Abstract

Background

Targeting multiple key antigens that mediate distinct Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion pathways is an attractive approach for the development of blood-stage malaria vaccines. However, the challenge is to identify antigen cocktails that elicit potent strain-transcending parasite-neutralizing antibodies efficacious at low immunoglobulin G concentrations feasible to achieve through vaccination. Previous reports have screened inhibitory antibodies primarily against well adapted laboratory parasite clones. However, validation of the parasite-neutralizing efficacy against clinical isolates with minimal in vitro cultivation is equally significant to better ascertain their prospective in vivo potency.

Methods

We evaluated the parasite-neutralizing activity of different antibodies individually and in combinations against laboratory adapted clones and clinical isolates. Clinical isolates were collected from Central India and Mozambique, Africa, and characterized for their invasion properties and genetic diversity of invasion ligands.

Results

In our portfolio, we evaluated 25 triple antibody combinations and identified the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination to elicit maximal parasite neutralization against P. falciparum clinical isolates with variable properties that underwent minimal in vitro cultivation.

Conclusions

The MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 combination exhibited highly robust parasite neutralization against P. falciparum clones and clinical isolates, thus substantiating them as promising candidate antigens and establishing a proof of principle for the development of a combinatorial P. falciparum blood-stage malaria vaccine.

Keywords: blood-stage, erythrocyte invasion, malaria vaccine, neutralizing antibodies, Plasmodium falciparum

Our study has identified an antigen combination that elicits potent strain-transcending parasite-neutralizing antibodies that efficaciously inhibit worldwide P falciparum strains through distinct mechanisms and establishes a proof of concept for the development of a combinatorial blood-stage malaria vaccine.

Plasmodium falciparum is primarily responsible for most worldwide malaria mortality [1]. The clinical symptoms and pathology of malaria are associated with the blood stages of the parasite life cycle, which involves a crucial and complex multistep process of erythrocyte invasion mediated by diverse ligand-receptor interactions [2–4]. Erythrocyte invasion is considered an attractive target for malaria vaccine development [5, 6]. Blood-stage malaria vaccines are advantageous because they could reduce parasite densities, prevent onset of clinical malaria, and potentially affect transmission [7]. However, several leading blood-stage candidates have failed to elicit optimal protection in human trials [8, 9], owing to antigenic diversity and probably even redundant P. falciparum erythrocyte invasion pathways.

Antibody-mediated blockade of erythrocyte invasion has produced potent parasite neutralization [10–13]. However, the key challenge is the identification of essential, conserved target antigens that induce potent cross-strain parasite-neutralizing antibodies [5, 6]. Merozoite surface proteins (MSPs) and reticulocyte binding-like homologous (RH) proteins play a critical role in P. falciparum erythrocyte invasion [2–4]. Merozoite surface protein-1 is an essential protein that mediates initial attachment of the parasite to the erythrocyte membrane [2–4]. Although, full-length MSP-1 is highly polymorphic, a C-terminal processed fragment, MSP-119, is highly conserved and elicits potent invasion-inhibitory antibodies [14]. More importantly, naturally acquired human antibodies targeting MSP-119 are associated with protection [15]. Due to its small size, recombinant MSP-119 is poorly immunogenic [16]. A fusion chimera, MSP-Fu, comprising the conserved, immunodominant N-terminal region of MSP-3 linked with the C-terminal MSP-119 [17, 18] has been reported. MSP-3 is a conserved protein member of the MSP family that mediates parasite neutralization through the mechanism of monocyte-mediated antibody-dependent cellular inhibition (ADCI) and considered a promising vaccine target [19]. MSP-Fu exhibited high immunogenicity and induced antibodies with potent invasion inhibitory and ADCI activity [18, 20].

The RH protein family (RH1, RH2, RH4, RH5) function downstream of the MSPs, exhibit limited polymorphism and primarily define the invasion phenotype of P. falciparum strains [2–4, 21–27]. RH5, a leading blood-stage vaccine candidate, is the only indispensable member that plays an essential role in erythrocyte invasion [25, 26] and elicits potent parasite-neutralizing antibodies [11, 12, 28]. RH5-based vaccines have elicited protection in monkey models and induced parasite-neutralizing antibodies in humans [29, 30]. We have demonstrated that RH5 exists on the merozoite surface as part of an essential multiprotein invasion complex [31] along with Ripr [32] and CyRPA [33], which were further confirmed by conditional knockouts [34] and protein interaction studies [35]. RH5/Ripr/CyRPA complex formation is crucial for erythrocyte invasion of which CyRPA is an essential protein that could not be genetically disrupted [31, 34]. CyRPA antibodies exhibited potent parasite neutralization [31, 33, 36] further substantiating its promise as a blood-stage vaccine target. More importantly, anti-CyRPA antibodies have been shown to be associated with a reduced risk to malaria during natural infections [37].

Antibody combinations targeting multiple blood-stage ligand-receptor interactions exhibit additive or synergistic invasion inhibition [10, 11, 13, 31, 38]. A correlation was observed between the invasion inhibitory activity of antibodies combined in vitro with those elicited against coimmunized antigen mixtures [10, 11]. However, an evaluation of antibodies targeting MSPs and key ligand-receptor interactions mechanistically involved in erythrocyte invasion has been lacking, and it would be important to assess the effect of simultaneously blocking these different mechanisms on parasite neutralization. The emergence of MSP-Fu and CyRPA as promising vaccine targets warrants a comprehensive analysis of the parasite-neutralizing potential of antibody combinations based on these antigens that could identify a potent multicomponent blood-stage malaria vaccine.

Preclinical evaluation of blood-stage malaria candidate vaccines by in vitro growth inhibitory activity (GIA) has been conducted primarily on laboratory-adapted clones, which have been cultured in vitro for several decades [10, 11, 13, 39]. The GIA assays with laboratory-adapted clones may not be completely predictive in down-selecting vaccine candidates, because the true characteristics of clinical isolates may be distinct with regards to invasion phenotypes and genetic diversity. Laboratory-adapted parasites cultured over decades may have lost some of their in vivo characteristics. Suboptimal efficacy of leading candidate antigens (AMA-1, MSP-142) in human trials was attributed to antigenic diversity [8, 9]. Thus, the evaluation of the parasite-neutralizing activity of our portfolio of antibodies against P. falciparum clinical isolates (India, Mozambique) adapted with minimal in vitro cultivation is of utmost importance and has the potential to significantly advance the preclinical development of new generation blood-stage malaria vaccine candidates. In the current study, our systematic screening has identified the antibody combination of MSP-Fu/CyRPA/RH5 to exhibit potent parasite neutralization, supporting its development as a promising combinatorial blood-stage malaria vaccine.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Ethical Statement

The study protocol for the collection of Indian P. falciparum clinical isolates by informed consent was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of National Institute for Research in Tribal Health (NIRTH), Jabalpur. The study protocol for the collection of Mozambican P. falciparum clinical isolates by informed consent was approved by the National Ethics Review Committee of Mozambique and the Ethics Review Committee of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona. The animal studies were approved by the ethics committees of International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB) and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

Sample Collection and Parasite Culture

Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates were collected from Balaghat district of Madhya Pradesh, India [40] and from Mozambican children (less than 5 years) at the Manhiça District Hospital (Southern Mozambique) [41]. Indian isolates were incubated in in vitro laboratory culture on the day of collection without any cryopreservation. The African isolates were obtained in a cryopreserved form and thawed for in vitro culture adaptation. Parasitized erythrocytes, after separation over Histopaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC), were washed in incomplete Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium and cultured at 2% hematocrit in O+ erythrocytes at 37oC in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 360 µM hypoxanthine, 24 mM HEPES, .5% Albumax II, 24 mM sodium bicarbonate, 10 mM glucose, and 10 µg/mL gentamycin.

Expression of the Recombinant Proteins, IgG Purification and Functional Assays

Recombinant proteins were produced in Escherichia coli and used for generation of specific antibodies in rabbits as described previously [10, 11, 18, 31, 42, 43]. For a detailed description of enzymatic treatment of erythrocytes, erythrocyte invasion assay, genetic polymorphism analyses of invasion ligands, and growth inhibition assay, see Supplementary Methods.

RESULTS

Antibodies Against CyRPA, MSP-Fu, and RH5 Individually and in Combination (MSP-Fu/CyRPA/RH5) Exhibited Maximal Strain-Transcending Invasion Inhibitory Activity

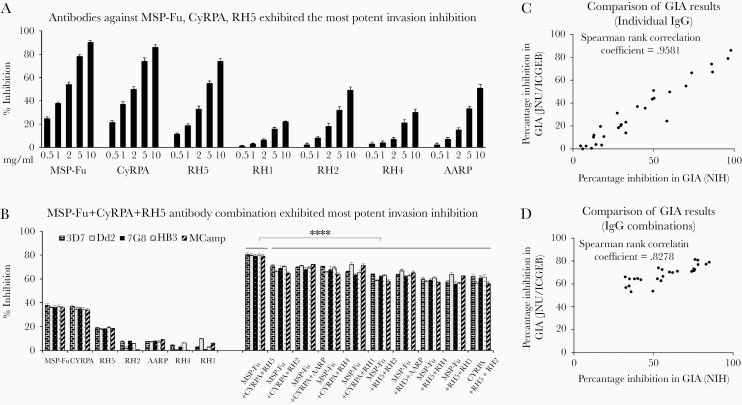

Parasite-neutralizing ability of the individual antibodies was evaluated in standard GIA assays. The different antibodies evaluated at varying total immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentrations in a 1-cycle assay exhibited variable invasion inhibition in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A). Antibodies against MSP-Fu, CyRPA, and RH5 exhibited the most potent invasion inhibition compared with other antibodies of our portfolio (RH1, RH2, RH4, AARP) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Parasite-neutralizing ability of the antibodies individually and in triple combinations in standard growth inhibition assays (GIA). (A) Antibodies against MSP-Fu, CyRPA, RH5 exhibited the most potent invasion inhibition. Antibodies raised against our portfolio of 7 antigens were tested at varying total immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentrations (.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10.0 mg/mL) in a 1-cycle assay against Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 and exhibited a dose-dependent invasion inhibition. Antibodies against CyRPA, MSP-Fu, and RH5 exhibited the most potent invasion inhibition (88%, 77%, and 74%, respectively, at 10 mg/mL) compared with antibodies against the rest of our portfolio of antigens (RH1, RH2, RH4, and AARP). Anti-RH2 IgG and anti-AARP IgG exhibited an inhibition of 48%–51% (10 mg/mL) and 31%–33% (5 mg/mL); anti-RH1 and anti-RH4 IgGs were less potent with an inhibition of 22%–30% (10 mg/mL). (B) MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination exhibited the most potent invasion inhibition. Triple antibody combinations were tested for their GIA activity against 5 worldwide P. falciparum clones. Analysis of the MSP-Fu- and CyRPA-based 10 triple antibody combinations (1.0 mg/mL total IgG each) in 1-cycle assays clearly depict the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination exhibited maximal invasion-inhibitory activity in a strain-transcending manner. MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination inhibited the erythrocyte invasion of the 5 P. falciparum clones with an equal efficiency of 79%–80%, which was significantly more potent than that observed with the other 9 combinations (unpaired Student’s t test: ****P ≤ .0001). Data represent the average of 3 independent experiments conducted in duplicate. The error bars represent the standard error between the 3 independent GIA experiments. (C and D) Comparison of GIA results between National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU)/International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting-based GIA results were confirmed independently for antibodies individually (C) and in combination (D) using the LDH-based invasion assay (GIA Reference Laboratory; Laboratory of Malaria and Vector Research, NIH). Spearman rank correlation coefficient of .9581 and .8278 for the antibodies tested individually (C) and in combination (D), respectively, at NIH and JNU/ICGEB strongly suggest that our invasion inhibition results are consistent between the 2 different assays.

Our objective was to identify antibody combinations from our portfolio of 7 antigens that elicit potent parasite neutralization at the minimal antibody (IgG) concentrations such that these efficacious antibody titers would be feasible to attain through vaccines. Thus, we first systematically evaluated the GIA activity of 25 combinations, each comprising 3 antibodies from our portfolio against the P. falciparum clones 3D7 (Supplementary Figure S1) and Dd2 (Supplementary Figure S2), in 1-cycle and 2-cycle assays. Consistent with the potent invasion inhibitory activity of individual antibodies, the combinations based on MSP-Fu and CyRPA antibodies displayed potent parasite neutralization of which the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination was most efficacious in both 1-cycle and 2-cycle GIA assays.

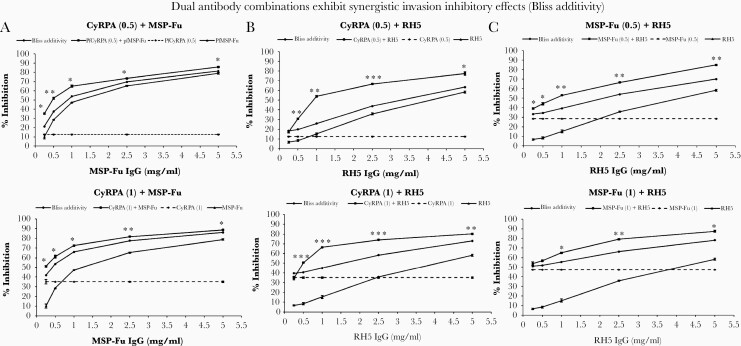

The MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination exhibited the most potent GIA efficacy against 3 more P. falciparum clones: 7G8 (Supplementary Figure S3), HB3 (Supplementary Figure S4), and MCamp (Supplementary Figure S5). More importantly, the 5 clones have different geographical origins and exhibit distinct invasion phenotypes (Figure 1B) against which the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination exhibited maximal GIA activity in a strain-transcending manner (Figure 1B). The results of the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based GIA conducted in the laboratories of ICGEB and JNU were confirmed independently using the Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH)-based GIA at the Reference Laboratory (Laboratory of Malaria and Vector Research, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, Maryland) and were found to be consistent (Figure 1C and D). We further evaluated the additive or synergistic modes of inhibition exhibited by dual antibody combinations from the 3 most potent antibodies against MSP-Fu, CyRPA, and RH5 in 1-cycle (Figure 2) and 2-cycle GIA assays (Supplementary Figure S6). In 1-cycle assays, all the 3 dual antibody combinations—MSP-Fu+CyRPA, MSP-Fu+RH5, and CyRPA+RH5—exhibited synergistic inhibition (Figure 2). However, the synergistic inhibition was less prominent in the MSP-Fu+CyRPA combination, compared with the other 2 dual antibody combinations, which may be attributed to the inherent high potent parasite neutralization exhibited by both individual antibodies (Figure 1A). In 2-cycle assays, the inhibitory effects for MSP-Fu+CyRPA and MSP-Fu+RH5 were additive, whereas that for CyRPA+RH5 remained synergistic (Supplementary Figure S6). Thus, in 2-cycle assays, where all antibodies displayed a higher invasion inhibitory activity, the synergistic effects between antibodies were further diminished.

Figure 2.

Dual antibody combinations exhibit synergistic invasion inhibitory effects (bliss additivity). (A) Fixed concentrations of CyRPA antibodies (.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL total immunoglobulin G [IgG]) in combination with increasing concentrations of MSP-Fu antibodies (.5, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0 mg/mL total IgG) exhibited synergistic inhibition. The dual antibody combinations yielded inhibition that was significantly higher than that predicted by bliss additivity. (B) Fixed concentrations of CyRPA antibodies (.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL total IgG) in combination with increasing concentrations of RH5 antibodies (.5, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0 mg/mL total IgG) exhibited synergistic inhibition. (C) Fixed concentrations of MSP-Fu antibodies (.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL total IgG) in combination with increasing concentrations of RH5 antibodies (.5, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0 mg/mL total IgG) exhibited synergistic invasion inhibitory activity. At the fixed concentration of MSP-Fu antibodies (1.0 mg/mL), the synergy with RH5 antibodies was observed to be concentration dependent and observed at higher concentration of the RH5 IgG. Data represent the average of 2 independent experiments conducted in triplicate. The error bars represent the standard error between the 2 independent GIA experiments. (Unpaired Student’s t test: ***, P ≤ .001; **, P ≤ .01; *, P ≤ .05.).

Plasmodium falciparum Clinical Isolates From Malaria-Endemic Regions of India and Mozambique Exhibit Phenotypic Variation in Erythrocyte Invasion

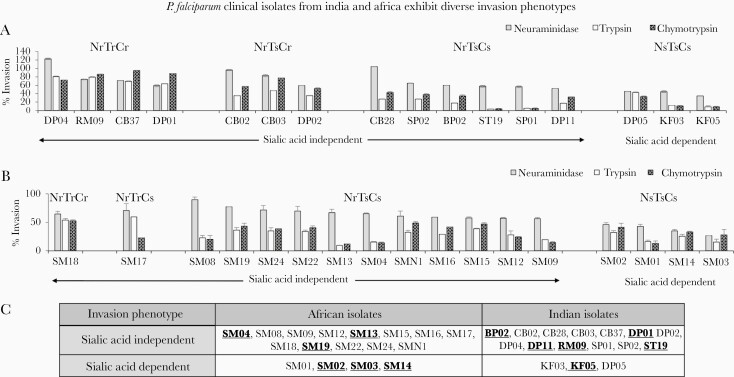

To analyze a wider repertoire of P. falciparum parasites that represent a broader genetic diversity and phenotypic variation in erythrocyte invasion, we evaluated the potency of the (MSP-Fu+RH5+CyRPA) antibodies with clinical isolates from India and Mozambique that were adapted after minimal in vitro culture. The P. falciparum clinical isolates were obtained from 2 malaria-endemic regions: Central India and Mozambique, Africa (Figure 3). In vitro culture adaptation of the clinical isolates (16 of 54 Indian, 17 of 34 Mozambican) was successfully accomplished using media comprising albumax II supplemented with glucose (Results, Supplementary Figure S7). Invasion phenotypes of the 33 clinical isolates were characterized using enzymatically treated erythrocytes (neuraminidase, trypsin, chymotrypsin) in FACS-based invasion assays (Supplementary Figure S8). Based on their dependence to use sialic acid-based receptors as reflected by their sensitivity to invade neuraminidase-treated erythrocytes, the clinical isolates were categorized broadly into 2 invasion phenotype groups: sialic acid independent and sialic acid dependent (Figure 4). The clinical isolates from both endemic regions exhibited a dominant sialic acid-independent invasion (Figure 4). Furthermore, the African and Indian isolates exhibited a variability in their invasion sensitivity to both chymotrypsin and trypsin treatment (Figure 4A and B) that allowed the identification of distinct invasion phenotypes among the sialic acid-independent group (Figure 4A and B). These distinct invasion phenotypes confirmed that the P. falciparum clinical isolates exhibited redundancy in erythrocyte invasion.

Figure 3.

Malaria-endemic field sites for Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolate collection. (A) Balaghat district of the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. (B) Manhica district in South Mozambique, Africa.

Figure 4.

Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates from India and Africa exhibit diverse invasion phenotypes. Invasion pathways of P. falciparum clinical isolates from malaria-endemic regions of Central India (A) and Mozambique, Africa (B) were characterized using a fluorescence-activated cell sorting-based dual color erythrocyte invasion assay that determined the ability of the parasite isolates to invade erythrocytes treated with neuraminidase (25 mU/mL), chymotrypsin (1 mg/mL), and trypsin (1 mg/mL). Invasion rates were determined by flow cytometry after 40–44 hours of incubation and expressed as invasion efficiency relative to invasion of untreated erythrocytes. Sensitivity was defined as more than a 50% decrease in erythrocyte invasion of enzymatically treated erythrocytes compared with untreated controls. The sialic acid-independent phenotype was prominent among the majority of the clinical isolates from both India (13 of 16 isolates) (A) and Africa (13 of 17 isolates) (B). Based on sensitivity to trypsin and chymotrypsin treatment, 5 distinct invasion phenotypes were observed [Nm(r)T(r)C(r), Nm(r)T(r)C(s), Nm(r)T(s)C(r), Nm(r)T(s)C(s), Nm(s)T(s)C(s)]. The clinical isolates from each location are arranged on a scale starting from the completely resistant [Nm(r)T(r)C(r)] parasite strains (DP04, SM18) to the ones sensitive to all enzymes (KF05, SM03). (C) The table depicts the broad classification of clinical isolates into sialic acid-independent and -dependent phenotypes, as reflected by their sensitivity to invade neuraminidase-treated erythrocytes. Clinical isolates selected for evaluation of invasion inhibitory antibodies highlighted in bold and underlined. Data represent the average of 2 independent experiments conducted in triplicate. The error bars represent the standard error between 2 invasion assay experiments. Gray bars: neuraminidase-treated erythrocytes; white bars: trypsin-treated erythrocytes; thatched bars: chymotrypsin-treated erythrocytes.

CyRPA, RH5, and MSP-119 Exhibited Limited Polymorphisms Among the Plasmodium falciparum Clinical Isolates

One of the major impediments in malaria vaccine development has been the high level of antigenic polymorphism in parasite antigens that facilitates immune escape and limits vaccine efficacy. Thus, we analyzed the genetic diversity among the most potent vaccine targets of our portfolio (RH5, CyRPA, and MSP-119) among worldwide P. falciparum strains including the Indian and the African clinical isolates. Because the focus of our study has been invasion inhibition, we have focused on the MSP-119 sequence polymorphisms, because MSP-3 is associated with ADCI that is outside the scope of the current study. We analyzed the polymorphisms in the full-length RH5 and CyRPA and the region of MSP-119 that was used to produce the MSP-Fu construct in the Indian and African clinical isolates as well as in >200 global clinical isolates whose genome sequences are available (www.plasmodb.org). Nonsynonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with a frequency ≥10% in a particular geographical region were considered to be globally prevalent because this threshold frequency is indicative of a balancing pressure on an antigen.

CyRPA was highly conserved with only 10 nonsynonymous SNPs detected among the 237 P. falciparum isolates and strains (Supplementary Table S1). However, all SNPs were detected at very low frequencies (<10%) in a continent- or country-wise distribution (Supplementary Table S2), thus indicating that these allelic SNPs are not under balancing selection. Among the Indian (Jabalpur) and African (Mozambican) clinical isolates, we found only a single nonsynonymous SNP (L118F) in 2 Indian isolates: RM09 and DP11 (Supplementary Table S1). The frequency of L118F would need to be further ascertained on larger sample size. Among the 237 CyRPA sequences analyzed, 9 haplotypes were observed with polymorphisms at 10 amino acid positions (Supplementary Table S1).

RH5 exhibited limited polymorphisms with nonsynonymous 19 SNPs at 17 amino acid positions with 2 dimorphic SNPs: I204K/N and S197Y/I (Supplementary Table S1). Again, all SNPs were at a low frequency level, with only 1 SNP (C203Y) having a frequency >10% (Supplementary Table S2) However, if country-wise frequency distribution was considered, then the number of common SNPs was increased to 3, including I407V (12% in Senegal; 25% in Uganda) and K429N (12.5% in Uganda). However, the K429N frequency would need to be further validated with a larger sample size. Among the 241 RH5 sequences analyzed, 24 haplotypes were observed with polymorphisms at 17 amino acid positions (Supplementary Table S1).

Among all the 3 antigens, MSP-119 was found to be most polymorphic both in terms of SNPs number and their respective frequencies. A total of 214 isolates were analyzed, and 7 SNPs were observed at 7 amino acid positions: E1620Q, T1667K, E1671K, S1675N, S1676N, R1677G, and L1692F. However, none of them was novel and already found in laboratory clones. MSP-119 exhibited 9 haplotypes with 5 SNPs (E1620Q, T1667K, S1676N, R1677G, and L1692F) having a frequency >10% of which L1692F had a frequency greater than 10% only within the Central and South America continents (Supplementary Table S2).

These results, taken together, demonstrate that CyRPA is a highly conserved target antigen. RH5 exhibited limited polymorphism with 2 SNPs >10% frequency. MSP-119 had 5 SNPs with high frequencies, but none were novel and have already been reported in laboratory clones. More importantly, our MSP-Fu antibodies raised against the Welcome strain of MSP-119 were demonstrated to be equally efficacious against 5 laboratory clones, which shared 4 of the 6 MSP-119 SNPs and 2 haplotypes between them (Supplementary Figure S9). Thus, in addition to CyRPA and RH5 antibodies, MSP-119 antibodies generated by MSP-Fu exhibit a potent strain-transcending parasite-neutralizing activity.

MSP-Fu/CyRPA/RH5 Antibody Combination Exhibited Potent Parasite Neutralization Activity Against Plasmodium falciparum Clinical Isolates With Diverse Erythrocyte Invasion Phenotypes and Polymorphic Variants

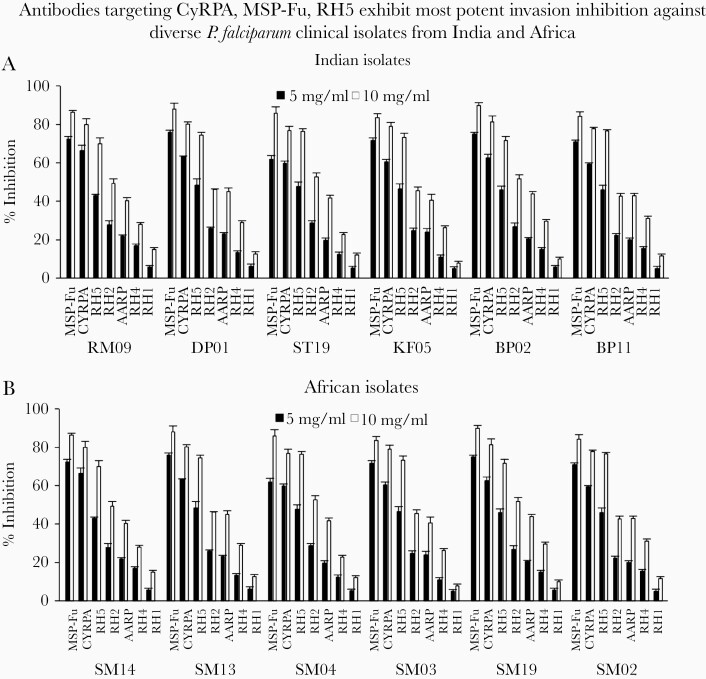

We evaluated the invasion inhibitory activity of the most potent antibody combination MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 from our portfolio against the 12 clinical isolates from the 2 malaria-endemic regions that represented both sialic acid-independent and -dependent invasion phenotypes (Figure 5). Among the 12 isolates, 8 isolates (Indian and African) were sialic acid independent (BP02, DP01, DP11, RM09, ST11, SM04, SM13, and SM19) and 4 were sialic acid dependent (KF05, SM02, SM03, and SM14). In addition to the distinct invasion phenotypes, the 12 clinical isolates and the 5 laboratory clones also represented distinct polymorphic haplotypes for each antigen: CyRPA, 2 of 10 haplotypes; RH5, 9 of 25 haplotypes; MSP-119, 3 of 10 haplotypes (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 5.

Parasite-neutralizing activity of our panel of antibodies tested individually against Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates from India and Africa. Growth inhibition assays (GIA) activity of 7 individual antibodies against (A) 6 Indian clinical isolates and (B) 6 African clinical isolates at 2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentrations of 5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL (Total IgG) in 1- and 2-cycle assays. The antibodies against MSP-Fu, CyRPA, and RH5 were most potent as observed previously with laboratory clones. Data represent the average of 2 independent experiments conducted in triplicate. The error bars represent the standard error between 2 independent GIA experiments.

Our panel of antibodies was evaluated individually against the clinical isolates, and consistent with GIA observed against the laboratory clones, the antibodies against CyRPA, MSP-Fu, and RH5 exhibited most potent parasite-neutralizing activity (Figure 5A and B). Likewise, the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination exhibited potent parasite neutralization against all 12 P. falciparum clinical isolates (Figure 6A and B). The invasion inhibition elicited by the triple antibody combination at concentrations (.5 mg/mL or 1.0 mg/mL total IgG each) was either higher or equivalent to the individual inhibitory effect of the antibodies at 5 mg/mL against the respective parasites, thus substantiating the potent parasite neutralization effect of the triple antibody combination. Thus, through our systematic screening and evaluation of our portfolio of 7 antibodies, the antibody combination of MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 was identified to elicit the most potent, strain-transcending parasite neutralization against multiple P. falciparum clones and clinical isolates at the minimal IgG concentrations.

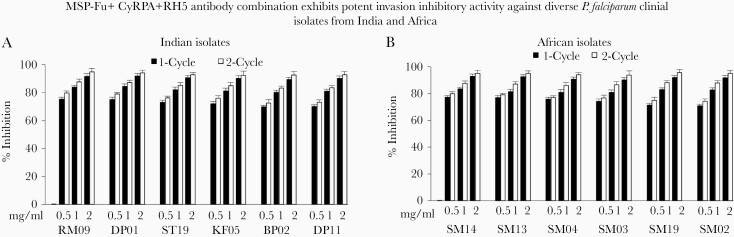

Figure 6.

Parasite-neutralizing activity of the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 combination against Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates from India and Africa. The most potent antibody combination of MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 was tested for its growth inhibition assay (GIA) activity against the (A) 6 Indian clinical isolates and (B) 6 African clinical isolates at 3 immunoglobulin G concentrations (.5 mg/mL each, 1.0 mg/mL each, 2.0 mg/mL each) in 1- and 2-cycle assays. Consistent with our own results on laboratory-adapted clones, the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibodies exhibited potent parasite-neutralizing activity. Data represent the average of 2 independent experiments conducted in triplicate. The error bars represent the standard error between 2 independent GIA experiments.

CoImmunized Antigen Mixture (MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5) Elicited Potent Strain-Transcending Invasion-Inhibitory Antibodies

After evaluating the GIA activity of antibodies combined in vitro, we analyzed whether the most potent combination (MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5) would elicit potent invasion-inhibitory antibodies on coimmunization in mice as a single formulation. Mice immunizations were also conducted with the individual 3 antigens. A head-to-head comparison of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay results (OD492) showed that equivalent titers of antibodies against each protein were induced whether immunized individually or as a mixture with the 2 other antigens (Supplementary Figure S10). Thus, our 3 recombinant proteins were immunogenic and did not induce any interference in the immunogenicity of the respective antigens on coimmunization.

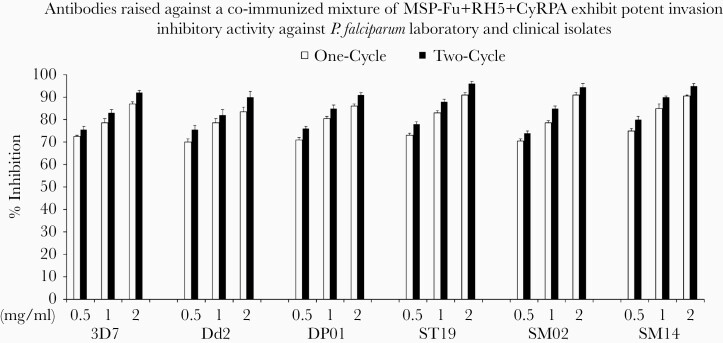

Consistent with the invasion inhibition of the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibodies when combined in vitro, the antibodies raised against the coimmunized antigen mixture of MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 were also highly potent and equally efficacious in inhibiting erythrocyte invasion (Figure 7). Thus, antibodies raised against coimmunized antigen mixtures were as potent in efficiently blocking erythrocyte invasion as antibodies combined in the in vitro invasion inhibition assays.

Figure 7.

Invasion-inhibitory activities of mouse antibodies raised against the coimmunized antigen formulations. The MSP-Fu+RH5+CyRPA antigen combination was formulated with Freund’s adjuvant (Freund’s Complete Adjuvant/Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant) and used for mice immunizations. Seventeen micrograms of each antigen was immunized in each mouse, whether used alone or as a coimmunization triple-antigen mixture (total, 51 μg). Total immunoglobulin G purified from mice sera raised against the antigen combination of MSP-Fu+RH5+CyRPA was evaluated for its growth inhibition assays (GIA) activity (at concentrations of .5, 1.0, 2.0 mg/mL) against 6 Plasmodium falciparum strains (2 laboratory clones 3D7 and Dd2; and 4 clinical isolates DP01, ST19, SM14, and SM02). The antibodies raised against the antigen mixture displayed a GIA activity of 70%–75% (.5 mg/mL each), 78.5%–83% (1.0 mg/mL each), and 83.5%–92% (2.0 mg/mL each) inhibition of the P. falciparum clones (3D7 and Dd2) in 1-cycle and 2-cycle assays. For the clinical isolates, the inhibitions varied between 70.5%–80%, 78.5%–90%, and 86%–96% at .5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL, and 2.5 mg/mL, respectively, for 1- and 2-cycle assays. Data represent the average of 2 independent experiments conducted in duplicate. The error bars represent the standard error between 2 independent GIA experiments.

DISCUSSION

Clinical immunity to malaria is the result of combined protective effects of antibodies against multiple parasite antigens involved in erythrocyte invasion [44, 45]. Thus, an innovative approach towards development of an efficacious blood-stage malaria vaccine is to target multiple essential and conserved parasite antigens involved at different steps of erythrocyte invasion that would not only accomplish potent parasite neutralization at low antibody concentrations but also prevent immune escape by reducing immune pressure on a single target antigen. Previous studies have reported antibody combinations, primarily based on RH5, which elicit strong, strain-transcending invasion inhibitory antibody responses. Likewise, we have previously reported triple antibody combinations (PfF2+PfRH2+AARP; PfRH5+PfRH2+AARP) to elicit potent invasion inhibition at a total IgG concentration of 10 mg/mL, which, however, in the physiological range is not considered feasible to be achieved by human immunization.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has reported the evaluation of antibody combinations targeting the essential antigens, MSP-119 [14] and RH5/CyRPA, that constitute a critical invasion complex [31, 34]. We have thus undertaken a systematic and extensive exercise to screen antibody combinations targeting a portfolio of merozoite antigens including the essential proteins, MSP-119, RH5, and CyRPA. As an improvement over the poorly immunogenic MSP-119, the MSP-Fu chimera (MSP-311-MSP-119) has been developed that induced potent parasite-neutralizing anti-MSP-119 antibodies [17, 18]. More importantly, we have produced recombinant CyRPA, which is a highly conserved target and also elicits potent parasite-neutralizing antibodies with inhibitory activity equivalent to that of MSP-Fu antibodies. Thus, both MSP-Fu and CyRPA are highly conserved, essential target antigens that, among our portfolio, induced the most potent parasite-neutralizing antibodies [17, 18, 31]. Our study identified the antibody combination MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 to elicit the maximal parasite neutralization in our portfolio at a much lower concentration of antibodies compared with earlier studies [10, 11]. More importantly, our combination vaccine neutralizes parasites by multiple mechanisms. RH5 antibodies block its essential interaction with both its receptor Basigin and interacting partner (CyRPA) [46–48]. CyRPA lacks erythrocyte binding and its antibodies are demonstrated to block complex formation [30, 49]. However, not all complex inhibiting antibodies display invasion inhibition [30], and thus the mechanism of action of parasite-neutralizing antibodies targeting the RH5/CyRPA/Ripr complex needs to be further delineated (Supplementary Results and Discussion). MSP-119 antibodies neutralize the parasite by inhibiting direct invasion or secondary MSP-1 processing or postinvasion parasite growth (Supplementary Results and Discussion) [50]. MSP-119 antibodies induced by MSP-Fu have been reported to exhibit invasion inhibitory and processing inhibitory activity [17].

The evolution of redundant invasion pathways and antigenic diversity are the primary immune escape mechanisms of P. falciparum parasites that remain major challenges for blood-stage malaria vaccine development. Although, it is imperative to initially test the vaccine potential with P. falciparum laboratory-adapted clones, it is highly plausible that they may not represent the true phenotypic variation in erythrocyte invasion and antigenic polymorphisms exhibited by the natural circulating P. falciparum parasites in human populations. Therefore, we validated the potent parasite neutralization exhibited by the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination against P. falciparum clinical isolates that were obtained from 2 geographically different malaria-endemic regions of the world: India and Mozambique (Africa). The clinical isolates exhibited diverse invasion phenotypes, some of which have not been reported for any laboratory adapted clone, suggesting a high level of complexity in the invasion process and thus reiterating the importance of experimental validation with P. falciparum clinical isolates. Consistent with the results with the laboratory clones, the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 antibody combination potently neutralized 12 P. falciparum clinical isolates representing distinct invasion phenotypes.

A high degree of antigenic diversity in the leading blood-stage vaccine candidate, AMA-1, has precluded its development as a blood-stage malaria vaccine [9]. Thus, it was critical to analyze the genetic diversity of our 3 primary target antigens (RH5, CyRPA, and MSP-119) among various worldwide P. falciparum clones and clinical isolates. The sequence analysis confirmed that CyRPA, MSP-119, and RH5 were highly conserved antigens. We found no SNPs in CyRPA with a frequency >10%, whereas only 1 SNP frequency >10% was observed in RH5. Although, MSP-119 is highly conserved compared with full-length MSP-1, distinct haplotypes have been well described. We generated MSP-119-specific antibodies from MSP-Fu, and their strain-transcending activities were confirmed against distinct MSP-119 polymorphic haplotypes in laboratory and clinical isolates. More importantly, we also demonstrated that the parasite-neutralizing activity of antibodies generated against the coimmunized antigen mixture of MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 were as potent as observed on combining the individual antibodies in vitro, thus substantiating the feasibility for the MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5 combination malaria vaccine.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study has systematically screened promising blood-stage vaccine candidates against P. falciparum laboratory clones to identify the most efficacious triple antibody combination, MSP-Fu+CyRPA+RH5, amongst our portfolio that exhibited equally potent parasite neutralization against the highly diverse P. falciparum clinical isolates. Our results significantly highlight the benefits of targeting MSP-119 in combination with the RH5/CyRPA/Ripr invasion complex and has established a proof of principle for the development of a new-generation, multicomponent, blood-stage, candidate malaria vaccine that addresses the long-standing challenges of targeting essential conserved targets and countering antigenic diversity.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Presented in part: Molecular Approaches to Malaria (MAM 2020), Lorne, Victoria, Australia, 23–27 February 2020.

Acknowledgments. We dedicate this manuscript to the memory of Dr. Neeru Singh, Former-Director, National Institute for Research in Tribal Health (NIRTH), Jabalpur. We thank the following: Dr. Louis Miller (National Institutes of Health [NIH]) for providing the P. falciparum laboratory-adapted clones; and the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB) animal facility and the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) Central Laboratory Animal Resources for their technical assistance.

Financial support. D. G. is the recipient of the Ramalingaswami Fellowship from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. Research work in Indian institutions was supported by the following grants: Vaccine Grand Challenge Program Department of Biotechnology (to D. G. and V. S. C); GLUE program Department of Biotechnology (to D. G., V. S. C., P. K. B., and N. S.); Indo-Spanish Science & Technological Cooperation, Department of Science & Technology (to D. G. and V. S. C.); Extramural Program, Science & Engineering Research Board (to D. G.); DST-PURSE Program, Department of Science & Technology (to D. G.); and DST-FIST Program, Department of Science & Technology (to D. G.). H. S. and S. Y. M. are the recipients of the Senior Research Fellowship of the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. K. S. R. and V. B. are the recipients of Senior Research Fellowships of the Council for Scientific & Industrial Research, Government of India. G. A. was the recipient of Senior Research Fellowship of the University Grants Commission, Government of India. ISGlobal receives support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the “Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2019–2023” Program (CEX2018-000806-S) and support from the Generalitat de Catalunya through the CERCA Program. This research is part of ISGlobal’s Program on the Molecular Mechanisms of Malaria, which is partially supported by the Fundación Ramón Areces. Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça (CISM) is supported by the Government of Mozambique and the Spanish Agency for International Development. The growth inhibitory activity (GIA) conducted at the GIA reference center was supported by the Intramural Research Program of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and US Agency for International Development (USAID).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). World Malaria Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaur D, Mayer DC, Miller LH. Parasite ligand-host receptor interactions during invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium merozoites. Int J Parasitol 2004; 34:1413–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowman AF, Crabb BS. Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell 2006; 124:755–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaur D, Chitnis CE, Chauhan VS. Molecular basis of erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium merozoites. Advances in Malaria Research. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016: pp 33–86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chitnis CE, Gaur D, Chauhan VS. Progress in development of malaria vaccines. Advances in Malaria Research. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016: pp 521–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeson JG, Kurtovic L, Dobaño C, et al. Challenges and strategies for developing efficacious and long-lasting malaria vaccines. Sci Transl Med 2019; 11:eaau1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The malERA Consultative Group on Vaccines. A research agenda for malaria eradication: vaccines. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogutu BR, Apollo OJ, McKinney D, et al. Blood stage malaria vaccine eliciting high antigen-specific antibody concentrations confers no protection to young children in Western Kenya. PLoS One 2009; 4:e4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spring MD, Cummings JF, Ockenhouse CF, et al. Phase 1/2a study of the malaria vaccine candidate apical membrane antigen-1 (AMA-1) administered in adjuvant system AS01B or AS02A. PLoS One 2009; 4:e5254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandey AK, Reddy KS, Sahar T, et al. Identification of a potent combination of key Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens that elicit strain-transcending parasite-neutralizing antibodies. Infect Immun 2013; 81:441–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy KS, Pandey AK, Singh H, et al. Bacterially expressed full-length recombinant Plasmodium falciparum RH5 protein binds erythrocytes and elicits potent strain-transcending parasite-neutralizing antibodies. Infect Immun 2014; 82:152–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douglas AD, Williams AR, Illingworth JJ, et al. The blood-stage malaria antigen PfRH5 is susceptible to vaccine-inducible cross-strain neutralizing antibody. Nat Commun 2011; 2:601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Illingworth JJ, Alanine DG, Brown R, et al. Functional comparison of blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum malaria vaccine candidate antigens. Front Immunol 2019; 10:1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holder AA, Guevara Patiño JA, Uthaipibull C, et al. Merozoite surface protein 1, immune evasion, and vaccines against asexual blood stage malaria. Parassitologia 1999; 41:409–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okech BA, Corran PH, Todd J, et al. Fine specificity of serum antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein, PfMSP-1(19), predicts protection from malaria infection and high-density parasitemia. Infect Immun 2004; 72:1557–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chitnis CE, Mukherjee P, Mehta S, et al. Phase I clinical trial of a recombinant blood stage vaccine candidate for Plasmodium falciparum malaria based on MSP1 and EBA175. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0117820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazumdar S, Mukherjee P, Yazdani SS, Jain SK, Mohmmed A, Chauhan VS. Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP-1)-MSP-3 chimeric protein: immunogenicity determined with human-compatible adjuvants and induction of protective immune response. Infect Immun 2010; 78:872–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta PK, Mukherjee P, Dhawan S, et al. Production and preclinical evaluation of Plasmodium falciparum MSP-119 and MSP-311 chimeric protein, PfMSP-Fu24. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014; 21:886–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oeuvray C, Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Gras-Masse H, et al. Merozoite surface protein-3: a malaria protein inducing antibodies that promote Plasmodium falciparum killing by cooperation with blood monocytes. Blood 1994; 84:1594–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imam M, Devi YS, Verma AK, Chauhan VS. Comparative immunogenicities of full-length Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 3 and a 24-kilodalton N-terminal fragment. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2011; 18:1221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duraisingh MT, Triglia T, Ralph SA, et al. Phenotypic variation of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite proteins directs receptor targeting for invasion of human erythrocytes. EMBO J 2003; 22:1047–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Triglia T, Duraisingh MT, Good RT, Cowman AF. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 1 is required for sialic acid-dependent invasion into human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol 2005; 55:162–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaur D, Furuya T, Mu J, Jiang LB, Su XZ, Miller LH. Upregulation of expression of the reticulocyte homology gene 4 in the Plasmodium falciparum clone Dd2 is associated with a switch in the erythrocyte invasion pathway. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2006; 145:205–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaur D, Singh S, Singh S, Jiang L, Diouf A, Miller LH. Recombinant Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte homology protein 4 binds to erythrocytes and blocks invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:17789–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayton K, Gaur D, Liu A, et al. Erythrocyte binding protein PfRH5 polymorphisms determine species-specific pathways of Plasmodium falciparum invasion. Cell Host Microbe 2008; 4:40–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baum J, Chen L, Healer J, et al. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 5 - an essential adhesin involved in invasion of human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Int J Parasitol 2009; 39:371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss GE, Gilson PR, Taechalertpaisarn T, et al. Revealing the sequence and resulting cellular morphology of receptor-ligand interactions during Plasmodium falciparum invasion of erythrocytes. PLoS Pathog 2015; 11:e1004670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bustamante LY, Bartholdson SJ, Crosnier C, et al. A full-length recombinant Plasmodium falciparum PfRH5 protein induces inhibitory antibodies that are effective across common PfRH5 genetic variants. Vaccine 2013; 31:373–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglas AD, Baldeviano GC, Lucas CM, et al. A PfRH5-based vaccine is efficacious against heterologous strain blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum infection in aotus monkeys. Cell Host Microbe 2015; 17:130–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alanine DGW, Quinkert D, Kumarasingha R, et al. Human antibodies that slow erythrocyte invasion potentiate malaria-neutralizing antibodies. Cell 2019; 178:216–28.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reddy KS, Amlabu E, Pandey AK, Mitra P, Chauhan VS, Gaur D. Multiprotein complex between the GPI-anchored CyRPA with PfRH5 and PfRipr is crucial for Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:1179–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Lopaticki S, Riglar DT, et al. An EGF-like protein forms a complex with PfRh5 and is required for invasion of human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog 2011; 7:e1002199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dreyer AM, Matile H, Papastogiannidis P, et al. Passive immunoprotection of Plasmodium falciparum-infected mice designates the CyRPA as candidate malaria vaccine antigen. J Immunol 2012; 188:6225–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volz JC, Yap A, Sisquella X, et al. Essential role of the PfRh5/PfRipr/CyRPA complex during Plasmodium falciparum invasion of erythrocytes. Cell Host Microbe 2016; 20:60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galaway F, Drought LG, Fala M, et al. P113 is a merozoite surface protein that binds the N terminus of Plasmodium falciparum RH5. Nat Commun 2017; 8:14333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamborrini M, Hauser J, Schäfer A, et al. Vaccination with virosomally formulated recombinant CyRPA elicits protective antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum parasites in preclinical in vitro and in vivo models. NPJ Vaccines 2020; 5:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valmaseda A, Macete E, Nhabomba A, et al. Identifying immune correlates of protection against Plasmodium falciparum through a novel approach to account for heterogeneity in malaria exposure. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:586–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bustamante LY, Powell GT, Lin YC, et al. Synergistic malaria vaccine combinations identified by systematic antigen screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017; 114:12045–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams AR, Douglas AD, Miura K, et al. Enhancing blockade of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion: assessing combinations of antibodies against PfRH5 and other merozoite antigens. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1002991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh N, Chand SK, Bharti PK, et al. Dynamics of forest malaria transmission in Balaghat district, Madhya Pradesh, India. PLoS One 2013; 8:e73730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayor A, Hafiz A, Bassat Q, et al. Association of severe malaria outcomes with platelet-mediated clumping and adhesion to a novel host receptor. PLoS One 2011; 6:e19422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahar T, Reddy KS, Bharadwaj M, et al. Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte binding-like homologue protein 2 (PfRH2) is a key adhesive molecule involved in erythrocyte invasion. PLoS One 2011; 6:e17102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wickramarachchi T, Devi YS, Mohmmed A, Chauhan VS. Identification and characterization of a novel Plasmodium falciparum merozoite apical protein involved in erythrocyte binding and invasion. PLoS One 2008; 3:e1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richards JS, Arumugam TU, Reiling L, et al. Identification and prioritization of merozoite antigens as targets of protective human immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria for vaccine and biomarker development. J Immunol 2013; 191:795–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Healer J, Chiu CY, Hansen DS. Mechanisms of naturally acquired immunity to P. falciparum and approaches to identify merozoite antigen targets. Parasitology 2018; 145:839–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright KE, Hjerrild KA, Bartlett J, et al. Structure of malaria invasion protein RH5 with erythrocyte basigin and blocking antibodies. Nature 2014; 515:427–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Douglas AD, Williams AR, Knuepfer E, et al. Neutralization of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites by antibodies against PfRH5. J Immunol 2014; 192:245–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Healer J, Wong W, Thompson JK, et al. Neutralising antibodies block the function of Rh5/Ripr/CyRPA complex during invasion of Plasmodium falciparum into human erythrocytes. Cell Microbiol 2019; 21:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen L, Xu Y, Wong W, et al. Structural basis for inhibition of erythrocyte invasion by antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum protein CyRPA. Elife 2017; 6:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moss DK, Remarque EJ, Faber BW, et al. Plasmodium falciparum 19-kilodalton merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1)-specific antibodies that interfere with parasite growth in vitro can inhibit MSP1 processing, merozoite invasion, and intracellular parasite development. Infect Immun 2012; 80:1280–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.