Abstract

Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions (COPCs) are a set of painful chronic conditions characterized by high levels of co-occurrence. It has been hypothesized that COPCs co-occur in many cases because of common neurobiological vulnerabilities. In practice, most research on COPCs has focused upon a single index condition with little effort to assess comorbid painful conditions. This likely means that important phenotypic differences within a sample are obscured. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) coding system contains many diagnostic classifications that may be applied to individual COPCs, but there is currently no agreed upon set of codes for identifying and studying each of the COPCs. Here we seek to address this issue through three related projects: a) we first compile a set of ICD-10 codes from expert panels for ten common COPCs, b) we then use natural language searches of medical records to validate the presence of COPCs in association with the proposed expert codes, c) finally, we apply the resulting codes to a large administrative medical database to derive estimates of overlap between the ten conditions as a demonstration project. The codes presented can facilitate administrative database research on COPCs.

Keywords: Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions, Chronic Pain, Fibromyalgia, Database, Biomedical Research

Perspective:

This article presents a set of ICD-10 codes that researchers can use to explore the presence and overlap of Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions (COPCs) in administrative databases. This may serve as a tool for estimating samples for research,exploring comorbidities and treatments for individual COPCs, and identifying mechanisms associated with their overlap.

Introduction

The significant impact of chronic pain on the American public was highlighted in the 2011 Institute of Medicine report on Relieving Pain in America.10 This report also brought focus on to some prevalent chronic pain conditions that appear to coexist in the same individuals. Further these coexisting conditions tend to be more common in females compared to males. The concept of coexisting pain conditions has been recognized by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Pain Consortium and as an area of priority for which additional research is needed. Currently, the set of disorders identified as overlapping and potentially sharing a common mechanism include, but should not be limited to, the following conditions: temporomandibular disorders (TMD), fibromyalgia (FM), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), vulvodynia (s), myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome (UCPPS), endometriosis (ENDO), chronic tension-type headache (cTTH), migraine headache (MHA), and chronic lower back pain (cLBP). Collectively, these conditions are referred to as Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions (COPCs).13, 16

While each of the individual conditions within the set of COPCs has an associated empirical literature, few studies have been able to study the overlap of these conditions with each other.13 The few studies that have explored combinations of COPCs typically examine only one or two COPC pairings and have been limited by a lack of standardization in diagnostics when comparing pairings across studies. While the use of the electronic medical record (EMR) or other administrative databases could be informative to the study of COPCs, there is currently no standard approach to identifying these conditions in these types of databases.

The use of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes in administrative databases could serve as proxies for identifying COPCs.19 Such an approach could facilitate estimates of how often each COPC occurs within a health care system as well as the ability to begin studying mechanisms and treatment approaches addressing the overlap of these conditions. The greatest challenge to this approach however has been the fact that there is considerable variance in how clinicians code each of the COPCs.14

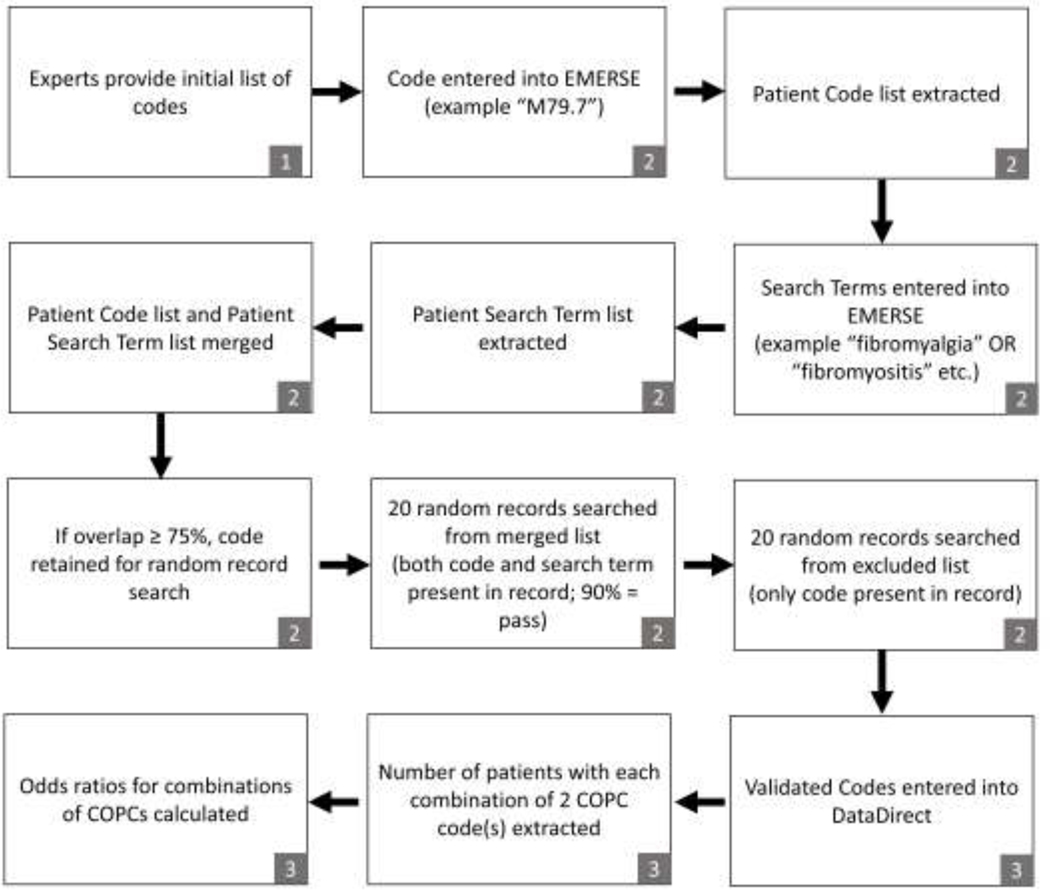

This paper seeks to provide COPC researchers with a subset of ICD-10 codes (from the universe of ICD-10 codes that could be used to define COPCs) that have the greatest likelihood of capturing the intent of identifying one or more of the COPCs in administrative databases. We conducted three related projects to achieve this goal. First, we describe the process by which diagnostic content experts identified relevant codes. Secondly, we describe and report the results of a validation project using natural language searches of medical records to validate the selected ICD-10 codes as proxies for COPCs. Finally, we provide the results of a demonstration project wherein the resulting list of ICD-10 codes were used to quantify the overlap of COPCs within a health system administrative database. The overall workflow can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Workflow for deriving and validating ICD-10 codes for COPCs. Numbers refer to study project. 1= expert panel study; 2 = validation project study; 3= demonstration project study.

Project One: The Expert Panel Study: Consensus in ICD Coding

In 2015, the NIH Pain Consortium established a task force charged with facilitating the study of COPCs. The task force agreed that diagnostic uniformity would be key to future explorations of COPCs. To this end, the task force co-chairs (WM and DAW) convened a panel of three experts for each of the 10 identified COPCs.

Methods:

Experts were selected based on a combination of criteria including publications on the relevant COPC, history of extramural funding for the COPC, and previous contributions made to the diagnostic criteria for the COPC. Table 1 displays the composition of the expert panel. Experts were initially contacted by email indicating the purpose of the project, estimated time commitment, and the proposed composition of the three-person panel. Once the panel was formed, conference calls were convened for the purpose of discussing the diagnostic criteria for the identified conditions and establishing a recommended set of ICD-10 codes that could be used to identify each of the 10 COPCs. The task was described simply as “to compile a list of ICD codes used to designate” the relevant COPC. No codes were proposed by the task force prior to or during the call, enabling each member of the expert panel to make unbiased recommendations. No upper limit was placed on the number of proposed codes. Each proposed code was recorded and all experts were offered the opportunity to dispute or amend the list. In practice, there was little to no disagreement between the experts. Following each call, a summary list of codes was provided to all participants.

Table 1.

Expert Panels

| chronic lower back pain (cLBP) |

| Michael Von Korff Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute |

| Robert D. Kerns Yale University |

| Sean Mackey Stanford University |

| endometriosis (ENDO) |

| Sawsan As-Sanie University of Michigan |

| Frank Tu NorthShore Research Institute |

| Georgine Lamvu Orland VA Medical Center |

| irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) |

| Bruce Naliboff University of California Los Angeles |

| William E. Whitehead University of North Carolina |

| Emeran Mayer University of California Los Angeles |

| temporomandibular disorder (TMD) |

| William Maixner Duke University |

| Richard Ohrbach University at Buffalo |

| Roger Fillingim University of Florida |

| urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome (UCPPS) |

| J. Quentin Clemens University of Michigan |

| Michel Pontari Temple University |

| Ursula Wesselmann University of Alabama Birmingham |

| migraine/chronic tension-type headache (MHA/cTTH) |

| Richard B. Lipton Albert Einstein College of Medicine |

| Timothy Houle Massachusetts General Hospital |

| Wade Cooper University of Michigan |

| myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) |

| Dane B. Cook University of Wisconsin Madison |

| Lucinda Bateman Bateman Horne Center |

| Andreas Kogelnik Open Medicine Institute |

| fibromyalgia (FM) |

| Daniel J Clauw University of Michigan |

| Lesley Arnold University of Cincinnati |

| Don L. Goldenberg Oregon Health Services University |

| vulvodynia (VVD) |

| Barbara Reed University of Michigan |

| Ruby Nguyen University of Minnesota |

| Christin Veasley Chronic Pain Research Alliance |

Results:

The original list of recommended ICD-10 codes generated by the panel prior to validation is reported in Supplemental Table 1 and contains a total of 134 codes. Experts recommended that the codes for TMD, MI, and cLBP be selected from previously published work. For TMD the ICD-10 codes were selected based upon the recommendations of the International Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group.15 Both MHA and cTTH codes were recommended based upon ICD-9 codes that could be translated to ICD-10 using the American Academy of Neurology crosswalk document (available at: https://www.aan.com). The cLBP panel recommended deriving a list from a previously published set of ICD-9 codes for back pain;4 these were subsequently translated to ICD-10 and supplied to our research group as part of an ongoing crosswalk development project at the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research (Lynn Debar, personal communication, August 31, 2017). In addition to single codes indicating generic back pain (e.g., M54.5, M54.89, M54.9) we also used code groups for related diagnoses such as radiculopathy (M54.1-), lumbago (M54.4-), sciatica (M54.3-), spondylosis (M47.-). Code groups were also used for migraine headache (MHA)(G43.-), (except for those codes related to cyclic vomiting or MHA due to cerebral infarction), and for endometriosis (ENDO) (N80.-). All other codes were supplied directly by the expert groups after discussion and achievement of group consensus. To identify painful ENDO, the experts recommended a combination of codes (one or more ENDO codes and one or more codes indicating dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and/or pelvic/perineal pain).

Conclusions:

The panel of experts was able to reach consensus on a set of ICD10 codes that were commonly used by clinicians when encountering patients with symptoms consistent with the COPCs. This set of codes may therefore serve as a starting point for further efforts to validate the use of ICD10 codes as proxies for COPCs and or to refine a more parsimonious sub-set of highly predictive codes for research.

Project 2: The ICD-10 Validation Study: Code Validation Using Medical Record Searches

One well-established limitation of using ICD-10 codes for research purposes is that clinicians can apply codes in a heterogeneous manner. Codes may be used to cover a variety of clinical presentations, only some of which may relate to the COPCs of interest. We therefore conducted a validation study of the proposed ICD-10 codes from the expert panel by comparing the ICD-10 codes to key search terms found within the medical record.

Methods:

This project was performed using the Electronic Medical Record Search Engine (EMERSE) a platform for free-text searches of medical records8. Use of EMERSE for this study required IRB approval given patient level data was being accessed. A list of search terms was compiled for each COPC through literature searches and Medical Subject Heading (MESH) searches. These search terms were designed to capture phrasing roughly synonymous with the COPC of interest. First, each candidate ICD-10 code was entered into the EMERSE system to identify patient medical records that contained the specified code. For this study, we used the date range 10/01/2015 – 04/01/2018 so as to capture the time period when ICD-10 was instituted through the time this study was initiated. Second, groups of search terms were entered to identify patients who had at least one of these search terms in their medical records. Finally, each patient list containing ICD-10 codes was merged with the relevant patient list containing defining search terms so as to identify a list of patients who had both the ICD-10 code and one or more of the relevant search terms in the same medical record. As an example, ICD-10 code M79.7 (FM) was used to create a list of patients with that code. Then the search terms (“fibromyalgia” OR “fibrositis” OR “fibromyalgia syndrome” OR “fibromyositis” OR “FMS” OR “diffuse myofascial pain syndrome”) were used to identify a list of patients whose medical record contained at least one of those terms. These two lists were merged and the percentage of patients with M79.7 and a relevant search term occurring simultaneously in the medical record was calculated. For purposes of this study the percentage of matches as well as the percentage of codes without supporting descriptors or the percentage of descriptors without a code could be calculated.

There are no specific ICD-10 code for “chronic low back pain” or for “endometriosis with pain” despite these being recognized as COPCs. For these two COPCs, cLBP and painful ENDO, we used “fuzzy searches,” which allowed for combinations of words that occur within a predefined word distant from one another (indicated by a “~” in combination with an integer). This allowed us to capture the relevant information even when the words did not occur in a precise order. As an example, “chronic low back pain”~6 would capture the phrase “chronic bilateral low back pain” where the precise phrase “chronic low back pain” would not. All search terms are shown in Table 1. For purposes of identifying a validated short list of ICD-10 codes for COPCs, codes were retained for further validation if 75% or more of the patients with the relevant code also had one or more relevant search terms in the same medical record.

Further Validation Using Random Record Searches

The above procedure produced two distinct lists for each COPC: (1) patients who had both the ICD-10 code and an associated search term in the same medical record, and (2) patients who had the ICD-10 code but no associated search term in the same medical record. Cases in the first group helped confirm that the code was indeed being used as intended when supported by natural language text. Cases in this group however could be false positives if the natural language was present but not referring to the patient’s diagnosis. For example, a patient could have “M79.7” with an associated diagnosis of local myofascial pain, with the term “fibromyalgia” appearing as part of a family medical history (e.g., “mother has fibromyalgia”). While not likely to be a common occurrence, we sought to reduce this type of error by estimating how often these false positives were likely to occur by searching a random sample of 20 patient records per ICD-10 code that had both the ICD-10 code(s) and one or more relevant search terms in the same medical record. A code or code group was considered acceptable if 18 or more (90%) of the searched records indicated that the search term was directly associated with the ICD-10 code.

We also searched a random sample of 20 patient records from the patient list that contained each ICD-10 code but not an associated search term. This was to determine how often false negatives occurred. The purpose of this search was to confirm that a relevant ICD-10 search term was not associated with the ICD-10 code. We did not establish any a priori cutoff for false negatives.

Results:

The codes that remained after the validation procedures are shown in Table 2 with the associated search terms, percentage captured by the EMERSE free text search, percentage of true positives for each COPC code group, and percentage of false negatives for each COPC code group. The validation process helped to reduce the number of ICD-10 codes from 134 to 37 specific codes or code groups. The percentage of patients captured by EMERSE free text searches was very high for almost all of the included codes, typically greater than 95%. cLBP was a notable exception, with the included codes ranging from 75.6% to 88.9%. The eliminated codes are shown in Supplemental Table 2 with the same statistics. For each COPC, at least one code or code group met our validation criteria.

Table 2.

Validated codes, and validation performance metrics for each COPC.

| COPC/Search terms | ICD-10 Code | N with code | N captured by search terms, % | True Positive, % | False Negative, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibromyalgia | M79.7 | 8401 | 8263, 98.4% | 19/20 95% | 0/200% |

| • Fibromyalgia • fibrositis • fibromyalgia syndrome fibromyositis • FMS • diffuse myofascial pain syndrome | |||||

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome | K58.0 | 5551 | 5551, 100% | 20/20 100% | 0/110% |

| • irritable bowel syndrome • irritable bowel • irritable colon • IBS • mucous colitis • spastic colon • nervous colon |

K58.1 | 1350 | 1350, 100% | ||

| K58.2 | 1459 | 1459, 100% | |||

| K58.8 | 239 | 239, 100% | |||

| K58.9 | 9828 | 9817, 99.9% | |||

| Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome | N30.10 | 2111 | 2110, 99.9% | 19/20 95% | 0/10% |

| • interstitial cystitis • bladder pain syndrome • painful bladder syndrome • IC/BPS • IC/PBS • (“chronic pelvic pain” AND “urinary symptoms”) |

N30.30 | 23 | 23, 100% | ||

| Chronic Prostatitis | N41.1 | 310 | 308, | 19/20 | 0/2 |

| • chronic prostatitis • inflammatory prostatitis • (“chronic” AND “prostatitis”) OR (“prostatitis” AND “unspecified”) |

99.3% | 95% | 0% | ||

| Vulvodynia | N94.810 | 184 | 184, 100% | 18/20, 90% | 0/1, 0% |

| • Vulvodynia • Vestibulodynia • vulvar vestibulitis • vulvitis • vulvar discomfort |

N94.818 | 1872 | 1871, 99.9% | ||

| N94.819 | 76 | 76, 100% | |||

| Migraine | G43.XXX (exclude G43.6- [cerebral infarct] and G43.A- / [cyclical vomiting] | 34604 | 34,567, 99.9% | 20/20, 100% | 0/20, 0% |

| • Migraine • Migraines • sick headache • chronic daily headache • status migrainosus | |||||

| Chronic tension-type headache | G44.201 | 168 | 168, 100% | 20/20, 100% | 1/20, 5% |

| • tension headache • tension type headache • stress headache • tension-vascular headache | |||||

| G44.209 | 2873 | 2835, 98.6% | |||

| G44.211 | 42 | 42, 100% | |||

| G44.219 | 809 | 808, 99.9% | |||

| G44.221 | 447 | 446, 99.8% | |||

| G44.229 | 1274 | 1272, 99.8% | |||

| Temporomandibular disorder | M26.60 | 1293 | 1265, 97.8% | 18/20, 90% | 9/20, 45% |

| • temporomandibular disorder • TMD • temporomandibular joint disorder • TMJD • temporomandibular joint disease • ((“temporomandibular” AND (“disease” OR “disorder”)) • TMJ syndrome • TMJ arthralgia • TMJ tenderness • TMJ pain • TMJ disease • TMJ dysfunction • temporomandibular joint syndrome |

M26.62 | 1474 | 1462, 99.9% | ||

| M26.63 | 616 | 614, 99.7% | |||

| S03.0XXA | 326 | 293, 89.8% | |||

| Chronic low back pain | M54.5 | 43,850 | 33,169, 75.6% | 19/20, 95% | 8/20, 40% |

| • back pain chronic~6 • back pain persistent~6 • back pain recurrent~6 • back pain unspecified~6 • back pain nonspecific~6 • back pain idiopathic~6 • back pain functional~6 |

M54.40, 41, 42 | 10649 | 9470, 88.9% | ||

| M54.89 | 804 | 644, 80.1% | |||

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | R53.82 | 8917 | 8916, 99.9% | 20/20, 100% | 0/1, 0% |

| • chronic fatigue • chronic fatigue syndrome • myalgic encephalomyelitis • CFS • ME/CFS • systemic exertion intolerance disease • SEID | |||||

| Endometriosis With pain | N80.XXX AND | 1586 | 1561, 98.4% | 18/20, 90% | 6/20, 30% |

| • endometriosis pain~4 • endometriosis painful~4 • endometrioma pain~4 • endometrioma painful~4 • adenomyosis pain~4 • adenomyosis painful~4 • ((“endometriosis” OR “endometrioma” OR “adenomyosis”) AND (“pelvic pain” OR “dysmenorrhea” OR “dyspareunia” OR “intercourse pain”~4 OR “intercourse painful”~4)) |

(“R10.2” OR “N94.4” OR “N94.5” OR “N94.6” OR “N94.10 “ OR “N94.11 “ OR “N94.12 “ OR “N94.19 “) |

Conclusions:

There are ICD-10 codes that are closely associated with essential descriptors of each of the ten COPCs. This suggests that some codes can be used as reasonable proxies for COPCs, but with several notable limitations discussed in detail in the overall Discussion section.

Project 3: Demonstration Project: Using the Sub-Set of ICD-10 Codes to Explore COPCs in a Health System Administrative Database

The purpose of the demonstration project was to estimate overlap between the COPCs as defined by the ICD-10 codes resulting from the ICD-10 COPC validation project.

Methods:

Data Direct.11

Data Direct is a self-service online resource enabling access to a structured database within a clinical research data warehouse containing diagnoses, encounters, procedures, medications (ordered and administered), and labs (ordered and results) on more than 3 million unique patients from across Michigan Medicine at the University of Michigan. For this project, the Cohort Discovery Mode was used, which provides aggregate level data only, includes no protected health information or unique patient level data, and requires no Institutional Review Board approval. Queries in Data Direct were limited to the ICD-10 codes identified through the Validation Study, and three additional control group codes for chronic conditions not considered to be COPCs. These control conditions were B18.2 (chronic viral hepatitis C; CVH), J44.9 (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified; COPD), and E11.40 (Type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic neuropathy, unspecified; DN). Our purpose for including these non-COPC diagnostic groups was to compare the degree of overlap among COPCs with other chronic medical conditions having comparable rates of contact within the medical system.

Filters.

Data Direct includes filter options that allows users to narrow the patient population. We used basic demographic filters excluding individuals who were deceased and of unknown gender. Data was restricted to encounters that occurred between 10/01/2015, when ICD-10 codes were fully implemented at Michigan Medicine, and 04/01/2018, in patients 18 years or older. Encounters were restricted to ‘inpatient,’ ‘outpatient,’ and ‘emergency,’ which excluded the ‘Other (Preadmit, Cancelled, Unknown, etc.)’ categories.

Queries.

With the above filters in place, the available sample of patients was 687,589 (56.7% female) patients. We then filtered this sample for the sub-set of ICD-10 codes identified in the Validation study displayed in Table 2. Data Direct allows for ‘AND,’ ‘OR’ and ‘NOT’ programming logic. Counts beneath 10 were not displayed by Data Direct to discourage identification of individual patients. These logic operators were used to construct the following:

To determine the total number of patients associated with each of the ICD-10 code groups, we sequentially added each code from a COPC group to a ‘diagnosis’ filter using ‘inclusion/OR’ logic.

To determine the number of patients associated with all combinations of two COPCs we applied the diagnostic filters for an individual COPC with all other COPC diagnostic filters using ‘AND’ logic.

In addition to reporting raw numbers, we calculated odds ratios for each combination of two COPCs. When one of the COPCs was specific to females (i.e., VVD or ENDO) we used only female patients in the other COPCs of interest. We also calculated raw overlap and odds ratios for the three chronic non-COPC conditions with each of the COPCs.

Results:

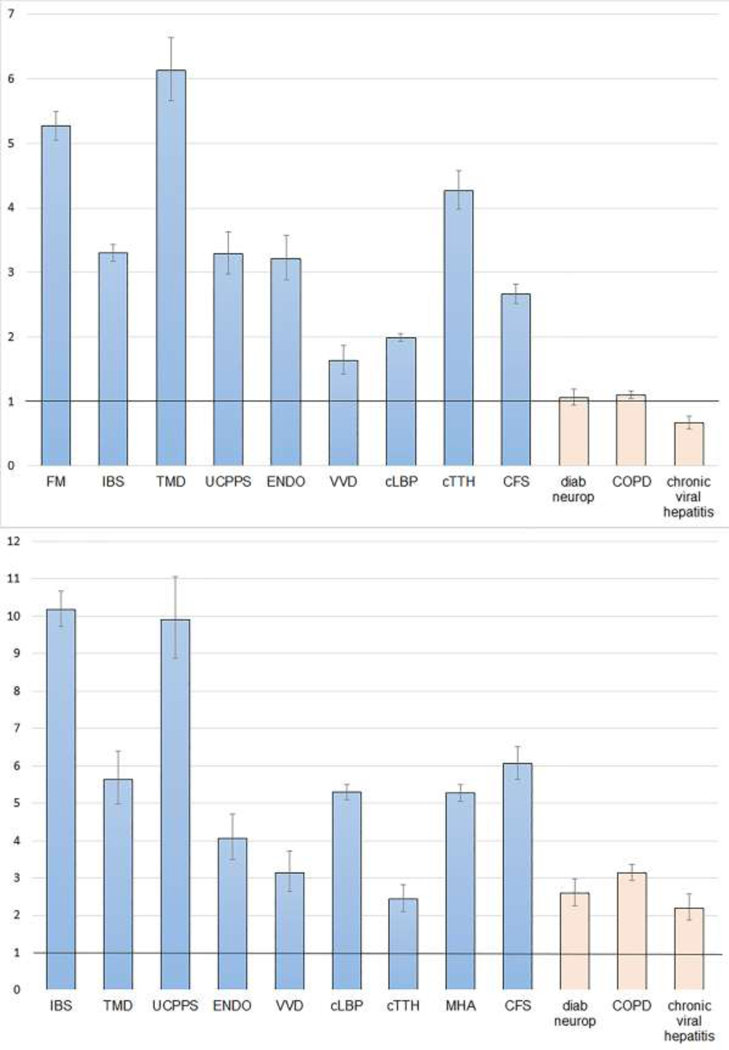

Based upon ICD-10 coding, the total number of patients with a given COPC code ranged from 1,750 (VVD) to 53,983 (cLBP). See Table 3 for counts of each COPC and for each paired combination of COPCs. Figure 2 displays odds ratios (ORs) for FM and MHA with other COPCs and non-COPCs as an example of how these data can be presented.

Table 3.

Total counts (number of patients) for each COPC by ICD-10 code group in Data Direct between 10/01/2015 (ICD-10 initiation date) and 04/01/2018. Italics represent non-COPC conditions.

| FM | IBS | TMD | UCPPS | ENDO | VVD | cLBP | cTTH | MHA | ME/CFS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 12122 | 19275 | 3019 | 2620 | 1811 | 1750 | 53983 | 4655 | 43470 | 9325 |

| Female | 11149 | 15041 | 2435 | 2170 | 1811 | 1750 | 32702 | 3283 | 34900 | 6594 |

| FM | 2497 | 273 | 386 | 191 | 147 | 3624 | 193 | 3046 | 866 | |

| IBS | 2497 | 288 | 534 | 301 | 238 | 3065 | 202 | 3355 | 704 | |

| TMD | 273 | 288 | 53 | 21 | 20 | 289 | 53 | 873 | 60 | |

| UCPPS | 386 | 534 | 53 | 160 | 198 | 434 | 34 | 473 | 96 | |

| ENDO | 191 | 301 | 21 | 160 | 112 | 314 | 19 | 432 | 56 | |

| VVD | 147 | 238 | 20 | 198 | 112 | 173 | <10 | 241 | 35 | |

| cLBP | 3624 | 3065 | 289 | 434 | 314 | 173 | 1026 | 6003 | 1200 | |

| cTTH | 193 | 202 | 53 | 34 | 19 | <10 | 1026 | 1026 | 113 | |

| MHA | 3046 | 3355 | 873 | 473 | 432 | 241 | 6003 | 1026 | 1398 | |

| ME/CFS | 866 | 704 | 60 | 96 | 56 | 35 | 1200 | 113 | 1398 | |

| DN | 216 | 223 | <10 | 16 | <10 | <10 | 734 | 17 | 327 | 78 |

| COPD | 1013 | 958 | 79 | 80 | 26 | 23 | 2758 | 98 | 1388 | 347 |

| CVH | 167 | 181 | 11 | 20 | <10 | <10 | 417 | 17 | 194 | 61 |

| Total Number of Patients: | 687,589 | |||||||||

| Female Patients: | 389,992 | |||||||||

FM=fibromyalgia; IBS= irritable bowel syndrome; TMD = temporomandibular disorder; UCPPS = urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome; ENDO = endometriosis; VVD = vulvodynia; cLBP = chronic low back pain; cTTH = chronic tension type headache; MHA = migraine headache; ME/CFS = myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; DN = diabetic neuropathy; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVH = chronic viral hepatitis

Figure 2.

Odds Ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the co-occurrence of COPCs and three non-COPCs in MHA (top panel) and FM (bottom panel).

For every combination of two COPCs the Odds Ratio exceeded one, indicating that each COPC is significantly associated with the co-occurrence of other COPCs as defined by the selected ICD-10 codes. The largest OR was for the presence of UCPPS in VVD at 24.99, while the smallest OR was for TMD in cLBP at 1.24. The ORs for COPCs co-occurring generally exceeded the ORs associated with the three chronic non-COPC conditions, though this was not true for every combination of COPCs. All ORs are shown in Table 4 with color-coding for ease of interpretation. Table 5 shows the co-occurrence of each combination of two COPCs as a percentage.

Table 4.

Odds ratios for pairs of COPCs and three chronic non-COPCs with 95% confidence intervals. Colors correspond to the strength of the relationship. Light blue = moderate negative relationship. Light yellow = moderate positive relationship. Orange = strong positive relationship. Red = very strong positive relationship.

| OR | LL | UL | OR | LL | UL | OR | LL | UL | OR | LL | UL | OR | LL | UL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM | IBS | TMD | UCPPS | ENDO | |||||||||||

| FM | 10.18 | 9.72 | 10.67 | 5.64 | 4.98 | 6.40 | 9.91 | 8.88 | 11.06 | 4.06 | 3.49 | 4.72 | |||

| IBS | 10.18 | 9.72 | 10.67 | 3.70 | 3.27 | 4.18 | 9.10 | 8.27 | 10.02 | 5.05 | 4.46 | 5.72 | |||

| TMD | 5.64 | 4.98 | 6.40 | 3.70 | 3.27 | 4.18 | 4.75 | 3.61 | 6.25 | 1.87 | 1.22 | 2.89 | |||

| UCPPS | 9.91 | 8.88 | 11.06 | 9.10 | 8.27 | 10.02 | 4.75 | 3.61 | 6.25 | 18.62 | 15.74 | 22.03 | |||

| ENDO | 4.06 | 3.49 | 4.72 | 5.05 | 4.46 | 5.72 | 1.87 | 1.22 | 2.89 | 18.62 | 15.74 | 22.03 | |||

| VVD | 3.14 | 2.65 | 3.73 | 3.97 | 3.46 | 4.56 | 1.85 | 1.19 | 2.88 | 24.99 | 21.41 | 29.16 | 15.56 | 12.77 | 18.95 |

| cLBP | 5.29 | 5.09 | 5.51 | 2.29 | 2.20 | 2.39 | 1.24 | 1.10 | 1.40 | 2.34 | 2.11 | 2.60 | 2.30 | 2.04 | 2.60 |

| cTTH | 2.43 | 2.10 | 2.81 | 1.58 | 1.37 | 1.82 | 2.64 | 2.01 | 3.47 | 1.94 | 1.38 | 2.72 | 1.25 | 0.79 | 1.97 |

| MHA | 5.27 | 5.05 | 5.50 | 3.30 | 3.18 | 3.43 | 6.13 | 5.66 | 6.64 | 3.29 | 2.98 | 3.64 | 3.21 | 2.88 | 3.58 |

| CFS | 6.07 | 5.64 | 6.52 | 2.90 | 2.68 | 3.14 | 1.48 | 1.14 | 1.91 | 2.78 | 2.27 | 3.42 | 1.86 | 1.43 | 2.43 |

| DN | 2.60 | 2.27 | 2.98 | 1.66 | 1.45 | 1.90 | N/A | N/ A | N/ A | 0.86 | 0.52 | 1.40 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| COPD | 3.14 | 2.94 | 3.36 | 1.78 | 1.66 | 1.90 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 0.84 | 1.31 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.80 |

| CVH | 2.20 | 1.88 | 2.57 | 1.48 | 1.27 | 1.72 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 1.02 | 1.19 | 0.76 | 1.84 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| VVD | cLBP | cTTH | MHA | ME/CFS | |||||||||||

| FM | 3.14 | 2.65 | 3.73 | 5.29 | 5.09 | 5.51 | 2.43 | 2.10 | 2.81 | 5.27 | 5.05 | 5.50 | 6.07 | 5.64 | 6.52 |

| IBS | 3.97 | 3.46 | 4.56 | 2.29 | 2.20 | 2.39 | 1.58 | 1.37 | 1.82 | 3.30 | 3.18 | 3.43 | 2.90 | 2.68 | 3.14 |

| TMD | 1.85 | 1.19 | 2.88 | 1.24 | 1.10 | 1.40 | 2.64 | 2.01 | 3.47 | 6.13 | 5.66 | 6.64 | 1.48 | 1.14 | 1.91 |

| UCPPS | 24.99 | 21.41 | 29.16 | 2.34 | 2.11 | 2.60 | 1.94 | 1.38 | 2.72 | 3.29 | 2.98 | 3.64 | 2.78 | 2.27 | 3.42 |

| ENDO | 15.56 | 12.77 | 18.95 | 2.30 | 2.04 | 2.60 | 1.25 | 0.79 | 1.97 | 3.21 | 2.88 | 3.58 | 1.86 | 1.43 | 2.43 |

| VVD | 1.20 | 1.02 | 1.40 | N/A | N/ A | N/ A | 1.63 | 1.42 | 1.87 | 1.19 | 0.85 | 1.66 | |||

| cLBP | 1.20 | 1.02 | 1.40 | 1.26 | 1.15 | 1.39 | 1.99 | 1.93 | 2.05 | 1.75 | 1.65 | 1.86 | |||

| cTTH | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.2 6 | 1.15 | 1.39 | 4.27 | 3.98 | 4.58 | 1.82 | 1.51 | 2.20 | |||

| MHA | 1.63 | 1.42 | 1.87 | 1.99 | 1.93 | 2.05 | 4.27 | 3.98 | 4.58 | 2.67 | 2.52 | 2.83 | |||

| ME/C FS | 1.19 | 0.85 | 1.66 | 1.75 | 1.65 | 1.86 | 1.82 | 1.51 | 2.20 | 2.67 | 2.52 | 2.83 | |||

| DN | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.0 8 | 1.93 | 2.26 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.82 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.19 | 1.18 | 0.94 | 1.48 |

| COPD | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 1.92 | 1.84 | 2.00 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.87 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.17 | 1.29 | 1.16 | 1.44 |

| CVH | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.22 | 1.10 | 1.35 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.91 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.78 | 1.01 | 0.79 | 1.31 |

| 0–1 | 1–3 | 2–5 | 5+ | ||||||||||||

FM=fibromyalgia; IBS= irritable bowel syndrome; TMD = temporomandibular disorder; UCPPS = urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome; ENDO = endometriosis; VVD = vulvodynia; cLBP = chronic low back pain; cTTH = chronic tension type headache; MHA = migraine headache; ME/CFS = myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; DN = diabetic neuropathy; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVH = chronic viral hepatitis

Table 5.

Heat map showing overlap of COPCs as percentage. COPCs on the top row are index conditions. Colors correspond to the strength of the relationship.

| FM | IBS | TMD | UCPPS | ENDO | VVD | cLBP | cTTH | MHA | CFS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM | 12.95 | 9.04 | 14.73 | 10.55 | 8.40 | 6.71 | 4.15 | 7.01 | 9.29 | |

| IBS | 20.60 | 9.54 | 20.38 | 16.62 | 13.60 | 5.68 | 4.34 | 7.72 | 7.55 | |

| TMD | 2.25 | 1.49 | 2.02 | 1.16 | 1.14 | 0.54 | 1.14 | 2.01 | 0.64 | |

| UCPPS | 3.18 | 2.77 | 1.76 | 8.83 | 11.31 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 1.09 | 1.03 | |

| ENDO | 1.71 | 2.00 | 0.86 | 7.37 | 6.40 | 0.96 | 0.58 | 1.24 | 0.85 | |

| VVD | 1.32 | 1.58 | 0.82 | 9.12 | 6.18 | 0.53 | N/A | 0.69 | 0.53 | |

| cLBP | 29.90 | 15.90 | 9.57 | 16.56 | 17.34 | 9.89 | 9.71 | 13.81 | 12.87 | |

| cTTH | 1.59 | 1.05 | 1.76 | 1.30 | 1.05 | N/A | 0.83 | 2.36 | 1.21 | |

| MHA | 25.13 | 17.41 | 28.92 | 18.05 | 23.85 | 13.77 | 11.12 | 22.04 | 14.99 | |

| CFS | 7.14 | 3.65 | 1.99 | 3.66 | 3.09 | 2.00 | 2.22 | 2.43 | 3.22 | |

| DN | 1.78 | 1.16 | N/A | 0.61 | N/A | N/A | 1.36 | 0.37 | 0.75 | 0.84 |

| COPD | 8.36 | 4.97 | 2.62 | 3.05 | 1.44 | 1.31 | 5.11 | 2.11 | 3.19 | 3.72 |

| CVH | 1.38 | 0.94 | 0.36 | 0.76 | N/A | N/A | 0.77 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.65 |

| Key | 0.0–4.99% | 5.0–9.99% | 10.0–19.99% | 20+% |

FM=fibromyalgia; IBS= irritable bowel syndrome; TMD = temporomandibular disorder; UCPPS = urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome; ENDO = endometriosis; VVD = vulvodynia; cLBP = chronic low back pain; cTTH = chronic tension type headache; MHA = migraine headache; ME/CFS = myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; DN = diabetic neuropathy; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVH = chronic viral hepatitis

Conclusions:

The ten identified COPCs show substantial co-occurrence with each other. This overlap furthermore seems to exceed overlap with non-COPC conditions, suggesting that this is not simply a phenomenon due to increased contact with the health care system.

Discussion

We present here a list of ICD-10 codes derived from expert consensus and validation procedures that are appropriate for administrative database research on COPCs. We have also used these codes to assess the overlap of the COPCs in an administrative database linked to data derived from large medical system – we find that the chronic overlapping pain conditions do indeed overlap at a rate that exceeds other chronic medical conditions with comparable duration and medical encounters. Some of the largest observed odds ratios for pairs of COPCs were consistent with the existing literature where overlap of two or more COPCs was comprehensively assessed. As examples, TMD and headache,2 FM and ME/CFS,1 and VVD and UCPPS7 have been found to be highly comorbid in studies that have systematically assessed each condition. Our findings are also consistent with previous literature showing that additional COPCs are more prevalent in individuals already meeting diagnostic criteria for a chronic pain condition,17 and with conceptual models indicating common risk factors for the presence or development of many chronic pain conditions.5, 6, 9, 12, 13

The study of COPCs collectively, rather than index conditions in isolation, is in its infancy, but consensus is building that exploration of COPCs as a conceptual category is necessary to understand common mechanisms and risk factors.13, 16 Additionally, characterizing broad trends associated with single and multiple COPC diagnoses across different medical systems, including evidence of trends in practice that are either recommended or discouraged, may allow for important clinical insights. The socio-cultural context in which COPC diagnoses are made needs to be better understood. There is likely important variability in the application of codes at every level of the health care system from providers, to clinics, to hospitals, and possibly even at the state and regional level.

There were broad parallels between these findings and previous literature on the relative distribution of pain by anatomical location. cLBP and MHA were the two most common COPCs in the current analyses – this is similar to a large survey of chronic pain across Europe that found non-specific back pain, low back pain, knee pain, and headache, in order, to be the four most prevalent forms of pain by anatomical location.3 Such data further supports the validity of using administrative coding for research with COPCs.

Study Limitations:

There are several limitations to this approach. ICD codes are used in the United States in part to facilitate the billing of services and do not necessarily reflect comprehensive clinical judgment. As such they can be unreliable for characterizing individual patients. We have attempted to address this limitation of ICD-10 codes by demonstrating that language in the medical record is consistent with the intended diagnosis for the codes that made our final listing (i.e., Table 2). Thus use of this sub-set of codes offers assurances that those identified by the codes have a high likelihood of actually having one or more COPCs of interest. Despite higher variability, many of the excluded codes clearly had significant proportions of patients with the COPCs as well, so the use of the recommended codes will likely underestimate the true number of patients with the COPC in the database.

Clinician’s judgement may not reflect current classification schemes and recommendations for differential diagnosis. As an example, the updated 2016 FM criteria18 has dispensed with the requirement that no other conditions be present that might explain FM symptoms, which effectively means that FM is no longer a diagnosis of exclusion. Such a reconceptualization could therefore considerably change diagnostic patterns. ICD code use may vary between specialties and may reflect billing practices and ‘cultural’ elements within a department or clinic. These patterns can lead to additional heterogeneity in the application of ICD codes to a similar clinical presentation. This problem may be further exacerbated by the requirement that the code and search terms be part of the same medical record – patients may be seen by several clinicians in different specialties about the same symptoms. Divergent opinions captured at other visits could not be taken into account by the current strategy.

The expert panels defined the initial code set which necessarily reflected their conceptualization of COPCs. Thus some codes were not included that fell outside of the conceptualization of COPCs such as codes representing neuropathic pain or codes for medication overuse headache. Further, the lack of any longitudinal aspect of the current study means that these results should be read as an approximation of COPC co-occurrence and not an indication that specific conditions precede or cause others. Some of the COPCs may show greater overlap due to sharing both a common mechanism but also common diagnostic features. As pointed out on review, spinal/trunk pain is part of some FM diagnostic criteria and could lead to the application of a cLBP code to a patient whose symptoms are consistent with FM. This makes refining definitions of COPCs and their approximation by ICD codes all the more urgent.

cLBP was more difficult to validate than the other COPCs as reflected in the lower percentage of patients captured in the natural language search. In the case of cLBP there were a large number of possible codes for low back pain but none specifically for “chronic” low back pain. Future ICD classification schemes may benefit from including chronicity as a subtype of low back pain. ME/CFS also lacks a direct ICD-10 code. While chronic fatigue is a hallmark of ME/CFS, this may be insufficient to capture the current understanding of ME/CFS and its clinical presentation. Finally, while the other chronic non-COPCs generally co-occurred with lower frequency with COPCs than COPCs with one another, there were still many instances where the ORs exceeded one. This sort of ‘control’ may be useful when in assessing factors related to frequency of contact within a given medical system.

Future applications.

Perhaps one of the most useful applications of this code-set will be in cohort identification for large efficacy and/or network-based research on COPCs. Currently there is no ability to develop a “computable phenotype” for each of the COPCs and this code-set offers an initial foundation for such work. Further, forthcoming advances in COPC research will allow for the development of parallel assessment approaches for COPCs. As part of the NIH task force, we are preparing an interactive tool that makes use of self-report criteria for all ten of the COPC conditions based on the same process of expert consensus that produced the ICD codes. This clinical tool will feature a streamlined approach to triggering diagnostic criteria by making use of both representative symptoms, “trigger items,” and a comprehensive body map. This will significantly reduce the amount of time needed to evaluate multiple COPCs within the same individual in either research or clinical settings. This self-report tool in combination with the ICD-10 code set will permit a direct comparison of the present findings to data prospectively collected in the clinical setting which will allow refinements to our knowledge of COPCS.

In summary this study provides researchers with a set of ICD-10 codes for studying COPCs and their overlap using administrative databases. It also provides for the first time an assessment of how all 10 COPCs overlap in a large clinical sample.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

An expert panel compiled ICD-10 codes for ten chronic overlapping pain conditions

Natural language searches of medical records were used to validate these codes

An administrative database was used to quantify co-occurrence of the conditions

This set of codes is useful for administrative database research

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: This project were supported in part by Grant Number U01 DK092345-S1 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant Numbers K12 DE023574 and U01DE017018 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Grant Number P01NS045685 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and by the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the National Institute of Health (NIH) Pain Consortium. The Authors gratefully acknowledge Linda Porter (NIH) and the COPC Taskforce Working Group. Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest and no competing financial interests with this work. Dr. Williams is currently the Immediate past President of the American Pain Society; he has served as a consultant with Community Health Focus Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aaron LA, Herrell R, Ashton S, Belcourt M, Schmaling K, Goldberg J, Buchwald D. Comorbid clinical conditions in chronic fatigue. Journal of general internal medicine. 16:24–31, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballegaard V, Thede-Schmidt-Hansen P, Svensson P, Jensen R. Are headache and temporomandibular disorders related? A blinded study. Cephalalgia. 28:832–841, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. European journal of pain. 10:287–287, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Volinn E, Loeser JD. Use of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) to identify hospitalizations for mechanical low back problems in administrative databases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 17:817–825, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. Jama. 311:1547–1555, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diatchenko L, Nackley AG, Slade GD, Fillingim RB, Maixner W. Idiopathic pain disorders--pathways of vulnerability. Pain. 123:226–230, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardella B, Porru D, Nappi RE, Daccò MD, Chiesa A, Spinillo A. Interstitial cystitis is associated with vulvodynia and sexual dysfunction—A case-control study. The journal of sexual medicine. 8:1726–1734, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanauer DA. EMERSE: The Electronic Medical Record Search Engine. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2006:941–941, 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper D, Schrepf A, Clauw D. Pain mechanisms and centralized pain in temporomandibular disorders. Journal of dental research. 95:1102–1108, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IOM: Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care Education, and Reserach., The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kheterpal S: DataDirect: a self-serve tool for data retrieval. Available at: https://datadirect.med.umich.edu/

- 12.Kutch JJ, Ichesco E, Hampson JP, Labus JS, Farmer MA, Martucci KT, Ness TJ, Deutsch G, Apkarian AV, Mackey SC. Brain signature and functional impact of centralized pain: a multidisciplinary approach to the study of chronic pelvic pain (MAPP) network study. Pain. 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA, Smith SB, Slade GD. Overlapping Chronic Pain Conditions: Implications for Diagnosis and Classification. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 17:T93–T107, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quan H, Li B, Saunders LD, Parsons GA, Nilsson CI, Alibhai A, Ghali WA. Assessing validity of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health services research. 43:1424–1441, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP, List T, Svensson P, Gonzalez Y, Lobbezoo F, Michelotti A, Brooks SL, Ceusters W, Drangsholt M, Ettlin D, Gaul C, Goldberg LJ, Haythornthwaite JA, Hollender L, Jensen R, John MT, De Laat A, de Leeuw R, Maixner W, van der Meulen M, Murray GM, Nixdorf DR, Palla S, Petersson A, Pionchon P, Smith B, Visscher CM, Zakrzewska J, Dworkin SF. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Groupdagger. Journal of oral & facial pain and headache. 28:6–27, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veasley C, Clare D, Clauw DJ, Cowley T, Nguyen RHN, Reinecke P, Verron SD, Williams DA: Impact of chronic overlapping pain conditions on public health and the urgent need for safe and effective treatment: 2015 analysis and policy recommendations. . In: The Chronic Pain Research Alliance 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren JW, Langenberg P, Clauw DJ. The number of existing functional somatic syndromes (FSSs) is an important risk factor for new, different FSSs. Journal of psychosomatic research. 74:12–17, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Hauser W, Katz RL, Mease PJ, Russell AS, Russell IJ, Walitt B. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 46:319–329, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health O: ICD-10 : international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems / World Health Organization, World Health Organization, Geneva, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.