Abstract

There is an urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches to treat Alzheimer’s disease (AD) with the ability to both alleviate the clinical symptoms and halt the progression of the disease. AD is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides which are generated through the sequential proteolytic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP). Previous studies reported that Mint2, a neuronal adaptor protein binding both APP and the γ-secretase complex, affects APP processing and formation of pathogenic Aβ. However, there have been contradicting results concerning whether Mint2 has a facilitative or suppressive effect on Aβ generation. Herein, we deciphered the APP-Mint2 protein–protein interaction (PPI) via extensive probing of both backbone H-bond and side-chain interactions. We also developed a proteolytically stable, high-affinity peptide targeting the APP-Mint2 interaction. We found that both an APP binding-deficient Mint2 variant and a cell-permeable PPI inhibitor significantly reduced Aβ42 levels in a neuronal in vitro model of AD. Together, these findings demonstrate a facilitative role of Mint2 in Aβ formation, and the combination of genetic and pharmacological approaches suggests that targeting Mint2 is a promising therapeutic strategy to reduce pathogenic Aβ levels.

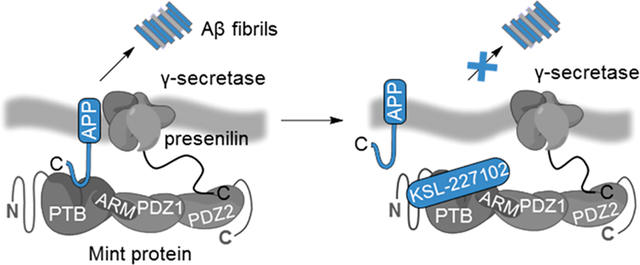

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides, the main component of senile amyloid plaques, play a key role in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis.1,2 Aβ peptides are generated by the sequential proteolysis of the amyloid precursor protein (APP),3 a type I transmembrane protein of 695–770 amino acids. In the pathogenic amyloid cascade, cleavage by an aspartyl protease (BACE-1 or β-secretase) generates a soluble APP ectodomain (sAPPβ) and a membrane-bound C-terminal fragment (C99). Subsequent cleavage of the C99 fragment by γ-secretase generates the APP intracellular domain (AICD) and Aβ fragments of various lengths, including Aβ40 and Aβ42. The latter exhibits an increased propensity to form insoluble aggregates, which are a hallmark of AD pathology.

The accumulation of Aβ peptides at synaptic sites has detrimental effects on synaptic function, which contributes to the cognitive decline and memory loss associated with AD.4 The most advanced anti-Aβ drugs in clinical development are anti-Aβ immunotherapies promoting clearance of the Aβ peptide and its aggregates or β-secretase inhibitors intended to interfere with the initial step of Aβ formation.5 However, both strategies have suffered from failure in late-stage clinical trials,6,7 and no disease-modifying AD therapy is yet available. Alternative strategies to reduce Aβ formation, such as the modulation of direct binding partners involved in APP trafficking and processing, could therefore increase the chance of developing a successful AD treatment, which is of increasing importance in light of a constantly growing patient population.8

Munc18-interacting proteins (Mints, also known as X11s) are a family of adaptor proteins encoded by three distinct genes (ABPA1, ABPA2, and ABPA3) that produce neuron-specific Mint1 (X11α) and Mint2 (X11β) and ubiquitously expressed Mint3 (X11γ).9–11 Mint proteins consist of a variable isoform-specific N-terminal region and a conserved C-terminal region that contains a phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain and two tandem PSD-95/discs large/zonula occludens (PDZ) domains (Figure 1a).12 The PTB domain of all three Mint proteins binds the conserved endocytic YENPTY motif of APP, which is essential for regulating APP trafficking and affects Aβ production.13–16 A number of studies suggest that the APP-Mint protein–protein interaction (PPI) is of particular biological significance in AD. First, the loss of each individual Mint isoform delays age-dependent Aβ plaque formation in mouse models of AD.17 Second, Mint proteins interact via their PDZ domains with presenilin-1, the catalytic subunit of the γ-secretase complex, thereby promoting APP/presenilin-1 colocalization favoring Aβ formation.18–21 Third, Mint proteins are found to be upregulated in AD and are reported to associate with neuritic plaques.22,23 Altogether, these findings indicate that the APP-Mint PPI is of therapeutic relevance to Aβ formation and AD. Efforts have been made to decipher the physiological role of Mint proteins in Aβ formation, and numerous knockout and knockdown studies, using mainly in vivo models, have been reported.17,20,24–30 However, these studies revealed both suppressive and facilitative effects of Mint proteins on Aβ formation. The role of Mint proteins in the formation of pathogenic Aβ remains controversial since no chemical probe perturbing the APP-Mint PPI has been reported.

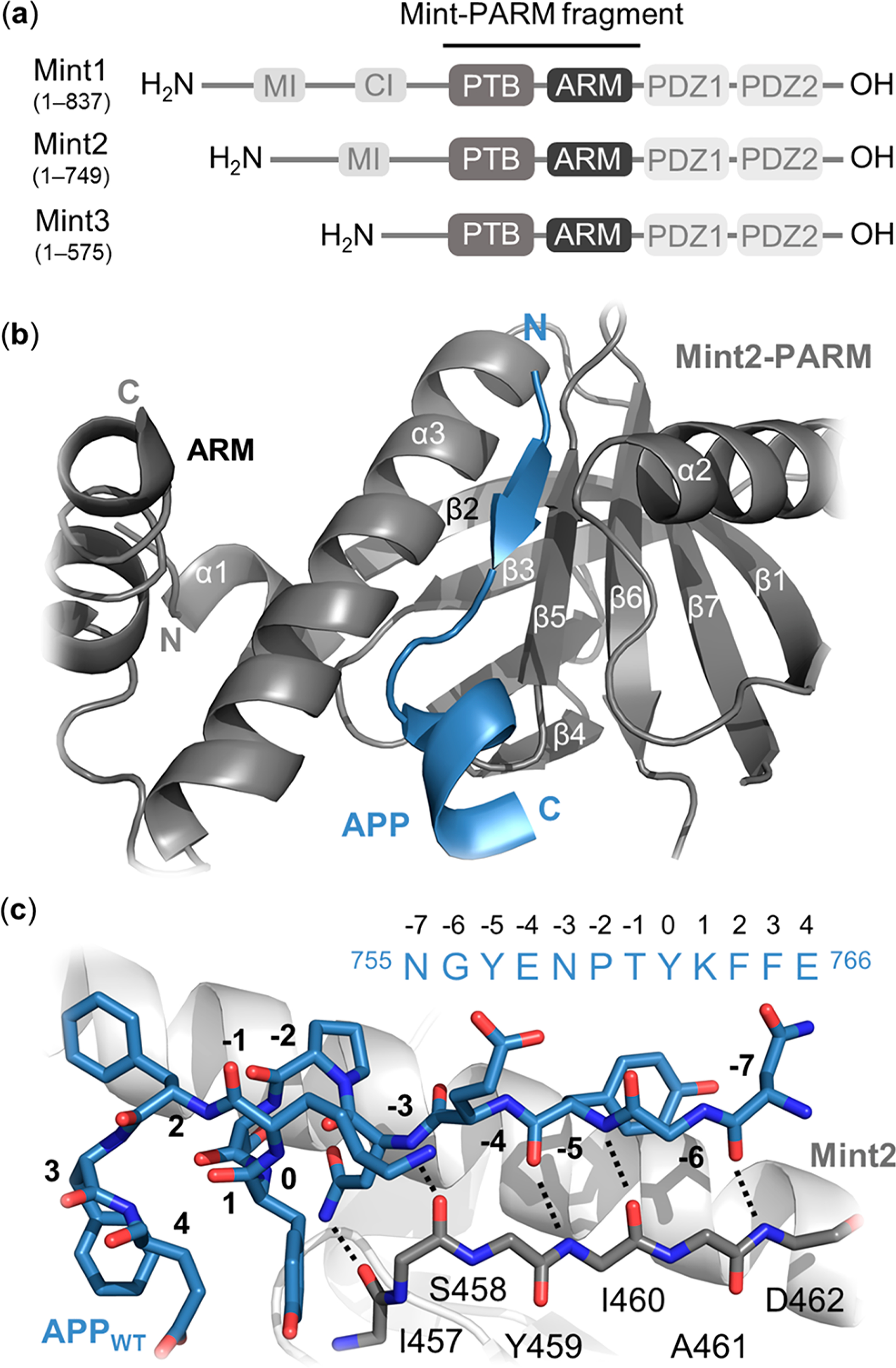

Figure 1.

Structural overview of the Mint protein family and the Mint2-APP interaction. (a) Schematic architecture of Mint proteins illustrating their conserved C-terminal region consisting of a phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain (gray), an α-helical ARM linker (dark gray), two PSD-95/drosophila discs large/zonula occludens (ZO-1) (PDZ) domains (light gray), and a variable N-terminal region. Numbering corresponds to human residues. MI = Munc-18 interaction domain, CI = CASK interaction domain. (b) Cartoon representation of the interaction between rat Mint2-PARM (gray) and APP (residues 754–767; blue). The APPC-term is binding at the interface between the α3-helix and β5-strand of Mint2, forming an antiparallel β-sheet (N-terminal) followed by a β-turn and a C-terminal α-helix. The ARM linker (dark gray) is found in an open conformation enabling APP binding. (c) Structure of the APP peptide (blue sticks) bound to the rat Mint2-PTB domain (gray). The β5-strand of the PTB domain (gray stick, side chains not depicted) is shown to highlight the backbone–backbone H-bond network (black dotted lines) between the Mint2-PTB domain and APP (PDB ID: 3SV1).12

Herein, we characterized the APP-Mint2 interaction with molecular resolution through extensive substitutional analyses of both the APP C-terminal peptide ligand (APPC‑term) and the Mint2 protein. The introduction of backbone amide-to-ester (A-to-E) modifications uncovered an intricate H-bond network at the APP-Mint2 interface, complementing previously published cocrystal structures. Alanine (Ala) substitutions in the PTB domain of Mint2 identified key residues and led to the generation of an APP binding-deficient Mint2 variant that reduced Aβ42 generation in vitro. Furthermore, we performed a systematic structure–function analysis of the APP C-terminal peptide which facilitated the development of a proteolytically stable macrocyclic peptide exhibiting nanomolar affinity toward Mint2. In a neuronal in vitro model of AD, cell-permeable variants of the high-affinity C-terminal APP mimetic peptide demonstrated that modulation of the APP-Mint2 interaction reduces Aβ42 levels.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Minimal APP Mint2-PARM Binding Sequence and Semisynthesis of Mint2-PARM Variants.

Within the Mint protein family, Mint2 exerts the greatest effect on Aβ formation and was therefore selected as the target protein.17 The interaction of APP and Mint2 is mediated by the PTB domain of Mint2 and modulated in an autoinhibited open–closed fashion by a C-terminal α-helical linker (termed ARM) adjacent to the PTB domain.12,31,32 Consequently, we designed a human Mint2-PTB-ARM (Mint2-PARM) construct (PARMHis6; residues 364–570) as a model protein (Figure 1a). To identify the minimal binding sequence of APP, we systematically tested N- and C-terminal truncated variants of the human 17-mer APPC‑term peptide (QNGYENPTYKFFEQMQN; residues 754–770 in APP770). Using a fluorescence polarization (FP) assay (SI section Detailed Methods), we identified a 12-residue-long peptide, designated as the APPWT peptide (NGYENPTYKFFE; residues 755–766; Ki = 4.0 ± 0.2 μM), as the minimal Mint2-PARM binding sequence (Figure S1 and Table S1).

The reported X-ray cocrystal structure of Mint2 and the APP peptide (QNGYENPTYKFFEQ; residues 753–767, Figure 1b, blue) suggests that an intricate network of backbone hydrogen bond (H-bond) interactions and side-chain interactions mediates the APP-Mint2 interaction (Figure 1c, dotted lines).12,14 Therefore, we probed side-chain interactions by introducing Ala substitutions, whereas backbone H-bond interactions can only be effectively probed by introducing A-to-E substitutions.33–37 While we generated Mint2-PARM Ala variants through recombinant expression (Table S2), introducing A-to-E substitutions into the Mint2-PARM domain required the development of a semisynthesis strategy. Specifically, we first generated a pseudo-wild-type Mint2-PARM variant (pPARM-His6; residues 364–570; R455K, C483A, C501A, C566A) containing three cysteine (Cys) to Ala substitutions enabling the use of native Ala residues in the native chemical ligation (NCL). Next, we synthesized the same version of Mint2-PARM semisynthetically (pPARMss; residues 364–570; R455K, C483A, C501A, C566A with no His tag) using a three-fragment expressed protein ligation (EPL) approach (Figure 2a). Both protein variants (pPARM-His6 and pPARMss) displayed similar secondary structure and binding affinity for the 17-mer APPC‑term peptide as recombinantly expressed Mint2-PARM (Figures S2 and S3), confirming that neither the His6-tag nor the introduced substitutions affect APP binding. We applied the semisynthetic strategy to introduce eight A-to-E substitutions (R455κ, T456τ, I457ι, S458σ, Y459ψ, I460ι, A461α, and D462δ; α-hydroxy amino acids abbreviated with Greek letters)38 into Mint2-pPARMSS (Tables S3 and S4), which were all obtained with sufficient yields and purities (Figures S4–S7).

Figure 2.

Semisynthesis of Mint2-PARM and effects of A-to-E and Ala mutations in APP and Mint2-PARM. (a) Semisynthetic approach to introducing A-to-E substitutions in Mint2-PARM. N-terminal fragment PARMN (A479-Q570) is fused to a Xa site to generate an N-terminal Cys by factor Xa cleavage. C-terminal fragment PARMC (E364-H452) is expressed with a C-terminal intein to generate the required C-terminal thioester. Semisynthesis is initiated by ligating synthetic peptide fragment PARMpep to PARMN. Next, the Thz group is converted to a free Cys and PARMpep+N is ligated to PARMC. Semisynthetic Mint2-pPARMSS is obtained after desulfurization and refolding (Figures S2–S7). (b) Affinity fold-change of the APPWT peptide’s Ala-scan and (c) A-to-E substitutions toward Mint2-PARM obtained in an inhibition FP assay (Ki) reported relative to the APPWT peptide [Ki(mutant)/Ki(APPWT) + SEM]. (d) Affinity fold change of the APPC‑term peptide binding to Mint2-PARM Ala and (e) A-to-E variants obtained by the saturation FP assay (Kd) relative to Mint2-PARMWT [Kd(variant)/Kd(wild type) + SEM]. See Figures S8 and S9 for FP data.

Similarly, we introduced A-to-E substitutions in five positions of the APPWT peptide (G756γ, Y757ψ, E758ε, N759ν, and F764ϕ). The corresponding depsi-peptides were synthesized on the solid phase using α-hydroxy amino acids (SI section Detailed Methods).39,40 It is generally accepted that A-to-E substitutions do not perturb the overall protein structure.41 However, the H-bond donor ability of the respective amide-NH is removed and the acceptor capability of the adjacent carbonyl is reduced, which provides a refined tool for studying H-bond networks. A-to-E mutations have successfully been employed to address the significance of backbone H-bonds for folding β-sheet structures and backbone H-bonds in Aβ peptides.38,42–44

In total, 21 Mint2-PARM protein variants containing both Ala and A-to-E substitutions and 17 APPWT peptide analogues were generated. We then employed the FP assay to address the consequences of each substitution on the APP-Mint2 interaction (Figure 2b–e).

Backbone H-Bonds and Side-Chain Contacts Are Essential to the APP-Mint2 Interaction.

Single-point Ala substitutions in the APPWT peptide resulted in a >10-fold loss of affinity to Mint2-PARM in 4 out of 12 positions (Figure 2b, Figure S8a,b, and Table S1). The substitution of two residues, Y757A and N759A located in the endocytic YENPTY motif of APP, resulted in 76-fold and >100-fold decreases in affinity, respectively. In addition, Ala substitution of residues F764 and F765 resulted in 14- and 18-fold decreases in affinity, respectively (Figure 2b). The N-terminal region of the APP peptide forms an antiparallel β-sheet with the β5 strand of Mint2-PARM. On the basis of the X-ray cocrystal structure, H-bond interactions that formed between the APP peptide and Mint2 were probed by A-to-E substitutions (G756γ, Y757ψ, E758ε, and N759ν) (Figure 1c). All four A-to-E substitutions resulted in a reduced binding affinity relative to the APPWT peptide (Figure 2c, Figure S8c,d, and Table S1). Interestingly, the Y757ψ substitution exhibited a >100-fold loss of affinity to Mint2-PARM, as did the Y757A substitution, rendering Y757 as a key residue in APP.

In Mint2-PARM, three Ala substitutions (L454A, Y459A, and F520A) exhibited a >10-fold reduction in the APPC‑term affinity (Figure 2d, Figure S9, and Table S2). The robust effect of Y459A substitution in Mint2-PARM is likely a result of disrupting the hydrophobic interaction with the Cα atom of G756 in APP, an interaction also reported for Mint1 (Y418).14 Notably, F520A substitution in Mint2-PARM led to a 45-fold reduction in binding affinity, plausibly explained by contacts with key residue N759 in APP (Figure S10a). Corresponding residues in the PTB-domains of Mint1 (F608) and p52 Shc (F198) are also reported to be important for peptide recognition, suggesting that the conserved Phe constitutes an important mediator of ligand recognition for PTB domains.13,45 Next, we evaluated the effect of A-to-E substitutions in Mint2-PARM on the binding to the APPC‑term peptide. In general, the introduced substitutions reduced the binding affinity of the APPC‑term peptide by 2- to 4-fold (Figure 2e and Table S4). However, two A-to-E substitutions, S458σ and D462δ, resulted in 14- and 25-fold reduced affinities, respectively. Both residues engage in H-bonds and form the antiparallel β-sheet with the N-terminal region of the APPC‑term peptide (Figure 1b,c). Altogether, we identified two key side chains (Y757 and N759) and one backbone amide (Y757ψ) in APP to be critical to the APP-Mint2 interaction. In the Mint2-PTB domain, we found F520A, Y459A, and one backbone amide substitution (D462δ) led to a substantial reduction in affinity to the APPC‑term peptide (Figure 2d, e).

Compared to the reported cocrystal structure of APP and Mint2, we observed a number of deviations from the suggested interactions. First, the side chains of D462 in Mint2 and Y757 in APP are suggested to interact via an H-bond. In our FP measurements, we detected no effect of the D462A mutation in Mint2-PARM on the binding of the APPC‑term peptide (Figure 2d); however, we cannot exclude that the Ala mutation can be compensated for by a water molecule mimicking the H-bond acceptor of D462. Second, Q767 of APP is proposed to H-bond to N387 in Mint2, although the truncated APPWT peptide lacking Q767 retains a wild-type binding affinity (Figure S1). Finally, the side chain of the critical N759 residue in APP is proposed to bind the backbone carbonyls of both L454 and I457 in Mint2.14 Here, our A-to-E substitutions suggest that only the H-bond protruding from I457 of Mint2 is important, while perturbing the carbonyl of L454 had only minor effects on the affinity to the APPC‑term peptide (Figure 1c).

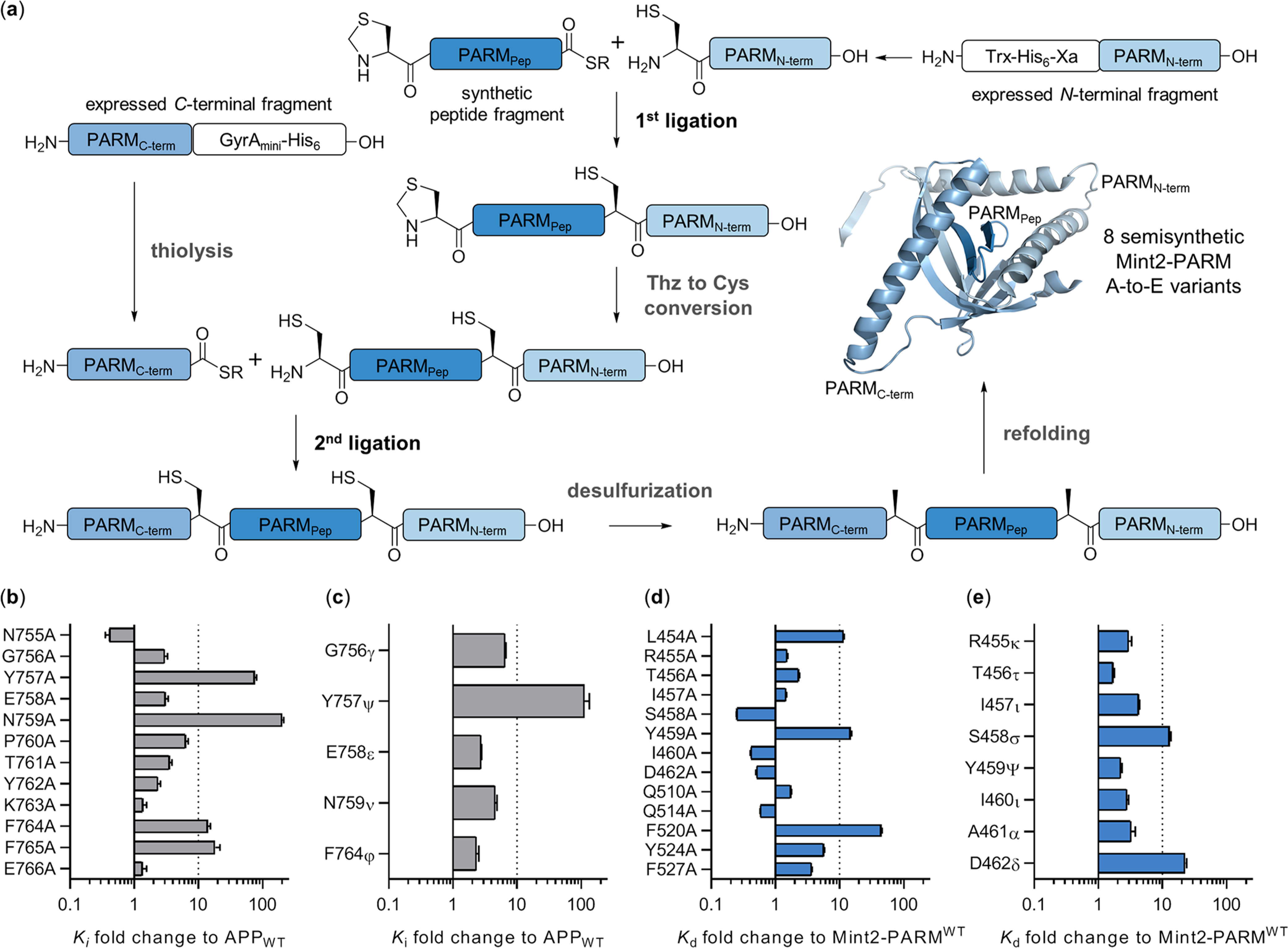

Mutations in the Mint2-PTB Domain Reduce APP Binding and Aβ Formation.

We took advantage of the Mint2-PARM Ala-scan results and designed a Mint2 variant with reduced APP binding affinity. Introducing two mutations, Y459A and F520A, into human Mint2-PARM (hMint2Y459A/F520A) resulted in a significant 72-fold decrease in the APPC‑term peptide binding affinity (Kd = 895 ± 43 μM) in the FP assay (Figure 3a and Figure S10). To examine whether hMint2Y459A/F520A has a cellular effect on APP binding, we produced a full-length GFP-tagged rat Mint2 (GFP-rMint2WT) and corresponding APP binding-deficient variant GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A (analogous to hMint2Y459A/F520A, Figure S11). We confirmed our FP results by cotransfecting HEK293T with full-length APP and either GFP-rMint2WT or GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A and performing coimmunoprecipitation assays. APP coimmunoprecipitated with both GFP-rMint2WT (lane 5, Figure 3b) and GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A (lane 6, Figure 3b); however, GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A exhibited a significant 85% reduction in APP binding (Figure 3c). Next, we examined the functional effect of an impaired interaction between APP and Mint2 on Aβ generation. We employed primary cortical neurons from an established murine AD model with a double transgene for the expression of mutant APP (APPswe) and presenilin-1 proteins (PS1ΔE9), resulting in enhanced Aβ production.17 We infected primary neurons with a full-length GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A lentivirus after 2 days in vitro (2 DIV). Expression of the GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A variant was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 3d). We quantified the effect on Aβ42 levels released from primary neurons using an enzyme-like immunosorbent assay (ELISA) on the neuronal conditioned medium. At 15 DIV, we observed a significant 42% decrease in Aβ42 levels in neurons infected with GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A relative to neurons expressing only endogenous Mint2 (Figure 3e). Together, our results confirm that APP interacts with the PTB domain of Mint2 and suggest that Mint2 plays a facilitative role in Aβ formation in our neuronal AD model.

Figure 3.

APP binding-deficient rMint2Y460A/F521A variant reduces Aβ42 levels in primary mouse neurons. (a) APPC‑term peptide affinity for selected Mint2-PARM variants. Data are expressed as the mean + SEM (n = 3). The statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, **** P < 0.0001 (Figure S10). (b) Coimmunoprecipitation of APP with the Mint2 antibody from HEK293T cells cotransfected with APP and GFP-rMint2WT or GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A. Western blotting indicates less APP binding to rMint2Y460A/F521A (lane 6) than to GFP-Mint2WT (lane 5). α-Tubulin served as a loading control. (c) Quantification of APP coimmunoprecipitation using GFP-rMint2WT and GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A. Data were normalized to GFP-rMint2WT and expressed as the mean + SEM. The statistical significance was evaluated with the Student’s t-test, *** P < 0.001. (n = 4 independent experiments). (d) Western blot for Mint2, APP, and α-tubulin from neuronal lysates carrying the APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mutation and infected with the lentiviral GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A mutant. (e) Aβ42 ELISA quantification of conditioned media from neurons overproducing Aβ shows reduced Aβ42 levels when neurons were infected with the GFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A mutant. Data were normalized to the endogenous Mint2WT control and expressed as the mean + SEM (n = 7 biological replicates from two independent experiments). The statistical significance was evaluated using the Student’s t-test, *** P < 0.001.

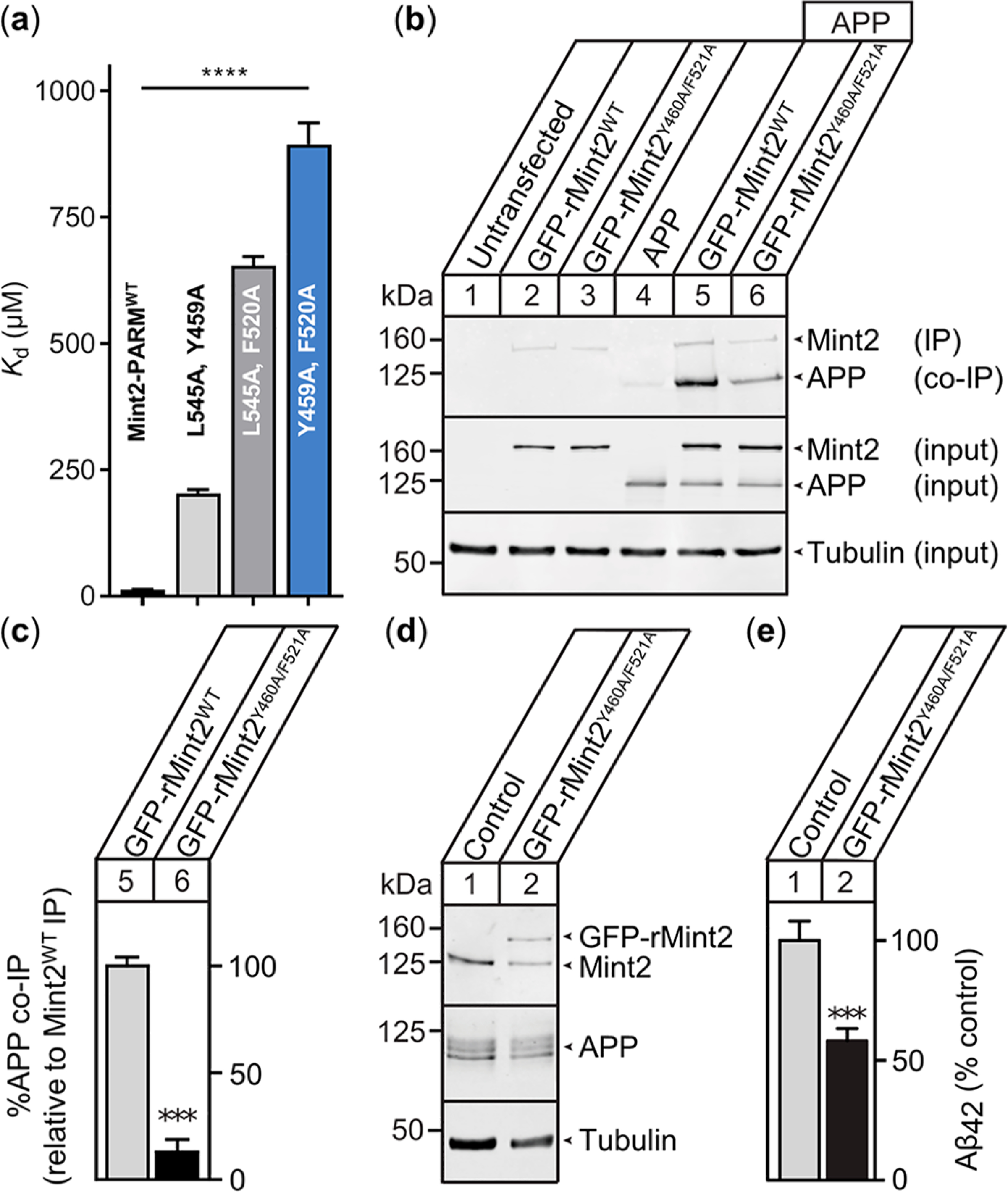

Non-canonical Amino Acids Enhance the Binding of the APP Peptide to Mint2.

Since the APP binding-deficient rMint2Y460A/F521A variant reduced Aβ production in vitro and previous studies revealed that Mint2 knockout in APPswe/PS1ΔE9 transgenic mice reduces Aβ formation in vivo, we hypothesized that a peptide-based inhibitor designed to disrupt the APP-Mint2 interaction could reduce Aβ generation. As such, we used the APPWT peptide as a template for an initial D-and N-Me-amino acid (d-AA and NMe-AA) scan (Figure S8 and Table S1). D-AAs were tolerated only in the N- and C-termini of the APPWT peptide, whereas the N-methylation of N755 resulted in an improved affinity toward Mint2-PARM. Notably, the substitution of Y757 with N-MeY757 resulted in a nonbinding APPWT peptide analogue, which is in agreement with the reduced binding of the Y757ψ analogue (Figure 2c). Next, we prepared a series of APPWT peptide variants containing single substitutions of both canonical (cAAs) and noncanonical amino acids (ncAAs) (Figure 4a). First, we tested position N759, the most critical residue according to the Ala scan, and introduced eight different amino acids. Remarkably, all substitutions, even conservative ones such as N759Q, abrogated the binding to Mint2-PARM (Ki ≥ 500 μM) (Figure 4b). We therefore consider N759 to be a key residue in the APP-Mint2 interaction, which is further supported by its conservation as part of the APP endocytic NPXY consensus sequence that interacts with the PTB domain of Mint proteins.46 Next, we probed the two aromatic residues, F764 and F765. Individual substitution by Trp had no effect on the affinity. In contrast, the incorporation of l-3-(1-naphtyl)alanine (Nal1) at either position improved the affinity for both variants, and the corresponding double substitution showed a 4-fold improvement in affinity (Ki = 1.1 ± 0.3 μM). We attribute the improved affinity to hydrophobic interactions with Y524 and F527 in Mint2-PTB located in close proximity to F764 and F765. Neither l-3-(2-naphtyl)alanine (Nal2) nor 2-indanyl-L-glycine (Igl) improved the affinity to the same extent (Figure 4b).

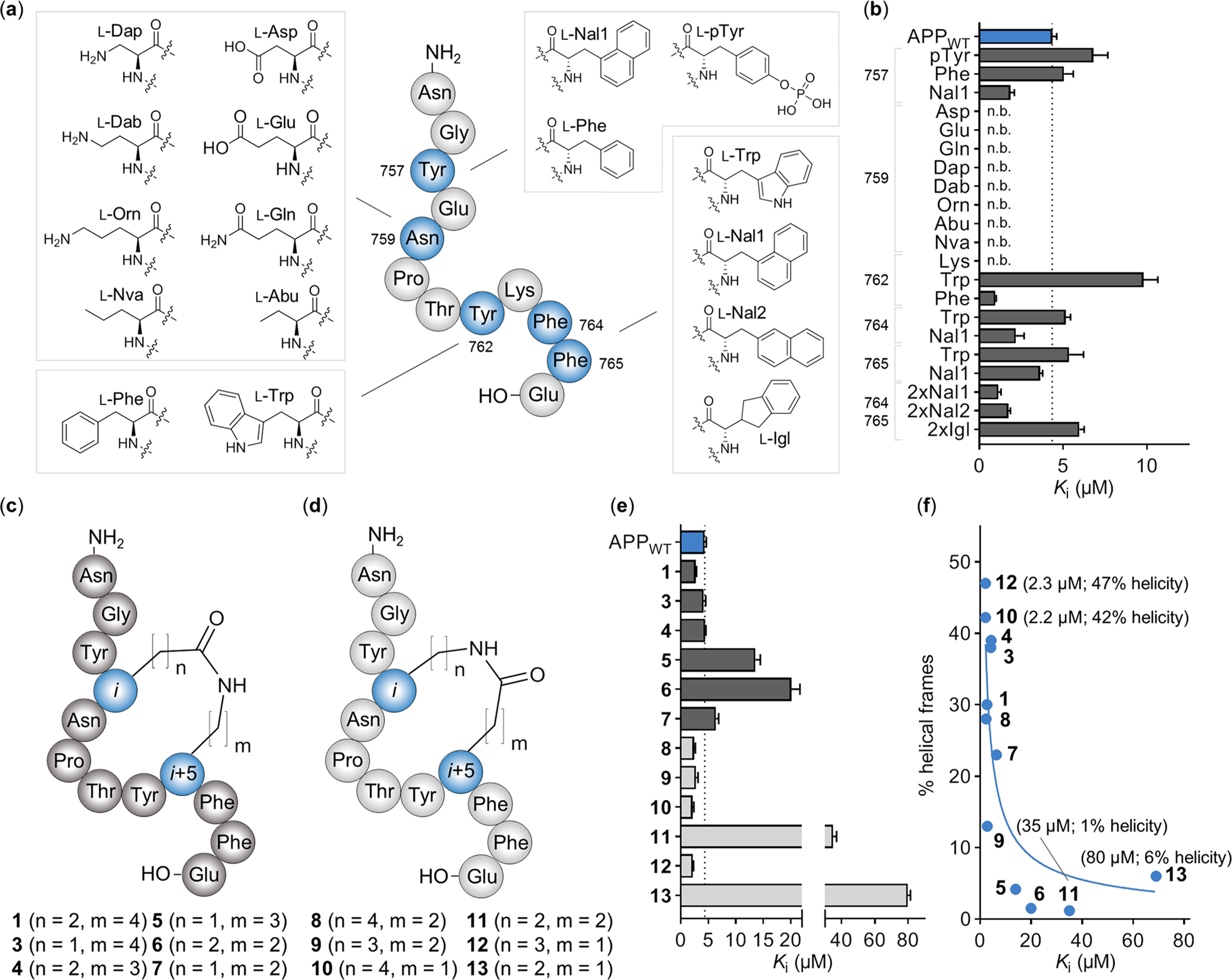

Figure 4.

Incorporation of ncAAs and evaluation of side chain-to-side chain macrocyclization in the APPWT peptide. (a) Overview of synthesized APPWT peptide variants, including the structure of the introduced amino acids for each position (blue). (b) Ki values of each APPWT peptide variant measured by FP. n.b. indicates nonbinding peptide (i.e., Ki ≥ 500 μM). Data are expressed as the mean + SEM (n = 3). (c) Structure of side chain-to-side chain cyclized APPWT peptide analogues with native residue order (Glu in the i position, dark gray) and (d) inverse residue order (Lys in the i position, light gray). (e) Ki values of cyclic APPWT peptide variants measured by FP. Data are expressed as the mean + SEM (n = 3). (f) Helical propensity of residues Y762 to E766 from the molecular dynamics simulation of cyclic APPWT peptide variants 1 and 3–13 (% helical frames) plotted against the binding affinity (the mean Ki value) including the trend line (blue).

Finally, the substitution of Y762 to Phe resulted in a 4-fold increase in affinity (Ki = 1.0 ± 0.1 μM), while an Y762W substitution lowered the affinity to Mint2-PARM (Figure 4b and Table S1).

Taken together, we identified six positions (N755, Y757, Y762, F764, F765, and E766) in the APPWT peptide at which substitutions to cAAs or ncAAs either improved the affinity or were expected to improve the proteolytic stability of the peptide.

Side Chain-to-Side Chain Cyclization in the APPWT Peptide Improves Affinity and Stability.

To improve the binding and metabolic stability of our peptide ligand, we introduced side chain-to-side chain lactam cyclizations employing solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) and on-resin cyclization (Figure S12a). According to the reported X-ray cocrystal structure of APP-Mint2, native residues E758 and K763 are in close proximity when forming an intramolecular noncovalent salt bridge (Figure S12b).12 We reasoned that introducing a lactam bridge in this position could confer conformational constraint and potentially improve the affinity and stability.47 Indeed, a cyclic analogue of the APPWT peptide containing a lactam linkage between E758 and K763 (i to i + 5, cAPPE758–K763; 1) exhibited improved affinity compared to the APPWT peptide and was also superior to a variant cyclized between Y762K and E766 (i to i + 4, cAPPY762–E766; 2) (Figure S12b–d). Next, we prepared a series of cyclic variants of 1 in which we systematically modified the lactam bridge by introducing Asp, Orn, or Dap and reversed the orientation of the amide bond in the lactam bridge (Figure 4c,d). The affinity of these 11 peptides (3–13) was highly dependent on the nature of the introduced macrocyclization (Figure 4e).

In general, macrocyclic peptides with carboxylic acid side chains in i positions (1 and 3–7; Figure 4c) were characterized by reduced binding affinities, while peptides with amino side chains in i positions (8–13, Figure 4d) displayed improved affinities relative to the linear APPWT peptide. Furthermore, smaller ring sizes (5–7, 11, and 13) resulted in reduced binding affinities with only peptide 12 (n = 3, m = 1) refuting this trend. Among the 12 macrocycles, peptide 10 (n = 4, m = 1) exhibited the highest affinity (Ki = 2.2 ± 0.3 μM) (Figure 4e). To test whether macrocyclization improved the proteolytic stability, cyclic peptide 1 was tested in an in vitro human plasma stability assay, resulting in a 4-fold-improved half-life time (T1/2) over the APPWT peptide, T1/2 = 105 and 26 min, respectively (Figure S12e).48

On one hand, the moderately improved affinity might be a result of the introduced constrain causing a preorganization of the peptide resembling the bound conformation with a well-defined helical turn of residues Y762–E766, which reduces the entropic penalty upon binding. On the other hand, additional favorable interactions by the formed lactam bridge can also account for the improved affinity. We performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of cyclized peptides 1 and 3–12 and found a correlation between the degree of helicity in solution and the observed binding affinities. For the two most potent cyclic peptides 10 and 12, helical propensity predictions of 42 and 47%, respectively, were observed. In contrast, for low-affinity peptides 11 and 13 the molecular dynamics simulations suggested helical propensities of 6% and less (Figure 4f). This suggests that ligand preorganization is the driving force of the improved binding. Altogether, the systematic lactam macrocyclization scan led to the identification of a cyclic APPWT peptide scaffold with improved binding affinity and proteolytic stability.

Identification of a Metabolically Stable, High-Affinity Mint2 Inhibitor Derived from the APPWT Peptide.

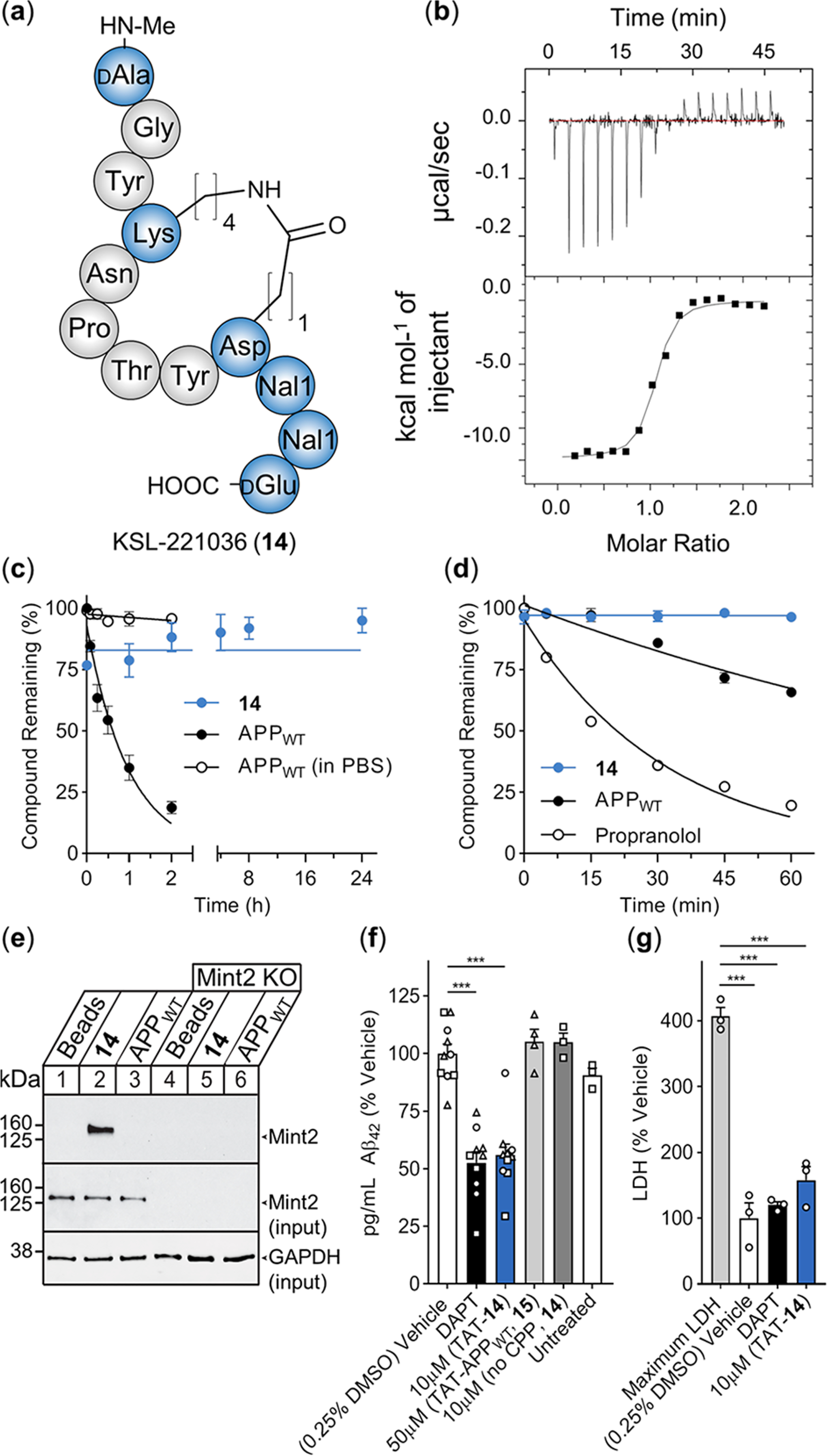

To develop a potent and proteolytically stable modulator of the APP-Mint2 PPI, we selected cyclic peptide 10 (n = 4, m = 1) as a scaffold. Next, we introduced d-N-Me-Ala and d-Glu at positions 755 and 766, respectively. Finally, ncAA L-Nal1 was selected for positions 764 and 765. The corresponding peptide, KSL-221036 (NMe-aGYcyclo-[KNPTYD]Nal1Nal1e-OH, 14), was generated through SPPS including on-resin cyclization via orthogonally protected Lys(Aloc) and Asp(All) (Figure 5a). We found that 14 binds Mint2-PARM with nanomolar affinity (Kd = 53 ± 2 nM) as determined by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Compared to the APPWT peptide (Kd = 2.4 μM), a 46-fold improved affinity was achieved (Figure 5b and Figure S13). Furthermore, 14 was found to be proteolytically stable over 24 h (half-life ≥ 1440 min) in human plasma (Figure 5c), while the APPWT peptide exhibited a half-life of <30 min. Finally, we examined the rate of metabolism through cytochrome P450 enzymes using mouse liver microsomes and determined the in vitro hepatic clearance of the APPWT peptide and 14. We found the APPWT peptide was cleared fast [CL(int) = 15.4 ± 2.5 μL/(mg min)] while 14 was not metabolized over 60 min [CL(int) = 0.0 ± 0.8 μL/(mg min)] (Figure 5d). This data demonstrates the design of a peptide using the minimal binding sequence of the endogenous APP peptide–ligand as a template. Macrocyclization and the incorporation of selected ncAAs resulted in the design of KSL-221036 (14), the first reported modulator of the APP-Mint2 PPI exhibiting nanomolar affinity and suitable stability characteristics for further studies.

Figure 5.

PPI inhibitor of the APP-Mint2 interaction reduces Aβ42 production in the neuronal in vitro model of AD. (a) Schematic structure of KSL-221036 (14). (b) Representative ITC of titrating Mint2-PARM with 14; raw heat signature (top) and integrated molar heat release (bottom). (c) In vitro plasma stability of 14 (blue) and the APPWT peptide (black) including buffer control for the APPWT peptide (circles); data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). (d) In vitro hepatic clearance of 14 (blue) and the APPWT peptide (black) including propranolol control (circles, n = 1); data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). (e) Representative pull down of Mint2 from neuronal cell lysate (15 DIV). Lanes 1–3: expression of Mint2. Lanes 4–6: knockout of Mint2. The eluent was resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for Mint2 and GAPDH (n = 3). (f) Aβ42 ELISA quantification from conditioned media of neurons overproducing Aβ; data are normalized to the vehicle control and expressed as the mean + SEM (n = 3 independent experiments, n = 10 biological replicates for the vehicle, DAPT, and TAT-14 (10 μM). Independent experiments are represented by different shapes. Statistical significance evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, ***P < 0.001. (g) LDH levels from conditioned medium of cultured neurons overproducing Aβ collected after 24 h of treatment with DAPT and TAT-14 (10 μM). Maximum LDH represents the maximum amount of LDH released from neurons lysed using detergent. Individual data points in (g) correspond to data in panel (f) (circles = same assay). Data are expressed as %LDH normalized to vehicle control and shown as the mean + SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test, ***P < 0.001.

KSL-221036 (14) Interacts with Mint2 and Reduces Aβ Levels.

To determine whether KSL-221036 (14) binds full-length Mint2 from primary neuronal lysate, we loaded the APPWT peptide and 14 onto epoxy-coated magnetic beads via an N-terminal Cys-PEG linker (Table S1). Pull-down from the lysate of primary mouse neurons confirmed that 14 efficiently interacts with endogenous Mint2 at higher affinity (lane 2, Figure 5e) than for the APPWT peptide under the same conditions (lane 3, Figure 5e; see also Figure S14).

To examine the effect of 14 on Aβ42 production in neurons, we attached cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) TAT47–57 (YGR- KKRRQRRR)49 to the N-terminus of 14 (TAT-14) and the APPWT peptide (15, Table S1). TAT is a widely used CPP and was recently demonstrated to be compatible with late-stage clinical development in two phase III clinical trials (ESCAPE50 and FRONTIER), rendering TAT the most advanced CPP tag in the clinic. We first treated neurons with a concentration curve of peptide TAT-14 to determine the highest concentration at which no adverse effect on cell viability was observed. Using primary neurons and a colorimetric readout of metabolic activity, peptides 14 (no CPP) and 15 (TAT-APPWT) exhibited no adverse effect while peptide TAT-14 affected cell viability at 20 μM (75%) but had no measurable effect at 10 μM (Figure S15). To determine whether modulation of the APP-Mint2 interaction affects Aβ production, primary cortical neurons (14 DIV) carrying a double transgene for the expression of mutant APP (APPswe) and presenilin-1 proteins (PS1ΔE9) were incubated for 24 h with peptides 14, TAT-14, and 15. ELISA quantification of Aβ42 from the conditioned medium revealed that TAT-14 (10 μM) led to a 44% reduction of Aβ42 levels relative to vehicle control. In contrast, TAT-APPWT (15, 50 μM) and 14 (10 μM, no CPP) did not affect Aβ42 levels. High-affinity γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT (N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-s-phenyl-glycine tert-butyl ester or LY-374973) served as a positive control, reducing Aβ42 levels by 47% (Figure 5f and Figure S16).51 In addition, we assessed the effect of TAT-14 on cellular integrity by quantifying lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release (a proxy for cytotoxicity) in the same conditioned medium used for the aforementioned ELISA. We found low LDH levels for both DAPT- and TAT-14-treated neurons relative to vehicle control, indicating that the effect of peptide TAT-14 on Aβ production is not due to cellular toxicity (Figure 5g; see also Figure S16). Furthermore, p-value analysis found no significant difference between the vehicle and TAT-14 (p = 0.2448) or DAPT and TAT-14 (p = 0.6525) LDH release. To further support the TAT-mediated intracellular delivery of 14, we detected TAT immunostaining in primary neurons incubated with TAT-14 (Figure S17), indicating that TAT-14 is cell-permeable.

Following the promising Aβ42 results of TAT-14, we investigated the dose–response relationship and found a weak correlation between the concentration of TAT-14 and reduced Aβ42 levels (Figure S16e). We reasoned that the delivery efficiency of the cargo potentially depends on the employed CPP tag; therefore, we synthesized four additional variants of 14 containing different CPPs attached to the N-terminus: mixTAT-14 (rRrGrKkrK-14), polyArg-14 (RRRRRRRRR-14),52 D-SynB3-14 (frrrsyslrr-14),53 and MiniAp4-14 (cyclo(DLATEPAK(Dap)-14).54 Next, we determined the highest concentration at which no adverse effect on cell viability was observed. Peptide MiniAp4-14 exhibited no toxicity, while peptides mixTAT-14 and polyArg-14 were tolerated at concentrations of 5 and 7.5 μM, respectively (Figure S15). Peptide D-SynB3-14 was poorly soluble and not further tested. The peptides’ effect on Aβ formation was evaluated analogously to that of peptide TAT-14. The quantification of Aβ42 from the conditioned medium of primary neurons revealed that incubation with mixTAT-14 (5 μM) and polyArg-14 (5 μM) reduced Aβ42 levels by 80 and 84%, respectively. In contrast, incubation with MiniAp4-14 (10 μM) did not affect Aβ42 production (Figure S16c). Of note, we detected a small increase in LDH activity following incubation with mixTAT-14 (5 μM) compared to the vehicle control (Figure S16d). Consequently, polyArg-14, which reduced Aβ42 production at a lower concentration (5 μM) with minimal cellular toxicity, is a promising CPP alternative to TAT-14.

Our results indicate that peptide 14 successfully binds Mint2 in vitro with greater affinity than the APPWT peptide. Further studies in primary neurons cultured from our AD mouse model revealed that TAT-14 significantly decreases Aβ42 production with minimal toxicity. Further investigation into alternative CPPs showed that polyArg also provides attractive properties that facilitate the cellular uptake of peptide ligand 14. The observation that TAT-APPWT (15) has no effect on Aβ42 formation is in excellent agreement with the pull-down results and highlights the importance of ligand optimization. According to the reported effects of Mint knockout on APP trafficking and Aβ42 formation,21 inhibition of the Mint2-APP PPI by compounds TAT-14 and polyArg-14 could either result in reduced APP endocytosis or prevent the formation of the tertiary protein complex comprising APP (C99), Mint2, and the γ-secretase. Both avenues ultimately result in reduced Aβ formation. As such, the lowered Aβ42 levels seen in the in vitro AD model following treatment with compounds TAT-14 and polyArg-14 provide evidence that modulation of the APP-Mint2 PPI might serve as a pharmacological strategy to reduce pathologic Aβ levels in connection with AD.

CONCLUSIONS

In the pursuit of novel strategies to treat AD, pharmacological approaches modulating direct binding partners involved in APP trafficking and processing are promising alternatives to currently pursued therapies. Here, the APP-Mint PPI is an attractive target as the effects of Mint deletions are relatively mild, and our strategy, which selectively inhibits APP binding to the PTB domain of Mint proteins, would likely not interfere with the critical function of Mint proteins in synaptic vesicle exocytosis,17 which is mediated through Mint’s other PPI domains.9 Although numerous studies have examined the biological importance of Mint proteins, particularly with regard to Aβ formation in the context of AD,30 these studies have been informative but contradictory.55

Here, we extensively characterized the APP-Mint2 interaction at the molecular level by performing comprehensive mutational scans of the APP-Mint2 interface, covering both side-chain and backbone interactions. Compared to the reported structures, we observed distinct differences and showed that two backbone alterations, Y757ψ in the APPWT peptide and D462δ in Mint2, had major impacts on the APP-Mint2 interaction. The introduction of Ala substitutions demonstrated that the side chains of two residues in APP, N759, and Y757 and one residue in Mint2, F520, are pivotal to the APP-Mint2 interaction. These observations led to the generation of a Mint2 variant containing two distinct substitutions, Y459A/F520A, which resulted in impaired APP binding. We showed that reduced APP binding results in significantly reduced Aβ production, which supports a facilitative role of Mint2 in Aβ formation and suggests that targeting the APP-Mint2 interaction with a PPI inhibitor is of potential therapeutic relevance.

Using the APPWT peptide as a template, we developed a high-affinity, proteolytically stable cyclic peptide 14. We demonstrated that introducing noncanonical amino acids, N-methylation, and D-amino acids into a macrocyclic peptide scaffold provided a vast improvement in affinity for Mint2 and stability relative to the APPWT peptide. Notably, compared to APPWT, peptide 14 exhibited an enhanced affinity to robustly pull down full-length Mint2 from neuronal lysate. We confirmed that targeting the Mint2-APP interaction with cell-permeable variants of 14 (TAT-14 and polyArg-14) significantly reduced Aβ42 formation, whereas parent APPWT peptide 15 had no effect on Aβ42 formation. Peptides TAT-14, mixTAT-14, and polyArg-14 therefore provide first proof-of-concept evidence that targeting a direct interaction partner of APP affects its metabolism and Aβ formation. Furthermore, the comparison of different CPP tags indicates that the selection is critical and affects not only efficacy but also neuronal viability. Here, the combined analysis of LDH levels and Aβ42 reduction suggests that polyArg-14 might be preferred over TAT-14 (Figure S16).

Previous work has shown that APP and BACE-1 converge in acidic microdomains.56,57 Because the BACE-1 cleavage of APP is the rate-limiting step in Aβ production,58 this convergence in endosomes is a critical initiator of the APP amyloidogenic cascade. Sullivan et al. reported that the knockout of Mint proteins resulted in reduced APP endocytosis and Aβ formation.21 We suspect that the APP binding-deficient rMint2Y460A/F521A variant and TAT-, mixTAT-, and polyArg-14 could have a similar effect. The same study reported that the knockout of Mint proteins also affects the internalization of presenilin-1 of the γ-secretase complex and reduced colocalization with APP.

The impaired binding of APP (C99 fragment) to Mint2 and presenilin-1 would reduce the probability of γ-site cleavage in APP and hence Aβ formation. Our results encompass both observations.

In summary, we demonstrated that targeting the APP-Mint PPI may present an alternative strategy in the pursuit of new therapeutic approaches in AD treatment. We believe that the compounds reported herein will be of help in identifying mechanisms of Mint2-mediated Aβ formation and enable future in vivo studies.

METHODS

Detailed experimental procedures are provided in the Supporting Information.

Peptide Synthesis.

Peptides and depsipeptides were assembled in a manual or automated manner (LibertyBlue, CEM, Matthews, NC, USA) on a solid support using Boc- or Fmoc-based chemistry, purified by RP-HPLC, and characterized by LCMS and UPLC. When relevant, side-chain cyclization was performed on resin by the deprotection of Alloc and Allyl protecting groups, followed by PyBOP-induced cyclization.

Protein Expression.

Human Mint2 constructs were cloned in pRSET, pET, or pTXB1 vectors, expressed in E. coli Bl21(DE3)pLysS (Invitrogen), and purified using HisTrap columns, followed by size-exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg column or purification by reverse-phase chromatography (C4 column, YMC-Pack-C4, 250 × 20 mm2).

Expressed Protein Ligation.

The three-step ligation was initiated by ligating PARMN to the thioester peptide (PARMPep) fragment. Following buffer exchange, the second ligation was performed using the PARMC fragment. Obtained proteins were purified using a reverse-phase C4 column (Jupitor, Phenomenex, 250 × 10 mm2). After desulfurization, the semisynthetic protein was refolded into storage buffer and characterized by LCMS and UPLC.

Circular Dichroism (CD).

Experiments were performed on an Olis DSM 100 (Olis Inc.) at 15 μM protein concentration, and the obtained millidegrees of ellipticity (mo) was converted to the mean residue ellipticity (θMRE).

ThermoFluor.

ThermoFluor experiments were performed in a 96-well plate format on a Stratagene Mx3005p qPCR cycler (Agilent) using SYPRO orange as the dye at 15 μM protein concentration.

Fluorescent Polarization (FP).

Saturation binding (for semisynthetic and mutated proteins) using 50 nM TAMRA-APPC-term [(TAMRA)-NNG-QNGYENPTYKFFEQMQN] as a probe was performed using a Safire2 plate reader (Tecan) and increasing concentrations of Mint2-PARM. Inhibition experiments were performed using 50 nM TAMRA-APPC-term and 15 μM Mint2-PARM at increasing concentrations of peptide ligands.

Rat Mint2Y460A/F521A Cloning.

Using a QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies), pEGFP-rMint2Y460A/F521A was created from rat pEGFP-Mint2 and subcloned into the lentiviral pFUW vector for neuronal expression.

HEK293T Coimmunoprecipitation.

Transfected HEK293T cells were lysed, and protein extracts were incubated with precipitating antibody and protein A Ultralink resin (Thermo Scientific). Precipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for APP, GFP, and α-tubulin.

Primary Neuron Infection with rMint2Y460A/F521A and Aβ ELISA.

Primary neuronal cultures were prepared from newborn mice and infected with lentivirus for rMint2Y460A/F521A. At 15 DIV, neuronal lysate was collected, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for APP, Mint2, and α-tubulin. Conditioned media were collected and handled according to a Human Aβ42 Ultrasensitive ELISA Kit (Invitrogen).

Molecular Dynamics Simulations.

The Desmond package in Schrodinger’s Maestro suite was used to perform molecular dynamics simulations. Each simulation was run in duplicate (200 ns) under standard temperature and pressure. The simulation output was parsed frame by frame using Python, and helical propensity values were determined.

In vitro Plasma Stability.

Peptides were incubated in human plasma at 37 °C for up to 24 h. The peptides were extracted from the plasma at various time points and analyzed using UPLC.

In vitro Hepatic Clearance.

Peptides were incubated in mouse hepatic microsomes supplemented with reduced β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate (NADPH) and MgCl2 at 37 °C for up to 60 min. The peptides were extracted from the microsomes at various time points and analyzed using UPLC.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC).

Experiments were performed using an ITC200 (Malvern). Ligand-to-buffer titrations were performed to subtract the heat produced by injection, mixing, and dilution. The binding enthalpy was directly measured, and the dissociation constant (Kd) and stoichiometry (N) were obtained by data analysis using Origin software (OriginLab).

Neuronal Cell Viability.

Primary neuron cultures were treated with peptides or DMSO as indicated. The cell viability and cytotoxicity were determined using a CellTiter 96 AQueousOne Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS) Kit (Promega) and a CyQUANT LDH Cytotoxicity Assay (Thermo Fisher).

Immobilization of Peptides.

Peptide KSL-221036 and the APPWT peptide comprising a C-terminal Cys and a PEG2 linker were loaded onto Dynabeads M-270 Epoxy Beads (Thermo Fischer Scientific) according to the protocol of the manufacturer.

Protein Isolation from Neuronal Cell Lysate.

Primary neuronal cultures were prepared as described above. Neurons expressing Mint2 were infected with lentiviral inactive cre recombinase, while Mint2 knockout neurons were infected with active cre recombinase. At DIV15, neuronal lysate was collected and incubated with peptide-loaded Dynabeads. Isolated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for Mint2 and GAPDH.

ELISA Aβ Assay Following Peptide Treatment.

Primary neuronal cultures were prepared from newborn transgenic mice carrying the APPswe/PS1ΔE9 transgene. At 15 DIV, neurons were incubated with peptides, DAPT (γ-secretase inhibitor), and vehicle control 0.25% DMSO. The collected conditioned media were handled according to the protocol of the Human Aβ42 Ultrasensitive ELISA Kit (Invitrogen).

Data Analysis.

All data analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Inc.), Excel 2010 (Microsoft), and Origin 9.0 (OriginLab). Significance was evaluated using the Student’s t test in the case of two groups. The one-way ANOVA test was used in the case of three or more groups, combined with either Dunnett’s or Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Lundbeck Foundation for financial support provided to K.S. and NIH R01 AG044499 for financial support provided to A.H. We also thank Christian A. Olsen, Stephan A. Pless, Mette Ishøy Rosenbaum, and Dennis Özcelik for their critical input.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.0c10696.

Synthesis and additional experimental and analytical details (PDF).

Contributor Information

Christian R. O. Bartling, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, United States

Thomas M. T. Jensen, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark

Shawna M. Henry, Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, United States

Anna L. Colliander, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark

Vita Sereikaite, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Marcella Wenzler, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Palash Jain, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Hans M. Maric, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark

Kasper Harpsøe, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Søren W. Pedersen, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark

Louise S. Clemmensen, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark

Linda M. Haugaard-Kedström, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark

David E. Gloriam, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark

Angela Ho, Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, United States.

Kristian Strømgaard, Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark.

REFERENCES

- (1).Wang J; Gu BJ; Masters CL; Wang YJ A systemic view of Alzheimer disease - insights from amyloid-beta metabolism beyond the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13 (10), 612–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Selkoe DJ; Hardy J The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8 (6), 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Müller UC; Deller T; Korte M Not just amyloid: physiological functions of the amyloid precursor protein family. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18 (5), 281–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Haass C; Selkoe DJ Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8 (2), 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Panza F; Lozupone M; Logroscino G; Imbimbo BP A critical appraisal of amyloid-beta-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15 (2), 73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hawkes N Merck ends trial of potential Alzheimer’s drug verubecestat. BMJ. 2017, 356, j845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Honig LS; Vellas B; Woodward M; Boada M; Bullock R; Borrie M; Hager K; Andreasen N; Scarpini E; Liu-Seifert H; Case M; Dean RA; Hake A; Sundell K; Poole Hoffmann V; Carlson C; Khanna R; Mintun M; DeMattos R; Selzler KJ; Siemers E Trial of Solanezumab for Mild Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378 (4), 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia 2017, 13(4), 325–373. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Okamoto M; Sudhof TC Mints, Munc18-interacting proteins in synaptic vesicle exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272 (50), 31459–31464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Okamoto M; Südhof TC Mint 3: A ubiquitous mint isoform that does not bind to munc18–1 or –2. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 77 (3), 161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Rogelj B; Mitchell JC; Miller CC; McLoughlin DM The X11/Mint family of adaptor proteins. Brain Res. Rev. 2006, 52 (2), 305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Xie X; Yan X; Wang Z; Zhou H; Diao W; Zhou W; Long J; Shen Y Open-closed motion of Mint2 regulates APP metabolism. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 5 (1), 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Borg JP; Ooi J; Levy E; Margolis B The phosphotyrosine interaction domains of X11 and FE65 bind to distinct sites on the YENPTY motif of amyloid precursor protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996, 16 (11), 6229–6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Zhang Z; Lee CH; Mandiyan V; Borg JP; Margolis B; Schlessinger J; Kuriyan J Sequence-specific recognition of the internalization motif of the Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the X11 PTB domain. EMBO J. 1997, 16 (20), 6141–6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).King GD; Perez RG; Steinhilb ML; Gaut JR; Turner RS X11α modulates secretory and endocytic trafficking and metabolism of amyloid precursor protein: Mutational analysis of the YENPTY sequence. Neuroscience 2003, 120 (1), 143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ring S; Weyer SW; Kilian SB; Waldron E; Pietrzik CU; Filippov MA; Herms J; Buchholz C; Eckman CB; Korte M; Wolfer DP; Müller UC The secreted beta-amyloid precursor protein ectodomain APPs alpha is sufficient to rescue the anatomical, behavioral, and electrophysiological abnormalities of APP-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27 (29), 7817–7826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ho A; Liu X; Sudhof TC Deletion of Mint proteins decreases amyloid production in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28 (53), 14392–14400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lau KF; McLoughlin DM; Standen C; Miller CC X11 alpha and x11 beta interact with presenilin-1 via their PDZ domains. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000, 16 (5), 557–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Biederer T; Cao X; Sudhof TC; Liu X Regulation of APP-dependent transcription complexes by Mint/X11s: differential functions of Mint isoforms. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22 (17), 7340–7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Xie Z; Romano DM; Tanzi RE RNA interference-mediated silencing of X11alpha and X11beta attenuates amyloid beta-protein levels via differential effects on beta-amyloid precursor protein processing. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (15), 15413–15421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sullivan SE; Dillon GM; Sullivan JM; Ho A Mint proteins are required for synaptic activity-dependent amyloid precursor protein (APP) trafficking and amyloid beta generation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289 (22), 15374–15383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).McLoughlin DM; Irving NG; Brownlees J; Brion JP; Leroy K; Miller CC Mint2/X11-like colocalizes with the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid precursor protein and is associated with neuritic plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci 1999, 11 (6), 1988–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Jacobs EH; Williams RJ; Francis PT Cyclin-dependent kinase 5, Munc18a and Munc18-interacting protein 1/X11alpha protein up-regulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 2006, 138 (2), 511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lee JH; Lau KF; Perkinton MS; Standen CL; Shemilt SJ; Mercken L; Cooper JD; McLoughlin DM; Miller CC The neuronal adaptor protein X11alpha reduces Abeta levels in the brains of Alzheimer’s APPswe Tg2576 transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278 (47), 47025–47029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lee JH; Lau KF; Perkinton MS; Standen CL; Rogelj B; Falinska A; McLoughlin DM; Miller CC The neuronal adaptor protein X11beta reduces amyloid beta-protein levels and amyloid plaque formation in the brains of transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279 (47), 49099–49104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Sano Y; Syuzo-Takabatake A; Nakaya T; Saito Y; Tomita S; Itohara S; Suzuki T Enhanced amyloidogenic metabolism of the amyloid beta-protein precursor in the X11L-deficient mouse brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281 (49), 37853–37860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Saito Y; Sano Y; Vassar R; Gandy S; Nakaya T; Yamamoto T; Suzuki T X11 proteins regulate the translocation of amyloid beta-protein precursor (APP) into detergent-resistant membrane and suppress the amyloidogenic cleavage of APP by beta-site-cleaving enzyme in brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283 (51), 35763–35771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Saluja I; Paulson H; Gupta A; Turner RS X11alpha haploinsufficiency enhances Abeta amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009, 36 (1), 162–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Mitchell JC; Ariff BB; Yates DM; Lau KF; Perkinton MS; Rogelj B; Stephenson JD; Miller CC; McLoughlin DM X11beta rescues memory and long-term potentiation deficits in Alzheimer’s disease APPswe Tg2576 mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18 (23), 4492–4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kondo M; Shiono M; Itoh G; Takei N; Matsushima T; Maeda M; Taru H; Hata S; Yamamoto T; Saito Y; Suzuki T Increased amyloidogenic processing of transgenic human APP in X11-like deficient mouse brain. Mol. Neurodegener. 2010, 5, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Uhlik MT; Temple B; Bencharit S; Kimple AJ; Siderovski DP; Johnson GL Structural and evolutionary division of phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domains. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 345 (1), 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Matos MF; Xu Y; Dulubova I; Otwinowski Z; Richardson JM; Tomchick DR; Rizo J; Ho A Autoinhibition of Mint1 adaptor protein regulates amyloid precursor protein binding and processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109 (10), 3802–3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Valiyaveetil FI; Sekedat M; MacKinnon R; Muir TW Structural and functional consequences of an amide-to-ester substitution in the selectivity filter of a potassium channel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (35), 11591–11599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Eildal JN; Hultqvist G; Balle T; Stuhr-Hansen N; Padrah S; Gianni S; Stromgaard K; Jemth P Probing the role of backbone hydrogen bonds in protein-peptide interactions by amide-to-ester mutations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (35), 12998–13007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Pedersen SW; Pedersen SB; Anker L; Hultqvist G; Kristensen AS; Jemth P; Stromgaard K Probing backbone hydrogen bonding in PDZ/ligand interactions by protein amide-to-ester mutations. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Pedersen SW; Hultqvist G; Stromgaard K; Jemth P The role of backbone hydrogen bonds in the transition state for protein folding of a PDZ. domain. PLoS One 2014, 9 (4), e95619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lynagh T; Flood E; Boiteux C; Wulf M; Komnatnyy VV; Colding JM; Allen TW; Pless SA A selectivity filter at the intracellular end of the acid-sensing ion channel pore. eLife 2017, 6, e24630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Deechongkit S; Dawson PE; Kelly JW Toward assessing the position-dependent contributions of backbone hydrogen bonding to beta-sheet folding thermodynamics employing amide-to-ester perturbations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (51), 16762–16771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Deechongkit S; You SL; Kelly JW Synthesis of all nineteen appropriately protected chiral alpha-hydroxy acid equivalents of the alpha-amino acids for Boc solid-phase depsi-peptide synthesis. Org. Lett. 2004, 6 (4), 497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Stuhr-Hansen N; Padrah S; Strømgaard K Facile synthesis of α-hydroxy carboxylic acids from the corresponding α-amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55 (30), 4149–4151. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Powers ET; Deechongkit S; Kelly JW Backbone-Backbone H-Bonds Make Context-Dependent Contributions to Protein Folding Kinetics and Thermodynamics: Lessons from Amide-to-Ester Mutations. Adv. Protein Chem. 2005, 72, 39–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Deechongkit S; Nguyen H; Powers ET; Dawson PE; Gruebele M; Kelly JW Context-dependent contributions of backbone hydrogen bonding to beta-sheet folding energetics. Nature 2004, 430 (6995), 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Bieschke J; Siegel SJ; Fu Y; Kelly JW Alzheimer’s Abeta peptides containing an isostructural backbone mutation afford distinct aggregate morphologies but analogous cytotoxicity. Evidence for a common low-abundance toxic structure(s)? Biochemistry 2008, 47 (1), 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Bunagan MR; Gao J; Kelly JW; Gai F Probing the folding transition state structure of the villin headpiece subdomain via side chain and backbone mutagenesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (21), 7470–7476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Yajnik V; Blaikie P; Bork P; Margolis B Identification of residues within the SHC phosphotyrosine binding/phosphotyrosine interaction domain crucial for phosphopeptide interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271 (4), 1813–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Smith MJ; Hardy WR; Murphy JM; Jones N; Pawson T Screening for PTB domain binding partners and ligand specificity using proteome-derived NPXY peptide arrays. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26 (22), 8461–8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Taylor JW The synthesis and study of side-chain lactam-bridged peptides. Biopolymers 2002, 66 (1), 49–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Bach A; Chi CN; Olsen TB; Pedersen SW; Roder MU; Pang GF; Clausen RP; Jemth P; Stromgaard K Modified peptides as potent inhibitors of the postsynaptic density-95/N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor interaction. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51 (20), 6450–6459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Wender PA; Mitchell DJ; Pattabiraman K; Pelkey ET; Steinman L; Rothbard JB The design, synthesis, and evaluation of molecules that enable or enhance cellular uptake: peptoid molecular transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97 (24), 13003–13008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Hill MD; Goyal M; Menon BK; Nogueira RG; McTaggart RA; Demchuk AM; Poppe AY; Buck BH; Field TS; Dowlatshahi D; van Adel BA; Swartz RH; Shah RA; Sauvageau E; Zerna C; Ospel JM; Joshi M; Almekhlafi MA; Ryckborst KJ; Lowerison MW; Heard K; Garman D; Haussen D; Cutting SM; Coutts SB; Roy D; Rempel JL; Rohr AC; Iancu D; Sahlas DJ; Yu AYX; Devlin TG; Hanel RA; Puetz V; Silver FL; Campbell BCV; Chapot R; Teitelbaum J; Mandzia JL; Kleinig TJ; Turkel-Parrella D; Heck D; Kelly ME; Bharatha A; Bang OY; Jadhav A; Gupta R; Frei DF; Tarpley JW; McDougall CG; Holmin S; Rha JH; Puri AS; Camden MC; Thomalla G; Choe H; Phillips SJ; Schindler JL; Thornton J; Nagel S; Heo JH; Sohn SI; Psychogios MN; Budzik RF; Starkman S; Martin CO; Burns PA; Murphy S; Lopez GA; English J; Tymianski M; Investigators E-N Efficacy and safety of nerinetide for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke (ESCAPE-NA1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 395 (10227), 878–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Dovey HF; John V; Anderson JP; Chen LZ; de Saint Andrieu P; Fang LY; Freedman SB; Folmer B; Goldbach E; Holsztynska EJ; Hu KL; Johnson-Wood KL; Kennedy SL; Kholodenko D; Knops JE; Latimer LH; Lee M; Liao Z; Lieberburg IM; Motter RN; Mutter LC; Nietz J; Quinn KP; Sacchi KL; Seubert PA; Shopp GM; Thorsett ED; Tung JS; Wu J; Yang S; Yin CT; Schenk DB; May PC; Altstiel LD; Bender MH; Boggs LN; Britton TC; Clemens JC; Czilli DL; Dieckman-McGinty DK; Droste JJ; Fuson KS; Gitter BD; Hyslop PA; Johnstone EM; Li WY; Little SP; Mabry TE; Miller FD; Audia JE Functional gamma-secretase inhibitors reduce beta-amyloid peptide levels in brain. J. Neurochem. 2001, 76 (1), 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Tunnemann G; Ter-Avetisyan G; Martin RM; Stockl M; Herrmann A; Cardoso MC Live-cell analysis of cell penetration ability and toxicity of oligo-arginines. J. Pept. Sci. 2008, 14 (4), 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Rousselle C; Clair P; Smirnova M; Kolesnikov Y; Pasternak GW; Gac-Breton S; Rees AR; Scherrmann JM; Temsamani J Improved brain uptake and pharmacological activity of dalargin using a peptide-vector-mediated strategy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 306 (1), 371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Oller-Salvia B; Sanchez-Navarro M; Ciudad S; Guiu M; Arranz-Gibert P; Garcia C; Gomis RR; Cecchelli R; Garcia J; Giralt E; Teixido M MiniAp-4: A Venom-Inspired Peptidomimetic for Brain Delivery. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (2), 572–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Miller CC; McLoughlin DM; Lau KF; Tennant ME; Rogelj B The X11 proteins, Abeta production and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2006, 29 (5), 280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Das U; Scott DA; Ganguly A; Koo EH; Tang Y; Roy S Activity-induced convergence of APP and BACE-1 in acidic microdomains via an endocytosis-dependent pathway. Neuron 2013, 79 (3), 447–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Das U; Wang L; Ganguly A; Saikia JM; Wagner SL; Koo EH; Roy S Visualizing APP and BACE-1 approximation in neurons yields insight into the amyloidogenic pathway. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19 (1), 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).O’Brien RJ; Wong PC Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 34, 185–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.