Abstract

Most eukaryotes harbor two distinct pre-mRNA splicing machineries: the major spliceosome, which removes >99% of introns, and the minor spliceosome, which removes rare, evolutionarily conserved introns1–4. Although hypothesized to serve important regulatory functions5, physiologic roles for the minor spliceosome are not well understood. For example, the minor spliceosome component ZRSR2 is subject to recurrent, leukemia-associated mutations6–9, yet functional connections between minor introns, hematopoiesis, and cancers are unclear. Here, we identify that impaired minor intron excision via ZRSR2 loss enhances hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. CRISPR screens mimicking nonsense-mediated decay of minor intron-containing mRNAs converged on LZTR1, a regulator of Ras-related GTPases10–12. LZTR1 minor intron retention was also discovered in the RASopathy Noonan syndrome, due to intronic mutations disrupting splicing, and diverse solid tumors. These data uncover minor intron recognition as a regulator of hematopoiesis, noncoding mutations within minor introns as potential cancer drivers, and links between ZRSR2 mutations, LZTR1 regulation, and leukemias.

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are clonal blood disorders characterized by impaired hematopoiesis, risk of transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and a paucity of effective treatments. More than 50% of patients with MDS carry a mutation affecting an RNA splicing factor.6–8. Additionally, splicing factor mutations are common to all forms of myeloid malignancies, including AML and myeloproliferative neoplasms. Splicing factor mutations in leukemia are concentrated in four genes (SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2). SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1 are subject to heterozygous, change-of-function13–15 missense mutations affecting specific residues6–8. In contrast, the X chromosome-encoded ZRSR2 is enriched in nonsense and frameshift mutations in male patients, consistent with loss of function6–8. For example, across 2,302 sequentially sequenced myeloid neoplasm patients, 100% of myeloid neoplasm patients (40/40) with somatic mutations in ZRSR2 were male, and there were no females with ZRSR2 mutations (p<0.00001, Fisher’s exact test; Extended Data Fig. 1a–b). In contrast, 57% of ZRSR2 wild-type patients with myeloid neoplasms were male (1,285/2,262 total patients). Moreover, ZRSR2 (also known as U2AF35-related protein (Urp)) is the only protein of the four frequently mutated splicing factors that primarily functions in the minor spliceosome9,16. While most introns are spliced by the major spliceosome (“U2-type introns”), a small subset (<1%) of introns have distinct splice sites and branchpoints that are recognized by a separate ribonucleoprotein complex, the minor spliceosome1,2. Although minor (“U12-type”) introns are present in only 700-800 genes in humans, their sequences and positions are highly evolutionarily conserved – more so than their U2-type counterparts5.

The unusually high conservation of minor introns across eukaryotes suggests that they play key regulatory roles5. In some cases, molecular roles have been elucidated. For example, minor introns are less efficiently excised from pre-mRNA than are major introns. It has therefore been postulated that minor introns serve as “molecular switches” to regulate the expression of their host genes, wherein the rate of removal of a single minor intron within a gene regulates expression of the entire host mRNA17,18. However, relatively few specific functional roles have been elucidated for the minor spliceosome in regulating biological phenotypes.

RESULTS

Zrsr2 loss promotes hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal

Given the recurrent nature of ZRSR2 mutations in leukemias, we hypothesized that minor intron splicing might be particularly important in the hematopoietic system. The relative rarity and exquisite conservation of minor introns offered a unique opportunity to simultaneously investigate splicing factor mutations in malignant hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) disorders as well as identify potential tissue-specific roles of the minor spliceosome. We therefore set out to understand the role of loss-of-function mutations in ZRSR2 as seen in myeloid HSC disorders by generating a mouse model permitting time- and tissue-specific deletion of Zrsr2 (Extended Data Fig. 1c–d; also encoded on the X chromosome in mice). Conditional Cre-mediated excision of exon 4 of Zrsr2, in a manner which results in an early frameshift, efficiently downregulated Zrsr2 mRNA in long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs; lineage-negative CD150+ CD48− c-Kit+ Sca1+ cells) and protein in spleen (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1e–h). This was accomplished by the generation of Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/fl mice, as Mx1-cre is a well-established system allowing for conditional, time-controlled, and efficient deletion of genes in post-natal hematopoietic cells19–21. Exon 4 was chosen for deletion because deletion of this exon causes a frameshift when skipped and this exon is present in all annotated Zrsr2 isoforms and highly conserved across species.

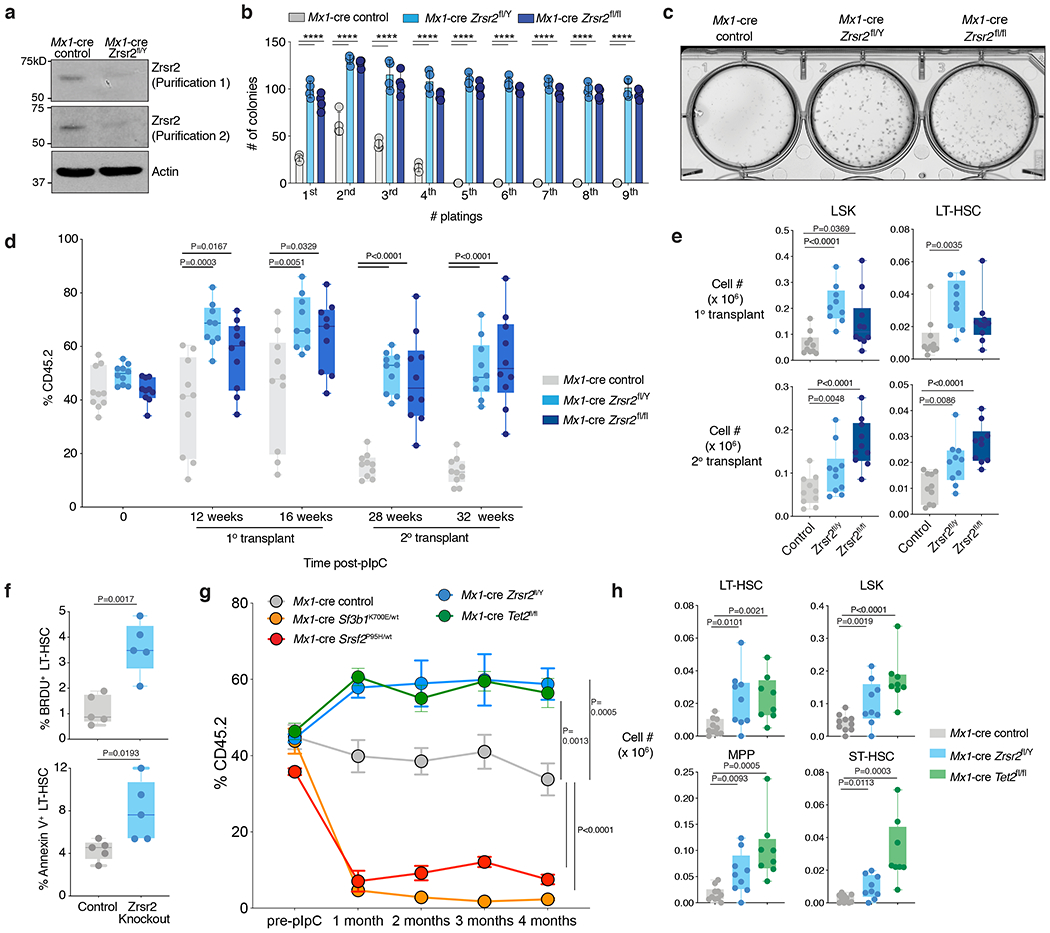

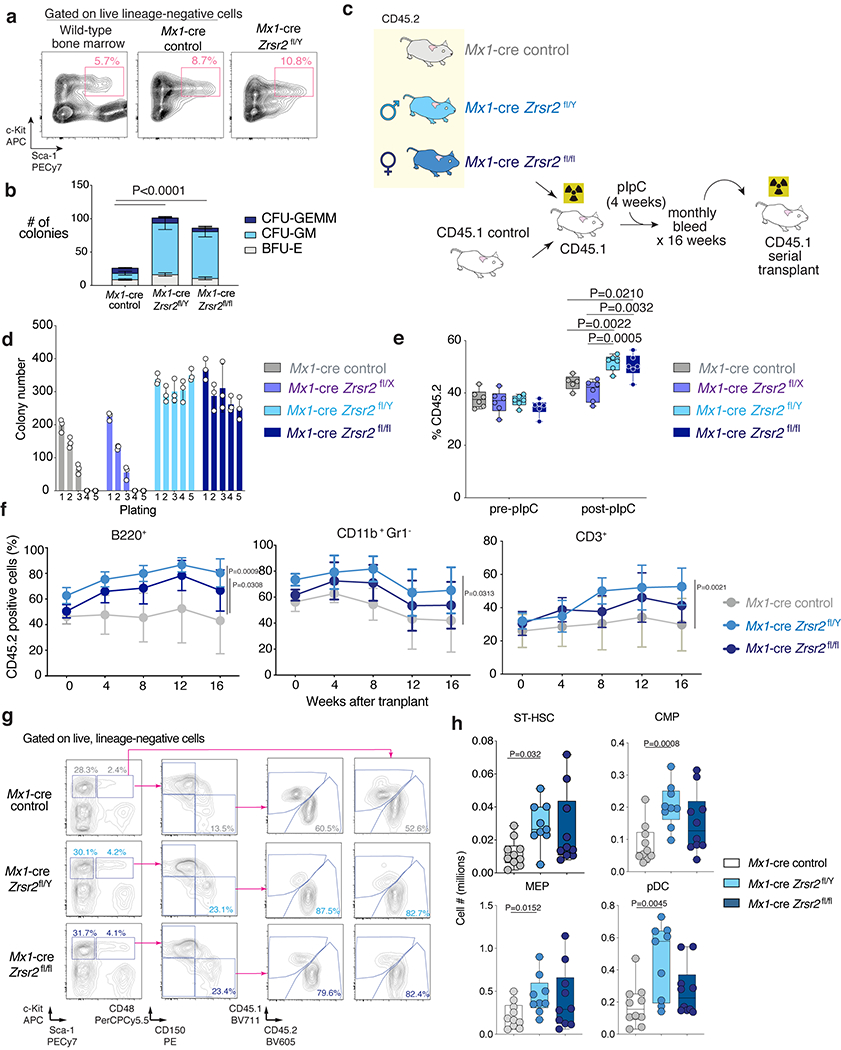

Figure 1. Zrsr2 loss increases hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal.

(a) Anti-Zrsr2 Western blot in the spleens of 6-week-old Mx1-cre control and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/Y mice. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (b) Number of colonies in methylcellulose CFU assays from LT-HSCs from male and female Zrsr2 knockout (KO) mice and controls. Mean value ± SD shown. n=4 biologically independent experiments. P values were calculated by two-sided t-test, ****P<0.0001. (c) Representative photo of initial methylcellulose plating from (b). (d) Box-and-whisker plots of percentage of peripheral blood CD45.2+ cells in competitive transplantation assays post-pIpC administration using CD45.2+ Mx1-cre control, Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/Y, and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/fl mice. For box and whiskers plots throughout, bar indicates median, box edges first and third quartile values, and whisker edges minimum and maximum values. (e) Box-and-whisker plots of absolute numbers of LSK and LT-HSCs in the bone marrow (BM) of recipient mice following 16 weeks of primary (top) and secondary transplantation (bottom) from (d). (f) Box-and-whisker plots of percentage of BrdU+ and Annexin-V+ LT-HSCs in BM of primary 6-week-old Zrsr2 KO and control mice. (g) Percentage of peripheral blood CD45.2+ cells in competitive transplantation assays pre- and post-pIpC administration using CD45.2+ Mx1-cre control (n=10), Sf3b1K700E/WT (n=9), Srsf2P95H/WT (n=8), Zrsr2fl/Y (n=10), and Tet2fl/fl (n=10) mice. Error bars, mean values +/− SEM. P values were calculated by two-sided t-test using the values at 4 months. (h) Absolute numbers of CD45.2+ LSK, LT-HSC, MPP, and ST-HSCs in the BM of recipient mice following 16 weeks of competitive transplantation from (g). P-values calculated relative to the control group by a two-sided t-test and indicated in the figures.

Prior work from several animal models of global deletion of core minor spliceosome components (including Rpnc3 in zebrafish and mice22,23 and small nuclear RNAs in D. melanogaster24) have identified that the minor spliceosome is required for development and survival. However, tissue-specific deletion of a minor spliceosome component has never been performed. In contrast to the loss of viability that results from pan-tissue deletion of the core minor spliceosome components Rpnc322,23 and the U11 snRNA25, we found that hematopoietic-specific Zrsr2 deletion in 6-week-old male and female mice enhanced the proliferation as well as clonogenic capacity of Zrsr2-null HSCs in vitro (Fig. 1b–c and Extended Data Fig. 2a–b).

We therefore evaluated the in vivo self-renewal capacity of Zrsr2-null HSCs by performing bone marrow (BM) competitive transplantation assays, wherein Zrsr2 was deleted following stable reconstitution of hematopoiesis with equal numbers of CD45.2+ Zrsr2-floxed and CD45.1+ wild-type (WT) hematopoietic cells in CD45.1 recipient mice (Extended Data Fig. 2c; in these experiments, Zrsr2 was deleted in recipient mice four weeks following transplantation via pIpC administration to recipients). These assays revealed strikingly enhanced self-renewal of Zrsr2-deficient male and female hematopoietic cells, both in primary and secondary transplantation (Fig. 1d; such an effect was not seen in females with heterozygous deletion of Zrsr2 (Extended Data Fig. 2d–e)). This was associated with increased numbers of Zrsr2-null mature B- and myeloid cells in the blood (Extended Data Fig. 2f) as well as LT-HSCs and LSK (lineage-negative Sca1+ c-Kit+) cells in the BM 16 weeks following primary and secondary transplantation (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 2g–h). Similar effects were seen in primary, non-transplanted Mx1-cre Zrsr2 knockout (KO) mice, where deletion of Zrsr2 increased numbers of long- and short-term HSCs as well as downstream progenitor populations (Extended Data Fig. 3a; deletion was induced at 6 weeks of age). Interestingly, Zrsr2 deletion was also associated with increased total BM mononuclear cells as well as LT-HSCs in the active phase of the cell cycle and undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 3b–c). Given that these phenotypes are key features of human MDS, we also performed detailed morphological assessments of hematopoietic tissues from primary Zrsr2 KO mice, which revealed modest morphologic evidence of dysplasia (Extended Data Fig. 3d–e). Overall, Mx1-cre Zrsr2 KO mice had numerically hastened death compared to littermate controls, but this did not reach statistical significance, and there were no significant differences in blood counts based on genotype (Extended Data Fig. 3f–g). Other than increased mature B220+ cells in blood and BM, numbers of B- and T-cell subsets in the BM, spleen, and thymus of Zrsr2 KO mice were unperturbed (Extended Data Fig. 3h–m).

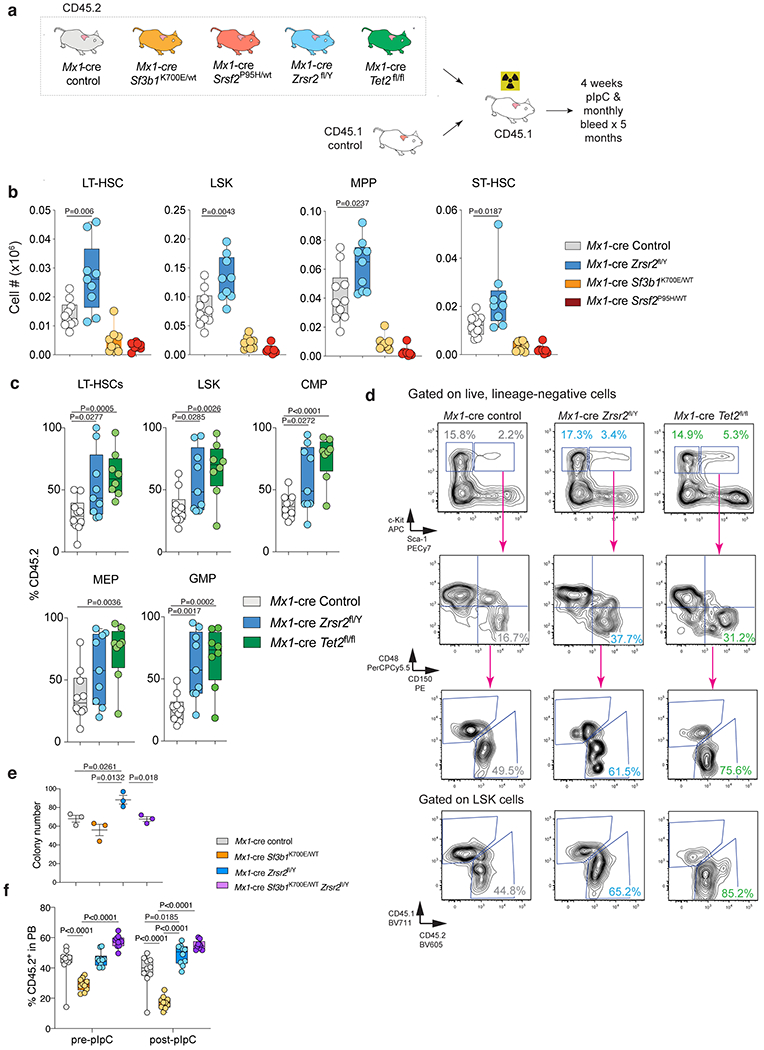

The above data, revealing enhanced self-renewal of Zrsr2-null HSCs, stands in stark contrast to recent work evaluating the effects of hotspot mutations in SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1, all of which identified a perplexing impairment in self-renewal when those mutations were induced in mice using similar transplantation methods13,26,27. We therefore repeated the above competitive transplantation assays using 6-week-old Mx1-cre Sf3b1K700E/WT and Mx1-cre Srsf2P95H/WT alongside Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/Y mice (Extended Data Fig. 4a). We additionally included Mx1-cre Tet2fl/fl mice, given the well-described effects of Tet2 loss on increasing self-renewal and numbers of HSCs in this system19. Similar to the effects of Tet2 deletion, Zrsr2 loss again resulted in increased competitive advantage in vivo (Fig. 1g). This advantage was seen in the numbers and percentages of BM hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) (Fig. 1h and Extended Data Fig. 4b–d). Moreover, the effect of Zrsr2 loss was strikingly distinct from the effects of inducing leukemia-associated mutations in Sf3b1 and Srsf2, which were associated with near-complete loss of hematopoiesis (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 4b). Interestingly, deletion of Zrsr2 in the context of mutant Sf3b1 rescued the impaired clonogenic capacity of Sf3b1K700E/WT hematopoietic precursor cells (Extended Data Fig. 4e–f). These data are quite distinct from prior reports of the lethal phenotype of combined Sf3b1K700E and Srsf2P95H mutations28 and may explain the occasional co-occurrence of SF3B1 and ZRSR2 mutations in myeloid neoplasm patients29.

Global impairment in minor retention with ZRSR2 loss

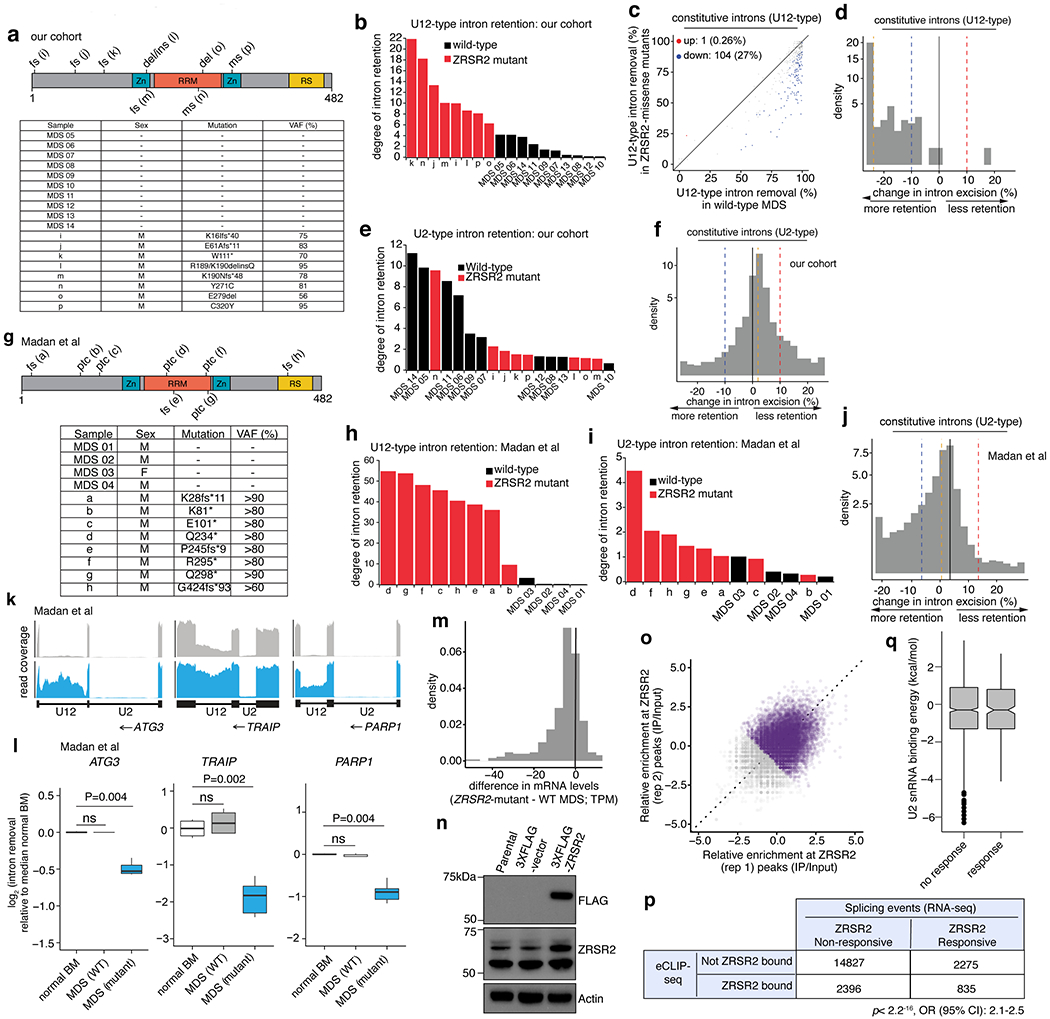

We next sought to understand the mechanistic basis by which ZRSR2 loss causes aberrant HSC self-renewal and MDS. We performed high-coverage RNA-seq on BM samples from MDS patients with diverse ZRSR2 mutations (n=8) and MDS patients lacking any spliceosomal gene mutations (n=10) and quantified transcriptome-wide splicing patterns (Extended Data Fig. 5a, Supplementary Tables 1–2). ZRSR2-mutant samples were characterized by widespread, dysfunctional recognition of U12-type introns, with over one-third of U12-type introns exhibiting significantly increased retention (Fig. 2a–b). All ZRSR2-mutant samples exhibited U12-type intron retention, indicating that the diverse ZRSR2 lesions represented in our cohort converge on loss of function (Extended Data Fig. 5b–d). Aberrant intron retention was specific to the minor spliceosome: we observed no transcriptome-wide association between ZRSR2 mutations and levels of U2-type intron retention (Extended Data Fig. 5e–f). We confirmed the robustness of our results by re-analyzing data from a published cohort of MDS samples (Extended Data Fig. 5g, Supplementary Table 3)9. ZRSR2-mutant samples in this cohort were similarly characterized by transcriptome-wide U12-type intron retention (Fig. 2c–d and Extended Data Fig. 5h). However, in contrast to our cohort, U2-type introns were also frequently retained in most ZRSR2-mutant samples (Extended Data Fig. 5i–j). As the two patient cohorts represented different ZRSR2 mutational spectra, exhibited both similarities and differences in their splicing programs, and were orthogonally collected, we hypothesized that convergently mis-spliced genes might be particularly important for disease pathogenesis. We observed a striking overlap in aberrantly retained U12-type introns, with ~94% of all U12-type introns that were retained in our cohort also retained in the previously published cohort9 (Fig. 2e). In contrast, very few (~4%) aberrantly retained U2-type introns were shared between cohorts (Fig. 2f).

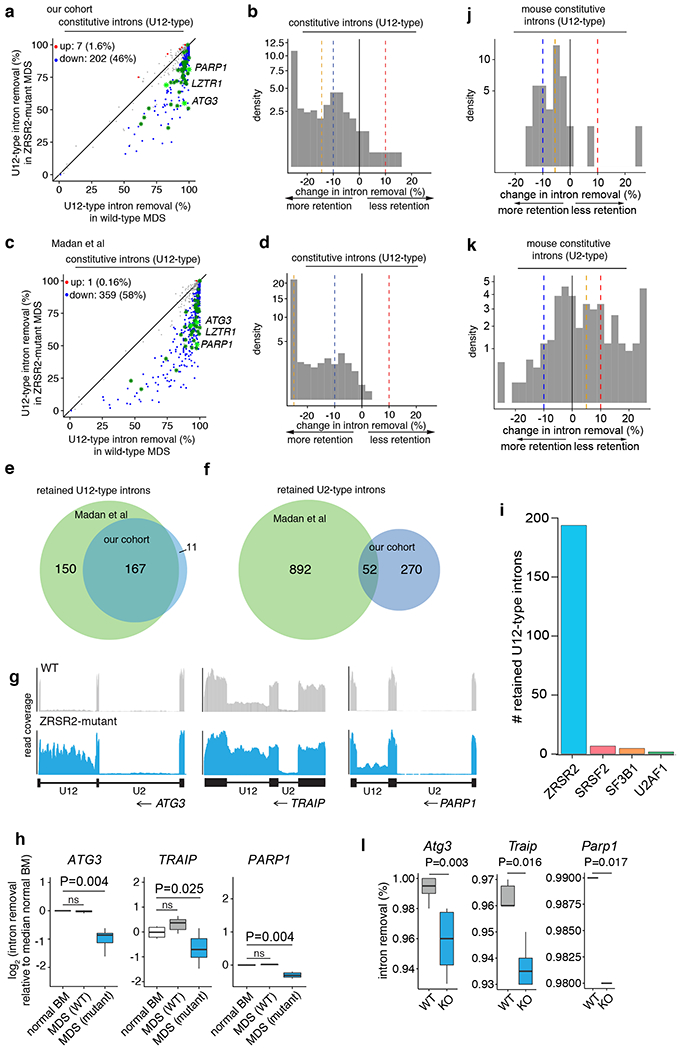

Figure 2. Widespread minor intron retention with ZRSR2 loss.

(a) Genome-wide quantification of differential splicing of U12-type introns from our patient cohort with key overlapping mis-spliced mRNAs in mouse hematopoietic precursors (green). Each point corresponds to a single intron and illustrates percentage of mRNAs in which the intron is spliced out. Blue/red dots: introns that exhibit significantly increased/decreased retention in ZRSR2-mutant versus WT cells, defined as an absolute change in retention of ≥10% or absolute log fold-change of ≥2 with associated p≤0.05. Green asterisks: minor introns differentially retained in both patient and mouse; light green asterisks: minor introns in genes of particular interest (Parp1, Lztr1, and Atg3). P-values, two-sided Mann-Whitney U test without adjustments for multiple comparisons. (b) Distribution of U12-type intron retention in ZRSR2-mutant samples (n=8 mutant and 10 wild-type). Blue/red dashed lines: thresholds of −10% and 10% for differential retention; gold line: median change in intron retention. (c) As (a), but for Madan at al cohort. (d) As (b), but for Madan et al cohort. (e) Overlap of U12-type intron retention events between the two patient cohorts (n=8 mutant and 4 wild-type). (f) As (e), but for U2-type introns. (g) RNA-seq coverage plots of U12-type, but not U2-type, intron retention in our patient cohort. Plots averaged over all samples with indicated genotypes. (h) Box plots quantifying splicing efficiencies of introns illustrated in (g) relative to normal marrow (median of 4 normal samples from Madan et al). P-values by two-sided Mann-Whitney U test. (i) Numbers of retained U12-type introns in samples bearing any of the four spliceosomal gene mutations from Beat AML cohort. Distribution of (j) U12-type or (k) U2-type intron retention in Zrsr2-knockout relative to wild-type mouse precursors. Blue/red dashed lines indicate thresholds of −10% and 10% used for differential retention; gold line: median change in intron retention. (l) Box plots illustrating intron splicing efficiencies in mouse lineage-negative c-Kit+ cells. For (h) and (l), the middle line, hinges, notches and whiskers indicate the median, 25th/75th percentiles, 95% confidence interval and most extreme data points within 1.5× interquartile range from hinge. P-values by two-sided Mann-Whitney U test.

Closer inspection of genes of potential disease relevance confirmed the robustness and specificity of U12-type intron retention in ZRSR2-mutant samples. Minor spliceosome-dependent genes such as ATG3, TRAIP, and PARP1 exhibited striking retention of a single U12-type intron with adjacent U2-type introns normally spliced (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 5k). In each case, the U12-type intron was specifically retained in ZRSR2-mutant MDS, but not in MDS without spliceosomal mutations, relative to normal BM in both cohorts (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 5l). To further evaluate the specificity of minor intron splicing across leukemia-associated spliceosomal gene mutations, we quantified the number of retained U12-type introns across patients with bona fide deleterious mutations in ZRSR2 versus known hotspot mutations in SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1 in the 427 AML patients from the Beat AML study30. This analysis revealed a striking enrichment for U12-type intron retention in ZRSR2-mutant patients, but no such enrichment for patients with SF3B1, SRSF2, or U2AF1 mutations (Fig. 2i). U12-type intron retention was generally associated with downregulated mRNA expression of U12-type intron-containing genes (Extended Data Fig. 5m).

Consistent with the effect of ZRSR2 mutations in MDS on splicing, hematopoietic precursors (lineage− c-Kit+ cells) from mice deficient for Zrsr2 exhibited global increases in U12-type intron retention without significant changes in U2-type splicing (Fig. 2a and Fig. 2j–k; RNA-seq analysis was performed two months following pIpC administration to 6-week-old Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y and Mx1-cre control mice). Moreover, a number of overlapping U12-type introns were similarly retained in BM of Zrsr2 KO, but not control mice – consistent with the high conservation of U12-type introns (Fig. 2a,l, and Supplementary Table 4). These comparisons strongly suggest that U12-type intron retention is the central molecular phenotype of ZRSR2 mutations, and that U2-type intron retention is a sporadic occurrence that only characterizes a subset of cases of ZRSR2-mutant MDS.

Mapping direct RNA binding targets of ZRSR2

As the above data identify a strong functional link between ZRSR2 and minor introns, we next sought to understand the mechanistic basis for this relationship by identifying direct binding targets of ZRSR2 on RNA. We therefore performed anti-ZRSR2 eCLIP-seq31 (enhanced UV crosslinking immunoprecipitation followed by next-generation sequencing) in human myeloid leukemia (K562) cells (Extended Data Fig. 5n–o). This revealed that ~80% of ZRSR2 binding sites mapped to exons, with a highly significant enrichment for ZRSR2 binding to minor intron-containing genes whose minor intron was responsive versus non-responsive to ZRSR2 mutations (Fig. 3a–b and Extended Data Fig. 5p; p-value < 2.2e−16 with an odds ratio in the range (95% CI): 2.1-2.5). ZRSR2 binding was specifically enriched in minor introns, consistent with our analyses of the effects of ZRSR2 loss on minor intron retention (Fig. 3c). Finally, ZRSR2-bound mRNAs are enriched for mRNAs encoding RNA regulatory proteins as well as genes with known involvement in leukemia and protein processing and translation (Fig. 3d). Overall, these analyses identify that minor intron-containing genes whose splicing is regulated by ZRSR2 are direct binding targets of ZRSR2.

Figure 3. ZRSR2 RNA binding targets and features of ZRSR2-responsive introns.

(a) Genomic distribution of ZRSR2 eCLIP-seq (enhanced UV crosslinking immunoprecipitation followed by next-generation sequencing) peaks. (b) Metaplot of ZRSR2 eCLIP sequencing reads at ZRSR2-regulated minor introns. (c) Fisher’s exact test analysis evaluating the enrichment of ZRSR2 within responsive introns and each flanking exon by eCLIP-seq in genes with ZRSR2-responsive introns or those with ZRSR2 binding. (d) Gene ontology analysis of ZRSR2-bound genes by eCLIP-seq. (e) Histogram of the locations of branchpoints relative to the 3’ splice site (3’ss) in U2- versus U12-type constitutive introns. (f) Histogram of the locations of branchpoints relative to the 3’ss for ZRSR2 non-responsive versus responsive minor introns (p-value estimated by a two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). (g) Branchpoint nucleotide preference for ZRSR2 non-responsive versus responsive minor introns (p-value estimated with a two-sided binomial proportion test for a difference in fraction of adenine branchpoints). (h) Mean number of branchpoints within ZRSR2 non-responsive versus responsive minor introns (p-value estimated by a two-sided t-test). Error bars represent ± 1 standard error of the mean (sd/sqrt(n)). (i) U12 snRNA binding energy for branchpoint motifs in ZRSR2 non-responsive versus responsive minor introns (p-value estimated by a two-sided Mann-Whitney U test). (j) Sequence logo plots of the 3’ss of ZRSR2-responsive versus non-responsive introns (upward arrow indicates site of 3’ss). As shown, ZRSR2-responsive introns have weaker/less-defined polypyrimidine tracts. (k) G:A ratio at the +1 position (relative to the 3’ss). Error bars represent ± 1 s.d. estimated by bootstrapping (10k iterations). P-value = 0 by two-sided Mann-Whitney U test.

Both the RNA-seq and eCLIP-seq analyses above identified that only approximately one-third of U12-type intron-containing genes are sensitive to loss of ZRSR2. In order to understand the specificity of ZRSR2 for regulation of the splicing of minor introns and why only a portion of minor introns are regulated by ZRSR2, we next evaluated the sequence features of introns which were retained upon ZRSR2 loss.

Characteristics of ZRSR2 regulated introns

We previously reported that while branchpoints within U2-type introns are highly constrained in their location, branchpoints within U12-type introns exhibit a bimodal distribution, such that half of U12-type introns have branchpoints similar in location to U2-type branchpoints while half of U12-type branchpoints occur in closer proximity (within 20 nucleotides (nt)) of the 3’ splice site (3’ss)32 (Fig. 3e). To test whether this bimodality was relevant to ZRSR2 responsiveness, we augmented our previously published branchpoint annotation by querying available RNA-seq data from cohorts within The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to search for lariat-derived reads which span the 5’ splice site-branchpoint junction within minor introns. Such reads are extremely rare due to typically rapid lariat degradation—hence the need for an extremely large-scale analysis—but allow for inference of branchpoint location with nucleotide-level resolution. Using this large U12-type branchpoint annotation, we discovered that introns that respond to ZRSR2 loss had branchpoints that were significantly more proximal to the 3’ss than did non-responsive introns (two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test p<2.2e-16; Fig. 3f). In contrast, non-responsive U12-type introns exhibited no such spatially restricted enrichment, suggesting that branchpoint location influences U12-type intron susceptibility to retention in the absence of ZRSR232. We therefore examined the branchpoint more closely as a potential determinant of response to ZRSR2 loss. This revealed that ZRSR2-responsive introns prefer adenosine nucleotides as branchpoints (Fig. 3g; p=1.5×10−5 by two-sided binomial proportion test); have more branchpoints per intron compared to ZRSR2 non-responsive introns (Fig. 3h; p=0.03 by two-sided t-test); and have branchpoints that more closely match the U12 snRNA consensus sequence (Fig. 3i; p=5.2e10−16 by Wilcoxon rank sum test). ZRSR2-responsive minor introns additionally have less-defined polypyrimidine tracts and a reduced preference for G at the +1 position compared to non-responsive introns (Fig. 3j,k and Extended Data Fig. 5q). Overall, these data identify that U12-type introns fall into two classes: those which are resistant to ZRSR2 loss and those which respond strongly to ZRSR2 loss. Responsive introns are typically characterized by a 3’ss-proximal, adenosine branchpoint that is surrounded by nucleotides that closely resemble the U12 snRNA consensus, as well as having a weak or absent polypyrimidine tract.

Positive enrichment screen of ZRSR2 regulated events

One major challenge with understanding how RNA splicing factor mutations cause disease is determining whether the observed phenotypes are causally linked to one or many aberrant splicing changes. Our transcriptomic analyses revealed that only a subset of minor spliceosome-dependent genes are recurrently and robustly mis-spliced, suggesting that not all U12-type introns are equally important for disease pathogenesis.

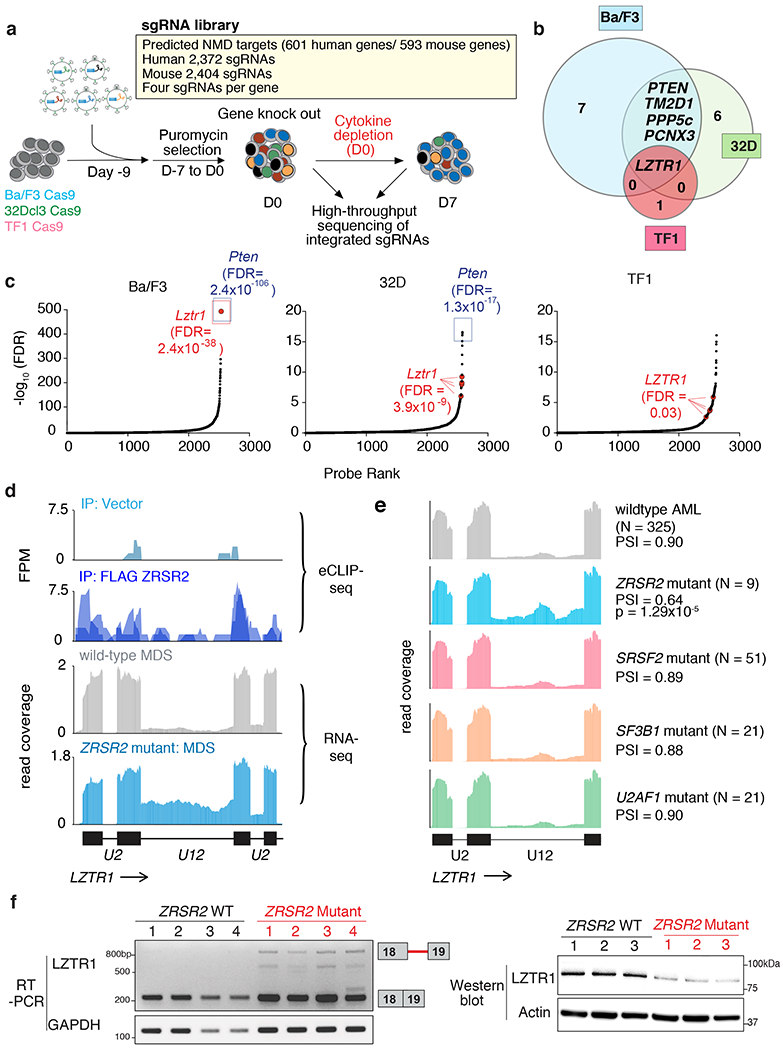

We therefore systematically evaluated the potential role of each U12-type intron retention event in cell transformation with a functional genomic screen. We mimicked the effects of nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) caused by loss of minor intron splicing and subsequent open reading frame disruption in ZRSR2-mutant cells via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout. In this assay, the protein-coding region of each of the 601 genes whose mRNAs were identified as differentially spliced in ZRSR2-mutant MDS patient samples versus spliceosomal wild-type MDS patients and predicted to result in NMD (Supplementary Tables 2–3) was targeted by 4 single guide RNAs (sgRNAs). This was performed as a positive-enrichment CRISPR screen using pools of lentiviral sgRNAs in cytokine-dependent mouse (32D, Ba/F3) and human (TF1) hematopoietic cell lines stably expressing Cas9 (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Tables 5–9; similar to an approach we recently used to model mutant SF3B1-induced aberrant splicing events33). Following stable infection with the sgRNA library, cytokines were depleted and sgRNA representation was evaluated pre- and 7 days post-cytokine removal.

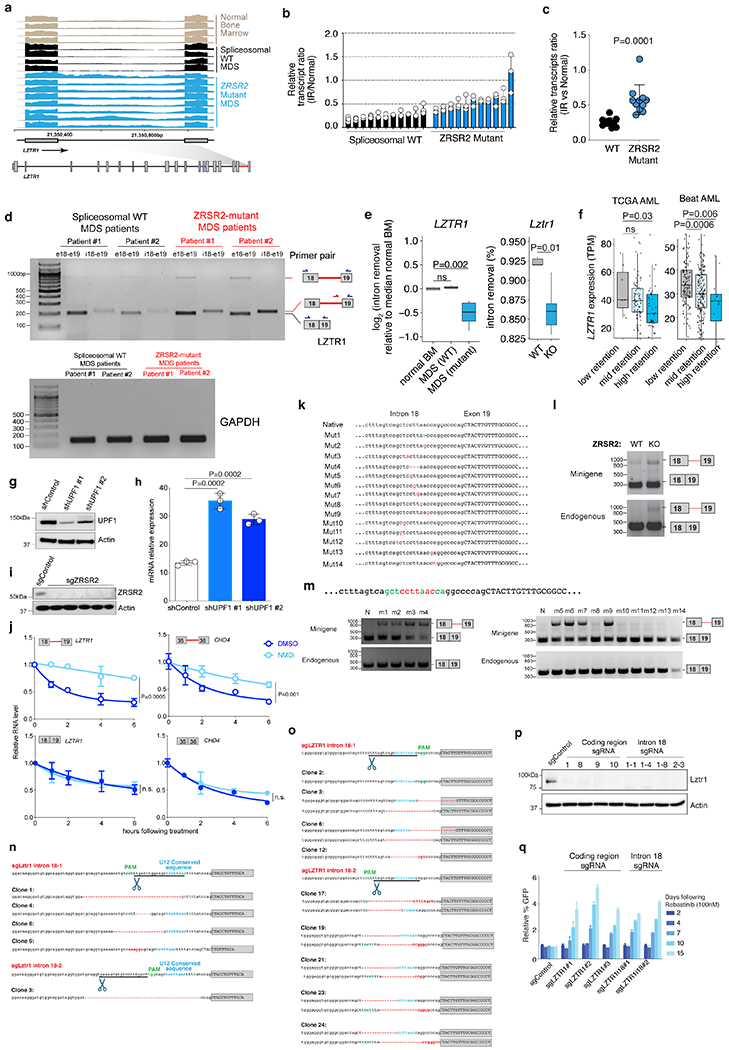

Figure 4. Impaired LZTR1 minor intron excision confers competitive advantage.

(a) Schematic of positive enrichment custom CRISPR-Cas9 pooled lentiviral screen to identify functionally important ZRSR2 regulated minor intron splicing events. (b) Venn diagram of genes targeted by sgRNAs in the screen in (a) across Ba/F3, 32D, and TF1 cells. Numbers of genes identified in the screen in each segment of the Venn diagram is displayed. (c) Rank plot for the −log10(FDR) associated with each sgRNA in screen from (a). sgRNAs targeting the positive control (Pten) and Lztr1 are highlighted. For the probe-level (per-sgRNA) analysis, we fitted a negative binomial generalized log-linear model and performed a likelihood ratio test. FDR values were computed using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. (d) Top, eCLIP-seq for FLAG immunoprecipitation from FLAG empty vector or FLAG-ZRSR2 over the region of LZTR1’s minor intron. Biological duplicate immunoprecipitation data are overlaid. Bottom, RNA-seq coverage over the same locus in primary human MDS samples, with wild-type MDS colored gray (top) and ZRSR2-mutant MDS (bottom) colored blue. (e) RNA-seq coverage plots across the U12-type intron of LZTR1 for patients from Beat AML with the indicated genotypes. Each coverage plot represents an average across all samples with the indicated genotype following normalization to the total number of reads mapped to the coding genes for each sample. PSI, fraction of spliced mRNA. (f) Qualitative RT-PCR gel for LZTR1 minor intron excision (left) and LZTR1 protein levels (right) in representative MDS patient samples WT or mutant for ZRSR2 (n=4 distinct patient samples/genotype for RT-PCR and n=3 distinct patient samples/genotype for Western).

This screen revealed several minor intron-containing genes whose downregulation conferred cytokine independence to one or more cell lines (Fig. 4b). Strikingly, just one gene was significantly enriched in all three cell lines (Fig. 4c): LZTR1, which encodes a cullin-3 adaptor regulating ubiquitin-mediated suppression of RAS-related GTPases10–12, and is subject to loss-of-function mutations in glioblastoma34, schwannomatosis35, and the RASopathy known as Noonan Syndrome36 (of note, anti-PTEN sgRNAs were included here as a positive sgRNA control; although PTEN has a minor intron, its splicing did not consistently differ between ZRSR2 WT and mutant cells). Inspection of the transcriptomic data from primary patient samples confirmed the link between aberrant splicing of LZTR1 and MDS pathogenesis, as we identified retention of a U12-type intron in LZTR1 (intron 18) in samples harboring ZRSR2 mutations (which was specific to ZRSR2-mutant MDS compared to BM samples from ZRSR2 wild-type MDS and normal subjects; Fig. 4d). Importantly, this same region is a direct binding target of ZRSR2 as revealed by eCLIP-seq in human myeloid leukemia cells (Fig. 4d). Moreover, this mis-splicing of LZTR1 was specific to ZRSR2-mutant AML patients versus those with other spliceosomal gene mutations (Fig. 4e). Consistent with intron retention causing NMD-inducing reading frame disruption, minor intron retention in LZTR1 correlated with reduced LZTR1 mRNA and protein levels in primary MDS and AML patient samples as well as mouse hematopoietic precursors (Fig. 4f, Extended Data Fig. 6a–f, and Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, blocking NMD by knockdown of UPF1, a core component of the NMD machinery or pharmacologic inhibition of NMD, in ZRSR2 KO cells increased the mRNA stability and expression of the minor intron-retained forms of LZTR1 and an additional ZRSR2-regulated intron in CHD4 (Extended Data Fig. 6g–j). These data formally confirm that these U12-type intron-containing isoforms are NMD substrates.

LZTR1 intron retention is transforming

Our functional screens revealed that LZTR1 knockout was associated with a uniquely robust competitive advantage, but CRISPR-based gene knockout is an imperfect model of LZTR1 loss due to impaired removal of its minor intron. To address this, we took advantage of a PAM (protospacer adjacent motif) site deep within intron 18 of LZTR1, which is located adjacent to a highly conserved sequence matching the consensus motif for the minor intron branchpoint (Fig. 5a). Although recent work from our group identified that most introns use multiple branchpoints32, we analyzed intron lariat-derived reads from RNA-seq data and identified that this highly conserved sequence within LZTR1’s intron 18 contained just a single branchpoint nucleotide (Fig. 5b) located proximal to the 3’ss, consistent with our genomic analysis of minor introns that were vulnerable to ZRSR2 loss (Fig. 3e–f). To functionally evaluate the requirement for this putative branchpoint and the surrounding U12 consensus sequence for splicing of LZTR1, we generated a minigene of LZTR1’s minor intron and flanking exons from human cells and performed extensive mutagenesis reactions. This verified that LZTR1 is spliced less efficiently in ZRSR2-null cells compared to wild-type cells, and identified the conserved U12 intronic sequence as required for ZRSR2-dependent excision of the minor intron (Fig. 5c; Extended Data Fig. 6k–m).

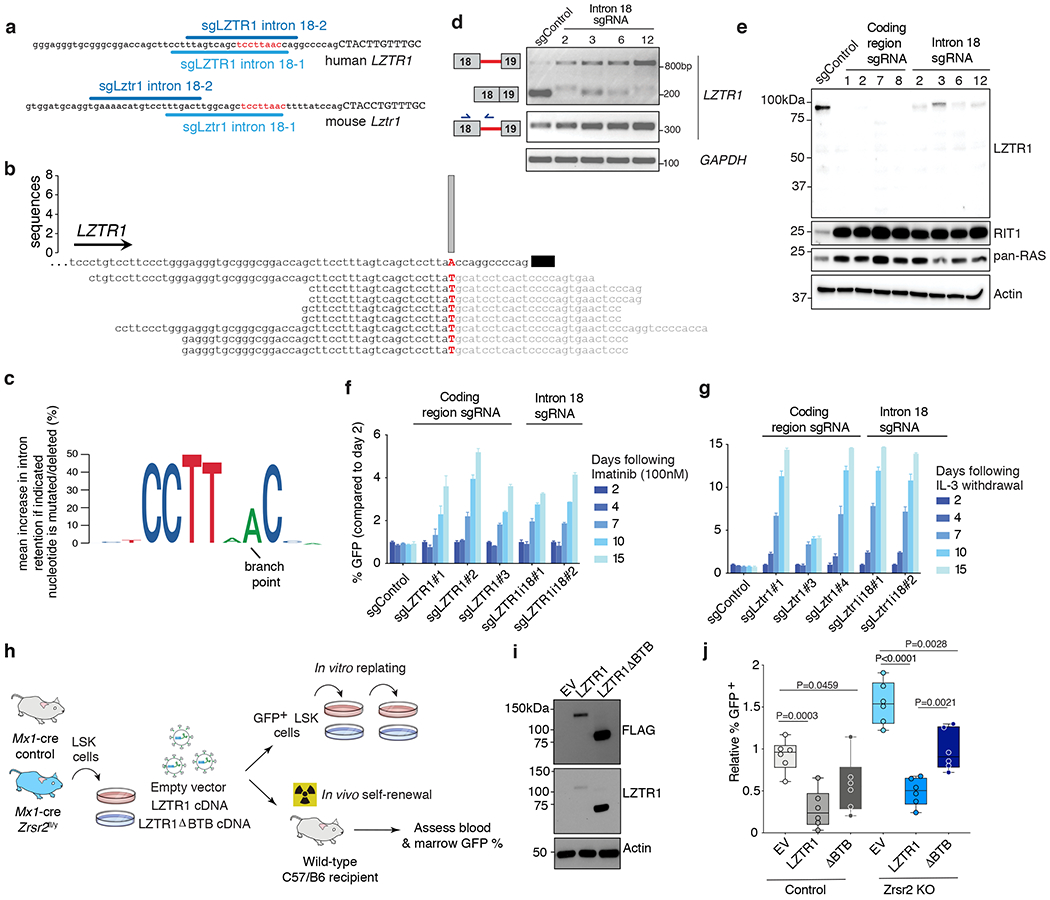

Figure 5. Impaired LZTR1 minor intron excision promotes clonal advantage and effects of LZTR1 re-expression on Zrsr2 null hematopoietic cells.

(a) Schematic of the minor intron branchpoint binding region in LZTR1 intron 18 with illustration of intronic sgRNA binding sequences (U12 conserved sequence in red). (b) Branchpoint within LZTR1’s minor intron based on intron lariat-derived RNA-seq reads. Bar represents number of supporting high-confidence reads, defined as those with a single identifying mismatch at the branchpoint characteristic of traversal of the 2’-5’ linkage. (c) Logo plot representation of minigene experiments summarizing mean increase in intron retention if indicated nucleotide is mutated (%). The height of each nucleotide indicates its requirement for normal excision of LZTR1’s minor intron. (d) RT-PCR for LZTR1 intron 18 excision in K562 AML single cell clones treated with intron 18-targeting sgRNAs. Experiment repeated three times with similar results. (e) Full-length WB of LZTR1 using N-terminal antibody as well as K-, N-, and H-RAS (“pan-RAS”) in K562 single cell clones treated with sgRNAs targeting protein-coding versus intronic sequence of LZTR1. Experiment repeated three times with similar results. (f-g) Relative percentage of (f) GFP-labeled K562 cells from (d) mixed with equal proportions of unlabeled cells to imatinib and (g) Ba/F3 cells treated with sgRNAs targeting the protein-coding region of LZTR1 following IL-3 withdrawal (median % relative to day 2 is plotted). (h) Schema of LZTR1 cDNA experiment. Lineage-negative cells from Mx1-cre Zrsr2 control and Zrsr2fl/y mice expressing empty vector, LZTR1 cDNA, or LZTR1 cDNA lacking BTB domains (“ΔBTB”). DAPI− GFP+ LSK+ cells were then sorted and tested for replating capacity or transplanted into mice. (i) Western blot of FLAG and LZTR1 in N-terminal FLAG-tagged empty vector (EV), LZTR1, and ΔBTB LZTR1. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. (j) Relative % GFP+ blood cells from mice receiving lineage-negative cells from Mx1-cre Zrsr2 control or Zrsr2fl/y expressing constructs from (h). Mean value ± SEM shown. Bar indicates median, box edges first and third quartile values, and whisker edges minimum and maximum values. P-values calculated relative to the control group by a two-sided t-test and indicated in the figures.

Delivering sgRNAs targeting the intronic U12 consensus sequence of LZTR1 (which is 10 nucleotides from the closest protein coding region of LZTR1) induced robust LZTR1 intron 18 retention in polyclonal mouse and human cells (Fig. 5d). We therefore generated multiple clones of LZTR1 minor intron-mutant human K562 and Ba/F3 cells (Extended Data Fig. 6n–o) and compared the effects of impaired LZTR1 minor intron excision with deleterious mutations in LZTR1’s protein coding sequence. This revealed that both direct disruption of LZTR1’s protein coding sequence and induction of minor intron retention virtually abolished LZTR1 protein expression, without generating a truncated LZTR1 protein product (Fig. 5e and Extended Data Fig. 6p). Similarly, inducing mutations within either the protein-coding region of LZTR1 or its minor intron resulted in dramatic accumulation of RAS proteins, including RIT1, a RAS GTPase recently identified as an endogenous substrate of LZTR111, and a gene known to undergo activating mutations in RASopathies and a variety of cancers37,38. Consistent with these convergent effects of protein-coding mutations and minor intron retention in LZTR1, both perturbations conferred cytokine independence to Ba/F3 cells as well as BCR-ABL inhibitor resistance to K562 cells (Fig. 5f–g; a phenotype original used to identify LZTR1 as a regulator of MAPK signaling10). In fact, mutagenesis of exact branchpoint nucleotide within LZTR1’s intron 18 rendered K562 cells resistant to ATP-dependent or -independent ABL kinase inhibitors (imatinib or rebastinib, respectively (Fig. 5f and Extended Data Fig. 6q)). Finally, we evaluated the impact of mutagenesis of Lztr1’s minor intron on the clonogenic capacity of mouse HSPCs. This was performed by generation of HSC-specific conditional Cas9 knockin mice by crossing HSC-Scl-CreERT Zrsr2 wild-type or Zrsr2fl/y mice with Rosa26-Lox-STOP-Lox-Cas9-EGFP knockin mice. Infection of bone marrow cells from these mice with sgRNAs targeting the conserved U12 sequence of Lztr1’s minor intron strongly promoted replating capacity of Zrsr2 wild-type, but not Zrsr2 mutant, HSPCs (Extended Data Fig. 7a–b). Conversely, restoring expression of LZTR1 in Zrsr2-KO HSPCs strongly impaired their replating capacity as well as their self-renewal in vivo (which was not seen with expression of a version of LZTR1 lacking the BTB domains required for cullin-3 interaction and LZTR1 function; Fig. 5h–j and Extended Data Fig. 7c–d). These data further confirm the impact of impaired Lztr1 minor intron excision on clonogenic capacity. Of note, although RIT1 was clearly upregulated upon LZTR1 downregulation, the effects of LZTR1 downregulation were not solely dependent on RIT1 (Extended Data Fig. 7e–f). This latter point likely reflects the upregulation of multiple RAS proteins upon LZTR1 loss and underscores the need for future efforts to systematically identify LZTR1-regulated substrates in hematopoietic cells.

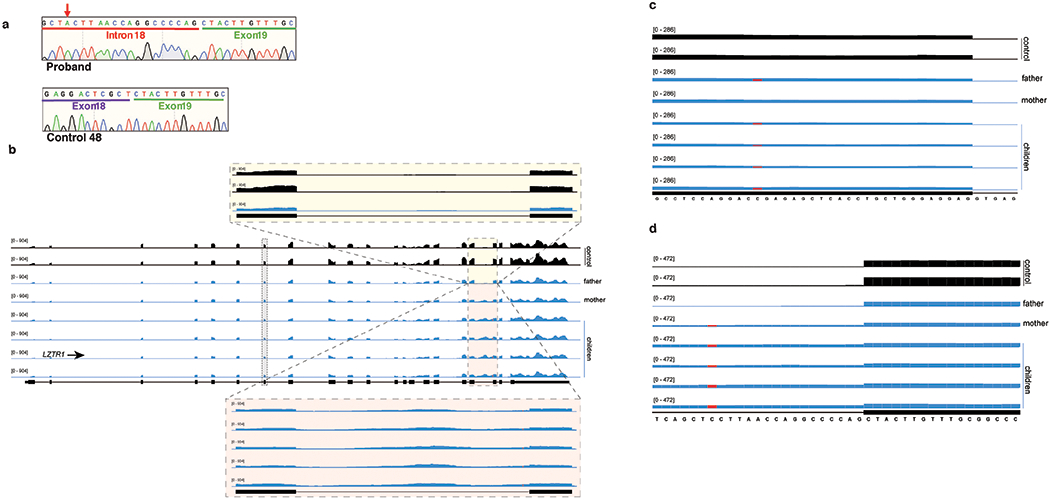

Impaired LZTR1 splicing in Noonan Syndrome and cancer

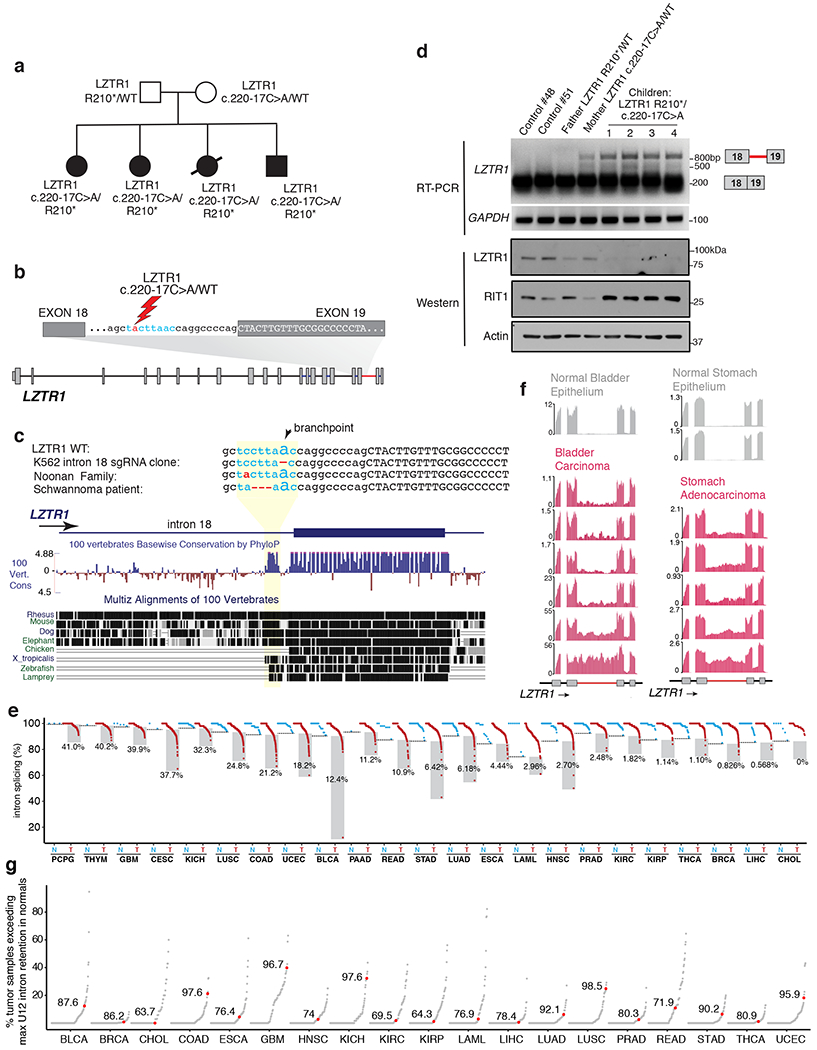

Our finding that mutagenesis of deep intronic sequences within LZTR1’s minor intron transformed cells, combined with the fact that LZTR1 is recurrently affected by protein-coding mutations in a variety of cancers34,35, led us to search for aberrant LZTR1 minor intron excision beyond the context of ZRSR2-mutant MDS. We first studied cancer predisposition syndromes. Interestingly, in one reported family with autosomal recessive Noonan Syndrome wherein one child died of AML36, the mother and all four children carried an intronic mutation within the branchpoint-containing region that we identified within LZTR1’s minor intron (c.2220-17C>A; Fig. 6a–b). This same sequence is also mutated in schwannomatosis35 (Fig. 6c). We established immortalized fibroblasts from each family member and unrelated controls and identified clear LZTR1 minor intron retention with consequently impaired LZTR1 protein expression and RIT1 accumulation in subjects bearing the LZTR1 minor intron mutation (Fig. 6d and Extended Data Fig. 8a–d).

Figure 6. Aberrant LZTR1 minor intron retention in Noonan Syndrome, schwannomatosis, and diverse cancers.

(a) Pedigree of Noonan syndrome family where mother and all four offspring contain a mutation within the conserved U12 branchpoint sequence in LZTR1 intron 18. All four children were diagnosed with Noonan Syndrome and the proband (black circle) developed AML. (b) Schematic of location of the intronic c.220-17C>A mutation. Intronic nucleotides in blue represent conserved U12 sequence. (c) Sequence conservation of the LZTR1 minor intron 3’ conserved sequence and surrounding intronic and exonic sequence (as estimated by phyloP39). The location of the LZTR1 intron 18 branchpoint as well as mutations in a K562 single cell clone, the Noonan family from (a), and a schwannoma patient35 bearing mutations in this region shown. Conservation and repetitive element annotation from the UCSC Genome Browser40. (d) Qualitative RT-PCR gel for LZTR1 intron 18 excision (top) and LZTR1 and RIT1 protein levels (bottom) in immortalized skin fibroblasts from the subjects in (a) as well as two healthy control subjects. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (e) Splicing of LZTR1’s minor intron across peritumoral normal (N) and tumor (T) samples in cancers from the indicated TCGA cohorts with available matched normal samples. Normal samples for LAML comparison from ref41. The horizontal dotted line in each normal column represents the maximum intron retention observed in normal control samples for each cancer type. Shaded box indicates cancer samples exceeding maximum intron retention in normal. The percentage next to each box indicates per cancer-type percentage of cancer samples with high intron retention. (f) Representative RNA-seq coverage plots for LZTR1’s minor intron in bladder and stomach carcinoma and peritumoral normal samples. (g) Degree of minor (U12-type) intron retention across normal (N) and tumor (T) samples in cancers from the TCGA. Each point corresponds to a single U12-type intron and indicates the percentage of all tumor samples in which retention of that intron exceeds the maximum corresponding retention of that intron observed in normal samples. Red dot indicates the U12-type intron of LZTR1; number indicates its percentile rank compared to all other U12-type introns.

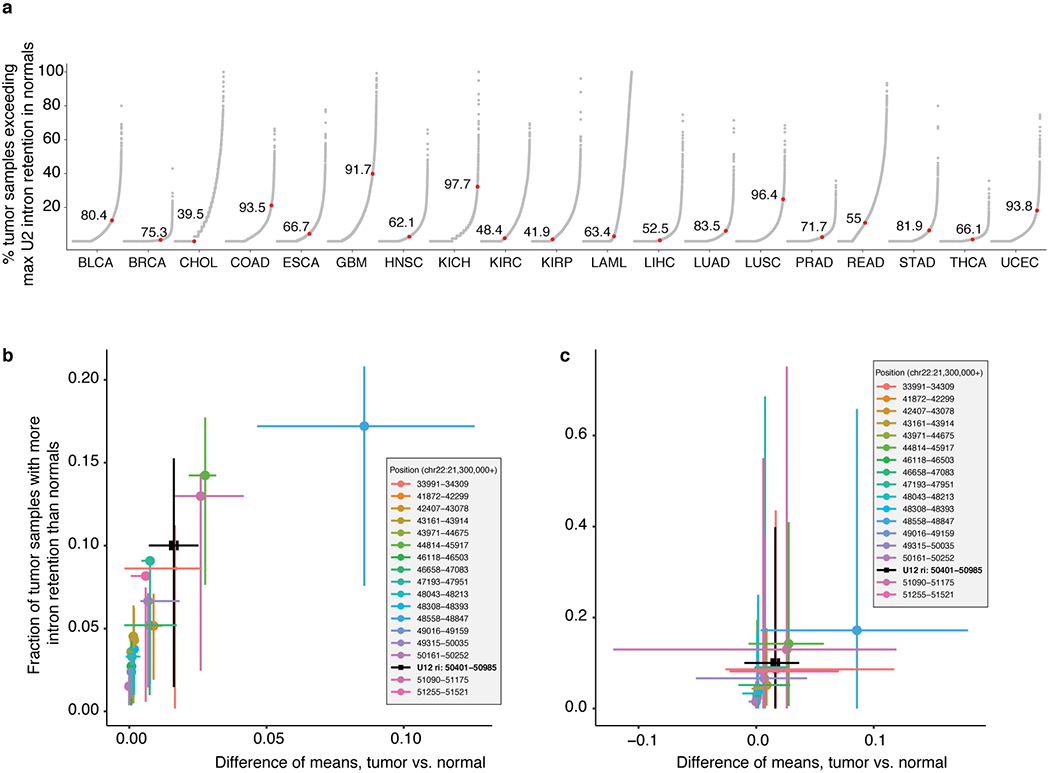

We next interrogated LZTR1 minor intron splicing across the diverse cancer types profiled by TCGA. LZTR1’s minor intron was efficiently excised in all normal samples. However, a notable subset of tumors in almost all profiled cancer types exhibited significantly increased retention that was specific to LZTR1’s minor intron. The extent of LZTR1 intron retention varied between samples and across cancer types, with a total of 11.1% of all profiled cancer samples exhibiting LZTR1 minor intron retention exceeding that observed in any peritumoral control normal tissues (Fig. 6e). In some cases, this intron retention was comparable to that observed in ZRSR2-mutant MDS, even though ZRSR2 and other minor spliceosomal factors are not recurrently mutated in those cancers (Fig. 6f). Moreover, we performed systematic analysis of U12-type as well as U2-type intron retention across all alternative introns across cancers in the TCGA datasets and evaluated the degree of LZTR1 U12-type intron retention in this context. This analysis revealed that LZTR1’s minor intron is among the most frequently retained introns across cancer types (top 10% of retained minor introns across all cancers; Fig. 6g and Extended Data Fig. 9a).

DISCUSSION

Since the discovery of a second, independent spliceosome in most metazoans over 20 years ago2, many questions regarding the role of minor introns in cellular physiology and disease have been enigmatic. Here, we uncover a heretofore unrecognized role of minor intron excision in regulating HSC self-renewal, a molecular link between ZRSR2 mutations and aberrant LZTR1 splicing and expression, and frequent LZTR1 U12-type intron retention in diverse cancers and cancer predisposition syndromes.

Interestingly, the most common somatic mutation in LZTR1 reported to date affects a splice site12. Given the prevalence of LZTR1 deep intronic mutations in cancer predisposition syndromes, it is reasonable to hypothesize that LZTR1’s minor intron may be similarly subject to somatic mutations not detected by whole-exome sequencing. Consistent with this concept, LZTR1 intron retention is not limited to the U12-type intron of LZTR1; several U2-type LZTR1 introns are also commonly retained in tumors relative to normal tissues (Extended Data Fig. 9b–c).

Overall, these analyses indicate that LZTR1 is frequently dysregulated via perturbed minor intron splicing – much more so than revealed by studying protein-coding mutations alone. Given our finding of frequent post-transcriptional disruption of LZTR1 in the absence of protein-coding mutations, our data motivate study of other cancer-associated minor intron-containing genes which may be dysregulated via similar, and as-yet-undetected, aberrant splicing.

METHODS

Patient samples

Studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and conducted in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki protocol. Informed consents were obtained from all human subjects. Next-generation sequencing was performed on DNA extracted from bone marrow mononuclear cells and matched normal from fingernails. Patient samples were sequenced with MSK-IMPACT targeted sequencing panel, with somatic mutations (substitutions and small insertions and deletions), gene-level focal copy number alterations, and structural rearrangements were detected with a clinically validated pipeline as previously described 42,43.

Animals

All animals were housed at MSKCC using a 12 light/12 dark cycle and with ambient temperature maintained at 72°F ± 2°F (~21.5°C ± 1°C) with 30-70% humidity. All animal procedures were completed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at MSKCC. All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the MSKCC IACUC (11-12-029).

Generation of Zrsr2 conditional knockout (cKO) mice

Please see Supplemental Note for full details.

Genetically engineered mice other than Zrsr2 cKO

Sf3b1K700E, Srsf2P95H, HSC-Scl-CreERT, Rosa26-Lox-STOP-Lox-Cas9-EGFP, Tet2 floxed, and Mx1-cre mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and were previously generated and described13,19,26 with the exception of HSC-Scl-CreERT mice44 (which were obtained from Dr. Joachim R Göthert).

Bone marrow (BM) transplantation

Please see full details in Supplemental Note.

Colony-forming assays

LT-HSCs (Lineage-negative CD150+ CD48− c-Kit+ Sca1+DAPI− ) were FACS-sorted from the BM of Mx1-cre WT, Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/WT, Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/fl mice and seeded at a density of 100 cells/replicate into cytokine-supplemented methylcellulose medium (Methocult M3434; STEMCELL Technologies). Colonies propagated in culture were scored at day 7. The remaining cells were resuspended and counted, and a portion was taken for replating (100 cells/replicate).

LZTR1 cDNA expression experiments

Please see full details in Supplemental Note.

Development of custom anti-mouse Zrsr2 antibody

The rabbit polyclonal antibody against Zrsr2 was generated by rabbit injections (YenZym, Cys-C-Ahx-PEQEEPPQQESQSQPQPQPQSDP – amide; Cysteine (C) is assigned for single-point, site-directed conjugation to carrier protein. Ahx is added as a linker/spacer) followed by affinity purification using standard protocols.

Antibodies, FACS, and Western blot analysis

All FACS antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen, eBioscience, or BioLegend. BM mononuclear cells were stained with a lineage cocktail comprised of antibodies targeting CD3, CD4, CD8, B220, CD19, NK1.1, Gr-1, CD11b, Ter119, and IL-7Rα. Cells were also stained with antibodies against c-Kit, Sca1, CD150, and CD48. Cell populations were analyzed using an LSR Fortessa (Becton Dickinson) and sorted with a FACSAria II instrument (Becton Dickinson). We used the following antibodies: B220-APCCy7 (clone: RA3-6B2; BioLegend; catalog #: 103224; dilution: 1:200); B220-Percpcy5.5 (RA3-6B2; eBioscience; 45-0452-82; 1:200); CD3-PEcy7 (17A2; BioLegend; 100220; 1:200); CD3-APCCy7 (17A2; BioLegend; 100222; 1:200); Gr1-APC (RB6-8C5; eBioscience; 25-5931-82; 1:500); CD11b-FITC (M1/70; Biolegend; 101206; 1:200); CD11b-APCCy7 (M1/70; BioLegend; 101226; 1:200); NK1.1-APCCy7 (PK136; BioLegend; 108724; 1:200); Ter119-APCCy7 (Ter119, BioLegend; 116223: 1:200); cKit-APC (2B8; BioLegend; 105812; 1:100); cKit-PerCPCy5.5 (2B8; BioLegend; 105824; 1:100); cKit-Bv605 (ACK2; BioLegend; 135120; 1:100); Sca1-PECy7 (D7; BioLegend; 108102; 1:100); CD45.1-FITC (A20; BioLegend; 110706; 1:200); CD45.1-PerCPCy5.5 (A20; BioLegend; 110728; 1:200); CD45.1-Bv711 (A20; BioLegend; 110739; 1:200); CD45.1-APC (A20; BioLegend; 110714; 1:200); CD45.2-PE (104; eBioscience; 12-0454-82; 1:200); CD45.2-Alexa700 (104; BioLegend; 109822; 1:200); CD45.2-Bv605 (104; BioLegend;109841; 1:200); CD48-PerCPCy5.5 (HM48-1; BioLegend; 103422; 1:100); CD150-PE (9D1; eBioscience; 12-1501-82; 1:100); CD127 (IL-7Rα)-APCCy7 (A7R34; BioLegend; 135040; 1:200); CD8-APCCy7 (53-6.7; BioLegend; 100714; 1:200); CD19-APCCy7 (6D5; BioLegend; 115529; 1:200); IgM-PE (II/41; eBioscience; 12-5790-82; 1:200); IgD-FITC (11-26c.2a; BioLegend; 405704; 1:200); CD135-APC (A2F10; BioLegend; 135310; 1:200); CD4-APCCy7 (GK1.5 BioLegend; 100413; 1:200); CD25-BV711 (PC61.5; BioLegend; 102049; 1:200); CD44-APC (IM7; Biolegend; 103012; 1:200); D43 (eBioR2/60, eBioscience; 11-0431-85, 1:200); CD24-BV605 (M1/69; BD Biosciences; 563060; 1:200); CD21/35-PE (4E3; eBioscience; 12-0212-82; 1:200); CD93-APC (AA4.1; eBioscience; 17-5892-82; 1:200); CD23-e450 (B3B4; BD Biosciences; 48-0232-82; 1:200) CD16/CD32 (FcγRII/III)-Alexa700 (93; eBioscience; 56-0161-82; 1:100); CD34-FITC (RAM34; BD Biosciences; 553731; 1:50); CD34-PerCP (8G12; BD Biosciences; 345803; 1:50); CD117-PECy7 (104D2; eBioscience; 25-1178-42; 1:100); CD45-APC-H7 (2D1; BD Biosciences; 560178; 1:200); Ly-51-PE (BP-1; BD Bioscience; 553735; 1:200).

The composition of immature and mature hematopoietic cell lineages in the bone marrow, spleen, and peripheral blood was assessed using a combination of antibodies against B220 (RA3-6B2), CD19 (1D3), CD3 (17A2), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8a (53-6.7), CD11b (M1/70), CD25 (PC61.5), CD44 (IM7), Gr-1, IgM (Il/41), IgD (11-26c.2a), CD43 (S11), CD24 (M1/69), Ly-51 (BP-1), CD21/35 (4E3), CD93 (AA4.1), CD23 (B3B4), c-Kit (2B8), Sca-1 (D7), CD127 (A7R34) and CD135 (A2F10).

The following antibodies were used for Western Blot: Zrsr2 (custom, Yenzym, 1:1000), LZTR1 (sc-390166 or sc-390166 X, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000), RIT1 (ab53720, Abcam, 1:1000), pan-RAS antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA1-012X, 1:1000), FLAG (F-1084, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:1000), UPF1 (ab109363, Abcam, 1:1000), and Actin (A-5441, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:4000).

Cell cycle and apoptosis analyses

Please see full details in Supplemental Note.

Histological and peripheral blood analysis

Please see full details in Supplemental Note.

Cell lines and tissue culture

HEK293T cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and grown in DMEM/10% FCS. Ba/F3 and 32Dcl3 cells were grown in RPMI/10%FCS with 1 ng/ml murine IL-3 (PeproTech; 213-13) unless noted otherwise. TF-1 cells were grown in RPMI/10%FCS with 2 ng/ml recombinant human GM-CSF (R&D Systems; 215-GM) unless noted otherwise. K562 cells were cultured in RPMI/10% FCS. Human fibroblast cells were from Dr. Frank’s McCormick laboratory and cultured in DMEM/20%FCS. All cell culture media included penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

Transformation of primary human fibroblasts

Please see full details in Supplemental Note.

In vitro competition assay

Please see full details in Supplemental Note.

CRISPR screening for ZRSR2-regulated U12-type introns

Ba/F3, 32D, and TF1 cells were transduced with LentiCas9-Blast (Addgene; #52962) and single-cell sorted into 96-well plates. Among these clones, we used a single clone with strong Cas9 expression. sgRNA library of NMD targets in LZTR1 mutated cells were amplified and packaged as lentivirus. Functional virus titer was obtained by measuring puromycin (2 µg/ml) resistance after transduction, as previously published45. A titer resulting in 30% of cells surviving puromycin selection was calculated. For the NMD library screen which includes 2,600 sgRNAs, triplicate transductions with 8.7 × 106 cells each were infected for coverage of approximately 1,000X representation. The library includes 4 sgRNAs against each target gene (602 human genes for TF-1-Cas9 and 594 mouse genes for Ba/F3-Cas9 and 32D-Cas9), 100 control sgRNAs, and positive control sgRNAs against Pten for Ba/F3-Cas9 and 32D-Cas9, and NF1 for TF-1-Cas9 cells were transduced with lentivirus carrying sgRNA library produced by 293FT cells and puromycin selection (2 µg/ml) was performed in IL-3 or GM-CSF containing media for 7 days. Then, we washed out IL-3 or GM-CSF (Day 0) and surviving cells were harvested at 7 days after cytokine depletion (Day 7). Cell Pellets were lysed and genomic DNA extracted (Qiagen) and quantified by Qubit (ThermoScientific). A quantity of gDNA covering 1,000X representation of gRNAs was PCR amplified using Q5 high-fidelity polymerase (NEB cat# M0491) to add Illumina adapters and multiplexing barcodes. Amplicons were quantified by Qubit and Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 2500. Sequencing reads were aligned to the screened library and counts were obtained for each gRNA. We used standard methods from the R/Bioconductor package and the specific package was edgeR. For the probe level analysis, we used the standard workflow with glmLRT option for the model fitting/statistical test. For gene level analysis we used the camera analysis function, also from edgeR, as previously described 46,47.

CRISPR-directed mutations

Cas9 expressing K562 and Ba/F3 cells were transduced with iLenti-guide-GFP vector targeting LZTR1/Lztr1 exonic and intronic sequences in which sgRNA expression was linked to GFP expression. For the in vivo competition assay, the percentage of GFP-expressing cells was then measured over time after infection using BD LSRFortessa. The GFP-positive rates in living cells at each point normalized to those of day 2 after the lentiviral transduction were calculated. For RT-PCR and Western blot analysis, sgRNA-transduced cell lines were single-cell-sorted into 96-well plates using a BD FACSAria III cell sorter to generate single-clone-derived cells. The target sequences of sgRNA used to induce LZTR1 protein coding mutations as well as intron 18 mutations in LZTR1/Lztr1 are located in Supplementary Table 10. For colony formation assay to evaluate the in vitro effect of Lztr1 intron 18 mutation, lineage-negative hematopoietic precursors from Scl-CreERT Rosa26-Lox-STOP-Lox Cas9-EGFP were transduced with pLKO RFP657 vector (Addgene; #57824) targeting intron 18 of Lztr1 using RetroNectin (T100A, Takara Bio) as described above. GFP+/RFP657+ double-positive cells were purified for plating using BD FACSAria™ III cell sorter, followed by serial replating in vitro. The transduced cells were seeded at a density of 1000 cells/replicate into cytokine-supplemented methylcellulose medium (Methocult M3434; STEMCELL Technologies). Colonies propagated in culture were scored at day 7. The remaining cells were resuspended and counted, and a portion was taken for replating (1000 cells/replicate).

RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini or Micro kit (Qiagen). For cDNA synthesis, total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with Verso cDNA Kit (Thermo scientific). Resulting cDNA was diluted 10-20 fold before use. LZTR1 splice variants were detected via semiquantitative RT-PCR by standard OneTaq® DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs) PCR protocol: 95°C for 2 min, then 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 60 sec, followed by 72°C for 7 min. The bands were visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in 10μl reactions with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Roche Life Science). All qRT-PCR analysis was performed on an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 6 Flex Cycler (ThermoFisher Scientific). Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the comparative CT method and the values were corrected with expression levels internal control, GAPDH/Gapdh. Primers used in RT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 10.

mRNA isolation and analysis

Please see full details in Supplemental Note.

mRNA stability assays

For mRNA half-life measurement using qRT-PCR, K562 cells with LZTR1 intron 18 mutations were infected with anti-UPF1 shRNAs and control shRNA in pLKO.1 puro vector (Addgene; #8453). After puromycin selection (1.0 μg/ml for 7 days), the transduced K562 cells were treated with 2.5 μg/ml Actinomycin D (Life Technologies) and harvested at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 hr (using methods as described previously13). LZTR1 minor intron inclusion and 18s rRNA mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR. Additionally, K562 cells with CRISPR-mediated ZRSR2 knockout were exposed to 2.5 μg/ml Actinomycin D (Life Technologies) and 50μM of the NMD inhibitor NMDI-1448 (Millipore Cat# 5.30838.0001) and then the relative levels of the minor intron retained forms of LZTR1 and CHD4 were measured relative to 18S rRNA by qRT-PCR at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 hours following drug exposure. Primers used in RT-PCR reactions are listed in Supplementary Table 10.

LZTR1 minigene assay

The LZTR1 minigene construct was generated by inserting the DNA fragment containing the human LZTR1 genomic sequence from exon 18 to exon 19 in between the KpnI and XhoI restriction sites of pcDNA3.1(+) vector. The sequences of inserted fragments were verified by sanger sequencing. Mutagenesis of minigene constructs was performed with the Agilent QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer’s directions. Primers used in mutagenesis are listed in Supplementary Table 10. For minigene transient transfection experiments, K562 cells were seeded into a 24-well plate with culture medium 48 hours before transfection of minigene constructs in the presence of X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were collected, and RNA was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy mini kit. Extracted RNA was treated with DNase I (Ambion) to ensure complete removal of DNA. Minigene-derived and endogenous LZTR1 transcripts were analyzed by RT-PCR using specific primers (Supplementary Table 10).

eCLIP Library Preparation

eCLIP studies were performed in duplicates by Eclipse Bioinnovations Inc (San Diego, www.eclipsebio.com) according to the published single-end seCLIP protocol31 with the following modifications: 10 million K562 cells expressing either a FLAG-tagged empty vector or N-terminal FLAG-tagged ZRSR2 were UV crosslinked at 400 mJoules/cm2 with 254 nm radiation, and snap frozen. Cells were then lysed and treated with RNase I to fragment RNA as previously described. FLAG antibody (F-1084, Sigma-Aldrich) was then pre-coupled to Protein G Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher), added to lysate, and incubated overnight at 4 deg C. Prior to immunoprecipitation, 2% of the sample was taken as the paired input sample, with the remainder magnetically separated and washed with lysis buffer only. eCLIP was performed by excising the area from ~65 kDa to ~140 kDa. RNA adapter ligation, IP-western, reverse transcription, DNA adapter ligation, and PCR amplification were performed as previously described31.

Genome annotations

Genome annotations for mapping RNA-seq data to the human (NCBI GRCh37/UCSC hg19) and mouse (NCBI GRCm38/UCSC mm10) genomes were generated as previously described49. Briefly, isoform annotations from the MISO v2.0 database50 were merged with genome annotations from Ensembl release 7151 and the UCSC knownGene track52. Constitutively spliced introns were defined as those which exhibited no evidence of alternative splicing in the UCSC knownGene track52. Each intron was classified as U2- or U12-type by comparing its 5’ splice site to the U2- and U12-type consensus sequences, obtained from ref53. This classification takes advantage of the highly stereotyped consensus of U12-type 5’ splice site.

RNA-seq read mapping

RNA-seq reads were first mapped to the transcriptome annotations assembled as described above with RSEM v1.2.454, modified to invoke Bowtie v1.0.055 with the ‘-v 2’ option. Remaining unaligned reads were then mapped to the genome as well as a database of possible splice junctions, consisting of all possible combinations of 5’ and 3’ splice sites annotated for each gene, using TopHat v2.0.8b56. The resulting read alignments generated by TopHat were then merged with the output from RSEM. Reads were filtered to require that splice junction-spanning reads have a minimum overhang of 6 nt.

Differential splicing analysis

Isoform expression and intron retention was estimated as previously described49. In brief, numbers of RNA-seq reads supporting either intron excision (splice junction-spanning reads) or intron retention (reads overlapping exon-intron boundaries and reads within introns) were computed for each intron and used to estimate the fraction of mRNA for which each intron was retained (the “isoform ratio”). Significantly retained introns were defined as those which: (1) exhibited either an absolute change in retention of ≥10% or an absolute fold-change in retention of ≥2 and (2) had an associated Bayes factor ≥5 (computed using Wagenmakers’ Bayesian framework57; relevant to single-sample comparisons for mouse data) or p ≤ 0.05 (computed using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U test; relevant for group comparisons for patient cohort data), where all comparisons were restricted to samples which had least 20 informative reads (reads that distinguish between isoforms) for the intron under consideration.

Determining levels of intron retention in patient cohorts

To quantify per-sample levels of intron retention in MDS patient samples (Extended Data Fig. 5), we calculated the ratios of the numbers of significantly retained introns (U12- or U2-type) to the numbers of introns that were removed more efficiently (U12- or U2-type) relative to the median over all samples lacking spliceosomal mutations. A pseudocount proportional to the relative abundance of each intron class was added to the numerator and dominator to regularize the computation (avoid division by zero).

RNA-seq read coverage plots

Read coverage plots were created using the ggplot2 package in R (doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4). Illustrated transcript annotations are from RefSeq58, downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser59.

Sequence logo analysis

Sequence logo plots summarizing the LZTR1 mutagenesis experiments and depicting the nucleotide consensus sequences for U12-type introns that did or did not exhibit significantly increased retention in ZRSR2-mutant versus wild-type patient samples were created by generating and illustrating position weight matrices using the seqLogo and ggseqlogo (PMID 29036507) packages in Bioconductor 60,61.

Branchpoint inference

Lariats arising from U12-type intron splicing were computationally inferred as previously described32. In brief, a split read alignment to a database of 5’ splice sites and upstream 3’ splice site sequences was performed to identify reads that spanned the lariat 2’-5’ linkage. High-confidence reads, defined as containing a single nucleotide mismatch at the split read junction, were used to identify the branchpoint location. This genome-wide branchpoint annotation was expanded in this study through the inclusion of all available TCGA RNA-seq datasets from both normal and tumor samples, with a focus on identifying branchpoints within U12-type introns. This larger branchpoint annotation was used to identify sequence features correlated with response to ZRSR2-inactivating mutations.

Data Availability Statement

Genome annotations for human and mouse were from NCBI GRCh37/UCSC hg19 and NCBI GRCm38/UCSC mm10 respectively. Isoform annotations were from the MISO v2.0 database50 and were merged with genome annotations from Ensembl release 7151 and the UCSC knownGene track52. RNA-seq reads for the human samples reported in Madan et al were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE63816). RNA-seq data generated by TCGA (dbGaP accession phs000178.v11.p8) and the Beat AML data (dbGaP accession phs001657.v1.p1) were downloaded from the National Cancer Institute Genomic Data Commons. Branchpoint-related data were obtained from a published study (PMID 29666160). RNA-seq data generated as part of this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (mouse data: accession GSE149455) and the human RNA-seq data are deposited in dbGaP phs002212.v1.p1.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Generation and validation of Zrsr2 conditional knockout (cKO) mice.

(a) Punnett square enumerating male and female myeloid neoplasm patients wild-type versus mutant for ZRSR2 across 2,302 patients. (b) Lollipop diagram of ZRSR2 mutations from (a). (c) Schematic depiction of the targeting strategy to generate Zrsr2 cKO mice. The Zrsr2 allele was deleted by targeting exon 4 in a manner that results in a frameshift following excision. Two LoxP sites flanking exon 4 and an Frt-flanked neomycin selection cassette were inserted in the downstream intron. (d) Verification of correct homologous recombination using Southern blots from targeted embryonic stem cells. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. (e) Verification of the presence of Mx1-cre and Zrsr2 floxed alleles as well as excision of Zrsr2 using genomic PCR. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (f) Full-length Western blot of Zrsr2 protein in protein lysates from bone marrow mononuclear cells from Mx1-cre control or Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y mice. Black arrow indicates full-length Zrsr2 protein while grey arrows indicate non-specific bands. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (g) Zrsr2 expression (relative to 18s rRNA) in long-term hematopoietic stem cells (DAPI− lineage-negative c-Kit+ Sca-1+ CD150+ CD48−) in Mx1-cre control, Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y, and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/fl mice 6-weeks following polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (pIpC) administration. Mean values ± SD. P-values calculated relative to the control group by a two-sided t-test. n=3 biologically independent experiments. (h) RNA-seq coverage plots from lineage-negative c-Kit+ cells from mice in (g) illustrating excision of exon 4 of Zrsr2 following pIpC.

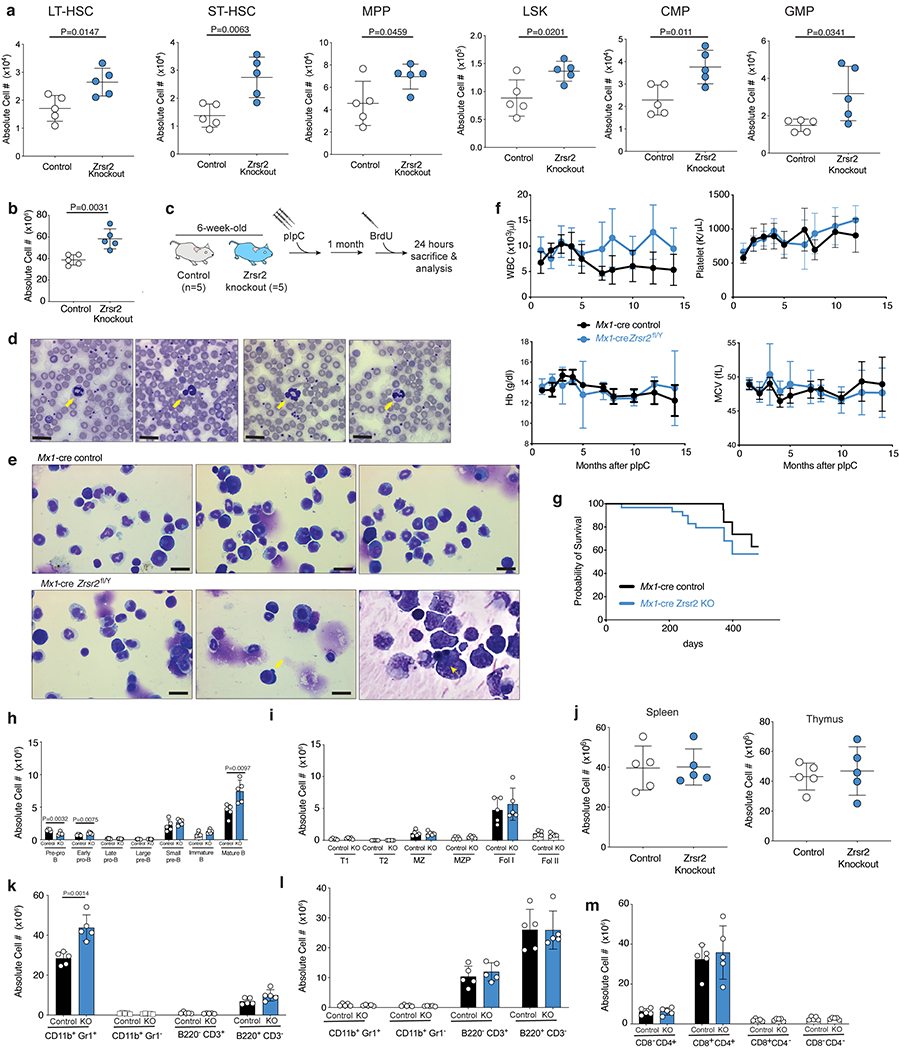

Extended Data Fig. 2. Zrsr2 loss enhances self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

(a) FACS of cells from 5th methylcellulose plating (see Fig. 1b) for live, LSK cells. Wild-type bone marrow (BM) from 6-week old mouse (left) as a staining control. (b) Number of CFU-GM, CFU-GEMM, and BFU-E colonies from initial plating of LT-HSCs (lin− LSK CD150+ CD48−) from Mx1-cre control, Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y, and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/fl mice into methylcellulose. Mean ± SD, two-sided t-test. n=4 biologically independent experiments. (c) Schematic of competitive BM transplantation. (d) Number of methylcellulose colonies from LT-HSCs from Mx1-cre control, Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/x, Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y, and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/fl. Mean value ± SD. n=3 biologically independent experiments. (e) Box-and-whisker plots of percentage of peripheral blood CD45.2+ cells in competitive transplantation pre- and post-pIpC using CD45.2+ Mx1-cre control, Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/x, Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y, and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/fl mice. For box and whiskers plots throughout, bar indicates median, box edges first and third quartile values, and whisker edges minimum and maximum values, two-sided t-test. Experiment repeated three times with similar results in (d) and (e). (f) Percentage of CD45.2+ B220+ (left), CD45.2+ CD11b+ Gr1− (middle), and CD45.2+ CD3+ cells (right) in primary competitive transplantation. Mean ± SD. P values by two-sided t-test using the values at 16 weeks after transplant. P value relative to the control group at 16 weeks by a two-sided t-test. (g) FACS analysis and gating strategy of BM cells from representative primary recipient mice in competitive transplantation. (h) Box-and-whisker plots of numbers of ST-HSCs, CMPs, MEPs, and pDCs in BM of primary recipient mice in competitive transplantation. For box and whiskers plots throughout, bar indicates median, box edges first and third quartile values, and whisker edges minimum and maximum values. P value relative to control by a two-sided t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Characterization of Zrsr2 conditional knockout (cKO) mice.

(a) Absolute number of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, MPPs, LSKs, CMPs, and GMPs in primary, non-transplanted 20-week-old Mx1-cre control (“control”) and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y mice. Mean ± SD. n=5 animals. (b) Absolute number of live, bone marrow (BM) mononuclear cells in 10-week old Mx1-cre control (“control”) and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y mice (“Zrsr2 knockout”) 4-weeks following Zrsr2 excision. Mean ± SD. n=5 animals. P-values relative to control by two-sided t-test and indicated in figures. (c) Schematic of BrdU analysis of hematopoietic stem cells from mice in (b) and Fig. 1f. (d) Hyposegmented, hypogranular neutrophils in peripheral blood of 10-week old Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y mice (yellow arrows). Bar: 10mm. (e) BM cytospins indicating hyposegmented, hypogranular neutrophils (left panel) and dysplastic erythroid progenitors (middle and right panels, yellow arrows). Bar: 10mm. Experiment repeated three times with similar results in (d) and (e). (f) Peripheral blood white blood cell counts (WBC), platelet count, hemoglobin (Hb), and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) in primary Mx1-cre control (n=9) and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y (n=10) mice (following Zrsr2 excision at 6 weeks age). Mean ± SD. (g) Kaplan-Meier survival of primary control and Zrsr2 KO mice (following Zrsr2 excision at 6 weeks age). Absolute numbers of (h) bone marrow and (i) spleen B-cell subsets. (j) Numbers of live, spleen (left) and thymic (right) mononuclear cells in mice from (h)-(i). Mean ± SD. Absolute numbers of live mature hematopoietic cells (k) in marrow and (l) spleen of 8-week-old Mx1-cre control (“control”) and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y (“knockout” or “KO”) mice (Zrsr2 excision at 4 weeks). (m) Absolute numbers of T-cell subsets in thymus of mice from (k). Mean ± SD shown throughout. Mx1-cre control (n=5) and Mx1-cre Zrsr2fl/y (n=5) mice were used in (h) to (m). P-values relative to control by two-sided t-test and indicated in figures.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Comparison of the effects of Zrsr2 loss versus Tet2 knockout or Sf3b1K700E or Srsrf2P95H mutations on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

(a) Schema of competitive bone marrow (BM) transplantation assays. (b) Absolute number of CD45.2+ long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs), LSK, and MPPs in the bone marrow of CD45.1 recipient mice 16 weeks following pIpC (n=8-10 each). For box and whiskers plots throughout, bar indicates median, box edges first and third quartile values, and whisker edges minimum and maximum values. (c) Percentage of CD45.2+ LT-HSCs, LSK, CMP, MEP, and GMP cells in the BM of CD45.1 recipient mice 16-weeks following pIpC (n=8-10 per each). P value was calculated relative to the control group by a two-sided t-test. (d) Representative FACS plots of data in (c). (e) Number of methylcellulose colonies generated from 100 sorted LT-HSCs from mice with the indicated genotype. n=3 biologically independent experiments. Error bars, mean values +/− SEM. P-values by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (f) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the blood of recipient mice from Zrsr2 knockout/Sf3b1K700E/WT double mutant cells and relevant controls pre- and post-pIpC administration to recipient mice (n=10 each). P-values by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Data in (b), (c), and (f) are shown as box-and-whisker plots where bar indicates median, box edges first and third quartile values, and whisker edges minimum and maximum values.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Effect of ZRSR2 loss on minor intron splicing.

(a) ZRSR2 mutations in our cohort. “MDS 05-14” are wild-type; “i-p” are ZRSR2-mutant. VAF: variant allele frequency, fs: frameshift, ptc: premature termination codon, del: deletion, ins: insertion, ms: missense mutation. (b) Comparison of U12-type intron retention in MDS samples vs. normal marrow. (c) Differential splicing of U12-type introns. Each point corresponds to a single intron, illustrating percentage of mRNAs in which intron is spliced out. Blue/red dots: introns with significantly increased/decreased retention in ZRSR2-mutant vs. WT, with absolute change ≥10% or absolute log fold-change of ≥2 with p≤0.05 (two-sided Mann-Whitney U, without adjustments for multiple comparisons). (d) Distribution of intron retention in samples with ZRSR2 mutations. Blue/red dashed lines: thresholds of −10% and 10% for differential retention; gold line: median change in intron retention. (e) As (b), and (f) as (d), for U2-type introns. (g) As (a), and (h) As (b), for Madan et al. (i) As (h), for U2-type introns. (j) As (f), for Madan et al. (k) RNA-seq coverage plots of U12-type introns averaging samples with indicated genotypes. (l) Splicing efficiencies of introns in (k) relative to normal marrow (median over n=4 normal samples). P-values: two-sided Mann-Whitney U. Middle line, hinges, notches, and whiskers: median, 25th/75th percentiles, 95% confidence interval and most extreme points within 1.5x interquartile range from hinge. (m) Expression of genes with retained U12-type introns between ZRSR2-mutant vs. WT. (n) Immunoblot in K562 cells used for eCLIP-seq (repeated twice with similar results). (o) eCLIP of ZRSR2-binding sites. Input-normalized peak signals as log2 fold-change. Purple points: eCLIP-enriched ZRSR2 peaks in biological replicates. (p) Overlap of genes bound by ZRSR2 vs. differentially spliced in ZRSR2-mutant versus WT (“ZRSR2 responsive”). P-value: Fisher’s exact test. (q) U2 snRNA binding energy within ZRSR2 non-responsive and responsive minor introns.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Consequences of ZRSR2 and LZTR1 dysregulation.

(a) RNA-seq of LZTR1’s minor intron in normal and ZRSR2-mutant and WT MDS (n=10 each) marrow. (b) Ratio of intron retained (IR) to normal LZTR1 in MDS samples (n=10 each). Mean ± SD. (c) Data from (b) ± SD. P-value; two-sided t-test. (d) Qualitative RT-PCR using primers amplifying exons 18-19 (“e18-e19”) as well as specific to IR isoform. (e) Splicing efficiencies of LZTR1 in patient samples (median over n=4 normal samples; left) or mouse lineage-negative c-Kit+ cells (right). P-values: two-sided Mann-Whitney U. (f) LZTR1 expression by level of minor intron retention (“Low”: <10%; “Mid”: 10-20%; “High-retention”: >20%). P-values: one-sided Mann-Whitney U. In (e) and (f): middle line, hinges, notches, and whiskers indicate median, 25th/75th percentiles, 95% confidence interval, and most extreme points within 1.5x interquartile range from hinge. (g) UPF1 immunoblot in K562 cells with mutation disrupting LZTR1s U12 sequence +/− anti-UPF1 shRNA. (h) Expression of U12-retained LZTR1 following actinomycin D +/− anti-UPF1 shRNA. n=3 biological replicates. Mean +/− SD. (i) Immunoblot of K562 cells +/− ZRSR2-targeting sgRNA. (j) Expression of LZTR1 (left) or CHD4 (right) isoforms in ZRSR2-null K562 cells with DMSO or NMD inhibitor (PMID 24662918). Mean +/− SD; P values: two-sided t-test. n=3 biological replicates. (k) LZTR1 minigene with mutations generated. (l) RT-PCR of LZTR1 minigene and endogenous mRNA from WT or ZRSR2-KO K562 cells. (m) RT-PCR of LZTR1 minigene and endogenous using native (“N”) or mutant minigenes. (n) Lztr1 minor intron with location of sgRNA, PAM site, 3’ U12 consequence (blue text), and sequence in individual Ba/F3 cell clones (red dash: deleted nucleotides). (o) As (n) in K562 cells. (p) Immunoblot of Lztr1 in Ba/F3 single-cell clones +/− Lztr1 protein-coding or minor intron sgRNAs. (q) Median relative percentage of GFP-labeled K562 cells following Rebastinib. Experiments in (d), (g), (i), and (l) were repeated twice with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Impaired Lztr1 minor intron splicing augments clonogenic capacity of hematopoietic precursors.

(a) Schema of experiment whereby sgRNAs targeting the conserved U12 sequence in Lztr1’s minor intron are delivered to lineage-negative hematopoietic precursors from Scl-CreERT Rosa26-Lox-STOP-Lox Cas9-EGFP Zrsr2fl/y or Zrsr2 wild-type mice followed by serial replating in vitro. In this experiment, sgRNAs are encoded from an RFP657 expressing plasmid and GFP+/RFP657+ double-positive cells were purified for plating. (b) Mean number of colonies following Lztr1 minor intron mutagenesis versus control sgRNA treated bone marrow cells in Zrsr2 wild-type or knockout background from (a). Bars represent standard deviation. P-values calculated relative to the control group by a two-sided t-test. n=3 biologically independent experiments. Error bars, mean values +/− SD. (c) Representative FACS plots of GFP% in cells just before transplantation and in peripheral blood of recipient transplanted mice 4 weeks after transplantation from Figure 5g. (d) Number of colonies in methylcellulose CFU assays from LT-HSCs from mice in (c). n=3 biologically independent experiments. Error bars, mean values +/− SD. P-values by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (e) Relative percentage of GFP-labeled K562 cells with knockout of RIT1 and/or mutagenesis of the minor intron in LZTR1 mixed with equal proportions of unlabeled cells to the BCR-ABL inhibitor imatinib. (f) Relative percentage of Ba/F3 cells treated with sgRNAs targeting Rit1 and/or the minor intron of Lztr1 following IL-3 withdrawal (median % relative to day 2 is plotted).

Extended Data Fig. 8. LZTR1 minor intron retention in cancer predisposition syndromes.

(a) Sanger sequence electropherogram of the LZTR1 intron 18 retained isoform (from a representative affected family member in Figure 6d; corresponds to the top band in the LZTR1 RT-PCR gel in Figure 5d) and LZTR1 normal spliced isoform from a control fibroblast sample (corresponds to the bottom band in the LZTR1 RT-PCR gel in Figure 6d). Red arrow indicates mutant nucleotide in the affected family members. (b) RNA-seq coverage plots of LZTR1 in fibroblasts from Noonan syndrome family and controls. Zoom in magnifies the minor intron of LZTR1. (c) As (b), but zoomed in on the region of mutation in the father. (d) As (b), but zoomed in on the region of mutation within LZTR1’s minor intron.

Extended Data Fig. 9. LZTR1 minor intron retention is pervasive in cancers.

(a) Degree of major (U2-type) intron retention across normal (N) and tumor (T) samples in cancers from TCGA. Each point corresponds to a single U2-type intron and indicates the percentage of all tumor samples in which retention of that intron exceeds the maximum corresponding retention of that intron observed in normal samples. Red dot indicates the U12-type intron of LZTR1 for comparison. (b) Each point illustrates the frequency of retention of a single intron of LZTR1 (see inset for key) across all TCGA cohorts with matched normal samples. Values along the x axes represents the mean difference in intron retention in tumor versus normal samples within a cancer type, while the y axes represent the fraction of tumor samples with intron retention that exceeds that of the normal sample with the most intron retention within a cancer type. Points represent the mean value computed across all cancer types, while whiskers represent the interquartile range across cancer types. (c) As (b), but whiskers represent the entire range.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Methods

Supplementary Table 1. Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS) patient samples used for RNA-seq, RT-PCR, and/or Western blot.

Supplementary Table 2. Differentially retained introns in wild-type and ZRSR2-mutant primary patient samples in our cohort.

Supplementary Table 3. Differentially retained introns in wild-type and ZRSR2-mutant primary patient samples in the Madan et al cohort.

Supplementary Table 4. U2- and U12-type intron splicing in LK cells isolated from WT and Zrsr2-cKO mice.

Supplementary Table 5. Human single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) using in CRISPR screen for ZRSR2-regulated nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) events.

Supplementary Table 6. Mouse single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) using in CRISPR screen for ZRSR2-regulated nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) events.

Supplementary Table 7. Gene level data from Ba/F3 cells.

Supplementary Table 8. Gene level data from 32D cells.

Supplementary Table 9. Gene level data from TF-1 cells.

Supplementary Table 10. Primer sequences for Zrsr2 floxed mice genotyping, RT-PCR, qRT-PCR, minigene assays, and sgRNAs.

Unprocessed Western Blots

Unprocessed Western Blots and/or gels

Unprocessed Western Blots and/or gels

Unprocessed Western Blots and/or gels

Unprocessed Southern and Western Blots

Unprocessed Western Blots

Unprocessed Western Blots and/or gels

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

Statistical Source Data

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS