Abstract

Prior modification of betulinic acid (1), a natural product lead with promising anti-HIV activity, produced 3-O-(3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl)betulinic acid (bevirimat, 3), the first-in-class HIV maturation inhibitor. After 3-resistant variants were found during Phase I and IIa clinical trials, further modification of 3 produced 4 with improved activity against wild-type and 3-resistant HIV-1. In continued efforts to optimize 1, 63 final products have now been designed, synthesized, and evaluated for anti-HIV-1 replication activity against HIV-1NL4–3 infected MT-4 cell lines. Five known and 21 new derivatives were as or more potent than 3 (EC50 0.065 μM), while eight new derivatives were as or more potent than 4 (EC50 0.019 μM). These derivatives feature expanded structural diversity and chemical space that may improve the antiviral activity and address the growing resistance crisis. Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) correlations were thoroughly analyzed, and a 3D Quantitative SAR model with high predictability was constructed to facilitate further rational design and development of new potent derivatives.

Keywords: Betulinic acid, Anti-HIV inhibitor, Structure-activity relationship (SAR), Quantitative SAR

1. Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-caused HIV infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) remain major global public health issues. According to the global AIDS statistics from 2020, around 38.0 million people were living with HIV, 1.7 million people were newly infected, and 690,000 people died from HIV-related causes at the end of 2019 [1]. Currently, HIV can be effectively suppressed by continuous treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), which consists of three or more antiviral agents, including nucleoside and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs and NNRTIs), protease inhibitors (PIs), and integrase inhibitors (INs) [2]. However, such combination regimens suffer from the rapid emergence of drug-resistant viral strains, toxicity caused by long-term drug treatment, and severe drug-drug interactions [3]. Thus, novel potent antiviral agents with different mode(s) of action remain urgently needed.

Natural products have long been a vital and valuable source of pharmaceutical agents. Numerous successful studies have clearly indicated that natural products with wide activity spectra often possess privileged skeletons and that modification of these natural products can lead to the discovery of new drugs and drug candidates. Modification of natural products sometimes requires big changes, such as simplifying structures or removing unnecessary chiral centers. However, most of the time, subtle chemical manipulation of the functional groups on the natural products is more appropriate [4–6].

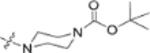

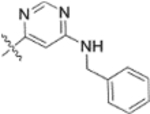

During the long-term studies of our research program to discover new anti-HIV agents with encouraging anti-HIV activity from natural products, betulinic acid (BA, 1, Fig. 1) and betulin (2, Fig. 1), two naturally occurring lupane triterpenes, were identified as promising anti-HIV natural products with a privileged skeleton [7]. Using simple esterification of the 3-OH group of 1 with 2,2-dimethylsuccinic acid, our group successfully discovered 3-O-(3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl)betulinic acid or bevirimat (BVM 3, Fig. 1), the first-in-class maturation inhibitor to treat HIV infection [8]. Compound 3 binds to the Gag polyprotein and interferes with the viral step that processes P25 Gag (CA-SP1) to the mature P24 (CA) protein, leading to the accumulation of P25 and production of immature HIV-1 particles that are noninfectious [9]. Moreover, 3 displays potent activity against virus resistant to NRTIs, NNRTIs, and PIs and exhibits synergistic effects with other AIDS drugs [10,11]. Because of its novel mechanism of action as well as significant anti-HIV activity, 3 was subjected to intensive study and succeeded in phase IIb clinical trials as an anti-AIDS drug in 2009 [12–14]. However, the efficacy of 3 was largely reduced in around 50% of patients carrying resistant viruses associated with polymorphisms in the SP1 region of HIV-1 Gag [15]. Moreover, 3 also had some problematic pharmaceutical properties, such as poor solubility [16]. Since then, extensive research has been conducted to further modify 1 and produce a new HIV-1 maturation inhibitor with potent antiviral activity and improved pharmaceutical properties [11,17–21].

Fig. 1.

The structures of betulinic acid (1), betulin (2), bevirimat (3) and its new potent derivative 4.

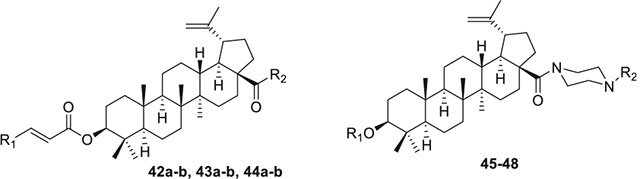

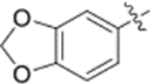

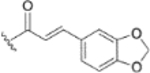

In our continued efforts to develop a new HIV-1 maturation inhibitor from 1, we successfully discovered compound 4 by integrating two “privileged fragments”, a cinnamic acid-related moiety [3,4-(methylenedioxy)cinnamic acid] and piperazine, into BVM (3) without altering the lupane triterpene skeleton. The activity of 4 was increased by three-fold against NL4–3 and 51-fold against NL4–3/V370A, which carries the most prevalent bevirimat-resistant polymorphism, when compared with that of 3. While the activity improved, the cytotoxicity remained constant. Subsequently, compound 4 was found to be a maturation inhibitor with improved metabolic stability [22].

A structure-activity relationship (SAR) study is often key to many aspects of drug discovery. Intensive SAR investigation on the core compound can guarantee successful lead optimization [23,24]. Currently, the binding mode of 3 with Gag protein remains unclear and, thus, we could not use a structure-based drug design strategy to discover a new potent derivative of 3 or 1. A systematic chemical SAR exploration or three dimensional quantitative SAR (3D QSAR) modeling is thus especially important to rationally design and develop new derivatives.

The present study is an extension of our continued efforts to develop new anti-HIV agents from 1. Our aim is to find new derivatives with potent anti-HIV activity as well as structure diversity and to systemically study the SAR of this compound type, which is crucial for the lead optimization of 1 to finally develop a new anti-HIV drug.

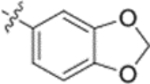

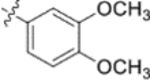

The rationale of our present synthetic work can be summarized as follows. Carbons 28 and 3, the crucial sites identified from prior studies as related to significant antiviral activity [22], were chosen for further modification. Previously, a cinnamic acid-related group and piperazine were successfully integrated as privileged fragments into 3 to produce the more potent 4. In the present work, we performed extensive modifications on the piperazine and cinnamic acid moieties. Firstly, with the derivatives in series 1, we explored the impact of placing various substituents on the phenyl ring of the cinnamic acid moiety. The compounds in series 2 were obtained by replacing the cinnamate phenyl ring with various heterocycles as well as altering the α,β-unsaturated ketone moiety of the cinnamic acid-related group. In the derivatives of series 3, the piperazine ring was replaced with different functional groups. The fourth series of derivatives was produced by modifying the 28-COOH to investigate its role on the anti-HIV activity. Finally, we assembled the functional groups found beneficial for the activity onto different positions of the skeleton of 1 to give a fifth series of derivatives. Through such modifications, a small compound library with potential antiviral activity and structural diversity was constructed. Several new potent derivatives were discovered and the SAR as well as the 3D QSAR of this compound type were also thoroughly explored.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

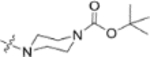

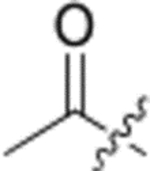

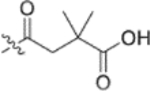

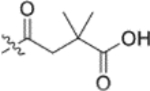

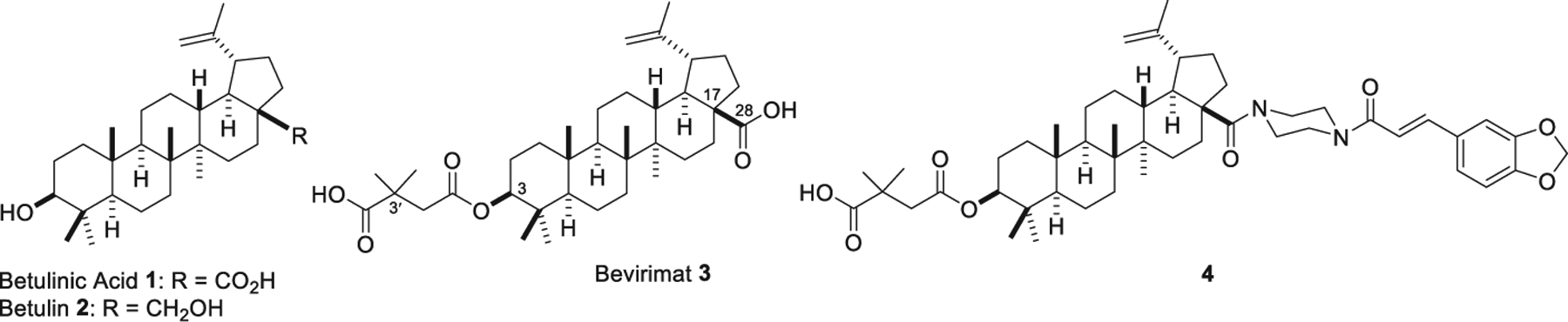

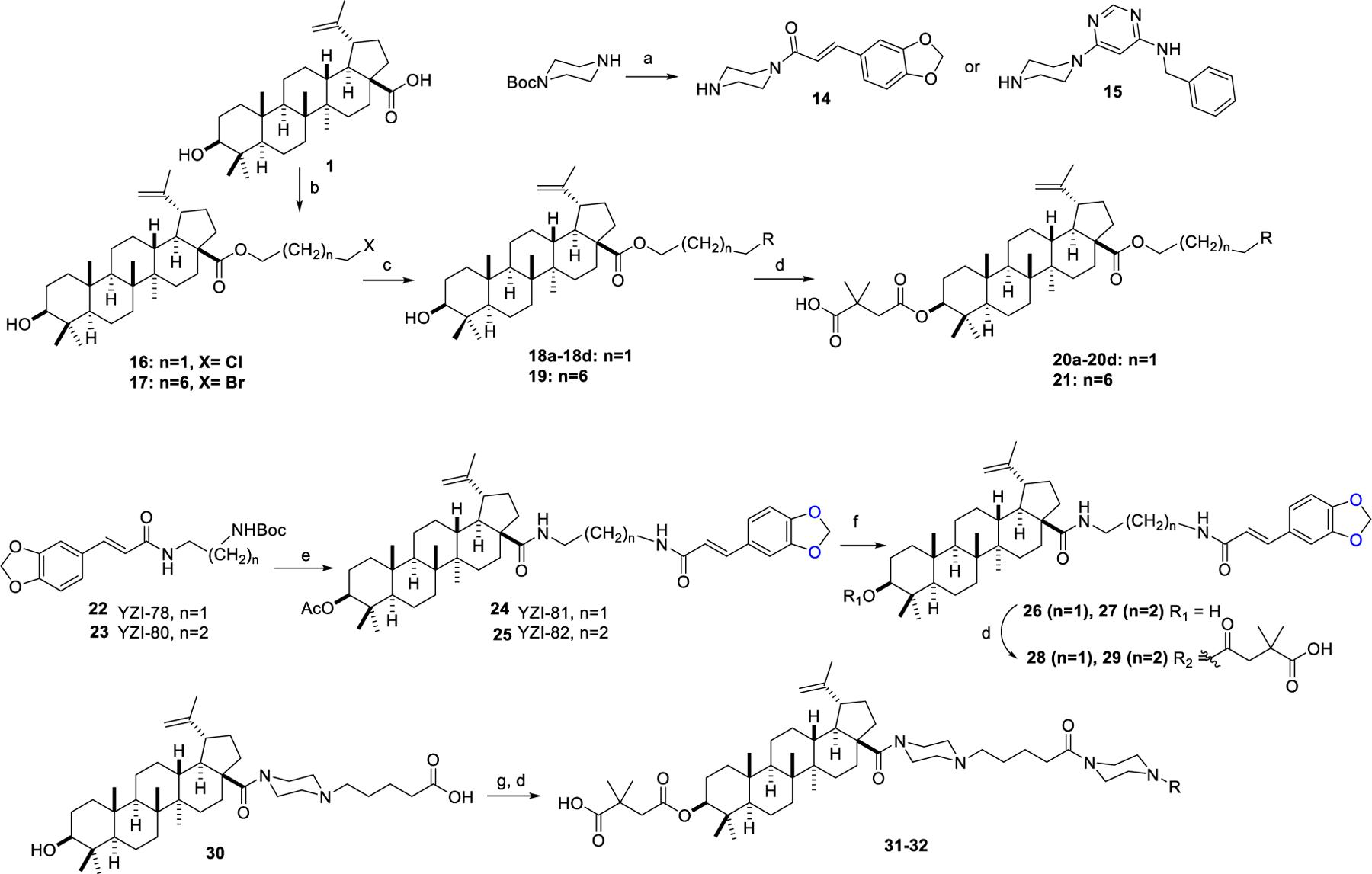

Scheme 1 depicts the syntheses of the derivatives from series 1 and 2 (4, 9b–9v, 10a–10e, and 13a–13o). Amidation of the 28-COOH of betulinic acid-3-O-acetate (3-OAc-BA, 5) with 1-Boc-piperazine produced intermediate 6. Compound 6 was converted to 7a–7v and 11a–11o by removal of the Boc protective group and acylation with various cinnamic acid analogues, which were purchased directly or synthesized according to reported methods [25–28]. Hydrolysis of the 3-OAc of 7a–7v and 11a–11o with 4N NaOH produced 8a-8v and 12a–12o, which were then esterified with 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride to yield target compounds 4, 9b–9v, and 13a–13o, respectively. Furthermore, the MOM group in 9r–9v was removed with 4N HCl in EtOAc to produce 10a–10e.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of series 1 and 2 derivatives. Reagents and conditions: (a) oxalyl chloride, DCM, then 1-Boc-piperazine, Et3N, DCM, 6h; (b) (i) TFA, DCM, 2 h (ii) acid, EDCI, HOBt, Et3N, DCM, overnight; (c) 4N NaOH, THF/MeOH, overnight; (d) 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride, DMAP, pyridine, microwave, 155 °C, 2 h; (e) 4 N HCl in EtOAc, DCM, 4 h.

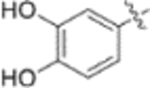

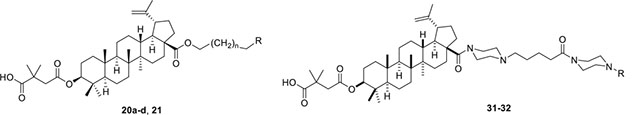

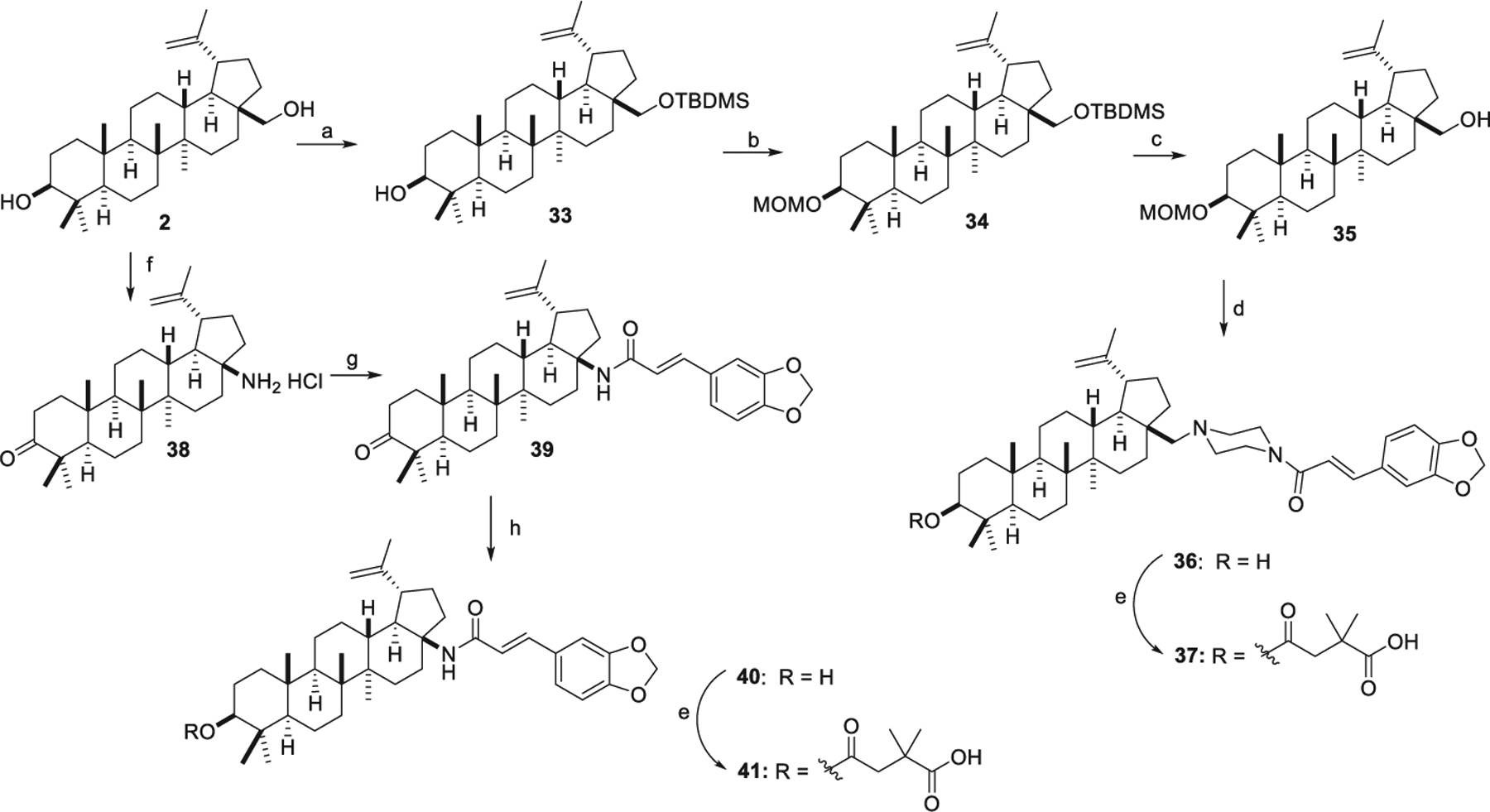

Derivatives 20a–20d, 21, 28, 29, 31, and 32 (series 3) were synthesized according to the reaction sequence in Scheme 2. Compounds 14 and 15 were obtained by coupling 1-Boc-piperazine with 3,4-(methylenedioxy)cinnamic acid or N-benzyl-6-chloropyrimidin-4-amine, respectively, following a reported method [29]. BA (1) was reacted with 1,3-dichloropropane or 1,8-dibromooctane to produce 16 and 17, respectively. Coupling 16 separately with 4-methoxycinnamic acid, 4-(dimethylamino)cinnamic acid, 2-aminothiazole, and 15 produced 18a–18d, respectively. Coupling 17 with 14 gave 19. Esterification of 18a-d and 19 with 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride produced the final products 20a-d and 21, respectively. Compounds 22 and 23 were synthesized via reaction of 3,4-(methylenedioxy)cinnamic acid with N-Boc-ethylenediamine and N-Boc-1,3-propanediamine, respectively. After removing the Boc-protecting groups from 22 and 23, the free amines were coupled with the 28-COOH of 5 to produce 24 and 25, respectively. Alkaline hydrolysis of the 3-OAc group in 24 and 25 gave 26 and 27, which were further treated with 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride to yield the products 28 and 29, respectively. Compound 30, obtained by reported methods [18], was acylated with 14 and 15 and then converted to 31 and 32, respectively, via the esterification reactions described above.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of series 3 derivatives. Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) cinnamic acid, HOBt, EDCI, Et3N, DCM, overnight for 14; halopyrimidine, DIPEA, 2-propanol, microwave, 160 °C for 15; (ii) TFA, DCM, 2 h; (b) K2CO3, DMF, TBAI, 1,3-dibromopropane or 1,8-dichlorooctane; (c) K2CO3, DMF, RH, overnight; (d) 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride, DMAP, pyridine, microwave, 155 °C; (e) TFA, DCM, 2 h, then 3-OAc-BA (5), oxalyl chloride, Et3N, DCM; (f) 4N NaOH, THF/MeOH, overnight; (g) HOBt, EDCI, Et3N, 14 for 31 or 15 for 32, overnight.

As shown in Scheme 3, starting from betulin (2), derivatives 37 and 41 in series 4 were synthesized. Treatment of 2 with TBDMSCl produced 33, which was reacted with MOMCl and DIPEA in DCM to generate 34. Removal of the TBDMS group in 34 gave 35. Treatment of 35 with oxalyl chloride, followed by coupling with 14 gave 36. Compound 37 was then obtained by the acylation reaction described above. Following the reported methods, 38 was synthesized from 2 via an oxidization reaction with Jones reagent and a Curtius rearrangement with DPPA [30]. Acylation of 38 with 3,4-(methylenedioxy)cinnamic acid gave 39. Reduction of the 3-oxo group with NaBH4 produced 40. Finally, the target product 41 was obtained via the esterification reaction described above.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of series 4 derivatives. Reagents and conditions: (a) TBDMSCl, imidazole, DMF; (b) MOMCl, DIPEA, DCM; (c) TBAF, THF; (d) oxalyl chloride, DCM, then 14; (e) 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride, DMAP, pyridine, microwave, 155 °C; (f) (i) Jones reagent, DCM; (ii) DPPA, Et3N, 1,4-dioxane, 100 °C; (iii) 12M HCl, THF; (g) 3,4-(methylenedioxy) cinnamic acid, EDCI, HOBt, Et3N, DCM; (h) NaBH4, MeOH.

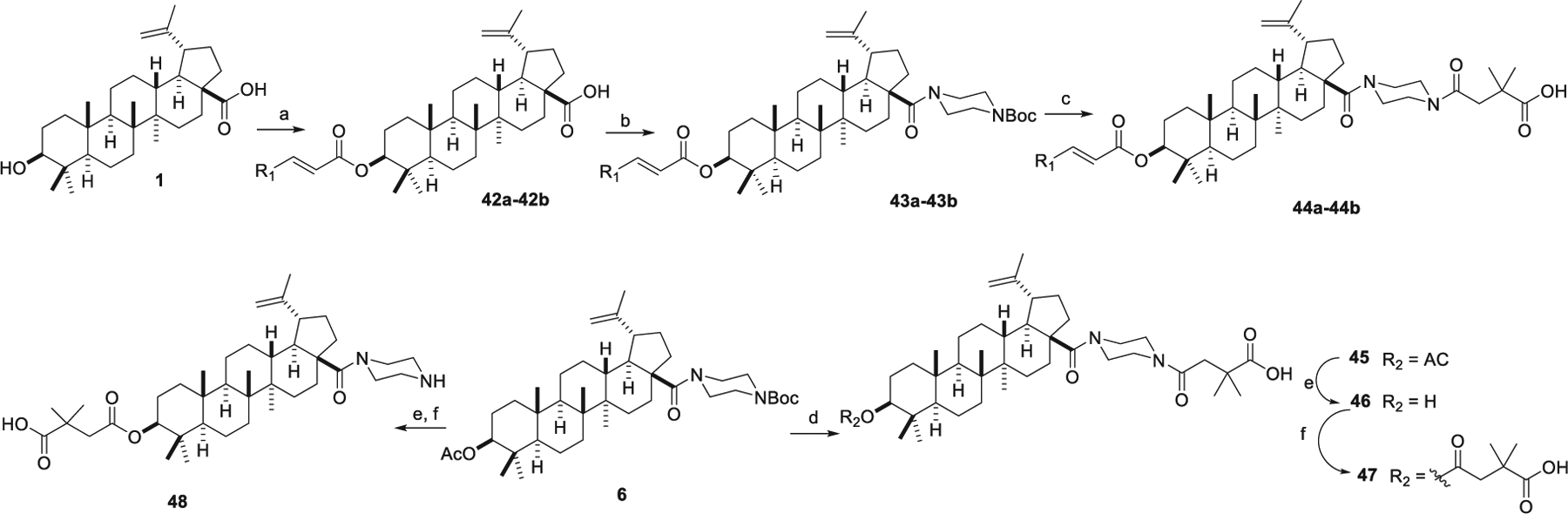

The synthetic route to derivatives 42–48 (series 5) is depicted in Scheme 4. 3,4-(Methylenedioxy)cinnamic acid and 3,4-dimethoxymethylcinnamic acid were reacted with 1 in the presence of EDCI, DMAP, and Et3N to produce 42a–42b, respectively. The acylation of 42a–42b with 1-Boc-piperazine at C-28 yielded 43a–43b, which were converted to 44a–44b through deprotection and acylation. Removal of the Boc protective group from 6 followed by reaction with 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride gave 45. Hydrolysis of the 3-OAc group in 45 yielded compound 46, which was reacted with 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride to give 47. Similarly, hydrolysis of the 3-OAc group in 6 followed by esterification with 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride yielded 48.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of series 5 derivatives. Reagents and conditions: (a) acid, EDCI, DMAP, Et3N; (b) oxalyl chloride, DCM, then 1-Boc-piperazine, Et3N, DCM; (c) (i) 4N HCl in EtOAc, DCM; (ii) 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride, DMAP, DCM; (d) (i) TFA, DCM, 2 h; (ii) 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride, DMAP, DCM; (e) 4N NaOH, THF/MeOH, overnight; (f) 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride, DMAP, pyridine, microwave, 155 °C.

2.2. Biological evaluation and SAR analysis

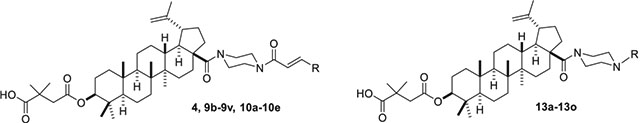

One hundred forty-nine derivatives of 1, including 136 new (7c–7q, 7s–7v, 8c–8q, 8s–8v, 9c–9q, 9s–9v, 10b–e, 11a–11o, 12a–12o, 13a–13o, 18a–18d, 19, 20a–20d, 21, 24–29, 32, 36–37, 40–41, 42a–42b, 43a–43b, 44a–44b and 45–47) and 13 previously reported (7a–7b, 7r, 8a–8b, 8r, 4, 9b, 9r, 10a, 30, 31 and 48) compounds, were evaluated in parallel with 3 (BVM) as the positive control for anti-HIV-1 replication activity against HIV-1NL4–3 infected MT-4 cell lines. The precursor compounds [3-OAc-28-modified compounds (7a–7v, 11a–11o, 24, and 25) and 3-OH-28-modified derivatives (8a–8v, 12a-12o, 18a–18d, 19, 26–27, 30, 36, and 40)] without a dimethylsuccinyl ester (an anti-maturation pharmacophore) in the molecule were uniformly inactive. These results suggested that the compounds synthesized in this study are not entry inhibitors, since prior studies have repeatedly confirmed that modification solely at the C-28 position of 1 leads only to entry inhibition rather than maturation inhibition [11,18]. The potency of the final products (4, 9b–9v, 10a–10e, 13a–13o, 20a-d, 21, 28–29, 31–32, 37, and 41–48) ranged from significant (EC50 0.012 μM, five-fold more potent than 3) to no (EC50 > 1 μM) activity, as listed in Tables 1–3. Compared with 3 (EC50 0.065 μM), 26 derivatives with substantial structural diversity, including 21 newly synthesized compounds (9f, 9i, 9t, 10b–10c, 13a–13d, 13g–13h, 13k, 13m–13o, 20c, 28–29, 32, 41 and 47), exhibited higher or comparable activity. Moreover, compared with 4 (EC50 0.019 μM), eight new derivatives (9i, 9t, 10c, 13m, 28–29, 32 and 47) showed improved or comparable activity. Based on the diverse chemical modifications and the biological data of the above derivatives on 1, SAR correlations were deduced (Figs. 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Antiviral and cytotoxic activity data of series 1 (4, 9b-v, 10a-e) and series 2 (13a-o).

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R | IC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) |

| 3 | Fig. 1 | 0.065 ± 0.0019 | >2 |

| 4 |  |

0.019 ± 0.0054 | >2 |

| 9b |  |

0.029 ± 0.0093 | >2 |

| 9c |  |

0.17 ± 0.036 | >2 |

| 9d |  |

0.15 ± 0.05 | >2 |

| 9e |  |

0.076 ± 0.031 | >2 |

| 9f |  |

0.041 ± 0.014 | >2 |

| 9g |  |

0.56 ± 0.21 | >2 |

| 9h |  |

0.13 ± 0.031 | >2 |

| 9i |  |

0.027 ± 0.0059 | >2 |

| 9j |  |

0.36 ± 0.075 | >2 |

| 9k |  |

0.11 ± 0.03 | >2 |

| 9l |  |

>1 | - |

| 9m |  |

>1 | - |

| 9n |  |

0.58 ± 0.15 | >2 |

| 9o |  |

0.75 ± 0.23 | >2 |

| 9p |  |

>1 | - |

| 9q |  |

0.2 ± 0.065 | >2 |

| 9r |  |

0.05 ± 0.021 | >2 |

| 9s |  |

0.09 ± 0.03 | >2 |

| 9t |  |

0.025 ± 0.0058 | >2 |

| 9u |  |

>1 | - |

| 9v |  |

0.46 ± 0.18 | >2 |

| 10a |  |

0.028 ± 0.0098 | >2 |

| 10b |  |

0.053 ± 0.014 | >2 |

| 10c |  |

0.018 ± 0.0075 | >2 |

| 10d |  |

>1 | - |

| 10e |  |

0.19 ± 0.046 | >2 |

| 13a |  |

0.053 ± 0.017 | >2 |

| 13b |  |

0.032 ± 0.0074 | >2 |

| 13c |  |

0.05 ± 0.019 | >2 |

| 13d |  |

0.069 ± 0.021 | >2 |

| 13e |  |

0.14 ± 0.059 | >2 |

| 13f |  |

0.18 ± 0.056 | >2 |

| 13g |  |

0.05 ± 0.019 | >2 |

| 13h |  |

0.067 ± 0.028 | >2 |

| 13i |  |

0.15 ± 0.06 | >2 |

| 13j |  |

0.59 ± 0.18 | >2 |

| 13k |  |

0.057 ± 0.017 | >2 |

| 13l |  |

0.13 ± 0.044 | >2 |

| 13m |  |

0.022 ± 0.007 | >2 |

| 13n |  |

0.037 ± 0.014 | >2 |

| 13o |  |

0.040 ± 0.010 | >2 |

Table 3.

Antiviral and cytotoxic activity data of series 4 (37, 41) and series 5 (42a–42b, 43a–43b, 44a–44b, 45–48).

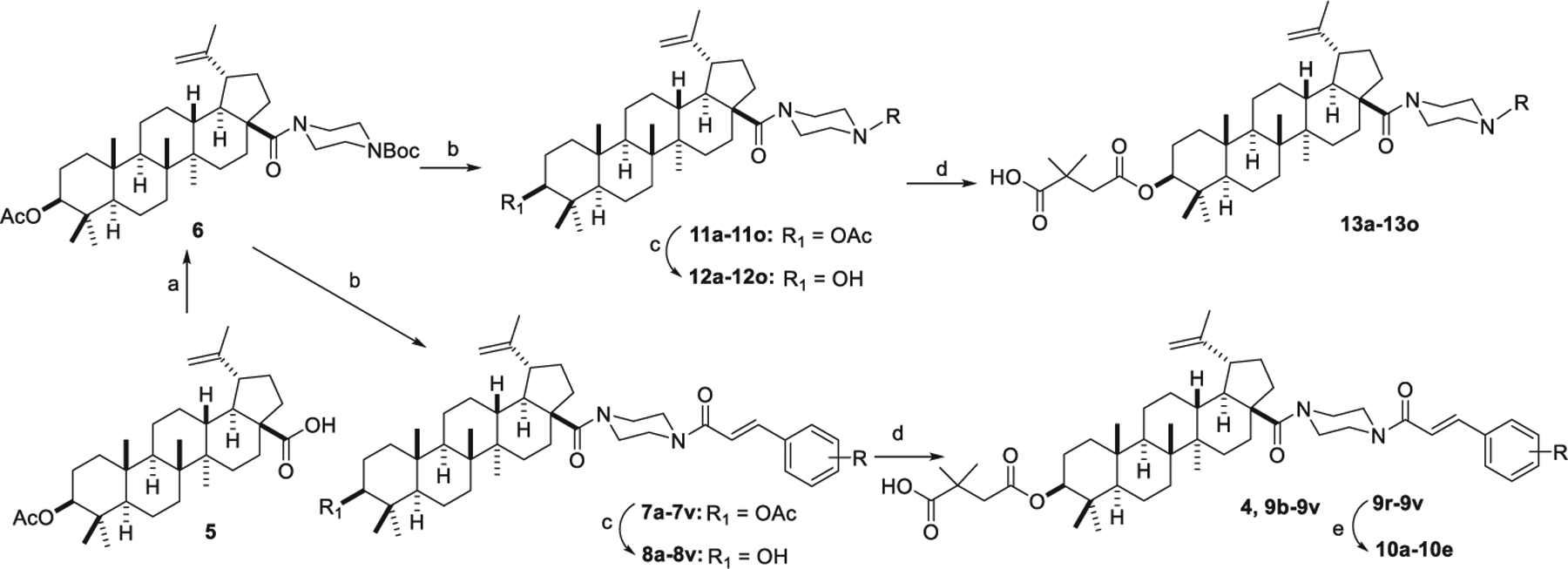

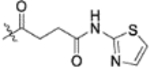

Fig. 2.

The SAR correlations from newly synthesized derivatives.

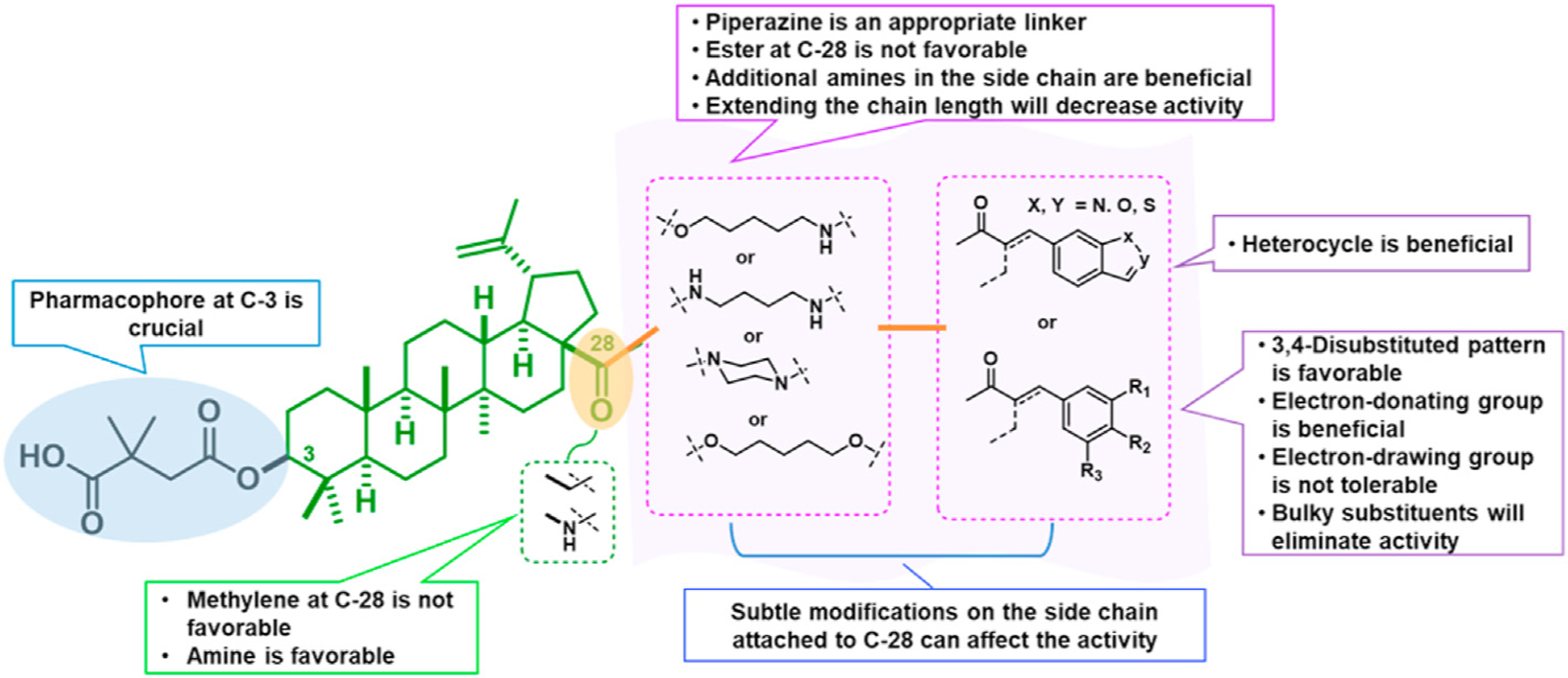

Fig. 3.

The correct natural product skeleton and privileged fragments arranged in the proper order are crucial to generate significant activity.

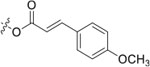

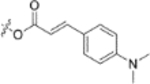

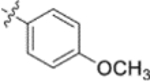

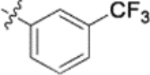

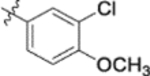

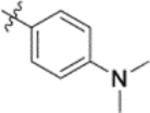

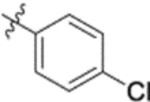

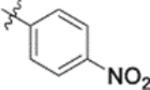

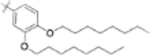

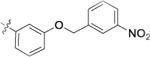

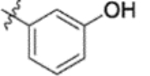

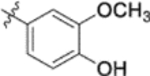

In the series 1 derivatives, 28-COOH of 3 was amidated with a piperazine that was then linked to cinnamic acid analogues with various types of aromatic substituents, including electron-withdrawing and electron-donating moieties as well as various bulky groups, to give compounds 4, 9b–9v, and 10a–10e. As shown in Table 1, 4-chloro-substituted 9j, 4-nitro-substituted 9k, and 3-trifluoromethyl-substituted 9g were less potent (EC50 0.36, 0.11, and 0.56 μM, respectively) than 4-OCH3-substituted 9e (0.076 μM), 4-(N,N-dimethylamino)-substituted 9i (0.027 μM), and 3-OCH3-substituted 9d (0.15 μM); these results indicated that an electron-donating group, such as methoxy, instead of an electron-withdrawing group, such as halide or nitro, on the phenyl ring might benefit the anti-HIV activity.

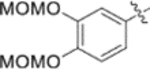

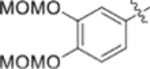

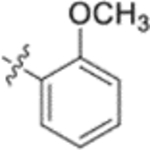

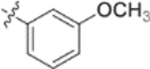

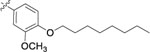

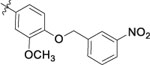

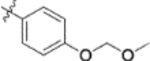

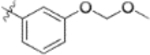

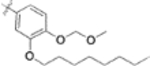

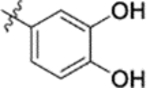

Subsequently, the following SAR correlations were observed based in the activities of various mono-substituted cinnamic acids with electron-donating groups at various positions, 2-OCH3 (9c), 3-OCH3 (9d), 4-OCH3 (9e), 4-OCH2OCH3 (4-OMOM) (9q), 3-OMOM (9s), 3-OH (10b), and 3-O-3-nitrobenzyl (9n). A two-fold decrease in potency resulted from moving the methoxy group from the 4-position on the phenyl ring (9e, EC50 0.076 μM) to the 2- (9c, EC50 0.17 μM) and 3-position (9d, EC50 0.15 μM). Comparing 9e with 9q (EC50 0.20 μM), the larger 4-OMOM group in the latter compound resulted in slightly more than 2.5-fold lower activity. Deprotection of the 3-OMOM group of 9s (EC50 0.090 μM) produced the somewhat more potent 3-OH substituted 10b (EC50 0.053 μM), which was equipotent or somewhat more potent than 9e and 3. However, subsequent conversion of 10b to 3-nitrobenzyloxy-substituted 9n led to ten-fold lower activity (EC50 0.58 μM).

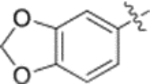

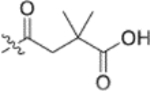

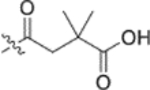

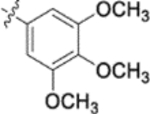

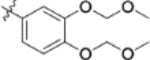

Derivatives containing poly-substituted cinnamic acids were also studied. Di- and tri-methoxy compounds (9f and 9b) were more potent than monomethoxy derivatives [(4-OCH3 (9e), 3-OCH3 (9d), and 2-OCH3 (9c)]. The rank order of activity of the substituents was 3,4-diOCH3 (9b, 0.029 μM) > 3,4,5-triOCH3 (9f, 0.041 μM) > 2-, 3-, or 4-monoOCH3 (9c–9e, 0.076−0.17 μM). These results suggested that a 3,4-substituted cinnamic acid moiety benefits the anti-HIV activity.

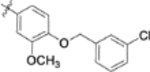

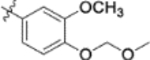

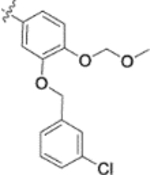

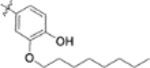

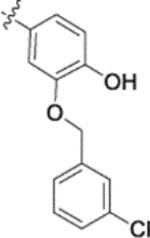

Furthermore, the activities of other derivatives with a 3,4-disubstituted phenyl ring (4, 9h, 9l–9p, 9r, 9t–9u, 10a, 10c–10e) were analyzed. Among them, compounds with 3,4-methylenedioxy (4), 3-OCH3-4-OMOM (9t), 3,4-diOH (10a), and 3-OCH3-4-OH (10c) substitution showed the greatest activity with respective EC50 values of 0.019, 0.025, 0.028 and 0.018 μM and were two-to three-fold more potent than 3. Compared with 3,4-diOCH3 9b, 3,4-diOMOM 9r was slightly less potent, while 3,4-diOH 10a was equipotent. Moreover, with an EC50 value of 0.018 μM, 10c was as potent or more potent than 4 and 9b, respectively. The 3-OCH3-4-OMOM substituted 9t also exhibited potent activity (EC50 0.025 μM), although it was slightly less potent than 10c. However, replacing the 3-OCH3 in 9b with chlorine (9h, EC50 0.13 μM) decreased the activity by five-fold. This result again confirmed that an electron-withdrawing substituent on the phenyl ring is not conducive to good activity. Moreover, incorporation of various bulky substituents, such as additional phenyl rings or octyl ether chains at either the 3- or 4-position of the cinnamate phenyl ring (9l–9p, 9u–9v, and 10d–10e) was detrimental. Only 9o, 9v, and 10e exhibited any activity (EC50 0.75, 0.46 μM, and 0.19 μM respectively); the other six compounds were inactive (EC50 > 1 μM). These results clearly indicated that a bulky group on the phenyl ring will diminish the anti-HIV activity.

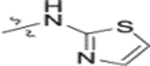

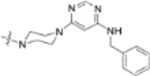

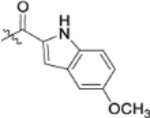

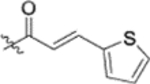

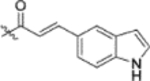

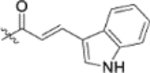

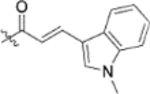

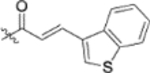

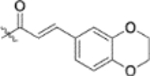

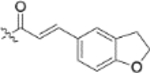

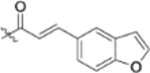

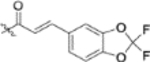

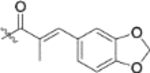

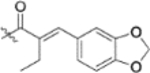

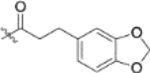

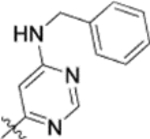

To further explore how the cinnamic fragment affected the anti-HIV activity, the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl was altered, and the phenyl ring was replaced with various heterocycles. This subset of derivatives contained 15 compounds (13a–13o). As shown in Table 1, their anti-HIV EC50 values ranged from 0.15 to 0.022 μM. Saturation of the cinnamate double bond of 4 resulted in 13m, which exhibited equivalent activity (EC50 0.022 μM) to the parent compound. Addition of a methyl (13k, EC50 0.057 μM) or ethyl (13l, EC50 0.13 μM) group at the α-carbon of the cinnamate double bond led to a slight or ten-fold decrease, respectively, in the activity of 4. The replacement of the cinnamate phenyl ring with various heterocycles, such as thiophene (13b), indole (13c, 13d), 1,4-benzodioxane (13g), and 2,3-dihydrobenzofuran (13h), resulted in compounds with good activity (EC50 0.032–0.069 μM), slightly less potent than 4 but more potent or comparably potent to 3. However, compounds containing the heterocycles N-methylindole (13e), 2,3-dihydrobenzothiophene (13f), and benzofuran (13i) were ten-fold less potent (EC50 0.14–0.18 μM) than 4, while compound 13j with 2,2-difluorobenzo-1,3-dioxole was even less active (EC50 0.59 μM). Furthermore, the replacement of the entire cinnamate fragment with various moieties containing heterocycles led to compounds [13a (EC50 0.053 μM, 5-methoxy-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid), 13n (EC50 0.037 μM, N-benzylpyrimidin-4-amine), and 13o (EC50 0.040 μM, 4-oxo-4-(thiazol-2-ylamino)butanoic acid)] that were equipotent to 3. Overall, the above results clearly indicated that varying the cinnamic acid fragment can lead to potent derivatives of 4 with notable structure diversity. However, subtle modifications in this area can either decrease or increase the potency.

Piperazine is a well-known privileged fragment found in many anti-HIV drugs. In our previous work, it served as a good linker to connect the triterpenoid skeleton to various cinnamic acids. In the third series of synthetic derivatives, the effects of different linkers were studied (Table 2). The first change was to replace the piperazine linker in 9e (EC50 0.076 μM) and 9i (EC50 0.027 μM) with a propane-1,3-diol linker in 20a and 20b, respectively. Compound 20a was 11-fold less potent than the piperazine-linked 9e and compound 20b was inactive (EC50 > 1 μM). In this instance, the change from amide (piperazine) to ester (propanediol) groups was detrimental. Three additional new derivatives (20c, 20d, and 21) contained an ester rather than amide bond with the triterpenoid 28-COOH. Compound 20c [3-(thiazol-2-ylamino)propan-1-ol side chain] showed equivalent activity with 13o [4-oxo-4-piperazin-1-yl)-N-(thiazol-2-yl)butanamide side chain]. However, the potency decreased significantly between 13n (EC50 0.037 μM) and 20d (EC50 0.43 μM). While both compounds contain a piperazine linked to a terminal pyrimidine, the connection to triterpenoid 28-COOH is directly to the piperazine in the former compound but through an added propanol sequence in the latter compound. Most notably, the potent activity (EC50 0.019 μM) of our prior lead 4 was abolished in 21 (EC50 > 1 μM), which contains an even longer alkanol motif between the 28-COOH and the piperazine in the side chain. Moreover, we also synthesized 28 and 29, in which the cyclic piperazine linker in 4 was replaced with linear 1,2-diaminoethane and 1,3-diaminopropane linkers, respectively. Compounds 28 and 29 exhibited significant activity with EC50 values of 0.013 and 0.017 μM, slightly more potent and equipotent, respectively, with 4. Thus, both linear and cyclic diamines of similar length led to potent compounds. Finally, new derivatives 31 and 32 were produced by inserting a piperazinepentanoic motif into the side chain at C-28 of 4 and 13n, respectively. Accordingly, the connection between the triterpenoid 28-COOH and the terminal substituted cinnamic acid (31) or pyrimidine (32) is piperazine-5-oxopentane-piperazine. Both compounds exhibited the most potent activity in this study with an EC50 value of 0.012 μM. Thus, a second piperazine ring in an extended side chain was much more favorable than an alkanol extension (compare 31 versus 21). Overall, the above results clearly indicated that the side chain attached to the 28-COOH of the triterpenoid is crucial to the anti-HIV activity. An appropriate side chain can help to optimize the activity, while an unfavorable one can abolish the activity. An amide formed between a piperazine or primary diamine with the triterpenoid 28-COOH is generally more beneficial for antiviral activity than an ester. Additional heteroatoms, particularly nitrogen, within the side chain can favor the activity. Also, the length of the side chain can affect the activity.

Table 2.

Antiviral and cytotoxic activity data of series 3 (20a–20d, 21, 28, 29, 31, 32).

In our fourth series of derivatives, we investigated how changing the substituent on position-17 of the triterpenoid affected the anti-HIV activity. Accordingly, compounds 37 and 41 were synthesized and their activities were evaluated (Table 3). Interestingly, the change of the carbonyl in the 28-amide of 4 (EC50 0.019 μM) to a methylene in 37 (EC50 > 1 μM) eliminated the anti-HIV activity. Meanwhile, the conversion of the 28-CH2OH of 2 to a primary amine (NH2) followed by acylation with 3,4-(methylenedioxy)cinnamic acid produced 41 (EC50 0.066 μM), which showed comparable activity to 3, although it was less potent than 4. These results indicated that, in addition to changes within the side chain connected to C-28, modification of the C-28 carbonyl itself could significantly affect the activity.

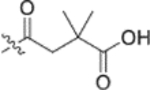

Finally, the dimethylsuccinic acid, piperazine, and cinnamic acid segments were placed at different points of the triterpenoid skeleton of 1. The anti-HIV results for this fifth series of ten synthetic derivatives (42a–42b, 43a–43b, 44a–44b, 45–48) are shown in Table 3. Compounds without a succinate ester at any position (i.e., 42a–42b with a substituted cinnamate ester at C-3 and no side chain on the 28-COOH as well as 43a–43b with the same esters at C-3 and a tert-butyl piperazine-1-carboxylate amide on the 28-COOH) were totally inactive (EC50 > 1 μM). Likewise, compounds 44a–44b, in which a dimethyl succinate has replaced the tert-butyl carboxylate on the piperazine terminus, were also inactive. In these two compounds, the cinnamate and succinate groups were in reversed positions from those in the active derivatives 4 and 10a, respectively. Furthermore, compounds 45 and 46, which have the same side chain as 44a–44b on the triterpenoid C-28 but an acetate ester and hydroxyl group, respectively, rather than cinnamate ester at C-3, were inactive. Finally, only the two compounds with a dimethyl succinate ester at C-3 (47 and 48) showed anti-HIV activity. Compound 47, analogous to the prior lead 4 (EC50 0.019 μM) but with a dimethylsuccinic acid rather than 3,4-(methylenedioxy) cinnamic acid linked to the piperazine on the triterpenoid 28-COOH, exhibited extremely potent activity (EC50 0.014 μM). However, compound 48, which lacks the dimethyl succinate amide on the piperazine, showed only marginal activity (EC50 0.49 μM); it was 35-fold less potent than 48. These results clearly indicated that a dimethyl succinate ester at C-3 is essential for anti-HIV activity. Thus, the correct natural product skeleton and privileged fragments arranged in the proper order are crucial to generate significant activity.

2.3. 3D QSAR study

The SAR study clearly indicated that subtle modifications on the skeleton of 1 are crucial for discovering new derivatives with potent activities. Especially, certain small alterations at C-28 and C-3 led to the large differences in the activity. Therefore, to further identify and understand the positive and negative effects of the various modifications on the anti-HIV activity, a 3D QSAR analysis was performed using the Discovery Studio software suite (DS 3.5, Accelrys Co. Ltd). The 3D QSAR models were constructed and validated using the data from 42 derivatives with anti-HIV EC50 values ranging from 0.017 to 0.85 μM.

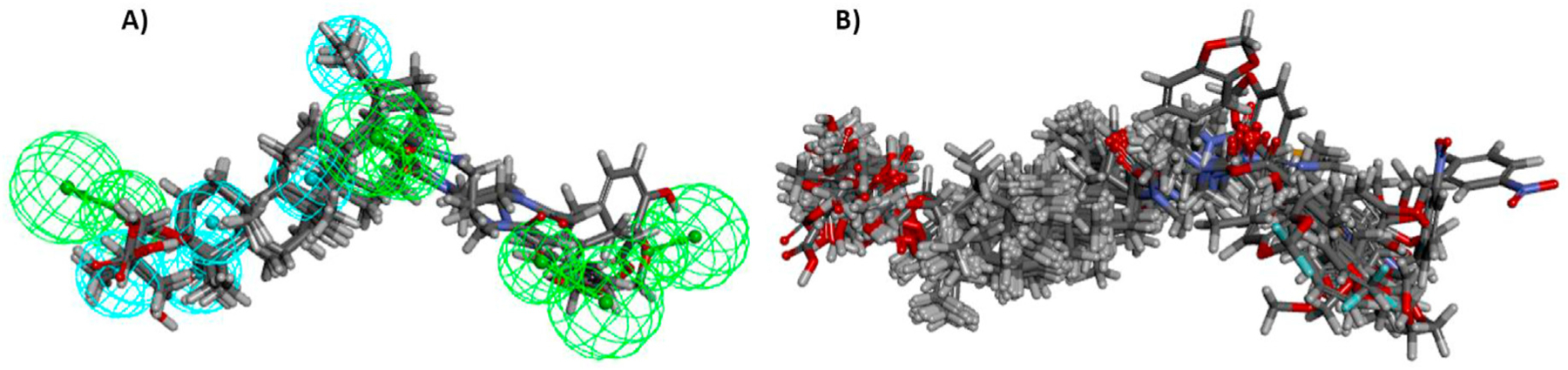

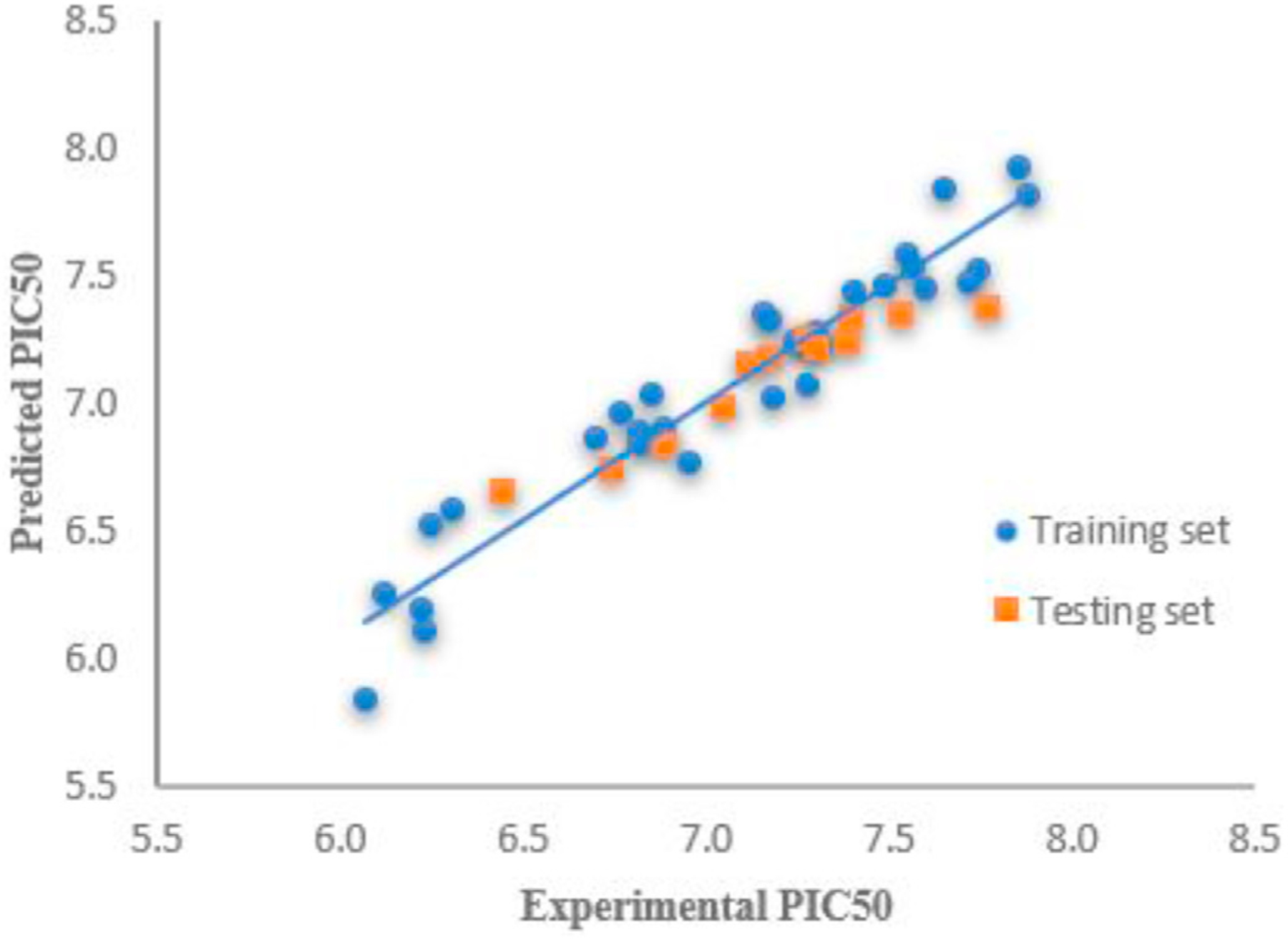

As shown in Table 4, the 42 derivatives were divided into training set (30 derivatives) and testing set (12 compounds). Since the molecular alignment is crucial for constructing a reliable 3D QSAR model, a pharmacophore (Fig. 4A) was generated initially within four representative active derivatives (4, 10c, 28, 29) using the common feature pharmacophore generation protocol in DS 3.5 and based on detailed and procedures reported in the literature [31,32]. This module was designed to identify the chemical features shared by several active ligands and the relative alignments of the ligands with a pharmacophore that express common features. Subsequently, the structures of all 30 derivatives in the training set were aligned to generate a common feature pharmacophore (Fig. 4B). A partial Least-Squares (PLS) model was built with energy grids as descriptors. The energy grids are computed using two probe types designed to measure electrostatic and steric effects. The inhibition constants, expressed in PIC50 (−log IC50), were correlated with the steric and electrostatic fields of each compound in the training set. The assembled 3D QSAR model exhibited a good correlation coefficient (r2) of 0.92 and a good predictivity with a cross-validation correlation coefficient (q2) of 0.51. The linear correlations between the experimental results and predictive values are shown in Fig. 5 and listed in Table 4. The r2 and q2, which represent the model’s predictive ability and self-consistence, are two key indexes to evaluate the quality of the PLS model. The reasonably high r2 and q2 values indicated that the generated model has a high predictive ability.

Table 4.

Predicted PIC50 values from QSAR model compared with the experimental PIC50 values.

| Cmpd | PIC50 (experimental) | PIC50 (predicted) | Residual | Cmpd | PIC50 (experimental) | PIC50 (predicted) | Residual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 7.19 | 7.02 | 0.17 | 13a | 7.28 | 7.07 | 0.21 |

| 4 | 7.72 | 7.47 | 0.25 | 13b | 7.49 | 7.45 | 0.04 |

| 9b* | 7.54 | 7.35 | 0.19 | 13c | 7.30 | 7.26 | 0.04 |

| 9c | 6.77 | 6.95 | −0.18 | 13d | 7.16 | 7.34 | −0.18 |

| 9d | 6.82 | 6.83 | −0.01 | 13e | 6.85 | 7.03 | −0.18 |

| 9e* | 7.12 | 7.15 | −0.03 | 13f* | 6.74 | 6.74 | 0.00 |

| 9f* | 7.39 | 7.23 | 0.16 | 13g | 7.30 | 7.27 | 0.03 |

| 9g | 6.25 | 6.51 | −0.26 | 13h* | 7.17 | 7.18 | −0.01 |

| 9h* | 6.89 | 6.84 | 0.05 | 13i | 6.82 | 6.88 | −0.06 |

| 9i | 7.57 | 7.52 | 0.05 | 13j | 6.23 | 6.18 | 0.05 |

| 9j* | 6.44 | 6.65 | −0.21 | 13k | 7.24 | 7.24 | 0.00 |

| 9k | 6.96 | 6.76 | 0.20 | 13l | 6.89 | 6.89 | 0.00 |

| 9n | 6.24 | 6.11 | 0.13 | 13m | 7.66 | 7.83 | −0.17 |

| 9o | 6.12 | 6.25 | −0.13 | 13o* | 7.40 | 7.33 | 0.07 |

| 9q | 6.70 | 6.85 | −0.15 | 20a | 6.07 | 5.84 | 0.23 |

| 9r* | 7.30 | 7.22 | 0.08 | 20c | 7.41 | 7.43 | −0.02 |

| 9s* | 7.05 | 6.98 | 0.07 | 28 | 7.89 | 7.81 | 0.08 |

| 9t | 7.60 | 7.45 | 0.15 | 29* | 7.77 | 7.37 | 0.40 |

| 10a | 7.55 | 7.58 | −0.03 | 41 | 7.18 | 7.32 | −0.14 |

| 10b* | 7.28 | 7.25 | 0.03 | 47 | 7.85 | 7.92 | −0.07 |

| 10c | 7.74 | 7.52 | 0.22 | 48 | 6.31 | 6.58 | −0.27 |

Compounds of testing set.

Fig. 4.

(A) The common feature pharmacophore model generated by representative derivatives 4, 10c, 28 and 29. Pharmacophore features colored as follows: H-bond acceptor (green), hydrophobic group (cyan). (B) Alignment of all 30 derivatives of training set to the common feature generated.

Fig. 5.

Correlation analysis of predicted PIC50 values by QSAR model and experimental PIC50 values.

To further evaluate the stability and predictive ability of the model, the PIC50 value for the 12 compounds in the test set was calculated. As seen in Fig. 5 and Table 4, the calculated values using the constructed model are in good agreement with the experimental data with an r2 value of 0.91. Overall, these statistical data indicate that the constructed 3D QSAR model has reliable predictive ability.

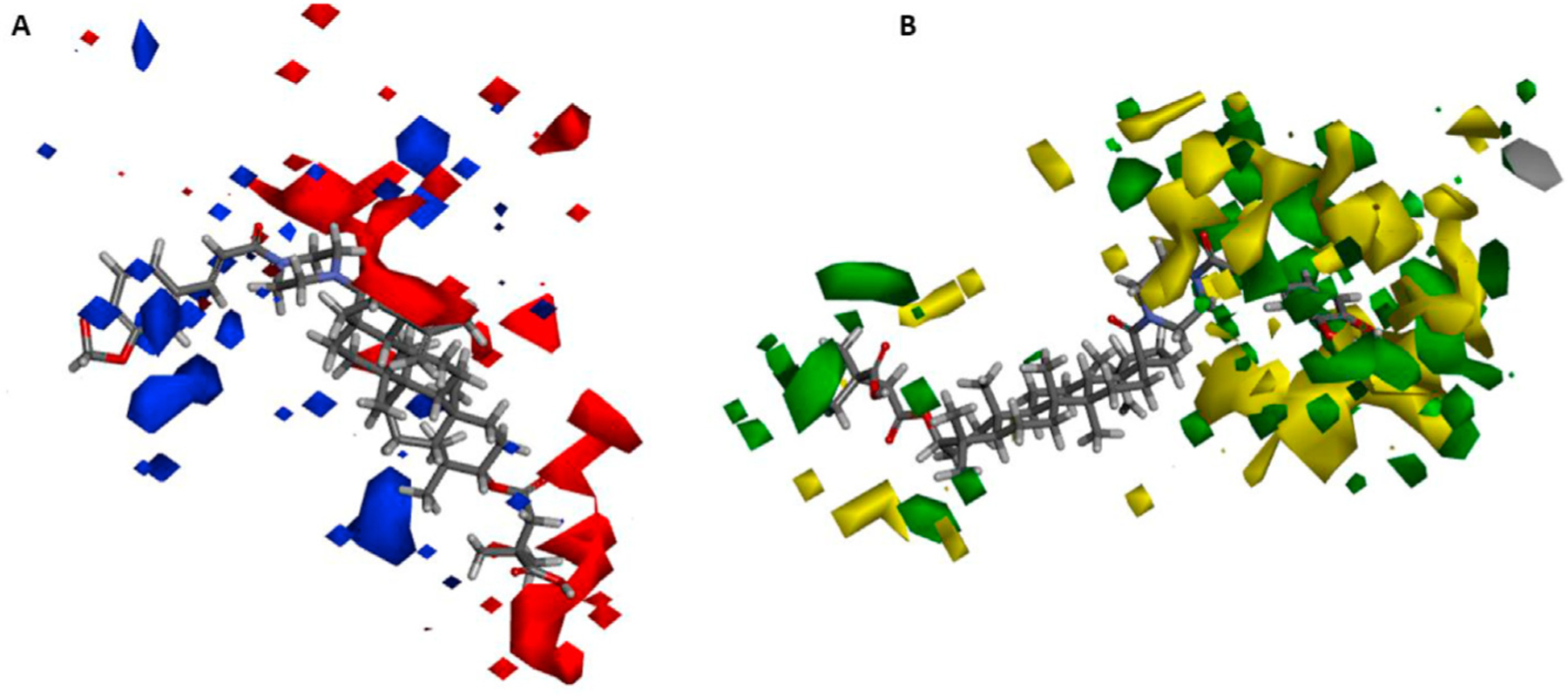

The QSAR result was further represented as 3D contour maps to identify the effects of steric and electrostatic fields on the activity value of the compounds. Fig. 6A shows the model coefficients on electrostatic potential grids. To aid the visualization, compound 4 was used as a reference molecule in the map. Positive coefficients were colored blue, while negative coefficients were colored red. The terminal carboxylic acid of the C-3 acyl side chain was covered with a red contour, indicating that more negative charge in this area should increase the activity. Moreover, another red contour was located near the piperazine ring, which again suggested that negative charge in this region should increase the activity. The model coefficients on van der Waals grids are shown in Fig. 6B. Again, derivative 4 is shown as a reference molecule to aid visualization. A large van der Waals favorable region (green contour) is located near the C-3′ of the C-3 acyl side chain, suggesting that van der Waals forces in this region will affect the activity positively. Moreover, the phenyl ring of the cinnamic acid is in a van der Waals favorable region, which is surrounded by a large van der Waals unfavorable area (yellow contour); thus, while the introduction of a phenyl/aromatic ring is beneficial to the activity, bulky groups in this area may decrease the activity.

Fig. 6.

(A) 3D QSAR coefficients on electrostatic potential grids. Blue represents positive coefficients, red represents negative coefficients. (B) 3D-QSAR model coefficients on van der Waals grids. Green represents positive coefficients; yellow represents negative coefficients.

2.4. In silico druglike properties

The druglike properties, including solubility, CYP2D inhibition level, and hepatotoxicity, were predicted with the ADMET module of Discovery Studio 3.5 (Table S1). The derivatives containing various heteroatoms or heterocycles, were predicted to be more soluble than 3. Moreover, none of the synthesized derivatives were predicted to be CYP2D inhibitors. The hepatotoxicity values suggested that all derivatives were unlikely to cause dose-dependent liver injury.

3. Conclusion

A small library of 1-derivatives was assembled. Among the 63 final products, 21 newly synthesized and 5 known derivatives exhibited higher or equivalent antiviral activity compared with 3 (EC50 0.065 μM). Furthermore, 8 (9i, 9t, 10c, 13m, 28, 29, 32 and 47) of the 21 new compounds showed improved or similar activity compared with 4 (EC50 0.019 μM).

Based on the obtained data, a thorough SAR analysis was conducted. The potency depended on the appropriate identity and assembly of functional groups. Notably, a dimethyl succinate ester at C-3 was essential for anti-HIV activity. Modification, even small variations, of the 28-carbon and its attached side chain had significant effects. An amide (CO-N) formed between the 28-COOH and a piperazine or primary amine was better than an ester (CO-O). The introduction of heteroatoms, such as amine nitrogens, in the C-28 side chain and the extension of the side chain with another fragment, such as cinnamic acid, were important for increased activity. Small electron donating groups on the cinnamic acid phenyl ring, particularly at position-3 and -4, appeared beneficial. Furthermore, a highly predictive QSAR model was constructed to assist in the analysis and design of new derivatives, as well as to elucidate possible drug-protein interactions.

The new structurally diverse derivatives offer more opportunities to address the growing anti-HIV resistance crisis. The potent compounds with added heteroatoms might have better pharmaceutical properties compared to prior antiviral 1-derivatives. We are evaluating the new potent derivatives against various virus types, pursuing mechanism of action studies, and designing new derivatives based on the SAR and QSAR analyses. We will report the results in due course.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Chemistry

All reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or other commercial source and used without further purification. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on an Inova 400 MHz spectrometer with Me4Si (TMS) as internal standard. Unless otherwise indicated, the solvent used was CDCl3. High resolution mass spectra were obtained on a Shimadzu LCMS-IT-TOF with ESI interface. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Merck precoated silica gel 60 F-254 plates. HPLC purity determinations were conducted using a Shimadzu LCMS-2010 with Shimadzu SPD-M20A detector at 205 or 220 nm wavelength and a Grace Alltima 2.1 mm × 150 mm HP C18 5 μm column.

4.1.1. General procedures for the synthesis of 4, and 9b–9v

Starting from betulinic acid-3-O-acetate (3-OAc-BA) obtained using the previously reported methods [33], the intermediates 6, 7a–7v, and 8a–8v were prepared according to the methods described in our prior research publication [22].

Products 4 and 9b–9v were synthesized as previously described [22]. In brief, the appropriate starting compound (8a–8v, 1 equiv), 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride (5 equiv), and DMAP (1 equiv) were dissolved in anhydrous pyridine. The mixture was stirred at 155 °C for 2 h in a microwave oven (Biotage). The reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc, neutralized with HCl (1N), and then extracted twice with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give the crude product, which was chromatographed using a silica gel column to give the pure product (4 and 9b-v).

4.1.1.1. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)acryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (9f).

Yield: 49.1 mg (39%), starting from 106.7 mg of 8f; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.62 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 6.75 (2H, s, 2,6-Ph), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 4.73 and 4.59 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.49 (1H, dd, J = 6.0, 10.0 Hz, H-3), 3.90 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 3.88 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.68 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.98 (1H, m, H-19), 2.67 and 2.60 (1H each, d, J = 16.8 Hz, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30),1.30 and 1.29 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.93 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 0.82 (3H, s, CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 2.85–0.80 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.3, 174.0, 171.0, 165.7, 152.7, 152.7, 151.1, 143.3, 139.5, 131.6, 115.2, 109.3, 103.3, 103.3, 81.5, 59.6, 56.4, 56.4, 55.6, 55.6, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.6, 44.7, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.8, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.8, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.1, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C52H77N2O9, 873.5629 [M+H+]; found, 873.5593.

4.1.1.2. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)acryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (9i).

Yield: 18.2 mg (17%), starting from 89.4 mg of 8i; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.68 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.45 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2,6-Ph), 6.71–6.58 (3H, overlap, 3,5-Ph, CH =), 4.75 and 4.61 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.50 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, H-3), 3.68 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 3.04 (6H, s, 2 × N-CH3), 2.97 (1H, m, H-19), 2.66 (2H, m, H-2′), 1.71 (3H, s, H-30), 1.31 and 1.26 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.98 (3H, s, CH3), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.86 (3H, s, CH3), 0.85 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 2.85–0.81 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.9, 173.9, 171.0, 165.7, 151.1, 149.3, 143.4, 128.7, 128.7, 125.5, 114.8, 113.0, 113.0, 109.4, 81.5, 55.6, 55.6, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.7, 41.9, 41.4, 41.4, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.8, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.1, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C51H76N3O6, 826.5734 [M+H+]; found, 826.5752.

4.1.1.3. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(3-methoxy-4-(methoxymethoxy)phenyl) acryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (9t).

Yield: 38.4 mg (41%), starting from 80.0 mg of 8t; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.65 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.15 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, 5-Ph), 7.10 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, 6-Ph), 7.04 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, Ph-2), 6.73 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 5.26 (2H, s, O-CH2-O), 4.73 and 4.59 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.48 (1H, dd, J = 6.0, 9.6 Hz, H-3), 3.93 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.67 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 3.52 (3H, s, OCH3), 2.98 (1H, m, H-19), 2.67 and 2.56 (1H each, d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30), 1.30 and 1.29 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.93 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 2.86–0.75 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.4, 173.9, 171.0, 166.0, 151.0, 149.8, 148.2, 143.4, 129.4, 121.4, 116.0, 114.7, 110.8, 109.4, 95.2, 81.5, 56.3, 56.0, 55.6, 55.6, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.7, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.7, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.1, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C52H77N2O9, 873.5629 [M+H+]; found 873.5601.

4.1.2. General procedures for the synthesis of 10a–10e

Products 10a–10e were synthesized as previously described [22]. In short, to a solution of 9r–9v (1 mmol) in DCM (5 mL) was added 4 N HCl in EtOAc (5.5 mL, 22 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 4 h at rt. The solvent was then removed in vacuo. The residue was purified by chromatography on a silica gel column to give the pure compound.

4.1.2.1. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)acryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (10b).

Yield: 46.7 mg (82%), starting from 60.2 mg of 9s; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.57 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.23 (1H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, 5-Ph), 7.07 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, 6-Ph), 7.02 (1H, s, 2-Ph), 6.94 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 6.86 (1H, m, Ph-4), 4.73 and 4.60 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.47 (1H, dd, J = 5.6, 9.8 Hz, H-3), 3.70 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.97 (1H, m, H-19), 2.65 and 2.57 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.71 (3H, s, H-30), 1.27 (6H, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 1.01 (3H, s, CH3), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.88 (3H, s, CH3), 0.86 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.85–0.79 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 182.0, 174.0, 171.0, 166.3, 156.1, 151.1, 143.4, 136.3, 130.3, 121.3, 119.7, 116.4, 115.7, 109.4, 81.6, 55.5, 55.5, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.8, 50.7, 45.6, 44.8, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.8, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.7, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.1, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C49H69N2O7, 797.5105 [M−H+]; found, 797.5111.

4.1.2.2. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acryloyl) piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (10c).

Yield: 70.3 mg (77%), starting from 96 mg of 9t; white amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.61 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.07 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 8.4 Hz, 6-Ph), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, Ph-2), 6.89 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, 5-Ph), 6.67 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 4.70 and 4.56 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.44 (1H, dd, J = 6.0, 9.6 Hz, H-3), 3.91 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.64 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.95 (1H, m, H-19), 2.62 and 2.53 (1H each, d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-2′), 1.66 (3H, s, H-30), 1.26 and 1.25 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.90 (3H, s, CH3), 0.81 (3H, s, CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 0.78 (3H, s, CH3), 2.83–0.73 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 181.3, 174.0, 171.0, 165.9, 151.0, 149.1, 147.4, 143.2, 130.1, 122, 117.1, 114.5, 113.6, 109.4, 81.5, 56.1, 55.6, 55.6, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.8, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.7, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.1, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C50H71N2O8, 827.5211 [M−H+]; found 827.5231.

4.1.3. General procedures for the synthesis of 13a–13o

Compound 6 was acylated with various acids, purchased or prepared according to the literature, to yield 11a–11o, [25,26]. Intermediates 11a–11o and 12a–12o were prepared as previously described [22]. Products 13a–13o were synthesized from 12a–12o following the same procedure described for preparation of 3 and 9b–9v.

4.1.3.1. 4-(28-(4-(5-Methoxy-1H-indole-2-carbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13a).

Yield: 35.9 mg (43%), starting from 70.2 mg of 12a; white amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.55 (1H, s, NH), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2-Ph), 7.05 (1H, s, 5-Ph), 6.97 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, Ph-3), 6.71 (1H, s, CH =), 4.74 and 4.60 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.47 (1H, dd, J = 6.0, 10.0 Hz, H-3), 3.90 and 3.71 (4H each, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 3.85 (3H, s, OCH3), 2.99 (1H, m, H-19), 2.67 and 2.57 (1H each, d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30),1.28 (6H, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.97 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.82 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 2.86–0.80 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 182.0, 174.0, 171.0, 170.3, 154.7, 151.1, 138.8, 131.8, 131.1, 115.0, 112.3, 111.8, 111.2, 109.4, 81.6, 55.8, 55.6, 55.6, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.7, 43.8, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.9, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.0, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C50H71N3O7Na, 848.5190 [M+Na+]; found, 848.5257.

4.1.3.2. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(thiophen-2-yl)acryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13b).

Yield: 29.3 mg (22%), starting from 110.2 mg of 12b; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.84 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.34 (1H, d, J = 4.0 Hz, CH =), 7.24 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, CH =), 7.06 (1H, t, J = 4.0 Hz, CH =), 6.52 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 4.73 and 4.59 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.48 (1H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, H-3), 3.67 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.98 (1H, m, H-19), 2.66 and 2.56 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30), 1.30 and 1.28 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.93 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 0.82 (3H, s, CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 2.85–0.80 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 182.0, 174.0, 171.0, 166.0, 151.0, 139.0, 131.5, 129.7, 129.3, 128.4, 123.7, 109.4, 81.5, 55.6, 55.6, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.7, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.8, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.9, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.1, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C47H69N2O6S, 789.4876 [M+H+]; found, 789.4859.

4.1.3.3. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(1H-indol-5-yl)acryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13c).

Yield: 51.5 mg (51%), starting from 85.2 mg of 12c; white amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.41 (1H, s, NH), 7.86 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.81 (1H, s, Ph-2), 7.43 (1H, d, J = 8.4, Ph-6), 7.38 (1H, d, J = 8.4, Ph-5), 7.24 (1H, t, J = 2.4 Hz, CH =), 6.83 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 6.58 (1H, brs, CH =),4.73 and 4.59 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.48 (1H, dd, J = 5.6, 9.4 Hz, H-3), 3.68 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.99 (1H, m, H-19), 2.65 and 2.56 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30), 1.27 and 1.26 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.93 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 0.77 (3H, s, CH3), 2.86–0.75 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.9, 173.9, 171.0, 166.5, 151.1, 145.4, 136.8, 128.2, 127.1, 125.3, 121.9, 121.5, 113.3, 111.5, 109.4, 103.4, 81.5, 55.5, 55.5, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.6, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.9, 29.7, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.2, 25.1, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C51H72N3O6, 822.5421 [M+H+]; found, 822.5447.

4.1.3.4. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(1H-indol-3-yl)acryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13d).

Yield: 49.3 mg (46%), starting from 90 mg of 12d; white amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.82 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.76 (1H, s, CH =), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, Ph-5), 7.51 (2H, s, Ph-3,4), 6.86 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 6.79 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, Ph-2), 4.74 and 4.59 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.49 (1H, dd, J = 6.0, 9.8 Hz, H-3), 3.67 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.98(1H, m, H-19), 2.67 and 2.57 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30), 1.31 and 1.29 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.97 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.84 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 2.86–0.75 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.2, 173.9, 171.3, 166.0, 155.8, 151.1, 146.0, 144.0, 130.2, 128.0, 121.4, 120.1, 115.3, 111.8, 109.3, 106.7, 81.4, 55.5, 55.5, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.9, 45.7, 44.6, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.9, 38.8, 37.2, 37.0, 36.0, 34.4, 32.6, 31.3, 29.9, 27.9, 27.9, 27.4, 25.6, 25.6, 25.6, 21.2, 19.7, 18.3, 16.2, 16.1, 15.3, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C51H72N3O6, 822.5421 [M+H+]; found, 822.5476.

4.1.3.5. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(2,3-dihydrobenzo[b] [1,4]dioxin-6-yl) acryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13g).

Yield: 59.5 mg (53%), starting from 95 mg of 12g; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.57 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.03–7.00 (2H, overlap, Ph-2,6), 6.84 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ph-5), 6.69 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 4.71 and 4.57 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.47 (1H, dd, J = 6.4, 10.0 Hz, H-3), 4.26 (4H, brs, -O-CH2-CH2-O-), 3.63 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.96 (1H, m, H-19), 2.64 and 2.55 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.67 (3H, s, H-30), 1.28 and 1.27 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.91 (3H, s, CH3), 0.81 (3H, s, CH3), 0.81 (3H, s, CH3), 0.78 (3H, s, CH3), 2.84–0.73 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 180.9, 173.9, 171.1, 166.0, 151.1, 145.3, 143.7, 143.1, 128.7, 121.8, 117.6, 116.4, 114.6, 109.4, 81.6, 64.5, 64.3, 55.6, 55.6, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.7, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.8, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.8, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.1, 23.7, 21.2, 19.6, 18.9, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C51H73N2O8, 841.5367 [M+H+]; found, 841.5393.

4.1.3.6. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(2,3-dihydrobenzofuran-5-yl)acryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13h).

Yield: 33.2 mg (38%), starting from 73.5 mg of 12h; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.64 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.38 (1H, s, Ph-2), 7.29 (1H, dd, J = 1.2, 8.0 Hz, Ph-6), 6.76 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ph-5), 6.68 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 4.71 and 4.57 (1H each, 2d, J = 2.0 Hz, H-29), 4.60 (2H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, OCH2), 4.45 (1H, dd, J = 6.4, 9.6 Hz, H-3), 3.64 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 3.20 (2H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, CH2), 2.96 (1H, m, H-19), 2.62 and 2.54 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.67 (3H, s, H-30), 1.26 and 1.25 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.91 (3H, s, CH3), 0.81 (3H, s, CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 0.78 (3H, s, CH3), 2.83–0.72 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ181.7, 173.9, 171.4, 166.2, 161.9, 151.1, 143.8, 129.0, 127.9, 127.9, 124.4, 113.2, 109.6, 109.4, 81.5, 71.8, 55.5, 55.5, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.8, 41.9, 40.7, 40.6, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.9, 29.3, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.3, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C51H73N2O7, 825.5418 [M+H+]; found, 825.5388.

4.1.3. 7. (E)-4-(28-(4-(3-(ben zo[d] [1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-methylacryloyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13k).

Yield: 43.3 mg (47%), starting from 82.4 mg of 12k; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.84–6.78 (3H, overlap, Ph-2,5,6), 6.56 (1H, s, CH =), 5.98 (2H, s, O-CH2-O), 4.73 and 4.59 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.48 (1H, dd, J = 6.4, 10.2 Hz, H-3), 3.63 (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.97 (1H, m, H-19), 2.66 and 2.56 (1H each, d, J = 15.2 Hz, H-2′), 2.10 (3H, s, CH3), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30), 1.30 and 1.28 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.93 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (6H, s, CH3 × 2), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 2.84–0.75 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 182.0, 173.9, 172.9, 171.0, 151.0, 147.7, 147.1, 130.9, 130.3, 129.7, 123.3, 109.0, 108.3, 108.3, 101.2, 81.5, 55.5, 55.5, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.6, 44.7, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.8, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.0, 23.6, 21.1, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.3, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C51H73N2O8, 841.5367 [M+H+]; found, 841.5398.

4.1.3.8. 4-(28-(4-(3-(Benzo[d] [1,3]dioxol-5-yl)propanoyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3b-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13m).

Yield: 50.2 mg (51%), starting from 84.0 mg of 12m; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.72 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, Ph-5), 6.70 (1H, d, J = 1.6 Hz, Ph-2), 6.65 (1H, dd, J = 1.6, 7.6 Hz, Ph-6), 5.91 (2H, s, O-CH2-O), 4.72 and 4.58 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.48 (1H, dd, J = 5.6, 9.2 Hz, H-3), 3.57–3.35 (8H, overlap, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.95 (1H, m, H-19), 2.89 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, Ph-CH2), 2.68–2.53 (4H, overlap, 2 × H-2′, COCH2), 1.67 (3H, s, H-30), 1.29 and 1.28 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.95 (3H, s, CH3), 0.91 (3H, s, CH3), 0.82 (6H, s, CH3 × 2), 0.77 (3H, s, CH3), 2.82–0.75 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 182.1, 174.0, 171.6, 171.1, 151.0, 147.7, 145.0, 135.7, 128.8, 112.7, 109.4, 108.3, 101.2, 81.5, 55.5, 55.5, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.6, 44.7, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 33.9, 32.6, 32.1, 31.3, 29.8, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.0, 23.6, 21.1, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C50H73N2O8, 829.5367 [M+H+]; found, 829.5407.

4.1.3.9. 4-(28-(4-(6-(Benzylamino)pyrimidin-4-yl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13n).

Yield: 43.2 mg (37%), starting from 94.5 mg of 12n; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.99 (1H, s, pyrimidine-2H), 7.36–7.26 (5H, overlap, Ph-2,3,4,5,6), 5.23 (1H, s, pyrimidine-5H), 4.72 and 4.58 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.46 (1H, dd, J = 5.2, 11Hz, H-3), 4.40 and 4.30 (1H each, 2s, -NH-CH2-Ph), 3.67= (8H, brs, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.97 (1H, m, H-19), 2.62 and 2.42 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.68 (3H, s, H-30), 1.29 and 1.26 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.88 (3H, s, CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 0.77 (3H, s, CH3), 0.76 (3H, s, CH3), 2.85–0.71 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 182.0, 174.0, 172.0, 171.0, 163.5, 162.6, 151.0, 141.2, 128.2, 128.2, 126.7, 126.1, 126.1, 109.3, 88.6, 81.6, 54.7, 52.7, 52.1, 52.1, 51.8, 51.8, 50.7, 46.7, 45.7, 44.7, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.8, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.1, 23.6, 21.1, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C51H72N5O5, 834.5534 [M−H+]; found, 834.5569.

4.1.3.10. 4-(28-(4-(4-oxo-4-(thiazol-2-ylamino)butanoyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (13o).

Yield: 18.1 mg (44%), starting from 35.2 mg of 12o; white amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.51 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, CH =), 6.96 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, CH =), 4.73 and 4.59 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.47 (1H, dd, J = 6.8, 9.2 Hz, H-3), 3.67–3.51 (8H, overlap, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.98 (1H, m, H-19), 2.94 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, COCH2), 2.83 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, COCH2), 2.63 and 2.41 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30), 1.28 and 1.27 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.85 (3H, s, CH3), 0.84 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 2.81–0.78 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.9, 174.0, 173.1, 171.1, 166.7, 164.0, 151.0, 133.3, 111.6, 109.4, 81.5, 55.6, 55.6, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.7, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 38.4, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.7, 31.3, 29.8, 29.8, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.0, 23.6, 21.1, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C47H71N4O7S, 835.5043 [M+H+]; found, 835.5014.

4.1.4. General procedures for the synthesis of 20a–20d and 21

Compounds 14 and 15 were prepared according to the literature methods [18,29]. Starting from 1, intermediates 16, 17, 18a–18d, and 19 were synthesized according to the methods described in literatures [18,22]. Products 20a–20d and 21 were obtained using the same procedure described above for preparation of 4 and 9b–9v.

4.1.4.1. 4-(28-((3-(Thiazol-2-ylamino)propoxy)carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (20c).

Yield: 21.9 mg (20%), starting from 88.8 mg of 18c; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.05 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, CH =), 6.43 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, =CH), 4.74 and 4.61 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.48 (1H, dd, J = 4.8, 10.6 Hz, H-3), 4.18 (2H, t, J = 4.6 Hz, OCH2), 3.30 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2-NH), 3.02 (1H, m, H-19), 2.62 and 2.57 (1H each, d, J =16.0 Hz, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30),1.31 and 1.29 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.88 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 0.79 (3H, s, CH3), 0.78 (3H, s, CH3), 2.27–0.75 (26H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton or carbon chain). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 182.0, 175.3, 171.1, 164.2, 151.0, 136.4, 111.8, 109.4, 81.5, 61.8, 56.7, 55.5, 50.7, 49.4, 47.2, 44.7, 42.5, 40.9, 40.8, 40.4, 38.4, 38.3, 37.7, 37.1, 37.0, 34.3, 32.3, 30.7, 29.8, 29.7, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 23.6, 21.3, 19.4, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C42H65N2O6S, 725.4563 [M+H+]; found, 725.4529.

4.1.5. General procedures for the synthesis of 28 and 29

Compounds 22–27 were synthesized using the reported methods [18,22]. Products 28 and 29 were obtained from 26 and 27 respectively, using the same procedures described above to synthesize 4 and 9b–9v.

4.1.5.1. (E)-4-(28-((2-(4-(3-(benzo[d] [1,3]dioxol-5-yl)acryloyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (28).

Yield: 55.2 mg (54%), starting from 86.0 mg of 26; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.45 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 6.99 (1H, s, 2-Ph), 6.94 (1H, d, J 7.8 Hz, 6-Ph), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, 5-Ph), 6.23 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 5.95 (2H, s, O-CH2-O), 4.69 and 4.55 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.42= (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, H-3), 3.60 (2H, m, 28-CONH-CH2CH2-NH-), 3.34 (2H, m, 28-CONH-CH2CH2-NH-), 3.03 (1H, m, H-19), 2.65 and 2.52 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.64 (3H, s, H-30), 1.30 and 1.27 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.87 (3H, s, CH3), 0.84 (3H, s, CH3), 0.81 (6H, s, CH3), 0.73 (3H, s, CH3), 0.70 (3H, s, CH3), 2.43–0.64 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.9, 175.8, 171.1, 166.9, 151.1, 149.3, 148.2, 142.1, 129.4, 124.3, 119.7, 109.4, 108.5, 106.5, 101.8, 81.6, 54.7, 52.7, 50.8, 47.7, 44.7, 41.9, 40.7, 40.4, 39.6, 38.9, 38.4, 37.8, 37.1, 37.0, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.8, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 25.0, 23.6, 21.1, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C48H69N2O8, 801.5054 [M+H+]; found, 801.5092.

4.1.5.2. (E)-4-(28-((3-(4-(3-(benzo[d] [1,3]dioxol-5-yl)acryloyl) piperazin-1-yl)propyl)carbamoyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (29).

Yield: 53.4 mg (51%), starting from 88.3 mg of 27; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.53 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.01 (1H, s, 2-Ph), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, 6-Ph), 6.78 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, 5-Ph), 6.29 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, CH =), 5.97 (2H, s, O-CH2-O), 4.73 and 4.58 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.46 (1H, dd, J = 10.6, 6.0 Hz, H-3), 3.48–3.21 (4H, overlap, 28-COCH2CH2CH2NH-CO), 3.11 (1H, m, H-19), 2.65 and 2.54 (1H each, d, J = 15.2 Hz, H-2′), 1.67 (3H, s, H-30), 1.28 and 1.26 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.89 (3H, s, CH3), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 0.78 (3H, s, CH3), 0.76 (3H, s, CH3), 2.49– 0.72 (26H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton or carbon chain). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.9, 175.4, 171.0, 151.1, 149.2, 148.2, 142.3, 129.4, 124.1, 119.3, 116.7, 109.4, 108.4, 106.1, 101.2, 81.5, 61.9, 56.7, 55.5, 50.7, 49.4, 47.2, 44.7, 42.5, 40.8, 40.4, 38.4, 38.3, 37.7, 37.1, 36.9, 36.8, 34.3, 32.3, 30.7, 29.7, 28.8, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.6, 23.7, 21.3, 19.4, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C49H70NO9, 816.5050 [M+H+]; found, 816.5023.

4.1.6. General procedures for the synthesis of 31 and 32

Starting from 30, synthesized following the reported methods [18], products 31 and 32 were prepared using the methods described in our previous study [22].

4.1.6.1. 4-(28-(4-(5-(4-(6-(Benzylamino)pyrimidin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-5-oxopentyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (32).

Yield: 43.0 mg (27%), starting from 100 mg of 30; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.13 (1H, s, pyrimidine-2H), 7.37–7.26 (5H, overlap, Ph-2,3,4,5,6), 5.30 (1H, s, pyrimidine-5H), 4.72 and 4.58 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.49 (1H, dd, J = 4.8, 10.4 Hz, H-3), 4.45 and 4.44 (1H each, 2s, -NH-CH2-Ph), 3.68 to 3.42 (12H, overlap, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N- and CON(CH2CH2)2-pyrimidine), 2.97 (1H, m, H-19), 2.74 and 2.42 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.68 (3H, s, H-30), 1.29 and 1.26 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.92 (3H, s, CH3), 0.88 (3H, s, CH3), 0.79 (6H, s, 2 × CH3), 2.88–0.73 (36H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton or carbon chain). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.9, 173.7, 173.2, 172.3, 171.1, 163.6, 162.7, 151.0, 141.2, 128.4, 128.4, 126.9, 126.2, 126.2, 109.4, 88.6, 81.5, 57.8, 57.8, 57.8, 54.7, 52.8, 52.8, 52.7, 51.8, 51.8, 51.1, 51.1, 50.7, 46.8, 45.7, 44.6, 41.9, 40.6, 40.4, 38.4, 38.0, 37.8, 37.3, 36.8, 34.2, 32.8, 32.1, 31.3, 29.7, 27.9, 27.9, 25.6, 25.5, 25.5, 25.4, 23.7, 23.1, 21.2, 19.7, 18.4, 16.7, 16.3, 16.0, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C60H88N7O6, 1002.6796 [M−H+]; found, 1002.6757.

4.1.7. Synthesis of (E)-4-(28-((4-(3-(benzo[d] [1,3]dioxol-5-yl) acryloyl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)lup-20(29)-en-3b-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (37)

Starting from betulin (2), intermediates 33, 34, 35 and 36 were prepared using the methods reported in the literature [18,22]. Conversion of 36 to product 37 was accomplished using the methods described above to synthesize 4 and 9b-v.

Compound 37.

Yield: 29.0 mg (44%), starting from 55.7 mg of 36; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.64 (1H, d, J 15.6 Hz, CH =), 7.04 (1H, s, 2-Ph), 7.02 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, 6-Ph), 6.81 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, 5-Ph), 6.67 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, CH =), 6.01 (2H, s, O-CH2-O), 4.70 and 4.61 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.50 (1H, t, J = 9.6 Hz, H-3), 3.74–3.67 (8H, overlap, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 3.49 and 3.48 (1H each, d, J = 5.6 Hz, H-28), 2.97 (1H, m, H-19), 2.63 and 2.56 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30), 1.28 and 1.26 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.98 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.84 (6H, s, CH3 × 2), 0.81 (3H, s, CH3), 2.45–0.76 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.7, 171.1, 162.8, 149.7, 149.1, 148.3, 143.9, 129.2, 124.2, 117.1, 110.2, 108.6, 106.4, 101.5, 81.5, 58.9, 56.0, 55.4, 55.4, 52.1, 51.5, 51.5, 50.2, 46.6, 44.7, 43.8, 42.7, 40.9, 38.4, 37.7, 37.0, 29.7, 27.9, 27.9, 25.4, 25.4, 25.3, 25.1, 24.0, 23.6, 20.8, 19.7, 19.1, 18.1, 16.5, 16.1, 16.0, 14.8, 14.1, 13.6. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C50H73N2O7, 813.5418 [M+H+]; found, 813.5399.

4.1.8. Synthesis of (E)-28-nor-4-(17-(4-(3-(benzo[d] [1,3]dioxol-5-yl)acryloyl)piperazin-1-yl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (41)

Starting from betulin (2), intermediates 38, 39, and 40 were prepared using the methods reported in the literature [34]. Product 41 was synthesized from 40 using the methods described above to synthesize 4 and 9b-v.

Compound 41.

Yield: 43.2 mg (46%), starting from 77.0 mg of 40; white amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.50 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 7.03 (1H, s, 2-Ph), 7.00 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, 6-Ph), 6.79 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, 5-Ph), 6.27 (1H, d, J = 15.2 Hz, CH =), 5.99 (2H, s, O-CH2-O), 4.74 and 4.64 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.48 (1H, dd, J = 4.6, 11.0 Hz, H-3), 2.80 (1H, m, H-19), 2.67 and 2.56 (1H each, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-2′), 1.71 (3H, s, H-30), 1.28 and 1.26 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 1.00 (3H, s, CH3), 0.98 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (6H, s, CH3 × 2), 0.80 (3H, s, CH3), 2.48–0.76 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.9, 171.0, 166.1, 151.1, 149.4, 148.5, 142.0, 129.6, 124.2, 119.5, 109.4, 108.1, 106.5, 81.5, 56.8, 55.5, 53.4, 50.6, 50.1, 44.7, 44.1, 42.5, 40.4, 40.4, 38.4, 38.1, 37.8, 37.7, 37.1, 34.3, 33.1, 30.9, 29.5, 28.0, 25.6, 25.6, 25.6, 23.7, 21.0, 19.5, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 14.6. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C45H64NO7, 730.4683 [M+H+]; found 730.4657.

4.1.9. General Procedures for the synthesis of (E)-3β-((3-(benzo[d] [1,3]dioxol-5-yl)acryloyl)oxy)-lup-20(29)-en-28 oic acid (42a) and (E)-3b-((3-(3,4-bis(methoxymethoxy)phenyl)acryloyl)oxy)-lup-20(29)-en-28 oic acid (42b)

The appropriate acids were prepared using previously described methods [27] or purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or other commercial sources. BA (1) (1 equiv), the appropriate 3,4-substituted cinnamic acid (5.0 equiv), and Et3N (1.1 eq) were dissolved in anhydrous DCM. To the solution, EDCI (5equiv) and DMAP (1 eq) were added. The reaction was stirred overnight until all starting material was consumed. The solution was then diluted with DCM and washed twice with brine. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was chromatographed using a silica gel column to give the pure products.

4.1.10. General Procedures for the synthesis of tert-butyl (E)-4-((3β-(3-(benzo[d] [1,3]dioxol-5-yl)acryloyl)oxy)lup-20(29)-en-28-carbonyl)-piperazine-1-carboxylate (43a) and tert-butyl (E)-4-((3β-(3-(3,4-bis(methoxymethoxy)phenyl)acryloyl)oxy)lup-20(29)-en-28-carbonyl)-piperazine-1-carboxylate (43b)

Compounds 43a and 43b were prepared as previously described [22]. In brief, oxalyl chloride solution (2 M in DCM) was added to the appropriate triterpenoid (1 equiv) in DCM. The mixture was stirred for 2 h. After removal of solvent under vacuum, the residue was treated with 1-Boc-piperazine (1.5 equiv) and Et3N (15 equiv) in anhydrous DCM. The mixture was stirred overnight at rt until all starting material was consumed. The solution was then diluted with DCM and washed twice with brine. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The residue was chromatographed using a silica gel column to yield the pure products.

4.1.11. General Procedures for the synthesis of (E)-4-((4-(3β-((3-(benzo[d] [1,3]dioxol-5-yl)acryloyl)oxy)lup-20(29)-en-28-carbonyl) piperazine-1-carbonyl)oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (44a) and (E)-4-((4-(3β-((3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)acryloyl)oxy)lup-20(29)-en-28-carbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (44b)

To a solution of the appropriate 43a or 43b (1 equiv) in DCM was added 4 N HCl in EtOAc (22 equiv). The mixture was stirred for 4 h at rt. After removal of solvent under vacuum, the residue was dissolved in anhydrous pyridine. To the solution, 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride (5 equiv), and DMAP (1 equiv) were added. The mixture was then reacted at 155 °C for 2 h in a microwave oven (Biotage). The reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc, neutralized with HCl (1 N), and then extracted twice with EtOAc. The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo to afford the crude product, which was chromatographed on a silica gel column to yield the pure products 44a and 44b.

4.1.12. Synthesis of compound 4-((4-(3β-acetoxy-lup-20(29)-en-28-carbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (45)

To a solution of 6 (400 mg, 0.58 mmol) in DCM (7 mL), TFA (0.44 mL, 5.76 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at rt until all starting material was consumed. The solvent was removed under vacuum. The residue was treated with 2,2-dimethylsuccinic anhydride (369 mg, 2.88 mmol) and DMAP (70.4 mg, 0.58 mmol) in anhydrous pyridine. The mixture was then reacted at 155 °C for 2 h in a microwave oven (Biotage). The reaction was diluted with EtOAc, neutralized with HCl (1 N), and then extracted twice with EtOAc. The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give the crude product, which was chromatographed on a silica gel column to give 323.2 mg of 45 (77%), white amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 4.73 and 4.59 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.48 (1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, H-3), 3.69–3.45 (8H, overlap, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.96 (1H, m, H-19), 2.63 (2H, s, H-2′), 2.04 (3H, s, OAc), 1.68 (3H, s, H-30), 1.31 (6H, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.96 (3H, s, CH3), 0.93 (3H, s, CH3), 0.85 (3H, s, CH3), 0.84 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 2.84–0.77 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton or carbon chain). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.0, 173.9, 171.0, 169.9, 151.0, 109.4, 81.0, 55.5, 55.5, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 42.8, 41.9, 40.7, 40.6, 38.4, 37.8, 37.2, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.8, 27.9, 25.9, 25.9, 25.6, 25.4, 23.7, 21.3, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.3, 16.1, 14.6. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C42H65N2O6, 693.4843 [M−H+]; found, 693.4869.

4.1.13. Synthesis of compound 4-((4-(3β-hydroxylup-20(29)-en-28-carbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (46)

To the solution of 45 (120 mg, 0.17 mmol) in MeOH (1 mL) and THF (2 mL) was added 4 N NaOH (1 mL). The reaction was stirred overnight, neutralized with 1 N HCl, and extracted three times with DCM. The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated. The residue was chromatographed using a silica gel column to yield 95.3 mg of 46 (85%), white amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 4.69 and 4.58 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 3.66–3.58 (8H, overlap, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 3.13 (1H, dd, J = 5.2, 10.8 Hz, H-3), 2.92 (1H, m, H-19), 2.65 (2H, s, H-2′), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30),1.32 (6H, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 1.00 (3H, s, CH3), 0.95 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (3H, s, CH3), 0.86 (3H, s, CH3), 0.75 (3H, s, CH3), 2.84–0.69 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton or carbon chain). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.1, 174.0, 171.1, 151.1, 109.4, 79.0, 55.5, 55.5, 55.3, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 42.6, 41.9, 40.7, 40.6, 38.9, 38.4, 37.2, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.8, 27.5, 27.4, 25.9, 25.9, 25.5, 23.7, 21.3, 19.6, 18.3, 16.5, 16.3, 16.1, 14.6. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C40H63N2O5, 651.4737 [M−H+]; found, 651.4755.

4.1.14. Synthesis of compound 4-((4-(3β-((3-carboxy-3-methylbutanoyl)oxy)lup-20(29)-en-28-carbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (47)

The above method for synthesizing 4 and 9b–9v was used to prepare 33 mg of 47 (42%) from 65 mg of 46; colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 4.73and 4.60 (1H each, 2s, H-29), 4.48 (1H, d, J = 6.8, 10.8 Hz, H-3), 3.67–3.45 (8H, overlap, 28-CON(CH2CH2)2-N-), 2.97 (1H, m, H-19), 2.64 to 2.59 (4H, overlap, H-2′, H-2”), 1.69 (3H, s, H-30), 1.31 (6H, s, 2 CH3-3”), 1.30 and 1.28 (3H each, s, 2 × CH3-3′), 0.97 (3H, s, CH3), 0.93 (3H, s, CH3), 0.84 (3H, s, CH3), 0.83 (3H, s, CH3), 0.81 (3H, s, CH3), 2.87–0.76 (24H, m, CH, CH2 in pentacyclic skeleton or carbon chain). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 182.2, 181.8, 173.9, 171.2, 169.9, 151.1, 109.4, 81.5, 55.6, 55.6, 54.7, 54.7, 54.7, 52.7, 50.7, 45.7, 44.8, 42.9, 41.9, 41.7, 40.7, 40.5, 38.4, 37.8, 37.1, 36.9, 36.0, 34.3, 32.6, 31.3, 29.9, 27.9, 26.0, 25.8, 25.6, 25.6, 25.3, 25.2, 23.6, 21.2, 19.6, 18.2, 16.5, 16.2, 16.1, 14.7. HRMS (ESI, m/z) calcd for C46H71N2O8, 779.5211 [M−H+]; found 779.5237.

4.1.15. Synthesis of compound 4-(28-(piperazine-1-carbonyl)lup-20(29)-en-3β-oxy)-2,2-dimethyl-4-oxobutanoic acid (48)

The detailed procedure for the synthesis of 48 can be found in our prior research publication [22].

4.2. HIV-1/NL4–3 replication inhibition assay in MT-4 lymphocytes

A previously described HIV-1 infectivity assay was used [18,22]. Briefly, a 96-well microtiter plate was used to set up the HIV-1/NL4–3 replication screening assay. MT4 cells were infected with NL4–3 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. Culture supernatants were collected on day 4 PI for the p24 antigen capture using an ELISA kit from ZeptoMetrix Corporation (Buffalo, NY). The 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) was defined as the concentration that inhibits HIV-1/NL4–3 replication by 50%.

4.3. Cytotoxicity assay

A CytoTox-Glo cytotoxicity assay (Promega) was used to determine the cytotoxicity of the synthesized derivatives. Mock-infected MT-4 cells were cultured in the presence of various concentrations of the compounds for 2 days. Percent of viable cells was determined by following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) was defined as the concentration that caused a 50% reduction of cell viability.

4.4. 3D QSAR model

The 3D QSAR model was performed in the create 3D QSAR module of DS 3.5. All structures were prepared by the standard protocols in the small molecule module of DS 3.5. The inhibitory activity was converted to the −Log IC50 value and used as a dependent variable for the QSAR analyses. The CHARMm force field was used. The van der Waals potential and the electrostatic potential were considered as separate terms. A+1e point charge was employed as the electrostatic potential probe. Regarding the van der Waals potential, a carbon atom with 1.73 Å radius served as probe. The grid space was set as 1.5 Å. A partial Least-Square (PLS) model was built with energy grids as descriptors. Full cross validated Partial Least-Squares (PLS) method of LOO (leave one out) was employed for the regression analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support was supplied by NIH Grant AI33066 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K.-H. Lee).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113287.

References

- [1].http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. (Accessed 15 October 2020) accessed on.

- [2].Taiwo B, Hicks C, Eron J, Unmet therapeutic needs in the new era of combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 65 (2010) 1100–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhan P, Pannecouque C, De Clercq E, Liu X, Anti-HIV drug discovery and development: current innovations and future trends, J. Med. Chem 59 (2016) 2849–2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Xiao Z, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH, Strategies for the optimization of natural lead to anticancer drugs or drug candidates, Med. Res. Rev 36 (2016) 32–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Guo Z, The modification of natural products for medical use, Acta Pharm. Sin. B 7 (2017) 119–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yao H, Liu J, Xu S, Zhu Z, Xu J, The structural modification of natural products for novel drug discovery, Expet Opin. Drug Discov 12 (2017) 121–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fujioka T, Kashiwada Y, Kilkuskie RE, Cosentino LM, Ballas LM, Jiang JB, Janzen WP, Chen I-S, Lee K-H, Anti-AIDS agents, 11. Betulinic acid and platanic acid as anti-HIV principles from Syzigium claviflorum, and the anti-HIV activity of structurally related triterpenoids, J. Nat. Prod 57 (1994) 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kashiwada Y, Hashimoto F, Cosentino LM, Chen C-H, Garrett PE, Lee K-H, Betulinic acid and dihydrobetulinic acid derivatives as potent anti-HIV agents1, J. Med. Chem 39 (1996) 1016–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Li F, Goila-Gaur R, Salzwedel K, Kilgore NR, Reddick M, Matallana C, Castillo A, Zoumplis D, Martin DE, Orenstein JM, Allaway GP, Freed EO, Wild CT, PA-457: a potent HIV inhibitor that disrupts core condensation by targeting a late step in Gag processing, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am 100 (2003) 13555–13560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kanamoto T, Kashiwada Y, Kanbara K, Gotoh K, Yoshimori M, Goto T, Sano K, Nakashima H, Anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity of YK-FH312 (a betulinic acid derivative), a novel compound blocking viral maturation, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 45 (2001) 1225–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee K-H, Discovery and development of natural product-derived chemo-therapeutic agents based on a medicinal chemistry approach, J. Nat. Prod 73 (2010) 500–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Smith PF, Ogundele A, Forrest A, Wilton J, Salzwedel K, Doto J, Allaway GP, Martin DE, Phase I and II study of the safety, virologic effect, and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of single-dose 3-O-(3’,3’-dimethylsuccinyl)betulinic acid (bevirimat) against human immunodeficiency virus infection, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 51 (2007) 3574–3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Martin D, Blum R, Doto J, Galbraith H, Ballow C, Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of bevirimat, a novel inhibitor of HIV maturation, in healthy volunteers, Clin. Pharmacokinet 46 (2007) 589–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Martin DE, Blum R, Wilton J, Doto J, Galbraith H, Burgess GL, Smith PC, Ballow C, Safety and pharmacokinetics of bevirimat (PA-457), a novel inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus maturation, in healthy volunteers, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 51 (2007) 3063–3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Adamson CS, Sakalian M, Salzwedel K, Freed EO, Polymorphisms in Gag spacer peptide 1 confer varying levels of resistance to the HIV-1 maturation inhibitor bevirimat, Retrovirology 7 (2010) 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Acob J, Richards J, Augustine JG, Milea JS, Liquid Bevirimat Dosage Forms for Oral Administration, 2009. WO 2009/042166 A1.