Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Opioid use after surgery is associated with increased health care utilization and costs. Although some studies show that surgical patients may later become persistent opioid users, data on the association between new persistent opioid use after surgery and health care utilization and costs are lacking.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare health care utilization and costs after major inpatient or

METHODS:

The IBM MarketScan Research databases were used to identify opioid-naive patients with major inpatient or outpatient surgeries and at least 1 year of continuous enrollment before and after this index surgery. Cohorts were stratified by new persistent opioid utilization status, setting of surgery (inpatient, outpatient), and payer (commercial, Medicare, Medicaid). Patients were considered new persistent opioid users if they had at least 1 opioid claim 4-90 days after index surgery and at least 1 opioid claim 91-180 days after index surgery. Patients with opioid prescription claims between 1 year and 15 days before their index event were excluded. Health care utilization and costs (excluding index surgery) were measured in the 1-year period after surgery. Predicted costs and cost ratios were estimated using multivariable log-linked gamma-family generalized linear models.

RESULTS:

In the inpatient cohorts, 827,583 commercial, 186,154 Medicare, and 104,734 Medicaid patients were included in the study, and the incidence of new persistent opioid use in these cohorts was 4.1%, 5.6%, and 7.1%, respectively. In the outpatient cohorts, 1,542,565 commercial, 390,876 Medicare, and 94,878 Medicaid patients were selected, with 2.0%, 1.5%, and 6.4% new persistent opioid use, respectively. Across all 3 payers in both surgical settings, patients with new persistent opioid use had a higher comorbidity burden and more use of concomitant medications in the baseline period. In the 1-year period after index surgery, patients with new persistent opioid use had more inpatient admissions, emergency department visits, and ambulance/paramedic service use than patients without persistent use, regardless of payer and setting. Patients with new persistent opioid use had approximately 5 times more opioid prescriptions and also had more nonopioid pharmacy claims than those without persistent use across all cohorts. After covariate adjustment, predicted 1-year total health care costs were significantly higher for patients with new persistent opioid use compared with those without persistent use for all comparisons (commercial inpatient: $29,499 vs. $11,798; Medicare inpatient: $34,455 vs. $21,313; Medicaid inpatient: $14,622 vs. $6,678; commercial outpatient: $18,751 vs. $7,517; Medicare outpatient ($26,411 vs. $13,577; Medicaid outpatient: $12,381 vs. $6,784; all P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

New persistent opioid use after major surgery in opioid-naive patients is associated with increased health care utilization and costs in the year after surgery across all surgical settings and payers.

What is already known about this subject

Patients who are prescribed opioids for postoperative pain are at higher risk for new persistent opioid use than those who are not prescribed opioids.

Receipt of an opioid prescription is associated with higher health care utilization and costs; however, the economic impact of new persistent opioid use after surgery among opioid-naive patients has not been studied adequately.

Opioid use and misuse is common across all major payer types (commercial, Medicare, Medicaid).

What this study adds

Although new persistent opioid use and associated costs have been previously demonstrated for various specific surgery types, this study shows that the effect of persistent use on costs may be generalizable to all major surgeries across all 3 major payer types.

This study showed that previously opioid-naive patients with new persistent opioid use after a major surgical procedure had higher adjusted health care utilization and costs in the year following their surgery than those who did not have persistent use, regardless of payer.

Adjusted all-cause health care costs were 1.62- to 2.50-fold higher for patients with new persistent use than for those without, with incremental costs between $5,598 and $17,702, depending on payer and surgical setting. outpatient surgery among opioid-naive patients who had new persistent opioid use after surgery versus those who did not become new persistent opioid users after surgery.

Opioids are widely prescribed across the United States to treat postoperative pain; however, chronic opioid use can lead to increased health care utilization and costs across all major insurance payer types (commercial, Medicare, Medicaid).1-4 Previous work estimates that patients with chronic opioid use have 4 times higher mean total health care costs versus nonopioid users in the year after opioid initiation and have significantly more ambulatory visits, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospitalizations than their nonchronic opioid use counterparts.2 Although health care utilization and costs for chronic opioid users may eventually decrease over time (6 months after surgery), they may not return to baseline levels.3 Further, chronic opioid use can lead to opioid dependence and opioid use disorder, which has been associated with $6,000-$21,000 in excess health care costs per patient per year, stemming from such causes as opioid overdoses, longer hospital stays, and adverse events.5-9

Following surgery, health care providers often prescribe opioids to treat acute pain. Estimates suggest that between 49% and 95% of patients who undergo surgery are discharged with an opioid prescription.10-12 Postoperative opioid prescribing has specifically been implicated in subsequent persistent opioid use (usually defined as multiple opioid prescription fills after surgery)13-17 and increased health care burden. Patients who undergo surgical procedures such as mastectomies, appendectomies, cholecystectomies, and total hip or knee arthroplasties are at higher risk for persistent opioid use than those who do not have surgery,13 and several analyses have found that receipt of an opioid shortly after surgery is associated with persistent opioid use 1 year later.13-15 Other risk factors for persistent opioid use include male gender, age ≥ 50 years, preoperative benzodiazepine or antidepressant use, and substance abuse history.13 Patients who receive a long-acting opioid within 30 days of a hip, knee, or shoulder replacement surgery are more likely to have subsequent hospitalizations and ED visits and greater health care costs in the 12 months after surgery than patients who do not receive an opioid in a similar time frame.18

Further, multiple studies show that persistent opioid use after surgery is not limited to those patients with previous opioid use. Opioid-naive patients who receive an opioid prescription after surgery may become new persistent opioid users,14-16,19 which may lead to opioid misuse and increased health care utilization and costs.18 An earlier study by our group showed that opioid-naive patients who fill at least 1 opioid prescription in the year after a major inpatient or outpatient surgery had 19%-61% higher costs compared with patients who did not receive an opioid prescription in the same time frame, but did not focus specifically on new persistent opioid use.20 Given that persistent opioid use is now widely recognized in the surgery community as a common morbidity outcome, we sharpen the focus on the impact of new persistent opioid use on postoperative costs.

Given the associations between subsequent persistent use following specific surgery types and increased health care utilization and costs, this analysis aimed to illustrate the impact of new persistent opioid use after a broad range of major surgical procedures among opioid-naive patients by comparing the health care utilization and costs between those with new persistent opioid use and those without new persistent use.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND DATA SOURCE

This retrospective observational cohort study used health care claims data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (commercial), Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits (Medicare), and Medicaid Multistate (Medicaid) databases. The MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database contains the inpatient, outpatient, and outpatient prescription drug experience of employees and their dependents covered under a variety of fee-for-service and managed care health plans. The MarketScan Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits database contains the health care experience (medical and pharmacy) of retirees with Medicare supplemental insurance paid for by employers. The Medicare-covered portion of payment (represented as coordination of benefits amount) and the employer-paid portion are included in this database. The MarketScan Medicaid Multistate database contains the pooled health care experience of Medicaid enrollees. Data come from multiple states that are geographically dispersed. For all databases used, medical claims are linked to outpatient prescription drug claims and person-level enrollment data through the use of unique enrollee identifiers.

All study data were obtained using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification and procedure coding system codes, Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition codes, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes, and National Drug Code (NDC) numbers.

Database records are statistically deidentified and certified to be fully compliant with U.S. patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Because this study used only deidentified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, it was exempt from institutional review board approval.

PATIENT SELECTION AND STUDY COHORTS

Patients (aged 18 years or older) with a major therapeutic or diagnostic surgery (excluding coronary artery bypass grafts, which are contraindicated for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and could introduce an opioid-use bias) as defined by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2017, were identified.21 Patients with commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid coverage were analyzed separately within each surgical setting (inpatient or outpatient). Patients with evidence of multiple surgeries had their earliest surgery analyzed. The index date was the discharge date for inpatient surgeries or the surgery date for outpatient surgeries. Patients were required to have continuous medical and pharmacy coverage for at least 1 year before (baseline period) and after the index date (follow-up period).

Patients were excluded if their claims records indicated the following: (a) an outpatient pharmacy or medical claim for opioids from 1 year before index date through 15 days before the index date; (b) opioid dependence, abuse, or overdose or treatment for dependence, abuse, or overdose in the baseline period; (c) evidence of inpatient or outpatient surgery in the baseline period; (d) evidence of multiple surgeries during the same inpatient admission or on the outpatient surgery date; (e) evidence of inpatient or outpatient surgery between 31 days and 12 months after the index date. Surgeries within 30 days after the index date were allowed to account for potential follow-up surgeries due to complications from the index surgery; and/or (f) dual coverage by Medicare and Medicaid.

Patients were stratified into cohorts of those with or without evidence of new persistent opioid use based on previously published definitions.10,16,22,23 Patients qualified for the new persistent opioid use cohort if they met the following criteria: (a) at least 1 prescription or outpatient medical claim for an opioid between 4 and 90 days after the index date or at least 2 outpatient pharmacy claims for an opioid in the perioperative period, defined as 14 days before the index admission (inpatient) or surgery (outpatient) date through 3 days after the index date and (b) at least 1 additional outpatient pharmacy claim for an opioid between 91 and 180 days after the index date.

We assumed that patients may preemptively fill an opioid prescription in the perioperative period but not actually take the medication. By requiring at least 1 fill at least 4 days after surgery or at least 2 fills during the perioperative period, we sought to avoid misclassifying patients who did not take their perioperative fill as patients with new persistent use. Patients who did not meet the criteria above were classified as not having new persistent use after surgery. Within this cohort, patients may have had no opioid use or may have had some opioid use that did not meet the criteria for new persistent use.

OUTCOME MEASURES

Outcomes were measured in the 1-year period after the index date, excluding the index surgery admission (inpatient) or date (outpatient), and included health care utilization and costs. Outcomes were defined a priori. All-cause health care utilization and costs by type of service (inpatient, outpatient, ED, and office visits; ambulance/paramedic; other outpatient care, including any laboratory and outpatient imaging visits; and pharmacy [opioid and nonopioid]) were determined. For opioid prescriptions, the total dose in morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) prescribed to each patient during the study period was calculated by multiplying the number of pills on each pharmacy claim by the strength of the opioid from the NDC number on the claim, then multiplying by a morphine equivalent conversion factor,24,25 and summing the dose on all claims. Opioid-related utilization and costs incurred in the perioperative period were included in post-index surgery analyses. Total medical (inpatient + outpatient) and total health care (total medical + pharmacy) costs were reported. Health care costs were based on paid amounts on adjudicated claims, including insurer payments and patient cost sharing, and were inflation adjusted to 2018 U.S. dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.26

STUDY COVARIATES

Demographic characteristics (age, sex, race [Medicaid only]; geographic region [commercial/Medicare only]; and plan type) and surgery type (general, orthopedic, plastic, obstetrical/gynecological, or other) were captured on the index date. Clinical characteristics, including Deyo Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCCI); comorbid conditions (chronic pain [chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, low back pain, migraine, musculoskeletal pain, neuropathy, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, other arthropathies, sickle cell anemia, chronic pain syndrome, and “other” chronic pain]; substance use disorders [alcohol, tobacco, and other substance abuse]; psychological comorbidities [anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia, and other mood disorders]; cardiovascular disease; morbid obesity; pulmonary disease; and sleep apnea/other sleep disorders); baseline medications (antidepressants, anxiolytics, gabapentinoids); and baseline all-cause total health care costs were measured during the 12-month baseline period.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

For bivariate descriptive analyses, continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations and categorical variables as counts and percentages. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables, and t-tests were used for continuous measures for statistical comparisons. A critical value of 0.05 was considered a priori as the threshold for statistical significance.

Multivariable analyses were conducted using generalized linear models with gamma-distributed error and log link to assess whether new persistent opioid use was associated with higher postoperative total health care costs. Opioid costs were assumed to be higher among those patients with new persistent use; therefore, opioid costs were not included in the models. Variance inflation factors were calculated for all predictors and suggested no evidence of collinearity. Large percentages of postoperative total health care costs were $0 for the Medicaid population. In these cases, a 2-part hurdle modeling approach was used to estimate the predicted probability of incurring these costs among all patients and the estimated costs among patients who incurred any costs.

Models were adjusted for age; sex; plan type; index year; geographic region (commercial/Medicare only); DCCI; type of surgery; presence of baseline comorbidities (chronic pain, substance abuse, psychological comorbidities, cardiovascular disease, morbid obesity, pulmonary disease, and sleep apnea/other sleep disorders); use of baseline medications (antidepressants, anxiolytics, and gabapentinoids); and allcause health care costs over the 12-month baseline period ($0-$999; $1,000-$1,999; $2,000-$2,999; $3,000-$3,999; $4,000-$4,999; $5,000-$6,999; $7,000-$8,999; $9,000-$12,999; $13,000-$20,999; and ≥ $21,000). The recycled prediction method was used to predict covariate-adjusted costs on the dollar scale. When a 2-part model was used, average costs were estimated as the probability of incurring any costs multiplied by the predicted costs. Confidence intervals of covariate-adjusted costs were estimated using bootstrap resampling.

Results

PATIENT SELECTION

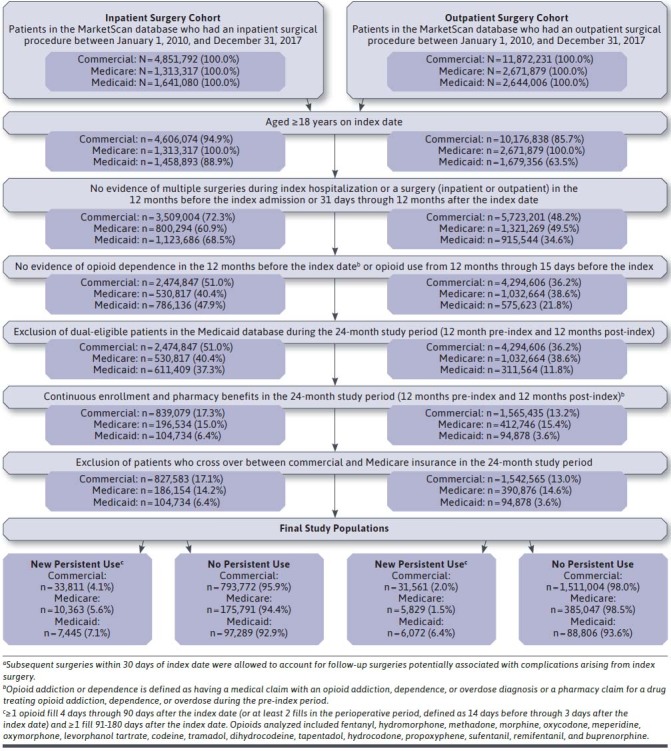

The inpatient surgery cohorts consisted of 827,583 commercially insured, 186,154 Medicare, and 104,734 Medicaid patients. Of these, 4.1%, 5.6%, and 7.1% of patients had new persistent opioid use after their index surgery, respectively (Figure 1). The outpatient surgery cohorts included 1,542,565 patients with commercial insurance, 390,876 patients with Medicare, and 94,878 patients with Medicaid coverage. Of these, 2.0%, 1.5%, and 6.4% of patients had new persistent opioid use after their index surgery, respectively. All patients were opioid naive before the index surgery’s perioperative period, per the patient selection criteria.

Figure 1.

Attrition

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

For patients with commercial or Medicaid inpatient index surgeries, those with new persistent opioid use were older, and higher proportions were male than those without persistent use (Supplementary Table 1 (147.7KB, pdf) , available in online article). The opposite was true for Medicare: patients with new persistent opioid use were slightly younger and more likely to be female than those without persistent use. Baseline chronic pain was more prevalent for those with new persistent opioid use after index than it was for those without (commercial 49.4% vs. 31.3%; Medicare: 66.2% vs. 52.8%; Medicaid: 45.0% vs. 29.4%; all P < 0.001). Rates of other identified baseline comorbidities and concomitant medication use were higher for patients with new persistent opioid use than for those without across all payers.

The composition of surgery types was different between the new persistent opioid use and no persistent use cohorts. Specifically, a larger percentage of patients with new persistent opioid use had an orthopedic index surgery compared with patients without persistent use (commercial: 35.1% vs. 13.4%; Medicare: 49.9% vs. 32.3%; Medicaid: 20.0% vs. 5.4%; all P < 0.001). A larger percentage of patients with new persistent opioid use had an opioid prescription fill in the perioperative period compared with patients without persistent use in each payer cohort (commercial: 82.4% vs. 72.8%; Medicare: 52.4% vs. 41.3%; Medicaid: 76.0% vs. 73.6%; all P < 0.001).

Unadjusted mean (SD) all-cause total health care costs in the year before index surgery were approximately 30% higher for the new persistent opioid use cohort versus the no persistent use cohort for the commercial ($11,766 [$29,167] vs. $8,884 [$20,599]; P < 0.001) and Medicaid ($7,457 [$20,994] vs. $5,662 [$20,292]; P < 0.001) populations. For Medicare, these costs were not significantly different ($13,590 [$37,880] vs. $13,194 [$29,470]; P = 0.192).

For patients with an outpatient index surgery, those with new persistent opioid use after surgery were slightly younger than those without persistent use in the commercial and Medicare cohorts and slightly older in the Medicaid cohort (Supplementary Table 2 (147.7KB, pdf) , available in online article). For all payers, the proportions of female patients was higher in the new persistent opioid use cohort than in the no persistent use cohort. The prevalence of baseline chronic pain and other captured comorbidities followed the same patterns as those observed in the inpatient cohorts.

Unadjusted mean (SD) all-cause total health care costs in the year before surgery were 37% and 54% higher for the new persistent use cohorts for commercial ($8,902 [$18,064] vs. $6,503 [$13,398]; P < 0.001), and Medicare ($16,126 [$29,615] vs. $10,476 [$22,622]; P < 0.001), respectively, and were not significantly different in the Medicaid cohort ($6,227 [$16,080] vs. $6,252 [$20,124]; P = 0.924).

HEALTH CARE UTILIZATION AND COSTS

In the inpatient study cohorts, the mean (SD) number of opioid prescription fills during follow-up was 5 times higher among those with new persistent opioid use than those without persistent use across all payers (commercial: 6.4 [3.9] vs. 1.3 [1.3]; Medicare: 6.1 [4.5] vs. 1.1 [1.5]; Medicaid 7.9 [6.8] vs. 1.5 [1.5]; Table 1). The total (SD) opioid dose (in MME) was 7-9 times higher for patients with new persistent use after surgery (commercial: 3,851 mg [4,961 mg] vs. 543 mg [896 mg]; Medicare 2,577 mg [3,999 mg] vs. 507 mg [943 mg]; Medicaid 3,852 mg [5,944 mg] vs. 422 mg [824 mg]). Inpatient admissions, ED visits, ambulance/paramedic service use, and nonopioid prescription fills were all more frequent in the year following surgery among patients with new persistent use than for those without, regardless of payer. Analogous utilization trends were observed for patients with outpatient surgeries (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Health Care Utilization and Costs Among Opioid-Naive Patients with New Persistent Opioid Use Versus Patients Without Persistent Use in the Year Following a Major Inpatient Surgerya

| Commercial | Medicare | Medicaid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Persistent Opioid Use (n = 33,811) | No Persistent Opioid Use (n = 793,722) | New Persistent Opioid Use (n = 10,363) | No Persistent Opioid Use (n = 175,791) | New Persistent Opioid Use (n = 7,445) | No Persistent Opioid Use (n = 97,289) | |

| Health care utilization | ||||||

| Inpatient admissions, n (%) | 5,846 (17.3) | 46,056 (5.8)c | 2,063 (19.9) | 24,247 (13.8)c | 1,811 (24.3) | 9,042 (9.3)c |

| Emergency department visits, n (%) | 12,838 (38.0) | 160,241 (20.2)c | 4,504 (43.5) | 56,225 (32.0)c | 5,307 (71.3) | 46,029 (47.3)c |

| Ambulance/paramedic services, n (%) | 2,958 (8.8) | 23,990 (3.0)c | 2,405 (23.2) | 29,095 (16.6)c | 2,023 (27.2) | 11,239 (11.6)c |

| Pharmacy prescriptions | ||||||

| Opioid prescriptions, n (%)b | 33,620 (99.4) | 617,096 (77.7)c | 10,295 (99.3) | 101,676 (57.8)c | 7,421 (99.7) | 80,072 (82.3)c |

| Opioid prescriptions per patient, mean (SD)b | 6.4 (4.9) | 1.3 (1.3)c | 6.1 (4.5) | 1.1 (1.5)c | 7.9 (6.8) | 1.5 (1.5)c |

| Total opioid dose per patient, in MMEs, mean (SD) | 3,851 (4,961) | 543 (896)c | 3,577 (3,999) | 507 (943)c | 3,852 (5,944) | 422 (824)c |

| Nonopioid prescriptions, n (%) | 33,369 (98.7) | 704,586 (88.8)c | 10,321 (99.6) | 165,852 (94.4)c | 7,380 (99.1) | 85,343 (87.7)c |

| Nonopioid prescriptions per patient, mean (SD) | 28.2 (24.5) | 14.9 (17.9)c | 39.1 (28.0) | 29.6 (24.5)c | 45.1 (50.1) | 19.3 (32.9)c |

| Health care costs, $, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Total medical costs | 30,827 (70,438) | 9,044 (34,410)c | 26,851 (74,277) | 17,703 (47,085)c | 13,247 (39,105) | 4,875 (23,363)c |

| Inpatient admissions | 7,391 (37,052) | 1,824 (19,327)c | 4,748 (26,378) | 3,466 (21,900)c | 5,770 (29,851) | 1,754 (17,889)c |

| Outpatient services | 23,436 (51,705) | 7,220 (25,345)c | 22,103 (66,505) | 14,237 (38,738)c | 7,477 (20,316) | 3,121 (12,707)c |

| Emergency department visits | 889 (3,286) | 350 (1,824)c | 828 (3,054) | 601 (3,002)c | 623 (1,913) | 202 (742)c |

| Office visits | 1,336 (2,021) | 693 (1,224)c | 1,366 (2,008) | 1,088 (1,412)c | 476 (738) | 206 (385)c |

| Ambulance/paramedic services | 178 (1,485) | 54 (818)c | 307 (1,145) | 219 (1,300)c | 125 (652) | 34 (260)c |

| Other | 21,033 (50,321) | 6,122 (24,631)c | 19,603 (65,563) | 12,328 (37,815)c | 6,254 (19,643) | 2,680 (12,430)c |

| Pharmacy costsb | 4,188 (12,196) | 1,945 (8,841)c | 4,657 (10,638) | 3,456 (7,926)c | 2,801 (8,949) | 1,143 (7,567)c |

| Opioid prescriptionsb | 179 (1,357) | 18 (58)c | 130 (335) | 16 (161)c | 162 (803) | 11 (160)c |

| Nonopioid prescriptions | 4,009 (12,063) | 1,928 (8,840)c | 4,528 (10,613) | 3,439 (7,923)c | 2,639 (8,854) | 1,133 (7,562)c |

| Total health care costsb | 35,015 (74,312) | 10,989 (36,833)c | 31,508 (76,299) | 21,159 (48,461)c | 16,048 (42,192) | 6,018 (25,902)c |

aExcludes the index admission.

bIncludes any opioid prescriptions received in the perioperative period. A small number of patients qualified for the new persistent use cohort by HCPCS codes only, which are captured under outpatient medical services and thus did not have an opioid prescription.

c P < 0.001, new persistent opioid use versus no persistent opioid use.

HCPCS = Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; MMEs = morphine milligram equivalents.

TABLE 2.

Health Care Utilization and Costs Among Opioid-Naive Patients with New Persistent Opioid Use Versus Patients Without Persistent Use in the Year Following a Major Outpatient Surgerya

| Commercial | Medicare | Medicaid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Persistent Opioid Use (n = 31,561) | No Persistent Opioid Use (n = 1,511,004) | New Persistent Opioid Use (n = 5,829) | No Persistent Opioid Use (n = 385,047) | New Persistent Opioid Use (n = 6,072) | No Persistent Opioid Use (n = 88,806) | ||

| Health care utilization | |||||||

| Inpatient admissions, n (%) | 2,990 (9.5) | 49,399 (3.3)c | 1,424 (24.4) | 37,528 (9.8)c | 947 (15.6) | 7,851 (8.8)c | |

| Emergency department visits, n (%) | 10,991 (34.8) | 242,919 (16.1)c | 2,514 (43.1) | 83,223 (21.6)c | 4,349 (71.6) | 39,859 (44.9)c | |

| Ambulance/paramedic services, n (%) | 1,576 (5.0) | 26,146 (1.7)c | 1,145 (19.6) | 31,290 (8.1)c | 1,078 (17.8) | 8,639 (9.7)c | |

| Pharmacy prescriptions | |||||||

| Opioid prescriptions, n (%)b | 31,561 (100.0) | 1,051,611 (69.6)c | 5,829 (100.0) | 133,906 (34.8)c | 6,072 (100.0) | 67,829 (76.4)c | |

| Opioid prescriptions per patient, mean (SD)b | 5.2 (3.8) | 1.0 (1.1)c | 5.3 (3.8) | 0.5 (1.0)c | 6.6 (5.0) | 1.4 (1.5)c | |

| Total opioid dose per patient, in MMEs, mean (SD) | 2,595 (3,556) | 403 (724)c | 2,853 (3,532) | 194 (565) | 2,807 (4,262) | 417 (781)c | |

| Nonopioid prescriptions, n (%) | 30,978 (98.2) | 1,292,940 (85.6)c | 5,814 (99.7) | 361,503 (93.9)c | 6,041 (99.5) | 78,229 (88.1)c | |

| Nonopioid prescriptions per patient, mean (SD) | 23.6 (22.1) | 13.3 (16.0)c | 38.6 (28.5) | 24.9 (21.7)c | 40.6 (43.7) | 27.6 (39.0)c | |

| Health care costs, $, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Total medical costs | 16,836 (44,698) | 5,589 (19,533)c | 26,093 (65,080) | 10,457 (30,933)c | 7,648 (20,418) | 4,927 (18,137)c | |

| Inpatient admissions | 2,978 (18,699) | 677 (8,757)c | 5,969 (21,863) | 2,051 (12,705)c | 2,201 (13,512) | 1,058 (10,319)c | |

| Outpatient services | 13,857 (36,333) | 4,912 (16,457)c | 20,124 (56,379) | 8,406 (26,126)c | 5,448 (13,087) | 3,869 (13,868)c | |

| Emergency department visits | 711 (2,396) | 238 (1,336)c | 826 (3,308) | 357 (2,094)c | 492 (1,247) | 184 (663)c | |

| Office visits | 1,036 (1,638) | 577 (754)c | 1,393 (1,902) | 847 (1,069)c | 469 (676) | 249 (453)c | |

| Ambulance/paramedic services | 72 (696) | 25 (532)c | 311 (3,168) | 99 (1,035)c | 56 (400) | 29 (347)c | |

| Other | 12,039 (35,342) | 4,072 (16,048)c | 17,594 (55,004) | 7,103 (25,388)c | 4,430 (12,517) | 3,407 (13,617)c | |

| Pharmacy costsb | 2,861 (9,012) | 1,683 (6,418)c | 4,807 (9,143) | 3,030 (7,005)c | 2,309 (7,164) | 1,654 (12,880)c | |

| Opioid prescriptionsb | 106 (385) | 13 (42)c | 112 (321) | 6 (45)c | 95 (480) | 9 (72)c | |

| Nonopioid prescriptions | 2,755 (8,986) | 1,670 (6,417)c | 4,695 (9,120) | 3,024 (7,003)c | 2,214 (7,109) | 1,644 (12,879)c | |

| Total health care costsb | 19,696 (46,817) | 7,272 (21,203)c | 30,900 (66,916) | 13,487 (32,412)c | 9,958 (23,230) | 6,581 (23,504)c | |

aExcludes the index date.

bIncludes any opioid prescriptions received in the perioperative period. A small number of patients qualified for the new persistent use cohort by HCPCS codes only, which are captured under outpatient medical services and thus did not have an opioid prescription.

cP < 0.001, new persistent opioid use versus no persistent opioid use.

HCPCS = Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; MMEs = morphine milligram equivalents.

Unadjusted all-cause total health care costs in the year after an inpatient index surgery were higher among patients with new persistent opioid use than for those without persistent use, regardless of payer (Table 1). Medical costs accounted for the majority of total costs (81.0%-88.0%) among all cohorts. Other outpatient services (i.e., those not specifically identified as ED visits, office visits, or ambulance/paramedic services) made up approximately two thirds of the total medical costs for the commercial and Medicare cohorts (67.7%-73.0%) and about half for the Medicaid cohorts (47.2%-55.0%). Average postoperative total, nonopioid, and opioid pharmacy costs (excluding costs accrued during the index surgery admission) were all significantly higher for those with new persistent use versus those without. Opioid prescription costs were 1% or less of the total health care costs for all payers and cohorts. Similar trends were observed for postoperative costs in the year after surgery in the outpatient cohort (Table 2).

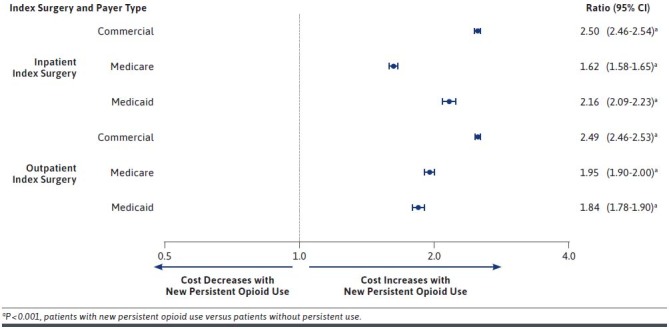

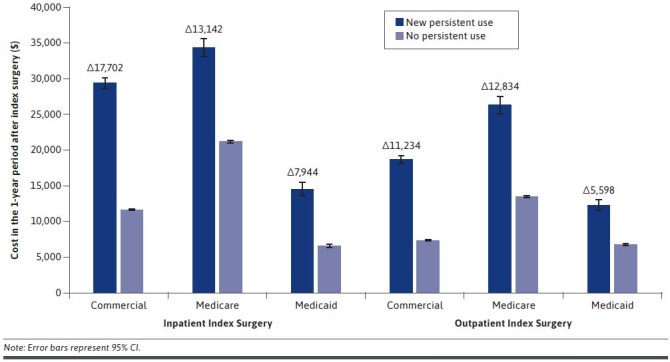

Total health care costs (excluding opioid pharmacy costs) for patients with versus patients without new persistent opioid use after surgery were further examined in multivariable models. After adjusting for baseline characteristics, total health care costs in the year after an inpatient index surgery for commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid patients with new persistent opioid use were 2.50-fold (95% CI: 2.46-2.54), 1.62-fold (95% CI: 1.58-1.65), and 2.16-fold (95% CI: 2.09-2.23) higher total than those for similar patients who did not have persistent use, respectively (Figure 2). Findings for patients with an outpatient index surgery were consistent: 1-year post-index surgery total health care costs for commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid patients with new persistent opioid use were 2.49 (95% CI: 2.46-2.53), 1.95 (95% CI: 1.90-2.00), and 1.84 (95% CI: 1.78-1.90) times higher than those for patients without persistent use, respectively. Incremental total health care cost differences were $7,994-$17,702 for patients with an inpatient index surgery and $5,598-$12,834 for those with an outpatient index surgery, depending on payer (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Multivariable-Adjusted Cost Ratios for Total Health Care Costs for Opioid-Naive Patients with New Persistent Opioid Use Versus Patients Without Persistent Use After a Major Inpatient or Outpatient Surgery, Excluding Opioid Pharmacy

Figure 3.

Multivariable-Adjusted Predicted Total Health Care Costs for Opioid-Naive Patients with New Persistent Opioid Use Versus Patients Without Persistent Use After a Major Inpatient or Outpatient Surgery

Discussion

This claims-based analysis compared health care utilization and costs among previously opioid-naive patients who had new persistent opioid use after a major inpatient or outpatient surgery versus those who did not. Across all cohorts, patients with new persistent opioid use had significantly higher adjusted total health care costs in the year after their index surgery than those without persistent use. In unadjusted analyses, health care utilization was also greater among patients with new persistent opioid use compared with patients without persistent use.

Of patients in this study, 4.1%-7.1% of those with inpatient index surgeries and 1.5%-6.4% of those with outpatient index surgeries were identified as having new persistent opioid use after their index event. These values are consistent with previously published analyses examining new persistent opioid use in previously opioid-naive patients.16 Patients with new persistent opioid use were more likely to have chronic pain conditions and other common comorbidities (including previous substance abuse), more nonopioid medications before surgery, and more apt to have a perioperative opioid prescription fill, in line with previously published work.20 The composition of surgery subtypes also differed between the new persistent use and no persistent use cohorts. These factors may affect the likelihood of a patient becoming a persistent opioid user13; thus, they were included as covariates in multivariable analyses. New persistent opioid users had 4.9-5.3 times more opioid prescriptions after an inpatient surgery and 7.1-9.1 times more total MMEs associated with these prescriptions. Similar trends were observed after outpatient index surgeries.

New persistent opioid use is associated with higher health care utilization rates and costs, and postoperative opioid use contributes substantially to the burden on the U.S. health care system. Earlier work by our group demonstrated that previously opioid-naive surgery patients who received any opioid prescription in the year after their index procedure had higher inpatient and ED utilization rates and 1.19-1.61 times higher mean adjusted total health care costs in that year (depending on surgical setting and payer) versus those who did not receive an opioid prescription during the same time period.20 New persistent use of opioids is now recognized as a common morbidity outcome in the surgery community27; however, there are limited data on cost-related outcomes,28 and none that have examined differences across payer type. Therefore, in this study, we specifically focused on previously opioid-naive patients who become new persistent users after a major surgery. Here, mean adjusted total health care costs were 1.62-2.50 times higher for previously opioid-naive patients with new persistent opioid use after a major surgery than those for such patients without persistent use. Correspondingly, adjusted predicted 1-year mean all-cause health care costs were significantly higher for patients with new persistent use than for those without across all cohorts in the year after index surgery: incremental cost differences were between $7,944 and $17,702 for those with an inpatient index surgery and $5,598 and $12,834 for those with an outpatient index surgery, depending on the payer. This range exceeds the range of our previously published study for those patients with any opioid use versus those without opioid use (incremental total health care costs of $4,309-$7,770 for patients with an inpatient index surgery; $3,763-$9,304 for those with an outpatient index procedure),20 indicating that persistent opioid use plays a large role in driving increased costs after major surgical events.

The results of this study are consistent with the study published by Gold et al. (2016), who conducted a retrospective analysis comparing health care utilization and costs among joint replacement surgery patients who received long-acting opioids versus those who did not.18 There, patients who received a long-acting opioid prescription within 30 days of surgery had greater health care costs over 12 months versus those who did not. Patients in this study with new persistent opioid use also had higher utilization of inpatient, ED, and ambulance/paramedic services in the 12 months following their surgery than those without persistent use, consistent with previous studies examining receipt of any opioid prescription after surgery.18,20

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing the cost impact of new persistent opioid use in previously opioidnaive patients across a large range of major surgery types. Given the observations that the majority of surgery patients receive an opioid after their procedure10-12 and surgery patients are more likely to use opioids persistently,14-16,19 opioid-naive patients who become new persistent opioid users after surgery may contribute substantially to the increased health care utilization and costs associated with opioid use and misuse. These results highlight both the need for careful consideration of perioperative opioid prescribing, and the continued need for nonaddictive, nonopioid alternatives for postoperative pain management after a major surgical event.

LIMITATIONS

Several limitations inherent to retrospective studies are present in this study. The MarketScan Research databases rely on administrative claims data for clinical detail. There is a potential for misclassification of surgeries, covariates, and outcomes in data from administrative claims, which are subject to data coding limitations and data entry error. Illicit use of opioids and use of over-the-counter nonopioid medications cannot be tracked using administrative claims data. Similarly, dental surgeries are not captured in the MarketScan databases; thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that opioid prescriptions filled after a dental surgery during follow-up could be included when defining new persistent use.

The presence of an opioid prescription claim does not indicate that medications were taken as prescribed. Opioid use data during the index hospital admission (inpatient surgeries) or on the surgery date (outpatient surgeries) were not available for this study. There may be systematic differences between the study cohorts that account for differences found in health care utilization and costs. Although differences between cohorts were adjusted for by multivariable regressions, adjustment was limited to characteristics measured in administrative claims.

This analysis used a 1-year baseline period and a 1-year follow-up period. Patients who died before the end of follow-up were excluded from the analysis. Patients with opioid use more than 1 year before index surgery may have been included in the study sample.

Finally, this study was limited to only those individuals with commercial, Medicare, or Medicaid health coverage. Consequently, results of this analysis may not be generalizable to all surgery patients, especially those with other types of coverage and the uninsured.

Conclusions

New persistent opioid use in the year after major surgery was associated with increased adjusted health care utilization and costs across all payers and in both inpatient and outpatient surgical settings. Reducing exposure of opioid-naive patients to opioids and by limiting opioid prescribing and/or providing nonopioid options for pain relief in the perioperative period could reduce opioid use in the year postsurgery and, in turn, result in lower long-term costs and improved outcomes for these patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Jessamine Winer-Jones, PhD, of IBM Watson Health, provided critical revision of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes—United States surveillance special report. November 1, 2019. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2019-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf

- 2.Leider HL, Dhaliwal J, Davis EJ, Kulakodlu M, Buikema AR. Healthcare costs and nonadherence among chronic opioid users. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):32-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kern DM, Zhou S, Chavoshi S, et al. Treatment patterns, healthcare utilization, and costs of chronic opioid treatment for non-cancer pain in the United States. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(3):e222-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghate SR, Haroutiunian S, Winslow R, McAdam-Marx C. Cost and comorbidities associated with opioid abuse in managed care and Medicaid patients in the United States: a comparison of two recently published studies. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2010;24(3):251-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice JB, Kirson NY, Shei A, et al. The economic burden of diagnosed opioid abuse among commercially insured individuals. Postgrad Med. 2014;126(4):53-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice JB, Kirson NY, Shei A, et al. Estimating the costs of opioid abuse and dependence from an employer perspective: a retrospective analysis using administrative claims data. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014;12(4):435-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oderda GM, Lake J, Rudell K, Roland CL, Masters ET. Economic burden of prescription opioid misuse and abuse: a systematic review. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2015;29(4):388-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer R, Patel AM, Rattana SK, Quock TP, Mody SH. Prescription opioid abuse: a literature review of the clinical and economic burden in the United States. Popul Health Manag. 2014;17(6):372-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirson NY, Scarpati LM, Enloe CJ, Dincer AP, Birnbaum HG, Mayne TJ. The economic burden of opioid abuse: updated findings. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(4):427-45. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.16265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Yun L, Wijeysundera DN. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii MH, Hodges AC, Russell RL, et al. Post-discharge opioid prescribing and use after common surgical procedure. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(6):1004-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nooromid MJ, Blay E, Jr, Holl JL, et al. Discharge prescription patterns of opioid and nonopioid analgesics after common surgical procedures. Pain Rep. 2018;3(1):e637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):425-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in U.S. adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jivraj NK, Raghavji F, Bethell J, et al. Persistent postoperative opioid use: a systematic literature search of definitions and population-based cohort study. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(6):1528-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold LS, Strassels SA, Hansen RN. Health care costs and utilization in patients receiving prescriptions for long-acting opioids for acute postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(9):747-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JS, Hu HM, Edelman AL, et al. New persistent opioid use among patients with cancer after curative-intent surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(36):4042-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brummett CM, England C, Evans-Shields J, et al. Health care burden associated with outpatient opioid use following inpatient or outpatient surgery. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(9):973-83. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2019.19055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare cost and utilization project: procedure classes 2015. 2015. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/procedure/procedure.jsp

- 22.Harbaugh CM, Nalliah RP, Hu HM, Englesbe MJ, Waljee JF, Brummett CM. Persistent opioid use after wisdom tooth extraction. JAMA. 2018;320(5):504-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard R, Gunaseelan V, Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Englesbe MJ, Telem D. Risk factors for new persistent opioid use associated with inguinal hernia repair. Ann Surg. October 15, 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004560 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Analyzing prescription data and morphine milligram equivalents (MME). 2019. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/resources/data.html

- 25.ClinicalTrials.gov. To evaluate patient preference of movantik and polyethylene glycol 3350 for opioid induced constipation. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03060512

- 26.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index (CPI) databases. 2018. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

- 27.Barth RJ, Jr., Waljee JF. Classification of opioid dependence, abuse, or overdose in opioid-naive patients as a "never event". JAMA Surg. 2020;155(7):543-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JS, Vu JV, Edelman AL, et al. Health care spending and new persistent opioid use after surgery. Ann Surg. 2020;272(1):99-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]