Abstract

Background

We have carried out a study to determine the scope for reducing heart doses in photon beam radiotherapy of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (LA-NSCLC).

Materials and methods

Baseline VMAT plans were created for 20 LA-NSCLC patients following the IDEAL-CRT isotoxic protocol, and were re-optimized after adding an objective limiting heart mean dose (MDHeart). Reductions in MDHeart achievable without breaching limits on target coverage or normal tissue irradiation were determined. The process was repeated for objectives limiting the heart volume receiving ≥ 50 Gy (VHeart-50-Gy) and left atrial wall volume receiving ≥ 63 Gy (VLAwall-63-Gy).

Results

Following re-optimization, mean MDHeart, VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy values fell by 4.8 Gy and 2.2% and 2.4% absolute respectively. On the basis of associations observed between survival and cardiac irradiation in an independent dataset, the purposefully-achieved reduction in MDHeart is expected to lead to the largest improvement in overall survival. It also led to useful knock-on reductions in many measures of cardiac irradiation including VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy, providing some insurance against survival being more strongly related to these measures than to MDHeart. The predicted hazard ratio (HR) for death corresponding to the purposefully-achieved mean reduction in MDHeart was 0.806, according to which a randomized trial would require 1140 patients to test improved survival with 0.05 significance and 80% power. In patients whose baseline MDHeart values exceeded the median value in a published series, the average MDHeart reduction was particularly large, 8.8 Gy. The corresponding predicted HR is potentially testable in trials recruiting 359 patients enriched for greater MDHeart values.

Conclusions

Cardiac irradiation in RT of LA-NSCLC can be reduced substantially. Of the measures studied, reduction of MDHeart led to the greatest predicted increase in survival, and to useful knock-on reductions in other cardiac irradiation measures reported to be associated with survival. Potential improvements in survival can be trialled more efficiently in a population enriched for patients with greater baseline MDHeart levels, for whom larger reductions in heart doses can be achieved.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13014-021-01824-3.

Keywords: NSCLC, Cardiac-sparing, Radiotherapy, Heart, Survival

Background

Radical chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is the standard-of-care for patients with inoperable locally-advanced non-small cell lung cancer (LA-NSCLC). In a meta-analysis, improved overall survival (OS) following radiotherapy (RT) alone or sequential CRT was associated with increased tumour radiation doses [1]. For concurrent CRT, however, survival was significantly shorter in the high-dose arm of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG)-0617 randomized trial of 74 Gy versus 60 Gy [2].

The RTOG-0617 finding might be explained by survival-limiting toxicities at higher dose-levels. Analysis of data from the IDEAL-CRT trial demonstrated a significant negative association between OS and left atrial (LA) wall volumes receiving radiation doses ≥ 63 Gy in LA-NSCLC patients treated using concurrent CRT [3]. Similarly, in patients treated routinely with RT ± induction chemotherapy, OS was negatively associated with doses delivered to the base of heart, a region formed by the two atria [4]. And in RTOG-0617 patients, OS was also negatively associated with cardiac irradiation [2].

Difficulties distinguishing deaths related to radiation-induced heart disease (RIHD) from cancer-related deaths make it challenging to determine whether these associations are causal. Furthermore, causal explanations other than RIHD are possible, for example an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio resulting from heart irradiation [5]. Non-causal explanations have also been proposed, such as associations between heart doses and the location of involved mediastinal nodes [6], previously found to affect survival. However, in a multivariable analysis of survival in IDEAL-CRT, heart irradiation remained independently significantly associated with OS even when N2/3 disease and subcarinal nodal involvement were included in the analysis [3]. A randomized trial of cardiac-sparing RT would potentially provide the clearest demonstration of a causal link between heart doses and survival for LA-NSCLC patients.

Here, we determine the extent to which heart doses can be reduced. Since limits placed on heart doses have been met easily in many trials [2, 7] we have investigated lower and more challenging limits within an existing dose-escalation study design. Using the CT scans of patients who had received routine treatment, new baseline plans were created representing the treatments these patients would have received in the IDEAL-CRT study, in which tumour doses of 63–73 Gy in 30 fractions were prescribed isotoxically [8]. Then we determined by how much heart irradiation could be reduced without breaching protocol limits on irradiation of other organs-at-risk (OARs) or dose-coverage of planning and clinical target volumes (PTV/CTVs).

Because the cardiac irradiation measure most predictive of shorter survival has yet to be conclusively identified, we tested the feasibility of reducing three measures reported to be associated with OS or risk of major coronary events: heart mean dose (MDHeart) [9, 10]; the whole-heart fractional volume receiving ≥ 50 Gy (VHeart-50-Gy) [11]; and the LA wall volume receiving ≥ 63 Gy (VLAwall-63-Gy) [3]. We have also investigated the degree to which reductions made purposefully in these three measures generate knock-on reductions in the others, and the additional knock-on reductions they generate in doses delivered to the right atrium, left and right ventricles, aortic valve, ascending aorta and right coronary artery, which have also been found to be associated with survival [12–14]. Finally, expected improvements in OS were calculated for the mean reductions achieved in MDHeart, VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy, and used to estimate numbers of patients that would be needed to detect survival improvements in randomized trials.

Methods

Study plans were created with institutional approval for 20 anonymized LA-NSCLC patients, 12 stage IIIA and 8 IIIB with an equal split of left- and right-sided disease, treated at Clatterbridge Cancer Centre (CCC) during 2016–2017 (Additional file 1: Table S1). Internal gross tumour volumes (iGTVs) were defined by drawing contours on 4D-CT average-intensity projections (AIPs), and were expanded by 5 mm to form clinical target volumes (CTVs) and another 5 mm to form PTVs. OAR contours were also drawn on the AIPs. Heart outlines were drawn according to SCOPE-1 and IDEAL-CRT study guidelines [15]. Delineation of cardiac structures was guided by published atlases [16, 17], with LA wall defined as the region ≤ 5 mm within the LA contour [3] and the aortic valve region as the valve plus 5 mm to allow for movement [12].

Treatments were planned in Eclipse version 13.6 (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, Ca) using the Acuros dose algorithm. Baseline dual-arc VMAT plans covered 99% of the CTV and 90% of the PTV with ≥ 95% of the prescribed dose, and 98% of the PTV with ≥ 90% of this dose [8]. Doses were prescribed to the median PTV level, and initially selected so that the mean equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions across both lungs minus iGTV (EQD2Lung-mean, α/β = 3 Gy) was 16.5 Gy for each patient. Then they were limited to 63–73 Gy and reduced if necessary to meet the IDEAL-CRT normal tissue dose-volume limits listed in Additional file 1: Table S2 [8]. Reflecting routine CCC practice, optimization included an objective with a priority level of 100 to minimize cardiac hot-spots above the prescribed dose-level, and further objectives whose priorities were raised from 50 if cardiac dose-volume measures exceeded protocol limits.

These plans were re-optimized, raising the prioritization of an additional penalty designed to reduce MDHeart, and determining the maximum reduction in this index achievable without changing the prescribed dose or violating the coverage constraints or OAR dose-volume limits of Additional file 1: Table S2. This process was repeated, re-optimizing using new penalties designed to lessen VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy.

For the baseline and re-optimized plans, target volume coverage-levels were noted together with values of MDHeart, VHeart-50-Gy, VLAwall-63-Gy and the OAR dose-volume measures of Additional file 1: Table S2. Mean physical doses in the LA wall, aortic valve region and lungs minus iGTV were also noted, together with mean and maximum doses in the right atrium and both ventricles, ascending aorta and right coronary artery. Volumes of lungs minus iGTV receiving ≥ 10, 30 and 50 Gy (VLung-10,30,50-Gy) and the aortic valve region receiving 35–43 Gy (VAVR-35–43-Gy) were also recorded.

To contextualize cardiac irradiation-levels, we identified targets for the purposefully reduced dose-volume measures. For MDHeart, basic, moderate and ambitious target-levels were defined as 20, 11 and 5 Gy, corresponding to roughly the 85th, 50th and 20th MDHeart percentiles in a patient cohort in which 2-year cumulative incidence of grade ≥ 3 cardiac events was 2% in patients with MDHeart ≤ 11 Gy versus 18% in others [10]. For VHeart-50-Gy, analogous levels of 25%, 4% and 0.5% were identified. The first reflects results from a study in which 2-year OS was 20% higher for patients with VHeart-50-Gy < 25% than for others [11]. The latter two were the 50th and 20th percentiles of VHeart-50-Gy values in IDEAL-CRT. For VLAwall-63-Gy, levels of 20%, 2.2% and 0% were identified, roughly the 85th, 50th and 33rd VLAwall-63-Gy percentiles in IDEAL-CRT patients, amongst whom 2-year survival was 23% higher in patients with VLAwall-63-Gy < 2.2% than in others [3].

Reduced heart irradiation might be accompanied by diminished target volume coverage or increased irradiation of other OARs, even while remaining within protocol limits. Details of any lessening of coverage are provided, together with changes in lung irradiation. Significances of changes in distributions of these measures were assessed using the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Changes in numbers of patients with OARs lying within 10% of protocol dose-volume limits are also tabulated.

In an independent patient cohort, analysed to validate associations between heart dosimetry and OS seen in the IDEAL-CRT study, hazard ratios (HRs) for all-cause death were 0.956 per 1 Gy decrease in MDHeart, 0.974 per 1% absolute decrease in VHeart-50-Gy, and 0.929 per 1% decrease in a measure equivalent to VLAwall-63-Gy allowing for a small change in fractionation [3, 12]. We translated these values into HRs for the mean reductions in cardiac irradiation achieved in this study. On the basis of the resulting HRs and survival in IDEAL-CRT [18], we have estimated numbers of patients that would be needed for trials designed to test improved OS with a 5% type-I error rate and 80% power, if randomized 1:1 and with 3 years’ recruitment and 2 years’ further followup [19].

Results

Patients and baseline plans

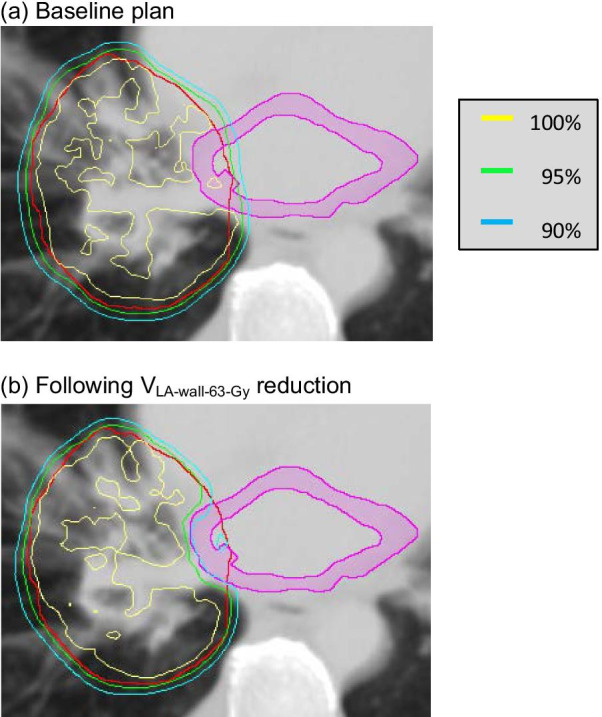

For the patients studied, disease stage, prescribed dose and tumour geometric characteristics are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. For the iGTV, the median volume (range) was 106.0 cm3 (7.4, 243.2 cm3). For the CTV and PTV the median volumes (ranges) of overlaps with the heart were 1.3 cm3 (0, 19.9 cm3) and 8.3 cm3 (0, 42.3 cm3) respectively, two patients having no CTV overlap with the heart and one no PTV overlap. The median volume (range) of overlaps between the PTV and LA wall was 0.1 cm3 (0, 4.1 cm3) with no overlap in 10 patients. Figure 1 shows a CT slice from a patient with a 3.9 cm3 PTV/LA wall overlap.

Fig. 1.

PTV contour and LA wall in a patient with a 3.9 cm3 PTV/LA wall overlap. The PTV is shown in red, and the LA wall structure in pink. Isodose lines representing 68.8, 65.2 and 61.9 Gy (100%, 95% and 90% of the prescribed dose) are plotted a at baseline and b after re-optimization to reduce VLAwall-63-Gy

The median (range) of prescribed doses was 68.8 Gy (63.0, 73.0 Gy). IDEAL-CRT target volume coverage requirements and OAR irradiation limits were met in baseline plans. The limits on heart irradiation were met particularly easily: median values of the minimum doses to the most highly irradiated 100%, 67% and 33% of the heart were 0.6, 1.9 and 4.5 Gy compared to limits of 45, 53 and 60 Gy (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Purposeful MDHeart reductions

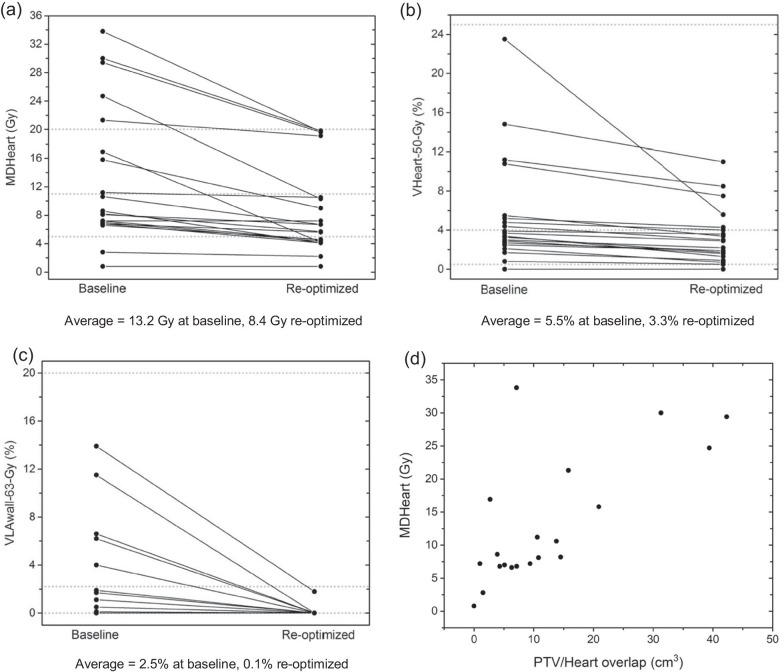

MDHeart values in baseline plans and plans re-optimized to reduce this measure are plotted in Fig. 2a. The average MDHeart reduction was 4.8 Gy, 36% of the mean baseline MDHeart value. Reductions were larger for patients with greater PTV/heart overlaps (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Cardiac dose-volume measures plotted for baseline and re-optimized plans. The re-optimized plans were designed to reduce a MDHeart, b VHeart-50-Gy and c VLAwall-63-Gy. Basic, moderate and ambitious target levels for the different dose-volume measures are shown as dotted lines. In d baseline MDHeart values are plotted against the PTV/Heart overlap

These reductions were achieved without lessening prescribed doses or exceeding protocol dose-volume limits. Tumour coverage measures remained within protocol limits, with small though statistically significant losses (Table 1). For DPTV-90%, the percentage of prescribed dose covering 90% of the PTV, the median (range) was 98.4% (95.3%, 99.0%) at baseline versus 97.9% (95.7, 98.9%) after re-optimization (p < 0.001). There was a small but significant change in values of EQD2Lung-mean, the mean equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions across the both lungs minus iGTV (p = 0.03, Table 2): specifically, the median.

Table 1.

Median values (ranges) of CTV and PTV coverage measures at baseline and after re-optimization, and two-sided significances of changes in distributions of these measures following re-optimization

| Coverage measure (IDEAL-CRT limit) | At baseline | After MDHeart reduction | After VHeart-50-Gy reduction | After VLAwall-63-Gy reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPTV-90%* (≥ 95% prescribed dose) | 98.6% (96.7, 99.0%) |

97.9% (95.7, 98.9%) p = 6 × 10–4 |

98.0% (96.3, 98.9%) p = 2 × 10–4 |

98.4% (95.3, 99.0%) p = 0.31 |

| DPTV-98% (≥ 90% prescribed dose) | 96.7% (92.4, 97.9%) |

95.0% (90.7, 97.3%) p = 4 × 10–4 |

95.1% (91.5, 97.5%) p = 2 × 10–4 |

96.4% (90.4, 97.7%) p = 0.09 |

| DCTV-99% (≥ 95% prescribed dose) | 98.0% (96.5, 98.6%) |

97.6% (95.7, 98.4%) p = 7 × 10–3 |

97.7% (96.1, 98.4%) p = 8 × 10–3 |

97.9% (95.6, 98.6%) p = 0.27 |

| DPTV-99.5% (non-protocol measure) | 95.2% (86.5, 96.9%) |

91.9% (86.7, 96.4%) p = 1 × 10–3 |

92.5% (86.0, 96.4%) p = 3 × 10–4 |

94.6% (86.9, 96.6%) p = 0.09 |

*DStructure-X% denotes the minimum percentage of the prescribed dose covering the most highly irradiated X% of a structure

Table 2.

Median values (ranges) of measures of irradiation of both lungs excluding iGTV, at baseline and after re-optimization, and two-sided significances of changes in distributions of these measures following re-optimization

| Dose-volume measure | At baseline | After MDHeart reduction | After VHeart-50-Gy reduction | After VLAwall-63-Gy reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQD2Lung-mean* | 13.7 Gy (8.0, 16.8 Gy) |

13.9 Gy (7.2, 16.6 Gy) p = 0.03 |

13.7 Gy (7.7, 16.7 Gy) p = 0.07 |

14.1 Gy (8.0, 16.8 Gy) p = 0.86 |

| Mean lung dose | 15.7 Gy (9.4, 19.5 Gy) |

15.8 Gy (8.5, 19.3 Gy) p = 0.03 |

15.7 Gy (9.1, 19.4 Gy) p = 0.06 |

16.0 Gy (9.4, 19.5 Gy) p = 0.89 |

| VLung-10-Gy** | 47.2% (29.0,70.9%) |

46.3% (27.6, 73.9%) p = 5 × 10–3 |

46.5% (29.0, 76.5%) p = 0.16 |

47.5% (29.0, 77.4%) p = 0.88 |

| VLung-20-Gy | 27.2% (15.6, 34.4%) |

28.1% (13.6, 34.8%) p = 0.98 |

26.4% (14.9, 34.5%) p = 0.30 |

26.4% (15.6, 34.9%) p = 0.94 |

| VLung-30-Gy | 17.1% (7.9, 23.7%) |

16.4% (6.7, 24.5%) p = 0.59 |

16.7% (7.7, 23.7%) p = 8 × 10–3 |

16.6% (7.9, 23.7%) p = 0.72 |

| VLung-50-Gy | 7.0% (2.6, 12.2%) |

6.9% (2.2, 14.4%) p = 1.00 |

7.0% (2.4, 12.6%) p = 0.05 |

7.5% (2.6, 12.2%) p = 0.30 |

*Equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions averaged across both lungs minus iGTV

**The fraction of both lungs minus iGTV receiving ≥ 10 Gy

EQD2Lung-mean rose from 13.7 Gy by 0.2 Gy following re-optimization, but the average fell by 0.4 Gy. Numbers of patients with dose-volume metrics lying within 10% of each non-cardiac protocol OAR limit were unchanged after re-optimization for three limits, and rose by one patient each for three limits (Additional file 1: Table S4).

Purposeful VHeart-50-Gy reductions

Values of VHeart-50-Gy in baseline plans and plans re-optimized to reduce VHeart-50-Gy are plotted in Fig. 2b. The average VHeart-50-Gy reduction was 2.2% absolute, 40% of the mean baseline value. Tumour coverage losses were small though significant (Table 1). The median EQD2Lung-mean value following re-optimization was unchanged from baseline (Table 2). Numbers of patients with dose-volume metrics lying within 10% of each OAR limit changed little following re-optimization (Additional file 1: Table S4).

Purposeful VLAwall-63-Gy reductions

VLAwall-63-Gy values are plotted in Fig. 2c. The average VLAwall-63-Gy reduction was 2.4% absolute, 96% of the mean baseline value. Tumour coverage losses were small and insignificant (Table 1). EQD2Lung-mean values were insignificantly larger after re-optimization, the median value rising by 0.4 Gy (Table 2). Numbers of patients with dose-volume metrics lying within 10% of each OAR limit were unchanged following re-optimization for three limits, and rose by one patient for two limits and by two patients for one limit (Additional file 1: Table S4).

Knock-on reductions

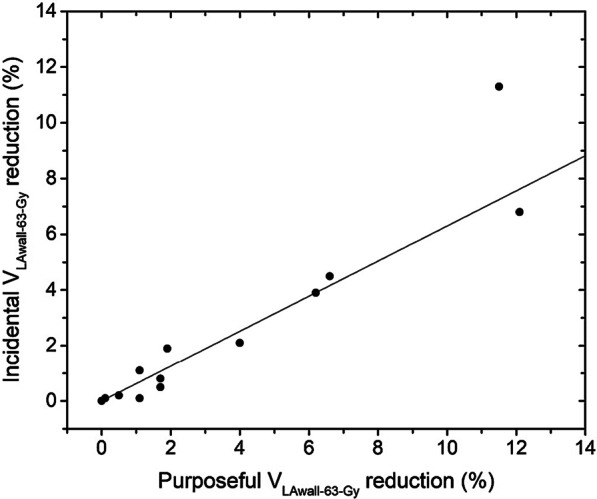

Knock-on reductions in MDHeart, VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy made when purposefully reducing others of these measures are summarized in Table 3. Purposeful reduction of MDHeart led to the greatest average knock-on reductions, amounting to 107% and 68% of the purposefully-achieved reductions for VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy. The knock-on VLAwall-63-Gy reductions accompanying purposeful MDHeart reductions are plotted against purposefully-made VLAwall-63-Gy reductions in Fig. 3.

Table 3.

Average knock-on reductions in cardiac irradiation measures (II) made when other measures (I) were purposefully reduced, compared to average reductions made in the second measure (II) when it was purposefully reduced

| Measure I | Measure II | Average knock-on reduction in measure II | Average purposeful reduction in measure II | Ratio of average knock-on and purposeful reductions in measure II |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDHeart | VHeart-50-Gy | 2.34% | 2.19% | 1.07 |

| MDHeart | VLAwall-63-Gy | 1.65% | 2.43% | 0.68 |

| VHeart-50-Gy | MDHeart | 1.82 Gy | 4.76 Gy | 0.38 |

| VHeart-50-Gy | VLAwall-63-Gy | 1.54% | 2.43% | 0.63 |

| VLAwall-63-Gy | MDHeart | 0.55 Gy | 4.76 Gy | 0.12 |

| VLAwall-63-Gy | VHeart-50-Gy | 0.77% | 2.19% | 0.35 |

Fig. 3.

Knock-on versus purposefully-achieved VLAwall-63-Gy reductions. The knock-on VLAwall-63-Gy reductions were achieved in the course of purposefully reducing MDHeart values. The plotted line represents knock-on reductions as 63% of purposeful reductions

Knock-on reductions in a panel of further measures that resulted from purposeful MDHeart reduction have also been determined (Table 4). Average knock-on reductions in mean doses to the LA wall, right atrium, left and right ventricles, right coronary artery, aortic valve region and ascending aorta were 26–52% of baseline values, and the average reduction in the volume of the aortic valve region receiving 35–43 Gy was 100%.

Table 4.

Average knock-on reductions in other cardiac irradiation measures when MDHeart was purposefully reduced, as a fraction of mean baseline values

| Irradiation measure | Structure | Mean value at baseline | Mean value after MDHeart reduction | Mean knock-on reduction | Fractional mean knock-on reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean dose | LA wall | 17.5 Gy | 12.1 Gy | 5.4 Gy | 31 |

| Right atrium | 12.5 Gy | 8.8 Gy | 4.7 Gy | 38 | |

| Left ventricle | 7.3 Gy | 4.3 Gy | 3.0 Gy | 41 | |

| Right ventricle | 7.0 Gy | 3.4 Gy | 3.6 Gy | 51 | |

| AVR* | 13.8 Gy | 6.7 Gy | 7.1 Gy | 51 | |

| Right CA† | 11.8 Gy | 5.9 Gy | 5.9 Gy | 50 | |

| Ascending aorta | 27.7 Gy | 20.4 Gy | 7.3 Gy | 26 | |

| Max dose | Right atrium | 34.2 Gy | 27.0 Gy | 7.2 Gy | 21 |

| Left ventricle | 29.5 Gy | 23.3 Gy | 6.2 Gy | 21 | |

| Right ventricle | 23.6 Gy | 15.4 Gy | 8.2 Gy | 35 | |

| Right CA | 15.5 Gy | 9.4 Gy | 6.1 Gy | 39 | |

| Ascending aorta | 61.2 Gy | 59.3 Gy | 1.9 Gy | 3 | |

| VLAwall-63-Gy | LA wall | 2.5% | 0.8% | 1.7% | 68 |

| VAVR-35–43-Gy** | AVR | 7.3% | 0% | 7.3% | 100 |

*Aortic valve region

†Coronary artery

**Fractional volume of the AVR receiving 35–43 Gy

Average knock-on reductions in maximum doses to the right atrium, ventricles and right coronary artery were 21–47% of baseline values, but for the ascending aorta the maximum dose was reduced by an average of only 3%. In 14 of the patients studied maximum doses to the ascending aorta were similar to prescribed tumour doses and were located in the section of the vessel lying immediately above the heart. Detailed investigation of the plans of two of these patients showed that only small reductions in volumes of the ascending aorta receiving doses in excess of thresholds between 60 and 95% of the prescribed dose could be achieved by lowering the mean heart dose. However, when the ascending aorta was merged with the heart and the mean dose to this composite structure was reduced these high-dose ascending aorta volumes fell much more, by 35–56% of their baseline values, although maximum doses still fell little.

Trial patient numbers

The mean purposefully-achieved reductions in MDHeart, VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy translate into expected HRs for all-cause death of 0.806, 0.943 and 0.838. Based on these HRs, 1:1 randomized trials designed to test improved OS with a 5% type-I error-rate and 80% power would need 1140, 14,850 or 1798 patients.

Particularly large mean reductions in cardiac dose-volume measures were achieved for patients with baseline values exceeding median values in published series. For the 8 patients with baseline MDHeart > 11 Gy the average reduction in this measure was 8.8 Gy. Similarly, for the 8 patients with VHeart-50-Gy > 4%, the mean VHeart-50-Gy reduction was 4.4%; and for the 5 patients with baseline VLAwall-63-Gy > 2.2%, the mean VLAwall-63-Gy reduction was 8.1%. These reductions correspond to HRs of 0.672, 0.887 and 0.551, based on which 359, 3604 or 170 patients would be needed in trials recruiting from these subpopulations alone.

Discussion

In baseline plans median values of DHeart-100%, DHeart-67% and DHeart-33%, the minimum doses covering 100%, 67% and 33% of the heart, were just 1.3%, 3.6% and 7.5% of their IDEAL-CRT limits. Other groups have reported similar findings [2, 7], showing that typically-used limits do not effectively restrict heart doses during treatment planning. By adding extra optimization objectives mean values of MDHeart, VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy were reduced by 36%, 40% and 96% relative to baseline values, without breaching protocol limits on irradiation of other normal tissues or minimum tumour coverage requirements.

For patients treated for breast cancer, the risk of major coronary events following RT has previously been shown to rise linearly with MDHeart [9]. However, the scale of associations between survival and MDHeart seen in patients treated for LA-NSCLC is greater than expected from the breast RT data. For example, prescribed tumour doses were 16% greater in the high-dose arm of RTOG-0617 than in the low-dose arm, an increase that would have raised MDHeart by an average of roughly 2 Gy. The breast RT data indicates that for a 50 year-old woman with one or more cardiac risk factors, this 2 Gy rise in MDHeart would increase the risk of death from ischaemic heart disease by only around 0.5% absolute [9], and yet in the high-dose arm of RTOG-0617 2-year OS was 13% absolute less than in the low-dose arm. This seemingly greater effect of MDHeart on survival in lung cancer patients needs to be weighed against the detrimental effects of cardiac-sparing seen in our study, namely small increases in numbers of patients with dose-volume metrics lying within 10% of dose-limits, and small reductions in PTV coverage. Net survival gains from cardiac sparing could be tested most clearly in randomized trials, but large numbers of patients would be needed: we estimate 1,140 or 1,798 assuming that OS is causally linked to MDHeart or VLAwall-63-Gy, or 14,850 if OS is causally related to VHeart-50-Gy.

The survival benefit predicted for cardiac-sparing RT is derived largely from patients with baseline heart doses greater than median values in patient series (Fig. 2). For these patients cardiac irradiation can be reduced more, leading to larger predicted survival increases of 13%, 18% or 4% from a 50% level if OS is causally related to MDHeart, VLAwall-63-Gy or VHeart-50-Gy. These increases could be tested more efficiently in trials enriched for such patients [20, 21], who could be identified at baseline planning. Estimated numbers of patients required are notably smaller than for the wider population: 359 or 170 if OS is causally related to MDHeart or VLAwall-63-Gy, or 3,604 if related to VHeart-50-Gy. Because the dose-volume thresholds used for patient selection are published median values, roughly double these numbers would need to be screened, around 700 patients for a study based on MDHeart reduction, making the logistics challenging. Enrichment strategies have been used in trials evaluating treatments in subpopulations positive for biomarkers. Heart irradiation could act as one such biomarker, potentially allowing trialling to be embedded within a larger umbrella study testing treatments for several biomarker-defined subpopulations [22].

As the cardiac dose-volume measure most strongly associated with survival remains to be identified, we have checked the robustness of cardiac-sparing to the possibility that the measure being reduced is not the key one determining survival. Of the three measures purposefully reduced, VLAwall-63-Gy could be decreased most completely. However, its purposeful reduction led to relatively small knock-on reductions in the whole-heart measures. Purposeful reduction of MDHeart was the most robust option explored: overall it offered the greatest predicted survival benefits, and provided large knock-on reductions in VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy, and useful knock-on reductions in a panel of other cardiac irradiation measures reported to be associated with OS. Because the upper section of the ascending aorta lies above the top of the atlas-defined heart volume, maximum doses in this structure were reduced less via mean heart dose reduction. If considered important, however, high-dose volumes of the ascending aorta can be reduced to a greater extent by adding this structure to the heart and reducing the mean dose to the composite volume.

The commonly used target coverage measures reported here fell little as heart doses were reduced (Table 1), although doses within the small PTV/LA wall overlap region sometimes fell more appreciably (Fig. 1). To check this further we collected values for DPTV-99.5%, the percentage of the prescribed dose covering 99.5% of the PTV. The greatest median decrease in DPTV-99.5% was 3.3%, following reduction of MDHeart (Table 1). Such a dose reduction right across the PTV might lessen 2-year OS by 2–4% [23], but the same reduction in DPTV-99.5% should diminish survival much less, because the PTV sub-volumes involved are small (0.5%) [24] and located at the PTV edge where tumour cell density is lower [25].

Cardiac-sparing had little impact on lung irradiation-levels (Table 2), a finding that can be explained straightforwardly. The heart lies quite centrally within the lungs, which are much larger, with a typical total volume of 6 versus 0.35 L [26, 27]. Consequently, even if all the radiation fluence removed from the heart was redistributed to the lungs, the lung mean dose would rise considerably less than the mean heart dose would fall.

Ferris et al. recently reported that heart doses in cardiac-optimized VMAT plans created retrospectively for LA-NSCLC patients treated in 2013–2017 were lower than in the original plans used to treat patients, but could not establish how much this improvement owed to enhanced planning software, increasingly skilled planners, cardiac substructure outlining, or intentional heart-sparing [28]. In our study, the same treatment planner (LT) contemporaneously created baseline and cardiac-sparing plans using the same software, and therefore the reduced heart doses were a direct consequence of objectives added to the optimization process to reduce cardiac irradiation-levels.

Our study is limited to 20 patients with a 50:50 split of left- and right-sided tumours and a 60:40 IIIA/IIIB stage-split, similar to the 65:35 split in RTOG-0617. Subject to achieving these splits, patients were drawn from a contiguous series treated at CCC, expected to represent the wider patient population. The 13.2 Gy average value of mean heart dose in the baseline plans created for these patients is comparable to means of 11.6 and 17.0 Gy reported for series of 78 and 35 LA-NSCLC patients respectively [12, 29], and medians of 11.0 and 16.6 Gy reported for 125 and 468 patients [10, 30]. In the ongoing RTOG-1308 trial of proton versus photon radiotherapy for LA-NSCLC, DHeart-35% and DHeart-50% were limited to 45 Gy and 30 Gy, tighter constraints than typically set [31]. The highest DHeart-33% and DHeart-50% values in our baseline plans were 43.1 Gy and 30.1 Gy, and therefore the tighter RTOG-1308 limits would have negligibly lessened the heart doses in the baseline plans, or the gains achieved via re-optimization.

Conclusions

Heart doses in photon beam RT treatments of LA-NSCLC could be substantially reduced without markedly compromising tumour dose coverage or raising dose-levels in other OARs. In a cohort of 20 routinely-treated patients retrospectively re-planned according to the isotoxic IDEAL-CRT protocol, the average reductions achieved in MDHeart, VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy were 4.8 Gy, 2.2% and 2.4% absolute. Purposeful reduction of MDHeart provided useful knock-on reductions in VHeart-50-Gy, VLAwall-63-Gy and a basket of other measures of cardiac irradiation, insuring against the possibility that these measures are more directly related to survival changes than is MDHeart.

The average purposeful reductions in MDHeart, VHeart-50-Gy and VLAwall-63-Gy translated to predicted OS gains that would require many patients to test in a randomized trial. Average reductions in mean heart doses were larger in subgroups of patients with baseline levels of cardiac irradiation greater than median values in published series, potentially permitting trialling in 359 patients enriched for greater baseline MDHeart values.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- AIP

Average intensity projection

- CCC

Clatterbridge Cancer Centre

- CRT

Chemoradiotherapy

- CT

Computed tomography

- DHeart-XX%

Minimum dose to the most highly irradiated XX% of heart

- DPTV-XX%

Minimum dose to the most highly irradiated XX% of the PTV

- EQD2

Equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions

- EQD2Lung-mean

Mean EQD2 in both lungs minus iGTV

- iGTV

Internal gross tumour volume

- HR

Hazard ratio

- LA

Left atrium

- LA-NSCLC

Locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer

- MDHeart

Heart mean dose

- OAR

Organ at risk

- OS

Overall survival

- PTV

Planning target volume

- RIHD

Radiation induced heart disease

- RT

Radiotherapy

- RTOG

Radiation therapy oncology group

- VAVR-35–43-Gy

Fractional volume of aortic valve regions receiving 35–43 Gy

- VHeart-50-Gy

Fractional heart volume receiving ≥ 50 Gy

- VLAwall-63-Gy

Fractional LA wall volume receiving ≥ 63 Gy

- VLung-XX-Gy

Fractional volume of both lungs minus iGTV receiving ≥ XX Gy

- VMAT

Volumetric modulated arc therapy

Authors' contributions

LT and JF wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

MAH is supported by funding from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Availability of data and materials

Available on request from LT.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Retrospective analysis of patient data which patients had agreed could be used for research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ramroth J, Cutter D, Darby S, Higgins G, McGale P, Partridge M, et al. Dose and fractionation in radiation therapy of curative intent for non-small cell lung cancer: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(4):736–747. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.07.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley J, Paulus R, Komaki R, Masters G, Blumenschein G, Schild S, et al. Standard-dose versus high-dose conformal radiotherapy with concurrent and consolidation carboplatin plus paclitaxel with or without cetuximab for patients with stage IIIA or IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer (RTOG 0617): a randomised, two-by-two factorial phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):187–199. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(14)71207-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vivekanandan S, Landau D, Counsell N, Warren D, Khwanda A, Rosen S, et al. The impact of cardiac radiation dosimetry on survival after radiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;99(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McWilliam A, Kennedy J, Hodgson C, Vasquez Osorio E, Faivre-Finn C, van Herk M. Radiation dose to heart base linked with poorer survival in lung cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2017;85:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Contreras J, Lin A, Weiner A, Speirs C, Samson P, Mullen D, et al. Cardiac dose is associated with immunosuppression and poor survival in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2018;128(3):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNew L, Bowen S, Gopan O, Nyflot M, Patel S, Zeng J, et al. The relationship between cardiac radiation dose and mediastinal lymph node involvement in stage III non-small cell lung cancer patients. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2017;2(2):192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming C, Cagney D, O’Keeffe S, Brennan S, Armstrong J, McClean B. Normal tissue considerations and dose–volume constraints in the moderately hypofractionated treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2016;119(3):423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landau D, Hughes L, Baker A, Bates A, Bayne M, Counsell N, et al. IDEAL-CRT: A phase 1/2 trial of isotoxic dose-escalated radiation therapy and concurrent chemotherapy in patients with stage II/III non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95(5):1367–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darby S, Ewertz M, McGale P, Bennet A, Blom-Goldman U, Brønnum D, et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(11):987–998. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1209825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dess R, Sun Y, Matuszak M, Sun G, Soni P, Bazzi L, et al. Cardiac events after radiation therapy: combined analysis of prospective multicenter trials for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(13):1395–1402. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.71.6142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speirs C, DeWees T, Rehman S, Molotievschi A, Velez M, Mullen D, et al. Heart dose Is an independent dosimetric predictor of overall survival in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(2):293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vivekanandan S, Fenwick JD, Counsell N, Panakis N, Higgins GS, Stuart R, Hawkins MA et al. Associations between survival and cardiac irradiation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a validation study. Radiother Oncol. 2021 (submitted) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Thor M, Deasy JO, Hu C, Gore E, Bar-Ad V, Robinson C, et al. Modeling the impact of cardiopulmonary irradiation on overall survival in NRG oncology trial RTOG 0617. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4643–4650. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McWilliam A, Khalifa J, Vasquez Osorio E, Banfill K, Abravan A, Faivre-Finn C, van Herk M. Novel methodology to investigate the effect of radiation dose to heart substructures on overall survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108(4):1073–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crosby T, Hurt C, Falk S, Gollins S, Mukherjee S, Staffurth J, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with oesophageal cancer (SCOPE1): a multicentre, phase 2/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):627–637. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng M, Moran J, Koelling T, Chughtai A, Chan J, Freedman L, et al. Development and validation of a heart atlas to study cardiac exposure to radiation following treatment for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(1):10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bridge P, Tipper DJ. CT anatomy for radiotherapy. 2. M & K Publishing; 2017. pp. 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenwick J, Landau D, Baker A, Bates A, Eswar C, Garcia-Alonso A, et al. Long-term results from the IDEAL-CRT phase 1/2 trial of isotoxically dose-escalated radiation therapy and concurrent chemotherapy for stage II/III non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106(4):733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.11.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoenfeld D. Sample-size formula for the proportional-hazards regression model. Biometrics. 1983;39(2):499. doi: 10.2307/2531021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freidlin B, Korn E. Biomarker enrichment strategies: matching trial design to biomarker credentials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;11(2):81–90. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsui S, Crowley J. Biomarker-stratified phase III clinical trials: enhancement with a subgroup-focused sequential design. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;24(5):994–1001. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park J, Hsu G, Siden E, Thorlund K, Mills E. An overview of precision oncology basket and umbrella trials for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(2):125–137. doi: 10.3322/caac.21600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nix M, Rowbottom C, Vivekanandan S, Hawkins M, Fenwick J. Chemoradiotherapy of locally-advanced non-small cell lung cancer: analysis of radiation dose–response, chemotherapy and survival-limiting toxicity effects indicates a low α/β ratio. Radiother Oncol. 2020;143:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomé W, Fowler J. On cold spots in tumor subvolumes. Med Phys. 2002;29(7):1590–1598. doi: 10.1118/1.1485060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giraud P, Antoine M, Larrouy A, Milleron B, Callard P, De Rycke Y, et al. Evaluation of microscopic tumor extension in non-small-cell lung cancer for three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy planning. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(4):1015–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00750-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe S, Yamada Z, Nishimoto Y, et al. Measurement of cardiac volume by computed tomography. J Cardiogr. 1981;11(4):1273–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer G, Capello K, Bearrs B, Lauzon A, Normandeau L. Linear dimensions and volumes of human lungs obtained from CT images. Health Phys. 2012;102(4):378–383. doi: 10.1097/hp.0b013e31823a13f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferris M, Martin K, Switchenko J, Kayode O, Wolf J, Dang Q, et al. Sparing cardiac substructures with optimized volumetric modulated arc therapy and intensity modulated proton therapy in thoracic radiation for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019;9(5):e473–e481. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giaddui T, Chen W, Yu J, Lin L, Simone C, Yuan L, et al. Establishing the feasibility of the dosimetric compliance criteria of RTOG 1308: phase III randomized trial comparing overall survival after photon versus proton radiochemotherapy for inoperable stage II-IIIB NSCLC. Radiat Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s13014-016-0640-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haslett K, Bayman N, Franks K, Groom N, Harden SV, Harris C et al. Isotoxic intensity modulated radiotherapy in stage III NSCLC—a feasibility study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Tucker SL, Liu A, Gomez D, Tang LL, Allen P, Yang J, et al. Impact of heart and lung dose on early survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2016;119(3):495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Supplementary Materials.

Data Availability Statement

Available on request from LT.