Abstract

Cases of thrombotic thrombocytopenia induced by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines have been reported recently. Herein, we describe the first case of another critical disorder, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), in a healthy individual after COVID-19 vaccination. A 43-year-old Chinese farmer developed malaise, vomiting, and persistent high fever (up to 39.7 °C) shortly after receiving the first dose of the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. The initial evaluation showed pancytopenia (neutrophil count, 0.70 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 113 g/L; platelet, 27 × 109/L), elevated triglyceride (2.43 mmol/L), and decreased fibrinogen (1.41 g/L). Further tests showed high serum ferritin levels (8140.4 μg/L), low NK cell cytotoxicity (50.13%–60.83%), and positive tests for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) DNA. Hemophagocytosis was observed in the bone marrow. Therefore, HLH was confirmed, and dexamethasone acetate (10 mg/day) was immediately prescribed without etoposide. Signs and abnormal laboratory results resolved gradually, and the patient was discharged. HLH is a life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome caused by aberrantly activated macrophages and cytotoxic T cells, which may rapidly progress to terminal multiple organ failure. In this case, HLH was induced by the COVID-19 vaccination immuno-stimulation on a chronic EBV infection background. This report indicates that it is crucial to exclude the presence of active EBV infection or other common viruses before COVID-19 vaccination.

Keywords: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, Epstein–Barr virus, Coagulopathy, COVID-19

To the editor

Cases of thrombotic thrombocytopenia induced by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines have been reported recently [1–3]. Herein, we describe the first case of another critical disorder, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), in a healthy person after COVID-19 vaccination.

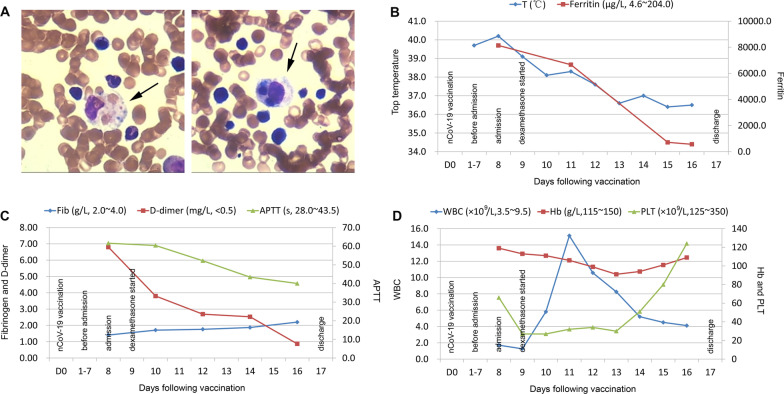

A 43-year-old Chinese female farmer developed malaise, vomiting, and a fever of 37.6 °C shortly after receiving the first dose of the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. One day later, she presented with a persistent high fever (up to 39.7 °C). Treatment with antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was ineffective. On the eighth day, the patient was admitted to our hospital. The initial evaluation showed pancytopenia (neutrophil count, 0.70 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 113 g/L; platelet, 27 × 109/L), elevated triglyceride (2.43 mmol/L), decreased fibrinogen (1.41 g/L), and increased transaminase (AST 254 U/L) and lactate dehydrogenase (1033 U/L) levels. Further tests showed a high serum ferritin level (8140.4 μg/L), low NK cell cytotoxicity (50.13%–60.83%), positive tests for Epstein–Barr virus DNA (EBV, 2.47 × 105 copy/ml in whole blood and 824 copy/ml in plasma), and negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 RNA and IgM/IgG antibodies. Hemophagocytosis was observed in the bone marrow. The results of the laboratory and imaging tests are summarized in Table 1. Therefore, HLH was confirmed based on both the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria (fulfilling six out of the eight criteria) and the HLH-probability calculator (HScore, up to 261). According to “the recommendations for the management of HLH” [4], dexamethasone acetate (10 mg/day) was immediately prescribed. The signs and abnormal laboratory results resolved gradually without the addition of a cytotoxic drug (etoposide), and the patient was discharged 17 days later (Fig. 1). The glucocorticoid dose was tapered carefully, and follow-up is still ongoing.

Table 1.

Laboratory and imaging tests on admission

| Tests on admission | Results | Normal ranges |

|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | ||

| White blood cell (109/L) | 1.26 | 3.5–9.5 |

| Neutrophil count (109/L) | 0.70 | 1.8–6.3 |

| Lymphocyte count (109/L) | 0.49 | 1.1–3.2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 113 | 130–175 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 27 | 125–350 |

| Reticulocyte count (1012/L) | 0.04 | 0.024–0.084 |

| Coagulation | ||

| APTT (s) | 61.6 | 28.0–43.5 |

| PT (s) | 13.9 | 11.0–16.0 |

| Thrombin time (s) | 39.9 | 14.0–21.0 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 1.41 | 2.0–4.0 |

| D-Dimer (mg/L) | 6.80 | < 0.5 |

| Hepatic and renal function | ||

| ALT (U/L) | 141 | 5–35 |

| AST (U/L) | 254 | 8–40 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 7.1 | 3–22 |

| Direct bilirubin (μmol/L) | 0.0 | 0–5 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 1033 | 109–245 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 27.2 | 35–50 |

| Globulin (g/L) | 27.1 | 23–32 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 2.43 | 2.5–6.1 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 54.0 | 46.0–92.0 |

| Fasting lipid | ||

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 2.43 | < 1.7 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.44 | < 5.2 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.45 | 1.29–1.55 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.05 | 2.7–3.1 |

| Lymphocyte subsets | ||

| CD4+ T cells (%) | 17.67 | 25.34–51.37 |

| CD8+ T cells (%) | 71.72 | 14.23–38.95 |

| NK cells (%) | 3.78 | 3.33–30.47 |

| NK cell cytotoxicity-granzyme (%) | 50.13% | > 78% |

| NK cell cytotoxicity-perforin (%) | 60.83% | > 84% |

| Inflammatory factors | ||

| Ferritin (μg/L) | 8140.4 | 4.6–204.0 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 10.75 | 0–5 |

| sCD25 (pg/ml) | 204.99 | 3.71–16.05 |

| IL-1β (pg/ml) | 8.21 | < 3.40 |

| IL-2 (pg/ml) | 0.76 | < 6.64 |

| IL-4 (pg/ml) | 1.67 | < 4.19 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 17.55 | < 5.30 |

| IL-8 (pg/ml) | 90.41 | < 15.71 |

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | 18.45 | < 4.91 |

| IL-12p70 (pg/ml) | 0.00 | < 10.18 |

| IL-17A (pg/ml) | 2.33 | < 4.74 |

| IL-17F (pg/ml) | 0.19 | < 4.66 |

| IL-22 (pg/ml) | 0.4 | < 3.64 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 3.96 | < 4.50 |

| TNF-β (pg/ml) | 17.63 | < 2.54 |

| INF-γ (pg/ml) | 1.86 | < 4.43 |

| Complement 3 (g/L) | 0.625 | 0.790–1.520 |

| Complement 4 (g/L) | 0.182 | 0.160–0.380 |

| Virus | ||

| Whole blood EBV DNA (copy/ml) | 2.47 × 105 | < 400.00 |

| Plasma EBV DNA (copy/ml) | 824 | < 400.00 |

| EB-VCA IgA (AU/ml) | 0.79 | < 4.00 |

| EB-VCA IgM (AU/ml) | 0.45 | < 3.00 |

| EB-VCA IgG (AU/ml) | > 50.00 | < 2.00 |

| EB-VEA IgA (AU/ml) | 0.44 | < 3.00 |

| EB-VEA IgG (AU/ml) | 0.36 | < 2.00 |

| EB-VNA IgG (AU/ml) | > 50.00 | < 2.00 |

| Whole blood CMV DNA (copy/ml) | < 400.00 | < 400.00 |

| Plasma CMV DNA (copy/ml) | < 400.00 | < 400.00 |

| SARS-CoV-2 RNA | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis C virus antibody | Negative | Negative |

| HIV antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-nuclear antibody spectrum | Negative | Negative |

| Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow | Positive | Negative |

| Superficial lymph nodes (Ultrasonography) | Negative imaging | Negative imaging |

| Color Doppler echocardiography | Negative imaging | Negative imaging |

| Chest CT scan | Negative imaging | Negative imaging |

| Abdominal CT scan | Negative imaging | Negative imaging |

| Pelvic CT scan | Negative imaging | Negative imaging |

| HLH-associated genes | Wild type | Wild type |

| HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria | 6 of the 8 criteria | Cut-off: 5 of the 8 criteria |

| HLH-probability calculator (HScore) | 261 | Cut-off: 169 |

Abnormal results are shown in BOLD

APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; PT: prothrombin time; EB-VCA: Epstein–Barr virus capsid antibody; EB-VEA: Epstein–Barr virus early antibody; EB-VNA: Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antibody; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; HLH: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; HLH-associated genes: AP3B1, ARF6, BLOC1S6, CD27, CARD11, CORO1A, CTPS1, GNLY, GZMB, IL2RG, ITK, LAMP1, LYST, MAGT1, MCM4, PRF1, PIK3CD, PRKCD, RAB27A, SH2D1A, SRGN, STX11, STK4, STXBP2, TCN2, UNC13D, CTPS1, AND XIAP

Fig. 1.

Synopsis of the clinical course. a Hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow: the arrows indicate phagocytosis of platelets and erythrocytes by a number of hemophagocytes, b Dynamic changes of the body temperature and ferritin level, c Dynamic changes of the coagulation parameters, d Dynamic changes of the blood cell counts. T: body temperature; Fib: fibrinogen; APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; WBC: white blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; PLT: platelet

HLH is a severe and life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome caused by aberrant activation of macrophages and cytotoxic T cells. It is characterized by unremitting fever, cytopenia, coagulopathy, hepatic dysfunction, and hypercytokinemia, which may rapidly progress to terminal multiple organ failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and subsequent death [5]. Without early recognition and appropriate treatment, HLH is almost always fatal. In this case, the HLH was well-controlled because of the timely management.

HLH has both primary and secondary forms. Primary HLH is mostly seen in childhood and sometimes even in the elderly with a genetic inheritance, and is caused by various mutations in at least 28 genes involved in the cytolytic pathway proteins such as PRF1, STX11, UNC13D, and STXBP2 [5, 6]. Secondary HLH is a multifactorial disease that can be secondary to infections, hematological malignancies, autoimmune diseases, organ or stem cell transplantation, medications, and most frequently, the combination of these causes. In particular, EBV is the most common trigger for HLH [5]. In this case, we analyzed the known 28 HLH-related genes by next-generation sequencing (Table 1) and did not find a disease-causing mutation. Additionally, this patient had no remarkable medical history, symptoms of acute infection, signs of tumor on the chest-abdomen-pelvis CT scan, detectable autoimmune antibodies, and recent medication intake. Moreover, although both the intracellular and extracellular EBV-DNA were positive, the serological tests (Table 1: EB-VCA IgA−, EB-VCA IgM−, EB-VCA IgG+, EB-VEA IgA−, EB-VEA IgG−, EB-VNA IgG+) indicated that the infection was not a recent event. Therefore, considering the significantly elevated CD8+ T cell proportion (71.72%), it is suggested that the HLH in this scenario was induced by acute immunostimulation of COVID-19 vaccination on a chronic EBV infection background.

To our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature to report HLH after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. Rare vaccination events are important, but do not diminish the well-documented safety profile of the inactivated vaccine against COVID-19, which has been widely administered and shows good immunogenicity, good tolerance, and high efficacy in inducing immune responses against SARS-CoV-2. In addition, this case report should not be seen as a reason to avoid vaccination, since vaccine campaigns are currently still the most promising method to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, this report indicates that it is crucial to exclude the presence of active EBV infection or other common viruses before COVID-19 vaccination. Patients with underlying conditions should be carefully monitored for any suspicious symptoms and signs following vaccination.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- HLH

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

Authors’ contributions

LVT and YH wrote the initial draft. HY revised the manuscript. LVT and YH read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Program for HUST Academic Frontier Youth Team (No. 2018QYTD14) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81973995).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Patient consented to publication of case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Liang V. Tang, Email: lancet.tang@qq.com

Yu Hu, Email: dr_huyu@126.com.

References

- 1.Muir KL, Kallam A, Koepsell SA, Gundabolu K. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2S vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2105869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greinacher A, Thiele T, Warkentin TE, Weisser K, Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayas A, Menacher M, Christ M, Behrens L, Rank A, Naumann M. Bilateral superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis, ischaemic stroke, and immune thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00872-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465–2477. doi: 10.1182/blood.2018894618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1503–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagafuji K, Nonami A, Kumano T, et al. Perforin gene mutations in adult-onset hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Haematologica. 2007;92(7):978–981. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.