Abstract

Background

Although current guidelines advocate early integration of palliative care, symptom burden and palliative care needs of patients at diagnosis of incurable cancer and along the disease trajectory are understudied.

Material and Methods

We assessed distress, symptom burden, quality of life, and supportive care needs in patients with newly diagnosed incurable cancer in a prospective longitudinal observational multicenter study. Patients were evaluated using validated self‐report measures (National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer [DT], Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy [FACT], Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life [SEIQoL‐Q], Patients Health Questionnaire‐4 [PHQ‐4], modified Supportive Care Needs Survey [SCNS‐SF‐34]) at baseline (T0) and at 3 (T1), 6 (T2), and 12 months (T3) follow‐up.

Results

From October 2014 to October 2016, 500 patients (219 women, 281 men; mean age 64.2 years) were recruited at 20 study sites in Germany following diagnosis of incurable metastatic, locally advanced, or recurrent lung (217), gastrointestinal (156), head and neck (55), gynecological (57), and skin (15) cancer. Patients reported significant distress (DT score ≥ 5) after diagnosis, which significantly decreased over time (T0: 67.2%, T1: 51.7%, T2: 47.9%, T3: 48.7%). The spectrum of reported symptoms was broad, with considerable variety between and within the cancer groups. Anxiety and depressiveness were most prevalent early in the disease course (T0: 30.8%, T1: 20.1%, T2: 14.7%, T3: 16.9%). The number of patients reporting unmet supportive care needs decreased over time (T0: 71.8 %, T1: 61.6%, T2: 58.1%, T3: 55.3%).

Conclusion

Our study confirms a variable and mostly high symptom burden at the time of diagnosis of incurable cancer, suggesting early screening by using standardized tools and underlining the usefulness of early palliative care.

Implications for Practice

A better understanding of symptom burden and palliative care needs of patients with newly diagnosed incurable cancer may guide clinical practice and help to improve the quality of palliative care services. The results of this study provide important information for establishing palliative care programs and related guidelines. Distress, symptom burden, and the need for support vary and are often high at the time of diagnosis. These findings underscore the need for implementation of symptom screening as well as early palliative care services, starting at the time of diagnosis of incurable cancer and tailored according to patients’ needs.

Keywords: Palliative care, Symptom burden, Quality of life, Distress, Cancer

Short abstract

Guidelines recommend early integration of palliative care in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer. This study assessed distress, symptom burden, quality of life, and supportive care needs in patients with newly diagnosed incurable cancer to facilitate future implementation of more effective palliative care services.

Introduction

National and international guidelines recommend early integration of palliative care in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Numerous studies underscore the positive effects of early integration of palliative care [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. Positive effects include improved symptom control and psychological well‐being (less depression and anxiety); better quality of life of patients, relatives, and caregivers; less overtreatment and aggressive care at the end of life [10]; reduced hospital stays; higher treatment satisfaction of patients and their relatives; diminution of the burden on caregiving relatives; and reduction of medical costs [6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16].

Even though the efficacy has been proven for patients with cancer, early palliative care is not yet universally available. Information on symptom burden and care needs of patients is incomplete, hampering the implementation of palliative care services.

To develop individual palliative care concepts, similarities and differences between different types of cancers with their disease‐specific effects on the well‐being of patients must be taken into account. Temel and colleagues [17] reported greater effects of early palliative care interventions in patients with newly diagnosed lung and gastrointestinal cancers if these were specifically adapted to the needs of the respective patient population. Additionally, other studies described that effects depend on the psychosocial, cultural, and ethnic background of patients, their family situation, and place of residence (e.g., urban versus rural areas) [18, 19, 20].

Although an increasing number of studies shed light on needs and symptom burden, care needs, and preferences of patients at the end of life [21, 22], surprisingly little is known about the time period immediately after diagnosis of incurable cancer and how these change over the disease trajectory. This knowledge is important to provide adequate, individualized palliative care.

Therefore, the working group on palliative medicine (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Palliativmedizin) of the German Cancer Society initiated a prospective observational multicenter network study to clarify the symptom burden and palliative care needs of patients with newly diagnosed incurable cancer and followed them during the first year after diagnosis. We assessed quality of life, anxiety, depression, and distress to facilitate future implementation of more effective palliative care services.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting

The study was designed as a multicenter, prospective, longitudinal, observational study, which was activated at 22 sites. Selected cancer treatment centers reflect the different areas of the medical health care landscape, reaching from the university to the community environment and from outpatient to inpatient care. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02751723) and approved by the responsible ethics committees of all participating centers. All patients gave their written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Patient Selection Criteria

Individuals were eligible if they had a confirmed diagnosis of incurable cancer (metastatic, locally advanced, or recurrent). They were 18 years or older, not affected by immediately life threating complications of cancer, and were able to speak and read German. Exclusion criteria included severe physical, cognitive, and/or verbal impairments that interfered with the ability to give informed consent for research and to comply with study requirements.

Patients were enrolled after diagnosis of incurable cancer and before start of any anticancer therapy.

Data Collection

Data were collected at four time points: T0 at baseline and at three (T1), six (T2), and 12 (T3) months follow‐up. Patients were asked to answer questionnaires either Web or paper‐and‐pencil based. Additionally, medical data including demographics, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), cancer diagnosis, and cancer treatment were provided by the treating physicians and documented in a case report form.

Data were pseudonymously stored in a central study database, audited for accuracy, and analyzed using SPSS v. 24.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and Microsoft Excel version 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Measures

The global level of patients’ psychological distress during the past week was assessed using the single item visual analog scale of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT), ranging from 0 (“no distress”) to 10 (“extreme distress”). A score of ≥5 at the visual analog scale is recommended as a cut off for a clinically significant level of distress [23].

Anxiety and depression were assessed by the ultrashort Patients Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐4, [24, 25]). The 4‐items measure comprises the 2‐item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐2), which contains the diagnostic core criteria for depressive disorder, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder containing the two core criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. PHQ‐4 total score can range from 0 to 12. It categorizes psychological distress as none (0–2), mild (3–5), moderate (6–9), and severe (10–12). A total score above the cutoff 6 indicates a higher risk for anxiety and depression [25].

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General (FACT‐G) with organ‐specific modules was used to analyze patients’ symptom burden and health‐related quality of life (QoL) [26, 27]. The FACT‐G questionnaire contains 27 questions grouped in four different quality of life domains: physical well‐being, social and family well‐being (SWB), emotional well‐being (EWB), and functional well‐being (FWB). Answers are given according to a five‐point rating scale (0: not at all to 4: very much). Domain‐specific scores range from 0 to 28 (except EWB: 0–24). The QoL total score, which ranges from 0 to 108, is obtained from the results of the four subdomains and is calculated if at least 80% of the questions were answered. The lower the score value, the worse the patient's well‐being.

The Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQoL) assesses the importance and satisfaction of some aspects of daily life. On a 5‐point Likert scale, the patients were asked to weigh 12 life domains regarding their importance and how satisfied they were with these domains ranging from 0 (not at all) to 100 (extremely important/satisfied). An individual Life‐Quality‐Index can be calculated on a range from 0 to 100, with higher scores expressing higher QoL [28, 29].

To assess patients’ care needs, a shortened and modified Supportive Care Needs Survey consisting of 25 items was used. The questionnaire covers the following domains: psychological, health system and information, physical and daily life, patient care and support, and sexuality. Patients were asked to range on a 5‐point Likert scale if and to what degree they wish to receive support (1: not applicable, 2: satisfied, 3: low need, 4: moderate need, 5: high need). A score of 3, 4, or 5 indicates an unmet need [30].

Sample Size and Statistics

The intended study size was 500 patients. This was a pragmatic approach decided by the study steering board taking into consideration the power of the network to recruit a robust number of patients in a reasonable time frame. Statistical analyses were performed by SPSS Version 24.0. Descriptive statistics were used to interpret baseline data and to estimate frequencies, means, and SDs. One‐way analysis of variance was performed to test for differences between clinical outcomes in the course of the study. Homogeneity of variances was determined using Levene's test. If equal variances could be assumed, a post hoc analysis using Tukey tests to detect significance (p < .05) was performed. If there was no homogeneity of variances, p values were calculated using Welch's tests and Games‐Howel post hoc analysis.

Results

Study Conduct

Between October 2014 and October 2016, 20 of the 22 activated centers in Germany recruited 500 eligible patients with incurable cancer.

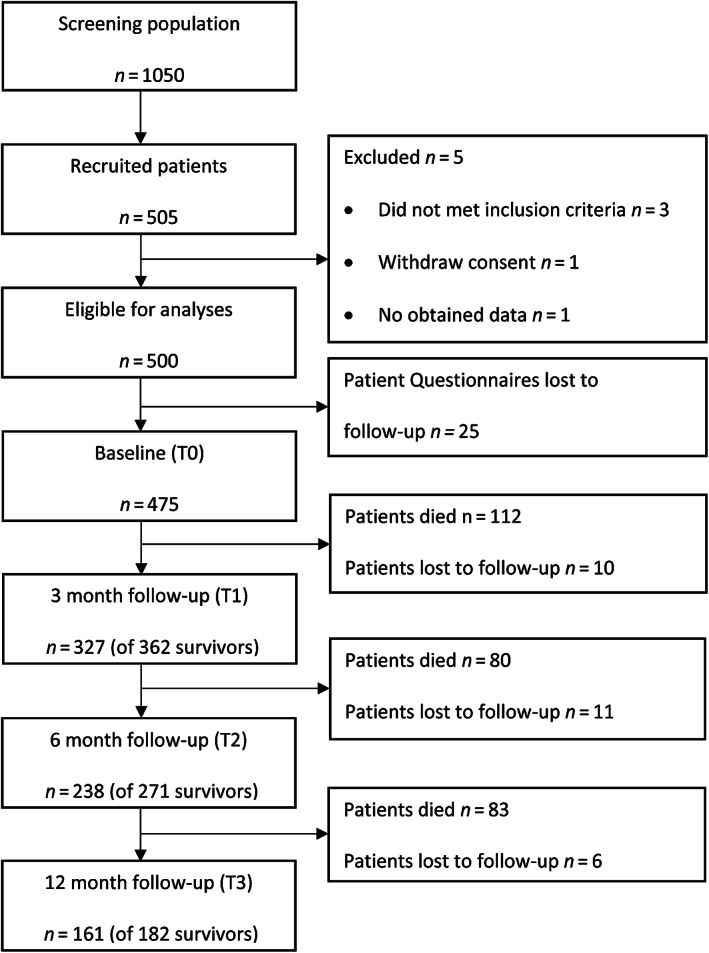

Out of 1,050 screened patients (retrospectively determined number based on recent comparative data from the participating centers), 505 patients (participation rate of 48%) gave their informed consent to participate. Three patients were subsequently excluded from analysis because the inclusion criteria were not fully met, one participant refused participation after having given consent, and for one participant, no baseline data were transmitted. Finally, data from 500 eligible patients were analyzed. The number of evaluable patient questionnaires was 475 (95.0%) at T0, 327 (65.4%) at T1, 238 (47.4%) at T2, and 161 (32.1%) at T3 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study according to CONSORT reporting guidelines.

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 500 study participants. Slightly more men (56.2%) than women (43.8%) were enrolled. The mean age was 64.2 years (range, 25–89). The median ECOG PS was 1, with a range from 0 to 4.

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Variables | Number of patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years (range) | 64.2 (25–89) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 219 (43.8) |

| Male | 281 (56.2) |

| Localization of the primary tumor | |

| Ovary | 13 (2.6) |

| Breast | 44 (8.8) |

| Skin | 15 (3.0) |

| Lung | 217 (43.4) |

| Stomach | 22 (4.4) |

| Esophagus | 20 (4.0) |

| Pancreas | 43 (8.6) |

| Hepatobiliary system | 14 (2.8) |

| Colorectum | 57 (11.4) |

| Head and neck | 55 (11.0) |

| Family status | |

| Married | 337 (67.4) |

| Single | 39 (7.8) |

| Divorced | 44 (8.8) |

| Widowed | 45 (9.0) |

| Unknown | 35 (7.0) |

| Living in a relationship | |

| Yes | 336 (67.2) |

| No | 115 (23.0) |

| Unknown | 49 (9.8) |

| Migrant background | |

| Yes | 20 (4.0) |

| No | 395 (79.0) |

| Unknown | 85 (17.0) |

| ECOG performancestatus | |

| 0 | 103 (20.6) |

| 1 | 250 (50.0) |

| 2 | 105 (21.0) |

| 3 | 30 (6.0) |

| 4 | 3 (0.6) |

| Unknown | 9 (1.8) |

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Distress Level

At baseline, 67.1% of patients reported significant distress (Table 2). Although the mean distress levels declined slightly over time (T0: 5.49 [SD = 2.64], T1: 4.60 [SD = 2.58], T2: 4.36 [SD = 2.52], and T3: 4.34 [SD = 2.85]), approximately half of the patients remained significantly distressed (T1: 51.7%, T2: 47.9%, and T3: 48.7%). When comparing patients with different tumor entities, patients suffering from stomach, esophageal, hepatobiliary, or head and neck cancer showed the highest levels of distress over the entire observation period (supplemental online Table 1).

Table 2.

Results of self‐report questionnaires; mean values, SDs, and p values at diagnosis and during disease trajectory of incurable cancer

| T0 | T1 | p a | T2 | p a | T3 | p a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||||

| NCCN Distress Thermometer b | 459 | 5.49 | 2.60 | 319 | 4.6 | 2.50 | <.001 c | 234 | 4.36 | 2.52 | <.001 c | 154 | 4.34 | 2.85 | <.001 c |

| FACT‐G b (total score) | 455 | 67.91 | 17.52 | 318 | 70.67 | 17.32 | .134 | 232 | 73.93 | 16.95 | <.001 | 156 | 73.75 | 18.69 | .002 c |

| PWB d | 470 | 18.54 | 6.45 | 324 | 18.57 | 6.00 | ˃.999 | 238 | 19.77 | 5.67 | .048 c | 160 | 19.4 | 6.47 | .471 |

| SWB b | 470 | 22.02 | 4.84 | 325 | 22.23 | 4.83 | .936 | 237 | 22.34 | 4.71 | .839 | 159 | 22.31 | 5.03 | .918 |

| EWB b | 463 | 14.24 | 5.52 | 323 | 15.84 | 4.97 | <.001 c | 233 | 16.51 | 4.83 | <.001 c | 159 | 16.55 | 5.19 | <.001 c |

| FWB b | 468 | 13.22 | 6.44 | 323 | 13.87 | 6.51 | .505 | 233 | 15.27 | 6.31 | <.001 c | 159 | 15.51 | 6.54 | .001 c |

| PHQ‐4 d (total score) | 454 | 4.63 | 3.18 | 314 | 3.70 | 2.81 | <.001 c | 224 | 3.30 | 2.62 | <.001 c | 148 | 3.33 | 3.02 | >.999 |

| SEIQoL b (individual QoL index) | 464 | 58.91 | 17.16 | 320 | 60.37 | 17.55 | .648 | 232 | 64.08 | 17.44 | .001 c | 158 | 62.31 | 16.07 | .138 |

| SCNS‐SF34 d (total score) | 442 | 18.28 | 18.57 | 308 | 12.17 | 15.4 | <.001 c | 228 | 11.55 | 15.63 | <.001 c | 150 | 10.46 | 15.39 | <.001 c |

Means compared with baseline visit.

p values were calculated using analysis of variance and Tukey post hoc analysis.

Indicates statistically significant (p < .05)

p values were calculated using Welch's test and Games‐Howel post hoc analysis.

Abbreviations: EWB emotional well‐being; FACT‐G Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General; FWB functional well‐being; PHQ‐4 Physical Health Questionnaire; PWB physical well‐being; SCNS‐SF34 Supportive Care Needs Survey; SEIQoL Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life; SWB social and family well‐being.

Anxiety and Depression

The mean score of the PHQ‐4 at T0 was 4.62 (SD = 3.18; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.33–4.91) and therefore significantly higher than at T1 (3.70; SD = 2.81; 95% CI, 3.39–4.01), T2 (3.30; SD = 2.62; 95% CI, 2.96–3.65) and T3 (3.33; SD = 3.02; 95% CI, 2.84–3.82). Nearly one‐third of patients (30.8%) reported moderate or severe psychological distress at T0. This number decreased over time (T1: 20.1%, T2: 14.7% and T3: 16.9%; supplemental online Fig. 1). The highest numbers of patients with significant anxiety and depression at baseline were found in the head and neck (52.0%), hepatobiliary (37.7%), and esophageal cancer (33.3%) groups (supplemental online Fig. 1). During the observation period, the number of patients with significant anxiety and depression remained higher in patients with head and neck and with esophageal cancer compared with other cancers. Patients with malignant melanoma showed the lowest psychological distress (T0: 7.7%, T1: 11.1%, T2: 0%, and T3: 0%).

A total of 41.4% of patients with moderate or severe psychological distress wished to receive professional support, whereas 55.0% refused it, and 3.6% did not answer this question at T0. However, 16.6% of patients with no or only mild psychological distress also indicated their wish to receive professional psychological support at T0. After 12 months (T3), 48% of patients with high and 8.9% of patients with low psychological distress wanted access to professional palliative and supportive help.

Symptom Burden and Health‐Related Quality of Life

The results of the evaluation of the FACT‐G questionnaires including subscores of the four different quality of life domains are shown in Table 2. At baseline, the FACT‐G total score of the general study population was 67.91 (SD = 17.52; 95% CI, 66.29–69.52) and increased slightly over time (T1: 70.67, SD = 17.32; 95% CI, 68.76–72.59; T2: 73.93, SD = 16.95; 95% CI, 71.73–76.12; T3: 73.75, SD = 18.69; 95% CI, 70.80–76.71). Patients with head and neck cancer and with hepatobiliary cancer had the lowest total score values in comparison with patients with other cancers (supplemental online Table 2). Patients scored lowest for FWB and EWB and highest for SWB during all four visits, independent of the underlying cancer. Figure 2 displays patient statements on specific symptom burden.

Figure 2.

Symptom burden of patients diagnosed with incurable cancer at T0 (baseline) and T3 (after 12 months), measured by the FACT‐G and FACT cancer‐specific questionnaires. Symptom burden refers to items ranked “a little bit,” “some‐what,” and “quite a bit.”

Importance and Satisfaction with Life Domains

The average individual QoL Index determined by SEIQoL‐Q was 58.9 at baseline (SD = 17.14; 95% CI, 57.4–60.5) for the general study population and did not change significantly in the further course (T1: 60.4 (SD = 17.55; 95% CI, 58.4–62.3), T2: 64.1 (SD = 17.44; 95% CI, 61.8–66.3), and T3: 62.3 (SD = 16.1; 95% CI, 59.8–64.8; Table 2). The lowest QoL‐indices were found in patients with head and neck cancer.

Patients reported “family” (86.4, SD = 22.0) and “physical health” (85.7, SD = 18.2) as the most important life domains, followed by “emotional well‐being” (85.0, SD = 17.9), and “home/housing” (83.1, SD = 19.3). The importance of “religion/spirituality” (30.6, SD = 30.4) and “work/occupation” (34.6, SD = 32.3) was lowest. Highest satisfaction scores were found for “family” (78.3, SD = 24.6), “partnership” (75.2, SD = 33.4), and “home/housing” (73.4, SD = 23.1), whereas patients were not at all satisfied with their “physical health” and “emotional well‐being.” These findings remained unchanged at all points of measurement and were not different among the cancer groups. Only “partnership” increased in importance and satisfaction (T3: 85.0, SD = 25.4; 81.4, SD = 23.0; supplemental online Table 3).

Supportive Care Needs

A total of 71.8% of patients reported at least one unmet supportive care need. This number of patients decreased over time (T1: 61.6%, T2: 58.1%, and T3: 55.3%) (Table 2). A total of 10.4% reported a very high number (22–25 out of 25) of unmet needs at baseline, 7.8% at T1, 7.6% at T2, and 5.3% at T3. On average, the patients had 10.9 (SD = 7.64) unmet needs at T0, 9.8 (SD = 7.29) at T1, 9.5 (SD = 7.81) at T2, and 9.1 (SD = 6.99) at T3. At baseline, patients with ovarian and breast cancer had more unmet needs compared with other cancers.

Patients indicated an increased need for support regarding “lack of energy/tiredness,” “uncertainty about the future,” “feeling down or depressed,” and “being informed about things you can do to get well.” At baseline, more than 43% of patients reported need for support for these items. In contrast, patients declared a lower need for support with regard to “pastoral care,” “changes in sexual feeling,” and “changes in sexual relationships” (supplemental online Table 4).

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that two‐thirds of patients who are newly diagnosed with incurable cancer reported significant distress. Therefore, according needs for supportive and palliative care can be postulated for the majority of patients early in the course of the disease. The study realized by de Boer et al. [31] showed a high prevalence of distress (64%), apathy (53%), depressive symptoms (46%), and loneliness (36%) among older patients with metastatic breast cancer and concluded that timely detection by a geriatric assessment or specific screening and interventions for psychosocial problems could potentially increase quality of life for these patients. Also, Carduff et al. [32], who elicited the longitudinal experiences of living and dying with incurable metastatic colorectal cancer by conducting serial interviews with patients for 12 months or until they died, concluded that a palliative care approach should be integrated into oncological and primary care from diagnosis of advanced disease.

The number of patients showing distress declined significantly over the disease trajectory. In a recent study, Cutillo et al. [33] also showed that patients endorsed more distress 1–4 weeks after receiving the diagnosis than at any other time of the disease trajectory. Fang et al. [34] found the relative risk of suicide among patients receiving a cancer diagnosis was 12.6 during the first week and decreased rapidly during the first year after diagnosis. We confirm an urgent need for early access to supportive and palliative care including psychological interventions for patients who are diagnosed with incurable cancer, as stated in various national and international guidelines [1, 2, 3, 4, 5].

Additionally, we found that measures of anxiety and depressive symptomatology also showed the highest value at the time of diagnosis, with decrease during the disease trajectory. Obviously, the patients need professional help especially at the time of diagnosis. The problem is that more than half of the patients showing moderate or severe psychological distress do not wish to get professional support. Whether because of a lack of education about the usefulness of psychosocial support or a stigma associated with mental health care, highly affected patients may not even show interest in or use mental health services [35]. This known discrepancy between a high degree of suffering and low commitment to therapeutic intervention is problematic and should be addressed by low threshold access to professional care.

At the time of diagnosis of incurable cancer, we found a general health‐related quality of life measured by the FACT‐G total score comparable with other studies performed in France and the U.S. [36]. Interestingly, patients with breast cancer, melanoma, and ovarian cancer reported the highest scores, whereas patients with head and neck and hepatobiliary cancers reported the lowest health‐related QoL. This probably underlines the particularly strong physical and psychosocial burden of these cancer patient populations. In contrast, even patients with breast cancer, melanoma, and ovarian cancer show a significant burden compared with the healthy population [37]. Overall, the lowest values were found for the quality of life domains FWB and EWB, thus confirming data from other studies [37, 38]. The data are presented in terms of relationship to the time point of diagnosis of incurable cancer but could also be examined in relationship to proximity to death, because 382 patients died during 1 year and before study completion. Previous research has shown growth in burden of disease with greater proximity to death. Lo et al. [39] found that moderate to severe depressive symptoms were almost three times more common in the final 3 months of life than 1 year or more before death. The levels of burden and distress may be bimodal, peaking early and then rising later with disease progression. This may be obscured because our study sample included those with more and less progressive disease.

By using the SEIQoL‐Q, we found that the life domains “family,” “physical health,” “emotional well‐being,” and “home/housing” were most important for patients with incurable cancer. This is in line with observations from other investigators [28, 40, 41]. In contrast, the life domain “work/occupation” was less important for our patients. This might reflect the fact that the average age of our study population was 64.2 years, and the majority of study participants might have already retired or at the end of their professional life, as the normal retirement age in Germany is 65 years. We observed the largest discrepancy between the score for importance and the score for satisfaction for the domains “physical health” and “emotional well‐being.” The patients declared these items as very important, but they were not satisfied with them. This confirms previous study results of Becker et al. [28].

Especially at the time of diagnosis, more patients declared unmet needs than in the further course. Puts et al. [42] described a similar phenomenon in older patients newly diagnosed with cancer. Otherwise, criteria that correlated with unmet needs were younger age, female gender, depression, physical symptoms, marital status, type of treatment, income, and education [42]. Wang et al. [43] showed in their review of 50 studies that patients with advanced cancer reported a broad spectrum of context‐bound unmet needs.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Our study provides prospectively sampled data on symptom burden and palliative care needs of patients with cancer treated in different sectors of the German health care system from the diagnosis of incurability and before any anticancer treatment with palliative intention, followed by 1 year longitudinal follow‐up of palliative cancer care. It comprises a large variety of solid cancer diagnoses among which we collected data from the most common malignant disease groups. We used validated measuring instruments in a homogenous way and at predefined time. The involvement of one of the biggest National Cancer Societies worldwide representing almost 8,000 individual members enables a realistic picture of the oncological care landscape in the country where the study was performed (Germany). Also worth mentioning is the high response rate from enrolled patients. This underlines high investigators’ and patients’ commitment to the study aims and a professional study management.

However, this study has a number of limitations. First, not all tumor entities were recorded. The decision for the selected solid tumors was based on the interests of the different working groups of the German Cancer Society. Because the uro‐oncology and the neuro‐oncology working groups were involved in other competing studies at the time when our study was initiated, these diagnoses are not represented in our study. Second, the case number of 500 patients is not based on a biometrically supported hypothesis but on empirical values regarding feasibility in a 2‐year recruitment phase, to obtain robust descriptive results. Additionally, all eligible patients were recruited consecutively, regardless of the number of patients who had already been enrolled previously. As a consequence, the different tumor entities are not evenly distributed and some groups are too small to allow for robust subgroup analyses with a sufficient statistical power. Third, patients who were critically ill were not recruited for the study. By specifying the inclusion criterion “patient is not in a critical health condition and is not directly threatened by the cancer or complications resulting from it,” a conscious decision was made to exclude them. We still believe that “end‐of life care” is a different scope, and care needs must be addressed in a different way compared with our target cohort. Fourth, it was not systematically recorded which patients did not participate in the study and for which reasons they declined or were not asked by the investigators. For example, not all patients were suitable for such complex self‐report measures. Patients who were not suitable for this type of questionnaires could not participate in the study or needed the support of the study staff. Therefore, we cannot exclude a systematic selection bias. In general, the feasibility of complex questionnaire concepts without personal support for patients with communication and understanding limitations because of their critical disease status should be critically questioned.

Fifth, because of the advanced cancer disease, many study participants with particularly poor prognosis died before the fourth study visit. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the remaining study population was selected for better quality of life and less need for support.

Sixth, because of patients’ death before the fourth study visit, the number of evaluable data for individual tumor entities reached a critical level [44]. Thus, the feasibility of a longitudinal study in the palliative situation has reached the limit of feasibility for some tumor entities.

Conclusion

Patients reported high levels of distress and psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression already at time of diagnosis of incurable cancer disease. We observed a broad spectrum of symptoms and disease burden even at the very beginning of a palliative disease trajectory, with strong variation in intensity both between and within the different tumor entities. At time of diagnosis, more patients have unmet needs than at a later stage. However, patients showed a great variance of supportive care needs over the disease trajectory. In summary, our results confirm that patients need an early individualized offer of multifaceted support, including palliative care services, starting already at the time of diagnosis of incurable cancer. To provide patients with individualized support, structured assessment or regular screening tools to evaluate patient's burden and care needs should be used.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Florian Lordick, Jeannette Vogt, Bernd Alt‐Epping, Anja Mehnert‐Theuerkauf, Birgitt van Oorschot, Michael Thomas

Provision of study material or patients: Jeannette Vogt, Jochen Sistermanns, Jonas Kuon, Christoph Kahl, Susanne Stevens, Miriam Ahlborn, Christian George, Andrea Heider, Maria Tienken, Carmen Loquai, Kerstin Stahlhut, Anne Ruellan, Thomas Kubin, Andreas Dietz, Karin Oechsle, Anja Mehnert‐Theuerkauf, Birgitt van Oorschot, Michael Thomas, Olaf Ortmann, Christoph Engel, Florian Lordick

Collection and/or assembly of data: Jeannette Vogt, Franziska Beyer, Jochen Sistermanns, Jonas Kuon, Christoph Kahl, Bernd Alt‐Epping, Susanne Stevens, Miriam Ahlborn, Christian George, Andrea Heider, Maria Tienken, Carmen Loquai, Kerstin Stahlhut, Anne Ruellan, Thomas Kubin, Andreas Dietz, Karin Oechsle, Anja Mehnert‐Theuerkauf, Birgitt van Oorschot, Michael Thomas, Olaf Ortmann, Christoph Engel, Florian Lordick

Data analysis and interpretation: Jeannette Vogt, Franziska Beyer, Christoph Engel, Florian Lordick

Manuscript writing: Jeannette Vogt, Franziska Beyer, Bernd Alt‐Epping, Anne Ruellan, Anja Mehnert‐Theuerkauf, Florian Lordick

Final approval of manuscript: Jeannette Vogt, Franziska Beyer, Jochen Sistermanns, Jonas Kuon, Christoph Kahl, Bernd Alt‐Epping, Susanne Stevens, Miriam Ahlborn, Christian George, Andrea Heider, Maria Tienken, Carmen Loquai, Kerstin Stahlhut, Anne Ruellan, Thomas Kubin, Andreas Dietz, Karin Oechsle, Anja Mehnert‐Theuerkauf, Birgitt van Oorschot, Michael Thomas, Olaf Ortmann, Christoph Engel, Florian Lordick

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Appendix S1: Supporting information

Appendix S2: Supporting information

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the German Cancer Society (DKG). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Gaertner J, Wolf J, Ostgathe C et al. Specifying WHO recommendation: Moving toward disease‐specific guidelines. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1273–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie, S3‐Leitlinie Palliativmedizin für Patienten mit einer nicht heilbaren Krebserkrankung; AWMF Registriernr.: 128/001‐OL. Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simon ST, Pralong A, Radbruch L et al. The palliative care of patients with incurable cancer. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2020;117:108–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jordan K, Aapro M, Kaasa S et al. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol 2018;29:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li ZG et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bauman JR, Temel JS. The integration of early palliative care with oncology care: The time has come for a new tradition. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 2014;12:1763–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davis MP, Temel JS, Balboni T et al. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann Palliat Med 2015;4:99–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD011129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Oliviera Valentino TC, Paiva CE, Hui D et al. Impact of palliative care on quality of end‐of‐life care among brazilian patients with advanced cancers. J Pain Syst Manage 2020;59:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S et al. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:394–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall'Agata M et al. Systematic versus on‐demand early palliative care: Results from a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 2016;65:61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rugno FC, Paiva BS, Paiva CE. Early integration of palliative care facilitates the discontinuation of anticancer treatment in women with advanced breast or gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol 2014;135:249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Temel JS, Greer JA, El‐Jawahri A et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Conlon MSC, Caswell JM, Santi SA et al. Access to palliative care for cancer patients living in a northern and rural environment in Ontario, Canada: The effects of geographic region and rurality on end‐of‐life care in a population‐based decedent cancer cohort. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2019;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ding JF, Saunders C, Cook A et al. End‐of‐life care in rural general practice: How best to support commitment and meet challenges? BMC PalliatCare 2019;18:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reyes‐Gibby CC, Anderson KO, Shete S et al. Early referral to supportive care specialists for symptom burden in lung cancer patients. Cancer 2012;118:856–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirano H, Shimizu C, Kawachi A et al. Preferences regarding end‐of‐life care among adolescents and young adults with cancer: Results from a comprehensive multicenter survey in Japan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;58:235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li T, Pei X, Chen X et al. Identifying end‐of‐life preferences among chinese patients with cancer using the heart to heart card game. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020:62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mehnert A, Müller D, Lehmann C et al. The German version of the NCCN Distress Thermometer: Validation of a screening instrument for assessment of psychosocial distress in cancer patients [in German]. Z Klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother 2006;54:213–223. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB et al. An ultra‐brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ‐4. Psychosomatics 2009;50:613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M et al. A 4‐item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire‐4 (PHQ‐4) in the general population. J Affect Disord 2010;122:86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G et al. The functional assessment of cancer‐therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: Properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Becker G, Merk CS, Meffert C et al. Measuring individual quality of life in patients receiving radiation therapy: The SEIQoL‐questionnaire. Qual Life Rese 2014;23:2025–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waldron D, O'Boyle CA, Kearney M et al. Quality‐of‐life measurement in advanced cancer: Assessing the individual. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3603–3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lehmann C, Koch U, Mehnert A. Psychometric properties of the German version of the Short‐Form Supportive Care Needs Survey Questionnaire (SCNS‐SF34‐G). Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2415–2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Boer AZ, Derks MGM, de Glas NA et al. Metastatic breast cancer in older patients: A longitudinal assessment of geriatric outcomes. J Geriatr Oncol 2020;11:969–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carduff E, Kendall M, Murray SA. Living and dying with metastatic bowel cancer: Serial in‐depth interviews with patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27:e12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cutillo A, O'Hea E, Person S et al. NCCN Distress Thermometer: Cut off points and clinical utility. Oncol Nurs Forum 2017;44:329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fang F, Fall K, Mittleman MA et al. Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 20125;366:1310–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Waller A, Williams A, Groff SL et al. Screening for distress, the sixth vital sign: Examining self‐referral in people with cancer over a one‐year period. Psychooncology 2013;22:388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barbaret C, Delgado‐Guay MO, Sanchez S et al. Inequalities in financial distress, symptoms, and quality of life among patients with advanced cancer in France and the US. The Oncologist 2019;24:1121–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J et al. General population and cancer patient norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General (FACT‐G). Eval Health Prof 2005;28:192–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pearman T, Yanez B, Peipert J et al. Ambulatory cancer and US general population reference values and cutoff scores for the functional assessment of cancer therapy. Cancer 2014;120:2902–2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lo C, Zimmermann C, Rydall A et al. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal and lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3084–3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stone PC, Murphy RF, Matar HE et al. Measuring the individual quality of life of patients with prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2008;11:390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wettergren L, Lindblad AK, Glimelius B et al. Comparing two versions of the schedule for evaluation of individual quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Acta Oncologica 2011;50:648–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Puts MTE, Papoutsis A, Springall E et al. A systematic review of unmet needs of newly diagnosed older cancer patients undergoing active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:1377–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM et al. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: A systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alt‐Epping B, Seidel W, Vogt J et al. Symptoms and needs of head and neck cancer patients at diagnosis of incurability ‐ Prevalences, clinical implications, and feasibility of a prospective longitudinal multicenter cohort study. Oncol Res Treat 2016;39:186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Appendix S1: Supporting information

Appendix S2: Supporting information