Abstract

Background

In older patients with cancer, depression is difficult to assess because of its heterogeneous clinical expression. The 4‐item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐4) is quick and easy to administer but has not been validated in this population. The present study was designed to test the diagnostic performance of the GDS‐4 in a French cohort of older patients with cancer before treatment.

Materials and Methods

Our cross‐sectional analysis of data from the Elderly Cancer Patient cohort covered all patients with cancer aged ≥70 years and referred for geriatric assessment at two centers in France between 2007 and 2018. The GDS‐4’s psychometric properties were evaluated against three different measures of depression: the geriatrician's clinical diagnosis (based on a semistructured interview), the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and a cluster analysis. The scale's sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) were calculated.

Results

In a sample of 2,293 patients (median age, 81 years; women, 46%), the GDS‐4’s sensitivity and specificity for detecting physician‐diagnosed depression were, respectively, 90% and 89%. The positive and negative likelihood ratios were 8.2 and 0.11, and the AUROC was 92%. When considering the subset of patients with data on all measures of depression, the sensitivity and specificity values were, respectively, ≥90% and ≥72%, the positive and negative likelihood ratios were, respectively, ≥3.4 and ≤ 0.11, and the AUROC was ≥91%.

Conclusion

The GDS‐4 appears to be a clinically relevant, easy‐to‐use tool for routine depression screening in older patients with cancer.

Implications for Practice

Considering the overlap between symptoms of cancer and symptoms of depression, depression is particularly difficult to assess in older geriatric oncology and is associated with poor outcomes; there is a need for a routine psychological screening. Self‐report instruments like the 4‐item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale appears to be a clinically relevant, easy‐to‐use tool for routine depression screening in older patients with cancer. Asking four questions might enable physicians to screen older patients with cancer for depression and then guide them toward further clinical evaluation and appropriate care if required.

Keywords: Depression, Neoplasms, Aged, Diagnosis, Psychiatric status rating scales

Short abstract

Depression is associated with worse outcomes in older patients with cancer. This article evaluates the diagnostic performance of the French Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐4) in a French cohort of elderly patients before treatment for cancer.

Introduction

In Europe, there were an estimated 4.3 million new cases of cancer in 2018, of which 2.5 million (60%) occurred in people aged 65 years and older [1]. Several studies have suggested that depression is associated with poor outcomes in patients with cancer. For example, depression in patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer was associated with poor quality of life, a poor prognosis, and poor treatment adherence [2]. Depression is also reportedly associated with a longer hospital stay for patients with colorectal cancer [3]. Moreover, depression was found to be associated with worse survival in older patients with cancer [4, 5, 6, 7]. The higher mortality rate might be partially explained by a delayed diagnosis, poorer quality of care, and/or poor treatment adherence [8, 9]. Furthermore, depression is frequent in older patients with cancer, and the completed suicide rate is higher in older adults than in young adults [10]. According to a recent meta‐analysis, the pooled prevalence of depression in patients with cancer ranged from 8% to 24% but differed according to the type of instrument, the type of cancer, and the treatment phase [11].

Depression is particularly difficult to diagnose in older patients with cancer [12]. First, the overlap between symptoms of cancer and symptoms of depression leads to diagnostic uncertainty [13]. Second, diagnosis is more problematic in older people in general, for whom depression is more frequently associated with physical symptoms [14]. Older people also might report depressive symptoms differently, compared with younger adults [15]. For these reasons, standard diagnostic criteria might not apply to all clinical situations, especially when some criteria can be attributed to cancer or its treatment (such as sleep disorders, poor appetite, and lack of energy) rather than to depression per se [16, 17, 18].

A geriatric assessment (GA) is a multidimensional process for guiding treatment decisions in older patients with cancer. Potential impairments in several domains are evaluated. The screening of depression is a part of the GA and is recommended by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology [19].

Many tools have been developed for depression screening in various settings. In older patients, several self‐report instruments for measuring depression have been validated; they include the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression scale (CES‐D), and the 15‐item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐15). Other scales have been validated in patients with cancer, including the Brief Symptom Inventory‐18 and the CES‐D [20]. The GDS‐15’s psychometric properties were estimated in a single study with a small number of patients in a palliative care setting, and the mean age was not reported [20, 21]. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has screened for depression specifically in older patients with cancer; it used the GDS‐15, the HADS, and the CES‐D [22]. The HADS consisted of 14 items that assess depression and anxiety symptoms and has been especially selected not to be biased by a comorbid nonpsychiatric condition such as cancer to be reliable in the context of patients hospitalized in a general hospital; the CES‐D with 20 items has been designed to be used in the community and thus included more somatic symptoms of depression (such as fatigue or poor appetite).

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) is widely used [23] among patients with cancer and older adults. The 30‐ and 15‐item versions of the GDS are the most frequently used [24]. Unlike the CES‐D scale or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria, the GDS‐15 focuses on psychological symptoms (e.g., sadness, feelings of hopelessness) less likely to be biased by the symptoms of a comorbid cancer. Given that a comprehensive GA requires the evaluation of several multidisciplinary domains (including depression), its administration is time consuming [19]. Shorter versions of the GDS have therefore been developed for ease and simplicity of administration [25]. A four‐item French version (the GDS‐4) has been developed and validated [26]. In addition of being short, the GDS‐4 consisted of the assessment of four symptoms of depression, without any somatic symptom contributing to help the patrician to specifically screen depression in older patient with cancer in routine clinical practice.

Aims of the Study

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the French GDS‐4 in a population of older subjects with cancer (overall and by tumor site and metastatic status).

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

The Elderly Cancer Patient (ELCAPA) study is a prospective open‐cohort study that includes consecutive inpatients and outpatients aged 70 or older with histologically documented solid or hematological cancers. Before the treatment was decided, patients were referred by an oncologist, radiotherapist, surgeon, or other specialist to the geriatric oncology clinics of 19 university medical centers or cancer centers in the greater Paris urban area of France.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients before inclusion in the ELCAPA cohort, and the study protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee (CPP Ile‐de‐France I, Paris, France; reference: mai 2019‐MS121). The cohort study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT: 02884375).

In the present study, patients were included from January 2007 to February 2018 in two university medical centers: Cochin Hospital (Paris, France) and Mondor Hospital (Créteil, France). The symptoms of depression were systematically and comprehensively analyzed. The present study was a cross‐sectional analysis of the cohort's inclusion data.

Data Collection

At inclusion, data on age, sex, and cancer‐related characteristics (tumor site and metastatic status) were recorded. After a multidisciplinary team meeting, the cancer treatment strategies were also recorded. The multidimensional GA was performed by geriatricians with expertise in oncology. Symptoms of depression were not assessed with standardized questions (as would be the case in a structured interview) but were among the clinical features that physicians had to systematically search for and report in a standardized medical report form, including the four binary items of the French GDS‐4 (Table 1) and other symptoms corresponding to the DSM‐IV criteria for a major depressive episode (see below). Data were abstracted by an independent research assistant. This multidimensional GA also included an evaluation of general health status, comorbidities (according to the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics [CIRS‐G]), functional status (Activities of Daily Living [ADL]), nutritional status (weight loss, defined as the loss of ≥5% of bodyweight in the previous month or ≥ 10% of body weight in the previous 6 months, body mass index [BMI], and the Mini Nutritional Assessment [MNA] score), cognitive status (the Mini‐Mental State Examination [MMSE] score), and psychological and social variables (the primary caregiver, support at home, and the presence or absence of a circle of family and friends). Medication use (including the number and classes of antidepressant) were recorded.

Table 1.

The French GDS‐4

| No. of item | Item |

|---|---|

| 1 | Do you often feel discouraged and sad? (no/yes, 0/1) |

| 2 | Do you feel that your life is empty? (no/yes, 0/1) |

| 3 | Do you feel happy most of the time? (yes/no, 0/1) |

| 4 | Do you feel that your situation is desperate? (no/yes, 0/1) |

Abbreviation: GDS‐4, four‐item Geriatric Depression Scale.

Endpoint

The endpoint was the presence of clinical depression at the time of the GA. In view of the complexity and heterogeneity of depressive symptoms in older patients with cancer [14], depression is difficult to diagnose. We therefore defined three different measures of depression to examine the robustness of the GDS‐4’s estimated diagnostic performance.

First, we considered the diagnosis of clinical depression made by the physician at the end of the GA. This was a pragmatic measure in a real‐life setting; the physician judged the plausibility of attributing each depressive symptom to depression rather than to cancer or cancer treatment.

Second, we considered eight of the nine DSM‐IV criteria for a major depressive episode: the two criteria that patient must have were either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure, and the six other criteria were significant weight or appetite changes, sleep disturbances, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, a feeling of worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Cognitive complaints were not considered as being specific enough to flag up depression in our sample of older participants with cancer. Major depression was defined as the presence of at least five criteria, with at least depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure (supplemental online Fig. 1).

The third measure was based on a latent class analysis (LCA), a method that can be used to identify homogeneous classes of patients. Our team has developed an LCA for identifying depressed older patients with cancer [4]. The LCA's indicators include psychological symptoms like sadness (self‐reported or assessed by a clinician), anhedonia (feeling empty or blunted positive affect), negative thoughts (feelings of worthlessness or hopelessness), and anxiety. The LCA also include somatic symptoms such as insomnia, fatigue, decreased appetite, pain complaints, and gastrointestinal symptoms. In the present study, five classes of depressive symptoms were identified: “somatic only,” “paucisymptomatic,” “severe depression,” “mild depression,” and “demoralization” [4]. We considered that “severe depression” was the third measure of depression.

In the DSM‐IV–based and LCA‐based definitions of severe depression, missing data on depressive symptoms reduced the sample size. Accordingly, to ensure consistent results, we repeated the primary analysis (using the diagnosis of clinical depression made by the physician) in the subset of participants with full data.

Tests

The French GDS‐4 comprises four items with binary answers (“yes” or “no;” Table 1) and has been validated [26]. In line with the literature, depression was defined as a score of 1 or more out of 4 [26].

Statistical Analysis

Study results were reported according to the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies [27].

Categorical variables were expressed as the frequency (percentage), and quantitative variables were expressed as the mean ± SD or the median (interquartile range [IQR]). We estimated the frequency of depression according to each of the three endpoints, together with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

For each of the three measures, we estimated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode. The geriatrician's clinical diagnosis was evaluated in the entire sample, and the two other measures were evaluated in the subsets with data. Positive and negative likelihood ratios were also calculated, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUROC) was estimated. The 95% CI was calculated for each measure. Furthermore, we conducted the same analyses by tumor site and metastatic status.

For the geriatrician's clinical diagnosis at the end of the GA, we assessed factors associated with false positive (FP) and true negative (TN) results by comparing the two corresponding populations to identify patients being wrongly screened as depressed. We used the same strategy to search for factors associated with false negative (FN) and true positive (TP) results to identify profile of patients who were missed by GDS‐4 screening. Hence, we first conducted a univariate analysis. Variables that were statistically significant (p < .20) in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate model.

The threshold for statistical significance was set to p < .05, and all tests were two‐tailed. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata software (version 15.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX) and RStudio software (version 1.0.136 and the pROC package, RStudio, Inc.; RStudio Team (2018). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/).

Results

Diagnostic Performance of the GDS‐4 in the Overall Population

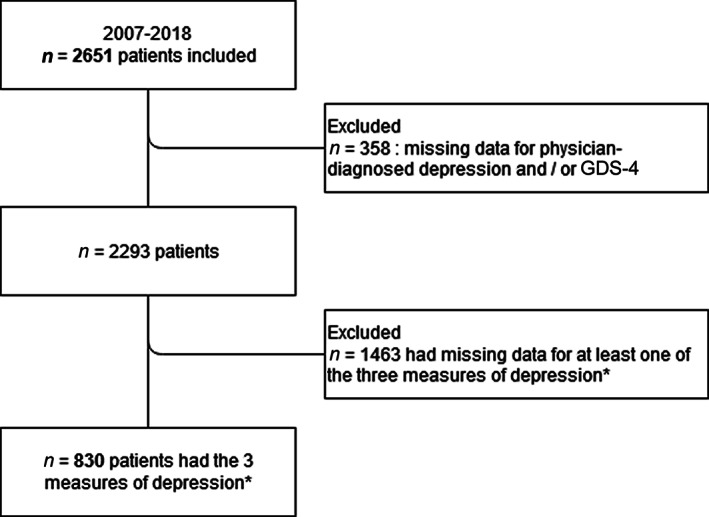

A total of 2,651 patients were included, of whom 358 had missing data for the clinical evaluation of depression by the physician and/or the GDS‐4 (Fig. 1). Among the remaining 2,293 patients, the median (IQR) age was 81.2 years (77.2 – 85.4), 45.8% were women, 30.2% were inpatients, 94.6% had a solid tumor, and 51.3% had metastatic cancer. According to the geriatrician's clinical diagnosis, the prevalence of depression was 29%. The characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Patient flow‐chart. *Physician‐diagnosed depression, major depressive episode according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders‐IV and latent class “severe depression.”

Abbreviations: GDS‐4, four‐item Geriatric Depression Scale.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics (n = 2,293)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| >80 | 1,330 (58.00) |

| Median (IQR) | 81.17 (77.20–85.35) |

| Female sex | 1,049 (45.75) |

| Inpatient status | 692 (30.18) |

| Living alone at home (n = 2,289) | 868 (37.92) |

| Inadequate social support (n = 970) | 213 (21.96) |

| Cancer site | |

| Colorectal | 409 (17.84) |

| Upper digestive tract, stomach, pancreas | 398 (17.36) |

| Breast | 330 (14.39) |

| Prostate | 284 (12.39) |

| Urinary tract | 365 (15.92) |

| Other (lung, gynecological, face, skin, etc.) | 384 (16.75) |

| Hematological malignancies | 123 (5.36) |

| Metastasis (n = 1,954) | |

| M0 | 890 (45.55) |

| M1 | 1,002 (51.28) |

| Mx | 62 (3.17) |

| Depression | |

| History of physician‐diagnosed depression (n = 965) | 135 (13.99) |

| Ongoing treatment with an antidepressant medication (n = 954) | 140 (14.68) |

| Number of other daily medications (n = 931) | |

| ≥5 | 632 (67.88) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (4–8) |

| Geriatric assessment: GDS‐4 ≥1 | 776 (33.84) |

| ADL score (n = 2,290) | |

| <5.5 | 672 (29.34) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5–6) |

| iADL score (n = 2,171) | |

| <8 | 1,412 (65.04) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (3–8) |

| Total CIRS‐G score (n = 2,159), median (IQR) | 13 (9–17) |

| History of falls in the previous 6 months (n = 2,256) | 688 (30.50) |

| BMI (n = 2,242), kg/m2 | |

| <21 | 389 (17.35) |

| Median (IQR) | 24.7 (21.9–27.9) |

| Weight loss a (n = 797) | 186 (23.34) |

| MNA score (n = 2,209) | |

| <17 | 398 (18.02) |

| Median (IQR) | 22.5 (18.5–25.5) |

| MMSE score (n = 1,991) | |

| <24 | 502 (25.21) |

| Median (IQR) | 27 (23–29) |

| ECOG‐PS (n = 2,290) | |

| 0–1 | 1,129 (49.30) |

| 2 | 486 (21.22) |

| 3–4 | 675 (29.48) |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) |

Weight loss was defined as the loss of ≥5% of bodyweight in the previous month or ≥ 10% of bodyweight in the previous 6 months.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CIRS‐G, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics; ECOG‐PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; iADL, instrumental ADL; IQR, interquartile range; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment.

We evaluated the diagnostic performance of the GDS‐4 in the population of 2,293 patients. The sensitivity and specificity were, respectively, 90% (95%CI, 87.5%–92.2%) and 89% (87.4%–90.5%), the positive and negative likelihood ratios were, respectively, 8.2 (7.12–9.44) and 0.11 (0.09–0.14), and the AUROC was 91.9% (90.6%–93.2%).

Diagnostic Performance of the GDS‐4 in the Populations with Full Data on the Clinical, DSM‐IV‐Based and LCA Assessments

Data on the clinical, DSM‐IV‐based, and LCA‐based measures of depression was available for 830 patients (Fig. 1). The median (IQR) age was 80.3 years (76.6–84.7), 48% of the patients were women, 36% were inpatients, 90.8% had a solid tumor, and 49.8% had metastatic cancer. When compared with the excluded study population, these latter were significantly older (median age [IQR], 81.8 years [77.5–85.9]; p < .001), less inpatients (30.1%; p = .003), and more likely to be taking antidepressant medication (respectively, 24.8% and 13.8% in the subset of 830 patients; p < .001) and to have lost weight (respectively, 34.0% and 22.3% in the included population; p = .003).

The frequency of depression varied according to the measure of depression: 25% for the physician's evaluation, 5.1% according to the available DSM‐IV criteria, and 20% for the “severe depression” class in the LCA.

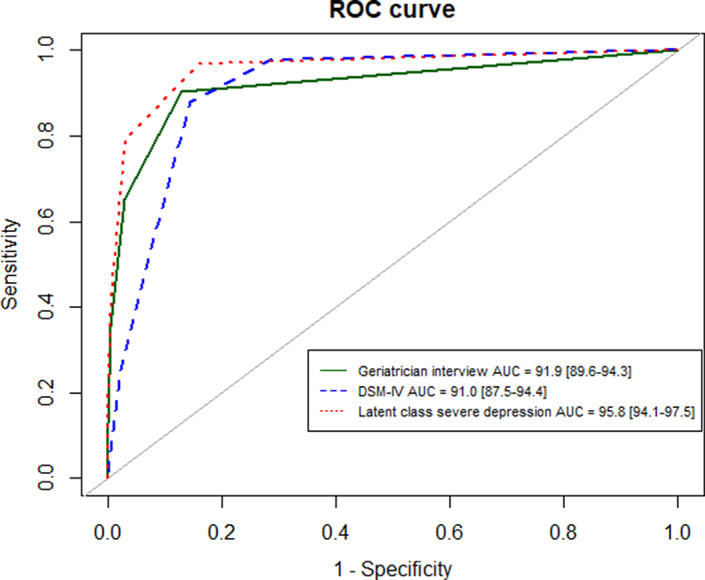

The GDS‐4’s diagnostic performance according to each measure of depression is summarized in Table 3. The AUROC was 91.9% (95%CI, 89.6%–94.3%) for clinical depression, 91.0% (87.5%–94.4%) for a major depressive episode according to the DSM‐IV, and 95.8% (94.1%–97.5%) for the “severe depression” class in the LCA. The ROC curves are shown in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Diagnostic performance of the GDS‐4, according to the three measures of depression (n = 830)

| Measure | Clinical depression | Major depressive episode according to the DSM‐IV | Latent class “severe depression” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression prevalence, %, (95%CI) | 25 (22–27.7) | 5.1 (3.7–6.8) | 20 (17.0–22.6) |

| Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | 90.2 (85.3–93.9) | 97.6 (87.4–99.9) | 97 (93–99.0) |

| Specificity,% (95% CI) | 87.1 (84.2–89.6) | 71.6 (68.3–74.7) | 84.1 (81.1–86.8) |

| PPV,% (95% CI) | 69.4 (63.5–74.9) | 15.5 (11.3–20.4) | 60 (53.8–65.9) |

| NPV, % (95% CI) | 96.5 (94 .6–97.8) | 99.8 (99.0–100.0) | 99.1 (97.9–99.7) |

| LR+,% (95% CI) | 6.97 (5.66–8.58) | 3.43 (3.04–3.87) | 6.09 (5.11–7.27) |

| LR−,% (95% CI) | 0.11 (0.07–0.17) | 0.03 (0.00–0.23) | 0.04 (0.02–0.09) |

| AUROC, (95% CI) | 91.93 (89.57–94.29) | 90.96 (87.51–94.41) | 95.79 (94.1–97.47) |

Abbreviations: AUROC, area under the ROC curve; GDS‐4, four‐item Geriatric Depression Scale; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR−, negative likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Figure 2.

ROC curves of the four‐item Geriatric Depression Scale according to the three measures of depression (n = 830)

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the ROC curve; DSM‐IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th version; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

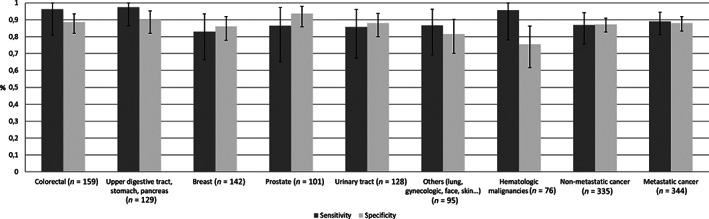

Figure 3 shows the French GDS‐4’s sensitivity and specificity as a function of the tumor site (colorectal, upper digestive tract, stomach and pancreas, breast, prostate, urinary tract, other cancers, and hematologic malignancies) and metastatic status. For clinical depression, the sensitivity was at least 83% and the specificity was at least 76%. For metastatic cancer, the sensitivity was 89.0% (81.2%–94.4%) and the specificity was 88.1% (83.4%–91.9%). Last, for nonmetastatic cancer, the sensitivity was 86.9% (75.8%–94.2%) and the specificity was 87.2% (82.7%–90.9%).

Figure 3.

Histogram showing sensitivity and specificity for the four‐item Geriatric Depression Scale considering a depressive episode based on geriatrician interview, according to type of cancer and metastatic status (n = 830).

The comparison of characteristics between TN patients (patients with a negative GDS‐4 result and no depression) and FP patients (patient with a positive GDS‐4 result and no depression) is shown in supplemental online Table 1. Relative to TN patients, FP patients had significantly worse scores on dependency scales (ADL and instrumental ADL [iADL]) and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG‐PS) and a greater prevalence of falls in the previous 6 months, malnutrition (MNA score < 17), inpatient status, and living alone at home. There was no significant differences between the TN and FP groups in terms of age, sex, adequacy of social support, cancer site, history of physician‐diagnosed depression, BMI, and the MMSE score. Because some variables were correlated (ADL, iADL, and ECOG‐PS scores and living alone at home), we created a composite variable from on the two variables that we considered to be the most relevant (iADL score and living alone at home). In the multivariate analysis, a CIRS‐G score > 12 was independently associated with FP status (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.54 [95% CI, 1.11–2.14], p = .009). Considering the composite variable, not living alone with an iADL score < 8 (aOR, 2.21 [95% CI, 1.29–3.80]) and living alone at home regardless of the iADL score (aOR, 2.74 [95% CI, 1.61–4.69]) were also independently associated with FP status (p = .001). Because a very small sample size of FN (n = 66) patients in our study, the comparison between FN and TP was not performed.

Discussion

The GDS‐4 performed well for the detection of depression in older patients with cancer. For the three different measures of depression, the sensitivity was at least 90.2% and the specificity was at least 71.6%. The positive and negative likelihood ratios were 3.4 or more and 0.11 or less, respectively, and the AUROC was 91% or more.

These values are better than those described in a recent systematic review and meta‐analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of the short‐forms GDSs in a population aged 55 or older [28]. Two studies [25, 29] found sensitivity values between 85% and 93% and specificity values between 53% to 63% in older patients without cancer. Van Marwijk and colleagues (1995) reported on a different GDS‐4 (i.e., featuring 4 of the 15 GDS items but not exactly the same ones as studied here) [30]. In a sample of 586 patients studied in nine general practices in The Netherlands, the GDS‐4’s sensitivity and specificity were 61% and 72%, respectively.

These differences should be interpreted with regard to the items included in the French GDS‐4, only two of which are also present in the English GDS‐4 (“Do you feel that your life is empty?” and “Do you feel happy most of the time?”). A recent study assessed depression in 201 older patients with breast and prostate cancer [22]. The investigators evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of three self‐report instruments (the GDS‐15, the HADS, and the CES‐D) and used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV‐TR (fourth edition, text revision) as the diagnostic reference for depression. Using the published cutoff score of 5 for the GDS‐15, the sensitivity was 67% and the specificity was 88%. With a cutoff of 4 (the best cutoff according to a ROC curve analysis and Youden's index), the sensitivity was 83% and the specificity was 78%. The sensitivity and specificity were respectively 67% and 85% for the HADS‐D and 83% and 89% for the CESD‐R. In cancer care, it is now recommended to screen for distress in routine, and tools such as the Distress Thermometer have been developed, which consisted of a single item with a 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress)‐point Likert scale [31]. Despite being short and easy to use in routine, the Distress Thermometer only evaluated global distress, which is frequently explained by anxiety, without exploring specific aspects of depression such as like sadness or feeling of an empty life. The GDS‐4, in addition to be a brief scale, is less likely to be confounded by anxiety and may better capture depressive symptoms that are specifically associated with suicide risk such as hopelessness.

Independent factors associated with FP status were living alone at home (regardless of the iADL score), not living alone at home but with iADL score < 8, and a CIRS‐G score > 12. According to a qualitative study on differences between nondepression [32], subsyndromal depression, and depression in older people (based on the GDS‐15), it appeared that a decline in bodily functions was considered to be a normal part of the aging process. However, this decline can also be a consequence of diseases like cancer. It is important to identify the profile of patients who may be wrongly screened as depressed to avoid inappropriate treatment.

Screening for depression is important not only because depression is common and consequential, but also because it is treatable. Although evidence regarding the effectiveness of antidepressants in older patients with cancer is weak [33], Sharpe et al. highlighted the effectiveness of a collaborative and multicomponent treatment program for major depression in cancer patients [34]. The present study had several strengths. First, we used three measures of depression (based on different methods) to evaluate the GDS‐4’s diagnostic performance; the concordance between the three sets of results highlighted the study's robustness. One of the three methods was an LCA, which can be used to assess diagnostic performance in the absence of a “gold standard” [35]. Considering the measure of depression based on LCA, a latent class (labeled as “no depression/somatic only”) was defined by a high probability of somatic symptoms of depression and a low probability of psychological symptoms of depression, and only the latent class “severe depression” was considered as indicating the presence of depression, thus optimizing the specificity of the diagnosis [4]. Similar results were found whatever the measure considered. We also showed that prevalence differed across theses three measures, reinforcing the hypothesis that it is difficult to diagnose depression with certainty, especially in older patients with cancer. Second, the present study is (to the best of our knowledge) the first to have evaluated the diagnostic performance of a short self‐report instrument in the screening of depression in older patients with cancer. Last, the study population comprised 830 patients; this is more than in the majority of diagnostic studies evaluating short‐form GDSs [28] and therefore provides more precise estimations [36].

The study also had some limitations. The senior geriatricians were not blinded to the results of the GDS‐4 when they performed the semi‐structured interview. This might have led to incorporation bias and the overestimated of both sensitivity and specificity [37]. Furthermore, the lack of a gold standard meant that the frequency of depression varied according to the measure used. The differences in the prevalence of depression across the three measures used in the present study were expected, especially the lower rate obtained with the DSM‐IV criteria. To be considered as a DSM criteria, a symptom should not be better explained by a comorbid condition, such as cancer. Physician may have not considered fatigue or loss of appetite, resulting in a more specific but less sensitive diagnosis. In addition, a minimal number of symptoms is required, including at depressed mood and or loss of interest or pleasure. In contrast, the LCA was not based on a minimal number of symptoms and even considered symptoms that are frequent in older patients with depression but not used as diagnostic criteria in the DSM (i.e., pain complaints and gastrointestinal symptoms). The intermediary rate observed with the clinician assessment could be explained by the fact that clinicians did exclude symptoms likely to be explained by cancer but did not rely on a minimal amount of symptoms to make a diagnosis, with greater emphasis on the most specific ones, such as negative thoughts. Moreover, the excluded population and the included population differed in several respects, which suggests the potential presence of selection bias. Last, cultural differences as well as the fact that the French GDS‐4 and the English GDS‐4 only share two items out of four may limit the generalizability of our results. Regarding cultural differences, they may partially account for the relatively higher prevalence of depression among older individuals in France than in other high‐income countries [38]. For instance, it has been shown that the level of self‐reported happiness is lower in French than other European citizens, whereas this is not the case of immigrants in France. Moreover, native French people tend to report lower levels of happiness than other expatriates in Europe [39]. However, we are not aware of cultural and mental attitudes that would be unique to French people could qualitatively affect the way they experience and report depressive symptoms. Indeed, the differences between the items included in the French GDS‐4 and the English GDS‐4 are more likely to result from differences in the methodology used to develop these two instruments. Specifically, in the process of selecting the best four items, the external validity of the French GDS‐4, as well as its sensitivity and specificity, were assessed against an abridged form of a French self‐report inventory on depressive symptomatology, the QD2A [40], which is not available in English [26].

Conclusion

The French GDS‐4 appeared to be a relevant, quick‐to‐administer tool. Despite some differences between the English and French GDS‐4 scales, the selected items appear to adequately capture certain psychological symptoms of depression (e.g., anhedonia). There is a need for a routine psychological screening in geriatric oncology. Given that a lack of time may prevent a rigorous diagnostic assessment of depression, self‐report instruments like the GDS‐4 might be useful, quick‐to‐administer screens for depression. Asking 4 questions (rather than 15 or 30) might enable physicians to screen more people for depression and then guide them toward further clinical evaluation if required. Patients with a positive screening test can be referred to a psychiatrist in order to confirm the diagnosis and consider appropriate care.

The present results indicate that the French GDS‐4 is a relevant tool for screening for depression in older patients with cancer.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Florence Canoui‐Poitrine, Charlotte Lafont, Anne Chah Wakilian, Cédric Lemogne, Pascaline Boudou‐Rouquette

Provision of study material or patients: Anne Chah Wakilian, Virginie Fossey‐Diaz, Galdric Orvoen, Nathalie Lhuillier, Elena Paillaud, Sylvie Bastuji‐Garin, Olivier Hanon, François Goldwasser, Pascaline Boudou‐Rouquette, Florence Canoui‐Poitrine

Collection and/or assembly of data: Anne Chah Wakilian, Virginie Fossey‐Diaz, Galdric Orvoen, Nathalie Lhuillier, Elena Paillaud, Sylvie Bastuji‐Garin, Olivier Hanon, François Goldwasser, Pascaline Boudou‐Rouquette, Florence Canoui‐Poitrine

Data analysis and interpretation: Charlotte Lafont, Florence Canoui‐Poitrine, Anne Chah Wakilian, Cédric Lemogne, Clément Gouraud, Sonia Zebachi, Pascaline Boudou‐Rouquette

Manuscript writing: Charlotte Lafont, Florence Canoui‐Poitrine, Anne Chah Wakilian, Cédric Lemogne, Clément Gouraud, Pascaline Boudou‐Rouquette

Final approval of manuscript: Charlotte Lafonta, Anne Chah Wakilian, Cédric Lemogne, Clément Gouraud, Virginie Fossey‐Diaz, Galdric Orvoen, Nathalie Lhuillier, Elena Paillaud, Sylvie Bastuji‐Garin, Sonia Zebachi, Olivier Hanon, François Goldwasser, Pascaline Boudou‐Rouquette, Florence Canoui‐Poitrine

Disclosures

Cédric Lemogne: Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen‐Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka Pharmaceutical (C/A [Outside the submitted work]); Pascaline Boudou‐Rouquette: Takeda (C/A), Takeda, Pharmamar (travel expenses). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Figure S1 Depression algorithm according to the DSM‐4

Table S2 Comparison of the characteristics of the true‐negative and the false‐positive groups

Acknowledgments

The ELCAPA Study Group comprises geriatricians (Amelie Aregui, Mickaël Bringuier, Philippe Caillet, Pascale Codis, Tristan Cudennec, Anne Chahwakilian, Amina Djender, Virginie Fossey‐Diaz, Mathilde Gisselbrecht, Marie Laurent, Josephine Massias, Galdric Orvoen, Johanne Poisson, Frédéric Pamoukdjian, Anne‐Laure Scain, Godelieve Rochette de Lempdes, Florence Rollot‐Trad, Hélène Vincent, and Elena Paillaud), oncologists (Pascaline Boudou‐Rouquette, Stéphane Culine, Etienne Brain, and Christophe Tournigand), a digestive oncologist (Thomas Aparicio), a gynecological oncologist (Cyril Touboul), a radiation oncologist (Jean‐Léon Lagrange), epidemiologists (Etienne Audureau, Sylvie Bastuji‐Garin and Florence Canoui‐Poitrine), a medical biologist (Marie‐Anne Loriot), a pharmacist (Pierre‐André Natella), a biostatistician (Claudia Martinez‐Tapia), a clinical research physician (Nicoleta Reinald), a clinical research nurse (Sandrine Rello), a data manager (Clélia Chambraud), and clinical research assistants (Aurélie Baudin, Margot Bobin, and Laure Morisset).

The ELCAPA study was funded by the French National Cancer Institute (Institut National du Cancer, INCa), Canceropôle Ile‐de‐France, Gerontopôle Ile‐de‐France (Gerond'If), and the Curie Institute, none of which had any role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Cancer today . Global Cancer Observatory. Available at http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. Accessed June 23, 2019.

- 2. Arrieta O, P Angulo L, Núñez‐Valencia C et al. Association of depression and anxiety on quality of life, treatment adherence, and prognosis in patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;20:1941–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balentine CJ, Hermosillo‐Rodriguez J, Robinson CN et al. Depression is associated with prolonged and complicated recovery following colorectal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15:1712–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gouraud C, Paillaud E, Martinez‐Tapia C et al. Depressive symptom profiles and survival in older patients with cancer: Latent class analysis of the ELCAPA cohort study. The Oncologist 2018;24:e458–e466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mols F, Husson O, Roukema JA et al. Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for all‐cause mortality: Results from a prospective population‐based study among 3,080 cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. J Cancer Surviv 2013;7:484–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: A meta‐analysis. Psychol Med 2010;40:1797–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: A meta‐analysis. Cancer 2009;115:5349–5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boyd CA, Benarroch‐Gampel J, Sheffield KM et al. The effect of depression on stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surgery 2012;152:403–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mausbach B, B Schwab R, Irwin S. Depression as a predictor of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) in women with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;152:239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Erlangsen A, Stenager E, Conwell Y. Physical diseases as predictors of suicide in older adults: A nationwide, register‐based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:1427–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krebber AMH, Buffart LM, Kleijn G et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: A meta‐analysis of diagnostic interviews and self‐report instruments. Psychooncology 2014;23:121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weinberger MI, Roth AJ, Nelson CJ. Untangling the complexities of depression diagnosis in older cancer patients. The Oncologist 2009;14:60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2004:57–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hegeman JM, Kok RM, van der Mast RC et al. Phenomenology of depression in older compared with younger adults: Meta‐analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gallo JJ, Anthony JC, Muthén BO. Age differences in the symptoms of depression: A latent trait analysis. J Gerontol 1994;49:P251–P264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mir O, Salvador A, Dauchy S et al. Everolimus induced mood changes in breast cancer patients: A case‐control study. Invest New Drugs 2018;36:503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wochna Loerzel V. Symptom experience in older adults undergoing treatment for cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2015;42:E269–E278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen‐Cole SA, Stoudemire A. Major depression and physical illness. Special considerations in diagnosis and biologic treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1987;10:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2595–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nelson CJ, Cho C, Berk AR et al. Are gold standard depression measures appropriate for use in geriatric cancer patients? A systematic evaluation of self‐report depression instruments used with geriatric, cancer, and geriatric cancer samples. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crawford GB, Robinson JA. The geriatric depression scale in palliative care. Palliat Support Care 2008;6:213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saracino RM, Weinberger MI, Roth AJ et al. Assessing depression in a geriatric cancer population. Psychooncology 2017;26:1484–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chiesi F, Primi C, Pigliautile M et al. Is the 15‐item Geriatric Depression Scale a fair screening tool? A differential item functioning analysis across gender and age. Psychol Rep 2018;121:1167–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Clin Gerontol 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 25. D'Ath P, Katona P, Mullan E et al. Screening, detection and management of depression in elderly primary care attenders. I: The acceptability and performance of the 15 item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15) and the development of short versions. Fam Pract 1994;11:260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clément JP, Nassif RF, Léger JM et al. Development and contribution to the validation of a brief French version of the Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale [in French]. Encephale 1997;23:91–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Altman DG et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pocklington C, Gilbody S, Manea L et al. The diagnostic accuracy of brief versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;31:837–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Allgaier A‐K, Kramer D, Saravo B et al. Beside the Geriatric Depression Scale: The WHO‐Five Well‐being Index as a valid screening tool for depression in nursing homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;28:1197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van Marwijk HW, Wallace P, de Bock GH et al. Evaluation of the feasibility, reliability and diagnostic value of shortened versions of the geriatric depression scale. Br J Gen Pract 1995;45:195–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ownby KK. Use of the Distress Thermometer in clinical practice. J Adv Pract Oncol 2019;10:175–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ludvigsson M, Milberg A, Marcusson J et al. Normal aging or depression? A qualitative study on the differences between subsyndromal depression and depression in very old people. Gerontologist 2015;55:760–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ostuzzi G, Matcham F, Dauchy S et al. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;4:CD011006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sharpe M, Walker J, Holm Hansen C et al. Integrated collaborative care for comorbid major depression in patients with cancer (SMaRT Oncology‐2): A multicentre randomised controlled effectiveness trial. Lancet 2014;384:1099–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fernandes FF, Perazzo H, Andrade LE et al. Latent class analysis of noninvasive methods and liver biopsy in chronic hepatitis C: An approach without a gold standard. Biomed Res Int 2017;2017:8252980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mélot C. Qu'est‐ce qu'un intervalle de confiance ? [What is a confidence interval?]. Rev Mal Respir. 2003;20(4):599‐601. French. PMID: 14528162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kohn MA, Carpenter CR, Newman TB. Understanding the direction of bias in studies of diagnostic test accuracy. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:1194–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Richardson RA, Keyes KM, Medina JT et al. Sociodemographic inequalities in depression among older adults: Cross‐sectional evidence from 18 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:673–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Senik C. The French unhappiness puzzle: The cultural dimension of happiness. J Econ Behav Organ 2011;106:379–401. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pichot P. A self‐report inventory on depressive symptomatology (QD2) and its abridged form (QD2A). In: Sartorius N, Ban TA, eds. Assessment of Depression. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 1986: 108–122. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Figure S1 Depression algorithm according to the DSM‐4

Table S2 Comparison of the characteristics of the true‐negative and the false‐positive groups