and using AGA as dependable variable and stage as co-variate in the Cox models, AGA for 13 glycans in six groups is significantly associated with better PFS (Table 2). Separate analyses for stage 2 and stage 3 patients indicated that the influence of AGA on survival is stronger in stage 3 patients than stage 2 patients. Better PFS was observed in patients with AGA for blood group H in the combined stage 2 and 3 group (best HR = 0.66, p = 0.009, Pc = 0.005) as well as in the stage 3 patients (HR = 0.59, p = 0.0067, Pc = 0.04). Similarly, better PFS was also observed in patients with AGA for Lewis antigens, in the combined stage 2 and 3 group (best HR = 0.72, p = 0.0078, Pc = 0.047) as well as in the stage 3 patients (best HR = 0.49, p = 0.0008, Pc = 0.005). Selective Kaplan-Meir survival curves are shown in Figure 4. Similar analyses were conducted with DSS and the results are largely consistent with PFS. The results are presented in (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 2:

Association between AGA and progression free survival in EBRT+BT-treated patients

| AGA+Stage (Stage 2+3, BT) | Stage 2, BT | Stage 3, BT | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Gly # | HR (95% CI) | P-val | Pc | HR (95% CI) | P-val | Pc | HR (95% CI) | P-val | Pc |

| Blood Group H | 122 | 0.66(0.52 – 0.84) | 0.0009 | 0.005 | 0.7(0.45 – 1.09) | 0.117 | 0.59(0.4 – 0.86) | 0.0067 | 0.040 | |

| 123 | 0.73(0.56 – 0.96) | 0.0218 | 0.8(0.5 – 1.29) | 0.357 | 0.62(0.4 – 0.95) | 0.0269 | ||||

| 124 | 0.69(0.55 – 0.88) | 0.0024 | 0.014 | 0.59(0.38 – 0.9) | 0.016 | 0.093 | 0.59(0.4 – 0.86) | 0.0057 | 0.034 | |

| Ganglio-series | 164 | 0.81(0.63 – 1.04) | 0.0989 | 0.86(0.55 – 1.33) | 0.492 | 0.59(0.39 – 0.89) | 0.0128 | |||

| 168 | 0.84(0.66 – 1.07) | 0.1591 | 0.78(0.5 – 1.2) | 0.257 | 0.72(0.5 – 1.06) | 0.0970 | ||||

| Isoglobo-series | 153 | 0.71(0.55 – 0.91) | 0.0067 | 0.040 | 0.71(0.45 – 1.12) | 0.138 | 0.61(0.41 – 0.89) | 0.0113 | ||

| 154 | 0.74(0.56 – 0.96) | 0.0228 | 0.59(0.37 – 0.92) | 0.021 | 0.126 | 0.66(0.44 – 1) | 0.0524 | |||

| 155 | 0.79(0.62 – 1) | 0.0513 | 0.72(0.47 – 1.11) | 0.141 | 0.7(0.48 – 1.02) | 0.0669 | ||||

| 156 | 0.9(0.71 – 1.14) | 0.3835 | 0.79(0.52 – 1.22) | 0.291 | 0.8(0.55 – 1.17) | 0.2546 | ||||

| 192 | 1.09(0.86 – 1.39) | 0.4630 | 1.01(0.66 – 1.56) | 0.948 | 1(0.68 – 1.46) | 0.9936 | ||||

| Lewis antigens | 128 | 0.72(0.57 – 0.92) | 0.0078 | 0.047 | 0.72(0.47 – 1.1) | 0.126 | 0.67(0.46 – 0.98) | 0.0368 | ||

| 129 | 0.75(0.59 – 0.95) | 0.0173 | 0.65(0.42 – 0.99) | 0.045 | 0.269 | 0.74(0.51 – 1.08) | 0.1178 | |||

| 133 | 0.78(0.6 – 1.01) | 0.0592 | 0.78(0.48 – 1.26) | 0.304 | 0.67(0.44 – 1.01) | 0.0574 | ||||

| 136 | 0.72(0.56 – 0.92) | 0.0095 | 0.057 | 0.82(0.52 – 1.27) | 0.373 | 0.49(0.32 – 0.74) | 0.0008 | 0.005 | ||

| 137 | 0.78(0.61 – 1) | 0.0522 | 0.83(0.54 – 1.28) | 0.402 | 0.61(0.41 – 0.91) | 0.0162 | ||||

| 138 | 0.74(0.58 – 0.94) | 0.0154 | 0.71(0.46 – 1.11) | 0.138 | 0.64(0.43 – 0.95) | 0.0254 | ||||

| 139 | 0.79(0.62 – 1) | 0.0471 | 0.72(0.47 – 1.1) | 0.126 | 0.66(0.45 – 0.96) | 0.0297 | ||||

| Lacto-series | 140 | 0.75(0.59 – 0.96) | 0.0246 | 0.61(0.39 – 0.96) | 0.033 | 0.200 | 0.67(0.45 – 1) | 0.0473 | ||

| 143 | 0.74(0.57 – 0.95) | 0.0185 | 0.84(0.54 – 1.31) | 0.438 | 0.56(0.37 – 0.84) | 0.0056 | 0.034 | |||

| Sialylated Tetraose | 160 | 0.76(0.59 – 0.97) | 0.0277 | 0.91(0.59 – 1.41) | 0.666 | 0.54(0.35 – 0.81) | 0.0030 | 0.018 | ||

P-val: P- value, Pc: 137,corrected p-values,

Figure 4:

Kaplan-Meier curves for progression free survival in Group 2 subjects, stage 3 patients who received EBRT+BT therapy.

Discussion

We report the first AGA profiling study conducted in cervical cancer using a large panel of 177 different carbohydrate structures in a large cohort of 568 cervical cancer patients. We demonstrated the presence of 50 AGAs in cervical cancer patients. Multivariate analyses adjusted for stage as well as analyses using only stage 3 patients treated the same way (EBRT+BT) showed that 13 AGAs in 6 glycan classes were significantly associated with better survival with similar results for PFS and DSS. The most notable glycan classes include blood group H, Lewis, Isoglobo and lacto glycans, for which more than one glycans showed significant association with cervical cancer patient survival. Many of these glycans and/or their analogues identified in this study are also altered in other cancers including breast [18], colorectal [17] and ovarian [15, 29] cancers. Measurement of AGAs to sialylated Tn, TF and its sulfated analogues [14, 30] and gangliosides were able to compete with CA125 for detection of ovarian cancer [14], suggesting that AGAs can be surrogate markers for prognostic purposes. Studies using both glass glycan arrays and ELISA have shown that antibodies to GalNAcα1–3Gal were significantly correlated with 5-year survival (48% for AGA− vs 85% for AGA+, p = 0.017) in cervical cancer patients [22]. Overexpression of other glycan binding proteins (GBPs), such as hyaluronic acid binding protein, was associated with poor DSS in cervical cancer patients [31].

Overall, this study provided strong evidence that cervical cancer patients positive for specific AGAs have better survival when they are treated with EBRT+BT. However, there is also convincing evidence that AGA+ patients do not have better survival, and probably have worse survival, when treated with ERBT alone. Whether the benefit of AGA positivity for survival depends on the treatment modality will require further studies because the cohort treated with ERBT alone in this study with 88 patients is relatively small and it is not a controlled clinical trial. Although there is no known clinical or demographic factor that differs between the EBRT+BT and EBRT alone groups, it remains remotely possible that other unknown factors may explain the differential effects of AGA on survival between the two treatment modalities. Irrespective of the differential impact of AGA on outcomes of different therapies, this study provided strong confirmatory evidence that EBRT alone is a much worse treatment modality than EBRT+BT; and therefore, brachytherapy should be provided to patients with cervical cancer in all possible cases.

There are at least two functional implications of AGAs, both of which represent actionable targets in cancer. First, tumor cells may export glycans to suppress immune responses, alter the tumor microenvironment, increase angiogenic signaling and promote tumor growth [25]. Free glycans that have important functions in malignant activities such as proliferation and metastasis may be neutralized by AGA [13, 18, 21–24]. The beneficial function of AGAs to cancer patients as observed in this study may be largely explained by their glycan-neutralization function. Second, individuals with high AGAs may reflect a higher level of immune competency so that their immune system may fight cancer more efficiently as observed in several studies [26]. This may be even more the case in certain treatment situations such as EBRT+BT. Radiation therapy is known to activate antitumor immune response by altering the immunosuppressive microenvironment [27]. However, the immune-stimulating effect of radiation therapy certainly depends the dose and delivery modality and different radiation treatment modality can result in immune suppression or activation [26]. Our observations on the differential effects of EBRT versus EBRT+BT on AGA+ patients may be due to their differential impact on ativating antitumor immune response. Given the ever increasing importance of immunotherapy in various cancers, it will be important to continue to examine whether and how antiglycan antibodies may influence therapeutic outcomes in patients with different clinical characteristics and treatment modalities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thanks all the staff from Cervicusco clinic, Peru for their support and help in recruiting patients and collection of samples and clinical data.

Support:

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH)/ National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants 1 R21 CA199868 (JXS and SP), U01CA221242 (JXS and SP), P41GM103694 (RDC) and NIH fellowships F30DK12146101A1 (PMHT), K12HD085817 (JJW). JXS was supported by the Georgia Research Alliance Academy. The Funding agencies has no involvement in conception, design, collection and interpretation, publishing of the data.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- [1].Organization WH. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.wrapper.MGHEMORTCAUSE10?lang=en. 2016.

- [2].Alizon S, Murall CL, Bravo IG. Why Human Papillomavirus Acute Infections Matter. Viruses. 2017;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Burd EM. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Catarino R, Petignat P, Dongui G, Vassilakos P. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries at a crossroad: Emerging technologies and policy choices. World journal of clinical oncology. 2015;6:281–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2016. In: Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA editor. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2016. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, Bradley K, Campos SM, Cho KR, et al. Cervical Cancer, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2019;17:64–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lin MY, Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan S, Bernshaw D, Khaw P, Narayan K. Carcinoma of the cervix in elderly patients treated with radiotherapy: patterns of care and treatment outcomes. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27:e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chuang LT, Feldman S, Nakisige C, Temin S, Berek JS. Management and Care of Women With Invasive Cervical Cancer: ASCO Resource-Stratified Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3354–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zamorano AS, Barnoya J, Gharzouzi E, Chrisman Robbins C, Orozco E, Polo Guerra S, et al. Treatment Compliance as a Major Barrier to Optimal Cervical Cancer Treatment in Guatemala. Journal of global oncology. 2019;5:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].LaVigne AW, Triedman SA, Randall TC, Trimble EL, Viswanathan AN. Cervical cancer in low and middle income countries: Addressing barriers to radiotherapy delivery. Gynecologic oncology reports. 2017;22:16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bovin N, Obukhova P, Shilova N, Rapoport E, Popova I, Navakouski M, et al. Repertoire of human natural anti-glycan immunoglobulins. Do we have auto-antibodies? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:1373–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bovin NV. Natural antibodies to glycans. Biochemistry Biokhimiia. 2013;78:786–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shilova N, Huflejt ME, Vuskovic M, Obukhova P, Navakouski M, Khasbiullina N, et al. Natural Antibodies Against Sialoglycans. Topics in current chemistry. 2015;366:169–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pochechueva T, Chinarev A, Schoetzau A, Fedier A, Bovin NV, Hacker NF, et al. Blood Plasma-Derived Anti-Glycan Antibodies to Sialylated and Sulfated Glycans Identify Ovarian Cancer Patients. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pochechueva T, Alam S, Schotzau A, Chinarev A, Bovin NV, Hacker NF, et al. Naturally occurring anti-glycan antibodies binding to Globo H-expressing cells identify ovarian cancer patients. J Ovarian Res. 2017;10:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gates MA, Wolpin BM, Cramer DW, Hankinson SE, Tworoger SS. ABO blood group and incidence of epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:482–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tikhonov A, Butvilovskaya V, Chernichenko M, Savvateeva E, Feyzkhanova G, Lysov Y, et al. 25Diagnostic value of anti-glycan antibodies in patients with colorectal cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2017;28:mdx508.022–mdx508.022. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang CC, Huang YL, Ren CT, Lin CW, Hung JT, Yu JC, et al. Glycan microarray of Globo H and related structures for quantitative analysis of breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:11661–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Slovin SF, Keding SJ, Ragupathi G. Carbohydrate vaccines as immunotherapy for cancer. Immunology and cell biology. 2005;83:418–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Campbell CT, Gulley JL, Oyelaran O, Hodge JW, Schlom J, Gildersleeve JC. Serum antibodies to blood group A predict survival on PROSTVAC-VF. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:1290–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gates MA, Xu M, Chen WY, Kraft P, Hankinson SE, Wolpin BM. ABO blood group and breast cancer incidence and survival. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Li Q, Anver MR, Li Z, Butcher DO, Gildersleeve JC. GalNAcalpha1–3Gal, a new prognostic marker for cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Torrado J, Plummer M, Vivas J, Garay J, Lopez G, Peraza S, et al. Lewis Antigen Alterations in a Population at High Risk of Stomach Cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2000;9:671–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wu CS, Yen CJ, Chou RH, Li ST, Huang WC, Ren CT, et al. Cancer-associated carbohydrate antigens as potential biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kirsch SSJ, Mormann M, Bindila L, Peter-Katalinic J. Ceramide Profiles of Human Serum Gangliosides GM2 and GD1a exhibit Cancer-associated Alterations. J Glycomics Lipidomics. 2012;S2:005 [Google Scholar]

- [26].Carvalho HA, Villar RC. Radiotherapy and immune response: the systemic effects of a local treatment. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:e557s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Golden EB, Frances D, Pellicciotta I, Demaria S, Helen Barcellos-Hoff M, Formenti SC. Radiation fosters dose-dependent and chemotherapy-induced immunogenic cell death. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e28518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Purohit S, Li T, Guan W, Song X, Song J, Tian Y, et al. Multiplex glycan bead array for high throughput and high content analyses of glycan binding proteins. Nature communications. 2018;9:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jacob F, Goldstein DR, Bovin NV, Pochechueva T, Spengler M, Caduff R, et al. Serum antiglycan antibody detection of nonmucinous ovarian cancers by using a printed glycan array. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kurtenkov O, Klaamas K. Hidden IgG Antibodies to the Tumor-Associated Thomsen-Friedenreich Antigen in Gastric Cancer Patients: Lectin Reactivity, Avidity, and Clinical Relevance. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:6097647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang M, Li N, Liang Y, Liu J, Zhou Y, Liu C. Hyaluronic acid binding protein 1 overexpression is an indicator for disease-free survival in cervical cancer. International journal of clinical oncology. 2017;22:347–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.