Abstract

Background

There are still few data on the activity and safety of cetuximab‐based salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy (SCAI) in patients with squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN).

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients with SCCHN who received cetuximab‐based SCAI after programmed cell death protein 1 or programmed cell death ligand 1(PD[L]1) inhibitors. Overall response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) with SCAI and with last chemotherapy before immunotherapy (LCBI) by RECIST 1.1, percentage change from baseline in target lesions (PCTL), progression‐free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), treatment compliance, and toxicity were evaluated.

Results

Between March 2016 and November 2019, 23 patients were identified. SCAI consisted of cetuximab‐based combinations (3‐weekly cisplatin‐5FU‐cetuximab [n = 2], weekly paclitaxel‐cetuximab [n = 17], weekly cisplatin‐cetuximab [n = 2], weekly carboplatin‐paclitaxel‐cetuximab [n = 2]). ORR was 56.5% (11 partial response, 2 complete response). DCR was 78.3%. Among 13 objective responders, median best PCTL was −53.5% (range, −30% to −100%). Median OS and PFS were 12 months and 6 months, respectively. In 10 patients receiving LCBI, ORR to LCBI was 40%, whereas ORR to SCAI achieved 60%. In LCBI‐treated patients, median PFS with LCBI was 8 months and median PFS and OS with SCAI were 7 months and 12 months, respectively. Reduced dose intensity of the chemotherapy and cetuximab components occurred in 82.6% and 52.2% of the patients. Grade 1 or 2 adverse events (AEs) occurred in all patients. Grade 3 or 4 AEs developed in 65%, being grade 3 in all of them except in one patient (grade 4 neutropenia). There were no treatment‐related deaths.

Conclusion

Cetuximab‐based salvage chemotherapy after PD(L)1 inhibitors associated with high response rates and deep tumor reductions with a manageable safety profile. Subsequent lines of therapy may explain the long survival achieved in our series. These results invite to design studies to elucidate the best therapeutic sequence in patients with SCCHN in the immunotherapy era.

Implications for Practice

Cetuximab‐based salvage chemotherapy (SCAI) achieved high response rates in patients with recurrent/metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN) after progression to PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors. Objective response rate was higher than and progression‐free survival was comparable to that of chemotherapy administered before immunotherapy (IO). In most patients, SCAI consisted of weekly, well‐tolerated regimens. These observations have implications for current practice because of the limited evidence to date in SCCHN and the scant therapeutic options in this disease and invite to elucidate which may be the best treatment sequence for patients with head and neck cancer in the IO era.

Keywords: Salvage chemotherapy, Cetuximab, Immunotherapy, PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors, Head and neck cancer

Short abstract

This study explored the safety and efficacy of salvage chemotherapy combined with cetuximab after progression to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with recurrent/metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neck.

Introduction

Several immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have shown activity in the recurrent/metastatic (R/M) setting of squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN). Reported objective response rates (ORRs) with programmed cell death protein 1 or programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD[L]1) inhibitors in platinum‐refractory R/M SCCHN fall below 15%, with median overall survival (OS) times between 6 and 9 months [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Among nonplatinum‐refractory patients with a Combined Positive Score (CPS) ≥20 treated with pembrolizumab alone in the first‐line setting, ORR achieved 23% and a median OS of 14.9 months [6]. Chemotherapy is able to modify the highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, this possibly explaining in part the additive effect seen with chemoimmunotherapy combinations across different tumors, including SCCHN [6, 7]. In addition, as reported in the KEYNOTE‐048 study, progression‐free survival measured from the start of first‐line until progression with second‐line therapies has been shown to be prolonged in patients treated with ICIs in first line [8]. Therefore, sequencing ICIs and chemotherapy could be another promising strategy. Retrospective series and case reports in lung cancer and in other entities have shown increased responses to salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy (SCAI) [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. However, data demonstrating such responses in SCCHN are still limited, particularly when using anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)‐based chemotherapy [13, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. Our aim was to retrospectively study the safety and efficacy of salvage chemotherapy combined with cetuximab after progression to ICIs in patients with R/M SCCHN.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patients

This was a retrospective study of patients with R/M SCCHN that showed overt radiological and clinical progression during first‐, second‐, or third‐line treatment with programmed cell death protein (PD‐1) or programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD‐L1) inhibitors and were subsequently treated with SCAI.

A descriptive study of the general baseline characteristics of the patients was performed, including geriatric assessment employing the modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (mCCI), the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation‐27 (ACE‐27), and the Generalized Competing Event Composite Omega Score (GCE‐COS), the latter using an online tool developed to summarize different comorbidity scores to predict relative cancer versus noncancer risk, as previously described [24]. mCCI ≥2 and ACE‐27 ≥3 indicate moderate‐to‐severe comorbidity. A GCE‐COS ≥0.6 indicates a higher overall survival with oncological treatment. For mCCI calculation in the present series, patients with SCCHN were considered as localized disease if they were only locoregionally recurrent and as metastatic if they had distant disease.

ORR according to RECIST 1.1, ORR in target lesions only (ORRTL), percentage of tumor change from baseline in TL (PCTL), progression‐free survival (PFS), and OS from the start of SCAI and from the start of first‐line therapy were studied [25]. ORR and PFS of last chemotherapy given before immunotherapy (LCBI) were also analyzed. The primary endpoint was ORR and PCTL during SCAI. Secondary endpoints were safety; treatment compliance; PFS during SCAI and LCBI, defined as the time from the start of SCAI or LCBI until disease progression or death due to any cause; OS since SCAI, defined as the time from the start of SCAI until death from any cause; and OS since the first line of treatment, defined as the time from the start of first‐line therapy until death from any cause. Efficacy results are presented using different plots (waterfall plots, spider plots and swimmer plots) to better report the kinetics of response, as stated in the Trial Reporting in Immuno‐Oncology guidelines [26]. Adverse events (AEs) were recorded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.

Evaluation of Response

Tumor response was assessed according to RECIST 1.1 criteria with computed tomography (CT) scans performed every 8 to 12 weeks, according to the local protocol. Response evaluation was undertaken independently by two expert radiologists in head and neck cancer. In case of disagreement, the case was reassessed and a consensus was reached.

Partial response (PR) was defined as a ≥ 30% decrease in the sum of the diameters of target lesion (TL), progressive disease (PD) was defined as a ≥ 20% increase in the sum of diameters of TL or the appearance of new metastatic lesions, and stable disease (SD) was defined as a < 30% decrease to a 20% increase of tumor size.

PD‐L1 Expression

PD‐L1 membrane expression was measured in tumor cells using an immunohistochemistry assay (PD‐L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx; Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA). PDL1 was considered positive when ≥1% of cells showed partial membrane staining [1].

Statistical Analyses

A descriptive analysis of demographic and clinicopathological data was performed. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan‐Meier method. The χ2 test was used for comparing qualitative non‐normally distributed variables. Statistical analyses were performed using R v3.6.3 under R‐Studio 1.1.383 (R Development Core Team Vienna, Austria; https://www.r‐project.org). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement of informed consent was waived as the study was based on a retrospective analysis of existing administrative and clinical data.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Between March 2016 and November 2019, 23 patients were included and were followed until August 2020. Baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

| Patients | n = 23, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at SCAI, years | |

| Median (min–max) | 65 (36–89) |

| ≥70 | 7 (30.4) |

| <70 | 16 (69.6) |

| ECOG at SCAI | |

| 0 | 1 (4.3) |

| 1 | 6 (26.1) |

| 2 | 15 (65.2) |

| 3 | 1 (4.3) |

| mCCI, median (range: min–max) | 8 (4–10) |

| ACE‐27, median (range: min–max) | 3 (3–3) |

| GCE‐COS a | |

| Median (range: min–max) | 0.77 (0.51–0.93) |

| COS <0.6 | 3 (13) |

| COS ≥0.6 | 20 (87) |

| Smoking history | 16 (69.6) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 17 (73.9) |

| Female | 6 (26.1) |

| Anatomic subsite | |

| Oral cavity | 13 (56.5) |

| Oropharynx | 3 (1 HPV+) (13) |

| Larynx | 4 (17.4) |

| Hypopharynx | 2 (8.7) |

| Unknown primary | 1 (4.3) |

| Stage at initial diagnosis (AJCC 8th Ed) | |

| II | 2 (8.7) |

| III | 2 (8.7) |

| IVA | 13 (56.5) |

| IVB | 2 (8.7) |

| IVC | 4 (17.4) |

| Treatment at initial diagnosis | |

| Surgery | 15 (2 salvage Sx post‐CRT) (65.2) |

| Adjuvant RT | 4 (17.4) |

| Adjuvant CRT | 9 (39.1): 3wkCDDP: 4;Cetuximab: 5 |

| Radical CRT |

5 (21.7): wkCDDP: 2 Cetuximab: 3 |

| Induction CT | 7 (30.4): ERBITAX: 3;TPF: 4 |

| Upfront TX for R/M | 4 (17.4); anti‐PD‐L1 + anti‐CTLA4 (CT);anti‐PD‐L1 + iSTAT3 (CT);pembrolizumab;extreme |

| R/M disease at SCAI | |

| Locoregional only | 4 (17.4) |

| Distant only | 3 (13) |

| Locoregional + Distant | 16 (69.6) |

| No. of lines for R/M disease | 4 (2–6) |

| No. of lines before IO | |

| 0 | 13 (56.5) |

| 1 | 9 (39.1) |

| 2 | 1 (4.3) |

| Platinum before IO b | |

| No | 15 (65.2) |

| Yes | |

| PRf | 7 (30.4) |

| Non‐PRf | 1 (4.3) |

| LCBI (n = 10) | |

| EXTREME | 6 (60) |

| ERBITAX | 4 (40) |

| IO | |

| Within clinical trials | |

| Anti‐PD‐1 | 1 (4.3) |

| Anti‐PD‐L1 | 3 (13) |

| Anti‐PD‐L1 + STAT3 inhibitor | 7 (30.4) |

| Anti‐PD‐L1 + CXCR2 inhibitor | 1 (4.3) |

| Regular practice | |

| Nivolumab | 10 (43.5) |

| Pembrolizumab | 1 (4.3) |

| SCAI | |

| EXTREME | 2 (8.7) |

| ERBITAX | 17 (74) |

| CARBITAX | 2 (8.7) |

| wkCDDP‐Cetuximab | 2 (8.7) |

GCE‐COS ≥0.6 indicates significantly higher overall survival with treatment intensification (i.e., chemotherapy).

Platinum received either in the locally advanced and/or R/M settings. Platinum‐refractory disease was defined as patients progressing to platinum‐based regimen for advanced disease or relapsing within 6 months of platinum‐based therapy with curative intent.

Abbreviations: ACE‐27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation‐27; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CARBITAX, weekly carboplatin‐paclitaxel‐cetuximab; CRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ERBITAX, paclitaxel plus cetuximab; EXTREME, 3‐weekly cisplatin‐5FU‐cetuximab; GCE‐COS, Generalized Competing Event Composite Omega Score; IO, immunotherapy; HPV, human papillomavirus; LCBI, last chemotherapy before immunotherapy; mCCI, modified Charlson Comorbidity Index; PRf, platinum‐refractory; R/M, recurrent/metastatic; RT, radiotherapy; SCAI, salvage cetuximab‐based chemotherapy after immunotherapy; Sx, surgery; TPF, 3‐weekly docetaxel‐platinum‐5FU; TX, therapy; wkCDDP, weekly cisplatin; 3wkCDDP, 3‐weekly cisplatin.

The most common primary tumor location was the oral cavity (56.5%). Eighty‐two percent were stage IV at initial diagnosis, 65.2% had been treated with surgery, 56.5% with adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) or chemoradiotherapy (CRT), 30.4% with induction chemotherapy, and 21.7% with radical CRT. In the R/M setting, 43.4% of the patients had received at least one line of chemotherapy prior to immunotherapy (IO), and up to 30.4% were platinum‐resistant.

Median age was 65 years, and 30.4% were ≥ 70 years. At SCAI, a majority of patients had an ECOG performance status ≥2 (69.5%). Median mCCI score was 8, ACE‐27 was 3, and GCE‐COS was 0.77.

ICIs and cetuximab‐based chemotherapy administered prior and after immunotherapy were as follows.

PD‐1/PD‐L1 Inhibitors Used

Twelve patients received PD‐L1 or PD‐1 inhibitors within clinical trials (NCT02252042, NCT02551159, NCT02499328): PDL1 inhibitors (n = 11) and PD‐1 inhibitors (n = 1); 11 patients received PD‐1 inhibitors as per standard practice: nivolumab (n = 10) and pembrolizumab (n = 1); PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors were always administered either as single agents or in combination with other ICIs (anti‐CTLA‐4) or immunomodulatory agents (STAT3 or CXCR2 inhibitors).

Cetuximab‐Based Chemotherapy Regimens

Four chemotherapy regimens (all in combination with the anti‐EGFR agent cetuximab) were used either as SCAI, LCBI, or both.

Weekly cetuximab (400 mg/m2 [load], 250 mg/m2 [maintenance]) plus paclitaxel (80 mg/m2; ERBITAX regimen): LCBI (n = 4), SCAI (n = 17).

Weekly cetuximab (400 mg/m2 [load], 250 mg/m2 [maintenance]) plus paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) plus carboplatin (AUC 2; CARBITAX regimen): SCAI (n = 2).

Weekly cisplatin (50 mg/m2), and weekly cetuximab (400 mg/m2 [load], 250 mg/m2 [maintenance]): SCAI (n = 2).

Three‐weekly cisplatin (100 mg/m2), infusional 5FU (750 mg/m2 per day on days 1 to 5) and weekly cetuximab (days 1, 8 and 15; EXTREME regimen): LCBI (n = 6), SCAI (n = 2).

Response During SCAI

Objective Responses and Percentage Change from Baseline in Target Lesions in Objective Responders

ORR was 56.5% (13/23), with 11 PRs and 2 complete responses (CRs). Eight of these responders received SCAI in second line and five received it in third line. Five patients showed SD, and five showed PD as best responses during SCAI. Disease control rate was 78.3%. Median best PCTL in objective responders was −57.5% (range, −30 to −100).

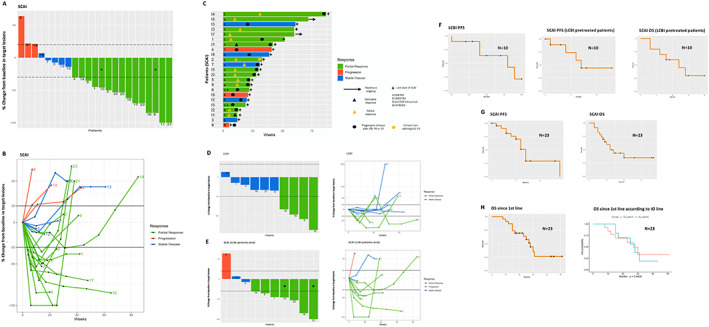

Responses to SCAI occurred in one patient treated with EXTREME and in 12 patients treated with weekly regimens (ERBITAX [n = 10], CARBITAX [n = 1], weekly cisplatin [wkCDDP]‐cetuximab [n = 1]; Figs. 1, 2; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Efficacy of SCAI in the whole population and in LCBI‐pretreated patients. Waterfall plot showing objective response in TL with SCAI (A). Spider plot showing best objective response in TL and PCTL during treatment with SCAI (B). Swimmers plot depicting treatment exposure and overall response duration per RECIST 1.1 with SCAI (C). Waterfall and spider plots showing best objective responses in TL with LCBI (D) and with SCAI (E). ORR was higher for SCAI (60%) than for LCBI (40%). In addition responses were deep and durable. Note that scales are different between D and E. Kaplan‐Meier estimates of PFS and OS in LCBI‐treated patients (F) and in the whole population since the start of SCAI and since first line (G, H). Comparison of OS since first line in patients treated with first‐ versus second‐ or further IO lines (H). *These patients achieved PR in TL but were classified as PD due to the appearance of pulmonary metastases [(A) patients 6 and 10; (E) patient 10]. +This patient achieved a CR to SCAI [(E) patient 21]. Dashed (A, D, E) and solid (B) black lines mark the limits that define objective responses. Abbreviations: CR, complete response; IO, immunotherapy; LCBI, last chemotherapy before immunotherapy; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PCTL, percentage change from baseline in target lesions; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SCAI, cetuximab‐based salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy; SD, stable disease; TL, target lesions.

Table 2.

Response rate, best percentage change from baseline in target lesions, and Kaplan‐Meier estimates of progression‐free and overall survival

| A. Response rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor response | SCAI | LCBI | SCAI (LCBI pretreated) |

| n | 23 | 10 | 10 |

| ORR, n (%) | 13/23 (56.5) | 4/10 (40) | 6/10 (60) |

| Type of response, n (%) | |||

| CR | 2/23 (8.7) | 0 | 1/10 (10) |

| PR | 11/23 (47.8) | 4/10 (40) | 5/10 (50) |

| SD | 5/23 (21.7) | 5/10 (50) | 2/10 (20) |

| PD | 5/23 (21.7) | 1/10 (10) | 2/10 (20) |

| Best PCTL among objective responders, % (range) | −57.5 (−30 to −100) | ‐ | −35.5 (−30.9 to −100) |

| ORR, n (%) | |||

| IO in first line | 7/12 (58.3) | ‐ | ‐ |

| IO in second/third line | 6/11 (54.5) | ‐ | ‐ |

| DCR | 18/23 (78.3) | 9/10 (90) | 8/10 (80) |

| Response in TL only | |||

| ORR | 15/23 (65.2) | ‐ | 7/10 (70) |

| PCTL among objective responders, % (range) | −57.5 (−30 to −100) | ||

| PCTL among objective responders in TL only, % (range) | −53.5 (−30 to −100). | ‐ | −36 (−30.9 to −100) |

| Patients with tumor reduction in TL, % (range) | 82.6 (19/23) | ‐ | 80 (8/10) |

| PCTL among patients with tumor reduction in TL, % (range) | −45 (−4 to −100) | ‐ | −35.5 (−100 to −7.5) |

| B. Follow‐up and survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCAI | LCBI | SCAI (LCBI pretreated) | First line a | First line vs. second line IO b | |

| n | 23 | 10 | 10 | 23 | 13 vs. 10 |

| Follow‐up c | 12 mo (4–38) | 6 mo (1–12) | 5 (2.5–15) | 22 (9–51) | 22 (9–51) |

| PFS | 6 mo (95% CI, 5–8) | 8 mo (95% CI, 4–NR) | 7 mo (95% CI, 4–NR) | ‐ | ‐ |

| OS | 12 mo (95% CI, 9‐NR) | ‐ | 12 mo (95% CI, 6–NR) | 28 (95% CI, 23–NR) |

First‐line IO: 27 mo (95% CI, 15–NR) vs. second‐line IO 28 mo (95% CI, 17–NR) p = .94 |

Survival times calculated from the start of first‐line therapy in the whole population.

Survival times calculated from the start of first‐line therapy in patients treated with first‐line vs. second‐line IO.

Follow‐up times are expressed as median (range: min–max).

Abbreviations: (‐), not applicable; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; IO, immunotherapy; LCBI, last chemotherapy before immunotherapy; NR, not reached; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PCTL, best percentage change from baseline in target lesions; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression‐free survival; PR, partial response; RR, response rate; SCAI, cetuximab‐based salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy; SD, stable disease; TL, target lesion.

Objective responses to SCAI occurred in 4 of 12 patients previously treated with PD‐1 or PD‐L1 inhibitors within clinical trials and in 10 of 11 patients treated with PD1 inhibitors outside clinical trials, this difference being statistically significant (p = .019). In addition, ORR to SCAI was higher in patients treated with PD1 inhibitors (most outside clinical trials) (anti‐PD‐1 vs. anti‐PD‐L1: 83% vs. 27%, p = .007). There were no differences in ORR to SCAI among patients treated with IO in first line versus those treated with IO in second or third lines (58.3% vs. 54.5%, p = 0.768; Table 2).

Response Rate in Target Lesions and Percentage Change from Baseline in Target Lesions

There were two patients with paradoxical responses, which achieved a major response in TL but suffered the appearance of new metastatic lesions. ORRTL was 65.2% (15/23). Among responders in TL, median best PCTL was −53.5% (range, −30 to −100). Nineteen patients (82.6%) showed some degree of tumor reduction in TL, with a median best PCTL of −45% (range: −4% to −100%; Figs. 1, 2; Tables 2, 3).

Table 3.

Clinical history and lines of treatment received before, during, and after salvage cetuximab‐based chemotherapy after immunotherapy (SCAI) for each individual patient

| Patient order No. | Age/primary tumor /AJCC 8th Ed stage/PDL1/treatment at initial DX | Age/PR/ECOG/ mCCI/ACE‐27/GCE‐COS at first SCAI | Location of disease at first SCAI | First line (ORR/PCTL /TD) | Second line (ORR/PCTL/TD) | Third line (ORR/PCTL/TD) | Fourth line (ORR/PCTL /TD) | Fifth line (ORR/PCTL /TD) | Sixth line (ORR/PCTL /TD) | OS SCAI, OS first line, status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | M/54 y/OC/IVA/NA/iCT➔SX➔3wkCDDP‐RT | 58/PRf/ECOG 1/mCCI = 7/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.779 | Mx (LN, Lung) | EXTREME (7.5 m) | Anti‐PD1 (CT) |

ERBITAX PR/‐45% (6.5 mo) |

– | – | – | OS SCAI: 12 m, OS first L: 31 mo, dead |

| 2. | M/69 y/HP/II/80%/BRT➔SX | 71/PNRf/ECOG 1/ mCCI = 10/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.51 | Mx (Lung) | Anti‐PDL1 + Anti‐CTLA4 (CT) | ERBITAX, PR/−30%/7 mo |

Nivo PR/‐80/6 mo |

ERBITAX PD/+20%/1 mo |

Nivo ‐/‐/1 mo |

EXTREME SD/‐10%/5 mo |

OS SCAI: 20 mo, OS first L: (CT), dead |

| 3. | M/62 y/HP/IVA/<1%/BRT➔SX | 65/PRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 9/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.775 | L + R + Mx (LN) | EXTREME | Anti‐PDL1 + iSTAT3 (CT) |

ERBITAX SD/‐7.5%/3 mo |

– | – | – | OS SCAI: 3 m, OS first L: 15 mo, dead |

| 4. | F/70 y/HP/IVB/NA/BRT➔SX | 75/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 8/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.741 | L + R + Mx (Liver) | Anti‐PDL1 (CT) | ERBITAX, PD/+22%/9 mo | – | – | – | – | OS SCAI: 10 mo, OS first L: (CT), Dead |

| 5. | M/59 y/OC/IVA/<1%/SX➔3wkCDDP‐RT | 61/PRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 8/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.821 | L + R + Mx (LN) | Anti‐PDL1 + iSTAT3 (CT) | ERBITAX, PR/−50%/5 mo |

Nivo PD/+50%/5 mo |

EXTREME PR/‐60%/3 mo |

Nivo CR/3 m |

– | OS SCAI: 37 mo, OS first L: (CT), AWOD |

| 6. | M/68 y/LX/IVC/NA/Anti‐PDL1 + iSTAT3 (CT) | 68/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 9/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.716 | L + R + Mx (Lung) | Anti‐PDL1 + iSTAT3 (CT) | ERBITAX, PD a /−85%/4 mo |

Nivo (‐/‐/1 mo) |

– | – | – | OS SCAI: 5 mo, OS first L: (CT), dead |

| 7. | F/87 y/OC/IVA/NA/iCT (C‐Px)➔BRT | 89/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 7/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.644 | L + R | Anti‐PDL1 + iSTAT3 (CT) | ERBITAX, SD/−4%/7 mo |

Nivo ‐/‐/ 1 mo |

C‐wkCDDP ‐/‐/5m |

– | – | OS SCAI: 12 mo, OS first L: (CT), dead |

| 8. | M/35 y/OC/IVA/<1%/iCT (TPF x3)➔SX➔3wkCDDP + RT | 36/PRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 6/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.930 | L + R + Mx (Lung, LN, bone) | ERBITAX PR/‐/9m | EXTREME, SD/‐/3 mo |

Anti‐PDL1 + iSTAT3 (CT) |

EXTREME PD/+64%/2m |

ERBITAX PD/‐/2m |

– | OS SCAI: 3 mo, OS first L: 15 mo, dead |

| 9. | F/50 y/OC/IVA/<1%/SX➔BRT | 51/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 9/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.843 | L | ERBITAX PR/‐/12m | Nivo, PD/+60%/1 mo |

EXTREME PR/‐35.5%/5 mo |

Nivo PD/+50%/1 mo |

C‐wkCDDP SD/‐10%/8 mo |

– | OS SCAI: 14 mo, OS first L: 28 mo, dead |

| 10. | M/60 y/LX/IVC/<1%/C‐PF | 63/PRf/ECOG 1/ mCCI = 8/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.756 | L + R + Mx (Lung, LN, bone) | EXTREME SD/+10%/6 mo | Nivo, PD/‐/11 mo |

ERBITAX PD a /‐46%/4 mo |

Nivo ‐/‐/2 mo |

– | – | OS SCAI: 6 mo, OS first L: 25 mo, dead |

| 11. | M/61 y/OP/IVB/60%/BRT | 62/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 6/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.769 | L | Nivo PD/‐/1 mo | ERBITAX, PR/−100%/3 mo |

C‐wkCDDP PR/‐/17 mo |

ERBITAX PD/‐/5.5 mo |

Pembro‐wkCBDCA‐Px ‐/‐/2 mo |

– | OS SCAI: 26 mo, OS first L: 28 mo, AWD |

| 12. | M/72 y/OP/IVC/20%/Anti‐PDL1 + anti‐CTLA4 (CT) | 74/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 10/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.534 | L + R + Mx (Bone) at diag | Anti‐PDL1 + Anti‐CTLA4 (CT) | Anti‐PDL1 + iCXCR2 (CT) |

ERBITAX SD/‐14%/4 mo |

– | – | – | OS SCAI: 5 mo, OS first L: (CT), dead |

| 13. | F/64 y/OP/IVB/20%/iCT (TPF × 3)➔wkCDDP + RT | 67/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 9/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.770 | L + R + Mx (Lung) | Anti‐PDL1 (CT) | ERBITAX, SD/−11%/14 mo |

Nivo SD/‐/13 mo |

C‐wkCDDP SD/+10% 4 mo |

– | – | OS SCAI: 36 mo, OS first L: (CT), AWD |

| 14. | M/54 y/LX/IVA/5%/SX➔RT | 57/PNRf/ECOG 0/ mCCI = 10/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.716 | Mx (Lung, liver) | ERBITAX PR/‐81.5%/ | Nivo, PR/−70%/11 mo |

ERBITAX PR/‐30.9%/20 mo |

Nivo PD/‐/1 mo |

– | – | OS SCAI: 20 mo, OS first L: 43 mo, AWD |

| 15. | M/68 y/OC/IVB/NA/SX➔3wkCDDP + RT | 69/PRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 8/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.828 | L + R + Mx (Lung, liver, LN, bone) | Nivo PD/‐/1 mo | ERBITAX, PR/−62.4%/8 mo |

Nivo PD/‐/3 mo |

ERBITAX SD/+15% /8.5 mo |

– | – | OS SCAI: 18 mo, OS first L: 20 mo, AWD |

| 16. | M/57 y/OC/III/90%/SX➔RT | 58/PRf/ECOG 1/ mCCI = 4/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.740 | R | EXTREME PR/‐58%/3 mo |

Nivo PD/‐/2 mo |

ERBITAX PR/‐85%/17 mo |

– | – | – | OS SCAI: 15 mo, OS first L: 22 mo, AWD |

| 17. | M/55 y/OC/III/5%/SX➔BRT | 65/PNRf/ECOG 1/ mCCI = 8/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.796 | L + Mx (LN) | Nivo SD/‐/13.5 mo |

ERBITAX PR/−70%/14 mo |

– | – | – | – | OS SCAI: 13 mo, OS first L: 27 mo, AWD |

| 18. | F/59 y/OC/II/5%/SX➔RT | 61/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 8/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.844 | L + R + Mx (LN) | ERBITAX SD/‐20.5%/6 mo |

Nivo PD/‐/3 mo |

C‐wkCDDP SD/+6.9%/8 mo |

– | – | – | OS SCAI: 8 mo, OS first L: 17 mo, dead |

| 19. | M/43 y/LX/IVA/10%/SX➔RT | 48/PRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 6/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.824 | L + R + Mx (Bone) | Anti‐PDL1 + iSTAT3 (CT) |

CARBITAX PD/+21%/5 mo |

Nivo PD/‐/1 mo |

C‐wkCDDP ‐/‐/1 mo |

– | – | OS SCAI: 7 mo, OS first L: ‐(CT), dead |

| 20. | M/59 y/OC/IVC/60%/Anti‐PD1 (Pembro) | 59/PNRf/ECOG 3/ mCCI = 8/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.845 | L + Mx (Lung) | Pembro PD/‐/1 mo |

CARBITAX PR/−53.5%/6.5 mo |

Nivo PD/‐/1 mo |

C‐wkCDDP PD/‐/ 1 mo |

– | – | OS SCAI: 9 mo, OS first L: 10 mo, dead |

| 21. | M/74 y/UPHNC/IVA/<1%/SX➔BRT | 76/PRf/ECOG 1/ mCCI = 9/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.586 | R + Mx (Bone) | EXTREME SD/‐20%/4 mo |

NIvo PD/‐/1.5 mo |

ERBITAX PR/‐100%/10 mo |

– | – | – | OS SCAI: 9 mo, OS first L: 18 mo, AWD |

| 22. | F/75 y/OC/IVA/80%/SX➔BRT | 77/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 9/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.757 | L + Mx (Pleura) | ERBITAX PR/‐50%/4.5 mo |

Nivo PR/‐/11 mo |

C‐wkCDDP PR/‐53%/3 mo |

Nivo SD/‐/5 mo |

C‐wkCDDP ‐/‐/ 1 mo |

– | OS SCAI: 20 mo, OS first L: 43 mo, AWD |

| 23. | M/70 y/OC/IVB/<1%/SX➔BRT | 71/PNRf/ECOG 2/ mCCI = 9/ACE27 = 3/COS = 0.780 | L + R + Mx (Skin) | Anti‐PDL1 + iSTAT3 (CT) |

ERBITAX PR/−70%/8 mo |

Pembro PD/‐/1 mo |

C‐wkCDDP ‐/‐/ 3 mo |

– | – | OS SCAI: 13 mo, OS first L: (CT), AWD |

Blue cells represent first IO and adjacent brown cells indicate first SCAI. The table also shows that some patients were rechallenged with IO followed by salvage chemotherapy. Data on efficacy or toxicity occurring during treatment within a clinical trial are not given. In those cases it is indicated as “(CT)”.

Partial response in target lesions but overall progressive disease due to appearance of new lesions.

PDL1 expression on tumor cells.

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; (–), not applicable or not available; ACE‐27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation‐27; BRT, bioradiotherapy (radiotherapy combined with cetuximab); CARBITAX, weekly cetuximab; carboplatin and paclitaxel; CR, complete response; CT, clinical trial; C‐wkCDDP, cetuximab plus weekly cisplatin; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ERBITAX, weekly cetuximab plus paclitaxel; EXTREME, three‐weekly cisplatin‐5FU and weekly cetuximab; F, female; GCE‐COS, Generalized Competing Event Composite Omega Score; HP, hypopharynx; iCT, induction chemotherapy; LCBI, last chemotherapy before immunotherapy; L, local; LN, lymph node; Lx, larynx; M, male; Mx, metastatic; mCCI, modified Charlson Comorbidity Index; N, No. of patients; Nivo, nivolumab; NR, not reached; OC, oral cavity; OP, oropharynx; ORR, overall response rate in target and nontarget lesions; OS, overall survival; PCTL, best percentage change from baseline in target lesions; PD, progressive disease; Pembro, pembrolizumab; PFS, progression‐free survival; PNRf, platinum nonrefractory; PR, partial response; PRf, platinum‐refractory; R, regional; RT, radiotherapy; SCAI, salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy; SD, stable disease; SX, surgery; TD, treatment duration; TPF, three‐weekly docetaxel‐platinum‐5FU; UPHNC, unknown‐primary head and neck cancer.

Objective Response to SCAI According to PD‐L1 Expression

PD‐L1 expression could be tested in 18 patients: 11 objective responders to SCAI and 7 nonresponders (Table 3). PDL1 expression ≥1% occurred in 7 or 11 (64%) responders and in 4 of 7 nonresponders (57%). PD‐L1 < 1% occurred in 4 of 11 (36%) responders and 3 of 7 (43%) of nonresponders. There were no statistically significant differences in ORR to SCAI according to PD‐L1 expression (p = .783).

Clinical Response to SCAI

At the start of SCAI, 69.5% of the patients had ECOG ≥2. After starting SCAI, ECOG improved by 1 point in 14 patients (61%). Median time to ECOG improvement was 7 weeks (min–max: 3–20).

Response During LCBI and SCAI in LCBI‐Treated Patients

Among 10 patients treated with IO in second (n = 9) or third line (n = 1), LCBI consisted of EXTREME (n = 6) and ERBITAX (n = 4), whereas in these same patients SCAI consisted of ERBITAX (n = 6), wkCDDP‐cetuximab (n = 2), or EXTREME (n = 2; Table 1).

ORR to LCBI was 40%, whereas ORR to SCAI achieved 60% (if considering ORR in TL only, it achieved 70%, as one patient showed response in TL with appearance of new metastatic lesions). Two of the patients received the same regimens as LCBI and SCAI. In one of these patients treated with ERBITAX pre‐ and post‐IO, ORR was PR both as LCBI (−81.5%) and as SCAI (−30.9%; Figs. 1, 2; Tables 2, 3).

Progression‐Free Survival and Overall Survival

In the whole population, after a median follow‐up of 12 months (range, 4–38), median OS since SCAI was 12 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 9–not reached [NR]) and PFS was 6 months (95% CI, 5–8). Median OS since first line was 28 months (95% CI, 23–NR). OS since first‐line was similar between patients receiving ICIs in first line versus second line (27 vs. 28 months, p = .94).

In LCBI‐treated patients, median PFS during LCBI was 8 months (95% CI, 4–NR) and during SCAI was 7 months (95% CI, 4–NR). Median OS with SCAI in LCBI‐treated patients achieved 12 months (95% CI, 6–NR; Fig. 1, Table 2).

Objective Response Rate and Treatment Compliance During PD(L)1 Inhibitor Treatment and Time Lapse Between PD(L)1 Inhibitors and SCAI

ORR to PD(L)1 inhibitors in the total population was 17%. Median treatment duration during IO was 3 months (0.5–24). Median number of IO doses was 5 (1–30). Median time from last dose of PD(L)1 inhibitors to SCAI was 16 days (range, 7–75). All patients discontinued PD(L)1 inhibitors and started SCAI because of radiological progression with symptomatic and ECOG performance status deterioration.

Median number of PD‐1 inhibitor doses in patients treated outside clinical trial (all treated with nivolumab) was 6 (2–26). Median treatment duration in these latter group was 3 months (1–13.5).

Treatment Compliance During SCAI

Total Population

In the whole series, 82.6% and 52.2% of the patients had a reduced dose intensity of the chemotherapy and cetuximab components, respectively. Median treatment delay of chemotherapy was 2 weeks (min to max: 0–10) and median dose reductions was 1 (min to max: 0–2). Single‐agent maintenance cetuximab was started in 7 of 23 patients (30.4%; Table 4; supplemental online Table 1).

Table 4.

Summary of treatment compliance and toxicity during cetuximab‐based salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy (SCAI)

| A. Treatment compliance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regimen and agent | Chemotherapy + cetuximab | Maintenance cetuximab | ||||||

| Median No. of cycles | Median No. weeks delay | Median dose reductions | Median dose/cycle | Median No. of cycles | Median No. weeks delay | Median dose reductions | Median dose quantity/cycle | |

| ERBITAX (n = 17) | ||||||||

| Paclitaxel | 12 (Min–max: 4–38) | 2 (Min–max: 0–10) | 1 (Min–max: 0–2) | 75 mg/m2/qwk (Min–max: 50–80) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cetuximab | 15 (Min–max: 4–38) | 1 (Min–max: 0–10) | 0 (Min–max: 0–2) | Load: 400 mg/m2; follow: 225 mg/m2/qwk (Min–max: 221–250) | 14 (Min–max: 7–30) | 0 (Min–max: 0–3) | 0 (Min–max: 0–1) | 500 mg/m2/q2wk (Min–max: 300–500) |

| EXTREME (n = 2) | ||||||||

| Cisplatin | 3.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 70 mg/m2/q3wk | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 5FU | 3.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 3,378 mg/m2/q3wk | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cetuximab | 3.5 | 1.5 | 1 | Load: 400 mg/m2; follow (mean): 237 mg/m2/qwk | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| CARBITAX (n = 2) | ||||||||

| Carboplatin | 16.5 | 5 | 0 | 100.5 mg/m2/qwk | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Paclitaxel | 18 | 3.5 | 0 | 74 mg/m2/qwk | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cetuximab | 21.5 | 0 | 0 | Load: 400 mg/m2; Follow (mean): 250 mg/m2/qwk | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| wkCDDP‐Cetuximab (n = 2) | ||||||||

| wkCDDP | 11 | 4.5 | 2 | 39 mg/m2/qwk | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cetuximab | 13 | 3.5 | 0 | Load: 400 mg/m2; follow (mean): 237 mg/m2/qwk | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| B. Toxicity (ERBITAX) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCAI | ERBITAX (n = 17), n (%) | |||||

| Event Grade (CTCAE v4.0) | G1–2 | G1 | G2 | G3–4 | G3 | G4 |

| Event | 17/17 (100) | 17/17 (100) | 17/17 (100) | 11/17 (64.7) | 11/17 (64.7) | 1/17 (6) |

| General | ||||||

| Asthenia | (100) | 7/17 (41) | 10/17 (59) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nutrition and metabolic disorders | ||||||

| Decreased appetite | (88.5) | 11/17 (65) | 4/17 (23.5) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hypomagnesemia | (47) | 2/17 (12) | 6/17 (35) | 6 | 1/17 (6) | ‐ |

| Gastro‐intestinal | ||||||

| Nausea | (30) | 3/17 (18) | 2/17 (12) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Diarrhea | (6) | ‐ | 1/17 (6) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mucositis | (24) | 1/17 (6) | 3/17 (18) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Skin | ||||||

| Acneiform rash | (76.5) | 4/17 (23.5) | 9/17 (53) | 23.5 | 4/17 (23.5) | ‐ |

| Hand‐foot fissures | (59) | 4/17 (23.5) | 6/17 (35) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Onycolisis | ‐ | 10/17 (59) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Onycodystrophy | ‐ | 6/17 (35) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Paronichia | (18) | ‐ | 3/17 (18) | 6 | 1/17 (6) | ‐ |

| Eye disorders | ||||||

| Conjunctivitis | (12) | ‐ | 2/17 (12) | ‐ | 1/17 (6) | ‐ |

| Ectropion | (6) | ‐ | 1/17 (6) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Infections | ||||||

| URT | (12) | ‐ | 2/17 (12) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Pneumonia | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 23.5 | 4/17 (23.5) | ‐ |

| Diverticulitis | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 6 | 1/17 (6) | ‐ |

| Soft tissue | (18) | ‐ | 3/17 (18) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | ||||||

| Anemia | (23.5) | 1/17 (6) | 3/17 (18) | 12 | 2/17 (12) | ‐ |

| Neutropenia | (29.4) | ‐ | 5/17 (29.4) | 12 | 1/17 (6) | 1/17 (6) |

| Lymphopenia | (23.5) | ‐ | 4/17 (23.5) | 12 | 2/17 (12) | ‐ |

| Thrombopenia | (23.5) | 2/17 (12) | 2/17 (12) | 6 | 1/17 (6) | ‐ |

| Nervous system disorders | ||||||

| Peripheral neuropathy | (41.5) | 3/17 (18) | 4/17 (23.5) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Vascular disorders | ||||||

| Tumor bleeding | (18) | ‐ | 3/17 (18) | 12 | 2/17 (12) | ‐ |

| C. Toxicity (Other regimens) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event Grade (CTCAE v4.0) | G1–2 | G1 | G2 | G3–4 | G3 | G4 |

| No. (%) | 6/6 (100) | 5/6 (83) | 6/6 (100) | 4/6 (67) | 4/6 (67) | ‐ |

| SCAI (Summary of events for Other regimens) | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | ||

| Event type | Asthenia (1), decreased appetite (1), nausea (1), acneiform rash (1) | Asthenia (1), decreased appetite (1), acneiform rash (1), lymphopenia (1), onycolisis (1), onycodystrophy (1), hand‐foot fissures (1), thrombopenia (1) | Neutropenia (1), anemia (1), hemoptisis (lung tumor bleeding) (1) | ‐ | ||

| wkCDDP‐Cetuximab (n = 2) | ||||||

| Event type | Acneiform rash (1), hand‐foot fissures (1) | Nausea (1) | Acneiform rash (1), hand‐foot fissures (1) | ‐ | ||

| EXTREME (n = 2) | ||||||

| Event Type | Acneiform rash (1) | Asthenia (2), decreased appetite (2), acneiform rash (1), lymphopenia (1), nausea (2), onycolisis (1), onycodystrophy (1), hand‐foot fissures (1), peripheral neuropathy (1) | Pneumonia (1) | ‐ | ||

(‐): not applicable. Data for ERBITAX cohort are presented as medians (range: min–max). Event grading according to CTCAE version 4.0.

Data for the remnant patients are presented as means due to the low number of cases.

Abbreviations: CARBITAX, weekly cetuximab; paclitaxel and carboplatin; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; ERBITAX, weekly cetuximab plus paclitaxel; EXTREME, 3‐weekly platinum‐5FU plus weekly cetuximab; q3wk, every 3 weeks; qwk, every week; SCAI, salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy; wkCDDP‐Cetuximab, weekly cisplatin plus cetuximab.

Table 5.

Summary of studies and case reports on salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy (SCAI) in squamous cell cancer of the head and neck

| Studies | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | n/baseline characteristics | LCBI | IO | SCAI | |||||||

| Agents | ORR | PFS/OS | Agents | ORR | PFS/OS | Agents/ECOG | ORR | PFS/OS | |||

| Saleh et al. (2019) [18] |

n = 82 |

≥1 line pre‐IO: 76%; median No. lines: 3 (2–8); median No. lines pre‐SCAI: 2 (1–6); LCBI: platinum (61%), taxane (11%), other (4%) | ORR (CR/PR): 38% | – | Anti‐PD1: 30; anti‐PDL1: 5; anti‐CTLA4: 2; anti‐PDL1 + anti‐CTLA4: 16; anti‐PD1 + anti‐KIR: 29 | ORR (PR): 13.6% | – | Agents: IO in first L: 40%, IO in second L: 27%; ECOG: 0: 14%, 1: 59%, 2–3:27% | CR/PR: 30% (3CR, 22 PR), DCR: 57%; CR/PR SCAI ± cetuximab: 53% vs. 25% (p = 0.024) | PFS: 3.6 mo (95% CI, 2.6–5.1); OS: 7.8 mo (95% CI, 5.3–10.8); PFS IO first vs. second L: 5.2 vs. 3.4 mo, p = .14); OS IO first vs. second L: 12 vs. 7.6 mo, p = .36) | |

| Pestana et al. (2019) [19] | n = 43; median age Dx: 58 (23–83); median No. lines: 3 (2–8) | LCBI agent: platinum (61%), taxane (11%), other (4%); lines pre‐IO: ≥1 line pre‐IO: 76%; agents pre‐IO: platinum prior to IO: 90.7%, platinum within 6‐mo of IO: 60.5%; Anti‐EGFR prior to IO: 34.8%, anti‐EGFR within 6‐m of iO: 27.9% | ‐ORR: 47% (7/15) | ‐PFS: 3.89 m (95%CI 2.56–6.97) | Agent: pembro: 67.5%; nivo: 32.5%; IO line: IO first L: 58.1%; IO second L: 39.5%; IO third L: 2.3% | ORR (PR): 20.9%. No difference in ORR based on prior anti‐EGFR or not (p = 0.24) | PFS: 2.79 m (95%CI: 2.23–4.11); PFS (OP): HR 0.34 (95%CI: 0.18–0.67); No survival difference between first L IO vs. CT ± anti‐EGFR | Agent: anti‐EGFR alone: 37.2%, single‐agent CT: 32.5%, anti‐EGFR + CT: 18.6%, CT + other: 11.6%; median No. l lines pre‐SCAI: 2 (1–6); ECOG: 0: 14%, 1: 59%, 2–3: 27% | ORR Anti‐EGFR alone: 37.5% (similar to ORR with CT); Response to SCAI associated with prior response to IO | PFS: 4.24 m (95%CI 2.63–5.19); OS: 8.41 m (95%CI 7.62–11.07); No difference between single‐agent cetuximab and CT in PFS (p = .78) and OS (p = .22); OS from first L: 16.5 m (95%CI: 13.8–28.9; p = 0.16) | |

| Aspeslagh et al. (2017) [17] | N = 118 (n = 13 HNC) median age Dx: 54 (20–78) | – | RR: 31% | PFS: 4.1 mo | 51/118: anti‐PD(L)1; 67/118: IO w/o anti‐PD(L)1 | – | – | – | ORR post‐IO: 8% | PFS pre‐IO: 4.1 mo; PFS post‐IO: 3.6 mo; ORR pre‐IO: 31%; ORR post‐IO: 8% | |

| Harrington et al. (KN‐048 ASCO 2020) [8] | n = 882 | – | – | – | Pembro (n = 301) vs. EXTREME (n = 300) | CPS ≥20 | 23.3% vs. 36.1% | PFS: 3.4 vs. 5.3; OS: 14.8 vs. 10.7 | Pembro arm (49.2%): CT: 44.9%, EGFRi: 19.6%, ICIs: 2%, Other: 1.3% | – | Pembro arm PFS2a longer in:CPS ≥20: 11.7 vs. 9.4; CPS ≥1: 9.4 vs. 8.8 |

| CPS 1–19 | 14.5% vs. 33.8% | PFS:2.2 vs. 4.9; OS: 10.8 vs. 10.1 | |||||||||

| TP | 16.9% vs. 36% | PFS: 2.3 vs. 5.2; OS: 11.5 vs. 10.7 | Pembro+CT arm (40.9%): CT: 31.3%, EGFRi: 13.2%, ICIs:4.3%, other: 2.9% | – | |||||||

| Pembro + CT (n = 281) vs. EXTREME (n = 278) | CPS ≥20 | 42.9% vs. 38.2% | PFS: 5.8 vs. 5.3; OS: 14.7 vs. 11 | Pembro + CT arm PFS2a longer in: CPS ≥20: 11.3 vs. 9.7; CPS ≥1: 10.3 vs. 8.9; TP: 10.3 vs. 9 | |||||||

| CPS 1–19 | 29.3% vs. 33.6% | PFS: 4.9 vs. 4.9; OS:12.7 vs. 9.9 | EXTREME arm (53%): CT: 34%, EGFRi: 6.3%, ICIs: 16.7%, other: 3% | – | |||||||

| TP | 35.6 vs. 36.3% | PFS: 4.9 vs. 5.1; OS: 13 vs. 10.7 | |||||||||

| Current series | n = 23 | N = 10, EXTREME: 6, ERBITAX: 4 | ORR:40% | PFS: 6 m (IC95% 3‐NR) | Anti‐PD1: 52.1%; anti‐PDL1: 13%; anti‐PDL1 + iSTAT3: 30.4%; anti‐PDL1 + iCXCR2: 4.3% | – | – | n = 23; ERBITAX: 17; EXTREME: 2; CARBITAX: 2; wkCDDP‐Cetuximab: 2 | ORR (all): 56.5% (13/23); ORR (LCBI pretreated): 60% (6/10) | PFS: 6 mo (95% CI, 5–8); OS: 12 mo (95% CI, 9‐NR) | |

| Case Reports | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | N/Location/Stage/Tx IDx | LCBI | First IO | First SCAI | Second IO | Second SCAI | |||||

| Daste et al. (2017) [20] | 64 y/OC/ local relapse | EXTREME × 6 cycles ➔ PR ➔ Cetuximab × 12 mo | Anti‐PD1 (Nivolumab) × 6 ➔ PD ➔ × 5 ➔PD | CBDCA AUC5 d1 + Pac d1, 8, 15 × 2 cycles ➔ major PR | – | – | |||||

| Daste et al. (2018) [21] | ‐/HP/IVA/TPF ➔BRT | Relapsed after 6 mo ➔ EXTREME × 6 cycles ➔ PR ➔ PD ➔ EXTREME ➔ SD | Anti‐PD1 (Nivolumab) × 4 ➔ PD | wkPac × 3 m ➔ major PR | – | – | |||||

| Daste et al. (2018) [21] | 62 y/L/IVA/BRT ➔ SX | C‐PF × 6 wk ➔ PR ➔EXTREME × 12 wk ➔ PD ➔ Cetuximab × 6 m ➔ PD; PR | Anti‐PD1 (Nivolumab) × 4 ➔ PD | wkPac x 3 m ➔ major PR | – | – | |||||

| Larroquette et al. (2018) [22] | 52 y/MS/IVA/SX ➔ RT + CDDP | – |

LR relapse 3 mo after POCRT ➔ Anti‐PD1 (CT) × 4 (2 mo) ➔ PD |

EXTREME x 6 cycles ➔ major PR | – | – | |||||

| Lasserre et al. (2019) [23] | 51 y/HP/IVC at IDx | – |

Anti‐PD(L)1 + Anti‐CTLA4 (CT) ➔ SD ➔ PD |

EXTREME × 6 cycles ➔ major PR | Anti‐PD1 (Nivolumab) × 3 ➔ PD | CBDCA‐Pacli × 3 cycles ➔ PR (ongoing after 3 additional cycles) | |||||

Blue cells represent IO lines and adjacent brown cells indicate either LCBI or SCAI.

PFS2 indicates PFS calculated from initial randomization in KEYNOTE‐048 (from the start of first‐line therapy).

Abbreviations: (–), not applicable; AUC, area under the concentration curve; BRT, bioradiotherapy; CBDCA, carboplatin; CT, clinical trial; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HP, hypopharynx; IDX, initial diagnosis; IO, immunotherapy; LCBI, last chemotherapy before immunotherapy; MS, maxillary sinus; NR, not reached; OC, oral cavity; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; PFS, progression‐free survival; RT, radiotherapy; SCAI, salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy; SD, stable disease; SX, surgery.

Erbitax

Among 17 patients treated with ERBITAX, median number of paclitaxel and cetuximab weekly cycles were 12 and 15, and median dose per cycle was 75 mg/m2 and 400 mg/m2 (load) and 225 mg/m2 (follow), respectively. Median number of maintenance cetuximab was 14, with a median dose per 2‐weekly cycles of 500 mg/m2 (Table 4; supplemental online Table 1).

Other Regimens

Among six patients treated with other regimens, mean doses of chemotherapy were also reduced to a variable extent depending on the regimen used.

Table 4 summarizes data on dose intensity and compliance. Supplemental online Table 1 shows data for each individual patient.

Toxicity During SCAI

In the whole series of 23 patients, grade 1 or 2 AEs occurred in 100%. Grade 3 or 4 AEs developed in 65%, being grade 3 in all of them except in one patient (grade 4 neutropenia). There were no treatment‐related deaths.

Among patients treated with ERBITAX (n = 17), AEs of grades 1 or 2 occurred in 100% of the patients, the most common being asthenia, decreased appetite, and acneiform rash. Grade 3 or 4 AEs occurred in 64.7% of the patients, the most common being acneiform rash (23.5%), pneumonia (23.5%), anemia, neutropenia, lymphopenia, and tumor bleeding (12% each). One patient experienced a grade 4 AE (neutropenia).

Among patients treated with other regimens of SCAI (n = 6), all patients experienced grade 1 or 2 AEs, and four (67%) patients suffered grade 3 AEs. A patient treated with CARBITAX suffered grade 3 hemoptysis from a lung metastasis bleeding. There were no grade 4 AEs.

Therefore, grade 3 bleeding occurred in 3 (ERBITAX [n = 2], CARBITAX [n = 1]) of the 23 patients (13%). In the two patients treated with ERBITAX, both with bulky and friable tumors, bleeding was judged to be due to rapid tumor reduction.

Table 4 and supplemental online Table 2 in the supplementary appendix summarize adverse events during SCAI in the whole population and in each individual patient, respectively.

Case Reports

Case A (Patient 15)

A 69‐year‐old man diagnosed with an oral cavity primary suffered a local and distant (lung, liver, lymph node, and bone) early relapse only 2 months after ending 3‐weekly platinum‐based CRT. He received two doses of nivolumab with rapid radiological and symptomatic progression (intense laterocervical pain requiring opioids) suggesting hyperprogressive disease. Treatment with weekly ERBITAX was started 3 weeks after the last dose of nivolumab, with an overall PR after seven doses and a maximum reduction in TL of 62%. After 8 months, the patient progressed and, because of the limited therapeutic options, he was rechallenged with nivolumab for 3 months with PD as best response, after which ERBITAX was reintroduced with SD as best response and treatment was maintained for 8.5 months (Fig. 2A; Table 3) .

Figure 2.

Examples of patients treated with SCAI. Each case (A‐E) corresponds to each of the cases described in the main text.Abbreviations: CMR, complete metabolic response; CR, complete response; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RT, radiotherapy; SCAI, cetuximab‐based salvage chemotherapy after immunotherapy; SCCHN, squamous cell cancer of the head and neck; SD, stable disease; TL, target lesions.

Case B (Patient 6)

A 68‐year‐old man initially diagnosed with a large laryngeal mass, bilateral neck lymphadenopathies, and lung metastases started treatment with a PD‐L1 inhibitor combined with a STAT3 inhibitor within a clinical trial. Although pseudoprogression (PsPD) cannot be disregarded, the patient suffered an overt radiological and clinical progression (ECOG deterioration, intense pain in the neck, and grade 2 asthenia), and thereby he started treatment with weekly ERBITAX. He received 10 doses, achieving major locoregional and pulmonary responses. However, it was considered as PD because of appearance of new hepatic and bone metastases (Fig. 2B; Table 3).

Case C (Patient 14)

A 54‐year‐old man was diagnosed with stage IVA laryngeal cancer. Six months after laryngectomy and adjuvant RT, he suffered a pulmonary and hepatic relapse. Treatment with weekly ERBITAX (with paclitaxel reduced to 50 mg/m2 because of hypersplenism in the context of alcoholic liver disease) achieved PR with a maximum PCTL of −81.5%. After 6 months, the patient suffered PD and started nivolumab, with a PR as best response. After 11 months of nivolumab, the patient suffered PD. Weekly ERBITAX was reintroduced (maintaining paclitaxel reduced to 50 mg/m2) achieving a PR (−30.9%) as best response, eventually starting maintenance cetuximab achieving 20 months under this line of therapy. After progression, he restarted treatment with nivolumab (Figure 2C; Table 3).

Case D (Patient 4)

A 70‐year‐old woman received induction CT with weekly ERBITAX for a stage IVB oral cavity cancer. After radical concurrent RT plus cetuximab, the patient suffered a local relapse, starting treatment with a PD‐L1 inhibitor within a clinical trial. After an overt local and distant radiological and clinical progression (intense local pain, macroglossia, grade 2 asthenia, and ECOG deterioration), weekly ERBITAX was started (with paclitaxel reduced to 70 mg/m2 because of ECOG 2), achieving a major local response and rapid symptomatic improvement (pain disappeared) but with hepatic progression (PD as overall response). Because of the symptomatic improvement treatment with ERBITAX was maintained for 9 months (Fig. 2D; Table 3).

Case E (Patient 21)

A 74‐year‐old man diagnosed with an SCCHN of unknown primary relapsed 18 months after surgery and adjuvant RT. Treatment with EXTREME regimen was started with PD after two cycles. Nivolumab was started, but the patient suffered PD after three doses (growth of right neck mass, appearance of C5–C6 bone metastases, and right neck intense pain, which made PsPD less likely). Three weeks after the last dose of nivolumab, ERBITAX was started. After four doses of weekly ERBITAX (second dose without paclitaxel because of G2 neutropenia) a CR with complete metabolic response (CMR) was achieved. The patient continued with maintenance 2‐weekly cetuximab for 14 cycles, achieving a sustained CR and CMR (Fig. 2E; Table 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective series of 23 patients with R/M SCCHN, in which 56.5% had received IO in the first line, 30.4% were platinum‐refractory, and 74% received weekly ERBITAX as SCAI, we show a 53% ORR to salvage cetuximab‐based chemotherapy after an overt clinical and radiological progression to PD(L)1 inhibitors. This 53% ORR to SCAI in second or third line, is notable, considering that cetuximab‐based 3‐weekly regimens such as EXTREME and TPEx, or weekly regimens like ERBITAX, achieve ORR in the first‐line setting of 36%, 46% and 55%, respectively [27, 28, 29]. In a French series of 82 heavily pretreated patients with R/M SCCHN, in which 76% had received at least one line of chemotherapy pre‐IO and a majority were platinum‐refractory, Saleh et al. [18], found a 30% ORR to SCAI, which raised to 53% with cetuximab‐based chemotherapy. Likewise, in a series from the U.S. of 43 patients with R/M SCCHN, in which 58% had received first‐line IO and 60% were platinum‐refractory, Pestana et al. [19], found a 42% ORR to SCAI and, interestingly, a 37% ORR with single‐agent cetuximab. In our series, SCAI consisted, in all patients, of cetuximab‐based chemotherapy, and thus, efficacy could not be compared with a control group receiving chemotherapy alone. However, ORR was comparable to that of patients treated with cetuximab‐based regimens in the French series (ORR, cetuximab‐based vs. noncetuximab‐based: 53% vs. 25%) [18].

Our results and those from the other series suggest a possible additive effect between IO and subsequent SCAI in terms of ORR, which may also be illustrated by comparing responses to chemotherapy before and after IO. In our study, ORR and PFS with LCBI were 40% and 8 months, whereas ORR and PFS with SCAI in LCBI‐treated patients achieved 60% and 7 months, respectively. These results agree with those reported by other authors in patients with lung cancer. Schvartsman et al. [9], in a series of 28 patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), reported an ORR and PFS to LCBI (platinum‐doublet) of 37% and 7.3 months, whereas ORR and PFS to single‐agent SCAI were 39.3% and 4.7 months, respectively. Likewise, in another series of 78 patients with NSCLC by Park et al. [10], ORR with SCAI was higher than with LCBI (53.4% vs. 34.9%), and PFS with LCBI and SCAI were similar (4.2 vs. 4.7 months, p = .84).

Despite the few existing data regarding the depth of responses with chemotherapy in SCCHN in patients both pretreated and non‐pretreated with IO, responses to SCAI in our series showed a median PCTL of −57.5% (range, −30 to −100), which is deeper than the median PCTL of −40% reported by Enokida et al. [30], in a Japanese series of 23 platinum‐refractory patients receiving first‐line ERBITAX, the most frequently used SCAI in our series. Although only 30.4% of the patients in our series were platinum‐refractory, all, per definition, were more pretreated because they received SCAI as second or further line.

Interestingly, we found that ORR to SCAI was significantly higher in patients pretreated with PD‐1 than with PD‐L1 inhibitors. Although potential differences in efficacy between PD1 and PDL1 inhibitors cannot be disregarded in the absence of head‐to‐head comparisons, the differences in ORR observed in our series may probably be explained because all patients receiving PDL1 inhibitors were treated within clinical trials, which usually constitute a highly selected population based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria and are subjected to a generally more intensive surveillance [2, 3, 4, 31, 32]. This might lead to a longer time on treatment and to the emergence of tumor‐cell resistance mechanisms as well as of an immunosuppressive “milieu” that renders the tumor less responsive to subsequent therapies [33]. Indeed, in our series, patients treated with PD‐1 inhibitors outside clinical trials (most treated with nivolumab) received a median of six cycles (range, 2–26), which indicates a relatively early switch to SCAI, increasing the likelihood that PsPD may go undetected. However, PsPD is infrequent in SCCHN (only 4%–8% of patients achieving a partial response) [34]. In contrast, median time to the start of SCAI in the whole population was only 16 days, a rather short time in which, because of their long half‐life, most PD(L)1 inhibitors may still be rendering direct therapeutic effects: median half‐life ranges from 17 to 27 days [35, 36, 37]. Finally, data from CheckMate‐141 showed that patients progressing to nivolumab without ECOG deterioration and who were nonrapid progressors treated beyond progression may experience a longer survival and in some cases even late responses, suggesting that beneficial effects of IO may persist long time, and thereby explaining some of the responses seen with subsequent treatments [38]. However, all of our patients were switched to SCAI because of a radiological progression with ECOG deterioration, suggesting a true progression and rendering the possibility of PsPD less likely [34]. Although at the start of SCAI, nearly 70% of our patients had ECOG ≥2, most patients showed an improvement in the performance status during SCAI because of clinical benefit. In addition, comorbidity assessment using GCE‐COS at the start of SCAI revealed that 87% of patients had a score that justified to start antitumor treatment [24].

Although in the French series, patients treated with first‐line IO showed a higher ORR to SCAI than those treated in second line (40% vs. 27%), we found no differences in our series between those treated with first‐ versus further lines (58.3% vs. 54.5%). This may be explained because our patients were less heavily pretreated and thus more prone to respond to SCAI.

Finally, although limited by the reduced sample size, PD‐L1 expression in tumor cells (<1 vs. ≥1) was not different between responders and nonresponders. Although the same immunohistochemistry assay was used in all patients, the interval between the biopsy sample and the start of SCAI, and not testing the CPS, a more reliable biomarker in SCCHN, may also limit any conclusions.

In our series, responses and survival were durable, with a median PFS and OS since the start of SCAI of 6 and 12 months, respectively, which are notable considering that patients had received, per definition, at least one line of systemic therapy before SCAI. In the French series, median PFS and OS were 3.6 and 7.8 months, and in the U.S. series, they were 4.2 and 8.4 months, respectively [18, 19]. Although both PFS and OS with SCAI were longer in our series, this may be explained because our patients were less heavily pretreated and a majority received additional lines of therapy after SCAI, with up to 14 patients being rechallenged with IO and 10 of these being treated with a second cetuximab‐based SCAI. In contrast, in the KEYNOTE‐048 study, progression‐free survival 2 (PFS2), calculated from initial randomization, in the intention‐to‐treat population was significantly longer in the pembrolizumab arm, with a median PFS2 of 11.7 and 9 months for CPS ≥20 and CPS ≥1, respectively, as well as in the pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy arm, with a median PFS2 of 11.3, 10.3, and 10.3 months for CPS ≥20, CPS ≥1, and total populations, respectively. These results are even more relevant if we consider that only around half of the patients in KEYNOTE‐048 received second‐line therapy [8]. In contrast with the latter study, in our series, PFS was calculated from the start of SCAI and not from the start of IO and, therefore, is not readily comparable. However, and considering all the limitations of our small retrospective series, the 6‐month median PFS achieved in our study is notable considering that with first‐line regimens such as EXTREME, TPEx, and ERBITAX, median PFS was 5.6 months, 6 months, and 4.2 months, respectively [27, 28, 29]. In KEYNOTE‐048, median OS in the CPS ≥20 population was 14.8 and 14.7 months in the pembrolizumab and pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy arms, respectively. Interestingly, in our series, median OS since first‐line treatment achieved 28 months, with no differences in first‐line OS between those receiving IO in first‐line versus second‐line. Although our results cannot be reliably compared with those from a large phase III trial, the fact that only half of the patients in KEYNOTE‐048 received second‐line therapy after IO, whereas in our series, the median number of treatment lines was four, with up to 60% of our patients receiving additional therapies after SCAI, may explain the prolonged survival times achieved. In contrast, in TPExtreme phase III trial, comparing TPEx with EXTREME in the first‐line setting, survival was longer for patients treated with IO as second‐line compared with those treated with chemotherapy, and it was also longer with IO in second‐line in patients from the TPEx arm compared with the EXTREME arm (21.9 vs. 19.4 months) [39]. Results from the mentioned studies and from our series open the question of whether not only chemoimmunotherapy combinatorial strategies but also a sequential approach of IO followed by chemotherapy or vice versa, and even reintroducing a second IO followed by a second SCAI, may be worth exploring in future clinical trials. In this regard, some trials are studying if reintroducing chemotherapy after progression on immunotherapy and then returning to immunotherapy is a feasible approach [NCT03083808].

It must be noted that the high ORR and survival in our series occurred despite a large majority of patients receiving weekly chemotherapy regimens with doses reduced because of poor performance status or because of advanced age or comorbidities. According to these observation, reducing dose intensity of chemotherapy could be explored in future chemoimmunotherapy trials as a strategy to reduce toxicity while maintaining efficacy.

Several aspects may constitute the biological rationale to explain why IO may favor responses to SCAI in patients with SCCHN. SCCHN is characterized by a highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) mainly composed of myeloid‐derived suppressor cells and T regulatory cells that impede tumor eradication by the immune system and explain the appearance of acquired resistance to ICIs. Besides direct tumor cell killing, chemotherapies like platinums or taxanes may favor tumor‐antigen presentation and reduce the immunosuppressive component of the TME, allowing to emerge a more effective antitumor immune response [40, 41, 42]. Although in our series, during SCAI, some patients received either cisplatin or carboplatin combinations, most patients received ERBITAX, a weekly regimen consisting of paclitaxel and cetuximab [29]. Besides the direct antitumor effects of paclitaxel, the latter is also known for behaving as a toll‐like receptor agonist capable of reprogramming immunosuppressive macrophages toward an immune‐effector phenotype [40, 43, 44]. Another possible contributor to the high ORR with SCAI seen in our study is the use of cetuximab, which is known not only for targeting EGFR but for being able to induce antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [43, 45, 46]. ADCC is mediated by natural killer (NK) cells, and SCCHN is characterized by a deep infiltration by these cells [47]. In contrast, it is also possible that treatment with ICIs before SCAI could enhance the ADCC effect of cetuximab [43]. Recently, the combination of cetuximab plus monalizumab, an NK cell inhibitory‐checkpoint inhibitor, showed a 27.5% ORR and a median OS of 10.3 months [48]. In addition, the combination of pembrolizumab plus cetuximab showed promising activity in patients with R/M SCCHN, achieving a 45% ORR and a median OS of 18.4 months [49].

Although with limitations due to the retrospective nature of our study, toxicity during SCAI was comparable to that already known for the regimens used. It must be noted, however, that three patients suffered grade 3 tumor bleeding, which was effectively managed with conservative measures, and that in two of the patients, both with a high tumor burden, bleeding was considered to be associated with the rapid tumor reduction observed with SCAI. Therefore, patients should be closely followed at least during the first cycles of treatment, especially in case of large, friable tumors or tumors located near large vessels that may render them more prone for such complications.

In our study, we show that benefit from IO may occur “after” treatment with ICIs, possibly conditioning response rates and survival with subsequent lines of therapy. These findings are relevant considering the importance of achieving high response rates and deep tumor reductions for improving patients’ symptoms and quality of life and possibly prolonging survival.

Although, to our knowledge, this is currently the fourth largest study evaluating the efficacy and the first evaluating toxicity and treatment compliance of salvage chemotherapy after PD(L)1 inhibitors in head and neck cancer, we must acknowledge several limitations. Our results are limited by the retrospective nature and reduced sample size and by the heterogeneity of our population, as some patients were treated with IO in first line whereas others in second or further lines, and different immunotherapy drugs and combinations (PD‐1, PD‐L1, CTLA4, STAT3, CXCR2 inhibitors) as well as different regimens of SCAI were used. In addition, because of the retrospective nature, patients in our series may be exposed to selection bias, because patients able to receive SCAI are highly selected and possibly selected to do better. As already mentioned, early switch to SCAI since the start of IO and a short interval between last IO doses and SCAI could have conditioned the response rate observed during SCAI. In this regard, comparing pre‐ and post‐SCAI tumor biopsies could help to understand the immunobiological mechanisms underlying responses to SCAI. Unfortunately, pre‐ and post‐SCAI biopsies were not performed because of the retrospective nature of our study. Finally, patients received different systemic therapies after SCAI that may have impacted overall survival results.

Conclusion

Our study describes a higher than expected response rate to cetuximab‐based salvage chemotherapy after progression to IO in patients with R/M SCCHN. In addition, response rates were higher and PFS was maintained during SCAI when compared with LCBI. These results should encourage the design of trials to elucidate the best treatment sequence for patients with head and neck cancer in the IO era, until better, rationally based IO combinations are found.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Santiago Cabezas‐Camarero

Provision of study material or patients: Santiago Cabezas‐Camarero, María Nieves Cabrera‐Martín, Salomé Merino‐Menéndez, Mateo Paz‐Cabezas, Maricruz Iglesias‐Moreno, Almudena Alonso‐Ovies, Vanesa García‐Barberán, Pedro Pérez‐Segura

Collection and/or assembly of data: Santiago Cabezas‐Camarero, María Nieves Cabrera‐Martín, Salomé Merino‐Menéndez, Mateo Paz‐Cabezas

Data analysis and interpretation: Santiago Cabezas‐Camarero, María Nieves Cabrera‐Martín, Salomé Merino‐Menéndez, Mateo Paz‐Cabezas, Vanesa García‐Barberán, Pedro Pérez‐Segura

Manuscript writing: Santiago Cabezas‐Camarero

Final approval of manuscript: Santiago Cabezas‐Camarero, María Nieves Cabrera‐Martín, Salomé Merino‐Menéndez, Mateo Paz‐Cabezas, Maricruz Iglesias‐Moreno, Almudena Alonso‐Ovies, Vanesa García‐Barberán, Pedro Pérez‐Segura

Disclosures

Santiago Cabezas‐Camarero: Bristol Myers Squibb, Sanofi (C/A), Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca (ET), Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck KGaA, Abbvie (Other [Scientific meeting travel arrangement]). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Table S1 Treatment compliance during salvage cetuximab‐based chemotherapy after immunotherapy (SCAI) for each individual patient.

Table S2. Adverse events during treatment with salvage cetuximab‐based chemotherapy after immunotherapy (SCAI) for each individual patient.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact commercialreprints@wiley.com.

References

- 1. Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Fayette J et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous‐cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1856–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen EEW, Soulières D, Le Tourneau C et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head‐and‐neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE‐040): A randomised, open‐label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019;393:156–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zandberg DP, Algazi AP, Jimeno A et al. Durvalumab for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Results from a single‐arm, phase II study in patients with ≥25% tumour cell PD‐L1 expression who have progressed on platinum‐based chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2019;107:142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferris RL, Haddad R, Even C et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: EAGLE, a randomized, open‐label phase III study. Ann Oncol 2020;31:942–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Siu LL, Even C, Mesía R et al. Safety and efficacy of durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in patients with PD‐L1‐low/negative recurrent or metastatic HNSCC: The phase 2 CONDOR randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE‐048): A randomised, open‐label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019;394:1915–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paz‐Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2040–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harrington, KJ ., Rischin, D , Greil, R et al. KEYNOTE‐048: Progression after the next line of therapy following pembrolizumab (P) or P plus chemotherapy (P+C) vs EXTREME (E) as first‐line (1L) therapy for recurrent/metastatic (R/M) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). J Clin Oncol 2020;38(15_suppl):6505a. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schvartsman G, Peng SA, Bis G et al. Response rates to single‐agent chemotherapy after exposure to immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2017;112:90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park SE, Lee SH, Ahn JS et al. Increased response rates to salvage chemotherapy administered after PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors in patients with non–small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grigg C, Reuland BD, Sacher AG et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) receiving chemotherapy after immune checkpoint blockade. J Clin Oncol 35(suppl):9082a. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leger PD, Rothschild S, Castellanos E et al. Response to salvage chemotherapy following exposure to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(suppl):9084a. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dwary AD, Master S, Patel A et al. Excellent response to chemotherapy post immunotherapy. Oncotarget 2017;8:91795–91802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simon A, Kourie HR, Kerger J. Is there still a role for cytotoxic chemotherapy after targeted therapy and immunotherapy in metastatic melanoma? A case report and literature review. Chin J Cancer 2017;36:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aspeslagh S, Matias M, Palomar V et al. In the immuno‐oncology era, is anti‐PD‐1 or anti‐PD‐L1 immunotherapy modifying the sensitivity to conventional cancer therapies? Eur J Cancer 2017;87:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cabezas‐Camarero S, Pérez‐Alfayate R, Puebla F et al. Increased clinical and plasma EBV DNA responses to platinum‐gemcitabine after nivolumab in patients with heavily platinum‐pretreated nasopharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol 2020;103:104527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chakrabarti S, Dong H, Paripati HR et al. First report of dramatic tumor responses with ramucirumab and paclitaxel after progression on pembrolizumab in two cases of metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. The Oncologist 2018;23:840–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saleh K, Daste A, Martin N et al. Response to salvage chemotherapy after progression on immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Eur J Cancer 2019;121:123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pestana RC, Becnel M, Rubin ML et al. Response rates and survival to systemic therapy after immune checkpoint inhibitor failure in recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2020;101:104523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Daste A, de Mones E, Digue L et al. Immunotherapy in head and neck cancer: Need for a new strategy? Rapid progression with nivolumab then unexpected response with next treatment. Oral Oncol 2017;64:e1–e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Daste A, De‐Mones E, Cochin V et al. Progression beyond nivolumab: Stop or repeat? Dramatic responses with salvage chemotherapy. Oral Oncol 2018;81:116–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Larroquette M, Domblides C, Cousin S et al. Dramatic response after anti PD1 treatment failure in a squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary sinus. Oral Oncol 2018;87:207–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lasserre M, Domblides C, Gross‐goupil M et al. The interest of sequential treatment with immune check point inhibitors followed chemotherapy: A case report. Oral Oncol 2019;94:125–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vitzthum LK, Feng CH, Noticewala S et al. Comparison of comorbidity and frailty indices in patients with head and neck cancer using an online tool. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2018;2:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsimberidou AM, Levit LA, Schilsky RL et al. Trial reporting in immuno‐oncology (TRIO): An American society of clinical oncology‐society for immunotherapy of cancer statement. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vermorken JB, Remenar E, van Herpen C et al. Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1695–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guigay J, Fayette J, Mesia R et al. TPExtreme randomized trial: TPEx versus Extreme regimen in 1st line recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (R/M HNSCC). J Clin Oncol 2019;37(15_suppl):6002a. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hitt R, Irigoyen A, Cortes‐Funes H et al. Phase II study of the combination of cetuximab and weekly paclitaxel in the first‐line treatment of patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1016–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Enokida T, Okano S, Fujisawa T et al. Paclitaxel plus cetuximab as 1st line chemotherapy in platinum‐based chemoradiotherapy‐refractory patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Front Oncol 2018;8:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr, Fayette J et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous‐cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1856–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duan J, Cui L, Zhao X et al. Use of immunotherapy with programmed cell death 1 vs programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:375–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fares CM, Van Allen EM, Drake CG et al. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade: Why does checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy not work for all patients? Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2019;39:147–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lauber K, Dunn L. Immunotherapy mythbusters in head and neck cancer: The abscopal effect and pseudoprogression. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2019;39:352–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. OPDIVO (nivolumab) Injection label . 2014. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/125554lbl.pdf.

- 36. KEYTRUDA (pembrolizumab) Injection label . 2016. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/125514s012lbl.pdf.

- 37. IMFINZI (durvalumab) Injection label . 2017. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/761069s000lbl.pdf.

- 38. Haddad R, Concha‐Benavente F, Blumenschein G Jr et al. Nivolumab treatment beyond RECIST‐defined progression in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in CheckMate 141: A subgroup analysis of a randomized phase 3 clinical trial. Cancer 2019;125:3208–3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guigay J, Fayette J, Mesia R et al. TPExtreme randomized trial: Quality of Life (QoL) and survival according to second‐line treatments in patients with recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (R/M HNSCC). J Clin Oncol 2020;38(15_suppl):6507a. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Galluzzi L, Senovilla L, Zitvogel L et al. The secret ally: Immunostimulation by anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012;11:215–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Allen CT, Clavijo PE, Van Waes C et al. Anti‐tumor immunity in head and neck cancer: Understanding the evidence, how tumors escape and immunotherapeutic approaches. Cancers (Basel) 2015. 9;7:2397–2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Voorwerk L, Slagter M, Horlings HM et al. Immune induction strategies in metastatic triple‐negative breast cancer to enhance the sensitivity to PD‐1 blockade: The TONIC trial. Nat Med 2019;25:920–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ferris RL, Lenz HJ, Trotta AM et al. Rationale for combination of therapeutic antibodies targeting tumor cells and immune checkpoint receptors: Harnessing innate and adaptive immunity through IgG1 isotype immune effector stimulation. Cancer Treat Rev 2018;63:48–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cohen EE, Nabell L, Wong DJ et al. Phase 1b/2, open label, multicenter study of intratumoral SD‐101 in combination with pembrolizumab in anti‐PD‐1 treatment naïve patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). J Clin Oncol 2019;37(15_suppl):6039a. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lattanzio L, Denaro N, Vivenza D et al. Elevated basal antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and high epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression predict favourable outcome in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer treated with cetuximab and radiotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:573–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lu S, Concha‐Benavente F, Shayan G et al. STING activation enhances cetuximab‐mediated NK cell activation and DC maturation and correlates with HPV+status in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol 2018;78:186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mandal R, Şenbabaoğlu Y, Desrichard A et al. The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI Insight 2016;1:e89829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fayette J, Lefebvre G, Posner MR et al. Results of a phase II study evaluating monalizumab in combination with cetuximab in previously treated recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (R/M SCCHN). Ann Oncol 2018; 29(suppl 8):viii374. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sacco AG, Chen R, Ghosh D et al. An open‐label, non‐randomized, multiarm, phase II trial evaluating pembrolizumab combined with cetuximab in patients with recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Updated results of cohort 1 analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;106:1121–1122. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data